Abstract

Background: The spread of coronavirus (COVID-19) has resulted in a drastic alteration to billions of individuals’ emotional, physical, mental, social, and financial status. As of July 21st, 2020, there had been 14.35 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 0.60 million deaths in 216 countries.

Design and Methods: The study explores health and wellbeing in universities within the G20 countries (19 member countries and the European Union) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The sample selection of these countries was considered since it serves around 80% of the world’s economic output, two-thirds of the global population (including more than half of the world’s poor), and 75% of international trade. Specifically, due to this public health concern, schools’ nationwide closures are impacting over 60% of the world’s student population to promote their quality of life and well-being.

Results: This study investigates the G20 policies and procedures within higher education regarding health and well-being measures during the COVID-19 epidemic. The findings reveal that the lockdown, social distancing, and self-isolation requirements are stressful and detrimental for many individuals and have caused students’ health and well-being concerns.

Conclusions: Several countries within the G20 have taken significant steps to support health and well-being issues for university students; however, numerous countries are far behind in addressing this issue. Hence, government leaders of G20 countries, policymakers, and health providers should promptly take the necessary measures to regulate the outbreak, improve safety measures to decrease disease transmission, and administer those who demand medical attention.

Significance for public health.

Mental health and well-being during the covid-19 pandemic in higher education is critical to be investigated as it influences hundreds of millions of instructors’ and students. The study reveals that government leaders of G20 countries, policymakers, and health providers should promptly take the necessary measures to regulate the outbreak, improve safety measures to decrease disease transmission, and manage those who demand medical attention.

Key words: COVID-19, coronavirus, universities, students, G20, higher education, health and well-being

Introduction

The COVID-19 epidemic in early 2020 resulted in a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and led to the closure of schools, malls/shopping centres, restaurants, sports venues, and many public areas. Sixty-one countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, North, and South America have announced school closures and are forced to convert to online teaching platforms on March 13th, 2020.1 This worldwide decision by the countries’ governors was made to limit the increase and transmission of this virus outbreak and promote social distancing for health and safety purposes.

Although there is an apparent global effort to limiting the spread of COVID-19 using various protocols, the emotional, physical, psychological, social, and financial status of billions of people has been dramatically affected. Mental health, specifically, plays a significant role in students’ well-being and is defined as “emotional resilience that enables [them] to enjoy life and to survive pain, disappointment, and sadness, and an underlying belief in [their] own, and others’ dignity and worth.” Students who face mental health issues suffer from a lack of engagement and productivity in contributing to society or their community. Mental wellbeing is primarily related to the health of one’s physical, social, and spiritual status.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) stated that “the psychological impacts for these populations can include anxiety and feeling stressed or angry”. These are a few of many other health concerns that challenge students and teachers and distract from their lives within higher education.3 To prevent or limit the psychological impact that outbreaks can inflict on people, especially students, teachers, and their families, Lima et al.4 assert that further research and much work needs to be dedicated to examining the factors and direct and indirect effects of health issue cases.

While there are numerous reported infected and/or affected worldwide cases related to health and well-being, this paper is only concerned with the Group of Twenty (G20), which has prepared robust responses to health and well-being. The G201 is the leading medium for international economic assistance on macrofinancial issues and was developed in 1999 to manage risks of a global breakdown at the level of finance ministers and central bank governor.5 The G20 gathers the leaders of both developed and developing countries from every continent, which contains 19 member countries plus the European Union.5 The G20 countries are Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Republic of Korea, KSA, UK, US, India, Indonesia, Argentina, Brazil, China, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, and Turkey.

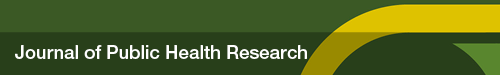

Besides, the United Nations’ 2030 agenda for sustainable development encompasses 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDG 3 deals directly with Good Health and Wellbeing. As a result of setting such ambitious goals, countries worldwide have included well-being into multiple policies to try to achieve the SDGs by 2030. Figure 1 shows the correspondence between G20 summit commitments and SDG 3 targets and principles. Seven of nine health targets were coloured in red, indicating no direct commitment by the G20 from 2015 to 2017. On March 26, G20 leaders held an extraordinary summit regarding health, focusing on COVID-19 consequences, the severe economic influence, the necessary public health efforts, and financial rules.6 The G20 Leaders’ Summit called for “a transparent, robust, coordinated, large-scale, and science-based global response in the spirit of solidarity to combat this pandemic” (p. 61).6 The Summit provided a broad convergence of plans that evidence knowledge-based data, including discussing all urgent health concerns and seeking to confirm adequate financing to manage the pandemic and protect people, especially those at risk.7 This global response has shaped the traditional patterns of disease spread (i.e., Italy and China), and the evolution and habitual responses of health systems.8

With the following, we mainly explore the G20 robust policies, initiatives, recommendations, and procedures within higher education regarding health and well-being responses and measures during the COVID-19 pandemic. A particular emphasis was paid to the US, the UK and Australia as examples of strict policy implementation. We look closely at policy related to the medical care of students whether or not they are infected. We also are concerned with policies regarding financial, social, and physical developments and safeguards for low income or students at risk. Further factors that can improve their long-term well-being are also examined and explored within this paper.

