Abstract

The Institute of Medicine reports lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) individuals having the highest rates of tobacco, alcohol and drug use leading to elevated cancer risks. Due to fear of discrimination and lack of healthcare practitioner education, LGBT patients may be more likely to present with advanced stages of cancer resulting in suboptimal palliative care. The purpose of this scoping review is to explore what is known from the existing literature about the barriers to providing culturally competent cancer-related palliative care to LGBT patients. This review will use the five-stage framework for conducting a scoping review developed by Arksey and O’Malley. The PubMed, Scopus, PsychINFO and Cochrane electronic databases were searched resulting in 1,442 citations. Eligibility criteria consisted of all peer-reviewed journal articles in the English language between 2007 and 2020 resulting in 10 manuscripts. Barriers to palliative cancer care for the LGBT include discrimination, criminalisation, persecution, fear, distress, social isolation, disenfranchised grief, bereavement, tacit acknowledgment, homophobia and mistrust of healthcare providers. Limited healthcare-specific knowledge by both providers and patients, poor preparation of legal aspects of advanced care planning and end-of-life care were underprovided to LGBT persons. As a result of these barriers, palliative care is likely to be provided for LGBT patients with cancer in a deficient manner, perpetuating marginalisation and healthcare inequities. Minimal research investigates these barriers and healthcare curriculums do not provide practitioners skills for administering culturally sensitive palliative care to LGBT patients.

Keywords: cancer, LGBT, palliative care, scoping review

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

According to the Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Leading Health Indicators for Healthy People 2020, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) individuals have the highest rates of tobacco, alcohol and drug use (Committee on Leading Health Indicators for Healthy People, 2020, Board on Population Health, and Public Health Practice, & Institute of Medicine, 2012). These substances are known contributors to elevated cancer risks, leaving LGBT populations at a higher risk for developing certain cancers. While it is estimated that over one million LGBT persons are living with cancer in the United States (Bonvicini, 2017; Burkhalter et al., 2016; Gates, 2017), research has found that LGBT patients have a decreased likelihood of presenting for routine cancer screening (Bristowe et al., 2018; Clark, Landers, Linde, & Sperber, 2001; Stein & Bonuck, 2001). Since LGBT persons are less likely to seek cancer screening, they may be more likely to present with advanced staged cancer and with increased complications necessitating palliative care services at initial presentation (National LGBT Cancer Network, 2013).

The American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine describes palliative care as an improvement in one’s quality of life by managing symptoms associated with a serious illness (Medicine AAoHaP). Quality of life is determined by individuals and differs between patients but is an essential concept for healthcare providers to identify for all patients to provide excellent palliative care (Dibble, Roberts, Robertson, & Paul, 2002). The establishment of trust between the provider and patient allows for meaningful discussions; therefore, it is critical for palliative care providers to understand the specific vulnerabilities LGBT patients face and create a safe environment for sexual orientation and gender identification (SOGI) disclosure (Dibble et al., 2002). Issues that may differ between heterosexual/cisgender patients and LGBT patients include familial constructs for advanced care planning (ACP) and/or legal documents, the linguistics of addressing caregivers, generational differences among LGBT persons, considerations of sexual orientation in care, maintaining an affirmative, non-judgmental approach and partner bereavement support.

Among the total US population, an overall decrease in mortality from cancer allows individuals to live longer with cancer as a chronic condition (Curtin, 2019). Healthcare providers (HCPs) must be prepared to offer individualised education and understanding care to LGBT individuals. However, current research indicates healthcare trainees (physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, nurses’ aides) are not prepared to provide individualised care towards individuals of the LGBT population (Obedin-Maliver et al., 2011). On average, throughout all undergraduate healthcare training, 0–5 hr are spent on LGBT discrimination and healthcare disparities with varied topics addressed (Obedin-Maliver et al., 2011). It is essential to collect both qualitative and quantitative data allowing providers to better understand the psychological, spiritual and emotional needs of LGBT patients with cancer who present for palliative care. An exploration of heteronormative stigma, microaggressions and biases that HCPs may hold can be identified to guide clinical practice. With this breadth of knowledge, healthcare, in-line with the basic nature of palliative care, may be provided proficiently (Harding, Epiphaniou, & Chidgey-Clark, 2012).

Unfortunately, limited research exits outlining cancer disparities due to lack of routine collection of SOGI data not routinely collected in LGBT populations. A review of articles addressing LGBT healthcare conducted in 2002 showed only 0.1% of all articles in PubMed addressed LGBT health-related subject matter (Bonvicini, 2017). By 2011, a slight increase had occurred but still only 0.3% of all publications pertained to LGBT healthcare (Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, Board on the Health of Select Populations, & Institute of Medicine, 2011). Of those, even fewer pertained to palliative care in the LGBT oncology population. Given the limited evidence that has been conducted, additional studies should explore this gap to guide new research addressing persistent disparities.

The Institute of Multigenerational Health in The Aging in Health Report states that 68% of LGBT persons over the age of 65 have experienced some type of verbal harassment due to their sexual orientation, 43% have been threatened with violence and 82% have been victimised at some point in their lives (American Geriatrics Society Ethics Committee, 2015; National LGBT Cancer Network, 2013). Discrimination, refusal of care, bias, erroneous assumptions and derogatory statements by HCPs towards LGBT persons have been reported in up to 70% of healthcare visits in the United States (American Geriatrics Society Ethics Committee, 2015; National LGBT Cancer Network, 2013). About 15% of LGBT persons have a fear of accessing healthcare outside of the LGBT community, 13% have been denied healthcare based on their sexual orientation gender identity (SOGI) status, 30% do not have a living will and 36% do not have an appointed healthcare proxy (Barrett & Wholihan, 2016). An average of 22% of transgender adults need healthcare but are unable to afford it due to financial constraints (Barrett & Wholihan, 2016).

1.1 ∣. Objective

The purpose of this scoping review is to investigate the current literature on LGBT experiences in cancer-related palliative care from both patient and provider perspectives through the lens of the Social Ecological Model (SEM). It is important to note that LGBT populations consist of several subgroups, but for the purpose of this article the umbrella term LGBT will be used. In addition, the distinction between sexual orientation and gender identification should be made. Sexual orientation refers to the gender an individual is attracted to while gender identification refers to the gender one chooses to align themselves with (Human Rights Campaign, 2018).

