Abstract

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B (MEN2B) is the rarest and most aggressive of the MEN syndromes. It is characterised by medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), pheochromocytoma, marfanoid body habitus, mucosal neuromas and colonic dysfunction. Patients typically present with chronic constipation and MTC in early childhood. We discuss an atypical late presentation of MEN2B in a 19-year-old man with chronic constipation since childhood admitted with acute spinal cord compression. He underwent emergent neurosurgical intervention followed by postoperative radiotherapy. Bone biopsy revealed metastatic pheochromocytoma. Thyroid nodule biopsy showed MTC. MIBG scan confirmed pheochromocytoma as the dominant malignancy. Germline testing revealed a RET mutation (p.M918T). He received one cycle of cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dacarbazine and subsequently developed a pathological right femur fracture requiring repair. Postoperative course was complicated by hypoxic respiratory failure requiring intubation. Imaging showed lymphangitic spread of disease in the lungs. He unfortunately did not respond to a short trial of sunitinib and transitioned to comfort care.

Keywords: adrenal disorders, thyroid disease, endocrine cancer

Background

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2) is a group of autosomal dominant syndromes associated with tumours of the thyroid, parathyroid and adrenal glands. It can be further divided into two distinct clinical entities: type 2A (MEN2A) and type 2B (MEN2B). MEN2B is both the rarest and most aggressive subtype. Its prevalence is estimated to be between 1 in 600 000 and 1 in 4 million.1 Both subtypes are associated with pheochromocytoma and medullary thyroid cancer (MTC). However, MTC tends to present earlier and behaves more aggressively in patients with MEN2B.

Patients with MEN2B also have a unique constellation of non-endocrine manifestations: mucosal neuromas (usually of the lips and tongue), marfanoid body habitus and severe colonic dysfunction. They typically present with severe constipation in infancy and can develop megacolon later in life.2 One case series of patients with MEN2B found 63% had megacolon, often requiring surgical intervention.3 MEN2 is caused by an activating germline mutation in the RET oncogene. In MEN2B, 95% of cases are associated with a point mutation in exon 16 (p.M918T).4

Virtually all patients with MEN2B develop MTC and roughly half develop pheochromocytoma. Successful management of these patients is highly dependent on early diagnosis and treatment of these often fatal endocrine malignancies.5 6 We report an atypical late presentation of MEN2B with metastatic pheochromocytoma in an otherwise healthy 19-year-old man (with a history significant only for chronic constipation since childhood) admitted with acute spinal cord compression. Imaging was significant for diffuse osseous metastases, a right adrenal mass, thyroid/pulmonary nodules and severe megacolon. Bone biopsy revealed metastatic pheochromocytoma and fine needle aspiration (FNA) of the thyroid nodule demonstrated MTC. Germline testing was positive for an activating point mutation in the RET oncogene (p.M918T) consistent with a diagnosis of MEN2B.

Case presentation

A 19-year-old man presented as a trauma alert after feeling an audible pop in his back on standing from a seated position while playing video games. He experienced immediate pain that caused him to fall to the floor with decreased sensation and weakness in his bilateral lower extremities. Past medical history was notable only for severe chronic constipation since childhood. He had been hospitalised 5 years prior to admission with faecal impaction. He had no family history of medullary thyroid cancer, pheochromocytoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia specifically. Vital signs were notable for tachycardia with pulse in the 110s. On examination, the patient was noted to be very thin and tall appearing with abdominal distension and bilateral lower extremity weakness. Trauma CT scan revealed a fracture of the L2 vertebra with spinal injury due to retropulsion of a large bony fragment into the spinal canal (figure 1). Incidentally, the CT scan also detected significant colonic distension without obstruction and a heterogenous right adrenal mass measuring 9×11 cm (figure 2).

