Abstract

Emergency department (ED) providers serve as the primary point-of-contact for many survivors of sexual assault, but are often untrained on their unique treatment needs. Sexual assault nurse examiners (SANE) are therefore an important resource for training other ED providers. The objective of this project was to create a SANE-led educational intervention addressing this training gap. We achieved this objective by 1) conducting a needs-assessment of ED providers’ self-reported knowledge of and comfort with sexual assault patient care at an urban academic adult ED, and 2) using these results to create and implement a SANE-led educational intervention to improve emergency medicine (EM) residents’ ability to provide sexual assault patient care. From the needs-assessment survey, ED providers reported confidence in medical management but not in providing trauma-informed care, conducting forensic exams, or understanding hospital policies or state laws. Less than half of respondents felt confident in their ability to avoid re-traumatizing sexual assault patients and only 29% felt comfortable conducting a forensic exam. Based on these results, a SANE-led educational intervention was developed for EM residents, consisting of a didactic lecture, two standardized patient cases, and a forensic pelvic exam simulation. Pre- and post- intervention surveys demonstrated an increase in respondents’ ability to avoid re-traumatizing patients, comfort with conducting forensic exams, and understanding of laws and policies. These results demonstrate the value of an inter-professional collaboration between physicians and SANEs to train ED providers on sexual assault patient care.

Keywords: sexual assault, rape, sexual assault nurse examiner, forensic exam, medical evidence kit, trauma-informed care, re-traumatization

Introduction

Sexual assault is a pervasive human rights issue across the United States. Current estimates suggest that 1 in 5 women and 1 in 14 men will experience a completed or attempted rape in their lifetime (Smith et al., 2018). In Illinois, 5,309 cases of rape were reported to the Illinois Police Uniform Crime Reporting Program in 2017 (Crime in Illinois 2017, 2017). Sequelae of this violence include serious and long-lasting mental and physical health conditions, making sexual assault a critical medical issue (Pegram & Abbey, 2016; Peterson et al., 2017). Indeed, the emergency department (ED) serves as one of the first points-of-contact for many sexual assault survivors, seeing over 65,000 survivors per year (CDC WISQARS, 2017; Filmalter et al., 2018).

To meet the unique needs of sexual assault patients, EDs across the country have developed sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) programs. SANEs are specifically trained in taking sexual assault histories, conducting forensic exams, and providing compassionate care to survivors of sexual assault using a trauma-informed approach (Office for Victims of Crime, 2016). This approach involves realizing how trauma can affect individuals and groups, recognizing signs of trauma, responding through language and behavior that is sensitive to this trauma, and resisting re-traumatization (Huang et al., 2014). Studies have shown that this specialized training makes survivors feel more cared for and humanized during their hospital encounters with SANEs than during prior experiences with non-SANE ED providers (Fehler-Cabral et al., 2011). Past studies have also shown that EDs with SANE programs are more likely to provide STI prophylaxis, emergency contraception, comprehensive medical services, and proper completion of forensic exams (Cameron & Helitzer, 2003; Schmitt et al., 2017).

While SANE programs are extremely effective in addressing the specific needs of sexual assault survivors, SANEs are not always available when needed (Delgadillo, 2017). For instance, as of April 2018, there were only 32 certified SANEs in Illinois, compared to over 10,000 ED nurses (Bowen, 2018; Delaney et al., 2019). In these situations, other ED providers are tasked with providing medical treatment and conducting forensic evidence collection (Campbell et al., 2014). Unfortunately, insufficient training of non-SANE providers on the unique needs of these patients can result in poor outcomes via victim-blaming language, substandard provision of medical care, and inadequate forensic evidence collection (Maier, 2012). For example, a study that surveyed EDs across Illinois showed that only 59.6% always provided emergency contraceptives and only 28% always provided HIV prophylaxis (Patel et al., 2008). Physicians themselves are aware of these educational gaps, and report feeling uncomfortable and unprepared to care for sexual assault patients (Amin et al., 2017). Thought should be given, therefore, to the development of training programs for healthcare professionals to ensure that they are prepared to meet the unique needs of survivors. Given the expertise and extensive experience of SANEs, they are particularly suited to provide training to their fellow ED providers (Auten et al., 2015; McLaughlin et al., 2007).

