Abstract

Background/Aim

The association between alcohol consumption and subclinical atherosclerosis is still unclear. Using data from a European multicentre study, we assess subclinical atherosclerosis and its 30-month progression by carotid intima-media thickness (C-IMT) measurements, and correlate this information with self-reported data on alcohol consumption.

Methods

Between 2002–2004, 1772 men and 1931 women aged 54–79 years with at least three risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) were recruited in Italy, France, Netherlands, Sweden, and Finland. Self-reported alcohol consumption, assessed at baseline, was categorized as follows: none (0 g/d), very-low (0 − 5 g/d), low (> 5 to ≤ 10 g/d), moderate (> 10 to ≤ 20 g/d for women, > 10 to ≤ 30 g/d for men) and high (> 20 g/d for women, > 30 g/d for men). C-IMT was measured in millimeters at baseline and after 30 months. Measurements consisted of the mean and maximum values of the common carotids (CC), internal carotid artery (ICA), and bifurcations (Bif) and whole carotid tree. We used quantile regression to describe the associations between C-IMT measures and alcohol consumption categories, adjusting for sex, age, physical activity, education, smoking, diet, and latitude.

Results

Adjusted differences between median C-IMT values in different levels of alcohol consumption (vs. very-low) showed that moderate alcohol consumption was associated with lower C-IMTmax[− 0.17(95%CI − 0.32; − 0.02)], and Bif-IMTmean[− 0.07(95%CI − 0.13; − 0.01)] at baseline and decreasing C-IMTmean[− 0.006 (95%CI − 0.011; − 0.000)], Bif-IMTmean[− 0.016(95%CI − 0.027; − 0.005)], ICA-IMTmean[− 0.009(95% − 0.016; − 0.002)] and ICA-IMTmax[− 0.016(95%: − 0.032; − 0.000)] after 30 months. There was no evidence of departure from linearity in the association between alcohol consumption and C-IMT.

Conclusion

In this European population at high risk of CVD, findings show an inverse relation between moderate alcohol consumption and carotid subclinical atherosclerosis and its 30-month progression, independently of several potential confounders.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00394-020-02220-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Alcohol drinking, Atherosclerosis, Carotid intima-media thickness, Progression, Epidemiology

Introduction

The relation between alcohol consumption and atherosclerosis is still far from established. Atherosclerosis, the main cause of cardiovascular disease (CVD), is a complex chronic low–grade inflammatory disease involving accumulation of lipids and inflammatory markers in the arteries [1, 2]. Measurements of intima-media thickness in the carotid artery (C-IMT), assessed through simple, non-invasive diagnostic techniques, are considered valid indicators of subclinical atherosclerosis as well as of risk of incident CVD [3]. Low-moderate alcohol consumption, corresponding to no more than three standard glasses per day in men and two in women, has previously been shown to exert anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, fibrinolytic, and lipid-lowering effects, and to decrease the risk of CVD [4–7]. In contrast, higher alcohol consumption has been associated with increased inflammation, oxidation, and increased risk of CVD [4, 8].

Findings from epidemiological studies investigating the association between alcohol consumption and C-IMT have shown inconsistent results: some found a protective effect of moderate alcohol consumptions [9–20], others suggested that alcohol is always a risk factor [21–26], and yet others showed no association [27–35]. Some of the studies have described the relationship between alcohol consumption and atherosclerosis as linear, with either increased [22, 25] or decreased C-IMT [13, 16] associated with a rise in alcohol consumption, whereas others report a J-shaped association, with a decrease of C-IMT with moderate alcohol consumption and an increase of C-IMT with high alcohol consumption [9, 14, 15, 17]. Few studies, mainly performed in men [23, 24, 27, 28], often with heavy or binge drinking habits [23, 24, 27], have investigated the relationship between alcohol consumption and progression of atherosclerosis, and results were discrepant [12, 23, 24, 27, 28, 36].

We aimed to investigate the relationship between alcohol consumption and subclinical atherosclerosis and its 30-month progression in a European multi-centre study including middle-aged men and women at high risk of CVD.

Methods

Study population

The Carotid Intima Media Thickness (IMT) and IMT-PROgression as Predictors of Vascular Events in a High-Risk European Population study (IMPROVE) is a European multi-centre study including middle-aged men (n = 1772) and women (n = 1931) with at least three CVD risk factors. From 2002 to 2004, participants were recruited from seven different centres located in: Italy (two centres: Milan and Perugia), France (Paris), the Netherlands (Groningen), Sweden (Stockholm) and Finland (two centres in Kuopio). The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each centre. All patients gave written informed consent. A detailed description of the IMPROVE study is reported elsewhere [37, 38].

The present study was conducted in accordance with the STROBE guidelines [39].

Alcohol consumption assessment

At baseline, participants were asked to recall their daily consumption of alcoholic beverages in ml (considering that one glass of wine ≈ 200 ml, a pint of beer ≈ 570 ml and a can of beer ≈ 330 ml) and spirits (one glass of spirit ≈ 25 ml). From these data, total alcohol consumption per day (g/day) was calculated, considering the different content of alcohol in wine, beer and spirits. We created five categories of alcohol: none (0 g/day), very low [(0, 5) g/day], low [(5, 10) g/day], moderate [(10, 20) g/day for women and (10, 30) g/day for men] and high (> 20 g/day for women and > 30 g/d for men). These categories were created to capture approximately none, half, one, two–three, and above three standard glasses per day, respectively. One standard glass is normally defined as containing 8-12 g of alcohol and correspond to alcohol content in one bottle of beer (330 ml), one glass of wine (120 ml), or one glass of spirits (40 ml) [40]. Nineteen participants (11 men and 8 women) with missing information on alcohol consumption were excluded from the analyses.

