Abstract

Objective

To summarise the methodological aspects in studies with work participation (WP) as outcome domain in inflammatory arthritis (IA) and other chronic diseases.

Methods

Two systematic literature reviews (SLRs) were conducted in key electronic databases (2014–2019): search 1 focused on longitudinal prospective studies in IA and search 2 on SLRs in other chronic diseases. Two reviewers independently identified eligible studies and extracted data covering pre-defined methodological areas.

Results

In total, 58 studies in IA (22 randomised controlled trials, 36 longitudinal observational studies) and 24 SLRs in other chronic diseases were included. WP was the primary outcome in 26/58 (45%) studies. The methodological aspects least accounted for in IA studies were as follows (proportions of studies positively adhering to the topic are shown): aligning the studied population (16/58 (28%)) and sample size calculation (8/58 (14%)) with the work-related study objective; attribution of WP to overall health (28/58 (48%)); accounting for skewness of presenteeism/sick leave (10/52 (19%)); accounting for work-related contextual factors (25/58 (43%)); reporting attrition and its reasons (1/58 (2%)); reporting both aggregated results and proportions of individuals reaching predefined meaningful change or state (11/58 (16%)). SLRs in other chronic diseases confirmed heterogeneity and methodological flaws identified in IA studies without identifying new issues.

Conclusion

High methodological heterogeneity was observed in studies with WP as outcome domain. Consensus around various methodological aspects specific to WP studies is needed to improve quality of future studies. This review informs the EULAR Points to Consider for conducting and reporting studies with WP as an outcome in IA.

Keywords: arthritis, outcome assessment, health care, arthritis, psoriatic, arthritis, rheumatoid, spondylitis, ankylosing

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Inflammatory arthritis (IA) has substantial impact on work participation (WP).

Previous systematic literature reviews of studies with WP as an outcome documented deficiencies in the study design, analysis and reporting of results, hampering interpretation, comparison and meta-analysis.

What does this study add?

This study provides a synthesis of the methodological choices and issues in studies with WP as an outcome domain in IA and in other chronic diseases.

Methodological heterogeneity and flaws were identified across four key areas of potential concern: (1) study design, (2) outcome domains and measurement instruments, (3) data analysis and (4) reporting of results.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

This study aims to inform the efforts to improve the methodological quality and homogeneity of future studies with WP as an outcome domain, and ultimately contribute to high-quality evidence on interventions to support endurable WP.

This review informs the EULAR Points to Consider when designing, analysing and reporting studies with WP as an outcome domain in IA.

Introduction

Inflammatory arthritis (IA) encompasses a group of chronic diseases typically affecting adults in working age, and often leading to work disability with consequent loss of income for patients and high social expenditures for society.1 The treatment of IA aims at reaching remission or, at least, low disease activity in order to prevent structural damage and improve patients’ quality of life. Despite the proven efficacy of new therapies such as biologic (b) and targeted synthetic (ts) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), the burden of restricted participation in work remains high.

People living with IA have identified the ability to maintain a job and being productive while at work as a priority, ranked right after suppressing pain and improving physical function.2 Work participation (WP) is defined as an active engagement in the role of worker.3 In addition to the employment status (being employed or not), restrictions in work participation can be quantified using absenteeism (namely sick leave) and presenteeism.4 Absenteeism refers to the time missed from work due to health reasons and presenteeism refers to experienced restrictions or impaired productivity while at work due to health reasons.4 People can transition back and forth between not working, working with difficulty and working without difficulty.5

To ensure effective interventions to support endurable WP, high-quality evidence is required. However, several systematic literature reviews in IA showed inconclusive results that could be partially attributed to methodological issues in the study design, analysis and reporting of results hampering correct interpretation, comparison and meta-analysis of studies.6 7

WP is increasingly seen as an important outcome of interventions and thus as a target for improvement. During the past decade, the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) Productivity Working Group focused its work on evaluating and improving the validity of outcomes and outcome measurement instruments of WP.4 8–10 Despite its continuous efforts to harmonise measurement of worker productivity loss across studies, valid instruments are not sufficient to ensure high-quality clinical studies.

The primary aim of this systematic literature review (SLR) was to inform the EULAR task force working on ‘points to consider when designing, analysing and reporting studies with WP as an outcome domain among patients with IA’. The specific objectives of the present work were (1) to summarise the methodological choices in studies with WP as an outcome domain in IA and (2) to identify the methodological issues reported in SLRs of studies with WP as an outcome domain in other chronic diseases.

Methods

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

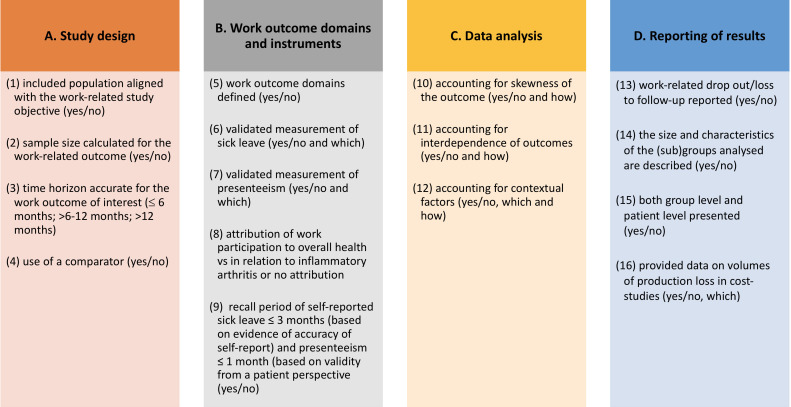

EULAR task force working on ‘points to consider when designing, analysing and reporting studies with WP as an outcome domain among patients with IA’ outlined the scope of the literature search and pre-identified 24 topics in seven main areas of potential concern: (1) study design, (2) outcome domains, (3) outcome measurement instruments, (4) contextual factors, (5) data analysis, (6) reporting of results and (7) estimating productivity costs. These topics were based on (a) knowledge of the literature and experience with conducting such studies and (b) potential role of the issues on bias (selection, information and statistical bias). After a careful evaluation of the seven pre-defined areas and 24 topics, and to avoid redundancy, they were grouped in four main areas (study design, work outcome domains and instruments, data analysis and reporting of results) and 16 topics (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representation of the 16 pre-defined topics (1 to 16) grouped by the four main methodological areas (A to D).

For topics 3 and 9, some context is needed. The follow-up time for outcome assessment should be sufficient to capture changes in the work outcome of interest (topic 3). While for presenteeism and sick leave responsiveness was demonstrated at 24 weeks of follow-up,11 for work status, a follow-up of at least 1 year is preferred. In fact, changes in work status can only be detected over shorter follow-up periods of ≤6 months if large sample sizes are used. Work status change and, more precisely, transitions between employment and unemployment can be seen as formally the last step in a sequence of events that start with presenteeism and/or absenteeism.12 On the other hand, regarding the recall of the assessment instrument (topic 9), there is evidence that a recall period beyond 3 months for sick leave becomes inaccurate8 13 and that patients prefer a recall of 1 week for presenteeism (with maximal accuracy for a 4-week recall).14

Two searches were conducted according to the PICOT (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Time of follow-up) framework—details are provided in online supplemental figure S1. Search 1 focused on studies with WP as outcome domain in IA, aiming at critically appraising methodological choices and heterogeneity across studies, and search 2 on SLRs of studies with WP as outcome domain in other chronic diseases, aiming to identify whether our pre-identified methodological issues in studies in IA were also recognised in other chronic diseases and/or new aspects were revealed.

rmdopen-2020-001522supp001.pdf (411.3KB, pdf)

For search 1, the following study designs were included: randomised controlled trials (RCTs), controlled clinical trials and prospective observational studies (including registries). Also, studies in IA assessing costs of changes in work participation were identified and included in order to assess whether volumes of work productivity (eg, days, hours) were reported as a separate step before converting volumes into costs.15 Other specific methodological aspects related to this particular type of study were considered beyond the scope for the current review. Exclusion criteria for both searches are provided in online supplemental text S1.

