Abstract

It has been reported that myocardial damage and heart failure are more common in COVID-19 patients with severe symptoms. The aim of our study was to measure the right ventricular functions of COVID-19 patients 30 days after their discharge, and compare them to the right ventricular functions of healthy volunteers. Fifty one patients with COVID-19 and 32 healthy volunteers who underwent echocardiographic examinations were enrolled in our study. 29 patients were treated for severe and 22 patients were treated for moderate COVID-19 pneumonia. The study was conducted prospectively, in a single center, between 15 May 2020 and 15 July 2020. We analyzed the right ventricular functions of the patients using conventional techniques and two-dimensional speckle-tracking. Right ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic area were statistically higher than control group. The right ventricular fractional area change (RVFAC) was significantly lesser in the patient group compared to the control group. Tricuspid annular plane systolic motion (TAPSE) was within normal limits in both groups, it was lower in the patient group compared to the control group. Pulmonary artery pressure was found to be significantly higher in the patient group. Right ventricular global longitudinal strain (RV-GLS) was lesser than the control group (− 15.7 [(− 12.6)–(− 18.7)] vs. − 18.1 [(− 14.8)–(− 21)]; p 0.011). Right ventricular free wall strain (RV-FWS) was lesser in the patient group compared to the control group (− 16 [(− 12.7)–(− 19)] vs − 21.6 [(− 17)–(− 25.3)]; p < 0.001). We found subclinical right ventricular dysfunction in the echocardiographies of COVID-19 patients although there were no risk factors.

Keywords: COVID-19, Echocardiography, Right ventricular function, Speckle tracking echocardiography, Comorbidity

Introduction

COVID-19 is a recently recognised viral illness that has spread rapidly worldwide. Viral involvement in the cardiovascular and respiratory system is the most significant predictor of morbidity and mortality in COVID-19 [1, 2].

It has been shown that COVID-19 may cause right and left ventricular systolic dysfunction, acute myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy and myocarditis [3–8]. It has been reported that myocardial damage and heart failure are more common in COVID-19 patients with severe symptoms [9].

The pulmonary circulation and the right ventricular functions are affected due to the involvement of respiratory system. The right ventricle is more susceptible to impairment when compared to left ventricle, due to the increased right ventricular afterload. Techniques, such as three-dimensional evaluation of the right ventricular ejection fraction, tissue Doppler imaging and strain imaging, enable us to detect the impairment of systolic functions in the right ventricle. Additionally, subclinical right ventricular dysfunction can be detected through two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography [10–12].

The risk of severe COVID-19 is known to be higher among the elderly and those who have underlying comorbidities. Nonetheless, the illness can occur in healthy individuals of any age and progress with severe symptoms [13, 14].

It is unclear how much damage or sequelae remain in patients after the active period of COVID-19 infection. In our study, we measured the right ventricular functions of COVID-19 patients 30 days after their discharge and compared them to the right ventricular functions of healthy volunteers.

Method

Study population

We conducted a prospective study between 15 May 2020 and 15 July 2020, in Umraniye Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey. A total of 51 adult patients of which 29 with severe and 22 with moderate COVID-19 pneumonia under the clinical and radiological definition of the World Health Organization, were included in the study 30 days after their discharge. 32 healthy volunteers with demographic characteristics similar to the patient group were included in the control group. Clinical, radiological and laboratory information were collected from the hospital’s medical database. Blood samples of the patients were taken at the admission. Echocardiography was performed 30 days after discharge.

Patients over 18 years of age without comorbidity were enrolled to the study. Initially, patients with bilateral moderate to severe lung involvement on computed tomography, positive SARS-CoV PCR test, and patients who were negative for two consecutive SARS-CoV PCR tests after discharge were included in the study. Patients with a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, right or left ventricular failure, atrial fibrillation, right and left bundle branch block, moderate-severe valve pathology, diabetes mellitus, anemia, chronic renal failure, thyroid dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary embolism, cancer, rheumatic valve disease, chronic lung disease, BMI > 30 kg/m2, and patients diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome and myocarditis during their hospitalization were excluded.

