Abstract

Background

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) can cause premature delivery and stillbirth. Previous studies have reported that mutations in ABC transporter genes strongly influence the transport of bile salts. However, to date, their effects are still largely elusive.

Methods

A whole-exome sequencing (WES) approach was used to detect novel variants. Rare novel exonic variants (minor allele frequencies: MAF < 1%) were analyzed. Three web-available tools, namely, SIFT, Mutation Taster and FATHMM, were used to predict protein damage. Protein structure modeling and comparisons between reference and modified protein structures were performed by SWISS-MODEL and Chimera 1.14rc, respectively.

Results

We detected a total of 2953 mutations in 44 ABC family transporter genes. When the MAF of loci was controlled in all databases at less than 0.01, 320 mutations were reserved for further analysis. Among these mutations, 42 were novel. We classified these loci into four groups (the damaging, probably damaging, possibly damaging, and neutral groups) according to the prediction results, of which 7 novel possible pathogenic mutations were identified that were located in known functional genes, including ABCB4 (Trp708Ter, Gly527Glu and Lys386Glu), ABCB11 (Gln1194Ter, Gln605Pro and Leu589Met) and ABCC2 (Ser1342Tyr), in the damaging group. New mutations in the first two genes were reported in our recent article. In addition, compared to the wild-type protein structure, the ABCC2 Ser1342Tyr-modified protein structure showed a slight change in the chemical bond lengths of ATP ligand-binding amino acid side chains. In placental tissue, the expression level of the ABCC2 gene in patients with ICP was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that in healthy pregnant women. In particular, the patients with two mutations in ABC family genes had higher average values of total bile acids (TBA), aspartate transaminase (AST), direct bilirubin (DBIL), total cholesterol (CHOL), triglycerides (TG) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) than the patients who had one mutation, no mutation in ABC genes and local controls.

Conclusions

Our present study provide new insight into the genetic architecture of ICP and will benefit the final identification of the underlying mutations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-021-03595-x.

Keywords: ICP, WES, TBA, ABC transporter genes, Genetic variants, ABCC2 gene, Ser1342Tyr mutation, Gene expression

Background

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a reversible pregnancy-specific liver disease characterized by pruritus and abnormal liver function, such as elevated liver enzymes and increased serum total bile acids (TBA) (≥ 10 μmol/L), that appears in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy and resolves completely after delivery in the early postpartum period [1]. The incidence of ICP disease is reported to be between 0.1 and 15.6% depending on geographical differences [1, 2]. ICP has been associated with adverse fetal outcomes, including spontaneous preterm birth, respiratory distress, low Apgar scores, fetal distress and fetal death [3–7]. For example, Li Li et al. reported that birth size was reduced, whereas the rate of small-for-gestational-age infants was increased across increasing categories of serum total TBA [8]. It has been noted that approximately 2–4% of ICP pregnancies are affected by fetal mortality [9, 10]. The level of TBA increases the risk of fetal morbidity and stillbirth [11–13]. Therefore, untangling the mechanisms of ICP and its association with fetal complications is very important.

The abnormal synthesis, metabolism transport, secretion and excretion of bile acids may lead to ICP disease [14]. Therefore, the etiology contributing to the development of ICP disease is complex and depends on multiple factors, including hormonal, genetic and environmental backgrounds [15]. Familial clustering analysis in pedigree studies showed a high incidence in mothers and sisters of patients with ICP, which might indicate a genetic predisposition for the condition [16–19]. Among these, gene mutations in the hepatocellular transporters of bile salts play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of ICP [20].

Bile salt transport is the key physiological function of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) membrane proteins, covering seven distinct members: ABCA, ABCB, ABCC, ABCD, ABCE, ABCF and ABCG. Of these genes, ABCB4, ABCB11 and ABCC2 are functionally known genes that affect the development of ICP [21–23]. Except for the ABCB4, ABCB11, ABCC2, ATP8B1, TJP2 and ANO8 genes [23, 24], the role of other ABC transporter genes seems to be less studied. By taking advantage of the high-throughput genotyping technologies in a larger-scale population, the WES approach that combined genotype data for all patients has proven to be far more efficient in anchoring exonic mutations for the target gene at once. In particular, the method can greatly accelerate screening for new potential pathogenicity sites of all mutations. Therefore, examining exonic variants across ICP disease groups likely augments the excavation of novel loci. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of the use of WES to identify the genetic variants in the ABC gene series of bile acid transporters for ICP disease.

ICP is a complex disease that is influenced by multiple genes. Previously, we reported the identification of the novel gene ANO8 as a genetic risk factor for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in 151 ICP samples [24]. In the present study, we hypothesized that genetic variation in ABC transporters confers susceptibility to ICP. Therefore, we performed WES to extensively investigate the presence of mutations, especially for the discovery of new functional variants, of the ABC gene series involved in bile acid transport in 151 patients with ICP disease and related them to the clinical data and pregnancy outcomes.

Methods

Patients and clinical data

A total of 151 pregnant women, who were also used for our previous study [24], were included who did not have other liver diseases and were diagnosed as ICP on the basis of skin pruritus in combination with abnormal liver biochemistry indexes, e.g., TBA, ALT and AST. Among them, the cut-off level of TBA was 10 μmol/L. In addition, 26 clinical features covering six main indicators of maternal and neonatal data, including basic patient features (age, gestational age and body mass index: BMI), ion concentrations (K, Na, Cl, Ca, Mg, and P), routine blood tests (white blood cell count: WBC, red blood cell count: RBC, platelet count: PLT, and red blood cell distribution width.SD: RDW.SD), liver function indexes (TBA, ALT, AST, total bilirubin: TBIL, DBIL, and indirect bilirubin: IDBIL), lipid indexes (CHOL, TG, HDL, low-density lipoprotein: LDL, and uric acid) and outcomes of pregnant women and newborns (birth weight and bleeding amount) were recorded. The concrete methods for these biochemical variables can be found in our previous study [24]. Briefly, the ion concentration, liver function and lipid indexes were determined by an AU5800 automatic biochemical analyzer (Beckman Coulter). Routine blood tests were determined by a Sysmex-xn-2000 automatic blood cell analyzer. We collected all the samples from June 2018 through July 2020. Blood samples were collected from 17 to 41 + 3 weeks of gestation. The delivery gestational age of pregnant women ranged from 28 to 41 + 3 weeks (median: 38 weeks). In addition, we also recruited 1029 pregnant women without ICP disease as negative controls in the same periods, which were also used in our previous study. The controls were in the same gestational age range as the patients with ICP.

Whole-exome sequencing

A total of 151 genomic DNA samples were extracted from peripheral blood by an Axy Prep Blood Genomic DNA Mini prep Kit (Item No. 05119KC3). To fulfill the requirements for genotyping, the concentration and integrity of all the extracted DNA samples were determined by a Nanodrop-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, USA) and gel electrophoresis, respectively. A total of 151 ICP patient samples were subjected to exome capture with a BGI Exon Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocols. DNA libraries were constructed using the combinatorial probe anchor ligation (cPAL) method. Each resulting qualified captured library was then loaded on BGISEQ-500 sequencing platforms. In addition, whole-exome sequencing was also performed in 1029 controls.

Variant annotations, filtering and prioritizing

The bioinformatics analysis began with the sequencing data. We carried out the analysis mainly according to Huusko et al. [25]. Briefly, first, joint contamination and low-quality variants (read depth < 15 and genotype quality score < 20) were removed. The reads were mapped to the reference human genome (UCSC GRCh37/hg19) using BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner) software [26]. After that, variant calls were conducted by GATK (v3.7) [27]. Finally, the ANNOVAR tool was applied to perform a series of annotations [28], such as the frequency in the databases, conservative prediction and pathogenicity prediction with available website tools for variants.

