Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

This version of the manuscript contains minor changes and additional comments or insights that were stimulated by the helpful suggestions by the two reviewers. In addition, the previous version of Figure 4B had inverted the association of Clades A and C with HierCC clusters and these inversions were also used in the text. The new Fig. 4B and the modified text has the correct associations of these clades. This opportunity was also used to remove some inadvertent typographical mistakes and improve the flow of several sentences.

Abstract

Background: Most publicly available genomes of Salmonella enterica are from human disease in the US and the UK, or from domesticated animals in the US.

Methods: Here we describe a historical collection of 10,000 strains isolated between 1891-2010 in 73 different countries. They encompass a broad range of sources, ranging from rivers through reptiles to the diversity of all S. enterica isolated on the island of Ireland between 2000 and 2005. Genomic DNA was isolated, and sequenced by Illumina short read sequencing.

Results: The short reads are publicly available in the Short Reads Archive. They were also uploaded to EnteroBase, which assembled and annotated draft genomes. 9769 draft genomes which passed quality control were genotyped with multiple levels of multilocus sequence typing, and used to predict serovars. Genomes were assigned to hierarchical clusters on the basis of numbers of pair-wise allelic differences in core genes, which were mapped to genetic Lineages within phylogenetic trees.

Conclusions: The University of Warwick/University College Cork (UoWUCC) project greatly extends the geographic sources, dates and core genomic diversity of publicly available S. enterica genomes. We illustrate these features by an overview of core genomic Lineages within 33,000 publicly available Salmonella genomes whose strains were isolated before 2011. We also present detailed examinations of HC400, HC900 and HC2000 hierarchical clusters within exemplar Lineages, including serovars Typhimurium, Enteritidis and Mbandaka. These analyses confirm the polyphyletic nature of multiple serovars while showing that discrete clusters with geographical specificity can be reliably recognized by hierarchical clustering approaches. The results also demonstrate that the genomes sequenced here provide an important counterbalance to the sampling bias which is so dominant in current genomic sequencing.

Keywords: Salmonella, Large scale genomic database, High throughput sequencing, Population genomics

Introduction

Salmonella enterica is the one of the four global causes of diarrhoeal diseases in humans ( World Health Organization Fact Sheets, 2018), and has been estimated to be responsible for 94 million annual cases of nontyphoidal gastroenteritis ( Majowicz et al., 2010). Most cases of salmonellosis are mild but the infections can be life-threatening, especially when salmonellosis manifests as typhoid fever caused by serovar Typhi ( Wong et al., 2016), enteric fever due to serovars Paratyphi A or Paratyphi C ( Zhou et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2018b), or extra-intestinal disease with serovars Choleraesuis ( Zhou et al., 2018b) or Typhimurium ( Kingsley et al., 2009; GBD 2017 Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Invasive Disease Collaborators, 2019). S. enterica also infects domesticated animals in large numbers, and was the primary cause of food-borne outbreaks reported in Europe ( European Food Safety Authority, 2007), leading to European regulations intended to reduce the numbers of animal herds contaminated with Salmonella (Regulation (EC) No 2160/2003).

The volume of bacterial genome sequencing is increasing dramatically. Since 2012, unprecedentedly large numbers of Salmonella genomes were sequenced by the Sanger Institute ( Feasey et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2016), the Food and Drug Administration ( Feldgarden et al., 2019), CDC/PulseNet International ( Gerner-Smidt et al., 2019; Nadon et al., 2017) and Public Health England ( Ashton et al., 2016; Waldram et al., 2018). In August 2020, EnteroBase ( Alikhan et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2020a) contained >260,000 Salmonella genomes which had been assembled from sequence reads in the public short read archives, or uploaded by its users. However, the global population genetic diversity of Salmonella encompassed by these genomes is not necessarily representative of total global diversity. Almost all of the bacterial strains were sequenced for epidemiological tracking of the sources of food-borne diseases. Most of them were from human infections in North America and England. Similarly, almost all public Salmonella genomes from domesticated animals are from North America, which causes even greater sample bias.

