Abstract

The corpus luteum is a transient endocrine gland that synthesizes and secretes the steroid hormone, progesterone, which is vital for establishment and maintenance of pregnancy. Luteinizing hormone (LH) via activation of protein kinase A (PKA) acutely stimulates luteal progesterone synthesis via a complex process, converting cholesterol via a series of enzymatic reactions, into progesterone. Lipid droplets in steroidogenic luteal cells store cholesterol in the form of cholesterol esters, which are postulated to provide substrate for steroidogenesis. Early enzymatic studies showed that hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) hydrolyzes luteal cholesterol esters. In this study, we tested whether HSL is a critical mediator of the acute actions of LH on luteal progesterone production. Using LH-responsive bovine small luteal cells our results reveal that LH, forskolin, and 8-Br cAMP induced PKA-dependent phosphorylation of HSL at Ser563 and Ser660, events known to promote HSL activity. Small molecule inhibition of HSL activity and siRNA-mediated knock down of HSL abrogated LH-induced progesterone production. Moreover, western blotting and confocal microscopy revealed that LH stimulates phosphorylation and translocation of HSL to lipid droplets. Furthermore, LH increased trafficking of cholesterol from the lipid droplets to the mitochondria, which was dependent on both PKA and HSL activation. Taken together, these findings identify a PKA/HSL signaling pathway in luteal cells in response to LH and demonstrate the dynamic relationship between PKA, HSL, and lipid droplets in luteal progesterone synthesis.

Keywords: Steroidogenesis, Protein kinase A, luteinizing hormone, Hormone Sensitive Lipase, Corpus Luteum

Introduction

The corpus luteum is an ovarian endocrine gland that synthesizes and secretes the steroid hormone, progesterone, which is essential for the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy. Insufficient progesterone secretion early in the first trimester is associated with pregnancy loss and is attributed to premature loss of luteal function (1). To further highlight the significance of steroidogenesis, progesterone also serves as a luteal cell survival factor (2). Late in the follicular phase, the anterior pituitary gland synthesizes and secretes the gonadotropin, luteinizing hormone (LH), which is responsible for follicular rupture and release of the ovum (3), referred to as ovulation. The process of ovulation initiates the development of the corpus luteum and capacity to produce progesterone. LH stimulates the differentiation of theca and granulosa cells of the ovulated follicle to form the small and large steroidogenic luteal cells, respectively, of the corpus luteum (4–6). Luteal cells respond to LH by activation of its cognate receptor, the LHCGR, and stimulation of adenylyl cyclase leading to increases in intracellular cAMP (7), activation of PKA, and ultimately stimulation of steroidogenesis (8, 9). Both the small and large luteal cells respond to LH stimulation, however, the small luteal cells are many times more responsive to LH and activators of the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway (10, 11) when compared to large luteal cells.

LH is critical for normal luteal function and is required for the long-term steroidogenic capacity of luteal cells by maintaining expression of critical components of the steroidogenic machinery (12, 13). Progesterone biosynthesis is a multi-step process, converting cholesterol via a series of enzymatic reactions into progesterone (13). Intracellular cholesterol is transported across the outer mitochondria membrane to the inner membrane using the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (STAR) (14). The conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone, catalyzed by the P450 side chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A1) located in the mitochondria (15), and its subsequent conversion to progesterone, catalyzed by 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD3B) present in the endoplasmic reticulum (16), do not appear to limit luteal progesterone secretion (17–20) with the possible exception at the earliest stages during formation of the corpus luteum. Luteal cells are unique from other steroidogenic tissues in that following differentiation they contain abundant amounts of the STAR protein and enzymes CYP11A1 and HSD3B, which are required for optimal progesterone biosynthesis. Therefore, a key step in luteal progesterone biosynthesis is cholesterol availability. Although steroidogenic cells can synthesize cholesterol de novo, a majority of the cholesterol in luteal cells comes from the blood in the form of lipoproteins (LDL and/or HDL). Lipoproteins are internalized either through receptor-mediated endocytic or selective cellular uptake (21), where cholesterol is sorted from lipoproteins within endosomes. Endosomal cholesterol is then trafficked to the mitochondrion for progesterone biosynthesis or stored as cholesterol esters in lipid droplets (16, 22).

Lipid droplets are unique organelles that serve as lipid reservoirs and are abundant in both small and large luteal cells (23, 24). Unlike adipose tissue and other tissues, the lipid droplets present in luteal cells are enriched with cholesterol esters and triglycerides (24). However, cholesterol esters stored in lipid droplets must first be hydrolyzed at the 3rd carbon of the cholesterol ring in order to make the stored cholesterol available for progesterone biosynthesis. Hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) also called Lipase E (LIPE)) is an intracellular neutral lipase that is expressed in wide variety of tissues, including adipocytes (25, 26), macrophages (27, 28), adrenal glands (29, 30), liver (31), testis (32, 33), and the ovaries (34), and displays a broad substrate specificity, hydrolyzing diacylglycerol, retinyl esters, and cholesterol esters (35). Different from other lipases, HSL activity is tightly regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events. Phosphorylation of HSL occurs at multiple sites, including Ser660 and Ser563, which stimulate catalytic activity specific for diacylglycerol and cholesteryl esters (36–39). In steroidogenic tissues hormonal activation of PKA stimulates the phosphorylation of HSL at Ser563 (40, 41), which may be responsible for the observed increase in neutral cholesteryl ester hydrolase activity. Studies with HSL-null mice revealed that knock-out of HSL resulted in decreased steroidogenesis in the adrenals and inhibited sperm production in the testis (32), suggesting that HSL is involved in the availability of cholesterol for adrenal and gonadal steroidogenesis. Shen et al. (42) reported an interaction between STAR and HSL in the rat adrenal following treatment with ACTH and that co-expression of STAR and HSL resulted in elevated HSL activity and mitochondrial cholesterol content. In mouse Leydig cells depletion of HSL affected lipoprotein-derived cellular cholesterol influx, diminished the supply of cholesterol to the mitochondria, and resulted in the repression of STAR expression and steroidogenesis (41). In contrast, an increase in HSL elevated liver X receptor (LXR) ligands, which promoted STAR expression and steroidogenesis. While the evidence points to an important role for HSL in steroidogenesis, there is a paucity of information concerning the role of HSL in the regulation of luteal steroidogenesis (43).

Because luteal cells have abundant cholesterol ester-containing lipid droplets we hypothesize that LH-induced cAMP/PKA signaling pathways in luteal cells regulate HSL phosphorylation and association with lipid droplets, events which are necessary for steroidogenesis. In the present study we observed that LH and activators of PKA signaling stimulated the phosphorylation of HSL and localization of HSL with lipid droplets. Using chemical and genetic approaches we observed that HSL was essential for LH-stimulated progesterone synthesis. Other approaches revealed that PKA and HSL were vital for trafficking of cholesterol from lipid droplets to the mitochondria for LH-induced progesterone production.

Methods and Materials

Reagents

Penicillin G-sodium, streptomycin sulfate, HEPES, bovine serum albumin (BSA), Deoxyribonuclease l, fetal bovine serum (FBS), Tris-HCl, sodium chloride, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), sodium fluoride, Na4O2O7, Na3VO4, Triton X-100, Glycerol, dodecyl sodium sulfate, β-mercaptoethanol, bromophenol blue, Tween-20, paraformaldehyde and Mayer’s hematoxylin acetone were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The phosphate buffer solution, DMEM (Calcium-free, 4.0 g/L glucose), Penicillin Streptomycin Solution, trypan blue, 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) kit and Lipofectamine RNAimax were purchased from Invitrogen Corporation (Thermo Fisher, Carlsbad, CA). The Opti-MEM, M199 culture media, and gentamicin sulfate were purchased from Gibco (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Collagenase was purchased from Atlanta Biologicals (Flowery Branch, GA, USA). No. 1 glass coverslips, microscope slide, and Chemiluminescent substrate (SuperSignal West Femto) were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Fluoromount-G and clear nail polish were purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA, USA). Bovine LH was purchased from Tucker Endocrine Research Institute and forskolin, HDL, and Phorbol-12-Myristate-13-acetate (PMA) were purchased from EMD Millipore (Burlington, MA, USA). Bio-Rad protein assay was purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) and the non-fat milk was from local Kroger (Cincinnati, OH, USA). The siHSL (ON-TARGETplus Custom siRNA (CTM-385778; HOUSF-000005)) were designed and purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA). The 8-Br-cAMP was purchased from Tocris (Bristol, United Kingdom). Aminoglutethimide was purchased at TCI Chemicals (Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan). TopFluor Cholesterol [23-(dipyrrometheneboron difluoride)-24-norcholesterol] was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit for progesterone was purchased from DRG International, Inc (Springfield, NJ, USA). The reagent CAY10499 was purchased at Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). All antibodies used in the study are found in Table 1.

Table 1:

Characteristics of antibodies used for western blotting and microscopy

| Antibody name | Dilution ratio | Species specificity | Source | Supplier (distributor, town, country) | Cat. No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSL | 1:1000, 1:2002 | Mouse | Rabbit pAB | Cell Signaling (Boston, MA, USA) | 4107S |

| Phospho-HSL (Ser563) | 1:1000, 1:2002 | Mouse | Rabbit pAB | Cell Signaling | 4139S |

| Phospho-HSL (Ser660) | 1:1000 | Mouse | Rabbit pAB | Cell Signaling | 4126S |

| Phospho-PKA Substrate | 1:1000 | Mouse | Rabbit pAB | Cell Signaling | 9624 |

| PLIN2/ADFP | 1:1000 | Mouse | Rabbit pAB | Novus Biologicals (Centennial, Colorado, USA) | NB110–40877 |

| PLIN3 | 1:1000 | Mouse | Rabbit pAB | Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom) | 47638 |

| STAR | 1:10000 | Mouse | Rabbit pAB | Abcam | ab96637 |

| CYP11A1 | 1:1000 | Mouse | Rabbit mAB | Cell Signaling | 14217 |

| HSD3B | 1:1000 | Mouse | Rabbit mAB | A gift from Dr. Ian Mason | |

| TOM20 | 1:100 | Mouse | Rabbit mAB | Cell Signaling | 42406S |

| TUBA | 1:10001 1:2002 | Mouse | Mouse mAB | Cell Signaling | T4026 |

| TUBB | 1:10001 | Mouse | Mouse mAB | Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) | 2144S |

| ACTB | 1:5000 | Bovine | Mouse mAB | Sigma | A5441 |

| HRP-linked | 1:10000 | Anti-rabbit | Jackson Research (West Grove, PA, USA) | 111035003 | |

| HRP-linked | 1:10000 | Anti-mouse | Jackson Laboratory | 115035205 | |

| Alexa Fluor 594 | 1:500 | Anti-rabbit | Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA) | A-11080 | |

| DyLight 405 | 1:500 | Anti-mouse | Jackson Laboratory | 115-475-166 | |

| BODIPY 493/503 | 20 μM | Thermo Fisher | D3922 | ||

| TopFluor Cholesterol | 5 μM | Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, Alabama, USA) | 810255 |

Diltuion used for Western Blotting

Diltuion used for Confocal Microscopy

Hormone Sensitive Lipase (HSL); Protein Kinase A (PKA); Perilipin (PLIN); Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (STAR); Cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A1); 3beta-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD3B); Mitochondrial import receptor subunit (TOM20); Beta-actin (ACTB; loading control); Beta-tubulin (TUBB; loading control); Alpha-tubulin (TUBA).

Tissue collection, luteal cell preparation, elutriation, and cell culture

Bovine ovaries were collected at a local slaughterhouse from first trimester pregnant cows (fetal crown-rump length < 10 cm). The ovaries were immersed in ice cold PBS and transported to the laboratory at 4 °C. Using sterile technique, the corpus luteum was surgically dissected from ovary and cut into slices using a microtome and surgical scissors. Tissue pieces were dissociated using collagenase (103 U/mL) in basal medium (M199 supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin G-sodium, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, and 10 μg/ml gentamicin sulfate). For all experiments, dispersed luteal cells were enriched for small luteal cells (SLC) and large luteal cells via centrifugal elutriation as previously described (44). Cells with a diameter of 15–25 μm were classified as small luteal cells (purity of > 90% enriched small luteal cells), and cells with diameter > 30 μm were classified as large luteal cells (purity of 50–90% enriched large luteal cells).

Granulosa and theca cell collection

Granulosa and theca cells were isolated from antral follicles (2–8 mm in diameter) from bovine ovaries collected at local slaughterhouse (JBS USA, Omaha, NE). Follicles were opened with a scalpel and the granulosa cells were gently scraped from the follicle wall using the blunt side of the scalpel and suspended in DMEM-F12 culture media. Cells were then washed twice in DMEM-F12. Cells were lysed with 100 μL cell lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor at stored and −20 °C.

After the granulosa cells were removed, the theca were removed from surrounding stroma and placed in DMEM-F12 culture media. The theca tissue was suspended in medium containing 103 IU/mL collagenase 2 (Atlanta Biologicals) and dispersed using constant agitation at 37 °C for 1 h. Dispersed theca cells were removed from the undigested tissue by filtration through a 70 μm mesh then washed by centrifugation three times at 150 rcf for 10 min. Red blood cells (RBC) were removed by suspending theca cells in 10 mL RBC lysis buffer at room temperature for 10 mins. Cells were then washed twice in DMEM-F12. Cells were lysed with 100 μL cell lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor at stored at −20 °C until protein extraction.

Microarray Analysis

We mined bovine gene expression arrays from NCBI GEO repository (GSE83524) to analyze expression of steroidogenic machinery in freshly isolated bovine granulosa (GC, n = 4) and theca (TC, n = 3) cells from large follicles and from purified preparations of bovine small (SLC, n = 3) and large (LLC, n = 3) luteal cells from mature corpora lutea. Details of the isolation and analysis were previously published (45, 46).

