Abstract

A Burkholderia gladioli strain, named BBB-01, was isolated from rice shoots based on the confrontation plate assay activity against several plant pathogenic fungi. The genome of this bacterial strain consists of two circular chromosomes and one plasmid with 8,201,484 base pairs in total. Pangenome analysis of 23 B. gladioli strains suggests that B. gladioli BBB-01 has the closest evolutionary relationship to B. gladioli pv. gladioli and B. gladioli pv. agaricicola. B. gladioli BBB-01 emitted dimethyl disulfide and 2,5-dimethylfuran when it was cultivated in lysogeny broth and potato dextrose broth, respectively. Dimethyl disulfide is a well-known pesticide, while the bioactivity of 2,5-dimethylfuran has not been reported. In this study, the inhibition activity of the vapor of these two compounds was examined against phytopathogenic fungi, including Magnaporthe oryzae, Gibberella fujikuroi, Sarocladium oryzae, Phellinus noxius and Colletotrichum fructicola, and human pathogen Candida albicans. In general, 2,5-dimethylfuran is more potent than dimethyl disulfide in suppressing the growth of the tested fungi, suggesting that 2,5-dimethylfuran is a potential fumigant to control plant fungal disease.

Keywords: Burkholderia gladioli; Magnaporthe oryzae; volatile organic compounds; dimethyl disulfide; 2,5-dimethylfuran; fumigant

1. Introduction

Over 2 million tons of chemical pesticides are used each year worldwide to enhance agriculture production, which otherwise would be reduced due to competitive exclusion by weeds or predation by various pests including insect herbivores, nematodes and pathogenic microorganisms [1]. Nonetheless, the heavy use of chemical pesticides has had negative impacts on both human health and environmental sustainability due to the lack of selective toxicity and their recalcitrant nature. Microbial antagonists may provide an alternative or a supplement to chemical pesticides for the protection of agricultural plants from pests through diverse mechanisms such as production of anti-pathogen substances and niche competition. Anti-pathogen substances produced by microorganisms could be liquid diffusible or volatile compounds. The former includes antibiotics, toxins, bio-surfactants, cell wall disruption enzymes, etc., while the latter are diverse chemical metabolites with low molecular mass, low boiling points, and high vapor pressures. Recently, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by microorganisms have gained increasing attention due to their importance in both basic science and the application potential in pest control [2,3].

Approximately 2000 VOCs, emitted from almost 1000 bacterial and fungal species, are archived in mVOC database 2.0 (http://bioinformatics.charite.de/mvoc/). They are categorized based on chemical structures and microbial emitters/receivers [4]. In view of chemical structures, microbial VOCs may belong to hydrocarbons, alcohols, ketones, ethers, esters, terpenes, heteroatom-containing compounds, and others. Microbial VOCs play diverse biological functions in the ecosystem; they may exert antagonistic or symbiotic effects among inter- and intra-kingdom species, modulate plant growth, and even condition plants to ward off pathogens. A couple of recent reviews are excellent reading sources to update the study progress in microbial VOCs [2,3].

Crops are constantly attacked by pathogenic fungi. For example, rice, a crucial food staple in Asia, is susceptible to many fungi. Infection of Magnaporthe oryzae, a causative agent of rice blast disease, may significantly devastate rice yields, causing from 20 to 30% losses each year [5,6]. Besides, Gibberella fujikuroi and Sarocladium oryzae are two other common pathogenic fungi of rice in Taiwan, which cause the bakanae disease [7] and the sheath rot disease [8], respectively. The long-term goal of this study is to seek potential biocontrol agents, by which the use of chemical pesticides in agriculture practice, particularly in the rice field, could be reduced in the future. Burkholderia gladioli, an aerobic gram-negative bacterium, often displays antagonistic interactions with other microbes in the environment. Here, we describe a B. gladioli strain, named strain BBB-01 hereafter, which was isolated from rice shoots. It exhibits a strong and broad antagonistic activity against many plant pathogenic fungi based on the confrontation plate assay. Moreover, B. gladioli BBB-01 emits a vast fraction of dimethyl disulfide or 2,5-dimethylfuran, depending on the culture condition. According to the mVOC database, dimethyl disulfide could be emitted by a broad spectrum of microorganisms, and it has been used as an active ingredient in commercial pesticides. By contrast, only a couple of fungi was reported to emit 2,5-dimethylfuran, without a notion about the compound’s bioactivity [9]. This report presents the antifungal activity of 2,5-dimethylfuran via fumigation for the first time. In addition, the efficacy of 2,5-dimethylfuran vapor in suppressing pathogenic fungi is compared with that of dimethyl disulfide.

