Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was comparison of association of three main first trimester screening factors with pregnancy outcomes among Iranian pregnant women.

Materials and methods: This prospective study was done during 2017-2019 years in Qazvin, Iran. To do so, a total of 1500pregnant women in first trimester were enrolled. At the first step, Nuchal translucency (NT) was measured in 11-13 ± 5 week, then the serum pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) and free-β-human chorionic gonadotropin (free-β-HCG) were measured in 12-14 weeks of gestation. Pregnant women were followed up until the end of pregnancy for the complications of pregnancy such as intra-uterine growth retardation (IUGR), intrauterine death (IUFD), different types of fetal loss and preterm labor.

Results: The results showed that low levels of serum biomarkers had more association with pregnancy complications in comparison to high levels of them. Significant association of IUGR (P = 0.001), IUFD (P = 0.032) and pre-term labor (P = 0.002) was shown in women with low serum levels of PAPP-A in comparison to low serum levels of free-β-hCG. Significant high frequency of different types of fetal loss (IUFD, Abortion, Elective termination) was shown in fetuses with N ≥ 3 in comparison to low levels of serum biomarkers (P = 0.001).

Conclusion: This study highlighted the importance of accurately interpreting the results of the first trimester of pregnancy screening which should be considered by primatologists for subsequent pregnancy care.

Key Words: Free-Beta Human Gonadotropin, Pregnancy Associated Protein-A, Nuchal Translucency, Pregnancy

Introduction

Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A), Free Human chorionic gonadotropin (Free-β-HCG), and Nuchal translucency (NT) measurements in the first trimester of pregnancy are combined screening for evaluation of fetus chromosomal abnormality. Measurement of these parameters is based on the recommendations of the Fetal Medicine Foundation (FMF) (1, 2). PAPP-A is a protein associated with pregnancy which is produced by both the embryo and the placenta during pregnancy (1). Its main function is proteolysis of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 4 and 5 (IGFBP 4 and 5) (3). It has major role in the local proliferation. Protease activity of PAPP-A increases the availability of IGF and causes the transfusion of glucose and amino acids in the placenta (4). The amount of PAPP-A increases from the first detection in the first trimester until the term. Low level of PAPP-A (≤ 0.4 MoM) in first trimester is associated with pregnancy complications such as: intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) of fetus, IUFD (Intra uterine fetal death), preeclampsia and preterm birth (4-6).

HCG is a member of the glycoprotein hormone (GPH) family; HCG is heterodimer protein consisting of α- and β- subunits; α-subunit is common to all GPHs, but biological activity of HCG hormone is in β subunit and distinguishes hCG from other glycoprotein hormones. HCG functions during the pregnancy are mitotic growth, differentiation of the endometrium, localized suppression of the maternal immune system, modulation of uterine morphology, gene expression and coordination of intricate signal transduction between the endometrium. B-hCG lacks hCG activity, but several lines of study indicate that it exerts growth promoting activity. It has been speculated that b-hCG interferes with the growth-inhibiting effect of transforming growth factor-b, platelet-derived growth factor-B and nerve growth factor (7, 8). The peak of maternal serum hCG is at 8–10 weeks and then reduces to reach a plateau at 18–20 weeks. The same as PAPP-A, decreasing of free β-HCG (≤ 0.5 MoM) is associated with some pregnancy complication such as preeclampsia and preterm birth and etc. (9).

Around 11th to 14th weeks of pregnancy Nuchal translucency (NT) is measured by sonography in fetus (10). The size of NT shows the amount of fluid behind the neck of the fetus. There is a significant correlation between the increased NT and the chromosomal abnormalities, specialty trisomy 21. Therefore, with other factors such as mother age, presence of nasal bone, and blood flow across the tricuspid valve or in the ductus venous detection, the rate of Down syndrome improves to 85 % in first trimester of pregnancy. The amount of fluid behind neck can be increased in fetus with normal karyotype. In this condition fetus is at a significant risk of still birth, heart defect, and delay in neurodevelopment (10-12).

According to the above contents, the aim of this study was to analyze the association of different rates of NT, serum PAPP-A, Free-β-HCG with pregnancy outcome among the Iranian pregnant women with normal karyotype fetus.

