Abstract

Background and purpose

In the 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of central nervous system tumours, brain invasion was added as an independent histological criterion for the diagnosis of a World Health Organization grade II atypical meningioma. The aim of this study was to assess whether magnetic resonance imaging characteristics can predict brain invasion for meningiomas.

Materials and methods

We conducted a retrospective review of all meningiomas resected at our institution between 2005 and 2016 which had preoperative magnetic resonance imaging and included brain tissue within the pathology specimen. One hundred meningiomas were included in the study, 60 of which had histopathological brain invasion, 40 of which did not. Magnetic resonance imaging characteristics of tumours were evaluated for potential predictors of brain invasion. Tumour location, size, perilesional oedema, contour, cerebrospinal fluid cleft, peritumoral cyst, dural venous sinus invasion, bone invasion, hyperostosis and the presence of enlarged pial arteries and veins were evaluated. Data were analysed using conventional chi-square, Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression.

Results

The volume of peritumoral oedema was significantly higher in the brain-invasive meningioma group compared to the non-brain-invasive group. The presence of a complete cleft was a rare finding that was only found in non-brain-invasive meningiomas. The presence of enlarged pial feeding arteries was a rare finding that was only found in brain-invasive meningiomas.

Conclusions

An increased volume of perilesional oedema is associated with the likelihood of brain invasion for meningiomas.

Keywords: Meningioma, brain invasion, MRI

Introduction

Meningiomas are common and account for 16–20% of primary intracranial tumours.1 Although the vast majority are histopathologically benign, 4.7% to 7.2% have been characterised as atypical,2 with an increased propensity for recurrence. As per the 2016 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of central nervous system (CNS) tumours, brain invasion joins a mitotic count of 4 or more as a histological criterion that suffices by itself for the diagnosis of an atypical meningioma, WHO grade II.3 The association of brain invasion with additional histopathological criteria of atypia have been reported, thus leading to a worse prognosis in some cases.4 The identification of atypical meningiomas would be useful for determining prognosis, surgical planning and post-treatment follow-up. Although previous studies have discussed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques to differentiate typical from atypical meningiomas, most of them referred to the former 2007 WHO classification for histological diagnosis,5,6 which did not include brain invasion as a histological criterion. Only a few studies specifically assessed imaging findings of brain-invasive and non-invasive meningiomas.7,8 We conducted a retrospective cohort study to assess whether MRI characteristics could predict brain invasion for meningiomas, which is an added criterion for upstaging in the revised 2016 WHO classification of tumours.9

Materials and methods

Subjects

We retrospectively reviewed all resected meningiomas at our institution from 2005 to 2016. Records were obtained from the hospital pathology database by searching for the diagnosis of meningiomas. Inclusion criteria were: (a) pathology specimen contained meningioma and brain tissue; and (b) patient had preoperative MRI. Patients with previous surgical resection for the same tumour were excluded. A total of 100 meningiomas were included in the study.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Studies were performed using 1.5 T (Philips Achieve dStream Ingenia, dStrheadspine coil) or 3 T (Siemens Skyra, head/neck 20 coil) magnetic resonance clinical scanners using a standard head coil. Conventional magnetic resonance images were acquired using a brain tumour protocol consisting of T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) (1.5 T: TR 11 ms, TE 4 ms, field of view (FOV) 220 mm, ST 2.2 mm; 3T: TR 2890 ms, TE 10 ms, FOV 240 mm, ST 4 mm); T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) (1.5 T: TR 5991 ms, TE 110 ms, FOV 200 mm, ST 5 mm; 3T: TR 6000 ms, TE 100 ms, FOV 200 mm, ST 5 mm), fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (1.5 T: TR 11000 ms, TI 2800 ms, TE 140 ms, FOV 200 mm, ST 5 mm; 3T: TR 9000 ms, TI 2500 ms, TE 81 ms, FOV 200 mm, ST 5 mm); diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) (1.5 T: TR 3751 ms, TE 72 ms, FOV 230 mm, ST 5 mm; 3T: TR 5700 ms, TE 64 ms, FOV 220 mm, ST 5 mm); and gadolinium-enhanced T1WI (contrast agent: Bracco Prohance; 1.5 T: TR 9.9 ms, TE 4.6 ms, FOV 256 mm, ST 1 mm; 3T: TR 2300 ms, TE 3.6 ms, FOV 240 mm, ST 0.9 mm).

