Abstract

Protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) is an important transmembrane protein in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). PERK signaling has a critical function in neuronal apoptosis. This work aimed to assess PERK signaling for its function in surgical brain injury (SBI) and to explore the underlying mechanisms. Totally 120 male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats were assessed in an SBI model. The effects of the PERK inhibitor GSK2606414 were examined by Western-blot, immunofluorescent staining, TUNEL staining, fluoro-jade C (FJC) staining and neurological assays in rats with SBI. In this study, p-PERK and p-eIF2α protein amounts were increased upon SBI establishment, peaking at 24 h. Meanwhile, administration of GSK2606414 reversed these effects and prevented neuronal apoptosis. The PERK pathway has a significant function in neuronal apoptosis, and its suppression after SBI promotes the alleviation of brain injury. This suggests that targeting the PERK signaling pathway may represent an efficient therapeutic option for improving prognosis in SBI patients.

Keywords: ER stress, UPR, PERK, eIF2α, apoptosis, SBI

Introduction

Surgical brain injury (SBI) is caused by neurosurgery and often occurs at the edge of the area upon which the surgery is performed [1]. It may lead to multiple postoperative complications such as cerebral edema, ischemia, intracranial hematoma, and neurological impairment and behavioral degeneration [2]. SBI is thought to be inevitable, and is often associated with postoperative neurologic deficits [3]. Studies have confirmed that brain edema occurs several hours after SBI, which may impair blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity and aggravate craniocerebral injury, including secondary inflammatory reactions [4,5]. SBI-induced nerve injury and cerebral edema may prolong hospital stay. Therefore, it is very important to reduce secondary brain injury caused by SBI, maintain neurological function and reduce perioperative morbidity related to intracranial neurosurgery [6]. All these actions have significant impacts on patients’ rehabilitation and reduce perioperative costs. However, few studies have focused on the pathophysiology of SBI or the development of specific treatments. Research into SBI pathology has made some progress, but the specific mechanisms underlying its occurrence and development are very complex and remain unclear. Studies have shown that SBI can lead to a series of pathological processes such as brain edema, BBB damage, inflammatory reactions, and apoptosis around the surgical site [5]. Recent reports revealed that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is substantially involved in the pathological process of secondary brain damage following SBI.

The ER is an important membranous organelle in mammalian cells, mostly contributing to protein folding and modification and Ca2+ storage and release. As a site of protein maturation in cells, the ER is sensitive to changes in the internal and external cellular environments. When the internal environment of the ER changes, stress response is activated to attempt to restore homeostasis; these changes in the ER are called ER stress (ERs) [7]. The unfolded protein response (UPR) is one of the cell response mechanisms involved in defense activation of adaptation. The UPR restores the ER’s capability of controlling protein folding, processing and secretion [8]. Through the expansion of the membrane, the ER reduces the rate of synthesis of new proteins, increases partner molecule synthesis and promotes the degradation of misfolded proteins to maintain its own steady state, thereby restoring the normal function of cells [9]. However, when the damage exceeds the system’s repair capacity, excessive accumulation of misfolded proteins leads to programmed cell death or apoptosis [10]. In this way, the intensity and duration of stimulation determine whether UPR promotes cell survival or induces apoptosis.

The UPR has three parallel signal branches, including protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase-eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (PERK-eIF2α), inositol requiring protein 1-x box binding protein 1 (IRE1-XBP1), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) pathways. Each branch can regulate a series of downstream transcription factors to participate in the survival or death of cells [2]. Under normal conditions, the ER’s chaperone glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78/BIP) interacts with the transmembrane proteins PERK, IRE1, and ATF6, respectively, preventing signal transduction. GRP78 can promote the folding and assembly of nascent polypeptides, prevent their misfolding and aggregation, induce proteasomal degradation of misfolded proteins, and control the initiation of each UPR pathway [11]. When unfolded and misfolded proteins in the ER increase in aggregated amounts, GRP78 dissociates from these three proteins, which activates them and increases folding capacity [12]. Increased GRP78 level has a protective effect on ischemic nerves [13].

More and more animal model evidence suggests that the UPR is involved in many different diseases. The UPR is gradually becoming an attractive new therapeutic drug target. Diseases in which UPR is involved include cancer, metabolic diseases, and cerebral ischemia [14]. Because it is one of the three main pathways of the UPR, the PERK-eIF2α pathway has seen increasingly studied. It has been reported that PERK is activated after brain injury when phosphorylated at ser51. Phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF2α) can also increase apoptosis by regulating AFT4 expression [15]. Yan et al. studied a rat subarachnoid hemorrhage model and showed that inhibiting PERK may alleviate early brain damage upon subarachnoid hemorrhage via an Akt-related anti-apoptotic signaling pathway [16]. Our previous report confirmed that inhibiting PERK signaling in intracerebral hemorrhage can reduce secondary brain injury following intracerebral hemorrhage and promote neuron survival by inhibiting apoptosis [17]. However, whether PERK signaling has a function in SBI remains undefined.

