Abstract

Introduction:

The purposes of this research were to identify the buccolingual inclinations of the mandibular teeth and the mandibular symphysis remodeling that result from the orthodontic decompensation movement.

Methods:

The sample consisted of 30 adults with Class III dentofacial deformity, who had presurgical orthodontic treatment. Three-dimensional images were generated by cone-beam computed tomography scans at 2 different times (initial and before orthognathic surgery). Three-dimensional virtual models were obtained and superimposed using automated voxel-based registration at the mandible to evaluate B-point displacement, mandibular molar and incisor decompensation movement, and symphysis inclination and thickness. The 3-dimensional displacements of landmarks at the symphysis were quantified and visualized with color-coded maps using 3D Slicer (version 4.0; www.slicer.org) software.

Results:

The measurements showed high reproducibility. The patients presented mandibular incisor proclination, which was consistent with the movement of tooth decompensation caused by the presurgical orthodontic treatment. Statistically significant correlations were found between the inclination of the mandibular incisors, symphysis inclination, and B-point displacement. Regarding the thickness of the symphysis and the inclination of the incisors, no statistically significant correlation was found.

Conclusions:

The buccolingual orthodontic movement of the mandibular incisors with presurgical leveling is correlated with the inclination of the mandibular symphysis and repositioning of the B-point but not correlated to the thickness of the symphysis.

Class III dentofacial deformities are characterized by a maxillomandibular discrepancy, which can be treated by orthognathic surgery or, in less severe cases, by orthodontic compensation. The skeletal etiology of these conditions may include retruded position and/or deficient size of the maxillary jaw, protruded position and/or large size of the mandibular jaw, or a combination of both.1 The dentoalveolar characteristics of these conditions often present variable degrees of compensation that maintain occlusal function and mask the underlying skeletal discrepancy.2 Typically, the maxillary incisors are proclined, and the mandibular incisors are retroinclined.3,4

The conventional orthodontic-surgical treatment of Class III dentofacial deformities consists of 3 stages: presurgical orthodontics, surgery, and postsurgical orthodontics. Preoperative orthodontics in patients with Class III dentofacial deformities aim to decompensate the inclination of the maxillary and mandibular incisors, obtaining adequate dental inclinations in their respective bone bases. The presurgical orthodontic phase influences the magnitude of the movements obtained at surgery because the occlusion is used as a surgical guide. Therefore, the decompensation of the incisors is one of the main contributory factors for the overall esthetic and functional result.5–7

The envelope of tooth movement for achieving adequate decompensation is often complicated by neuromuscular function, occlusion, periodontal health, and thickness of the mandibular symphysis. The morphology of the mandibular symphysis is a complex phenotype that results from the interaction of different genetic, adaptive, and environmental factors. The size and shape of the mandibular symphysis are important in the assessment of orthodontic patients.8 With a wider symphysis, greater protrusion of the incisors is acceptable. However, a more elongated and narrow symphysis is generally associated with protrusion of the chin and increased lower anterior facial height.9,10 Patients with Class III malocclusions and increased vertical dimensions have predominantly narrow mandibular symphysis, with less alveolar bone at vestibular and lingual cortices of the mandibular incisors.11,12 In these patients, pronounced sagittal movement of the incisors is a critical factor for progressive buccal and lingual bone loss.3,11,13–15 The symphysis morphology serves as the primary reference for facial profile esthetics, as it determines the planning of the mandibular incisor position during orthodontic preparation for orthognathic surgery.16,17 Limiting the orthodontic movement of the incisor within the bone structure is essential for obtaining stable results and periodontal health.18

Before the introduction of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) in dentistry, buccolingual inclinations of the incisors were measured by lateral cephalograms.11,19,20 Because these exams show a 2-dimensional image of 3-dimensional (3D) areas, measurements in the symphysial region are susceptible to intrinsic errors. Errors in 2-dimensional measurements are due to overlap of anatomic structures, difficulties in identifying landmarks, and magnification errors caused by divergence of the radiation beam. With the advent of CBCT, precise evaluations of the dental inclinations and symphysis remodeling can guide the amount of dental decompensation possible in the orthodontic-surgical treatment of patients with Class III dentofacial deformities without possible deleterious effects to the periodontium.16,21,22 The 3D superimposition methodology of virtual models for the evaluation of results and treatment stability in Class III patients has been described in the orthodontic literature.23 The superimposition of stable mandibular structures can be used for growth, treatment, and stability assessment. Three-dimensional images can be superimposed or registered using thousands of points, shapes, or volumes allowing the evaluation based on the differences obtained directly in these images.24

The superimposition of 3D models and measurements of the distances between surfaces at different times can identify and quantify the values and the direction of changes.25

