Abstract

As part of the SAMPL7 host-guest binding challenge, the AMOEBA force field was applied to calculate the absolute binding free energy for 16 charged organic ammonium guests to the TrimerTrip host, a recently reported acyclic cucurbituril-derived clip host structure with triptycene moieties at its termini. Here we report binding free energy calculations for this system using the AMOEBA polarizable atomic multipole force field and double annihilation free energy methodology. Conformational analysis of the host suggests three families of conformations that do not interconvert in solution on a time scale available to nanosecond molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Two of these host conformers, referred to as the “indent” and “overlap” structures, are capable of binding guest molecules. As a result, the free energies of all 16 guests binding to both conformations were computed separately, and combined to produce values for comparison with experiment. Initial ranked results submitted as part of the SAMPL7 exercise had a mean unsigned error (MUE) from experimental binding data of 2.14 kcal/mol. Subsequently, a rigorous umbrella sampling reference calculation was used to better determine the free energy difference between unligated “indent” and “overlap” host conformations. Revised binding values for the 16 guests pegged to this umbrella sampling reference reduced the MUE to 1.41 kcal/mol, with a correlation coefficient (Pearson R) between calculated and experimental binding values of 0.832 and a rank correlation (Kendall τ) of 0.65. Overall, the AMOEBA results demonstrate no significant systematic error, suggesting the force field provides an accurate energetic description of the TrimerTrip host, and an appropriate balance of solvation and desolvation effects associated with guest binding.

Keywords: absolute binding free energy, SAMPL7, force field, AMOEBA

Introduction

The cucurbituril molecular containers are an increasingly important group of host molecules for the binding of ligands, [1,2] particularly ammonium-based organic cations including many alkaloid drugs that carry a positive charge at physiological pH. [3] Development of computationally tractable methods for computing the receptor-ligand binding energy constitutes a long-standing goal of molecular design. For example, accurate interaction between a protein and a potential drug molecule enables the pharmaceutical industry to triage the wide variety of compounds that might bind to a protein target and then focus synthesis efforts on a small subset of computationally promising candidates. [4,5]

The cost of designing an approved drug has increased remarkably in recent decades. Mobley and Klimovich have estimated an accuracy of 2 kcal/mol or better in calculated relative binding free energies would greatly improve the efficiency of structure-based design in the lead optimization phase of drug discovery. [6] The ability to compute absolute, as opposed to relative, binding energies will allow scaffold hopping beyond a single homologous series, and provide access to truely ab initio design of new pharmaceuticals. [7–9] Accuracy requirements are substantially higher for absolute binding protocols since cancellation of systematic error between similar ligands is no longer available.

Blind prediction challenges provide a mechanism to rigorously examine the current status of computational protocols for estimating protein-ligand binding free energies. The SAMPL7 challenge included a host-guest component where methodologies could be applied to test systems based on three distinct host systems: cyclodextrin derivatives, [10] Gibb octa-acids, [11] and the acyclic curcurbituril-derived TrimerTrip clip. [12] Figure 1 shows the TrimerTrip host considered in this work. These relatively small, precisely characterized systems are well-suited to calibrate and optimize computational algorithms with the ultimate goal of application of the methodology to large proteins and drug-receptor interactions. Past SAMPL contests have utilized cucurbit[7]uril (CB[7]), [13,14], curcurbit[8]uril (CB[8]), [15] and an alternative cucurbituril clip [16] as hosts of interest. CB-derived molecular containers are possible tools for drug delivery, with a hydrophobic core and rings of carbonyl groups around the top and the bottom of the cylinder that coordinate cations. [2] Beyond the well-characterized cyclic CB compounds, acyclic clips are capable of binding many guests, including acridine dyes [17] and several drugs of abuse. [12]

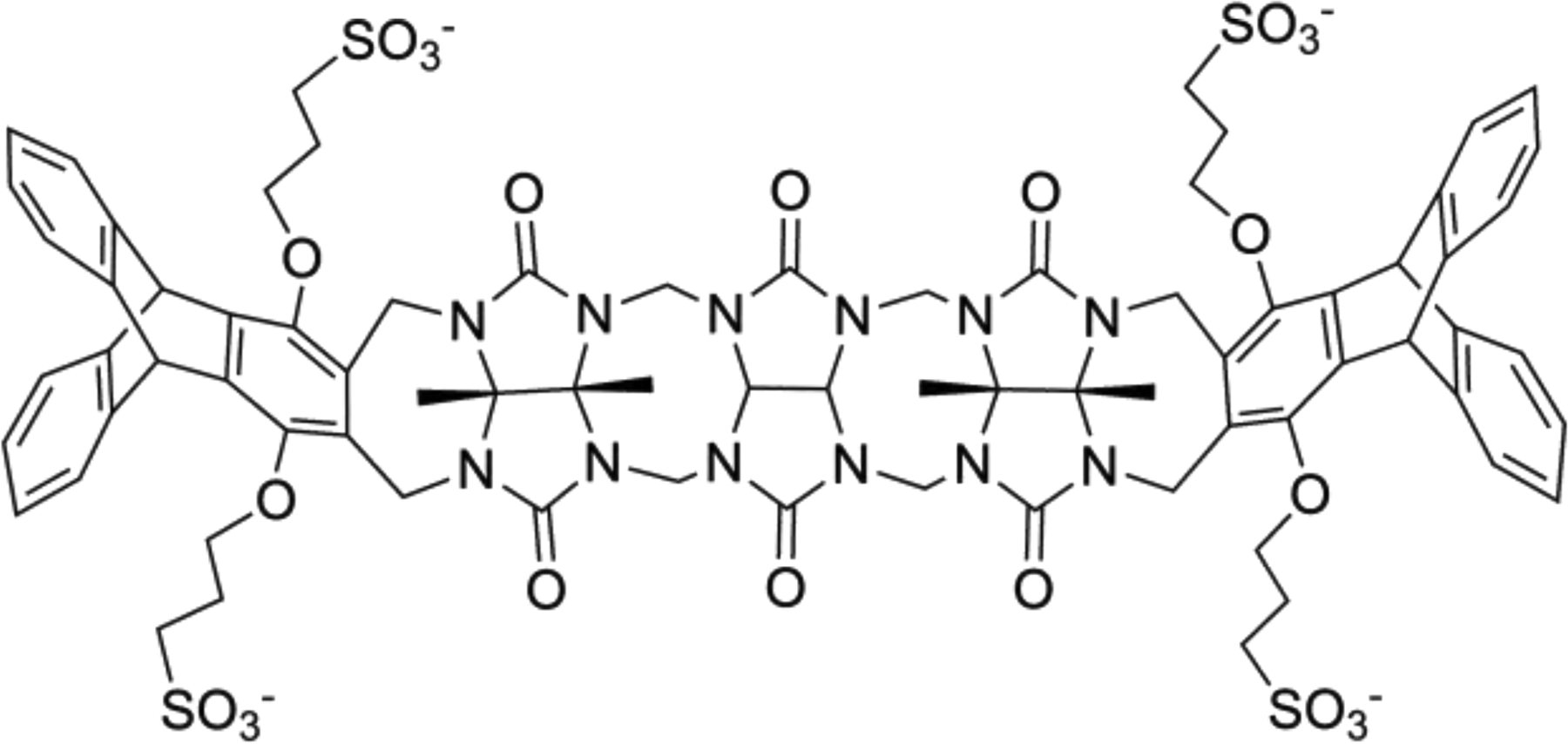

Figure 1.

The TrimerTrip host as part of the SAMPL7 host-guest challenge, containing three cucurbituril repeats connected on each side via a 7-membered ring attached to a modified triptycene derivative.

Efforts to design an optimal procedure to tackle binding free energy calculations range from quantum mechanical approaches to molecular mechanical force fields to empirical docking algorithms. Selection of a methodology involves striking a balance between computational efficiency and model accuracy that proves useful in applications such as drug design. Force fields employed within molecular dynamics simulations provide an excellent means to effectively sample a variety of configurations and energetics for interacting systems. Traditional force fields, including Amber, [18] CHARMM, [19] and OPLS-AA, [20] typically use fixed atomic point charges and Coulomb’s law to describe electrostatics and a Lennard-Jones term for nonbonded van der Waals interactions. These fixed charge models only approximately reproduce the molecular electrostatic potential and neglect response of the system due to polarization effects. The AMOEBA model deals with these issues by means of permanent atomic multipole moments through the quadrupole and atomic induced dipole polarization. [21] Polarizable force fields like AMOEBA promise greater transferability and accurate prediction of thermodynamic properties, while allowing parameterization directly from high-level ab initio calculations. AMOEBA force field parameters have been developed for water, [22,23] organic molecules, [24] proteins, [25] transition metals [26] and nucleic acids. [27] For example, several previous studies have used AMOEBA for modeling of protein-ligand binding free energies. [28] [29] [30]

In this work, the TrimerTrip host from the SAMPL7 host-guest exercise was examined. The corresponding guests spanned a selection of organic ammonium cations varying from narrow, linear alkyl chains to wider adamantyl structures, and between mono- and dication species. This test set represented a diverse group of 16 structures, ranging in size, structure, charge, and rigidity. [12] The polarizable atomic multipole AMOEBA force field, in conjunction with careful conformational analysis of the host molecule and free energy perturbation calculations, was applied to this host-guest set as part of the blind challenge. Analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the AMOEBA binding free energy protocol are provided, along with suggestions for future improvements.

Methodology

The host-guest systems reported here were part of the recent SAMPL7 community exercise, which invited computational researchers to predict unknown host-guest binding energies that were measured contemporaneously by experimental groups. A host for this exercise was the cucurbituril-derived clip, TrimerTrip, which adopts a letter “C”-like shape around three central repeats of a cucurbituril substructure. Initial molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were used to explore conformations available to this host, as well as possible binding poses for each host-guest complex. MD simulations and analysis calculations were performed with the Tinker [31] and Tinker-OpenMM [32] software packages using the AMOEBA force field. The Force Field Explorer (FFE) and VMD programs were used for visualization of model structures and MD trajectories.

AMOEBA Parameterization.