Immunohistochemistry

Ovaries were sliced and portions fixed in 10% formalin for 24 hours and then changed into 70% ethanol until embedded in paraffin. Tissues were cut into 4 μm sections and mounted onto polylysine-coated slides. Slides were deparaffinized through three changes of xylene and through graded alcohols to water and microwaved in unmasking solution (Vector H-3300) for antigen retrieval. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 min. Sections were incubated with anti-HSL as indicated in Table 1 and subsequently an anti-rabbit ABC (Vector PK-4001) and stained using a DAB detection kit (Vector SK-4100). Slides were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin, dehydrated through graded alcohols, and mounted with Fluoromount-G. Non-immune IgG from the host species was used as a control.

Luteal cell treatments with LH, forskolin, 8-Br cAMP, H89, and CAY10499

Enriched small or mixed cell cultures were plated in 12-well culture dishes at 5 × 105 cells/well and 2 × 105 cells/well, respectively. Cells were cultured in M199 supplemented with 5% FBS, 0.1% BSA and Penicillin Streptomycin Solution, at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% humidified air and 5% CO2. Prior to experiment, small or mixed luteal cells were rinsed with PBS and equilibrated for 2 h with fresh M199 culture media (0.1% BSA and Penicillin Streptomycin Solution). To determine the effects of LH and cAMP signaling on phosphorylation of HSL, cells were treated with vehicle alone, LH (1 – 100 ng/mL), forskolin (10 μM), or 8-Br cAMP (1 mM) for up to 240 min. Following incubation cell lysates were collected for western blotting.

Enriched small luteal cells were pre-treated with vehicle, H89 (PKA inhibitor; 20 or 50 μM), CAY10499 (HSL inhibitor; 0.1 – 5 μM) for 2 h. Following pre-treatments cells were stimulated with LH (10 ng/mL) for 4 h. Spent media was immediately collected and cell lysates were prepared and stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

Transfection of luteal cells with adenoviruses

The adenovirus (Ad) expressing β-galactosidase (Ad.βGal) (47) and the Ad expressing the endogenous green fluorescent protein (Ad.GFP) or the endogenous inhibitor of PKA (Ad.PKI) (48) were prepared as previously described. The Ad expressing hormone-sensitive lipase (Ad.HSL) was prepared as previously described (49). In brief, enriched small luteal cells were seeded into culture dishes or on coverslips for 24 hours prior to adenoviral infection. The Ad.GFP and Ad.PKI or Ad.βGal and Ad.PKI viruses were added to cell cultures in serum-free M199 for progesterone and confocal experiments, respectively. After 2 hours, the media was replaced with M199 enriched with 5% FBS and cultures maintained for an additional 48 h. For progesterone analysis, media was changed, and cells were equilibrated for 2 h prior to treatment with control (M199 medium) or LH (10 ng/mL) for 4 h. Incubation media was collected to determine progesterone concentrations and cell lysates were collected for Western blot analysis. For confocal experiments the media was changed, and cells were equilibrated for 2 h prior to treatment with control (M199 medium), LH (10 ng/mL), 8-Br cAMP (1 mM), for 0 to 6 h. Following incubation cells were prepared for confocal microscopy.

siRNA Knockdown of HSL

Hormone sensitive lipase was knocked down using specific HSL (LIPE) silencing RNA (siRNA) to determine the role of HSL on luteal progesterone production. In brief, enriched small luteal cell populations were transfected with Lipofectamine RNAimax alone (siCTL) or siHSL (ON-TARGETplus Custom siRNA (CTM-385778; HOUSF-000005)) for 6 h using Lipofectamine RNAimax in opti-MEM 1 culture medium. Following transfection, 5% FBS was added to culture media and maintained for 48 h. Successful knockdown of HSL was confirmed by western blot in each experiment. Following treatment with siCTL or siHSL, luteal cells were stimulated with LH (10 ng/mL) for 4 h. Spent media and protein were immediately collected and stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

Lipid Droplet Isolation

Using sterile technique, the corpus luteum was surgically dissected from the ovary and cut into slices using a microtome and surgical scissors. Luteal tissue punch biopsies (pooled to 2.5 g) were made using a 5 mm biopsy punch and equilibrated for 2 h in fresh culture medium prior to treatment with control media or 8-Br cAMP (1 mM) for 30 min. Tissue punches were washed cold in TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Minced tissue was resuspended in 10 mL tissue homogenate buffer (60% sucrose w/v in TE buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail) and homogenized with a Teflon Dounce homogenizer in a glass vessel. The post-nuclear supernatant (PNS) fraction was obtained after centrifugation at 2000 rcf for 10 min. The supernatant was loaded into a 30 mL ultracentrifuge tube and overlaid sequentially with 40%, 25%, 10%, and 0% sucrose w/v in TE buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails. Samples were centrifuged at 110,000 × g (ravg) for 30 min at 4 °C with no brake in a Beckman Coulter Avanti J-20 XP ultracentrifuge using an SW 32 Ti rotor. The lipid droplets concentrated in a yellow/white band at the top of the gradient were harvested and concentrated by centrifugation at 2000 rcf for 10 min at 4 °C using a modified protocol (50, 51).

Western Blotting Analysis

Following treatments, cells were immediately placed on ice and rinsed with 1 mL cold PBS to remove excess media. Cells were lysed with 50 μL cell lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM NaF, 20 mM Na4O2O7, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100, 10% Glycerol, 0.1% SDS, and 0.5% deoxycholate) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Pierce, Thermo Fisher). Cells were removed from culture dishes using a cell scraper and the cell lysates were sonicated at 40% power setting (VibraCell, Model CV188) to homogenize cell lysate. Following sonication, the cell lysate was centrifuged at 4 °C at 12,000 × g for 10 min. Protein in the supernatant was determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) per manufacturer’s protocol. Proteins (30 μg/sample) were resolved using 10% SDS-PAGE and then electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked and then incubated in primary antibody (Table 1) for 24 h at 4 °C for detection of total and phosphorylated proteins. Chemiluminescent substrate (SuperSignal West Femto; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was applied signals were visualized using a UVP Biospectrum 500 Multi-Spectral imaging system (UVP, Upland, CA, USA) and the percent abundance of immunoreactive protein was determined using densitometry analysis in VisionWorks (UVP). Total proteins were normalized to ACTB prior to calculation of fold induction. The ratio of phosphorylated HSL to total HSL was determined for each treatment and time point. Fold increases due to treatment (control versus LH) were then calculated.

Confocal microscopy

Sterile No. 1 glass coverslips (22 × 22 mm) were individually placed in each well of a 6-well culture dish. Enriched small luteal cell cultures were seeded at 5 × 105 cells/well. To determine the effects of LH on phosphorylation of HSL, cells were equilibrated in fresh culture medium with 1% BSA for 2 h prior to treatment with LH (10 ng/mL) or 8-Br cAMP (1 mM) for 30 min. To determine the effects of LH on colocalization of phospho- and total-HSL with lipid droplets, cells were equilibrated in fresh M199 media enriched with 1% BSA for 2 h prior to treatment with LH (10 ng/mL). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% humidified air and 5% CO2 for 30 min, until termination of experiment.

To terminate the experiment cells were fixed with 200 μL of 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. Cells were rinsed 3 times with 1 mL PBS following fixation and then incubated with 200 μL of 0.1% Triton-X in PBS-T (0.1% tween-20) at room temperature for 10 min to permeabilize the membranes. The permeabilized cells were rinsed with PBS and blocked in 5% BSA for 24 h at 4 °C. Coverslips were then rinsed, appropriate antibodies for co-localization (Table 1) were added, and incubated at room temperature for 60 min. Following incubation, coverslips were rinsed with PBS to remove unbound antibody. Coverslips were then incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies (Table 1) and the lipid droplet marker BODIPY493/503 (10 μM) at room temperature for 60 min. Coverslips containing labeled cells were rinsed and mounted to glass microscope slides using 10 μL Fluoromount-G (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Coverslips were sealed to glass microscope slides using clear nail polish and stored at −22 °C until imaging.

Experiments were performed to determine the effects of LH and HSL activity on the trafficking of cholesterol from lipid droplets to mitochondria. To accomplish this, we used confocal microscopy to follow the movement of TopFluor Cholesterol [23-(dipyrrometheneboron difluoride)-24-norcholesterol] (Avanti Polar Lipids), which has a fluorescent probe located on the cholesterol side-chain, from lipid droplets to mitochondria. Normally cholesterol enters the mitochondria where it is rapidly converted to pregnenolone by the cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme CYP11A1. In order to track TopFluor Cholesterol movement into mitochondria, cells were pre-treated with aminoglutethimide, an inhibitor of CYP11A1, to prevent cholesterol from exiting the mitochondria as pregnenolone following treatment. Mitochondrial TopFluor Cholesterol was colocalized to mitochondria using the mitochondria marker protein, TOM20.

Luteal cells were pre-treated with 5 μM TopFluor Cholesterol (Avanti Polar Lipids) for 48 h to allow incorporation in lipid droplets (24). Following incubation, cells were washed 3 times with PBS to remove unincorporated lipid probe from cells and equilibrated for 2 h in culture media. Cells were then pre-treated with aminoglutethimide (CYP11A1 inhibitor; 50 μM) for 1 h to allow TopFluor Cholesterol to accumulate in mitochondria after treatment with LH (10 ng/mL) or 8-Br cAMP (1 mM). To determine the effects of HSL on LH-induced mitochondrial TopFluor Cholesterol content, cells were pre-treated with aminoglutethimide and the HSL inhibitor CAY10499 (50 μM) for 1 h prior to treatment with LH or 8-Br cAMP. To determine the influence of PKA on LH-induced mitochondrial TopFluor Cholesterol, cells were transfected with Ad.βGal or Ad.PKI, as described above, prior to treatment with LH or 8-Br cAMP. For all treatment combinations, cells were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% humidified air and 5% CO2 until termination of experiment. To terminate the experiment cells were fixed (4% PFA), permeabilized (0.1% Triton-X in PBS-T), blocked (5% BSA), and immunolabelled as described above. Following immunolabeling, coverslips containing labeled cells were mounted to glass microscope slides using 10 μL Fluoromount-G (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Coverslips were sealed to glass microscope slides using clear nail polish and stored at −22 °C until imaging.

Images were collected using a Zeiss 800 confocal microscope equipped with a 63 × oil immersion objective (1.4 N.A) and acquisition image size of 1024 × 1024 pixel (101.31 μm × 101.31 μm). The appropriate filters were used to excite each fluorophore and emission of light was collected between 450 to 1000 nm. Approximately 20 cells were randomly selected from each slide and z-stacked (0.33 μm) images were generated from bottom to top of each cell. To determine the effects of LH on the phosphorylation of HSL z-stacked mages were converted to maximum intensity projections and processed utilizing Image J (National Institutes of Health) analysis software. Mean fluorescence intensity was determined as previously described (52–54). To determine the effects of LH on the colocalization of HSL with lipid droplets and TopFluor Cholesterol with mitochondria the JACoP plug-in was used in Image J software to determine the Manders’ overlap coefficient for each image as previously described (55) and transformed into percent colocalization by multiplying Manders’ overlap coefficient by 100 for all colocalization experiments.

Progesterone Analysis

Progesterone concentrations in culture media were determined using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (DRG International, Inc, Springfield, NJ, USA) per manufacturer’s protocol. Intra- and inter-assay coefficient of variation was 1.9% and 10.3%, respectively, across 18 assays.

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times each using cell preparations from separate dates of collection and all data are presented as the means ± SEM. The differences in means were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests to evaluate multiple responses, or by t-tests to evaluate paired responses. Two-way ANOVA was used to evaluate repeated measures with Bonferroni posttests to compare means. All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software from GraphPad Software, Inc.

Results

Expression of HSL, PLIN2 and the key components of steroidogenic machinery in the bovine ovary.