The envelope of the limits of planned orthodontic movement is an important factor to be considered in all orthodontic treatments, particularly in cases of dental decompensation before orthognathic surgery. To date, there are no 3D studies describing the alteration on symphysis remodeling after mandibular incisor decompensation in preparation for orthognathic surgery using 3D superimposition of virtual models. This study’s objective was to evaluate the 3D presurgical orthodontic changes in the mandibular incisors’ inclination and its relation to the symphysis remodeling. The null hypothesis was that dentoalveolar decompensation changes with presurgical orthodontic leveling are not correlated to the mandibular symphysis remodeling.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study sample consisted of 30 adult patients (mean age: 23 years and 4 months) with skeletal Class III malocclusion submitted to presurgical orthodontic treatment. The project was approved by the institutional review board under protocol 1.121.847, and informed consent was obtained from each patient before treatment. The inclusion criteria were skeletal Class III malocclusion characterized by an anterior crossbite or incisor edge-to-edge relationship, Class III molar relationship, and a concave facial profile. All patients had complete permanent dentition with periodontal health (absence of bleeding on probing and probing depths <3 mm), minimal to moderate crowding in the mandibular arch as stated by Little26 (≤6 mm), indication for orthodontic-surgical treatment, skeletal maturity, no previous orthodontic treatment, no extractions in the mandibular arch, and no local or general contraindications for surgery. Exclusion criteria were cleft lip or palate, missing teeth, previous orthodontic treatment, patients with severe crowding (>6 mm), and patients with both severe deepbite or overclosure with overeruption of mandibular incisors as well as open bite patients so that vertical correction would not lead to heterogeneity of leveling goals.

For sample size calculation, we considered a minimum correlation coefficient of 0.5, with a level of significance of 5% and statistical power of 80%. With these parameters, we reached a minimum sample size of 29 participants.

The patients’ average cephalometric features at baseline were as follows: ANB = −3.78° (±4.07), SNA = 82.18° (±3.44), SNB = 85.92° (±3.72), and IMPA = 81.92° (±8.5). All patients were treated orthodontically using active self-ligating straight-wire bracket system (GAC In-Ovation R, Dentsply GAC, NY) ensuing the following arch sequence: 0.012-in nickel-titanium (NiTi) thermo-activated, 0.016-in NiTi thermo-activated, 0.016 × 0.022-in NiTi thermo-activated, 0.019 × 0.025-in NiTi thermo-activated, and 0.019 × 0.025-in stainless steel. The wire sequence protocol, as well as the change periodicity, was well defined. The preestablished wire change at intervals of 2 months was performed if mechanical targets were obtained. The archwire change protocol took into account the residual deflection and the possibility of introducing the subsequent wire without great difficulties so that the forces of leveling and alignment were light.

CBCT scans were obtained before the beginning of the treatment (T1) and before surgery (T2). Both scans were acquired using a ProMax 3D machine (Planmeca, Helsinki, Finland) with a12.52-second scan time and a 23 × 26-cm field of view, with a voxel dimension of 0.4 mm. The data from each CBCT scan were saved as digital imaging and communications in medicine files. Segmentations of the CBCT volumes were performed using open-source software, ITK-SNAP, version 2.4.0 (www.itksnap.org). The initial (T1) and presurgical (T2) 3D models were created, oriented to obtain a common coordinate system, approximated having as reference the best fit of the contours of the mandibular body in multiplanar cross-sections, and superimposed using the automated voxel-based registration on the mandible of the 3D SlicerCMF (version 4.0) software (www.slicer.org). These image analysis procedures made possible the evaluation of the changes in symphysis inclination and thickness and the mandibular incisor decompensation movements that resulted from the presurgical orthodontic treatment.