Force field parameters for TrimerTrip and individual guests were developed following the standard AMOEBA protocol, [24] as described here briefly. Ab initio calculations were utilized in order to derive the electrostatic parameters. Initial structures were first optimized at a “low-level” of theory via MP2/6–311G(1d,1p) optimizations performed with the Psi4 quantum chemistry package. [33] Distributed Multipole Analysis (DMA) via the GDMA program [34,35] determined initial atomic multipole estimates, including the charge, x-, y-, and z-components of the dipole, and the quadrupole tensor, from the low-level ab initio results. Polarization was removed from the ab initio results with the Tinker poledit program to avoid double counting upon activation of the AMOEBA polarization model. The optimized structures were then used as input for a single-point “high-level” calculation at the MP2/aug-cc-pVTZ level. Keeping the atomic partial charges fixed, the atomic dipole components and quadrupole values were fit to the electrostatic potential on a grid of points outside the molecular envelope and generated from the high-level ab initio wavefunction. Rotatable bonds were used to separate each molecule into polarization groups and a Thole damping value [36,37] of 0.39 was used for each atom, as were the standard AMOEBA atomic polarizabilities. For each guest, symmetry was imposed during parameterization. Electrostatic parameter generation utilized the poledit and potential programs from the Tinker 8 software. [31] Valence parameters were found by various means, including fitting to QM-optimized structures, transfer and interpolation from previously determined AMOEBA parameters, [24,25] or taken from the corresponding MMFF parameters. [38–42] An automated procedure encompassing most of the above protocol was used to generate and validate the guest parameters. The AMOEBA 2003 water model was used in all cases. [23]

Simulation Protocol.

Starting host-guest structures were obtained by first positioning the guest in the middle of the host cavity with the Tinker xyzedit program. Then a long, unrestrained simulation of 50 ns was performed with the complex embedded in a 50 Å cubic box containing AMOEBA water molecules and equilibrated at 298 K and 1 atm. The last frame of this simulation was used as the initial structure for subsequent free energy windows. A standard double annihilation scheme was used as the basic free energy protocol. A series of windows were run to first annihilate the electrostatics in the guest molecule, followed by annihilation of guest van der Waals (vdW) interactions. Two independent free energy legs were employed: the guest solvated in water (solvation leg) and the host-guest complex solvated in water (bound leg). The double annihilation scheme was applied to both legs and the difference between these two legs was taken as the absolute binding free energy. As detailed below, a single flat-bottom harmonic distance restraint was added between the host and guest to maintain binding.

For each guest, a set of MD simulations were run for the solvation and bound series. Those MD simulations were performed on NVIDIA GTX 970 and 1070 graphical processing units (GPUs) with the equations of motion integrated using a two-stage RESPA integrator [43–45] with an inner time step of 0.25 fs and a 2 fs outer time step. Snapshots of the MD trajectories were saved every 1 ps. Each free energy window was run for 10 ns. As with the initial exploratory trajectories, each MD simulation used a 50 Å water box, and was run under isothermal-isobaric conditions (NPT) at 298 K and 1 atm. A Bussi thermostat [46–48] and Monte Carlo barostat [49,50] were used to enable the NPT ensemble. Sodium ions were added to the host-guest systems to neutralize the host, but no ions were added to neutralize the guest molecules. All periodic simulations used particle mesh Ewald summation (PME) for polarizable multipoles with a 7 Å cutoff for real space electrostatics. The induced dipoles were converged to an RMS change 0.00001 Debye. Pairwise vdW energies were splined to zero over a 0.9 Å window ending at the cutoff distance of 9 Å, and were incremented by an isotropic vdW long range correction.

Binding Free Energy Methodology.

For the calculation of absolute binding free energies, two independent series of free energy simulations must be evaluated: the guest molecule solvated in explicit water, and the solvated host-guest complex. The binding free energy is then estimated as the difference between free energy sums for each of these two series. All free energies were calculated via the Tinker bar program, which implements the free energy perturbation (FEP) [51] and Bennett acceptance ratio (BAR) methods. [52]

The initial 10% (1 ns) of each sampling window was discarded as equilibration. A soft-core vdW formulation specially tuned for AMOEBA was used with the vdW annihilation protocol to avoid sampling issues near λ = 0. [28] A lambda value spacing of about 0.1 was used for initial windows, with additional intermediate windows run if there was hysteresis between the forward and backward FEP energies. Post-processing of the remaining 9 ns of production simulation for each window used FEP and BAR between adjacent windows to find the difference in free energy between the solvated and bound host-guest legs. Statistical error from bootstrapping was computed for each BAR free energy estimator, and these errors were summed over all contributing free energy windows to get a total statistical error for each binding prediction.

TrimerTrip Conformational Analysis.

Optimization of TrimerTrip using the AMOEBA force field was performed using the Tinker minimize program in the gas phase and with generalized Kirkwood implicit solvation. The resulting unfolded structures were solvated in periodic water boxes followed by MD simulations of 50 to 100 nanoseconds. Additional periodic boundary MD simulations in aqueous solution of at least 50 ns were started from each the three structure families depicted in Figure 2.