2. Results

2.1. Bacteria Exhibiting Antifungal Activity

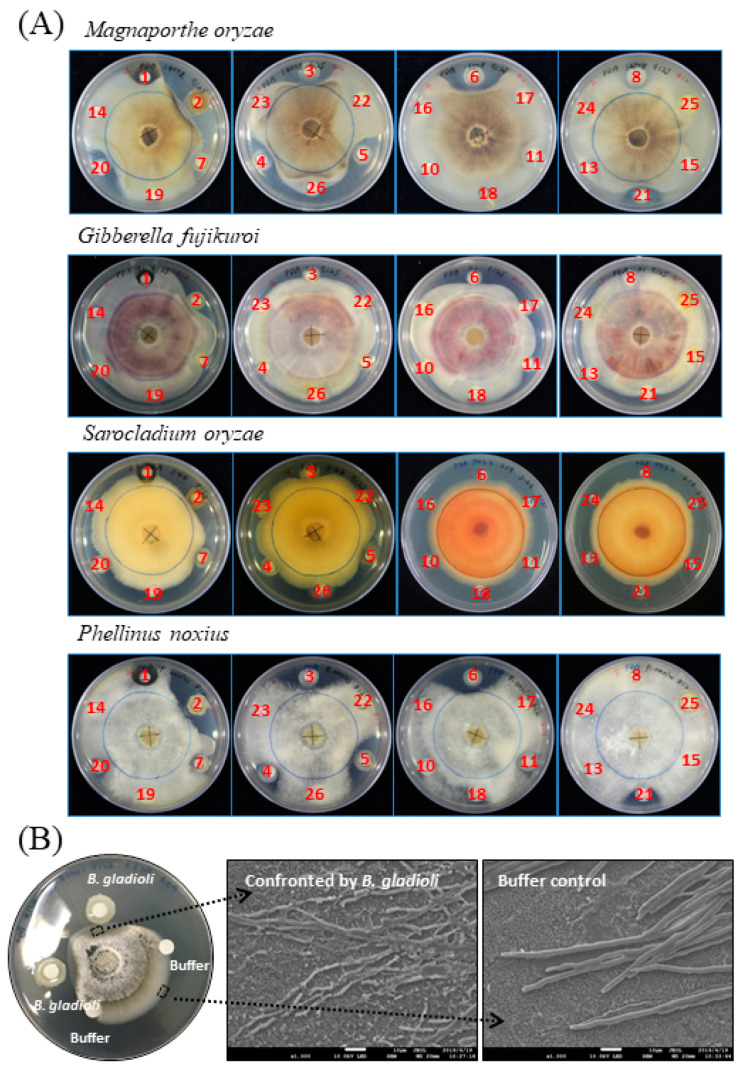

A previous collection of plant growth-promoting microorganisms, isolated from a variety of environmental sites/habitats, e.g., urban soils, farmland soils, plant leaves, and insect guts, was screened for antifungal activity by the standard plate confrontation assay in this study. The challenged pathogens used in the assay included M. oryzae, G. fujikuroi, S. oryzae and Phellinus noxius. The first three are pathogens of rice, while P. noxius infects a broad range of horticultural plants such as tea and fruit trees. The screen revealed that microbial isolates numbered #2, #3, #4, #5, #6, #20, and #21 exhibited significantly antagonistic effects on the growth of M. oryzae and P. noxius (Figure 1A). Among them, the isolate #2, i.e., Burkholderia gladioli BBB-01, was particularly noted due to its strong inhibition activity against all the four fungi.

Figure 1.

Confrontation assay between pathogenic fungi and screened microbial species. (A) The challenged fungus, as indicated, grew radially from the center of the plate, while the screened microbial species were placed outside and surround the mycelial colony as described in Section 4. The screened microbial species and the isolation site, in parentheses, are as follows: #1, Aureobasidium melanogenum (beehive); #2, Burkholderia gladioli (rice shoot); #3, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (spoiled food); #4, P. aeruginosa (spoiled food); #5, P. aeruginosa (mealworm); #6, P. aeruginosa (mealworm); #7, Dyella yeojuensis (urban soil); #8, Serratia marcescens (bamboo forest soil); #10, P. aeruginosa (rice field); #11, P. aeruginosa (rice field); #13, S. marcescens (rice field); #14, Aeromonas sp. (rice field); #15, S. marcescens (cigarette beetle); #16, S. marcescens (cigarette beetle); #17, S. marcescens (riverbank soil); #18, S. marcescens (riverbank soil); #19, Bacillus sp. (poultry feather); #20, Burkholderia cepacia (urban soil); #21, P. aeruginosa (urban soil); #22, S. marcescens (urban soil); #23, P. aeruginosa (urban soil); #24, Stenotrophomonas nitrireducens (used coffee grounds); #25, Sphingobium yanoikuyae (used coffee grounds). #26, Pseudomonas sp. (alkaline soil) (B) Morphology change of M. oryzae in response to the confrontation against B. gladioli BBB-01 was examined under a scanning electron microscope as described in Section 4. The mycelia within the dashed line-enclosed area were taken and observed. The scale bar in photos represents 10 µm.

To see whether the morphology of M. oryzae was changed upon confrontation by B. gladioli BBB-01, the mycelia at the front line facing the Burkholderia colony or the medium control was taken and observed under a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Figure 1B). The mycelia confronted by B. gladioli BBB-01 showed fragmented appearances, while that taken from the control region was intact. This morphology change clearly indicates that B. gladioli BBB-01 truly killed the fungus rather than slowed down the fungal growth.

2.2. Phylogenetic Relationship of B. gladioli BBB-01 with Its Kin

B. gladioli is present in diverse habitats and possibly associated with humans, animals and plants. Strains of this species could be a plant pathogen, a lung pathogen in cystic fibrosis patients, or a contaminant in fermented foods producing deadly bongkrekic acid. On the other hand, some strains of B. gladioli may benefit its eukaryotic hosts by providing protective secondary metabolites such as antibiotics and other bioactive substances. Given its importance in the biologically relevant context, to date, hundreds of B. gladioli strains have been isolated and the genomic information is accessible in public databases for many of them. Recently, a pangenomic analysis of 206 B. gladioli strains was performed, separating these strains into five evolutionary clads [10]. All the known bongkrekic acid-producing strains and those containing biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) for bongkrekic acid synthesis are in either clade 1A, 1B, or 1C. Strains of B. gladioli pv. allicola dominant clade 2, while B. gladioli pv. gladioli and B. gladioli pv. agaricicola dominant clade 3.

