Introduction

Crises can exacerbate existing inequalities. The climate change crisis affects the environment, health and wellbeing of low-income nations (Venn, 2019). War and refugee crises force displacement of millions, over half of whom are children (UN, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic is deepening social and economic inequalities (Jamal & Higham, 2021), particularly in the developing world. Scholars even question the fairness of instituting measures such as social distancing for socially and politically marginalised or disadvantaged groups, such as migrant workers, people experiencing homelessness and individuals of lower socio-economic status (Silva & Smith, 2020). Lockdown in many of these countries has put millions of tourism, hospitality and gig workers out of work, facing financial hardship, debt and poverty. In countries with less capacity to alleviate the impacts of the pandemic, the tourism workforce is now more vulnerable than ever. Tourism has been at the forefront of attention during the crisis because tourism and its affiliated industries are playing significant roles in the economies of many developing nations. These ‘tourism-dependent communities’ have now become ‘communities in crisis’ (Nepal, 2020). The livelihoods and social wellbeing of many in such communities are now threatened.

Clearly, the COVID-19 pandemic is more than a global health crisis to address; it is a justice issue following years of unsustainable growth, growing conflict, inequity and injustice. In addition to these socio-economic impacts, the crisis is undermining commitments to address critical environmental issues, including climate change (e.g. OECD, 2020). Acknowledging the significant impacts of such crises on the tourism community, this work discusses how the opportunity can be used to think beyond recovery and proposes a framework to bring justice to the centre of global change for just tourism futures. This work supports and furthers the emerging ‘justice turn’ in tourism studies.

Rethinking tourism for a just recovery

While the focus of governments in every world region is currently to prioritise public health and protect millions of jobs, many recovery solutions focus on distribution of costs and benefits of the crisis (distributive justice). Jamal and Higham (2021, p. 144) discussed this in term of a race “towards a return to neoliberal globalization”. Such critiques might be used to justify turning to responsible tourism recovery approaches. However, Higgins-Desbiolles (2020) has criticised responsible tourism itself as it has failed to recognise the unjust structures of tourism and its exploitative nature. Similar arguments signify how issues of recognition, procedural and distribution injustice are generated in the course of tourism development (Higgins-Desbiolles, Carnicelli, Krolikowski, Wijesinghe, & Boluk, 2019; Jamal, 2019; Rastegar, Zarezadeh, & Gretzel, 2021).

A sustainable and just COVID-19 recovery requires identifying locally tailored solutions to redefine tourism based on local rights, interests and benefits (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020). In this vein, rethinking tourism necessitates promoting justice and equity at the local level. Previously various approaches and perspectives have been applied to investigate the implications of justice for society. For example, Rawls's ideal theory of justice as fairness asserts that ‘all social primary goods - liberty and opportunity, income and wealth, and the bases of self-respect - are to be distributed equally unless an unequal distribution of any or all of these goods is to the advantage of the least favoured’ (Rawls, 1971, p. 303). However, distributive justice approaches such as Rawl's theory have been criticised as they do not consider differences in communities and their values (Daniels, 1989; Jamal, 2019). The concept of justice in tourism is beyond a balance between fair allocation of costs and benefits (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2008; Rastegar, 2020). To better understand the implications of social justice, particularly at the local level, a shift from distributive justice to performative justice has been suggested (Jamal & Hales, 2016; Rastegar et al., 2021). In this context, justice is enacted performatively by recognising local rights, needs and social spaces where the crisis affects vulnerable groups. Following this path forward it is not however without obstacles. Despite the increasing attention to justice issues in the tourism literature, ignoring local values and worldviews has long resulted in injustice. Power asymmetry, dominating profit-focused approaches, and cultural insensitivity are just a few of the outcomes that result. Despite the pervasive presence of such issues, “they often remain implicit or poorly theorised” in tourism analyses (Jamal & Higham, 2021, p. 145).