Therefore, the present work aimed to assess PERK levels and PERK-eIF2α signaling in a rat SBI model, and to explore the possible mechanism of the PERK signaling pathway in SBI.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

In Experiment 1, animal weights, feed intake, and motor function were similar in all animals. To examine PERK, p-PERK, eIF2α and p-eIF2α amounts following SBI, 36 rats (36 survivors in totally 40) were randomized to six groups using computer-based randomization, including the Sham, SBI 6 h, SBI 12 h, SBI 24 h, SBI 48 h and SBI 72 h groups. Brain tissues surrounding the damaged area were sampled for Western blot (WB) and double immunofluorescence analysis.

In Experiment 2, in order to assess the function of PERK signaling in SBI, 72 rats (72 survivors in totally 80 animals) were randomized to four groups using computer-based randomization, including the Sham, SBI, SBI+DMSO, and SBI+GSK groups. Euthanasia was performed at 24 h post-SBI (according to Experiment 1), and the damaged brain tissues were collected. Neurological tests were carried out in all animals prior to euthanasia. Tissues inside of the injury were evaluated by WB, those obtained from the back were used to prepare paraffin sections. TUNEL and Fluoro-jade C (FJC) staining were performed for detecting neuronal apoptosis and necrosis. All assays were strictly blinded, with specimens coded by an independent investigator.

Animals

Here, totally 120 male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (300-350 g) were obtained from JOINN Laboratories, Suzhou, China. Of these, 108 were analyzed. Animal housing was carried out under a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle at 25°C and controlled relative humidity, with rodent chow and water ad libitum.

The SBI model

SBI modelling was based on a previous report [1]. The rats underwent fixation in a stereotactic instrument upon intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (pentobarbital sodium for intraperitoneal injection at 40 mg/kg). Midline scalp incision was performed, followed by drilling of a cranial window (5 mm×5 mm) in the right frontal lobe. The entire right frontal lobe was excised (2 mm lateral and 1 mm anterior to bregma). Pressure was applied to the surrounding brain tissue to stop bleeding, followed by scalp suturing. The Sham group only underwent craniotomy and bone flap replacement without dural incision. Postoperatively, the rats were euthanized at various times.

Drug injection

According to a previous study, GSK2606414 (MCE, USA) was dissolved at 90 μg/5 μl in 20% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), while animals treated with the vehicle received 20% DMSO. All treatments were administered intracerebroventricularly at 0.5 μl/min 1 h after operation [17].

Immunoblot

WB was carried out according to a previous report [18]. Briefly, cortex tissue specimens were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer containing protease Inhibitors (CWBIO, China), and centrifuged at 13,000×g and 4°C for 15 min. Protein amounts in the supernatants were assessed with PierceTM BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher, USA). Equal amounts of protein underwent separation by 10% SDS-PAGE (Beyotime, China) followed by transfer onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, USA). Upon blocking (5% skimmed milk for 2 h at ambient), the membranes were submitted to overnight incubation at 4°C with rabbit primary antibodies targeting PERK (1:1000, Abcam, UK), p-PERK (1:500, Cell Signaling, USA), eIF2α (1:500, Abcam), p-eIF2α (1:500, Abcam), ATF4 (1:1000, Abcam) and GAPDH (1:10000, Sigma, USA). The membranes were then incubated with HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, USA) secondary antibodies for 2 h at 4°C. Detection used chemiluminescent substrate (Millipore) and a LUMINESCENT IMAGE ANALYZER (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Sweden). ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, USA) was used to analyze immunoreactive bands.

Immunofluorescence

Double immunofluorescence (IF) was carried out according to a previous report [19]. Briefly, brain tissue specimens underwent fixation with 4% formalin, paraffin embedding and longitudinal sectioning at 5 μm. After dewaxing and washing, the sections were blocked with Immunostaining sealant (Beyotime) for 1 h at ambient, followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with rabbit primary antibodies targeting p-PERK (1:100, Abcam) and p-eIF2α (1:200, Abcam), and mouse anti-NeuN primary antibodies (1:1000, Abcam), respectively. Next, the specimens were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:400, Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 555-linked donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:400, Invitrogen) for 1 h at ambient. Finally, counterstaining was carried out with DAPI for 10 min, and a U-RFL-T fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS, Japan) was utilized for analysis.