Serovars Typhi, Paratyphi A and Paratyphi C are specific for humans, and other serovars show signs of adaptation to other hosts ( Baumler et al., 1998; Kingsley & Baumler, 2000). However, only limited data are available for most other serovars and from inter-continental comparisons ( Cheng et al., 2019). We note that S. enterica can be isolated from rivers, ponds and drinking water ( Meinersmann et al., 2008; Uesbeck, 2009; Walters et al., 2011; Walters et al., 2013) as well as salt water ( Mannas et al., 2014; Martinez-Urtaza et al., 2004). Reptiles are often infected by Salmonella ( Corrente et al., 2017; Kanagarajah et al., 2018; Mukherjee et al., 2019; Pulford et al., 2019), and S. enterica strains can invade plant cells, and survive in soil ( Dyda et al., 2020; Jechalke et al., 2019; Schikora et al., 2012). The degree of overlap between bacterial populations from those sources and those that infect humans and animals has not yet been adequately addressed.

These uncertainties raise the following specific questions. Does the natural diversity and broad population structure of S. enterica differ between continents, or by source? Are S. enterica populations uniform across smaller geographic entities with multiple legal entities but continuous contact, such as the island of Ireland? Do isolates from water and reptiles cause gastroenteritis in humans? A broad sampling of Salmonella from diverse geographical sources and multiple hosts is needed to answer these questions, and to counteract the current extreme bias in the public databases of Salmonella genomes.

Between 2007 and 2012, the authors of this manuscript and their colleagues (see Acknowledgements) shared representative isolates of S. enterica from their strain collections with MA at University College Cork in order to address these questions. Single colony isolates were cultivated and stored frozen in robotic instrumentation-friendly vials in microwell-format storage racks. At that time, the primary sequence-based genotyping for large collections was classical MultiLocus Sequence Typing (7-gene MLST) ( Kidgell et al., 2002; Maiden et al., 1998) ( Box 1), and several thousand isolates from the strain collection were subjected to this procedure ( Achtman et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2020a). These analyses did not extend to the entire strain collection, and it has therefore not been previously described in detail. The entire collection accompanied MA to University of Warwick in 2013, and is now being maintained for posterity as “the Achtman collection” by Jay Hinton, University of Liverpool.

Box 1. Explanations of acronyms and specialized designations.

MLST: MultiLocus Sequence Typing in which each sequence variant of a gene is assigned a unique numerical designation. The Sequence Type (ST) is the set of the allelic numbers for an individual strain or genome, and is also assigned a unique ST number. e.g. ST4 might consist of alleles 1 2 1 1 3 5 1. First described for Neisseria meningitidis in 1998 and now extended to a large number of bacterial species ( Jolley et al., 2018).

7-gene MLST ( S. enterica): Classical MLST involving 7 housekeeping genes ( Achtman et al., 2012; Kidgell et al., 2002). STs are grouped together in eBurst Groups (eBGs) based on minimal spanning trees, which correspond to serovars and are curated manually.

wgMLST ( Salmonella): Whole genome MLST based on 21,065 genes from a pan-genome based on 537 representative Salmonella genomes ( Alikhan et al., 2018).

cgMLST ( Salmonella): Core-genome MLST based on a subset of 3002 genes from the wgMLST scheme that were present in ≥98%, intact in ≥94% and of unexceptional diversity in 3144 representative Salmonella genomes ( Alikhan et al., 2018). STs are referred to as cgSTs.

Lineage: A deep branch in a phylogenetic tree which seems to represents a distinct monophyletic group according to visual examination.

HierCC: Single linkage hierarchical clustering of cgSTs based on a maximal internal distance of a certain number of different alleles in pairwise comparisons ( Zhou et al., 2020b). HC100, HC900, HC2000: hierarchical clusters with maximal length of internal branches of 100, 900 and 2000 alleles. HC900 is roughly equivalent to eBGs, but more reliable due to the higher resolution. HC2000 roughly equates to Lineages, except that HC2000 is based on a network approach with a defined algorithm whereas Lineage designations are based on trees and are subjective.

Genomic sequencing of large numbers of samples has recently become feasible even for modestly-sized research groups ( Loman et al., 2012), as documented by the recent sequencing of several thousand genomes from extra-intestinal human infections with non-typhoidal Salmonella in the Americas and Africa ( Perez-Sepulveda et al., 2020). Here we provide an overview of the UoWUCC (University of Warwick/University College Cork) 10K genomes project, in which 9769 S. enterica genomes were sequenced from strains in the Achtman collection in order to address the questions posed above.