Carotid IMT measurements

C-IMT, expressed in millimetres (mm), were measured at baseline and after 30 months, by B-mode ultrasonography. For this study, we considered the average of the mean (IMTmean) and the maximum (IMTmax) of the C-IMT measured in the whole carotid arteries and in specific segments i.e. common (CC-IMTmean, CC-IMTmax), bifurcation (Bif-IMTmean, Bif-IMTmax) and internal (ICA-IMTmean, ICA-IMTmax). The 30-month progression was expressed as mean difference between the 30-month measurement and baseline C-IMT divided for the follow-up time (mm/year). Details of the method and its validation are reported elsewhere [37, 38]. For the progression analysis, 422 participants who dropped out during the follow-up period were excluded.

Possible confounders

Smoking status was dichotomized in never- and ever-smoker (current or former smoker). Physical activity was categorized into three groups: low (brisk walk for 10 min less than once a week), medium (brisk walk for 10 min at least two–three times/week) and high (brisk walk for 10 min more than three times/week). Education level was categorized into three groups: less than 9 years of school (compulsory school), 9–12 years of school (secondary) and > 12 years of school (university or college). A score reflecting dietary habits, from 0 to 5 corresponding to level of adherence to a healthy diet, was created as the sum of various dietary items. In details, one point was assigned for each of the following dietary habits which were regarded as “healthy”: olive oil as main source of type of fat consumed, fish intake more than two times per week, meat intake less than 2 times per week, three or more fruits per day and milk less than 4 dl/day. Based on the recruitment centres, latitude was categorized into six different groups capturing North–South geographical gradient; for descriptive purpose a binary variable (North/South) was created, categorized according to a previous publication [37] Sex and age were also considered as potential confounders.

Statistical methods

As descriptive statistics, we report the median and the interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, and the sample proportions (%) for categorical variables.

Quantile regression (QR) models at the 50th (p50, median) and 75th percentiles (p75, 3rd quartile) were employed to evaluate the association between alcohol categories and C-IMT measurements at baseline and after 30 months. The rationale for choosing this statistical approach is that it allows the analyst to regress any percentile of the outcome distribution including median and the high percentiles (75th) of the C-IMT [41]. In this population with right skewed C–IMT, the mean values would not provide information on the right tail of the distribution that can also capture abnormal C-IMT indicative of high risk of CVD [42]. Results are delivered as regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The regression coefficients are interpreted as the 50th and 75th percentile differences in the response variable (a C-IMT measurement) between a specific category of alcohol consumption and the reference category, that corresponds to very low alcohol consumption. Models were adjusted for sex and age (Model 1) plus physical activity, smoking, diet, latitude and education level (Model 2).

To understand the shape of the association between alcohol consumption and the selected percentiles of C-IMT, we also estimated a variation of Model 2 in which we employed restricted cubic splines with four knots at 4, 10, 20 and 30 g/day to model the effect of alcohol consumption. In this analysis, alcohol consumption was treated as a continuous variable, allowing for a nonlinear effect. These analyses were performed only for those associations that were observed to be significant in the main model. To assess departure from linearity, we tested the nullity of the coefficients associated with the second, third and fourth spline basis.

To verify the robustness of the results, we further adjusted Model 2 for potential mediators of the effect of alcohol consumption on C-IMT. The factors included in the model were: body mass index, high density lipoproteins (HDL), lipid lowering treatments (defined as use of fibrates, statins, omega-3 and resins and used as a proxy for hypercholesterolemia), hypertension (defined as anamnestic or use of antihypertensive treatment or SBP ≥ 140 mmHg or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg) and diabetes (defined as self-reported, or use of anti-diabetic medicine or blood glucose > 7 mmol/l).

Based on previous knowledge of sex-specific biological mechanisms in atherosclerosis [43] and that patterns of alcohol consumption and alcohol metabolism vary by sex [44], we performed additional analyses in which men and women were investigated separately. Previous literature on sex-specific associations between alcohol consumption and subclinical atherosclerosis is scarce, in particular in regard to progression.

Sensitivity analyses were performed excluding participants with a CVD event occurring between the time of enrolment and the visit after 30 months.

Missing data were handled by exclusion from each analysis. The total amount of missing data on covariates was less than 4% for baseline and progression analysis, respectively. A flowchart of the study participants is presented in Figure 1, Supplementary Materials.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software (STATA version 12.1, Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Table 1 shows the distribution of descriptive characteristics of the IMPROVE participants included in this study (n = 3684) and in men and women, separately. The majority of the participants reported no alcohol consumption (n = 1678), driven mainly by the large proportion of non-consumers in women (69%). Most of the physically active and non-smoking participants, respectively, had very low alcohol consumption whereas the highly educated more often had a moderate or high alcohol consumption.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by different levels of alcohol consumption of IMPROVE study participants

| Characteristic | Abstainers (0 g/d) | Very Low (> 0–5 g/d) | Low (> 5–10 g/d) | Moderate (> 10–30 g/d)a | High (> 30 g/d)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | |||||

| All | 1678 | 225 | 375 | 738 | 668 |

| Men | 515 | 119 | 179 | 468 | 480 |

| Women | 1163 | 106 | 196 | 270 | 188 |

| Total alcohol (g/d) | |||||

| All | 0 (0;0) | 4 (1.9;4) | 8 (8;8) | 16 (16;16.8) | 36 (32;48) |

| Men | 0 (0;0) | 3.6 (2;4) | 8 (8;8) | 16 (16;21.6) | 40 (32;56) |

| Women | 0 (0;0) | 4 (1.8;4) | 8 (8;8) | 16 (16;16) | 32 (32;33) |

| Age (y) | |||||

| All | 64.4 (59.6;67.3) | 65.3 (60.5;67.4) | 65.6 (60;67.2) | 65.2 (59.5;67.2) | 63.4 (59.1;67) |

| Men | 64.6 (59.5;67.1) | 65.3 (59.9;67.3) | 64.9 (59.3;67.3) | 65.7 (59.3;67.2) | 63.2 (59.1;66.9) |