TUNEL staining

TUNEL staining was carried out for apoptosis detection [17]. The sections were dewaxed before TUNEL staining, and successively incubated with proteinase K (37°C for 20 min) and TUNEL detection liquid (Beyotime). TUNEL-positive neurons were assessed under a U-RFL-T fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS, Japan).

Fluoro-Jade C staining

Fluoro-Jade C (FJC) staining was performed for detecting neuronal necrosis in accordance with the standard procedure described in the kit (Biosensis, South Australia). Briefly, the sections were dewaxed and incubated with potassium permanganate (1:10 in distilled water) for 10 min. After rinsing with distilled water (2 min), the samples were incubated with FJC (1:10 in distilled water) in the dark for 10 min. Following 3 rinses with distilled water, the sections were dried at 60°C for 5 min, soaked in xylene for 1 min and coverslipped with distyrene plasticizer xylene (DPX). FJC-positive cells were photographed under a U-RFL-T fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS, Japan) and averaged in three high-power fields.

Brain edema assessment

The wet-dry technique was carried out for assessing brain edema in the injured brain [20]. Briefly, brain specimens were separated into ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. After obtaining wet weights, the specimens underwent drying at 100°C for 48 h, followed by dry weight measurements. The rate of brain water content (%) was derived as [(wet weight-dry weight)/(wet weight)] ×100%.

Neurological scoring

Neurological deficiency was assessed at 24 h post-SBI based on the modified Garcia score [21,22]. Scores in each subtest ranged between 0 and 3 (maximum total score of 21, indicating no neurological defects).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out with GraphPad Prism 8.0 (San Diego, USA). Data are mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare immunoblot data, with post hoc Dunnett’s test. Student’s t-test was performed for analyzing immunofluorescent staining data. One-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test was performed for analyzing TUNEL and FJC staining, as well as neurological behavioral scores and brain water content. P<0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Post-SBI brain expression of PERK pathway proteins

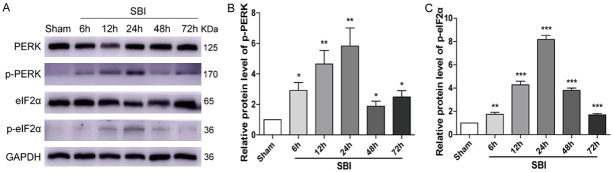

PERK, p-PERK, eIF2α, and p-eIF2α protein amounts at 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h after SBI were assessed by Western blotting (Figure 1). The results showed that p-PERK and p-eIF2α amounts started to increase at 6 h upon SBI and peaked at 24 h. Meanwhile, total protein levels of PERK and eIF2α were unaltered.

Figure 1.

Post-SBI PERK/p-PERK and eIF2α/p-eIF2α protein amounts in the peri-injury cortex. Immunoblot was carried out for determining PERK/p-PERK and eIF2α/p-eIF2α amounts in the Sham and SBI groups at 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h following SBI. The Sham group was used for normalization, and quantitation used ImageJ. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Dunnett’s test was carried out for group comparisons (n=6 for each group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. Sham; ns P>0.05 vs. Sham).