The G20 responses and recommendations related to mental health and well-being

The COVID-19 outbreak has impacted negatively on college students globally who encounter poor mental health.9 In the US, the COVID-19 Pandemic’s New Epicenter, a devoted Lifeline (the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline), was made available 24 hours a day for emotional distress related to COVID-19 to prevent suicide attempts as there were thousands of mental health cases reported.10 Furthermore, during the constraints of the pandemic outbreak in the US, the integration of telemedicine with in-person care was implemented to support low- and middle-income families. For example, university counselling centres offer options to support college students with health and emotional and mental counselling services and prescribe medicines remotely.11

In KSA, Meo et al.12 conducted a questionnaire study at public university and distributed among 625 medical students examining their psychological well-being and stress-related concerns regarding quarantine and learning behaviours. The findings of Meo et al.12 revealed that both female and male students have stated that quarantine has caused them to feel emotionally detached from family and friends and has negatively affected their overall work quality and study period. Similarly, in Australia, research developed by Wang et al.13 sought support and response to COVID-19 and encouraged the medical involvement and stakeholders for extraordinary measures, functional and training safeguards. Furthermore, Smith and Judd14 state that during the COVID-19 outbreak, many have suffered from the vulnerability of being underprivileged in the pandemic in Australia. They explained that many people in several countries have trouble accessing health services and essential primary health care. They said, “vulnerable populations may not have the necessary language and literacy skills to understand and appropriately respond to pandemic messaging” and that mental health concerns are the most practical issue among vulnerable communities. In their article, Smith and Judd14 urge governments to appropriately implement strategies that are primarily concerned with reducing health inequities through action and policy determinations of health and well-being.

By the same token, in China, results from Song et al.’s15 study showed that men are more likely to have depressive symptoms and PTSD. The researchers claim that females tend to pay more attention to their experiences and emotions and are more willing to express their feelings as self-regulation processes. Their study also revealed that gender, age, years working, daily work time, and social support affect mental health. Moreover, Montemurro10 argues that fear and anxiety of falling sick or dying are factors that might cause an increase in the 2020 suicide rates. In Italy, a survey was conducted among Italian undergraduates to examine their knowledge about COVID-19 and cope with behavioural attitudes during the lockdown. Gallè et al.16 revealed that students have a sufficient level of knowledge about COVID-19 and its control measures, and the research suggested restrictive measures and preventive interventions be further taught to students to increase the opportunity to improve their lifestyles. In the same line of thought, in the UK and the Republic of Ireland, a study was conducted to deliver anatomical education through online means from a collection of 14 different universities in the UK and Ireland.17 The findings of their result highlighted issues and challenges related to the quality and effectiveness of these resources, especially in educating students regarding health measures during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study urges for the need to facilitate decisions to be made by higher education institutions regarding the curriculum and assessment transformation to meet the students’ well-being and healthy measure expectations.17

Figure 1.

Correspondence between G20 summit commitments and SDG 3 targets and principles (2015-2017). Source: SDG Health Targets. Adapted from: Lucas B. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies; 2019.

Furthermore, Tashiro and Shaw18 analyzed the critical policy measures related to health and well-being in Japan and suggested several areas, including the healthcare system, sanitation, immunity, food habits, and citizens’ performances. Their findings showed that a combination of health and well-being policy and transparent guidance governance could lead to an ecosystem-based lifestyle that has the potential to allow individuals to cope with pandemic situations. Moreover, results from a study of a sample consisting of 1772 Turkish individuals (aged between 18 and 73 years) from 79 of 81 cities in Turkey showed that intolerance of uncertainty had a significant direct influence on mental well-being. Uncertainty may have also been generated by interruption of daily routine and interface social support instruments.19 The results from previously reviewed studies regarding the COVID-19 pandemic are concerning collegiate health. Well-being highlights the critical need to comprehend these challenges and concerns in order to plan and respond for better support of college students’ public health during and in the aftermath of this crisis.9 Furthermore, several types of online health services have been employed broadly for those in need during the outbreak. Digital health for mental health has recently become significant in meeting the demands of individuals facing anxiety and depression in quarantine,20,21 with social and physical distancing constraints, and a lack of in-person care. Liu et al.22 state that China has prepared “online mental health education with communication programmes” and these applications have been extensively used during the outbreak for medical staff and the public. Several books on COVID-19 prevention, guidelines, and mental health education have been expeditiously published, and free electronic copies have been provided for the public.22 Similarly, in Turkey, programs have been implemented in online settings, especially aiming towards at-risk groups. Also, audio and visual resources in which internal interchanges with and without meditation are played can be prepared and shared by counsellors.19 Djalante et al.23 argue that “artificial intelligence communication tools that are open for citizen-data can accelerate current responses,” as seen in countries such as Singapore, South Korea, and China that have provided aggressive monitoring through the use of these technologies.