| Women | 64.2 (59.7;67.5) | 65.2 (61.4;67.8) | 65.9 (60.1;67.1) | 65 (59.8;67.2) | 63.6 (59.4;67.4) |

| Physical activity (%) m3 | |||||

| All | |||||

| Low | 22.3 | 8.4 | 16.3 | 18.0 | 21.6 |

| Medium | 43.7 | 42.2 | 42.8 | 42.9 | 49.4 |

| High | 34.0 | 49.3 | 40.9 | 39.0 | 29.0 |

| Men | |||||

| Low | 16.0 | 7.6 | 14.0 | 13.7 | 20.2 |

| Medium | 42.6 | 41.2 | 41.6 | 40.2 | 49.4 |

| High | 41.4 | 51.3 | 44.4 | 46.1 | 30.4 |

| Women | |||||

| Low | 25.0 | 9.0 | 18.0 | 25.6 | 25.0 |

| Medium | 44.2 | 43.0 | 44.0 | 47.8 | 49.5 |

| High | 30.7 | 47.0 | 38.0 | 26.7 | 25.5 |

| Ever smoker (%) | |||||

| All | 13.3 | 10.2 | 14.7 | 15.7 | 19.2 |

| Men | 14.9 | 10.1 | 19.0 | 16.7 | 18.9 |

| Women | 12.6 | 10.4 | 10.7 | 14.1 | 19.7 |

| Education (%) m34 | |||||

| All | |||||

| ≤ 9 years | 51.6 | 44.6 | 46.4 | 39.6 | 38.5 |

| 9 − 12 years | 25.3 | 25.2 | 23.2 | 26.3 | 27.0 |

| > 12 years | 23.0 | 30.2 | 30.5 | 34.1 | 34.4 |

| Men | |||||

| ≤ 9 years | 44.9 | 50.0 | 44.6 | 37.1 | 37.2 |

| 9 − 12 years | 25.2 | 23.7 | 21.5 | 24.3 | 27.3 |

| > 12 years | 30.0 | 26.3 | 33.9 | 38.6 | 35.5 |

| Women | |||||

| ≤ 9 years | 54.5 | 38.5 | 47.9 | 43.8 | 41.9 |

| 9 − 12 years | 25.5 | 26.9 | 24.7 | 29.7 | 26.3 |

| > 12 years | 20.0 | 34.6 | 27.3 | 26.4 | 31.7 |

| Dietscorec m14 | |||||

| All | 2 (1;3) | 1(0;2) | 2 (1;3) | 2 (1;3) | 2 (1;3) |

| Men | 1(1;2) | 1(1;2) | 1(1;2) | 1(1;2) | 2 (1;3) |

| Women | 2 (1;3) | 1(0;2) | 2 (1;3) | 2 (1;3) | 2 (2;3) |

| Geographical gradient (%)d | |||||

| All | |||||

| North | 57.0 | 93.0 | 62.0 | 59.0 | 40.5 |

| South | 43.0 | 7.0 | 38.0 | 41.0 | 59.0 |

| Men | |||||

| North | 66.0 | 97.0 | 76.0 | 70.0 | 44.0 |

| South | 34.0 | 3.0 | 24.0 | 30.0 | 56.0 |

| Women | |||||

| North | 53.0 | 88.7 | 48.9 | 40.0 | 32.0 |

| South | 47.0 | 11.0 | 49.0 | 60.0 | 67.5 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs (%)e m63 | |||||

| All | 49.0 | 43.0 | 50.0 | 45.0 | 54.5 |

| Men | 46.0 | 43.0 | 43.0 | 44.0 | 55.0 |

| Women | 51.0 | 44.0 | 56.0 | 47.5 | 54.3 |

Results are presented for all the participants (n = 3684), in men (n = 1761) and in women (n = 1923), respectively. Median and interquartile range (in brackets) for continuous variables where not specified; proportions for binary and categorical variables (%)

m missing values

aFor women cut-off > 10 − < 20 g/day

bFor women cut-off > 20 g/day

cDietscore continuous variable created as described in the Method section

dNorth includes Finland (2 centers in Kuopio), Sweden (Stockholm), The Netherlands (Groningen); South: France (Paris), Italy (1 center in Milan, 1 center in Perugia)

eHypolipidemic treatment including statins, fibrate, resins

Hypertension was common among very low consumers of alcohol, and hypertriglyceridemia was common among high consumers. Uric acid was higher among moderate and high consumers, and adiponectin was higher among low consumers. Slightly higher concentrations of total cholesterol and Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL), but not HDL, were also found among moderate and high consumers (vs very low) (Table 1, Supplementary Materials).

Results from analyses of association between alcohol consumption and median C-IMT at baseline are presented in Table 2. When compared to a very low consumption, moderate, high and no alcohol consumption were associated with lower IMTmax. Further, moderate alcohol consumption was associated with lower Bif-IMTmean. These results were independent of confounders included in Model 2. No clear associations were found for alcohol consumption and IMTmean, ICA-IMTmean. and ICA-IMTmax measured at baseline.

Table 2.

Median differences (95% CI) of IMT measured at baseline in relation to alcohol consumption categories

| IMT Baseline | Abstainers (0 g/d) | Very low (> 0 − 5 g/d) | Low (> 5–10 g/d) | Moderate (> 10–30 g/d)a | High (> 30 g/d)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1,678 | n = 225 | n = 375 | n = 738 | n = 668 | ||

| Models | β1 (95%CI) | Reference | β1 (95%CI) | β1 (95%CI) | β1 (95%CI) | |

| IMTmeanm2 | ||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | − 0.06 (− 0.09; − 0.03) | – | − 0.05 (− 0.09; − 0.01) | − 0.07 (− 0.1; − 0.04) | − 0.09 (− 0.12 ; − 0.06) |

| Model 2 | − 0.02 (− 0.05; 0.01) | – | 0.00 (− 0.04; 0.03) | − 0.02 (− 0.05; 0.01) | − 0.02 (− 0.05; 0.01) | |