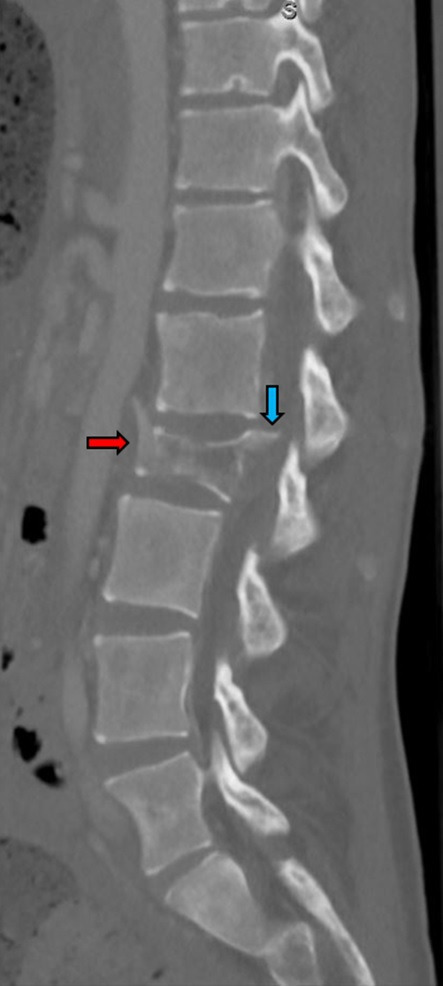

Figure 1.

CT scan of the lumbar spine (sagittal view) showing pathological fracture of the L2 vertebra (red arrow) with retropulsion of a bone fragment into the spinal canal (blue arrow).

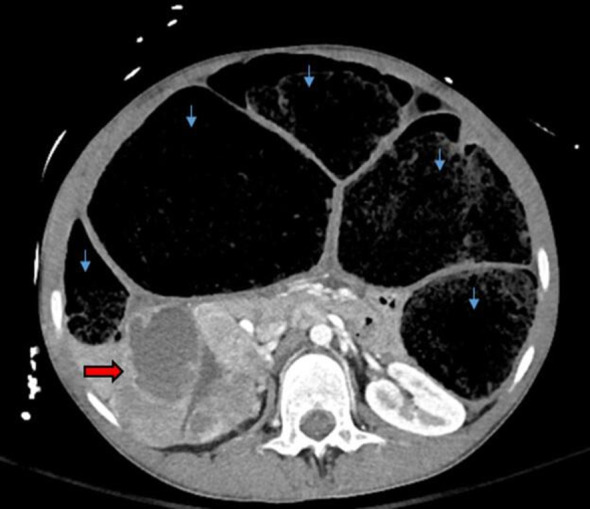

Figure 2.

CT scan of the abdomen (axial view) showing a right adrenal mass (red arrow) measuring 9×11 cm. Also noted was severe colonic distension without evidence of obstruction (blue arrows).

Investigations

MRI of the lumbar and thoracic spine detected diffuse osseous metastatic disease throughout the thoracic, lumbar and sacral spine. CT scan of the chest demonstrated multiple small pulmonary nodules consistent with metastatic disease. Laboratories were notable for calcitonin 799 pg/mL (range <=14.3 pg/mL), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) 59.9 ng/mL (range <5 ng/mL), plasma metanephrines 6.3 nmol/L (range <0.50 nmol/L), 24-hour urine fractionated metanephrines 4144 mcg every 24 hours (range <261 mcg normotensive and <400 mcg hypertensive), normetanephrine 5782 mcg every 24 hours (range <390 mcg normotensive and <900 mcg hypertensive). The patient underwent CT-guided biopsy of the right iliac bone which demonstrated metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasm. Malignant pheochromocytoma was favoured over MTC as calcitonin, Pax-8, TTF-1, CK AE1/3, CK7 and Cam 5.2 stains were negative. Ultrasound of the thyroid showed hypoechoic nodules in the right and left lobes. FNA of the thyroid was consistent with MTC. Somatic next-generation sequencing was performed and revealed pathological RET mutation (p.M918T) with allele frequency of 58.86%. This was later confirmed by germline testing. MIBG scan was performed and revealed diffuse osseous activity and focal activity in the thorax and right adrenal gland (figure 3).

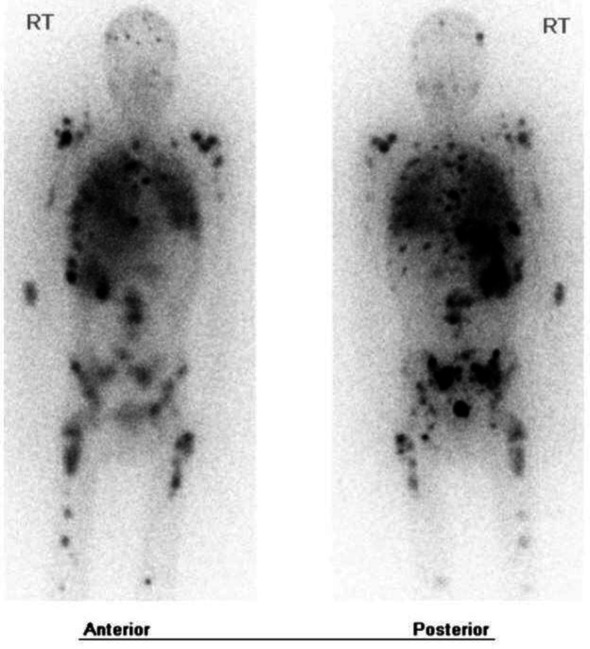

Figure 3.