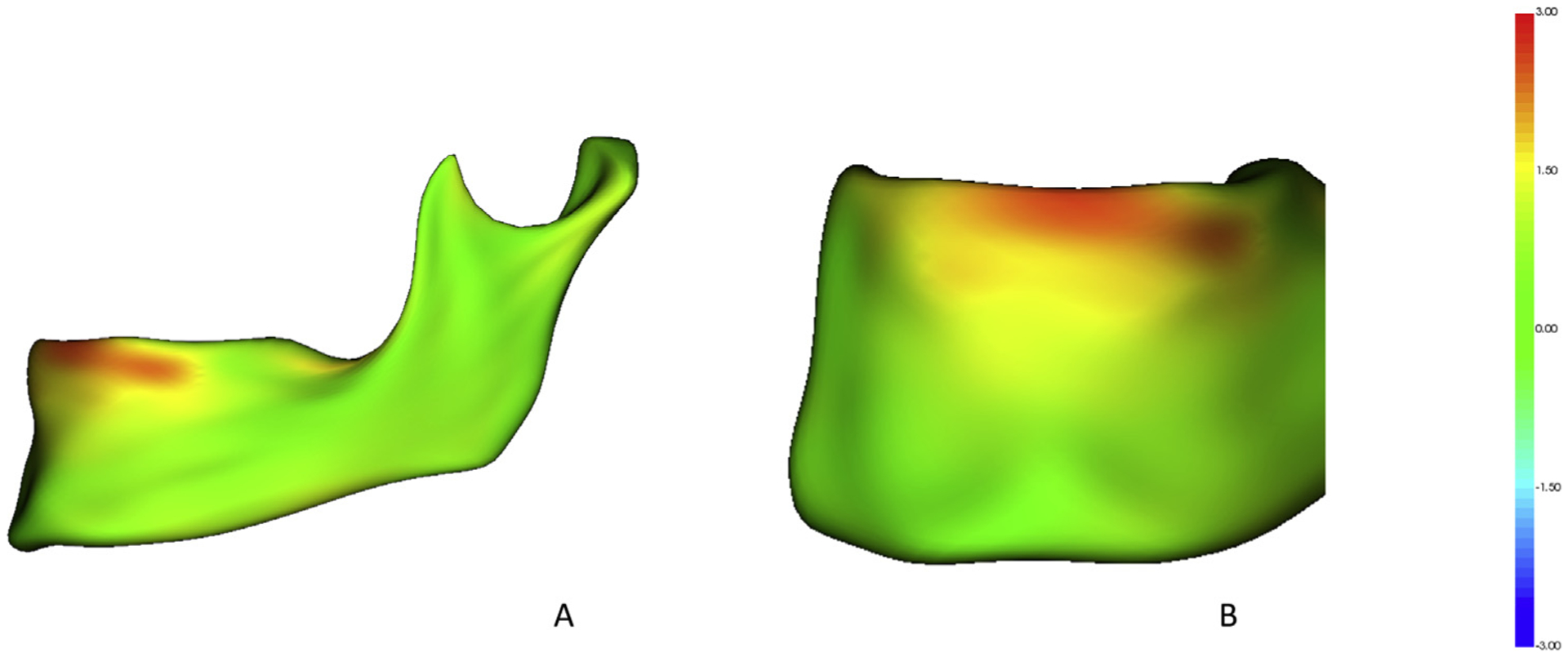

Qualitative assessments of treatment response were visualized using color-coded maps (Fig 1). Distances of corresponding surfaces were graphically displayed by the magnitude of the distance coded by color. Distance maps provided the magnitude of changes between 2 corresponding models (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Color maps of distances of the T1 and T2 models for a patient that represents this study data. The color map scale is set from −3 to +13 mm. Green color indicates no displacement between models. Red represents the anterior displacement of T2 relative to the T1 model: A, sagittal view; B, coronal view.

Quantitative assessments were calculated using and point-to-point landmark identification. Landmarks selected for this study were the following: first molars crown and root, incisal edge and root apex, B-point, pogonion, menton, gonion, pogonion at lingual cortical plate of the symphysis, and B-point at lingual cortical plate of the symphysis (Supplementary Fig 1) (Table I). Landmarks were prelabeled at T1 and T2 registered scans27 and the landmarks were then identified in 3D surface models using the 3D Slicer Q3DC (Quantification of 3D Components) tool (3D Slicer version 4.0). The following linear and angular measurements were calculated: (1) B-point displacement (distance between B-point at T1 and T2 in mm), (2) distance between first molar crowns at T1 and T2 (mm), (3) incisor inclination (pitch)(°), (4) molar inclination (roll)(°), (5) symphysis inclination (angle formed by B-point, pogonion, menton, and midpoint between the gonion) and (6) symphysis thickness (measured at B-point and pogonion in millimeters) (Supplementary Figs 2 and 3).

Table I.

Description of landmarks

| Landmarks | Description |

|---|---|

| Right first molar crown | Point located at the tip of the mesiobuccal cusp |

| Left first molar crown | |

| Right first molar root | Point located at the apex of the root of the first molar |

| Left first molar root | |

| Right central incisor crown | Point located at the tip of the incisal edge of the central incisor |

| Left central incisor crown | |

| Right central incisor root | Point located at the apex of the root of the central incisor |

| Left central incisor root | |

| B-point | Deepest point of the anterior alveolar process of the mandible |

| Pogonion | Most anterior point of the contour of the mandibular symphysis |

| Menton | Lowest point of the contour of the mandibular symphysis |

| Right gonion | Point determined by the bisector of the angle formed by the mandibular plane and the tangent to the posterior border of the ascending ramus of the mandible |

| Left gonion | |

| Pogonion at lingual cortical | Most posterior point located in the external lingual cortical of mandibular symphysis |

| B-point at lingual cortical | Point corresponding to the B-point demarcated at the lingual cortex of the symphysis |

| Midpoint between the gonion | Point demarcated by the software as the midpoint between the right and left gonion |