| IMTmaxm2 | ||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | − 0.32(− 0.48; − 0.16) | – | − 0.25(− 0.43; − 0.06) | − 0.33(− 0.50; − 0.16) | − 0.39(− 0.56; − 0.22) |

| Model 2 | − 0.18 (− 0.32; − 0.04) | – | − 0.11 (− 0.27; 0.06) | − 0.17 (− 0.32; − 0.02) | − 0.16 (− 0.32; − 0.01) | |

| CC–IMTmeanm4 | ||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | − 0.02 (− 0.04; 0.00) | – | − 0.02 (− 0.04; 0.00) | − 0.03 (− 0.05; − 0.01) | − 0.03 (− 0.05; − 0.01) |

| Model 2 | 0.00 (− 0.02; 0.02) | – | 0.00 (− 0.02; 0.02) | − 0.01 (− 0.03; 0.01) | 0.00 (− 0.02; 0.02) | |

| Bif–IMTmeanm2 | ||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | − 0.12 (− 0.18; − 0.07) | – | − 0.08 (− 0.15; − 0.01) | − 0.16 (− 0.22; − 0.10) | − 0.15 (− 0.21; − 0.09) |

| Model 2 | − 0.04 (− 0.10; 0.02) | – | 0.00 (− 0.07; 0.06) | − 0.07 (− 0.13; − 0.01) | − 0.05 (− 0.11; 0.02) | |

| ICA IMTmeanm34 | ||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | − 0.05 (− 0.09; − 0.01) | – | − 0.05 (− 0.10; 0.00) | − 0.06 (− 0.11; − 0.02) | − 0.09 (− 0.14; − 0.05) |

| Model 2 | − 0.03 (− 0.07; 0.02) | – | − 0.03 (− 0.08; 0.02) | − 0.03 (− 0.07; 0.02) | − 0.05 (− 0.09; 0.00) | |

| CC–IMTmaxm4 | ||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | − 0.04 (− 0.08; 0.01) | – | − 0.02 (− 0.07; 0.02) | − 0.04 (− 0.08; 0.00) | − 0.05 (− 0.10; − 0.01) |

| Model 2 | 0.00 (− 0.04; 0.04) | – | 0.01 (− 0.04; 0.05) | − 0.01 (− 0.05; 0.03) | 0.00 (− 0.04; 0.04) | |

| Bif–IMTmaxm21 | ||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | − 0.20 (− 0.33; − 0.08) | – | − 0.12 (− 0.27; 0.03) | − 0.25 (− 0.39; − 0.12) | − 0.29 (− 0.43; − 0.16) |

| Model 2 | − 0.04 (− 0.16; 0.08) | – | − 0.01 (− 0.15; 0.14) | − 0.06 (− 0.20; 0.07) | − 0.10 (− 0.23; 0.04) | |

| ICA IMTmaxm34 | ||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | − 0.12 (− 0.22; − 0.01) | – | − 0.11 (− 0.23; 0.01) | − 0.17 (− 0.28; − 0.06) | − 0.17 (− 0.28; − 0.06) |

| Model 2 | 0.00 (− 0.10; 0.10) | – | 0.00 (− 0.12; 0.12) | − 0.02 (− 0.13; 0.09) | − 0.01 (− 0.13; 0.10) |

Results for all participants of the IMPROVE study (n = 3684). Number of observations for each analysis: IMTmean and IMTmax: Model 1, n = 3682; Model 2, n = 3635; CC-IMTmean and CC-IMTmax: Model 1, n = 3680; Model 2, n = 3633; Bif-IMTmean and Bif-IMTmax: Model 1, n = 3663; Model 2, n = 3616; ICA-IMTmean and ICA-IMTmax: Model 1, n = 3650; Model 2, n = 3603

Model 1 Adjustments for sex and age; Model 2 Model 1 plus physical activity, education, smoking, latitude (categorical) and diet (continuous); m missing values

aFor women cut-off > 10 to < 20 g/day

bFor women cut-off > 20 g/day

The associations between alcohol consumption and median C-IMT progression are shown in Table 3. When compared to a very low consumption, any consumption of alcohol (low, moderate and high) was associated with lower IMTmean progression. Moreover, moderate and high alcohol consumption were associated with lower Bif-IMTmean, ICA-IMTmean. and ICA-IMTmax progression. These results remained significant after the adjustments in Model 2. For the progression, no associations were found for IMTmax and CC-IMT.

Table 3.

Median differences (95% CI) of C-IMT progression in relation to alcohol consumption categories

| IMT progression | Abstainers (0 g/d) | Very low (> 0 − 5 g/d) | Low (> 5–10 g/d) | Moderate (> 10 − 30 g/d)a | High (> 30 g/d)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models | n = 1,471 | n = 209 | n = 332 | n = 658 | n = 592 | ||

| β1 (95%CI) | Ref | β1 (95%CI) | β1 (95%CI) | β1 (95%CI) | |||

| IMTmeanm10 | |||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | − 0.004 (− 0.009; 0.001) | – | − 0.009 (− 0.016; − 0.003) | − 0.008 (− 0.013; − 0.002) | − 0.008 (− 0.014; − 0.002) | |

| Model 2 | − 0.005 (− 0.001; − 0.000) | – | − 0.007 (− 0.013; − 0.001) | − 0.006 (− 0.011; − 0.000) | − 0.008 (− 0.014; − 0.002) | ||

| IMTmaxm2 | |||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | 0.004 (− 0.011; 0.019) | – | − 0.010 (− 0.028; 0.008) | 0.000 (− 0.016; 0.016) | − 0.001 (− 0.018; 0.015) | |

| Model 2 | 0.007 (− 0.011; 0.025) | – | − 0.001 (− 0.022; 0.020) | 0.011 (− 0.008; 0.030) | 0.002 (− 0.018; 0.022) | ||

| CC–IMTmeanm2 | |||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | 0.000 (− 0.004; 0.004) | – | − 0.003 (− 0.007; 0.002) | − 0.003 (− 0.008; 0.001) | − 0.002 (− 0.006; 0.002) | |