MIBG scan showing areas of increased radiotracer uptake in the right adrenal gland, thorax, appendicular skeleton and axial skeleton (black).

Differential diagnosis

The initial elevated CEA and colonic distension with pathological fracture raised concern for a metastatic colorectal malignancy. However, this did not fit with the patient’s marfanoid body habitus and adrenal mass. The diagnosis of MEN2B became obvious with elevated calcitonin levels and bone biopsy confirmation of a neuroendocrine neoplasm. Both somatic and germline testing revealed the pathological RET p.M918T mutation, which is specific for MEN2B. Thereafter, the diagnostic dilemma focussed more on the source of the patient’s metastatic disease given he had both biopsy proven MTC and malignant pheochromocytoma. MIBG scan did not reveal significant activity in the thyroid. Thus pheochromocytoma was favoured to be the dominant malignant process.

Treatment

The patient underwent emergent T12-L4 fusion, L1-L3 decompression and posterior treatment of his L2 fracture. This was followed by postoperative radiation (30 GY in 10 fractions) to the lumbar spine and symptomatic right hip lesion. The patient suffered delays in initiation of systemic therapy due to financial/insurance constraints. He was unable to receive iobenguane I-131 at our institution and was ultimately dispositioned to cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dacarbazine chemotherapy (CVD).

Outcome and follow-up

The patient tolerated one cycle of CVD chemotherapy but required re-admission to the hospital after developing a pathological right femur fracture. He was transferred to an outside institution for orthopaedic oncology evaluation and underwent right femur resection and replacement. Following the surgery, he developed progressive hypoxic respiratory failure with suspected lymphangitic spread of tumour on imaging. He was transitioned to sunitinib therapy very briefly but ultimately decided to pursue hospice care due to the overwhelming burden of disease. He later died during the hospital admission.

Discussion

MEN2B is commonly defined by aggressive MTC, pheochromocytoma and multiple extra-endocrine pathologies.2 MEN2B is associated with a mutation in codon 918 in exon 16 in more than 90% of cases, which was identified in our patient.1 Interestingly, up to half of MEN2B cases are thought to arise de novo without preceding family history as was the case with our patient.7 His first manifestation of malignancy was a lumbar vertebral pathological fracture. Skeletal related events can be the initial presentation of pheochromocytoma in up to 30% of patients.8 As many as 90% of patients with MEN2B will also have some form of colon pathology, with chronic constipation being the most common manifestation.2 Our patient suffered from chronic constipation throughout childhood, which was the strongest initial clue to his diagnosis. He had marfanoid body habitus, but no obvious mucosal neuromas. He also had features of megacolon on imaging, which has been described in as many as 63% of patients with MEN2B.3 Our patient’s history of severe constipation with faecal impaction should have served as an indicator of the underlying MEN syndrome. Earlier diagnosis could have led to intervention prior to the development of metastatic pheochromocytoma.

Metastatic pheochromocytoma is a very rare finding in patients with MEN2B and is sparsely characterised in the literature. Other case reports have more commonly cited metastatic malignant pheochromocytoma as a rare initial presenting entity in MEN2A. It is estimated to be identified in MEN2A with an incidence of 3% to 4%.9 To be the initial presenting feature in MEN2B is thought to be even rarer, as these patients are expected to have a more aggressive variant of MTC which usually presents first.10 A retrospective review of patients with MEN2 over a 50-year time period at a large academic institution identified 85 patients with both MEN2 and pheochromocytoma.11 Only 15 of these patients were found to have the diagnosis of MEN2B. Two patients died directly from complications of pheochromocytoma (both linked to hypertensive crisis). Our case is unusual because our patient ultimately passed due to overwhelming tumour burden causing respiratory compromise, and not due to acute cardiovascular complications of pheochromocytoma. This highlights the importance of proper screening of younger patients diagnosed with MEN2B, which can almost universally prevent the development of delayed pheochromocytoma metastasis.12

