Abstract

Background

Noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) of recessive monogenic diseases depends heavily on knowing the correct parental haplotypes. However, the currently used family-based haplotyping method requires pedigrees, and molecular haplotyping is highly challenging due to its high cost, long turnaround time, and complexity. Here, we proposed a new two-step approach, population-based haplotyping-NIPT (PBH-NIPT), using α-thalassemia and β-thalassemia as prototypes.

Methods

First, we deduced parental haplotypes with Beagle 4.0 with training on a large retrospective carrier screening dataset (4356 thalassemia carrier screening-positive cases). Second, we inferred fetal haplotypes using a parental haplotype-assisted hidden Markov model (HMM) and the Viterbi algorithm.

Results

With this approach, we enrolled 59 couples at risk of having a fetus with thalassemia and successfully inferred 94.1% (111/118) of fetal alleles. We confirmed these alleles by invasive prenatal diagnosis, with 99.1% (110/111) accuracy (95% CI, 95.1–100%).

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that PBH-NIPT is a sensitive, fast, and inexpensive strategy for NIPT of thalassemia.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13073-021-00836-8.

Keywords: NIPT, Recessive monogenic diseases, Haplotypes, Population-based haplotyping, α-Thalassemia, β-Thalassemia

Background

The discovery of cell-free fetal DNA enables noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) for common aneuploidies [1, 2], microdeletion/microduplication syndromes [3–5], and monogenic disorders. Initially, NIPT of monogenic disorders focused on detecting de novo or paternally inherited variants responsible for dominant monogenic disorders [6, 7]. Reports indicate that the average genomic carrier burden for severe pediatric recessive variants is 2.8 per person [8] and that the cumulative prevalence among live births is approximately 0.8% [9]. NIPT for most recessive monogenic disorders involves several technical challenges and has only been made clinically available for a limited number of recessive conditions [10] despite the relatively high prevalence of such disorders, because analysis of maternally inherited fetal alleles has been hampered by the high background of maternal DNA in cell-free DNA (cfDNA) [11]. The current approaches for NIPT of recessive diseases are typically classified into two categories [12, 13]: relative mutation dosage (RMD) analysis [14] and relative haplotype dosage (RHDO) analysis [15]. The RMD approach focuses on quantitative comparisons between variant and wild-type alleles present in cfDNA and has relatively high sensitivity and specificity [14, 16]. This approach is powerful for detecting single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (InDels) but usually cannot detect large InDels and copy number variants (CNVs) [17–19]. Its performance is also affected by sequencing errors and amplification bias of low-abundance fetal variants in cfDNA [20]. Unlike the RMD approach, the RHDO approach determines the relative proportions of variant and normal haplotypes in maternal plasma [21] and can theoretically detect most types of variants, including large InDels and CNVs, in one test [16, 22]. However, RHDO analysis requires parental haplotype information [23]. Although molecular phasing approaches to determine parental haplotypes, including linked-read sequencing [24, 25] and targeted locus amplification (TLA) [26], have not been widely used in clinical settings due to their high cost and complex procedures [27–32], population-based parental haplotyping provides an alternative approach due to its rapid turnaround and inexpensive and relatively simple procedures. However, the use of this method has been limited to a founder variant (GBA gene, c.1226A>G) [33].

Thalassemia causes hemoglobin deficiency and affects approximately 4.4 per 10,000 live births worldwide [34]. Its genetic complexity involves three types of variants: SNVs, InDels, and CNVs. In southern China, the most prevalent variants of α-thalassemia are -α3.7 deletion, --SEA deletion, -α4.2 deletion, HBA2 c.369C>G, and HBA2 c.427T>C, while those of β-thalassemia are HBB c.126_129delCTTT, HBB c.52A>T, HBB c.316-197C>T, HBB c.-78A>G, and HBB c.79G>A [35, 36]. Our population screening data for thalassemia [35] shows that these 10 variants account for 87.9% of β-thalassemia carriers and 96.5% of α-thalassemia carriers (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

In the present study, we proposed a novel population-based haplotyping-NIPT method (PBH-NIPT) for α-thalassemia and β-thalassemia in which nonfounder variants were detected when the sample size of the reference panel (population data used to infer parental haplotypes) was sufficiently large for accurate deduction of parental haplotypes. The PBH-NIPT model was trained on a large retrospective carrier screening dataset, and its accuracy was verified via invasive prenatal diagnosis. In addition, we assessed the effect of the reference panel sample size on the outcomes of PBH-NIPT.

Methods

Patients and samples

The ethics committees of Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center and BGI approved this study (approval numbers: 2017102408 and BGI-IRB 18043). Fifty-nine couples at risk of having a fetus with thalassemia provided written informed consent. The clinical features of the participants are provided in the supplement (Additional file 2: Table S1). We collected 5 ml of blood from each parent. We promptly isolated maternal plasma using a two-step centrifugation method [37]. We used 10 ml of amniotic fluid (AF) or 5 mg of chorionic villus sample (CVS) for invasive prenatal diagnosis.

Sequencing library preparation

We extracted cfDNA from maternal plasma using a QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen, Dusseldorf, Germany) and extracted parental gDNA from peripheral blood and fetal DNA from CVS or AF using a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen).

