Abstract

Background

Providing a holistic nursing care approach and meeting patients’ satisfaction has become a major health service performance indicator globally. Despite a number of efforts to improve patient satisfaction with nursing care, the practice is still insufficient to meet the required standard in the developing world including Ethiopia. Accordingly, this study was initiated to identify the gaps in adult patient satisfaction with inpatient nursing care practice in Eastern Amhara region, Ethiopia.

Objective

To assess the determinants of patient satisfaction with inpatient nursing care among public hospitals in Eastern Amhara region, northeastern Ethiopia.

Methods

A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted between June 5, 2020 and July 4, 2020 in three public hospitals in the eastern region of Amhara. Systematic random sampling technique was used to recruit 244 participants from the sampled study. Newcastle Satisfaction with the Nursing Scale was used for data collection. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the association and a P<0.05 was deemed to be significant.

Results

The overall proportion of admitted patient satisfaction with nursing care was 118 (48.4%). Besides, the capability of nurses at their job was the highest nursing care satisfaction parameter, 133 (54.5%), while nurse’s awareness of patients’ needs was the lowest parameter, 43 (17.6%), according to this study. Having primary education (AOR=8.575; 95% CI: 1.770, 14.532), being a farmer by occupation (AOR=3.702; 95% CI=1.047–13.087), and having a health insurance scheme (AOR=5.621; 95% CI=1.489–11.213) were the important predictors for patient satisfaction with inpatient nursing care.

Conclusion

The overall patient satisfaction with nursing care in this study was found to be sub-standard and needs a great deal of effort. It is recommended that employees shall be included in the health insurance package.

Keywords: patient satisfaction, nursing care, Northeastern Ethiopia

Introduction

Globally, the healthcare sector has been changed and expanded and, thus, the standard of healthcare is being regarded as a right rather than a privilege.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Council of Nurses (ICN) set the ultimate goal to maintain the highest possible level of health for all people, and the provision of high-quality care to attain this objective.2 Nurses are the first-line individuals most likely to meet, spend the most time with, and rely on during their hospitalization for rehabilitation. In assessing the overall satisfaction of patients’ hospitalization experience, nursing care plays a prominent role.3,4

Patient satisfaction has been defined in a variety of ways by scholars. t has been defined as people’s expectations for healthcare services on the basis of health, disease, quality-of-life, and other requirements.3 The American Nurses Association (2000) describes’ patient satisfaction with nursing care as the perception of patients about the care received during their hospitalization from nursing staff.5 Moreover, patient satisfaction measurement provided key performance information, thus contributing to overall quality management. On this basis, it provides information on the performance of the provider in fulfilling the client’s values and aspirations, topics on which the client is the ultimate authority.6

The World Bank study group in Ethiopia reports that the ratio of health workers to the population is 0.84 per 1,000 population. Although Ethiopia has the highest number of health workers in sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion of health workers in the population is below the WHO level of 2.28 per 1,000 population.7 In Ethiopia, the ratio of nurses (0.26 nurses per 1,000 population) is the second largest community of health workers.8 Ethiopia has also reached the minimum requirement of WHO recommendation of one nurse per 5,000 population.9

Previous studies have identified a number of factors that have a direct effect on patient satisfaction with nursing care. These include perceived expectations of the nurse’s response, perceived experience of compassionate respectfulness and care, and perceived experience on the institutional aspect,10 individual patient socio-demographic factors,11 culture, and health status.12 In addition, other factors include, had a history of hospitalization, surgery, and hostility,13 and the form of nursing care provided.14,15

The Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) has undertaken reform efforts to improve the quality of nursing care and patient satisfaction across the nation over the past 10 years. These include the launch of the Patient Compassionate, Respectful, and Caring (CRC) initiative, the launch of the national dressing code, and the development of national standards for quality improvement in nursing services and audit tools. In addition, nursing and training of nurses in various specialties has been carried out.16,17

Several studies have been developed in recent years to find out how hospitalized patients perceive the care they have received.18,19 However, only single institution and outdated studies have been documented in the study area. This study was therefore initiated to close the gap in information on the status and associated factors of adult patient satisfaction with inpatient nursing care in the Eastern Amhara region, Northeastern Ethiopia. It therefore helps hospital managers, nursing service leaders, and various institutions to strengthen nursing initiatives to promote the quality of nursing care by identifying gaps in resource allocation, training, and skills.

