Abstract

A 54-year-old Chinese man presented with ascites for 2 weeks. He had a preceding 2-year history of intermittent dysphagia, lethargy and general malaise. Blood investigations revealed leucocytosis with eosinophilia of 26.5%, whereas paracentesis showed turbid fluid with high protein content (45 g/L) and a high white blood cell count of 5580/µL, predominantly eosinophils (90%). An incidental assay of vitamin D showed a very low level of 13.5 ng/mL. No other cause of ascites was found. Gastroscopy was normal except for duodenitis. However, biopsies from lower oesophagus confirmed the presence of eosinophilic infiltration. Following vitamin D replacement, the patient experienced marked improvement in symptoms of dysphagia within 2 weeks and no recurrence of ascites after 3 months. The reason for the patient’s vitamin D deficiency remains unclear. The marked improvement in the patient’s health indicates a causative role of vitamin D deficiency in causing eosinophilic esophagogastroenteritis and associated eosinophilic ascites.

Keywords: stomach and duodenum, immunology, small intestine

Background

Vitamin D has been thought to play a critical role in calcium homeostasis and maintenance of bone health. However, recent studies have shown that its deficiency can result in a wide spectrum of clinical effects, ranging from asthma, eczema, food allergies and even certain types of cancer. Eosinophilic esophagitis (EE) with or without gastroenteritis is an uncommon condition characterised by infiltration of eosinophils into the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and usually thought to be allergic or immunogenic in nature. We report a case of eosinophilic esophagogastroenteritis in a 54-year-old man who presented with ascites for 2 weeks. He had consulted many doctors for lethargy and intermittent dysphagia for the past 2 years without any definite diagnosis being made. During his present visit, his serum vitamin D level was incidentally found to be low. He was given high-dose replacement of vitamin D, which resulted in complete resolution of his symptoms after 3 months.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old man presented with lethargy and general malaise for 2 years associated with intermittent dysphagia and recent progressive abdominal distension for 2 weeks. Physical examination revealed an asthenic man with moderate ascites without any leg oedema. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

He had undergone many tests in the past, including blood tests, upper and lower GI endoscopies, and abdominal and pelvic CT scan in 2018, which showed mild duodenitis on gastroscopy and thickened gastro-oesophageal junction on CT scan. These findings were thought to be non-specific, and no duodenal or oesophageal biopsies were taken.

However, a full blood examination at our hospital showed leucocytosis (total white blood cell (TWBC) of 17×109/L) with 26.5% of eosinophils (4.5×109/L) and peripheral eosinophilia. His renal and liver function tests were normal. Urinalysis did not show any albuminuria. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed ascites and circumferential thickening involving the lower oesophagus (figure 1A), gastric antrum (figure 1B) and proximal jejunum (figure 1C).

Figure 1.

A CT scan showing (A) thickening of the lower oesophagus, (B) thickening of the antrum and first part of the duodenum and (C) thickening of the upper jejunum (arrow).

A total abdominal paracentesis was performed with 3 L of turbid fluid removed with a protein level of 45 g/L and the presence of 5580/µL of WBCs, predominantly eosinophils (90%) (figure 2). There was no microorganism or malignant cells present.

Figure 2.

Ascitic fluid showing eosinophils (arrow).

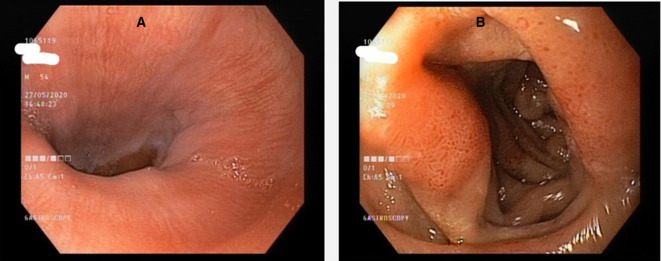

We proceeded with a gastroscopy which showed normal mucosa at the lower oesophagus and mild mucosal inflammation consisting of erythematous patches in the first part of the duodenum (figure 3). Rapid urease test for Helicobacter pylori was negative.

Figure 3.

Endoscopic view of the (A) lower oesophagus and (B) first part of the duodenum showing mucosal oedema and thickening.

However, biopsies from the lower oesophagus showed dense eosinophilic infiltration of more than 50 per high-power field involving the mucosal, submucosal and muscularis layers (figure 4)

Figure 4.

Histological picture of a biopsy of the lower oesophagus showing eosinophilic infiltration (arrow) (×40 magnification, H&E stain).