Results

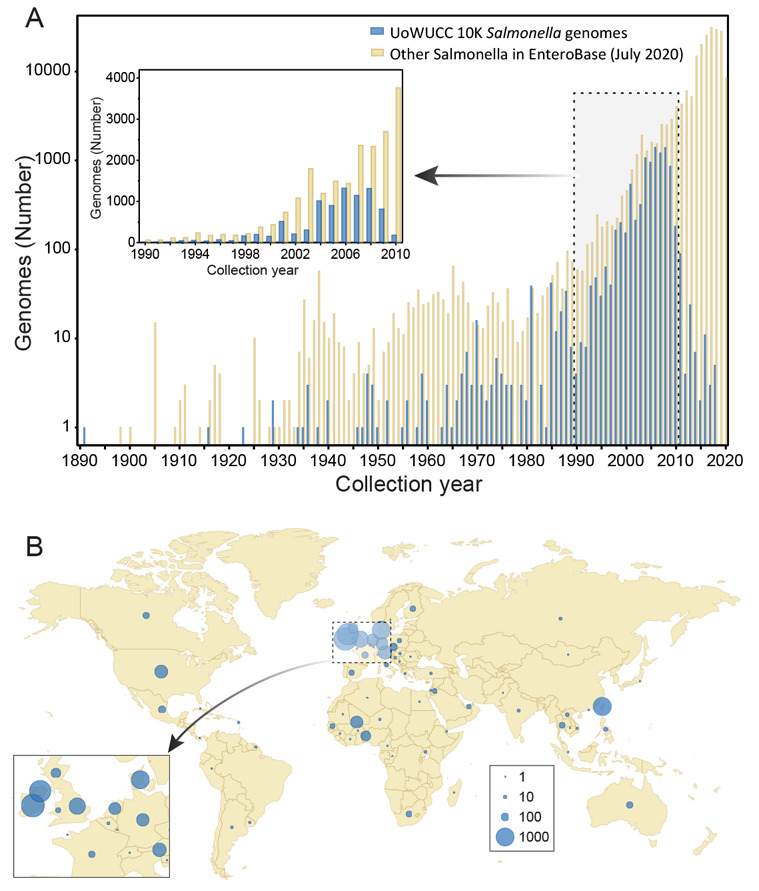

Themes within the 10K genomes project. Table 1 provides an overview of the sources of most of the bacterial isolates whose genomes were sequenced, grouped into sub-collections according to theme. The “Rivers” theme includes 466 isolates from rivers in the United States and England, as well as from drinking water and faecal samples from healthy individuals in central Benin, Africa. The “Ireland” collection of 3880 strains were isolated from humans, livestock and food: 2125 from the Republic of Ireland and 1755 from Northern Ireland. We also sequenced 1131 isolates from Taiwan which represented the PFGE diversity of multiple Salmonella serovars from humans and reptiles. The “Reptiles” theme consisted of 794 other isolates from Austria, Australia, the Netherlands, Germany and Finland from serovars that infect both reptiles and humans. Finally, 3320 isolates were sequenced to cover “General diversity”, including non-Typhi isolates from long-term human carriers in Germany; reference strains for phage types of serovars Enteritidis and Typhimurium; diverse veterinary isolates from England; and Typhimurium from the mesenteric lymph nodes of asymptomatic pigs in Canada. The “General diversity” sub-collection also included members of the SARA and SARB collections as well as human isolates from diverse global sources. The UoWUCC 10K collection spans the time frame from 1891 to 2018 ( Figure 1A), but 94% (9206/9769) of its strains were isolated before 2011. It also spans a wide range of geographic diversity, and the bacteria were isolated from 73 countries on all the continents except Antarctica ( Figure 1B).

Table 1. Sources of 9591 Salmonella isolates that were sequenced within the UoWUCC 10K genomes project.