Image analysis

A neuroradiologist with 3 years of experience and a neuroradiology fellow reviewed the images on a PACS workstation. The magnetic resonance images were evaluated for tumour location, size, perilesional oedema, contour, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cleft, peritumoral cyst, dural venous sinus invasion, bone invasion, bone hyperostosis, the presence of grossly enlarged arteries that normally supply the brain parenchyma and the presence of adjacent enlarged cortical or transmedullary veins. Tumour volume (TV) was calculated as an ellipsoid volume based on the three-axis diameter measured on a workstation (L×W×H × Pi/6). Oedema volume (OV) was calculated as an ellipsoid volume of oedema encompassing the tumour minus the TV. The neuroradiologist and the neuroradiology fellow did measurements for the first few cases together to ensure consistency, and then each did half of the rest of the cases on a PACS workstation. A consensus read was done whenever one of the readers had doubt about a measurement. The readers were blinded to the final histopathological diagnosis of the presence or absence of brain invasion at the time of data collection. Tumour contour was characterised as either smooth, macrolobulated (lobulations >3 mm), or microlobulated (lobulations <3 mm). A CSF cleft was defined as space between the tumour and the brain parenchyma that had the same signal as CSF (i.e. hyperintense on T2WI with signal suppression on FLAIR). A complete CSF cleft was defined as CSF completely surrounding the tumour margins without discontinuity. Assessment of feeding arteries or drain veins was done when there was vascular imaging available, which included 52 cases. Twenty-four cases had dedicated computed tomography venogram (CTV)/magnetic resonance venogram (MRV), 14 cases had dedicated computed tomography angiogram (CTA)/magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA), and the rest had good quality thin slice post-contrast computed tomography (CT) in which the vessels can be clearly seen. Enlarged pial arteries were defined as prominent arteries entering the tumour that can be traced back as an arterial branch that normally supplies the brain. Dural sinus invasion was defined as tumour infiltrating or encasing adjacent dural sinuses. Bone hyperostosis was defined as broadening of bone with increased density. Bone invasion was defined as enhancing tumour infiltrating bone. Tumour location was noted as skull base or hemispheric.

Pathological diagnosis

All patients underwent surgery for tumour resection. Histopathological diagnosis was performed by an experienced neuropathologist. The presence of brain tissue in the specimen and the presence of brain tissue invasion were noted in the pathology report. Histological definition of brain invasion was defined as the presence of meningioma tissue within the adjacent brain without a separating connective tissue layer.10

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Professional Software (JMP; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Continuous variables were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Discrete variables were presented as the frequency distribution. The mean values were compared using a two-sample independent t-test. Categorical variables were compared using conventional chi-square and Fisher’s exact testing. Logistic regression was performed to determine the predictors of histopathological brain invasion (Table 1). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 1.

Independent predictors of brain invasion. Logistic regression.

| OR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OV | 1.007252 | 1.000594–1.013953 | 0.0211* |

| Oedema ratio | 1.072561 | 0.959377–1.199098 | 0.1713 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; OV: oedema volume.

Results

Patients and MRI characteristics are shown in Table 2. The 100 patients included 37 men and 63 women (mean age 60.4 years, range 31–91 years). Sixty (60%) patients had brain-invasive meningioma and 40 (40%) had non-brain-invasive-meningioma. The mean TV for brain-invasive meningioma was not significantly larger than the non-brain-invasive meningioma volume (45.35 ± 54.1 cm3 vs. 33.99 ± 28.5 cm3, P=0.17). Irregular tumour margins, peritumoral cyst, dural sinus invasion, the presence of adjacent prominent cortical or transmedullary veins, bone invasion, hyperostosis, age and gender were not significantly different between the two groups.

Table 2.