Methods and Materials

Study Area and Period

The study was conducted in three public hospitals in the Eastern Amhara Region (Dessie Comprehensive Hospital, Woldia Comprehensive Hospital, and the Kemisse General Hospital) from June 5, 2020 to July 4, 2020. These three public hospitals have been providing services to more than 10 million people residing in the south wollo zone, the north wollo zone, the Oromia zone, the Waguhumra zone, the afar region, and the south Tigray zone.

Study Design

A facility-based cross-sectional study was used.

Eligibility Criteria

Patients were included in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: adults ≥18 years of age, conscious, articulate, and time-based, person-and place-oriented; admitted to medical, surgical, and gynecological unit for at least 2 days, and able to give informed consent. Those patients who were not co-operative and had serious illness during the study period were removed from the study.

Sampling Size

A single population proportion formula was employed to determine the sample size. The following assumptions were considered: 95% level of confidence, 5% margin of error, as well as 82.5% of inpatient satisfaction on nursing care in a similar study done in Debre Markos Referral Hospital.20 By adding a 10% non-response rate, therefore, the final sample size became 244.

Sampling Procedure

In order to pick a representative sample of patients from each hospital, the total number of patients in the last 6 months has been collected from each hospital. An estimate of the total number of patients to be admitted during the study period (1 month) was then made. Proportional allocation to sample size was done. Based on this, 122 patients were included from Dessie Comprehensive Hospital, 85 patients from Woldia Comprehensive Hospital, and 37 patients from Kemisse General Hospital. A list of patients for stays of 2 or more nights in the wards was obtained once at 10 a.m. and another one at about 2 p.m. Ultimately, a systematic random sampling technique was used to obtain the study subjects for every 8th patient.

Operational Definition

Using the adopted standard questionnaire, the Newcastle Satisfaction with Nursing Scale (NSNS) was used to measure the patients’ satisfaction with nursing care. The scale of satisfaction contains 19-items. On a five-point Likert scale, all parameters are graded (1=not satisfied at all, 2=slightly satisfied, 3=quite satisfied, 4=very satisfied, and 5=absolutely satisfied). The responses of “completely satisfied”/“very satisfied” (5 and 4) were recorded as “satisfied” (1) and those of “quite satisfied”/“barely satisfied”/“not at all satisfied” (3, 2, and 1) were recorded as “not satisfied” (0).21,22

Each individual response was summed up and the mean score was taken as points cut to classify patients as satisfied and dissatisfied. On this basis, those patients who scored above the mean score of satisfaction questions were deemed to be satisfied patients in nursing care and those who scored below the mean score were considered as dissatisfied.21,22

Data Collection Technique and Instrument

A structured questionnaire was used to collect data via a face-to-face interview. The questionnaire included: A) socio-demographic factors such as age, educational status, occupational status, monthly income, and marital status; B) Patient-related characteristics such as ward type, means of admission, type of payment, and room size and available bed; C) Patient perception with inpatient Nursing care items; and D) Newcastle Satisfaction with Nursing Scale: 19 items on a five-point Likert scale (1=Not at all satisfied, 5=Completely satisfied) and designed to measure the multidimensional aspect of nursing care, such as attention, availability, openness, reassurance, individual treatment, information, professionalism, knowledge, ward, and environmental management. The NSNS tool had an excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α=0.96) and construct validity in English and Italian version.21,22 In this study, the NSNS tool had an excellent reliability with a Cronbach’s α of 0.97 and intraclass correlation of 0.975.

