Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is characterized by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) needing mechanical ventilation and intensive care unit (ICU) treatment. In addition to lung disease, clinical features of SARS-CoV-2 include myocardial damage and ischemia-related vascular disease, which are associated with a hypercoagulable state (e.g., high D-dimer levels) predisposing to thrombotic-related complications and eventually death. 1 2 3 Serum albumin levels <3.5 g/dL are detectable in SARS-CoV-2 patients and associated with death 4 and elevated D-dimer and thrombotic events, 5 which is in accordance with previous studies reporting an association between serum albumin <3.5 g/dL and risk of venous and arterial thrombosis. 6 Thus, we tested the hypothesis that albumin supplementation could dampen hypercoagulability in SARS-CoV-2 with serum albumin <3.5 g/dL.

This is an observational cohort study performed at a large university hospital located in Rome and Chieti (Italy) and devoted to COVID-19 care.

We included in the study adult (≥18 years) patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2-related pneumonia, requiring or not mechanical ventilation, consecutively hospitalized from May to September 2020. COVID-19 was diagnosed on the basis of the World Health Organization interim guidance. 7 A COVID-19 case was defined as a person with laboratory confirmation of COVID-19 infection, irrespective of clinical signs and symptoms. Oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal swabs for laboratory diagnosis of COVID-19 were performed in duplicate: SARS-CoV-2 E and S genes were detected by a reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

The study included patients having high D-dimer, i.e., plasma values >1 µg/mL, and treated with prophylactic doses of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH; n = 10) plus albumin supplementation ( n = 10); albumin supplementation was given intravenously at dosage of 80 g/day in the first 3 days and 40 g/day thereafter for a maximum of 7 days. Patients with high D-dimer treated with prophylactic doses of LMWH alone were used as controls ( n = 19). Demographic and clinical characteristics were collected after receiving informed consent. Routine analysis included coagulation tests (D-dimer, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen), serum albumin, and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP).

In both groups, D-dimer and serum albumin were measured at baseline and after 7 days of follow-up. During the intrahospital follow-up, thrombotic events and survival were registered as previously described. 5 Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Ethics Committee of Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Policlinico Umberto I with the agreement of Chieti University.

Statistical analyses were undertaken using SPSS 18.0 software for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, United States). Between-group differences were analyzed by Kruskal–Wallis tests. The Wilcoxon test was used to assess the difference of the covariates before and after 7 days. Bivariate analysis was performed by the Spearman test. Differences between percentages were assessed by the χ 2 -test. A p -value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Characteristics of patients included in the study are reported in Table 1 . No significant difference was observed at baseline between albumin-treated patients and controls for age, gender, albumin, D-dimer, creatinine, hs-CRP levels, and clinical characteristics ( Table 1 ). Furthermore, there were no differences in the percentage of patients admitted to the ICU and medical wards ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of study in SARS-CoV-2 patients treated with albumin and controls.

| Albumin group | Control group | p -Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 10 | 19 | – | |||

| Age (y) | 82 ± 9 | 74 ± 13 | 0.085 a | |||

| Female/male | 8/2 | 7/12 | 0.052 b | |||

| Obesity | 0 | 7 | 0.06 b | |||

| Hypertension | 2 | 8 | 0.419 b | |||

| Diabetes | 1 | 4 | 0.632 b | |||

| Smoking habit | 1 | 2 | 1 b | |||

| COPD | 0 | 1 | 1 b | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | 0 | 1 | 1 b | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 0 | 3 | 0.532 b | |||

| ICU hospitalization | 5 | 14 | 0.243 b | |||

| Medical ward hospitalization | 5 | 5 | 0.244 b | |||

| Length of hospital stay | 31 ± 10 | 20 ± 11 | 0.010 b | |||

| Cardiovascular events | 1 hemorrhagic event | 2 ischemia, 1 pulmonary embolism, 1 stroke | 0.632 b | |||

| Death | 0/10 (0%) | 8/19 (42%) | 0.02 b | |||

| Pharmacological therapy | ||||||

| Tocilizumab | 5 | 13 | 0.229 b | |||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 4 | 15 | 0.316 b | |||

| Piperacillin and tazobactam | 6 | 16 | 0.582 b | |||

| Teicoplanin | 5 | 15 | 0.479 b | |||

| Lopinavir/Ritonavir | 2 | 10 | 0.253 b | |||

| Darunavir | 1 | 2 | 0.968 b | |||

| Baseline | After 7 days of albumin treatment | p-Value | Baseline | After 7 days | p-Value | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.7 [2.6–3.1] | 3.6 [2.9–4.1] | 0.014 c | 3.0 [2.6–3.3] | 2.9 [2.6–3.3] | 0.347 c |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.96 [0.47–1.7] | 0.77 [0.44–1.51] | 0.240 c | 1.4 [0.8–1.7] | 1.6 [0.65–2.1] | 0.983 c |

| hs-CRP (µg/L) | 61,295 [40,627–10,1525] | 35,460 [18,725–80,505] | 0.285 c | 100,000 [28,860–203,000] | 61,545 [6,325–126,325] | 0.421 c |

| D-Dimer (µg/mL) | 3.23 [1.4–4.4] | 1.3 [0.6–2.1] | 0.005 c | 3.37 [1.8–4.7] | 4.4 [1.1–4.4] | 0.754 c |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; ICU, intensive care unit.