Materials and methods

This study was performed between 2017- 2019 years and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences (IR.QUMS.REC.1399.113). Each of the recruited patients gave their informed written consent. In this timespan, 1500 pregnant women were referred to our laboratory by perinatologist. The first trimester screening took place at 11-13 ± 5 weeks of pregnancy and estimation of pregnancy week was according to the results of the first trimester ultrasound. The candidate women were also informed about the limitations of the screening method.

Before measuring the level of PAPP-A and Free-β-HCG in the serum of pregnant women, measurement of NT was done in a sonography center; then based on the recommended criteria by the FMF, risks were calculated according to the FMF program (13, 14). For evaluation of serum parameters, a clotted blood sample was obtained and serum PAPP-A and free β-hCG were measured using Cobas E 411 analyzer (made by Roche company, Germany, 2011). Serum parameters were converted into multiples of the median (MoM), then adjusted for some parameters such as the size of NT, maternal age, weight, history of Down syndrome, etc. Risk assessment of first-trimester was done according to the Feto-maternal module of the Astraia software (version 1.18.088). A calculated risk of equal to or higher than 1: 250 was defined as ‘high-risk’, between 250 and 1500 as intermediate risk and lower than 250 as low risk. A perinatologist recommended amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling for evaluation of chromosomal abnormality in high risk situations. A receipt of the information was obtained from all participants. Pregnant mothers with different ranges of NT, PAPP-A, free β-hCG and normal karyotype were followed up for the outcome of pregnancy by contacting their obstetricians and study of the documents.

In fetuses with high NT (NT≥3) and normal karyotype, the size of NTs were classified into 4 levels (namely 3-4, 4-5, 5-6 and ≥6) and the frequency of some pregnancy complication parameters such as different types of fetal loss (Abortion, IUFD, and elective termination) and heart abnormality was evaluated in these groups. Also, the pregnancy complication factors compared in two groups of pregnant women with 0.4≤PAPP-A and 0.5≤β-hCG and those with PAPP-A ≤ 0.4 and β-hCG ≤ 0.5.

Statistical analysis: The results were analyzed by the GraphPad analytical software (GraphPad PRISM V 5.04). The association between different ranges of the first trimester screening markers and pregnancy complications was assessed by computing the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) from logistic regression analyses. We also used the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test for evaluation of different pregnancy outcomes frequency. All P-values were two-tailed and with P<0.05 considered statistically significant

Results

In this research, 1500 pregnant women were evaluated in the first trimester (1470 singleton and 30 twin pregnancies). The mean of maternal age was 31 ± 2.82 years and 21.4% of them were 35 years of age or older. Demographic characteristics of the studied pregnant women are summarized in tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of studied population

| Characters (n = 1500) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Mother age | |

| 17 ≤ age ≤ 20 | 30 (2) |

| 20 ≤ age ≤ 30 | 720 (48) |

| 30 ≤ age ≤ 40 | 600 (40) |

| ≥ 40 | 150 (10) |

| Mode of conception | |

| Spontaneous | 1350 (90) |

| Assisted | 75(5) |

| Not reported | 75 (5) |

| Previous affected pregnancy | |

| Yes | 120 (8) |

| No | 1380 (92) |

| Gestational age at screening time | |

| 11 | 300 (20) |

| 12 | 870 (58) |

| 13 | 33 (22) |

Table 2.

Frequency of different chromosomal abnormalities in aneuploid fetuses

| Types of chromosomal abnormality | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Numerical | |

| Trisomy 21 | 30 (2) |

| Trisomy 18 | 5 (0.3) |

| Trisomy 13 | 2 (0.13) |

| Monosomy X | 0 (0) |

| Triploeidy | 2 (0.13) |

| Structural | |

| Tr (2;6) (p13;p23) | 1 (0.06) |

| In 8 (p12;q21) | 1 (0.06) |

| Del X (p1.1) | 1 (0.06) |

Tr: Translocation, In: Inversion, Del: Deletion

Totally, 24% of the studied fetuses had an estimated risk equal to or more than 1:250.