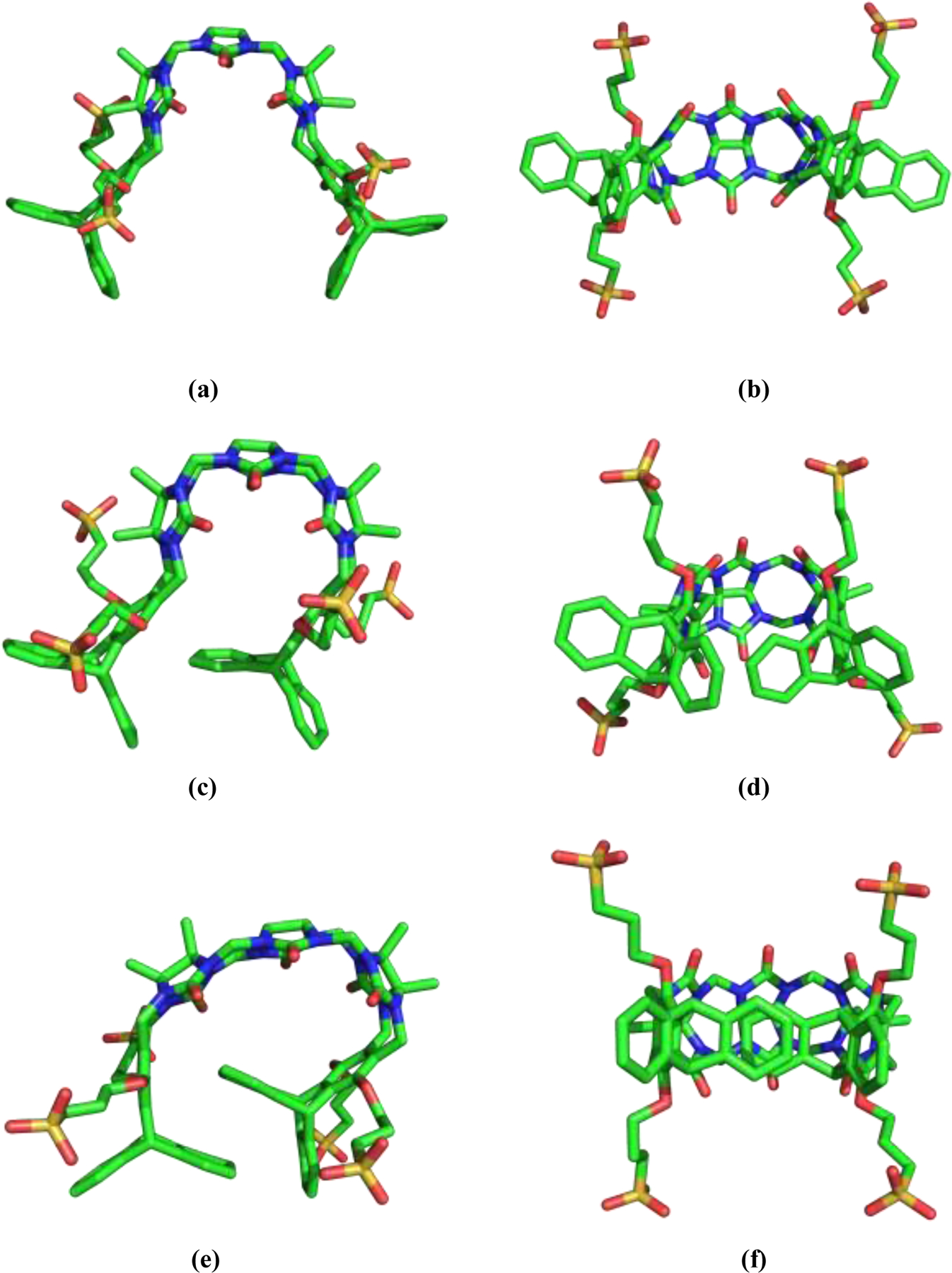

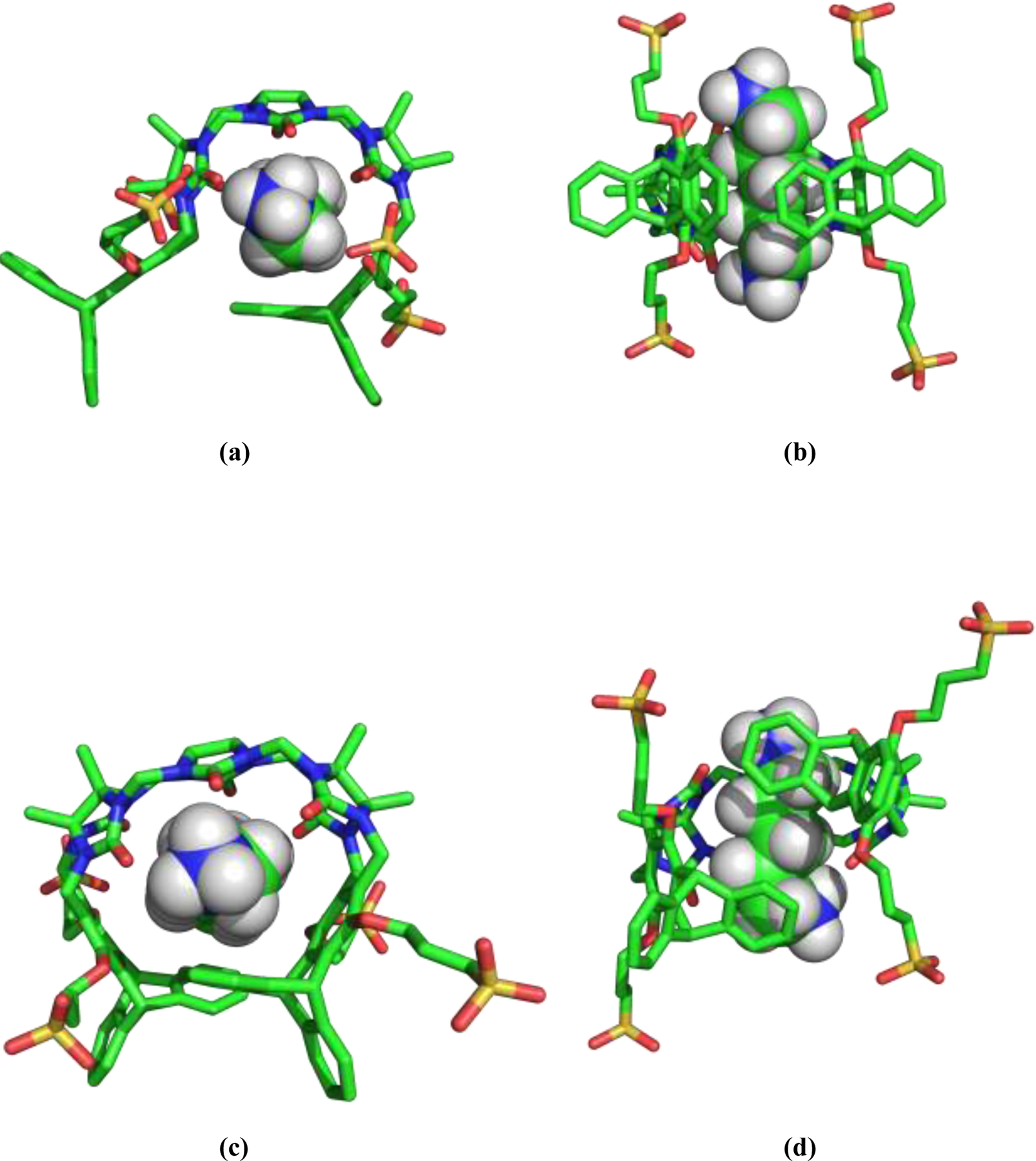

Figure 2.

The three main conformations available to the TrimerTrip host in solution: (a-b) two orthogonal views of a typical “open” conformer, (c-d) views of an “indent” conformer, and (e-f) views of an “overlap” conformer.

TrimerTrip 7-Membered Ring Model.

The model compound shown in Figure 3 was used to examine the conformational energetics of the 7-membered rings critical to the structure of the TrimerTrip host. Following manual model building in FFE, full gas phase optimizations of the two minimum energy conformers of the model compound, as well as the transition state connecting them, were performed at the MP2/6–311G(1d,1p) level using Psi4.

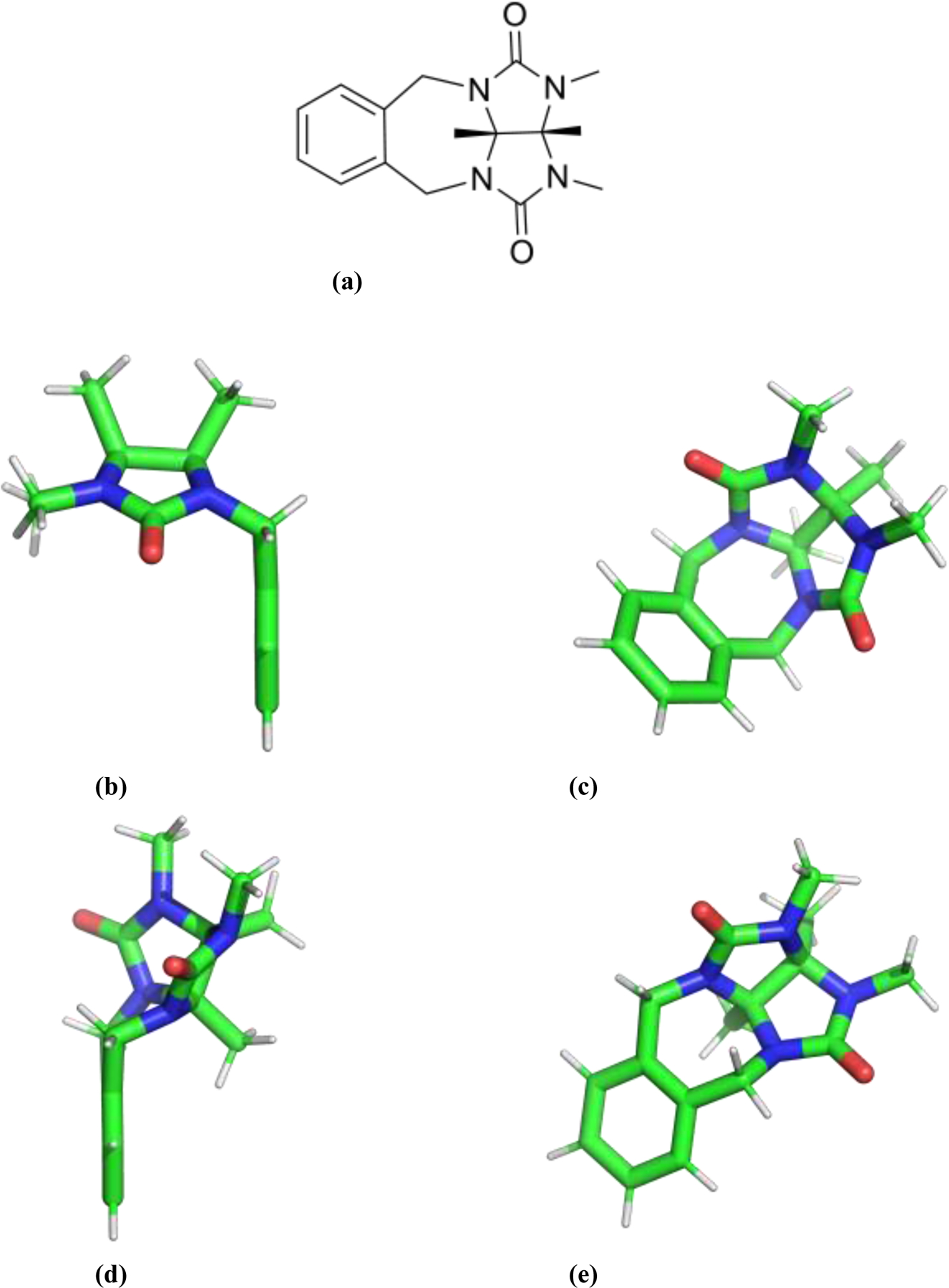

Figure 3.

(a) Model compound used to examine the conformations of the 7-membered ring adjacent to the triptycene moiety. (b-c) two views of the lowest energy minimum of the model compound as determined via optimization at the MP2/6–311G(1d,1p) level. (d-e) two views of the alternative minimum energy conformer.

Free Energy Simulation Series.

Our binding protocol first turns off electrostatic interactions involving the guest, followed by removal of guest vdW interactions. For both the guest solvation and bound host-guest series of simulations, eleven windows were run to annihilate the electrostatics, by decreasing the λ value from 1.0 to 0.0 in 0.1 steps. The electrostatic coupling is achieved by simply using λ as a linear scale factor to reduce guest multipole and polarizability parameters prior to MD simulation. For the annihilation of vdW interactions, coupling is controlled via a soft core modified AMOEBA buffered 14–7 vdW function, and a more elaborate set of 18 additional intermediate windows were run using λ values from the set {1.0, 0.95, 0.9, 0.85, 0.8, 0.775, 0.75, 0.725, 0.7, 0.675, 0.65, 0.625, 0.6, 0.575, 0.55, 0.525, 0.5, 0.4, 0.0}. In total, 29 windows were run for each solvated series of bound host-guest complex series.

Host-Guest Restraints.

For the host-guest free energy simulations a single flat-bottom distance restraint was added between a subset of host atoms and a group of guest atoms. The use of such restraints has been proposed to simplify sampling for windows near the fully decoupled or annihilated states, where the guest has little interaction with the rest of the system. The flat-bottom parabolic function u(r) has the following form:

where k is the force constant, r is the distance between the centers of mass of atom subsets of the host and guest, and r1 and r2 define the inner and outer range of the flat-bottom region. According to Hamelberg and McCammon, [53] the analytical correction for this geometric restraint is ΔGcorr = kBT ln(c°V), where c° is the unit concentration and V is equal to the integral . The free energy, enthalpy and entropy for the restraint correction were computed via the Tinker freefix utility. To determine parameters for the geometric restraint, an initial unrestrained host-guest simulation was run for 50 ns. The restraint atom groups and distance were chosen so the restraint never escaped the flat-bottom region during unrestrained simulation. For most guests, a restraint force constant of 15 kcal/mol/Å2 was used, and the inner and outer radii for the flat-bottom region were set to 0 Å and 5 Å.

Guest Gas Phase Simulations.

As with the solvated and host-guest legs outlined above, a total of 29 windows were run to annihilate each guest in the gas phase. These simulations were performed with the canonical Tinker code running on CPUs, using the standard stochastic integrator available in Tinker. Gas phase window MD trajectories of 1 ns were collected at a target temperature of 298K with 0.1 fs time steps and snapshots saved every 0.1 ps.

Umbrella Sampling between Unligated Host Conformers.

