Abstract

A 29-year-old pregnant woman presented at 26 weeks of gestation with fever and cough for 4 days. On admission, her nasopharyngeal swab confirmed COVID-19. As her respiratory distress worsened, she was shifted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Since the patient was unable to maintain saturation even on high settings of mechanical ventilation, she underwent venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO) and was monitored in surgical ICU by a multidisciplinary team. The obstetrical team was on standby to perform urgent delivery if needed. Her condition improved, and she was weaned off after 5 days on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. She was observed in the antenatal ward for another week and discharged home with the mother and fetus in good condition. VV-ECMO can be considered as rescue therapy for pregnant women with refractory hypoxaemia of severe respiratory failure due to COVID-19. It can save two lives, the mother and fetus.

Keywords: COVID-19, adult intensive care

Background

Obstetrical critical care patients are very challenging to manage. Prior to COVID-19, obstetrical patients were rarely admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), the overall rate being 2.21 per 1000 women.1 COVID-19 has added to the morbidity and mortality of pregnant and recently delivered women. Almost 4%–6% of women in the childbearing age group, who are critically ill with COVID-19 and admitted to ICU, are pregnant.2 When the other treatment modalities like antiretroviral, corticosteroids, antibiotics, anti-interleukin 6, anticoagulants or mechanical ventilation do not show significant clinical improvement, venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO) can be considered in a small percentage of such pregnant women.

During management of pregnancy with a viable fetus (more than 24 weeks) when the maternal condition deteriorates, there is the usual inclination towards immediate delivery, both to salvage the fetus and to decrease the cardiorespiratory load of the pregnant women. However, this may not be the best option, and in certain cases especially in centres where expertise is available, other options such as VV-ECMO should be preferred rather than delivering an extremely preterm neonate. We present this case report of a patient who underwent VV-ECMO at 26 weeks of gestation and had a good recovery without significant effect on fetal growth. A small but definite portion of COVID-19 infections in pregnancy will progress to severe pneumonia and will require intensive care and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

Until December 2020, our 625-bedded tertiary care multispecialty hospital has managed 120 pregnant women with COVID-19. Out of these, three women required ICU admission and ventilator support. The presented case report is of the only antenatal patient who required ECMO.

Case presentation

A 29-year-old pregnant women presented at 26 weeks of gestation with fever and cough for 4 days to the emergency room at our tertiary care maternity hospital. This was her second pregnancy. In her previous pregnancy, 2 years ago, she had a full-term caesarean delivery. During the present pregnancy, she had regular antenatal visits. Her body mass index was 35 kg/m2. Her anomaly scan at 20 weeks and glucose tolerance test at 24 weeks were normal. Her last routine antenatal visit was 2 weeks prior to the emergency admission.

On admission, her X-ray showed patchy infiltrates suggestive of pneumonia, and nasopharyngeal swab confirmed COVID-19. She was initially admitted to the isolation ward and started on prophylactic medication as per National Guidelines for Clinical Management and Treatment of COVID-19 in the United Arab Emirates.3

As her condition worsened, she was shifted to the ICU by the third day of admission. The antibiotic was changed to intravenous piperacillin–tazobactam. A therapeutic dose of enoxaparin was given, and she was started on continuous positive airway pressure with noninvasive high settings. As her respiratory distress worsened further, she was intubated and given mechanical ventilation (table 1).

Table 1.

Arterial blood gas values and ventilator settings

| ABG | On shift to ICU | On CPAP | On mechanical ventilator | Before ECMO initiation | After ECMO initiation | Day 1 ECMO |

Just prior to ECMO wean off | Just prior to ventilator wean off |

| PH (7.35–7.45) | 7.424 | 7.432 | 7.341 | 7.554 | 7.449 | 7.364 | 7.438 | 7.418 |

| PCO2 (35–45 mm Hg) | 30.6 | 34.6 | 49.5 | 30.4 | 39.0 | 52.9 | 40.6 | 41.2 |

| PO2 (83–108 mm Hg) | 68.3 | 57.1 | 62.1 | 71.1 | 69.2 | 82.0 | 97.4 | 97.1 |

| HCO3 (21–28 mmol/L) | 19.7 | 22.7 | 26.0 | 26.8 | 26.6 | 29.4 | 27.0 | 26.1 |

| BASE (+)(mmol/L) | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 4.2 | 2.9 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 2.0 |

| Lactic acid (0.5–1.6 mmol/L) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Ventilator settings | ||||||||

| FiO2 (%) | 70 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 60 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 97 | 57 | 62 | 71 | 173 | 205 | 243 | 245 |

| SaO2 (95%–99%) | 93.1 | 86.6 | 86.8 | 85.0 | 92.4 | 94.0 | 97.4 | 96.2 |

| PEEP (cm H2O) | 5 | 6 | 15 | 15 | 18 | 9 | 9 | 5 |

ABG, arterial blood gas; BASE, base excess; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; HCO3, bicarbonate; ICU, intensive care unit; PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen; PCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; PH, potential of hydrogen; PO2, partial pressure of oxygen; SaO2, oxygen saturation.