The objective of this project, therefore, was to create an educational intervention at an Illinois urban academic adult ED that would target the self-perceived educational gaps of ED providers, via a collaboration between physicians and SANEs. First, a needs-assessment was conducted of ED providers’ self-perceived comfort with providing all aspects of care to survivors of sexual assault, as well as their attitudes and beliefs about sexual assault, and perceived barriers to care. Second, the results of this needs-assessment were used to develop and evaluate a SANE-led educational intervention for emergency medicine (EM) residents on sexual assault patient care, consisting of a didactic lecture, two standardized patient (SP) cases, and a forensic pelvic exam simulation.

Methods

Development of the Needs-Assessment

The first component of this project was a cross-sectional needs-assessment conducted at an Illinois urban academic adult ED, with a population consisting of non-SANE nurses, EM residents, and EM attending physicians. The needs-assessment evaluated the aforementioned providers’ self-perceived attitudes and beliefs regarding sexual assault, comfort with providing sexual assault medical care, comfort with avoiding re-traumatizing survivors, comfort with conducting a forensic exam, knowledge of hospital/state sexual assault laws and policies, and barriers to providing care. A survey was developed that consisted of 23 Likert-type scale questions answered on a 5-point scale from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree,” and two short-answer questions (Supplemental Digital Content 1). Content validity was established by an interactive process of review by two EM attending physicians with expertise in educational content, the Illinois SANE coordinator, and two members of the YWCA Metropolitan Chicago’s Sexual Violence Support Services.

Distribution of the Needs-Assessment

The needs-assessment survey was distributed electronically via email to all ED providers, in paper form to EM residents at their weekly conference, and to nurses at their daily meetings, between June and October of 2017. Responses to the emailed survey were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools (Harris et al., 2009). Responses to the paper survey were manually entered into REDCap by the investigators. Survey completion was voluntary and anonymous.

Statistical Analysis of the Needs-Assessment

Likert-type scale questions were analyzed with histograms comparing the distributions of responses. Between-group comparisons were made by gender and experience working with sexual assault survivors. The statistical significance of the differences between the group distributions was determined using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. Statistical significance was set a priori as a two-tailed p-value of < 0.05. All data cleaning and analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, 2017).

Development of the Educational Intervention

Based on the training gaps identified in the aforementioned needs-assessment survey, an educational intervention was developed through a collaboration between the Illinois SANE Coordinator, a family medicine physician specializing in intimate partner violence, two EM physicians with expertise in educational content, and the Director of the YWCA Metropolitan Chicago’s Advocacy and Crisis Intervention Services. The intervention consisted of a two-hour didactic lecture, two 20-minute sexual assault SP cases, and a 40-minute forensic pelvic exam simulation.

The didactic lecture included 1) an overview of the health impacts of sexual assault on patients, 2) a discussion of re-traumatization in the healthcare setting, 3) an overview of Illinois laws governing forensic exam consent, 4) instructions on conducting patient histories for sexual assault cases, 5) best practices for the head-to-toe assessment and evidence collection including an overview of the documentation involved, 6) detailed instructions on performing proper ano-genital assessments with specialized examination techniques, and 7) best practices for language to avoid re-traumatization of survivors. Content for this didactic was based on the results of the needs-assessment, standard curricula from 40-hour sexual assault advocacy certification trainings, standard curricula from SANE trainings, and the American College of Emergency Physicians guidelines for the treatment of sexual assault patients.

The SP cases were developed for this intervention by the primary investigators and were based off of standard scenarios used in SANE trainings. Each case simulated a new patient who had presented to the ED after sexual assault. Participants were given 15 minutes to take a focused history; SPs then spent five minutes giving feedback to the participant. The first case involved a patient who had been raped by an acquaintance, and the second involved a patient who worked as a sex worker and was raped by a client. Both cases were reviewed by the Illinois SANE coordinator, the Director of the YWCA Metropolitan Chicago’s Advocacy and Crisis Intervention Services, and the Associate Director of an Illinois medical school’s Standardized Patient and Clinical Performance Center. The SPs were certified YWCA sexual assault patient advocates with at least one year of experience working in EDs with survivors of sexual assault. The SPs were trained for this event by the Illinois SANE coordinator to both act as the patients in the cases and to provide feedback to the participants on their history taking and language skills.

Content for the forensic pelvic exam simulation was developed by the Illinois SANE coordinator and was derived from standard SANE trainings. The simulation consisted of a 20-minute demonstration of proper exam techniques in a step-by-step fashion, focusing on the differences between a medical pelvic exam and a forensic pelvic exam. Evidence collection strategies were highlighted. Participants were then given 20 minutes to practice the steps themselves, with one-on-one feedback from the Illinois SANE coordinator. Pelvic mannikins were used for both demonstration and practice purposes; each participant had their own mannikin for practice.

