Abstract

Excessive binge alcohol intake is a common drinking pattern in humans, especially during holidays. Cessation of the binge drinking often leads to aberrant withdrawal behaviors, as well as serious heart rhythm abnormalities (clinically diagnosed as Holiday Heart Syndrome (HHS)). In our HHS mouse model with well-characterized binge alcohol withdrawal (BAW)-induced heart phenotypes, BAW leads to anxiety-like behaviors and cognitive impairment. We have previously reported that stress-activated c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase (JNK) plays a causal role in BAW-induced heart phenotypes. In the HHS brain, we found that activation of JNK2 (but not JNK1 and JNK3) in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), but not hippocampus and amygdala, led to anxiety-like behaviors and impaired cognition. DNA methylation mediated by a crucial DNA methylation enzyme, DNA methyltransferase1 (DNMT1), is known to be critical in alcohol-associated behavioral deficits. In HHS mice, JNK2 in the PFC (but not hippocampus and amygdala) causally enhanced total genomic DNA methylation via increased DNMT1 expression, which was regulated by enhanced binding of JNK downstream transcriptional factor c-JUN to the DNMT1 promoter. JNK2-specific inhibition either by an inhibitor JNK2I or JNK2 knockout completely offset c-JUN-regulated DNMT1 upregulation and restored the level of DNA methylation in HHS PFC to the baseline levels seen in sham controls. Strikingly, either JNK2-specific inhibition or genetic JNK2 depletion or DNMT1 inhibition (by an inhibitor 5-Azacytidine) completely abolished BAW-evoked behavioral deficits. In conclusion, our studies revealed a novel mechanism by which JNK2 drives BAW-evoked behavioral deficits through a DNMT1-regulated DNA hypermethylation. JNK2 could be a novel therapeutic target for alcohol withdrawal treatment and/or prevention.

Keywords: Stress kinase JNK2, Binge alcohol withdrawal, Behavioral deficits, DNA methylation, DNA methyltransferase 1, Prefrontal cortex

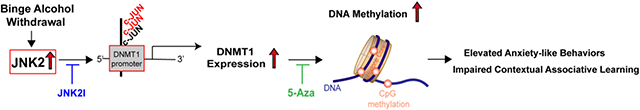

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Excessive binge alcohol drinking is a global medical and economic issue due to its adverse effects on emotional behavior disorders and alcohol-caused organ damage.1-3 In the US, more than one-half of all Americans regularly drink alcohol and about 61 million Americans are binge drinkers.4-6 Despite growing prevention efforts, there is a significantly rising trend in the prevalence of heavy binge drinking.7-9

Heavy binge alcohol drinking and withdrawal during holidays is a common human drinking pattern, which is often followed by withdrawal symptoms including anxiety and cognitive deficit.3,10 Holiday Heart Syndrome (HHS) is another clinically well-recognized serious heart issue caused by holiday binge drinking withdrawal.6,11-15 HHS patients with significant clinical complaints due to serious heart rhythm abnormalities (termed as arrhythmias) often appear in emergency rooms around 12-36 hrs after cessation of several heavy binge alcohol exposure episodes (i.e. when blood alcohol concentration has already returned to baseline levels). Based on the clinical data, our group established a unique HHS mouse model with well-characterized heart phenotype of HHS 24 hrs after the cessation of the last dose of four repetitive binge alcohol-exposures (2 g/kg, I.P. every other day) to mimic a holiday drinking pattern in humans.15 We found that this HHS mouse model exhibits both adverse binge alcohol withdrawal (BAW) behaviors and HHS phenotypes as seen in HHS patients. Thus, the goal of the current study is to understand the underlying mechanisms of BAW-evoked anxiety behaviors in this HHS mouse model.

Increasingly, studies have shown that the stress kinase JNK critically contributes to alcohol-caused organ damage (causing cell death in different organs such as liver and brain).16-18 JNK, an important member of the MAPK family, is a well-characterized kinase that is activated in response to stress stimulations and critically contributes to the development of various forms of disease including cardiovascular diseases, arrhythmias, cancers, and arthritis.19-24 Our group recently reported a previously unrecognized causal role of activation of JNK isoform 2 (JNK2) in enhanced arrhythmogenicity in the heart from both human organ donors and HHS rabbit and mouse models.15,24,25 Accumulating studies suggest that alcohol-activated JNK or reduced JNK exhibits in different regions of the brain (i.e. prefrontal context (PFC) and/or hippocampus) in different rodent models including repeatedly binge alcohol-exposed, chronic alcohol exposure, and alcohol dependent (bottle of choice).18,26-29 As only few studies are available regarding the role of activated JNK in stress-induced anxiety behaviors in stressor challenged rodent models,30,31 the contribution of JNK2 in BAW-evoked anxiety behavioral and cognitive deficit remains completely unknown to date. In the current study, our findings revealed a causal role of JNK2 in the brain (but not other JNK isoforms JNK1 and JNK3),32 in enhanced anxiety-like behaviors and impaired fear learning in HHS mice, evidenced by those adverse behaviors being abolished by either JNK2 specific inhibition or JNK2-specific genetic knockout.

Emerging evidence suggests that JNK in cancer cells may regulate the expression of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1), the most abundant DNA methyltransferase in mammalian cells.33-35 And DNMT1 has been found to modulate DNA methylation in stress-induced anxiety.34,36-38 Thus, the current study investigated whether JNK2 regulates BAW-evoked anxiety and cognition impairment via enhanced DNMT1-mediated DNA methylation. By conducting a series of biochemistry assays, we revealed a JNK2-specific action in increased DNMT1 expression and DNA methylation that leads to BAW-induced behavioral deficits. Our findings suggest that JNK2 inhibition could be a promising therapeutic approach to potentially treat or prevent heavy binge alcohol-evoked psychiatric disorders.

2. Methods (An expanded Methods Section is available in the Supplemental Material)

2.1. Animals, binge alcohol exposure and drug treatment

All animal studies were performed according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication, 8th Edition, 2011) and were approved by the Animal Care Committees of the Rush University Medical Center and University of Illinois at Chicago. The HHS model was generated as previously described15 in C57B/6j wild-type (WT) mice and JNK2 knockout (JNK2KO)25,39 mice (Jackson Laboratory, ME, USA). To inhibit JNK2 and DNMT1, a well-validated JNK2-specific inhibitor JNK2I15,25,40 and DNMT1 inhibitor 5-Azacytidine (5-Aza)61,62 were administrated, respectively, along with the HHS protocol treatment (see more details in Supplemental Materials). Behavioral studies were conducted 24hrs after the last dose of alcohol administration. Six different groups including WT mice (HHS, HHS+JNK2I, sham control, sham-JNK2I) and JNK2KO and JNK2KO HHS mice were sacrificed and brain samples including prefrontal cortex (PFC), hippocampus and amygdala were quickly dissected at day 9 (the day after behavioral tests) as detailed in Fig.1A. Blood alcohol concentration (BAC) was measured as previously described15 and no detectable BAC was found in HHS mice at the time of behavioral studies or sacrifice for tissue collection. Additional details can be found in Supplemental Method.

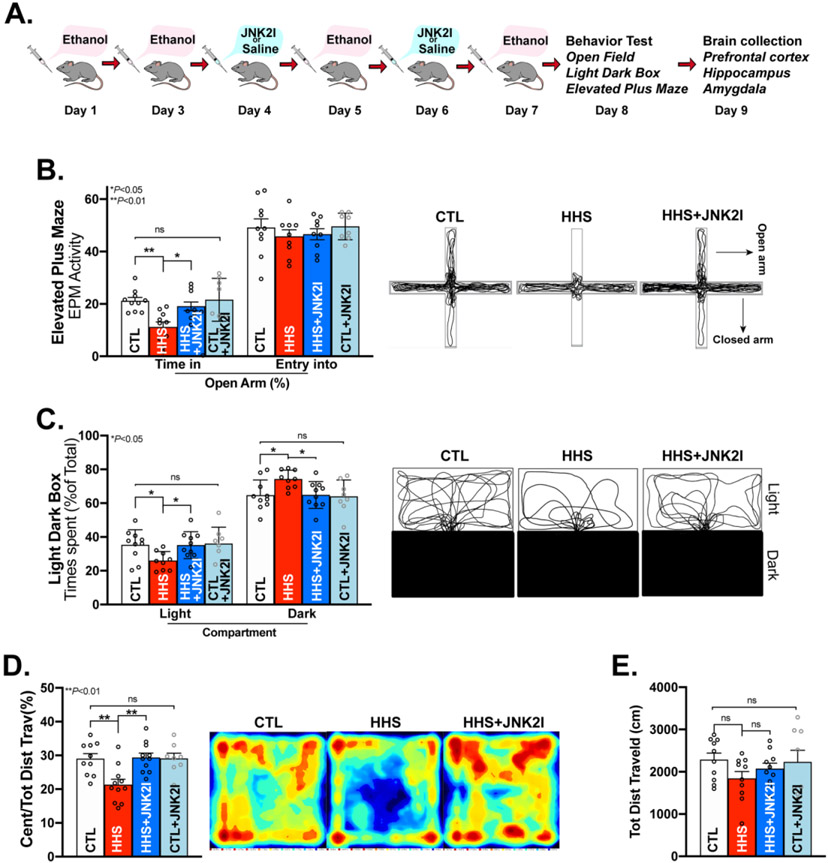

Figure 1.