Among the age, ultrasound, NT, and biochemical factors, NT ≥ 3 had the highest detection rate of Down syndrome (66.6%) as can be seen in Table 3. In our study 42 (2.8%) of fetuses had chromosomal aberrations: trisomy 21 (n = 30), trisomy 18 (n = 5), trisomy 13 (n = 2), triploidy (n = 2), and structural chromosomal abnormality (n = 3) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Detection rate of age, ultrasound, and serum biochemical factors among the Iranian pregnant women

| Characters (n = 1500) | n(%) | Risk ≥ 1:250 [n(%)] |

Detection rate [n(%)]

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trisomy 21 | Trisomy 18 | Trisomy 13 | |||

| Maternal age | |||||

| 17 ≤ age ≤ 20 | 30 (2) | 5 | 2/30: %6.6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 20 ≤ age ≤ 30 | 720 (48) | 158 | 8/30: %26.6 | 2/5: %40 | 1/2: %50 |

| 30 ≤ age ≤ 40 | 600 (40) | 167 | 18/30: %60 | 3/5: %60 | 1/2:%50 |

| ≥ 40 | 150 (10) | 42 | 2/30: %6.6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| NT ≥ 3 | 105 (7) | 40 | 2/30: %6.6 | 3/5: %60 | 1/2: %50 |

| Absent of nasal bone | 15 (1) | 9 | 13/30: %42.4 | 2/5: %40 | 0 (0) |

| fβ-hCG ≥ 2 MoM | 100 (6) | 21 | 10/30: %33.33 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| PAPP-A ≤ 0.5 MoM | 102 (6.8) | 28 | 6/30: %17.8 | 3/5: %60 | 2/2:%100 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | 9 (0.6) | 5 | 12/30: % 36.3 | 4/5:80 | 0 (0) |

MOM: Multiple of median, fβ-hCG: Free beta human chronic gonadotropin, PAPP-A: Pregnancy associated protein

In another part of this research, we classified PAPP-A and free β-hCG cutoff points to low, and high ranges; then, different pregnancy complications such as IUGR, different types of fetal loss (Abortion, IUFD, elective termination), and preterm labor were compared among these groups. Our evaluation results showed that PAPP-A ≤ 0.4 and free β-hCG ≤ 0.5 had adverse effect on pregnancy outcomes in comparison to PAPP-A ≥ 2 and free β-hCG ≥ 2. About PAPP-A ≤ 0.4, frequency of IUGR was 18.5% but this frequency in high range was 1.8% (P = 0.001). Moreover, preterm labor frequency in samples with low level PAPP-A was significantly higher than (14.8%) samples with high level PAPP-A (6.5%) (P = 0.001).

Regarding the different types of fetal loss (Abortion, IUFD and elective termination) frequency we did not observe significant difference between samples with low and high ranges of PAP-A (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of frequency of various pregnancy complications between samples with the cutoff points of PAPP-A and Β-HCG

|

Papp-A

≤ 0.4 |

Papp-A

> 2 |

OR (95% CI) |

P-

value |

Fβ-hCG ≤

0.5 |

Fβ-hCG >

2 |

OR (95% CI) |

P-

value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUGR | 277 (18.5) | 27 (1.8) | 2.13 (0.32-7.13) | < 0.001 | 73 (4.9) | 47 (3.1) | 1.02 (0.2-1.2) | 0.07 |

| Normal growth |

1222 (81.5) | 1473 (98.2) | 1427 (95.1) | 1453 (96.9) | ||||

| Pre-term Labor |

222 (14.8) | 98 (6.5) | 1.76 (0.11-6.1) | < 0.001 | 61 (4.06) | 39 (2.65) | 0.78 (0.22-0.65) | 0.23 |

| Term-labor | 1278 (85.2) | 1402 (93.5) | 1483 (98.86) | 1461 (97.4) | ||||

| Different types of fetal loss | ||||||||

| IUFD | 132 (8.8) | 22. (1.5) | 1.9 (0.44-2.1) | 0.03 | 79 (5.3) | 13 (2.2) | 0.92 (0.2-0.87) | 0.12 |

| Normal pregnancy |

1368(91.2) | 1477 (98.5) | 14205 (94.7) | 1467 (97.8) | ||||

| Abortion | 18(1.2) | 5205(3.5) | 0.84 (0.11-0.87) | 0.089 | 127 (8.47) | 28 (1.9) | 2.92 (0.85-6.1) | 0.003 |