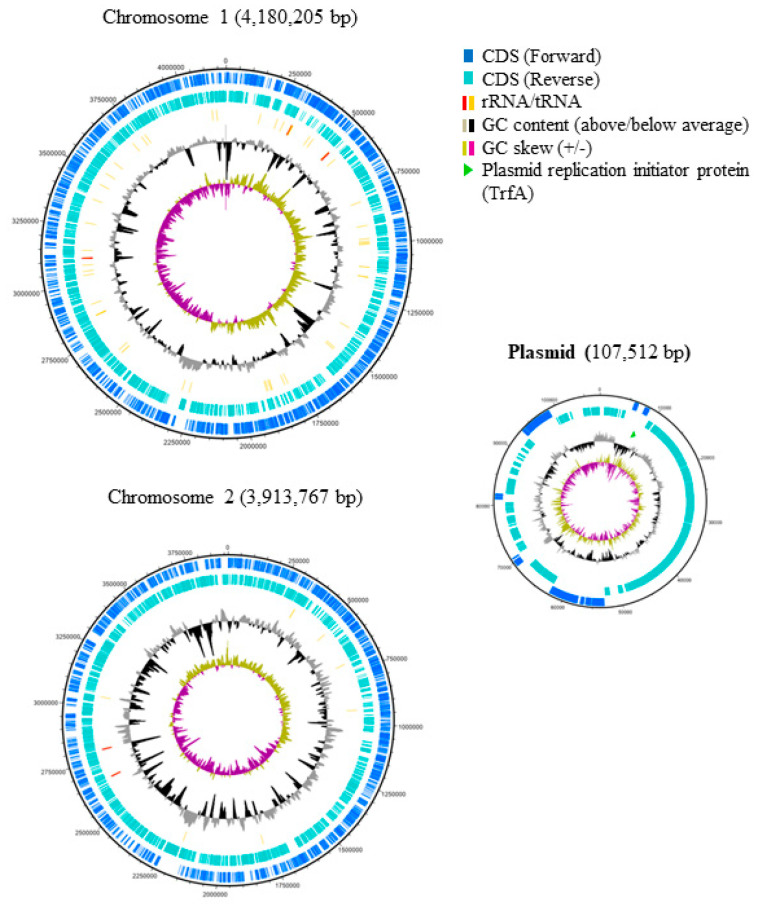

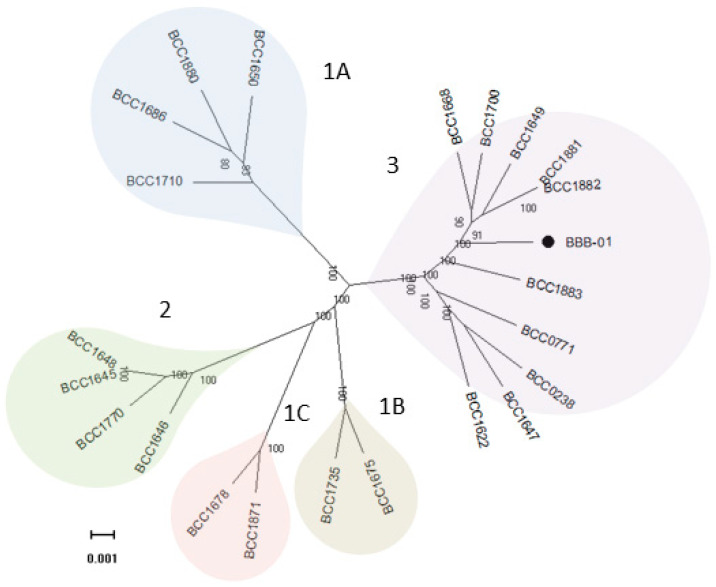

The genome of B. gladioli BBB-01 was sequenced using Illumina MiSeq System and Nanopore technology. The joining efforts resulted in two circular chromosomes with 4,180,205 and 3,913,767 bp, respectively, and one plasmid with 107,512 bp (Figure 2). The whole genome, 68.2% in GC content, contains 7665 protein- and 57 tRNA-coding genes. In this study, the phylogenetic relationship of B. gladioli BBB-01 with its kin was established. The sequencing reads of 22 other B. gladioli strains, selected from each clade of the previous classification by Jones et al. [10], were downloaded and individually de novo assembled. The strain name, accession number, and classification information of these 22 selected strains are listed in Table 1. Genome annotation and pangenome analysis were performed using the software Prokka (v1.14.5) [11] and Roary (v3.11.2) [12], respectively. The pangenome of these 23 B. gladioli strains consist of 15,046 genes, within which 4141 are core genes. The core genes were concatenated and used to conduct a multiple nucleotide sequence alignment. Accordingly, a maximum-likelihood tree was constructed using RAxML (v. 8.2.12) [13] in the GTR-GAMMA model with 1000 rapid bootstraps. This small-scale phylogeny has B. gladioli BBB-01 positioned in clade 3 (Figure 3), while the rest 22 strains were grouped identically as the previous classification [10]. Annotation of the pangenome in this study also indicates that only the B. gladioli strains belonging to the clade 1 contain BGCs analogous to BGC0000173 in MIBiG database, which denotes the production potential of bongkrekic acid. Therefore, B. gladioli BBB-01 is not, theoretically, a bongkrekic acid-producing strain.

Figure 2.

Genome maps of B. gladioli BBB-01. The nucleotide sequence of the genome was determined as described in Section 4. The genetic features were labeled from the outer to the inner rings of the maps. The 1st and 2nd rings indicate the protein-coding sequences (CDS) encoded in the forward and reverse strands of genome, respectively. The 3rd ring indicates the genes of rRNA and tRNA with red and yellow sticks, respectively. The 4th ring indicates GC content. Those being above and below the average are shown by grey and black curves, respectively. The 5th ring indicates GC skew. The positive and negative skew are shown by the light gold and purple curves, respectively. The light green arrowhead in the plasmid map indicates the replication initiator protein.

Table 1.

Burkholderia gladioli isolates selected in the pangenome analysis in this study.

| Clade | Strain Name | Accession Number 1 | Synonym | Bongkrekic Acid Production |

Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | BCC1710 | ERS785039 | + | CF isolate 2 | |

| BCC1650 | ERS784828 | ENV; B. gladioli pv cocovenenans, LMG 11626, Indonesia | + | ||

| BCC1880 | ERS1371628 | ENV; B. gladioli pv cocovenenans, LMG 18113, China | + | ||

| BCC1686 | ERS784816 | + | CF isolate | ||

| 1B | BCC1675 | ERS785062 | + | CF isolate | |

| BCC1735 | ERS785008 | + | CF isolate | ||

| 1C | BCC1678 | ERS784880 | + | CF isolate | |

| BCC1871 | ERS1371626 | CF isolate | |||

| 2 | BCC1645 | ERS784911 | ENV; B. gladioli pv. alliicola, LMG 6954, Australia |

||

| BCC1648 | ERS784957 | ENV; B. gladioli pv. alliicola, LMG 2121, USA |

|||

| BCC1770 | ERS1328772 | CF isolate | |||

| BCC1646 | ERS784928 | ENV; B. gladioli pv. alliicola, LMG 6878, India |

|||

| 3 | BCC1622 | ERS784864 | CF isolate | ||

| BCC1647 | ERS784943 | B. gladioli pv. gladioli, LMG 6882, USA | |||

| BCC0238 | ERS784907 | CF isolate | |||

| BCC0771 | ERS784806 | B. gladioli pv. gladioli, LMG 2216 (ATCC 10248), USA | |||

| BCC1668 | ERS784974 | CF isolate | |||

| BCC1700 | ERS784851 | CF isolate | |||

| BCC1649 | ERS784812 | ENV; B. gladioli pv. gladioli, LMG 6880t4, Zimbabwe | |||

| BCC1881 | ERS1371629 | ENV; B. gladioli pv. agaricicola, NCPPB 3580, UK | |||

| BCC1882 | ERS1371630 | ENV; B. gladioli pv. agaricicola, NCPPB 3632, UK | |||

| BCC1883 | ERS1371630 | ENV; B. gladioli pv. agaricicola, NCPPB 3852, New Zealand | |||

| BBB-01 | B. gladioli BBB-01 | Isolated in this study |

1 The genome is accessible at website https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/home. 2 Isolates from cystic fibrosis patients.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationship of 23 B. gladioli strains. The genomes of 22 previously reported B. gladioli strains and the strain isolated in this study (BBB-01) were analyzed and compared on the genome scale, from which 4141 core genes were identified. The concatenated core genes were aligned and used to construct a maximum-likelihood tree with 1000 rapid bootstraps. All the bioinformatics tools used in the construction of this phylogeny are described in Section 4. The scale bar represents the number of base substitutions per site.