1.2 ∣. Theoretical framework

In the SEM adapted by McLeory et al., behaviour is influenced by a multitude of levels that include personal, environmental and physical factors, all of which impact human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988). For this scoping review, the following levels of interactions will be used to highlight behaviours of both LGBT persons and HCPs: intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional/organisational, historical/societal/cultural systems and global perspectives (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; McLeroy et al., 1988; Stokols, 1996). Within the SEM framework, changes occur at each level that affect the individual, leading to the development of self-perception and guidance of worldly perception (Kok, Gottlieb, Commers, & Smerecnik, 2008). This model was used to guide an analysis of the existing literature exploring social structures as well as societal behaviours, attitudes, views and their effects on LGBT patients in the context of palliative care in the cancer patient. In order to conduct this complex, layered review, a ‘dynamic interplay among persons, groups and their sociophysical milieus’ (Stokols, 1996) was the focus, including the multifaceted ways social constructs both influence and are influenced by the individual (McLeroy et al., 1988). Intrapersonal levels of influence include one’s own beliefs, attitudes, coping styles, personality, resiliency, past experiences, education, income, fear of HCP discrimination and internalised homophobia. Interpersonal levels include the perceptions held by others of LGBT patients which may include familial structures consisting of immediate, extended and created family; informal social networks, work relationships and physical living spaces. Institutional and organisational networks include school, additional family (may be both biological and created family), neighbourhoods in which the LGBT persons lives, LGBT centres, service persons within the neighbourhood such as mail carriers and sanitation workers, religious/spiritual networks consisting of leaders and fellow participants, healthcare institutions and providers, educational institutions and employers. The historical/societal or cultural level is comprised of the dominant beliefs of the culture in which the individual lives and the historical occurrences that have shaped those beliefs. These occurrences include legal incidents, movements incited by uprisings, guidelines and recommendations made by political leaders and consensus groups. Such events have either perpetuated discrimination, fear of judgment, verbal/emotional homophobic remarks, outright refusal of care, depression and feelings of hopelessness and substance abuse, or have provided freedom from these barriers (Burgard, Cochran, & Mays, 2005; Gruskin, Hart, Gordon, & Ackerson, 2001; Harding et al., 2012; Heffernan, 1998; McCabe, 2014; Ryan, Huggins, & Beatty, 1999; Stall, Greenwood, Acree, Paul, & Coates, 1999). Lastly, global perspectives are those levels outside of one’s own country of national origin that seek to shape a worldlier view of LGBT barriers to care and healthcare practitioners’ perspectives. Within these structures, influences upon the LGBT person that are negative in one area may have negative effects on other areas as well, contributing to stress and overall poor health outcomes (McLeroy et al., 1988).

2 ∣. METHODS

2.1 ∣. Search strategy

A scoping review was conducted to synthesise knowledge and identify key concepts in a systematic method (Colquhoun et al., 2014). This review used the five-stage framework for conducting a scoping review developed by Arksey and O’Malley (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). These stages are as follows: (1) Identifying the research question, (2) Identifying existing studies, (3) Selecting studies, (4) Charting the data and (5) Collating, summarising and reporting the results (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005).

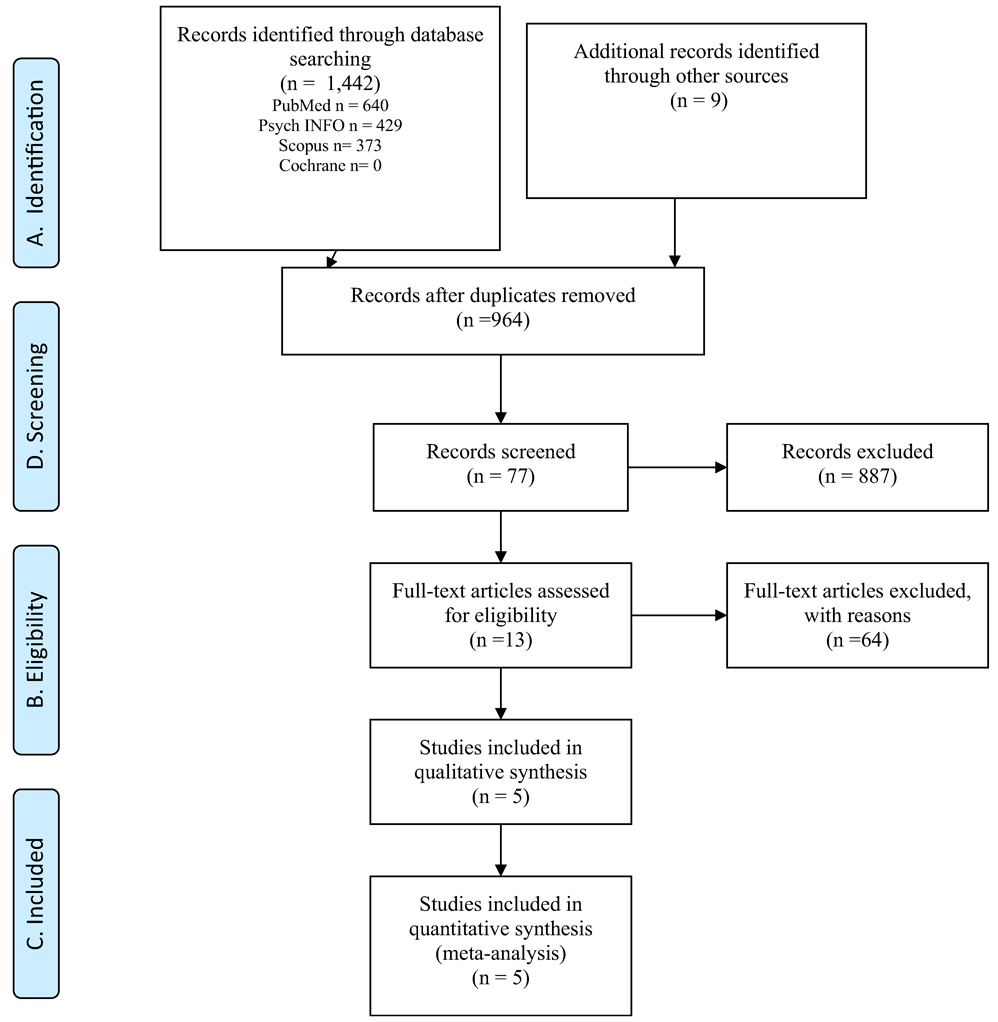

Stage 1 included an identification of the research question and was conducted prior to the literature search. Stage 2 was conducted with the assistance of a research and education librarian at a major medical university in the US Southeast. An exhaustive search was performed with inclusive search terms based on the scoping review question. The following terms were searched using Boolean operators: (‘sexual minorities’ OR ‘homosexuality’ OR ‘lesbian’ OR ‘gay’ OR ‘bisexual’ OR ‘transgender’ OR ‘transsexual’ OR ‘intersexual’ OR ‘homosexual’ OR ‘queer’ OR ‘non-heterosexual’) AND (‘end-of-life’ OR ‘oncology’ OR ‘cancer’ OR ‘hospice’ OR ‘palliative’) AND (‘perception’ OR ‘attitude of health personnel’ OR ‘attitude to health’ OR ‘attitudes’ OR ‘beliefs’ OR ‘barriers’ OR ‘discrimination’ OR ‘inequalities’ OR ‘disparities’ OR ‘homophobia’). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) diagram was used to transparently report the search results (Page & Moher, 2017; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