A framework to guide an education response to COVID-19

A well-developed framework to guide an educational response to the COVID-19 pandemic was established by Reimers and Schleicher.24 This framework targets a steering committee that would have the responsibility to improve and employ the education response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, student wellbeing has become a focus of international education policy for global organisations such as the WHO, which identifies mental well-being as a fundamental component of good health and wellbeing and plans a comprehensive action plan that recognises the essential role of mental health in achieving health and well-being for all people. The main points from Reimers and Schleicher24 framework include: i) Ensuring diverse perspectives goals to meet the needs of various departments’ curricula, teacher education, information technology, teacher and parent representatives, and students; ii) Re-prioritising curriculum goals given the reality that the mechanisms of delivery are disruptive, and determining what should be learned during the period of social distancing; iii) Guiding the students in planned principles to protect students and staff’s health, ensuring academic learning, and offering emotional support to students and faculty; iv) Developing a direct and regular communication among educators and students during the period of social distancing to check up on their health and well-being; v) Offering guidance through multiple media (texts, phone calls, emails, and brochures) to students and families about the safe use of screen time and online tools to preserve student well-being and mental health and protect from online threats to minors and educational training;25 vi) Establishing tools of coordination with public health authorities so that education actions are in sync and aid/advance public health goals and strategies. As the pandemic has been accelerating and threatening individuals’ health across the globe, this study calls for careful adaptation of proven measures and procedures from the G20 countries that minimise the public well-being fear and limit the spectrum of psychological concerns. Furthermore, Song et al.15 argue that most health specialists working in separated units and hospitals very often do not get any training for offering mental health care. Training and educating health care providers are critical factors that impact individuals and societies as a whole. This paper provides recommendations and reports on careful implementations offered by higher education institutions and health specialists to address students’ and teachers’ health needs and well-being during the challenging time of the pandemic among the G20 countries. In the following, we focus on our research methodology, findings, and finally, conclude with our summary and current policy implications.

Design and Method

The study adopted a mixed methodology, which included a collection of documentary qualitative and quantitative analyses to ensure the validity of the findings of the study by Creswell and Clark.26 According to Moorley and Cathala,27 utilizing a mixedmethod can offer more-robust justifications to the research question. In terms of document analysis (qualitative analysis), Frey28 argued that document analysis is another type of qualitative research, which requires repeated review, examination, and interpretation of the data. Documents may include text (words) and images that have been recorded without the intervention of the researchers.29 Therefore, a mixed-method is appropriate for enriching the evidence and enabling questions to be answered more deeply.30 In this study, documents were collected from all G20 countries, including documents of policy reports on health and well-being by government agencies, independent organizations, newspapers, and research papers. Some policy papers from several countries were written in the local language, and, therefore, such documents had to be translated into English through the use of official translators. In terms of qualitative analysis, since there is no well-being index for higher education, the study utilized the data of OECD’s well-being framework.31 As shown in Appendix 1, there are the following 11 parameters of OECD’s well-being framework: i) Income and wealth; ii) Work and job quality; iii) Housing; iv) Health; v) Education (knowledge and skills); vi) Environment Quality; vii) Safety; viii) Civic engagement; ix) Accessibility to services (work-life balance); x) Community (social connections); xi) Life satisfaction (subjective well-being). In particular, the study focuses on the data of Health and Life satisfaction (Subjective Well-being). The data represents 36 OECD countries. Globally, as of July 21, 2020, there had been 14,348,858 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 603,691 deaths, reported to the WHO. This study focused upon G20 countries because, collectively, G20 members (19 member countries and the European Union) represent around 80% of the world’s economic output, twothirds of the global population (including more than half of the world’s poor), and 75% of international trade.