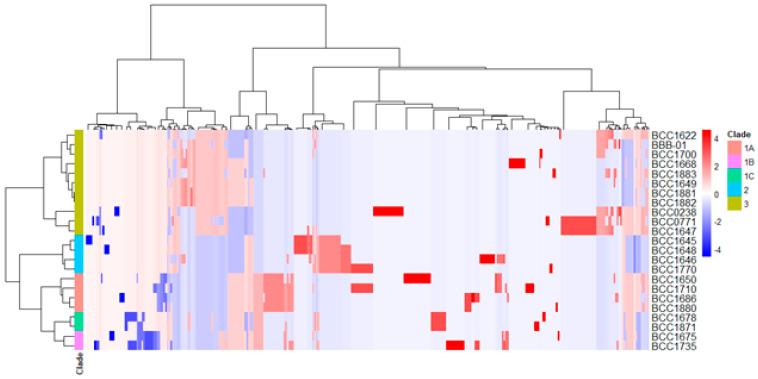

Besides bongkrekic acid, B. gladioli strains could produce a variety of secondary metabolites according to the relevant genes classified in the COG category Q (Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism). Specifically, there are 223 genes belonging to the category Q in B. gladioli BBB-01 and 458 genes in the pangenome of these 23 B. gladioli strains. Thus, distribution of each of the genes in the pangenome was analyzed by heatmap clustering. The resulting dendrogram reveals several hierarchical clusters depicted on the top of Figure 4. The dendrogram also indicates that the variation in the genetic contents involved in secondary metabolite synthesis, transport, and catabolism is more or less consistent with the clade classification in the core gene-based phylogeny.

Figure 4.

Heatmap clustering for the distribution of genes involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis in Burkholderia gladioli strains. The 458 genes, which are involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis (COG category Q) in the pangenome of 23 B. gladioli strains, were analyzed by heatmap clustering using the integrated tool (pheatmap) in the R program. The number of each gene among the 23 B. gladioli strains was normalized, followed by construction of distance matrix using the Manhattan method and hierarchical clustering using the Ward’s minimum variance (ward.D) method. The clade classification based on core genes is shown vertically, while the clustering of the 458 genes is shown horizontally.

2.3. B. gladioli BBB-01 Being Capable of Producing Antifungal Vapor

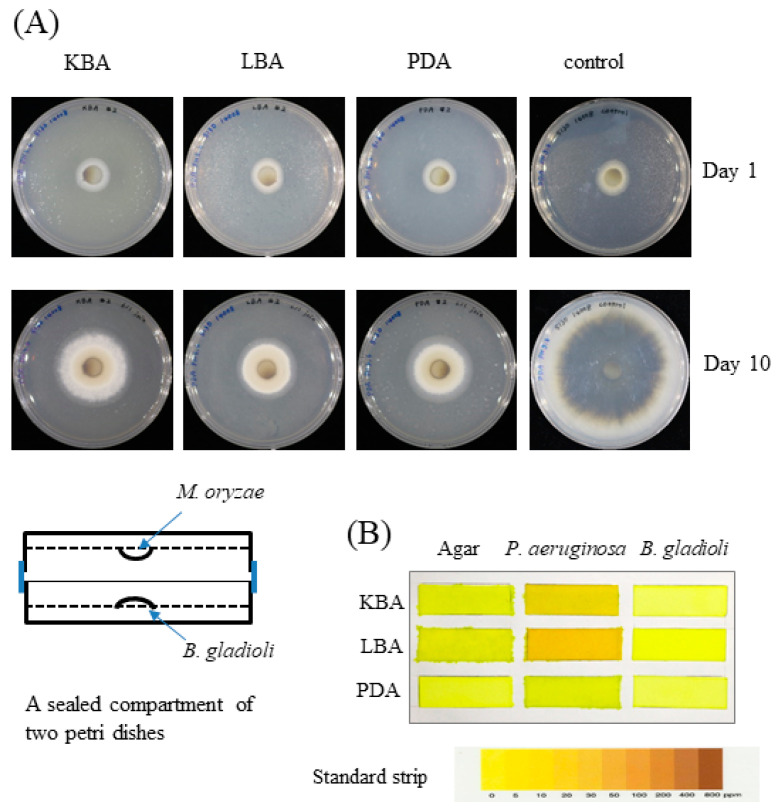

The confrontation plate assay showed antifungal activity of B. gladioli BBB-01 through direct interaction (Figure 1). It was interesting to know whether B. gladioli BBB-01 emits volatile compounds to suppress the fungal growth as well. The question was answered by conducting a simple test using a sealed compartment of two Petri dishes, in which the downward plate contained M. oryzae grown on PDA and the upward plate contained the bacterium grown on PDA, LBA, or KBA. The growth of M. oryzae was examined after a 10-day incubation at 28 °C. In comparison with the control, B. gladioli BBB-01 exhibited a culture medium-dependent inhibition on M. oryzae, with the stronger effect seen on LBA and PDA than on KBA (Figure 5A), suggesting a role of volatile compounds in suppressing the growth of M. oryzae. Some Pseudomonas species could synthesize hydrogen cyanide, a potent inhibitor of cytochrome c oxidase, under microaerobic conditions (O2 < 5%) for a better niche competition [14]. The emission of hydrogen cyanide by B. gladioli BBB-01 was examined by placing a carbonate-picrate paper strip in the headspace of sealed culture plates (Figure 5B). As expected, a P. aeruginosa strain, #6 isolate in this study, could produce hydrogen cyanide when it grew on LBA and KBA. By contrast, B. gladioli BBB-01 did not emit hydrogen cyanide under the culture condition.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of M. oryzae by B. gladioli BBB-01 via fumigation. (A) M. oryzae and B. gladioli BBB-01 were cultivated separately on two agar plates within a sealed compartment as illustrated. M. oryzae was grown on PDA, while B. gladioli BBB-01 was grown on KBA, LBA, or PDA as indicated. The growth of M. oryzae alone was taken as the control. The radial colony of M. oryzae on days 0 and 10 after fumigation was shown. (B) P. aeruginosa and B. gladioli BBB-01 were cultivated on KBA, LBA, or PDA. A paper strip soaked with picric acid and sodium carbonate was stuck on the lid within the sealed petri dish. The appearance of brown color of the paper indicates the presence of hydrogen cyanide as indicated by the standard strip.