Data Quality Management and Analysis

The tool was translated into local Amharic language. Training was given to data collectors and supervisors as well as a pre-test was performed at 5% of the sample size in Akesta referral hospital. The data was cleaned, encoded, and entered into Epi Info version 3.5.3 and exported to SPSS version 25 of the statistical package for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to compute and assess the extent of patient satisfaction. In addition, multivariate logistic regression analysis with a 95% confidence interval was used to evaluate the predictors of patient satisfaction with nursing care. Variables with a P-value of <0.05 were used as a criterion for statistical significance.

Result

A total of 244 respondents admitted to the inpatient department to this study were interviewed with a response rate of 100%.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

The mean age of the respondents was 37.83 years (SD=±16.3 years). The majority of respondents (70, 28.7%), were between 21 and 30 years of age, and 139 (57%) were females. Moreover, 147 (60.2%) were married, and 127 (52%) were urban residents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents in Public Hospitals of Eastern Amhara Region, Northeastern Ethiopia, 2020 (N=244)

| Sociodemographic Variables | Frequency (N=244) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age of respondents | ||

| 18–20 years | 33 | 13.5 |

| 21–30 years | 70 | 28.7 |

| 31–40 years | 55 | 22.5 |

| 41–50 years | 33 | 13.5 |

| 51–60 years | 24 | 9.8 |

| >60 years | 29 | 11.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 147 | 60.2 |

| Single | 62 | 25.4 |

| Divorced | 15 | 6.1 |

| Widowed | 20 | 8.2 |

| Educational status | ||

| Unable to read & write | 48 | 19.7 |

| Able to read & write | 60 | 24.6 |

| Primary education | 49 | 20.1 |

| Secondary education | 48 | 19.7 |

| Higher education | 39 | 16.0 |

| Religious status | ||

| Orthodox | 93 | 38.5 |

| Protestant | 141 | 57.8 |

| Muslim | 10 | 4.1 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Amhara | 223 | 91.4 |

| Oromo | 17 | 7.0 |

| Others | 4 | 1.6 |

| Occupation | ||

| Private work | 68 | 27.9 |

| Government work | 42 | 17.2 |

| Housewife | 56 | 23.0 |

| Farmer | 34 | 13.9 |

| Others | 44 | 18.0 |

| Monthly income | ||

| <500 Birr | 124 | 50.8 |

| 500–1,000 Birr | 46 | 18.9 |

| 1,001–1,500 Birr | 28 | 11.5 |

| >1,500 Birr | 46 | 18.9 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 105 | 43.0 |

| Female | 139 | 57.0 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 127 | 52.0 |

| Rural | 117 | 48.0 |

| Name of hospitals | ||

| Dessie Comprehensive Hospital | 122 | 50.0 |

| Woldia Comprehensive Hospital | 85 | 34.8 |

| Kemisse General Hospital | 37 | 15.2 |

Patient-Related Characteristics

The majority of respondents (73, 29.9%) were allocated to the surgical ward. The main means of admission for most of the respondents (79, 32.4%), was an emergency case. Two hundred and twenty-two (91%) of the respondents were also admitted to rooms with more than two beds per room. Besides, 140 (57.4%) patients obtained care through payment and 157 (64.3%) of the patients remained in hospital for 2–7 nights, with an average period of stay (nights) of 4.7 (SD=±1.83). Thirty-four patients did not realize nurses were allocated for them and 83 (34%) patients spent much of their time (7–12 hours) with their patient attendants rather than the assigned nurses (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient-Related Characteristics of the Respondents in Public Hospitals of Eastern Amhara Region, Northeastern Ethiopia, 2020 (N=244)

| Variables | Response (N=244) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Assigned ward | ||

