Abstract

Background

The intensive care unit (ICU) is a health care delivery service for patients who are in critical condition with potentially recoverable diseases. Patients can benefit from more detailed observation, monitoring and advanced treatment than other wards or department. The care is advancing but in resource-limited settings, it is lagging far behind and mortality is still higher due to various reasons. Therefore, we aimed to determine the admission patterns, clinical outcomes and associated factors among patients admitted medical intensive care unit (MICU).

Methods

A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted based on a record review of logbook and charts of patients admitted from September, 2015 to April, 2019. Data were entered and analysed using SPSS version 20. Both bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used and a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 738 patients were admitted to medical intensive care unit (MICU) during September, 2015 - April, 2019. Five hundred and four patients (68%) of all intensive care unit (ICU) admissions had complete data. Out of the 504 patients, 268 (53.2%) patients were females. Cardiovascular disease 182(36.1%) was the commonest categorical admission diagnosis. The overall mortality rate was 38.7%. In the multivariate analysis, mortality was associated with need for mechanical ventilation (AOR = 5.87, 95% CI: 3.24 - 10.65) and abnormal mental status at admission (AOR = 2.8, 95% CI: 1.83-4.29). Patients who had stay less than four days in MICU were 5 times more likely to die than those who has stay longer time (AOR= 5.58, 95% CI: 3.58- 8.69).

Conclusions

The overall mortality was considerably high and cardiovascular diseases were the most common cause of admission in MICU. Need for mechanical ventilator, length of intensive care unit stay and mental status at admission were strongly associated with clinical outcome of patients admitted to medical intensive care unit.

Keywords: admission, intensive care unit, length of stay, mortality, outcome

Introduction

Intensive care is a continuum of care from various source of admissions where patients’ requiring a frequent assessment of vital signs, invasive hemodynamic monitoring, intravenous medications and fluid management, ventilatory and nutritional support to assure safe and effective outcomes.1 Access to critical care is a crucial component of healthcare systems hence critically ill patients are admitted to the intensive care units to reduce morbidity and mortality.2,3

Mortality in ICU is a global burden. It varies across the world depend on ICU infrastructure, staff availability, and training, pattern, and cause of ICU admission. In developed contents like North America, Oceania, Asia and Europe in ICU mortality relatively low with the rate of 9.3%, 10.3, 13.7% and 18.7% respectively, while in the rest of the world such as South America, and the Middle East the mortality found to be 21.7% and 26.2%.4,5

In Africa, the ICU mortality rate is high as it compared to the other developed continents. The mortality rate in Nigeria, Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya were 32.9%, 40.1%, 41.1%, and 53.6% respectively.6–9 In Ethiopia, different studies showed that the mortality rate is relatively similar to other Africa countries. Studies done in Jimma, Addis Ababa, and Mekelle showed that the mortality rate was 50.4%, 32% and 27% respectively.10–12

Provision of ICU care is very challenging due to scarcity of drugs and medical equipment’s, lack of well-trained staffs and poor infrastructures are the main challenges to provide optimal care to critically ill patients.3,7 Hence, describing admission patterns and clinical outcome will help to identify commonest causes of admission and to use the available limited resources in developing countries like Ethiopia. Therefore, we aimed to describe the admission patterns, clinical outcomes and associated factors among patients admitted in the medical intensive care unit of University of Gondar specialized comprehensive hospital.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Area and Period

University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (UoGCSH) is located in Amhara National Regional state, Northwest Ethiopia. The critical care service of UOGCSH was started in 2011 as a four-bed MICU capacity with two mechanical ventilators one defibrillator, four non-invasive hemodynamic monitoring devices, one ultrasound machine, and one ABG-analyzer machine. The MICU is an open ICU system run under the department of internal medicine.