2.4. Chemical Identification of VOCs Produced by B. gladioli BBB-01

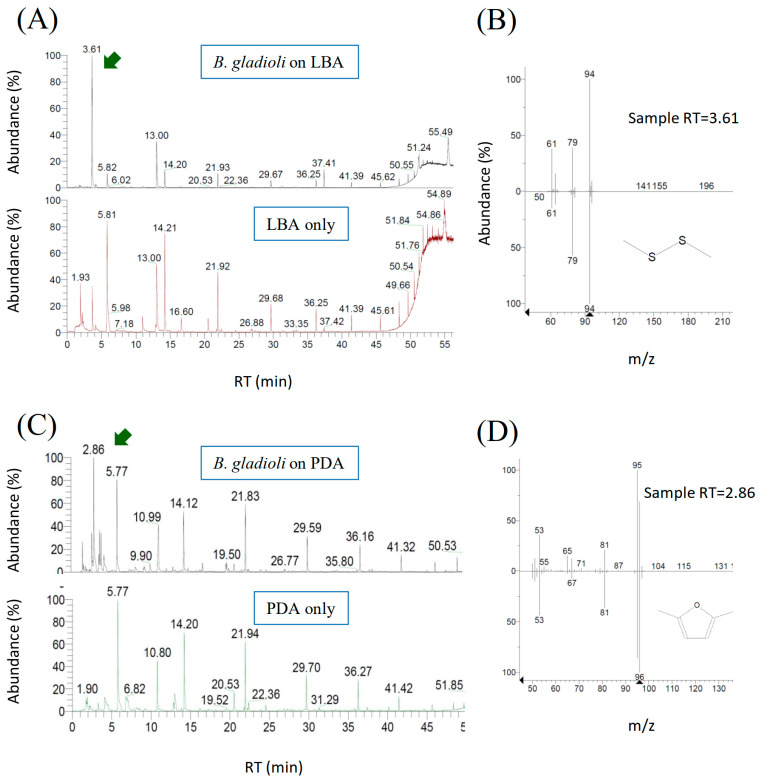

Although VOCs released by a wide range of microorganisms have been documented in a large body of literature [15,16,17,18], few information is available for B. gladioli. In this study, VOCs produced by B. gladioli BBB-01 were collected by the SPME fiber and analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). A peak with a retention time of 3.61 min in the GC chromatogram appeared in the sample collected from B. gladioli BBB-01 grown on LBA but not from blank LBA (Figure 6A). The chemical entity of the peak was further analyzed by mass spectrometry, and dimethyl disulfide was suggested based on the NIST reference database with a similarity of 95% (Figure 6B). On the other hand, a peak with a retention time of 2.86 min appeared in the collected sample if B. gladioli BBB-01 was cultivated on PDA (Figure 6C). The fragmentation pattern in the mass spectrum suggests that the compound is 2,5-dimethylfuran with a similarity of 97% (Figure 6D). The purchased dimethyl disulfide and 2,5-dimethylfuran were subjected to the GC analysis as the standards to confirm the identities of the volatile compounds emitted by B. gladioli BBB-01. Either of the standards had a nearly identical retention time, <2%, to the respective value described above.

Figure 6.

Chemical identification of VOCs emitted by B. gladioli BBB-01. VOCs collected from the headspace of the bacterial culture flask by the SPME fiber was analyzed by GC (A,C). The peaks of a retention time (RT) of 3.61 and 2.86 min appeared only when the Burkholderia strain was grown on LBA and PDA, respectively. The two unique peaks were further analyzed by mass spectrometry, and the fragmentation patterns match that of dimethyl disulfide (B) and 2,5-dimethylfuran (D), respectively, according to the NIST database.

2.5. Antifungal Activity of 2,5-Dimethylfuran and Dimethyl Disulfide via Fumigation

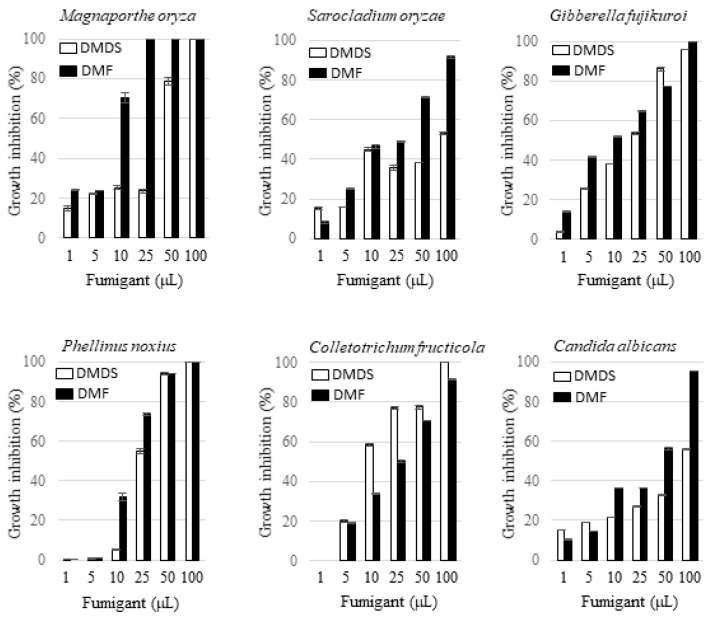

Dimethyl disulfide is a volatile compound emitted by phylogenetically diverse bacteria and fungi. Thanks to its pest control activity, this chemical has been used as an active ingredient in commercial fumigants, e.g., Paladin®. By contrast, to the best of our knowledge, 2,5-dimethylfuran produced by bacteria has not been reported in the literature. In this study, the activity of the vapor of 2,5-dimethylfuran and dimethyl disulfide against the growth of fungi was tested and the effects were compared with each other. The fungi tested include five plant pathogens including M. oryza, G. fujikuroi, S. oryzae, P. noxius, Colletotrichum fructicola, and one human pathogen, i.e., Candida albicans. The amounts of 2,5-dimethylfuran or dimethyl disulfide applied in a 125 mL Erlenmeyer flask were 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 µL. The radial inhibition percentage of the tested fungi by the two volatile compounds at each dosage is indicated in Figure 7. Both 2,5-dimethylfuran and dimethyl disulfide exhibited a dosage-dependent inhibition effect on all the tested fungi. In general, 2,5-dimethylfuran exhibited a more potent inhibition effect than dimethyl disulfide except in the case against C. fructicola. The vulnerability of the fungi under fumigation by 2,5-dimethylfuran was in the order of M. oryza > P. noxius > G. fujikuroi > C. fructicola > S. oryzae > C. albicans, and that by dimethyl disulfide was in the order of C. fructicola > G. fujikuroi > P. noxius > M. oryza > S. oryzae > C. albicans. The morphology of the suppressed M. oryza under sub-lethal concentrations of 2,5-dimethylfuran was also observed by scanning electron microscopy. Different from the observation of fragmented mycelia in confrontation plate, the look of the suppressed fungus was not changed apparently.

Figure 7.

Antifungal activity of 2,5-dimethylfuran and dimethyl disulfide via fumigation. The fungus was cultivated on PDA or YPD in a tightly closed 125 mL Erlenmeyer flask, in which 2,5-dimethylfuran (DMF) or dimethyl disulfide (DMDS) at the indicated aliquot was included as described in Section 4. Cultivation was continued until the fungal colony in the fumigant-absent control group was fully grown. The effect of the fumigant on growth of the fungus was recorded, and the radial inhibition percentages (%) was calculated as described in Section 4. All data points are the means of three replicates.