Implementation of the Educational Intervention

The educational intervention was conducted on May 9, 2019 during the monthly scheduled EM resident simulation day. The two-hour lecture component was delivered by the Illinois SANE coordinator to all participating EM residents. Next, the residents rotated between the SP cases and the forensic pelvic exam simulation. To assess the efficacy of the intervention, residents were given paper pre- and post-surveys assessing their self-perceived knowledge of and comfort with sexual assault patient care. These surveys were developed by modifying the original needs-assessment survey to target the objectives of the educational intervention; they each consisted of 11 Likert-type scale questions answered on a scale of “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree,” as well as two short answer questions on the pre-survey and one short answer question on the post-survey. (Supplemental Digital Content 2). Paper surveys were confidential and were transcribed to an Excel spreadsheet by the investigators, and then converted into a Stata dataset.

Statistical Analysis of the Educational Intervention

Likert-type scale questions were analyzed with histograms comparing the distributions of responses in the pre-survey to the distributions of responses in the post-survey. The statistical significance of the differences between the distributions was determined using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. Statistical significance was set a priori as a two-tailed p-value of < 0.05. All data cleaning and analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, 2017).

This project was granted exemption status by the University of Chicago IRB: IRB 17–0482, IRB 18–0073, IRB 18–0049.

Results

Needs-Assessment

Demographics of respondents.

The needs-assessment survey was distributed via email on seven occurrences to 192 individual email accounts, and via paper at one EM resident conference and six nurse meetings. Ninety-five ED staff members completed the survey, including 20 attending physicians (response rate of 71%), 34 residents (response rate of 53%), and 41 non-SANE nurses (response rate of 41%). Fifty-five percent of respondents were female, and 33% were 36 years of age or older (Table 1). Forty-seven percent of respondents had more than one year of experience working with survivors of sexual assault.

Table 1:

Demographics of respondents to the emergency department needs-assessment survey

| Attendings (n = 20) | EM Residents (n = 34) | Nurses (n = 41) | Total (n = 95) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response rate | 71% | 53% | 41% | 59% |

| Age | ||||

| 18–35 (%) | 5 (25%) | 34 (100%) | 25 (61%) | 64 (67%) |

| 36 + (%) | 15 (75%) | 0 (0%) | 16 (39%) | 31 (33%) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (%) | 14 (70%) | 17 (50%) | 10 (34%) | 41 (43%) |

| Female (%) | 6 (30%) | 16 (47%) | 30 (73%) | 52 (55%) |

| Experience with survivors of SA | ||||

| < 1 year (%) | 8 (40%) | 19 (56%) | 22 (54%) | 49 (52%) |

| 1+ year (%) | 12 (60%) | 15 (44%) | 18 (46%) | 45 (47%) |

EM = emergency medicine; SA = sexual assault

Note: Percentages might not add to 100% due to missing responses.

Provider self-reported comfort with sexual assault patient care and forensic exam provision.

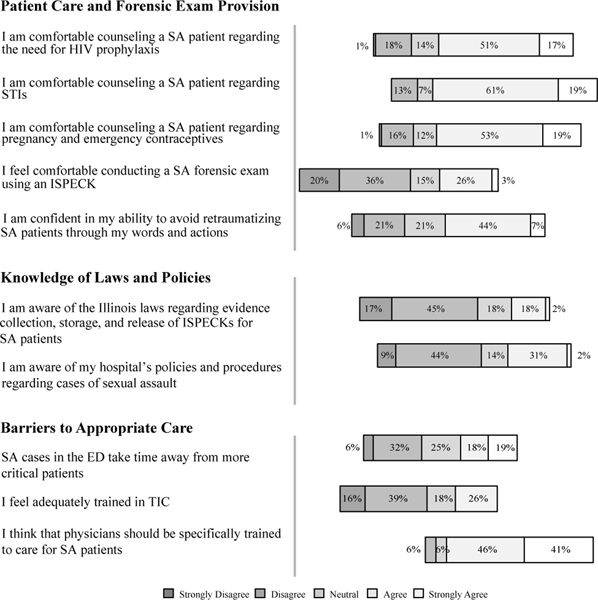

Respondents felt comfortable with many aspects of the medical management of survivors. For instance, most providers agreed or strongly agreed that they felt comfortable counseling patients on: 1) the need for HIV prophylaxis (68%), 2) sexually transmitted infections (80%), and 3) pregnancy and emergency contraceptives (72%) (Figure 1). However, only 29% of respondents indicated that they were comfortable conducting a sexual assault forensic exam, and only 51% felt confident in their ability to avoid re-traumatizing sexual assault patients through their words and actions.