| Model 2 | − 0.001 (− 0.005; 0.002) | – | − 0.002 (− 0.006; 0.002) | − 0.002 (− 0.006; 0.002) | − 0.002 (− 0.006; 0.002) | ||

| Bif–IMTmeanm13 | |||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | − 0.012 (− 0.022; − 0.002) | – | − 0.016 (− 0.028; − 0.004) | − 0.020 (− 0.031; − 0.009) | − 0.021 (− 0.032; − 0.01) | |

| Model 2 | − 0.010 (− 0.020; 0.001) | – | − 0.011 (− 0.023; 0.001) | − 0.016 (− 0.027; − 0.005) | − 0.016 (− 0.027; − 0.004) | ||

| ICA IMTmeanm20 | |||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | − 0.010 (− 0.016; − 0.004) | – | − 0.007 (− 0.014; 0.000) | − 0.011 (− 0.017; − 0.005) | − 0.011 (− 0.017; − 0.004) | |

| Model 2 | − 0.008 (− 0.015; − 0.001) | – | − 0.005 (− 0.012; 0.003) | − 0.009 (− 0.016; − 0.002) | − 0.008 (− 0.015; − 0.001) | ||

| CC–IMTmaxm2 | |||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | 0.004 (− 0.004; 0.012) | – | 0.003 (− 0.007; 0.013) | − 0.002 (− 0.011; 0.007) | − 0.004 (− 0.013; 0.005) | |

| Model 2 | 0.004 (− 0.005; 0.012) | – | 0.003 (− 0.007; 0.013) | 0.000 (− 0.009; 0.009) | − 0.003 (− 0.012; 0.006) | ||

| Bif–IMTmaxm13 | |||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | 0.001 (− 0.015; 0.017) | – | 0.000 (− 0.020; 0.019) | − 0.001 (− 0.019; 0.016) | 0.000 (− 0.018; 0.017) | |

| Model 2 | 0.004 (− 0.014; 0.022) | – | 0.005 (− 0.016; 0.027) | 0.004 (− 0.016; 0.024) | 0.002 (− 0.018; 0.023) | ||

| ICA IMTmaxm20 | |||||||

| p50 | Model 1 | − 0.020 (− 0.034; − 0.006) | – | − 0.022 (− 0.039; − 0.005) | − 0.020 (− 0.036; − 0.005) | − 0.028 (− 0.044; − 0.012) | |

| Model 2 | − 0.016 (− 0.031; − 0.002) | – | − 0.017 (− 0.034; 0.000) | − 0.016 (− 0.032; − 0.000) | − 0.022 (− 0.038; − 0.006) |

Results for all participants of the IMPROVE study for whom follow-up data on C-IMT were available (n = 3262). Number of observation for each analysis: IMTmean, Model 1,n = 3252; Model 2, n = 3211; IMT max, CC-IMT mean and CC-IMTmax: Model 1, n = 3260; Model 2, n = 3219; Bif-IMTmean and Bif-IMTmax: Model 1, n = 3249; Model 2, n = 3208; ICA-IMTmean and ICA-IMTmax: Model 1, n = 3242; Model 2, n = 3201

Model 1 Adjustments for sex and age; Model 2: Model 2 plus physical activity, education, smoking, latitude (categorical) and diet (continuous); m missing values

aFor women cut-off > 10 to < 20 g/day

bFor women cut-off > 20 g/day

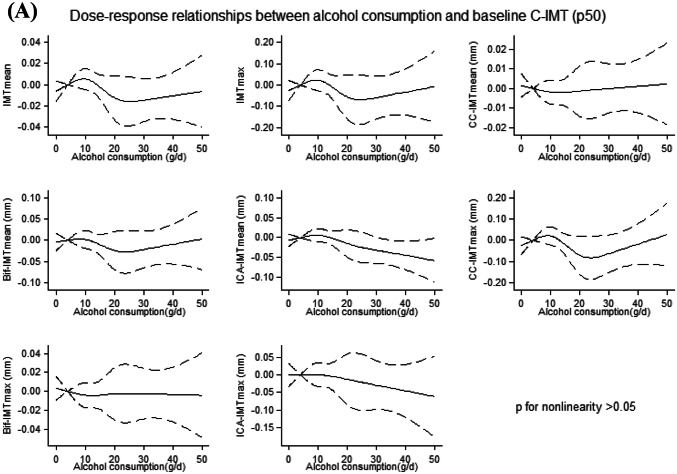

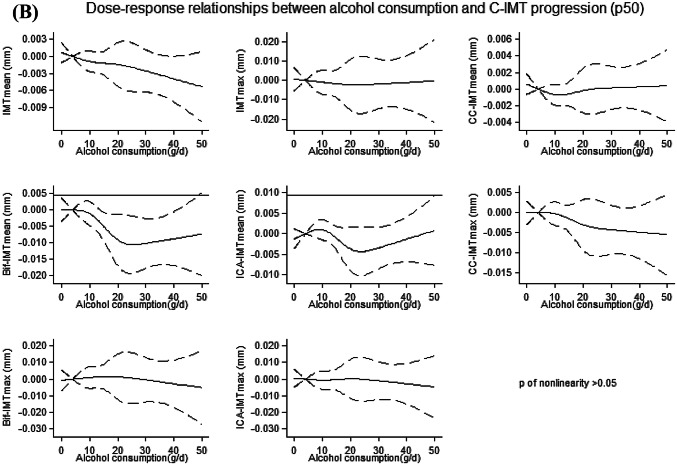

No departure from linearity (p > 0.05) was found for the associations between alcohol consumption and median C-IMT at baseline (Fig. 1a) and progression (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a, b Dose–response relationships between alcohol consumption and each of the considered measurements of C-IMT (p50) at baseline (a) and progression (b). Solid lines: Restricted cubic splines adjusted for sex, age, physical activity, smoking, diet, and latitude, with knots located at fixed points of g/d of alcohol consumption (4, 10, 20, 30). Dashed lines: 95% CI. 4 g/day was used as a reference point. P for nonlinearity was obtained testing the nullity of the coefficients associated with the second, third and fourth spline basis. For a better readability of the graphs, we excluded participants with alcohol consumption > 50 g/d

Analysis of the association between alcohol consumption and the 75th percentile of C-IMT showed that moderate and no alcohol consumption were associated with lower CC-IMTmean at baseline (Supplementary Material, Table 2) whereas no clear associations were found with C-IMT progression (Supplementary Material, Table 3). An indication of linearity was also shown for the dose–response relationships between alcohol consumption and the 75th percentile of C-IMT (Supplementary Material, Figure 1 A–B).