| Medical | 66 | 27.0 |

| Surgical | 73 | 29.9 |

| Gynecology | 14 | 5.7 |

| Other | 91 | 37.3 |

| Means of admission | ||

| Emergency | 79 | 32.4 |

| Direct to unit | 63 | 25.8 |

| After days procedure | 44 | 18.0 |

| Transferred from another Facility | 58 | 23.8 |

| Ward size | ||

| Single Bed | 17 | 7.0 |

| Two Beds | 5 | 2.0 |

| More than Two Beds | 222 | 91.0 |

| Number of days (nights) stayed in hospital | ||

| 2–7 days | 157 | 64.3 |

| 8–15 days | 69 | 28.3 |

| 16–30 days | 10 | 4.1 |

| 31–60 days | 8 | 3.3 |

| Ward payment type | ||

| Free | 32 | 13.1 |

| Payment | 140 | 57.4 |

| Health insurance | 72 | 29.5 |

| History of previous admission | ||

| Yes | 27 | 11.1 |

| No | 217 | 88.9 |

| Current medical/surgical condition | ||

| Acute illness | 126 | 51.6 |

| Chronic illness | 118 | 48.4 |

| Having another disease/chronic illness in addition to current health problem | ||

| Yes | 12 | 4.9 |

| No | 232 | 95.1 |

| Do you have assigned nurse | ||

| Yes | 210 | 86.1 |

| No | 5 | 2.0 |

| Not sure | 29 | 11.9 |

| Number of hours spent with patient attendant | ||

| 1–6 hours | 61 | 25.0 |

| 7–12 hours | 83 | 34.0 |

| 13–18 hours | 43 | 17.6 |

| 19–24 hours | 57 | 23.4 |

| Attendant relationship with patient | ||

| Parent | 66 | 27.0 |

| Child | 80 | 32.8 |

| Relative | 32 | 13.1 |

| Spouse | 63 | 25.8 |

| Unrelated | 3 | 1.2 |

| Other | 66 | 27.0 |

Patient Perception with Inpatient Nursing Care

Two hundred and ten (86.1%) patients reported that they got the expected nursing care during their stay in the hospitals, and 200 (81.96%) of them recommended their families and friends to visit the hospital that they had stayed in.

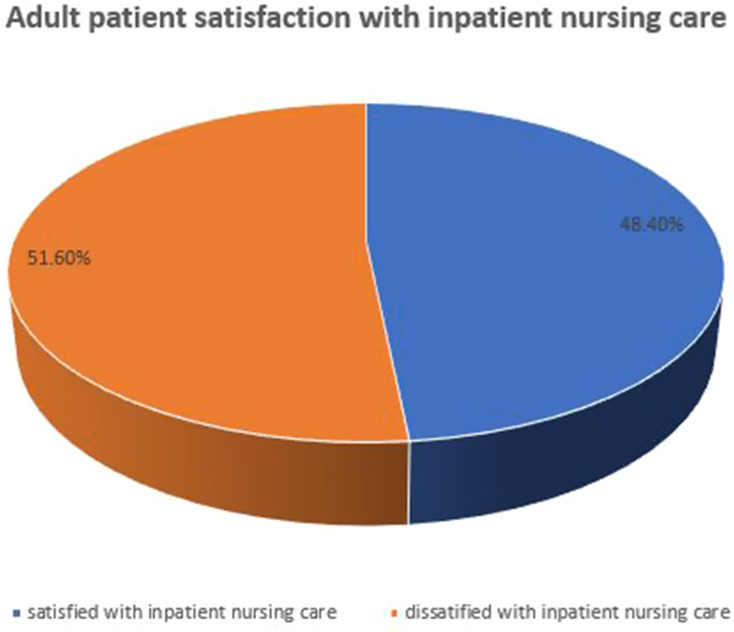

Adult Patient Satisfaction with Inpatient Nursing Care

The magnitude of patient satisfaction with inpatient nursing care was 118 (48.4%) (Figure 1). The capability of nurses at their job was the highest (133, 54.5%) nursing care satisfaction parameter, followed by the amount of time spent by nurses with patients (129, 52.9%). On the contrary, nurse’s awareness of patients’ needs (43, 17.6%), and the amount of privacy nurses gave to them (44, 18.0%) were found to be lowest parameters with regard to patient satisfaction (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Adult patient satisfaction with inpatient nursing care in public hospitals of Eastern Amhara region, northeastern Ethiopia, 2020.

Table 3.