| Themes and Sources | Number | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Rivers | Total: 466 | |

| A. Boehm (Stanford) | 19 | Central California rivers

( Walters et al., 2011; Walters et al., 2013) |

| R. Meinersmann

(USDA) |

188 | Upper Oconee river,

Georgia ( Meinersmann et al., 2008) |

| A. Uesbeck (Univ. of

Cologne) |

177 | Drinking water in wells

and ponds, Benin ( Uesbeck, 2009) |

| J. Wain (HPA, Colindale) | 82 | Thames River. England |

| Republic of Ireland | Total: 2125 | |

| A. Coffey (CIT) | 61 | Food |

| M. Murphy (Cork

County Vet lab) |

67 | Livestock, County Cork |

| D. Bolton (Teagasc,

AFRC) |

37 | Livestock, bovine |

| D. Prendergast (DAFM) | 479 | Domesticated animals

and food |

| M. Cormican (NSRL,

Galway) |

1126 | Human |

| N. Leonard (UCD,

Dublin) |

317 | Porcine |

| S. Fanning (UCD,

Dublin) |

38 | Environment |

| Northern Ireland | Total: 1755 | |

| J. Moore (Belfast City

Hospital) |

899 | Human |

| S. Strain (AFBI, Belfast) | 449 | Animal Health |

| B. Madden (AFBI,

Belfast) |

407 | Agri-Food |

| Taiwan | Total: 1131 | |

| Chao-Chin Chang

(SVM, NCHU) |

48 | Reptile isolates |

| Chien-Shun Chiou

(CDC) |

1083 | Human isolates |

|

Reptiles and human

isolates of the same serovar |

Total: 794 | |

| C. Kornschober

(Austria) |

366 | Austria |

| D. Gordon (Canberra) | 15 | Australian deserts

( Parsons et al., 2011) |

| X. Huijsdens (RIVM) | 296 | Netherlands |

| R. Helmuth (BfR Berlin) | 85 | Germany ( Achtman et al., 2012) |

| S. Pelkonen (EVIRA,

Finland) |

32 | Finland |

| General diversity | Total: 3320 | |

| Roy Curtiss 3rd | 33 | Human carrier strains,

Germany, 1980s |

| S. Porwollik (SKCC) | 25 | General diversity

( Porwollik et al., 2004) |

| E. De Pinna (HPA) | 90 | Enteritidis Phage type

references, UK ( Ward et al., 1987) |

| H.L. Andrews-

Polymenis |

52 | Typhimurium Phage type

references, Germany ( Andrews-Polymenis et al., 2004) |

| G. Wise (VLA,

Weybridge) |

436 | Animals, England |

| S. Quessy (McGill) | 18 | Mesenteric lymph nodes

from asymptomatic swine, Canada ( Perron et al., 2008) |

| F. Boyd | 61 | Original SARA/SARB

( Achtman et al., 2013) |

| L. Harrison (Univ of

Pittsburgh) |

314 | Humans, Global

( Krauland et al., 2009) |

| J. Wain (HPA, Colindale) | 103 | Humans, England

( Achtman et al., 2012) |

| F.-X. Weill (Institut

Pasteur) |

137 | Humans, France

( Achtman et al., 2012) |

| W. Rabsch (Robert

Koch-Institut, Wernigerode) |

232 | Humans, Germany

( Achtman et al., 2012) |

| Z. Jaradat (JUST,

Jordan) |

23 | Humans, Jordan |

| M. Zaidi (Mexico) | 64 | Humans, Mexico

( Wiesner et al., 2009) |

| R. Kingsley (Sanger) | 389 | Humans, Mali ( Tapia et al., 2015) |

| J. Bouldin (USDA) | 29 | Virulent Enteritidis |

| C. Kornschober

(Austria) |

86 | Boar & Swine,

Choleraesuis, Austria |

| U. Methner (Friedrich-

Loeffler-Institut) |

28 | Boar & Swine,

Choleraesuis, Germany ( Methner et al., 2010) |

| I. Rychlik (VRI, Czech

Republic) |

86 | Human, Typhimurium,

Czech Republic ( Matiasovicova et al., 2007) |

| E. Litrup & M. Torpdahl

(SSI, Denmark) |

1036 | Human, 1 strain

per MLVA type of Typhimurium , Denmark ( Lindstedt et al., 2007) |

| N. Williams (University

of Liverpool - IIGH) |

78 | Badger, Agama |

UowUCC: University of Warwick/University College Cork.

Figure 1. Sources of bacterial isolates for the 10K UoWUCC Salmonella Genomes Project.

A) Semi-logarithmic histogram of numbers of genomes in EnteroBase by year of isolation. Genomes from the 10K project with known dates of isolation are shown in blue and other Salmonella genomes in yellow. Inset: Genomes which were isolated between 1990 and 2010. B) Geographic distribution of sources of isolation. Dot circles are proportional to numbers of strains as indicated in the Key legend at the lower right. Inset: Expanded map of the region near the English Channel.