The search strategies were designed by an experienced librarian (LF). MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library were searched (details on search strategies in online supplemental text S2 and S3) between January 2009 and May 2019.

Study selection and data extraction

For both searches, references and abstracts were imported into the reference management software EndNote V.X7.0.2 and deduplicated.

As a high number of hits resulted from the initially defined broad timeframe (n=7715), it was decided to limit the review to recent studies published from January 2014 to April 2019 (n=5534). This decision was based on feasibility and with the rationale that the most recent studies would likely be of better methodological quality and better reflect current standards.

Two researchers (MLM and MMtW) independently screened all titles and abstracts. Next, full texts were reviewed to determine eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and if necessary, the methodologists (SR and PP) were involved to make a final decision.

For both searches, study details and results of eligible studies were retrieved by two reviewers (MLM and AA) using a standardised data extraction sheet. Both reviewers (MLM and AA) retrieved data from a 20% random selection of all the included studies. Given an agreement of 89% and consensus on how to further avoid divergences in data extraction, reviewers continued to independently retrieve data of the remaining studies.

For studies in IA, general characteristics of the studies were first retrieved, such as the type of study (RCTs vs longitudinal observational studies), type of intervention (pharmacological intervention, non-pharmacological intervention and natural course of the disease), assessed WP outcome domain (work status and/or sick leave and/or presenteeism) and also if the WP outcome domain was assessed as primary or secondary outcome (online supplemental table S1). Then, the methodological choices regarding the 16 pre-defined topics (figure 1) were retrieved by area: study design (table 1), work outcome domains and instruments (table 2), data analysis (table 3) and reporting of results (table 4).

Table 1.

Methodological choices in the area of ‘study design’

| Topics | Results from studies in inflammatory arthritis (n=58) | Aspects identified by authors of SLRs in other chronic diseases (n=24) | ||

| n/N (%) | Detailed information | n* (%) | Comments | |

| 1. The included population aligned with the work-related study objective | 16/58 (28%) | The included population specifically aligned with the work-related study objective in 16/58 (28%) studies (16/28 (57%) studies with work as primary outcome)†—n/N§:

|

3 (12%) 3 (12%) 3 (12%) |

Lack of clarity on the recruitment procedure98 115 120 Study population not representative100 114 120 Study population too heterogeneous114 115 119 |

| 2. Sample size calculated for the work-related outcome | 8/58 (14%) | The sample size for the work-related outcome was calculated in eight studies (8/28 (29%) studies with work as primary outcome)†—n/N§:

|

3 (12%) 4 (17%) 21 (87%) |

No sample size calculation in included studies115–117 Study population too small99 100 103 114 No mention to the sample size calculation (if performed or not by included studies)97–114 118–120 |

| 3. Time horizon accurate for the work outcome of interest | 56/58 (97%) | The time-horizon aligned with the work outcome domain of interest in 57/58 (98%) studies—n/N§:

Work status‡: 2/17 (12%)21 52 Sick leave and/or presenteeism: 13/52 (25%)19 28 31 32 35 37 43 48 52 54 58 67 71

Work status‡: 5/17 (29%)21 30 36 42 51 Sick leave and/or presenteeism: 13/52 (25%)18 20 21 36 38 42 51 55 56 61 63 64 68 |

2 (8%) 3 (12%) 4 (14%) |

Follow-up was reported as: Highly heterogeneous across studies97 114 Too short to assess work outcomes111 117 120 Not done/not described106 108 114 115 |

| Topics | Results from studies in inflammatory arthritis (n=58) | Aspects identified by authors of SLRs in other chronic diseases (n=24) | ||

| n/N (%) | Detailed information | n* (%) | Comments | |

| 3. Time horizon accurate for the work outcome of interest (continuation) |

Sick leave and/or presenteeism: 26/52 (51%)16 17 22 24–27 29 33 34 39 44–47 49 50 53 59 60 62 65 66 69 72 73 |

|||

| 4. Use of a comparator | 26/58 (47%) | A comparator was used in 26/58 studies (47%)—n/N§:

|

3 (12%) 1 (4%) |

Most studies lacked a control group97 102 114 Unmatched control groups114 |

*Number of systematic literature reviews reporting on the corresponding topic.

†7/28 (25%) studies with work as primary outcome included unselected patients from registries.

‡Emery et al (2016) have two different time horizons because this is a post hoc analyses of two trials: time horizon of 26 and 24 weeks for the Optimal Protocol for Treatment Initiation with Methotrexate and Adalimumab (OPTIMA) and PRevention Of Work Disability (PROWD) trials, respectively.

§The denominator may vary according to the type of intervention, work outcome of interest or type of study.

n/N, number of original studies in which the methodological choice was identified/number of studies in which the topic was possible to assess; OBS, observational longitudinal study; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Table 2.

Methodological choices in the area of ‘work outcome domains and instruments’

| Topics | Results from studies in inflammatory arthritis (n=58) | Aspects identified by authors of SLRs in other chronic diseases (n=24) | ||

| n/N* (%) | Detailed information | n† (%) | Comments | |

| 5. Work outcome domains defined | 52/58 (90%) | The work outcomes domain was defined in 51 studies—n/N* (%):

|

13 (54%) | High variability in the definition of a work outcome in included studies precluding data pooling/meta-analysis97–99 102 105–107 109 111 113 114 117 120 |

| 6. Validated measurement of sick leave | 42‡/46 (91%) | Of the studies that had sick leave as work outcome domain, 42 used validated instruments to assess it, n/N (%):

|

Not reported | – |

| 7. Validated measurement of presenteeism | 35‡/40 (88%) | Of the studies that had presenteeism as work outcome domain, 35 used validated and OMERACT endorsed instruments, n/N* (%):

|

1 (4%) 1 (4%) |

WPAI used only in a small number of studies119 Studies use qualitative, quantitative and economic non-standardised measures of work productivity119 |

| 8. Attribution of work participation to overall health | 29/58 (50%) | The work outcome domain was assessed in relation to overall health (and not in relation to IA) in 46 studies, n/N* (%):

|

Not reported | – |

| Topics | Results from studies in inflammatory arthritis (n=58) | Aspects identified by authors of SLRs in other chronic diseases (n=24) | ||

| n/N* (%) | Detailed information | n/N* (%) | ||

| 9. Recall period of self-reported sick leave and presenteeism | 35/42 (82%) | The recall period of self-reported sick leave was ≤3 months in 34/37 (92%) studies (excluding registries as recall is not applicable)18–21 24–26 31–39 42 43 50–56 58–60 63 67–69 71 73 The recall period of self-reported presenteeism was of 7 days to 1 month in 34/40 (85%) studies18–21 24–26 31–39 42 43 50–56 58 60 62 63 67–69 71 73 |

1 (4%) 2 (8%) |

Inconsistency of the recall period103 No accounting for a possible recall bias102 115 |

*The denominator may vary according to the corresponding assessed topic.