Conventional MRI characteristics evaluated for prediction of brain invasion.

| No invasion | Invasion | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 40 | 60 | |

| Gender: male | 18 (45%) | 19 (31.7%) | 0.18 |

| Age (years) | 58.6±13.9 | 62.4±13.9 | 0.18 |

| Margins lobulated | 31 (77.5%) | 48 (80.0%) | 0.76 |

| Microlobulations | 21 (55.3%) | 28 (47.5%) | 0.31 |

| Macrolobulations | 30 (78.9%) | 46 (78.0%) | 0.91 |

| Cleft present | 19 (47.5%) | 22 (36.7%) | 0.36 |

| Complete cleft | 3 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.06 |

| Bone invasion | 3 (7.7%) | 10 (16.7%) | 0.22 |

| Hyperostosis | 10 (25.0%) | 17 (28.3%) | 0.57 |

| Dural sinus invasion | 8 (20.0%) | 5 (0.8%) | 0.25 |

| Peritumoral cyst | 5 (13.5%) | 25 (41.7%) | 0.75 |

| Location skull base vs. other | 7 (17.5%) | 9 (15%) | 0.74 |

| Enlarged pial feeding artery | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (15.2%) | 0.15 |

| Cortical or transmedullary vein | 10 (52.6%) | 13 (39.4%) | 0.36 |

| TV | 33.99±28.55 | 45.35±54.09 | 0.18 |

| OV | 48.97±56.30 | 81.61±79.46 | 0.02* |

| Oedema ratio (OV+TV)/TV | 3.24±4.26 | 4.46±4.82 | 0.19 |

TV: tumour volume; OV: oedema volume.

Continuous data are presented as means ± SD.

Discrete variables are presented as the frequency distribution.

*P<0.05.

OV was significantly higher in the brain-invasive meningioma group compared to the non-brain-invasive group (81.61 ± 79.46 vs. 48.97 ± 56.30 cm3, P=0.02). The oedema–tumour volume ratio (TV+OV)/TV was non-significant between the two groups 4.46 ± 4.82 (brain-invasive) versus 3.24 ± 4.26 (non-brain-invasive) (P=0.19). Thus, although a larger volume of peritumoral oedema was associated with an increased likelihood of brain invasion, no statistically significant difference was found when controlled for the size of tumour. The presence of a complete cleft (Figure 1) was found in no (0%) brain-invasive meningiomas versus three (0.8%) non-brain-invasive meningiomas.

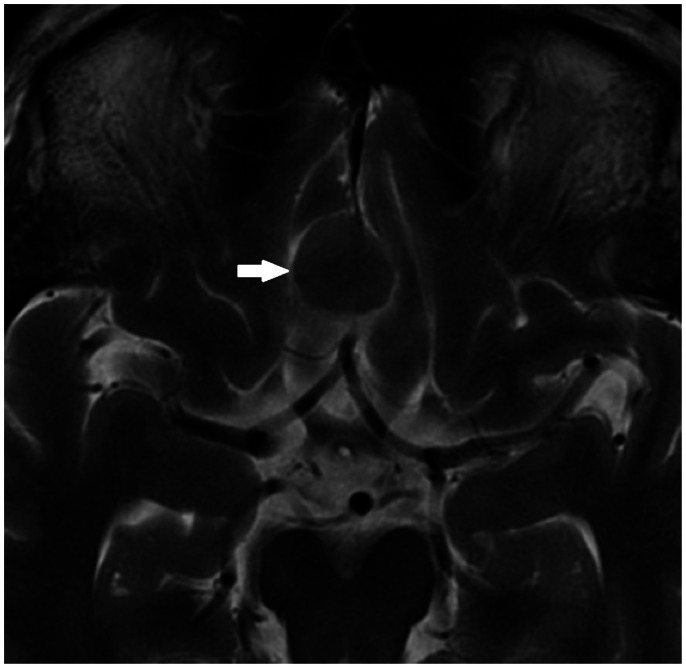

Figure 1.

The presence of a complete cleft was a rare finding that was only found in non-brain-invasive meningiomas in our case series.