Echocardiographic examinations

Transthoracic echocardiographic examinations were performed in all patients using the EPIQ 7C ultrasound system (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, Massachusetts). The procedure was performed at midday to eliminate the effect of circadian changes on diastolic dysfunction. All the recorded echocardiographic images were stored and analysed by two independent observers. Two-dimensional and M-mode transthoracic echocardiographies were performed on the basis of the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography [15]. M mode measurements, left ventricular end-diastolic (LVEDD) and end-systolic diameter (LVESD), interventricular septum (IVS), posterior wall (PW) and left atrium (LA) diameter were measured from the parasternal long axis. Right ventricular (RV) diastolic diameter, RV diastolic area, RV systolic area and right ventricular apicobasal height were determined from the RV focused apical 4-chamber view. RVFAC was calculated. Mitral and tricuspid early diastolic and late diastolic maximal flow velocities were measured from the apical 4-chamber view by using pulse wave (PW) Doppler. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated by using the Teicholz method. Pulmonary artery systolic pressure was calculated from the tricuspid regurgitation jet using Bernoulli's equation. Estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure (sPAP) was calculated by adding 5–10 mmHg to these values according to the vena cava inferior width. Intermittent flow spectral mode was used for tissue Doppler imaging. Systolic, early and late diastolic tissue velocities were measured by taking tissue Doppler images from the tricuspid lateral annulus in the apical 4-chamber image. Right ventricle myocardial performance index (MPI) was calculated with tissue Doppler. TAPSE was measured using the tricuspid annular M mode.

Measurement of right ventricular strain

Strain measurements by two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography method were conducted according to the recommendations of the current echocardiography guideline [16]. All of the images were analysed using 2D AutoStrain software (Qlab, Philips Healthcare, Andover, Massachusetts). Since there was no software to process the right ventricular strain pattern, the software for the left ventricular strain pattern was used. After tracing the RV endocardial border, the region of interest was automatically generated. Global right ventricular free wall strain value was calculated as the mean of the strain values in the 3 segments of the RV free wall.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) software version 22.0. Mean ± Standard deviation was used for descriptive parameters. For comparison of quantitative data, student-t test (normally distributed data), and Mann Whitney-U test (non-normally distributed data) was used. Paired sample-t test was used for in-group comparisons of parameters, and chi-square test was used for comparison of qualitative data. The relationships among the inflammatory parameters with RV free wall strain were assessed using Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation analyses according to the normality of the data. The results were evaluated within a 95% confidence interval. A p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Among the 51 patients included in this study, 39 were male (77%), and the mean age was 45.3 ± 11.2. The most common complaint of the patients during their hospitalization was cough (75%). Other symptoms were high fever (59%), dyspnoea (36%), and chest pain (24%). The average length of stay of the patients in the hospital was 10.5 (6–13) days. Clinical, demographic and laboratory characteristics of the patients are listed at Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical, demographic and laboratory characteristics of Covid-19 patients in hospital

| Variables | Patients (n: 51) |

Control patients (n:32) | p values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 45.3 ± 11.2 | 46.5 ± 9.6 | 0.312 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 39 (77%) | 28 (88%) | 0.091 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 ± 2.7 | 26.1 ± 3 | 0.502 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 116.3 ± 9.8 | 122 ± 5.3 | 0.115 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 73.8 ± 7.1 | 77.8 ± 6.8 | 0.097 |

| Pulse, beats/min | 89.2 ± 13.9 | 82.3 ± 10,7 | 0.104 |

| SaO2 | 90.4 ± 3.4 | 93.3 ± 1,8 | 0.082 |

| Symptoms n, % | |||

| Dispnea | 18 (36%) | ||

| Fever | 30 (59%) | ||

| Cough | 38 (75%) | ||

| Chestpain | 12 (24%) | ||

| WBC | 6100 [4787–8925] | ||

| Neutrophil, count | 3615 [2467–5402] | ||

| Lymphocyte, count | 1300 [878–1807] | ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.9 ± 1.3 | ||

| Platelet | 201.5 ± 64.2 | ||

| CRP, mg/dL | 4.15 [0.7–11] | ||

| LDH, U/L | 267 [206–425] | ||

| D-dimer, rng/mL | 640 [417–1262] | ||

| Length of hospital stay, days | 10.5 [6–13] |

BMI body mass index, SaO2 arterial oxygen saturation, WBC white blood cell, CRP C-reactive protein, LDH Lactate dehydrogenase

All the patients were treated according to the national COVID-19 treatment guideline. The treatments included hydroxychloroquine, favipravir, antibiotics [17]. Sc heparin was given to all patients and pulmonary embolism was not documented in any patient. Oxygen therapy was also given to all patients. Non-invasive mechanical ventilation was performed in three patients in the intensive care unit.