†Number of systematic literature reviews reporting on the corresponding topic.

‡Boer et al (2018) used both WPAI-RA and WPS-RA.

IA, inflammatory arthritis; n/N, number of original studies in which the methodological choice was identified/number of studies in which the topic was possible to assess; WALS, Workplace Activity Limitations Scale; WLQ-25, Work Limitations Questionnaire 25-item; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment; WPS, Work Productivity Questionnaire.

Table 3.

Methodological choices in the area of ‘data analysis’

| Topics | Results from studies in inflammatory arthritis (n=58) | Aspects identified by authors of SLRs in other chronic diseases (n=24) | ||

| n/N* (%) | Detailed information | N† (%) | Comments | |

| 10. Accounting for skewness of the outcome | 10/‡52 (19%) |

Sick leave is reported as positively skewed (zero-inflated) in 10/46 (22%) studies. The authors accounted for skewness by:

Presenteeism was reported as zero-inflated in 1/40 (3%) study. The authors accounted for skewness by using zero-inflated models‡; 1/1 (100%)58 |

Not reported | – |

| 11. Accounting for interdependence of outcomes | 49/52§ (94%) |

Interdependence was accounted for in 49 studies by—n/N*:

|

Not reported | – |

| 12. Accounting for contextual factors | 25/58 (43%) |

Contextual factors were accounted for in 8/22 (36%) RCTs and 17/36 (47%) OBS—n/N*:

Personal factors: sociodemographics (7/8 RCTs,19 25 36 37 49 67 69 88% and 15/17 OBS,16 20 27 41 44 46 50 56–58 61 65 66 70 72 88%) Work-related factors: workplace support (1/17 OBS50, 6%), nature of work (4/17 OBS,27 41 58 70 24%)

Personal factors: sociodemographics (1/8 RCT,52 13% and 2/17 OBS,23 63 12%) Work-related factors: nature of work (1/17 OBS,63 6%) |

12 (50%) | Adjustment for contextual/confounder factors in the included studies, if any, is performed only for very few factors 101 105 107 109 110 112–117 120 |

*The denominator may vary according to the topic assessed.

†Number of systematic literature reviews in other chronic diseases in which the authors report on the corresponding topic.

‡Tillet et al (2017) accounted for skewness of both sick leave and presenteeism.

§Studies addressing work status only were excluded from the denominator as interdependence between work outcome domains does not apply to them.

¶Different contextual factors may have been accounted for in the same study.

n/N, number of original studies in which the methodological choice was identified/number of studies in which the topic was possible to assess; OBS, observational longitudinal study; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Table 4.

Methodological choices in the area of ‘reporting of results’

| Topics | Results from studies in inflammatory arthritis (n=58) | Aspects identified by authors of SLRs in other chronic diseases (n=24) | ||

| N/N* (%) | Detailed information | N† (%) | Comments | |

| 13. Work-related drop-out/loss to follow-up reported | 1/58 (2%) |

Reported loss to follow-up and work-related reasons for drop-out50 | 2 (8%) | Attrition and its reasons are inconsistently reported: described as well reported in 1 SLR118and inadequately reported in the other112 |

| 14. The size and characteristics of the (sub)groups analysed are described | 58/58 (100%) | All studies reported the size and characteristics of the analysed (sub)groups16–73 | 1 (4%) | No subgroup analysis is performed in included studies104 |

| 15. Group level and patient level presented | 11/58 (19%) | Presented both aggregated results (group level) and percentages according to meaningful thresholds (patient level)19 30 35 42 51 56 59 62 65 66 71 | 1 (4%) | Lack of patient-level data precluded meta-analysis104 |

| 16. Volumes of production loss reported in cost studies | 21/24‡ (88%) | Of the studies reporting productivity costs, 88% provided data on natural volumes (days/hours) used to calculate costs16 74–76 78–82 84–92 94–96 | Not reported | – |

*The denominator may vary according to the topic assessed.

†Number of systematic literature reviews in other chronic diseases in which the authors report on the corresponding topic.

‡The denominator corresponds to the studies reporting productivity costs.

n/N, number of original studies in which the methodological choice was identified/number of studies in which the topic was possible to assess.

For SLRs in other chronic diseases, all the methodological issues, as reported by the authors of the SLRs, were retrieved and categorised into the 16 pre-defined topics (figure 1). The quality of the SLRs was not assessed as we were interested in reviewing which methodological flaws were reported in other chronic diseases, particularly focusing on new aspects not previously identified in IA studies. Both SLRs were registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020186798).

Results

For the SLR in IA, the literature search yielded 7715 hits. After removing duplicates, conference abstracts and publications before 2014, 2427 articles remained for screening of titles and abstracts, leading to screening of 132 full-text articles. Twenty-three studies on costs of WP were cross-sectional or retrospective and therefore did not comply with inclusion criteria to assess general methodological choices. A total of 81 studies were included in our analysis (flowchart in online supplemental figure S2): 58 for extraction of general methodological choices,16–73 23 for outcome reporting studies on costs of work productivity16 74–96 and one providing information on both outcomes.16

The search for SLRs in other chronic diseases yielded 10 208 hits. After excluding duplicates and studies before 2014, 3547 titles and abstracts were screened, resulting in screening of 148 full-text articles, and finally 24 were included in the analysis (flowchart in online supplemental figure S3).97–120

General characteristics of the included studies

The 58 IA studies appraising general methodological issues comprised 46 longitudinal observational studies16 17 20 23 26 27 29–31 33 34 39–47 50 51 55–59 61 63 65 66 68 70–73 and 22 RCTs.18 19 21 22 24 25 28 32 35–38 48 49 52–54 60 62 64 67 69 The characteristics of included studies are provided in online supplemental table S1.

Most of the IA studies were on rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (n=33, 57%),16 17 21–24 27–29 31–34 36 37 39–41 44–47 49 52–54 56 57 61 64 68 69 72 followed by axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) (n=16, 28%)18 19 30 38 50 51 59 60 62 63 65–67 70 71 73 and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) (n=6, 10%),25 35 43 48 55 58 and finally, two studies assessed two diagnostic groups: RA and axSpA,42 and axSpA and PsA.26

The type of intervention and WP outcome domain for each study is presented in online supplemental table S1, and the corresponding data grouped by type of study (RCTs vs longitudinal observational studies) is shown in online supplemental table S2. Work was assessed as a primary outcome in only 26/58 (45%) of the studies,16 17 21 23 26 27 29–31 41 42 44–47 50 56–58 61 63 64 66 68 71 rarely being the primary outcome in RCTs (n=2/22, 9%).21 64 The time horizon for the assessment of WP outcomes varied from 24 weeks to 12 years and its distribution, as well as the frequency of assessment by work outcome domain, are both provided in online supplemental table S3.