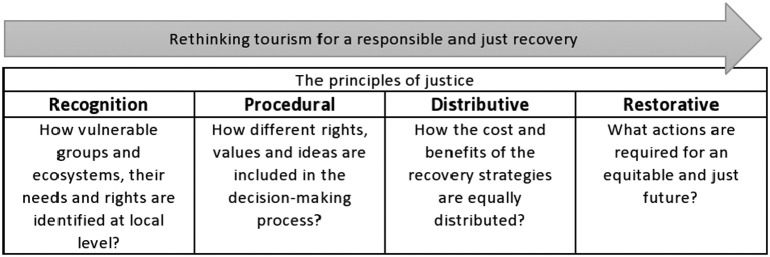

COVID-19 has paralysed global tourism and provided an opportunity to pause, reorientate and rethink (Lew, Cheer, Haywood, Brouder, & Salazar, 2020). Justice must be at the centre of global change and not at the periphery. Recovery strategies cannot be placed in an ethical vacuum. To make justice concerns central to tourism recovery, there is a need for a framework to guide our actions. The proposed justice framework (Fig. 1 ) examines four key dimensions of justice, namely, ‘recognition’ of those most affected by the crisis, a fair ‘procedural’ approach through involvement of different values and ideas in decision-making, a fair ‘distribution’ of costs and benefits of the recovery strategies, and fair ‘restorative’ actions to be taken for an equitable and just future. Pondering the way forward, using the opportunity for a major transformation requires restorative action to design more responsible, ethical and sustainable forms of tourism. However, to achieve this goal, justice cannot be conceptualised “simply as a set of outcomes with a universal threshold, but as an ongoing, interactive process through which different ideas are negotiated about how things should be, how they should be decided and how they should be done” (Pasgaard & Dawson, 2019, p. 3). Here we argue that the focus must be beyond income and material wealth and be concerned with the factors that facilitate a better pathway for the future. In planning the recovery agenda, it is fundamental to address both the socio-economic impacts on vulnerable and marginalised groups as well as the ecological impacts on diverse ecologies.

Fig. 1.

A justice framework to guide tourism recovery.

Redefining tourism will therefore require recognition, procedural and distributive steps to inform any restorative action for a responsible and just recovery. Such an approach is to ensure that those who have least capacity to absorb the shocks from the pandemic are not left behind. Operationalising the proposed framework requires examining the relationship between the justice dimensions and tourism recovery/development strategies. This requires a deliberate process that allows for the questions of justice to guide decisions and actions. Finally, in order to achieve such a transformation, it is necessary to contemplate what values might support this change. COVID-19 has offered a circuit breaker to the ideological domination of neoliberalism and its values (see Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020). “Forms of government interventions, the redevelopment of social safety nets, and the significance of social caring and networks have been the primary responses to challenges of this crisis” (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020, p. 8).

Writing in 2020, Judith Butler countered the selfish individualism that neoliberalism has fostered: “I turn to the problem of individualism in order to foreground the importance of social bonds and interdependency for understanding a non-individualistic account of equality” (Butler, 2020, p. 21). In her philosophical enquiry she suggests we share a common human vulnerability as the basis of our equality which directs us to an understanding of our interdependency. For Butler our very humanity is defined by this interdependency and mutual obligations which this entails. She claims: “the idea of global obligations that serve all inhabitants of the world, human and animal, is about as far from neoliberal consecration of individualism as could be …” (p. 28). Such a value system, renouncing all forms of violence and abuse and instead making meaningful global obligations and interdependency, is a value system on which a just and sustainable future can be built.

Guia (2021, p. 515) also warns us of neoliberalism and its utilitarian ethics failure by contributing to “both commodification and depoliticization in tourism”. The author suggests a radical transformation through a posthumanistic turn as an ethical approach to escape the limitations and inequities of both utilitarian and moralistic approaches (Guia, 2021). We propose taking Guia's recent analyses and furthering these through Butler's analysis of interdependency and mutual obligations. This can provide the link between recent thinking on local empowerment and sovereignty in tourism and reshaping the global tourism system in the aftermath of the pandemic. Such work would particularly emphasise the restorative justice agenda for a multi-pronged strategy to: support empowerment action at the local level (as per Higgins-Desbiolles et al., 2019), encourage states to better control the operations of multi-national corporations in their jurisdictions (as per Pasgaard & Dawson, 2019; Rastegar, 2020) and at the global level change the structures of the global tourism system (see Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020) so that such dangerous tourism dependencies are no longer pressed on developing nations and a global tourism system can be fostered which supports the thriving of all, including people and planet.