The point-to-point measurements are reported as 3D distances and their lateral (x), anteroposterior (y), and vertical (z) components. The 3D landmark point-to-point changes were decomposed into the 3 axes to provide more precise information regarding the number of changes in each direction. For the y-axis, positive values indicated anterior displacement, and negative values indicated posterior displacement. For the z-axis, positive values indicated superior displacement, and negative values indicated inferior displacement.28

Statistical analysis

As the Anderson-Darling test determined the normal distribution of the data, parametric tests were used. Descriptive analysis was used to describe the means, standard deviations, and ranges values at T1 and T2 for the following measurements: B-point displacement, incisor and molar inclination, molar crown distances, and symphysis inclination and thickness.

Pearson correlation tests were performed to evaluate the correlations between mandibular incisor inclination and symphysis inclination and thickness, and the correlations between mandibular incisor inclination and B-point displacement. The intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated with the respective 95% confidence intervals to evaluate the systematic error. To compare the measures of thickness of the symphysis between T1 and T2, the paired Student t test was used. The level of significance was set at 5%, and MedCalc was used for statistical analysis (version 18.6; MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

RESULTS

The descriptive statistics are summarized in Table II.

Table II.

Description of measurements

| Variable | n | Mean | SD | 95% Confidence interval | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-point displacement (3D) total | 30 | 1.2399 | 0.9771 | 0.8750 to 1.6047 | 0.2530 | 4.8120 |

| B-point displacement (AP) <0 | 22 | −0.6257 | 0.5485 | −0.8689 to −0.3825 | −1.8270 | −0.0150 |

| B-point displacement (AP) ≥0 | 8 | 0.3359 | 0.3048 | 0.08105 to 0.5907 | 0.0000 | 0.8940 |

| B-point displacement (AP) total | 30 | −0.3693 | 0.6537 | −0.6134 to −0.1252 | −1.8270 | 0.8940 |

| B-point displacement (SI) <0 | 8 | −0.4724 | 0.2456 | −0.6777 to −0.2670 | −0.7400 | −0.0580 |

| B-point displacement (SI) ≥0 | 22 | 0.9957 | 1.0564 | 0.5273 to 1.4641 | 0.0380 | 4.3150 |

| B-point displacement (SI) total | 30 | 0.6042 | 1.1219 | 0.1853 to 1.0231 | −0.7400 | 4.3150 |

| Right central incisor pitch <0 | 26 | −8.6980 | 6.4232 | −11.2924 to −6.1036 | −26.9150 | −1.3510 |

| Right central incisor pitch ≥0 | 4 | 2.6862 | 1.7659 | −0.1237 to 5.4962 | 0.9830 | 4.2960 |

| Right central incisor pitch total | 30 | −7.1801 | 7.1681 | −9.8567 to −4.5034 | −26.9150 | 4.2960 |

| Left central incisor pitch <0 | 25 | −10.2263 | 6.9698 | −13.1033 to −7.3493 | −24.6350 | −0.6320 |

| Left central incisor pitch ≥0 | 5 | 2.0058 | 1.1671 | 0.5567 to 3.4549 | 0.2560 | 3.2360 |

| Left central incisor pitch total | 30 | −8.1876 | 7.8669 | −11.1252 to −5.2501 | −24.6350 | 3.2360 |

| Right first molar roll <0 | 19 | 7.1663 | 4.1393 | −9.1614 to −5.1712 | −17.8110 | −1.4310 |

| Right first molar roll ≥0 | 11 | 3.5631 | 1.6176 | 2.4764 to 4.6498 | 0.6880 | 5.8710 |

| Right first molar roll total | 30 | 3.2322 | 6.2604 | −5.5699 to −0.8945 | −17.8110 | 5.8710 |

| Left first molar roll <0 | 9 | 3.0900 | 2.9722 | −5.3746 to −0.8054 | −8.8320 | −0.3250 |

| Left first molar roll ≥0 | 21 | 5.6302 | 3.8870 | 3.8609 to 7.3996 | 0.0510 | 13.2580 |

| Left first molar roll total | 30 | 3.0142 | 5.4200 | 0.9903 to 5.0380 | −8.8320 | 13.2580 |

| Right first molar crown distances (3D) total | 30 | 2.0164 | 1.2936 | 1.5334 to 2.4995 | 0.2180 | 5.0570 |

| Right first molar crown distances (SI) <0 | 8 | −0.4350 | 0.3768 | −0.7500 to −0.1200 | −0.8690 | −0.0270 |

| Right first molar crown distances (SI) ≥0 | 22 | 0.8592 | 0.7237 | 0.5383 to 1.1800 | 0.0020 | 2.7620 |

| Right first molar crown distances (SI) total | 30 | 0.5141 | 0.8674 | 0.1902 to 0.8380 | −0.8690 | 2.7620 |