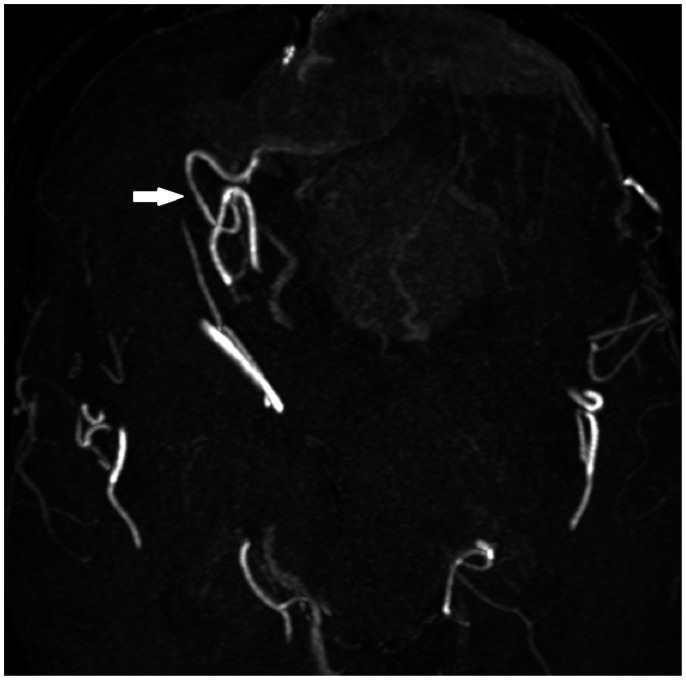

Assessment of pial feeding arteries and cortical veins was done when there was vascular imaging available which included 52 cases (19 without brain invasion, 33 with brain invasion). The presence of enlarged pial feeding arteries (Figure 2) was found in no (0%) non-brain-invasive meningiomas versus five (15.2%) brain-invasive meningiomas.

Figure 2.

The presence of enlarged pial feeding arteries was a rare finding that was only found in brain-invasive meningiomas in our case series.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we aimed to identify the MRI features which could predict brain invasion, which is a new criterion for upstaging meningiomas in the 2016 revision of the WHO classification of tumours.

Previous studies have shown correlation between atypical meningioma and male gender, TV, the presence of tumour necrosis, increased peritumoral oedema, irregular margins and diffusion restriction.2,11–21 However, no imaging finding was found to predict reliably the histological grade for meningioma.5,6,19 To our knowledge, this is the largest case series examining imaging findings of brain-invasive meningiomas, which included 60 such cases. Two previous studies which examined meningioma brain invasion found a positive association with peritumoral oedema, similar to our result. Adeli et al.7 analysed 617 cases of meningioma including 24 with brain invasion, and found increasing OV to be the only predictor of brain invasion on multivariable analyses, similar to our result. Mantle et al.8 found the chance of brain invasion to increase by 20% for each centimetre of oedema on CT. Another previous study of benign meningioma with brain invasion observed typical MRI characteristics in these cases (convexity location, extensive dural base and dural tail, minimal boundary between the tumour and neighbouring brain cortex, apex of the tumour enwrapping normal brain tissue and associated vessels), but made no comparison of these characteristics with non-invasive meningiomas.22 The spoke-wheel or sunburst sign (related to the characteristic vascular supply pattern with arteries extending outwards from the site of dural attachment) is helpful for the diagnosis of meningioma; however, it has not been reported to our knowledge to be correlated with the grade of meningioma. Hyperostosis associated with meningiomas is a frequently observed finding which has been found to have an association with tumour bone invasion.23,24

Our study demonstrated a statistically significant association between OV and brain invasion. OV tended to be higher in the brain-invasive group 81.61 ± 79.46 cm3 versus the non-brain-invasive group 48.97 ± 56.30 cm3 (P=0.02). Although peritumoral brain oedema is frequent, affecting 38–67% of intracranial meningiomas,25 its pathogenesis remains to be debated, as mentioned in previous studies, including compression of brain parenchyma due to tumour size, secretory–excretory histological subtype of meningiomas, variation in permeability of tumoral vessels with proliferation of vascular supply.25,26 The association between brain invasion and perilesional oedema suggests that it is a factor contributing to this phenomenon. However, the absence of perilesional oedema does not guarantee the absence of brain invasion, as five tumours in our series showed brain invasion despite lack of peritumoral oedema.