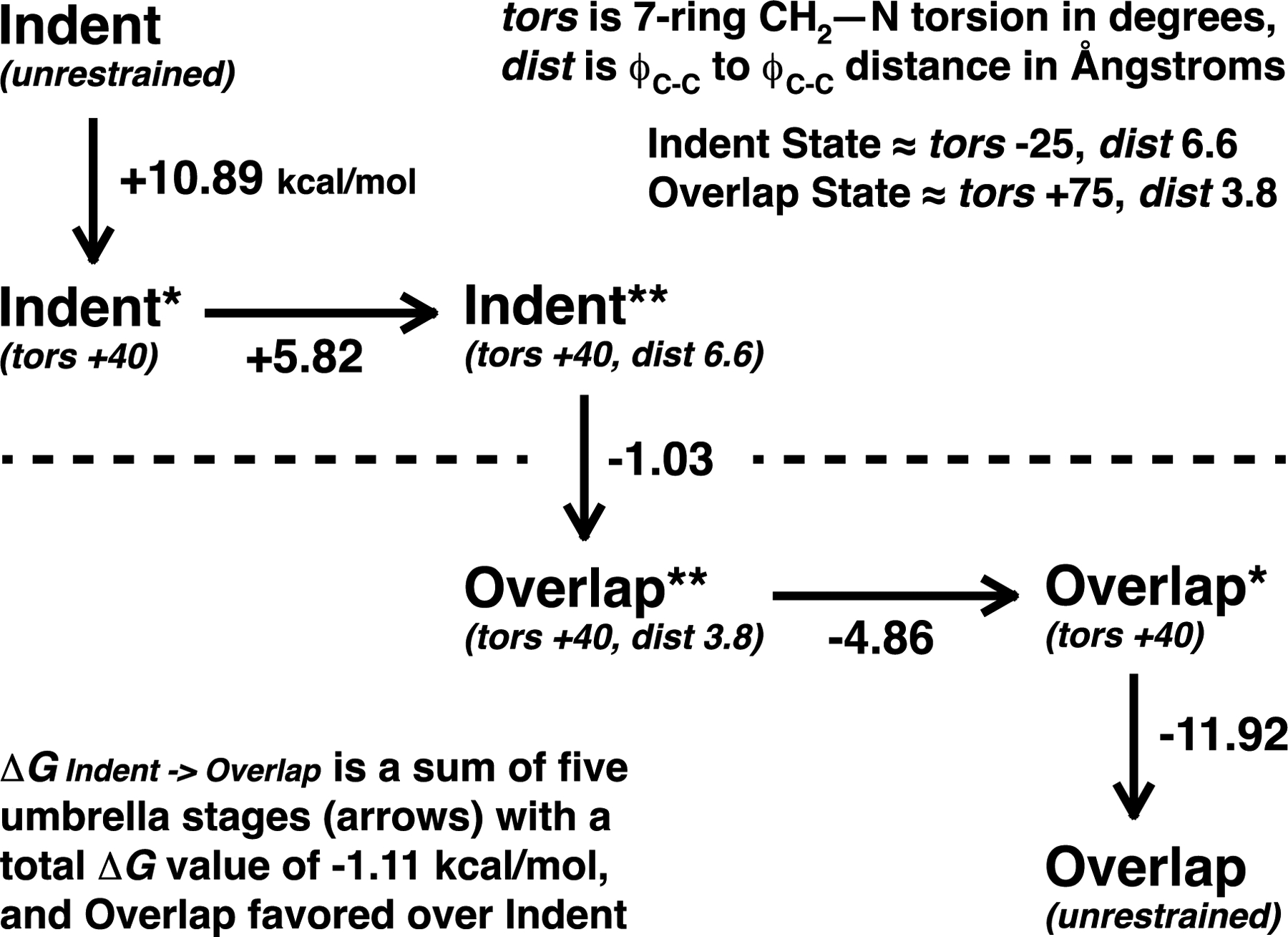

Two conformations of the host were identified with guests bound, referred to below as the “indent” and “overlap” conformers. To compute the free energy difference between these two conformers, the umbrella sampling method was used. The indent form was gradually converted to the overlap form via a smooth pathway created by adding torsional and distance restraints across successive simulations. Torsional restraints of equal magnitude and opposite sign were applied to the two symmetrical CH2−N bonds on the seven-membered ring adjacent to the outermost triptycene group. Distance restraints were used to restrict the distance between two carbon-carbon bond centroids on the two closest triptycene rings at the ends of the host. In the unrestrained indent form, the torsional angle value is near −25 degrees, and the bond distance is roughly 6.6 Å. For the unrestrained overlap structure, the torsional angle is close to +75 degrees, and the distance value is 3.8 Å. The whole umbrella process consisted of five stages to perform the interconversion. For the first stage, a series of windows were run from the unrestrained indent form to turn on a torsional restraint at −25 degrees, then slowly change the restraint to +40 degrees in small steps. In a second stage, the distance restraint of 6.6 Å was turned on while maintaining the torsional restraint at +40 degrees. The force constant of the distance restraint was increased from 0.0 to 5.0, while the force constant of the torsional restraint was increased from 0.01 to 10.0 kcal/mol/degree2. In the third stage, the distance restraint was changed from 6.6 Å to 3.8 Å in 0.2 Å steps. The fourth stage was the reverse of the second stage, with the distance restraint at 3.8 Å turned off while keeping the torsional restraint at +40 degrees. In a final stage, the torsional restraint was changed from +40 degrees to +75 degrees in 5 degree increments, and then removed entirely to yield the unrestrained overlap form. The above protocol consisted of 55 MD simulations of 5 ns each, and free energies were calculated via BAR using the final 4 ns of data from adjacent windows. The sum of free energies for the five umbrella stages yields the total free energy difference between the indent and overlap conformers.

Results and Discussion

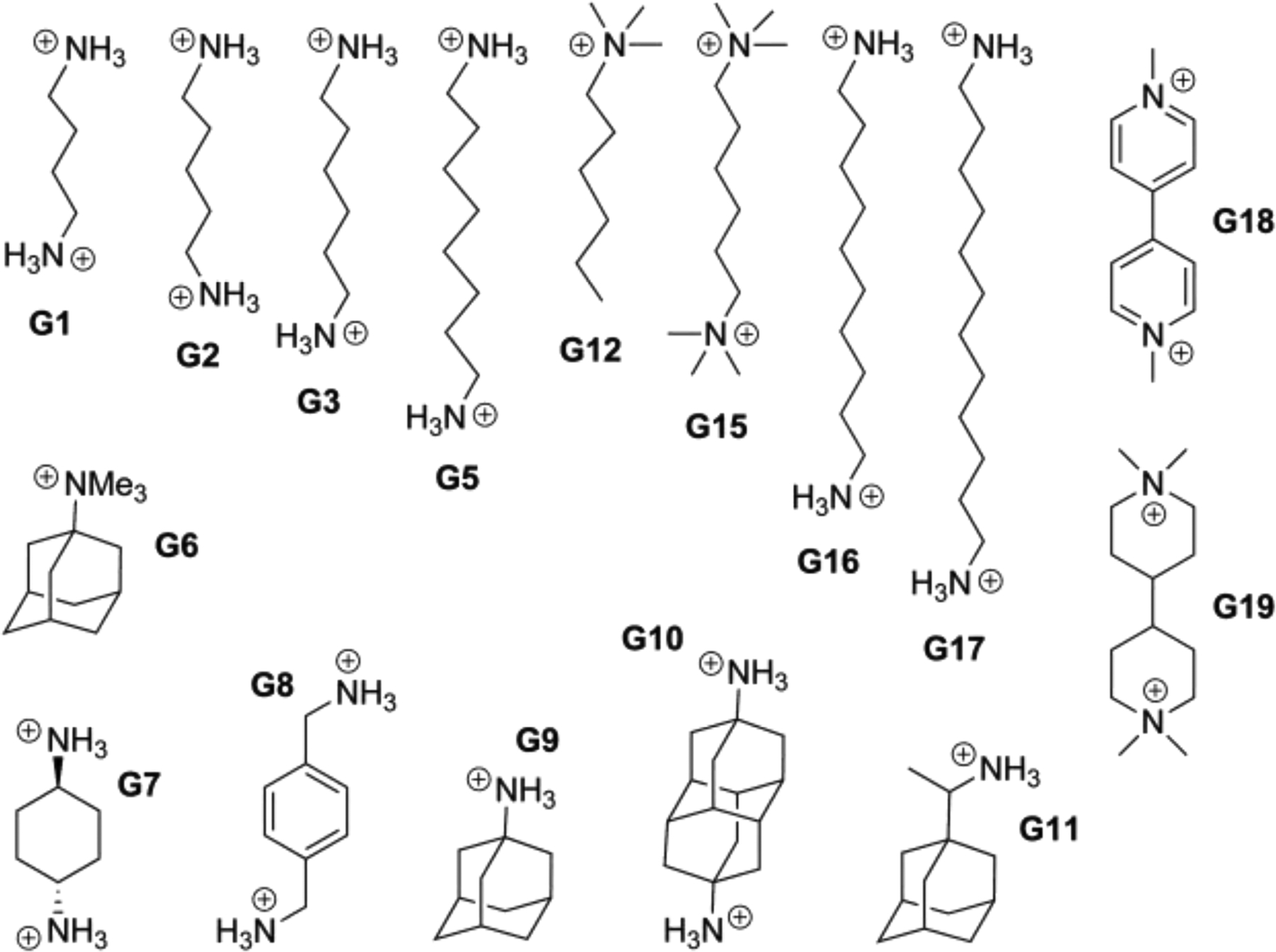

The solvation free energy in pure water was computed for each of the guests in Figure 4. A series of solvated free energy MD simulations at varying electrostatic and vdW λ values were performed as described above. The free energy difference between adjacent MD windows was computed via the BAR algorithm. An additional free energy series was calculated for each isolated gas phase guest molecule using Langevin dynamics, with free energies again found using BAR. The final solvation free energy of a guest was then found as the difference between the totals for its gas phase and solvation series. Final values for all 16 guests are given in Table 1, and the totals for the solvated legs alone is given in a column of Table 2. While experimental solvation energies are not available, the computed values are in rough agreement with expectation. In particular, dications obviously have much more favorable solvation energies than singly charged guests. Comparison across the set {G1, G2, G3, G5, G16, G17} shows that each additional methylene group alters the aqueous solvation by decreasing amounts ranging from 11.7 to 2.3 kcal/mol over the series. Further comparison of G9 and G6, as well as G3 with G15, indicates each methyl appended to an alkyl ammonium group decreases the free energy by 6–8 kcal/mol, which is in good agreement with our previous calculations on sequential methylation of ammonia. [54]

Figure 4.

The sixteen guests for the SAMPL7 TrimerTrip host-guest exercise, all of which contain either one or two protonated ammonium-like nitrogens at the experimental pH. The numbering used is that provided by the SAMPL organizers.

Table 1.

The guest solvation energies, ΔGsolv, for the 16 guests as part of the SAMPL7 TrimerTrip host-guest challenge. Units are kcal/mol. Statistical errors for the ΔGsolv values were computed by performing bootstrap analysis on the BAR free energy from each individual perturbation window from both the gas phase and solvated series, and summing the errors over all windows. For all guests, the total statistical error falls within the range from 0.18 to 0.24 kcal/mol.

| Guest | ΔG solv | Guest | ΔG solv |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gl | −182.42 | G10 | −162.97 |

| G2 | −171.74 | Gl1 | −50.44 |

| G3 | −164.22 | Gl2 | −37.68 |

| G5 | −153.68 | Gl5 | −120.51 |

| G6 | −36.72 | Gl6 | −149.50 |

| G7 | −181.75 | Gl7 | −144.92 |

| G8 | −171.92 | Gl8 | −138.86 |

| G9 | −54.35 | Gl9 | −125.41 |

Table 2.

