Abstract

目的

采用激光三维扫描技术评估玻璃体和通用型复合树脂用于后牙充填的耐磨性。

方法

根据纳入标准选取48名患者共108颗患牙(每组各54颗),随机分配用玻璃体(Beautifil Ⅱ,简称BF)或通用型复合树脂(Filtek Z350,简称Z350)进行充填。分别于术后1周、6个月、18个月和4年,采用改良美国公共卫生署(United States Public Health Service,USPHS)标准对充填体进行临床评价并拍照和制取模型。使用激光三维扫描仪扫描模型后,对图像进行配准和计算磨耗深度,使用SPSS 20.0进行统计分析。

结果

术后4年回访43名患者,回访率为89.6%。BF组和Z350组各有4例和3例出现脱落、继发龋、充填体折断和牙髓坏死。两组充填体的4年存留率均为95.8%,符合美国牙医协会(American Dental Association,ADA)标准(3年存留率>90%)。0~6个月两组充填体的磨耗速率最快,随后磨耗速率的下降趋于平缓,BF组4年总磨耗深度为(58±22) μm,Z350组为(54±16) μm(P>0.05),耐磨性均符合ADA标准(3年磨耗深度 < 100 μm)。两组充填体均表现为围绕咬合接触区形成凹坑状磨耗(Ⅰ型)和充填体发生均匀磨耗(Ⅱ型)。术后4年,Ⅰ型磨耗充填体中,BF组的磨耗深度大于Z350组(P < 0.05),Ⅱ型磨耗充填体中,两组间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

结论

玻璃体的4年存留率和耐磨性均符合ADA标准,用于后牙 面重咬合接触区时,玻璃体的耐磨性略逊于复合树脂,用于非重咬合接触区时,二者间无明显差异。

面重咬合接触区时,玻璃体的耐磨性略逊于复合树脂,用于非重咬合接触区时,二者间无明显差异。

Keywords: 复合树脂类; 牙修复磨损; 成像, 三维

Abstract

Objective

To observe the wear performance of Giomer and universal composite for posterior restorations by 3D laser scan method, in order to guide the material selection in clinic.

Methods

In this study, 48 patients (108 teeth) were selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All the patients in need of a minimum of 2 Class Ⅰ and/or Class Ⅱ restorations were invited to join the study. The teeth were restored with Giomer (Beautifil Ⅱ, BF) and universal composite (Filtek Z350, Z350) randomly. The restorations were evaluated at baseline and after 6-, 18-, 48-month using the modified United States Public Health Service (USPHS) criteria for clinical performance. The in vivo images and gypsum replicas were taken at each recall. A 3D-laser scanner and Geomagic Studio 12 were used to analyze the wear depth quantitatively. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 20.0.

Results

After 4 years, 89.6% patients were recalled. The survival rate of both materials was 95.8% (Kaplan-Meier survival analysis). Seven restorations of the two materials failed due to loss of restoration, bulk fracture, secondary caries and pulp necrosis. The wear patterns of restorations were divided into 2 classes. Pattern Ⅰ: occlusal contact areas showed the deepest and fastest wear depth; pattern Ⅱ: the wear depth was slow and uniform. Both materials showed a rapid wear in the first 6 months. Then the wear rate was decreased. The occlusal wear depth after 4 years were (58±22) μm and (54±16) μm for BF group and Z350 group respectively, which were in accordance with the American Dental Association (ADA) guidelines (wear depth for 3 years < 100 μm). No significant differences (P>0.05) were observed between the two groups. Regarding the restorations with wear pattern Ⅰ, the wear depth of BF group was higher than Z350 group at 6- and 48-month (P < 0.05), while there was no significant difference between restorations with wear pattern Ⅱ (P>0.05).

Conclusion

Within the limitation of the study, after 4 years, the survival rate and wear resistance of Giomer met ADA guidelines for tooth-colored restorative materials for posterior teeth. When the two materials were applied in occlusal contact areas, wear resistance of Giomer was slightly lower than universal composite resin. No significant difference was found when they were applied in none of the occlusal contact areas.