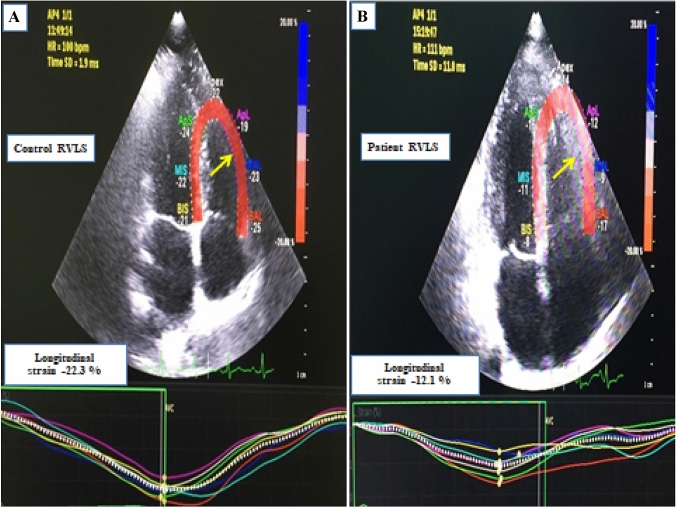

Echocardiography parameters were given in the Table 2. LVEDD and LVESD, IVS and PW, LVEF and LA diameters were similar between the groups. By using PW, while late diastolic peak velocity (A) was higher in the patient group compared to the healthy group, transmitral early diastolic peak velocity (E) was similar in both groups. While the RV height was significantly higher than the control group, the right ventricular end-diastolic diameter was lower than the control group. Right ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic area were statistically higher than control group (p < 0.001). The RVFAC was significantly less in the patient group compared to the control group (43.4 ± 7.8 vs. 51.5 ± 6.2; p < 0.001). TAPSE was within normal limits in both groups however, it was lower in the patient group compared to the control group (p 0.006). Pulmonary artery pressure was found to be significantly higher in the patient group compared to the control group (27.9 ± 4.8 mmHg vs 22.2 ± 7.3 mmHg; p < 0.001). While PW and transtricuspid early diastolic (E) were similar in both groups, late diastolic (A) was lesser in control group.Tricuspid valve S, E, A values evaluated by tissue Doppler were similar in both groups. MPI calculated by right ventricular tissue Doppler was significantly higher in the patient group compared to the control group (0.58 ± 0.06 vs. 0.39 ± 0.04; p < 0.001). Right ventricular GLS was measured less than the control group (− 15.7 [(− 12.6)–(− 18.7)] vs. − 18.1 [(− 14.8)–(− 21)]; p 0.011). Right ventricular free wall strain was found to be significantly less in the patient group compared to the control group (− 16 [(− 12.7)–(− 19)] vs − 21.6 [(− 17)–(− 25.3)]; p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Echocardiographic findings in covid-19 pneumonia patients vs control group

| Variables | Patients (n:51) | Control group (n:32) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEDD, cm | 4.83 ± 0.33 | 4.68 ± 0.35 | 0.059 |

| LVESD, cm | 2.95 ± 0.33 | 2.84 ± 0.27 | 0.130 |

| LA, cm | 3.47 ± 0.30 | 3.31 ± 0.45 | 0.095 |

| IVS, cm | 0.93 ± 0.13 | 0.89 ± 0.08 | 0.077 |

| PW, cm | 0.89 ± 0.15 | 0.83 ± 0.12 | 0.058 |

| LVEF % | 65.4 ± 2.7 | 65.1 ± 2.8 | 0.602 |

| Mitral E | 74 ± 14 | 78 ± 14 | 0.198 |

| Mitral A | 71 ± 16 | 61 ± 15 | 0.005 |

| RV-GLS % | − 15.7 [(− 12.6)–(− 18.7)] | − 18.1 [(− 14.8)–(− 21)] | 0.011 |

| RA area, mm2 | 11.4 ± 2.4 | 12.3 ± 2 | 0.77 |

| RV EDD bazal, cm | 2.57 ± 0.32 | 3.11 ± 0.24 | < 0.001 |

| RV EDD mid, cm | 2.1 ± 0.21 | 2.3 ± 0.24 | < 0.001 |

| RV height, cm | 7.1 ± 0.4 | 6.5 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 |