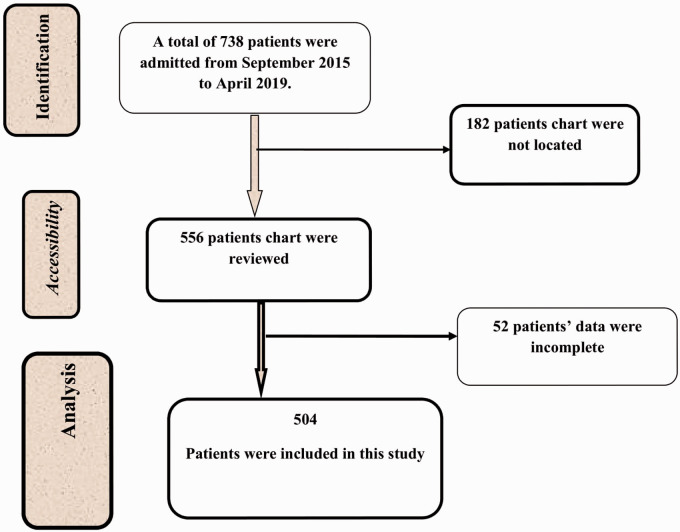

A retrospective cross sectional study was conducted based on the ICU logbook and charts. All consecutively admitted patients to the MICU from September 2015 to April, 2019. Missed patients chart and incomplete data on the charts were the exclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram Illustrating Data Collection Procedure Among Patients Admitted to MICU of UoGCSH September 2015 to April 2019, (N = 504).

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Science, Schoolof Medicine Ethical Review Committee.Permission was obtained from medical director and department of internal medicine of Gondar University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital to conduct this study and to access the medical record. All the collected data was kept confidential and no one except the members of the research team have access to the collected information. All papers of the study was be kept in a secured place under lock and computer records kept locked with passwords and the name or other personal information was not notified in any report.

Study Variables and Data Collection Procedures

The dependent variable was clinical outcome. The independent variables were; Socio-demographic variables, diagnosis at admission, presence of comorbid illness, source, frequency and category of admission, vital signs at admission, interventions and Length of ICU stay. The dependent and independent variables were collected through checklist that was adapted by reviewing different literatures.

Data Processing and Analysis Procedures

Data was entered, coded and cleaned using the Epi-data software and analyzed using SPSS version 20. Descriptive statistics was carried out and categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages whereas; median and interquartile range (IQR) were used for continuous variables. Model fitness was checked using a Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fitness test. Crude odds ratios with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated in the bivariable logistic regression analysis to assess the association between each independent variable and outcome variable. P-value < 0.2 in the bivariable logistic regression was fitted into the multivariable logistic regression analysis. The strength of association was presented using adjusted odds ratio with 95% CI and P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and Admission Characteristics of Among Patients Admitted to MICU

A total of 738 patients were admitted from September 2015 to April 2019 .Two hundred thirty-four patients had incomplete data on logbook and their charts could not be located. So that, 504 (68%) patients were included in this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio Demographic Characteristics Among Patients Admitted to MICU of UoGCSH (September 2015 to April 2019).

| Characteristics | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 236 | 46.8 |

| Female | 268 | 53.2 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <20 | 58 | 11.5 |