The MIBG scan was helpful in this case because it tipped the scales in favour of the pheochromocytoma as the dominant malignancy over MTC. This was also supported by the pathology from the bone biopsy. The patient was treated with one cycle of CVD prior to developing additional skeletal-related complications. He had delays in his care due to financial constraints during which time his overall performance status worsened, which likely diminished the probability of successful treatment. In one prior prospective study of patients treated with CVD chemotherapy, overall response rate was 55%, with 11% of patients achieving a complete response.13 It is difficult to know if the patient would have had a better response had he undergone a sufficient trial of tyrosine kinase inhibitor based therapy. Unfortunately, sunitinib has not proven to be particularly effective in patients with progressive pheochromocytoma with response rates of approximately 15%.14 Iobenguane I-131 would have been a strong consideration had it been available as response rates of up to 47% have been seen in prior case series.15 The rare nature of the MEN2B and metastatic pheochromocytoma will continue to challenge the development of more active therapeutics.

Learning points.

Medullary thyroid cancer in multipleendocrine neoplasia type 2B (MEN2B) typically presents in a more aggressive manner than MEN2A.

Metastatic pheochromocytoma is an atypical first manifestation of MEN2B. Typically medullary thyroid carcinoma precedes pheochromocytoma.

In addition to medullary thyroid carcinoma and pheochromocytoma, MEN2B syndrome is also commonly associated with abnormal colonic development including chronic constipation and megacolon.

Treatment of advanced stage MEN2B is dependent on identification of the primary dominant malignancy.

Footnotes

Contributors: GJ was personally involved in drafting the case report, critical revision of the report and final approval of the version to be published. HH was personally involved in drafting the case report, critical revision of the report and final approval of the version to be published. AE-F was personally involved in drafting the case report, critical revision of the report and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Znaczko A, Donnelly DE, Morrison PJ. Epidemiology, clinical features, and genetics of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B in a complete population. Oncologist 2014;19:1284–6. 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Riordain DS, O'Brien T, Crotty TB, et al. . Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B: more than an endocrine disorder. Surgery 1995;118:936–42. 10.1016/S0039-6060(05)80097-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibbons D, Camilleri M, Nelson AD, et al. . Characteristics of chronic megacolon among patients diagnosed with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B. United European Gastroenterol J 2016;4:449–54. 10.1177/2050640615611630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martucciello G, Lerone M, Bricco L, et al. . Multiple endocrine neoplasias type 2B and RET proto-oncogene. Ital J Pediatr 2012;38:9. 10.1186/1824-7288-38-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasen HF, van der Feltz M, Raue F, et al. . The natural course of multiple endocrine neoplasia type IIb. A study of 18 cases. Arch Intern Med 1992;152:1250–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makri A, Akshintala S, Derse-Anthony C, et al. . Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B presents early in childhood but often is undiagnosed for years. J Pediatr 2018;203:447–9. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson KM, Bracamontes J, Jackson CE, et al. . Parent-Of-Origin effects in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B. Am J Hum Genet 1994;55:1076–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayala-Ramirez M, Palmer JL, Hofmann M-C, et al. . Bone metastases and skeletal-related events in patients with malignant pheochromocytoma and sympathetic paraganglioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:1492–7. 10.1210/jc.2012-4231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pal R, Rastogi A, Kumar S, et al. . Metastatic pheochromocytoma in men 2A: a rare association. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018:222758. 10.1136/bcr-2017-222758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raue F, Frank-Raue K, Grauer A. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. clinical features and screening. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1994;23:137–56. 10.1016/S0889-8529(18)30121-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thosani S, Ayala-Ramirez M, Palmer L, et al. . The characterization of pheochromocytoma and its impact on overall survival in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:E1813–9. 10.1210/jc.2013-1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castinetti F, Moley J, Mulligan L, et al. . A comprehensive review on MEN2B. Endocr Relat Cancer 2018;25:T29–39. 10.1530/ERC-17-0209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang H, Abraham J, Hung E, et al. . Treatment of malignant pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine: recommendation from a 22-year follow-up of 18 patients. Cancer 2008;113:2020–8. 10.1002/cncr.23812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Kane GM, Ezzat S, Joshua AM, et al. . A phase 2 trial of sunitinib in patients with progressive paraganglioma or pheochromocytoma: the SNIPP trial. Br J Cancer 2019;120:1113–9. 10.1038/s41416-019-0474-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gedik GK, Hoefnagel CA, Bais E, et al. . 131I-Mibg therapy in metastatic phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2008;35:725–33. 10.1007/s00259-007-0652-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]