| RV ED area, mm2 | 19.8 ± 3.4 | 16.1 ± 3.1 | < 0.001 |

| RV ES area, mm2 | 11.1 ± 2.5 | 7.7 ± 1.2 | < 0.001 |

| RVFAC % | 43.4 ± 7.8 | 51.5 ± 6.2 | < 0.001 |

| TAPSE cm | 2.24 ± 0.26 | 2.50 ± 0.44 | 0.006 |

| Triküspid E | 58 ± 11 | 59 ± 12 | 0.925 |

| Triküspid A | 58 ± 17 | 44 ± 10 | < 0.001 |

| RV MPI | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 0.39 ± 0.04 | < 0.001 |

| Triküspid tdi E` | 14 ± 3 | 13 ± 3 | 0.117 |

| Triküspid tdi A` | 15 ± 4 | 16 ± 5 | 0.653 |

| Triküspid tdi S | 14 ± 2 | 15 ± 2 | 0.459 |

| sPAP, mmHg | 27.9 ± 4.8 | 22.2 ± 7.3 | < 0.001 |

| RV-FWS | − 16 [(− 12.7)–(− 19)] | − 21.6 [(− 17)–(− 25.3)] | < 0.001 |

LVEDD left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, LVESD left ventricular end- systolic diameter, LA left atrial, IVS interventricular septum, PW posterior wall, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, RV-GLS right ventricular global longitudinal strain, RA right atrial area, RV EDD right ventricular end-diastolic diameter, RV ES righ ventricular end-systolic, RVFAC right ventricular fractional area change, TAPSE tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, RV MPI right ventricle myocardial performance index, tdi tissue Doppler imaging, sPAP systolic pulmonary artery pressure, RV-FWS RV Free wall strain

Fig. 1.

2D speckle-tracking strain image of right ventricle. a Control patient; b COVID-19 patient

The relationships of the RV-FWS values with inflammatory markers were evaluated via Spearman’s or Pearson’s correlation analyses. A weak positive correlation was found between RV-FWS and WBC, a moderate positive correlation was found between RV-FWS and LDH, a strong positive correlation was found between RV-FWS and CRP, and a weak positive correlation was found between RV-FWS and d-dimer. No significant correlation was found between RV-FWS and neutrophil and lymphocyte count (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation of right ventricle free wall strain with inflammatory markers

| r | p | |

|---|---|---|

| WBC | 0.392 | 0.001 |

| Neutrophil | − 0.100 | 0.486 |

| Lymphocyte | − 0.240 | 0.445 |

| LDH | 0.428 | 0.003 |

| CRP | 0.612 | < 0.001 |

| D-dimer | 0.287 | 0.05 |

CRP C-reactive protein, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, WBC white blood cell

Discussion

Our study is a prospective study comparing the right ventricular functions of patients treated for moderate-severe COVID-19 pneumonia and healthy volunteers using conventional echocardiography and 2D STE. We found normal left ventricular systolic functions in the patient group but a subclinical impairment in right ventricular functions.

How much damage or sequelae remain in patients after the period of active COVID-19 infection is currently unknown. Studies with long-term follow-up of patients are needed. Previous studies with MERS and SARS-CoV can guide us for COVID-19.

In a study in which patients with SARS-CoV infection were followed for 12 years, 44% of the patients developed cardiovascular abnormalities [18]. Acute myocarditis and myocardial edema developing after MERS-CoV infection was demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging. In the 3 month follow up of these patients, it was found that severe left ventricular dysfunction persisted [19].

There are many studies showing the cardiac complications in patients with community-acquired pneumonia [20–23]. Corrales-Medina et al. found that the risk of active cardiovascular disease increased for several years after hospitalization in these patients [24].

COVID-19 infection can cause cardiac damage by various mechanisms. These are cytokine storm and multiple organ failure due to acute systemic inflammatory response, oxygen demand–supply mismatch in myocardium secondary to severe hypoxia resulting from acute respiratory failure, cardiotoxicity due to the agents used in treatment, coronary thrombosis due to plaque rupture and embolic complication caused by tendency to thrombosis due to systemic inflammation and direct invasion of the virus [25, 26].

SARS-CoV-2 triggers systemic inflammation and coagulopathy. There are many publications showing thromboembolic complications of the virus. Although some patients receive anticoagulant therapy, thromboembolic complications may occur [27]. Thrombotic microangiopathy and widespread microthrombosis were observed in postmortem histopathological studies. Therefore, one of the reasons of echocardiographic changes in our study may be subclinical pulmonary microthrombi [28, 29].

It is known that viral infections as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) play a role in the ethiology of pulmonary hypertension [30, 31]. Pulmonary vascular effects of COVID-19 infection are similar to the pathology of pulmonary hypertension [32, 33]. In our study, we found significantly higher pulmonary artery pressure in the patient group compared to the control group. In the following years, patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 infection may also develop primary pulmonary hypertension. Therefore, the long-term effects of COVID-19 on the pulmonary circulation should be investigated.