| 20–40 | 198 | 39.3 |

| 41–60 | 132 | 26.2 |

| >60 | 116 | 23 |

| Residency | ||

| Urban | 264 | 52.4 |

| Rural | 240 | 47.6 |

| Source of admission | ||

| Medical ward | 299 | 59.3 |

| Emergency department | 168 | 33.3 |

| Surgical ward | 29 | 5.8 |

| Gynecology and obstetrics ward | 8 | 1.6 |

| Category of admission | ||

| Emergency medical patients | 482 | 96 |

| Emergency surgical patients | 18 | 3.6 |

| Elective surgical patients | 2 | 0.4 |

| Frequency of admission | ||

| First admission | 446 | 88.5 |

| Readmission (2 times and above) | 58 | 11.5 |

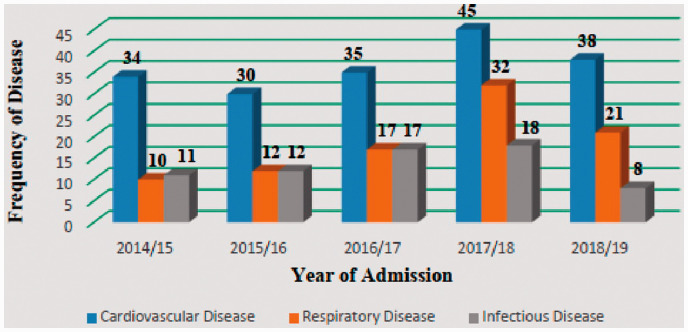

The most common categorical diagnosis at admission was all type cardiovascular, respiratory and infectious diseases with 36.1%, 17.9% and 13.11% of occurrence respectively (Table 2). Hence, these disorders are the most common categorical admission diagnosis (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of Common Specific Admission Diagnosis Among Patients Admitted to MICU of UoGCSH (September 2015 to April 2019).

| Specific diagnosis | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Myocardial infarction(MI) | 96 | 19 |

| Congestive Heart failure (CHF) | 56 | 11.1 |

| Acute respiratory disease syndrome (ARDS) | 45 | 8.9 |

| Septic shock | 37 | 7.3 |

| Diabetic keto Acidosis(DKA) | 28 | 5.6 |

| Stroke | 25 | 5 |

| Human immuno deficiency virus (HIV) infection | 25 | 5 |

| Pneumonia | 25 | 5 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 20 | 4 |

| Pulmonary thrombo embolism (PTE) | 19 | 3.7 |

| Total | 376 | 74.6 |

Figure 2.

Trends of Common Categorical Admission Diagnosis Among Patients Admitted to MICU of UoGCSH September 2015 to April 2019.

The most common specific diagnosis at ICU admission was all types of myocardial infarction 96 (19%) followed by Heart failure 56 (11.1%), ARDS 46(8.9%), septic shock 37 (7.3%) and HIV infection 25 (5%) of the all admissions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of Categorical Admission Diagnosis Among Patients Admitted to MICU of UoGCSH (Gondar; September 2015 to April 2019).

| Disease category | Frequency (N) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease | 182 | 36.1 |

| Respiratory disease | 90 | 17.9 |

| Infectious disease | 66 | 13.1 |

| Neurologic disease | 44 | 8.7 |

| Endocrine disease | 36 | 7.1 |

| Renal disease | 18 | 3.6 |

| Hematologic disease | 22 | 4.4 |

| Poisoning | 14 | 2.8 |

| Miscellenous conditions | 32 | 6.3 |

| Total | 504 | 100 |

Key: Miscellenous conditions; GI disorder, Rheumatologic, Malignancies, Electrolyte disorder.

• All respiratory infections were under respiratory disease.

• Infective heart disease and rheumatic heart disease were under cardiovascular disease

• Guillen Barrie Syndrome was under the category of Infectious disease.

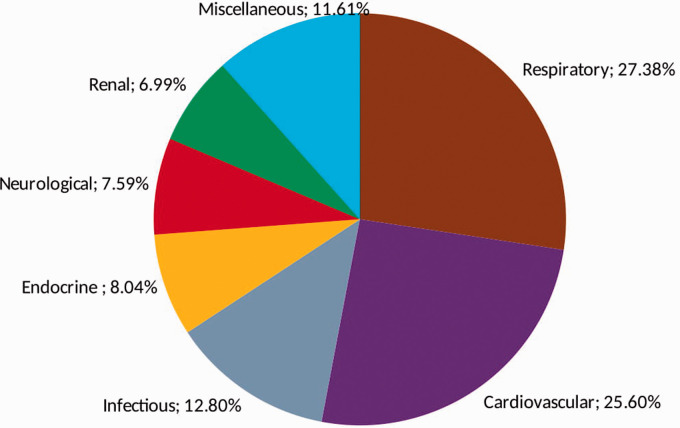

About 256 (50.8%) patients were admitted with comorbid illness from which 84 (16.7%) patients had more than one systemic illness. Respiratory disease 47 (27.2%) were the commonest co-morbid condition followed by cardiovascular 44 (26.3%) and infectious diseases 22 (13.2%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Frequency of Common Comorbid Illness Among Patients Admitted to MICU of UoGCSH. September 2015 to April 2019. Key: Miscellaneous conditions: Gastrointestinal disorder, Post-operative conditions, Trauma, Malignancy, Tetanus, Myasthenia Gravis.