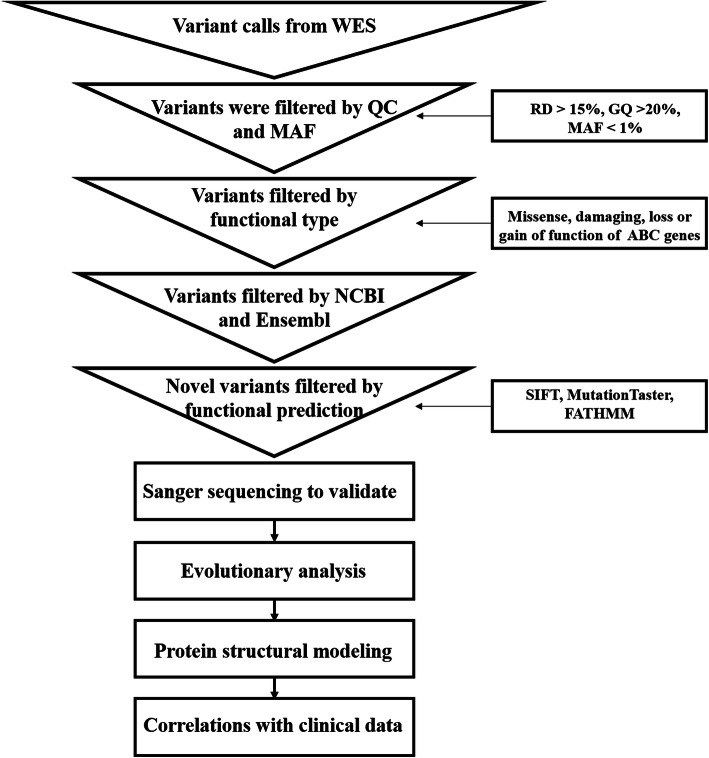

The quality control workflow was carried out as shown in Fig. 1. First, we removed variants with an MAF greater than 0.01 in the 1000 Genomes Project (http://www.internationalgenome.org/), Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/), and dbSNP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/) databases. Second, missense, damaging or loss-of-function variants of ABC genes were included in the subsequent analyses. Third, we concentrated on novel variants that were filtered by NCBI and Ensembl. In addition, we prioritized paying attention to novel variants that would likely have functional effects. For instance, a variant was highlighted when it was predicted to be simultaneously deleterious by SIFT, Mutation Taster and FATHMM software.

Fig. 1.

Overview flow chart of the whole-exome sequencing study for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Statistical analysis

We applied the sapply function to calculate descriptive statistics for clinical data. The Pearson correlation coefficient estimation between clinical data was evaluated by using the cor function [29]. The cor.test function was used to examine the significance of the correlation coefficients. Fisher’s test was used to test the significance of the frequency between 151 patients with ICP and 1029 controls in 3 databases [30]. Moreover, the pie function was used to draw the percentage of all ABC mutations. The comparison of average value differences in six clinical datasets (TBA, AST, DBIL, CHOL, TG and HDL) among the four groups was performed by one-way ANOVA [31]. All the analyses were preformed using R software. In addition, we used three web-available tools, namely, SIFT, Mutation Taster and FATHMM, to predict protein damage. Predictions were defined as damaging, probably damaging, possibly damaging, or neutral when all three prediction tools, two out of three, one out of three and none reached the damaging level, respectively.

Verification of novel candidate sites by sanger sequencing

Since the WES approach is associated with false positive results, the presence of 13 interesting novel mutations from WES analyses was confirmed using Sanger sequencing. The thirteen loci were selected for sequencing mainly based on functional prediction results for mutations (the damaging, probably damaging, possibly damaging, and neutral groups) and classification of members of the ABC transporter gene superfamily (ABCA, ABCB, ABCC, ABCD, ABCE, ABCF and ABCG). The primers were designed by Primer Premier 5 software. The details of the PCR primers and their optimum annealing temperatures are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primes used to confirm the variants in ABC transporter genes

| Order | Gene | Patient | Annealing temperature (°C) | Amplicon (bp) | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ABCA2 | ICP64 | 56 | 229 | CTACCCAGGTCCATCCTGAC | CCACCCACTTGTCCATCTCT |

| 2 | ABCA10 | ICP35 | 56 | 158 | AACCTATGCTCGCTGGTTTG | TGTTCTTACCTGGGCCATTC |

| 3 | ABCA12 | ICP75 | 56 | 150 | CATGGATCCGAAGTCGAAA | ACCTTTTCCCACCTGTCATC |

| 4 | ABCA13 | ICP112 | 56 | 245 | CAAGGACCAAGCATCATTCC | GGGAGGTGGAAGCAGAAGAT |

| 5 | ABCB4 | ICP133, ICP135 | 50 | 200 | ACATTCCAGGTCCTATTT | TCGAGAAGGGTAAGAAAA |

| 6 | ABCB4 | ICP154 | 56 | 463 | CTGTCAAAGAGGCCAACG | GCTTCTGCCCACCACTCA |

| 7 | ABCB5 | ICP47 | 56 | 460 | TCTTACACTAGCCATCCT | CTATTTCCACGACTTACA |

| 8 | ABCB11 | ICP2 | 56 | 205 | GCTATCGCCAGAGCCCTCA | TACTCCCATCCCTCCCACC |

| 9 | ABCC2 | ICP79 | 56 | 368 | CCTCTTACCTCCTGTGAC | GTAGACCGTGGAATTGAC |

| 10 | ABCC3 | ICP93 | 56 | 189 | CCCCAAACTCCTTCTCCC | TGGCATCCACCTTAGTATCA |

| 11 | ABCC9 | ICP124 | 56 | 166 | TCCCACAACCCATTCATCTT | GCCTCTGCCAACTTTGTAGC |

| 12 | ABCG1 | ICP113 | 56 | 212 | CTCACGGTGCCTCTTGACTT | GGTGTCATTCAGGCTGACCT |

| 13 | ABCG2 | ICP6 | 56 | 180 | GTGGCCTTGGCTTGTATGAT | GATGGCAAGGGAACAGAAAA |

Evolutionary conservation analysis

We also selected the same twelve loci as Sanger sequencing for evolutionary conservation analysis for the same reasons. Evolutionary conservation analysis [32, 33] of the amino acids encoded by the new pathogenicity sites in ABC genes was performed among vertebrates, including Gibbon, Macaque, Olive Baboon, Gelada, Marmoset, Mouse, Rat, Cow, Sheep, Pig, Chicken, Zebra Finch, and Zebrafish, using genomic alignments of the Ensembl Genome Browser.

Protein structure modeling

Protein structure modeling involves in two steps. First, the reference and modified (ABCC2 Ser1342Tyr) protein sequences were submitted to SWISS-MODEL (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/) software for structure modeling. Then, these two protein models were compared simultaneously using the Chimera 1.14rc package.

Results

Whole-exome sequencing results of variants of ABC transporter genes in 151 ICP samples

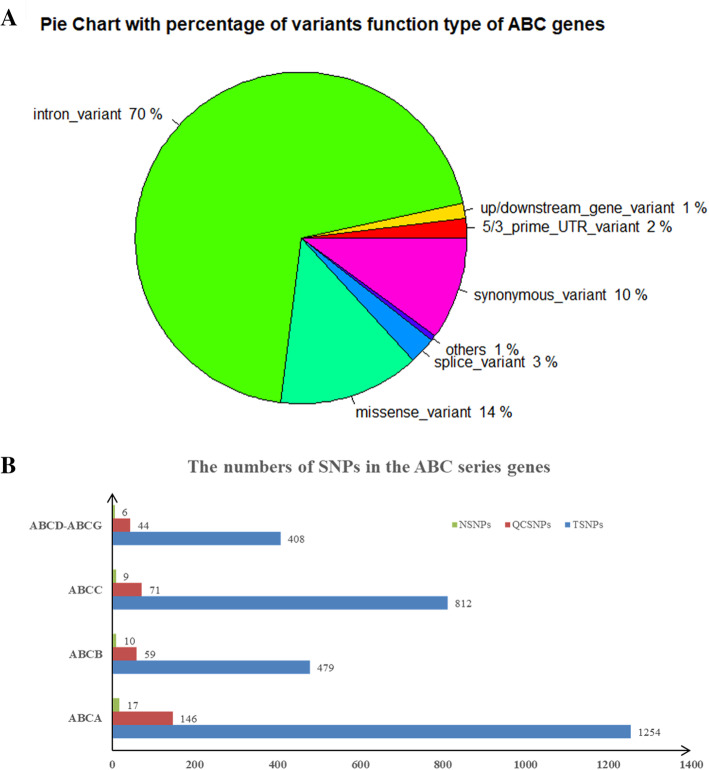

In total, ABC transporters covering 44 genes underwent targeted WES to identify variants in a cohort of 151 patients with ICP disease. Overall, we identified 2953 genetic variants, including 1254 mutations in 12 ABCA genes that consisted of ABCA1-ABCA10 and ABCA12-ABCA13, 479 variants in ABCB1 and ABCB4-ABCB11, 812 genetic variants in eleven genes covering ABCC1-ABCC6 and ABCC8-ABCC12, and 408 variants in the ABCD-ABCG gene series. These types of variants covered 2057 introns, 297 synonymous, 76 splice, 13 stop gained/start lost, 36 3′ primer UTR, 21 5′ primer UTR, 10 downstream gene, 32 upstream gene, 3 structural interaction and 408 missense. The percentage of these types of variants is shown in Fig. 2a. After quality control (MAF < 0.01 in all databases), 42 out of 320 variants were detected that were first reported, including 17 out of 146 variants in ABCA genes, 10 out of 59 in ABCB, 9 out of 71 in ABCC and 6 out of 44 in ABCD-ABCG genes (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