JNK2 Inhibition Attenuates BAW-evoked Anxiety-like Behaviors in HHS-WT Mice. A) Schematic of the alcohol and JNK2I (JNK2-specific inhibitor) administration protocols; Anxiety-like behaviors were assessed using elevated plus maze (EPM), Light/Dark Box (LDB) and Open Field (OF) behavioral tests in binge alcohol withdrawal mice (BAW; 24hrs after the last dose of the binge alcohol exposures; B) Summarized data and representative traces of EPM tests showing time spent in the open arms (left bars) and number of entries into the open arm in sham control (CTL), HHS-WT (HHS) mice, JNK2I-treated HHS-WT (HHS+JNK2I) mice, JNK2I-treated sham control (CTL+JNK2I) mice (Time spent in the open arms: F3, 34 = 6.362, p<0.01); C) Grouped data and representative traces of LDB tests showing the significant differences of preference for staying in the light compartment or the dark compartment between sham control (CTL), HHS-WT (HHS) mice, JNK2I-treated HHS-WT (HHS+JNK2I) mice, JNK2I-treated sham control (CTL+JNK2I) mice (Time spent in the light compartment: F3,34 = 3.121, p<0.05; Time spent in the dark compartment: F3,34 =3.215, p<0.05); D) Summarized data (left panel) and representative heat maps of moving activities (right panel) from OF tests in vehicle-treated HHS-WT (HHS) mice and JNK2I-treated HHS (HHS+JNKI) mice (F3,34 =6.253, p<0.01); E) Grouped data showing unchanged locomotor activities in HHS-WT mice with and without JNK2 inhibitor treatment (HHS & HHS+JNK2I) compared to sham controls (CTL; F3,34=1.292, ns). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns, no statistical significance; *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Control (CTL) mice, vehicle-treated HHS-WT (HHS) mice, JNK2I-treated HHS-WT (HHS+JNK2I) mice, n=10; JNK2I-treated sham control (CTL+JNK2I) mice, n = 8.

2.2. Behavioral Experiments

A series of behavioral tests including Elevated Plus-Maze (EPM), Light/Dark Box (LDB) Exploration, and Open Field (OF) were conducted to examine anxiety behaviors using our well-established protocols as previously described.41,42 The Pavlovian learning and memory was assessed using a cued fear conditioning paradigm including: 1) delay conditioning including an unconditioned stimulus (US) and a conditional stimulus (CS; tone plus foot shock) with three repeats; 2) 7 days extinction session (extinction test daily) in the original conditioning context (without tone and shock); 3) cue tests (three consecutive exposures in the original conditioning context in the presence of CS only) to test context-dependent fear associative learning and memory as previously described.43,44 Additional details can be found in the expanded online Supplemental Methods Section.

2.3. Biochemical measurements

mRNA and protein expression were measured using quantitative real-time PCR (Primer sequences were shown in Table S1) and immunoblotting assays as we have previously described. 25,39,45 Total genomic DNA methylation was assessed as the enrichment of methylation marker 5-methylcytosine (5mC) using the immuno-dot blot assay, and the status of c-JUN binding to the Dnmt1 promoter was assessed using Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay as previously described.39,41,42,45,46

2.4. Statistical analysis

Significant differences were assessed by Student t-test (between two groups) or one-way ANOVA (between three groups) for EPM, LDB, qRT-PCR, Immunoblotting, Dot Blot and ChIP assays (two-tailed), or two-way repeated ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons for fear conditioning using IBM SPSS Statistic 24 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Values were represented as mean ± S.E.M. The criterion for statistical significance was p<0.05. The statistical significance was represented as: * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p<0.001, and ##p<0.0001.

3. Results

3.1. JNK2 Enhances Anxiety-like Behaviors in HHS-WT Mice

We first performed EPM, LDB, and OF tests in HHS-WT and sham control mice (Fig. 1A) using our well-established protocols as previously described.42 Fig. 1B shows a significantly decreased duration of stay in the EPM open arms in HHS-WT mice compared to that of controls, suggesting BAW-increased anxiety-like behaviors. Consistently, HHS-WT mice spent significantly more time in the dark compartment than in the light compartment compared to sham controls during the LDB test (Fig. 1C), and HHS-WT mice showed markedly reduced travel distance within the center arena in the OF test (Fig. 1D), while the locomotor activities (total distance traveled) were unchanged compared to sham controls (Fig. 1E). Thus, findings from the tests in three different paradigms all demonstrate that BAW enhances anxiety-like behaviors in HHS mice.

We have previously shown that increased JNK2 causatively leads to heart rhythm abnormalities (cardiac arrhythmias).15,24,25,47 Here, JNK2-specific contribution to BAW-evoked anxiety-like behaviors was assessed by administering our well-validated JNK2 inhibitor JNK2I15,24,25,40 in HHS-WT mice in vivo using the protocol as shown in Fig.1A. Intriguingly, JNK2-specific inhibition diminished those anxiety-like behaviors (Figs.1B-1D, blue bars at right), suggesting an anxiolytic effect of the JNK2 inhibition. Moreover, JNK2I-treated sham controls (Figs.1B-1E, far right bars) showed no detectable adverse behavioral effects or basal anxiolytic effect compared to vehicle-treated sham controls, suggesting no adverse effect of JNK2I on the baseline behaviors in sham control mice. Overall, our data suggest that JNK2 plays a causal role in BAW-evoked anxiety-like behaviors in HHS mice.