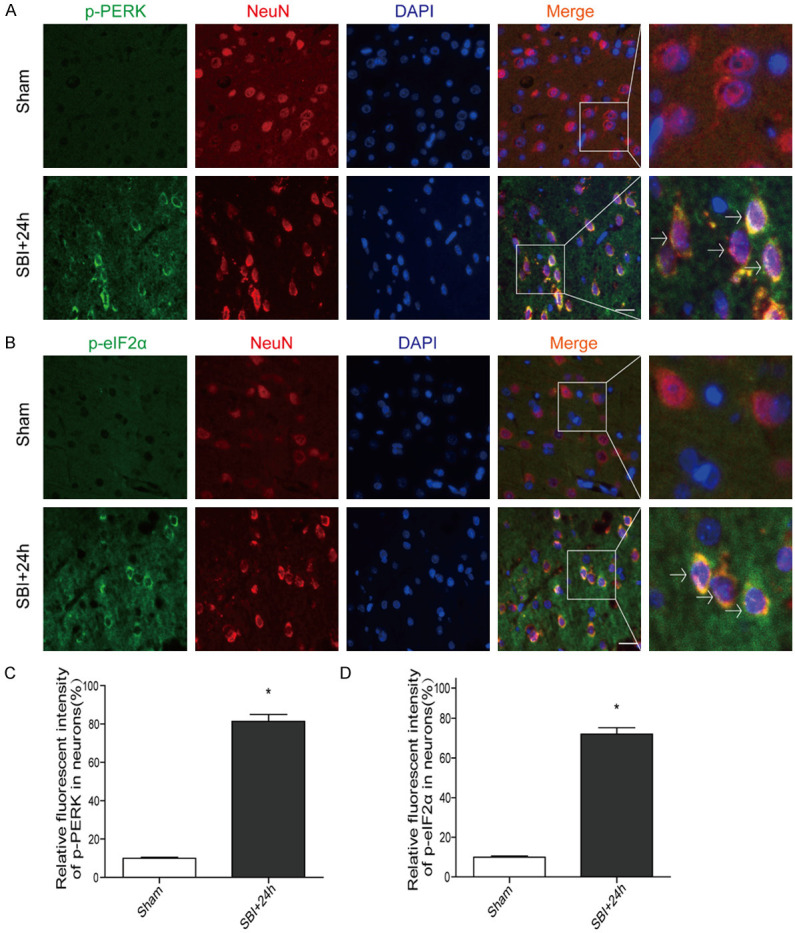

Post-SBI localization of p-PERK and p-eIF2α in cortical cells surrounding the injury

p-PERK and p-eIF2α localizations were evaluated by IF staining with NeuN (a neuronal marker) (Figure 2). Consistent with WB analysis, IF findings revealed that there were numerous p-PERK-positive neurons (Figure 2A, 2C) in the 24 h post-SBI group compared with the Sham group. There were also more p-eIF2α-positive neurons (Figure 2B, 2D) in the 24 h post-SBI group compared with the Sham group.

Figure 2.

Post-SBI IF micrographs depicting p-PERK and p-eIF2α in the peri-injury cortex. Representative double-immunofluorescence micrographs showing green-labeled p-PERK (A, C)/p-eIF2α (B, D) and red-labeled NeuN neurons in the Sham and 24 h post-SBI groups. Counterstaining utilized DAPI (blue). Arrows point to p-PERK/p-eIF2α co-localization with neurons. Scale bar, 50 µm. Student’s t test was performed for analyses (n=6, *P<0.05 vs. Sham).

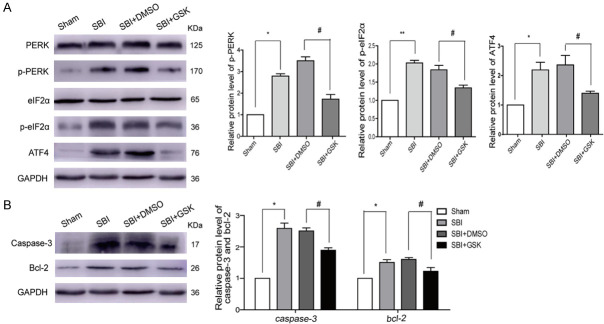

GSK2606414 intervention and the PERK pathway after SBI

After GSK2606414 intervention following SBI, p-PERK and p-eIF2α protein amounts were markedly reduced in comparison with the SBI group. The SBI+DMSO group was similar to the SBI group in protein amounts. Additionally, ATF-4 amounts were significantly elevated in the SBI and SBI+DMSO groups compared with the Sham group. After GSK2606414 intervention, ATF-4 levels were remarkably decreased compared with the SBI group (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Effect of GSK2606414 intervention on PERK signaling pathway 24 h post-SBI. PERK pathway protein amounts were assessed after GSK2606414 intervention in SBI rats (A). Caspase-3 and Bcl-2 protein amounts after GSK2606414 intervention in SBI rats (B). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Tukey’s test was carried out for comparisons (n=6 for each group; *P<0.05 vs. Sham; #P<0.05 vs. SBI+DMSO).