| Left first molar crown distances (3D) total | 30 | 1.8720 | 1.0377 | 1.4845 to 2.2595 | 0.2950 | 4.5080 |

| Left first molar crown distances (SI) <0 | 10 | −0.6798 | 0.4306 | −0.9878 to −0.3718 | −1.6390 | −0.2980 |

| Left first molar crown distances (SI) ≥0 | 20 | 0.8942 | 0.8706 | 0.4867 to 1.3016 | 0.0690 | 2.9740 |

| Left first molar crown distances (SI) total | 30 | 0.3695 | 1.0600 | −0.02632 to 0.7653 | −1.6390 | 2.9740 |

| Symphysis inclination (T1) <0 | 30 | 126.6890 | 7.0461 | −129.3201 to −124.0580 | −138.8280 | −111.6480 |

| Symphysis inclination (T2) <0 | 30 | 126.1229 | 7.6512 | −128.9799 to −123.2658 | −138.9520 | −106.9970 |

| Symphysis thickness (Pog) (3D) total | 30 | 13.8732 | 2.0126 | 13.1217 to 14.6247 | 9.5890 | 18.3340 |

| Symphysis thickness (Pog) (AP) total | 30 | −13.8622 | 2.0140 | −14.6143 to −13.1102 | −18.3290 | −9.5860 |

| Symphysis thickness T1 (B) (3D) total | 30 | 7.1186 | 1.8659 | 6.4219 to 7.8153 | 4.4190 | 10.9980 |

| Symphysis thickness T1 (B) (AP) total | 30 | −7.1006 | 1.8760 | −7.8011 to −6.4001 | −10.9950 | −4.3020 |

| Symphysis thickness T2 (B) (3D) total | 30 | 6.8608 | 2.2632 | 6.0157 to 7.7059 | 3.6180 | 12.2220 |

| Symphysis thickness T2 (B) (AP) total | 30 | −6.8406 | 2.2698 | −7.6881 to −5.9930 | −12.2200 | −3.5910 |

SD, Standard deviation; AP, anteroposterior (horizontal direction); SI, superior-inferior (vertical direction).

The majority of patients (n = 22) presented displacement of the B-point in a posterior direction (mean, 0.62 mm) and in an inferior, clockwise direction (mean, 0.99 mm), whereas 8 patients presented displacement of the B-point in an anterior direction (mean, 0.33 mm) and in a superior, counterclockwise direction (mean, 0.47 mm). In addition, most of the patients presented the proclination of the mandibular incisors (mean, 8.69°) (Fig 1).

Most of the patients presented uprighting of the mandibular first right and left molar, correcting their lingual inclination (average of 7.16 and 5.63, respectively). In the vertical direction, the mandibular molars presented a small amount of extrusion during the treatment (mean of 0.85 mm in the right molar and 0.89 mm in the left molar).

The mean values of symphysis inclination and thickness (at B-point and pogonion) were also described (Table II).

There was no statistically significant difference between the right and left incisors (P = 0.1554), but a statistically significant difference was observed between the left and mandibular right molars (P = 0.0035). Therefore, only the right side incisors were reported in the statistical analysis, but the molars on both sides were reported (Table III).

Table III.

Comparison between right and left incisors and molars and results from the paired Student t test

| Right | Left | Mean difference | 95% Confidence interval | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Mandibular incisor | −7.1801 | 7.1681 | −8.1876 | 7.8669 | −1.0076 | −2.4201 to 0.4050 | 0.1554 |

| Mandibular first molar | 3.2322 | 6.2604 | 3.0142 | 5.4200 | 6.2464 | 2.2256 to 10.2671 | 0.0035 |

SD, Standard deviation.

Moderate and statistically significant correlations were observed between the inclination of the mandibular incisor and the inclination of the symphysis. (Table IV).

Table IV.

Correlations between mandibular incisor inclination and symphysis morphologic characteristics (T1 and T2)

| Right incisor inclination | n | Correlation | P Value | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symphysis inclination (T1) | 30 | 0.5213 | 0.0031 | 0.1983 to 0.7422 |

| Symphysis thickness at B-point (AP) (T1) | 30 | −0.1023 | 0.5907 | −0.4461 to 0.2679 |

| Symphysis thickness at B-point (3D) (T1) | 30 | 0.1023 | 0.5907 | −0.2679 to 0.4461 |

| Symphysis inclination (T2) | 30 | 0.5039 | 0.0045 | 0.1755 to 0.7314 |

| Symphysis thickness at B-point (AP) (T2) | 30 | −0.2437 | 0.1943 | −0.5553 to 0.1278 |

| Symphysis thickness at B-point (3D) (T2) | 30 | 0.2427 | 0.1962 | −0.1288 to 0.5545 |

| B-point displacement (AP) | 30 | 0.5041 | 0.0045 | 0.1757 to 0.7315 |

| B-point displacement (SI) | 30 | −0.6008 | 0.0004 | −0.7900 to −0.3069 |

| B-point displacement (3D) | 30 | −0.6782 | <0.0001 | −0.8346 to −0.4208 |

AP, anteroposterior; SI, superior-inferior.