We used gDNA (500 ng) for library construction and fragmented it ultrasonically with a Bioruptor Pico (Diagenode, Liege, Belgium), yielding 300–700-bp fragments. We then performed end repair, phosphorylation, and A-tailing reactions on the sheared DNA and ligated BGISEQ adaptors with specific barcodes to the A-tailed products. We performed 4–6 cycles of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification to enrich the target regions and performed hybridization capture according to the NimbleGen protocols after pooling twenty barcoded gDNA libraries in equal amounts. Finally, we performed circularization of the post-capture library to generate circular single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). We prepared the maternal plasma DNA library using the same method except without fragmentation and pooled eight cfDNA libraries in equal amounts. After quantitation using Qubit 3.0 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA), we used rolling circle replication to form DNA nanoballs (DNBs) from the ssDNA and loaded each DNB into 1 lane to be processed for 100-bp paired-end sequencing on the BGISEQ-500 and MGISEQ-2000 platforms (BGI, Shenzhen, China).

Reference panel construction

We generated the reference panel from 4356 thalassemia carrier screening-positive cases. Of the total 4356 cases, 3867 were obtained from our previously published paper [35], and 489 were obtained from unpublished in-house data.

We first used our previously published algorithm [35] to call SNPs from 4356 positive carriers and then filtered SNPs with a sequencing depth of less than 20-fold in more than 2% of the population or with an allele ratio between 5 and 40% in more than 70% of heterozygous individuals in the population. We used the publicly available software Beagle (version 4.0) to construct haplotypes for 4356 individuals and used these data as the reference panel for the next step. Since SNPs and InDels are the acceptable input for Beagle, we treated CNVs as SNPs in the phasing procedure. CNVs are represented as the VCF format of SNPs in the Beagle input file (VCF format), where the genomic position is the start position of the CNV, and the genotypes “0/1” and “1/1” represent heterozygous and homozygous CNVs, respectively.

Construction of parental haplotypes by PBH

We aligned the sequence reads from parental gDNA and maternal plasma DNA to the reference human genome (hg19) using BWA version 0.7.12. We marked duplicate reads with Picard version 1.87 and performed variant calling as previously described [35]. We also treated CNVs as SNPs in the phasing procedure. We used the haplotypes of the reference panel and the genotypes of the parents as inputs to deduce parental haplotypes with Beagle 4.0. Finally, we used only heterozygous SNPs to represent parental haplotypes.

NIPT of thalassemia

We calculated the fetal fraction (FF) as described in Additional file 3 and inferred fetal haplotypes inherited from the father and mother separately. First, we determined paternal inheritance using paternal informative SNPs, which were heterozygous in the father but homozygous in the mother. Second, we determined maternal inheritance using maternal informative SNPs, which included two types of SNPs: (1) SNPs heterozygous in the mother but homozygous in the father and (2) SNPs heterozygous in the parents in the blocks where the first step inferred the fetal inherited haplotype from the father. Because informative SNPs linked to the inherited haplotype are overrepresented in maternal plasma, we applied the hidden Markov model (HMM) and Viterbi algorithm [38] to determine the fetal genotypes of pathogenic sites (Additional file 3: Supplementary Methods). For samples with CNVs, all SNPs in the CNV region were not selected as informative SNPs to perform Viterbi decoding.

Invasive prenatal diagnosis of thalassemia

We performed invasive prenatal diagnosis via chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis in accordance with standard protocols. We determined fetal genotypes through gap-PCR and reverse dot blot PCR (RDB-PCR).

The effect of the reference panel sample size on the outcomes of PBH-NIPT

To assess the effect of the reference panel sample size on the outcomes of PBH-NIPT, we randomly selected one-half, one-quarter, one-sixth, one-eighth, one-twelfth, and 50 of the samples from the total reference panel and performed three independent tests.