The distribution and numbers of genetic variants from WES data for ICP. a The percentage of the types of genetic variants in the ABC series of genes. b The total number of genetic variants before and after quality control and the novel variants. TSNPs: Total SNPs before quality control; QCSNPs: Total SNPs after quality control; NSNPs: Novel SNPs

For these 42 novel mutations, we classified these mutations as four echelons (damaging, probably damaging, possibly damaging and neutral) according to the prediction results (Table 2). The damage group had fifteen mutations, which contained six mutations in three known functional genes associated with ICP disease, such as ABCB4 Trp708Ter, Gly527Glu and Lys386Glu and ABCB11 Gln1194Ter, Gln605Pro and Leu589Met. These six novel mutations have been shown in our recently published article [24]. In addition, 9 functional mutations were found in other ABC genes, i.e., ABCA4 Phe754Ser, ABCA12 Cys2440Tyr, ABCA13 Ser3286Ter, ABCB1 Pro693Ser, ABCB5 Ser925Ile, ABCC2 Ser1342Tyr ABCC3 Ile1147Thr, ABCC9 Ala456Thr and ABCG2 Leu646Met. The frequency of these mutations in 151 ICP samples reached 10.60% (16/151). Moreover, they were absent in 1029 local healthy women. Therefore, there was a significant difference in frequency between the case and control groups (P = 1.10E-14).

Table 2.

Forty-two potential pathogenic novel ABC mutations were identified in 151 Han Chinese patients with ICP disease

| ID | Gene | Patients | Chr | Position | Alleles | Protein change | SIFTd | Mutation Tastere | FATHMM | Comprehensive prediction resultf | GERP++NRg | PhastCons100way_verh | MAF in controls | MAF in 151 ICP | P value (controls-ICP) | MAF in databases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ABCA4 | ICP76 | chr1 | 94,522,278 | A/G | Phe754Ser | 0.001 (D) | 0.999 (D) | −4.24 (D) | Damaging | 5.66 | 1 | 0/(2*1029) | 10.60% (16/151) | 1.10E-14 | Absent in 1000G/ExAC/dbSNP/ChinaMAP databases |

| 2 | ABCA12a,b | ICP75 | chr2 | 215,809,749 | C/T | Cys2440Tyr | 0.041 (D) | 1 (D) | −3.67 (D) | Damaging | 5.49 | 1 | ||||

| 3 | ABCA13a | ICP112 | chr7 | 48,354,004 | C/G | Ser3286Ter | – | 1 (A) | – | Damaging | 5.68 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | ABCB1 | ICP121 | chr7 | 87,173,579 | G/A | Pro693Ser | 0.031 (D) | 1 (D) | −2.21 (D) | Damaging | 5.91 | 1 | ||||

| 5 | ABCB4 | ICP21 | chr7 | 87,053,310 | C/T | Trp708Ter | – | 1 (A) | – | Damaging | 6.11 | 1 | ||||

| 6 | ABCB4a,b | ICP154 | chr7 | 87,069,134 | C/T | Gly527Glu | 0.0 (D) | 1 (D) | −2.35 (D) | Damaging | 5.61 | 0.999 | ||||

| 7 | ABCB4a,b | ICP133,135 | chr7 | 87,073,053 | T/C | Lys386Glu | 0.002 (D) | 1 (D) | −2.65 (D) | Damaging | 5.47 | 0.999 | ||||

| 8 | ABCB5a,b | ICP47 | chr7 | 20,767,985 | G/T | Ser925Ile | 0.002 (D) | 0.786 (D) | −2.5 (D) | Damaging | 3.91 | 0.999 | ||||

| 9 | ABCB11 | ICP115 | chr2 | 169,783,704 | G/A | Gln1194Ter | – | 1 (A) | – | Damaging | 5.72 | 0.993 | ||||

| 10 | ABCB11 | ICP118 | chr2 | 169,826,057 | T/G | Gln605Pro | 0.006 (D) | 0.972 (D) | −1.99 (D) | Damaging | 5.5 | 0.835 | ||||

| 11 | ABCB11a,b | ICP2 | chr2 | 169,826,599 | G/T | Leu589Met | 0.0 (D) | 0.994 (D) | −2.82 (D) | Damaging | 5.2 | 0.959 | ||||

| 12 | ABCC2a,b,c | ICP79 | chr10 | 101,605,418 | C/A | Ser1342Tyr | 0.0 (D) | 0.999 (D) | −2.95 (D) | Damaging | 5.79 | 1 | ||||

| 13 | ABCC3a,b | ICP93 | chr17 | 48,755,166 | T/C | Ile1147Thr | 0.0 (D) | 1 (D) | −2.57 (D) | Damaging | 5.7 | 1 | ||||

| 14 | ABCC9a,b | ICP124 | chr12 | 22,061,100 | C/T | Ala456Thr | 0.001 (D) | 1 (D) | −2.58 (D) | Damaging | 5.29 | 1 | ||||

| 15 | ABCG2a,b | ICP6 | chr4 | 89,013,418 | G/T | Leu646Met | 0.01 (D) | 0.998 (D) | −2.33 (D) | Damaging | 5.55 | 1 | ||||

| 16 | ABCA2a,b | ICP64 | chr9 | 139,910,497 | G/C | Asp1108Glu | 0.043 (D) | 0.999 (N) | −3.27 (D) | Pro damaging | 4.2 | 1 | 0/(2*1029) | 13.91% (21/151) | 2.20E-16 | Absent in 1000G/ExAC/dbSNP/ChinaMAP databases |

| 17 | ABCA2 | ICP19 | chr9 | 139,913,419 | G/A | Ala583Val | 0.351 (T) | 0.999 (D) | −2.17 (D) | Pro damaging | 4.31 | 0.94 | ||||

| 18 | ABCA5 | ICP102 | chr17 | 67,266,794 | A/G | Val997Ala | 0.527 (T) | 0.961 (D) | −1.77 (D) | Pro damaging | 5.45 | 1 | ||||

| 19 | ABCA7 | ICP108 | chr19 | 1,045,131 | C/A | Pro449His | 0.015 (D) | 1 (N) | −4.44 (D) | Pro damaging | 3.05 | 0 | ||||

| 20 | ABCA8 | ICP47 | chr17 | 66,938,153 | A/G | Val8Ala | 0.009 (D) | 0.984 (N) | −2.41 (D) | Pro damaging | 4.84 | 0.018 | ||||

| 21 | ABCA10a,b | ICP35 | chr17 | 67,212,035 | A/G | Leu260Ser | 0.038 (D) | 1 (N) | −2.28 (D) | Pro damaging | 3.21 | 0.003 | ||||

| 22 | ABCA12 | ICP95 | chr2 | 215,865,543 | A/G | Ile1022Thr | 0.093 (T) | 0.994 (D) | −3.77 (D) | Pro damaging | 5.73 | 1 | ||||

| 23 | ABCA13 | ICP18 | chr7 | 48,559,709 | C/G | Leu4624Val | 0.017 (D) | 0.954 (N) | −2.477 (D) | Pro damaging | 5.35 | 0.702 | ||||

| 24 | ABCA13 | ICP107 | chr7 | 48,634,399 | A/G | Thr4912Ala | 0.001 (D) | 0.958 (N) | −5.88 (D) | Pro damaging | 5.7 | 1 | ||||

| 25 | ABCB9 | ICP112 | chr12 | 123,430,667 | C/T | Glu386Lys | 0.891 (T) | 0.682 (D) | −2.4 (D) | Pro damaging | 5 | 0.979 | ||||

| 26 | ABCB9 | ICP140 | chr12 | 123,433,209 | T/C | Ile339Val | 0.176 (T) | 0.999 (D) | −2.6 (D) | Pro damaging | 5.43 | 1 | ||||

| 27 | ABCC1 | ICP98 | chr16 | 16,149,964 | A/G | Ser497Gly | 0.268 (T) | 0.972 (D) | −2.71 (D) | Pro damaging | 5.32 | 1 | ||||

| 28 | ABCC3 | ICP57 | chr17 | 48,734,467 | C/T | Leu137Phe | 0.011 (D) | 1 (D) | 0.85 (T) | Pro damaging | 5.38 | 1 | ||||

| 29 | ABCC5 | ICP49 | chr3 | 183,670,989 | T/G | Gln851Pro | 0.026 (D) | 0.999 (D) | 0.95 (T) | Pro damaging | 5.62 | 1 | ||||

| 30 | ABCC6 | ICP57 | chr16 | 16,259,657 | G/T | His1043Gln | 0.029 (D) | 0.999 (N) | −3.35 (D) | Pro damaging | 5.52 | 1 | ||||