Keywords: Composite resins; Dental restoration wear; Imaging, three-dimensional

复合树脂类材料用于直接粘接修复因龋坏等原因导致的后牙缺损已有几十年的历史,尽管仍需要改进,但其临床效果已逐渐得到认可并获得广泛应用[1-6]。玻璃体(Giomer)是一种较为新型的材料,可以看作是一种特殊类型的复合树脂,填料为表面预聚合的玻璃离子(surface pre-reacted glass ionomer,S-PRG)并进行了硅烷化处理,具有释放和摄取氟离子的功能[7-8],有利于抑制细菌黏附,预防继发龋[9-10]。这种特殊填料赋予复合树脂抗菌性能的同时,填料粒径以及释氟溶解性是否会影响材料的物理机械性能,特别是耐磨性能,相关的体外研究结果不一,有研究认为玻璃体的耐磨性逊于复合树脂[11-12],也有的体外研究显示玻璃体的耐磨性和复合树脂无明显差异[13],这种体外研究结果的差异可能是由于试验条件不同造成的[14]。此外,有研究指出体外研究结果与临床研究结果只存在中度相关性,不能真实反映材料在体内的耐磨性[14-15]。目前尚缺乏对玻璃体与复合树脂材料耐磨性的随机对照临床研究[1]。

充填材料在体内的耐磨性可以通过体外测量和临床观察进行评价。临床评价方法包括直接法和间接法,直接法操作相对简便,但是精确度和客观性较差,如美国公共卫生署(United States Public Health Service,USPHS)标准敏感度低、不易发现早期磨耗[16];间接法通过获取不同时间点的印模制作模型,于体外进行测量,精确度高于直接法。以往研究常采用一种半定量法测量充填体与洞缘的高度差,通过与系列相差100 μm的标准模型进行对比(如Leinfelder法)[17],获取大概数值来代表整个充填体的磨耗深度,所得结果仍不够精确。三维测量法不仅能够观察复合树脂充填修复体的整体磨耗情况,还可以进行定量分析[18],所得结果更为准确。

本研究应用玻璃体和通用型复合树脂进行后牙龋坏的直接粘接修复,进行4年的临床追踪,在临床检查和评估的基础上,获取不同时期的牙齿和充填体的模型,采用激光三维扫描技术测量,获取准确的数据,比较两种材料用于后牙充填的耐磨性。以往研究显示位于不同牙位和洞型的充填体存留率有差别[19],因此,本研究比较位于不同牙位和洞形充填体的耐磨性,以益于评价材料和指导临床材料的选择。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 实验材料

采用玻璃体材料(Beautifil Ⅱ,简称BF)及其配套粘接剂和通用型复合树脂(Filtek Z350,简称Z350)及其配套粘接剂。

1.2. 分组病例选择与临床操作

本研究通过北京大学口腔医院生物医学伦理委员会批准(PKUSSIRB-201412015),受试者均签署知情同意书。选择在北京大学口腔医院牙体牙髓科就诊的48名患者(24~51岁,中位年龄26岁),要求至少有两颗后牙(磨牙或前磨牙)存在 面或者邻

面或者邻 面缺损,以利分组自体对照。牙体缺损的平均颊舌宽度需大于或等于两尖距离的1/3,咬合关系正常,修复后的患牙修复体与对

面缺损,以利分组自体对照。牙体缺损的平均颊舌宽度需大于或等于两尖距离的1/3,咬合关系正常,修复后的患牙修复体与对 牙具有正常的接触关系,牙髓状态正常。

牙具有正常的接触关系,牙髓状态正常。

共纳入48名患者的108颗患牙,其中57颗前磨牙,51颗磨牙,包括26个Ⅰ类洞和82个Ⅱ类洞。病历号为单数的受试者,受试牙从右上象限开始按照顺时针方向依次充填玻璃体(BF组)和复合树脂(Z350组),病历号为双数的受试者材料选择顺序相反。临床操作由3名有经验的医师完成,操作过程进行标准化:(1)窝洞预备时不制备 面洞缘斜面;(2)在橡皮障隔离下,按照使用说明进行粘接处理和分层充填(每层 < 2 mm),并充分光照(光照强度≥600 mW/mm2);(3)调整咬合并抛光;(4)Ⅱ类洞使用分段式成形片和木楔,近髓处使用Dycal(Dentsply De Trey)间接盖髓,必要时使用流动树脂(Beautifil Flow F10/F02或Filtek Supreme Plus)洞衬。

面洞缘斜面;(2)在橡皮障隔离下,按照使用说明进行粘接处理和分层充填(每层 < 2 mm),并充分光照(光照强度≥600 mW/mm2);(3)调整咬合并抛光;(4)Ⅱ类洞使用分段式成形片和木楔,近髓处使用Dycal(Dentsply De Trey)间接盖髓,必要时使用流动树脂(Beautifil Flow F10/F02或Filtek Supreme Plus)洞衬。