Vital Signs During Admission

Majority of patients had unstable vital signs during admission, 331 (65.7%) patients had high pulse rate and 39.1% of patients had abnormal blood pressure. Regarding the consciousness level of patients at arrival to the intensive care unit, 299 (59.3%) patient were conscious, the rest was presented with disturbed mental status (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of Admission Vital Signs Among Patients Admitted to MICU of UoGCSH (September 2015 to April 2019; N = 504).

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Pulse rate (bpm) | ||

| <60 | 4 | 0.8 |

| 60–100 | 166 | 32.9 |

| >100 | 331 | 65.7 |

| No pulse | 3 | 0.6 |

| Respiratory rate (bpm) | ||

| <12 | 7 | 1.4 |

| 12–20 | 72 | 14.3 |

| >20 | 423 | 83.9 |

| Apnea | 2 | 0.4 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | ||

| 65–106 | 302 | 59.9 |

| <65 | 122 | 24.2 |

| >106 | 65 | 12.9 |

| Unrecordable | 15 | 3 |

| Peripheral oxygen saturation (SPO2) | ||

| <90% | 227 | 45.0 |

| 90%–100% | 277 | 55.0 |

| Temperature (°C) | ||

| <36.5 | 120 | 23.8 |

| 36.5–37.5 | 151 | 30.0 |

| >37.5 | 233 | 46.2 |

| Mental status | ||

| Concious | 299 | 59.3 |

| Confused | 53 | 10.5 |

| Lethargic | 43 | 8.5 |

| Unconcious | 109 | 21.7 |

| Total | ||

| 504 | ||

Intervention Done in MICU

Three hundred and eighty-two (75.8%) patients were in mechanical ventilation with facilitation of tracheal intubation, 323 (64.1%) were in antibiotics, 311 (61.6%) were received anticoagulants, 162 (32.1%) patients received inotropes.

Clinical Outcome of Patients Admitted to MICU

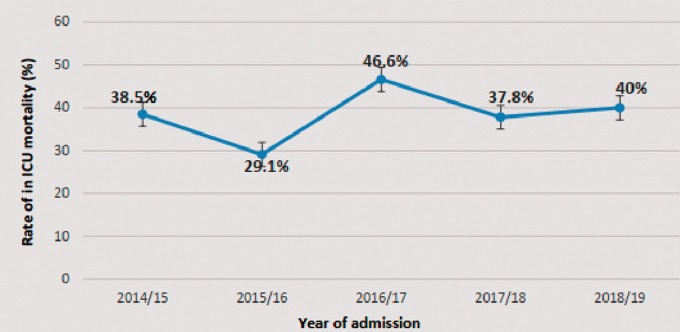

The overall mortality rate of the MICU was 38.87%. Three hundred and nine (61.3%) patients were survivors, among them 238 (77%) of patients were improved and transferred to the wards. 30 (9.7%) were cured and got discharged to home, 36 (11.6%) were left against medical advice, and 5 (1.6%) patients were referred to another setting for further treatment.

The highest mortality rate (46.6%) was observed in 2009; the lowest mortality rate (29.1%) was observed in 2008 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Trend of in ICU Mortality Among Patients Admitted to MICU of UoGCSH from 2014–2019.

The proportion of death among females (40.6%) was higher than males (36.5%). However, there was no significant sex difference in patients clinical outcome(X2=1, P = 0.33). The proportion of mortality was increased as the age increases. Among the non survivors, 43.9% of patients were beyond 60 years old and 32.7% patients were under 20 years old.