| 31 | ABCC9 | ICP36 | chr12 | 21,968,809 | T/A | Glu1304Val | 0.111 (T) | 0.999 (D) | −2.61 (D) | Pro damaging | 4.95 | 1 | ||||

| 32 | ABCC12 | ICP155 | chr16 | 48,180,227 | G/A | Pro37Ser | 0.217 (T) | 0.812 (D) | −2.76 (D) | Pro damaging | 5.45 | 0.974 | ||||

| 33 | ABCD4 | ICP95 | chr14 | 74,757,137 | G/A | Ser395Phe | 0.033 (D) | 0.983 (N) | −2.77 (D) | Pro damaging | 4.84 | 0.875 | ||||

| 34 | ABCD4 | ICP142 | chr14 | 74,757,168 | T/C | Thr385Ala | 0.254 (T) | 0.990 (D) | −2.63 (D) | Pro damaging | 4.84 | 1 | ||||

| 35 | ABCF2 | ICP84 | chr7 | 150,923,406 | C/T | Gly47Ser | 0.156 (T) | 0.999 (D) | −2.77 (D) | Pro damaging | 4.81 | 1 | ||||

| 36 | ABCG1a,b | ICP113 | chr21 | 43,704,752 | A/G | Ile273Val | 0.002 (D) | 1 (D) | 0.52 (T) | Pro damaging | 4.22 | 1 | ||||

| 37 | ABCA3 | ICP22 | chr16 | 2,348,506 | T/C | Ser593Gly | 0.126 (T) | 1 (N) | −3.3 (D) | Pos damaging | 6.17 | 0.005 | 0/(2*1029) | 3.31% (5/151) | 3.74E-08 | Absent in 1000G/ExAC/dbSNP/ChinaMAP databases |

| 38 | ABCA10 | ICP64 | chr17 | 67,181,648 | G/C | Leu823Val | 0.09 (T) | 1 (N) | −2.19 (D) | Pos damaging | 2.92 | 0.011 | ||||

| 39 | ABCA12 | ICP71 | chr2 | 215,802,301 | T/C | Asn2492Ser | 0.403 (T) | 0.958 (N) | −2.28 (D) | Pos damaging | 5.79 | 0.999 | ||||

| 40 | ABCA13 | ICP111 | chr7 | 48,349,554 | G/A | Ser3111Asn | 0.071 (T) | 0.999 (N) | −2.11 (D) | Pos damaging | 5.59 | 0.354 | ||||

| 41 | ABCG1 | ICP22 | chr21 | 43,708,158 | C/T | Thr378Ile | 0.21 (T) | 1 (N) | −1.98 (D) | Pos damaging | 4.17 | 0 | ||||

| 42 | ABCA13 | ICP52 | chr7 | 48,318,169 | A/G | Ile2460Val | 0.916 (T) | 1 (N) | 0.66 (T) | Neutral | 4.92 | 0 | 0/(2*1029) | 0.66% (1/151) | 0.13 | Absent in 1000G/ExAC/dbSNP/ChinaMAP databases |

a These loci were validated by Sanger sequencing

b These loci were identified by evolutionary conservation analysis

c The effect of the change in this mutation on the encoded protein structure

d D: disease-causing, T: tolerated

e N: polymorphism, A: automatically disease causing

f Pro damaging: probably damaging; Pos damaging: possibly damaging

g GERP++NR: GREP++ conservation score. The higher the value is, the more conservative the loci

h PhastCons100way_ver: conservative prediction in 100 vertebrates. The scores of the PhastCons score ranged from 0 to 1, and the higher the values are, the more conservative the loci

Twenty-one mutations were assigned to the second tier (probably damaging), including 9 in ABCA genes (ABCA2 Asp1108Glu and Ala583Val, ABCA5 Val997Ala, ABCA7 Pro449His, ABCA8 Val8Ala, ABCA10 Leu260Ser, ABCA12 Ile1022Thr, ABCA13 Leu4624Val and Thr4912Ala), Glu386Lys and Ile339Val in all ABCB9 genes, 6 in the ABCC gene series (ABCC1 Ser497Gly, ABCC3 Leu137Phe, ABCC5 Gln851Pro, ABCC6 His1043Gln, ABCC9 Glu1034Val and ABCC12 Pro37Ser), ABCD4 Ser395Phe and Thr385Ala, ABCF2 Gly47Ser and ABCG1 Ile273Val in the ABCD-ABCG gene series. These mutations were also absent in controls. The MAF in these mutations between cases and controls showed a significant difference (P = 2.20E-16).

We identified five possible potential pathogenic mutations associated with ICP disease, including ABCA3 Ser593Gly, ABCA10 Leu823Val, ABCA12 Asn2492Ser, ABCA13 Ser3111Asn and ABCG1 Thr378Ile. Only one mutation was placed in the neutral group. All 42 novel mutations were absent in the databases, including the 1000 Genome Project, ExAC, dbSNP, ChinaMAP and 1029 local controls.

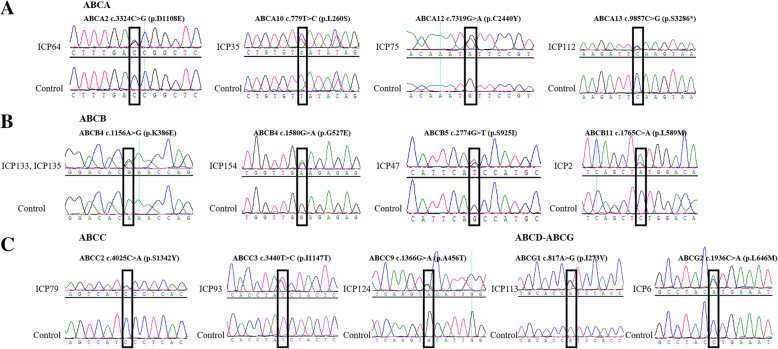

Confirmation of the novel variants by sanger sequencing

We used Sanger sequencing to confirm 13 possible candidate novel pathogenicity loci in the ABC family genes from four lines. The results (Fig. 3) were all consistent with WES.

Fig. 3.

Sanger sequencing to validate the novel variants in the ABC gene series. a ABCA genes; b ABCB genes; c ABCC genes; d ABCD-ABCG genes

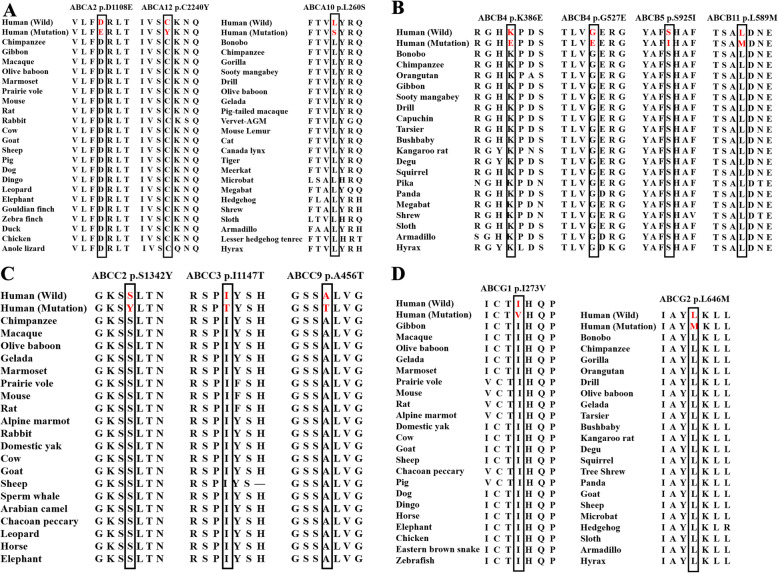

Evolutionary conservation analysis

We performed evolutionary conservation analysis of twelve loci, which were also sequenced by Sanger sequencing. The results suggested that these mutations were highly conserved among vertebrate species, including rats, sheep, cows, pigs, dogs, horses, chickens and so on (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Evolutionary conservation analysis of novel ABC representative mutations. Mutations are highly conserved in vertebrate species