术后1周(基线)、6个月、18个月及48个月,由另外两名检查者按照改良USPHS标准进行盲法评价,评价前检查者进行培训和一致性检测,每次复查时拍摄口内彩照并制取硅橡胶印模和翻制石膏模型。

1.3. 模型的三维测量与分析

对石膏模型进行激光三维扫描(Smart Optics Activity 800,精度10 μm)获取患牙的数字图像。运用逆向三维工程软件(Geomagic Studio 12)分析患牙图像,将复查时的患牙图像(6、18、48个月)分别与充填后1周的患牙图像进行匹配,匹配过程选择全牙面最佳配准(误差 < 20 μm,参考点≥5 000点),未选择固定参考面。计算获得患牙牙面及 面充填体的磨耗深度变化“地图”,并给出每颗患牙牙面和充填体的所有高度减小部位的平均磨耗深度值,匹配过程如图 1所示(以37°

面充填体的磨耗深度变化“地图”,并给出每颗患牙牙面和充填体的所有高度减小部位的平均磨耗深度值,匹配过程如图 1所示(以37° 面充填体的扫描和配准为例)。因患牙牙面高度变化值小,匹配后图像中多显示为绿色或黄色(绿色区域表示无高度变化),表明这些区域具有较好的匹配度。充填体磨损速率显著高于牙面,因此充填体区域的高度变化值为负数。以全牙面上发生磨损的深度变化平均值(即高度变化值为负数的参考点变化量的平均值)代表充填体的磨耗深度,将所有同一时间点的磨耗深度值相加除以该时间点充填体总数得到该时间点充填体的平均磨耗深度值[14-18]。

面充填体的扫描和配准为例)。因患牙牙面高度变化值小,匹配后图像中多显示为绿色或黄色(绿色区域表示无高度变化),表明这些区域具有较好的匹配度。充填体磨损速率显著高于牙面,因此充填体区域的高度变化值为负数。以全牙面上发生磨损的深度变化平均值(即高度变化值为负数的参考点变化量的平均值)代表充填体的磨耗深度,将所有同一时间点的磨耗深度值相加除以该时间点充填体总数得到该时间点充填体的平均磨耗深度值[14-18]。

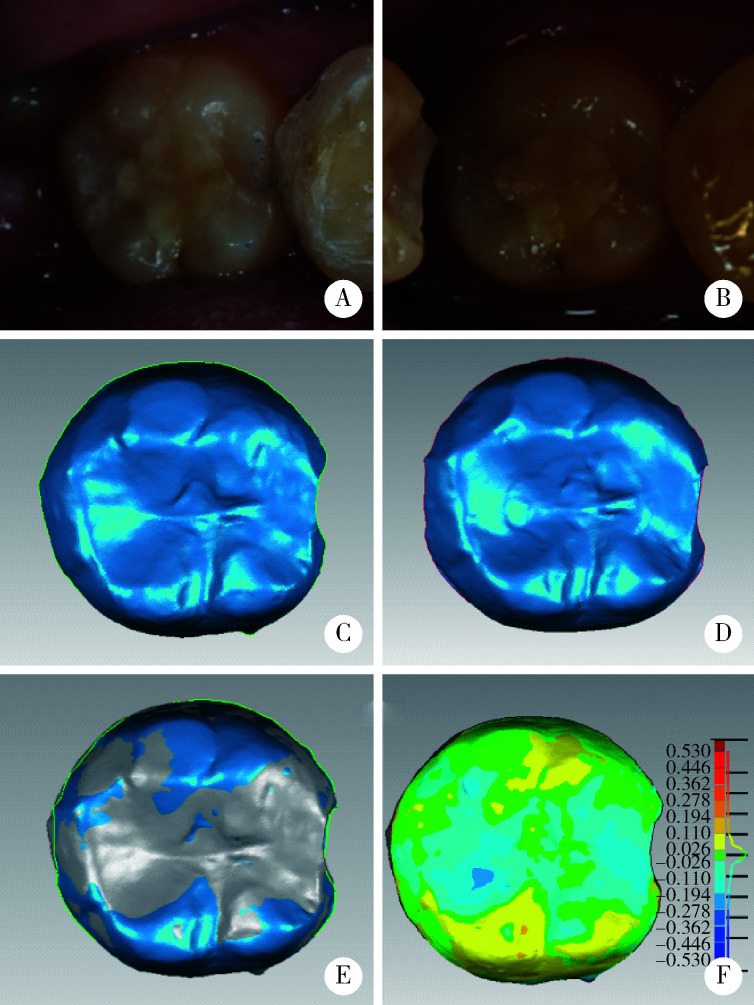

图 1.