3. Discussion

Numerous beneficial bacteria, particularly in the genus Bacillus and Pseudomonas, have been reported to suppress the growth of plant pathogens, including bacteria, fungi, and nematodes, through antagonistic behavior. Recently, the genus Burkholderia is recognized also as a rich source for potential biocontrol agents in agriculture. [19]. Taking strains in the species B. gladioli as examples, B. gladioli B111 inhibited the occurrence of lily gray mold Botrytis ellipticaon [20], a B. gladioli pv. agaricicola strain controlled a wide range of fungi including Botrytis cinerea, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Penicillium digitatum, Penicillium expansum, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, and Phytophthora cactorum [21], B. gladioli 3A12 suppressed Sclerotinia homoeocarpa [22], and B. gladioli NGJ1 inhibited Rhizoctonia solani via a rather unusual mycophagous behavior [23]. In this study, we demonstrated that B. gladioli BBB-01 could inhibit the growth of a variety of pathogenic fungi through releasing water-diffusible substances and emitting volatile compounds.

Several dozens of VOCs emitted by the genus Burkholderia have been identified. B. gladioli pv. agaricicola strain ICMP 11096 was able to produce d-limonene [21]. B. ambifaria emitted a blend of volatile compounds, which not only inhibited the growth of Rhizoctonia solani and Alternaria alternate but also induced significant biomass increase in Arabidopsis thaliana [24]. The B. ambifaria-emitted volatiles consisted of about 40 compounds, among which dimethyl disulfide was the most abundant. Paraburkholderia tropica, formerly known as B. tropica, emitted rich VOCs including acetic acid, methyl hexadecanoate, dimethyl disulfide, isobutyl ether, toluene, p-xylene, 5-cyano-1,2,3-thiadiazole, tetrachloroethyene, tricosene, 3-methoxybutyl-1-ene, methylcyclohexane, nonane, ethylbenzene, ethyl valerate, ocimene, α-pinene, d-limonene, and l-fenchone [25]. In this study, we found that B. gladioli BBB-01 could emit 2,5-dimethylfuran and dimethyl disulfide. Both are potent in growth suppression of M. oryza, G. fujikuroi, S. oryzae, P. noxius, C. fructicola, and C. albicans via fumigation. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing the emission of 2,5-dimethylfuran by a bacterial strain and demonstrating the efficacy of 2,5-dimethylfuran vapor in suppressing the growth of pathogenic fungi. From the application perspective, the finding in this study provides another alternative to control plant fungal disease by using 2,5-dimethylfuran as a fumigant.

The emitters of dimethyl disulfide include a wide range of fungi and bacteria. l-methionine γ-lyase is the conserved key enzyme for biosynthesis of dimethyl disulfide [26]. In fact, the coding gene of the lyase (mdeA) is located on the chromosome 2 of B. gladioli BBB-01. By contrast, the known emitters of 2,5-dimethylfuran is limited to a couple of fungi such as Penicillium commune and Paecilomyces variotii [9]. However, how 2,5-dimethylfuran is synthesized by microorganisms is still unknown. Through emitting 2,5-dimethylfuran, B. gladioli BBB-01 may gain an additional advantage over its rivals in the habitats. Microbial production of hydrogen cyanide relies on the hcnABC gene cluster [27]. Although B. gladioli BBB-01 contains hcnABC on the chromosome 2, this study failed to find evidence to support hydrogen cyanide production. Presumably, certain culture conditions, e.g., strictly controlled microaerobic environment, are required for B. gladioli BBB-01 to emit hydrogen cyanide.

Liquid diffusible substances such as antibiotics and fungal cell wall-hydrolytic enzymes might also play a role in the antagonistic activity of B. gladioli BBB-01 based on the results of confrontation plate assay (Figure 1A). Searching the genome of B. gladioli BBB-01 using the MIBiG database by antiSMASH discovered nine BGCs potentially able to direct the synthesis of pesticidal compounds. Of them, a BGC located on chromosome 1 shows 30% sequence similarity to BGC0000398, which is responsible for the production of cyclic lipopeptide orfamide B. This lipopeptide is a biosurfactant with fungicidal and insecticidal activity [28,29,30,31]. Therefore, B. gladioli BBB-01 may produce an orfamide analog to suppress the pathogenic fungi. Besides, there are two chitinase homologous genes in chromosome 2 of B. gladioli BBB-01. The secreted chitinase may damage the fungal cell wall, leading to fragmentation of the confronted mycelia. Nonetheless, the actual effective compounds released by B. gladioli BBB-01 in agar plate remain to be identified.

B. gladioli BBB-01 was isolated from rice shoot. Spraying B. gladioli BBB-01 on rice did not cause observable harm to the plant. The confrontation assay in this study showed an antagonistic activity of this bacterial strain against M. oryzae, G. fujikuroi, and S. oryzae, three common pathogenic fungi of rice in Taiwan. In addition, both dimethyl disulfide and 2,5-dimethylfuran have the power to control the growth of a variety of fungi. Thus, the potential of B. gladioli BBB-01 in protection of rice from infestation by pathogenic fungi in planta shall be assessed in the future. Queries such as how the fungal cells are suppressed by 2,5-dimethylfuran and what genes are involved in the biosynthesis of 2,5-dimethylfuran in B. gladioli BBB-01 are important issues that deserve further investigation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Media and Chemicals

Potato infusion powder, peptone, tryptone, and yeast extract were purchased from DifcoTM (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Dimethyl disulfide was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA), while 2,5-dimethylfuran was purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). Other general chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

4.2. The Screen of Antifungal Bacteria

The fungus as indicated was cultivated on a PDA plate (0.4% potato infusion powder, 2% glucose, 1.5% agar) at 28 °C for 4 days. A 1-cm-diameter agar plug, full of mycelium, was cut out from the 4-day-cultured fungal colony and positioned onto the center of another plate of PDA, KBA (2% peptone, 0.15% K2HPO4, 0.15% MgSO4·7H2O, 1.5% glycerol, 1.5% agar, pH 7.2) or LBA (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl, 1.5% agar). The fungus was cultivated continuously until the diameter of the radial colony reached about 6 cm in diameter. Subsequently, a 200-µL aliquot of the overnight culture of screened microorganisms was dropped onto a 0.6-cm-diameter filter paper, placed at a distance of 0.5 cm to the periphery of the fungal colony. The plate was incubated continuously at 28 °C, and the growth of the pathogenic fungus confronted by screened microorganisms was recorded daily. The incubator used in this study was made by Yih Der Technology Co., (New Taipei City, Taiwan).