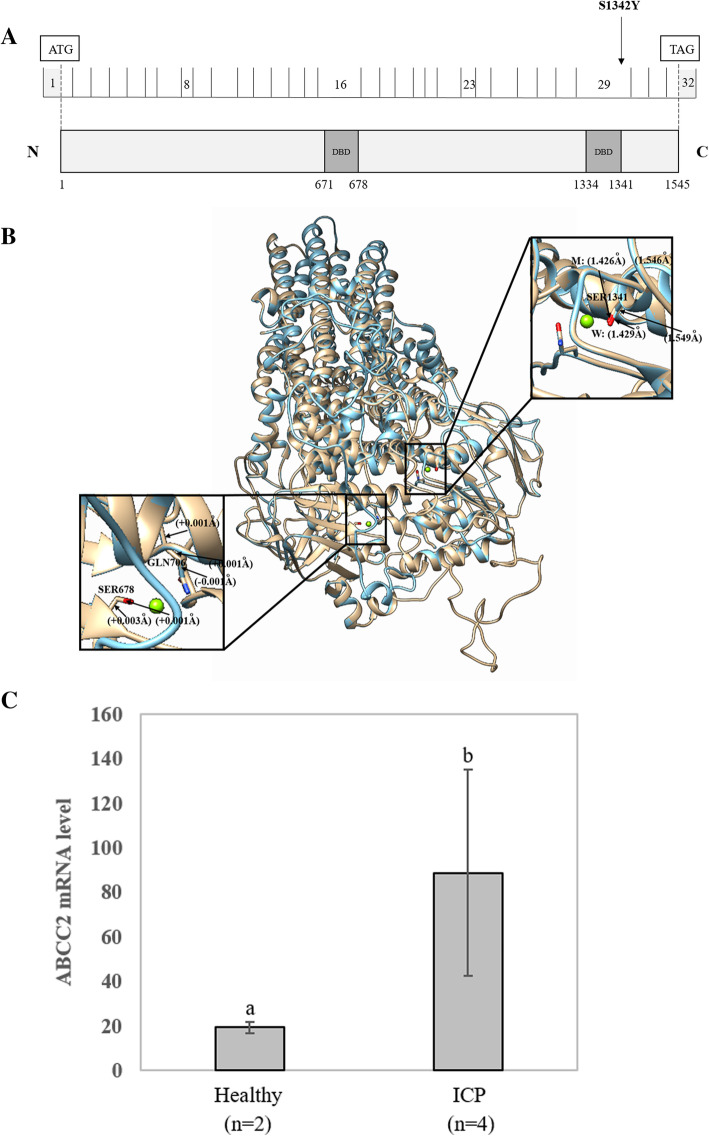

Comparison of the protein structural model of the ABCC2 Ser1342Tyr mutation

ABCC2 consists of 32 exons involved in bile formation that mediate hepatobiliary excretion of numerous organic anions and conjugated organic anions such as methotrexate and transport sulfated bile salts such as taurolithocholate sulfate [34, 35]. This gene has two main nucleotide binding domains located at positions 671–678 and 1334–1341 (Fig. 5a). We only identified the ABCC2 Ser1342Tyr mutation when the quality control of the minor allele frequency was below 0.01. The location of this variant (Ser1342Tyr) is close to the ATP binding functional domain (1334–1341). In addition, the mutation was found to be harmful to the function of the protein according to the results of three prediction software programs.

Fig. 5.

Effects of the ABCC2 Ser1342Tyr variant on the protein sequence and structure. a Distribution of the ABCC2 variants. ABCC2 is a 1545-amino acid protein containing two major nucleotide-binding functional domains (ATP binding cassette domains). The locations of two ABCC2 variants from whole-exome sequencing are shown in the protein sequence. b In silico comparison of the higher assembly of the reference and modified (Ser1342Tyr) ABCC2 protein models. The reference and Ser1342Tyr molecules are presented as gold and blue rounded ribbon structures, respectively. The enlarged image shows that the functional domains have small changes in the chemical bond lengths. DBD: DNA-binding domain. c Comparison of the expression level of the ABCC2 gene between two healthy controls and four patients with ICP. Different letters above the expression column denote significant differences (P < 0.05)

To further investigate the possible effects of the missense variant on protein structure, the reference and modified protein structures of the ABCC2 gene were compared simultaneously using UCSF Chimera 1.14rc. The results showed that, compared with the reference molecular structure, the 3D model of mutation had a slight change in the chemical bond lengths of ATP-ligand binding amino acid side chains at positions Ser1342, Ser678 and Gln706 (Fig. 5b). The change in the amino side chains could affect the binding efficiency of the ATP molecule.

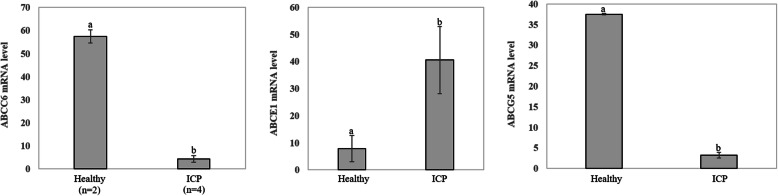

In this study, we did not collect placental tissue from these 151 patients with ICP. Therefore, to further analyze the genetic basis of ABCC2, we analyzed the mRNA expression level of the ABCC2 gene in placental tissue between 2 healthy participants and four patients with ICP using GEO datasets derived from NCBI (GEO accession: GSE46157) from Du Q et al.’s report [36]. A significant (P < 0.05) difference in gene expression was observed between the two groups (Fig. 5c). The expression of ABCC2 was upregulated in the ICP group. In addition, we also detected that the expression of three other genes, namely, ABCC6, ABCE1 and ABCG5, changed in placental tissue (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the expression levels of the ABCC6, ABCE1 and ABCG5 genes in placental tissue between two healthy controls and four patients with ICP

Correlations among clinical data

We examined the correlation coefficients (Supplementary file 1) among these 26 clinical features and found that TBA was significantly negatively correlated with gestation days (r = − 0.34), birth weight (r = − 0.30), and RDW.SD (r = − 0.16) and significantly positively correlated with TBIL (r = 0.52), DBIL (r = 0.56), IDBIL (r = 0.18), ALT (r = 0.17), and AST (r = 0.18). There was also a close relationship among liver function indexes. For example, ALT was highly positively correlated with AST (r = 0.93). ALT and AST were positively correlated with TBIL and DBIL. TBIL positively correlated with DBIL (r = 0.89). CHOL, TG, LDL and uric acid were also positively correlated with ALT and AST. In addition, the concentrations of Ca and Mg ions were positively correlated with AST. The correlations between the abovementioned clinical data were significant (P < 0.05).

Biochemical and clinical features of ICP cases with variants

Descriptive statistics of 26 clinical features for patients with ICP with 42 new mutations are shown in Table 3. For all the clinical data, the levels of ALT, AST, TBA, DBIL, CHOL and TG in 151 patients with ICP disease were higher than the reference levels. Notably, individuals with the novel ABC mutations had a fourfold higher TBA and twofold higher ALT, AST, and TG average values than the reference values, which confirms that ICP disease presents with abnormal liver function and elevated bile acids associated with abnormal lipid metabolism. Compared to the ICP group without the 42 novel mutations, the group with the 42 novel mutations had a higher age, BMI, and levels of K, Na, Cl, RBC, TBIL, IDBIL, TG, and HDL.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of 26 clinical features of ICP individuals associated with/without 42 novel mutations

| Features | ICP with 42 novel mutations | ICP without 42 novel mutations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | P | |

| Basic information | |||||||||||

| Age (years) | 37 | 29.54 | 5.75 | 17.00 | 41.00 | 113 | 29.35 | 5.12 | 20.00 | 43.00 | 0.84 |

| Gestational age (days) | 34 | 254.03 | 22.68 | 196.00 | 290.00 | 110. | 260.04 | 18.05 | 204.00 | 290.00 | 0.06 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31 | 26.91 | 3.78 | 21.50 | 36.30 | 106 | 25.46 | 3.22 | 19.60 | 38.50 | 0.037 |

| Ion concentrations | |||||||||||

| K (mmol/L) | 34 | 4.04 | 0.30 | 3.60 | 4.90 | 106 | 3.99 | 0.32 | 3.20 | 4.80 | 0.44 |

| Na (mmol/L) | 34 | 137.71 | 2.70 | 133.00 | 143.00 | 105 | 137.36 | 2.27 | 132.00 | 143.00 | 0.47 |

| Cl (mmol/L) | 34 | 104.26 | 2.81 | 97.00 | 110.00 | 105 | 104.08 | 2.80 | 98.00 | 112.00 | 0.73 |

| Ca (mmol/L) | 34 | 2.31 | 0.15 | 2.09 | 2.80 | 105 | 2.31 | 0.16 | 2.00 | 2.90 | 0.86 |

| Mg (mmol/L) | 34 | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 1.10 | 105 | 0.82 | 0.16 | 0.65 | 1.89 | 0.36 |

| P (mmol/L) | 34 | 1.10 | 0.17 | 0.72 | 1.50 | 105 | 1.13 | 0.18 | 0.70 | 1.60 | 0.51 |