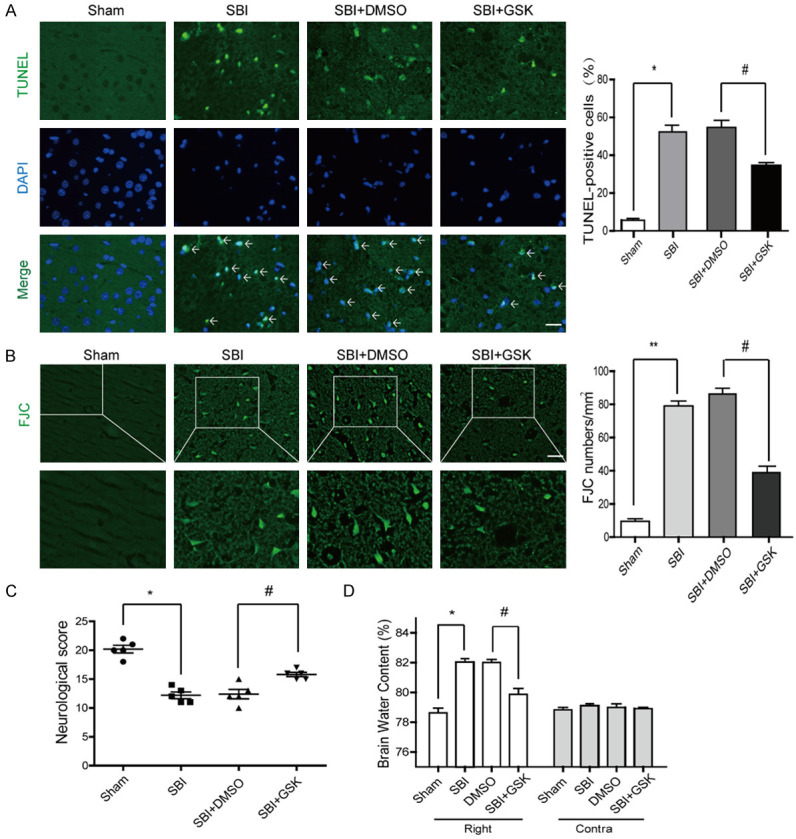

GSK2606414 intervention and post-SBI neuronal apoptosis and necrosis

Caspase-3 and Bcl-2 protein levels were lower after GSK2606414 intervention post-SBI compared with those of the SBI group (Figure 3B). Neuron necrosis in the SBI group was remarkably elevated in comparison with that of the Sham group (Figure 4A, 4B). Necrosis levels were similar in the SBI and SBI+DMSO groups. Meanwhile, necrosis level was starkly reduced in the SBI+GSK group compared with the SBI group.

Figure 4.

Effect of GSK2606414 intervention on PERK signaling pathway 24 hours after SBI. TUNEL (A) and FJC (B) staining in SBI rats after GSK2606414 intervention. Neurological behavioral scores in SBI rats following GSK2606414 administration (C). Brain water amounts of the bilateral hemispheres were assessed by the wet-dry technique (D). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Tukey’s test was carried out for comparisons (n=6, *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. Sham; #P<0.05 vs. SBI+DMSO).

GSK2606414 intervention improves neurological behavioral scores in SBI rats

Neurological behavioral scores were starkly decreased in the SBI group in comparison with the Sham group, while the SBI and SBI+DMSO groups had comparable values. The SBI+GSK group had overtly ameliorated neurological behavioral scores in comparison with the SBI group (Figure 4C). In addition, brain edema was markedly reduced in the injured hemispheres following GSK2606414 intervention post-SBI. However, brain edema had no significant alteration in the contralateral brain (Figure 4D).

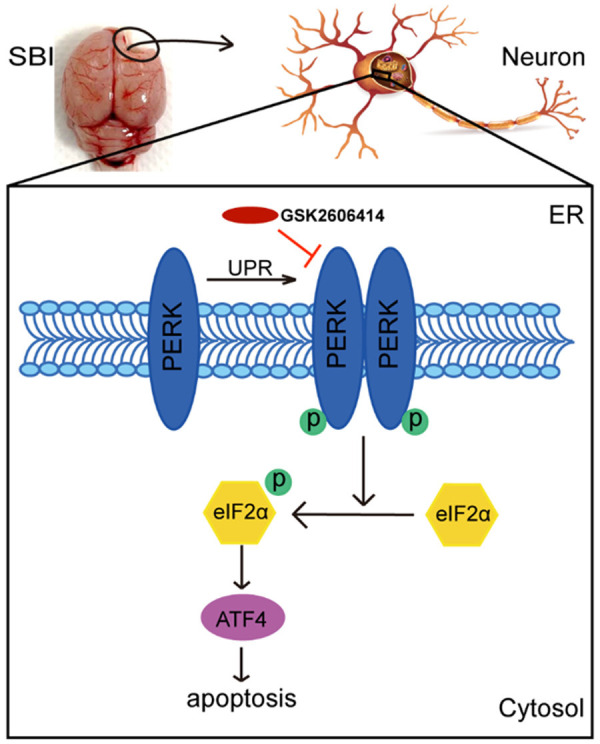

Taken together, ER stress was activated in rats after SBI, and the PERK signaling pathway was activated after SBI with increased p-PERK and p-eIF2α amounts. This increased ATF4 protein levels and led to neuronal apoptosis (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Probable mechanisms underpinning PERK signaling pathway’s effects on SBI. After SBI, PERK signaling was activated and p-PERK and p-eIF2α amounts were increased. In addition, the protein levels of ATF4 were increased and led to neuronal apoptosis. GSK2606414 intervention reversed these effects, reducing neuronal apoptosis and necrosis, which played a protective role in brain injury after SBI.