A complete peritumoral CSF cleft on MRI was an uncommon finding in our study, which is likely to be related to our patient selection, which only included pathological specimens that had brain tissue. Nevertheless, when a complete CSF cleft was present, there was absence of brain invasion. All three cases with complete CSF cleft showed no brain invasion on pathological analysis; conversely, none of the specimens showing brain invasion had a complete CSF cleft. This finding is perhaps not surprising, as CSF cleft on MRI is expected to correspond to an arachnoid plane between the tumour and the brain. On the other hand, the presence of an incomplete CSF cleft did not show significant correlation with the presence or absence of brain invasion.

Pial blood supply of meningiomas has frequently been observed in cerebral angiography and is thought to reflect a close spatial relationship between the tumour and the adjacent brain parenchyma. Several studies have reported an association between pial blood supply on cerebral angiography and the presence of peritumoral oedema.12,18,27,28 In this case series in which CTA/MRA is available, the presence of grossly enlarged pial arteries feeding the tumour was an uncommon finding observed only in brain-invasive meningiomas (present in five cases of brain-invasive meningiomas, and present in none of the non-brain-invasive meningiomas). This association may reflect the increased propensity of meningiomas with brain invasion to parasitise pial supply in addition to the more common dural supply in the process of tumour neoangiogenesis.

In this study, irregular contours, volume of tumour, bone invasion, hyperostosis, enlarged cortical or transmedullary veins and location did not show a significant correlation with brain invasion (Table 2).

Our study had several limitations. It was a retrospective study assessing only those meningiomas that were surgically resected with brain tissue in the specimen. This was a necessary requirement because without brain tissue in the sample, the tumour–brain interface cannot be examined for invasion. However, there is a risk of surgical sampling error (i.e. the area of invasion may not have been resected) which could result in underreporting of invasion. In addition, the sample has potential bias towards more adherent tumours because one would not expect brain to be included in a surgical sample unless the tumour was stuck to the brain at the time of surgery. Previous studies have reported varying frequencies of brain invasion in surgically removed meningiomas, probably due to differences in surgical and neuropathological practices.29,30 A large number of our cases (40 out of 100) demonstrated brain invasion, probably reflecting an increased likelihood for larger and more aggressive tumours to undergo surgical resection. Although having a complete CSF cleft on MRI was only found in the absence of brain invasion, only a small number of patients (three) had that finding. Grossly enlarged pial arteries are an uncommon finding on preoperative cross-sectional imaging, the presence of which was only found with brain invasion in this case series. A larger study needs to be performed to confirm the predictive value of those criteria.

Conclusion

Although brain invasion is now part of the clinical staging of meningioma, MRI has limited ability to detect it. A larger volume of perilesional oedema is associated with an increased likelihood of brain invasion for meningiomas.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Aditya Bharatha https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7923-7865

Reema Alsufayan https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8243-5136