| Routine blood tests | |||||||||||

| WBC (×109) | 36 | 8.21 | 1.97 | 4.94 | 13.36 | 113 | 8.66 | 3.07 | 4.37 | 24.23 | 0.30 |

| RBC (×109) | 36 | 3.89 | 0.44 | 3.24 | 4.98 | 113 | 3.82 | 0.41 | 2.96 | 4.81 | 0.39 |

| PLT (×109) | 36 | 196.33 | 62.49 | 87.00 | 412.00 | 113 | 198.81 | 63.24 | 75.00 | 377.00 | 0.84 |

| RDW.SD (fL) | 36 | 45.23 | 5.73 | 36.90 | 67.30 | 113 | 46.08 | 4.28 | 36.20 | 62.40 | 0.41 |

| Liver function indexes | |||||||||||

| ALT (U/L) | 37 | 90.81 | 126.35 | 3.00 | 452.00 | 113 | 95.77 | 125.18 | 4.00 | 595.00 | 0.83 |

| AST (U/L) | 37 | 76.35 | 88.34 | 12.00 | 359.00 | 113 | 83.08 | 97.35 | 12.00 | 456.00 | 0.71 |

| TBA (μmol/L) | 37 | 40.58 | 21.96 | 12.50 | 105.80 | 113 | 44.73 | 44.17 | 10.70 | 286.80 | 0.42 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 36 | 14.99 | 8.02 | 6.90 | 41.90 | 112 | 14.85 | 7.54 | 5.70 | 64.80 | 0.92 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 36 | 6.42 | 6.06 | 2.00 | 28.80 | 112 | 6.44 | 5.98 | 0.90 | 49.50 | 0.99 |

| IDBIL (μmol/L) | 36 | 8.57 | 4.41 | 3.50 | 26.90 | 112 | 8.43 | 3.30 | 2.90 | 23.40 | 0.86 |

| Lipid index | |||||||||||

| CHOL (mmol/L) | 35 | 6.35 | 1.66 | 3.35 | 10.50 | 108 | 6.40 | 1.43 | 3.75 | 10.95 | 0.87 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 35 | 3.78 | 1.65 | 2.11 | 10.44 | 108 | 3.54 | 1.54 | 1.20 | 11.10 | 0.44 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 35 | 1.95 | 0.54 | 1.28 | 4.06 | 108 | 1.89 | 0.40 | 0.92 | 3.19 | 0.59 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 35 | 2.68 | 1.41 | 0.19 | 5.96 | 108 | 2.89 | 1.21 | 0.13 | 6.28 | 0.39 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 34 | 313.74 | 91.93 | 131.00 | 574.00 | 106 | 322.41 | 78.30 | 111.00 | 498.00 | 0.59 |

| Outcomes of pregnant women and newborns | |||||||||||

| Birth weight (kg) | 28 | 3.04 | 0.71 | 1.48 | 5.30 | 91 | 3.04 | 0.57 | 1.23 | 4.10 | 0.97 |

| Bleeding amount (ml) | 28 | 240.36 | 62.63 | 150.00 | 400.00 | 86 | 258.84 | 102.10 | 90.00 | 810.00 | 0.27 |

BMI body mass index, WBC white blood cell, RBC red blood cell, PLT platelet, RDW.SD red blood cell distribution width.SD, ALT alanine transaminase, AST aspartate transaminase, TBA total bile acids, TBIL total bilirubin, DBIL direct bilirubin, IDBIL indirect bilirubin, CHOL total cholesterol, TG triglyceride, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein

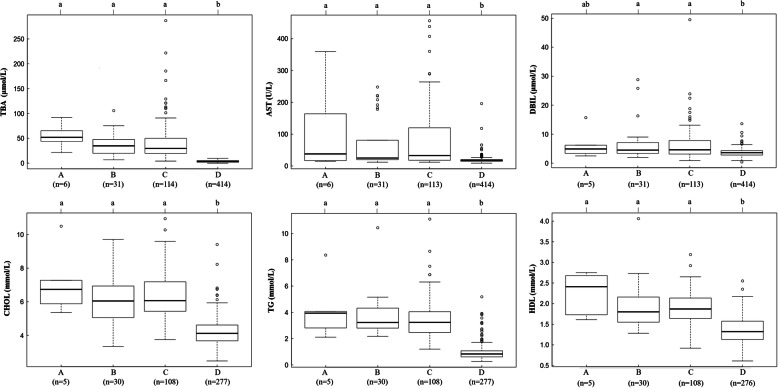

Additionally, we found that six patients with ICP containing two mutations exhibited higher TBA, AST, DBIL, CHOL, TG and HDL than 31 patients with one mutation, 114 patients with ICP with no mutations and 414 local healthy controls (Fig. 7). In particular, for TBA, as a clinical characteristic of ICP, the trends for the average values measured in patients with ICP with mutations of ABC transporter genes and local healthy controls were ranked as follows: ICP with two mutations > ICP with one mutation > ICP with no mutations > healthy controls.

Fig. 7.

Effects of ABC gene mutations on biochemical indexes. The difference in the average TBA, AST, DBIL, CHOL, TG and HDL in the following four groups: a having both mutations, b one mutation, c no mutation in ABC series genes with ICP, and d healthy controls without ICP disease. Means of different groups in rows with different superscript letters are significantly (P < 0.001) different from each other

Discussion

This study is the first to use whole-exome sequencing technology to uncover potential novel pathogenic mutations in ABC family genes involved in bile acid transport. Altogether, we identified 42 new loci covering 44 ABC genes in 151 patients who were diagnosed with ICP disease.

The present study has 4 major strengths. First, following the advent of WES technology, it has proven to be efficient in unearthing sequence variation across the MAF spectrum in obstetric and gynecological diseases [25, 37]. Using this method, we successfully identified novel candidate pathogenicity loci with known functional genes ABCB4, ABCB11 [24] and ABCC2. In addition to these three genes, we also identified some novel variations in other genes in the ABC series. Our results revealed the genetic mutations of the first WES-identified ABC family genes associated with ICP disease. Second, to date, no studies have unraveled the genetic mutations in ABC genes of hepatic disease among pregnant women from a relatively large nationally representative sample (n = 151) in China. Using this same population, we previously identified a novel gene, ANO8, associated with ICP. Moreover, the clinical data of these patients are relatively complete, providing data support for association analysis between mutations and clinical data and subsequent functional verification. Finally, combining WES and clinical data favors deciphering the molecular mechanism of ICP disease.

Certainly, our study also has limitations. First, the WES approach needs a larger sample size to target low-frequency and rare variants. Otherwise, it may miss some valuable variants. Moreover, it also results in inaccurate MAFs for rare variants. However, the strict exclusion conditions guaranteed the selection of a defined cohort, such as employing the MAF in the databases and identifying 151 ICP cases and using 1029 local controls, combined with prediction tools. Second, the samples in this study were all derived from Jiangxi Province, which lacks geographic diversity and may limit the applicability of the generality of these results. However, this study is still valuable due to the high incidence (~ 5%) of ICP in Jiangxi. Next, the frequency of damaging mutations in 151 ICP samples was 10.60%, accounting for only a small portion of the genomic mutations of ICP disease. Therefore, we need to identify more genes/mutations associated with ICP. Finally, our results provided some possible interesting causative mutations; however, the causality between these potential pathogenic candidate loci and ICP disease needs to be verified by validation functional experiments.

Previous studies have detected genetic mutations in ICP primarily by Sanger sequencing or offspring studies based on a limited number of individuals. The rare (MAF < 0.01) variations that affect ICP have been more challenging to assess. Fortunately, WES emerged as an efficient approach to identify exonic mutations in targeted genes. Exonic variants, particularly missense, nonsense, and loss-of-function variants, tend to show the most dramatic effect sizes, possessing greater power for detection. In recent years, in obstetrics and gynecology, there have been a number of examples of using the WES method to search for key candidate genes and causative variants. For instance, Huusko et al., employing WES, revealed that HSPA1L is a genetic risk factor for spontaneous preterm birth [25]. To our knowledge, this study is the largest analysis to date of the role of mutations in the ABC series of genes in 151 ICP-susceptible patients.

Intriguingly, seven novel pathogenic loci in the ABCB4, ABCB11 and ABCC2 genes were simultaneously assigned to the damage group, suggesting the accuracy of our results. Several studies have shown that heterozygous missense mutations in ABCB4, especially low-frequency and rare variations, are commonly responsible for the occurrence of ICP disease, which is consistent with our results [38–40]. After filtering the frequency of the data, we identified a total of eight mutations with a MAF < 0.01, seven of which were heterozygous missense mutations and one of which was a nonsense mutation in ABCB4. The role of ABCB11 in ICP has also been clearly identified, although its contribution seems less than that of ABCB4. A comprehensive analysis of multiple previous studies concluded that up to 5% of ICP cases harbor monoallelic mutations in ABCB11 [41]. Our study confirmed the role of ABCB11 and further expanded the role of the ABCB11 gene.