Figure 1:

Distribution of responses to select Likert-type scale questions from the emergency department needs-assessment survey; n = 95

ED = emergency department; IPSECK = Illinois State Police Evidence Collection Kit; SA = sexual assault; STI = sexually transmitted infection; TIC = trauma-informed care

The needs-assessment survey was distributed to ED attending physicians, residents, and nurses.

Provider self-reported knowledge of sexual assault laws and policies.

Respondents also reported a lack of familiarity with relevant state laws and hospital policies (Figure 1). Only 20% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they were aware of Illinois laws regarding evidence collection for the forensic exam. Furthermore, only 33% agreed or strongly agreed that they were aware of their own hospital’s policies and procedures regarding cases of sexual assault.

Provider self-reported barriers to sexual assault patient care.

The majority of respondents (71%) felt that time was a significant barrier to their ability to conduct a forensic exam in a thorough and sensitive manner. Thirty-seven percent believed that sexual assault patients take time away from “more critical patients” (Figure 1). Male respondents were more likely to agree or strongly agree with this statement than female respondents (56% vs. 21% respectively, p < 0.01) (Supplemental Digital Content 3). In addition, only 26% agreed or strongly agreed that they felt adequately trained in trauma-informed care (Figure 1). The vast majority of respondents, however indicated a desire for training, with 87% agreeing that physicians should be specifically trained to care for sexual assault patients.

Responses to short answer questions.

Even though formal content analysis was not performed, a read-through of the responses revealed that 34 of the 78 respondents who answered the short answer questions expressed that time was a major systemic barrier to treating sexual assault patients in the ED. Furthermore, 38 respondents mentioned that lack of education and training was a barrier to care, and seven mentioned a need for more SANEs to be on staff. Lastly, six male respondents (15% of all male respondents) reported that being male felt like a barrier to providing treatment to this patient population.

Stratification of respondents by years of experience working with survivors.

While respondents with more than one year of experience working with survivors were more likely to know Illinois laws and hospital policies, understand how to take a sexual assault patient history, conduct a forensic exam, and feel confident in their ability to avoid re-traumatizing patients, there was still an overall lack of comfort in these areas (Table 2). For example, only 18% of experienced providers agreed/strongly agreed that they knew the requirements of Illinois’ Sexual Assault Survivors Emergency Treatment Act (SASETA) (compared to 6% of the less-experienced providers, p < 0.05), only 67% felt confident not re-traumatizing patients (compared to 39%, p < 0.05), and only 44% felt comfortable conducting a sexual assault forensic exam (compared to 16%, p < 0.001). Both experienced and less-experienced respondents agreed or strongly agreed that physicians should be specifically trained to care for sexual assault patients – 91% versus 86% (p = 0.35).

Table 2:

Percentage of respondents to the emergency department needs-assessment survey who agreed or strongly agreed with the following statements, based on amount of experience working with survivors of sexual assault

| 1 or more years of experience (n=45) | Less than 1 year of experience (n=49) | Distribution p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I know the requirements of the SASETA | 18% | 6% | < 0.05 |

| I am aware of my hospitals policies and procedures regarding cases of SA | 51% | 14% | <0.001 |

| I am aware of what elements of the history to obtain from SA patients | 76% | 43% | <0.001 |

| I am confident in my ability to avoid retraumatizing SA patients through my words and actions | 67% | 39% | <0.05 |

| I feel comfortable counseling patients about the SA forensic exam | 56% | 22% | <0.001 |

| I feel comfortable conducting a SA forensic exam using an ISPECK | 44% | 16% | <0.001 |

| I feel adequately trained in TIC | 61% | 29% | <0.001 |

| Part of the physician’s role is to determine whether SA occurred | 13% | 41% | <0.001 |

| When drugs or alcohol are involved, I think there is a grey area in classifying cases of SA | 4% | 18% | <0.05 |

| I always think patients who say they have been sexually assaulted are telling the truth | 62% | 37% | <0.05 |

| I think that physicians should be specifically trained to care for SA patients | 91% | 86% | 0.35 |

IPSECK = Illinois State Police Evidence Collection Kit; SA = sexual assault; SASETA = Sexual Assault Survivor Treatment Act; TIC = trauma-informed care

The statistical significance of the differences between the group distributions was determined using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. Statistical significance was set a priori as a two-tailed p-value <0.05.