Discussion

After primary injury, SBI causes postoperative nerve injury and brain edema, aggravating craniocerebral injury. Identifying a tool to reduce nerve injury after SBI is an important factor in prognosis. We here described the neuroprotective effects of the PERK signaling pathway on preserving neurons and attenuating brain edema after SBI. First, we measured p-PERK and p-eIF2α protein amounts in the peri-surgical brain tissue after SBI. The results showed that p-PERK and p-eIF2α amounts were markedly elevated and peaked at 24 h after SBI. Next, we determined whether suppressing PERK signaling would be beneficial in SBI, especially in reducing apoptosis and brain edema surrounding the surgical injury. As shown above, the PERK signaling pathway inhibitor GSK2606414 markedly ameliorated neurological function and reduced brain edema in SBI rats. The present study firstly described the possible neuroprotective effects of the PERK signaling pathway in a rat model of SBI.

The ER lumen constitutes an oxidative environment, and is essential for disulfide bond formation and the proper folding of proteins. ER stress is due to the destruction of ER function [23]. Several studies have shown that oxidative stress [24], ionic cell alteration [25], high mitochondrial calcium amounts [26], and toxic glutamate release [27] can induce ER stress in various diseases. Dual effects of ERs on cells have been demonstrated. Mild ERs can activate autophagy, facilitate the digestion of unfolded proteins and damaged organelles, and improve cell survival. However, apoptosis occurs when ERs is too severe to digest unfolded proteins and compensate for cell damage [28]. Cerebral ischemic preconditioning can protect the brain from ischemia and reperfusion injury via the inhibition of ERs-associated apoptosis [29]. Under ERs, the IRE1 pathway, one of the three parallel signaling branches, mediates both adaptive and pro-apoptotic pathways in CNS diseases [30], inhibits the activation of Caspase-3 and reduces free calcium accumulation in the cytosol [31]. The inhibition of ERs can increase nerve cell survival and improve nerve function [32].

PERK signaling, one of the three classical UPR branches, has a critical function in neuronal death. When the central nervous system is damaged, its constituent proteins PERK and eIF2α are phosphorylated and upregulated in neurons. In cerebral ischemia, the PERK-eIF2α signaling pathway is activated [33]. Inhibition of the PERK and IRE1 signaling pathways can suppress ERs-dependent autophagy and alleviate acute nerve injury caused by ischemic stroke [22]. The levels of PERK and eIF2α are increased in traumatic brain injury [34]. PERK-eIF2α pathway induction after UPR is considered to mediate ER-stress-induced autophagy, causing prolonged inhibition of global protein biosynthesis, promoting neuronal loss and clinical disease [35,36]. Inhibiting the PERK signaling pathway can improve motor function and promote neurological function recovery by attenuating neuronal damage [37]. The PERK signaling pathway is induced by high amounts of unfolded proteins in the ER and leads to neuronal death [38]. Inhibiting PERK signaling reduces early brain injury upon subarachnoid hemorrhage [39]. Consistent with the above observations, our previous studies demonstrated in cell and animal models of cerebral hemorrhage that p-elF2α and ATF4 amounts in neurons are remarkably increased, reaching the highest levels at 48 h [17]. In accordance with our previous findings, p-PERK and p-eIF2α amounts peaked at 24 h after SBI, and GSK2606414 inhibited cell apoptosis and promoted neuronal survival by suppressing p-PERK, p-eIF2α and ATF4 after SBI. PERK inhibition decreased Caspase-3 and Bcl-2 levels, thereby decreasing the rate of nerve apoptosis. The degree of cerebral edema was also reduced by GSK2606414. Therefore, inhibiting PERK signaling showed a neuroprotective effect after SBI.

This study had several limitations. Other studies have shown that ERs has dual effects on the cell fate, with mild ERs activating autophagy to provide nutritional support for cells [28]. In addition, the present work only investigated the effect of severe ER stress on nerve apoptosis after SBI. The mechanism by which the UPR pathway protects cells and promotes apoptosis between survival and death is unclear. Furthermore, the GRP78 protein is thought to bind to the three transmembrane protein receptors PERK, IRE1, and ATF6 under physiological conditions. Moreover, under severe ERs conditions, the GRP78 protein is separated from PERK, ATF6, and IRE1 when misfolded proteins accumulate to a certain extent in the ER lumen [40]. Here, only PERK pathway’s effects were evaluated, and the two other transmembrane protein receptors IRE1 and ATF6 require further investigation. Finally, PERK signaling initiation following SBI deserves further assessment. These issues are being addressed in ongoing experiments in our group.