The function of ABCC2 is related to ICP disease. Therefore, genetic variants of ABCC2 may cause bile acid metabolism disorder. Our results demonstrated a small number of variations, in particular one novel pathogenic heterozygous (ABCC2 Ser1342Tyr) variant. The study of Corpechot C et al. showed that genetic variants of ABCC2 contribute to inherited cholestatic disorders [42]. Moreover, More et al. also found that the expression of ABCC2 was more closely related to the livers from an alcohol cirrhosis cohort, indicating that ABCC2 expression changed in liver-related disease [43], which is consistent with the fact that ICP is a liver disease. For the other three genes that were expressed differently, we found ABCC6 to have a novel mutation, His1043Gln, which was located in the probably damaging group. Therefore, the ABCC6 gene and the His1043Gln locus are of interest in the development of ICP disease. In our study, we failed to detect novel mutations in the ABCE1 and ABCG5 genes; therefore, we conjectured that this is probably because of the low frequency of novel mutations. It might also be that the known mutations in these two genes are associated with ICP, or other patterns of mutations lead to changes in the mRNA expression levels of the two genes. Moreover, compared to healthy samples, the levels of ABCE1 and ABCG5 mRNA expression were upregulated and downregulated in ICP, respectively. A reasonable explanation for this condition is that the unique functions of ABCE1 and ABCG5 lead to different mechanisms of ICP disease.

Because there have been relatively few studies on the genetic basis of ICP disease, many functional genes have not been mined. However, based on previous studies, several researchers found some evidence that certain genes may predispose patients to liver or ICP disease, such as ABCB9 associated with hepatocellular carcinoma and ABCG2 associated with ICP [44, 45]. Therefore, we hypothesized that genetic mutations in these unknown functional genes, excluding ABCB4, ABCB11 and ABCC2, confer susceptibility to ICP, especially in the damaging group. These findings extended the knowledge on the role of mutations and strengthened the understanding of the genetic basis of ICP disease, including many additional ABC family genes.

Bacq et al. suggested that elevations in serum TBA, ALT and AST activity were identified among patients with ICP who have mutations in ABC transporter genes [46]. In agreement with this, our results confirmed that the mutation group containing 42 novel variants was associated with higher TBA, AST, DBIL, CHOL, TG and HDL, especially among the patients with ICP with 15 damaging novel mutations (Table 3, Fig. 7). Furthermore, Piatek K et al. suggested that the analysis of genotype coexistence pointed to the possibility of mutated variants of polymorphisms of genes having a summation effect on the development of ICP disease [47]. Consistent with this result, in our study, we found that six patients with ICP had two mutations at once. Notably, ICP harboring both mutations increased the average TBA level by 17.33, 20.22 and 50.32 μmol/L based on the difference in average TBA levels in ICP with one mutation, no mutation in ABC transporter genes and no mutation in healthy controls, respectively. As expected, AST, DBIL, CHOL, TG and HDL were also increased. A reasonable explanation for this situation is that double mutation has an additive effect on TBA levels, and this accumulation of TBA levels results in ICP exacerbation.

Moreover, significant differences between the wild type and mutant type were seen for the biochemical indexes, which suggested that the accumulation of TBA could lead to lipid abnormalities. Consistent with this result, researchers found that bile acids (BAs), which are well known for their amphipathic nature, are essential to lipid absorption and energy balance in humans [48–50]. Thus, taken together, our study provides additional support for the effect of mutations in ABC family genes on ICP disease and lipid metabolism.

Not surprisingly, to date, there are only a handful of reports of genetic analysis studies for ICP disease. The present findings not only enrich the molecular basis of the known functional genes (such as ABCB4, ABCB11 and ABCC2) but also expand the new candidate genes (ABCA, ABCB, ABCC, and ABCD-ABCG) associated with ICP. Our results support the fact that mutations in ABC transporter genes lead to ICP disease. Therefore, further work on the genetic mutations involved in ICP pathogenesis has the potential to inspire novel therapies for patients with ICP.

Recently, there has been much interest in whether variations in bile salt concentrations and mutations in ABCB4/ABCB11/ABCC2/other new candidate genes could be biomarkers for various forms of drug-induced liver injury [51]. Furthermore, considering the negative effect of ABC mutations on maternal and fetal outcomes, it is important to genotype these mutations to genetically diagnose them in a timely manner and provide immediate attention and treatment for all ICP-susceptible people.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to conduct WES to reveal the genetic variants in ABC family genes associated with ICP disease. We detected 42 novel potential pathogenic mutations in 44 ABC family genes. Among them, seven loci were identified in ABCB4, ABCB11 and ABCC2, and the remaining 35 loci were in other genes. In particular, the 15 novel mutations that were classified as the damaging group were the main focus of further study. Their functional validation and experimental verification need to be further investigated. Moreover, we detected genetic variants that were significantly associated with six biochemical indexes, including TBA, ALT, AST, DBIL, CHOL and TG (P < 0.05). Our findings provide new valuable insights into the genetic basis of ICP disease and suggest potential candidate variants for clinical diagnosis.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Correlation coefficients among twenty-six clinical features. The dots indicate the significant (P < 0.05) correlation coefficients between each pair of features. The size and colors separately represent the degree and direction of correlation coefficients.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our great gratitude to the patients who participated in this study.

Abbreviations

- ICP

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- WES

Whole-exome sequencing

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- TBA

Total bile acid

- BWA

Burrows-Wheeler Aligner

- GATK

Genome Analysis Toolkit

- WBC

White blood cell

- RBC

Red blood cell

- PLT

Platelet

- RDW.SD

Red blood cell distribution width SD

- ALT

Alanine transaminase

- AST

Aspartate transaminase

- TBIL

Total bilirubin

- DBIL

Direct bilirubin

- IDBIL

Indirect bilirubin

- CHOL

Total cholesterol

- TG

Triglyceride

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

Authors’ contributions

XL and HL performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared the figures and drafted the manuscript. SX, XZ, LN, ZhL and MW collected samples. ZeL, JZ and YZ contributed to the concept and design of the study. JZ and YZ performed the experiments, analyzed the data and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the National Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (No. 20202BABL216010 and No. 20192BBG70003) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Grant (No. 2018 M642594). The funders played no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, writing the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study followed the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, ethics approval was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jiangxi Provincial Maternal and Child Health Hospital in China, and each participating woman gave informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no potential conflicts of interest exist.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xianxian Liu and Hua Lai contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jiusheng Zheng, Email: zjsheng@sina.com.

Yang Zou, Email: zouyang81@163.com.