The general characteristics of included SLRs are presented in online supplemental table S4. Most studies focused on cancer (n=15; 63%),98 99 101 105–109 111 112 115 116 118–120 followed by stroke (n=3, 13%).97 113 117 The most frequently assessed work outcome was ‘return to work after a temporary absence’ (n=12, 50%).97 99 101 107–110 113 115–117 120

Study design

Table 1 provides an overview of methodological choices in the area of study design. The included population was aligned with the specific work-related study objective in only 16/58 (28%) IA studies,21–23 26 27 30 31 43–46 50 61 63 64 66 while the sample size calculation was performed solely in 8 (14%) studies.21 30 42 44 56 58 64 68

Large heterogeneity was observed in the follow-up time of the IA studies, although the majority of studies assessed changes in work status within a follow-up of >6 months. Of the five studies assessing changes in work status over an unrealistic short follow-up period ≤6 months,21 30 52 53 67 two also assessed it after 12 months (online supplemental table S3).30 53

The frequency of assessment of sick leave in observational studies (excluding registries, n=8) was longer than 3 months in more than half of the studies (12/20 (60%))20 26 33 34 39 42 50 51 59 63 66 72; however, the other 8/20 (40%) had a frequency of assessment shorter than 3 months hampering correct aggregation into cumulative sick leave.31 43 55 56 58 68 71 73

While all RCTs had a comparator,18 19 21 22 24 25 28 32 35–38 48 49 52–54 60 62 64 67 69 only 8/36 (22%) observational studies had one.27 29 30 42 46 51 70 71

The general population, a meaningful benchmark in studies with work as an outcome, was used as a comparator solely in five observational studies.27 29 30 46 70

Regarding SLRs in other chronic diseases, similar issues were reported for all the topics of study design, with the most common flaw being no mentioning of the sample size calculation for work as outcome, as reported in 21/24 (87%) SLRs.97–114 118–120

Work outcome domains and instruments

The methodological choices regarding the work outcome domains and instruments are presented in table 2. Among studies in IA, the definition of ‘work status’ was described in two-thirds of studies (71%)21 23 27 30 40 41 46 50 53 57 62 70 and definitions showed large heterogeneity. Sick leave was defined in all studies assessing it,16 18–22 24–27 29 31–39 42–47 49–56 58–60 63 65–69 71–73 and all but one reported the definition of presenteeism.30

SLRs in other chronic diseases reported high variability in the definition of all WP outcomes in included studies precluding meta-analysis.97–99 102 105–107 109 111 113 114 117 120 In contrast, the majority of studies in IA assessed sick leave and presenteeism using validated instruments—91% and 88% of studies, respectively. The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire was the outcome measurement instrument most frequently used (n=29).18–21 24–26 31–34 36–39 42 43 50–53 55 56 58 63 67 69 71 73

Overall, the work outcome domains’ attribution (to overall health, arthritis or no attribution) was heterogeneous across studies, with sick leave being the domain most frequently assessed in relation to overall health (23/46 (50%) studies).16 18 20 22 25 27 29 31 33 34 38 42 44–47 49 51 55 58 65 67 72

Reviews in other chronic diseases pointed out inconsistencies of the recall period (varying from 7 days to 7 years).102 103 115 On the contrary, in IA, the recall period of sick leave (excluding registries since recall is not applicable) was accurate8 13 (ie, ≤3 months—figure 1) in 34/37 (92%) studies,18–21 24–26 31–39 42 43 50–56 58–60 63 67–69 71 73 and the recall of presenteeism was reliable and in line with the face validity for patients14 (ie, between 7 days and 4 weeks—figure 1) in 34/40 studies (85%).18–21 24–26 31–39 42 43 50–56 58 60 62 63 67–69 71 73

Data analysis

Regarding the methodological choices in the area of data analysis (table 3), only 10/53 (19%) IA studies reported skewness of sick leave and/or presenteeism and accounted for the skewness in the analyses.20 22 45–47 50 58 59 63 65

Also, only 8/22 (36%) RCTS19 25 36 37 49 52 67 69 and 17/36 (47%) observational studies16 20 23 27 41 44 46 50 56–58 61 63 65 66 70 72 took contextual factors into account, most frequently demographic factors, such as age and gender, while other specific work-related contextual factors (eg, nature of work and workplace support) were less frequently accounted for.27 41 50 58 63 70 SLRs in other chronic diseases reported that adjustment for contextual factors/confounders in the included studies, if any, was performed for very few factors.101 105 107 109 110 112–117 120

The majority of studies in IA (n=49/52, 94%) took interdependence between work outcomes into account acknowledging that (1) data (over time) on sick leave are less meaningful without information on the proportion of persons employed (over time) in that specific population (sick leave cannot happen if the person is not employed) and/or (2) assessing presenteeism is less meaningful if information on sick leave is not provided (eg, presenteeism cannot happen on days a person is absent due to sick leave).18–22 24–27 29 31–39 42–47 50–56 58–60 62–69 71 73

Reporting of results

The methodological choices in IA studies as well as the issues raised in SLRs in other chronic diseases regarding the area of reporting are described in table 4.

The reporting loss to follow-up and the work-related reasons for drop-out were often neglected in IA studies, being reported in only one study.50 In other chronic diseases, this was also inconsistently reported.112 118

All IA studies reported the size and characteristics of the (sub)groups analysed.16–73

In IA studies, the choice on how to report study findings was heterogeneous, with only 11/58 (16%) studies presenting both aggregated results (mean/median) and percentages according to meaningful thresholds.19 30 35 42 51 56 59 62 65 66 71 This was also outlined by the SLRs in other chronic diseases where the lack of patient-level data was a barrier to study pooling and meta-analysis.104

Data on natural volumes (days/hours) used to calculate costs was presented in the majority of the studies reporting productivity costs (21/24, 88%).16 74–76 78–82 84–92 94–96

Discussion

WP has been a frequently assessed endpoint in IA studies over the past 5 years; however, these studies revealed a high methodological heterogeneity and a number of important flaws. Several issues were detected in the areas of study design, work outcome definition and assessment, as well as in the analysis and reporting of the results. Review of SLRs in other chronic diseases revealed that observed methodological issues are not rheumatology specific as these are also common in studies of work outcomes in other clinical fields.

Different WP outcomes of interest apply to specific subpopulations (eg, employed/employable people) and need to be assessed in a sufficiently large group over a certain timeframe.4 Notwithstanding, this was often neglected, particularly when WP was not the primary outcome as occurred in the majority of RCTs. Thus, the studied population, the intermediate assessment time-points and overall follow-up time were tailored on the primary outcomes, hampering the power to detect statistically significant effects on WP outcomes and leading to follow-up times not adequate for some of the WP outcomes of interest. Moreover, even in RCTs with long-term extensions, WP outcome domains were not assessed across the extension study period as other outcomes. This pose particular challenges in studies aiming to understand the impact of an intervention on long-term employment, work disability or prolonged sick leave (eg, assessing costs of productivity loss), as having a time horizon of 6 months is not adequate.8 Remarkably, also studies with WP as the primary outcome had important flaws in this area, for example, the sample size calculation was often not reported.