Looking forward

The COVID-19 pandemic is not the only threat we confront; there are other global crises such as climate change affecting livelihoods and threatening the chance of survival of many. The pandemic's dynamics has underscored how social, economic and ecological impacts are interwoven and justice approaches are essential for building fairer futures. It is therefore time to “question the sustainability of success defined by growth in visitor numbers or increases in material consumption” (Hall, Scott, & Gössling, 2020, p. 591). This work joins others (Lew et al., 2020; Nepal, 2020) in calling for a full ‘reset’ and ‘transformation’ in tourism to ensure equity and justice in tourism in the post-pandemic era. It is now time to start imagining beyond the widely held view of recovery. The agenda taking us forward should not be getting back to ‘business as usual’ (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020) but rather to build a system to end the cycle of social, economic and ecological exploitation and injustice. Such a ‘just system’ requires weaving notions of justice into tourism research and practice, in order to direct it to more just futures. The framework and thinking proposed here is intended to illuminate a promising and impactful research agenda that furthers the emerging justice turn in tourism studies.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Handling editor: Stoffelen Arie

References

- Butler J. Verso; London: 2020. The force of nonviolence: An Ethico-Political bind. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels N. Vol. 229. Stanford University Press; 1989. Reading Rawls: Critical studies on Rawls' A theory of justice. [Google Scholar]

- Guia J. Conceptualizing justice tourism and the promise of posthumanism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2021;29(2–3):502–519. [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.M., Scott D., Gössling S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies. 2020;22(3):577–598. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles F. Justice tourism and alternative globalisation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2008;16(3):345–364. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles F. Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies. 2020;22(3):610–623. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles F., Carnicelli S., Krolikowski C., Wijesinghe G., Boluk K. Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2019;27(12):1926–1944. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal T. Routledge; London: 2019. Justice and ethics in tourism. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal T., Hales R. Performative justice: New directions in environmental and social justice. Geoforum. 2016;76:176–180. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal T., Higham J. Justice and ethics: Towards a new platform for tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2021;29(2–3):143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Lew A.A., Cheer J.M., Haywood M., Brouder P., Salazar N.B. Visions of travel and tourism after the global COVID-19 transformation of 2020. Tourism Geographies. 2020;22(3):455–466. [Google Scholar]

- Nepal S.K. Adventure travel and tourism after COVID-19 – Business as usual or opportunity to reset? Tourism Geographies. 2020;22(3):646–650. [Google Scholar]

- OECD COVID-19 and the low-carbon transition: Impacts and possible policy responses. Retrieved 13 January from. 2020. http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-and-the-low-carbon-transition-impacts-and-possible-policy-responses-749738fc/

- Pasgaard M., Dawson N. Looking beyond justice as universal basic needs is essential to progress towards ‘safe and just operating spaces’. Earth System Governance. 2019;2:100030. [Google Scholar]

- Rastegar R. Tourism and justice: Rethinking the role of governments. Annals of Tourism Research. 2020;102884 [Google Scholar]

- Rastegar R., Zarezadeh Z., Gretzel U. World heritage and social justice: Insights from the inscription of Yazd, Iran. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2021;29(2–3):520–539. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls J. 1971. A theory of justice: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silva D.S., Smith M.J. Social distancing, social justice, and risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2020;111(4):459–461. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00354-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UN Refugees. Peace, dignity and equality on a healthy planet. 2020 https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/refugees/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Venn A. In: Managing global warming. Letcher T.M., editor. Academic Press; 2019. Social justice and climate change; pp. 711–728. [Google Scholar]