No statistically significant linear correlation was found between the thickness of the symphysis and the inclination of the mandibular incisor (P >.0.05) (Table IV). The comparisons between T1 and T2 for the symphysis thickness did not present statistically significant differences (Table V).

Table V.

Comparison between times and results from the paired Student t test

| T 1 | T2 | Mean difference | 95% Confidence interval | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Symphysis thickness (B) (AP) | −7.1006 | 1.8760 | −6.8406 | 2.2698 | 0.2600 | −0.07031 to 0.5903 | 0.1183 |

| Symphysis thickness (B) (3D) | 7.1186 | 1.8659 | 6.8608 | 2.2632 | −0.2578 | −0.5876 to 0.07191 | 0.1206 |

SD, Standard deviation; AP, anteroposterior.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, a longitudinal assessment of presurgical decompensation of the mandibular arch was evaluated using mandibular regional voxel-based registration. This automated voxel-based registration does not depend on how precisely the 3D volumetric label maps represent the anatomic truth nor on the location of a limited number of landmarks.29,30 After the regional registration in the mandible, we have quantitatively assessed the 3D displacement of the B-point, changes in the inclination of mandibular incisors and mandibular molars, arch width between the crowns of the mandibular molars, and the mandibular symphysis inclination and thickness.

The change in the inclination of the mandibular incisors (pitch) in this study revealed a mean proclination of 8.69°. This finding is within the range of changes in the IMPA measurement reported in Class III surgical decompensation literature that varied from 5° to 14°.6,31–35 Considering that the present study inclusion criteria were less than 6 mm crowding in the mandibular arch, and the sample presented an average IMPA of 81.92° ± 8.5° at baseline, the changes observed in the mandibular incisors buccolingual inclination represent decompensation of their retroclination, similarly to the results reported by Kim and Baek.36

Buccolingual inclinations of the posterior teeth are critical for establishing an ideal occlusion. The maxillomandibular transverse discrepancy commonly seen in skeletal Class III malocclusions can be due to maxillary deficiency and/or mandible protrusion and the associated low tongue posture. These patients often present transverse dental compensations with lingual inclination of the posterior teeth. The presurgical compensation in this present study revealed an average of 7.16 and 5.63, respectively, uprighting the right and left molars to obtain the appropriate cusp-fossa occlusion. The vertical mandibular molar movement with the slight extrusion observed in our study occurred because of dental decompensation of the mandibular posterior teeth, simultaneously to the clockwise rotation of the mandible observed in these patients. The present study findings are in agreement with the study by Song et al.37

Importantly, the morphology, both size and shape,8 of the mandibular symphysis serves as a primary reference for facial profile esthetics and determines the planning of the position of the mandibular incisors during orthognathic surgery. During orthodontic treatment, limiting the movement of the incisor within the trabecular bone structure is essential for obtaining better results, stability, and periodontal health.18 In the present study, the symphysis inclination, measured by B-point, pogonion, menton, and midpoint between the gonion, remained stable. The total thickness of the symphysis was measured in 2 regions: (1) from the B-point located in the buccal cortical to the B-point projected in the lingual cortical; and (2) from the pogonion located in the buccal cortical to the pogonion projected in the lingual cortical. In both regions, the comparisons between the initial and presurgical time points did not present statistically significant differences in the measures of thickness of the symphysis.

The moderate significant correlation found between the symphysis inclination and the mandibular incisors inclination indicated that the proclination of the incisors, in the presurgical orthodontic treatment, can alter the symphysis inclination. The null hypothesis was rejected (P <0.05) because a statistically significant linear and direct correlation between the calculated measures was found, which means that the greater the inclination of the mandibular incisors, the greater the inclination of the symphysis. This result is consistent with Al-Khateeb et al,13 who found a weak but significant correlation between mandibular incisor inclination and mandibular symphysis inclination measured at B-point. Other studies38,39 reported stronger correlations between these 2 parameters; however, different reference points were used to measure symphysis inclination. The thickness of the symphysis, measured at B-point and pogonion, was not statistically significantly correlated to the inclination of the incisors, as the change of the mandibular incisors inclination because of presurgical orthodontic treatment did not alter the thickness of the symphysis.