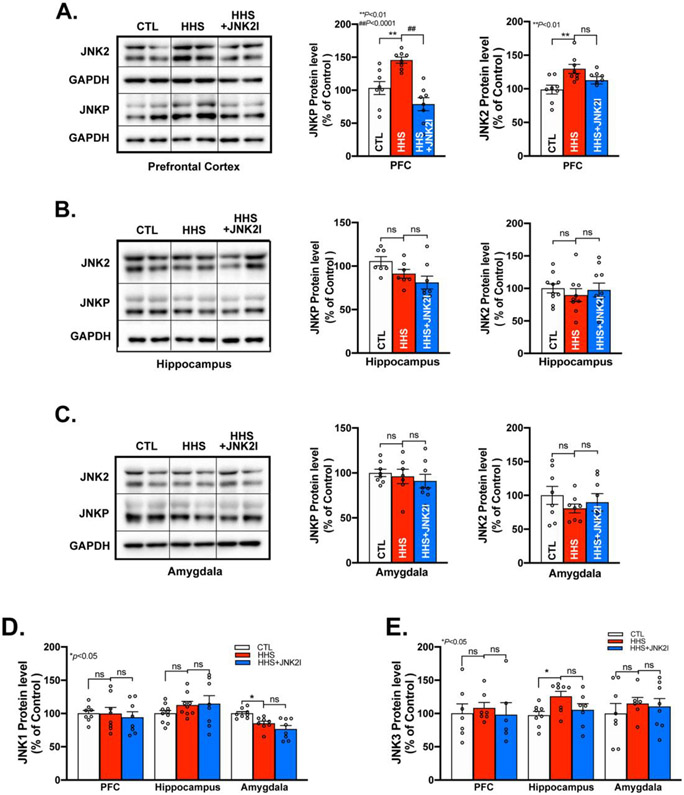

3.2. Enhanced Activation and Expression of JNK2, but not JNK1 & JNK3, in the PFC of HHS-WT Mice

Next, we assessed JNK2 activation by detecting phosphorylated total JNK proteins using immunoblotting in three major brain regions, PFC, hippocampus, and amygdala that have been linked to anxiety.48-50 We found that activated JNK was markedly enhanced in HHS-WT PFC, evidenced by a higher level of phosphorylated JNK proteins (JNK-P, activated total JNK) than that of sham controls, while JNK2 proteins were also significantly increased (Fig.2A). To assess the stress influence of the post-behavioral test brain tissue samples, we assessed JNK activation in HHS PFC from naïve home-cage mice (untrained) and found a comparable level of phosphorylated JNK (Supplemental Fig.S1), suggesting the significant impact of BAW on JNK activation in HHS PFC. In line with eliminated anxiety-like behaviors by JNK2 inhibition as shown in Fig.1, JNK2 inhibition markedly suppressed JNK-P and slightly reduced JNK2 expression in JNK2I-treated HHS mice compared to vehicle-treated HHS controls (Fig.2A, far right bars). In contrast, phosphorylated JNK and JNK2 expression were unchanged in the hippocampus and amygdala of HHS-WT mice (Figs.2B-C). It is known that there are three JNK isoforms, JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3 expressed in the brain.32 We found JNK1 was not altered in the PFC and hippocampus and JNK3 was unchanged in the PFC and amygdala in HHS-WT mice (Figs.2D-E). Although marginally decreased amygdala JNK1 and moderately increased hippocampus JNK3 were found in HHS-WT mice, these changes may not have an impact on the JNK activity in those regions, evidenced by unchanged JNK activation (JNK-P) in both the amygdala and hippocampus as shown in Figs.2B-C. In addition, JNK2I treated HHS mice showed unaltered levels of JNK1 and JNK3 proteins in all three brain regions, comparable to that seen in sham controls (Figs.2D-E, far right bars), suggesting the lack of adverse effects of JNK2I on expression of other JNK isoforms. Thus, BAW leads to activated JNK2, but not JNK1 or JNK3, in PFC, which could drive BAW-evoked anxiety-like behaviors in HHS mice.

Figure 2.

Increased JNK2, but not JNK1 & JNK3, is Exhibited in PFC, but not Hippocampus and Amygdala in HHS-WT Mice. A) Representative immunoblotting images and summarized protein expression of increased JNK2 and JNK-P in PFC of HHS-WT (HHS) mice vs controls (CTL; JNKP protein expression: F2,21=16.01, p<0.0001; JNK2 protein expression: F2,21=6.041, p<0.01); B-C) Representative immunoblotting images and pooled data of unchanged JNK-P and JNK2 protein expression in hippocampus (B) and amygdala (C) of HHS-WT (HHS) mice vs sham controls (CTL); D-E) Representative immunoblotting images and summarized data of protein expression of JNK1 (D) and JNK3 (E) in PFC, hippocampus, and amygdala of HHS-WT (HHS) mice vs sham controls (CTL). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ns, no statistical significance; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ##p<0.0001. n=8 per group.

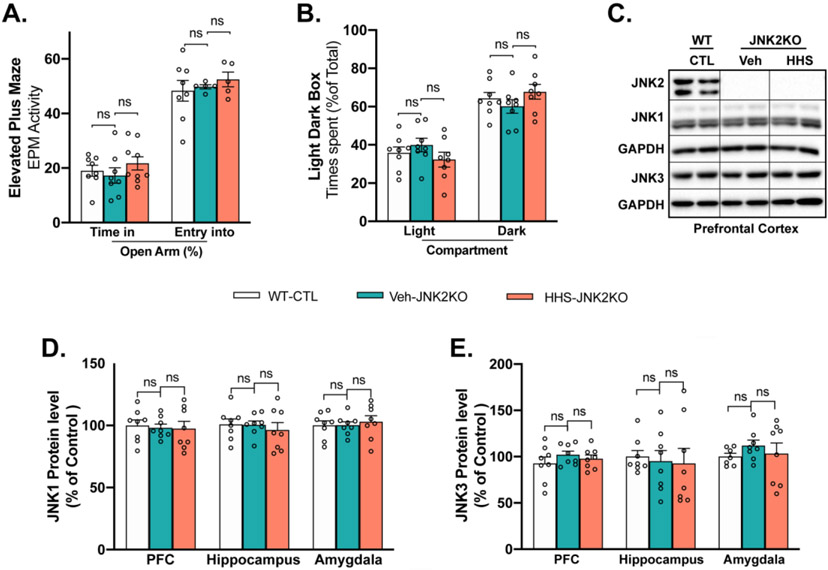

3.3. JNK2 Depletion Attenuates BAW-evoked Anxiety-like Behaviors in HHS-JNK2KO Mice

The JNK2 specific action in BAW-evoked anxiety-like behaviors was further determined in JNK2-specific knockout mice as we have previously described.24,25 JNK2KO mice were exposed to the HHS protocol. Strikingly, JNK2-specific depletion in JNK2KO mice completely prevented the BAW-evoked anxiety-like behaviors seen in HHS-JNK2KO mice. Figs.3A-B show that HHS-JNK2KO mice spent similar times in the open arms and light box in EPM and LDB tests as that of vehicle-treated JNK2KO and WT controls. In addition, vehicle-treated sham control JNK2KO mice exhibited normal behaviors comparable to those of WT sham controls (Figs.3A-B, far left bars), suggesting unchanged baseline behaviors of JNK2KO mice. Moreover, the protein levels of JNK1 and JNK3 remained unchanged in the three brain regions (PFC, hippocampus, amygdala) in HHS-JNK2KO mice compared to vehicle-treated JNK2KO and WT controls, while the amount of JNK2 proteins were undetectable (Figs.3C-E). Thus, JNK2 drives BAW-evoked anxiety-like behaviors in HHS mice.

Figure 3.

JNK2 Depletion Attenuates BAW-evoked Anxiety-like Behaviors in HHS-JNK2KO Mice. A-B) EPM(A) and LDB (B) tests showing that HHS JNK2KO mice spent similar times in the open arms and light box as that seen in vehicle-treated (veh) JNK2KO and WT controls (WT-CTL); C) Representative immunoblotting images of JNK1, JNK2, JNK3 in PFC of WT sham control (WT-CTL), vehicle-treated (veh) JNK2KO sham control, and HHS-JNK2KO mice; D-E) Summarized data of JNK1 (D) and JNK3 (E) protein expression in PFC, hippocampus and amygdala of WT controls (WT-CTL), vehicle-treated (veh) JNK2KO sham control, and HHS-JNK2KO mice. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ns, no statistical significance. n=8 per group.

3.4. JNK2 Impairs Cognition in HHS-WT Mice

Cognitive decline is another well-recognized BAW-evoked deficit.51 We assessed associative learning using a cured fear conditioning paradigm (Fig.4A). Prior to alcohol treatment, all mice showed a similar freezing time response to three repetitive paired conditional stimulations (CSs) and unconditional stimulations (USs) stimuli in the training session (Fig.4B), reflecting a similar fear response in those randomly grouped mice. In the extinction test sessions (extinction Day1-Day7), freezing behaviors were measured in the same training context but in the absence of CS and US stimuli. The freezing time measured daily was progressively declined during the seven consecutive days of the extinction tests and the fear extinction was comparable between HHS-WT, JNK2I-treated HHS-WT, and sham control groups (Fig.4B), suggesting a normal context-dependent fear extinction in HHS mice.

Figure 4.