Health and well-being in universities of G20 countries

G20 commitment to health and well-being

This relates to the health issues that have received the most consistent attention in the G20 Summit.32-38 Table 1 shows the G20 summit commitments on health from 2015 to 2019. It is found that Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), Health systems strengthening, Infectious Diseases, and Public health security/crises appeared more than two times over the last five G20 summits. Mainly, 30 or more commitments were declared by the G20 Summit in more than half of the summits since 201539 involve: i) Health systems strengthening; ii) Infectious diseases (including HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, polio, neglected tropical diseases, and vaccination); iii) Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR); iv) Public health crises (including emergency preparedness and response, global health security, global health architecture, International Health Regulations, pandemics, Ebola, and Zika).37

Importantly, mental health issues were addressed for the first time in the last G20 Summit in Japan in 2019. Table 2 shows the number of countries in compliance with selected G20 commitments in 2017 and 2018. The majority of commitments comply; however, the number of partial compliances increased from one (2017) to three (2018). According to Lucas (p. 2):37

“G20 summit declarations have tended to neglect non-communicable diseases, environmental pollution, tobacco control, substance abuse, road traffic morbidity and mortality, access to essential medicines via the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), and social issues such as equity and the social determinants of health (…), no specific references to gender were noted in G20 health-related commitments.”

Some G20 health commitments are not specific or measurable and hence accountability for the G20 member states is somewhat debatable.40 From the perspective of SDG 3, the G20’s commitments are less well aligned.39,41 Only 14 of 28 targets and principles are aligned with SDG 3.40

Table 1.

G20 summit commitments on health, 2015-2019.

| G20 Summit Commitments on Health | G20 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | |

| (Osaka) | (Buenos Aires) | (Hamburg) | (Hangzhou) | (Antalya) | |

| Antimicrobial resistance | 2 | 11 | 3 | 1 | |

| Disaster risk reduction and disaster response | |||||

| Health systems strengthening | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| Healthy and active ageing (including dementia) | 4 | ||||

| Infectious diseases (including HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and polio, neglected tropical diseases, and vaccination) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mental health | 1 | ||||

| Non-communicable diseases (including malnutrition, overweight, and obesity) | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||

| One Health approach/multi sectorial working (including One Health approach, agriculture, environment, and food safety) | 1 | ||||

| Primary health care (including social determinants of health) | 2 | ||||

| Public health security/crises (including emergency preparedness and response, global health security, global health architecture, International Health Regulations, pandemics, Ebola, and Zika) | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health (RMNCAH) | |||||

| Research and development | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Universal health coverage (including equity, access, and leave no-one behind) | 1 | ||||

| Women's and girls' health | |||||

| Other non-specific goals (including general expressions of support for health and the SDGs) | 1 | ||||

| Total | 22 | 5 | 25 | 4 | 4 |

Table 2.

Number of countries in compliance with selected G20 commitments.

| Summit | Commitment assessed | Full compliance | Partial compliance* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 (Buenos Aires) | Health systems are strengthening / Universal Health Coverage: We reaffirm the need for more-reliable health systems providing cost-effective and evidence-based intervention to achieve better access to health care and to improve its quality and affordability to move towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC), in line with their national contexts and priorities. | 17 | 3 |

| 2017 (Hamburg) | Health systems strengthening: We strive for cooperative action to strengthen health systems worldwide, including through developing the health workforce. | 19 | 1 |

COVID-19 and health and well-being for G20 countries’ universities

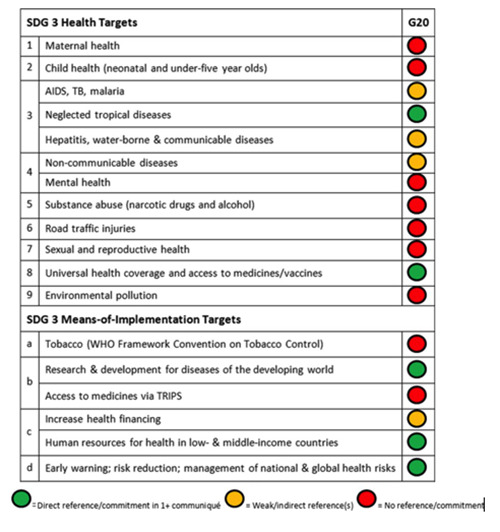

In response to COVID-19, the educational system witnessed the most significant disruption. According to the International Association of Universities,42 nationwide closures impacted 90% of the world’s student populations. The SDG-Education 2030 Steering Committee’s COVID-19 response statement has reemphasised the importance of governments’ role in educational continuity and inclusion.43 Furthermore, 10 countries are classified as high-income countries2 (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Republic of Korea, KSA, UK, and the US), and seven of them are upper-middle-income countries (Argentina, Brazil, China, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, and Turkey). Only two countries are lower-middle-income countries: India and Indonesia (Figure 2). Better health and well-being are far lower in lowermiddle- income countries.40 According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD),31 the framework focuses on regional and local well-being. The framework is based on: i) What do people perceive and value regarding their local conditions? ii) How do people behave when they are not satisfied with one aspect or more of their life? iii) Do local inequalities in the accessibility of services matter in shaping citizens’ choices, and do they impact national well-being? iv) How much does the place where we live predict our future well-being?