Results from multivariate analysis with additional adjustment for possible intermediate factors were still significant (data not shown), although the associations between moderate alcohol consumption and Bif-MTmean [− 0.06 (− 0.13; 0.00)] and IMTmean [− 0.005 (− 0.011; 0.000)] progression were slightly attenuated.

Analyses stratified by sex showed associations between alcohol consumption and C-IMT in the same direction as the main analysis (Supplementary Material, Tables 4, 5). Significant associations were found for moderate alcohol consumption and C-IMTmax and CC-IMTmean, in men, at baseline, and C-IMTmean, ICA-IMTmean and ICA-IMTmax in women for the progression. There was a clear relation between moderate alcohol consumption and Bif–IMTmean progression both in men and women. However, results were limited by fairly low statistical power.

Regarding the exclusion of participants with CVD events occurring during the period between baseline and the measurements after 30th months (n = 215), results were consistent with the main analysis (data not shown).

Discussion

In this European multi-centre study including participants at high risk of CVD but free of clinical manifestation of CVD at baseline, alcohol consumption was inversely associated, arguably in an approximately linear fashion, with subclinical carotid atherosclerosis and its 30-month progression. These results were independent of sex, age, physical activity, smoking, diet, education and latitude. In particular, compared to very low alcohol consumption, we found that moderate and high alcohol consumption were associated with a lower composite (C-IMTmean) and segment specific (bifurcation and internal carotid) C-IMT progression. At baseline, moderate alcohol consumption was associated with a lower composite (C-IMTmax) and segment specific C-IMT (bifurcations). Lower C-IMT at baseline (C-IMTmax) and progression (internal carotids) were also found for the abstainers.

Our findings of moderate alcohol consumption in relation to decreased C-IMT measured at baseline confirm the results of some earlier studies [9, 10, 13–17, 19, 21, 36] but not all [11, 25, 30, 32–34]. Among the few studies [12, 36] that have investigated the association between alcohol consumption and progression of atherosclerosis including both men and women, our study is one of the largest. Our findings of lower C-IMT progression in relation to moderate and high alcohol consumption, as compared to very low consumption, agree to some extent with those reported from an Italian study (n = 780) [12] but disagree with those of an American study (n = 788) [36]. The Italian study observed protective associations also for light-moderate alcohol consumption (50 g/day), compared to abstainers, in their case in relation to atherosclerotic plaque. Compared to our study, participants were healthier and the follow-up was longer (5 years) [12]. The American study was performed in individuals affected by HIV which may hamper comparability between studies due to presence of different confounding factors in the study base [36].

In contrast to previous studies that have found a linear increase [22, 25] or J-shaped curve for the association between alcohol consumption and C-IMT [9, 14, 15, 17], our findings support a linear decrease of C-IMT (both at baseline and after 30-month follow-up) in relation to increasing alcohol consumption. A linear decrease of IMT was previously reported in two other large epidemiological studies (n > 4000) including Korean men and women [13, 16]. The earlier investigations with opposite findings to our study were performed in Americans [15], Chinese [17], Finnish [25], Germans [14, 22] and Italians [9]. Apart from the study population origins being different, the intake of alcohol in our study was generally lower (median 4 g/d IQR: 0 − 16). In our study, only 4% of all the participants consumed more than 50 g/d (corresponding to more than 3 drinks per day), possibly explaining the discrepant findings. In addition, compared with the compared studies, our population was at higher risk of CVD; in subjects with metabolic disturbances and chronic low-grade inflammation, alcohol consumption may attenuate the effect of the risk factors for atherosclerosis [22]. Moreover, a large proportion of our study participants at high risk of CVD were under pharmacological poly-therapy (including drugs with pleiotropic effect such as statins) that may also have altered the effects of alcohol on C-IMT, regardless of the amount of alcohol consumed [45]. Nonetheless, when we controlled for lipid lowering treatment including statins, the associations were only slightly attenuated.

The biological mechanisms behind a potentially causal protective effect exerted by moderate alcohol consumption on subclinical atherosclerosis and CVD are not completely understood. Epidemiological and experimental studies have suggested that low–moderate (up to three standard drinks) doses of alcohol consumption may have a beneficial effect on the cascade of factors (e.g. lipoprotein, coagulation, adiponectin, inflammatory chemokines, vascular endothelial growth factors) that lead to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques [4, 5, 46, 47]. On the other hand, high alcohol consumption may drive the formation of higher amount of the toxic metabolite acetaldehyde. In turn, this may lead to the formation of biological markers involved in the development of the atherosclerotic process [4].