Overall, these findings indicate that under severe ERs, PERK signaling pathway inhibition can suppress apoptosis and ultimately reduce secondary brain injury after SBI. Therefore, PERK signaling may represent an important endogenous physiological regulatory signaling pathway in neurons, and could be targeted for the alleviation of brain damage after SBI.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to LetPub (www.letpub.com) for help in language editing of the present manuscript. This work was funded by the Suzhou people’s livelihood science and technology project (SYS2019002), Gusu health personnel training project (GSWS2019076), Zhangjiagang science and technology project (ZKS1712, ZKS1942), and Zhangjiagang youth science and technology project (ZJGQNKJ201913).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Huang L, Woo W, Sherchan P, Khatibi NH, Krafft P, Rolland W, Applegate RL, Martin RD, Zhang J. Valproic acid pretreatment reduces brain edema in a rat model of surgical brain injury. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2016;121:305–310. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18497-5_53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang L, Sherchan P, Wang Y, Reis C, Applegate RL, Tang J, Zhang JH. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma contributes to neuroinflammation in a rat model of surgical brain injury. J Neurosci. 2015;35:10390–10401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0546-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fugate JE. Complications of neurosurgery. Continuum. 2015;21:1425–1444. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vikram J, Gerald M, Hsu FP, Zhang JH. Inhibition of Src tyrosine kinase and effect on outcomes in a new in vivo model of surgically induced brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:680–686. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.4.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matchett G, Hahn J, Obenaus A, Zhang J. Surgically induced brain injury in rats: the effect of erythropoietin. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;158:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benggon M, Chen H, Applegate RL, Zhang J. Thrombin preconditioning in surgical brain injury in rats. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2016;121:299–304. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18497-5_52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torres M, Matamala JM, Duran-Aniotz C, Cornejo VH, Foley A, Hetz C. ER stress signaling and neurodegeneration: at the intersection between Alzheimer’s disease and Prion-related disorders. Virus Res. 2015;207:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bocai NI, Marcora MS, Belfiori-Carrasco LF, Morelli L, Castano EM. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in tauopathies: contrasting human brain pathology with cellular and animal models. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;68:439–458. doi: 10.3233/JAD-181021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uddin MS, Tewari D, Sharma G, Kabir MT, Barreto GE, Bin-Jumah MN, Perveen A, Abdel-Daim MM, Ashraf GM. Molecular mechanisms of ER stress and UPR in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2020;57:2902–2919. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-01929-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park KW, Eun Kim G, Morales R, Moda F, Moreno-Gonzalez I, Concha-Marambio L, Lee AS, Hetz C, Soto C. The endoplasmic reticulum chaperone GRP78/BiP modulates prion propagation in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44723. doi: 10.1038/srep44723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Hendershot LM, Harding HP, Ron D. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:326–332. doi: 10.1038/35014014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouyang YB, Lu Y, Yue S, Xu LJ, Xiong XX, White RE, Sun X, Giffard RG. miR-181 regulates GRP78 and influences outcome from cerebral ischemia in vitro and in vivo. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cnop M, Foufelle F, Velloso LA. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, obesity and diabetes. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Majsterek I, Diehl JA, Leszczynska H, Mucha B, Pytel D, Rozpedek W. The role of the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP signaling pathway in tumor progression during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Curr Mol Med. 2016;16:533–544. doi: 10.2174/1566524016666160523143937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan F, Cao S, Li J, Dixon B, Yu X, Chen J, Gu C, Lin W, Chen G. Pharmacological inhibition of PERK attenuates early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats through the activation of akt. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:1808–1817. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9790-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng C, Zhang J, Dang B, Li H, Shen H, Li X, Wang Z. PERK pathway activation promotes intracerebral hemorrhage induced secondary brain injury by inducing neuronal apoptosis both in vivo and in vitro. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:111. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.You W, Wang Z, Li H, Shen H, Xu X, Jia G, Chen G. Inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin attenuates early brain injury through modulating microglial polarization after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. J Neurol Sci. 2016;367:224–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z, Wang Y, Tian X, Shen H, Dou Y, Li H, Chen G. Transient receptor potential channel 1/4 reduces subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced early brain injury in rats via calcineurin-mediated NMDAR and NFAT dephosphorylation. Sci Rep. 2016;367:224–31. doi: 10.1038/srep33577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg GA, Estrada EY, Dencoff JE. Matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs are associated with blood-brain barrier opening after reperfusion in rat brain. Stroke. 1998;29:2189–2195. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.10.