Results

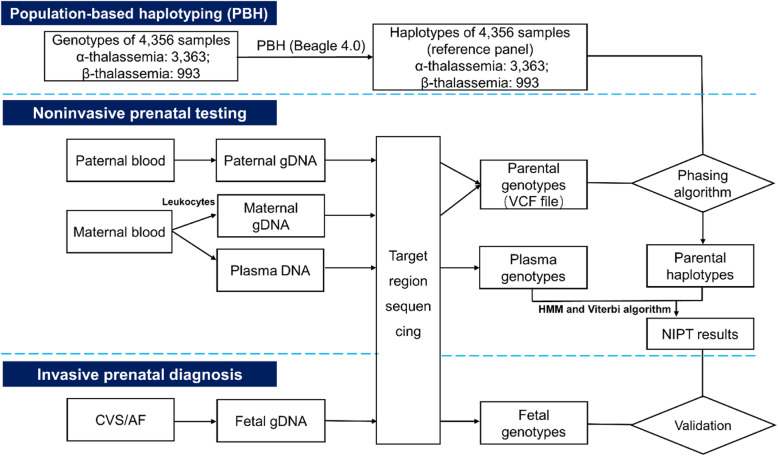

As shown in Fig. 1, the PBH-NIPT workflow involves the following steps. First, we generated the reference panel from 4356 thalassemia carrier screening-positive cases. Of the total 4356 cases, 3867 were obtained from our previously published paper [35], and 489 were obtained from unpublished in-house data. Second, we enrolled 59 couples in whom both partners carried at least one of the 10 aforementioned variants and were at risk of having a fetus with thalassemia major or intermedia [39] (Additional file 2: Table S1). The average gestational age at the time of collection was 12.6+3 weeks (range 10+1–22 weeks), and the average FF was 15.4% (range 6.0–26.1%) (Additional file 4: Table S2). We subjected genomic DNA (gDNA) of the couples and fetuses as well as maternal cfDNA to hybridization-based capture and sequencing using a strategy previously described for thalassemia carrier screening [35]. We obtained an average target region coverage of 177-fold (range 56–678) in maternal plasma and 203-fold (range 85–360) in parental gDNA. Third, we inferred parental haplotypes by PBH (see the “Methods” section and Fig. 1). To evaluate the reliability of PBH, we also constructed parental haplotypes by family-based haplotyping (FBH) and calculated the percentage of concordant single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) phased by these two methods (Additional file 3: Supplementary Methods). The average concordance rates of phased SNPs in the maternal and paternal haplotypes were 98.7% (range 87.5–100%) and 95.7% (range 59.2–100%), respectively (Additional file 5: Fig. S2; Additional file 6: Table S3).

Fig. 1.

Population-based haplotyping-noninvasive prenatal testing (PBH-NIPT) workflow. The workflow involves 3 parts. We first constructed haplotypes of 59 couples using the haplotypes of 4356 samples as the reference panel. Then, we inferred fetal haplotypes using a hidden Markov model (HMM) and the Viterbi algorithm. Finally, we used invasive prenatal diagnosis results to validate PBH-NIPT results

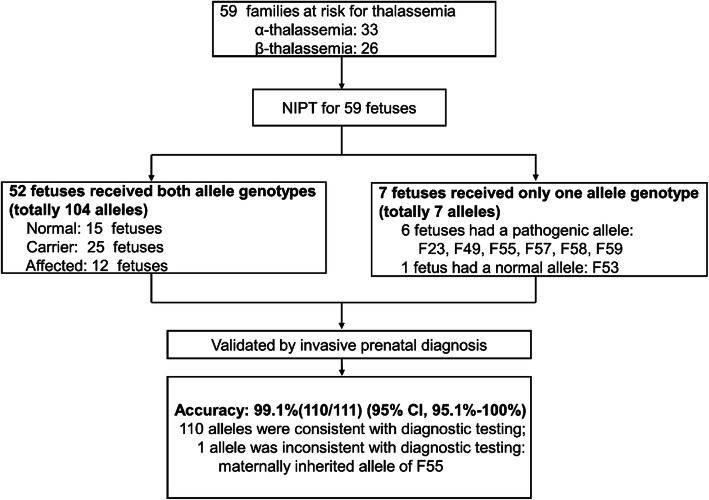

To correctly infer fetal genotypes of pathogenic sites (rather than all SNPs), we developed a hidden Markov model (HMM) and used the Viterbi algorithm. We calculated a confidence score (CS), defined as the probability of obtaining the correct NIPT result, to evaluate the reliability of each prediction. A “no-call” condition was defined when (1) the CS was less than 0.99 or (2) the inferred haplotype contained two haplotype blocks (pathogenic and normal), and neither block spanned the target gene (HBB or HBA) (Additional file 3: Supplementary Methods). Accordingly, NIPT successfully inferred 111/118 (94.1%) alleles, and invasive prenatal diagnosis confirmed these alleles, with 99.1% (110/111 alleles) accuracy (95% CI, 95.1–100%) (Table 1, Fig. 2, and Additional file 7: Fig. S3). Among these 59 fetuses, 52 had both alleles detected; of these 52 fetuses, 15 were normal, 25 were carriers, and 12 were affected. Seven fetuses had only one allele successfully detected, and the other allele failed, with a CS of less than 0.99 (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Among the 7 fetuses with only one allele inferred by NIPT, 6 inherited the pathogenic allele. Obviously, invasive prenatal diagnosis was needed, which we used to clarify that 4 fetuses were affected and 2 were carriers.

Table 1.

Noninvasive prenatal testing of thalassemia

| Family | Gene | FF (%) | No. of maternal informative SNPs | No. of paternal informative SNPs | Mat Hap |

Pat Hap |

(%) | (%) | NIPT (Mat/Pat) | Invasive prenatal diagnosis (Mat/Pat) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For Mp | For Mn | For Pp | For Pn | |||||||||

| 52 fetuses received both allele genotypes | ||||||||||||

| F01 | HBB | 11.5 | 70 | 0 | 54 | 0 | Mp | Pp | 100 | 100 | c.52A>T/c.126_129delCTTT | c.52A>T/c.126_129delCTTT |

| F02 | HBB | 9.4 | 0 | 99 | 0 | 35 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F03 | HBB | 16.0 | 0 | 45 | 28 | 13 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F04 | HBB | 12.4 | 40 | 0 | 57 | 0 | Mp | Pp | 100 | 100 | c.126_129delCTTT/c.126_129delCTTT | c.126_129delCTTT/c.126_129delCTTT |

| F05 | HBB | 10.2 | 0 | 66 | 53 | 0 | Mn | Pp | 100 | 100 | N/c.126_129delCTTT | N/c.126_129delCTTT |

| F06 | HBB | 15.9 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 92 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | c.126_129delCTTT/N | c.126_129delCTTT/N |

| F07 | HBB | 12.8 | 0 | 110 | 19 | 0 | Mn | Pp | 100 | 100 | N/c.126_129delCTTT | N/c.126_129delCTTT |

| F08 | HBB | 21.8 | 43 | 31 | 33 | 40 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | c.126_129delCTTT/N | c.126_129delCTTT/N |