Component and final binding free energies. Values are for full annihilation of guest nonbonded interactions in aqueous solvation and bound to “indent” and “overlap” conformations of the TrimerTrip host. The binding energy is the difference between the corresponding solvated and bound series. Units are kcal/mol. Values for the bound series include corrections to account for restraint of the guest within the host binding site during the simulations. Adamantyl ligands G6, G9 and G11 bind weakly or not at all to the indent conformer, and are not reported. Statistical errors for the ΔGbind values were computed by performing bootstrap analysis on the BAR free energy from each perturbation window in both the solvated and bound series, and summing the errors over all windows. For all guests, this summed statistical error falls within the range from 0.26 to 0.34 kcal/mol.

| Guest | Solvated Series | Bound Series (Indent) | Bound Series (Overlap) | AG bind (Indent) | AG bind (Overlap) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gl | −77.67 | −83.63 | −82.17 | −5.96 | −4.49 |

| G2 | −69.44 | −78.71 | −76.30 | −9.26 | −6.85 |

| G3 | −64.34 | −74.83 | −73.56 | −10.49 | −9.22 |

| G5 | −56.65 | −66.80 | −66.93 | −10.16 | −10.28 |

| G6 | −64.71 | — | 56.40 | — | −8.31 |

| G7 | −48.47 | −49.04 | −52.85 | −0.57 | −4.37 |

| G8 | −92.04 | −98.13 | −99.64 | −6.09 | −7.60 |

| G9 | 21.96 | — | 17.01 | — | −4.94 |

| G10 | 20.74 | 13.78 | 11.85 | −7.13 | −8.89 |

| Gil | 14.04 | — | 6.93 | — | −7.10 |

| G12 | 24.71 | 15.21 | 15.50 | −9.50 | −9.20 |

| G15 | 33.52 | 21.78 | 21.53 | −11.74 | −12.00 |

| G16 | −49.25 | −59.70 | −59.80 | −10.45 | −10.55 |

| G17 | −43.25 | −52.68 | −52.77 | −9.42 | −9.51 |

| G18 | −31.83 | −38.78 | −45.03 | −6.96 | −13.21 |

| G19 | 40.73 | 33.66 | 28.23 | −8.08 | −12.51 |

Gas phase and implicit solvent [55] optimization of TrimerTrip (Figure 1) using the AMOEBA force field tends to minimize electrostatic repulsion between the four sulfonate groups by generating extended, unfolded structures that are flattened relative to solution structures for cucurbiturils and cucurbituril-derived clips. Solvation followed by MD simulation of these gas phase structures leads to rapid folding within several nanoseconds, resulting most commonly in the “indent” structure shown in Figure 2(c–d). Three structural families appear to predominate in solution (Figure 2), which we will refer to as the “open” (Figure 2a–b), “indent” (Figure 2c–d) and “overlap” (Figure 2e–d) conformations of TrimerTrip. Additional periodic boundary MD simulations in aqueous solution of at least 50 ns were started from members of each the three families. All three structures were stable under MD simulation, and interconversion between structures was not observed. The “indent” structure is most similar to the TrimerTrip conformer provided by the SAMPL7 organizers, while the “overlap” structure resembles the x-ray crystal structure of a similar host analog containing a fourth central CB unit. [56]

Inspection of the observed TrimerTrip conformers suggests the 7-membered rings immediately adjacent to the triptycene groups are key determinants of overall structure. We performed a full conformational search for the molecule shown in Figure 3(a), as a model for the 7-ring of TrimerTrip. Only two local structures were identified as local minima on the MP2/6–311G(1d,1p) potential surface. The mirror symmetric global minimum structure is shown in Figure 3(b–c), and it is 0.6 kcal/mol lower in energy than the slightly twisted minimum shown in Figure 3(d–e). The “overlap” TrimerTrip conformer has both 7-rings in the global minimum conformation, while the “open” TrimerTrip has two copies of the higher energy 7-ring, and the “indent” structure has one of each of the 7-membered ring motifs. The symmetric 7-membered ring structure facilitates the stacked phenyl ring overlap in the “overlap” conformer, as seen in figure 2(e–f). On the other hand, both the “open” and “indent” TrimerTrip conformers have an overall twist in keeping with the alternative 7-ring model conformation. The transition state for the model compound interconversion was also determined at the same ab initio level of theory, and lies 6.6 kcal/mol above the global minimum. Assuming the interconversion barrier to be largely enthalpic, this suggests a mean first passage time from the model global minimum basin of at least 10 ns. Given the additional favorable stacking and T-shape π−π interactions in the full TrimerTrip structures, the actual interconversion barrier between “indent” and “overlap” forms of TrimerTrip is likely even larger than for the model compound. Given the lack of interconversion of TrimerTrip structures on an MD time scale accessible via our windowed free energy simulations, the three host conformations were treated separately, and binding results for the separate conformers were combined.

Both the “indent” and “overlap” host conformations form enclosed pockets potentially suitable for guest binding, with the “overlap” structure having the somewhat larger and more flexible cavity. The “open” conformation does not provide a defined binding cavity and was not considered further. We attempted to compute the binding of all 16 guests to both of these host conformers. For each of the bound combinations, the guest was inserted into the binding cavity, energy minimized, and subjected to a 50 ns unrestrained MD simulation. A single distance restraint was selected to tether the guest inside the binding cavity such that the corresponding flat-bottom restraint was not violated during the unrestrained dynamics calculation. A series of window simulations of 10 ns each were then run at λ values that first annihilated guest electrostatic interactions, followed by annihilation of vdW interactions. Based on our results from SAMPL6, annihilation of vdW interactions was chosen over a decoupling protocol that would retain intra-guest interactions. [57] As described under Methodology, an analytical correction was made to the total guest annihilation free energy to account for removal of the restraint in the fully annihilated state. Since the binding restraint is not violated during unrestrained simulation, no free energy change is associated with turning on the restraint in the initial bound state. The total free energy of the bound annihilation series for each guest with the “indent” and “overlap” hosts, including the analytical correction, is given in Table 2.

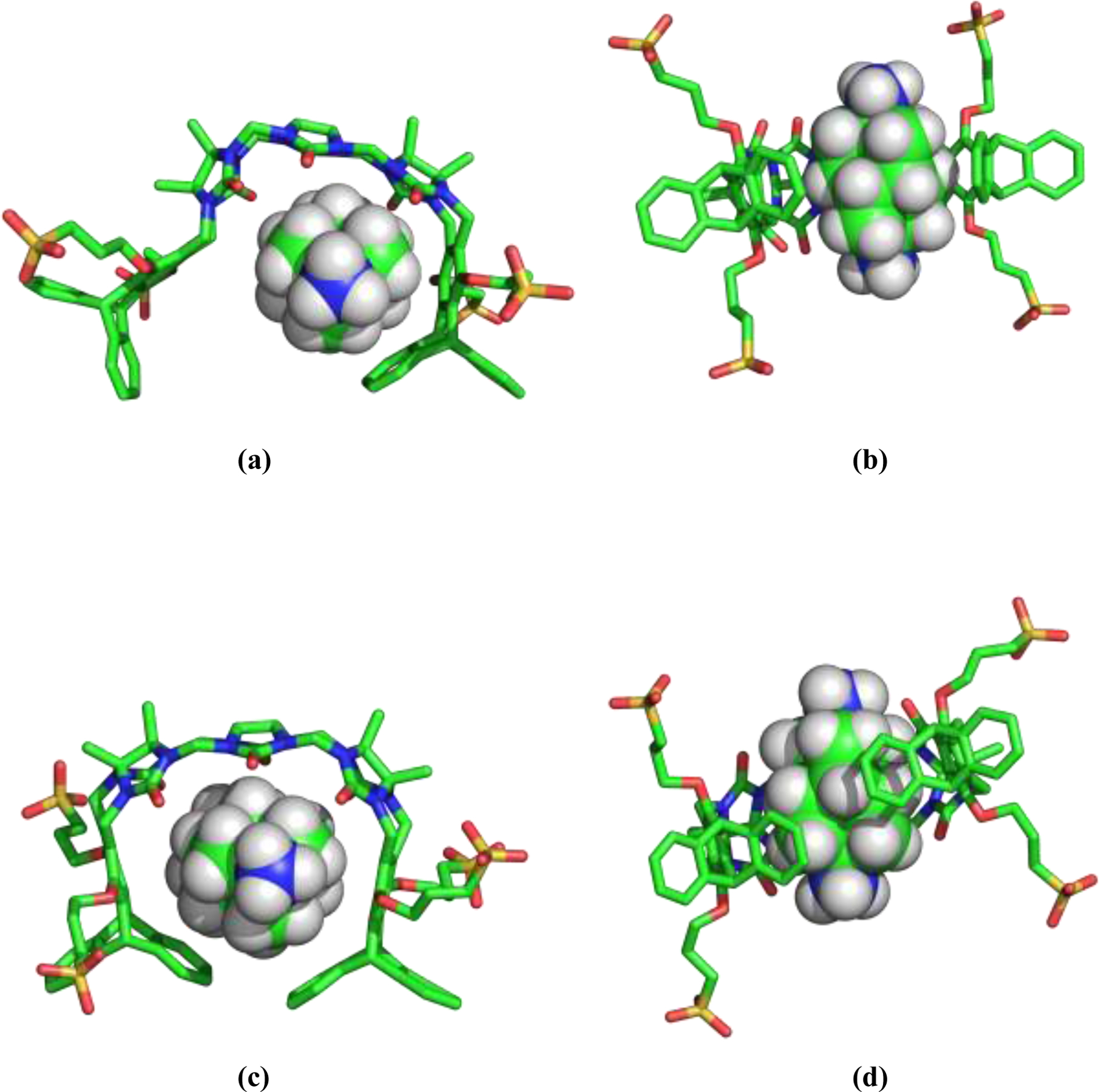

Given the simulation results for the solvated simulation series, as well as the bound series in the “indent” and “overlap” host conformations, we computed the binding of each guest to both of the host conformers by simple difference. The results are presented in the last two columns of Table 2 as ΔGbind (indent) and ΔGbind (overlap). Figures 5 and 6 provide snapshots from unrestrained MD trajectories of G2 and G10 bound to both the “indent” and “overlap” hosts. Both of these guests are alkyl ammonium species, are dications at the experimental pH of 7.4, and have nearly identical distances between their ammonium nitrogen atoms (7.6 Å for G2 vs. 7.7 Å for G10). They differ mostly in the width and volume occupied by the hydrocarbon region between the cationic groups. The total contact-reentrant molecular volume with a probe radius of 1.4 Å is 245 Å3 for G10, which is 78% greater than the 138 Å3 volume for G2. From Figure 5, it is seen that G2 fits nicely into the binding cavity of the “indent” host conformer, with very little distortion of the unligated host structure depicted in Figure 2(c–d). In the G2-overlap complex, the triptycene phenyl rings packed against the guest splay apart, forming an overall chiral, spiral host structure. This spiral host shape was observed for many guests, and may result from an attempt by the host to sequester guest hydrophobic surface area and to form π-cation interactions with ammonium groups. The spiral structure is dynamic, and the position of the phenyl rings interchange resulting in enantiomeric spiral conformations several times during a 10 ns simulation. These interchange events proceed via a structure that retains the “overlap” form, but with the rings separated sufficiently to slip past each other. From the binding results in Table 2, G2 binds more tightly to the “indent” host by 2.4 kcal/mol. The opposite behavior is found for G10, which binds more tightly to the “overlap” structure by 1.8 kcal/mol. In the G10 case, the guest greatly distorts the “indent” pose, leading to loss of contact between the phenyl rings on opposite ends of TrimerTrip as in Figure 6(a–b). G10 binding expands the “overlap” host structure as in Figure 6(e–f), but both terminal phenyl rings remain packed against the guest. The data in Table 2 strongly suggests consideration of both host conformations is mandatory to quantitatively account for binding of the various guests.