In ICU mortality was not significant among source of admission as the proportion of mortality from emergency department, medical ward, surgical ward and gynecology/obstetrics was found to be 40%, 38%, 34%, and 40% respectively with (P = 0.91) Among the commonest specific admission diagnosis, cardiogenic shock (57.1%) had the highest case fatality ratio followed by ARDS (54.4%) and ischemic heart disease (53.5%) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Case Fatality Ratio, Among Patients Admitted to MICU of UoGCSH (September 2015 to April 2019).

| Specific Disease | Number of Patients Admitted | Case Fatality Ration |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiogenic shock | 14 | 57.1 |

| Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome(ARDS) | 22 | 54.4 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 71 | 53.5 |

| Congestive heart failure | 29 | 44.8 |

| Severe pneumonia | 15 | 40 |

| Septic shock | 32 | 37.5 |

| Pulmonary Thrombo embolism (PTE) | 14 | 34.5 |

| Stroke | 11 | 19.7 |

| Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection | 17 | 19.7 |

| Diabetic Keto Acidosis (DKA) | 16 | 29.4 |

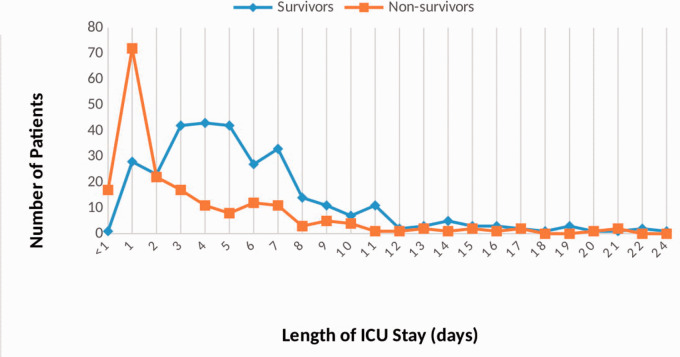

The median length of ICU stay (IQR) was 4 (2–5) days. The most frequent stay (19.8%) was 1 day. The minimum stay in ICU was 30 minutes secondary to poisoning while the maximum stay was 24 days with the diagnosis of myocardial infarction. About 81.7% of patients died or discharged with in the first one week of stay. The median (IQR) duration of mechanical ventilation was 4.5(1-6) days. Patients with Myocardial infarction, Guillian Barre Syndrome, and ARDS had longer duration of mechanical ventilation. Patients who stayed in MICU for less than 4 days were 5 times more likely to die than who stayed four and above days (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Length of ICU Stay Between Survivor and Non-Survivor Among Patients Admitted to MICU of UoGCSH September 2015 to April 2019.

Bivariate logistic analysis shown that gender, diagnosis at admission, need and duration of mechanical ventilation, length of ICU stay, mean arterial pressure, and mental status at admission was significantly associated with the clinical outcome. However, in a multivariate analysis, the associated risk factors of death were the need for mechanical ventilation, abnormal mental status at admission and length of ICU stay (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Showing the Factors Associated With Mortality Among Patients Admitted to MICU of UoGCSH (September 2015 to April 2019).

| Variables | Crude Odds Ratio | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical ventilator | ||||

| Yes | 4.312 | (3.244, 10.65) | 0.001* | |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Mental status at admission | ||||

| Conscious | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Abnormal mental status | 0.237 | 2.808 | (1.843,4.279) | 0.001* |

| Length of ICU stay | ||||

| <4 days | 4.37 | 5.58 | (3.58, 8.69) | 0.001* |

| ≥4 days | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Key: *Significantly associated at P < 0.05, 1.00: reference.

Discussion

The outcomes of patients admitted to intensive care unit depends on the clinical condition of patients arrival, level of training and experience of staff, resource, infrastructure and capacity of the unit.4,6,7

In this study, the overall mortality rate in ICU found to be 38.7% (95% CI: 34.5, 43.1). This finding is comparable with studies done in Addis Ababa (39%) and Jimma (37.7%).10,11 It also similar to the studies conducted in Nigeria (34.6%), Uganda (40.1%) and Tanzania (41.1%).6–8 However, this result was higher than studies done in Mekelle, Ethiopia (27%) and Scandinavian countries (9.1%).12,13 This discrepancy might be due to lack of necessary medical equipments (ABG-analyzer machine, portable dialysis machine and portable x-ray service), infrastructure, and training. In addition, the lack of high dependency unit in the study area may contribute high mortality rate.7,8