The raised eosinophilic counts, together with eosinophilic infiltration into the GIT in the absence of any other aetiology, finally led to the diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagogastroenteritis in this patient. As part of routine blood tests for his constitutional symptoms, his vitamin D levels were assessed and were found to be very low (13.5 ng/mL).

Treatment

As no other aetiology was identified for his current condition except vitamin D deficiency, he was empirically prescribed vitamin D in the form of cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) 8000 IU/day and advised to get some sun exposure (15–20 min of direct sunlight daily). To ensure that he was responding to the treatment and compliant to the medication, he was asked to return to follow-up after 2 weeks.

Outcome and follow-up

During his first follow-up after 2 weeks, he was found to be better with no recurrence of ascites. His repeat serum vitamin D level had risen to 32.5 ng/mL. He was advised to continue with the current medication and to come back in 1 month.

His subsequent follow-up at 1 month showed normalisation of his TWBC and eosinophil counts to 6.9×109/L with 9.2% eosinophils (0.63×109/ L), respectively, with a corresponding vitamin D level of 72 ng/mL. Clinically he remained well with no recurrence of ascites. He was advised to reduce his vitamin D replacement to 4000 IU/day.

During follow-up at 3 months, his TWBCs remained normal at 6.9×109/L with 5.7% eosinophils (0.39×109/L) and a corresponding vitamin D level of 65 ng/mL. He remained totally asymptomatic. A repeat abdominal CT scan showed complete resolution of mucosal thickening previously noted at lower oesophagus (figure 5A), gastric antrum (figure 5B) and proximal jejunum (figure 5C) with no recurrence of ascites.

Figure 5.

A CT scan showing resolution of the swelling of the (A) lower oesophagus, (B) antrum and (C) first part of the duodenum and proximal jejunum following vitamin D supplementation.

A repeat gastroscopy showed complete healing of the duodenitis, whereas biopsies from the lower oesophagus showed disappearance of previously observed eosinophilic infiltration (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Histological picture of biopsy of the lower oesophagus showing complete resolution of the eosinophilic infiltration following vitamin D supplementation (×40 magnification, H&E stain).

He was advised to further reduce his vitamin D supplementation to 2000 IU/day and to come back in 6 months.

Discussion

EE and eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) are increasingly recognised as part of a spectrum of an allergic condition characterised by infiltration of eosinophils into the GIT. The resultant symptoms experienced by the patient would depend on the site and degree of infiltration of eosinophils, giving rise to a wide spectrum of GI symptoms. These conditions can affect both paediatric and adult patients. As there are no specific endoscopic and radiological findings in these conditions, histological confirmation of eosinophilic infiltration remains a key feature in diagnosing these conditions. Hence, many patients with EE and EGE often present with non-specific GI symptoms, and the diagnosis is missed as had happened with our patient.

Although several reports have shown an increased incidence of EE in Western populations in recent years,1 EGE remains an uncommon condition. EE and EGE are thought to be linked to an increase in exposure to allergens particularly in food. Klein et al subdivided this condition into three types depending on the depth of infiltration and inflammation with eosinophils—that is, mucosal dominant, muscularis dominant and serosal dominant forms.2 The triggers to this type of inflammatory process in the GIT are, however, not well understood. Many patients with EGE had a positive history of allergic conditions, drug or food allergies,3–5 or a family history of allergies.6 However, in our patient no such history exists.

Our patient demonstrated both features of EE and EGE characterised by dysphagia and ascites, respectively. The reason for dysphagia is most likely due to the thickening and luminal narrowing (as seen on CT scan) caused by infiltration of eosinophils into the muscularis layers, despite endoscopically normal appearance. This is supported by histological findings of dense eosinophilic infiltration into the mucosal, submucosal and muscularis layers in our biopsies of the lower oesophagus. We postulated that the intermittent nature of his dysphagia over the last 2 years could have been due to fluctuations in his serum vitamin D levels. Interestingly, this patient also had ascites with abundant eosinophils found in the ascitic fluid, signifying the serosal involvement in EGE, which often leads to ascites. It is, however, the least common type of involvement in EGE. Indeed, eosinophilic ascites (EA) is an unusual7 and difficult-to-diagnose cause of unexplained ascites without the histological confirmation of concurrent eosinophilic infiltration in the GIT. To date, there has been no reported case of EA secondary to vitamin D deficiency.