Note: Statistically significant values are highlighted in bold.

Comparison between patients treated with albumin and controls (by Kruskal–Wallis tests).

Comparison between patients treated with albumin and controls (by χ 2 -test).

Comparison between values at baseline vs. after 7 days (by Wilcoxon test).

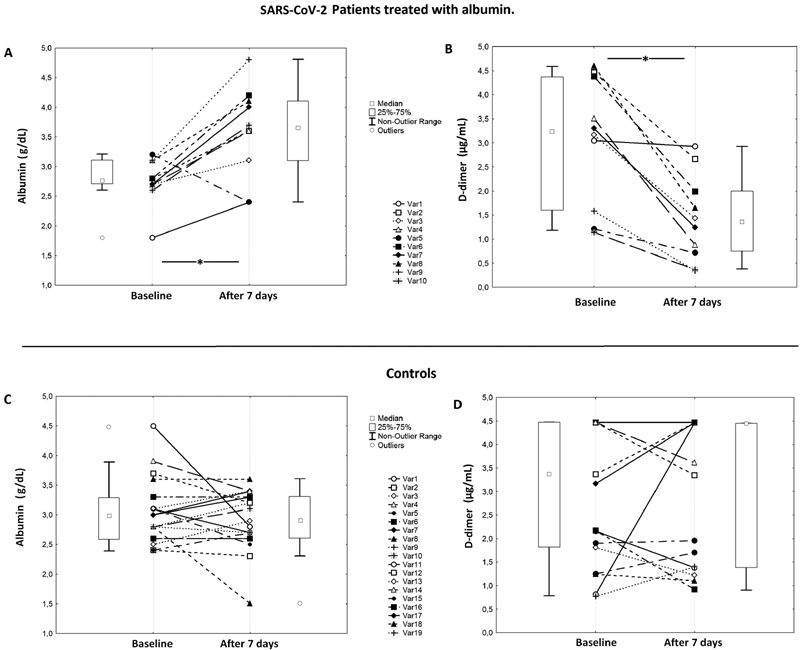

At baseline, both groups had low values of serum albumin, approximately around 3.0 g/dL, and high values of D-dimer, approximately 3 µg/mL. The pairwise comparisons showed that only after albumin treatment D-dimer levels significantly decreased ( Table 1 and Fig. 1 ); at the end of treatment, D-dimer was reduced by >50% in albumin-treated patients while no changes were detected in untreated ones. Conversely, serum albumin significantly increased in albumin-treated patients reaching, in average, values >3.5 g/dL. Bivariate analysis, performed by the Spearman test, showed that the absolute delta of albumin was inversely correlated with absolute delta of D-dimer ( R s : −0.440, p = 0.006). During the hospital stay, a bleeding complication was registered in albumin-treated patients. A nonsignificant trend was observed for the occurrence of cardiovascular events between patients treated with albumin versus controls; a significant difference was observed for the number of deaths ( Table 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Serum albumin and D-dimer levels in SARS-CoV-2 patients treated with albumin ( A and B ) and controls ( C and D ).

The study provides the first evidence that albumin supplementation dampens hypercoagulability in patients with SARS-CoV-2.

D-Dimer is a split-off product of fibrin degradation by plasmin and is, therefore, considered a marker of hypercoagulability. 8 Elevated levels of D-dimer are a frequent feature of SARS-CoV-2 and associated with an increased risk of thrombosis and death. 2 3 Hence anticoagulant treatment became a standard therapy for SARS-CoV-2 patients to reduce the thrombotic risk. Even if observational studies demonstrated that prophylactic as well as full dosage of anticoagulants improved survival in a population affected by SARS-CoV-2, the mortality was still elevated suggesting the need for identifying novel therapeutic strategies. 9

Albumin is an acute-phase reactant, which is usually reduced in the case of acute and chronic inflammation, thus under normal physiologic conditions albumin exerts an antioxidant effect via an abundant source of free thiols that are able to scavenge reactive oxidant species (ROS). 10 In the case of oxidative stress, the Cys34 of albumin may undergo irreversible oxidation, which impairs its antioxidant property and eventually elicits cell and tissue damage. 10 It is interesting, in this regard, that albumin oxidation triggers neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) via ROS accumulation within neutrophils, which eventually accumulate within lungs; 10 of note, accumulation of leucocytes and NETs has been detected in the thrombi detected in the lungs of SARS-CoV-2 patients. 11 12 13 Previous studies reported that albumin possesses antiplatelet and anticoagulant properties via a mechanism possibly related to its antioxidant effect. 14 In particular, albumin inhibits fibrin polymerization, enhances the effect of antithrombin III, and modulates the hepatic synthesis of factor V, factor VIII, and fibrinogen; 15 16 furthermore, albumin impairs platelet aggregation with a mechanism related to downregulation of Nox2, a powerful producer of ROS. 14 Others and we have previously reported a close inverse relationship between serum albumin and D-dimer suggesting hypoalbuminemia as a factor favoring hypercoagulability, thrombosis, and death. 4 17