图像扫描及配准过程

Process of scanning and analysis

A and C, in vivo and scanning images of 37° restoration at baseline (1 week); B and D, in vivo and scanning images of 37° restoration after 4 years; E, align images by Geomagic Studio 12; F, difference image.

1.4. 统计学分析

采用SPSS 20.0软件进行统计分析(α=0.05),BF组和Z350组充填体的存留率用Kaplan-Meier法进行预估,采用Wilcoxon秩和检验比较两组充填体磨耗深度的差异,采用Mann-Whitney U检验比较牙位和洞型对两组充填体磨耗深度的影响,计数资料均采用χ2检验进行比较。

2. 结果

2.1. 患者及充填体的一般情况

本研究纳入48名患者,其中43人完成了4年复查,5人分别在6个月、18个月和4年随访时因联系方式改变、迁居异地等原因未能完成复查,4年回访率为89.6%。

4年观察期内两组共108个充填体出现脱落(两组各1个)、继发龋(两组各1个)、充填体折断(两组各1个)和牙髓坏死(BF组1个)者共7个,总体存留率约95.8%(Kaplan-Meier生存分析)。

完成4年复查的43名患者共98个充填体中,排除正畸治疗、酸蚀症、其他牙齿治疗过程中调磨患牙及评价为失败的充填体后,最终纳入35名患者共85个充填体(BF组43个,Z350组42个)进行磨耗分析。

2.2. 充填体的磨耗深度变化

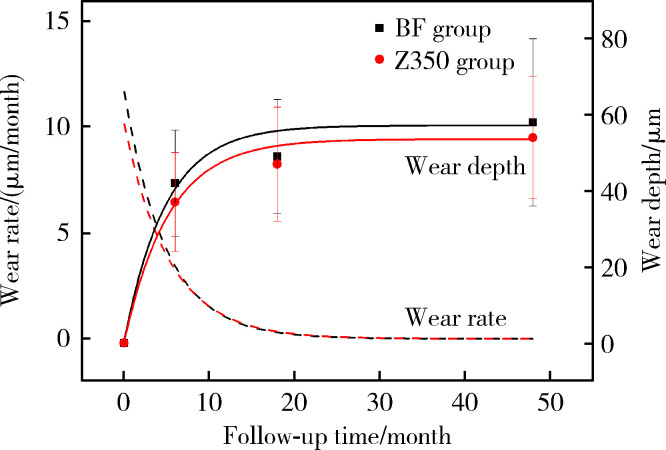

两组充填体在6个月、18个月和4年复查时的 面磨耗深度和磨耗速率见图 2。两种材料均在0~6个月中磨耗速率最快,且BF组的初期磨耗速率明显大于Z350组,6个月时BF组的磨耗深度为(42±14) μm,Z350组为(37±13) μm,随后磨耗速率趋于平缓,两种材料的磨耗速率趋于一致,4年随访时BF组和Z350组的磨耗深度分别为(58±22) μm和(54±16) μm,两组间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),未发现牙位、洞形对磨耗深度有显著影响(P>0.05),具体见表 1。

面磨耗深度和磨耗速率见图 2。两种材料均在0~6个月中磨耗速率最快,且BF组的初期磨耗速率明显大于Z350组,6个月时BF组的磨耗深度为(42±14) μm,Z350组为(37±13) μm,随后磨耗速率趋于平缓,两种材料的磨耗速率趋于一致,4年随访时BF组和Z350组的磨耗深度分别为(58±22) μm和(54±16) μm,两组间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),未发现牙位、洞形对磨耗深度有显著影响(P>0.05),具体见表 1。

图 2.

BF组和Z350组磨耗深度及磨耗速率随时间的变化

The variation of wear depth and wear rate with time in BF group and Z350 group

表 1.