Frequency of Adult Patient Satisfaction with Inpatient Nursing Care Services in Public Hospitals of Eastern Amhara Region, Northeastern Ethiopia, 2020 (N=244)

| Items | Satisfaction N (%) | Dissatisfaction N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| The amount of time nurses spent | 129 (52.9%) | 115 (47.1%) |

| How capable nurses were at their job | 133 (54.5%) | 111 (45.5%) |

| There always being a nurse around when needed | 129 (52.9%) | 115 (47.1%) |

| The amount nurses knew about patients care | 113 (46.3%) | 131 (53.7%) |

| Quickness of nurses upon call by patients | 102 (41.8%) | 142 (58.2%) |

| The way the nurses made patients feel at home | 98 (40.2%) | 146 (59.8%) |

| The extent of information nurses gave to patients about their condition and treatment | 107 (43.9%) | 137 (56.1%) |

| Frequency of check up by nurses | 109 (44.7%) | 135 (55.3%) |

| Nurses’ helpfulness | 104 (42.6%) | 140 (57.4%) |

| The way nurses explained things to patients | 97 (39.8%) | 147 (60.2%) |

| Nurses support of patient’s relatives’ or friends’ minds at rest | 96 (39.3%) | 148 (60.7%) |

| Nurses’ manner in going about their work | 99 (40.6%) | 145 (59.4%) |

| The type of information nurses gave to patients about their condition and treatment | 80 (32.8%) | 164 (67.2%) |

| Nurses’ treatment of each patient as an individual | 62 (25.4%) | 182 (74.6%) |

| Willingness of nurses to listen patients worries and concerns | 53 (21.7%) | 191 (78.3%) |

| The amount of freedom patients was given on the ward | 48 (19.7%) | 196 (80.3%) |

| Willingness of nurses to respond to patient requests | 49 (20.1%) | 195 (79.9%) |

| The amount of privacy nurses gave to patients | 44 (18.0%) | 200 (82.0%) |

| Nurses’ awareness of patient’s needs | 43 (17.6%) | 201 (82.4%) |

Factors Associated with Patient Satisfaction in Nursing Care

According to multivariate logistic regression analysis, being a farmer by occupation, having primary education, and using health insurance were the determinants of patient satisfaction. Those respondents who had primary education were almost nine (AOR=8.575; 95% CI=1.770–14.532) times more likely to be pleased with nursing care than their counterparts. The odds of farmers by occupation were almost four (AOR=3.702; 95% CI=1.047–13.087) times more likely to be satisfied with nursing care than the private employee. Likewise, people using health insurance were 5.621 (AOR: 95% CI=1.489–11.213) times more likely to be satisfied with nursing care than free service consumers. In addition, being admitted to more than two beds per room ward size and in the age group between 31–40 years of age were protective factors for patient satisfaction with inpatient nursing care (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors Associated with Adult Patient Satisfaction with Inpatient Nursing Care in Public Hospitals of Eastern Amhara Region, Northeastern Ethiopia, 2020 (N=244)

| Variables | Patient Satisfaction | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |||

| Educational status | ||||

| Unable to read & write | 29 (60.4%) | 19 (39.6%) | 1 | 1 |

| Able to read & write | 27 (45.0%) | 33 (55.0%) | 1.865 (0.864–4.030) | 2.269 (0.642–8.018) |

| Primary education | 19 (38.8%) | 30 (61.2%) | 2.410 (1.066–5.447) * | 8.575 (1.770–11.532) ** |

| Secondary education | 29 (60.4%) | 19 (39.6%) | 1.000 (0.441–2.266) | 4.050 (0.751–21.851) |

| Higher education | 14 (35.9%) | 25 (64.1%) | 2.726 (1.138–6.527) * | 2.265 (0.299–17.150) |

| Occupation | ||||

| Private work | 46 (67.6%) | 22 (32.4%) | 1 | 1 |

| Government work | 13 (31.0%) | 29 (69.0%) | 4.664 (2.037–10.679) | 5.213 (1.728–15.725) |

| Housewife | 32 (57.1%) | 24 (42.9%) | 1.568 (0.753–3.266) | 3.155 (0.973–10.225) |