| F09 | HBB | 15.4 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 64 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | c.126_129delCTTT/N | c.126_129delCTTT/N |

| F10 | HBB | 17.6 | 26 | 3 | 0 | 25 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | c.126_129delCTTT/N | c.126_129delCTTT/N |

| F11 | HBB | 15.5 | 0 | 28 | 23 | 47 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F12 | HBB | 7.0 | 0 | 105 | 0 | 21 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F13 | HBB | 10.2 | 0 | 161 | 16 | 0 | Mn | Pp | 100 | 100 | N/c.126_129delCTTT | N/c.126_129delCTTT |

| F14 | HBB | 15.1 | 60 | 0 | 70 | 0 | Mp | Pp | 100 | 100 | c.126_129delCTTT/c.-78A>G | c.126_129delCTTT/c.-78A>G |

| F15 | HBB | 16.0 | 167 | 8 | 0 | 25 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | c.316-197C>T/N | c.316-197C>T/N |

| F16 | HBB | 6.0 | 85 | 0 | 0 | 51 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | c.316-197C>T/N | c.316-197C>T/N |

| F17 | HBB | 22.0 | 96 | 0 | 11 | 31 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | c.316-197C>T/N | c.316-197C>T/N |

| F18 | HBB | 15.5 | 72 | 0 | 3 | 42 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | c.-78A>G/N | c.-78A>G/N |

| F19 | HBB | 16.0 | 8 | 102 | 0 | 37 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F20 | HBB | 13.5 | 0 | 59 | 0 | 4 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F21 | HBB | 14.7 | 0 | 67 | 0 | 66 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F22 | HBB | 14.5 | 38 | 0 | 39 | 0 | Mp | Pp | 100 | 100 | c.52A>T/c.126_129delCTTT | c.52A>T/c.126_129delCTTT |

| F24 | HBB | 11.7 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 32 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F25 | HBB | 13.1 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 61 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F26 | HBB | 16.3 | 85 | 0 | 28 | 0 | Mp | Pp | 100 | 100 | c.126_129delCTTT/c.-78A>G | c.126_129delCTTT/c.-78A>G |

| F27 | HBA | 16.0 | 21 | 0 | 25 | 0 | Mp | Pp | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/- -SEA | - -SEA/- -SEA |

| F28 | HBA | 7.0 | 51 | 0 | 21 | 0 | Mp | Pp | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/ααWS | - -SEA/ααWS |

| F29 | HBA | 16.6 | 50 | 0 | 13 | 0 | Mp | Pp | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/- -SEA | - -SEA/- -SEA |

| F30 | HBA | 14.5 | 0 | 64 | 0 | 34 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F31 | HBA | 10.5 | 52 | 0 | 9 | 0 | Mp | Pp | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/- -SEA | - -SEA/- -SEA |

| F32 | HBA | 16.1 | 0 | 38 | 39 | 0 | Mn | Pp | 100 | 100 | N/- -SEA | N/- -SEA |

| F33 | HBA | 18.4 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 62 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/N | - -SEA/N |

| F34 | HBA | 16.5 | 0 | 20 | 13 | 0 | Mn | Pp | 100 | 100 | N/- -SEA | N/- -SEA |

| F35 | HBA | 14.3 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 28 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/N | - -SEA/N |

| F36 | HBA | 20.6 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 17 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/N | - -SEA/N |

| F37 | HBA | 20.6 | 8 | 0 | 11 | 0 | Mp | Pp | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/- -SEA | - -SEA/- -SEA |

| F38 | HBA | 15.3 | 0 | 51 | 0 | 9 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F39 | HBA | 23.9 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 25 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F40 | HBA | 18.3 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 7 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/N | - -SEA/N |

| F41 | HBA | 12.3 | 0 | 43 | 0 | 34 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F42 | HBA | 17.3 | 0 | 33 | 31 | 0 | Mn | Pp | 100 | 100 | N/- -SEA | N/- -SEA |

| F43 | HBA | 8.8 | 59 | 0 | 0 | 13 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/N | - -SEA/N |

| F44 | HBA | 26.1 | 31 | 0 | 42 | 0 | Mp | Pp | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/- -SEA | - -SEA/- -SEA |

| F45 | HBA | 24.4 | 0 | 80 | 17 | 0 | Mn | Pp | 100 | 100 | N/- -SEA | N/- -SEA |

| F46 | HBA | 22.4 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 19 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/N | - -SEA/N |

| F47 | HBA | 15.5 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 5 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/N | - -SEA/N |

| F48 | HBA | 11.8 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 54 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| F50 | HBA | 16.2 | 49 | 0 | 4 | 0 | Mp | Pp | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/- -SEA | - -SEA/- -SEA |

| F51 | HBA | 13.7 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 35 | Mp | Pn | 100 | 100 | - -SEA/N | - -SEA/N |

| F52 | HBA | 10.7 | 0 | 42 | 27 | 0 | Mn | Pp | 100 | 100 | N/ααCS | N/ααCS |

| F54 | HBA | 12.8 | 0 | 44 | 42 | 0 | Mn | Pp | 100 | 100 | N/- -SEA | N/- -SEA |

| F56 | HBA | 18.0 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 8 | Mn | Pn | 100 | 100 | N/N | N/N |

| 7 fetuses received only one allele genotype | ||||||||||||

| F23 | HBB | 14.0 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | Mp | NC [*] | 99 | 98 | c.316-197C>T/NC | c.316-197C>T/c.316-197C>T |