Sequence reads, genomes, genotypes and metadata. After Illumina short read sequencing (see Methods), the sequence data files were uploaded to the Short Reads Archive at EBI, where they are publicly available for downloading. Genomes were assembled within EnteroBase using its standard pipelines ( Zhou et al., 2020a), and the 9769 genome assemblies that passed stringent quality control criteria ( Figure 2) and manual curation ( Table 2) are publicly available via EnteroBase for inspection, analysis and downloading. EnteroBase also contains the relevant metadata, serovar predictions and MLST genotype assignments for classical 7-gene MLST (STs) ( Achtman et al., 2012; Maiden et al., 1998), ribosomal gene MLST ( Alikhan et al., 2018; Jolley et al., 2012), core genome MLST (cgMLST, cgSTs) ( Alikhan et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2020a) and whole genome MLST ( Zhou et al., 2020a) ( Box 1). The 10K genomes collection is identified by “M. Achtman” in the metadata field “Lab Contact”, and the original sources of the bacterial strains are listed in the metadata field “Comments”.

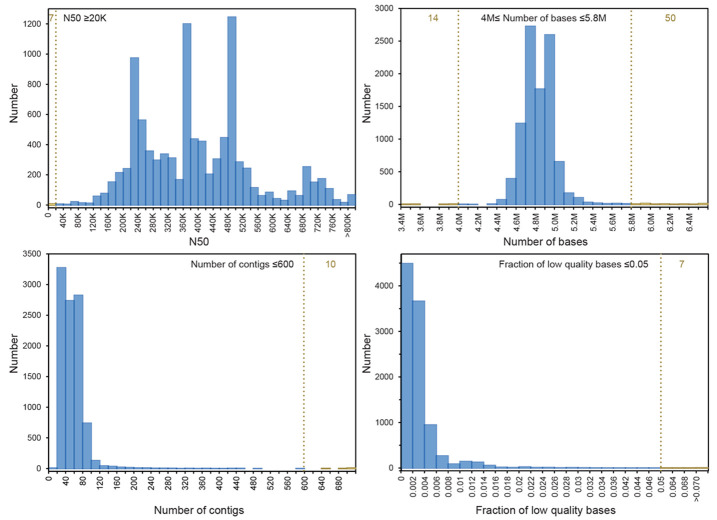

Figure 2. Quality control of 10K genomes.

Default EnteroBase criteria are indicated by vertical dashed lines. Numbers of genomes in the 10K project which passed these cut-off criteria are indicated in blue and failures in yellow, with the total numbers of failures near the tops of the figures in yellow. The quality criteria consisted of N50 ≥20,000, genomic assembly size between 4 MB and 5.8 MB, a maximum of 600 contigs and a low fraction of uncalled, low quality bases (N’s).

Table 2. Summary of the fate of 10,316 sets of short reads.

| Category | Number

of records |

|---|---|

|

Failed Quality

Control |

129 |

|

Mix-up/

contamination |

418 |

| Inconsistent MLST

type |

11 |

| Inconsistent

Serovar |

374 |

| Entire microwell

plate(s) |

33 |

| Final dataset | 9769 |

| Consistent MLST ST | 1801 |

| Consistent serovar | 7713 |

| No independent

verification |

255 |

NOTE: The table ignores 1208 DNA samples which failed quality control at the Sanger Institute, and were not sequenced. New DNAs for 724 of them passed QC and are included in the table.

General overview of population structures. The 10K collection accounts for 28% (9206/33,052) of all Salmonella genomes in EnteroBase (3 Aug 2020) whose strains had been isolated before 2011. Previously, 7-gene MLST STs were clustered in eBurst groups (eBGs) ( Box 1) which correlate strongly with serovar ( Achtman et al., 2012; Alikhan et al., 2018). STs are now being replaced by cgSTs (3002 genes) ( Box 1), which offer a broad range of resolution that is informative over the entire range from epidemiological tracking of micro-clades up to the sub-division of species at the genus level. eBGs are being replaced by hierarchical clusters of cgSTs (HierCC) in which internal branches can differ by up to 900 alleles (HC900 clusters) ( Zhou et al., 2020b) ( Box 1). HC900 clusters provide higher resolution than eBGs, are more accurate and their cgST assignments remain stable even after the addition of large numbers of new genomes ( Alikhan et al., 2018). Figure 3 shows the broad range of core genomic diversity which is present in the 33,052 pre-2011 genomes. These data demonstrate that the 10K genomes are broadly representative of all HC900 clusters in EnteroBase with only few exceptions. The exceptions include serovars Typhi, Paratyphi A and Paratyphi C which were not addressed because they had already been extensively investigated elsewhere ( Wong et al., 2015; Wong et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2018b), and several other serovars were not sequenced because they were rare in the sampled countries.