| Not abortion | 1482(98.8) | 1477 (96.5) | 1372 (91.53) | 1483 (98.9) | ||||

| Elective termination |

34 (2.3) | 7 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.1-0.75) | 0.12 | 46 (3.1) | 16 (1.12) | 0.12 (0.01-1.1) | 0.34 |

| Not elective termination |

1465 (97.7) | 1492 (99.5) | 1453 (96.9) | 1483 (98.9) | ||||

P-value shows comparison results of between high and low levels of serum markers. (Logistic regression analyses test). Fβ-hCG: Free beta human chronic gonadotropin, PAPP-A: Pregnancy associated protein A, IUFD: Intra uterine fetal death, IUGR: Intra uterine growth retardation.

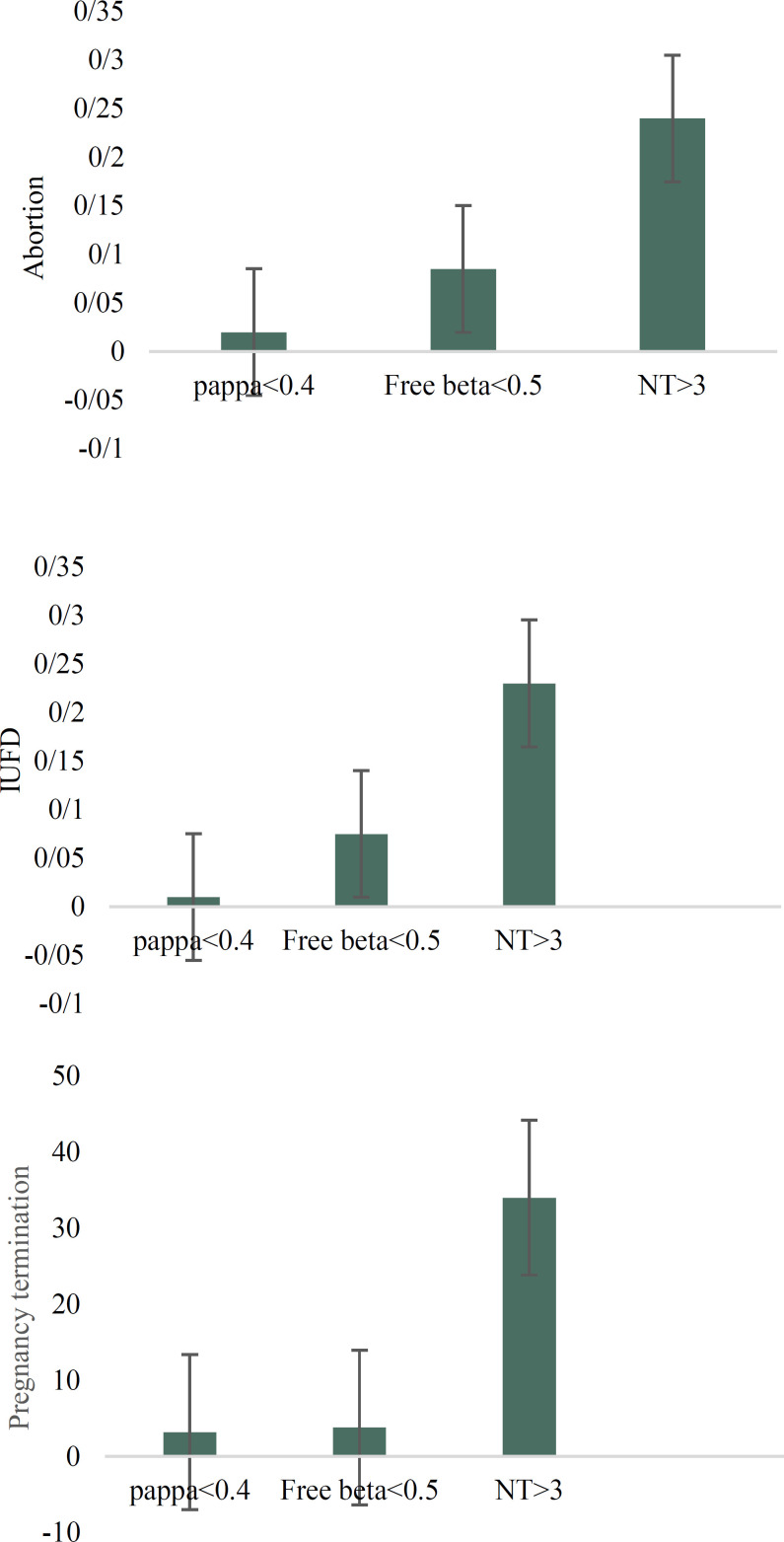

Comparison of association of low and high ranges of free β-hCG with different pregnancy outcomes showed no significant difference between low and high levels of free β-hCG; we only observed high frequency of abortion in women with free β-hCG ≤ 0.5 in comparison to high range of this factor (P = 0.003). The comparison of pregnancy outcomes of patients with PAPP-A ≤ 0.4 and free β-hCG ≤ 0.5 showed a high frequency of IUGR (P < 0.001), IUFD (P = 0.032), and Pre-term labor (P = 0.002) in samples with PAPP-A ≤ 0.4 when compared to pregnancies with free β-hCG ≤ 0.5; nevertheless, we observed high frequency of abortion in samples with free β-hCG ≤ 0.5 in comparison to PAPP-A ≤ 0.4 (P = 0.001) (Table 4). In the studied samples, 105 of the fetuses had NT ≥ 3 and 38% of them had Down syndrome risk ≥ 250. We observed high frequency of abortion (P < 0.001), IUFD (P < 0.001) and elective termination of pregnancy (P < 0.001) in the samples with high NT in comparison to normal NT (Table 5). Among different types of fetal loss (abortion, IUFD and elective termination), elective termination of pregnancy had the highest frequency in samples with NT ≥ 3 (33.3%). The Comparison of association of chemical parameters (PAPP-A and Free-beta HCG) and high NT with different types of fetal loss showed high frequency of abortion, IUFD and elective termination of pregnancy in high NT fetuses in comparison to low PAPP-A and Free β-HCG fetuses (Figure 1). Because the heart defect had the highest frequency in fetus with NT ≥ 3, we checked distinct subtypes of heart defects in the mentioned samples. Our results showed that frequency of ventricular septal defect (VSD) was higher than other defects (Table 6).

Table 5.

Frequency of pregnancy outcome in different NT thickness

| NT (mm) |

≤ 3

|

3-4

|

4-5

|

5-6

|

≥ 6

|

Total with high NT | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Successful delivery | 1305 (94) | 28 (53.8) | 5 (15.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 33 (31.4) | 4.12 (0.35-5.1) | < 0001 |

| Abortion | 45 (3.2) | 10 (19.2) | 10 (30.3) | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0) | 22 (20.9) | 3.34 (0.15-3.8) | < 0001 |

| IUFD | 19 (1.36) | 5 (9.6) | 7 (21.2) | 3 (20) | 0 (0) | 15 (14.2) | 1.7 (1.35-4.1) | < 0001 |

| Termination | 26 (1.86) | 9 (17.3) | 11(33.3) | 10 (66.6) | 5 (100) | 35 (33.3) | 5.12 (0.22-3.56) | < 0001 |

| Total | 1395 | 52 | 33 | 15 | 5 | 105 | - | - |

P-value shows significant difference in some pregnancy complication between fetus with nt≤3 and nt>3 (Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test), IUFD: Intra uterine fetal death.

Figure 1.

(a): Shows comparison of frequency of abortion in papp-a≤0.4, free beta hcg. ≤0.5 and NT>3. (b): shows comparison of frequency of IUFD in papp-a≤0.4, free beta hcg. ≤0.5 and NT>3. (c): shows comparison of frequency of elective termination of pregnancy in papp-a≤0.4, free beta hcg. ≤0.5 and NT>3.