Educational Intervention

Demographics of respondents.

Twenty EM residents attended the educational intervention on May 9, 2019. Eighteen attendees completed the pre-survey and 15 completed the post-survey. Fifty percent of the attendees were female, and all were between the ages of 18–35. Thirty-five percent were first year residents, 24% were second-year residents, and 41% were third year residents. Forty-one percent of attendees had seen fewer than five sexual assault cases in the ED.

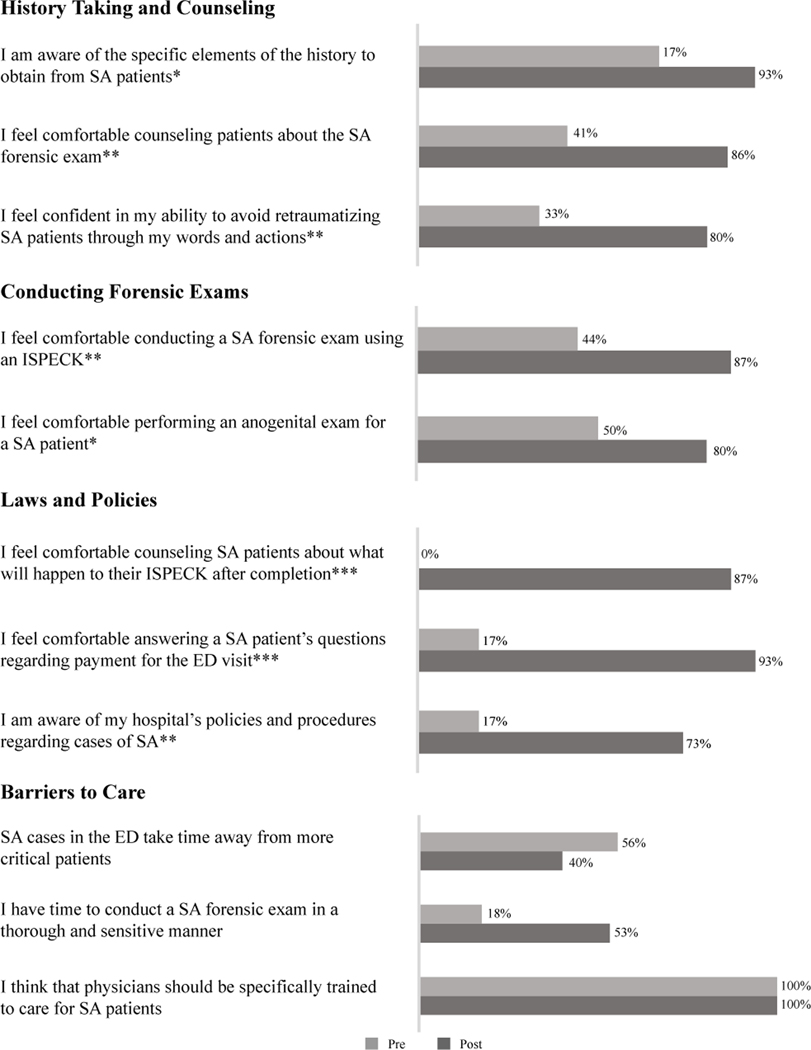

Provider self-reported comfort with history-taking and counseling.

Before the intervention, 67% of residents agreed or strongly agreed that they were aware of the specific elements of the history to obtain from sexual assault patients, compared to 93% after the intervention (p < 0.05) (Figure 2). In addition, an increase in the proportion of residents who agreed or strongly agreed that they felt comfortable counseling patients about the forensic exam also occurred after the intervention, from 41% to 86% (p < 0.01). Attendees were also more likely to agree or strongly agree that they felt confident in their ability to avoid re-traumatizing sexual assault patients through their words and actions, increasing from 33% before the intervention to 80% afterwards (p < 0.01).

Figure 2:

Percentage of respondents who agreed or strongly agreed to the following Likert-type scale questions from the emergency medicine resident educational intervention pre- and post- surveys; n = 18 for the pre-survey and n = 15 for the post-survey

ED = emergency department; IPSECK = Illinois State Police Evidence Collection Kit; SA = sexual assault

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

The statistical significance of the differences between the pre- and post- survey distributions was determined using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. Statistical significance was set a priori as a two-tailed p-value of < 0.05.