For each topic, a score on a scale from 0 to 10 is attributed to the region based on one or more indicators. A higher score indicates better performance in a topic relative to all the other regions. The min-max formula is applied:

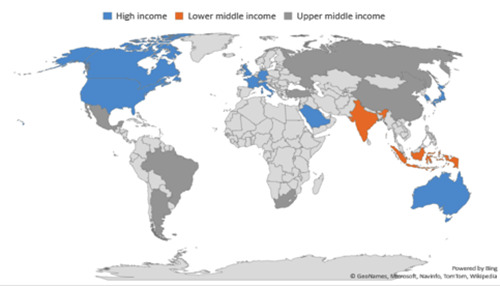

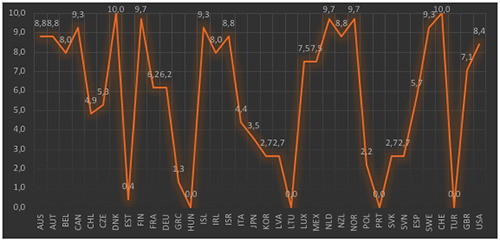

Health is one of the well-being index indicators, and Figure 3 shows lots of disparities in the perceived health indicators. For instance, 9 countries scored below 4 (Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Mexico, Slovak Republic, Poland, Estonia, US, Turkey). Two countries scored a maximum of 10 (Switzerland and Japan).

Figure 4 shows subjective well-being, which is another indicator of the well-being index. Two countries, namely Denmark and Switzerland, achieved the maximum score of 10. Interestingly, 25% of countries scored 9 and above (Denmark, Switzerland, Finland, Netherlands, Norway, Canada, Iceland, and Sweden). Comparing to health indicators, only 19% of countries scored 9 and above. Specifically, there is no correlation between countries with higher scores in health and countries with higher well-being scores. Hungary and Latvia were the lowest in terms of scores in both health and well-being (Figure 5). The mean of health is 6.657 (with SD of 2.747), which is higher than the mean of well-being of 5.988 (with SD of 3.369) (Table 3). The correlation between health and well-being is 0.433. A repeated-measures t-test found this difference to be not significant, t(34) = 1.200, p>0.001 (Tables 3 and 4). Higher education institutes’ response to COVID-19 is highly dependent on the presence of university and country policies before the emergence of the pandemic. In the following cases, the US, the UK, and Australia highlight the role of policy beyond the SDG3 objective and its effect on the COVID-19 response.

Figure 2.

Income classification of G20 countries.

Figure 3.

OECD well-being index (Health) (n=36).

Figure 4.

OECD well-being index (subjective well-being) (n=36).

Table 3.

Paired samples statistics.

| Mean | n | Standard deviation | Standard error mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pair 1 | Health | 6.657 | 35 | 2.747 | 0.46444 |

| Well-being | 5.988 | 35 | 3.369 | 0.56946 |

The United States

In the US, universities’ autonomous nature has made student mental health and well-being the responsibility of the institution itself. The healthy minds study providing national data over 10 years showed an increase in the use of mental health services by college students in the US. This study highlighted the rise in mental health facility needs as well as a decrease in the stigma surrounding mental health Lipson et al.44

In order to treat the increase in mental health issues among students and improve mental health services, a bill was proposed to Congress. The Higher Education Mental Health Act of 2019 was introduced to the House and referred to the House Committee on Education and Labor in June of 2019.3 This bill entails establishing an advisory commission on serving and supporting students with mental health disabilities in higher education institutions.

Multiple organisations conducted surveys on different aspects of the educational system to get a better understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on mental health and well-being in higher education. Although individual school efforts have been made for engrossing the effect of COVID-19, no apparent mental health or well-being policy has been implemented.

The American Council on Education’s (ACE) report in light of COVID-19 university leaders should focus on communication with and amongst students; the mental health and well-being of all campus stakeholders; and the assessment of the mental health needs of the institution.45

Institute of International Education (IIE) surveyed “COVID- 19 effects on higher education campuses in the US; the survey highlights the toll COVID-19 had on the physical and emotional well-being of their students and the measures taken in response, such as 76% provided mental health support specifically for COVID-19, 70% set up COVID-19 student necessity/emergency funds and 54% provided alternative housing for students outside of campus. “Several institutions indicated setting up emergency funds for faculty and staff affected by COVID-19, and additional support for students and faculty for health insurance, and food supplies.”46

Figure 5.

Comparison of health and well-being of OECD countries (n=36).

Table 4.