| F49 | HBA | 13.6 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | NC [*] | Pp | 83 | 100 | NC/- -SEA | - -SEA/- -SEA |

| F53 | HBA | 21.9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 35 | NC [*] | Pn | 89 | 100 | NC/N | N/N |

| F55 | HBA | 9.0 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Mp [**] | NC [*] | 100 | 79 | - -SEA/NC | N/ααCS |

| F57 | HBA | 21.4 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Mp | NC [*] | 100 | 0 | - -SEA/NC | - -SEA/N |

| F58 | HBA | 22.9 | 61 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Mp | NC [*] | 100 | 0 | - -SEA/NC | - -SEA/- -SEA |

| F59 | HBA | 14.4 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Mp | NC [*] | 100 | 93 | - -SEA/NC | - -SEA/- -SEA |

Abbreviations: FF, fetal fraction; No., number; NIPT, noninvasive prenatal testing; N, normal allele; NC, no-call; Hb CS, HBA2 c.427T>C; Hb Westmead (WS), HBA2:c.369C>G; Mat Hap, fetal inheritance from maternal haplotype; Pat Hap, fetal inheritance from paternal haplotype; , confidence score for fetal inheritance from maternal haplotype; , confidence score for fetal inheritance from paternal haplotype; Mp, maternal pathogenic haplotype, Pp, paternal pathogenic haplotype; Mn, maternal normal haplotype; Pn, paternal normal haplotype; SNPs for Mp/Pp, the number of informative SNPs that supported fetal inheritance from parental pathogenic haplotypes; SNPs for Mn/Pn; the number of informative SNPs that supported fetal inheritance from parental normal haplotypes

*No-call: confidence score less than 0.99. **The NIPT result of maternal inheritance for F55 was inconsistent with the invasive prenatal diagnosis result

Fig. 2.

Outcomes of PBH-NIPT. We performed PBH-NIPT on 59 couples. Fifty-nine fetuses had 111 total alleles confirmed by invasive prenatal diagnosis, with 99.1% accuracy (95% CI, 95.1–100%). Fifty-two fetuses had both alleles detected for a total of 104 alleles; 7 fetuses had only one allele detected

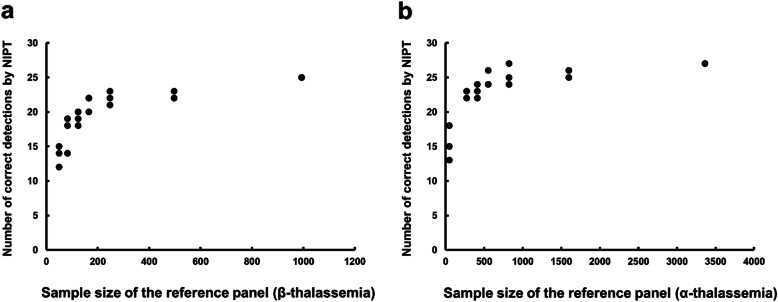

To evaluate the relationship between the accuracy of NIPT and the reference panel sample size, we randomly selected one-half, one-quarter, one-sixth, one-eighth, one-twelfth, and 50 of the samples from the total reference panel and performed three independent tests. As expected, in the 52 fetuses in whom NIPT inferred both alleles, the NIPT outcome improved as the reference panel sample size increased (Fig. 3). Reduction of the sample size to one-half of the total reference panel yielded accuracies of NIPT of approximately 89.3% for β-thalassemia and 95.1% for α-thalassemia relative to the invasive prenatal diagnosis results.

Fig. 3.

Effect of the reference panel sample size on the outcomes of PBH-NIPT. We randomly extracted one-half, one-quarter, one-sixth, one-eighth, one-twelfth, and 50 of the samples from the total reference panel and performed three independent tests for a β-thalassemia and b α-thalassemia. In the 52 fetuses in whom NIPT successfully inferred both alleles, the outcome of NIPT improved as the sample size of the reference panel increased

Discussion

This study demonstrated the feasibility of PBH-NIPT for thalassemia. PBH-NIPT can be used after carrier screening for thalassemia. For high-risk couples reluctant to undergo an invasive procedure, PBH-NIPT is a more attractive option, requiring only a simple blood draw from the pregnant woman. For most conditions, including the deduction of carrier and normal individuals using NIPT, no further confirmation is needed. For conditions where NIPT detects an affected fetus (12 cases) or detects only one pathogenic allele (6 cases), invasive prenatal diagnosis is recommended. In our study, PBH-NIPT dramatically reduced the number of invasive prenatal diagnosis required by approximately 69.5% (from 59 to 18 fetuses).

Here, NIPT successfully inferred 94.1% of the fetal alleles (111/118) from the 59 fetuses. Focusing on the 7 no-call cases clearly shows that the number of informative SNPs in all 7 cases was fewer than 3. This problem can be resolved by increasing the number of informative SNPs flanking the target gene through expansion of the target region [33]. Moreover, this study demonstrated that the reference panel size could affect the performance of NIPT. However, the reference panel size is not a limiting factor since large-scale expanded carrier screening for recessive monogenic disorders is common in clinical practice [40].