| Farmer | 13 (38.2%) | 21 (61.8%) | 3.378 (1.432–7.968) * | 3.702 (1.047–13.087) ** |

| Others | 14 (31.8%) | 30 (68.2%) | 4.481 (1.988–10.100) * | 0.275 (0.037–2.026) |

| Ward payment type | ||||

| Free | 23 (71.9%) | 9 (28.1%) | 1 | 1 |

| Payment | 63 (45.0%) | 77 (55.0%) | 3.123 (1.349–7.231) * | 2.132 (0.644–7.058) |

| Health insurance | 32 (44.4%) | 40 (55.6%) | 3.194 (1.299–7.857) * | 5.621 (1.489–11.213) ** |

| Ward size | ||||

| Single Bed | 1 (5.9%) | 16 (94.1%) | 1 | 1 |

| Two Bed | 1 (20.0%) | 4 (80.0%) | 0.250 (0.013–4.924) | 0.368 (0.011–11.956) |

| More than Two Beds | 116 (52.3%) | 106 (47.7%) | 0.057 (0.007–0.438) * | 0.046 (0.004–0.541) ** |

| Age | ||||

| 18–20 years | 4 (12.1%) | 29 (87.9%) | 1.412 (0.458–4.350) | 0.929 (0.189–4.565) |

| 21–30 years | 41 (58.6%) | 29 (41.4%) | 0.750 (0.274–2.051) | 0.230 (0.049–1.092) |

| 31–40 years | 37 (67.3%) | 18 (32.7%) | 0.343 (0.136–0.870) | 0.074 (0.013–0.438) ** |

| 41–50 years | 16 (48.5%) | 17 (51.5%) | 0.499 (0.207–1.202) | 0.214 (0.044–1.039) |

| 51–60 years | 8 (33.3%) | 16 (66.7%) | 5.118 (1.423–18.410) * | 4.734 (2.66–23.514) |

| >60 years | 12 (41.4%) | 17 (58.6%) | 1 | 1 |

Notes: *Statistically significant at P<0.05 in bivariate analysis and **statistically significant at P<0.05 in multivariate analysis.

Discussion

The proportion of patient satisfaction with inpatient nursing care was found to be 48.4% in this study. Thus, the finding is consistent with that of studies done in India (52%), Pakistan (45%), Eastern Ethiopia (52.75%), and Northeast Ethiopia (52.5%).23–26 Conversely, the magnitude of patient satisfaction with nursing care, in this study, is higher than those done in Ghana (33%) and Debreberhan, Ethiopia (9.2%).27,28 The disparity may be due to a difference in the sample size of the study and the patient flow burden among the study settings. Higher rates of patient satisfaction in nursing care have been registered from Saudi-Arabia (90.67%), Brazil (92%), and the Black Lion Hospital in Addis Ababa (90.1%) than this study,29–31 since these facilities are well-structured and staffed with highly trained health professionals, primarily university-run, and provide special services to their clients.

This study found that those respondents with primary education were 8.575 (AOR: 95% CI=1.770–14.532) times more likely to be pleased with nursing care than to be unable to read and write. The report is consistent with the study conducted in Greece and Debreberhan, central Ethiopia.28,32 This similarity may be attributed to the fact that those educated patients are relatively knowledgeable of healthcare facilities and therefore have higher expectation of nursing care than those who do not have formal education patients. Patient satisfaction is the patient’s view of the treatment offered in relation to the anticipated treatment. Therefore, structured education allows the patient to equate the experience of the treatment rendered by the patient with the anticipated treatment.

The odds of farmers by occupation were nearly four (AOR=3.702; 95% CI=1.047–13.087) times more likely to be satisfied with nursing care than private workers. The report is consistent with a study done in Felegehiwot Hospital, northwestern Ethiopia.33 This similarity might be due to health insurance service coverage in both settings. In this analysis, people using health insurance were 5.621 (AOR: 95% CI=1.489–11.213) times more likely to be happy with nursing care than free service consumers. In Ethiopia, the health insurance program does not directly involve government and private workers, which in turn contributes to workers being required to use the service by subscription. The medical cost burden may have an effect on patient satisfaction in health services, including nursing care.