Paired samples test.

| Paired differences | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard deviation | Standard error mean | 95% Confidence | ||||||

| interval of the difference | |||||||||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Pair 1 | Health – Well-being | 0.6688 | 3.298 | 0.557 | -0.464 | 1.801 | 1.200 | 34 | 0.239 |

United Kingdom

The UK has made mental health and well-being a national priority. There have been multiple national initiatives focused on well-being, which lead to the incorporation of well-being for all ages and multiple lives. Some of their efforts include: i) Cross Government Wellbeing Policy Steering Group; ii) Cross Government Social Impacts Task Force; iii) ONS Measuring National Wellbeing (MNW) programme; iv) Legatum Institute Commission; v) ‘What Works’ Centre on well-being.47

In the UK, GuildHE and Universities UK (UUK) are recognised representatives for the UK body of higher education. In 2006, the UUK/GuildHE Mental Wellbeing in Higher Education Group published a framework for institutional mental health policy. The framework was student mental well-being in higher education. 48 Across the UK, universities that are part of the GuildHE or UUK have implemented a well-being/mental health strategy or policy publicly available. The UUK also adopted a whole university approach in 2016, which recommends that all aspects of university life promote and support student and staff mental health. In May of 2020, UUK published a revised version of its report Stepchange: Mentally Healthy Universities as a call to action and a shared framework for change.49

While some universities implemented fast responses to the mental health and well-being needs of its students, the Office for Students (OfS) curated a list of these universities.4 National Mental health and Well-being resources were made available to the students on the UUK,5 GuildHE6 as well as the OfS7 websites.

Universities UK8 is providing a series of webinars by UUK addressing the immediate and longer-term impacts of COVID-19 on the safety, health, and well-being of students and staff in higher education institutions. According to Universities UK, “We will offer strategic insight and a practical response to facilitate universities in developing effective interventions and mandatory actions in this rapidly developing situation. There would be an opportunity to explore the needs of students and staff post-lockdown and preparations for the next academic year.”

Australia

Australia has been dedicated to the nation’s mental health and well-being by applying the National Mental Health Policy and through the establishment of the National Mental Health Commission.50 They have multiple national well-being strategies, including: i) National children’s mental health and well-being strategy; ii) National mental health and research strategy; iii) National Suicide and Self-harm Monitoring system; iv) National workplace initiative; v) National Women’s Health Policy; vi) Housing, Homeless and mental health.

In Australia, multiple education-specific Australian Frameworks are aligned with health and well-being to promote: i) National Safe Schools Framework; ii) Australian Student Wellbeing Framework; iii) Learner Well-being Framework for Birth to Year 12; iv) The National Framework for Values Education in Australian Schools 2005; v) The National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing.

More recently, in 2020, Orygen, a non-profit research institute, issued a draft of the Australian University Mental Health framework. The framework’s objective is to create learning environments that have the potential to improve the inclusive quality of life for all within the university community.

Australia adopted The National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan in response to COVID-19. The plan focuses on mental health and well-being in the face of the pandemic. The government also established a higher education relief package supporting higher education to ensure the continuity of education. On the University level, individual universities have established COVID-19 response links on their websites, Facebook pages, and messaging apps to connect with their students. Universities also refer their students to the following initiative for maintenance or guidance of individual mental health and wellbeing: i) Beyond Blue – Coronavirus Mental Wellbeing Support Service; ii) Headspace: How to deal with stress related to COVID- 19; iii) Lifeline: Mental Health and Well-being during the COVID- 19 outbreak.

Conclusion and policy implications

The effects of COVID-19 (coronavirus) on global higher education campuses are undoubtedly significant. The current study aimed to assess university students’ health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in G20 countries. All G20 countries made the decision to end in-person instruction, moving student engagement to virtual communication. Most study abroad programmes were cancelled globally; international students were asked to return home. International students made difficult decisions about whether to stay in the host country or return to their home countries. Our analysis found that students’ health and wellbeing issues were not addressed in many G20 countries. Countries such as the US and the UK retorted to this issue. However, countries such as China, Indonesia, and India did not have any policy response to this critical issue.

Some policy responses should come from the government institutions and policymakers for health and well-being for students in universities: i) The G20 countries should make a declaration statement on health and well-being for education; ii) Each government of the G20 countries should provide some guidelines related to health and well-being; iii) The G20 countries should separate international students’ guideline on health and well-being where there are more international students (US, UK, China, Australia). This is because many students were returned to home countries during the pandemic, and this transition may significantly affect their daily routines; iv) Each university should also create a department/unit to support students’ health and well-being.