Figure 5.

Snapshots from an unrestrained MD simulation, showing G2 bound the TrimerTrip host. The upper panels (a-b) show binding to the “indent” host conformation, while the lower panels (c-d) are a typical pose of the guest bound to the “overlap” host conformation. Note the offset of the distal aromatic rings in (d), compared to the analogous unligated host conformation shown in figure 2(f).

Figure 6.

Snapshots from an unrestrained MD simulation, showing G10 bound the TrimerTrip host. The upper panels (a-b) show binding to the “indent” host conformation, while the lower panels (c-d) are a typical pose of the guest bound to the “overlap” host conformation. Note the expansion of the host cavity necessary to bind the wider G10 guest, relative to the structures shown in figures 2 and 5.

In order to determine an overall binding free energy for comparison against experiment, weights were assigned to the binding of guest to the two host structures. This in turn requires an estimate of the free energy difference between the unligated “indent” and “overlap” forms in solution. Given this value, the relative free energy of all four relevant states was set, i.e., bound and unbound guest with the “indent” and “overlap” hosts. A simple four-state partition function then provides a correct estimate of the overall free energy difference between free and bound guest.

Two methods were used to estimate the “indent” vs. “overlap” free energy difference. Due to time constraints near the SAMPL7 submission deadline, the solvation energy of the two separate host conformations was computed, including all intra-host interactions. This resulted in a free energy difference of 2.84 kcal/mol favoring the “indent” conformation, and this value was used as our ranked submission for SAMPL7 as shown in Table 3. However, large hysteresis in multiple free energy windows rendered this value uncertain. Thus, we submitted two “unranked” prediction sets, one assuming the “overlap” conformer to be lower in free energy by roughly 2.5 kcal/mol, and another assuming “indent” and “overlap” to be equal in free energy. Our ranked and two unranked submissions prior to the SAMPL7 deadline correspond to submission IDs 6, 8 and 9, respectively, to the SAMPL7 challenge as archived on Github at https://github.com/samplchallenges/SAMPL7/.

Table 3.

Initial “ranked” and final “revised” TrimerTrip host-guest binding free energies compared to the experimental values. Units are kcal/mol. The standard statistical error for the “revised” binding energies is the umbrella sampling error estimate of 0.42 kcal/mol added to the ΔGbind errors of 0.26–0.34 kcal/mol from table 2, resulting in total statistical errors for each guest of between 0.68 and 0.76 kcal/mol.

| Guest | Ranked | Revised | Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gl | −5.96 | −4.85 | −6.10 |

| G2 | −9.26 | −8.15 | −8.32 |

| G3 | −10.49 | −9.38 | −10.05 |

| G5 | −10.16 | −10.28 | −11.10 |

| G6 | −5.47 | −8.31 | −9.60 |

| G7 | −1.51 | −4.37 | −6.50 |

| G8 | −6.09 | −7.60 | −9.45 |

| G9 | −2.10 | −4.94 | −7.57 |

| G10 | −7.13 | −8.89 | −8.17 |

| Gl1 | −4.26 | −7.10 | −9.02 |

| Gl2 | −9.50 | −9.20 | −8.29 |

| Gl5 | −11.74 | −12.00 | −10.52 |

| Gl6 | −10.45 | −10.55 | −11.50 |

| Gl7 | −9.42 | −9.51 | −11.80 |

| Gl8 | −10.37 | −13.21 | −10.55 |

| Gl9 | −9.67 | −12.51 | −11.70 |

| MUE | 2.14 | 1.41 | |

| RMSE | 2.77 | 1.59 | |

| Pearson R | 0.704 | 0.832 | |

| Kendall τ | 0.43 | 0.65 | |

Subsequent to closure of the SAMPL7 challenge, we employed a much better behaved and more rigorous series of umbrella sampling simulations to determine the “indent” vs. “overlap” free energy separation. Starting from the unrestrained “indent” structure, a set of 55 restrained simulations were used to slowly convert the conformation to the “overlap” form. A smooth interconversion pathway was constructed using torsional restraints on one of the two 7-membered TrimerTrip rings, as well as the midpoint distance between two spatially close phenyl ring C–C bonds in the “overlap” form. The overall path is illustrated in Figure 7, and resulted in a free energy favoring the “overlap” structure by 1.11 kcal/mol, near the average of our two “unranked” predictions submitted for SAMPL7. The statistical error between adjacent simulations along the umbrella sampling path was estimated by bootstrap analysis of the BAR results. The total umbrella sampling error estimated by adding individual errors across all windows is 0.42 kcal/mol. Guest binding values based upon the umbrella sampling result are given in Table 3 as the “revised” column. Note the guest binding simulation results summarized in Table 2 are unchanged between the “ranked” and “revised” estimates, and the only difference is in the relative energies of the unligated “indent” and “overlap” host states.

Figure 7.

An outline of the umbrella sampling protocol used to compute the free energy difference between the unligated “indent” and “overlap” conformations of the TrimerTrip host in solution. An estimate of this energy difference is needed to set overall host-guest binding free energies given the computed binding of each guest to the separate “indent” and “overlap” conformers.

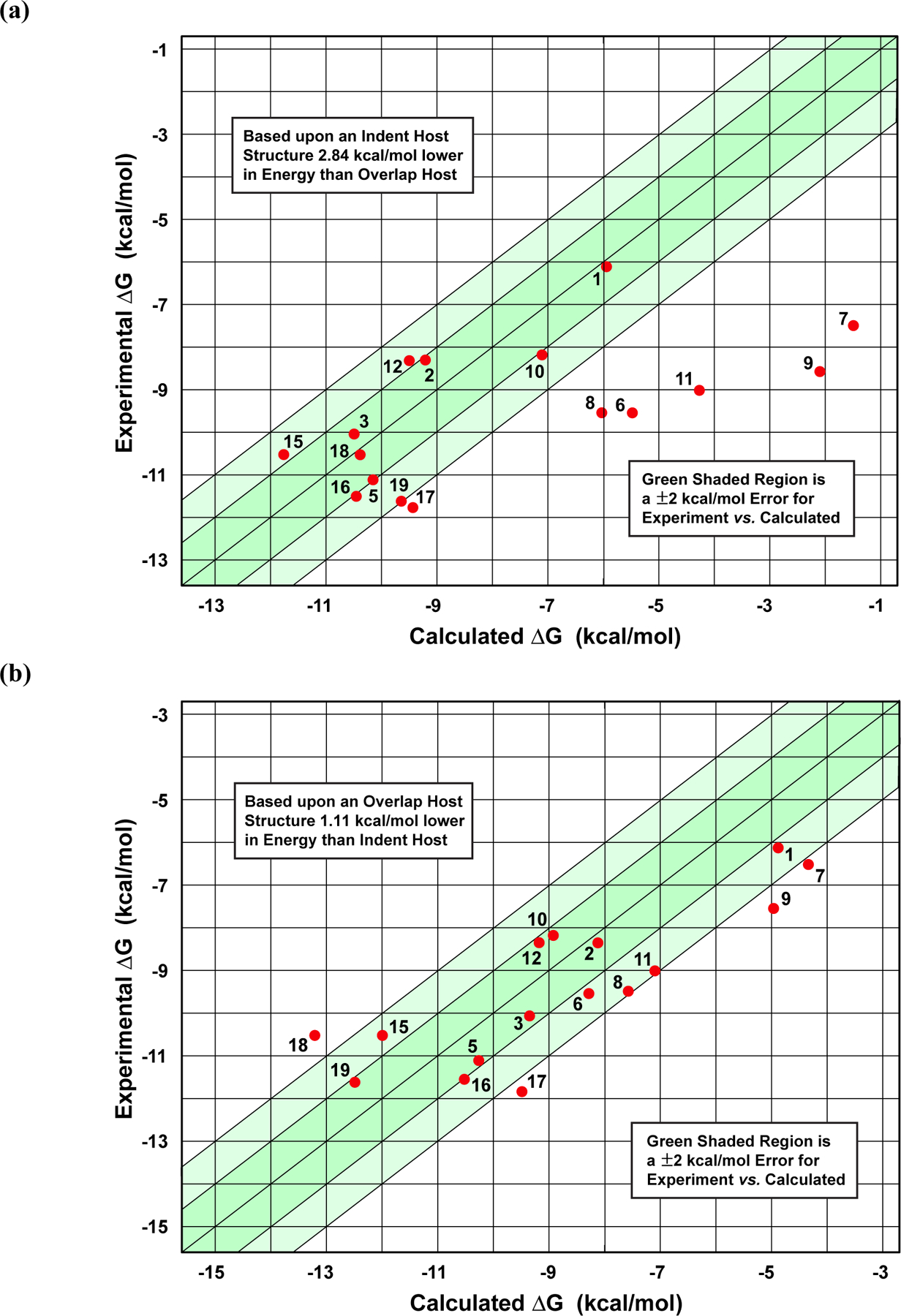

Plots of our “ranked” and “revised” free energy predictions vs. experimental values are shown in the upper and lower panels of Figure 8, respectively. The “ranked” predictions exhibit a mean unsigned error (MUE) of 2.14 kcal/mol and a Pearson correlation coefficient (R) of 0.703. However, there is a clear trend for the larger guests, including all of the adamantyl compounds, being calculated as under bound. This is due to the overestimation of the stability of the “indent” host conformation, and resulting underweighting of guest binding to the “overlap” form. Larger ligands, in particular, bind more tightly to the “overlap” host than to the “indent” host.