Provider self-reported comfort with conducting forensic exams.

After the intervention, attendees reported a change in their comfort with performing the forensic exam. For example, the percentage of attendees who agreed or strongly agreed that they felt comfortable conducting an Illinois State Police Evidence Collection Kit (ISPECK) increased from 44% before the intervention to 87% afterwards (p < 0.01) (Figure 2). Attendees were also more likely to agree or strongly agree that they felt comfortable performing an ano-genital exam on sexual assault patients after the intervention, with an increase from 50% to 80% (p < 0.05).

Provider self-reported comfort with laws and policies.

While before the intervention none of the attendees agreed or strongly agreed that they felt comfortable counseling patients about what would happen to their ISPECK after completion, 87% felt comfortable doing so after the intervention (p < 0.001) (Figure 2). Attendees also expressed an increase in their comfort with answering patient questions regarding payment for the ED visit, from 17% agreeing or strongly agreeing to this statement before the intervention to 93% afterwards (p < 0.001). Finally, while only 17% of attendees agreed or strongly agreed that they were aware of their hospital’s policies and procedures regarding sexual assault before the intervention, 73% did so after the intervention (p < 0.01).

Provider self-reported barriers to sexual assault patient care.

Before the intervention, 56% of residents agreed or strongly agreed that sexual assault cases in the ED take time away from more critical patients. Though this percentage decreased to 40% after the intervention, the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 2). Similarly, the percentage agreeing or strongly agreeing that they have the time to conduct a forensic exam in a thorough and sensitive manner increased from 18% to 53%, but without a statistically significant difference. Both before and after the intervention, though, 100% of the attendees agreed or strongly agreed that physicians should be specifically trained to care for sexual assault patients.

Responses to short answer questions.

Though formal content analysis was not performed, 11 of the 15 respondents who answered the short-answer questions mentioned time constraints as one of the main barriers to caring for survivors of sexual assault. For example, one respondent noted that “having an entire ED to run does not allow you to spend the time with this one patient.” In addition, nine mentioned a lack of training and education as a barrier, with one respondent writing, “I feel like I haven’t been formally taught how to treat a sexual assault patient, ever.” Three respondents specifically noted the ISPECK as a particular gap in knowledge with another three respondents specifically mentioning laws and policies. For example, one respondent wrote that they did not know “how to properly conduct [a] SANE exam from start to finish,” and another was unsure of “the laws in Illinois.”

Short answer responses to the post-survey also did not undergo formal content analysis, but nine of the 11 attendees who provided short-answer responses wrote that the educational intervention was very helpful to their ability to care for survivors. Two specifically discussed the benefits of participating in the SP cases. For example, one respondent noted that they felt “more comfortable interviewing people after this intervention.” In addition, five commented on the benefit of the forensic pelvic exam simulation, with one respondent mentioning that it was “very helpful to realize [the] steps of the exam [they] were rushing through and how to perform [the] steps correctly.”

Discussion

The ED serves as one of the primary sources of care for sexual assault survivors, a population of patients that requires complex, sensitive care. SANEs are specifically trained to care for these patients, but due to scarcity are not always available when needed (Delgadillo, 2017). Despite the frequency with which non-SANE ED providers encounter sexual assault survivors, most are not trained on survivors’ specific needs, leading to inadequate or re-traumatizing care (Maier, 2012). To address these issues, we conducted a needs-assessment of providers at an Illinois urban academic ED and used the results to develop a SANE-led educational intervention. With this approach, we were able to first collect data regarding ED providers’ self-perceived training gaps and then target the educational intervention directly to their needs.

The needs-assessment demonstrated that providers at this ED were uncomfortable with many aspects of sexual assault patient care, such as avoiding re-traumatization and conducting forensic exams. As SANEs are not always available when a sexual assault history and forensic exam must be conducted, it is important that ED providers feel capable of doing so themselves in a trauma-informed manner. Therefore, our EM resident educational intervention emphasized the specific steps of the forensic examination, specific elements of the history to elicit, and methods to avoid re-traumatizing patients. In addition to the lecture addressing these topics, the residents had a chance to practice these skills by completing two SP cases and a forensic pelvic exam simulation. This intervention led to an increase in resident comfort with avoiding re-traumatization, counseling patients on the forensic exam, and conducting the forensic exam.