Activated JNK2 Impairs Cognition in HHS-WT Mice. A) Schematic of the cued fear conditioning test protocol; B) Summarized data of fear acquisition in the training session (CS-US), context-dependent extinction from Day-1 to Day-7 in control (CTL), vehicle-treated HHS (HHS) mice and JNK2I-treated HHS-WT (HHS+JNK2I) mice. Pooled data of three consecutive cue tests showing a remarkable fear recall in both control and JNK2I-treated HHS-WT mice but a slightly reduced level of freezing response in vehicle-treated HHS-WT in the first cued test (cue 1), while impaired fear extinction characterized by continuously increased freezing time in cue 2 and cue 3, in vehicle-treated HHS-WT mice compared to that of JNK2I-treated HHS-WT (HHS+JNK2I) and control mice. Statistical test results of the fear extinction Session: A two-way repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant main effect (extinction; F6,162=3.105, p<0.01), however there was no significant interaction between the treatment (groups) and extinction (F12,102 =1.249, p>0.05). The Bonferroni’s post hoc comparison showed a significant decrease in the freezing time over the course of Days 1- 7 in the HHS-WT group (p<0.05: Day1 vs. Day 6, Day1 vs Day7, Day 3 vs. Day 6, Day3 vs Day 7) and in the HHS+JNK2I group (p<0.001: Day 1 vs. Day 5, Day 2 vs. Day 5; p<0.01: Day 1 vs. Day 7; p<0.05: Day 1 vs. Day 6, Day 3 vs. Day 5, Day 4 vs. Day 5, respectively). There was no statistical significance in the freezing response for Day1 to Day7 in the WT control group (p=0.06). Statistical test results of the Cued Test Session: A two-way repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant main effect (fear response; F3,81=24,976, p<0.000) and significant interaction of the treatment and fear response (F6,81=4.032, p<0.001). The Bonferroni’s post hoc comparison showed a significant increase in the freezing time from the 2nd cued and 3rd cued tests in HHS-WT mice compared to that of controls (**p<0.01, HHS vs controls) and that of JNK2I-treated HHS-WT mice (#p<0.05, ###p<0.001, HHS vs HHS+JNK2I). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. n=10 per group.

In the cued test session, mice were returned to the original conditioning context but in the presence of three consecutive CSs (tone) using a standard protocol as previously described.43,44 HHS-WT mice exhibited a progressively increased freezing time, which was in contrast to a decremented freezing time in response to the three consecutive cue tests in the sham controls, reflecting a remarkable impairment of cued fear extinction induced by BAW in HHS-WT mice. Strikingly, JNK2 inhibition completely normalized this BAW-induced cognitive impairment (Fig.4B, blue line), which is consistent with the rescue effect of JNK2 inhibition on BAW-evoked anxiety-like behaviors as shown in Fig.2. It is notable that this JNK2-specific inhibition did not change the expression of JNK1 and JNK3 (Fig.3D-E), supporting the specificity and efficacy of JNK2 inhibition in alleviating BAW-evoked behavioral deficits.

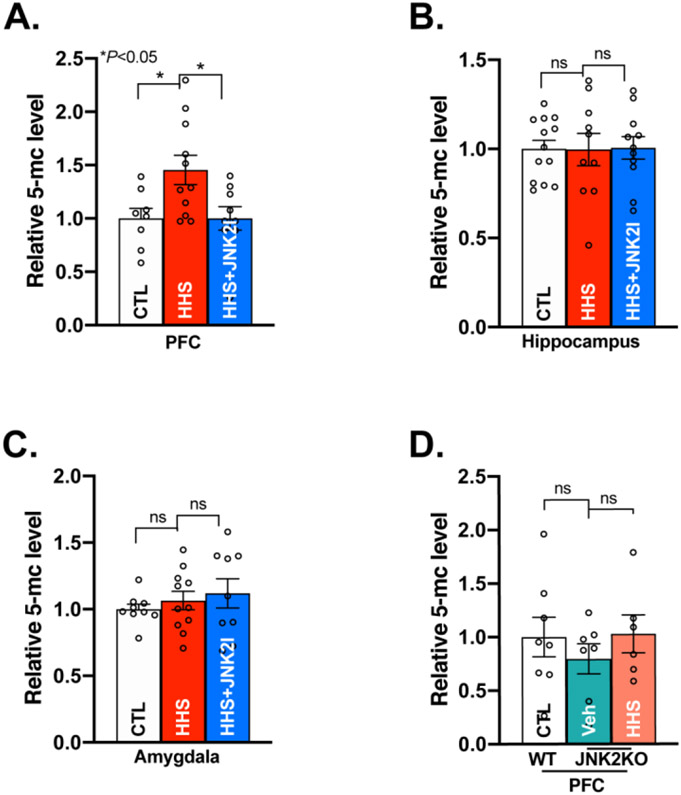

3.5. JNK2 Enhances DNA Methylation in HHS Mice

We and others have shown that epigenetic programing such as DNA methylation and histone tail deacetylation crucially regulates gene expression and promotes anxiety and alcohol addiction.37,38,52,53 DNA methylation occurs mainly at cytosine of CpG dinucleotides catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) to form 5-methylcytosine.54-56 Given that the expression and activity of JNK2 were increased in HHS-WT PFC, we assessed the role of JNK2 in BAW-evoked DNA methylation by assessing the level of 5-methylcytosine using a 5-methylcytosine-specific antibody on total genomic DNA. Indeed, the amount of 5-methylcytosine on total genomic DNA was significantly increased in HHS-WT PFC compared to sham controls (Fig.5A). In contrast, genomic DNA methylation in the hippocampus and amygdala remained unchanged in HHS-WT mice (Fig.5B-C). Strikingly, JNK2 inhibition by in vivo treatment of the JNK2 inhibitor JNK2I in HHS-WT mice completely reversed this enhanced DNA methylation in the PFC to the baseline level seen in sham controls (Fig.5A, far right bar), while JNK2 inhibition had no effect on the level of 5-methylcytosine in the hippocampus and amygdala (Fig.5B-C, far right bars). This JNK2 specific action in DNA methylation in the HHS-WT PFC was further confirmed in HHS-JNK2KO mice. Fig.5D shows that JNK2-specific depletion completely prevented BAW-induced DNA methylation, evidenced by comparable levels of 5-methylcytosine in the PFC between HHS-JNK2KO and vehicle-treated JNK2KO sham control mice. In addition, vehicle-treated JNK2KO mice exhibited a similar level of 5-methylcytosine as that of sham WT controls. Histone tail deacetylation, another epigenetic regulatory mechanism, is also known to be catalyzed by histone deacetylases (HDACs) including HDAC isoforms 1, 2, and 3, which were reported to contribute to alcohol addiction and withdrawal behaviors.57-59 In HHS-WT mice, we however found that the expression levels of Hdac1, 2, and 3 were unchanged in all three brain regions (Supplemental Fig.S2). Taken together, our results demonstrate that activated JNK2 causally enhances DNA methylation in the PFC of HHS brains.

Figure 5.

Activated JNK2 Increases DNA Methylation in the PFC of HHS-WT Mice. A) Summarized data of 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) Dot Blot assay showing increased 5-methylcytosine level of genomic DNA in the PFC of HHS-WT (HHS) mice, while JNK2 inhibition reversed the level of 5-methylcytosine in HHS-WT PFC to the baseline level seen in sham controls (CTL; F2,25 = 5.012, p<0.05; CTL, n=8; HHS, n=11; HHS+JNK2I, n=10); B) Summarized data showing an unchanged level of overall DNA methylation in the hippocampus of HHS-WT (HHS) mice vs sham controls (CTL; F2,31= 0.00502, p>0.05, CTL, n=12; HHS, n=10; HHS+JNK2I, n=11); C) Summarized data showing an unchanged level of overall DNA methylation in the amygdala of HHS-WT (HHS) mice vs sham controls (CTL)( F2,26= 0.5523, p>0.05; CTL, n=9; HHS, n=11; HHS+JNK2I, n=9); D) Pooled data showing unchanged level of total genomic DNA methylation in HHS-JNK2KO PFC (with a JNK2 specific depletion) compared to vehicle-treated (Veh) JNK2KO sham controls (F2,16=0.6890, p>0.05; CTL, n=6; Veh-JNK2KO, n=7; HHS-JNK2KO, n=6). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ns, no statistical significance, *p<0.05.