Careful choice of which WP outcome to assess and which measurement instrument to use is of paramount importance, particularly when dealing with a comparison of interventions.8 9 As far as the definition of employment and work disability is concerned, clinical studies might want to align with definitions that are relevant for their administrative entities (eg, countries, regions, states, etc),8 thus likely contributing to heterogeneity in work status definitions as found in IA studies. In contrast, presenteeism and sick leave were often described in line with the frequent use of validated instruments (eg, WPAI) that include an appropriate definition for the work outcome domain.8 In this regard, stakeholders should strive to harmonise worldwide comparable and locally applicable definitions along with endorsing specific outcome measurement instruments, for example, as OMERACT is doing for presenteeism.8 9 Two other important methodological aspects, namely, disease attribution and recall, are relevant but not (yet) encompassed by the OMERACT framework. Regarding disease attribution, only half of the studies assessed the WP outcome domain in relation to overall health (more meaningful for benchmarking with the general population). This may be problematic since it is well established that patients have difficulties in distinguishing which restrictions can be attributable to IA, other specific health problems (eg, osteoarthritis) or overall health.5 Inconsistency of the recall period was often reported in studies of other chronic diseases, however less evident in IA studies. This is likely due to the widespread use of validated instruments such as WPAI (past 7 days recall) and the Work Productivity Survey (WPS; past month recall) in the field of rheumatology.

WP, as any outcome, is subject to the effect of a number of variables, related to either the disease, the social environment or other aspects, which require to be considered in order to reliably assess the net change of the outcome. Contextual factors, defined by OMERACT, from a statistical viewpoint, as a “variable that is not an outcome of the study but needs to be recognized (and measured) to understand the study results”, include potential confounders and effect modifiers (https://omeract.org/handbook-resources/). The characterisation of core contextual factors (ie, when do they really matter to influence practice) remains a challenge, partially because the influence of most contextual factors tends to vary according to the setting.8 The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) provided, in addition to the bio-psycho-social framework, also a classification distinguishing personal and environmental factors, and this was the basis for a further grouping of contextual factors relevant for WP by the OMERACT work productivity group.10 Lack of accounting for contextual factors was common in IA and often reported also by SLRs in other chronic disease. Work-related contextual factors such as job type, adaptations at work and more personal aspects such as ability to cope and satisfaction were often neglected. This emphasises the urgent need of action for improving and implementing feasible strategies to account for relevant work-related contextual factors.

Other methodological issues pertain to how data are analysed and reported. WP presents a continuum of subdomains which are (hierarchically) dependent on each other and/or can compete over time.5 The majority of studies assessing sick leave and presenteeism took interdependence between work outcomes into account, encompassing the widespread use of the WPAI, which already considers interdependence of sick leave and presenteeism (overall work impairment). SLRs in other chronic diseases reported that despite using the correct instrument (eg, WPAI), the studies frequently neglected some important subdomains.119 Indeed, to account for interdependence, WPAI must be comprehensively used, that is, assessing both presenteeism and sick leave plus the overall work impairment. Yet, consensus is needed on how to deal with such dependencies when instruments other than WPAI are used. It is known that distribution of presenteeism, and especially sick leave, may often be highly skewed (even zero inflated).6 7 Not accounting for this, as we observed in the majority of studies, may affect the robustness of conclusions.

Furthermore, drop-out may be related to underlying work context and thus not be at random, so the rates and reason for drop-out should be carefully considered to ensure a correct interpretation of the impact of IA on WP outcomes overtime. However, these were not reported in the majority of studies. Likewise, to enhance the insight into WP outcomes and to ensure more transparent interpretation of the differences between interventions, the mean and median values of sick leave or presenteeism and also the proportion of patients attaining a specific meaningful (change in) outcome are advisable to report.8 In IA studies, the choice on how to report data on work outcome domains was heterogeneous, with only 19% of studies presenting both aggregated results and percentages according to meaningful thresholds. Choice of thresholds was not uniform across studies, highlighting the needs for consensus in this respect.

This review has some limitations. Although we used a sensitive approach to identify studies with WP as an outcome domain in IA as well as SLRs in other chronic diseases, we cannot be sure that some relevant studies were missed. While retrieving data from SLRs in other chronic diseases, only the reported issues were collected, as going through the primary studies was beyond the scope. This may have resulted in missing some relevant methodological aspects not captured by the SLR authors. The exclusion of studies <2014 due to feasibility reasons implies that our summary is generalisable to issues found in recent studies.

In conclusion, a high methodological heterogeneity and important flaws were detected among the included studies in the main areas of study design, work outcome definition and assessment, analysis and reporting of results. This SLR alerts for the need of implementation of minimum quality standards around these key methodological aspects to homogenise and improve the quality of future studies in IA and likely in other chronic diseases. This review informs the EULAR Points to Consider for the conduction, analysis and reporting of studies with work as an outcome domain in IA.

Acknowledgments

All EULAR task force members working on ‘points to consider when designing, analysing and reporting studies with WP as an outcome domain among patients with IA’ for defining the main focus of the literature search. The work on this manuscript was previously accepted as a conference abstract to the EULAR Congress 2020 and published in the correspondent supplement of Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Footnotes

MLM and AA contributed equally.

SR and PP contributed equally.

Contributors: All coauthors contributed to the development of the study design and outline. LF has developed and run the library searches. MLM and MMtW screened all titles and abstracts and reviewed the full texts for inclusion. MLM and AA retrieved data using standardised data extraction sheets. MLM, AA, SR, PP and AB have analysed and synthesised the data. MLM and AA have drafted the first version of the manuscript, and all authors have critically reviewed and agreed with the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study is part of the EULAR ‘points to consider when designing, analysing and reporting studies with WP as an outcome domain among patients with IA’ funded by EULAR, grant number EPI021.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