The needs-assessment also suggested that ED providers felt unaware of both the statewide laws that dictate how sexual assault patients should be treated, and their own ED’s specific policies on sexual assault patient care. We aimed to address these gaps in our educational intervention, leading to an increase in resident understanding of ISPECK regulations, laws surrounding ED payment, and specific hospital policies. This improvement is encouraging, because knowledge of state laws and hospital policies allows for physicians and nurses to better counsel survivors on the legal and medical aspects of their care.

The majority of the needs-assessment respondents reported that time is a significant barrier to providing care for sexual assault patients. Many respondents also indicated that sexual assault patients take time away from more “critical” patients; male respondents were more likely to agree to this statement than female respondents, suggesting a possible correlation between gender and stigmatization of sexual assault patients. While these issues cannot be fully addressed by an educational intervention, pre- and post-surveys did demonstrate an increase in the percentage of residents who felt that they have the time to conduct a sexual assault forensic exam and a decrease in those who felt sexual assault patients take time away from more “critical” patients. Hopefully, as providers become more comfortable with the steps involved in sexual assault patient care, they will also become more efficient and more able to care for these patients appropriately in a shorter amount of time.

The needs-assessment survey responses from ED providers who had more than one year of experience working with survivors of sexual assault demonstrated more self-perceived knowledge of sexual assault patient care than their counterparts, but less knowledge overall than would be desired in a health-care system fully prepared to address the complex needs of this vulnerable patient population. Since both experienced and less-experienced providers alike agreed that specifically training physicians in sexual assault patient care is important and necessary, this may suggest that ad-hoc experience does not fully replace formal training. Instead, providers of all experience-levels could likely benefit from increased education in this area.

Unfortunately, most ED providers have not undergone the extensive training completed by SANEs that is necessary to cover all aspects of sexual assault patient care. Properly learning the nuances of history taking, medical care, forensic examination, and trauma-informed care takes hours of dedicated education. Therefore, our work first and foremost highlights the need to train and hire more SANEs in Illinois. First, such a measure would address the time barrier described by so many of our survey respondents, since SANEs are able to provide all aspects of care to survivors and can fully focus on survivors. Second, while all providers should receive basic training on sexual assault patient care, nothing can truly replace the dedicated training SANEs receive. However, given that non-SANE ED providers are often still responsible for caring for survivors of sexual assault, they must receive a baseline level of training. ED providers, therefore, have a valuable resource in their SANE colleagues. This suggests yet another reason to increase the number of SANEs in Illinois – to serve as educational and training resources.

Our own intervention was strengthened by the collaboration between EM physicians, SANEs, and certified sexual assault patient advocates. Even though our educational intervention was a condensed version of the SANE and advocate curricula, we were able to leverage this inter-professional collaboration to significantly improve EM resident knowledge of and comfort with sexual assault patient care. Our educational intervention is particularly feasible and valuable within graduate medical education training programs. This intervention occurred during a regularly scheduled didactic session and demonstrated the efficacy of utilizing both traditional lecture and standardized patient cases/simulations in developing patient-centered communication skills, a necessary milestone for EM residents as mandated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (The Emergency Medicine Milestone Project, 2015).

This project is limited by its single-center status and the sample-selection bias that is inherent in the response rate. It is further limited by the small sample size of the educational intervention; therefore, the statistical testing should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

Our project demonstrated that providers at an Illinois urban academic adult ED reported significant gaps in their understanding of sexual assault patient care, including avoiding re-traumatization, conducting a forensic exam, and knowing relevant laws and policies. Assessing these educational gaps allowed us to create an interprofessional SANE-led educational intervention that targeted these providers’ specific needs, leading to an increase in their self-perceived knowledge of and comfort with sexual assault patient care. Since we have identified problems that are widespread throughout the country, we encourage other hospital systems to implement similar needs-assessments and educational interventions. Given the extensive expertise of SANEs on caring for sexual assault survivors, they are uniquely suited to help provide this training to their non-SANE colleagues. Therefore, our work highlights the need to expand the ranks of SANEs in Illinois and across the country to both meet the care needs of survivors and the educational needs of ED providers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements and Credits:

We thank the University of Chicago Emergency Department EM residents, SANE nurses, nurses, and attendings for participating in our surveys. We also thank the YWCA Metropolitan Chicago for reviewing our surveys and providing helpful feedback on both language and content. We would especially like to thank the YWCA sexual assault patient advocates for volunteering their time to serve as standardized patients for our training session. Finally, we would like to thank the Standardized Patient Program and Clinical Performance Center at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine for their guidance in this project.