In the current study, the median length of ICU stay found to be 4 days which is similar to the other African countries.8,9 Out of 504 patients, 118 (23%) where stayed in ICU 24 hours or less and 89 (75%) of patients died. In addition, patients who stayed in ICU for less than four days were 5 times more likely to die than patients who stayed four or more days with (AOR = 5.58, p < 0.001) which is comparable with the study done in Uganda.14 However, our result was different from the study conducted in Hosanna, the length of ICU stay was more than 14 days with ICU mortality (OR = 4.113, P < 0.039).15 This discrepancy might be explained due to late arrival to ICU and delay in intervention, shortage of crucial emergency drugs, absence of airway management equipment’s in the medical emergency ward. Furthermore, vital signs of the patients on admission to the MICU were found to be poor, which may show a gap in the continuity of care from the admission source to MICU. Early death might also be explained by a limited number of ICU bed since the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine recommends the ICU need to have at least 5% of total hospital beds. Besides, shortage of functional mechanical ventilator which delays and denied admission of critically ill patients to MICU.7,16

This study revealed that need for mechanical ventilation is independent risk factor of ICU mortality with (AOR: 5.578, P < 0.001) which was similar with the studies done in Kenya and Brazil (AOR= 10.7, p < 0.001) and (AOR: 6.37, p < 0.001) respectively.9,17 The possible explanation for this association could be related that mechanical ventilators initiated for the patients with respiratory failure, unable to protect the airway and hemodynamic instability. Furthermore, patients who need intubation and mechanical ventilator more vulnerable for ventilator associated pneumonia and other nosocomial infections.18,19 Our study reveled that patients who presented with abnormal mental status were more likely to die than conscious patients (AOR: 2.741, P < 0.001). Disturbance level of consciousness is related with severe decompensated disease, cerebral hypo-perfusion due to sepsis, blood loss, poisoning, and neurological disorder.20

Cardiovascular disease accounted 36% of all ICU admission followed by respiratory (17.9%) which is similar to the studies done in Mekelle and Jimma.12,21 However, it was different from studies done in Uganda and Nigeria, infectious illness and post-operative care were the main reasons for admission.3,7

In the current study, there was higher case fatality ratio of cardiogenic shock (57.1%), ARDS (54.4%) and ischemic heart disease (53.5%) which is different from studies done in Mekelle and Addis Ababa, septic shock (58%) and severe pneumonia (56.4%) respectively.11,12 This discrepancy might be due to lack isolated cardiac intensive care unit for percutaneous intervention and pacing.

Conclusion

The overall mortality rate in the MICU was considerable high and cardiovascular disorders were the most common cause of admission and death. Need for mechanical ventilator, abnormal mental status on admission and short ICU stay were significantly associated with the clinical outcome of MICU patients. The majority of critically ill patients were dying within 24 hours of admission. Therefore, improving the acute critical care service through the expansion of the care, supply emergency airway equipments and medications, implementation of admission criteria protocol could decrease mortality and morbidities among critical ill patients admitted to MICU.

Limitation of the Study

Retrospective cross sectional study has limitations especially, it does not show cause –effect relationship . in addition, due to incomplete data on the ICU logbook and charts, variables related to Physiologic and laboratory variables necessary to calculate severity and prognostic score such as sequential organ failure assesment(SOFA), Simplifed Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Disease Classifcation System (APACHE) were not analyzed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Internal Medicine Department, School of Medicine, College of Medicine and Health Science for supporting to conduct this research and also our appreciation goes to the data collectors, colleagues and staffs working in the chart and information center of UOGCSH.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. HGT contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquired; analyzed and interpreted the data drafted and revised the manuscript. GFL, NM, DYF and NRA participate in reviewing the design and methods of data collection, interpretation and preparation of the manuscript. All authors participate in preparation and critical review of the manuscripts. In addition, all authors read and approved the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Material: The datasets used/or analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: This study was approved by the ethical review board of School of Medicine, College of Medicine and Health Sciences with reference number of (SOM/140/02/2019). Permission also received from medical director of the hospital before the commencement of the study. Data was collected from chart and log book clinical registry.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Girmay Fitiwi Lema https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6229-5121