For stage 3, inclusion criteria consisted of peer-reviewed journal articles published in the English language that were relevant to palliative cancer care for LGBT populations during the years 2007 through 2020. The PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO and Cochrane databases were searched resulting in 1,372 citations. Inclusion criteria consisted of peer-reviewed journal articles published in the English language that were relevant to palliative cancer care for LGBT populations. Non-English language reports were excluded due to high cost of translation. A hand search was conducted for additional primary source reviews identifying three additional articles. Of the reviewed publications, 478 duplicates were removed leaving a total of 894 retrieved articles. Of the 894 articles identified, 23 relevant studies were selected by an initial review of titles followed by abstract review, eliminating 13 manuscripts that did not address palliative care information for the LGBT patient with cancer. Therefore, 10 manuscripts were chosen to address the scoping review question (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Literature matrix

| Study purpose/aims | Theory/framework/model | Setting | Sample description, size (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almack et al. (2010) | To explore how sexual orientation may impact concerns about and experiences of end-of- life care and bereavement within same-sex relationships | Disenfranchised grief (Doka, 1989:4) | United Kingdom - north and south of England | N = 15 of lesbian and gay elders |

| Bristowe et al. (2018) | To explore healthcare experiences of LGBT people facing advanced illness to elicit: views regarding sharing SOGI hx, accessing services, discrimination and exclusions and best practice examples to generate rec’s for improved care | Interactional or service level facilitators affect: Holistic care: physical, psychosocial, spiritual needs, support networks and relationships Create internalised/ invisible barriers and stressor shaping disclosure or exploration of identity |

United Kingdom | 40 LGBT persons facing advanced illness |

| Carabez and Scott (2016) | Aims from larger study: To explore the effectiveness of having trained students do structured interviews to learn about healthcare needs of LGBT pts. | Minority Stress model | US | N = 268 nurses living in the SF bay area, >18 yrs old, working in hospitals, community/public settings |

| To assess current state of LGBT-sensitive nursing practice | ||||

| Secondary analysis: Determine what difficulties nurses face regarding medical advance directives, POA, legal docs w/ LGBT pts. | ||||

| Hulbert-Williams et al. (2017) | To explore how the experiences of LGB patients with cancer differ from heterosexual patients | Epistemological explorative stance adopted standard alpha level of 0.05 | From the UK National Cancer Patient Experience Survey: Patients who receive cancer treatment in the UK | Take from the NCPES - 68,737 respondents |

| Hughes and Cartwright (2015) | To examine LGBT people’s attitudes to advance care planning (ACP) options and alternative decision-making at the end of life | None described | New South Wales, Australia | N = 305 LGBT persons |

| One state in Australia with suspected largest no. of LGBT people due to census data | ||||

| Study design | Data collection methods | Primary outcome variables | SEM levels addressed (or Theory application) | Results |

| Qualitative focus groups - narrative analysis written and verbal w/ focus on in-depth understanding of experiences in culture and context. Taken from larger study of 171 older people | 4 focus groups of LGB elders | Impact of sexual orientation on experiences and concerns about end-of-life care and on bereavement within same-sex relationships | Historical/societal level, interpersonal level, community level, organisational level | New/increasing possibilities of familial structure and some have social/material constraints of these, personal networks may grow smaller with age. Need to explore economic, social and cultural resources and how they shape later life experience of LGB people |

| Qualitative interview study; semi-structured in-depth interviews analysed using thematic analysis | Recruitment nationally through media and community networks through rural and urban locations | 5 themes: | States the data use Bronfenbrenner’s SEM theory and expand with an additional dimension of invisible barriers internalised by the individual results from multiple homophobic experiences across all systems | Need: public health approach to meet needs of LGBT people facing advanced illness, improvement of clinical care delivery to reduce fear/anxiety of discrimination - created 10 simple low-cost measures to implement |

| 1 - person centred care needs may be different for LGBT person | ||||

| 2 - service barriers/ stressors | ||||

| 3 - invisible barriers/ stressors | ||||

| 4 - service level, interactional facilitator | ||||

| 5 - all above shape patients’ preferences for disclosing identity | ||||

| Discrimination/exclusion still exists -> 10 rec’s made from data low cost and simple | ||||

| Qualitative face-to-face interviews to learn about the healthcare needs of LGBT patients recording both verbal and non-verbal responses | 45–75 min audiorecorded interviews at variety of locations. Asked 16 scripted questions developed from the HEI online survey | Heteronormative barriers held by RN’s can create discrimination of LGBT patients | Organisational level Community level | Inductive analysis: nurses become part of team in ACP; need to be further educated; school should incorporate LGBT training of ACP |

| Quantitative Secondary analysis; test and control for confounding effect of gender; multinomial logistic regression, logistic regression, applying postestimation probabilities using Wald test | Distributed annually to all patients who receive cancer care in the UK | Outcomes variable: Differences between LGB sexual minorities in the following areas: reporting cancer diagnosis, treatment decisions, relationship w/ healthcare professionals, after care, psychosocial care | Organisational level Supranational level | Discrimination of bisexual pts. versus. LG pts. slower to improve, marginalisation is from multiple sources; all have social isolation |

| Quantitative fixed-choice questions on-line or paper-based | Sent out 1,400 hardcopy surveys to members of LGBT community - Gender Centre, Mature Age Gays, ACON, distributed online by these agencies via survey monkey and websites | IV: gender identity (nominal male, female, transgender, other), openness about sexuality | Organisational level, interpersonal level | Only 29% completed power of attorney and 12% completed ACD. Only 52% of respondents had spoken with their chosen HCA regarding ACP, 31% reported not sure if their wishes would be respected. Trans, lesbians, not open about sexuality were less likely to speak about EOL decisions |

| DV: Respondents’ attitudes towards alternative decision-making (partner, friend, general practitioner, other) using 5-point Likert scale if person would carry out their wishes about ACD | ||||

| Study purpose/aims | Theory/framework/model | Setting | Sample description, size (n) | |