不同牙位和洞型对磨耗深度的影响

Wear depth of different tooth type and cavity type

| Items | Wear depth/μm, x±s | |||||

| Tooth type | Cavity type | |||||

| Premolar | Molar | Class Ⅰ | Class Ⅱ | |||

| BF group | ||||||

| 6 months | 40±13 | 45±16 | 51±16 | 40±13 | ||

| 18 months | 48±14 | 53±18 | 56±16 | 48±15 | ||

| 48 months | 53±17 | 66±27 | 64±21 | 57±23 | ||

| Mann-Whitney U test | P>0.05 | P>0.05 | ||||

| Z350 group | ||||||

| 6 months | 38±16 | 36±10 | 39±12 | 37±14 | ||

| 18 months | 50±20 | 45±10 | 46±13 | 47±16 | ||

| 48 months | 50±14 | 58±18 | 59±18 | 53±17 | ||

| Mann-Whitney U test | P>0.05 | P>0.05 | ||||

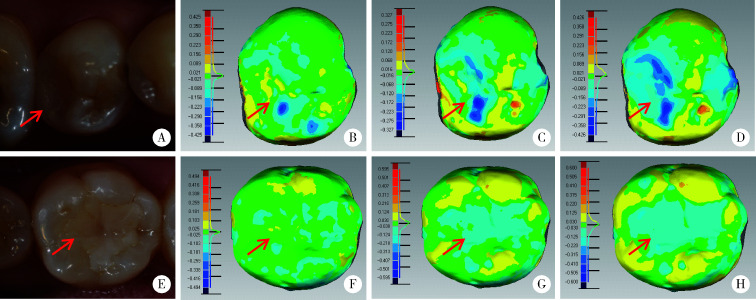

2.3. 充填体磨耗类型分布

两组充填体4年后均产生了不同程度的磨耗,根据其磨耗特点,将其归为两种类型:Ⅰ型,充填体最先发生局部点状磨耗,随着时间推移,局部点状磨耗深度增加,周缘出现磨耗,形成凹坑状磨耗;Ⅱ型,充填体发生均匀磨耗,随着时间推移,充填体磨耗面积均匀增大,磨耗深度均匀增加(图 3)。

图 3.

激光三维扫描图像分析充填体的磨耗情况

Wear condition was analyzed by 3D-laser scanning images

A-D (pattern Ⅰ), the occlusal contact areas showed the deepest and fastest wear, lesser vertical loss around the areas; E-H (pattern Ⅱ), the wear was uniform; A and E, representative clinical picture; B and F, 6 months; C and G, 18 months; D and H, 48 months.

BF组和Z350组充填体的磨耗类型分布见表 2,两组的磨耗类型计数差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

表 2.

BF组和Z350组充填体磨耗类型分布

Wear patterns of BF group and Z350 group

| Items | Pattern Ⅰ | Pattern Ⅱ | Total |

| BF group | 16 | 27 | 43 |

| Z350 group | 17 | 25 | 42 |

| Total | 33 | 52 | 85 |

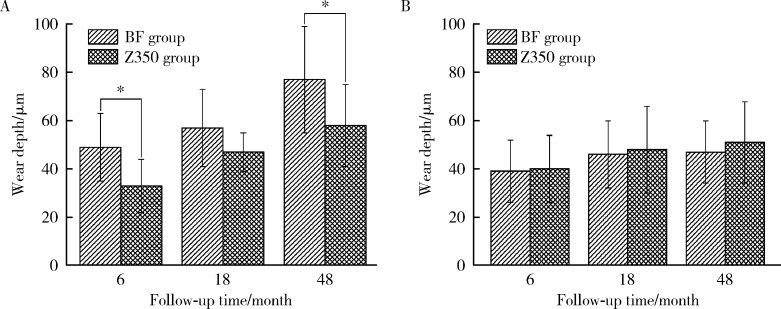

2.4. 不同磨耗类型的磨耗深度分析

发生Ⅰ型磨耗的充填体中,BF组的磨耗深度明显大于Z350组,且在术后6个月和4年时差异均有统计学意义(P < 0.05,图 4A)。发生Ⅱ型磨耗的充填体中,两组的磨耗深度差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,图 4B)。

图 4.

两组不同磨耗类型的磨耗深度对比

Comparison of wear depth in different wear types between BF group and Z350 group

A, pattern Ⅰ; B, pattern Ⅱ.