References

- 1.Lacaille D, Hogg RS. The effect of arthritis on working life expectancy. J Rheumatol 2001;28:2315–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lacaille D, White MA, Backman CL, et al. . Problems faced at work due to inflammatory arthritis: new insights gained from understanding patients’ perspective. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:1269–79. 10.1002/art.23002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandqvist JL, Henriksson CM. Work functioning: a conceptual framework. Work 2004;23:147–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escorpizo R, Bombardier C, Boonen A, et al. . Worker productivity outcome measures in arthritis. J Rheumatol 2007;34:1372 LP–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verstappen SMM Rheumatoid arthritis and work: the impact of rheumatoid arthritis on absenteeism and presenteeism. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2015;29:495–511. 10.1016/j.berh.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Burg LRA, Ter Wee MM, Boonen A. Effect of biological therapy on work participation in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1924–33. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ter Wee MM, Lems WF, Usan H, et al. . The effect of biological agents on work participation in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:161–71. 10.1136/ard.2011.154583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verstappen SMM, Lacaille D, Boonen A, et al. . Considerations for evaluating and recommending worker productivity outcome measures: an update from the OMERACT Worker Productivity Group. J Rheumatol 2019;46:1401–5. 10.3899/jrheum.181201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaton DE, Dyer S, Boonen A, et al. . OMERACT filter evidence supporting the measurement of at-work productivity loss as an outcome measure in rheumatology research. J Rheumatol 2016;43:214–22. 10.3899/jrheum.141077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang K, Escorpizo R, Beaton DE, et al. . Measuring the impact of arthritis on worker productivity: perspectives, methodologic issues, and contextual factors. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1776–90. 10.3899/jrheum.110405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang K, Beaton DE, Boonen A, et al. . Measures of work disability and productivity: Rheumatoid Arthritis Specific Work Productivity Survey (WPS-RA), Workplace Activity Limitations Scale (WALS), Work Instability Scale for Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA-WIS), Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ), and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI). Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:S337–49. 10.1002/acr.20633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergström G, Bodin L, Hagberg J, et al. . Sickness presenteeism today, sickness absenteeism tomorrow? A prospective study on sickness presenteeism and future sickness absenteeism. J Occup Environ Med 2009;51:629–38. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181a8281b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Severens JL, Mulder J, Laheij RJF, et al. . Precision and accuracy in measuring absence from work as a basis for calculating productivity costs in the Netherlands. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:243–9. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00452-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leggett S, van der Zee-Neuen A, Boonen A, et al. . Content validity of global measures for at-work productivity in patients with rheumatic diseases: an international qualitative study. Rheumatology 2016;55:1364–73. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. . Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA 2016;316:1093–103. 10.1001/jama.2016.12195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alemao E, Guo Z, Frits ML, et al. . Association of anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibodies, erosions, and rheumatoid factor with disease activity and work productivity: a patient registry study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018;47:630–8. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnabe C, Sun Y, Boire G, et al. . Heterogeneous disease trajectories explain variable radiographic, function and quality of life outcomes in the Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort (CATCH). PLoS One 2015;10:e0135327. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deodhar AA, Dougados M, Baeten DL, et al. . Effect of secukinumab on patient-reported outcomes in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: a phase III randomized trial (measure 1). Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2901–10. 10.1002/art.39805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dougados M, Tsai W-C, Saaibi DL, et al. . Evaluation of health outcomes with etanercept treatment in patients with early nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. J Rheumatol 2015;42:1835–41. 10.3899/jrheum.141313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Druce KL, Aikman L, Dilleen M, et al. . Fatigue independently predicts different work disability dimensions in etanercept-treated rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis patients. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:1–9. 10.1186/s13075-018-1598-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emery P, Smolen JS, Ganguli A, et al. . Effect of adalimumab on the work-related outcomes scores in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. Rheumatology 2016;55:1458–65. 10.1093/rheumatology/kew056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eriksson JK, Wallman JK, Miller H, et al. . Infliximab versus conventional combination treatment and seven‐year work loss in early rheumatoid arthritis: results of a randomized Swedish trial. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:1758–66. 10.1002/acr.22899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espersen R, Jensen V, Berg Johansen M, et al. . The impact of diagnosis on job retention: a Danish registry-based cohort study. Rehabil Res Pract 2015;2015:1–7. 10.1155/2015/795980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleischmann R, Weinblatt ME, Schiff M, et al. . Patient‐reported outcomes from a two‐year head‐to‐head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept and adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:907–13. 10.1002/acr.22763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottlieb AB, Strand V, Kishimoto M, et al. . Ixekizumab improves patient-reported outcomes up to 52 weeks in bDMARD-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis (SPIRIT-P1). Rheumatol 2018;57:1777–88. 10.1093/rheumatology/key161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haglund E, Petersson IF, Bremander A, et al. . Predictors of presenteeism and activity impairment outside work in patients with spondyloarthritis. J Occup Rehabil 2015;25:288–95. 10.1007/s10926-014-9537-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen SM, Hetland ML, Pedersen J, et al. . Work ability in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a register study on the prospective risk of exclusion and probability of returning to work. Rheumatology 2017;56:1135–43. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bingham CO, Weinblatt M, Han C, et al. . The effect of intravenous golimumab on health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: 24-week results of the phase III GO-FURTHER trial. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1067–76. 10.3899/jrheum.130864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen SM, Hetland ML, Pedersen J, et al. . Effect of rheumatoid arthritis on longterm sickness absence in 1994–2011: a Danish cohort study. J Rheumatol 2016;43:707–15. 10.3899/jrheum.150801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He C, He X, Tong W, et al. . The effect of total hip replacement on employment in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:2975–81. 10.1007/s10067-016-3431-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hussain W, Janoudi N, Noorwali A, et al. . Effect of adalimumab on work ability assessed in rheumatoid arthritis disease patients in Saudi Arabia (AWARDS). Open Rheumatol J 2015;9:46–50. 10.2174/1874312901409010046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaeley GS, MacCarter DK, Goyal JR, et al. . Similar improvements in patient-reported outcomes among rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with two different doses of methotrexate in combination with adalimumab: results from the MUSICA trial. Rheumatol Ther 2018;5:123–34. 10.1007/s40744-018-0105-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karpouzas GA, Ramadan SN, Cost CE, et al. . Discordant patient–physician assessments of disease activity and its persistence adversely impact quality of life and work productivity in US Hispanics with rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open 2017;3:e000551–9. 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karpouzas GA, Strand V, Ormseth SR. Latent profile analysis approach to the relationship between patient and physician global assessments of rheumatoid arthritis activity. RMD Open 2018;4:e000695–10. 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kavanaugh A, Gladman D, van der Heijde D, et al. . Improvements in productivity at paid work and within the household, and increased participation in daily activities after 24 weeks of certolizumab pegol treatment of patients with psoriatic arthritis: results of a phase 3 double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:44–51. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keystone EC, Taylor PC, Tanaka Y, et al. . Patient-reported outcomes from a phase 3 study of baricitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis: secondary analyses from the RA-BEAM study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1853–61. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Machado DA, Guzman RM, Xavier RM, et al. . Open-label observation of addition of etanercept versus a conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug in subjects with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy in the Latin American region. J Clin Rheumatol 2014;20:25–33. 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maksymowych WP, Dougados M, van der Heijde D, et al. . Clinical and MRI responses to etanercept in early non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: 48-week results from the EMBARK study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1328–35. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boer AC, Boonen A, van der Helm van Mil AHM. Is anti-citrullinated protein antibody-positive rheumatoid arthritis still a more severe disease than anti-citrullinated protein antibody-negative rheumatoid arthritis? A longitudinal cohort study in rheumatoid arthritis patients diagnosed from 2000 onward. Arthritis Care Res 2018;70:987–96. 10.1002/acr.23497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manders SHM, Kievit W, Braakman-Jansen ALMA, et al. . Determinants associated with work participation in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis taking tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1263–9. 