Table 6.

Frequency of different heart defects in different NT thickness

| NT (mm) |

≤ 3

|

3-4

|

4-5

|

5-6

|

≥ 6

|

Total

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Frequency of patients with heart defect | 3(0.2) | 5(0.3) | 3(0.2) | 1(0.06) | 0 (0) | 12(0.8) |

| VSD | 2(0.13) | 3(0.2) | 1(0.06) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (0.4) |

| VSD, ASD and aortic coarctation | 1(0.06) | 1(0.06) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.13) |

| VSD, ASD and tricuspid valve anomaly | 1(0.06) | 1(0.06) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1(0.06) | 3 (0.2) |

| Hypo plastic left ventricle | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 | 1 (8.3) |

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test. Nt: Nuchal translucency, VSD: Ventricular septal defect, ASD: Atrial septal defect.

Discussion

In this prospective study, the results of comparison of maternal serum biochemical markers and ultrasound markers of first-trimester screening for pregnancy outcomes were evaluated for 1500 Iranian pregnant women. 2.8% of fetuses had chromosomal abnormality, specially trisomy 21 or Down syndrome. Among the mentioned screening parameters for trisomy 21, high NT had the highest detection rate (66.6%).

Based on our results, low level of Papp-A and free β-hCG had the most adverse effect on pregnancy outcomes in comparison to high levels of them. In this regard another multicenter study has shown that in women with high PAPP-A and free β-hCG pregnancy outcomes do not differ with those with normal levels (15). But when we analyzed the effect of low PAPP-A and free β-hCG levels on pregnancy complications, we observed impressive association of low PAPP-A on the IUGR and pre-term labor in comparison to low levels of free β-hCG. Generally speaking, PAPP-A is one of the chorionic products and is secreted in maternal blood during pregnancy. The rate of this protein grows in maternal serum during pregnancy (16, 17). During the first trimester, the decrease of this protein in mothers’ serum is one of the evidences of chromosomal aberration (18). But the predicting value of PAPP-A for pregnancy outcomes has not been reported (19).

Based on our results, the highest association of low level PAPP-A was seen with IUGR. In this context, other reports have shown IUGR to be more associated with low maternal serum PAPP-A (20, 21). Only in one research no association between low level PAPP-A and IUGR is reported (22). Concerning IUFD it can be said that this phenomenon occurs one in 160 pregnancies in developed countries. The correlation of other factors such as obesity, age, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, etc. with the IUFD was already reported, but in some studies it is showed that PAPP-A≤0.4 is associated with stillbirth and IUFD. In 2002, among the 8839 pregnant women, Smith et al. reported that women with first and early second trimester PAPP-A levels in the lowest 5th centile were more likely to experience intrauterine death (23).

In another study, Dugoff et al. in 2004, concluded that first trimester low PAPP-A levels are associated with intrauterine fetal death at ≤ 24 weeks of gestation (24). Kaijomaa et al. in 2017, reported the same results (25). However, the notable finding of this study was high frequency of fetal loss in fetuses with NT≥3 in comparison to low levels of PAPP-A and free-beta HCG. In this regard, we saw significant high frequency of abortion, IUFD and elective termination in fetuses with NT≥3 in comparison to low PAPP-A and free β-hCG. In this context, Dugoff et al., 2004 showed significant association of high NT with abortion in comparison to low free β-hCG among the USA pregnant women (24). In the same year among the USA pregnant women, Goetz et al. reported the association of low PAPP-A, free β-hCG and high NT with abortion but they did not compare the association of these markers individually (1). Besides, Lithner et al., 2016 reported association of high NT with miscarriage in Sweden population (26).

In our study, evaluating the association of NT ≥ 3 with pregnancy outcomes showed that there was high frequency of elective termination of pregnancy, some of them was because of structural abnormalities such as diaphragmatic hernia, exomphalos, skeletal defects, and some genetic syndromes. Among the structural abnormalities, heart defects especially VSD had the most frequency.