The patient was unable to maintain saturation even on high settings of mechanical ventilation. Her pre-ECMO settings were synchronised intermittent mandatory ventilation with pressure-regulated volume control with fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) 100%, respiratory rate 20, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) 15 cm H20, mean airway pressure 22 and tidal volume 500 mL.

A multidisciplinary team consisting of senior intensivists, cardiothoracic surgeons, obstetricians and anaesthetists decided after a detailed discussion with the patient’s family to opt for ECMO insertion. This was a crucial decision of favouring ECMO over urgent delivery of the fetus, in a critically ill pregnant woman with a viable fetus.

Midazolam (5 mg/hour) and fentanyl (300 µg/hour) on continuous flow were administered for analgesia and sedation, and cisatracurium (8 mg/hour) on flow was used for the neuromuscular block. Effective anticoagulation by heparin infusion was achieved. This was confirmed with an activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) of 53.2 seconds.

Under ultrasound guidance, using the Seldinger technique, 23 French ECMO drainage cannula was inserted in the right femoral vein, and 21 French ECMO return cannula was inserted in the right internal jugular vein. VV-ECMO circuit was initiated with a flow rate of 4.8 L/min, pump speed of 3000 rpm and sweep rate of 4 L/min. The ECMO run was similar to that used in the non-pregnant patients. A senior obstetrician monitored the fetal heart during the process. After inserting the ECMO circuit, the patient was transferred to Dubai Hospital where ECMO facilities are better established for further management.

The patient was monitored in the surgical ICU by a multidisciplinary team of cardiothoracic surgeons, obstetricians, perfusionists, anaesthetists and intensivists. As she was about 27 weeks of gestation, daily fetal cardiotocography was done to monitor her fetus. Her repeat COVID-19 swab after 7 days was negative. The pateint’s condition improved, and she was weaned off ECMO after 5 days. Postdecannulation of ECMO patient maintained haemodynamic stability without inotropic support (table 2).

Table 2.

Timeline of patient condition and management

| Day | General condition | Respiratory support | Investigations | Management |

| Day 1 | Admitted to Isolation ward |

Oxygen via nasal prongs | COVID-19 PCR positive | Budesonide, ceftriaxone Methylprednisolone, enoxaparin Lopinavir–ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine |

| Day 3 | Shifted to ICU | Noninvasive settings CPAP |

ABG deteriorating | Piperacillin–tazobactam Ipratropium |

| Day 4 | Fully sedated | Severe hypoxaemia IPPV |

CKMB Troponin |

Multidisciplinary team review Inotrope support |

| Day 5 | Severe bilateral COVID-19 pneumonia | Intubated SIMV/PRVC |

ECHO | High-risk consent Heparinised prior to ECMO Cisatracurium |

| Day 6 | Under general anaesthesia | VV-ECMO initiated | Daily CTG APTT levels |

Transferred to Dubai Hospital |

| Day 7 to day 10 |

Respiratory parameters improving | On ECMO | COVID-19 PCR negative | On heparin infusion Close fetal surveillance |

| Day 11 | Maintaining normal oxygenation | ECMO weaning and decannulation | ABG improving | Haemodynamically stable without inotrope support |

| Day 12 | Awake and communicating | Extubated | Ferritin D-dimer |

Weaned off mechanical ventilator |

| Day 15 to day 22 |

Ambulating In general ward |

Maintaining saturation | Daily CTG | Haemodynamically stable |

| Day 23 | Discharged home | Normal respiration | Obstetrical Ultrasound Doppler Studies | Enoxaparin, prednisolone, pantoprazole, ambroxol syrup, multivitamins |

ABG, arterial blood gas; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CKMB, creatine kinase muscle brain; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CTG, cardiotocography; ECHO, echocardiogram; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; IPPV, intermittent positive pressure ventilation; SIMV/PRVC, synchronised intermittent mandatory ventilation with pressure-regulated volume control; VV-ECMO, venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The patient was monitored in the general antenatal ward for 1 week. She has regular chest physiotherapy sessions in the ward. The fetal growth parameters and Doppler Studies of the umbilical artery were found to be normal and corresponding to the period of gestation.