One of the limitations of the paper is the lack of availability of policy documents for many countries. The paper also utilised the OECD country data since health and well-being data for higher education is not available. Nevertheless, the country data may reflect the higher education sectors too, and hence future research could focus on a survey of a group of G20 countries’ higher education sectors. The results were gathered from websites such as the World Aquaculture Society (WAS), official higher education websites, official news, and research papers. Future studies might complement the current study by exploring other documented materials that might give an inner perspective of the given context. Future studies might also focus on an in-depth examination of local context by conducting interviews with key stakeholders from the G20 countries.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support from Prince Sultan University.

Footnotes

1The Group of Twenty, or the G20, is the leading forum for international economic cooperation. The G20 brings together the leaders of both developed and developing countries from every continent (https://g20.org/en/about/Pages/whatis.aspx).

2For the current 2020 fiscal year, low-income economies are defined as those with a GNI per capita, calculated using the World Bank Atlas method, of $1,025 or less in 2018; lower middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between $1,026 and $3,995; upper middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between $3,996 and $12,375; high-income economies are those with a GNI per capita of $12,376 or more (https://datahelpdesk.worldbank. org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country- and-lending-groups#:~:text=For%20the%20current%202020%20fiscal,those%20with%20a %20GNI%20per)

4 https://officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/coronavirus/coronavirus-case-studies/student-mental-health/

5https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/covid19/Pages/wellbeing.aspx

6 https://guildhe.ac.uk/coronavirus-general-information-and-guidance-for-members/

7 https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/media/f4e2522a-c1ba-42a2-9f86-6cc08d12ec3c/coronavirus-briefing-note-supporting-student-mental-health.pdf 8https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/events/Pages/Covid-19%20-%20safety,%20health%20and%20wellbeing%20webinar%20series.aspx