Ming-Yen et al. performed cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on 16 patients with mild-moderate COVID-19 infection, a median of 56 days after discharge. Their found abnormal cardiac MR findings in 56% of the patients [34]. In another cardiac MRI study of 100 adult patients, 67 of whom were mildly ill, who recovered from COVID-19 infection, researchers showed that 78% of patients had cardiac involvement and 60% had ongoing myocardial inflammation [35]. These cardiac MRI studies performed on discharged patients with COVID-19 infection support the findings in our study.

Elsayed et al. found a high rate of right ventricular dilatation and dysfunction in COVID-19 patients in their echocardiographic study, but found that left ventricular function rarely worsened [36]. Szekely et al. found that left ventricular systolic function is preserved in most patients, but left ventricular diastolic function and right ventricular function may be impaired [37].

In the echocardiographic study performed in 1216 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 from 69 countries on six continents, abnormal echocardiographic findings were found in 667 (55%) patients. Researchers observed the right ventricular abnormalities in a quarter of patients that were more common in patients with more severe symptoms of COVID-19 [38]. These abovementioned findings were similar with the results of our study. Different from our study, Krishnamoorthy et al. reported right ventricular dysfunction in 41.7% of the patients and left ventricular dysfunction in 58.3% via using two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography [39]. It was found that right ventricular longitudinal strain was a strong predictor of mortality in COVID-19 patients [40]. In our study, we found that RV-GLS and RV-FWS values were less in the patient group compared to the control group.

While some of the patients who had COVID-19 pneumonia had a decrease in left ventricular EF, it was found to be within normal limits in another patients. Patients with low left ventricular EF are mostly the group of patients who have severe-critical COVID-19 pneumonia and have comorbidities. Although left ventricular EF is normal, there are also patients with a disorder detected in strain echocardiography studies [37–41]. Since our patients are a group of patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 pneumonia without comorbidity, we may have found left ventricular EFs normal. Similar to other studies, we think that we might have found deterioration in the left ventricular strain in our patient group.

Baycan et al. found that left ventricular global longitudinal strain and right ventricular longitudinal strain decreased in COVID-19 patients with severe symptoms, compared to patients without severe symptoms and the control group. However, these patients consisted of those with comorbidities. In this study, there was no statistically significant difference in RVFAC values between the patient and control groups [41]. In our study, we found that the RVFAC value was significantly lower in the patient group compared to the control group. Our study showed that right ventricular dysfunction continued in the first month after discharge.

Conclusion

Since COVID-19 is a new infection, its long-term effects are unknown. We found subclinical right ventricular dysfunction in the echocardiographic analysis of COVID-19 patients although there were no risk factors. These findings indicate the need for ongoing investigation of the long-term cardiovascular consequences of COVID-19. Long-term follow-up of patients with especially severe and critical COVID-19 pneumonia can be done by strain echocardiography.

Limitations

The study was a single center study and the sample size was relatively small. The limitations of our study are that the patients did not have basal echocardiography and the follow-up period was short. Confirmation of RV dysfunction by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging and correlation with RV-GLS could strengthen our results.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The ethics committee of the Umraniye Training and Research Hospital, Health Sciences University of Turkey, approved this study (Ref. No:B.10.1.TKH.4.34.H.GP.0.01/163).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madjid M, Safavi-Naeini P, Solomon SD, Vardeny O. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):831–840. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu H, Ma F, Wei X, Fang Y. Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis saved with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin. Eur Heart J. 2020 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rali AS, Ranka S, Shah Z, Sauer AJ. Mechanisms of myocardial injury in coronavirus disease 2019. Card Fail Rev. 2020;6:e15. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2020.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bangalore S, Sharma MHA, Slotwiner A, et al. ST-segment elevation in patients with Covid-19–a case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(25):2478–2480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer P, Degrauwe S, Delden CV, Ghadri JR, Templin C. Typical takotsubo syndrome triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(19):1860. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varga S, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;26(368):m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szekely Y, Lichter Y, Taieb P, et al. Spectrum of cardiac manifestations in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—a systematic echocardiographic study. Circulation. 2020;142(4):342–353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vitarelli A, Terzano C. Do we have two hearts? New insights in right ventricular function supported by myocardial imaging echocardiography. Heart Fail Rev. 2010;15(1):39–61. doi: 10.1007/s10741-009-9154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tello K, Gall H, Richter M, et al. Right ventricular function in pulmonary (arterial) hypertension. Herz. 2019;44(6):509–516. doi: 10.1007/s00059-019-4815-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, et al. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):802–810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell C, Rahko PS, Blauwet LA, et al. Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transthoracic echocardiographic examination in adults: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019;32:1–64. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badano LP, Kolias TJ, Muraru D, et al. Standardization of left atrial, right ventricular and right atrial deformation imaging using two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography: a consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/industry task force to standardize deformation imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19(6):591–600. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.T. C. Ministry of Health General Directorate of Public Health (2020) Covid-19 (Sars-Cov2 Infection) directory, coronavirus scientific advisory board, Turkey