Investigations

The patient was monitored on a daily basis for white blood cell count, platelet count, arterial blood gas analysis, coagulation markers, D-dimer and septic markers. Her white blood cell count on day 1 was 8.2 (reference range: 4.5–11×109/L), which increased to 19.9 by day 5 and decreased back to 7.4 by day 7. Her platelet count was between 145 and 198 (reference range: 150–450×109/L), which was essentially normal. Her D-dimer ranged from 1.03 to 1.23 µg/mL fibrinogen-equivalent units (FEU) (reference range: 0.1–0.45 µg/mL FEU), slightly higher than normal.

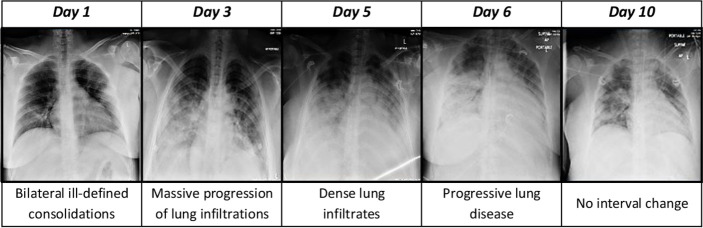

Blood sugar levels, liver function tests and renal function tests were also done. Cardiac markers like troponin T and pro-brain natriuretic peptide) were done to rule out myocardial injury. Ferritin levels were also done daily and were between 36 and 45 ng/mL (reference range: 10–120 ng/mL) during the first 5 days. Later, the ferritin levels increased from 76.8 to 132.9 ng/mL by day 14 of admission. Her chest X-ray findings were indicative of disease severity (figure 1). Her APTT levels (reference range: 30–40 seconds) were monitored while she was on ECMO and were maintained between 50 and 60 seconds.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray findings.

Outcome and follow-up

At discharge, the pregnant woman was at 29 weeks of gestation. She was advised to taper prednisolone by 5 mg every 5 days and enoxaparin to once a day. She had her 32week outpatient antenatal visit and is doing well. The fetal growth parameters were corresponding to the period of gestation. She is scheduled for regular antenatal follow-ups to ascertain adequate fetal growth and is planned for transthoracic echocardiography on an outpatient basis.

Discussion

Acute respiratory distress in the obstetrical population due to viral pneumonia requiring ECMO during the mid-trimester of pregnancy is rare. A review of the literature showed that up until 2016, only 45 cases of ECMO in pregnancy were reported the world over, and most of these were during the H1N1 pandemic. Similar to our patient, most patients reported were in the mid-trimester (26.5 weeks average) and had an average ECMO run for 12.2 days.4 Our patient recovered in 5 days. Survival after VV-ECMO, which is most often used for respiratory failure, was 77.8% for the mother and 65% for the fetus.4

During ECMO, major haemorrhage is the most common complication. In fact, 57.1% of the women in one study needed large-volume blood transfusions.5 The sites of bleeding were intracranial, uterine, the lungs, upper gastrointestinal and from the cannulation site. Fortunately, our patient did not manifest any significant bleeding. If major bleeding was present, it would have necessitated immediate delivery. Some other complications of ECMO in pregnancy that were reported are cannula dislodgement, haemolysis and superadded infections in the blood, urine or the lungs.4

Though VV-ECMO can be considered a rescue therapy for COVID-19-induced severe respiratory distress, significant risks of hypercoagulability and oxygenation failure are to be kept in mind.6 ECMO should be considered in the highly specialised centres only where special teams are in place for constant monitoring, especially when used for the obstetrical patient. This was previously rare, but with the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of patients requiring ECMO can increase significantly.

Another aspect to be considered is ventilator settings during VV-ECMO, and few case reports have suggested that ultraprotective ventilation strategy of maintaining a peak inspiratory pressure of less than 20 cm H2O and PEEP of less than 10 cm H20 can prevent ventilator-induced lung injury. Long-term and increased number of studies will be required to determine the appropriate approach.7

Muscle paralysis and prone position are an integral part of the protocol for a patient with acute severe respiratory distress in ICU; our patient was put in the prone position when initially admitted to the ICU, but as her condition worsened very quickly, she had to be initiated on ECMO. Prone position can be used during pregnancy in even advanced gestations with adequate support to the gravid uterus to improve ventilation.8

Methylprednisolone 40 mg intravenous, two times per day, was given for COVID-19 pneumonitis. After weaning from ECMO therapy, she was continued on oral prednisolone 30 mg daily, which was tapered gradually. We prefer to use intramuscular betamethasone for fetal lung maturity, but since we had decided for ECMO and not to deliver the preterm fetus, we did not consider steroid for fetal lung maturity or magnesium for neuroprotection (which we would have if we had planned for delivery).