The mainstay of treatment for EE or EGE is usually through food elimination (if food allergy is identified) or corticosteroids. However, this patient was given only empirical treatment with vitamin D based on the fact that no overt allergen was identified. The dramatic resolution of clinical symptoms and the non-recurrence of unexplained ascites with vitamin D supplementation alone point to the role of vitamin D deficiency in the causation of EE and EGE in our patient. The complete resolution of previous histological, haematological and radiological findings following treatment in our patient strongly supports that vitamin D deficiency was the aetiological factor for EE and EGE in this patient.

There has been no previous report on the association of vitamin D deficiency and EGE, although previous reports have shown an association between low serum vitamin D levels and EE from a cohort of 35 adults and 34 paediatric patients in a US population.8 In this study, serum vitamin D levels were found to be low in these subjects, and a higher number of subjects with ‘insufficient’ levels had positive skin prick test reaction to peanuts.8

The exact pathophysiological role of vitamin D deficiency in EE is not clear. It is thought that vitamin D plays a critical role in the modulation of immune responses. In animal studies, vitamin D has been shown to be important in the maintenance of intact intestinal mucosal barrier, as evidenced by the fact that disruptions in epithelial junctions occurred in vitamin D receptor knockout mice.9 This could lead to increased exposure of the gastrointestinal tract to allergens, inducing inflammatory responses from the immune system.

Vitamin D has been shown to have extensive effects on multiple immune cell functions. Cantorna and Mahon10 in an excellent review of the subject have described the role of vitamin D in regulating and balancing T helper Th1 and Th2 responses and preventing the development of autoimmune diseases. Litonjua and Weiss11 have also hypothesised that with vitamin D, regulatory T cells (Tregs) play an important role in suppressing inappropriate Th1 and Th2 responses to environmental exposure such as allergens and infections. When vitamin D is deficient, Tregs are not able to regulate Th1 or Th2 responses sufficiently or appropriately, resulting in the disease. It is now a well-recognised fact that vitamin D deficiency may precipitate or worsen several autoimmune conditions such as multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis.12 13

Vitamin D is produced by the human body following direct skin exposure to ultraviolet B rays in sunlight. However, many factors such as seasonal changes in sunlight, higher latitudes, wearing protective clothing, darker skin colour, obesity and the widespread use of sun blocks may diminish the amount of vitamin D that can be generated from sun exposure. The amount of vitamin D found in dietary sources (fatty fish, dairy products, food fortified with vitamin D, etc) is often limited and cannot fulfil the daily vitamin D requirements for most people.

Vitamin D insufficiency is now recognised as a global health problem, as people living in modern societies are generally spending less time outdoors. It has been estimated that up to 42% of adult and 15% of paediatric populations in the USA are vitamin D deficient.14 15 In a population study involving large number of subjects, one-third of UK adults in primary care were found to be vitamin D deficient, with higher rates among ethnic minority patients.16 Even in tropical countries such as Malaysia,17–19 Singapore,20 21 Vietnam22 and Indonesia,18 23 vitamin D insufficiency is paradoxically found to be prevalent despite the perennial presence of sunlight. One of the reasons could be the inordinate concern that excessive sun exposure would cause skin cancer, which results in the widespread use of sunscreens and protective clothing. This is partly fuelled by certain cosmetic and pharmaceutical companies. Our patient is a small business owner who admitted to spending very little time outdoors.

Vitamin D supplementation in the form of oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) offers a simple, safe and effective way of restoring a deficient state, and toxicity is extremely rare, even when taken in high doses. The safest way is interval monitoring of serum vitamin D levels with dosage adjustments based on blood test results to achieve an optimum blood level.

We conclude that vitamin D deficiency is common and serum vitamin D level should be checked in all patients with EE and EGE. When deficiency is detected, as illustrated in our case, supplementation with vitamin D offers a simple, inexpensive and effective treatment for these patients.

We believe this is the first case in the medical literature reporting on vitamin D deficiency causing EE and EGE with ascites.

Patient’s perspective.

I had been unwell for almost 2 years, but multiple consultations with doctors were unhelpful in coming to a conclusive diagnosis. I was convinced that I had some sort of cancer likely in the abdomen. There were periods when I felt better and could work, but most of the times I was tired and feeling listless. As my doctors have pointed out to me, my symptoms were generally non-specific but pointed to a problem in the gastrointestinal tract. These came to a ‘head’ with the development of abdominal swelling which made me very anxious. I was prepared to undergo any tests or even surgery.

I am truly overjoyed that the doctors at the Makhota Hospital have been able to diagnose my problem and instituted effective therapy with vitamin D supplementation. It has been a miracle!