Frequency of structural abnormality in our studied fetuses was 9.8% which was higher than expected in general population (2-3%) (27). Heart defects were confirmed in 12 out of 20 infants with structural abnormalities. In this regard different studies reported association of NT thickness with major heart defects when compared to those with normal hearts (28-30). For example, in a retrospective study it was shown that the 55% of heart and vessel defects were associated with increased NT (31). For these reasons, fetuses with increased NT and normal karyotype are candidate of fetal echocardiography.

Conclusion

In conclusion, based on the results of this research, among the three first trimester screening markers, high NT had the most association with different types of fetal loss and fetus structural abnormality. Regarding the fact that the first trimester screening markers have association with pregnancy complications, it is suggested that perinatologists consider this problem and when interpreting the screening results pay attention to the values of biomarkers MOM in addition to analyzing the risk of chromosomal syndromes.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere thanks to all patients and normal individuals for their contribution.

Conflict of Interests

Authors have no conflict of interests.

Notes:

Citation: Abotorabi S, Moeini N, Moghbelinejad S. High Frequency of Fetal Loss in Fetuses With Normal Karyotype and Nuchal Translucency ≥ 3 Among the Iranian Pregnant Women. J Fam Reprod Health 2020; 14(2): 81-7.

References

- 1.Goetzl L, Krantz D, Simpson JL, Silver RK, Zachary JM, Pergament E, et al. Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A, free β-hCG, nuchal translucency, and risk of pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:30–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000129969.78308.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuchter K, Hafner E, Stangl G, Metzenbauer M, Ho finger D, Philipp K. The first trimester ‘combined test’ for the detection of Down syndrome pregnancies in 4939 unselected pregnancies. Prenat Diagn. 2002;22:211–15. doi: 10.1002/pd.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrence JB, Oxvig C, Overgaard MT, Sottrup –jensen L, GleicGJ , Hays LG, et al. The insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-dependent IGF binding protein-4 protease secreted by human fibroblasts is pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3149–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalousova M, Muravska A, Zima T. Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) and preeclampsia. Adv Clin Chem. 2014;63:169–209. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-800094-6.00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith GC, Shah I, Crossley JA, Aitken DA, Pell JP, Nelson SM, et al. Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A and alpha-fetoprotein and prediction of adverse perinatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:161–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000191302.79560.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tonskaker T, Bartlett G, Trpkow C. Health information on the Internet. Gold mine or minefield? Can FAM Physician. 2014;60:407–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler SA, Iles RK. The free monomeric beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG beta) and the recently identified homodimeric beta–beta subunit (hCG beta beta) both have autocrine growth effects. Tumour Biol. 2004;25:18–23. doi: 10.1159/000077719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ulf-Hakan S, Aila T, Henrik A, Leena V. The classification, functions and clinical use of different isoforms of hCG. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12:769–84. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruz J, Cruz G, Minerkawa R, Mazi N, Nicolaides KH. Effect of temperature on free b-human chorionic gonadotropin and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A concentration. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36:141–6. doi: 10.1002/uog.7688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogers H, Rifouna MS, Cohen-Overbeek TE, Koning AHJ, Willemsen SP, van der Spek PJ, et al. First trimester physiological development of the fetal foot position using three-dimensional ultrasound in virtual reality. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:280–8. doi: 10.1111/jog.13862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu SS, Lee FK, Lee JL, Tsai MS, Cheng ML, She BQ, Chen SC. Pregnancy outcomes in unselected singleton pregnant women with an increased risk of first-trimester Down's syndrome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:1130–4. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rozenberg P, Bussières L, Chevret S, Bernard JP, Malagrida L, Cuckle H, et al. Screening for Down syndrome using firsttrimester combined screening followed by second-trimester ultrasound examination in an unselected population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1379–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snijders RJ, Noble P, Sebire N, Souka A, Nicolades KH. UK multicentre project on assessment of risk for trisomy 21 by maternal age and fetal nuchal translucency thickness at 10 – 14 weeks of gestation. Lancet. 