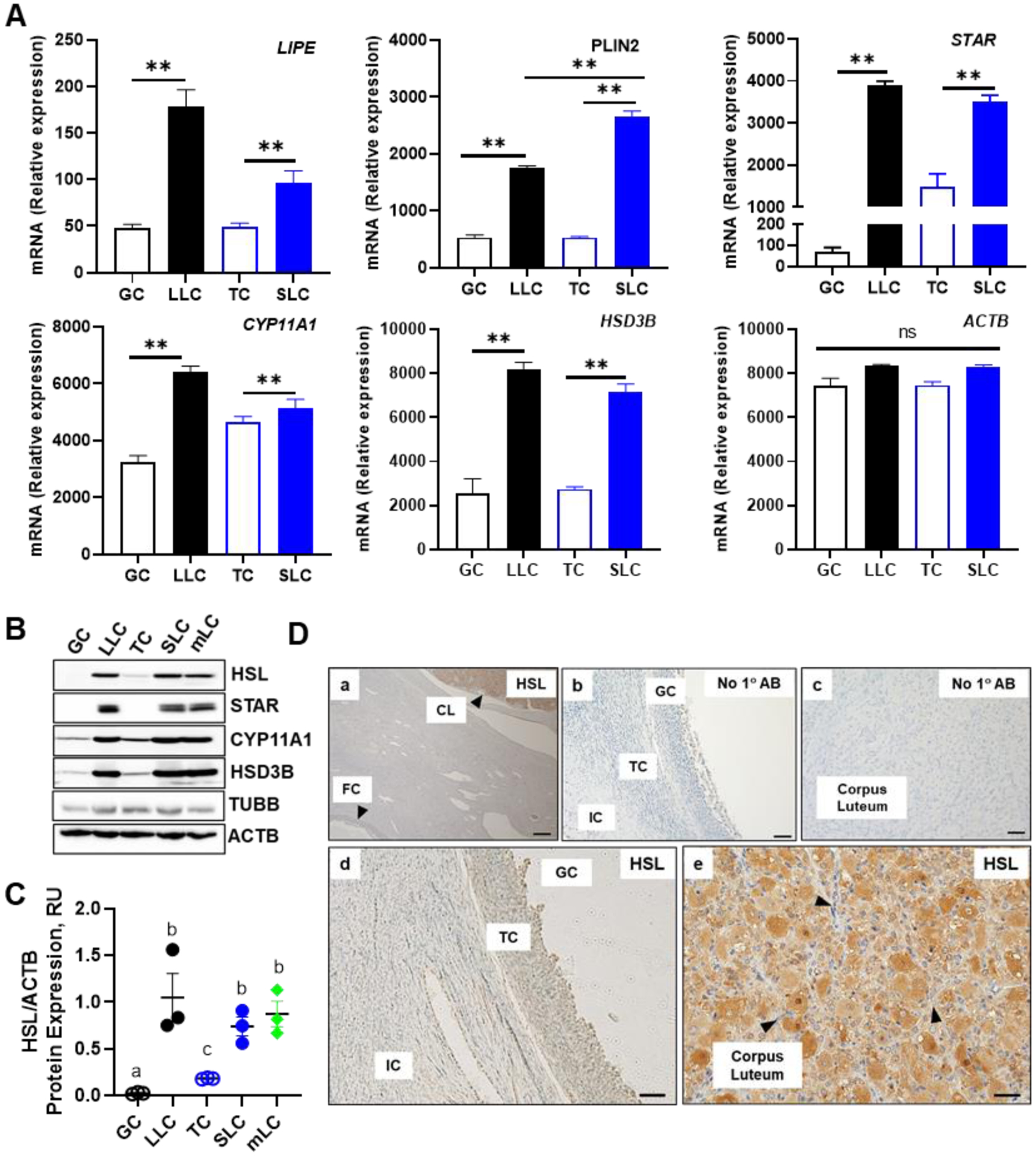

We mined bovine gene expression arrays from NCBI GEO repository (GSE83524) to analyze expression of transcripts for hormone sensitive lipase (LIPE/HSL), the lipid droplet coat protein Perilipin 2 (PLIN2), and components of the steroidogenic machinery in bovine follicular cells (granulosa and theca) and their highly differentiated steroidogenic luteal cell counterparts (large and small luteal cells, respectively) (45, 46). The LIPE/HSL mRNA transcripts were enriched 2-fold in small luteal cells compared to theca cell counterparts (P < 0.05; Figure 1A); and 2.7-fold in large luteal cells when compared to granulosa cells (P < 0.05; Figure 1A). In keeping with the presence of lipid droplets in luteal cells (23), large and small luteal cells had 2.3-fold and 4-fold greater PLIN2 transcripts than granulosa and theca cells, respectively (P < 0.05; Figure 1A). Moreover, STAR transcripts were elevated by 1.4 fold in small luteal cells compared to theca cells (P < 0.05; Figure 1A); however, we observed much greater transcript expression of STAR in large luteal cells (56 fold) when compared to granulosa cells (Figure 1A), which is in keeping with the conversion from an estrogen secreting granulosa cell to a progesterone manufacturing luteal cell. There was a slight increase (11%) in the expression of mRNA for CYP11A1 between theca and small luteal cells (P > 0.05), however, CYP11A1 transcripts were 2 fold greater in large luteal cells compared to granulosa cells (P < 0.05; Figure 1A). Moreover, we observed 1.6 fold and 2.2 fold greater transcript expression of HSD3B in small and large luteal cells when compared their theca and granulosa counterparts, respectively (P < 0.05; Figure 1A). By comparison, there was only a 12% difference in the expression of mRNA for ACTB amongst all cell-types (P > 0.05; Figure 1A).

Figure 1:

Expression of Hormone Sensitive Lipase (LIPE/HSL) and components of the steroidogenic machinery in the bovine follicular and luteal cells. Microarray analysis, Western blotting and immunohistochemistry was used to determine the expression of hormone sensitive lipase (LIPE/HSL) in bovine follicular (theca and granulosa) and luteal (small and large) cells. A, Microarray analysis of LIPE/HSL in bovine GC (n = 4; open black bar), TC (n = 3; open blue bar), SLC (n = 3; closed blue bars), and LLC (n = 3; closed black bars). B, Freshly isolated bovine granulosa cell (GC), large luteal cell (LLC), theca cell (TC), small luteal cell (SLC), and mixed luteal cells (mLC) were used to determine the expression of steroidogenic proteins. Representative western blot analysis of steroidogenic protein expression from bovine GC, LLC, TC, SLC, and mLC. Hormone sensitive lipase (HSL); Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (STAR); Cholesterol side‐chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A1); 3beta‐Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD3B); Beta‐actin (ACTB; loading control). C, Quantification of Western blot analysis of HSL in bovine GC, LLC, TC, SLC, and mixed LC (mean and SEM, n = 3. D, Representative immunohistochemistry micrographs showing expression of HSL in follicles and corpus luteum. Large arrows point to corpus luteum and follicle (a); Negative controls (b and c); HSL staining in GC and TC (d); HSL staining in corpus luteum. Arrows point to endothelial cells. (e). Micron bar represents 5 and 1 μm

The expression of the steroidogenic proteins (STAR, CYP11A1, and HSD3B) and HSL in freshly isolated granulosa and theca cells, enriched large and small luteal cells and mixed luteal cells is shown in Figure 1B. HSL was highly expressed in large, small and mixed luteal cells when compared to both theca and granulosa cells (P > 0.05). Further, there was no difference in HSL expression between luteal small or large luteal cells when compared to mixed luteal cells (P > 0.05; Figure 1B and 1C). Steroidogenic proteins, STAR, CYP11A1, and HSD3B were expressed in small, large, and mixed cells, and minimally expressed in theca and granulosa cells (Figure 1B).

The presence of HSL protein in bovine ovaries was also determined using Immunohistochemistry (Figure 1D). We observed that HSL was prominently expressed in the corpus luteum (Panels a and e) with less staining in stroma and granulosa and theca cells of the follicle (Panels a and d). The cytoplasm of steroidogenic small and large luteal cells (Panel e) was stained intensely; while staining in endothelial cells appeared less intense (panel e; arrows).

Effects of LH on phosphorylation of HSL.

Previous work in adipocytes demonstrated that β-adrenergic receptor-mediated activation of PKA-mediates the phosphorylation of HSL, which is required for activation and translocation of HSL from the cytoplasm to the surface of lipid droplets where it can access lipid substrates (49, 56).

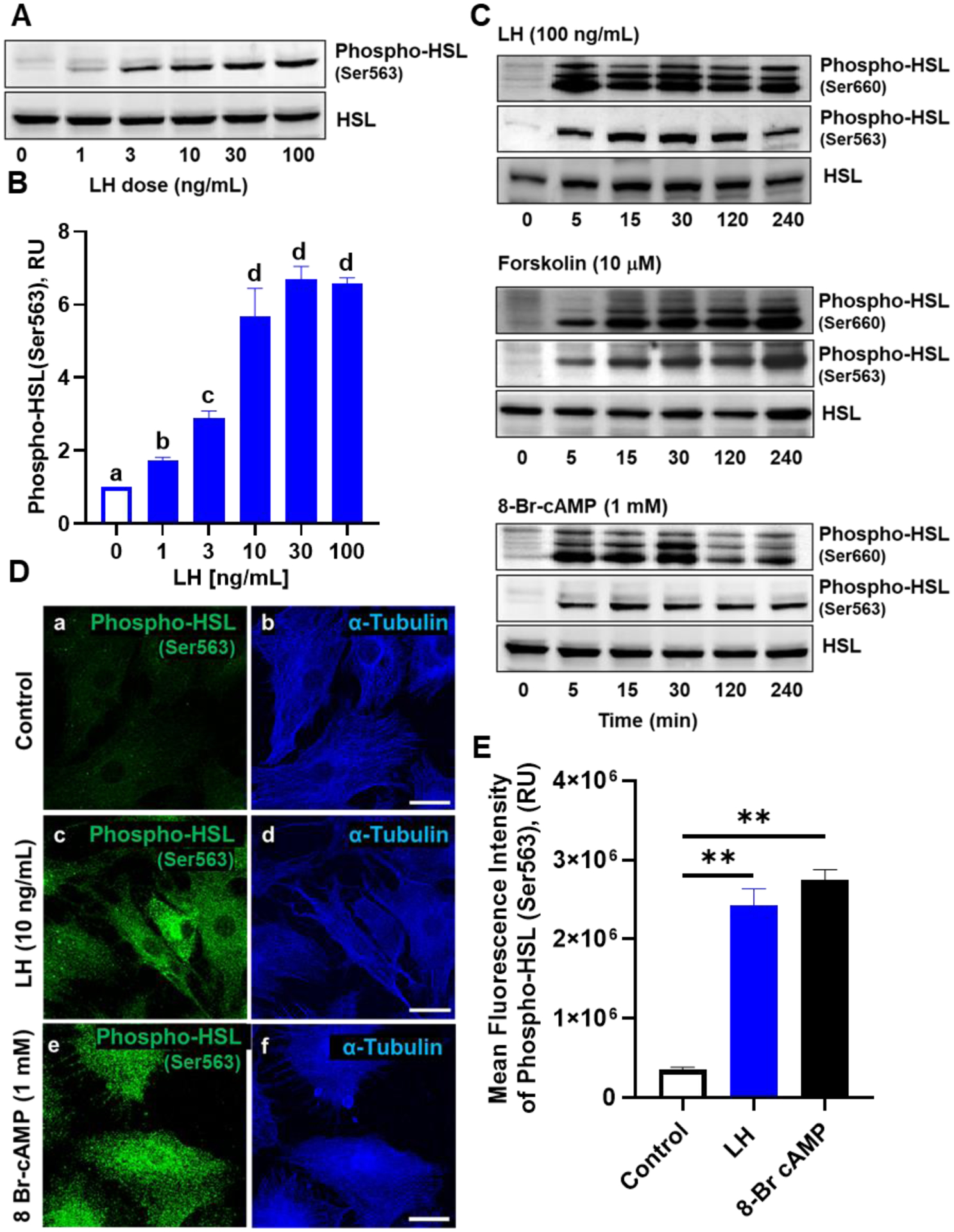

Enriched cultures of bovine luteal cells were utilized to determine the influence of LH and cAMP/PKA signaling on HSL phosphorylation. LH induced concentration-dependent increases in phosphorylation of HSL after 30 min of treatment with maximal stimulation at 10 ng/mL (Figures 2A and 2B). Luteal cells were treated for up to 240 min with LH, forskolin, or 8-Br cAMP to determine the temporal influence of LH and cAMP/PKA signaling on HSL phosphorylation (Figure 2C). LH increased the phosphorylation of HSL at both Ser660 and Ser563 residues (P < 0.05; Figure 2A–B) within 5 min and throughout the experimental period (Figure 2C). Moreover, treatment with forskolin, an activator of adenylate cyclase, or treatment with exogenous cAMP (8 Br-cAMP) stimulated rapid and sustained increases in phosphorylation of HSL at both Ser660 and Ser563 residues (Figure 2C).

Figure 2:

Effects of luteinizing hormone (LH) on phosphorylation of hormone sensitive lipase (HSL). Small luteal cells were treated for up to 240 minutes with luteinizing hormone (LH; 0‐100 ng/mL), forskolin (10 μM), or 8‐Br cAMP (1 mM) to determine the influence of LH on stimulation of hormone sensitive lipase (HSL). A, Representative western blot analysis for phospho‐ and total‐HSL protein expression in cells treated with increasing concentrations of LH (0‐100 ng/mL) for 30 minutes. B, Quantitative analysis of phospho‐HSL (Ser563) protein expression in cells treated with increasing concentrations of LH. Bars represent mean fold changes (means ± SEM). Bars with different lettersabcd differ significantly within treatment (P < .05). C, Representative western blot analysis for phospho‐ and total‐HSL protein expression in cells treated with LH, forskolin or 8‐Br cAMP. D, Small bovine luteal cells were treated with LH (10 ng/mL) or 8‐Br cAMP (1 mM) for 30 minutes. Representative micrograph showing the effects of LH or 8‐Br cAMP on phosphorylation of HSL (Ser563) in small luteal cells. Control (a‐b), LH (c‐d), and 8‐Br cAMP (e‐f). E, Quantitative analyses of the mean fluorescence intensity of phospho‐HSL (Ser563) in response to treatment with LH or 8‐Br cAMP. Bars represent means ± SEM (n = 3). **Significant difference between treatments as compared to Control, P < .01

Confocal microscopy was also employed to examine the phosphorylation of HSL in response to LH and exogenous cAMP (8 Br-cAMP). A representative micrograph showing the phosphorylation of HSL at Ser563 in response to LH and 8-Br cAMP are shown in Figure 2D. Treatment with LH increased the mean fluorescent intensity of phosphorylated HSL Ser563 by 583% when compared to control treated cells (Figure 2D–2E). Moreover, similar to LH, treatment with 8-Br cAMP resulted in a 673% increase in the mean fluorescent intensity of phosphorylated HSL Ser563 when compared to control treated cells (Figure 2D–E).

Effects of Protein Kinase A (PKA) on LH-induced phosphorylation of HSL and progesterone production.