4.3. Pangenomic Analysis of B. gladioli Isolates

In this study, the whole genome of B. gladioli BBB-01 was sequenced by performing 2 × 301 bp paired-end sequencing using Illumina MiSeq System (San Diego, CA, USA), followed by long-read sequencing using Nanopore technology (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK). The complete circular chromosomes of BBB-01 were displayed using DNAplotter [32]. The nucleotide sequences of the chromosomes and plasmid are available in Genbank with accession number CP068049, CP068050, and CP068051, respectively. A genome mining for biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) that are responsible for the production of various secondary metabolites was conducted using antiSMASH version 5.2.0 [33]. For the kinship analysis of B. gladioli BBB-01, the sequencing reads of other 22 B. gladioli isolates, representing different clades of B. gladioli in the phylogenetic tree described by Jones et al. [10], were collected from the database (Table 1). The sequencing reads of each strain were individually de novo assembled using Unicycler (v0.4.8) [34]. The bacterial genomes were annotated by Prokka (v1.14.5) [11], followed by pangenome analysis using Roary (v3.11.2) [12]. Each gene in pangenome was assigned to Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COGs) using the Perl script cdd2cog.pl [35], and the distribution of genetic contents in pangenome was analyzed by heatmap clustering using the integrated tools in R software (version 4.0.2). The core genes in the pangenome were concatenated for multiple nucleotide sequence alignment using MAFFT (v. 7.455) [36]. Accordingly, a maximum-likelihood tree was constructed using RAxML (v. 8.2.12) in the GTR-GAMMA model with 1000 rapid bootstraps [12]. The phylogenetic tree was displayed using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software (MAGA X) [37].

4.4. Assay of Bacterial Antifungal VOCs

A 100-µL aliquot of the overnight culture of B. gladioli BBB-01 was spread out on a PDA, LBA, or KBA plate, followed by incubation at 28 °C for 24 h. Meanwhile, M. oryzae was cultivated on a separate PDA plate until the colony size reached about 2 cm in diameter. The two agar plates, one with B. gladioli BBB-01 and the other with M. oryzae, were aligned face-to-face and sealed with parafilm. The sealed dish unit was incubated at 28 °C, and the growth of M. oryzae was recorded daily. In the control experiment, the plate of M. oryzae was sealed with a blank medium plate.

4.5. Assay of Bacterium-Emitted Hydrogen Cyanide

A 100-µL aliquot of overnight bacterial culture was spread out on the plate of PDA, LBA, or KBA, followed by incubation at 28 °C for 24 h. A cellulose strip (3 cm × 1 cm) (Whatman®, Kent, UK) that had been soaked in a solution of 0.5% picric acid and 2% sodium carbonate was stuck on the interior surface of the lid of the plate. The bacterium in the parafilm-sealed plate was grown continuously at 28 °C, in dark, for 4 days. A color change in the cellulose paper from yellow to reddish-brown indicates the presence of hydrogen cyanide.

4.6. Chemical Identification of Bacterial VOCs by GC-MS

A 100-µL aliquot of overnight bacterial culture was spread out on 5 mL PDA or LBA in a 125 mL Erlenmeyer flask. The flask mouth was sealed with several layers of parafilm and incubated at 28 °C for 3 days. Then, a solid-phase microextraction (SPME) needle (75 μm Car/PDMS, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) was used to pierce through the parafilm, and the needle was held for 20 min to adsorb the VOCs accumulated in the headspace of the flask. Adsorbed VOCs were analyzed by GC-MS using the TRACE GC PolarisQ mass system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The operation of GC was carried out using a DB-5ms column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 025 film thickness) (Agilent J & W Scientific, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a helium flow at 1 mL/min under the temperature program: 240 °C, 10 sec (desorption); 40 °C, 5 min; 40 → 120 °C at the accelerating rate of 3 °C/min; 120 → 180 °C at 4 °C/min; 180 → 280 °C at 20 °C/min; and 280 °C, 5 min. The compound representing each of the chromatographic peaks was then analyzed by MS. The chemical structure of the compound was proposed based on the fragmentation pattern against the database in the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) by using the NIST 08 MS Library and MS Search Program v.2.0f.

4.7. Antifungal Activity Assay of Chemically Synthesized Fumigants

The vulnerability of 5 plant pathogens (M. oryza, G. fujikuroi, S. oryzae, P. noxius, and Colletotrichum fructicola) and 1 human pathogen (Candida albicans) under the fumigation were tested in this study. To plant pathogens, a 0.6-cm-diameter agar plug, full of the tested fungal mycelium, was positioned on the center of PDA molded in a 125-mL Erlenmeyer flask. To C. albicans, 5 µL overnight culture was deposited on the center of YPD agar (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose, and 1.5% agar). The flask was placed upside down and an aliquot of 2,5-dimethylfuran or dimethyl disulfide as indicated was dropped onto a small cotton ball attached to the interior side of the screw cap of the flask. The cap was closed tightly, and the fungus inside was grown continuously for 1–2 weeks. The effect of the fumigant on growth of the fungus was recorded, and the radial inhibition percentages (%) was calculated as [(Rc − Ri)/Rc] × 100, in which Rc is the value of the fungal growth radius in the absence of fumigant and Ri represents the growth radius in the presence of fumigant. The data presented are the mean of three replicates.

4.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

M. oryzae was inoculated onto the center of a PDA plate until it grew up to a colony of 3 cm in diameter. A 200-µL aliquot of the overnight culture of B. gladioli BBB-01 or culture medium (the control) was added onto the PDA plate in a distance of 0.5 cm to the circumference of the mycelial colony, followed by incubation at 28 °C for 3 more days. A thin agar section was sliced off from the front line of the mycelial colony that directly confronted the Burkholderia strain or the control medium. The agar sample for scanning electron microscopy was prepared according to the instruction of the Cryo-SEM Preparation System (PP3010T, Quorum Technologies, Laughton, UK) and observed under the thermal fieldscanning electron microscope (JEOL, JSM-7800F, Tokyo, Japan).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to show their gratitude to Chi-Yu Chen, Miin-Huey Lee, and Chih-Li Wang at the Department of Plant Pathology, National Chung Hsing University, for their generosity in providing rice fungal pathogens (M. oryza, G. fujikuroi, and S. oryzae), wax apple fungal pathogen (C. fructicola), and P. noxius, respectively. We also appreciate the technical assistance by David Sheng-Yang Wang and Nai-Wen Tsao at the Department of Forest, National Chung Hsing University, for the operation of GC-MS.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.-T.L., C.-C.L.; investigation, Y.-T.L., C.-C.L., Y.-C.H.; data curation, W.-M.L.; writing and editing, W.-M.L., M.M.; formal analysis, J.-J.W.; conceptualization, M.M.; funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, ROC, under the grant number 106-2313-B-005-021-MY3.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.De A., Bose R., Kumar A., Mozumdar S. Targeted Delivery of Pesticides Using Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticles. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2014. Worldwide pesticide use; pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz-Bohm K., Martín-Sánchez L., Garbeva P. Microbial volatiles: Small molecules with an important role in intra- and inter-kingdom interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:2484. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tilocca B., Cao A., Migheli Q. Scent of a killer: Microbial volatilome and its role in the biological control of plant pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:41. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemfack M.C., Gohlke B.O., Toguem S.M.T., Preissner S., Piechulla B., Preissner R. mVOC 2.0: A database of microbial volatiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1261–D1265. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prabhu A.S., Filippi M.C., Silva G.B., Lobo V.L.S., Moraes O.P. An unprecedented outbreak of rice blast on a newly released cultivar BRS Colosso in Brazil. In: Wang G.L., Valente B., editors. Advances in Genetics, Genomics and Control of Rice Blast Disease. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2009. pp. 257–266. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nalley L., Tsiboe F., Durand-Morat A., Shew A., Thoma G. Economic and environmental impact of rice blast pathogen (Magnaporthe oryzae) alleviation in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0167295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakanae-IRRI Rice Knowledge Bank. [(accessed on 31 January 2021)]; Available online: www.knowledgebank.irri.org/index.php?option=com_zoo&task=item&item_id=924&Itemid=739.