10.3899/jrheum.130878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McWilliams DF, Varughese S, Young A, et al. . Work disability and state benefit claims in early rheumatoid arthritis: the ERAN cohort. Rheumatology 2014;53:473–81. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muñoz-Fernández S, Aguilar MD, Rodríguez A, et al. . Evaluation of the impact of nursing clinics in the rheumatology services. Rheumatol Int 2016;36:1309–17. 10.1007/s00296-016-3518-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakagawa H, Tanaka Y, Sano S, et al. . Real-world postmarketing study of the impact of adalimumab treatment on work productivity and activity impairment in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Adv Ther 2019;36:691–707. 10.1007/s12325-018-0866-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olofsson T, Petersson IF, Eriksson JK, et al. . Predictors of work disability after start of anti-TNF therapy in a national cohort of Swedish patients with rheumatoid arthritis: does early anti-TNF therapy bring patients back to work? Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1245–52. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olofsson T, Johansson K, Eriksson JK, et al. . Does disease activity at start of biologic therapy influence work-loss in RA patients? Rheumatology 2016;55:729–34. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olofsson T, Petersson IF, Eriksson JK, et al. . Predictors of work disability during the first 3 years after diagnosis in a national rheumatoid arthritis inception cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:845–53. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olofsson T, Söderling JK, Gülfe A, et al. . Patient‐reported outcomes are more important than objective inflammatory markers for sick leave in biologics‐treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2018;70:1712–6. 10.1002/acr.23619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rahman P, Puig L, Gottlieb AB, et al. . Ustekinumab treatment and improvement of physical function and health-related quality of life in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:1812–22. 10.1002/acr.23000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rendas-Baum R, Kosinski M, Singh A, et al. . Estimated medical expenditure and risk of job loss among rheumatoid arthritis patients undergoing tofacitinib treatment: post hoc analyses of two randomized clinical trials. Rheumatology 2017;56:1386–94. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boonen A, Boone C, Albert A, et al. . Contextual factors influence work outcomes in employed patients with ankylosing spondylitis starting etanercept: 2-year results from AS@Work. Rheumatology 2018;57:791–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shim J, Jones GT, Pathan EMI, et al. . Impact of biological therapy on work outcomes in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register (BSRBR-AS) and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1578–84. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smolen JS, Kremer JM, Gaich CL, et al. . Patient-reported outcomes from a randomised phase III study of baricitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to biological agents (RA-BEACON). Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:694–700. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strand V, Jones TV, Li W, et al. . The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on work and predictors of overall work impairment from three therapeutic scenarios. Int J Clin Rheumtol 2015;10:317–28. 10.2217/ijr.15.40 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strand V, Gossec L, Proudfoot CWJ, et al. . Patient-reported outcomes from a randomized phase III trial of sarilumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:129 10.1186/s13075-018-1614-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Szántó S, Poór G, Opris D, et al. . Improved clinical, functional and work outcomes in spondyloarthritides during real-life adalimumab treatment in central–eastern Europe. J Comp Eff Res 2016;5:475–85. 10.2217/cer-2016-0020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takeuchi T, Nakajima R, Komatsu S, et al. . Impact of adalimumab on work productivity and activity impairment in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: large-scale, prospective, single-cohort ANOUVEAU study. Adv Ther 2017;34:686–702. 10.1007/s12325-017-0477-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tiippana-Kinnunen T, Paimela L, Peltomaa R, et al. . Work disability in Finnish patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a 15-year follow-up. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014;32:88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tillett W, Shaddick G, Jobling A. Effect of anti-TNF and conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug treatment on work disability and clinical outcome in a multicentre observational cohort study of psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatol 2017;56:603–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tran-Duy A, Nguyen TTV, Thijs H, et al. . Longitudinal analyses of presenteeism and its role as a predictor of sick leave in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:1578–85. 10.1002/acr.22655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Heijde D, Braun J, Rudwaleit M, et al. . Improvements in workplace and household productivity with certolizumab pegol treatment in axial spondyloarthritis: results to week 96 of a phase III study. RMD Open 2018;4:e000659. 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boot CRL, de Wind A, van Vilsteren M, et al. . One-year predictors of presenteeism in workers with rheumatoid arthritis: disease-related factors and characteristics of general health and work. J Rheumatol 2018;45:766–70. 10.3899/jrheum.170586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Braun J, et al. . The effect of golimumab therapy on disease activity and health-related quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: 2-year results of the GO-RAISE trial. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1095–103. 10.3899/jrheum.131003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Lunteren M, Ez-Zaitouni Z, Fongen C, et al. . Disease activity decrease is associated with improvement in work productivity over 1 year in early axial spondyloarthritis (SPondyloArthritis Caught Early cohort). Rheumatology 2017;56:2222–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Vilsteren M, Boot CRL, Twisk JWR, et al. . Effectiveness of an integrated care intervention on supervisor support and work functioning of workers with rheumatoid arthritis. Disabil Rehabil 2017;39:354–62. 10.3109/09638288.2016.1145257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wallman JK, Jöud A, Olofsson T, et al. . Work disability in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis patients before and after start of anti-TNF therapy: a population-based regional cohort study from southern Sweden. Rheumatol 2017;17:kew473–24. 10.1093/rheumatology/kew473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Webers C, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. . Sick leave and its predictors in ankylosing spondylitis: long-term results from the outcome in ankylosing spondylitis international study. RMD Open 2018;4:e000766 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wei JC-C, Tsai W-C, Citera G, et al. . Efficacy and safety of etanercept in patients from Latin America, central Europe and Asia with early non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Int J Rheum Dis 2018;21:1443–51. 10.1111/1756-185X.12973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Westhovens R, Ravelingien I, Vandevyvere K, et al. . Improvements in productivity and increased participation in daily activities over 52 weeks of certolizumab pegol treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: results of a Belgian observational study. Acta Clin Belg 2019;74:342–50. 10.1080/17843286.2018.1509923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wiland P, Dudler J, Veale D, et al. . The effect of reduced or withdrawn etanercept-methotrexate therapy on patient-reported outcomes in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2016;43:1268–77. 10.3899/jrheum.151179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Castillo-Ortiz JD, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. . Work outcome in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results from a 12-year followup of an international study. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:544–52. 10.1002/acr.22730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Claudepierre P, Van den Bosch F, Sarzi-Puttini P, et al. . Treatment with golimumab or infliximab reduces health resource utilization and increases work productivity in patients with ankylosing spondylitis in the QUO-VADIS study, a large, prospective real-life cohort. Int J Rheum Dis 2019;22:995–1001. 10.1111/1756-185X.13526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Combe B, Logeart I, Belkacemi MC, et al. . Comparison of the long-term outcome for patients with rheumatoid arthritis with persistent moderate disease activity or disease remission during the first year after diagnosis: data from the ESPOIR cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:724–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cooksey R, Brophy S, Dennis M, et al. . Severe flare as a predictor of poor outcome in ankylosing spondylitis: a cohort study using questionnaire and routine data linkage. Rheumatology 2015;54:1563–72. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barnabe C, Crane L, White T, et al. . Patient-reported outcomes, resource use, and social participation of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologics in Alberta: experience of Indigenous and non-Indigenous patients. J Rheumatol 2018;45:760–5. 10.3899/jrheum.170778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee T-J, Park B-H, Kim JW, et al. . Cost-of-illness and quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis at a tertiary hospital in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2014;29:190–7. 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.2.190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Löfvendahl S, Petersson IF, Theander E, et al. . Incremental costs for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in a population-based cohort in southern Sweden: is it all psoriasis-attributable morbidity? J Rheumatol 2016;43:640–7. 10.3899/jrheum.150406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Løppenthin K, Esbensen BA, Østergaard M, et al. . Welfare costs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and their partners compared with matched controls: a register-based study. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:517–25. 