- 18.Wu Q, Zhou L, Sun X, et al. Altered lipid metabolism in recovered SARS patients twelve years after infection. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9110. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09536-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alhogbani T. Acute myocarditis associated with novel Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Ann Saudi Med. 2016;36(1):78–80. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2016.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, et al. Acute myocardial infarction after laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):345–353. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kytömaa S, Hegde S, Claggett B, et al. Association of influenza-like illness activity with hospitalizations for heart failure: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(4):363–369. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cangemi R, Calvieri C, Falcone M. Relation of cardiac complications in the early phase of community-acquired pneumonia to long-term mortality and cardiovascular events. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(4):647–651. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madjid M, Miller CC, Zarubaev VV, et al. Influenza epidemics and acute respiratory disease activity are associated with a surge in autopsy-confirmed coronary heart disease death: results from 8 years of autopsies in 34 892 subjects. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(10):1205–1210. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrales-Medina VF, Alvarez KN, Weissfeld LA, et al. Association between hospitalization for pneumonia and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2015;313(3):264–274. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.18229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park JF, Banerjee S, Umar S. In the eye of the storm: the right ventricle in COVID-19. PulmCirc. 2020;10(3):2045894020936660. doi: 10.1177/2045894020936660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchiano S, Hsiang TY, Higashi T, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infects human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, impairing electrical and mechanical function. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.30.274464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franchini M, Marano G, Cruciani M, et al. COVID-19-associated coagulopathy. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7(4):357–363. doi: 10.1515/dx-2020-0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carsana L, Sonzogni A, Nasr A, et al. Pulmonary post-mortem findings in a series of COVID-19 cases from northern Italy: a two-centre descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(10):1135–1140. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30434-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menter T, Haslbauer JD, Nienhold R, et al. Postmortem examination of COVID-19 patients reveals diffuse alveolar damage with severe capillary congestion and variegated findings in lungs and other organs suggesting vascular dysfunction. Histopathology. 2020;77(2):198–209. doi: 10.1111/his.14134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Speich R, Jenni R, Opravil M, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension in HIV infection. Chest. 1991;100(5):1268–1271. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.5.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cool CD, Rai PR, Yeager ME, et al. Expression of human herpesvirus 8 in primary pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(12):1113–1122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Humbert M, Guignabert C, Bonnet S, et al. Pathology and pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension: state of the art and research perspectives. EurRespir J. 2019;53(1):1801887. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01887-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Potus F, Mai V, Lebret M, et al. Novel insights on the pulmonary vascular consequences of COVID-19. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020;319(2):L277–L288. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00195.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng MY, Ferreira VM, Leung ST, et al. Patients recovered from COVID-19 show ongoing subclinical myocarditis as revealed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(11):2476–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puntmann VO, et al. Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahmoud-Elsayed HM, Moody WE, William M, et al. Echocardiographic findings in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(8):1203–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szekely Y, Lichter Y, Taieb P, et al. The spectrum of cardiac manifestations in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—a systematic echocardiographic study. Circulation. 2020;142(4):342–353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dweck MR, Bularga A, Hahn RT, et al. Global evaluation of echocardiography in patients with COVID-19. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeaa178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krishnamoorthy P, Croft LB, Ro R, et al. Biventricular strain by speckle tracking echocardiography in COVID-19: findings and possible prognostic implications. Future Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.2217/fca-2020-0100.10.2217/fca-2020-0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Li H, Zhu S. Prognostic value of right ventricular longitudinal strain in patients with COVID-19. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(11):2287–2299. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baycan OF, Barman HA, Atici A, et al. Evaluation of biventricular function in patients with COVID-19 using speckle tracking echocardiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;15:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10554-020-01968-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]