This study aimed to evaluate and provide a simple, fast, and inexpensive NIPT method for thalassemia. Compared with the current linked-read sequencing-based NIPT method, which requires 15–20 days (10 days of wet lab work and 5–10 days of data analysis) [25], PBH-NIPT requires only 5–7 days (4–5 days of wet lab work and 1–2 days of data analysis). Training PBH on a large reference panel requires only a few minutes [41]. The PBH-NIPT method costs approximately 80 dollars, as estimated in the supplement (Additional file 8: Table S4). Considering the cost of invasive prenatal diagnosis (~ 1000 dollars/sample [42]) testing in 6 cases, the actual cost of PBH-NIPT per sample is 174 dollars, which is significantly less than those of molecular haplotyping (~ 1500 dollars/sample [25]) and invasive prenatal diagnosis (~ 1000 dollars/sample [42]).

This study has two limitations. First, since all 59 families and training reference data were from southern China, the test cannot detect individuals with ethnic backgrounds differing from those in the training population. Currently, we can only consult ethnic information based on self-reports before testing. A potentially good solution would be to add a quantifiable QC parameter to provide guidance for the reliability of the test. Therefore, we will consider including SNPs that are able to distinguish ethnic information when designing the next version of the probe [43]. Second, the population frequency of these 10 variants was 0.15~2.66% in our dataset [35], and more data are needed to validate whether PBH-NIPT is able to detect variants with lower frequencies.

Conclusions

In summary, we developed and verified PBH-NIPT, a novel method for prenatal testing of α-thalassemia and β-thalassemia. Compared with invasive prenatal diagnosis, this method achieved 99.1% accuracy (95% CI, 95.1–100%). Therefore, we propose that this strategy might be extended to detect variants in addition to single-haplotype founder variants in other recessive monogenic disorders. Additional studies with larger sample sizes are required to confirm the application and performance of PBH-NIPT for other populations and variants with lower frequencies.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Variant spectrum of thalassemia in our published data [35].

Additional file 2: Table S1. Clinical information of the participating families.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Methods.

Additional file 4: Table S2. Characteristics of the 59 families.

Additional file 5: Fig. S2. Concordance of parental haplotypes deduced by PBH and FBH.

Additional file 6: Table S3. Concordance of parental haplotypes deduced by PBH and FBH.

Additional file 7: Fig. S3. NIPT results for thalassemia.

Additional file 8: Table S4. Cost and turnaround time of PBH-NIPT.

Additional file 9: Source data for Fig. 3.

Additional file 10: Source data for Fig. S1.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the affected families participating in the study. We also thank the medical staff of Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center for help with acquiring the blood samples, and we thank the sequencing and bioinformatic center of BGI-Tianjin for data procurement and transmission.

Abbreviations

- NIPT

Noninvasive prenatal testing

- FBH

Family-based haplotyping

- PBH-NIPT

Population-based haplotyping-NIPT

- HMM

Hidden Markov model

- cfDNA

Cell-free DNA

- RMD

Relative mutation dosage

- RHDO

Relative haplotype dosage

- SNVs

Single nucleotide variants

- InDels

Small insertions/deletions

- CNVs

Copy number variants

- TLA

Targeted locus amplification

- FF

Fetal fraction

- gDNA

Genomic DNA

- SNPs

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms

- CS

Confidence score

- AF

Amniotic fluid

- CVS

Chorionic villus sample

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- ssDNA

Single-stranded DNA

- DNBs

DNA nanoballs

- RDB-PCR

Reverse dot blot PCR

Authors’ contributions

CC, ZP, and CL designed the study. LJ, XA, FZ, and LF conducted the experiments. JS, YZ, FG, YW, and PN conducted the statistical analyses. RL, JL, FF, and JW validated the NIPT results. CC and JS drafted and revised the paper. ZP, CL, BX, YY, JS, YD, YS, XG, SZ, and WW supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Major Technical Innovation Project of Hubei Province (No. 2017ACA097), the Special Foundation for High-level Talents of Guangdong (No. 2016TX03R171), and the Shenzhen Municipal Government of China (No. JCYJ20170412152854656). The funding body played no role in the design of this study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. Nonidentifiable data of 59 families generated during this study are deposited in the CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive (CNSA: https://db.cngb.org/search/project/CNP0000644/) with accession number CNP0000644 [44]. The above data have also been deposited in the European Variation Archive (EVA: https://wwwdev.ebi.ac.uk/eva/?eva-study=PRJEB42529) with accession number PRJEB42529 [45]. The raw data of 4356 samples, which was not open to the public in the original paper [35], cannot be submitted to public databases because the patients were not consented for sharing their raw data. The source data used to generate Fig. 3 and Fig. S1 are also available. The customized scripts for PBH and NIPT can be found at https://github.com/liserjrqlxue/NIPT-Thalassemia.

The following open software were used:

Beagle 4.0 (https://faculty.washington.edu/browning/beagle/b4_0.html) [46]

BWA 0.7.12 (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/) [47]

Picard 1.87 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) [48]

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center and BGI approved this study (2017102408 and BGI-IRB 18043). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before sample collection. This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chao Chen, Ru Li and Jun Sun contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Zhiyu Peng, Email: pengzhiyu@bgi.com.

Can Liao, Email: canliao6008@163.com.