Strengths and Limitations

I have used a standardized, expert reviewed and pretested data collection tool, but it does not allow us to establish a cause and effect relationship.

Conclusion

More than half of the study participants were unhappy with overall nursing care, rendering hospital nursing care below the standard. Farmers by occupation, primary education, and health insurance usage were significant predictors of patient satisfaction with nursing care. Therefore, it is recommended to include public servants and private workers in the health insurance scheme and awareness creation strategies regarding the rights of patients in nursing care shall be implemented to address the issues of patient satisfaction. In addition, further researches shall be done to evaluate the level of evidence-based nursing practice to assess the satisfaction level of clients.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Dessie, Kemisse, and Woldia hospitals staff, study participants, and Merton office for their kind cooperation. We are also thankful to data collectors.

Funding Statement

No external funds were obtained; only institutional support from the hospitals and wollo university.

Abbreviations

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; COR, crude odds ratio; CRC, compassionate, respectful and caring; FMOH, Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health; ICN, International Council of Nurses; NSNS, Newcastle Satisfaction with Nursing Scale; SD, standard deviation; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data-Sharing Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and are also available from the corresponding author up on request.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

The study protocol was evaluated and approved by wollo university college of medicine and health science with reference No_(WU/CMHS/211/2020) and Ethical clearance was obtained. Permission letters were also obtained from Permission letters was obtained from each hospital’s medical directorate and Merton office. After giving clear and deep understanding about the aim of the study, written consent was obtained from each respondent before the interview is conducted. Moreover, this study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Anonymous data was taken and the confidentiality of participant’s information was secured.

Author Contributions

The author made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

- 1.Samina M, Qadri GJ, Tabish SA, Samiya M, Riyaz R. Patient’s perception of nursing care at a large teaching hospital in India. Int J Health Sci. 2008;2(2):92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Indra V, Cross Sectional A. Study to measure patients’ perception of quality of nursing care at medical wards in selected hospitals, Puducherry. Int J Adv Nurs Manage. 2018;6(3):220. doi: 10.5958/2454-2652.2018.00048.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swarup I, Henn CM, Gulotta LV, Henn III RF. Patient expectations and satisfaction in orthopedic surgery: a review of the literature. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019;10(4):755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2018.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner D, Bear M. Patient satisfaction with nursing care: a concept analysis within a nursing framework. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(3):692–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04866.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirley Teng KY, Norazliah S. Surgical patients’ satisfaction of nursing care at the orthopedic wards in Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia (HUSM). Health Environ J. 2012;3(1):36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goh ML, Ang EN, Chan YH, He HG, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K. A descriptive quantitative study on multi-ethnic patient satisfaction with nursing care measured by the revised humane caring scale. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;1(31):126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feysia B, Herbst C, Lemma W, editors. The Health Workforce in Ethiopia: Addressing the Remaining Challenges. The World Bank; January 4, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinfu Y, Dal Poz MR, Mercer H, Evans DB The health worker shortage in Africa: are enough physicians and nurses being trained? 2009:225–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Haileamlak A. How can Ethiopia mitigate the health workforce gap to Meet Universal health coverage? Ethiop J Health Sci. 2018;28(3):249. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v28i3.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feleke AA, Demise YA, Garedew MG. Patient satisfaction and associated factors on in-patient nursing service at Public Hospitals of Dawro zone, Southern Ethiopia. Int J Caring Sci. 2020;13(2):1411–1420. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rafii F, Hajinezhad ME, Haghani H. Nurse caring in Iran and its relationship with patient satisfaction. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2008;26(2):75. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karaca A, Durna Z. Patient satisfaction with the quality of nursing care. Nurs Open. 2019;6(2):535–545. doi: 10.1002/nop2.237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Yang L, Wang X, Dai J, Shan W, Wang J. Inpatient satisfaction with nursing care in a backward region: a cross-sectional study from northwestern China. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e034196. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan H, Hu S, Thobaben M, Hou Y, Yin T. Continuous primary nursing care increases satisfaction with nursing care and reduces postpartum problems for hospitalized pregnant women. Contemp Nurse. 2011;37(2):149–159. doi: 10.5172/conu.2011.37.2.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Za Z, Am I, Nm B. Satisfaction among pregnant women towards antenatal care in public and private care clinics in Khartoum. Khartoum Med J. 2012;4:2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.FMOH. Ethiopian Hospitals Service Transformation Guidelines (EHSTG). Vol. 1 2016:120–123. [Google Scholar]