| Hughes and Cartwright (2014) | Examination of knowledge and attitudes towards end-of-life care in LGBTQ populations w. focus on preparedness to discuss w/ HCP’s EOL plans | None described, individual focused; legal options to be explored | New South Wales, Australia | N = 305 LGBT persons |

| One state in Australia with suspected largest no. of LGBT people due to census data | ||||

| Cartwright et al. (2012) | Exploratory study into LGBT people’s experiences with EOL care as reported by HCP’s and members of community organisations | Grounded theory to develop data collection | Northern, New South Wales, Australia | N = 25 HCP’s |

| June et al. (2012) | To explore EOL healthcare attitudes among younger and older sexually diverse women | None stated | Recruited through undergraduate students at University of Colorado received extra credit for recruitment of family members/friends, UCCS Gerontology Center Participant Registry, UCCS staff, Colorado Springs, Pueblo, Boulder, Denver Pride Centers’ newsletters/events | N = 30 lesbian older adult women (ages 60–81), n = 31 heterosexual older adult women (ages 60–77), n = 35 lesbian middle-aged women (ages 35–59), n = 49 heterosexual middle-aged women (ages 35–59) |

| Reygan and D’Alton (2013) | To rectify a service gap and to support oncology and palliative care staff to deliver affirmative care to their LGB patients and families, increase palliative and oncology care staff awareness of LGB issues relevant to help-seeking behaviours in hospital and hospice settings and to provide staff with access to training materials that are easily accessible and transferable to other palliative care and oncology services | None stated | St. Vincent’s University Hospital in Dublin | N = 201 participants |

| Rivera et al. (2011) | To better understand the lived experiences of gay and lesbian older adults who were involved with their long-term life planning | Phenomenological case study approach | US, drawn from members of gay and lesbian social clubs within a gated retirement community in Orange County, CA | N = 15, criterion sampling |

| Study design | Data collection methods | Primary outcome variables | SEM levels addressed (or Theory application) | Results |

| Quantitative study using demographics, bivariate analysis, frequency tables, cross-tabulations, chi- squared analysis, answers coded thematically | Sent out 1,400 hardcopy surveys to members of LGBT community - Gender Centre, Mature Age Gays, ACON, distributed online by these agencies via survey monkey and websites | Knowledge of end of life care planning options, discussion of end-of-life care with healthcare providers | Does mention significance of legal options for LGBTQ individuals: organisational level | Need for training of HCP’s in EOL planning and communication w/ LGBTQ pts. |

| More research needed into experience of LGBT in planning for EOL. Qualitative studies to investigate meaning, ethical implications | ||||

| Qualitative. Semistructured questionnaire, HCP’s consultation forum, interviews from metropolitan LGBT service providers by audio recordings and field notes. Thematic analysis w/ open coding of broad themes and categories, axial coding w/ major themes -> Grounded theory used | Recruitment through newspaper ads, flyers mailing lists of EOL care providers | Barriers to LGBT pts due to HCP’s lack of understanding | Community level Organisational level | Descriptions of concepts: Lack of recognition faced by LGBT pts receiving care and support towards EOL, HCP’s lack of understanding of legal provisions around EOL, barriers to LGBT involved in advance care planning, value of LGBT |

| Quantitative through adapted scales: EOL questionnaire, Preferences for EOL Care, AARP EOL North Carolina Survey, Reese’s Hospice Barriers Scale, Hospice Beliefs and Attitudes scale, Health Care System Distrust Scale, Holistic Complementary and Alternative Medicine Questionnaire | Self-reported questionnaire in person or online exploring beliefs that may affect decision-making at the end of life | IV: Beliefs about pain, hospice beliefs, preferences for care, healthcare distrust, alternative medicine DV: Sexual orientation and age | Organisational level | Groups report same levels of comfort discussion pain, positive views of hospice and healthcare distrust. Lesbian women reported more positive beliefs of alternative medicines; heterosexual women were more likely to choose life sustaining measures |

| Qualitative: 17 individual trainings across 4 sites; evaluation interviews in person, over phone by external evaluators | Does not state | Intervention: Training material | Supranational level, organisational level | 98% found training useful, 98% would recommend to colleagues, 93% found training increased their awareness of LGB issues and feel more comfortable |

| DV: awareness of LGB issues to provide care to LGB patients | ||||

| Qualitative, thematic concepts | In depth, semistructured interviews audio-recorded w/ transcription verbatim | DV- self-perceived future life planning needs and preferences of older gays and lesbians including housing needs, financial preparation, preferences for sustaining overall quality of life | Organisational level, community level, intrapersonal level | Themes: 1 - Future living arrangements, financial arrangements, perceptions of their relationships in later years, quality of life, envisioning compassionate long-term care for older gays and lesbians |

A literature matrix was created (Table 2) to report results in stage 4, as recommended by Klopper, Lubbe and Rugbeer, of all manuscripts reviewed including author, data, purpose, setting, sample description, study design, methods, primary outcome variables and results (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Lubbe, Klopper, & Rugbeer, 2007). Lastly, for stage 5, data were collated to highlight geographic regions and common thematic constructs identified within SEM levels at varying levels of interaction (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005).

TABLE 2.

Literature matrix

| Almack | June | Hulbert-Williams | Cartwright, Hughes, Leinert | Hughes, Cartwright (ACP) | Hughes, Cartwright | Carabaz | Rivera | Reygan | Bristowe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigma/discrimination | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Legal | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Disenfranchisement | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Families of choice | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Homophobia/heterosexism | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Distrust of HCP | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Criminalisation/persecution | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Social isolation/support networks | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Bereavement | X | X | X | |||||||

| Mental health | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Quality-of-life | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Ageing | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Living a lie | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| End-of-life care | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Advanced care planning (ACP) |

X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

3 ∣. RESULTS

Of the 10 manuscripts analysed, coincidentally, half were qualitative (n = 5) and half were quantitative studies (n = 5). Four studies did not mention use of a theoretical framework, while the remaining six studies applied various theories including minority stress theory, SEM and a disenfranchised grief model. Only one study was conducted by nurses, while the majority of studies were conducted by social workers and psychologists. Three of the ten studies were conducted in the United States and the remaining were completed in the United Kingdom and Australia. Themes were identified as common and essential to either establishing two-way trust or deteriorating the relationship between the healthcare practitioner and LGBT patient.