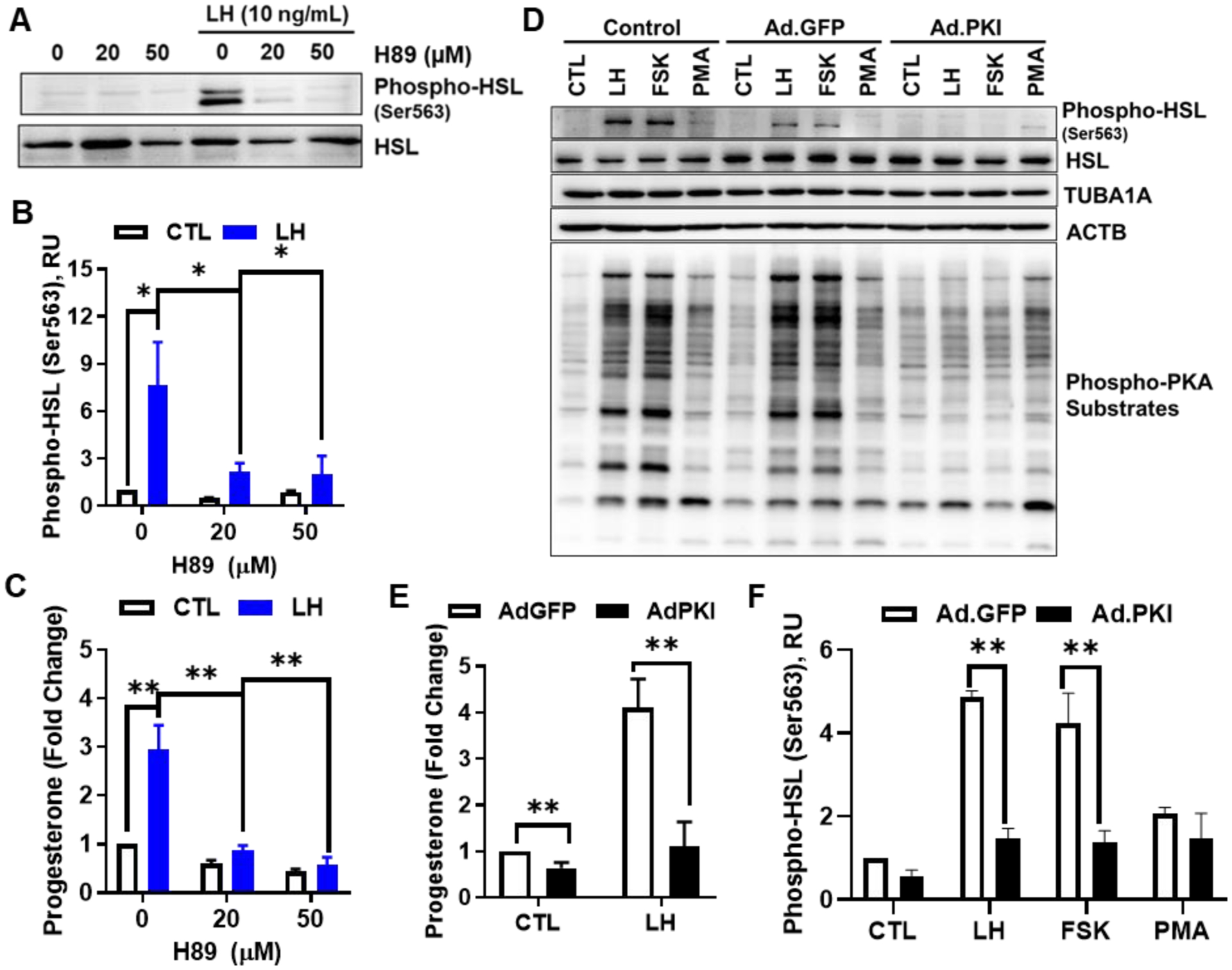

Two approaches were utilized to determine the influence of PKA on phosphorylation of HSL and progesterone production. First, we used a well-studied, commercially available small molecule inhibitor of PKA, H89, to determine the influence of PKA on activation of HSL and progesterone production (Figure 3). Pre-treatment with H89 prevented the LH-induced phosphorylation of HSL when compared to control cells (Figures 3A and 3B). Furthermore, this inhibition of HSL phosphorylation was accompanied by a complete inhibition of LH-induced progesterone production when compared to control cells (Figure 3C). Second, we used an adenovirus to express the endogenous inhibitor of PKA, Ad.PKI (48), which effectively blocks the action of PKA, to evaluate the effects of LH on the phosphorylation of HSL and progesterone production (Figure 3D). The effectiveness of Ad.PKI determined by monitoring PKA-mediated protein phosphorylation using a reliable PKA substrates antibody (Figure 3D). LH-stimulated, PKA-dependent phosphorylation of luteal PKA substrates was blocked by pre-treatment with Ad.PKI. The inhibitory effects of Ad.PKI on the response to LH was selective for PKA because treatment with Ad.PKI did not prevent the slight increases in immune-reactive proteins observed in response to PMA, a protein kinase C activator. Treatment of luteal cells with Ad.PKI also effectively inhibited LH and FSK-induced phosphorylation of HSL (P <0.05; Figures 3D and 3F) and LH-induced progesterone production when compared to control Ad.GFP transfected cells (P < 0.05: Figure 3E).

Figure 3:

Effects of Protein Kinase A (PKA) on luteinizing hormone (LH)‐induced HSL phosphorylation and progesterone production in small luteal cells. Panels A‐C: Luteal cells were pretreated with H89, and then, stimulated with LH (10 ng/mL). A, Representative western blot analysis for phospho‐ and total‐HSL protein expression in cells treated with H89 and LH. B, Densitometric analyses of phospho‐HSL (Ser563) protein expression obtained from cells treated with H89 in presence or absence of LH (10 ng/mL). C, Progesterone production by luteal cells pretreated with H89 and stimulated with control or LH for 4 hours. D, Replication‐deficient adenoviruses (Ad) containing the green fluorescent protein (Ad.GFP) and the endogenous inhibitor of PKA (Ad.PKI) were utilized to overexpress GFP or PKI in small luteal cells. After 48 hours, luteal cells were equilibrated and treated for 30 minutes with LH (10 ng/ml), forskolin (FSK, 10 μM), or the protein kinase C activator phorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate (PMA; 2 nM). Representative western blot analysis for phospho‐ and total‐HSL protein and total PKA‐substrates. E, Progesterone production by luteal cells transfected with Ad.GFP or Ad.PKI 4 hours posttreatment with control media (CTL) or LH. F, Densitometric analyses of phospho‐HSL (Ser563) protein expression obtained from luteal cells transfected with Ad.GFP (open bars) or Ad.PKI (closed bars) 1‐h posttreatment with LH, FSK, or PMA. Data represented as means ± SEM, n = 3. *Significant difference within treatment as compared to control, P < .05. **, P < .01

Effects of HSL on LH-induced progesterone production.

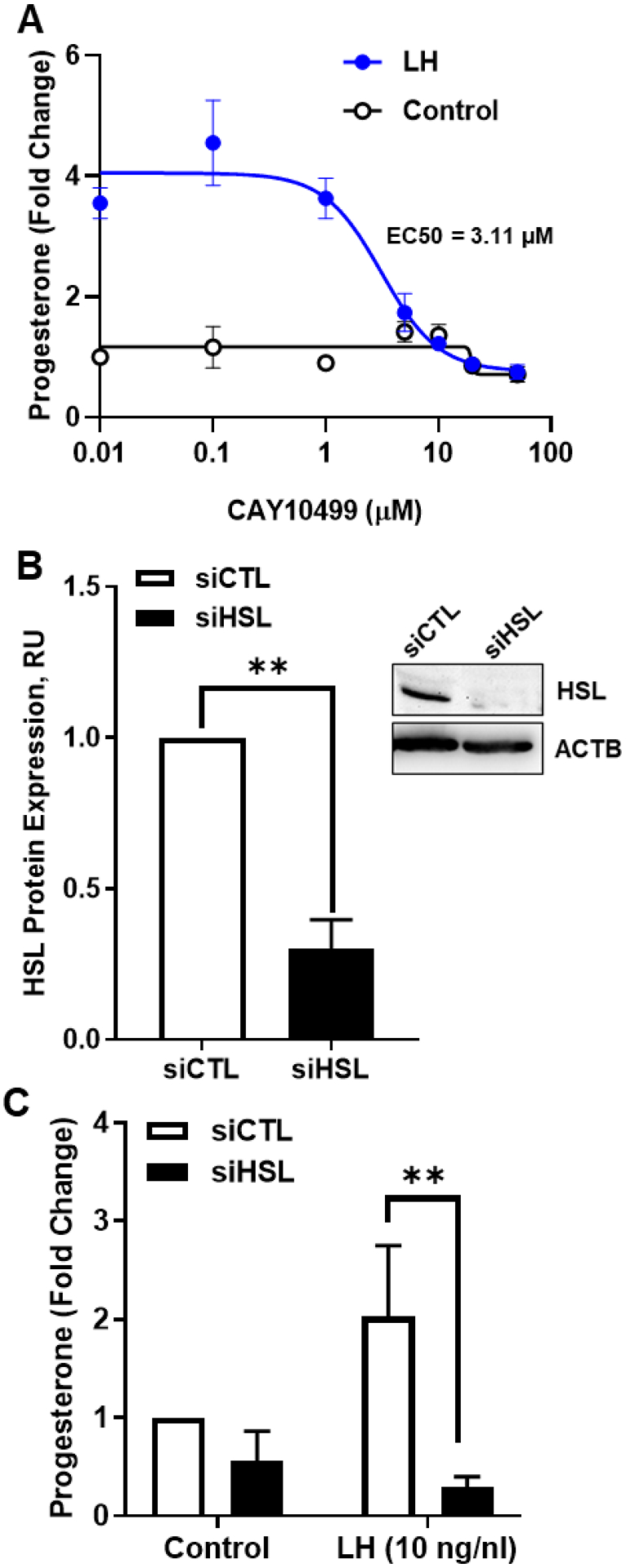

To determine whether HSL activity was required for the stimulatory effects of LH on progesterone we employed CAY10499, a selective small molecule inhibitor of HSL (57). Pre-treatment with CAY10499 resulted in concentration-dependent decreases in LH-induced progesterone production with an EC50 of 3.11 μM (Figure 4A).

Figure 4:

Effects of Hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) on luteinizing hormone (LH)‐induced progesterone production. A, Luteal cells were pretreated for 1 hour with increasing concentrations of CAY10499 (0 ‐ 100 μM), and then, treated for 4 hours with control (open black line) or LH (closed blue line). Progesterone was measured by ELISA. B, HSL mRNA was silenced using siRNA targeting HSL (siHSL) in small luteal cells. Representative western blot analysis (insert) showing expression of total‐HSL protein expression in siCTL and siHSL knockdown cells. Densitometric analyses of HSL protein expression obtained from siCTL (open bar) and siHSL (closed bar) validating successful knockdown. C, Small luteal cells were transfected with siCTL or siHSL and treated with control media (Control) or LH (10 ng/ml) for 4 hours. Progesterone was measured by ELISA. All data are represented as means ± SEM, n = 3. **Significant difference (P < .01) as compared to control

Another approach to determine the role of HSL employed siRNA specifically targeting bovine HSL. Western blotting revealed a 70% decrease in expression of HSL in siHSL-treated cells when compared to cells treated with a control siRNA (siCTL) (P < 0.05; Figure 4B). Treatment of luteal cells with siHSL resulted in a 44% reduction in basal progesterone secretion and a complete inhibition of LH-induced progesterone secretion when compared to control cells, (Figure 4C).