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu M, Gao F, Yang X, Qin X, Chen G, Li D, Dang B, Chen G. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 regulates the blood brain barrier via the hedgehog pathway in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2020;1727:146553. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.146553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng D, Wang B, Wang L, Abraham N, Tao K, Huang L, Shi W, Dong Y, Qu Y. Pre-ischemia melatonin treatment alleviated acute neuronal injury after ischemic stroke by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent autophagy via PERK and IRE1 signalings. J Pineal Res. 2017;62 doi: 10.1111/jpi.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roussel BD, Kruppa AJ, Miranda E, Crowther DC, Lomas DA, Marciniak SJ. Endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction in neurological disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:105–118. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goswami P, Gupta S, Biswas J, Sharma S, Singh S. Endoplasmic reticulum stress instigates the rotenone induced oxidative apoptotic neuronal death: a study in rat brain. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:5384–5400. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9463-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varadarajan S, Tanaka K, Smalley JL, Bampton ET, Pellecchia M, Dinsdale D, Willars GB, Cohen GM. Endoplasmic reticulum membrane reorganization is regulated by ionic homeostasis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Y, Peng S, Ting W, Kaixian C, Weiliang Z, Heyao W, Tohru M. Inhibition of calcium influx reduces dysfunction and apoptosis in lipotoxic pancreatic β-cells via regulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Li J, Li S, Li Y, Wang X, Liu B, Fu Q, Ma S. Curcumin attenuates glutamate neurotoxicity in the hippocampus by suppression of ER stress-associated TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome activation in a manner dependent on AMPK. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;286:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shao Z, Pei W, Xuefeng W, Meishan J, Shuang L, Xudong M, Huaizhang S. Tetramethylpyrazine protects against early brain injury and inhibits the PERK/Akt pathway in a rat model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurochem Res. 2018;43:1650–1659. doi: 10.1007/s11064-018-2581-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu YQ, Chen W, Yan MH, Lai JJ, Wu L. Ischemic preconditioning protects brain from ischemia/reperfusion injury by attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis through PERK pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:5736–5744. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201712_14020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni H, Rui Q, Li D, Gao R, Chen G. The role of IRE1 signaling in the central nervous system diseases. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16:1340–1347. doi: 10.2174/1570159X16666180416094646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ni H, Rui Q, Xu Y, Zhu J, Gao F, Dang B, Li D, Gao R, Chen G. RACK1 upregulation induces neuroprotection by activating the IRE1-XBP1 signaling pathway following traumatic brain injury in rats. Exp Neurol. 2018;304:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsujii S, Ishisaka M, Shimazawa M, Hashizume T, Hara H. Zonisamide suppresses endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell damage in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;746:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gharibani P, Modi J, Menzie J, Alexandrescu A, Wu JY. Comparison between single and combined post-treatment with S-Methyl-N, N-diethylthiocarbamate sulfoxide (DETC-MeSO) and taurine following transient focal cerebral ischemia in rat brain. Neuroscience. 2015;300:460–473. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubovitch V, Barak S, Rachmany L, Goldstein RB, Zilberstein Y, Pick CG. The neuroprotective effect of salubrinal in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury. Neuromolecular Med. 2015;17:58–70. doi: 10.1007/s12017-015-8340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radford H, Moreno JA, Verity N, Halliday M, Mallucci GR. PERK inhibition prevents tau-mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130:633–642. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1487-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kouroku Y, Fujita E, Tanida I, Ueno T, Isoai A, Kumagai H, Ogawa S, Kaufman RJ, Kominami E, Momoi T. ER stress (PERK/eIF2a phosphorylation) mediates the polyglutamine-induced LC3 conversion, an essential step for autophagy formation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:230–239. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun D, Wang J, Liu X, Fan Y, Yang M, Zhang J. Dexmedetomidine attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and improves neuronal function after traumatic brain injury in mice. Brain Res. 2020;1732:146682. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.146682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, Li J, Li S, Li Y, Wang X, Liu B, Fu Q, Ma S. Curcumin attenuates glutamate neurotoxicity in the hippocampus by suppression of ER stress-associated TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome activation in a manner dependent on AMPK. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;286:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan F, Cao S, Li J, Dixon B, Yu X, Chen J, Gu C, Lin W, Chen G. Pharmacological inhibition of PERK attenuates early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats through the activation of akt. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:1808–1817. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9790-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakka VP, Prakash-babu P, Vemuganti R. Crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress, oxidative stress, and autophagy: potential therapeutic targets for acute CNS injuries. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;53:532–544. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-9029-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]