Anticoagulation with enoxaparin was started as a part of management of critically ill pregnant patient with high BMI, which was followed by heparin infusion during the ECMO run. She continued on enoxaparin after weaning off ECMO. There are many novel techniques of ECMO, where anticoagulation can be used minimally or avoided completely.9 This was our first case of COVID-19 and ECMO in an antenatal patient; hence, we chose to go with anticoagulation protocol.

There is inadequate data about the safety of ECMO in pregnancy, although it is a life-saving rescue therapy for acute refractory hypoxaemia mostly due to viral pneumonia, either H1N1 (influenza A virus subtype H1N1), Middle East respiratory syndrome or COVID-19. In a ten-year study of ECMO in pregnancy, only 60% of mothers and fetuses survived.10 Long-term follow-up of our patient and detailed evaluation of future cases can help evaluate efficacy and safety of ECMO in pregnancy.

We intend to follow our mother and her baby to analyse any long-term effects of VV-ECMO during the mid-trimester of pregnancy on both.

Patient’s perspective.

I realise that my baby and I am very lucky in comparison to so many others who have not been able to survive this Corona virus pandemic. I hope to deliver my baby on the due date without any more setbacks. Really grateful.

Learning points.

Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is a feasible option for pregnant women with refractory hypoxaemia due to COVID-19 pneumonia when all else seems to have failed.

Multidisciplinary team consisting of obstetricians, intensivists, cardiothoracic surgeons, perfusionists, anaesthetists, neonatologists, physiotherapists and nurses needs to work in close coordination to provide optimum care.

Appropriate counselling and clear communication with relatives are needed, as the lives of both the mother and unborn child are at stake.

Long-term outcome of both mothers and fetuses needs to be followed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all physicians, nursing and paramedical staff involved in taking care of this patient. Appreciate Dr Obaid AlJassim, Pradeep Kumar Pillai, Suresh Babu Robert and others for the ECMO run.

Footnotes

Contributors: ZYT: design, draft and revision of the manuscript. ZTH: data acquisition. LKH: clinical care, conceptualisation and proof-reading. MAR: conceptualisation and proof-reading. Final version for publication was agreed upon by all authors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Jardine J, NMPA Project Team . Maternity admissions to intensive care in England, Wales and Scotland in 2015/16: a report from the National maternity and perinatal audit. London: RCOG, 2019. Available: https://maternityaudit.org.uk/FilesUploaded/NMPA%20Intensive%20Care%20sprint%20report.pdf [Accessed cited 08 May 2020].

- 2.Lambert J, Litchfield K. Love C.COVID-19 position statement: Maternal critical care provision. SIGN evidence based clinical guidelines. Coronavirus (COVID-19): guidance on treating patients Guidance from the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) Approved date: 18/05/2020, Publication date: 19/05/2020, Version number: 1.0. Available: https://www.sign.ac.uk/media/1633

- 3.Version 3.1 United Arab Emirates ministry of health and prevention National guidelines for clinical management and treatment of COVID-19,, 2020. Available: https://www.mohap.gov.ae

- 4.Moore SA, Dietl CA, Coleman DM. Extracorporeal life support during pregnancy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;151:1154–60. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nair P, Davies AR, Beca J, et al. . Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe ARDS in pregnant and postpartum women during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Intensive Care Med 2011;37:648–54. 10.1007/s00134-011-2138-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmadi ZH, Jahangirifard A, Farzanegan B. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and COVID‐19: the causes of failure. J Card Surg 2020:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park MH, Kim AJ, Lee M-J, et al. . Case report of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by COVID-19: successfully treated by venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and an Ultra-Protective ventilation. Medicina 2020;56:570 10.3390/medicina56110570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray BR, Trikha A. Prone position ventilation in pregnancy: concerns and evidence. J Obstet Anaesth Crit Care 2018;8:7–9 https://DOI:10.4103/joacc.JOACC_17_18 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sklar MC, Sy E, Lequier L, et al. . Anticoagulation practices during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure. A systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13:2242–50. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201605-364SR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webster CM, Smith KA, Manuck TA. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in pregnant and postpartum women: a ten-year case series. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2020;2:100108. 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]