Figure 8.

(a) Plot of the initially submitted “ranked” AMOEBA predictions for the host-guest binding free energies. Binding values in (a) correspond to our initial estimate of the unligated host having a lower free energy by 2.84 kcal/mol in the “indent” conformation. (b) A plot of the revised AMOEBA results for the TrimerTrip. Binding values in (b) correspond to the unligated host preferring the “overlap” conformation by 1.11 kcal/mol as determined by umbrella sampling. The darker and lighter shaded green regions represent deviations within 1 and 2 kcal/mol from experiment, respectively.

Our “revised” binding free energy predictions based on the more reliable umbrella sampling reference, produce the calculated vs. experimental plot shown in Figure 8(b). These results are much better balanced and lie substantially closer to experiment than the “ranked” set. The MUE is reduced to 1.41 kcal/mol. The revised predictions for twelve of the 16 guests are now within 2.0 kcal/mol of experiment, and the remaining four guests fall only slightly outside the +/− 2 kcal/mol target. The correlation coefficient is 0.832, and the pairwise rank correlation (Kendall τ value) is high at 0.65. As a point of interest, we note that our unranked submission assuming the two unligated host conformations are equal in free energy provided nearly identical statistics, with a very slightly improved MUE of 1.39 kcal/mol. Generally, any unligated host energy difference from roughly zero to favoring “overlap” by a modest amount provides similar overall binding results, as can be verified by inspection of the data in table 2.

The treatment of finite size and salt effects in free energy simulations of charged systems is a topic of ongoing discussion in the literature, especially surrounding the use of Ewald summation techniques. [58–62] In order to explore the importance of this issue for the current system, a set of computational experiments were performed for G15 bound to the “overlap” TrimerTrip host. Four different buffer conditions were simulated. For our standard protocol, as described above, four sodium ions were added to the host-guest complex to neutralize the host, and no ions were added to attempt to neutralize the guest during double annihilation. In a second set of “neutral” conditions, two additional chloride ions were added to neutralize the G15 guest in both the guest and host-guest systems, and these additional ions were annihilated along with the guest. This procedure keeps the overall system neutral across all free energy simulation windows. A third free energy calculation was performed while approximating 50 mM NaCl via further addition of four sodium ions and four chloride ions beyond the standard conditions. Finally, a fourth series of calculations were run with no added ions in order to test a “no salt” condition. All of these simulations agreed to within 1 kcal/mol with the following binding values: −12.00 kcal/mol (standard protocol), −12.98 kcal/mol (neutral), −12.44 kcal/mol (50 mM salt) and −12.87 kcal/mol (no salt). The effect of varying the binding cavity restraint force constant was tested for G15 by doubling from 15 kcal/mol/Å2 to a value of 30, and maintaining the standard ion protocol. The resulting free energy was −12.34 kcal/mol, within the standard error. Further calculations are needed to clarify whether these relatively small differences are statistically significant for TrimerTrip-G15, and are beyond the scope of the work presented here. While it appears treatment of charges, small numbers of added ions, and variation in cavity restraints have at most a modest effect on TrimerTrip binding, this conclusion may not extend to other host-guest systems or protein-drug interactions.

AMOEBA free energy calculations between sampling windows provide a bootstrap error estimate associated with the BAR procedure. The error for pairs of adjacent windows must be summed over entire solvated or bound simulation series, and those values are summed again when taking the final difference between free energy series. For the gas phase vs. aqueous solvation free energies listed in Table 1, the overall error is in the range from 0.15 to 0.25 kcal/mol. For host-guest binding energies reported in Tables 2 and 3, the statistical standard error is approximately 0.4 kcal/mol and is similar across all guests. In addition, we have previously performed multiple binding free energy evaluations for similar complexes, and the variability in the final binding free energy values suggested an inherent statistical error of roughly 0.25 kcal/mol.

Conclusions

One of the major advantages of a polarizable potential energy model is its ability to account for the different environments to which a molecule is exposed. This arises in at least two ways that are relevant to host-guest complex formation in aqueous solution. First, the guest is in a different environment in high dielectric water vs. packed against aromayic rings inside the TrimerTrip cavity. Second, water molecules inside the unligated host are freed upon guest binding, and this favorable desolvation process can be difficult to model generally with a nonpolarizable water model. The first of these effects will tend to result in inaccurate binding values for individual guests, while the desolvation issue can result in a systematic offset error in binding observed with fixed charge force fields. Our “revised” AMOEBA model, using a correct estimate of the unligated host free energy difference, provides binding equilibria within about one log unit, which may improve with further iterations of the force field currently under development. [63] [64] The best fit line for the data shown in Figure 8(b) is ΔGcalc = 1.228 × ΔGexpt + 2.724. Both the slope and intercept values are indicative of a moderate over binding of tight binders, and corresponding under binding of weaker ligands. However, the fact that most guests fall within 2 kcal/mol of experiment across a fairly broad range of binding values, discounts a large systematic error. Considering the current AMOEBA results combined with those from prior SAMPL host-guest exercises, there is little overall evidence of any systematic bias. [57,65]

Our results also illustrate the importance of careful consideration of the conformational analysis of both partners in a binding event. While a fully automated binding free energy protocol is an ultimate goal of exercises like the SAMPL7 challenge, simple special case structural considerations can greatly simplify a modeling problem. For example, the relatively high barrier between the “indent” and “overlap” TrimerTrip structures poses a serious sampling obstacle if one insists on sampling them together. However, conformational problems are not always as easily separable as in this case, and sampling remains a limitation for many flexible systems.

Blind challenges, such as SAMPL7, present an outstanding opportunity to test and compare energy models and sampling technologies, and to learn ways to improve these approaches in order to advance the field. Data presented in this report suggests our standard protocol can provides reasonable binding results for small host-guest complexes without use of advanced sampling methods beyond canonical MD simulation. Future work will include an examination of enhanced sampling, such a Hamiltonian replica exchange [66] [67] and orthogonal space random walk methods, [68] [65] in application of the AMOEBA model to larger protein-ligand complexes.