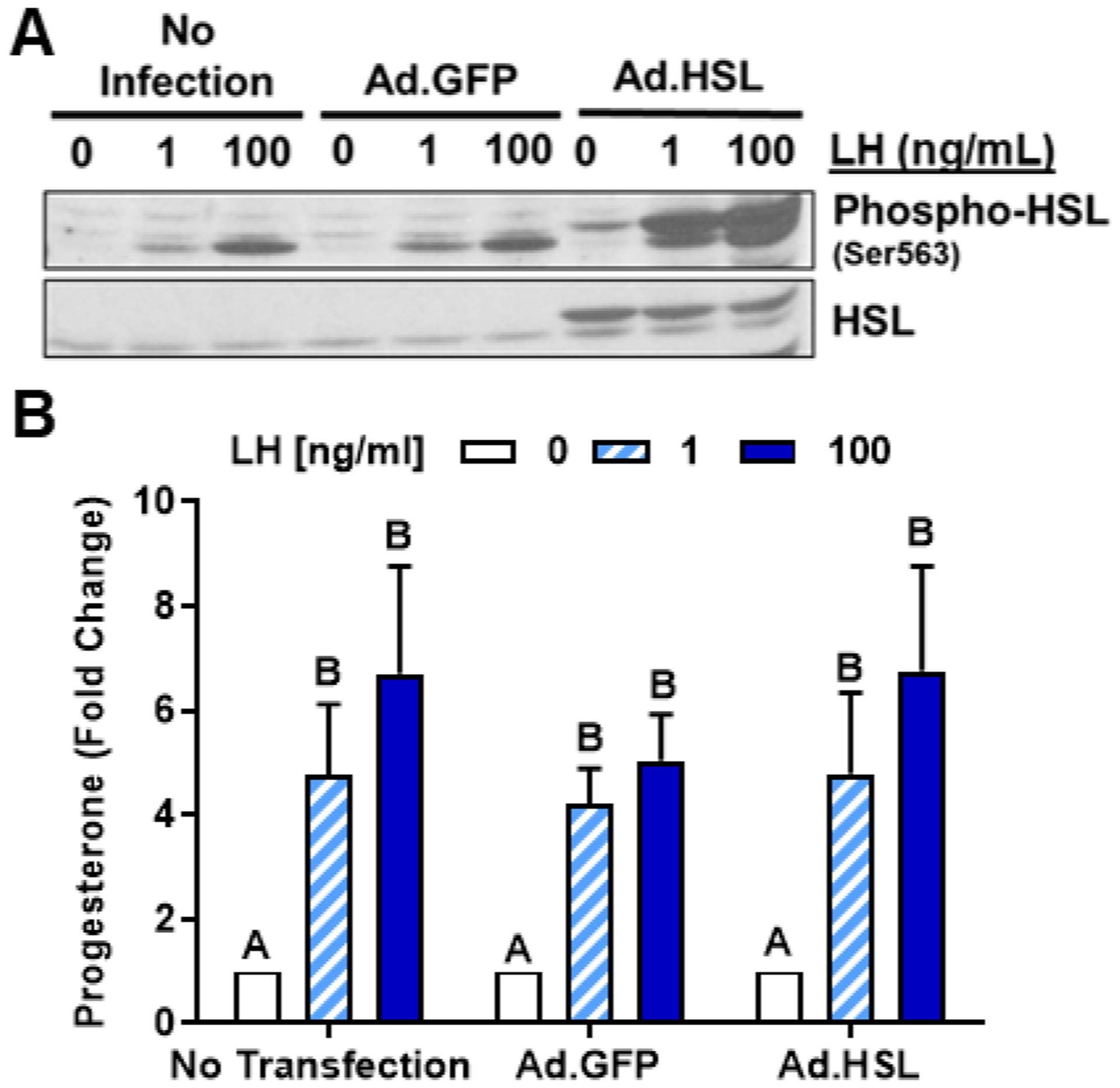

Because we observed that chemical inhibition of HSL and knockdown of HSL attenuated LH-induced progesterone production, we tested whether elevation of HSL levels would alter basal progesterone or the response LH. To accomplish this, we used an adenovirus to overexpress HSL (Ad.HSL, (49)) and measured luteal progesterone production after treatment with vehicle or LH. (Figure 5). Infection with Ad.HSL effectively increased the expression of total HSL compared to control or Ad.GFP treatment (Figure 5A). We also observed that both endogenous and the exogenously expressed HSL were phosphorylated in response to LH, but there was no difference in the ratio of phosphorylated HSL to total HSL following treatment with LH (P > 0.05, not shown). Adenoviral mediated overexpression of HSL did not influence LH-induced progesterone production regardless of LH concentration when compared to control Ad.GFP cells or uninfected control cells (P > 0.05; Figure 5B).

Figure 5:

Effects of Hormone Sensitive Lipase (HSL) on luteinizing hormone (LH)‐induced progesterone production in small luteal cells. Replication‐deficient adenovirus (Ad) containing the complete sequence of endogenous green fluorescent protein (GFP) cDNA (Ad.GFP) and Hormone Sensitive Lipase (HSL) cDNA (Ad.HSL) was utilized to overexpress GFP or HSL in luteal cells. A, Representative western blot analysis for phospho‐ and total‐HSL protein expression in cells transfected with Ad. GFP or Ad.HSL in response stimulation with LH (0‐100 ng/mL). B, Progesterone production by enriched small luteal cells transfected with Ad.GFP or Ad.HSL after 4 hours treatment with 0‐100 ng/mL LH. Bars represent mean fold changes (means ± SEM, n = 4). Bars with different lettersabcd differ significantly within treatment (P < .05)

Effects of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and the HSL inhibitor on LH-induced progesterone production.

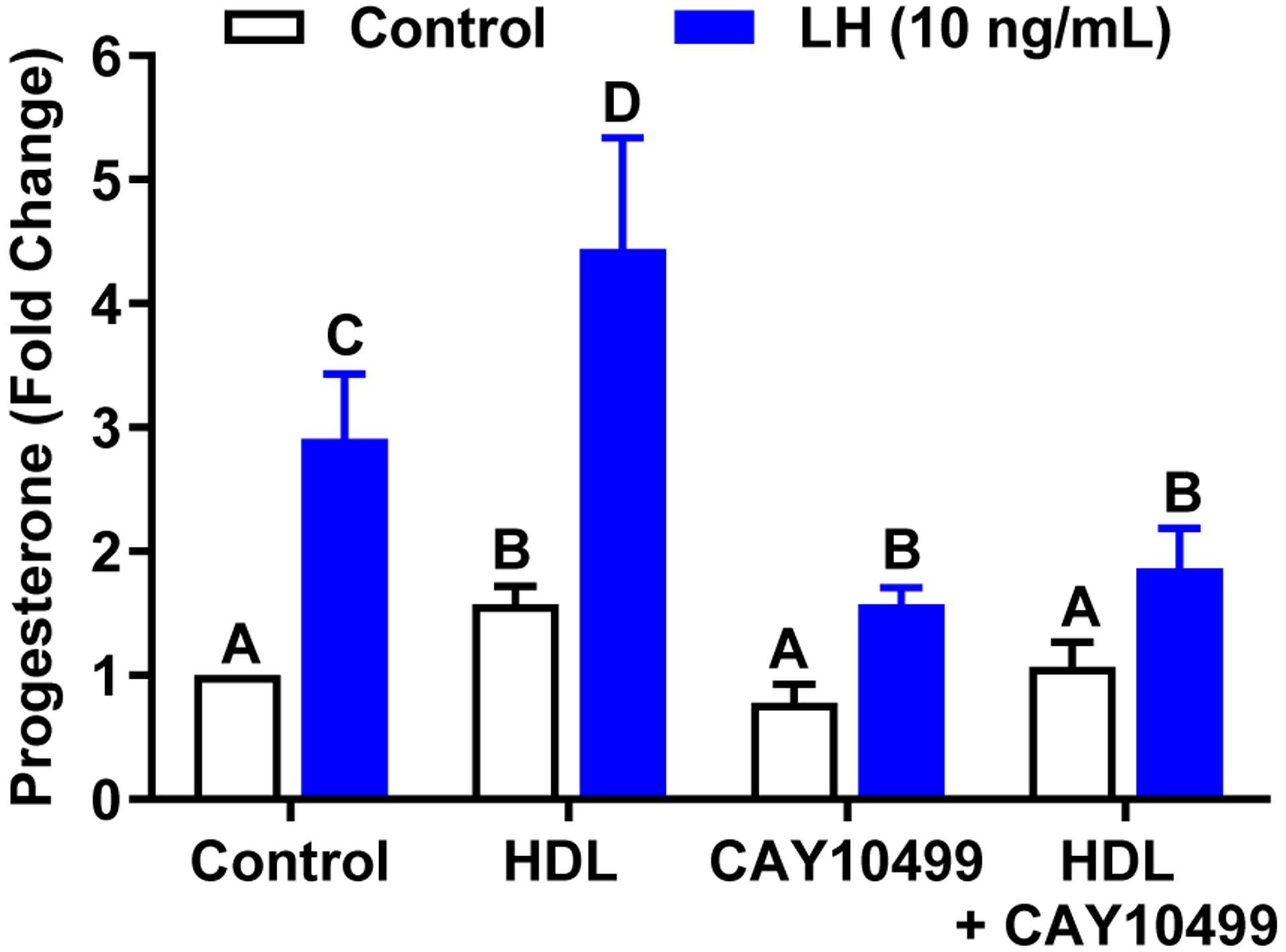

High density lipoproteins are a source of cholesterol for steroidogenesis in vivo (58) and can augment luteal steroidogenesis in vitro (59). We tested whether interruption of HSL activity would disrupt the stimulatory effect of HDL on luteal progesterone production. To accomplish this, small luteal cells were pre-treated with HDL (500 mg/mL), the HSL inhibitor CAY10499 (10 μM), or a combination of HDL and CAY10499 and then treated for 4 h with or without LH. Pretreatment with HDL increased basal and LH-induced progesterone production when compared to control cells (P < 0.05; Figure 6). Pretreatment with CAY10499 significantly inhibited the increase in progesterone in response to LH. However, the addition of HDL did not normalize LH-induced progesterone in the presence of CAY10499. (Figure 6).

Figure 6:

Lipoprotein‐mediated progesterone synthesis is prevented by CAY10499. The role of Hormone Sensitive Lipase (HSL) on processing in small luteal cells. To determine if HSL plays a role in HDL processing prior to progesterone biosynthesis, small luteal cells were pretreated with HDL (500 mg/mL), CAY10499 (10 μM), or a combination of HDL and CAY10499. Cells were then stimulated with control medium or LH for 4 hours. Data are represented as means ± SEM, n = 3. Bars with different lettersabcd differ significantly within treatment vs. control (P < .05)

Effects of LH on the association of HSL with lipid droplets.

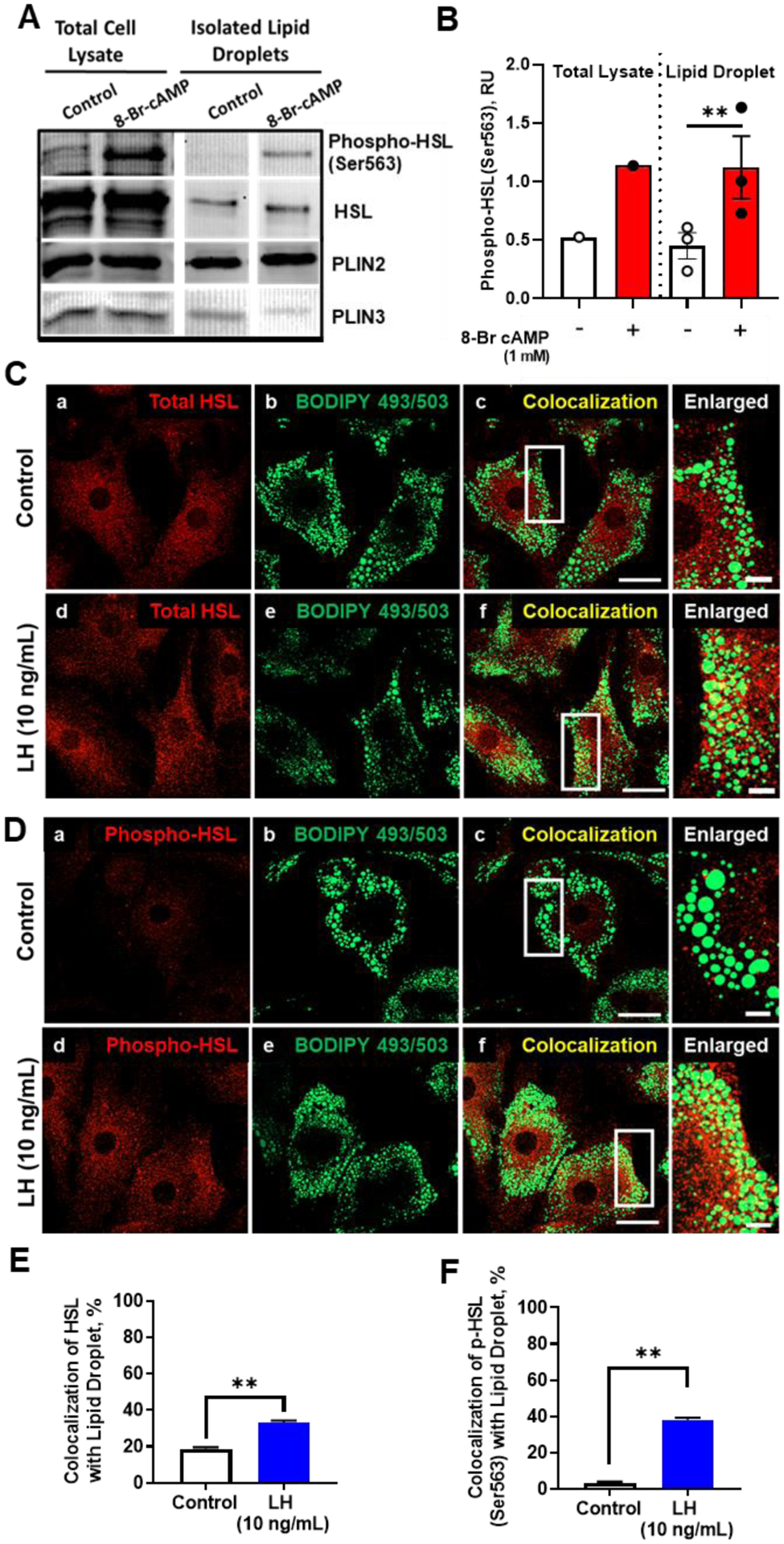

Our findings indicate that LH via activation of PKA-mediates the phosphorylation of HSL on residues required for activation and translocation of HSL from the cytoplasm to the surface of lipid droplets. We employed confocal microscopy and Western blotting to determine the effects of LH and a PKA activator on intracellular localization of phospho- and total-HSL luteal cells (Figure 7). Luteal tissue was treated with control media or 8-Br-cAMP (1 mM) for 30 min and tissue lysates and lipid droplets were prepared. We observed that similar to the responses observed in isolated luteal cells, phospho-HSL (Ser563) was increased in luteal tissue lysates following treatment with 8-Br-cAMP (Figure 7A). Furthermore, a 2.5-fold increase in phospho-HSL (Ser563) was observed in the isolated lipid droplet fraction following stimulation with 8-Br cAMP (Figure 7A and 7B), indicating that activation of HSL via LH/PKA pathway leads to its association with lipid droplets.