The majority of the patients presented displacement of the B-point in the posterior direction, which was significantly correlated with the proclination of the mandibular incisors. As the dental root apices move in a posterior direction, B-point also moves in the same direction. In addition, with leveling the curve of Spee, the vertical movement of the incisors was statistically correlated to changes in the position of B-point in the same direction (mean, 0.99 mm). The inclination of the mandibular incisors was also correlated with the 3D displacement of the B-point.

Dental decompensation should be carried out with caution to avoid the occurrence of dehiscences and fenestrations during orthodontic preparation for surgery orthognathic, particularly considering the thin buccal and lingual, alveolar bone thicknesses around the mandibular incisor roots (Fig 2).40–42 In summary, the buccolingual orthodontic movement of the mandibular incisors with presurgical leveling is correlated with the inclination of the mandibular symphysis and repositioning of the B-point, but not correlated to the thickness of the symphysis. These correlations provide valuable diagnostic information to treatment plan the limits of dental movements.

Fig 2.

Image of the mandibular incisor and corresponding alveolar socket.

CONCLUSIONS

The B-point displacement occurred in a posterior and superior direction.

The presurgical orthodontic treatment in subjects with Class III dentofacial deformities resulted in the proclination of the mandibular incisors and uprighting and extrusion of the mandibular molars.

Statistically significant correlations were found between the inclination of the mandibular incisors and the measurements of symphysis inclination and B-point displacement. The thickness of the symphysis was not significantly correlated to the inclination of the incisors.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.12.020.