3. 讨论

本研究中,BF组和Z350组的4年存留率为95.8%,均符合美国牙医协会(The American Dental Association,ADA)标准(3年存留率>90%)[20]。近年的临床研究显示,后牙复合树脂充填体的4年存留率为89.2%~100.0%[2, 21],年平均失败率约为0~3%[22],最常见的失败原因包括充填体部分折断、牙齿折裂、继发龋和牙髓问题等[21],与本研究结果基本一致。

本研究采用了激光三维扫描模型的方法来定量评价复合树脂充填体的磨耗。激光三维扫描仪的系统误差为10 μm[18, 23],制取口内印模和灌制模型过程的误差约为6 μm[24],因此,在复查模型(6、18和48个月)与术后即刻模型匹配过程中,将 < 20 μm的偏差设定为研究允许偏差范围。本研究将广泛使用的纳米填料复合树脂Z350作为对照,尽量减少模型制备、扫描和配准对结果分析的影响,所得到的磨耗趋势及材料之间磨耗量的差异是可信的。

ADA标准要求用于后牙的复合树脂的3年磨耗深度应 < 100 μm[20],本研究结果显示,BF组和Z350组的4年磨耗深度分别为(58±22) μm和(54±16) μm,完全满足后牙应用。BF填料粒径为0.01~4 μm,填料体积分数为68.6%,Z350填料粒径为0.02~1.4 μm,填料体积分数为78.5%。两种材料的填料粒径均较小,填料含量较高,而且均含有纳米级刚性无机粒子。由于纳米材料的表面效应和量子尺寸效应,这两种复合树脂类材料都具有较高的耐磨性[24]。Palaniappan等[25]采用激光三维扫描测量纳米填料复合树脂(Filtek Supreme)48个月时的口内垂直磨耗量为(79±26) μm,与本研究结果相差不大。

本研究中两种充填材料在前6个月的磨耗量迅速增加,约占4年总磨耗量的70%,6个月后磨耗速率趋于平缓,此现象与以往研究一致[25-27]。充填体边缘在初期使用时可发生折断、脱落,表现为初期磨耗深度迅速增加[28],且充填初期承担咀嚼压力大的区域面积较大,造成该区域初期大量的材料丧失[29-30]。后期由于材料的磨损降低,在邻近牙体组织的支持下与对 牙齿接触减弱,承担的咀嚼压力相对降低,此时主要是食物引起的摩擦,使材料磨损速率下降并逐渐趋于平缓。本研究中的两种材料均存在Ⅰ型和Ⅱ型磨损,其中Ⅰ型磨耗量显著大于Ⅱ型磨耗量。Palaniappan等[26]在电子显微镜下观察到复合树脂充填体在重咬合接触区的磨耗以疲劳磨耗为主,材料易产生裂纹、折断,因此产生的磨耗量最大;在轻咬合接触区,树脂表面有大量因酸蚀产生的凹坑状缺损,填料暴露、脱落,磨耗量仅次于重咬合接触区;在非咬合接触区,树脂表面多为与食物排溢方向一致的浅划痕,磨耗量最小。本研究中发生Ⅰ型磨耗的充填体多位于重咬合接触区,因此磨耗量较大,发生Ⅱ型磨耗的充填体多位于轻咬合接触区或无直接接触区,因此磨耗量普遍低于Ⅰ型磨耗。除了以上两种主要的磨耗类型外,本研究还观察到7例酸蚀症患牙(BF组5个,Z350组2个),表现为牙齿磨耗量高于树脂材料,充填体逐渐突出于周围牙面,形成“树脂岛”,由于此种磨耗类型不能准确计算出树脂材料的磨耗量,因此在后期进行磨耗分析时将其排除。

牙齿接触减弱,承担的咀嚼压力相对降低,此时主要是食物引起的摩擦,使材料磨损速率下降并逐渐趋于平缓。本研究中的两种材料均存在Ⅰ型和Ⅱ型磨损,其中Ⅰ型磨耗量显著大于Ⅱ型磨耗量。Palaniappan等[26]在电子显微镜下观察到复合树脂充填体在重咬合接触区的磨耗以疲劳磨耗为主,材料易产生裂纹、折断,因此产生的磨耗量最大;在轻咬合接触区,树脂表面有大量因酸蚀产生的凹坑状缺损,填料暴露、脱落,磨耗量仅次于重咬合接触区;在非咬合接触区,树脂表面多为与食物排溢方向一致的浅划痕,磨耗量最小。本研究中发生Ⅰ型磨耗的充填体多位于重咬合接触区,因此磨耗量较大,发生Ⅱ型磨耗的充填体多位于轻咬合接触区或无直接接触区,因此磨耗量普遍低于Ⅰ型磨耗。除了以上两种主要的磨耗类型外,本研究还观察到7例酸蚀症患牙(BF组5个,Z350组2个),表现为牙齿磨耗量高于树脂材料,充填体逐渐突出于周围牙面,形成“树脂岛”,由于此种磨耗类型不能准确计算出树脂材料的磨耗量,因此在后期进行磨耗分析时将其排除。