Figure 7:

Effects of LH on colocalization of phospho‐HSL and HSL with lipid droplets. A, Luteal tissue (punch biopsies) were treated with 8‐Br‐cAMP (1 mM) for 30 minutes and luteal lipid droplets (LDs) were isolated. Representative Western blot of whole tissue lysates and isolated LDs. B, Densitometric analyses of Western blots of phospho‐HSL (Ser563) from lysates and isolated LDs. C, Representative micrographs of HSL (a and d), BODIPY (b and e), colocalization of HSL and BODIPY (c and f), and enlarged image (white box corresponding to adjacent colocalization image) following 30 minutes treatment with control medium or LH. D, Representative micrographs of phospho‐HSL (Ser563) (a and d), BODIPY (b and e), colocalization of phospho‐HSL and BODIPY (c and f), and enlarged image (white box corresponding to adjacent colocalization image) following 30 minutes treatment with LH. E and F, Quantitative analysis of the colocalization of BODIPY with HSL (E) or with phospho‐HSL Ser563 (F) from control and treated cells. Data are represented as means ± SEM, n = 3. **Significant difference, P < .01. Micron bar represents 20 and 2 μm (inset)

Confocal microscopy was used to extend these observations. We treated cells with LH and determined whether HSL and phosphorylated HSL would localize with lipid droplets labeled with the lipid droplet dye BODIPY 493/503. There was a 1.7- and 10.9-fold increase in colocalization of HSL (Figure 7C and 7E) and phosphorylated HSL (Figure 7D and 7F), respectively, with lipid droplets after treatment with LH.

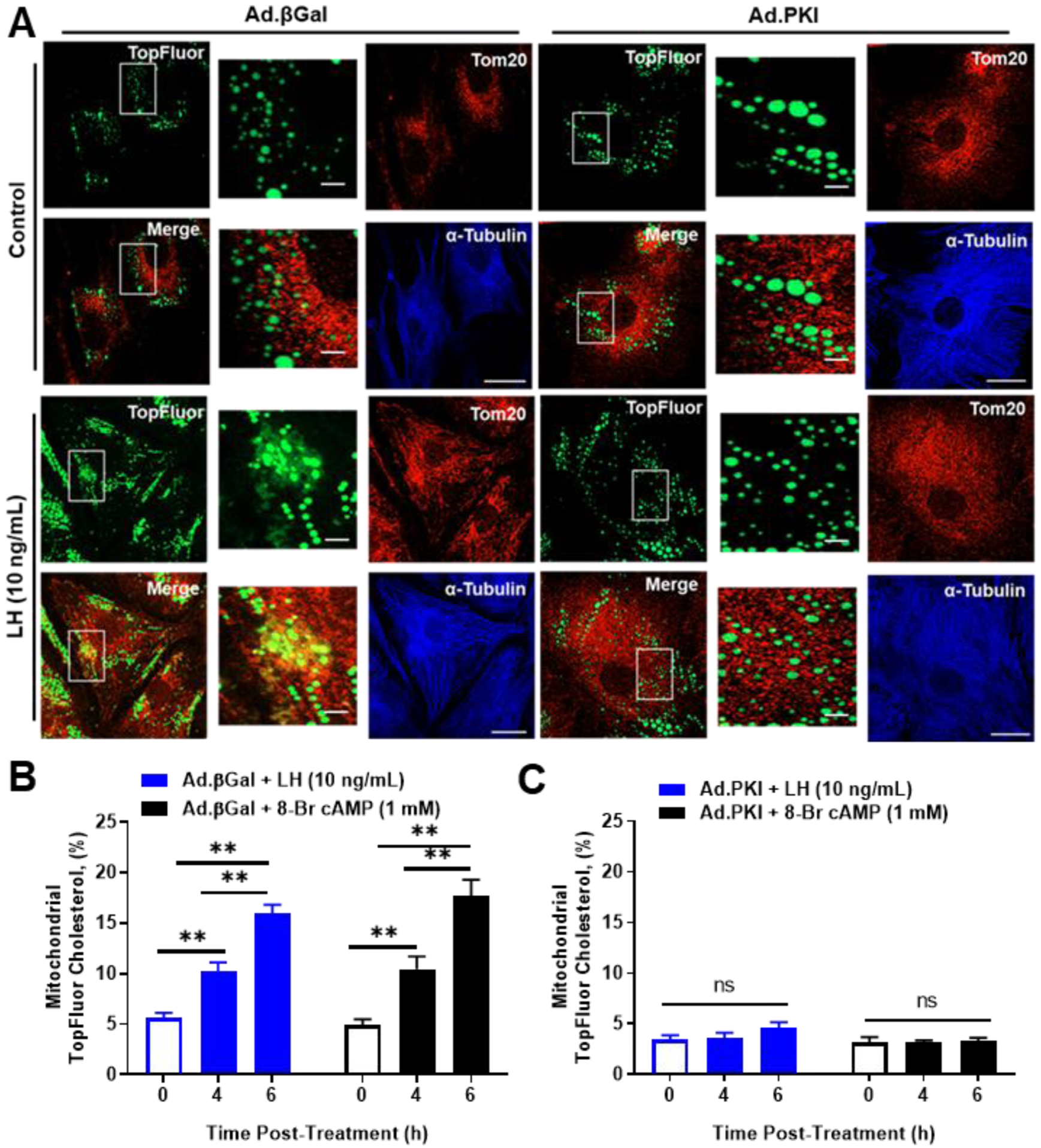

Effects of LH, PKA, and HSL on trafficking of cholesterol to mitochondria in small luteal cells.

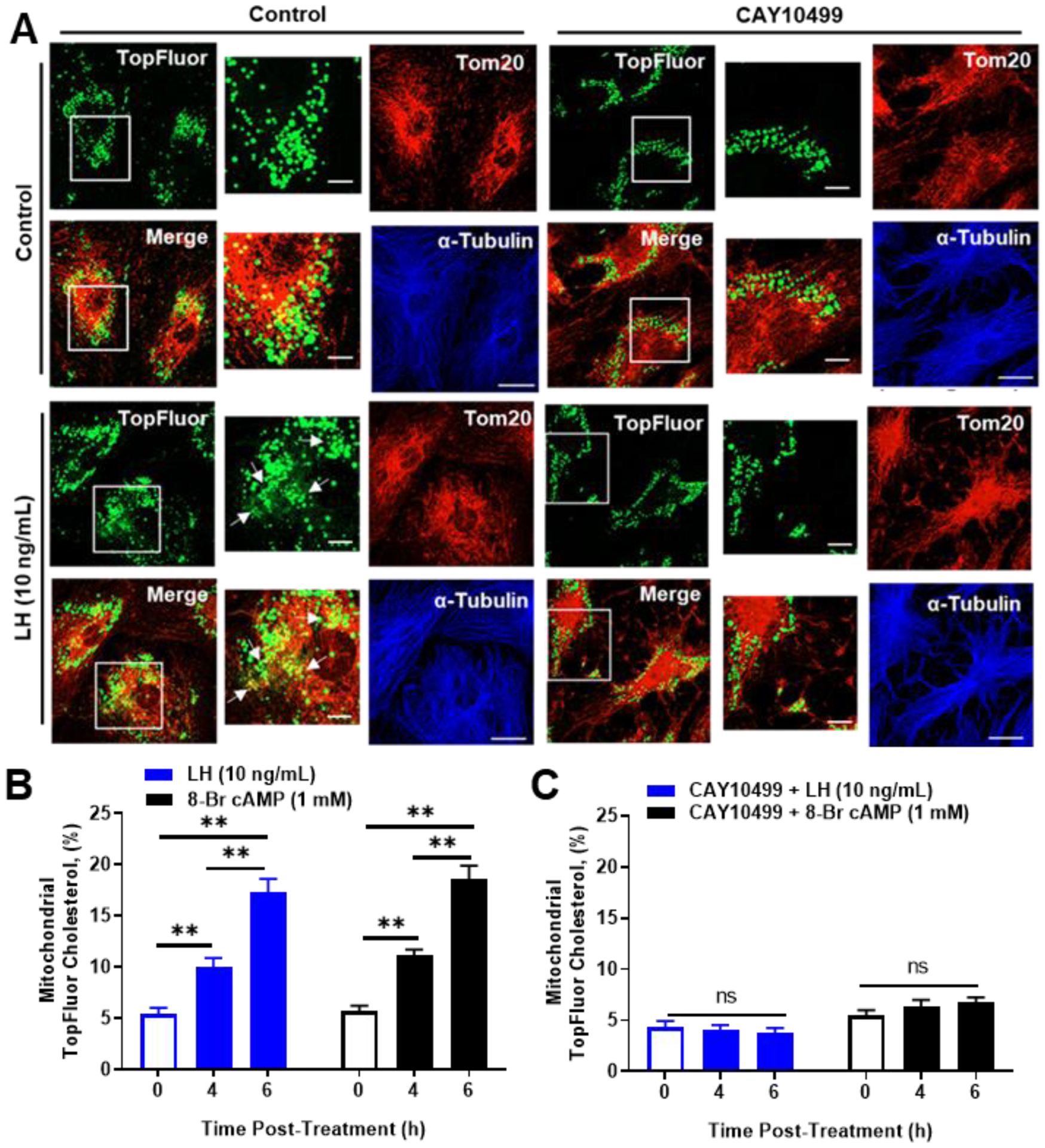

We performed experiments to determine whether hormone-stimulated HSL was required for trafficking of lipid droplet derived cholesterol esters to the mitochondria. To approach this, luteal cells were pre-equilibrated with TopFluor Cholesterol for 48 hr, a time point sufficient to distribute the fluorescent cholesterol into lipid droplets (Figure 8). TopFluor Cholesterol [23-(dipyrrometheneboron difluoride)-24-norcholesterol] is unique in that the fluorescent probe is located on the cholesterol side-chain. In order to track TopFluor Cholesterol movement into mitochondria, cells were pretreated with the CYP11A1 inhibitor aminoglutethimide (50 μM) to prevent cleavage of the fluorescent cholesterol side-chain and retain the TopFluor Cholesterol in the mitochondria. Control experiments were performed to determine the effects of aminoglutethimide and TopFluor Cholesterol on the phosphorylation of HSL and progesterone production. There was an expected decrease in LH-induced progesterone in cells pretreated with aminoglutethimide when compared to control cells (P < 0.05; Supplementary Figure 1A). Aminoglutethimide had no influence LH-induced phosphorylation of HSL at Ser 563 or phospho-PKA substrates regardless of concentration (Supplementary Figure 1A and 1B).

Figure 8:

Effects of Luteinizing hormone (LH) and CAY10499 on trafficking of cholesterol from lipid droplets to mitochondria. Small luteal cells were preloaded with TopFluor Cholesterol for 48 hours. Following cholesterol loading cells were treated with aminoglutethimide (50 μM) and/or CAY10499 (50 μM) for 1‐h prior to stimulation with Control medium, LH (10 ng/mL) or 8‐Br cAMP (1 mM). A, Representative micrographs of (left to right) of Controls: TopFluor Cholesterol, Tom20, merge of TopFluor Cholesterol, and α‐Tubulin from cells treated with Control medium or CAY10499. Representative micrographs of (left to right) of treatment with LH (6 hours): From (left to right) TopFluor Cholesterol, Tom20, merge of TopFluor Cholesterol, and α‐Tubulin from cells treated with LH or LH + CAY10499. Enlarged images correspond to white boxes in the adjacent image. B, Mean accumulation of TopFluor Cholesterol in controls and cells stimulated with LH or 8‐Br cAMP. D, Mean accumulation of TopFluor Cholesterol from cells pretreated with CAY10499, then stimulated with LH or 8‐Br cAMP). Data are represented as means ± SEM, n = 3. **Significant differences between treatments compared to control, P < .01. Micron bar represents 20 μm and 2 μm (inset)

Confocal microscopy was used to determine whether TopFluor Cholesterol was accumulated in mitochondria following LH treatment. We observed a significant increase in the percent co-localization of TopFluor Cholesterol with mitochondria (TOM20) following LH and 8-Br cAMP stimulation (Figure 8A and 8B). To determine the influence of HSL on LH-induced trafficking of cholesterol from lipid droplets to mitochondria, we inhibited HSL using CAY10499 prior to stimulation with LH. Treatment with CAY10499 prevented mitochondria accumulation of TopFluor Cholesterol with following LH and 8-Br cAMP stimulation (Figure 8A and 8C). To determine the influence of PKA on LH-induced trafficking of cholesterol from lipid droplets to mitochondria, small luteal cells were transfected with Ad.βGal (Ad.Control) or Ad.PKI prior to stimulation with LH. There was an increase in the percent co-localization of TopFluor Cholesterol with mitochondria following stimulation with either LH or 8-Br cAMP in luteal cells transfected with Ad.βGal (Figure 9A and 9B). In small luteal cells transfected with Ad.PKI, LH and 8-Br cAMP were unable to increase mitochondrial TopFluor Cholesterol (Figure 9A and 9C).