Figure 3. Genomic diversity of 33,052 pre-2011 genomes in EnteroBase, including 9206 from the 10K genome project (red perimeters).

The figure shows a Ninja NJ ( Wheeler, 2009) tree of the numbers of different alleles between cgSTs as generated within EnteroBase using GrapeTree ( Zhou et al., 2018a). Nodes from 41 common HC900 clusters are indicated by distinct colors, HC900 designations and predominant serovars. Lineages of HC900 clusters are indicated in yellow. The Enteritidis and Typhimurium Lineages are explored in greater detail in Figure 4 and the Mbandaka Lineage in Figure 5. Node sizes are proportional to the numbers of genomes they include. Nodes that include genomes from the 10K genomes project are highlighted by red perimeter. An interactive version can be found at http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/a/46053, in which the user can use other metadata for coloring genomes. Scale bar: 300 alleles.

Similar to eBGs, most HC900 hierarchical clusters are associated with a single predominant serovar. Many HC900 clusters correspond to distinct clades, and share only very few alleles with any other HC900 cluster, resulting in an almost star-like phylogeny for many serovars ( Figure 3). However, some HC900 clusters do share some identical allelic sequences, allowing higher order phylogenetic relationships to be resolved for those lineages ( Box 1). One such Lineage is Lineage 3/Clade B ( Achtman et al., 2012; den Bakker et al., 2011; Didelot et al., 2011; Parsons et al., 2011) which encompasses multiple polyphyletic serovars that undergo inter-serovar recombination. Lineage 3 is clearly delineated in Figure 3, and the data confirm that it encompasses multiple HC900 clusters. The tree confirms other previously described, high level relationships such as the Typhi/Para A Lineage containing HC900 clusters corresponding to serovars Typhi, Paratyphi A and Sendai ( Didelot et al., 2007), and the Para C Lineage containing HC900 clusters corresponding to serovars Paratyphi C, Choleraesuis, Typhisuis, Lomita and Birkenhead ( Key et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2018b). However, Figure 3 aalso includes other poorly described, higher order lineages that each encompass multiple HC900 clusters and their serovars, including the Typhimurium and Enteritidis Lineages.