3.1 ∣. Intrapersonal level

Intrapersonal level factors address individuals’ knowledge, beliefs, behaviour, attitudes and developmental characteristics guiding self-perception (McLeroy et al., 1988). The reviewed studies showed that discrimination, stigma, homophobia, criminalisation and persecution (Almack, Seymour, & Bellamy, 2010; Bristowe, Marshall, & Harding, 2016; Carabez & Scott, 2016; Cartwright, Hughes, & Lienert, 2012; Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; June, Segal, Klebe, & Watts, 2012; Reygan & D’Alton, 2013; Rivera, Wilson, & Jennings, 2011) result in feelings of exclusion (Almack et al., 2010; June et al., 2012), social isolation (Almack et al., 2010; Bristowe et al., 2016; Cartwright et al., 2012; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; Rivera et al., 2011) and psychological distress (Cartwright et al., 2012; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017). These types of negative interactions lay the groundwork for determinant of poor health outcomes (Almack et al., 2010; Bristowe et al., 2016; Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; Reygan & D’Alton, 2013; Rivera et al., 2011). In addition, when a patient perceives their needs are undervalued or insufficient by the HCP, individual distress can occur resulting in increased stress and dismissive palliative care (Richards et al., 2011).

3.1.1 ∣. Discrimination, fear and distress

Discrimination is described as a lack of sensitivity (June et al., 2012), same-sex relationship pathologisation, suboptimal care at the end-of-life (Almack et al., 2010) difficulty in accessing and obtaining answers from healthcare professionals (Bristowe et al., 2016), provision of misinformation (Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017) and heteronormative/homophobic assumptions (Almack et al., 2010; Bristowe et al., 2016; Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; Reygan & D’Alton, 2013; Rivera et al., 2011). These experiences are only a few that can create fear and distress among the LGBT population when presenting for palliative care.

3.1.2 ∣. Social isolation and ageing

Multigenerational LGBT patients express alternative perceptions of fear and discrimination, creating additional barriers based on historical experiences. For example, those who are greater than 65 years of age felt the need to hide their sexual orientation in the past from family, employers, neighbours and friends. This fear of acceptance extends to many areas including the care given by home health aides and long-term care facilities creating an added burden (Almack et al., 2010; Rivera et al., 2011). Almack et al. suggest that social networks change as the LGBT person ages, sometimes becoming smaller with limited social interactions due to less accessibility to LGBT community facilities when compared to their non-LGBT counterparts (Almack et al., 2010). Without peer social interaction and acceptance, elderly LGBT individuals have reported feeling they must go back ‘into the closet’ and acclimate to social situations in which fear of rejection is present (Almack et al., 2010; Cartwright et al., 2012; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; Rivera et al., 2011).

3.1.3 ∣. Cancer and palliative care

It is likely that discrimination, fear and distress prevent patients from presenting for screening, prevention and routine cancer care as well as palliation during terminal illness. While the care needs for both heterosexual and LGBT patients are the same, sensitivity surrounding delivery of care warrants further exploration and should be individualised (Hughes & Cartwright, 2014). When patients have overall negative past experiences with healthcare practitioners, patients are less likely to form trusting bonds and more likely to withhold personal information, eliminating the practitioners’ ability to explore symptoms and preferences to provide palliative care. Inclusion of appropriate decision-makers (Cartwright et al., 2012), provision of accurate and relevant information (Almack et al., 2010; Bristowe et al., 2016; Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; Reygan & D’Alton, 2013; Rivera et al., 2011) and LGBT disparities trained healthcare professionals may decrease discrimination, fear, social isolation and distress (Hughes & Cartwright, 2014).

3.2 ∣. Interpersonal level

Interpersonal levels of interactions are addressed through the perceptions of LGBT patients and their caregivers (McLeroy et al., 1988). Healthcare practitioners hold individual views, attitudes and beliefs which shape communication and treatment of the LGBT patient and caregiver (Almack et al., 2010; Bristowe et al., 2016; Carabez & Scott, 2016; Cartwright et al., 2012; Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; June et al., 2012; Rivera et al., 2011).

3.2.1 ∣. Stigma

Heterosexist language pertaining to sexual orientation and identification including what is ‘normal’ or ‘not normal’, ‘regular’ or ‘irregular’, lack of awareness, history of discrimination heteronormative assumptions held by some practitioners and institutional practices may further stigmatise the LGBT patient (Carabez & Scott, 2016). For example, previous studies report that stigma exists in advance care planning, even though advance directives are in place they may not necessarily be honoured in the same manner. This has been displayed through responses by practitioners in qualitative studies reporting that same-sex marriage partners are not ‘real couples’ (Carabez & Scott, 2016).

3.2.2 ∣. Bereavement, disenfranchised guilt and families of choice

For the purpose of this review, bereavement and disenfranchised guilt will be included with interpersonal factors as the reviewed articles discuss these concepts in relation to healthcare practitioner perceptions. Almack et al. (2010) explored bereavement of an LGB (transgender and queer persons were not included in this study) partner through narratives which identify the importance of the familial construct (Almack et al., 2010). While new and increasing possibilities of ‘family’ in the LGB population are created, current terminology and perspectives have not reflected this change, which may be confusing for both LGB patients and HCPs (Almack et al., 2010). These nontraditional family members consisting of friends or partners (both with and without legal unions) are described as ‘families of choice’, and while they may be most important to the LGBT patient, they are not always recognised and respected by biological family members and HCPs (Almack et al., 2010; Bristowe et al., 2016; Carabez & Scott, 2016; Cartwright et al., 2012; Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; June et al., 2012; Reygan & D’Alton, 2013; Rivera et al., 2011). When the LGBT patient is unable to speak for themselves, either during critical illness or after death, the partner may be disregarded without acknowledgement from biological families or healthcare practitioners, causing disenfranchised grief (Doka, 1989). Disenfranchised grief refers to times when biological families or HCPs of the ill or dead do not recognise or respect non-traditional family members (Almack et al., 2010; Bristowe et al., 2016; Carabez & Scott, 2016; Cartwright et al., 2012; Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; June et al., 2012; Reygan & D’Alton, 2013; Rivera et al., 2011).

3.2.3 ∣. Cancer and palliative care

The effects of stigma, the disenfranchised guilt felt by the unrecognised partner and families of choice within cancer care continue to isolate LGBT persons. Barriers are created which may further disengage patients from obtaining compassionate care. Provider education and training may be an intervention which addresses such issues, along with institutional level changes (Reygan & D’Alton, 2013).