- 8.Ghosh M.K., Amudha R., Jayachandran S., Sakthivel N. Detection and quantification of phytotoxic metabolites of Sarocladium oryzae in sheath rot-infected grains of rice. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2002;34:398–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.2002.01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunesson A., Vaes W., Nilsson C., Blomquist G., Andersson B., Carlson R. Identification of volatile metabolites from five fungal species cultivated on two media. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995;61:2911–2918. doi: 10.1128/AEM.61.8.2911-2918.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones C., Webster G., Mullins A.J., Jenner M., Bull M.J., Dashti Y., Spilker T., Parkhill J., Connor T.R., LiPuma J.J., et al. Kill and cure: Genomic phylogeny and bioactivity of a diverse collection of Burkholderia gladioli bacteria capable of pathogenic and beneficial lifestyles. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.09.033878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page A.J., Cummins C.A., Hunt M., Wong V.K., Reuter S., Holden M.T., Fookes M., Falush D., Keane J.A., Parkhill J.R. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blumer C., Haas D. Mechanism, regulation, and ecological role of bacterial cyanide biosynthesis. Arch. Microbiol. 2000;173:170–177. doi: 10.1007/s002039900127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filipiak W., Sponring A., Bauer M., Filipiak A., Ager C., Wiesenhofer H., Nagl M., Troppmair J., Amann A. Molecular analysis of volatile metabolites released specifically by Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bos L.D., Sterk P.J., Schultz M.J. Volatile metabolites of pathogens: A systematic review. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003311. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carroll W., Lenney W., Wang T., Spanel P., Alcock A., Smith D. Detection of volatile compounds emitted by Pseudomonas aeruginosa using selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2005;39:452–456. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labows J.N., McGinley K.J., Webster G.F., Leyden J.J. Headspace analysis of volatile metabolites of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and related species by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1980;12:521–526. doi: 10.1128/JCM.12.4.521-526.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eberl L., Vandamme P. Members of the genus Burkholderia: Good and bad guys. F1000Research. 2016;5:F1000 Faculty Rev-1007. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8221.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiou A.L., Wu W.S. Isolation, identification and evaluation of bacterial antagonists against Botrytis ellipticaon on lily. J. Phytopathol. 2001;149:319–324. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0434.2001.00627.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elshafie H.S., Camele I., Racioppi R., Scrano L., Iacobellis N.S., Bufo S.A. In vitro antifungal activity of Burkholderia gladioli pv. agaricicola against some phytopathogenic fungi. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012;13:16291–16302. doi: 10.3390/ijms131216291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shehata H.R., Lyons E.M., Jordan K.S., Raizada M.N. Bacterial endophytes from wild and ancient maize are able to suppress the fungal pathogen Sclerotinia homoeocarpa. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016;120:756–769. doi: 10.1111/jam.13050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swain D.M., Yadav S.K., Tyagi I., Kumar R., Kumar R., Ghosh S., Das J., Jha G. A prophage tail-like protein is deployed by Burkholderia bacteria to feed on fungi. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:404. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00529-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groenhagen U., Baumgartner R., Bailly A., Gardiner A., Eberl L., Schulz S., Weisskopf L. Production of bioactive volatiles by different Burkholderia ambifaria strains. J. Chem. Ecol. 2013;39:892–906. doi: 10.1007/s10886-013-0315-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tenorio-Salgado S., Tinoco R., Vazquez-Duhalt R., Caballero-Mellado J., Perez-Rueda E. Identification of volatile compounds produced by the bacterium Burkholderia tropica that inhibit the growth of fungal pathogens. Bioengineered. 2013;4:236–243. doi: 10.4161/bioe.23808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amarita F., Yvon M., Nardi M., Chambellon E., Delettre J., Bonnarme P. Identification and functional analysis of the gene encoding methionine-γ-lyase in Brevibacterium linens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:7348–7354. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7348-7354.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laville J., Blumer C., von Schroetter C., Gaia V., Défago G., Keel C., Haas D. Characterization of the hcnABC gene cluster encoding hydrogen cyanide synthase and anaerobic regulation by ANR in the strictly aerobic biocontrol agent Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:3187–3196. doi: 10.1128/JB.180.12.3187-3196.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gross H., Stockwell V.O., Henkels M.D., Nowak-Thompson B., Loper J.E., Gerwick W.H. The genomisotopic approach: A systematic method to isolate products of orphan biosynthetic gene clusters. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang J.Y., Yang S.Y., Kim Y.C., Lee C.W., Park M.S., Kim J.C., Kim I.S. Identification of orfamide A as an insecticidal metabolite produced by Pseudomonas protegens F6. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:6786–6791. doi: 10.1021/jf401218w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Z., Geudens N., Kieu N.P., Sinnaeve D., Ongena M., Martins J.C., Höfte M. Biosynthesis, chemical structure, and structure-activity relationship of orfamide lipopeptides produced by Pseudomonas protegens and related species. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:382. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olorunleke F.E., Hua G.K.H., Kieu N.P., Ma Z., Höfte M. Interplay between orfamides, sessilins and phenazines in the control of Rhizoctonia diseases by Pseudomonas sp.CMR12a. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2015;7:774–781. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carver T., Thomson N., Bleasby A., Berriman M., Parkhill J. DNAPlotter: Circular and linear interactive genome visualization. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:119–120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blin K., Shaw S., Steinke K., Villebro R., Ziemert N., Lee S.-Y., Medema M.H., Weber T. AntiSMASH 5.0: Updates to the secondary metabolite genome mining pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W81–W87. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wick R.R., Judd L.M., Gorrie C.L., Holt K.E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017;13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leimbach A. Bac-Genomics-Scripts: Bovine E. coli Mastitis Comparative Genomics Edition. [(accessed on 31 January 2021)];2016 Available online: zenodo.org/record/215824#.YBZ4_-hKg2w.

- 36.Katoh K., Misawa K., Kuma K.-I., Miyata T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.