This hypothesis has been tested in the present study including patients with elevated D-dimer and serum albumin, in average <3.5 g/dL. We found a significant increase of serum albumin in albumin-treated patients coincidentally with a marked reduction of D-dimer, while no changes of D-dimer and serum albumin were detected in the control group. This finding suggests that albumin exerts an anticoagulant activity in human, thereby its supplementation could turn useful in SARS-CoV-2 patients, in whom anticoagulant treatment, at least with a prophylactic dosage, seems to be unable to lower D-dimer; the coexistent low serum albumin could, perhaps, slow down clotting inhibition by anticoagulants. Unfortunately, however, our sample size does not permit drawing any inference regarding albumin supplementation and clinical outcomes; of note, however, we registered four deaths only in the control group. Even if this preliminary study is limited by a lack of randomization and inadequate sample size, it could suggest a novel therapeutic tool to counteract hypercoagulability in SARS-CoV-2 with elevated D-dimer and low serum albumin and warrants, therefore, further investigation by randomized clinical trials.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Authors' Contributions

F.V. designed the research and wrote the manuscript. P.P. wrote the manuscript. G.C., F.C., F.A., G.D'E, D.D., M.V., F.P., and C.M.M. performed the research. L.L. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and provided the final approval of the manuscript.

What is known about this topic?

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) displays low levels of serum albumin which are associated with hypercoagulability and predict venous and arterial thrombosis.

It is unclear if albumin supplementation is able to reduce hypercoagulability in SARS-CoV-2.

What does this paper add?

An observational prospective study performed in 29 SARS-CoV-2 patients treated with anticoagulant alone or anticoagulant plus albumin supplementation for 7 days demonstrated a significant decrease of D-dimer only in albumin-treated patients.

Albumin supplementation may represent a novel tool to dampen hypercoagulability in SARS-CoV-2.

References

- 1.Violi F, Pastori D, Cangemi R, Pignatelli P, Loffredo L. Hypercoagulation and antithrombotic treatment in coronavirus 2019: a new challenge. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(06):949–956. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang L, Yan X, Fan Q. D-dimer levels on admission to predict in-hospital mortality in patients with Covid-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(06):1324–1329. doi: 10.1111/jth.14859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simadibrata D M, Lubis A M. D-dimer levels on admission and all-cause mortality risk in COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e202. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820002022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Violi F, Cangemi R, Romiti G F. Is albumin predictor of mortality in COVID-19? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2020 doi: 10.1089/ars.2020.8142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Violi F, Ceccarelli G, Cangemi R. Hypoalbuminemia, coagulopathy, and vascular disease in COVID-19. Circ Res. 2020;127(03):400–401. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ronit A, Kirkegaard-Klitbo D M, Dohlmann T L. Plasma albumin and incident cardiovascular disease: results from the CGPS and an updated meta-analysis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(02):473–482. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization; Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected: interim guidance V 1.2. 13 March 2020Accessed November 13, 2020 at:https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/clinical-management-of-novel-cov.pdf

- 8.Olson J D. D-dimer: an overview of hemostasis and fibrinolysis, assays, and clinical applications. Adv Clin Chem. 2015;69:1–46. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paranjpe I, Fuster V, Lala A. Association of treatment dose anticoagulation with in-hospital survival among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(01):122–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue M, Nakashima R, Enomoto M. Plasma redox imbalance caused by albumin oxidation promotes lung-predominant NETosis and pulmonary cancer metastasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9(01):5116. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07550-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradley B T, Maioli H, Johnston R.Histopathology and ultrastructural findings of fatal COVID-19 infections in Washington state: a case series Lancet 2020396(10247):320–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ackermann M, Verleden S E, Kuehnel M. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(02):120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolhnikoff M, Duarte-Neto A N, de Almeida Monteiro R A. Pathological evidence of pulmonary thrombotic phenomena in severe COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(06):1517–1519. doi: 10.1111/jth.14844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.PRO-LIVER Collaborators . Basili S, Carnevale R, Nocella C. Serum albumin is inversely associated with portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2019;3(04):504–512. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galanakis D K. Anticoagulant albumin fragments that bind to fibrinogen/fibrin: possible implications. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1992;18(01):44–52. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1002409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikhailidis D P, Ganotakis E S. Plasma albumin and platelet function: relevance to atherogenesis and thrombosis. Platelets. 1996;7(03):125–137. doi: 10.3109/09537109609023571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salinas M, Blasco Á, Santo-Quiles A, Lopez-Garrigos M, Flores E, Leiva-Salinas C. Laboratory parameters in patients with COVID-19 on first emergency admission is different in non-survivors: albumin and lactate dehydrogenase as risk factors. J Clin Pathol. 2020 doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]