Based on our experience in the SAMPL7 TrimerTrip host-guest challenge, the AMOEBA model combined with a straightforward double annihilation scheme yields near chemical accuracy for binding free energies for this system. Although AMOEBA calculations are slower than traditional fixed partial charge biomolecular force fields, modern GPU technology allows individual host-guest absolute binding energies such as those reported here to be obtained within several hours. Significant progress has been reported by many groups across the continuing series of SAMPL challenges, and there is great promise that approaches like those described here will contribute to the future of computer-aided drug design.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the organizers and experimentalists involved with the SAMPL7 challenge for providing an interesting and challenging exercise. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Chris Ho for help with automating AMOEBA parameter generation for the guest molecules. JWP wishes to thank the National Institutes of Health NIGMS for financial support via awards R01 GM106137 and R01 GM114237.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Kim K, Scherman O, Macartney D, Dearden D, Tao Z, MAsson E, Keinan E, Nau W, Jonkheijm P, Day A, Kaifer A, Brunsveld L, Isaacs L, Sindelar V (2020) Cucurbiturils and Related Macrocycles Kim K ed. Royal Society of Chemistry, [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrow SJ, Kasera S, Rowland MJ, del Barrio J, Scherman OA (2015) Cucurbituril-Bassed Molecular Recognition Chem Rev 115:12320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganapati S, Grabitz SD, Murkli S, Scheffenbichler F, Rudolph MI, Zavalij PY, Elkermann M, Isaacs L (2017) Molecular Containers Bind Drugs of Abuse in Vitro and Reverse the Hyperlocomotive Effect of Methamphetamine in Rats ChemBioChem 18:1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abel R, Wang L, Harder ED, Berne BJ, Friesner RA (2017) Advancing Drug Discovery through Enhanced Free Energy Calculations Accounts Chem Res 50:1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams-Noonan BJ, Yuriev E, Chalmers DK (2018) Free Energy Methods in Drug Design: Prospects of “Alchemical Perturbation” in Medicinal Chemistry J Med Chem 61:638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mobley DL, Klimovich PV (2012) Perspective: Alchemical Free Energy Calculations for Drug Discovery J Chem Phys 137:230901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cabeza de Vaca I, Qian Y, Vllseck JZ, Tirado-Rives J, Jorgensen WL (2018) Enhanced Monte Carlo Methods for Modeling Proteins Including Computation of Absolute Free Energies of Binding J Chem Theory Comput 14:3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng N, Cui D, Zhang BW, Xia J, Cruz J, Levy R (2018) Comparing Alchemical and Physical Pathway Methods for Computing the Absolute Binding Free Energy of Charged Ligands Phys Chem Chem Phys 20:17081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aldeghi M, Bluck JP, Biggin PC (2018) Absolute Alchemical Free Energy Calculations for LIgand Binding: A Beginner’s Guide Method Mol Biol 1762:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellett K, Duggan BM, Gilson MK (2019) Facile Synthesis of a Diverse Library of Mono-3-Substituted Cyclodextrim Analogues Supramol Chem 31:251 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suating P, Nguyen TN, Ernst NE, Wang Y, Jordan JH, Gibb CLD, Ashbaugh HS, Gibb BC (2020) Proximal Charge Effects on Guest Binding to a Non-Polar Pocket Chem Sci 11:3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ndendjio SZ, Liu W, Yvanez N, Meng Z, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L (2020) Triptycene Walled Glycouril Trimer: Synthesis and Recognition Properties New J Chem 44:338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muddana HS, Fenley AT, Mobley DL, Gilson MK (2014) The SAMPL4 Host-Guest Blind Prediction Challenge: An Overview J Comput Aided Mol Des 28:305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muddana HS, Varnado CD, Bielawski CW, Urbach AR, Isaacs L, Geballe MT, Gilson MK (2012) Blind Prediction of Host-Guest Binding AffinitiesL A New SAMPL3 Challenge J Comput Aided Mol Des 26:475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murkli S, McNeil JN, Isaacs L (2019) Cucurbit[8]uril-Guest Complexes: Blinded Dataset for the SAMPL6 Challenge Supramol Chem 31:150 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin J, Henriksen NM, Slochower DR, Shirts MR, Chiu MW, Mobley DL (2017) Overview of the SAMPL5 Host-Guest Challenge: Are We Doing Better? J Comput Aided Mol Des 31:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.She N, Moncelet D, Gilberg L, Lu X, Sindelar V, Briken V, Isaacs L (2016) Glycoluril-Derived Molecular Clips are Potent and Selective Receptors for Cationic Dyes in Water Chem-Eur J 22:15270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornell WD, Cieplak P, Bayly CI, Gould IR, Merz KM, Ferguson DM, Spellmeyer DC, Fox T, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA (1995) A Second Generation Force Field for the Simulation of Proteins, Nucleic Acids, and Organic Molecules J Am Chem Soc 117:5179 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanommeslaeghe K, Hatcher E, Acharya C, Kundu S, Zhong S, Shim J, Darian E, Guvench O, Lopes P, Vorobyov I, MacKerell AD (2010) CHARMM General Force Field: A Force Field for Drug-like Molecules Compatible with the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Biological Force Fields J Comput Chem 31:671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson MJ, Tirado-Rives J, Jorgensen WL (2015) Improved Peptide and Protein Torsional Energetics with the OPLSAA Force Field J Chem Theory Comput 11:3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ponder JW, Wu C, Ren P, Pande VS, Chodera JD, Mobley DL, Schnieders MJ, Haque I, Lambrecht DS, DiStasio J, R. A, Head-Gordon M, Clark GNI, Johnson ME, Head-Gordon T (2010) Current Status of the AMOEBA Polarizable Force Field J Phys Chem B 114:2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laury ML, Wang L-P, Pande VS, Head-Gordon T, Ponder JW (2015) Revised Parameters for the AMOEBA Polarizable Atomic Multipole Water Model J Phys Chem B 119:9423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren P, Ponder JW (2003) Polarizable Atomic Multipole Water Model for Molecular Mechanics Simulation J Phys Chem B 107:5933 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren P, Wu C, Ponder JW (2011) Polarizable Atomic Multipole-based Molecular Mechanics for Organic Molecules J Chem Theory Comput 7:3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi Y, Xia Z, Zhang J, Best R, Wu C, Ponder JW, Ren P (2013) Polarizable Atomic Multipole-Based AMOEBA Force Field for Proteins J Chem Theory Comput 9:4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiang JY, Ponder JW (2014) An Angular Overlap Model for Cu(II) Ion in the AMOEBA Polarizable Force Field J Chem Theory Comput 10:298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang C, Lu C, Jing Z, Wu C, Piquemal J-P, Ponder JW, Ren P (2018) AMOEBA Polarizable Atomic Multpole Force Field for Nucleic Acids J Chem Theory Comput 14:2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiao D, Golubkov PA, Darden TA, Ren P (2008) Calculation of Protein-Ligand Binding Free Energy by Using a Polarizable Potential Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 105:6290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q, Edupuganti R, Tavares CDJ, Dalby KN, Ren P (2015) Using Docking and Alchemical Free Energy Approach to Determine the Binding Mechanism of eEF2K Inhibitors and Prioritizing the Compound Synthesis Front Mol Biosci 2:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qi R, Walker B, Jing Z, Yu M, Stancu G, Edupuganti R, Dalby KN, Ren P (2019) Computational and Experimental Studies of Inhibitor Design for Aldolase A J Phys Chem B 123:6034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rackers JA, Wang Z, Lu C, Laury ML, Lagardere L, Schnieders MJ, Piquemal J-P, Ren P, Ponder JW (2018) Tinker 8: Software Tools for Molecular Design J Chem Theory Comput 14:5273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harger M, Li D, Wang Z, Dalby K, Lagardere L, Piquemal J-P, Ponder JW, Ren P (2017) Tinker-OpenMM: Absolute and Relative Alchemical Free Energies Using AMOEBA on GPUs J Comput Chem 38:2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith DGA, Burns LA, Simmonett AC, Parrish RM, Schieber MC, Galvelis R, Kraus P, Kruse H, Di Remigio R, Alenaizan A, James AM, Lehtola S, Misiewicz JP, Scheurer M, Shaw RA, Schriber JB, Xie Y, Glick ZL, Sirianni DA, O’Brien JS, Waldrop JM, Kumar A, Hohenstein EG, Pritchard BP, Brooks BR, Schaefer III HF, Sokolov AY, Patkowski K, DePrince III AE, Bozkaya U, King RA, Evangelista FA, Turney JM, Crawford TD, Sherrill CD (2020) Psi4 1.4: Open-Source Software for High-Throughput Quantum Chemistry J Chem Phys 152:184108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stone AJ (1981) Distributed Multipole Analysis, or How to Describe a Molecular Charge Distribution Chem Phys Lett 83:233 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stone AJ, Alderton M (2002) Distributed Multipole Analysis: Methods and Applications Mol Phys 100:221 [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Duijnen PT, Swart MJ (1998) Molecular and Atomic Polarizabilities: Thole’s Model Revisited J Phys Chem A 102:2399 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thole BT (1981) Molecular Polarizabilities Calculated with a Modified Dipole Interaction Chem Phys 59:341 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halgren TA (1995) Merck Molecular Force Field. I. Basis, Form, Scope, Parameterization, and Performance of MMFF94 J Comput Chem 17:490 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halgren TA (1995) Merck Molecular Force Field. II. MMFF94 van der Waals and Electrostatic Parameters for Intermolecular Interactions J Comput Chem 17:520 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Halgren TA (1995) Merck Molecular Force Field. III. Molecular Geometries and Vibrational Frequencies for MMFF94 J Comput Chem 17:553 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halgren TA (1995) Merck Molecular Force FIeld. V. Extension of MMFF94 Using Experimental Data Additional Computational Data J Comput Chem 17:616 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Halgren TA, Nachbar RB (1995) Merck Molecular Force Field. IV. Conformational Energies and Geometries for MMFF94 J Comput Chem 17:587 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tuckerman ME, Berne BJ (1991) Molecular Dynamics in Systems with Multiple Time Scales: Systems with Stiff and Soft Degrees of Freedom and with Short and Long Range Forces J Chem Phys 95:8362 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tuckerman ME, Berne BJ (1992) Reversible Multiple Time Scale Molecular Dynamics J Chem Phys 97:1990 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuckerman ME, Berne BJ, Rossi A (1990) Molecullar Dynamics Algorithm for Multiple Time Scales: Systems with Disparate Masses J Chem Phys 94:1465 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bussi G, Donadio D, Parrinello M (2007) Canonical Sampling Through Velocity-Rescaling J Chem Phys 126:014101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bussi G, Parrinello M (2008) Stochastic Thermostats: Comparison of Local and Global Schemes Computer Physics Communications 179:26 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bussi G, Zykova-Timan T, Parrinello M (2009) Isothermal-Isobaric Molecular Dynamics Using Stochastic Velocity Rescaling J Chem Phys 130:074101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frenkel D, Smit B (2001) Understanding Molecular Simulation: From Algorithms to Applications, 2nd Ed. Academic Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faller R, de Pablo JJ (2002) Constant Pressure Hybrid Molecular Dynamics-Monte Carlo Simulations J Chem Phys 116:55 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zwanzig RW (1954) High-Temperature Equation of State by a Perturbation Method. I. Nonpolar Gases J Chem Phys 22:1420 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bennett CH (1976) Efficient Esimation of Free Energy Differences from Monte Carlo Data J Comput Phys 22:245 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamelberg D, McCammon JA (2004) Standard Free Energy of Releasing a Localized Water Molecule from the Binding Pockets of Proteins: Double-Decoupling Method J Am Chem Soc 126:7683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zheng X, Wu C, Ponder JW, Marshall GR (2012) Molecular Dynamics of β-Hairpin Models of Epigenetic Recognition Motifs J Am Chem Soc 134:15970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schnieders MJ, Ponder JW (2007) Polarizable Atomic Multipole Solutes in a Generalized Kirkwood Continuum J Chem Theory Comput 3:2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu X, Samanta SK, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L (2018) Blurring the Lines between Host and Guest: A Chimeric Receptor Derived from Cucurbituril and Triptycene Angew Chem Int Edit 57:8073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laury ML, Gordon AS, Ponder JW (2018) Absolute Binding Free Energies for the SAMPL6 Cucurbit[8]uril Host-Guest Challenge via the AMOEBA Polarizable Force Field J Comput Aided Mol Des 32:1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bogusz S, Cheatham III TE, Brooks BR (1998) Removal of Pressure and Free Energy Artifacts in Charged Periodic Systems via Net Charge Corrections to the Ewald Potential J Chem Phys 108:7070 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rocklin GJ, Mobley DL, Dill KA, Hunenberger PH (2013) Calculating the Binding Free Energies of Charged Species Based on Explicit-Solvent Simulations Employing Lattice-Sum Methods: An Accurate Correction Scheme for Electrostatic Finite-Size Effects J Chem Phys 139:184103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roux B, Simonson T (2016) Concepts and Protocols for Electrostatic Free Energies Mol Simulat 42:1090 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin Y-L, Aleksandrov A, Simonson T, Roux B (2014) An Overview of Electrostatic Free Energy Computations for Solutions and Proteins J Chem Theory Comput 10:2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen W, Deng Y, Russell E, Wu Y, Abel R, Wang L (2018) Accurate Calculation of Relative Binding Free Energies between Ligands with Different Net Charges J Chem Theory Comput 14:6346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu C, Piquemal J-P, Ren P (2020) Implementation of Geometry-Dependent Charge flux into the Polarizable AMOEBA+ Potential J Phys Chem Lett 11:419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rackers JA, Ponder JW (2019) Classical Pauli Repulsion: An Ansiotropic Multipole Model J Chem Phys 150:084104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bell DR, Qi R, Jing Z, Xiang JY, Meijas C, Schnieders MJ, Ponder JW, Ren P (2016) Calculating Binding Free Energies of Host-Guest Systems Using the AMOEBA Polarizable Force Field Phys Chem Chem Phys 18:30261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang W, Roux B (2010) Free Energy Perturbation Hamiltonian Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics (FEP/H-REMD) for Absolute Ligand Binding Free Energy Calculations J Chem Theory Comput 6:2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu P, Kim B, Friesner RA, Berne BJ (2005) Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering: A Method for Sampling Biological Systems in Explicit Water Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 102:13749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zheng L, Chen M, Yang W (2008) Random Walk in Orthogonal Space to Achieve Efficient Free-Energy Simulation of Complex Systems Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 105:20227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]