3.3 ∣. Organisation/institutional level

3.3.1 ∣. Advance care planning and legal aspects

A disproportionate percentage of LGBT respondents did not have advance care planning (ACP) discussions with their desired surrogate decision-maker, and many did not have advance care directives (Hughes & Cartwright, 2015). Withholding the distribution of ACP forms by HCPs when caring for LGBT patients has been reported as well as overt discrimination (Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015;Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017). There is a lack of precise and accurate ACP legal advice for LGBT persons with regard to their relationship status including married, domestic partnership and cohabitation (Cartwright et al., 2012;Hughes & Cartwright, 2014). There is potential for healthcare practitioners to be better educated on providing ACPs to LGBT patients so as to allow these patients to feel supported and fully informed (Carabez & Scott, 2016; Hughes & Cartwright, 2015). Hughes and Cartwright (2015) suggest that limited discussions about ACP between LGBT persons occur due to lack of education by HCPs on both the organisational and interpersonal level (Hughes & Cartwright, 2015).

3.3.2 ∣. End-of-life care

Common barriers reported by LGBT persons who receive end-of-life care include discrimination, heteronormative language and a failure by institutions to create LGBT friendly environments while providing care (Almack et al., 2010; Bristowe et al., 2016; Carabez & Scott, 2016; Cartwright et al., 2012; Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; June et al., 2012; Reygan & D’Alton, 2013; Rivera et al., 2011). HCPs feel ill equipped to address end-of-life conversations with LGBT patienťs due to lack of current available education (Bristowe et al., 2016; Hughes & Cartwright, 2015).

3.3.3 ∣. Cancer and palliative care

An additional aspect of palliative care is to prepare caregivers for the death of their loved one. Often, preparation for death is a process that may last longer than other terminal conditions, leaving time for exploration to identify a trusted decision-making agent (Barnato, Cohen, Mistovich, & Chang, 2015). For times when patients can no longer make decisions, healthcare agents act as surrogates for the patient in the process of making clinical care decisions. Education about legal aspects may be included to ensure a clear understanding of familial structures and ways to provide a safe environment (Barnato et al., 2015).

3.4 ∣. Historical/societal/cultural level

3.4.1 ∣. Criminalisation and persecution

Historical events shape cultural and societal perceptions of LGBT persons. Same-sex relations were criminalised and pathologised in many cultures (Almack et al., 2010; Bristowe et al., 2016; Carabez & Scott, 2016; Cartwright et al., 2012; Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; June et al., 2012; Reygan & D’Alton, 2013; Rivera et al., 2011). In Ireland, males engaging in sex with other males was considered criminal until 1993, lagging behind both the United States and United Kingdom (Reygan & D’Alton, 2013). Prior to 2014, when marriage was determined a federal right for same-sex couples in the United States, legal barriers to obtain social security benefits for one’s partner prevented equality (Rivera et al., 2011). While federal laws have widened to include many benefits for LGBT populations, an overall gap continues to exist with fewer legal protections than non-LGBT populations. In addition, varying state laws and legal policies create continued adversity (Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, Board on the Health of Select Populations, & Institute of Medicine, 2011). In a survey conducted in 1987, 75% of the UK population believed same-sex attraction was morally wrong in comparison to 32% in 2008 (Almack et al., 2010; Hughes & Cartwright, 2015; Rivera et al., 2011).

3.5 ∣. Global perspectives

3.5.1 ∣. Quality of care and palliative care

In 2014, the International Psycho-Oncology Society Lisbon declared that equal care for all persons is a fundamental human right and is vital to quality of care (Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017). According to the Metlife Mature Market Institute Study of LGBT populations worldwide, it was found that only 42% had completed an advance care directive (Hughes & Cartwright, 2014). These statistics indicate that these populations may benefit from end-of-life and palliative care education. Global implications of discriminatory behaviour towards LGBT populations have prompted international guidelines for providing non-discriminatory palliative care to all patients (Reygan & D’Alton, 2013). In addition, an international discussion of the differences in care for LGBT populations in other countries including the United Kingdom, Australia and United States is necessary to overcome healthcare barriers (Bristowe et al., 2016; Carabez & Scott, 2016; Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015; June et al., 2012).

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

4.1 ∣. Summary of findings

This scoping review aimed to answer the question, what is known from the existing literature about the barriers to providing culturally competent cancer-related palliative care to LGBT patients. Identified barriers outlined in this review have identified that LGBT patients and their caregivers experience homophobia, exclusion, social isolation, criminalisation, persecution and fear of discrimination. Additionally, lack of provider knowledge has led to negative patient perceptions by HCPs when providing palliative care (Almack et al., 2010; Bristowe et al., 2016; Carabez & Scott, 2016; Cartwright et al., 2012; Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; June et al., 2012; Reygan & D’Alton, 2013; Rivera et al., 2011). Unfortunately, these barriers in LGBT populations have reduced the quality of palliative care and further perpetuate marginalisation and healthcare inequities. This review has further identified a gap in the current literature as there is minimal research in the United States investigating the barriers and healthcare needs of palliative LGBT patients with cancer.

Due to these gaps in the literature, it is evident that further research regarding the provision palliative care in the cancer population is warranted. The following areas of future research and targeted interventions in the LGBT population have been identified through this scoping review: (i) HCP perceptions of LGBT-specific palliative care needs, (ii) addressing social isolation, (iii) protection and assessment of community needs for the ageing population, (iv) managing caregiver distress, (v) counselling about advanced directives and (vi) education for HCPs through the creation a safe environment.

4.2 ∣. Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review include definitive areas for implications in practice by healthcare providers when providing palliative care to LGBT populations. Themes for targeted interventions were identified. Limitations included bias of selected themes by author and lack of critical review of articles chosen.

4.3 ∣. Implications for practice

Studies suggest public policy strategies such as anti-bullying policies, zero tolerance for microaggression and passive acceptance, can change the healthcare environment (Almack et al., 2010; Bristowe et al., 2016; Hardacker, Rubinstein, Hotton, & Houlberg, 2014). When implemented, these strategies create awareness, alter perceptions of discrimination towards LGBT individuals, produce change on a large-scale level and alter cultural norms (Bristowe et al., 2016). In addition, medical and nursing education about LGBT healthcare inequities lead to improved sensitivity to provide culturally sensitive palliative care (Almack et al., 2010; Bristowe et al., 2016; Carabez & Scott, 2016; Hughes & Cartwright, 2014, 2015; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017; June et al., 2012; Rivera et al., 2011). To successfully create the bonds necessary for shared decision-making, guidelines suggest that it is necessary for patients and family members to feel safe in disclosing their SOGI status during all phases of cancer treatment (Cloyes, Hull, & Davis, 2018).