Amy Wei Lin https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2505-7340

References

- 1.Watts J, Box G, Galvin A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of meningiomas: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging 2014; 5: 113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chernov MF, Kasuya H, Nakaya K, et al. 1H-MRS of intracranial meningiomas: what it can add to known clinical and MRI predictors of the histopathological and biological characteristics of the tumor? Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2011; 113: 202–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson DR, Guerin JB, Giannini C, et al. 2016 Updates to the WHO Brain Tumor Classification System: what the radiologist needs to know. RadioGraphics 2017; 37: 2164--2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brokinkel B, Hess K, Mawrin C. Brain invasion in meningiomas – clinical considerations and impact of neuropathological evaluation: a systematic review. Neuro Oncol 2017; 19: 1298--1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toh CH, Castillo M, Wong AMC, et al. Differentiation between classic and atypical meningiomas with use of diffusion tensor imaging. Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 1630--1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hou W, Ma Y, Xing H, et al. Imaging characteristics and surgical treatment of invasive meningioma. Oncol Lett 2017; 13: 2965--2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adeli A, Hess K, Mawrin C, et al. Prediction of brain invasion in patients with meningiomas using preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. Oncotarget 2018; 9: 35974–35982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mantle RE, Lach B, Delgado MR, et al. Predicting the probability of meningioma recurrence based on the quantity of peritumoral brain edema on computerized tomography scanning. J Neurosurg 1999; 91: 375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 2016; 131: 803--820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry A, Stafford SL, Scheithauer BW, et al. Meningioma grading: an analysis of histologic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol 1997; 21: 1455--1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hale AT, Wang L, Strother MK, et al. Differentiating meningioma grade by imaging features on magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Neurosci 2018; 48: 71--75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KJ, Joo W, II, Rha HK, et al. Peritumoral brain edema in meningiomas: correlations between magnetic resonance imaging, angiography, and pathology. Surg Neurol 2008; 69: 350--355; discussion 355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakyemez B, Yıldırım N, Gokalp G, et al. The contribution of diffusion-weighted MR imaging to distinguishing typical from atypical meningiomas. Neuroradiology 2006; 48: 513--520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Surov A, Ginat DT, Sanverdi E, et al. Use of diffusion weighted imaging in differentiating between maligant and benign meningiomas. A multicenter analysis . World Neurosurg 2016; 88: 598--602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kane AJ, Sughrue ME, Rutkowski MJ, et al. Anatomic location is a risk factor for atypical and malignant meningiomas. Cancer 2011; 117: 1272--1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasuya H, Kubo O, Tanaka M, et al. Clinical and radiological features related to the growth potential of meningioma. Neurosurg Rev 2006; 29: 293--296; discussion 296-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu CC, Pai CY, Kao HW, et al. Do aggressive imaging features correlate with advanced histopathological grade in meningiomas? J Clin Neurosci 2010; 17: 584--587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pistolesi S, Fontanini G, Camacci T, et al. Meningioma-associated brain oedema: the role of angiogenic factors and pial blood supply. J Neurooncol 2002; 60: 159--164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagar VA, Ye JR, Ng WH, et al. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging: diagnosing atypical or malignant meningiomas and detecting tumor dedifferentiation. Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 1147--1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawahara Y, Nakada M, Hayashi Y, et al. Prediction of high-grade meningioma by preoperative MRI assessment. J Neurooncol 2012; 108: 147--152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santelli L, Ramondo G, Della Puppa A, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging does not predict histological grading in meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010; 152: 1315--1319; discussion 1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin Q, Ling F, Xu G. Invasive benign meningioma: clinical characteristics, surgical strategies and outcomes from a single neurosurgical institute. Exp Ther Med 2016; 11: 2537--2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goyal N, Kakkar A, Sarkar C, et al. Does bony hyperostosis in intracranial meningioma signify tumor invasion: a radio-pathologic study. Neurol India. 2012; 60: 50–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pieper DR, Al-Mefty O, Hanada Y, et al. Hyperostosis associated with meningioma of the cranial base: secondary changes or tumor invasion. Neurosurgery 1999; 44: 742–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berhouma M, Jacquesson T, Jouanneau E, et al. Pathogenesis of peri-tumoral edema in intracranial meningiomas. Neurosurg Rev. 2019; 42(1): 59–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakano T, Asano K, Miura H, et al. Meningiomas with brain edema: radiological characteristics on MRI and review of the literature. Clin Imaging 2019; 42: 59--71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ildan F, Tuna M, Gocer AP, et al. Correlation of the relationships of brain-tumor interfaces, magnetic resonance imaging, and angiographic findings to predict cleavage of meningiomas. J Neurosurg 1999; 91: 384--390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bitzer M, Wöckel L, Luft AR, et al. The importance of pial blood supply to the development of peritumoral brain edema in meningiomas. J Neurosurg 1997; 87: 368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brokinkel B, Stummer W. Brain invasion in meningiomas: the rising importance of a uniform neuropathologic assessment after the release of the 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Central Nervous System Tumors. World Neurosurg 2016; 95: 614–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pižem J, Velnar T, Prestor B, et al. Brain invasion assessability in meningiomas is related to meningioma size and grade, and can be improved by extensive sampling of the surgically removed meningioma specimen. Clin Neuropathol 2014; 33: 354–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]