本研究结果显示,当充填体位于重咬合接触区时BF组的磨耗量大于Z350组,分析原因一方面与两种材料的填料颗粒尺寸相关,Z350中填料颗粒为2 nm至1.4 μm,使其磨损后仍然能保持材料表面的光滑,降低材料的磨耗[31],且小颗粒的填料间距小,可以更好地保护相对较软的基质部分,减少磨耗的发生[32],有研究报道BF中存在10~50 μm的不规则填料颗粒,其表面更加粗糙[12, 33],进而增加材料的磨耗[11];另一方面,由于BF材料基质与传统纳米混合填料树脂相比,具有更高的吸水性,使其更容易发生降解,从而增加其磨耗[34],而且,释氟材料的填料颗粒在释氟过程中表面发生溶解,产生微间隙,降低了材料的微硬度[35]。本研究中位于重咬合接触区充填体的样本数量在总样本中所占比例较低,因此两种材料的总体平均耐磨性未显示差别。

综上所述,玻璃体的4年存留率和耐磨性均符合ADA标准,用于后牙 面重咬合接触区的直接充填修复时,玻璃体的耐磨性略逊于复合树脂,用于非重咬合接触区时,二者之间无明显差异。

面重咬合接触区的直接充填修复时,玻璃体的耐磨性略逊于复合树脂,用于非重咬合接触区时,二者之间无明显差异。

References

- 1.Gordan VV, Blaser PK, Watson RE, et al. A clinical evaluation of a giomer restorative system containing surface prereacted glass ionomer filler: results from a 13-year recall examination. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(10):1036–1043. doi: 10.14219/jada.2014.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manhart J, Chen HY, Hickel R. Clinical evaluation of the poste-rior composite Quixfil in class Ⅰ and Ⅱ cavities: 4-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Adhes Dent. 2010;12(3):237–243. doi: 10.3290/j.jad.a17551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oz FD, Ergin E, Canatan S. Twenty-four-month clinical perfor-mance of different universal adhesives in etch-and-rinse, selective etching and self-etch application modes in NCCL: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Appl Oral Sci. 2019;27:e20180358. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2018-0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koc Vural U, Meral E, Ergin E, et al. Twenty-four-month clinical performance of a glass hybrid restorative in non-carious cervical lesions of patients with bruxism: a split-mouth, randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24(3):1229–1238. doi: 10.1007/s00784-019-02986-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashi M, Wilson NH. Failure risk of posterior composites with post-operative sensitivity. Oper Dent. 2003;28(6):681–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heintze SD. Clinical relevance of tests on bond strength, microleakage and marginal adaptation. Dent Mater. 2013;29(1):59–84. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.07.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naoum S, Ellakwa A, Martin F, et al. Fluoride release, recharge and mechanical property stability of various fluoride-containing resin composites. Oper Dent. 2011;36(4):422–432. doi: 10.2341/10-414-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikemura K, Tay FR, Endo T, et al. A review of chemical-approach and ultramorphological studies on the development of fluoride-releasing dental adhesives comprising new pre-reacted glass ionomer (PRG) fillers. Dent Mater J. 2008;27(3):315–339. doi: 10.4012/dmj.27.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saku S, Kotake H, Scougall-Vilchis RJ, et al. Antibacterial acti-vity of composite resin with glass-ionomer filler particles. Dent Mater J. 2010;29(2):193–198. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2009-050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitagawa H, Miki-Oka S, Mayanagi G, et al. Inhibitory effect of resin composite containing S-PRG filler on Streptococcus mutans glucose metabolism. J Dent. 2018;70:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2017.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kakuta K, Wonglamsam A, Goto S, et al. Surface textures of composite resins after combined wear test simulating both occlusal wear and brushing wear. Dent Mater J. 2012;31(1):61–67. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2010-091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruivo MA, Pacheco RR, Sebold M, et al. Surface roughness and filler particles characterization of resin-based composites. Microsc Res Tech. 2019;82(10):1756–1767. doi: 10.1002/jemt.23342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Condo R, Cerroni L, Pasquantonio G, et al. A deep morphological characterization and comparison of different dental restorative materials. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:7346317. doi: 10.1155/2017/7346317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heintze SD, Faouzi M, Rousson V, et al. Correlation of wear in vivo and six laboratory wear methods. Dent Mater. 2012;28(9):961–973. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heintze SD, Ilie N, Hickel R, et al. Laboratory mechanical parameters of composite resins and their relation to fractures and wear in clinical trials: A systematic review. Dent Mater. 2017;33(3):e101–e114. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hickel R, Roulet JF, Bayne S, et al. Recommendations for conducting controlled clinical studies of dental restorative materials. Clin Oral Investig. 2007;11(1):5–33. doi: 10.1007/s00784-006-0095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leinfelder KF, Taylor DF, Barkmeier WW, et al. Quantitative wear measurement of posterior composite resins. Dent Mater. 1986;2(5):198–201. doi: 10.1016/S0109-5641(86)80013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehl A, Gloger W, Kunzelmann KH, et al. A new optical 3-D device for the detection of wear. J Dent Res. 1997;76(11):1799–1807. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760111201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palotie U, Eronen AK, Vehkalahti K, et al. Longevity of 2- and 3-surface restorations in posterior teeth of 25- to 30-year-old attending Public Dental Service: A 13-year observation. J Dent. 2017;62:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The American Dental Association. ADA acceptance program guidelines: resin based composites for posterior restorations[R]. Chicago: ADA Council on Scientific Affairs, 2001.