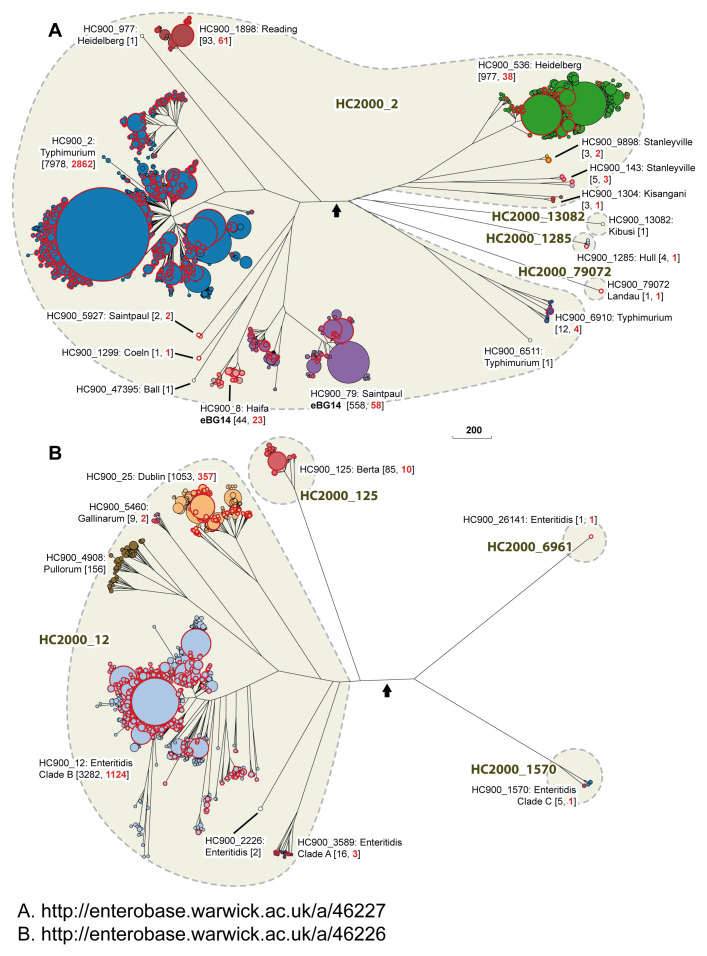

Typhimurium Lineage. In 1991, the SARA strain collection of 72 representatives of the so-called “S. typhimurium complex” was chosen on the basis of multilocus enzyme electrophoretic typing ( Beltran et al., 1991). SARA includes representatives of serovars Typhimurium, Saintpaul, Heidelberg, Paratyphi B/Java and Muenchen. The Typhimurium Lineage defined by cgMLST also encompasses serovars Typhimurium, Saintpaul, and Heidelberg ( Figure 3), but not Paratyphi B/Java or Muenchen, which are quite distinct in Maximum Likelihood trees of core SNPs ( Zhou et al., 2018b). The genomes in the Typhimurium Lineage define multiple HC2000 hierarchical clusters: HC2000_2, HC2000_13082, HC2000_1285 and HC2000_79072 ( Box 1) ( Figure 4A). Many of the serovars in the Typhimurium Lineage are polyphyletic, and fall into multiple HC900 clusters within HC2000_2 (Typhimurium: HC900_2, HC900_6511 and HC900_6910; Heidelberg: HC900_536, HC900_977; Saintpaul: HC900_79, HC900_5927; Stanleyville: HC900_143, HC900_9898), which are intermingled in the tree with still other HC900 clusters of serovars Reading, Coeln, Ball, Haifa, and Kisangani ( Figure 4A). The other HC2000 clusters include a few strains each from serovars Kibusi, Hull and Landau, and each consists of a single HC900 cluster. MLST clustering of Salmonella based on assignments to 7-gene STs ( Achtman et al., 2012) has been widely used ( Bawn et al., 2020; Cheng et al., 2019). The resolution of such MLST typing is limited and the relationship of STs to HierCC clusters is not necessarily uniform. For example, almost all HC900_1898 (Reading) genomes belong to ST1628, and almost all HC900_536 (Heidelberg) genomes are ST15. However, HC900_79 (Saintpaul) contains multiple common STs (27, 50, 680 and others). And the main Typhimurium cluster, HC900_2, is predominantly ST19 but also contains ST34, ST36, and ST313, which correspond to distinct HC100 or HC400 internal clusters. We conclude that the results presented here provide an unprecedented overview of the high order population structure of the Typhimurium Lineage and note that additional analyses will be needed to elucidate the internal structure of individual HC900 clusters at higher resolution. Our preliminary analyses indicated that the evolutionary history of HC2000_2 is likely to have been complicated and involved multiple recombinational events. Elucidating this history will be facilitated by the genomes in the 10K genomes collection because they straddle the entire diversity just described.

Figure 4.

Detailed representations of HC 2000 and 900 clusters in the Typhimurium Lineage ( A) and the Enteritidis Lineage ( B). Each consists of a NINJA NJ tree of the subset of nodes encompassed by the corresponding Lineages from the tree in Figure 3. The figure indicates HC2000 clusters in larger font and gray shading. Designations for individual HC900 clusters and their predominant serovar include the total number of isolates (black) and the number from the 10K genomes project (red) in parentheses. In part B, Clade A and C designations from citations ( Graham et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2020) are indicated for HC900_3589 and HC2000_1570, respectively. Interactive versions can be found at http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/a/46227 ( A) and http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/a/46226 ( B), in which the user can use other metadata for coloring genomes. Black arrowheads: tree root. Scale bar: 200 alleles.