References

- 1.Lofgren ET, Rogers J, Senese M, Fefferman NH. Pandemic preparedness strategies for school systems: is closure really the only way? Anna Zool Fenn 2008;45:449–58. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Universities UK (2015). Student mental well-being in higher education | Good practice guide. London, February 13, 2015. Accessed June 15, 2020. Available from: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Pages/student-mental-wellbeing-in-higher-education.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Mental health and psychological resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020, March 27. Accessed June 18, 2020. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/mental-health-and-psychological-resilience-duringthe-covid-19-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lima CKT, Carvalho PM., Lima IAAS, et al. The emotional impact of Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (new Coronavirus disease). Psychiatry Res 2020;287:112915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fues T, Messner D. G20: Concert of great powers or guardian of global well-being? (No. 9/2016). Briefing Paper. Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn; 2016. Available from: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/199773/1/diebp-2016-09.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kickbusch I, Leung GM, Bhutta ZA, et al. Covid-19: how a virus is turning the world upside down. BMJ 2020;369:m1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.G20 Saudi Arabia. Extraordinary G20 Leaders' Summit. Statement on COVID-19; 2020. Accessed June 22, 2020. https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/100032142.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villa S, Lombardi A, Mangioni D, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic preparedness or lack thereof: from China to Italy. Global Health Med 2020;2:73–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhai Y, Du X. Addressing collegiate mental health amid COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiat Res 2020;288:113003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montemurro N. (2020). The emotional impact of COVID-19: From medical staff to common people. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:23–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorsey ER, Toprol EJ. Telemedicine 2020 and the next decade. Lancet. 2020;395:859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meo S, Abukhalaf D, Alomar A, et al. COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact of Quarantine on Medical Students’ Mental Wellbeing and Learning Behaviors. Pakistan J Med Sci 2020;36:S43–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Tan S, Raubenheimer K. Rethinking the role of senior medical students in the COVID-19 response. Med J Austral 2020;212:490–e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith J, Judd J. COVID-19: Vulnerability and the power of privilege in a pandemic. Health Promot J Austr 2020;31:158–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song X, Fu W, Liu X, et al. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the Coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:60-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallè F, Sabella E, Da Molin G, et al. Understanding knowledge and behaviors related to COVID-19 epidemic in Italian undergraduate students: The EPICO Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Longhurst G, Stone D, Dulohery K, et al. Strength, Weakness, Opportunity, Threat (SWOT) analysis of the adaptations to anatomical education in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Anatomical Sci Educ 2020;13:301–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tashiro A, Shaw R. COVID-19 pandemic response in Japan: What is behind the initial flattening of the curve? Sustainability (Basel) 2020;12:5250. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satici B, Saricali M, Satici S, Griffiths MD. Intolerance of uncertainty and mental well-being: serial mediation by rumination and fear of COVID-19. Int J Mental Health Addict 2020:1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundarasen S, Chinna K, Kamaludin K, et al. Psychological impact of covid-19 and lockdown among university students in malaysia: Implications and policy recommendations. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamaludin K, Chinna K, Sundarasen S, et al. Coping with COVID-19 and movement control order (MCO): experiences of university students in Malaysia. Heliyon 2020;e05339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:e17-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Djalante R, Lassa J, Setiamarga D, et al. Review and analysis of current responses to COVID-19 in Indonesia: Period of January to March 2020. Progress Disaster Sci 2020;100091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reimers FM, Schleicher A. A framework to guide an education response to the COVID-19 Pandemic of 2020. OECD; 2020. Accessed April, 14, 2020. Available from: https://teachertaskforce.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/A%20framework%20to%20guide%20an%20education%20response%20to%20the%20COVID-19%20Pandemic%20of%202020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hossain SFA, Nurunnabi M, Hussain K, et al. Effects of variety- seeking intention by mobile phone usage on university students’ academic performance. Cogent Educ 2019;6:1574692. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moorley C, Cathala X. How to appraise mixed methods research. Evidence-Based Nurs 2019;22:38–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frey B. The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (Vols. 1-4). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualit Res J 2009;9:27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shorten A, Smith J. Mixed methods research: expanding the evidence base. Evidence-Based Nurs 2017;20:74–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Regional well-being index. 2020. Accessed: June 11, 2020. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/regional/ [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bracht C. The 2015 G20 Antalya Summit Commitments. Toronto: University of Toronto: 2015. Accessed May 23, 2020. Available from: http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/analysis/commitments-15-antalya.html [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warren B. The 2016 G20 Hangzhou Summit Commitments. Toronto: University of Toronto; 2016. Accessed: May 23, 2020. Available from: http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/analysis/commitments-16-hangzhou.html [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warren B. The 2017 G20 Hamburg Summit Commitments. Toronto: University of Toronto; 2017. Accessed May 23, 2020. Available from: http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/analysis/commitments-17-hamburg.html [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warren B. The 2019 G20 Buenos Aires Summit Commitments. Toronto: University of Toronto; 2018. Accessed May 23, 2020. Available from: http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/analysis/commitments-18-buenosaires.html [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warren B. The 2019 G20 Osaka Summit Commitments. Toronto: University of Toronto; Accessed: May 23, 2020. Available from: http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/analysis/commitments-19-osaka.html [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lucas B. G7 and G20 commitments on health. K4D Helpdesk Report 673. September 27, 2019. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies; 2019. Available from: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/14734/673_G7-G20_Commitments_on_Health.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nurunnabi M, Hossain SFAH, Chinna K, et al. Coping strategies of students for anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: a cross-sectional study. F1000Res 2020;9:1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cicci A, Han JY, Popova I, et al. 2018 G20 Buenos Aires Summit Final Compliance Report. Toronto: University of Toronto; 2019. Accessed May 23, 2020. Available from: http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/compliance/2018buenosairesfinal/18-2018-g20-compliance-uhc.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 40.McBride B, Hawkes S, Buse K. Soft power and global health: the sustainable development goals (SDGs) era health agendas of the G7, G20 and BRICS. BMC Public Health 2019;19:815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barnett S, Emorine H. G20 Research Group et al. 2017 G20 Hamburg Summit Final Compliance Report. University of Toronto: 2018. Available from: http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/compliance/2017hamburg-final/2017-g20-compliancefinal.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 42.International Association of Universities. COVID-19: Higher Education challenges and responses. Available from: https://www.iau-aiu.net/Covid-19-Higher-Education-challenges-and-responses#Europe [Google Scholar]

- 43.SDG-Education 2030 Steering Committee. Recommendations for COVID-19 Education Response. Available from: https://sdg4education2030.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/SDG-Education%202030%20SC%20recommendations%20-%20COVID-19%20education%20response.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lipson SK, Lattie EG, Eisenberg D. Increased rates of mental health service utilization by US college students: 10-year population- level trends (2007-2017). Psychiatr Serv 2019;70:60-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.American Council on Education. Mental health, higher education and Covid-19: Strategies for leaders to support campus well-being. Available from: https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Mental-Health-Higher-Education-Covid-19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 46.Institute of International Education. COVID-19 Effects on US higher education campuses from emergency response to planning for future student mobility. 2020. Available from: https://www.iie.org/Research-and-Insights/Publications/COVID-19-Effects-on-US-Higher-Education-Campuses-Report-2 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Department of Health UK Government. Wellbeing. Why it matters to health policy. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/277566/Narrative__January_2014_.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 48.GuildHE Universities UK. Student Mental Well-being in higher education: Good Practice Guide. Available from: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Documents/2015/student-mental-wellbeingin-he.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 49.Universities UK. Stepchange. Mentally Healthy Universities. Available from: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-andanalysis/reports/Documents/2020/uuk-stepchange-mhu.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 50.Australian Government National Mental Health Commission. Our role. Available from: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/about/our-role [Google Scholar]