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and none were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pereira-Stabile CL, Ochs MW, de Moraes M, Moreira RW. Preoperative incisor inclination in patients with Class III dentofacial deformities treated with orthognathic surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012;50:533–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperry TP, Speidel TM, Isaacson RJ, Worms FW. The role of dental compensations in the orthodontic treatment of mandibular prognathism. Angle Orthod 1977;47:293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guedes FP, Capelozza Filho L, Garib DG, Nary Filho H, Borgo EJ, Cardoso Mde A. Impact of orthodontic decompensation on bone insertion. Case Rep Dent 2014;2014:341752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molina-Berlanga N, Llopis-Perez J, Flores-Mir C, Puigdollers A. Lower incisor dentoalveolar compensation and symphysis dimensions among Class I and III malocclusion patients with different facial vertical skeletal patterns. Angle Orthod 2013;83:948–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNeil C, McIntyre GT, Laverick S. How much incisor decompensation is achieved prior to orthognathic surgery? J Clin Exp Dent 2014;6:e225–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun B, Tang J, Xiao P, Ding Y. Presurgical orthodontic decompensation alters alveolar bone condition around mandibular incisors in adults with skeletal Class III malocclusion. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8:12866–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn HW, Seo DH, Kim SH, Park YG, Chung KR, Nelson G. Morphologic evaluation of dentoalveolar structures of mandibular anterior teeth during augmented corticotomy-assisted decompensation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2016;150:659–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Closs LQ, Bortolini LF, dos Santos-Pinto A, Rösing CK. Association between post-orthodontic treatment gingival margin alterations and symphysis dimensions. Acta Odontol Latinoam 2014;27: 125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aki T, Nanda RS, Currier GF, Nanda SK. Assessment of symphysis morphology as a predictor of the direction of mandibular growth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1994;106:60–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan JY, Chou ST, Chang HP, Liu PH. Morphometric analysis of the mandible in subjects with Class III malocclusion. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2006;22:331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handelman CS. The anterior alveolus: its importance in limiting orthodontic treatment and its influence on the occurrence of iatrogenic sequelae. Angle Orthod 1996;66:95–109: discussion 109–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lombardo L, Berveglieri C, Spena R, Siciliani G. Quantitative cone-beam computed tomography evaluation of premaxilla and symphysis in Class I and Class III malocclusions. Int Orthod 2016;14: 143–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Khateeb SN, Al Maaitah EF, Abu Alhaija ES, Badran SA. Mandibular symphysis morphology and dimensions in different anteroposterior jaw relationships. Angle Orthod 2014;84: 304–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lines PA, Steinhauser EW. Diagnosis and treatment planning in surgical orthodontic therapy. Am J Orthod 1974;66:378–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proffit WR, Ackerman JL. Diagnosis and treatment planning In: Graber TM, Swain BF, editors. Current orthodontic concepts and techniques. St Louis: Mosby; 1982. p. 3–100. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YI, Choi YK, Park SB, Son WS, Kim SS. Three-dimensional analysis of dental decompensation for skeletal Class III malocclusion on the basis of vertical skeletal patterns obtained using cone-beam computed tomography. Korean J Orthod 2012;42:227–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koerich L, Ruellas AC, Paniagua B, Styner M, Turvey T, Cevidanes LH. Three-dimensional regional displacement after surgical-orthodontic correction of Class III malocclusion. Orthod Craniofac Res 2016;19:65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung CJ, Jung S, Baik HS. Morphological characteristics of the symphyseal region in adult skeletal Class III crossbite and openbite malocclusions. Angle Orthod 2008;78:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards JG. A study of the anterior portion of the palate as it relates to orthodontic therapy. Am J Orthod 1976;69:249–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong H, Enciso R, Van Elslande D, Major PW, Sameshima GT. A new method to measure mesiodistal angulation and faciolingual inclination of each whole tooth with volumetric cone-beam computed tomography images. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2012;142:133–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu Q, Pan XG, Ji GP, Shen G. The association between lower incisal inclination and morphology of the supporting alveolar bone-a cone-beam CT study. Int J Oral Sci 2009;1:217–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gracco A, Luca L, Bongiorno MC, Siciliani G. Computed tomography evaluation of mandibular incisor bony support in untreated patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2010;138:179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cevidanes LH, Bailey LJ, Tucker SF, Styner MA, Mol A, Phillips CL, et al. Three-dimensional cone-beam computed tomography for assessment of mandibular changes after orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007;131:44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruellas AC, Yatabe MS, Souki BQ, Benavides E, Nguyen T, Luiz RR, et al. 3D mandibular superimposition: comparison of regions of reference for voxel-based registration. PLoS One 2016;11: e0157625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paniagua B, Cevidanes L, Zhu H, Styner M. Outcome quantification using SPHARM-PDM toolbox in orthognathic surgery. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg 2011;6:617–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Little RM. The irregularity index: a quantitative score of mandibular anterior alignment. Am J Orthod 1975;68:554–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruellas AC, Huanca Ghislanzoni LT, Gomes MR, Danesi C, Lione R, Nguyen T, et al. Comparison and reproducibility of 2 regions of reference for maxillary regional registration with cone-beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2016;149:533–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atresh A, Cevidanes LHS, Yatabe M, Muniz L, Nguyen T, Larson B, et al. Three-dimensional treatment outcomes in Class II patients with different vertical facial patterns treated with the Herbst appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2018;154:238–48.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cevidanes LH, Styner MA, Proffit WR. Image analysis and superimposition of 3-dimensional cone-beam computed tomography models. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006;129:611–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cevidanes LH, Ruellas AC, Jomier J, Nguyen T, Pieper S, Budin F, et al. Incorporating 3-dimensional models in online articles. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2015;147(Suppl 5):S195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahn HW, Baek SH. Skeletal anteroposterior discrepancy and vertical type effects on lower incisor preoperative decompensation and postoperative compensation in skeletal Class III patients. Angle Orthod 2011;81:64–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang B, Shen G, Fang B, Yu H, Wu Y. Augmented corticotomy-assisted presurgical orthodontics of Class III malocclusions: a cephalometric and cone-beam computed tomography study. J Craniofac Surg 2013;24:1886–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coscia G, Coscia V, Peluso V, Addabbo F. Augmented corticotomy combined with accelerated orthodontic forces in Class III orthognathic patients: morphologic aspects of the mandibular anterior ridge with cone-beam computed tomography. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013;71:1760.e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang B, Shen G, Fang B, Yu H, Wu Y, Sun L. Augmented corticotomy-assisted surgical orthodontics decompensates lower incisors in Class III malocclusion patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014;72:596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi YJ, Chung CJ, Kim KH. Periodontal consequences of mandibular incisor proclination during presurgical orthodontic treatment in Class III malocclusion patients. Angle Orthod 2015;85:427–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim DK, Baek SH. Change in maxillary incisor inclination during surgical-orthodontic treatment of skeletal Class III malocclusion: comparison of extraction and nonextraction of the maxillary first premolars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2013;143:324–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song HS, Choi SH, Cha JY, Lee KJ, Yu HS. Comparison of changes in the transverse dental axis between patients with skeletal Class III malocclusion and facial asymmetry treated by orthognathic surgery with and without presurgical orthodontic treatment. Korean J Orthod 2017;47:256–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellis E 3rd, McNamara JA Jr. Components of adult Class III malocclusion. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1984;42:295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamada C, Kitai N, Kakimoto N, Murakami S, Furukawa S, Takada K. Spatial relationships between the mandibular central incisor and associated alveolar bone in adults with mandibular prognathism. Angle Orthod 2007;77:766–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sendyk M, de Paiva JB, Abrão J, Rino Neto J. Correlation between buccolingual tooth inclination and alveolar bone thickness in subjects with Class III dentofacial deformities. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2017;152:66–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holmes PB, Wolf BJ, Zhou J. A CBCT atlas of buccal cortical bone thickness in interradicular spaces. Angle Orthod 2015;85:911–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masumoto T, Hayashi I, Kawamura A, Tanaka K, Kasai K. Relationships among facial type, buccolingual molar inclination, and cortical bone thickness of the mandible. Eur J Orthod 2001;23: 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.