10.1007/s10067-016-3446-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Manning VL, Kaambwa B, Ratcliffe J, et al. . Economic evaluation of a brief education, self-management and upper limb exercise training in people with rheumatoid arthritis (EXTRA) programme: a trial-based analysis. Rheumatology 2015;54:302–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Martikainen JA, Kautiainen H, Rantalaiho V, et al. . Longterm work productivity costs due to absenteeism and permanent work disability in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide register study of 7831 patients. J Rheumatol 2016;43:2101–5. 10.3899/jrheum.160103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mennini FS, Marcellusi A, Gitto L, et al. . Economic burden of rheumatoid arthritis in Italy: possible consequences on anti-citrullinated protein antibody-positive patients. Clin Drug Investig 2017;37:375–86. 10.1007/s40261-016-0491-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Michaud K, Strand V, Shadick NA, et al. . Outcomes and costs of incorporating a multibiomarker disease activity test in the management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2015;54:1640–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Noben C, Vilsteren M, Boot C, et al. . Economic evaluation of an intervention program with the aim to improve at‐work productivity for workers with rheumatoid arthritis. J Occup Health 2017;59:267–79. 10.1539/joh.16-0082-OA [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schofield D, Shrestha R, Cunich M. The economic impacts of using adalimumab (Humira ®) for reducing pain in people with ankylosing spondylitis: a microsimulation study for Australia. Int J Rheum Dis 2018;21:1106–13. 10.1111/1756-185X.13277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Soini E, Asseburg C, Taiha M, et al. . Modeled health economic impact of a hypothetical certolizumab pegol risk-sharing scheme for patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis in Finland. Adv Ther 2017;34:2316–32. 10.1007/s12325-017-0614-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eriksson JK, Johansson K, Askling J, et al. . Costs for hospital care, drugs and lost work days in incident and prevalent rheumatoid arthritis: how large, and how are they distributed? Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:648–54. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Strand V, Tundia N, Song Y, et al. . Economic burden of patients with inadequate response to targeted immunomodulators for rheumatoid arthritis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2018;24:344–52. 10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.4.344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tanaka Y, Yamazaki K, Nakajima R, et al. . Economic impact of adalimumab treatment in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis from the adalimumab non-interventional trial for up-verified effects and utility (ANOUVEAU) study. Mod Rheumatol 2018;28:39–47. 10.1080/14397595.2017.1341459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wallman JK, Eriksson JK, Nilsson Jan-Åke, et al. . Costs in relation to disability, disease activity, and health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: observational data from southern Sweden. J Rheumatol 2016;43:1292–9. 10.3899/jrheum.150617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang BCM, Hsu P-N, Furnback W, et al. . Estimating the economic burden of rheumatoid arthritis in Taiwan using the national health insurance database. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 2016;3:107–14. 10.1007/s40801-016-0063-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eriksson JK, Karlsson JA, Bratt J, et al. . Cost-effectiveness of infliximab versus conventional combination treatment in methotrexate-refractory early rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year results of the register-enriched randomised controlled SWEFOT trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1094–101. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-205060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Husberg M, Bernfort L, Hallert E. Costs and disease activity in early rheumatoid arthritis in 1996–2000 and 2006–2011, improved outcome and shift in distribution of costs: a two-year follow-up. Scand J Rheumatol 2018;47:378–83. 10.1080/03009742.2017.1420224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huscher D, Mittendorf T, von Hinüber U, et al. . Evolution of cost structures in rheumatoid arthritis over the past decade. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:738–45. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jansen JP, Incerti D, Mutebi A, et al. . Cost-effectiveness of sequenced treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with targeted immune modulators. J Med Econ 2017;20:703–14. 10.1080/13696998.2017.1307205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kalkan A, Hallert E, Bernfort L, et al. . Costs of rheumatoid arthritis during the period 1990–2010: a register-based cost-of-illness study in Sweden. Rheumatology 2014;53:153–60. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kristensen LE, Jørgensen TS, Christensen R, et al. . Societal costs and patients’ experience of health inequities before and after diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis: a Danish cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1495–501. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Laires PA, Gouveia M, Canhão H, et al. . The economic impact of early retirement attributed to rheumatic diseases: results from a nationwide population-based epidemiologic study. Public Health 2016;140:151–62. 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ashley KD, Lee LT, Heaton K. Return to work among stroke survivors. Workplace Health Saf 2019;67:87–94. 10.1177/2165079918812483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bijker R, Duijts SFA, Smith SN, et al. . Functional impairments and work-related outcomes in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 2018;28:429–51. 10.1007/s10926-017-9736-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.McQueen J, McFeely G. Case management for return to work for individuals living with cancer: a systematic review. Int J Ther Rehabil 2017;24:203–10. 10.12968/ijtr.2017.24.5.203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Miller PSJ, Hill H, Andersson FL. Nocturia work productivity and activity impairment compared with other common chronic diseases. Pharmacoeconomics 2016;34:1277–97. 10.1007/s40273-016-0441-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Paltrinieri S, Fugazzaro S, Bertozzi L, et al. . Return to work in European cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:2983–94. 10.1007/s00520-018-4270-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Patel JG, Nagar SP, Dalal AA. Indirect costs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review of the economic burden on employers and individuals in the United States. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014;9:289–300. 10.2147/COPD.S57157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rai KK, Adab P, Ayres JG, et al. . Systematic review: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and work-related outcomes. Occup Med 2018;68:99–108. 10.1093/occmed/kqy012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sharples AJ, Cheruvu CVN, Review S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of occupational outcomes after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2017;27:774–81. 10.1007/s11695-016-2367-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Soejima T, Kamibeppu K. Are cancer survivors well-performing workers? A systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2016;12:e383–97. 10.1111/ajco.12515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stone DS, Ganz PA, Pavlish C, et al. . Young adult cancer survivors and work: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 2017;11:765–81. 10.1007/s11764-017-0614-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sun Y, Shigaki CL, Armer JM. Return to work among breast cancer survivors: a literature review. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:709–18. 10.1007/s00520-016-3446-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tavan H, Azadi A, Veisani Y. Return to work in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Palliat Care 2019;25:147–52. 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_114_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bilodeau K, Tremblay D, Durand M-J. Exploration of return-to-work interventions for breast cancer patients: a scoping review. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:1993–2007. 10.1007/s00520-016-3526-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vayr F, Charras L, Savall F, et al. . The impact of bariatric surgery on employment: a systematic review. Bariatr Surg Pract Patient Care 2018;13:54–63. 10.1089/bari.2018.0014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Vayr F, Savall F, Bigay-Game L, et al. . Lung cancer survivors and employment: a systematic review. Lung Cancer 2019;131:31–9. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang L, Hong BY, Kennedy SA, et al. . Predictors of unemployment after breast cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1868–79. 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.3663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wei X-J, Liu X-feng, Fong KNK. Outcomes of return-to-work after stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 2016;79:299–308. 10.1177/0308022615624710 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Büsch K, da Silva SA, Holton M, et al. . Sick leave and disability pension in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:1362–77. 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chow SL, Ting AS, Su TT. Development of conceptual framework to understand factors associated with return to work among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Iran J Public Health 2014;43:391–405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Duijts SFA, van Egmond MP, Spelten E, et al. . Physical and psychosocial problems in cancer survivors beyond return to work: a systematic review. Psychooncology 2014;23:481–92. 10.1002/pon.3467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Edwards JD, Kapoor A, Linkewich E, et al. . Return to work after young stroke: a systematic review. Int J Stroke 2018;13:243–56. 10.1177/1747493017743059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Fong CJ, Murphy KM, Westbrook JD, et al. . Behavioral, psychological, educational, and vocational interventions to facilitate employment outcomes for cancer survivors: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2015;11:1–81. 10.4073/csr.2015.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kamal KM, Covvey JR, Dashputre A, et al. . A systematic review of the effect of cancer treatment on work productivity of patients and caregivers. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2017;23:136–62. 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.2.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.McLennan V, Ludvik D, Chambers S, et al. . Work after prostate cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 2019;13:282–91. 10.1007/s11764-019-00750-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2020-001522supp001.pdf (411.3KB, pdf)