Social isolation in the ageing LGBT population leads to overall poorer health outcomes (D’Augelli, Grossman, Hershberger, & O’Connell, 2001; Yancu, Farmer, & Leahman, 2010). To address social isolation as a component of palliative care for LGBT individuals, implementation of community programs and inclusion strategies may prove to be beneficial. One such example is a Naturally Occurring Retirement Community (NORC) program. Historically, NORC programs have supported older LGBT adults by creating a strategic approach through partnerships in community research, provision of services and proactive engagement (Wright et al., 2017). These programs allow an individual to receive important services within their own community thereby decreasing social isolation, promoting independence and increasing life satisfaction for LGBT older adults (Jiska, Julia, & Maha, 2010; Kyriacou & Vladeck, 2011; Wright et al., 2017; Yancu et al., 2010). Further research and development of NORC programs may further lessen social isolation.

The palliative care needs of patients with advanced staged cancer include both inpatient and home hospice care. Previous studies suggest that a fear exists among LGBT patients concerning the quality of care they will receive if their SOGI status is disclosed. Having a welcoming environment with culturally competent trained staff may improve the quality of end-of-life care (Yancu et al., 2010). Often, fear of asking sensitive questions about sexual orientation or gender identification leads practitioners to avoid these discussions and as a result further perpetuates feelings of isolation in LGBT populations. When admitting LGBT patients to hospice, it is important for providers to take a detailed and inclusive health history without judgement (Yancu et al., 2010). Organisations such as Services and Advocacy for LGBT elders provide resources for staff education, creation of welcoming environments and taking culturally sensitive health histories and assistance in evaluating the needs of LGBT patients (D’Augelli et al., 2001; Kling & Kimmel, 2006).

Overall caregiver distress may be increased in the LGBT populations due to disenfranchised grief and may go unrecognised by healthcare teams (Cloyes et al., 2018). It is imperative that providers recognise ‘families of choice’ for LGBT individuals and avoid heteronormative assumptions (Cloyes et al., 2018; Hash, 2006). In addition, providers and institutions should be aware of LGBT-specific bereavement support groups in their communities for caregiver referrals (Hash, 2006).

Lastly, education about advanced directives when providing palliative care to LGBT individuals is highly specialised and necessitates awareness and exploration by the provider. Despite section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act being abolished in 2013, many benefits heterosexual couples receive are not extended to same-sex couples (Yancu et al., 2010). Due to this lack of recognition, having documentation of advanced directives, healthcare agent designation and living wills are integral to adherence to LGBT persons’ end-of-life wishes. Previous studies report that decisions about end-of-life default to biological families of origin who may not respect the wishes of the ill person. Reasons for this may be due to estranged relationships, poor communication and discordant beliefs (Yancu et al., 2010).

5 ∣. CONCLUSION

Studies suggest public strategies such as anti-bullying policies, zero tolerance for microagression and passive acceptance may highlight discriminatory views held by some HCPs (Bristowe et al., 2016; Hardacker et al., 2014; Kathryn Almack et al., 2010). As a result, large-scale change can be produced to alter cultural norms (Bristowe et al., 2016). The National LGBT Cancer Network outlines specific steps to providing culturally competent care for LGBT populations that increase and heighten knowledge by HCPs for health and social service needs specific to these populations (Margolies & McDavid, n.d.). This training can provide practitioners with practical steps to address the unique palliative care needs of LGBT patients with cancer. By increasing knowledge, palliative care is more likely to be provided in a culturally competent way and can decrease healthcare inequities.

What is known about this topic.

Discrimination, refusal of care, bias, erroneous assumptions and derogatory statements towards LGBT persons reported in 70% of healthcare visits in United States.

LGBT people are at a higher risk for developing certain cancers and may present at later disease stages.

Palliative care requires trust between provider and patient, critical for understanding specific vulnerabilities and creation of safe environment for SOGI disclosure.

What this paper adds about this topic

Identification of barriers that exist in provision of palliative care for LGBT patients with cancer

Anti-bullying policies, zero tolerance for microaggression and passive acceptance to change the healthcare environment

Training and education provide practitioners steps addressing the unique palliative care needs of LGBT patients with cancer and decrease healthcare inequities

Acknowledgments

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- Almack K, Seymour J, & Bellamy G. (2010). Exploring the impact of sexual orientation on experiences and concerns about end of life care and on bereavement for lesbian, gay and bisexual older people. Sociology, 44(5), 908–924. 10.1177/0038038510375739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Geriatrics Society Ethics Committee. (2015). American geriatrics society care of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults position statement: American geriatrics society ethics committee. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(3), 423–426. 10.1111/jgs.13297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, & O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnato A, Cohen E, Mistovich K, & Chang C. (2015). Hospital end-of-life treatment intensity among cancer and non-cancer cohorts. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 49(3), 521–529.e5. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett N, & Wholihan D. (2016). Providing palliative care to LGBTQ patients. Nursing Clinics of North America, 51(3), 501–511. 10.1016/j.cnur.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonvicini KA (2017). LGBT healthcare disparities: What progress have we made? Patient Education and Counseling, 100(12), 2357–2361. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristowe K, Hodson M, Wee B, Almack K, Johnson K, Daveson BA, … Harding R. (2018). Recommendations to reduce inequalities for LGBT people facing advanced illness: ACCESSCare national qualitative interview study. Palliative Medicine, 32(1), 23–35. 10.1177/0269216317705102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristowe K, Marshall S, & Harding R. (2016). The bereavement experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or trans people who have lost a partner: A systematic review, thematic synthesis and modelling of the literature. London: SAGE Publications. 10.1177/0269216316634601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burgard S, Cochran S, & Mays V. (2005). Alcohol and tobacco use patterns among heterosexually and homosexually experienced California women. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 77(1), 61–70. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhalter JE, Margolies L, Sigurdsson HO, Walland J, Radix A, Rice D, … Maingi S (2016). The national LGBT cancer action plan: A white paper of the 2014 national summit on cancer in the LGBT communities. LGBT Health, 3(1), 19–31. 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carabez R, & Scott M. (2016). ‘Nurses donť deal with these issues’: Nurses’ role in advance care planning for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(23–24), 3707–3715. 10.1111/jocn.13336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright C, Hughes M, & Lienert T. (2012). End-of-life care for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14(5), 537–548. 10.1080/13691058.2012.673639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ME, Landers S, Linde R, & Sperber J. (2001). The GLBT health access project: A state-funded effort to improve access to care. American Journal of Public Health, 91(6), 895–896. 10.2105/AJPH.91.6.895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloyes KG, Hull W, & Davis A. (2018). Palliative and end-of-life care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) cancer patients and their caregivers. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 34(1), 60–71. 10.1016/j.soncn.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, … Moher D. (2014). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291–1294. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Leading Health Indicators for Healthy People, 2020, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, & Institute of Medicine. (2012). Leading health indicators for healthy people 2020. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. 10.17226/13088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, Board on the Health of Select Populations, & Institute of Medicine. (2011). Health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, the: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved from http://lib.myilibrary.com?ID=321342 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin S. (2019). Trends in cancer and heart disease death rates among adults aged 45–64: United states, 1999–2017. Washington DC. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_05-508.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Hershberger SL, & O’Connell TS (2001). Aspects of mental health among older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Aging & Mental Health, 5(2), 149–158. 10.1080/13607860120038366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibble S, Roberts S, Robertson P, & Paul S. (2002). Risk factors for ovarian cancer: Lesbian and heterosexual women. Oncology Nursing Forum, 29(1), E1–E7. 10.1188/02.ONF.E1-E7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doka KJ (1989). Disenfranchised grief. Lexington, MA: Heath. [Google Scholar]