I never thought that I would be deficient in vitamin D, having assumed that living in a sunny tropical country this would never be a problem. However, I do work indoors mostly and like most Asian men spend most of our time working at the office with few outdoor recreational or sports activities. I am truly grateful to the doctors who have restored my health so quickly and miraculously.

Learning points.

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is an uncommon cause of unexplained ascites.

Vitamin D deficiency is a rare cause of this condition which is usually considered idiopathic.

Vitamin D deficiency can be subtle and often remain unsuspected and undiagnosed.

Footnotes

Contributors: The patient was under the care of C-SQ. Report was written by C-SQ and K-LG with contributions by KS and K-BP for the figures.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Navarro P, Arias Ángel, Arias-González L, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the growing incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults in population-based studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;49:1116–25. 10.1111/apt.15231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein NC, Hargrove RL, Sleisenger MH, et al. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Medicine 1970;49:299–320. 10.1097/00005792-197007000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen ET, Martin CF, Kappelman MD, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic gastritis, gastroenteritis, and colitis: estimates from a national administrative database. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;62:36–42. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang JY, Choung RS, Lee RM, et al. A shift in the clinical spectrum of eosinophilic gastroenteritis toward the mucosal disease type. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:669–75. 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingle SB, Hinge Ingle CR. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: an unusual type of gastroenteritis. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:5061–6. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i31.5061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reed C, Woosley JT, Dellon ES. Clinical characteristics, treatment outcomes, and resource utilization in children and adults with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Dig Liver Dis 2015;47:197–201. 10.1016/j.dld.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hepburn IS, Sridhar S, Schade RR, Iryna SH, Subbaramiah S, Robert RS. Eosinophilic ascites, an unusual presentation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a case report and review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2010;1:166–70. 10.4291/wjgp.v1.i5.166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slack MA, Ogbogu PU, Phillips G, et al. Serum vitamin D levels in a cohort of adult and pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015;115:45–50. 10.1016/j.anai.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kong J, Zhang Z, Musch MW, et al. Novel role of the vitamin D receptor in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2008;294:G208–16. 10.1152/ajpgi.00398.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. D-hormone and the immune system. J Rheumatol Suppl 2005;76:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litonjua AA, Weiss ST. Is vitamin D deficiency to blame for the asthma epidemic? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:1031–5. 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang H-L, Wu J. Role of vitamin D in immune responses and autoimmune diseases, with emphasis on its role in multiple sclerosis. Neurosci Bull 2010;26:445–54. 10.1007/s12264-010-0731-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blaney GP, Albert PJ, Proal AD. Vitamin D metabolites as clinical markers in autoimmune and chronic disease. Eur J Clin Invest 2005;35:290–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vieth R, Bischoff-Ferrari H, Boucher BJ, et al. The urgent need to recommend an intake of vitamin D that is effective. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:649–50. 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA. Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988-2004. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:626–32. 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowe FL, Jolly K, MacArthur C, et al. Trends in the incidence of testing for vitamin D deficiency in primary care in the UK: a retrospective analysis of the health improvement network (thin), 2005-2015. BMJ Open 2019;9:e028355. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chin K-Y, Ima-Nirwana S, Ibrahim S, et al. Vitamin D status in Malaysian men and its associated factors. Nutrients 2014;6:5419–33. 10.3390/nu6125419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green TJ, Skeaff CM, Rockell JEP, et al. Vitamin D status and its association with parathyroid hormone concentrations in women of child-bearing age living in Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008;62:373–8. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Sadat N, Majid HA, Sim PY, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in Malaysian adolescents aged 13 years: findings from the Malaysian Health and Adolescents Longitudinal Research Team study (MyHeARTs). BMJ Open 2016;6:e010689. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neo JJ, Kong KH, Neo JJ. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation unit in tropical Singapore. Rehabil Res Pract 2016;2016:1–6. 10.1155/2016/9689760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bi X, Tey SL, Leong C, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in Singapore: its implications to cardiovascular risk factors. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147616. 10.1371/journal.pone.0147616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen HTT, von Schoultz B, Nguyen TV, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in northern Vietnam: prevalence, risk factors and associations with bone mineral density. Bone 2012;51:1029–34. 10.1016/j.bone.2012.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poh BK, Rojroongwasinkul N, Nguyen BKL, et al. 25-Hydroxy-Vitamin D demography and the risk of vitamin D insufficiency in the South East Asian nutrition surveys (SEANUTS). Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2016;25:538–48. 10.6133/apjcn.092015.02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]