References

- 1.Zhang H, Gao Y, Jiang F, Fu M, Yuan Y, Guo Y, et al. Non-invasive prenatal testing for trisomies 21, 18 and 13: clinical experience from 146,958 pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45(5):530–538. doi: 10.1002/uog.14792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong AI, Lo YM. Noninvasive fetal genomic, methylomic, and transcriptomic analyses using maternal plasma and clinical implications. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21(2):98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang D, Cram DS, Tan H, Linpeng S, Liu Y, Sun H, et al. Clinical utility of noninvasive prenatal screening for expanded chromosome disease syndromes. Genet Med. 2019;21(9):1998–2006. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0467-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lo KK, Karampetsou E, Boustred C, McKay F, Mason S, Hill M, et al. Limited clinical utility of non-invasive prenatal testing for subchromosomal abnormalities. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98(1):34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pertile MD, Halks-Miller M, Flowers N, Barbacioru C, Kinnings SL, Vavrek D et al. Rare autosomal trisomies, revealed by maternal plasma DNA sequencing, suggest increased risk of feto-placental disease. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(405):eaan1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Chitty LS, Mason S, Barrett AN, McKay F, Lench N, Daley R, et al. Non-invasive prenatal diagnosis of achondroplasia and thanatophoric dysplasia: next-generation sequencing allows for a safer, more accurate, and comprehensive approach. Prenat Diagn. 2015;35(7):656–662. doi: 10.1002/pd.4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Li J, Saucier JB, Feng Y, Jiang Y, Sinson J, et al. Non-invasive prenatal sequencing for multiple Mendelian monogenic disorders using circulating cell-free fetal DNA. Nat Med. 2019;25(3):439–447. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell CJ, Dinwiddie DL, Miller NA, Hateley SL, Ganusova EE, Mudge J, et al. Carrier testing for severe childhood recessive diseases by next-generation sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(65):65ra4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christianson A, Howson CP, Modell B. March of dimes: global report on birth defects, the hidden toll of dying and disabled children. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsao DS, Silas S, Landry BP, Itzep NP, Nguyen AB, Greenberg S, et al. A novel high-throughput molecular counting method with single base-pair resolution enables accurate single-gene NIPT. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):14382. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50378-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao GJ, Gronowski AM, Zhao Z. Non-invasive prenatal testing using cell-free fetal DNA in maternal circulation. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;428:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong FC, Lo YM. Prenatal diagnosis innovation: genome sequencing of maternal plasma. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:419–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-091014-115715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu EKL, Hui WWI, Chiu RWK. cfDNA screening and diagnosis of monogenic disorders - where are we heading? Prenat Diagn. 2018;38(1):52–58. doi: 10.1002/pd.5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lun FM, Tsui NB, Chan KC, Leung TY, Lau TK, Charoenkwan P, et al. Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of monogenic diseases by digital size selection and relative mutation dosage on DNA in maternal plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(50):19920–19925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810373105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam KW, Jiang P, Liao GJ, Chan KC, Leung TY, Chiu RW, et al. Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of monogenic diseases by targeted massively parallel sequencing of maternal plasma: application to beta-thalassemia. Clin Chem. 2012;58(10):1467–1475. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.189589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi J, Zhang R, Li J, Zhang R. Novel perspectives in fetal biomarker implementation for the noninvasive prenatal testing. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2019;56(6):374–392. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2019.1631749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang X, Zhou Q, Zhou W, Zhong M, Guo X, Wang X, et al. A cell-free DNA barcode-enabled single-molecule test for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of monogenic disorders: application to beta-thalassemia. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2019;6(11):1802332. doi: 10.1002/advs.201802332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phallen J, Sausen M, Adleff V, Leal A, Hruban C, White J et al. Direct detection of early-stage cancers using circulating tumor DNA. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(403):eaan2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Duan H, Liu N, Zhao Z, Liu Y, Wang Y, Li Z, et al. Non-invasive prenatal testing of pregnancies at risk for phenylketonuria. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019;104(1):F24–FF9. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman AM, Lovejoy AF, Klass DM, Kurtz DM, Chabon JJ, Scherer F, et al. Integrated digital error suppression for improved detection of circulating tumor DNA. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(5):547–555. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scotchman E, Chandler NJ, Mellis R, Chitty LS. Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of single-gene diseases: the next frontier. Clin Chem. 2020;66(1):53–60. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2019.304238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayward J, Chitty LS. Beyond screening for chromosomal abnormalities: advances in non-invasive diagnosis of single gene disorders and fetal exome sequencing. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;23(2):94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snyder MW, Adey A, Kitzman JO, Shendure J. Haplotype-resolved genome sequencing: experimental methods and applications. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16(6):344–358. doi: 10.1038/nrg3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hui WW, Jiang P, Tong YK, Lee WS, Cheng YK, New MI, et al. Universal haplotype-based noninvasive prenatal testing for single gene diseases. Clin Chem. 2017;63(2):513–524. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2016.268375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang SS, Lim BC, Yoo SK, Shin JY, Kim KJ, Seo JS, et al. Targeted linked-read sequencing for direct haplotype phasing of maternal DMD alleles: a practical and reliable method for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):8678. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26941-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vermeulen C, Geeven G, de Wit E, Verstegen M, Jansen RPM, van Kranenburg M, et al. Sensitive monogenic noninvasive prenatal diagnosis by targeted haplotyping. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101(3):326–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burgtorf C, Kepper P, Hoehe M, Schmitt C, Reinhardt R, Lehrach H, et al. Clone-based systematic haplotyping (CSH): a procedure for physical haplotyping of whole genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13(12):2717–2724. doi: 10.1101/gr.1442303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitzman JO, Mackenzie AP, Adey A, Hiatt JB, Patwardhan RP, Sudmant PH, et al. Haplotype-resolved genome sequencing of a Gujarati Indian individual. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(1):59–63. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peters BA, Kermani BG, Sparks AB, Alferov O, Hong P, Alexeev A, et al. Accurate whole-genome sequencing and haplotyping from 10 to 20 human cells. Nature. 2012;487(7406):190–195. doi: 10.1038/nature11236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selvaraj S, J RD, Bansal V, Ren B. Whole-genome haplotype reconstruction using proximity-ligation and shotgun sequencing. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31(12):1111–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Amini S, Pushkarev D, Christiansen L, Kostem E, Royce T, Turk C, et al. Haplotype-resolved whole-genome sequencing by contiguity-preserving transposition and combinatorial indexing. Nat Genet. 2014;46(12):1343–1349. doi: 10.1038/ng.3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang K, Zhu J, Shendure J, Porreca GJ, Aach JD, Mitra RD, et al. Long-range polony haplotyping of individual human chromosome molecules. Nat Genet. 2006;38(3):382–387. doi: 10.1038/ng1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeevi DA, Altarescu G, Weinberg-Shukron A, Zahdeh F, Dinur T, Chicco G, et al. Proof-of-principle rapid noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of autosomal recessive founder mutations. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(10):3757–3765. doi: 10.1172/JCI79322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rund D, Rachmilewitz E. Beta-thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(11):1135–1146. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shang X, Peng Z, Ye Y, Asan, Zhang X, Chen Y et al. Rapid targeted next-generation sequencing platform for molecular screening and clinical genotyping in subjects with hemoglobinopathies. EBioMedicine. 2017;23:150–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Yin A, Li B, Luo M, Xu L, Wu L, Zhang L, et al. The prevalence and molecular spectrum of alpha- and beta-globin gene mutations in 14,332 families of Guangdong Province, China. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao C, Yin AH, Peng CF, Fu F, Yang JX, Li R, et al. Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of common aneuploidies by semiconductor sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(20):7415–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321997111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ye J, Chen C, Yuan Y, Han L, Wang Y, Qiu W, et al. Haplotype-based noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of hyperphenylalaninemia through targeted sequencing of maternal plasma. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):161. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18358-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piel FB, Weatherall DJ. The alpha-thalassemias. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1908–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haque IS, Lazarin GA, Kang HP, Evans EA, Goldberg JD, Wapner RJ. Modeled fetal risk of genetic diseases identified by expanded carrier screening. JAMA. 2016;316(7):734–742. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miar Y, Sargolzaei M, Schenkel FS. A comparison of different algorithms for phasing haplotypes using Holstein cattle genotypes and pedigree data. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100(4):2837–2849. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris RA, Washington AE, Nease RF, Jr, Kuppermann M. Cost utility of prenatal diagnosis and the risk-based threshold. Lancet. 2004;363(9405):276–282. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang T, Shu Y, Cai YD. Genetic differences among ethnic groups. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:1093. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2328-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen C, Li R, Sun J, Zhu Y, Jiang L, Li J, et al. Noninvasive prenatal testing of α-thalassemia and β-thalassemia through population-based parental haplotyping. Datasets. China National Genebank (CNGB) Nucleotide Sequence Archive (CNSA). 2020. https://db.cngb.org/search/project/CNP0000644/.