Figure 9:

Effects of Luteinizing hormone (LH) and PKA on trafficking of cholesterol from lipid droplets to mitochondria. Replication‐deficient adenoviruses (Ad) containing β‐galactosidase cDNA (Ad.βGal) and Protein Kinase Inhibitor cDNA (Ad.PKI) were utilized to overexpress βGal (control) or PKI in luteal cells. Following infection, small luteal cells were preloaded with TopFluor Cholesterol for 48 hours. Following cholesterol loading cells were treated with aminoglutethimide (50 μM) for 1‐h prior to stimulation with LH (10 ng/mL) or 8‐Br cAMP (1 mM). A, Representative micrographs of (left to right) of Controls: TopFluor Cholesterol, Tom20, merge of TopFluor Cholesterol, and α‐Tubulin from cells treated with Ad.βGal or Ad.PKI. Representative micrographs of (left to right) of cells treated with LH (6 hours): From (left to right) TopFluor Cholesterol, Tom20, merge of TopFluor Cholesterol, and α‐Tubulin from cells treated with LH + Ad.βGal or LH + Ad.PKI. Enlarged images correspond to white boxes in the adjacent image. B, Mean mitochondrial accumulation of TopFluor Cholesterol in Ad.βGal transfected cells treated with control, LH or 8‐Br cAMP. C, Mean mitochondrial accumulation of TopFluor Cholesterol in Ad.PKI transfected cells treated with control, LH or 8‐Br cAMP. Data are represented as means ± SEM, n = 3. **Significant difference between treatment as compared to control, P < .01; ns, P > .05; Micron bar represents 20 and 2 μm (inset)

Discussion

The current study was undertaken to examine the intracellular signaling events that lead to LH-induced progesterone biosynthesis in steroidogenic small luteal cells. Lipid droplets and HSL have been extensively studied in adipose tissue (25, 26, 29, 37) and to a lesser extent in the adrenal (29, 30, 42), testis (33, 41) and granulosa cells of the rat ovary (34), however, the relationship between HSL and lipid droplets is poorly understood in the corpus luteum, a transient but highly steroidogenic endocrine gland required for the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy. Using primary cultures of steroidogenic small luteal cells, we report that LH via cAMP/PKA signaling regulates the phosphorylation and the localization of HSL on lipid droplets. Furthermore, we establish that HSL is required for cholesterol trafficking from lipid droplets to mitochondria and progesterone biosynthesis in bovine luteal cells following stimulation with LH. These findings demonstrate a dynamic relationship between PKA, HSL, and the lipid droplets in luteal progesterone synthesis.

Whereas, lipid droplets have been reported in nearly all cell types, often times as indicators of pathological stress, the accumulation of lipid droplets in steroidogenic tissues appears to be required for adequate steroid biosynthesis and protection from lipotoxicity (60, 61). In the bovine ovary, the theca and granulosa cells of the ovarian follicle contain a limited number of small cytoplasmic lipid droplets that dramatically increase in number and size during differentiation into steroidogenic luteal cells (small luteal and large luteal cells) (24). Here, we show that compared to their granulosa and theca counterparts, the large and small steroidogenic luteal cells express elevated levels of transcripts and proteins for HSL, the lipid droplet protein PLIN2, and components of the steroidogenic machinery, STAR, CYP11A1, and HSD3B. Luteinization of bovine follicular cells in vivo leads to an accumulation of cytoplasmic lipid droplets as early as 3 days following ovulation and are present throughout the luteal phase (22). Thus, the development of the corpus luteum equips luteal cells with HSL, lipid droplets, and steroidogenic enzymes to provide high levels of progesterone in the luteal phase.

The luteotropic hormone LH activates PKA and other signaling molecules (62) during the ovulatory period that lead to the formation of a highly steroidogenic corpus luteum, which constitutively expresses the proteins required for producing the high levels progesterone required for maintenance of pregnancy. This includes STAR mRNA and protein, which are thought to be rate limiting for the stimulation of steroidogenesis (13). Herein, we show that HSL is acutely regulated by LH via a cAMP- and PKA-dependent process and is required for progesterone synthesis in small luteal cells. The evidence supporting this conclusion follows; first, LH, which activates the LHCGR, a Gs activating GPCR; forskolin, an adenylyl cyclase activator; and 8-Br-cAMP, a cAMP analogue; all stimulated the phosphorylation of HSL of Ser660 and Ser563. Second, inhibition of PKA signaling with H89, a small molecule inhibitor of PKA, or overexpression of the endogenous inhibitor of PKA suppressed the stimulatory effects of LH and forskolin on HSL phosphorylation and progesterone secretion. Third, our findings indicate that HSL is required for luteal progesterone synthesis. CAY10499, a small molecule inhibitor of HSL, and genetic knockdown of HSL with specific siRNA targeting HSL effectively reduced basal and abrogated LH-stimulated progesterone biosynthesis. Taken together these findings demonstrate that HSL is a vital mediator of the progesterone synthesis in luteal cells. While inhibition of HSL or reduced expression of HSL attenuates progesterone production, upregulation of HSL using adeno-viruses has no influence on basal or LH-induced progesterone production. The lack of response to over expression of HSL in steroidogenic luteal cells is similar to the failure of overexpression of HSL to alter lipolysis in adipose tissue (63).

In adipocytes, stimulation of PKA induces phosphorylation of the lipid droplet protein PLIN1 and HSL. Together, these events lead to the mobilization of HSL from the cytosolic compartment to lipid droplets where activated HSL can participate in hydrolysis of triglycerides (64). Using multiple approaches in the present study, we show that LH and 8-Br-cAMP increase phosphorylation and mobilization of HSL to luteal lipid droplets. Based on cellular fractionation followed by western blot analysis we observed that treatment of luteal tissue with the cAMP analogue 8-Br-cAMP increased the amount of phosphorylated HSL associated with the lipid droplet fraction. These findings are supported by observations that treatment with LH stimulated the co-localization of HSL and phosphorylated HSL with lipid droplets in luteal cells. Exactly how HSL interacts with luteal lipid droplets is presently unknown but appears to be different than the mechanism proposed for adipose tissue (35, 65). Whereas PLIN1 is the predominant lipid droplet coat protein and PKA substrate in adipocytes (66), bovine luteal cells express the lipid droplet coat proteins PLIN2 and PLIN3 (24), which are not considered targets for PKA (67). Furthermore, activation of PKA and recruitment of HSL to lipid droplets in adipocyte facilitates the hydrolysis of triglycerides, not cholesterol esters, subsequent to the activation of adipocyte triglyceride lipase, resulting in release of fatty acids and glycerol. Although luteal lipid droplets contain triglycerides as well as cholesterol esters (68), glycerol levels in luteal cells or media are not elevated following treatment with LH (unpublished data).

An adequate supply of cholesterol to the mitochondria is critical for optimal steroid biosynthesis. Luteal steroidogenic cells produce relatively large amounts of progesterone under both basal and LH-stimulated conditions in vitro, absent of exogenous cholesterol, pointing to an important role of intracellular lipid droplets as significant contributors to luteal steroidogenesis. Lipoproteins are an important source of exogenous cholesterol; low and high-density lipoproteins (LDL or HDL) are delivered into the cells through the LDL receptor or scavenger receptor class B, type I (SR‐BI), respectively. Once processed into the cells, lipoprotein-derived cholesterol is used for cellular activities or stored as cholesterol esters in lipid droplets (16). Because previous reports clearly demonstrate that lipoproteins, HDL in particular, support bovine luteal progesterone synthesis (59, 69), we tested whether treatment with exogenous lipoprotein would ameliorate progesterone synthesis in luteal cells treated with an inhibitor of HSL. In keeping with previous findings, we observed that HDL treatment enhanced basal and LH-stimulated progesterone production. However, HDL did not normalize progesterone production in the presence of the HSL inhibitor CAY10499. These findings show that mobilization of cholesterol from lipid droplets can be a preferred pathway for luteal steroidogenesis.

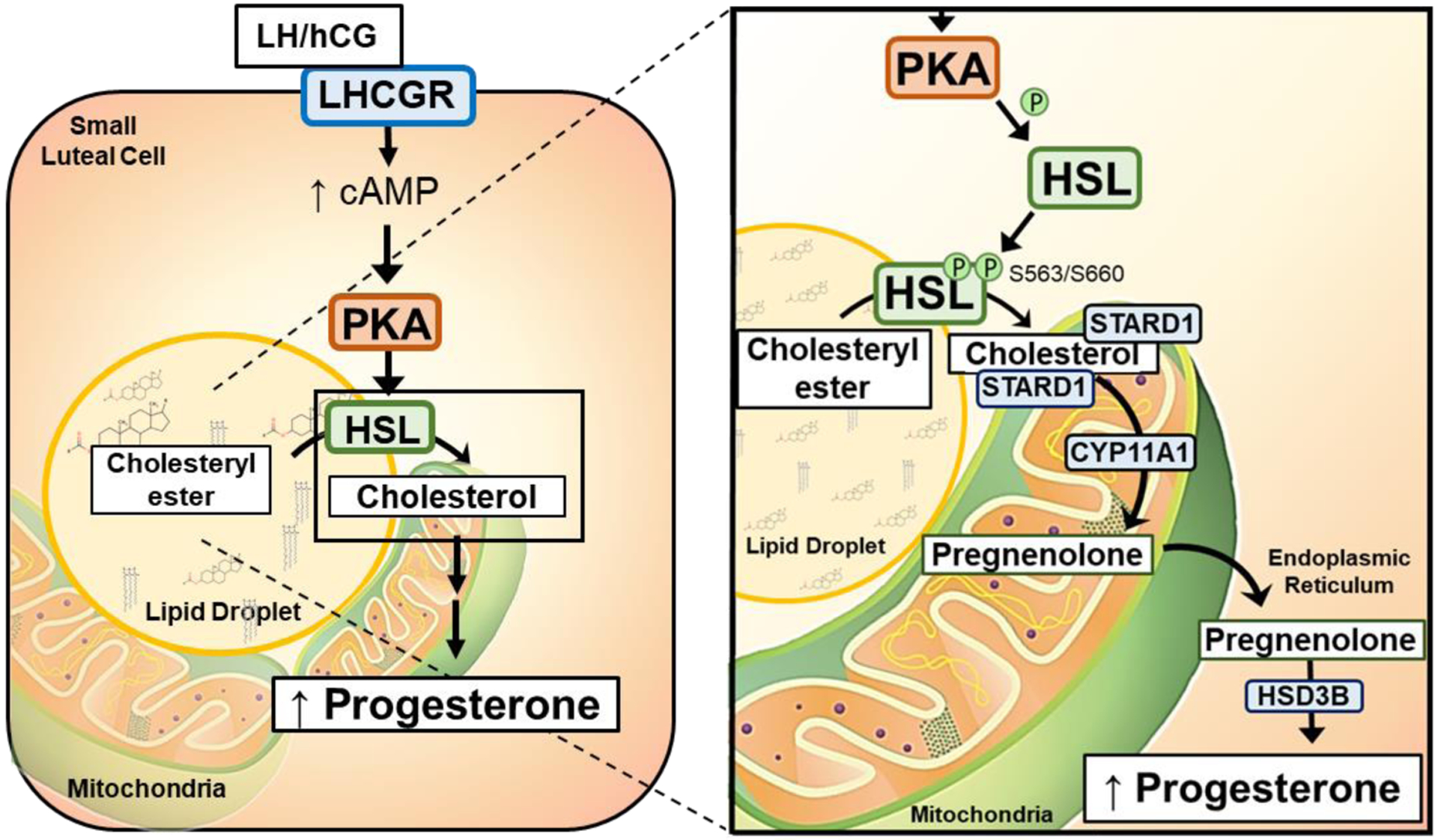

To gain further insight into the role of the HSL and lipid droplets in luteal steroidogenesis we employed a cellular model to better understand cholesterol trafficking in response to LH and PKA/HSL activation. To approach this, we labeled luteal cell lipid droplets with TopFluor Cholesterol, which has a fluorescent moiety located on the cholesterol side-chain and followed the trafficking of TopFluor Cholesterol into mitochondria. We observed that following treatment with LH or 8-Br-cAMP TopFluor Cholesterol, which was initially stored in lipid droplets, accumulates in mitochondria under conditions which inhibited cleavage of the cholesterol side-chain. These results suggest cholesterol esters stored in lipid droplets are mobilized in response to LH. Furthermore, our studies show that inhibition of either PKA or HSL prevents LH-induced accumulation of TopFluor Cholesterol with in mitochondria, indicating that PKA-induced activation of HSL is required for trafficking of cholesterol from the lipid droplets to the mitochondria. We propose a model for the action of LH in bovine small luteal cells that involves cAMP/PKA-dependent activation of HSL and trafficking of cholesterol from lipid droplets to mitochondria during progesterone synthesis (Figure 10).

Figure 10:

Proposed mechanism of action of Luteinizing hormone (LH) in bovine luteal cells. LH activates cAMP/PKA signaling. PKA phosphorylates HSL, which allows it to localize with lipid droplets and enhance its activity. As a result, HSL stimulates the hydrolysis of stores cholesteryl esters releasing cholesterol which is available for transport to the mitochondria by the constitutively expressed transporter steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (STAR). Cholesterol is converted to pregnenolone in the mitochondria, and then, to progesterone by microsomal enzymes in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

The current study focused on LH/PKA intracellular signaling events leading to luteal progesterone biosynthesis. Our findings reveal that PKA and HSL were required for trafficking of cholesterol from lipid droplets to mitochondria for LH-induced progesterone production. Our findings add to the understanding of the important role of HSL and lipid droplets in luteal steroidogenesis. Understanding the factors that contribute to the development, composition and maintenance of luteal lipid droplets may provide therapeutic insights into steroidogenesis and early pregnancy loss and fertility.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) mRNA transcripts and protein are expressed in luteal cells

LH/PKA signaling induces phosphorylation of HSL

HSL is required for LH-induced progesterone synthesis

LH stimulates translocation of HSL to lipid droplets

LH stimulates PKA/HSL-dependent trafficking of cholesterol from lipid droplets to mitochondria

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Janice Taylor and James Talaska at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Advanced Microscopy Core Facility for their assistance with microscopy. The use of microscope was supported by Center for Cellular Signaling CoBRE-P30GM106397 from the National Health Institutes. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Veterans Affairs Nebraska Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, NE.

This project was supported by NIH grants R01 HD087402 and R01HD092263 to JSD, ASC and JRW; USDA NIFA Grants 2017-67015-26450 to JSD and ASC, 2014-67011-22280 to HAT, and 2018-08068 to MRP; the Department of Veterans Affairs I01 BX004272 to JSD; the Olson Center for Women’s Health; and the use of microscope was supported by Center for Cellular Signaling CoBRE- P30GM106397 National Health Institutes.