- 21.Lempel E, Toth A, Fabian T, et al. Retrospective evaluation of posterior direct composite restorations: 10-year findings. Dent Mater. 2015;31(2):115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demarco FF, Correa MB, Cenci MS, et al. Longevity of posterior composite restorations: not only a matter of materials. Dent Mater. 2012;28(1):87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hewlett ER, Orro ME, Clark GT. Accuracy testing of three-dimensional digitizing systems. Dent Mater. 1992;8(1):49–53. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(92)90053-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thongthammachat S, Moore BK, Barco MT 2nd, et al. Dimensional accuracy of dental casts: influence of tray material, impression material, and time. J Prosthodont. 2002;11(2):98–108. doi: 10.1053/jopr.2002.125192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palaniappan S, Bharadwaj D, Mattar DL, et al. Three-year randomized clinical trial to evaluate the clinical performance and wear of a nanocomposite versus a hybrid composite. Dent Mater. 2009;25(11):1302–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palaniappan S, Elsen L, Lijnen I, et al. Nanohybrid and microfilled hybrid versus conventional hybrid composite restorations: 5-year clinical wear performance. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16(1):181–190. doi: 10.1007/s00784-010-0500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg AJ, Rydinge E, Santucci EA, et al. Clinical evaluation methods for posterior composite restorations. J Dent Res. 1984;63(12):1387–1391. doi: 10.1177/00220345840630120901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.da Rosa Rodolpho PA, Cenci MS, Donassollo TA, et al. A clinical evaluation of posterior composite restorations: 17-year findings. J Dent. 2006;34(7):427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson NHF, Norman RD. Five-year findings of a multiclinical trial for posterior composite. J Dent. 1991;19(3):153–159. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(91)90005-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satou N, Khan AM, Satou K, et al. In-vitro and in-vivo wear profile of composite resins. J Oral Rehabil. 1992;19(1):31–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1992.tb01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salgado VE, Cavalcante LM, Silikas N, et al. The influence of nanoscale inorganic content over optical and surface properties of model composites. J Dent. 2013;41(Suppl 5):e45-53. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim BS, Ferracane JL, Condon JR, et al. Effect of filler fraction and filler surface treatment on wear of microfilled composites. Dent Mater. 2002;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0109-5641(00)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garoushi S, Vallittu PK, Lassila L. Characterization of fluoride releasing restorative dental materials. Dent Mater J. 2018;37(2):293–300. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2017-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonulol N, Ozer S, Sen Tunc E. Water sorption, solubility, and color stability of giomer restoratives. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2015;27(5):300–306. doi: 10.1111/jerd.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park CA, Hyun SH, Lee JH, et al. Evaluation of polymerization in fluoride-containing composite resins. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2007;18(8):1549–1556. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]