Our results of differential associations referred to different carotid segments, observed at baseline and progression and in men and women separately, are relatively complex to interpret. Carotid subclinical atherosclerosis measured in different segments has been suggested to have different clinical significance; CC-IMT may reflect hyperplasia or hypertrophy of smooth cells strongly related to age, whereas Bif-IMT and ICA-IMT may indicate a pathological response to low shear stress leading to the development of abnormal carotid atherosclerosis [48]. Also, CVD risk factors and atherosclerotic progression are more strongly associated with Bif-IMT and ICA-IMT than with CC-IMT [48]. We found a consistent protective association between alcohol and Bif-IMT (both at baseline and at progression), and a non-consistent association with CC-IMT and ICA-IMT. Both findings appear reasonable in the light of previous observations.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that it is based on a unique cohort with a large sample size, including both men and women, and with availability of data from several C-IMT segments, allowing to capture different physiological and clinical profiles. Importantly, C-IMT measurements were validated and followed a common protocol for all centres. We cannot exclude, however, that some of the results could be false positives. However, the proportion of significant findings (36% at baseline, and 23% at progression) was much larger than the 5% false positive that could be expected by chance under the null hypothesis.

Our results showed robustness against additional adjustment for CVD risk factors. Obviously, we cannot exclude that other possible unmeasured and/or unknown factors that we have not controlled for may explain the observed associations.

Another strength of our study is that we used as reference category the very low consumers; low alcohol consumption has lately been considered a more appropriate group of comparison than abstainers [49, 50]. It is possible that the group of abstainers includes a number of former drinkers who quit due to the presence of comorbidity or metabolic disorder. Such situation would contribute to explain the finding of a lower C-IMT at baseline and at progression for abstainer in comparison to low consumers.

Our study has also some limitations. Alcohol consumption was self-reported and we had no possibility to validate the reported intake of alcohol. Misclassifications may have led to non-differential misclassification of exposure, diluting the estimated effects. Moreover, we do not have repeated measures of alcohol consumption, so we were not able to detect possible changes over the 30-month follow-up.

Although the study is representative of the European population with classical CVD risk factors, the inclusion of different European countries with different drinking patterns may have introduced heterogeneity in the results. Nordic countries are for example known to have a more binge drinking pattern than the Southern European countries. We adjusted for latitude but we were not able to stratify by countries due to lack of statistical power. However, when we stratified by north and south geographical location of centres, results were similar (data not shown).

We cannot rule out the presence of bias due to non-participation at follow-up. However, the mean alcohol consumption was similar in the missing group (mean 12.0 g/day sd. 18 g/day) as compared to the participant group (mean 12.3 g/day sd. 18 g/day) making selection bias less likely to affect the internal validity of our study.

Finally, the follow-up for progression of atherosclerosis was fairly short (30 months). However, in an experimental study in mice, a clear decrease of atherosclerotic plaque was already observed after 2 weeks, for daily moderate drinking [51].

Conclusion

In this study population at high risk of CVD, moderate alcohol consumption was inversely associated with measurements of C-IMT and its progression. This finding supports the hypothesis of a vascular protective effect exerted by moderate alcohol consumption. However, for clinical implications, it is important to consider that moderate alcohol consumption may increase risk of other diseases such as cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Ackowledgements

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. The authors are deeply thankful to all the participants enrolled in the IMPROVE study. We also thank Gigante Bruna and Discacciati Andrea for their scientific support.

Author contribution

All authors contributed substantively to this work. FL conceptualized the study and performed statistical analyses. FL and KL were involved in the interpretation of the results and drafted the report. All authors were involved in reviewing and editing of the manuscript and approved it.

Funding

This study was supported by the European Commission (Contract number: QLG1-CT-2002-00896), the Swedish Heart–Lung Foundation, the Swedish Research Council (project 8691 and 0593), the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Stockholm County Council (project 562183), and the British Heart Foundation (RG2008/008). RJS is supported by a UKRI Innovation-HDR-UK Fellowship (MR/S003061/1).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Additional members of the IMPROVE study group are listed in the Supplementary Material.

Contributor Information

Federica Laguzzi, Email: federica.laguzzi@ki.se.

IMPROVE Study group:

C. R. Sirtori, S. Castelnuovo, M. Amato, B. Frigerio, A. Ravani, D. Sansaro, C. Tedesco, D. Coggi, A. Bonomi, M. J. Eriksson, J. Cooper, J. Acharya, K. Huttunen, E. Rauramaa, H. Pekkarinen, I. M. Penttila, J. Törrönen, A. I. van Gessel, A. M. van Roon, G. C. Teune, W. D. Kuipers, M. Bruin, A. Nicolai, P. Haarsma-Jorritsma, D. J. Mulder, H. J. G. Bilo, G. H. Smeets, J. L. Beaudeux, J. F. Kahn, V. Carreau, A. Kontush, J. Karppi, T. Nurmi, K. Nyyssönen, R. Salonen, T. P. Tuomainen, J. Tuomainen, J. Kauhanen, G. Vaudo, A. Alaeddin, D. Siepi, G. Lupattelli, and E. Mannarino