Abbreviations

- Ad

adenovirus

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- CE

cholesteryl ester

- CL

corpus luteum

- CYP11A1

cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme, mitochondrial

- DAG

diacylglcerol

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FFA

Free Fatty Acid

- FSK

forskolin

- GC

granulosa cell

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- HPTLC

High Performance Thin Layer Chromatography

- HSD3B

3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/Delta 5→4 isomerase type 1

- HSL (LIPE)

hormone-sensitive lipase

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- LD

lipid droplet

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- LH

luteinizing hormone

- LHCGR

luteinizing hormone receptor

- LLC

large luteal cell

- PKA

Protein Kinase A

- PKI

the endogenous inhibitor of PKA

- PLIN

perilipin

- PMA

Phorbol-12-Myristate-13-acetate

- PNS

post-nuclear supernatant

- PNS-LD

post-nuclear supernatant depleted of lipid droplet

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SLC

small luteal cell

- STAR

steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

- TAG

triacylglycerol

- TC

theca cell

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Daya S, Ward S, Burrows E J. A. j. o. o., and gynecology. (1988) Progesterone profiles in luteal phase defect cycles and outcome of progesterone treatment in patients with recurrent spontaneous abortion. 158, 225–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rueda BR, Hendry IR, Hendry WJ III, Stormshak F, Slayden O, and Davis JS (2000) Decreased progesterone levels and progesterone receptor antagonists promote apoptotic cell death in bovine luteal cells. Biology of reproduction 62, 269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holesh JE, and Lord M (2019) Physiology, ovulation In StatPearls [Internet], StatPearls Publishing; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Shea JD, Rodgers RJ, and D’Occhio MJ (1989) Cellular composition of the cyclic corpus luteum of the cow. J Reprod Fertil 85, 483–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansel W, Alila HW, Dowd JP, and Milvae RA (1991) Differential origin and control mechanisms in small and large bovine luteal cells. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 43, 77–89 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiltbank M, Salih S, Atli M, Luo W, Bormann C, Ottobre J, Vezina C, Mehta V, Diaz F, and Tsai S (2012) Comparison of endocrine and cellular mechanisms regulating the corpus luteum of primates and ruminants. Animal reproduction/Colegio Brasileiro de Reproducao Animal 9, 242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsh J, and JM M (1975) The role of cyclic AMP in gonadal function. [PubMed]

- 8.Roy L, McDonald CA, Jiang C, Maroni D, Zeleznik AJ, Wyatt TA, Hou X, and Davis JS (2009) Convergence of 3′, 5′-cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate/protein kinase A and glycogen synthase kinase-3β/β-catenin signaling in corpus luteum progesterone synthesis. Endocrinology 150, 5036–5045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis J, Weakland L, Farese R, and West L (1987) Luteinizing hormone increases inositol trisphosphate and cytosolic free Ca2+ in isolated bovine luteal cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 262, 8515–8521 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiltbank M, Diskin M, and Niswender G (1991) Differential actions of second messenger systems in the corpus luteum. Journal of reproduction and fertility. Supplement 43, 65–75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seifart K, and Hansel W (1965) Bioassay of pituitary luteinizing hormone by an in vitro system In FEDERATION PROCEEDINGS Vol. 24 pp. 320-&, FEDERATION AMER SOC EXP BIOL; 9650 ROCKVILLE PIKE, BETHESDA, MD 20814-3998 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohen P, Castro O, Palomino A, Muñoz A, Christenson LK, Sierralta W, Carvallo P, Strauss JF III, Devoto L J. T. J. o. C. E., and Metabolism. (2003) The steroidogenic response and corpus luteum expression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein after human chorionic gonadotropin administration at different times in the human luteal phase. 88, 3421–3430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller WL (2017) Disorders in the initial steps of steroid hormone synthesis. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 165, 18–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manna PR, Dyson MT, and Stocco DM (2009) Regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene expression: present and future perspectives. Molecular human reproduction 15, 321–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rapoport R, Sklan D, Wolfenson D, Shaham-Albalancy A, and Hanukoglu I (1998) Antioxidant capacity is correlated with steroidogenic status of the corpus luteum during the bovine estrous cycle. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects 1380, 133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu J, Zhang Z, Shen W-J, and Azhar S (2010) Cellular cholesterol delivery, intracellular processing and utilization for biosynthesis of steroid hormones. Nutrition & metabolism 7, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stocco DM (1997) A StAR search: implications in controlling steroidogenesis. Biology of reproduction 56, 328–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller WL (1995) Mitochondrial specificity of the early steps in steroidogenesis. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 55, 607–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niswender GD (2002) Molecular control of luteal secretion of progesterone. Reproduction 123, 333–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christenson LK, and Devoto L (2003) Cholesterol transport and steroidogenesis by the corpus luteum. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 1, 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grummer R, and Carroll D (1988) A review of lipoprotein cholesterol metabolism: importance to ovarian function. Journal of Animal Science 66, 3160–3173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talbott H, and Davis JS (2017) Lipid droplets and metabolic pathways regulate steroidogenesis in the corpus luteum In The life cycle of the corpus luteum pp. 57–78, Springer [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khanthusaeng V, Thammasiri J, Bass CS, Navanukraw C, Borowicz P, Redmer DA, and Grazul-Bilska AT J. A. h. (2016) Lipid droplets in cultured luteal cells in non-pregnant sheep fed different planes of nutrition. 118, 553–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talbott HA, Plewes MR, Krause C, Hou X, Zhang P, Rizzo WB, Wood JR, Cupp AS, and Davis JS (2020) Composition of the Lipid Droplets of the Bovine Corpus Luteum. bioRxiv [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schweiger M, Schreiber R, Haemmerle G, Lass A, Fledelius C, Jacobsen P, Tornqvist H, Zechner R, and Zimmermann R (2006) Adipose triglyceride lipase and hormone-sensitive lipase are the major enzymes in adipose tissue triacylglycerol catabolism. Journal of Biological Chemistry 281, 40236–40241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaughan M, Berger JE, and Steinberg D (1964) Hormone-sensitive lipase and monoglyceride lipase activities in adipose tissue. Journal of Biological Chemistry 239, 401–409 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Small CA, Goodacre JA, and Yeaman SJ (1989) Hormone‐sensitive lipase is responsible for the neutral cholesterol ester hydrolase activity in macrophages. FEBS letters 247, 205–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Escary J-L, Choy HA, Reue K, and Schotz MC (1998) Hormone-sensitive lipase overexpression increases cholesteryl ester hydrolysis in macrophage foam cells. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 18, 991–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.COOK KG, YEAMAN SJ, STRALFORS P, FREDRIKSON G, and BELFRAGE P (1982) Direct evidence that cholesterol ester hydrolase from adrenal cortex is the same enzyme as hormone‐sensitive lipase from adipose tissue. European journal of biochemistry 125, 245–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraemer FB, Shen W-J, Harada K, Patel S, Osuga J. i., Ishibashi S, and Azhar S (2004) Hormone-sensitive lipase is required for high-density lipoprotein cholesteryl ester-supported adrenal steroidogenesis. Molecular endocrinology 18, 549–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekiya M, Osuga J. i., Yahagi N, Okazaki H, Tamura Y, Igarashi M, Takase S, Harada K, Okazaki S, and Iizuka Y (2008) Hormone-sensitive lipase is involved in hepatic cholesteryl ester hydrolysis. Journal of lipid research 49, 1829–1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osuga J. i., Ishibashi S, Oka T, Yagyu H, Tozawa R, Fujimoto A, Shionoiri F, Yahagi N, Kraemer FB, and Tsutsumi O (2000) Targeted disruption of hormone-sensitive lipase results in male sterility and adipocyte hypertrophy, but not in obesity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97, 787–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holst LS, Hoffmann AM, Mulder H, Sundler F, Holm C, Bergh A, and Fredrikson G (1994) Localization of hormone‐sensitive lipase to rat Sertoli cells and its expression in developing and degenerating testes. FEBS letters 355, 125–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lobo MV, Huerta L, Arenas MI, Busto R, Lasunción MA, and Martín-Hidalgo A (2009) Hormone-sensitive lipase expression and IHC localization in the rat ovary, oviduct, and uterus. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 57, 51–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraemer FB, and Shen W-J (2006) Hormone-sensitive lipase knockouts. Nutrition & metabolism 3, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anthonsen MW, Rönnstrand L, Wernstedt C, Degerman E, and Holm C (1998) Identification of novel phosphorylation sites in hormone-sensitive lipase that are phosphorylated in response to isoproterenol and govern activation properties in vitro. Journal of Biological Chemistry 273, 215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watt MJ, Holmes AG, Pinnamaneni SK, Garnham AP, Steinberg GR, Kemp BE, and Febbraio MA (2006) Regulation of HSL serine phosphorylation in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 290, E500–E508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraemer FB (2007) Adrenal cholesterol utilization. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 265, 42–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strålfors P, Björgell P, and Belfrage P (1984) Hormonal regulation of hormone-sensitive lipase in intact adipocytes: identification of phosphorylated sites and effects on the phosphorylation by lipolytic hormones and insulin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 81, 3317–3321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garton AJ, Campbell DG, Cohen P, and Yeaman SJ (1988) Primary structure of the site on bovine hormone-sensitive lipase phosphorylated by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. FEBS letters 229, 68–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manna PR, Cohen-Tannoudji J, Counis R, Garner CW, Huhtaniemi I, Kraemer FB, and Stocco DM J. J. o. B. C. (2013) Mechanisms of Action of Hormone-sensitive Lipase in Mouse Leydig Cells ITS ROLE IN THE REGULATION OF THE STEROIDOGENIC ACUTE REGULATORY PROTEIN. 288, 8505–8518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen W-J, Patel S, Natu V, Hong R, Wang J, Azhar S, and Kraemer FB J. J. o. B. C. (2003) Interaction of Hormone-sensitive Lipase with Steroidogeneic Acute Regulatory Protein FACILITATION OF CHOLESTEROL TRANSFER IN ADRENAL. 278, 43870–43876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen W-J, Azhar S, and Kraemer FB J. E. c. r. (2016) Lipid droplets and steroidogenic cells. 340, 209–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mao D, Hou X, Talbott H, Cushman R, Cupp A, and Davis JS (2013) ATF3 expression in the corpus luteum: possible role in luteal regression. Molecular Endocrinology 27, 2066–2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romereim SM, Summers AF, Pohlmeier WE, Zhang P, Hou X, Talbott HA, Cushman RA, Wood JR, Davis JS, and Cupp AS (2017) Transcriptomes of bovine ovarian follicular and luteal cells. Data in brief 10, 335–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romereim SM, Summers AF, Pohlmeier WE, Zhang P, Hou X, Talbott HA, Cushman RA, Wood JR, Davis JS, and Cupp AS (2017) Gene expression profiling of bovine ovarian follicular and luteal cells provides insight into cellular identities and functions. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 439, 379–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li D, Yin X, Zmuda EJ, Wolford CC, Dong X, White MF, and Hai T (2008) The repression of IRS2 gene by ATF3, a stress-inducible gene, contributes to pancreatic β-cell apoptosis. Diabetes 57, 635–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taurin S, Sandbo N, Yau DM, Sethakorn N, and Dulin NO J. A. J. o. P.-C. P. (2008) Phosphorylation of β-catenin by PKA promotes ATP-induced proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. 294, C1169–C1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H, Hu L, Dalen K, Dorward H, Marcinkiewicz A, Russell D, Gong D, Londos C, Yamaguchi T, and Holm C J. J. o. B. C. (2009) Activation of hormone-sensitive lipase requires two steps, protein phosphorylation and binding to the PAT-1 domain of lipid droplet coat proteins. 284, 32116–32125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brasaemle DL, and Wolins NE J. C. p. i. c. b. (2016) Isolation of lipid droplets from cells by density gradient centrifugation. 72, 3.15. 11–13.15. 13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ding Y, Wu Y, Zeng R, and Liao K J. A. B. B. S. (2012) Proteomic profiling of lipid droplet-associated proteins in primary adipocytes of normal and obese mouse. 44, 394–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Plewes M, Burns P, Graham P, Hyslop R, and Barisas B (2017) Effect of fish oil on lateral mobility of prostaglandin F 2α (FP) receptors and spatial distribution of lipid microdomains in bovine luteal cell plasma membrane in vitro. Domestic Animal Endocrinology 58, 39–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Plewes MR, Burns PD, Graham PE, Bruemmer JE, Engle TE, and Barisas BG (2017) Effect of fish meal supplementation on spatial distribution of lipid microdomains and on the lateral mobility of membrane-bound prostaglandin F2α receptors in bovine corpora lutea. Domestic Animal Endocrinology 60, 9–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plewes MR, Burns PD, Hyslop RM, and Barisas BG (2017) Influence of omega-3 fatty acids on bovine luteal cell plasma membrane dynamics. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 1859, 2413–2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plewes M, and Burns P (2018) Effect of fish oil on agonist-induced receptor internalization of the PG F2α receptor and cell signaling in bovine luteal cells in vitro. Domestic animal endocrinology 63, 38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holm C (2003) Molecular mechanisms regulating hormone-sensitive lipase and lipolysis. Portland Press Limited; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Minkkilä A, Savinainen JR, Käsnänen H, Xhaard H, Nevalainen T, Laitinen JT, Poso A, Leppänen J, and Saario SM (2009) Screening of Various Hormone‐Sensitive Lipase Inhibitors as Endocannabinoid‐Hydrolyzing Enzyme Inhibitors. ChemMedChem 4, 1253–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]