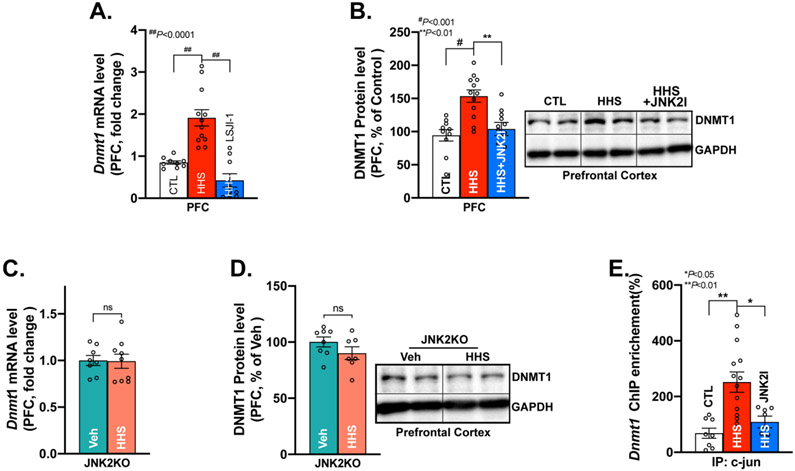

3.6. JNK2 Transcriptionally Upregulates DNMT1, Which Leads to Behavioral Deficits

We next explored how JNK2 drives DNA methylation in HHS mice. Accumulating evidence suggests that DNMTs (DNMT1, 3a, and 3b) are essential in catalyzing the DNA methylation.54,60 In the HHS-WT PFC, we found significantly increased expression of Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a mRNA, but unchanged Dnmt3b measured by qRT-PCR compared to that of sham controls (Fig.6A & Supplemental Fig.S3A-B). Intriguingly, JNK2 inhibition in JNK2I-treated HHS-WT mice completely normalized Dnmt1 mRNA and protein expression in the PFC (Fig.6A-B, far right bars), while it had no impact on DNMT3a and DNMT3b (Supplemental-Fig.S3A-B, far right bars). Consistent with unchanged JNK activation and expression profiles of both hippocampus and amygdala in HHS-WT mice (Fig.2), expression of all the Dnmt isoforms (Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b) were unaltered in those two regions (Supplemental Figs.S4A-F). Next, this JNK2-specific action in Dnmt1 was further confirmed in JNK2KO mice. In HHS-JNK2KO mice, JNK2 depletion completely prevented BAW-increased Dnmt1 mRNA and protein expression in HHS-JNK2KO PFC compared to vehicle-treated JNK2KO sham controls (Fig.6C-D). Meanwhile, Dnmt1 mRNA and protein in the hippocampus and amygdala were also unchanged in HHS-JNK2KO mice compared to vehicle-treated JNK2KO controls (supplemental Fig.S5A-D). Thus, JNK2 causatively upregulates Dnmt1 expression in the PFC, but not the hippocampus and amygdala in HHS mice.

Figure 6.

Activated JNK2 Transcriptionally Upregulates DNA Mmethyltransferase1 (DNMT1) in HHS-WT and HHS-JNK2KO Mice. A-B) Summarized quantitative RT-PCR data and immunoblotting data showing significantly increased DNMT1 mRNA levels (A) and protein expression (B) in vehicle-treated HHS-WT (HHS) PFC vs that of sham controls, while reversed DNMT1 mRNA and protein expression in JNK2 inhibitor JNK2I-treated HHS-WT (HHS+JNK2I) PFC (mRNA level: F2, 27=24.63, p<0.0001; protein level: F2, 27=12.03, p<0.001; CTL, n=9; HHS, n=12; HHS+JNK2I, n=9); C-D) Representative immunoblotting images and summarized data DNMT1 mRNA (C) and protein (D) expression in the PFC of HHS-JNK2KO mice vs vehicle-treated (Veh) JNK2KO sham controls. n=8 per group; E) Chromatin Immunoprecipitation data showing a significantly increased binding of c-JUN to the promoter of Dnmt1 in HHS-WT (HHS) PFC compared to that of sham controls (CTL), And JNK2 inhibition decreased the amount of c-JUN bound to the Dnmt1 promoter. (F2, 26= 9.462, p<0.001; CTL, n=8; HHS, n=14; HHS+JNK2I, n=7). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ns, no statistical significance, ** p<0.01, # p<0.001, ## p<0.0001.

We have previously shown that JNK2 regulates gene expressions via enhanced binding of c-JUN to its target genes in the heart.24,40 To further pinpoint the role of JNK2 in Dnmt1 expression, we performed ChIP assays using a c-JUN specific antibody and found a significantly increased binding of c-JUN to the promoter of Dnmt1 in HHS-WT PFC compared to that of controls as shown in Fig.6E. Moreover, JNK2 inhibition in JNK2I-treated HHS-WT mice suppressed the amount of c-JUN bound to the Dnmt1 promoter (Fig.6E, far right bar), which led to reduced mRNA and protein expression of DNMT1 in the PFC of HHS-WT mice (Fig.6A-B). This normalized DNMT1 expression by JNK2-specfic inhibition was well aligned with the completely reversed DNA methylation as shown in Fig.5A. Thus, activated JNK2 transcriptionally upregulates Dnmt1 expression and critically upregulates DNA methylation in HHS PFC.

Finally, contributions of DNMT1 in BAW-evoked DNA hypermethylation and anxiety-like behaviors were assessed in DNMT1 inhibitor 5-Aza-treated HHS-WT mice. Remarkably, DNMT1 inhibition in vivo completely reversed BAW-evoked DNA hypermethylation in the PFC of 5-Aza-treated HHS-WT mice to the baseline level seen in sham controls (Figs.7A), which is consistent with the rescue effect of JNK2 inhibition on BAW-evoked hypermethylation as shown in Fig.5A. Moreover, DNMT1 inhibition completely eliminated the BAW-evoked anxiety-like behaviors seen in HHS-WT mice, evidenced by increased time spent in the open arms and light box in EPM and LDB tests compared to vehicle-treated HHS-WT mice (Figs.7B-C). Taken together, JNK2 drives BAW-evoked anxiety-like behaviors via a c-JUN-Dnmt1-mediated epigenetic regulation in HHS mice (Figs.7D).

Figure 7.

DNMT1 Inhibition Attenuates BAW-evoked DNA Hypermethylation and Anxiety-like Behaviors in HHS-WT Mice. A) Summarized data of 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) Dot Blot assay showing that DNMT1 inhibition in 5-Azacytidine (5-Aza)-treated HHS-WT (HHS+5-Aza) mice reversed the level of 5-mC in genomic DNA from HHS-WT PFC to the baseline level seen in sham controls (CTL; F2,16=10.21, p<0.01; CTL, n=6; HHS, n=7; HHS+5-Aza, n=6); B-C) Summarized data of EPM (B) and LDB (C) tests showing that DNMT1 inhibitor 5-Aza-treated HHS-WT (HHS+5-Aza) mice spent significantly more time in the open arms and light box than that of vehicle-treated HHS-WT (HHS) mice. EPM (time spent in open arms): F2, 21= 9.596, p<0.01; LDB (time spent in light and dark compartment): F2,21= 4.873, p<0.05; n=8 per group; D) Schematic diagram of the mechanism of stress kinase JNK2-driven c-JUN-DNMT1 pathway in DNA methylation that underlies anxiety-like behaviors during binge alcohol withdrawal. JNK2 specific inhibition completely abolished this binge alcohol withdrawal-evoked DNA methylation and anxiety-like behaviors. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

4. Discussion

In the current studies, we demonstrate that binge alcohol withdrawal (BAW) evokes anxiety-like behaviors and associative learning impairment in our Holiday Heart Syndrome (HHS) mouse model. We further reveal for the first time that stress kinase JNK2 activation in the PFC, but not the hippocampus and amygdala, is essential in the BAW-evoked behavioral deficits in HHS mice. Another discovery is that activated JNK2 transcriptionally upregulates DNA methyltransferase1 (DNMT1) expression, which in turn enhances total DNA methylation in the PFC but not the hippocampus and amygdala in HHS mice. Finally, striking rescue effects of either JNK2-specific inhibition/depletion or DNMT1 inhibition on rescued BAW-evoked behavioral deficits and a completely normalized signaling pathway of c-JUN-Dnmt1 and genomic DNA methylation shed new light on JNK2 as a potential novel therapeutic target for alcohol withdrawal treatment and/or prevention.