Nebiyu Mesfin https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1327-4986

References

- 1.Nates JL, Nunnally M, Kleinpell R, et al. ICU admission, discharge, and triage guidelines: a framework to enhance clinical operations, development of institutional policies, and further research. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44(8):1553–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park J, Jeon K, Chung CR, et al. A nationwide analysis of intensive care unit admissions, 2009–2014—The Korean ICU National Data (KIND) study. J Crit Care. 2018; 44:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onyekwulu F, Anya S. Pattern of admission and outcome of patients admitted into the Intensive Care Unit of University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Enugu: a 5-year review. Niger J Clin Pract. 2015; 18(6):775–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent J-L, Marshall JC, Ñamendys-Silva SA, et al. Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: the intensive care over nations (ICON) audit. Lancet Respir Med. 2014; 2(5):380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes A, Moreno RP. Intensive care provision: a global problem. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Intensiva. 2012; 24(4):322–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilori IU, Kalu QN. Intensive care admissions and outcome at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. J Crit Care. 2012; 27(1):105.e1–105.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwizera A, Dünser M, Nakibuuka J. National intensive care unit bed capacity and ICU patient characteristics in a low income country. BMC Res Notes. 2012; 5(1):475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawe HR, Mfinanga JA, Lidenge SJ, et al. Disease patterns and clinical outcomes of patients admitted in intensive care units of tertiary referral hospitals of Tanzania. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014; 14(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lalani HS, Waweru-Siika W, Mwogi T, et al. Intensive care outcomes and mortality prediction at a national referral hospital in western Kenya. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018; 15(11):1336–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith ZA, Ayele Y, McDonald P. Outcomes in critical care delivery at Jimma University Specialised Hospital, Ethiopia. Anaesthes Intens Care. 2013; 41(3):363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kedir S, Berhane A, Bayisa T, Wuletaw T. Admission patterns and outcomes in the medical intensive care unit of st. Paul’s hospital millennium medical college, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2017; 55(1):19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gidey K, Hailu A, Bayray A. Pattern and outcome of medical intensive care unit admissions to Ayder comprehensive specialized hospital in Tigray, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2017; 56(1). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strand K, Walther SM, Reinikainen M, et al. Variations in the length of stay of intensive care unit nonsurvivors in three Scandinavian countries. Crit Care. 2010; 14(5):R175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murthy S, Leligdowicz A, Adhikari NK. Intensive care unit capacity in low-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015; 10(1):e0116949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suleiman M, Adem Abdi O, Gete Getish B. Clinical outcomes of patients admitted in intensive care units of Nigist Eleni Mohammed Memorial Hospital of Hosanna, Southern Ethiopia. Int J Med Med Sci. 2017; 9:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall JC, Bosco L, Adhikari NK, et al. What is an intensive care unit? A report of the task force of the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. J Crit Care. 2017; 37:270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toufen C, Jr, Franca SA, Okamoto VN, Salge JM, Carvalho CRR. Infection as an independent risk factor for mortality in the surgical intensive care unit. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2013; 68(8):1103–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fialkow L, Farenzena M, Wawrzeniak IC, et al. Mechanical ventilation in patients in the intensive care unit of a general university hospital in southern Brazil: an epidemiological study. Clinics. 2016; 71(3):144–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouadma L, Sonneville R, Garrouste-Orgeas M, et al. Ventilator-associated events: prevalence, outcome, and relationship with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2015; 43(9):1798–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barfod C, Lauritzen MMP, Danker JK, et al. Abnormal vital signs are strong predictors for intensive care unit admission and in-hospital mortality in adults triaged in the emergency department—a prospective cohort study. Scand J Trauma Resuscitat Emerg Med. 2012; 20(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agalu A, Woldie M, Ayele Y, Bedada W. Reasons for admission and mortalities following admissions in the intensive care unit of a specialized hospital, in Ethiopia. Int J Med Med Sci. 2014; 6(9):195–200. [Google Scholar]