- 45.Chen C, Li R, Sun J, Zhu Y, Jiang L, Li J, et al. Noninvasive prenatal testing of α-thalassemia and β-thalassemia through population-based parental haplotyping. European Variation Archive (EVA): Datasets; 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beagle 4.0. https://faculty.washington.edu/browning/beagle/b4_0.html. Accessed 11 Dec 2018.

- 47.BWA 0.7.12. http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/. Accessed 11 Dec 2018.

- 48.Picard 1.87. http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/. Accessed 11 Dec 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Variant spectrum of thalassemia in our published data [35].

Additional file 2: Table S1. Clinical information of the participating families.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Methods.

Additional file 4: Table S2. Characteristics of the 59 families.

Additional file 5: Fig. S2. Concordance of parental haplotypes deduced by PBH and FBH.

Additional file 6: Table S3. Concordance of parental haplotypes deduced by PBH and FBH.

Additional file 7: Fig. S3. NIPT results for thalassemia.

Additional file 8: Table S4. Cost and turnaround time of PBH-NIPT.

Additional file 9: Source data for Fig. 3.

Additional file 10: Source data for Fig. S1.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. Nonidentifiable data of 59 families generated during this study are deposited in the CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive (CNSA: https://db.cngb.org/search/project/CNP0000644/) with accession number CNP0000644 [44]. The above data have also been deposited in the European Variation Archive (EVA: https://wwwdev.ebi.ac.uk/eva/?eva-study=PRJEB42529) with accession number PRJEB42529 [45]. The raw data of 4356 samples, which was not open to the public in the original paper [35], cannot be submitted to public databases because the patients were not consented for sharing their raw data. The source data used to generate Fig. 3 and Fig. S1 are also available. The customized scripts for PBH and NIPT can be found at https://github.com/liserjrqlxue/NIPT-Thalassemia.

The following open software were used:

Beagle 4.0 (https://faculty.washington.edu/browning/beagle/b4_0.html) [46]

BWA 0.7.12 (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/) [47]

Picard 1.87 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) [48]