4.1. Critical Role of Stress Kinase JNK2 in BAW-evoked Adverse Behaviors

It is well known that the stress kinase JNK is activated in response to various stresses and then modulates cellular processes (i.e. proliferation, apoptosis). Thus, JNK is critical in the development of various diseases.19-22,63 Extensive studies suggest that activation of stress-response kinase JNK represents a common feature in many organs with either acute or chronic alcohol exposure, which contributes to alcohol-caused cell death and tissue injury.16,64-67 To date, there are a number of well-established binge alcohol drinking models that have been used for adverse BAW behavioral studies.10,68-70 Our group recently revealed a causal role of stress-response kinase JNK2 in cardiac arrhythmias in both humans and our well-characterized HHS animal models.15 The current studies using the same HHS mouse model with well-characterized heart phenotypes provide the first evidence that activated JNK2, but not JNK1 and JNK3, predominately regulate BAW-evoked anxiety-like behaviors and cognitive impairment during binge alcohol withdrawal. The JNK2-specific actions in the brain and heart15,23-25,40 suggest that activated JNK2 likely acts as a significant pathological node that governs BAW-evoked pathological remodeling in both organs.

In the brain, all three JNK isoforms JNK1, JNK2 and JNK3, are expressed, but the functions of the three JNK isoforms appear to be distinctly different.32 Studies suggest that endogenous JNK1 regulates baseline learning, however it has tonic inhibitory effects on anxiety-like behaviors when JNK1 is depleted (JNK1 knockout) or specifically inhibited (by a JNK1-specific peptide).31,71-73 In contrast, either JNK2 or JNK3 knockout affected anxiety-like behaviors without any stressor stimuli.72 However, in the context of restraint as an acute stressor, JNK2 and JNK3 showed an excitatory role for certain behaviors such as contextual fear learning.71,73 Thus, JNK1 is likely a major physiologically activated isoform in the brain, while JNK2 and JNK3 isoforms exhibit a lower level basal activity but increased responsivity under stress challenge conditions.31,72,73 The contribution of stress kinase JNK in alcohol-induced adverse withdrawal behaviors has not been previously reported, and our findings here are the first evidence showing JNK2 causally enhance anxiety and cognitive impairment during binge alcohol withdrawal. In addition, our results demonstrated that JNK2-specific inhibition or depletion has no adverse effects on the baseline behaviors and changed expression profiles of other JNK isoforms (JNK1 and JNK3), it is however strikingly rescued BAW-evoked adverse behavioral deficits. Thus, our findings not only demonstrate the essential role of JNK2 in BAW-induced behavioral deficits, but also the effectiveness and importance of JNK2 isoform-selective inhibition for alleviating those adverse effects of BAW.

4.2. Novel Underlying Molecular Mechanism of JNK2-Regulated DNA Methylation

Another discovery in the current study is that the novel mechanism of JNK2-enhanced DNA methylation through a JNK2-specific transcriptional upregulation of DNMT1 in the HHS PFC. Recently, epigenetic programming including DNA methylation and histone tail modification have been recognized as a crucial mechanism in regulating alcohol- and emotional stress-induced behavioral deficits.37,38,52,53,62,74 We focused on the role of JNK2 in DNA methylation because unchanged HDACs was found in HHS mice. By using mouse models of JNK2-specific depletion (JNK2KO) and JNK2 inhibition (JNK2 inhibitor-treatment), we revealed a previously unrecognized JNK2-specific action in enhanced DNA methylation in HHS PFC but not in the hippocampus and amygdala. In humans, the genome-wide epigenomic approach identified profound disturbances in the DNA methylation status of numerous genes in the post-mortem PFC and blood from individuals with an alcohol abuse history or alcohol withdrawal symptoms.75-79 And, this increased DNA methylation has also been found to be critical in alcohol dependence behavioral phenotypes and stress-associated behavioral deficits due to various stressors.37,53,80-83 Our mechanistic studies here demonstrate for the first time that stress kinase JNK2 is responsible for DNA hypermethylation, which is critical in BAW-evoked behavioral deficits.

DNA methylation is known to be catalyzed by DNMTs including DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b.84 In HHS mice, both DNMT1 and DNMT3a were increased in the PFC, while DNMT3b was unchanged. Interestingly, JNK2-specific inhibition in HHS mice only reversed DNMT1 expression in the PFC, but had no effect on the isoforms of DNMT3a and DNMT3b. Of note, DNMT1 is known as a maintenance methyltransferase and DNMT3a and DNMT3b are the de novo methyltransferases.85,86 While DNMT3a may increase the process of de novo DNA methylation, JNK2-regulated DNMT1 however is a primary driver in maintaining the status of DNA hypermethylation in the HHS PFC. The functional role of DNMT1 has been shown in alcohol dependence and stress-induced anxiety-like behaviors.37,53 Pharmacological DNMT1 suppression was reported to reverse alcohol-or stress-induced anxiety-like behaviors in animal models.62,87,88 Specific deletion of DNMT1 (but not other DNMT isoforms) clearly showed anxiolytic effects.89 In HHS mice, the striking rescue effect of the DNMT1 inhibition on anxiety-like behaviors demonstrates the critical role of DNMT1 in BAW-evoked behavioral disorders. Moreover, the JNK2-specific rescue effect on the DNMT1 expression and completely normalized level of genomic DNA methylation and behaviors in JNK2I-treated and JNK2KO HHS mice further supports the causal role of JNK2 in BAW-evoked DNA hypermethylation and the consequential behavioral deficits.

To date, JNK2 isoform-specific action in DNMT gene regulation in the brain remains completely unknown. Recent reports in cancer cells suggest that JNK is linked to DNMT1 expression by using a JNK isoform non-selective inhibitor SP600125.34,36 Our findings here have shown for the first time that JNK2 specifically upregulates DNMT1 expression through a direct binding of the JNK downstream target c-JUN to the DNMT1 gene promoter in the HHS brain. And the functional consequence of this JNK2-specific action in DNMT expression is evidenced by the striking rescue effects of JNK2-specific inhibition or depletion in both DNMT1-mediated DNA methylation and BAW-evoked behavior deficits, which demonstrate the causal role of JNK2 in BAW-evoked epigenetic remodeling and adverse behavioral development. In line with this JNK2 specific action in the DNMT1 gene regulation in the brain, our group recently reported the specific role of JNK2 (but not JNK1) in the regulation of other genes in the heart.24,40 Thus, the JNK2 isoform-specific gene regulation underlies not only behavioral deficits in the brain but also drives arrhythmias in the heart, suggesting its essential role as a central driver in BAW-evoked pathological molecular remodeling in multiple organs.

5. Implications and limitations

Our current study demonstrates that JNK2 activation in the PFC critically contributes to enhanced anxiety-like behaviors and impaired cognition via JNK2-augmented DNMT1 gene regulation and DNA methylation. With an increasing body of evidence showing the critical role of DNA methylation in alcohol and stress-induced behavioral deficits in humans and animal models, the findings of JNK2-specific actions in DNMT1-mediated DNA methylation and BAW-evoked behavioral deficits are clinically significant, because they shed new light on modulating JNK2 activity as a potential therapeutic target to prevent and/or treat binge alcohol withdrawal-induced adverse behaviors.

Notably, glucocorticoids are vital stress response hormones, which could be influenced by circadian rhythms.26 Although all of the behavioral studies and brain sample collection were strictly performed within the same time frame for each experiments in the current studies to avoid potential circadian rhythm interference, whether circadian rhythm is involved in this BAW-evoked JNK activation and behavioral deficits would be of interest for future investigations. Another aspect worthy of mention is that BAW-evoked JNK2 activation and its impact on the signaling pathway of c-JUN-Dnmt1 and DNA methylation were only found in the PFC region, not the hippocampus or amygdala in HHS mice. Although the JNK2-dependent DNMT1 signaling is unaltered in the hippocampus and amygdala in HHS mice, our biochemistry studies were conducted using the whole tissue of PFC, hippocampus, and amygdala. Whether the subregions of these three major brain regions differ is worthy of further investigations. In addition, the PFC is considered to play a central role in regulating a multitude of limbic and executive functions.3,90 Therefore, our current study cannot rule out the potential influences of the PFC in the function of other brain regions including hippocampus and amygdala. However, our findings of JNK2-driven molecular changes in the PFC clearly pave the way for future investigations to understand the intricate relationship between different brain regions in BAW-evoked aberrant behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Stress Kinase JNK2 drives Binge alcohol withdrawal-evoked behavioral deficits.

JNK2-evoked DNA hypermethylation is responsible for BAW evoked behavioral deficits.