References

- 1.Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2011;473(7347):317–325. doi: 10.1038/nature10146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pant S, et al. Inflammation and atherosclerosis–revisited. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19(2):170–178. doi: 10.1177/1074248413504994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nezu T, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness for atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23(1):18–31. doi: 10.5551/jat.31989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brien SE, et al. Effect of alcohol consumption on biological markers associated with risk of coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies. BMJ. 2011;342:d636. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption and atherosclerosis : Meta-analysis of effects on lipids and inflammation. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2017;129(21–22):835–843. doi: 10.1007/s00508-017-1235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiva-Blanch G, et al. Effects of alcohol and polyphenols from beer on atherosclerotic biomarkers in high cardiovascular risk men: a randomized feeding trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25(1):36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes MV, et al. Association between alcohol and cardiovascular disease: mendelian randomisation analysis based on individual participant data. BMJ. 2014;349:g4164. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wurtz P, et al. Metabolic profiling of alcohol consumption in 9778 young adults. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(5):1493–1506. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bo P, et al. Effects of moderate and high doses of alcohol on carotid atherogenesis. Eur Neurol. 2001;45(2):97–103. doi: 10.1159/000052102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrieres J, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness and coronary heart disease risk factors in a low-risk population. J Hypertens. 1999;17(6):743–748. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujisawa M, et al. Factors associated with carotid atherosclerosis in community-dwelling oldest elderly aged over 80 years. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2008;8(1):12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2008.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiechl S, et al. Alcohol consumption and atherosclerosis: what is the relation? Prospective results from the Bruneck Study. Stroke. 1998;29(5):900–907. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.5.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim MK, et al. Harmful and beneficial relationships between alcohol consumption and subclinical atherosclerosis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24(7):767–776. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schminke U, et al. Association between alcohol consumption and subclinical carotid atherosclerosis: the Study of Health in Pomerania. Stroke. 2005;36(8):1746–1752. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000173159.65228.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukamal KJ, et al. Alcohol consumption and carotid atherosclerosis in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(12):2252–2259. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000101183.58453.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YH, et al. Alcohol consumption and carotid artery structure in Korean adults aged 50 years and older. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:358. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie X, et al. Alcohol consumption and carotid atherosclerosis in China: the Cardiovascular Risk Survey. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19(3):314–321. doi: 10.1177/1741826711404501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jerrard-Dunne P, et al. Interleukin-6 promoter polymorphism modulates the effects of heavy alcohol consumption on early carotid artery atherosclerosis: the Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study (CAPS) Stroke. 2003;34(2):402–407. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000053849.09308.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marques-Vidal P, et al. Lack of association between ADH3 polymorphism, alcohol intake, risk factors and carotid intima-media thickness. Atherosclerosis. 2006;184(2):397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moon J, et al. Casual alcohol consumption is associated with less subclinical cardiovascular organ damage in Koreans: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1091. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6000-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knoflach M, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in young males: ARMY study (Atherosclerosis Risk-Factors in Male Youngsters) Circulation. 2003;108(9):1064–1069. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000085996.95532.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zyriax BC, et al. Association between alcohol consumption and carotid intima-media thickness in a healthy population: data of the STRATEGY study (Stress, Atherosclerosis and ECG Study) Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(10):1199–1206. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kauhanen J, et al. Pattern of alcohol drinking and progression of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(12):3001–3006. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.12.3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rantakomi SH, et al. Binge drinking and the progression of atherosclerosis in middle-aged men: an 11-year follow-up. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205(1):266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juonala M, et al. Alcohol consumption is directly associated with carotid intima-media thickness in Finnish young adults: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204(2):e93–e98. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kesse-Guyot E, et al. Associations between dietary patterns and arterial stiffness, carotid artery intima-media thickness and atherosclerosis. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17(6):718–724. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32833a197f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujii K, et al. Risk factors for the progression of early carotid atherosclerosis in a male working population. Hypertens Res. 2003;26(6):465–471. doi: 10.1291/hypres.26.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markus RA, et al. Influence of lifestyle modification on atherosclerotic progression determined by ultrasonographic change in the common carotid intima-media thickness. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(4):1000–1004. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClelland RL, et al. Alcohol and coronary artery calcium prevalence, incidence, and progression: results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(6):1593–1601. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mowbray PI, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors for early carotid atherosclerosis in the general population: the Edinburgh Artery Study. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1997;4(5–6):357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spring B, et al. Healthy lifestyle change and subclinical atherosclerosis in young adults: Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Circulation. 2014;130(1):10–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Britton AR, et al. Alcohol consumption and common carotid intima-media thickness: the USE-IMT Study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017;52(4):483–486. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agx028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zureik M, et al. Alcohol consumption and carotid artery structure in older French adults: the Three-City Study. Stroke. 2004;35(12):2770–2775. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000147968.48379.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demirovic J, et al. Alcohol consumption and ultrasonographically assessed carotid artery wall thickness and distensibility. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. Circulation. 1993;88(6):2787–2793. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Djousse L, et al. Influence of apolipoprotein E, smoking, and alcohol intake on carotid atherosclerosis: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study. Stroke. 2002;33(5):1357–1361. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000014325.54063.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelso-Chichetto NE, et al. The impact of long-term moderate and heavy alcohol consumption on incident atherosclerosis among persons living with HIV. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;181:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baldassarre D, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of baseline data to identify the major determinants of carotid intima-media thickness in a European population: the IMPROVE study. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(5):614–622. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baldassarre D, et al. Progression of carotid intima-media thickness as predictor of vascular events: results from the IMPROVE study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(9):2273–2279. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Elm E, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner C. How much alcohol is in a 'standard drink'? An analysis of 125 studies. Br J Addict. 1990;85(9):1171–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb03442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beyerlein A. Quantile regression-opportunities and challenges from a user's perspective. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(3):330–331. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.ESC Simova Intima-media thickness: Appropriate evaluation and proper measurement, described. E J ESC Counc Cardiol Pract. 2015;13:21. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spence JD, Pilote L. Importance of sex and gender in atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241(1):208–210. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.04.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erol A, Karpyak VM. Sex and gender-related differences in alcohol use and its consequences: Contemporary knowledge and future research considerations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calderon RM, et al. Statins in the treatment of dyslipidemia in the presence of elevated liver aminotransferase levels: a therapeutic dilemma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(4):349–356. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toda M, et al. Low dose of alcohol attenuates pro-atherosclerotic activity of thrombin. Atherosclerosis. 2017;265:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vasdev S, Gill V, Singal PK. Beneficial effect of low ethanol intake on the cardiovascular system: possible biochemical mechanisms. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2006;2(3):263–276. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mackinnon AD, et al. Rates and determinants of site-specific progression of carotid artery intima-media thickness: the carotid atherosclerosis progression study. Stroke. 2004;35(9):2150–2154. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000136720.21095.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stockwell T, Chikritzhs T. Commentary: another serious challenge to the hypothesis that moderate drinking is good for health? Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(6):1792–1794. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naimi TS, et al. Selection biases in observational studies affect associations between 'moderate' alcohol consumption and mortality. Addiction. 2017;112(2):207–214. doi: 10.1111/add.13451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu W, et al. Differential effects of daily-moderate versus weekend-binge alcohol consumption on atherosclerotic plaque development in mice. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219(2):448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.