- Gates GJ (2017). LGBT data collection amid social and demographic shifts of the US LGBT community. American Journal of Public Health, 107(8), 1220–1222. 10.2105/AJPHp.2017.303927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin EP, Hart S, Gordon N, & Ackerson L. (2001). Patterns of cigarette smoking and alcohol use among lesbians and bisexual women enrolled in a large health maintenance organization. American Journal of Public Health, 91(6), 976–979. 10.2105/AJPH.91.6.976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardacker CT, Rubinstein B, Hotton A, & Houlberg M. (2014). Adding silver to the rainbow: The development of the nurses’ health education about LGBT elders (HEALE) cultural competency curriculum. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(2), 257–266. 10.1111/jonm.12125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding R, Epiphaniou E, & Chidgey-Clark J. (2012). Needs, experiences, and preferences of sexual minorities for end-of-life care and palliative care: A systematic review. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15(5), 62–611. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hash K. (2006). Caregiving and post-caregiving experiences of midlife and older gay men and lesbians. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 47(3–4), 121–138. 10.1300/J083v?47n03_08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan K. (1998). The nature and predictors of substance use among lesbians. Addictive Behaviors, 23(4), 517–528. 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00003-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M, & Cartwright C. (2014). LGBT people’s knowledge of and preparedness to discuss end-of-life care planning options. Health & Social Care in the Community, 22(5), 545–552. 10.1111/hsc.12113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M, & Cartwright C. (2015). Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people’s attitudes to end-of-life decision-making and advance care planning. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 34, 39–43. 10.1111/ajag.12268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulbert-Williams NJ, Plumpton CO, Flowers P, McHugh R, Neal RD, Semlyen J, & Storey L. (2017). The cancer care experiences of gay, lesbian and bisexual patients: A secondary analysis of data from the UK cancer patient experience survey. European Journal of Cancer Care, 26(4), e12670. 10.1111/ecc.12670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Campaign. (2018). Glossary of terms. Retrieved from https://www.hrc.org/resources/glossary-of-terms

- Jiska C, Julia F, & Maha D. (2010). The impact of a naturally occurring retirement communities service program in Maryland, USA. Health Promotion International, 25(2), 210–220. 10.1093/heapro/daq006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- June A, Segal DL, Klebe K, & Watts LK (2012). Views of hospice and palliative care among younger and older sexually diverse women. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 29(6), 455–461. 10.1177/1049909111429120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kling E, & Kimmel D. (2006). SAGE: New York city’s pioneer organization for LGBT elders. In Kimmel D, Rose T & David S (Eds.), Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender aging research and clinical perspectives (pp. 265–276). New York; Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press. 10.7312/kimm13618 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kok GJ, Gottlieb N, Commers M, & Smerecnik CMR (2008). The ecological approach in health promotion programs: A decade later. American Journal of Health Promotion, 22(6), 437–442. 10.4278/ajhp.22.6.437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou C, & Vladeck F. (2011). A new model of care collaboration for community-dwelling elders: Findings and lessons learned from the NORC-health care linkage evaluation. International Journal of Integrated Care, 11(2), e017. 10.5334/ijic.518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubbe S, Klopper R, & Rugbeer H. (2007). The matrix method of literature review. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10500/3002

- Margolies LJ, & McDavid J. (n.d.). Best practices in creating and delivering LGBTQ cultural competency trainings for health and social service agencies.

- McCabe MS (2014). Cancer survivorship: We’ve only just begun. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 12(12), 1772. 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, & Glanz K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education & Behavior, 15(4), 351–377. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicine AAoHaP. AAHPM and the specialty of hospice and palliative medicine. Retrieved from http://aahpmorg/about/about2017

- National LGBT Cancer Network. (2013). The LGBT community’s disproportionate cancer burden. Retrieved from http://cancer-network.org/cancer_informaiton/cancer_and-the_lgbt_community/the_lgbt_communitys_disproportionate_cancer_burden.php

- Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, White W, Tran E, Brenman S, … Lunn MR (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and Transgender-Related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA, 306(9), 971–977. 10.1001/jama.2011.1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, & Moher D. (2017). Evaluations of the uptake and impact of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement and extensions: A scoping review. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 263. 10.1186/s13643-017-0663-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reygan FCG, & D’Alton P. (2013). A pilot training programme for health and social care professionals providing oncological and palliative care to lesbian, gay and bisexual patients in Ireland. Psycho-Oncology, 22(5), 1050–1054. 10.1002/pon.3103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards SH, Winder R, Seamark C, Seamark D, Avery S, Gilbert J, … Campbell JL (2011). The experiences and needs of people seeking palliative health care out-of-hours: A qualitative study. Primary Health Care Research and Development, 12(2), 165–178. 10.1017/S1463423610000459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera E, Wilson S, & Jennings L. (2011). Long-term care and life planning preferences for older gays and lesbians. Journal of Ethnography Quality Research, 5, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan CM, Huggins J, & Beatty R. (1999). Substance use disorders and the risk of HIV infection in gay men. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 60(1), 70. 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall RD, Greenwood GL, Acree M, Paul J, & Coates TJ (1999). Cigarette smoking among gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health, 89(12), 1875–1878. 10.2105/AJPH.89.12.1875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein G, & Bonuck K. (2001). Original research: Physician-patient relationships among the lesbian and gay community. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 5(3), 87–93. 1011648707507 [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. (1996). Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion, 10(4), 282–298. 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright LA, King DK, Retrum JH, Helander K, Wilkins S, Boggs JM, … Gozansky WS (2017). Lessons learned from community-based participatory research: Establishing a partnership to support lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender ageing in place. Family Practice, 34(3), 330–335. 10.1093/fampra/cmx005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancu CN, Farmer DF, & Leahman D. (2010). Barriers to hospice use and palliative care services use by African American adults. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 27(4), 248–253. 10.1177/1049909109349942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]