References

- 1.Puljic A, Kim E, Page J, Esakoff T, Shaffer B, LaCoursiere DY, Caughey AB. The risk of infant and fetal death by each additional week of expectant management in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy by gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):667. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reyes H, Gonzalez MC, Ribalta J, Aburto H, Matus C, Schramm G, Katz R, Medina E. Prevalence of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in Chile. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88(4):487–493. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-4-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lammert F, Marschall HU, Glantz A, Matern S. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. J Hepatol. 2000;33(6):1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenyon AP, Piercy CN, Girling J, Williamson C, Tribe RM, Shennan AH. Obstetric cholestasis, outcome with active management: a series of 70 cases. BJOG. 2002;109(3):282–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee RH, Goodwin TM, Greenspoon J, Incerpi M. The prevalence of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in a primarily Latina Los Angeles population. J Perinatol. 2006;26(9):527–532. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee RH, Kwok KM, Ingles S, Wilson ML, Mullin P, Incerpi M, Pathak B, Goodwin TM. Pregnancy outcomes during an era of aggressive management for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25(6):341–345. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1078756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rook M, Vargas J, Caughey A, Bacchetti P, Rosenthal P, Bull L. Fetal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in a northern California cohort. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e28343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L, Chen W, Ma L, Liu ZB, Lu X, Gao XX, Liu Y, Wang H, Zhao M, Li XL, et al. Continuous association of total bile acid levels with the risk of small for gestational age infants. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):9257. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66138-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisk NM, Storey GN. Fetal outcome in obstetric cholestasis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;95(11):1137–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1988.tb06791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alsulyman OM, Ouzounian JG, Ames-Castro M, Goodwin TM. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: perinatal outcome associated with expectant management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(4 Pt 1):957–960. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)80031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geenes V, Chappell LC, Seed PT, Steer PJ, Knight M, Williamson C. Association of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a prospective population-based case-control study. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1482–1491. doi: 10.1002/hep.26617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oztekin D, Aydal I, Oztekin O, Okcu S, Borekci R, Tinar S. Predicting fetal asphyxia in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280(6):975–979. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-1052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brouwers L, Koster MP, Page-Christiaens GC, Kemperman H, Boon J, Evers IM, Bogte A, Oudijk MA. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: maternal and fetal outcomes associated with elevated bile acid levels. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(1):100. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Mil SW, Milona A, Dixon PH, Mullenbach R, Geenes VL, Chambers J, Shevchuk V, Moore GE, Lammert F, Glantz AG, et al. Functional variants of the central bile acid sensor FXR identified in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(2):507–516. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reichert MC, Lammert F. ABCB4 gene aberrations in human liver disease: an evolving Spectrum. Semin Liver Dis. 2018;38(4):299–307. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1667299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirvioja ML, Kivinen S. Inheritance of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in one kindred. Clin Genet. 1993;43(6):315–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1993.tb03826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holzbach RT, Sivak DA, Braun WE. Familial recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a genetic study providing evidence for transmission of a sex-limited, dominant trait. Gastroenterology. 1983;85(1):175–179. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(83)80246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reyes H, Ribalta J, Gonzalez-Ceron M. Idiopathic cholestasis of pregnancy in a large kindred. Gut. 1976;17(9):709–713. doi: 10.1136/gut.17.9.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eloranta ML, Heinonen S, Mononen T, Saarikoski S. Risk of obstetric cholestasis in sisters of index patients. Clin Genet. 2001;60(1):42–45. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.600106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savander M, Ropponen A, Avela K, Weerasekera N, Cormand B, Hirvioja ML, Riikonen S, Ylikorkala O, Lehesjoki AE, Williamson C, et al. Genetic evidence of heterogeneity in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gut. 2003;52(7):1025–1029. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Degiorgio D, Crosignani A, Colombo C, Bordo D, Zuin M, Vassallo E, Syren ML, Coviello DA, Battezzati PM. ABCB4 mutations in adult patients with cholestatic liver disease: impact and phenotypic expression. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51(3):271–280. doi: 10.1007/s00535-015-1110-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Droge C, Bonus M, Baumann U, Klindt C, Lainka E, Kathemann S, Brinkert F, Grabhorn E, Pfister ED, Wenning D, et al. Sequencing of FIC1, BSEP and MDR3 in a large cohort of patients with cholestasis revealed a high number of different genetic variants. J Hepatol. 2017;67(6):1253–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dixon PH, Sambrotta M, Chambers J, Taylor-Harris P, Syngelaki A, Nicolaides K, Knisely AS, Thompson RJ, Williamson C. An expanded role for heterozygous mutations of ABCB4, ABCB11, ATP8B1, ABCC2 and TJP2 in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):11823. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11626-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, Lai H, Zeng X, Xin S, Nie L, Liang Z, Wu M, Chen Y, Zheng J, Zou Y. Whole-exome sequencing reveals ANO8 as a genetic risk factor for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):544. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03240-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huusko JM, Karjalainen MK, Graham BE, Zhang G, Farrow EG, Miller NA, Jacobsson B, Eidem HR, Murray JC, Bedell B, et al. Whole exome sequencing reveals HSPA1L as a genetic risk factor for spontaneous preterm birth. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(7):e1007394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiong X, Yang H, Yang B, Chen C, Huang L. Identification of quantitative trait transcripts for growth traits in the large scales of liver and muscle samples. Physiol Genomics. 2015;47(7):274–280. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00005.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung SH. Stratified Fisher's exact test and its sample size calculation. Biom J. 2014;56(1):129–140. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201300048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma J, Yang J, Zhou L, Ren J, Liu X, Zhang H, Yang B, Zhang Z, Ma H, Xie X, et al. A splice mutation in the PHKG1 gene causes high glycogen content and low meat quality in pig skeletal muscle. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(10):e1004710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan Y, Xing Y, Zhang Z, Ai H, Ouyang Z, Ouyang J, Yang M, Li P, Chen Y, Gao J, et al. A further look at porcine chromosome 7 reveals VRTN variants associated with vertebral number in Chinese and Western pigs. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soffan A, Subandiyah S, Makino H, Watanabe T, Horiike T. Evolutionary Analysis of the Highly Conserved Insect Odorant Coreceptor (Orco) Revealed a Positive Selection Mode, Implying Functional Flexibility. J Insect Sci. 2018;18(6):18. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iey120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayashi H, Takada T, Suzuki H, Onuki R, Hofmann AF, Sugiyama Y. Transport by vesicles of glycine- and taurine-conjugated bile salts and taurolithocholate 3-sulfate: a comparison of human BSEP with rat Bsep. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1738(1–3):54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ito K, Oleschuk CJ, Westlake C, Vasa MZ, Deeley RG, Cole SP. Mutation of Trp1254 in the multispecific organic anion transporter, multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2) (ABCC2), alters substrate specificity and results in loss of methotrexate transport activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(41):38108–38114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du Q, Pan Y, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Zheng Y, Lu L, Wang J, Duan T, Chen J. Placental gene-expression profiles of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy reveal involvement of multiple molecular pathways in blood vessel formation and inflammation. BMC Med Genet. 2014;7:42. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun Y, Li Y, Chen M, Luo Y, Qian Y, Yang Y, Lu H, Lou F, Dong M. A novel silent mutation in the L1CAM gene causing fetal hydrocephalus detected by whole-exome sequencing. Front Genet. 2019;10:817. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dixon PH, Williamson C. The pathophysiology of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2016;40(2):141–153. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamimura K, Abe H, Kamimura N, Yamaguchi M, Mamizu M, Ogi K, Takahashi Y, Mizuno K, Kamimura H, Kobayashi Y, et al. Successful management of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: report of a first Japanese case. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:160. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnston RC, Stephenson ML, Nageotte MP. Novel heterozygous ABCB4 gene mutation causing recurrent first-trimester intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J Perinatol. 2014;34(9):711–712. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dixon PH, van Mil SW, Chambers J, Strautnieks S, Thompson RJ, Lammert F, Kubitz R, Keitel V, Glantz A, Mattsson LA, et al. Contribution of variant alleles of ABCB11 to susceptibility to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gut. 2009;58(4):537–544. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.159541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corpechot C, Barbu V, Chazouilleres O, Broue P, Girard M, Roquelaure B, Chretien Y, Dong C, Lascols O, Housset C, et al. Genetic contribution of ABCC2 to Dubin-Johnson syndrome and inherited cholestatic disorders. Liver Int. 2020;40(1):163–174. doi: 10.1111/liv.14260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.More VR, Cheng Q, Donepudi AC, Buckley DB, Lu ZJ, Cherrington NJ, Slitt AL. Alcohol cirrhosis alters nuclear receptor and drug transporter expression in human liver. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41(5):1148–1155. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.049676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Que KT, Zhou Y, You Y, Zhang Z, Zhao XP, Gong JP, Liu ZJ. MicroRNA-31-5p regulates chemosensitivity by preventing the nuclear location of PARP1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):268. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0930-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 45.Estiu MC, Monte MJ, Rivas L, Moiron M, Gomez-Rodriguez L, Rodriguez-Bravo T, Marin JJ, Macias RI. Effect of ursodeoxycholic acid treatment on the altered progesterone and bile acid homeostasis in the mother-placenta-foetus trio during cholestasis of pregnancy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(2):316–329. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bacq Y, le Besco M, Lecuyer AI, Gendrot C, Potin J, Andres CR, Aubourg A. Ursodeoxycholic acid therapy in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: results in real-world conditions and factors predictive of response to treatment. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49(1):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piatek K, Kurzawinska G, Magielda J, Drews K, Barlik M, Malewski Z, Ozarowski M, Maciejewska M, Seremak-Mrozikiewicz A. The role of ABC transporters' gene polymorphism in the etiology of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Ginekol Pol. 2018;89(7):393–397. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2018.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmad TR, Haeusler RA. Bile acids in glucose metabolism and insulin signalling - mechanisms and research needs. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(12):701–712. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0266-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hofmann AF, Roda A. Physicochemical properties of bile acids and their relationship to biological properties: an overview of the problem. J Lipid Res. 1984;25(13):1477–1489. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)34421-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang DQ, Tazuma S, Cohen DE, Carey MC. Feeding natural hydrophilic bile acids inhibits intestinal cholesterol absorption: studies in the gallstone-susceptible mouse. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285(3):G494–G502. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00156.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aleo MD, Shah F, He K, Bonin PD, Rodrigues AD. Evaluating the role of multidrug resistance protein 3 (MDR3) inhibition in predicting drug-induced liver injury using 125 pharmaceuticals. Chem Res Toxicol. 2017;30(5):1219–1229. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.7b00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Correlation coefficients among twenty-six clinical features. The dots indicate the significant (P < 0.05) correlation coefficients between each pair of features. The size and colors separately represent the degree and direction of correlation coefficients.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.