The JNK2 drives DNA hypermethylation via the c-JUN-Dnmt1 signaling pathway

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health [R01HL113640, R01HL146744, R01AA024769, AA024769S2 to XA, and AA024769S1 to JB (trainee) & XA] and [R21AA027848 to ED].

Abbreviations:

- 5-Aza

5-Azacytidine

- 5mC

5-methylcytosine

- BAW

binge alcohol withdrawal

- BAC

Blood alcohol concentration

- CS

conditional stimulus

- DNMT1

DNA methyltransferase1

- EPM

Elevated Plus-Maze (EPM)

- HDACs

histone deacetylases

- HHS

Holiday Heart Syndrome

- JNK

c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase

- LDB

Light/Dark Box

- OF

Open Field

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- US

unconditioned stimulus

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest in this research.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Walker RK et al. The good, the bad, and the ugly with alcohol use and abuse on the heart. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37, 1253–1260, doi: 10.1111/acer.12109 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llerena S et al. Binge drinking: Burden of liver disease and beyond. World J Hepatol 7, 2703–2715, doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i27.2703 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephens DN & Duka T Cognitive and emotional consequences of binge drinking: role of amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 363, 3169–3179, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0097 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunzerath L, Faden V, Zakhari S & Warren K National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism report on moderate drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28, 829–847, doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128382.79375.b6 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piano MR Alcohol’s Effects on the Cardiovascular System. Alcohol Res 38, 219–241 (2017). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voskoboinik A, Prabhu S, Ling LH, Kalman JM & Kistler PM Alcohol and Atrial Fibrillation: A Sobering Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 68, 2567–2576, doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.074 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM, Kloska DD & Schulenberg JE High-Intensity Drinking Among Young Adults in the United States: Prevalence, Frequency, and Developmental Change. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40, 1905–1912, doi: 10.1111/acer.l3164 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vital signs: binge drinking prevalence, frequency, and intensity among adults - United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 61, 14–19 (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patrick ME & Azar B High-Intensity Drinking. Alcohol Research 39, e1–e7 (2017). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KM, Coehlo M, McGregor HA, Waltermire RS & Szumlinski KK Binge alcohol drinking elicits persistent negative affect in mice. Behav Brain Res 291, 385–398, doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.05.055 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tonelo D, Providencia R & Goncalves L Holiday heart syndrome revisited after 34 years. Arq Bras Cardiol 101, 183–189, doi: 10.5935/abc.20130153 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kodama S et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 57, 427–436, doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.641 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Djousse L et al. Long-term alcohol consumption and the risk of atrial fibrillation in the Framingham Study. Am J Cardiol 93, 710–713, doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.12.004 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowenstein SR, G. P., Cramer J, Oliva PB, Ratner K . The role of alcohol in new-onset atrial fibrillation. Archives of internal medicine 143, 1882–1885 (1983). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan J et al. Role of Stress Kinase JNK in Binge Alcohol-Evoked Atrial Arrhythmia. J Am Coll Cardiol 71, 1459–1470, doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.060 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang L, Wu D, Wang X & Cederbaum AI Cytochrome P4502E1, oxidative stress, JNK, and autophagy in acute alcohol-induced fatty liver. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 53, 1170–1180, doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.06.029 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Relja B et al. Differential Relevance of NF-kappaB and JNK in the Pathophysiology of Hemorrhage/Resususcitation-Induced Liver Injury after Chronic Ethanol Feeding. PLoS One 10, e0137875, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137875 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pascual M, Valles SL, Renau-Piqueras J & Guerri C Ceramide pathways modulate ethanol-induced cell death in astrocytes. J Neurochem 87, 1535–1545, doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02130.x (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis RJ Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell 103, 239–252 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rose BA, Force T & Wang Y Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in the heart: angels Versus demons in a heart-breaking tale. Physiol Rev 90, 1507–1546, doi: 10.1152/physrev.00054.2009 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karin M & Gallagher E From JNK to pay dirt: jun kinases, their biochemistry, physiology and clinical importance. IUBMB Life 57, 283–295, doi:H527470040088211 [pii] 10.1080/15216540500097111 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogoyevitch MA The isoform-specific functions of the c-Jun N-terminal Kinases (JNKs): differences revealed by gene targeting. Bioessays 28, 923–934, doi: 10.1002/bies.20458 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan J et al. c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation contributes to reduced connexin43 and development of atrial arrhythmias. Cardiovasc Res 97, 589–597, doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs366 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan J et al. The stress kinase JNK regulates gap junction Cx43 gene expression and promotes atrial fibrillation in the aged heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 114, 105–115, doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.11.006 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan J et al. Stress Signaling JNK2 Crosstalk With CaMKII Underlies Enhanced Atrial Arrhythmogenesis. Circ Res 122, 821–835, doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312536 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pahng AR et al. Dysregulation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase phosphorylation in alcohol dependence. Alcohol 75, 11–18, doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2018.04.006 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang P et al. The Neuroprotective Effects of Carvacrol on Ethanol-Induced Hippocampal Neurons Impairment via the Antioxidative and Antiapoptotic Pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 4079425, doi: 10.1155/2017/4079425 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh AK, Jiang Y, Gupta S & Benlhabib E Effects of chronic ethanol drinking on the blood brain barrier and ensuing neuronal toxicity in alcohol-preferring rats subjected to intraperitoneal LPS injection. Alcohol Alcohol 42, 385–399, doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl120 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montesinos J et al. TLR4 elimination prevents synaptic and myelin alterations and long-term cognitive dysfunctions in adolescent mice with intermittent ethanol treatment. Brain Behav Immun 45, 233–244, doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.11.015 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollos P, Marchisella F & Coffey ET JNK Regulation of Depression and Anxiety. Brain Plast 3, 145–155, doi: 10.3233/BPL-170062 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohammad H et al. JNK1 controls adult hippocampal neurogenesis and imposes cell-autonomous control of anxiety behaviour from the neurogenic niche. Mol Psychiatry 23, 362–374, doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.203 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coffey ET Nuclear and cytosolic JNK signalling in neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci 15, 285–299, doi: 10.1038/nrn3729 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DNA methyl transferase 1: regulatory mechanisms and im- plications in health and disease. Int J Biochem Mol Biol 2, 58–66 (2011). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai CL et al. Activation of DNA methyltransferase 1 by EBV LMP1 Involves c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase signaling. Cancer Res 66, 11668–11676, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2194 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu J et al. Activation of SAPK/JNK mediated the inhibition and reciprocal interaction of DNA methyltransferase 1 and EZH2 by ursolic acid in human lung cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 34, 99, doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0215-9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heiland DH et al. c-Jun-N-terminal phosphorylation regulates DNMT1 expression and genome wide methylation in gliomas. Oncotarget 8, 6940–6954, doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14330 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warnault V, Darcq E, Levine A, Barak S & Ron D Chromatin remodeling--a novel strategy to control excessive alcohol drinking. Transl Psychiatry 3, e231, doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng Y, Fan W, Zhang X & Dong E Gestational stress induces depressive-like and anxiety-like phenotypes through epigenetic regulation of BDNF expression in offspring hippocampus. Epigenetics 11, 150–162, doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1146850 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan J et al. The stress kinase JNK regulates gap junction Cx43 gene expression and promotes atrial fibrillation in the aged heart. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 114, 105–115, doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.11.006 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao X et al. Transcriptional Regulation of Stress Kinase JNK2 in Pro-Arrhythmic CaMKIIdelta Expression in the Aged Atrium. Cardiovasc Res, doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy011 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong E et al. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Epigenetic Modifications Associated with Schizophrenia- like Phenotype Induced by Prenatal Stress in Mice. Biological Psychiatry 77, 589–596, doi:0.1016/j.biopsych.2014.08.012 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dong E, Guidotti A, Zhang H & Pandey SC Prenatal stress leads to chromatin and synaptic remodeling and excessive alcohol intake comorbid with anxiety-like behaviors in adult offspring. Neuropharmacology 140, 76–85, doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.07.010 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blanchard RJ & Blanchard DC Passive and active reactions to fear-eliciting stimuli. J Comp Physiol Psychol 68, 129–135 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pibiri F, Nelson M, Guidotti A, Costa E & Pinna G Decreased corticolimbic allopregnanolone expression during social isolation enhances contextual fear: A model relevant for posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105, 5567–5572 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao X et al. Transcriptional regulation of stress kinase JNK2 in pro-arrhythmic CaMKIIdelta expression in the aged atrium. Cardiovasc Res 114, 737–746, doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy011 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong E, Gavin DP, Chen Y & Davis J Upregulation of TET1 and downregulation of APOBEC3A and APOBEC3C in the parietal cortex of psychotic patients. Transl Psychiatry 2, e159, doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.86 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yan J et al. Novel methods of automated quantification of gap junction distribution and interstitial collagen quantity from animal and human atrial tissue sections. Plos One 9, e104357, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104357 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Padilla-Coreano N et al. Direct Ventral Flippocampal-Prefrontal Input Is Required for Anxiety-Related Neural Activity and Behavior. Neuron 89, 857–866, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.011 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bremner J Douglas. Brain imaging in anxiety disorders. Expert Rev. Neurotherapeutics 4, 275–284 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shin LM & Liberzon I The neurocircuitry of fear, stress, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 169–191, doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.83 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borlikova GG, Elbers NA & Stephens DN Repeated withdrawal from ethanol spares contextual fear conditioning and spatial learning but impairs negative patterning and induces over-responding: evidence for effect on frontal cortical but not hippocampal function? Eur J Neurosci 24, 205–216, doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04901.x (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu C et al. A DNA methylation biomarker of alcohol consumption. Mol Psychiatry 23, 422–433, doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.192 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barbier E et al. DNA methylation in the medial prefrontal cortex regulates alcohol-induced behavior and plasticity. J Neurosci 35, 6153–6164, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4571-14.2015 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Edwards JR, Yarychkivska O, Boulard M & Bestor TH DNA methylation and DNA methyltransferases. Epigenetics Chromatin 10, 23, doi: 10.1186/s13072-017-0130-8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suzuki MM & Bird A DNA methylation landscapes: provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat Rev Genet 9, 465–476, doi: 10.1038/nrg2341 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moore LD, Le T & Fan G DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology 38, 23–38, doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.112 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agudelo M et al. Effects of alcohol on histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) and the neuroprotective role of trichostatin A (TSA). Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35, 1550–1556, doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01492.x (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moonat S, Sakharkar AJ, Zhang H, Tang L & Pandey SC Aberrant histone deacetylase2-mediated histone modifications and synaptic plasticity in the amygdala predisposes to anxiety and alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry 73, 763–773, doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.012 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.D'Mello SR Regulation of Central Nervous System Development by Class I Histone Deacetylases. Dev Neurosci 41, 149–165, doi: 10.1159/000505535 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fatemi M, Hermann A, Pradhan S & Jeltsch A The activity of the murine DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1 is controlled by interaction of the catalytic domain with the N-terminal part of the enzyme leading to an allosteric activation of the enzyme after binding to methylated DNA. Journal of Molecular Biology 309, 1189–1199, doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4709 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cowan Lisa A, Talwar Sundeep & Yang Allen S Will DNA methylation inhibitors work in solid tumors? A review of the clinical experience with azacitidine and decitabine in solid tumors. Epigenomics 2, 71–86 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sakharkar AJ et al. Altered amygdala DNA methylation mechanisms after adolescent alcohol exposure contribute to adult anxiety and alcohol drinking. Neuropharmacology 157, 107679, doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107679 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raman M, Chen W & Cobb MH Differential regulation and properties of MAPKs. Oncogene 26, 3100–3112, doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210392 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aroor AR & Shukla SD MAP kinase signaling in diverse effects of ethanol. Life Sci 74, 2339–2364, doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.11.001 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nishitani Y & Matsumoto H Ethanol rapidly causes activation of JNK associated with ER stress under inhibition of ADH. FEBS Lett 580, 9–14, doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.030 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elamin E et al. Ethanol impairs intestinal barrier function in humans through mitogen activated protein kinase signaling: a combined in vivo and in vitro approach. PLoS One 9, e107421, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107421 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.El-Mas MM, Fan M & Abdel-Rahman AA Role of rostral ventrolateral medullary ERK/JNK/p38 MAPK signaling in the pressor effects of ethanol and its oxidative product acetaldehyde. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 37, 1827–1837, doi: 10.1111/acer.12179 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tabakoff B, Animal PLH Animal models in alcohol research. Alcohol Res. Health 24 (2000). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilcox MV et al. Repeated binge-like ethanol drinking alters ethanol drinking patterns and depresses striatal GABAergic transmission. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 579–594, doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.230 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thiele TE & Navarro M "Drinking in the dark" (DID) procedures: a model of binge-like ethanol drinking in non-dependent mice. Alcohol 48, 235–241, doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2013.08.005 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sherrin T et al. Hippocampal c-Jun-N-terminal kinases serve as negative regulators of associative learning. J Neurosci 30, 13348–13361, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3492-10.2010 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reinecke K, Herdegen T, Eminel S, Aldenhoff JB & Schiffelholz T Knockout of c-Jun N-terminal kinases 1, 2 or 3 isoforms induces behavioural changes. Behavioural brain research 245, 88–95, doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.02.013 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Clarke M, Pentz R, Bobyn J & Hayley S Stressor-like effects of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibition. Plos One 7, e44073, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044073 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ponomarev i. Epigenetic Control of Gene Expression in the Alcoholic Brain. AlcoholResearch 35, 69–76 (2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Manzardo AM, Henkhaus RS & Butler MG Global DNA promoter methylation in frontal cortex of alcoholics and controls. Gene 498, 5–12, doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.096 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhao R et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in discordant sib pairs with alcohol dependence. Asia Pac Psychiatry 5, 39–50, doi: 10.1111/appy.12010 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Witt SH et al. Acute alcohol withdrawal and recovery in men lead to profound changes in DNA methylation profiles: a longitudinal clinical study. Addiction, doi: 10.1111/add.15020 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bayerlein K et al. Orexin A expression and promoter methylation in patients with alcohol dependence comparing acute and protracted withdrawal. Alcohol 45, 541–547, doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.02.306 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Biermann T et al. N-methyl-D-aspartate 2b receptor subtype (NR2B) promoter methylation in patients during alcohol withdrawal. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 116, 615–622, doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0212-2 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Murgatroyd C et al. Dynamic DNA methylation programs persistent adverse effects of early-life stress. Nat Neurosci 12, 1559–1566, doi: 10.1038/nn.2436 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matosin N, Cruceanu C & Binder EB Preclinical and Clinical Evidence of DNA Methylation Changes in Response to Trauma and Chronic Stress. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 1, doi: 10.1177/2470547017710764 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sachin Moonat MS, Pandey Subhash C.,. Stress, Epigenetics, and Alcoholism. Alcohol research: current reviews 34, 495–505 (2012). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mehta D et al. Genomewide DNA methylation analysis in combat veterans reveals a novel locus for PTSD. Acta Psychiatr Scand 136, 493–505, doi: 10.1111/acps.12778 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kar S et al. An insight into the various regulatory mechanisms modulating human DNA methyltransferase 1 stability and function. Epigenetics 7, 994–1007, doi: 10.4161/epi.21568 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jurkowska RZ, Jurkowski TP & Jeltsch A Structure and function of mammalian DNA methyltransferases. Chembiochem 12, 206–222, doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000195 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jeltsch A & Jurkowska RZ New concepts in DNA methylation. Trends Biochem Scl 39, 310–318, doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.05.002 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhou R, Chen F, Chang F, Bai Y & Chen L Persistent overexpression of DNA methyltransferase 1 attenuating GABAergic inhibition in basolateral amygdala accounts for anxiety in rat offspring exposed perinatally to low-dose bisphenol A. J Psychiatr Res 47, 1535–1544, doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.05.013 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhu C et al. Involvement of Epigenetic Modifications of GABAergic Interneurons in Basolateral Amygdala in Anxiety-like Phenotype of Prenatally Stressed Mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 21, 570–581, doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyy006 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Morris MJ, Na ES, Autry AE & Monteggia LM Impact of DNMT1 and DNMT3a forebrain knockout on depressive- and anxiety like behavior in mice. Neuroblol Learn Mem 135, 139–145, doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.08.012 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Siciliano CA, Noamany H & Chang CJ A cortical-brainstem circuit predicts and governs compulsive alcohol drinking. Science 366, 1008–1012 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.