1998;352:343–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocha ADS, Bernardi JR, Matos S, Kretzer DC, Schöffel AC, Goldani MZ, et al. Maternal visceral adipose tissue during the first half of pregnancy predicts gestational diabetes at the time of delivery - a cohort study. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0232155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuckle H, Arbuzova S, Spencer K, Crossley J, Barkai G, Krantz D, et al. Frequency and clinical consequences of extremely high maternal serum PAPP-A levels. Prenat Diagn. 2003;23:385–8. doi: 10.1002/pd.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conover CA, Bale LK, Overgaard MT, Johnstone EW, Laursen UH, Fuchtbauer EM, et al. Metalloproteinase pregnancy-associated plasma protein A is a critical growth regulatory factor during fetal development. Development. 2004;131:1187–94. doi: 10.1242/dev.00997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence JB, Oxvig C, Overgaard MT, Sottrup-Jensen L, Gleich GJ, Hays LG, et al. The insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-dependent IGF binding protein-4 protease secreted by human fibroblasts is pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3149–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huynh L, Kingdom J, Akhtar S. Low pregnancy-associated plasma protein A level in the first trimester. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:899–903. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saruhan Z, Ozakinci M, Simsek M, Mendilcioglu I. Association of first trimester low PAPP-A with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:225–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah KH, Anjum A, Nair P, Bhat P, Bhat RG, Bhat S. Pregnancy associated plasma protein A: An indicator of adverse obstetric outcomes in a South India population. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;17:40–5. doi: 10.4274/tjod.galenos.2020.05695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tul N, Pusenjak S, Osredkar J, Spencer K, Novak-Antolic Z. Predicting complications of pregnancy with first-trimester maternal serum free-betahCG, PAPP-A and inhibin-A. Prenat Diagn. 2003;23:990–6. doi: 10.1002/pd.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendoza M, Garcia-Manau P, Arévalo S, Avilés M, Serrano B, Sánchez-Durán MÁ. Diagnostic accuracy of first-trimester combined screening for early-onset and preterm preeclampsia at 8-10 weeks compared to 11-13 weeks gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020:10.1002/uog.22071. doi: 10.1002/uog.22071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith GCS, Stenhouse EJ, Crossley JA, Aitken DA, Cameron AD, Connor JM. Early pregnancy levels of pregnancy-associated plasma protein a and the risk of intrauterine growth restriction, premature birth, preeclampsia, and stillbirth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1762–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dugoff L, Hobbins JC, Malone FD, Porter TF, Luthy D, Comstock CH, et al. First-trimester maternal serum PAPP-A and free-beta subunit human chorionic gonadotropin concentrations and nuchal translucency are associated with obstetric complications: a population-based screening study (the FASTER Trial) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1446–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaijomaa M, Rahkonen L, Ulander VM, Hämäläinen E, Alfthan H, Markkanen H, et al. Low maternal pregnancy-associated plasma protein A during the first trimester of pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;136:76–82. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lithner CU, Kublickas M, Ek S. Pregnancy outcome for fetuses with increased nuchal translucency but normal karyotype. J Med Screen. 2016;23:1–6. doi: 10.1177/0969141315595826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Westin M, Saltvedt S, Bergman G, Almstrom H, Grunewlad C, Valentin L. Is measurement of nuchal translucency thickness a useful screening tool for heart defects? A study of 16,383 fetuses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27:632–9. doi: 10.1002/uog.2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müller MA, Bleker OP, Bonsel GJ, Bilardo CM. Nuchal translucency screening and anxiety levels in pregnancy and puerperium. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27:357–61. doi: 10.1002/uog.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogel M, Sharland GK, McElhinney DB, Zidere V, Simpson JM, Miller OI, et al. Prevalence of increased nuchal translucency in fetuses with congenital cardiac disease and a normal karyotype. Cardiol Young. 2009;19:441–5. doi: 10.1017/S1047951109990655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clur SA, Ottenkamp J, Bilardo CM. The nuchal translucency and the fetal heart: a literature review. Prenat Diagn. 2009;29:739–48. doi: 10.1002/pd.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Domenico R, Faraci M, Hyseni E, Di Prima FA, Valenti O, Monte S, et al. Increased nuchal traslucency in normal karyotype fetuses. J Prenat Med. 2011;5:23–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]