- 17.FMOH. Health Sector Transformation in Quality Guideline. Vol. 1 August 12, 2016:175–180. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyu H, Wick EC, Housman M, Freischlag JA, Makary MA. Patient satisfaction as a possible indicator of quality surgical care. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(4):362–367. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamasurg.270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasa AS, Gedamu H. Predictors of adult patient satisfaction with nursing care in public hospitals of Amhara region, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-3898-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alemu S, Jira C, Asseffa T, Desa MM. Changes in inpatient satisfaction with nursing care and communication at Debre Markos Hospital, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Am J Health Res. 2014;2(4):171–176. doi: 10.11648/j.ajhr.20140204.21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas LH, McColl E, Priest J, Bond S, Boys RJ. Newcastle satisfaction with nursing scales: an instrument for quality assessments of nursing care. BMJ Qual Saf. 1996;5(2):67–72. doi: 10.1136/qshc.5.2.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piredda M, Vellone E, Piras G, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the newcastle satisfaction with nursing scales. J Nurs Care Qual. 2015;30(1):84–92. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohanan K, Kaur S, Das K, Bhalla A. Patient satisfaction regarding nursing care at emergency outpatient department in a tertiary care hospital. J Mental Health Hum Behav. 2010;1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan MH, Hassan R, Anwar S, Babar TS, Babar KS, Khan DI. Patient satisfaction with nursing care. Rawal Med J. 2007;32(1):28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed T, Assefa N, Asrat Demisie AK. Levels of adult patients’ satisfaction with nursing care in selected public hospitals in Ethiopia. Int J Health Sci. 2014;8(4):371. doi: 10.12816/0023994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eyasu KH, Adane AA, Amdie FZ, Getahun TB, Biwota MA. Adult patients’ satisfaction with inpatient nursing care and associated factors in an Ethiopian Referral Hospital, Northeast, Ethiopia. Hindawi Public Corp. 2016;Jan(2016):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dzomeku VM, Ba-Etilayoo A, Perekuu T, Mantey RE. In-patient satisfaction with nursing care: a case study at kwame nkrumah university of science and technology hospital. Int J Res Med Health Sci. 2013;2(1). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharew NT, Bizuneh HT, Assefa HK, Habtewold TD. Investigating admitted patients’ satisfaction with nursing care at Debre Berhan Referral Hospital in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e021107. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alasad J, Tabar NA, AbuRuz ME. Patient satisfaction with nursing care: measuring outcomes in an international setting. JONA. 2015;45(11):563–568. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freitas JSD, Silva AEBDC, Minamisava R, et al. Quality of nursing care and satisfaction of patients attended at a teaching hospital. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2014;22(3):454–460. doi: 10.1590/0104-1169.3241.2437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molla M, Berhe A, Shumye A, Adama Y. Assessment of adult patients’ satisfaction and associated factors with nursing care in black lion hospital, Ethiopia; institutional based cross-sectional study, 2012. Int J Nurs Midwifery. 2014;6(4):49–57. doi: 10.5897/IJNM2014.0133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorari A, Theodosopoulou E. Satisfaction with nursing care provided to patients who have undergone surgery for neoplastic disease. Prog Health Sci. 2015;5(1):29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belayneh M. Inpatient satisfaction and associated factors towards nursing care at Felegehiwot referral hospital, Amhara regional state, Northwest Ethiopia. Global J Med Public Health. 2016;5(3). [Google Scholar]