Funding Information:

This study was supported by the University of Chicago Bucksbaum Institute Pilot Grant and the University of Chicago Biological Science Division Diversity Grant.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

AC, ND, RP, JR, JA, SO, and KC report no conflict of interest.

References

- Amin P, Buranosky R, & Chang J. (2017). Physicians’ Perceived Roles, as Well as Barriers, Toward Caring for Women Sex Assault Survivors. Women’s Health Issues, 27(1), 43–49. 10.1016/j.whi.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auten J, Ross E, French M, Li I, Robinson L, Brown N, King K, & Tanen D. (2015). Low-Fidelity Hybrid Sexual Assault Simulation Training’s Effect on the Comfort and Competency of Resident Physicians. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 48(3), 344–350. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen A. (2018, April 4). Lisa Madigan Pushes for Bill to Require Training Before Treating Sexual Assault Patients. Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/ct-life-lisa-madigan-sane-nurses-legislation-0405-story.html [Google Scholar]

- Cameron C, & Helitzer D. (2003). Impact Evaluation of a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) Program (No. 203276). National Criminal Justice Reference Service. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/203276.pdf

- Campbell R, Bybee D, Townsend S, Shaw J, Karim N, & Markowitz J. (2014). The Impact of Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner Programs on Criminal Justice Case Outcomes: A Multisite Replication Study. Violence Against Women, 20(5), 607–625. 10.1177/1077801214536286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC WISQARS. (2017). Sexual Assault All Injury Causes Nonfatal Injuries and Rates per 100,000 [Data file]. CDC WISQARS. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/nonfatal.html

- Crime in Illinois 2017. (2017). Illinois State Police Uniform Crime Reporting Program. https://www.isp.state.il.us/crime/cii2017.cfm

- Delaney K, Taylor L, & Haviley C. (2019). Registered Nurse Workforce Survey Report 2018. Illinois Nursing Workforce Center. http://nursing.illinois.gov/PDF/2019-01-11_%202018%20RN%20Survey%20Report_Final.pdf

- Delgadillo D. (2017). When There is No Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner: Emergency Nursing Care for Female Adult Sexual Assault Patients. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 43(4), 308–315. 10.1016/j.jen.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehler-Cabral G, Campbell R, & Patterson D. (2011). Adult Sexual Assault Survivors’ Experiences with Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs). Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(18), 3618–3639. 10.1177/0886260511403761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmalter C, Heyns T, & Ferreira R. (2018). Forensic Patients in the Emergency Department: Who Are They and How Should We Care for Them? International Emergency Nursing, 40, 33–36. 10.1016/j.ienj.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde J. (2009). Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—A Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Flatow R, Biggs T, Afayee S, Smoth K, Clark T, & Blake M. (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4884.pdf

- Maier S. (2012). Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners’ Perceptions of the Revictimization of Rape Victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(2), 287–315. 10.1177/0886260511416476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S, Monahan C, Doezema D, & Crandall C. (2007). Implementation and Evaluation of a Training Program for the Management of Sexual Assault in the Emergency Department. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 49(4), 489–494. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for Victims of Crime. (2016). SANE Program Development and Operation Guide. Office for Victims of Crime. https://www.ovcttac.gov/saneguide/introduction/

- Patel A, Panchal H, Piotrowski Z, & Patel D. (2008). Comprehensive Medical Care for Victims of Sexual Assault: A Survey of Illinois Hospital Emergency Departments. Contraception, 77(6), 426–430. 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegram S, & Abbey A. (2016). Associations Between Sexual Assault Severity and Psychological and Physical Health Outcomes: Similarities and Differences Among African American and Caucasian Survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0886260516673626. 10.1177/0886260516673626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, DeGue S, Florence C, & Lokey C. (2017). Lifetime Economic Burden of Rape Among U.S. Adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52(6), 691–701. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt T, Cross TP, & Alderden M. (2017). Qualitative Analysis of Prosecutors’ Perspectives on Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners and the Criminal Justice Response to Sexual Assault. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 13(2), 62 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Zhang X, Basile K, Merrick M, Wang J, Kresnow M, & Chen J. (2018). National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief Updated Release. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf

- The Emergency Medicine Milestone Project. (2015). Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.