Enteritidis Lineage. The Enteritidis Lineage ( Figure 3) includes one predominant HC2000 cluster, HC2000_12, as well as three smaller HC2000 clusters. HC2000_12 includes HC900_12, which contains most of the genomes of serovar Enteritidis strains from Europe, North America and Africa, as well as one HC900 cluster for each of the related serovars ( Feasey et al., 2016; Langridge et al., 2015) Gallinarum (HC900_5460), Pullorum (HC900_4908) and Dublin (HC900_25) ( Figure 4B). HC2000_12 also includes two other HC900 clusters of serovar Enteritidis (HC900_2226 and HC900_3589), which are more distinct from HC900_12, the major Enteritidis cluster, than are the Pullorum, Gallinarum or Dublin clusters. The Enteritidis Lineage contains a second HC2000 cluster for serovar Berta (HC2000_125), and two additional clusters of Enteritidis (HC2000_6961, HC2000_1570).

Recent analyses have separated Enteritidis into clade B, which corresponds to HC900_12, and two other distinct clades of Enteritidis, A and C, which are common in Australia ( Graham et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2020). (These were originally referred to as lineages but clades are substituted here to prevent confusion with the Lineages in Figure 3). Clade A corresponds to HC900_3589, which is part of HC2000_12, and clade C to HC2000_1570 ( Figure 4B). There are currently a total of five Enteritidis clades within the Enteritidis Lineage ( Figure 4B). Similar to the Typhimurium Lineage, Enteritidis and related serovars are polyphyletic and likely reflect a complicated evolutionary history.

The 10K genomes are distributed across the breadth of the entire Enteritidis lineage, except for Pullorum, which has largely been eradicated from the countries that were sampled ( Le Bouquin et al., 2020). Interestingly, the 10K genomes collection also includes old isolates of Enteritidis clades A and C which are currently particularly common in Australia. Strain E2387 in HC2000_1570 (clade C) is the original reference strain for phage type PT14, and was isolated in England in 1968, long before any descriptions of clade C in Australia. The 10K collection also includes three older strains in HC900_3589 (clade A): strain P106993, the reference strain for PT26, was isolated in England in 1987, and the recent Australian clade A isolates were also PT26. Two other HC900_3589 strains were isolated from snakes in Germany in 2002 and 2003. Similarly, the sole genome in HC2000_6961 is the reference strain for PT11b, strain PT187803, which was isolated in Canada in 1989.

Similar to Typhimurium, the primary Enteritidis cluster, HC900_12 largely consists of a single 7-gene ST, ST11. According to cgMLST and HierCC, most HC900_12 genomes are associated with HC100_87 and HC100_12, but it also contains at least eight additional, distinct tight clusters (HC100_12675, 2452, 13575, 447, 12703, 1522, 1404, 31939). Some of these correspond to 7-gene STs such as ST136 (HC200_12703) and ST183 (HC200_1404) ( Achtman et al., 2012; Langridge et al., 2015) or the geographically associated Enteritidis lineages within SNP trees designated as the Central/Eastern Africa (HC100_12675) and West African (HC100_2452) lineages ( Feasey et al., 2016). The others do not seem to have been previously described. Once again, the availability of the UoWUCC genomes will assist future reconstructions of global diversification and dispersion of individual lineages.

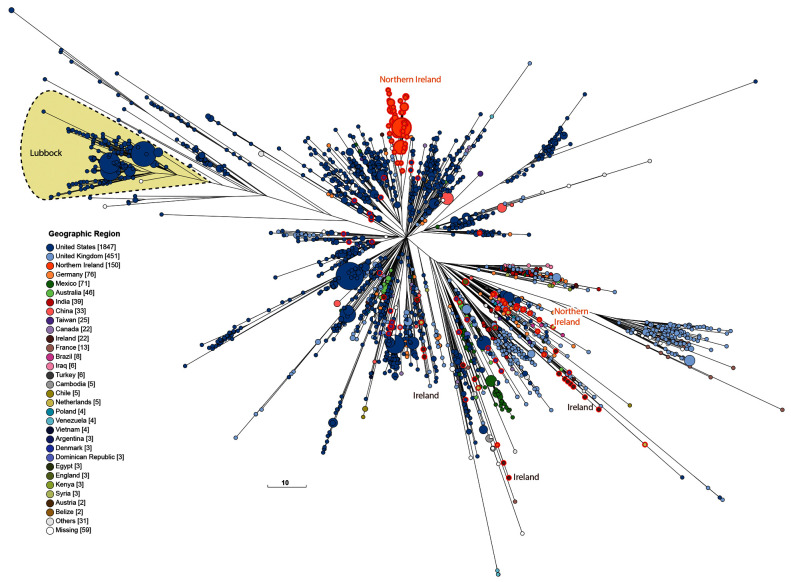

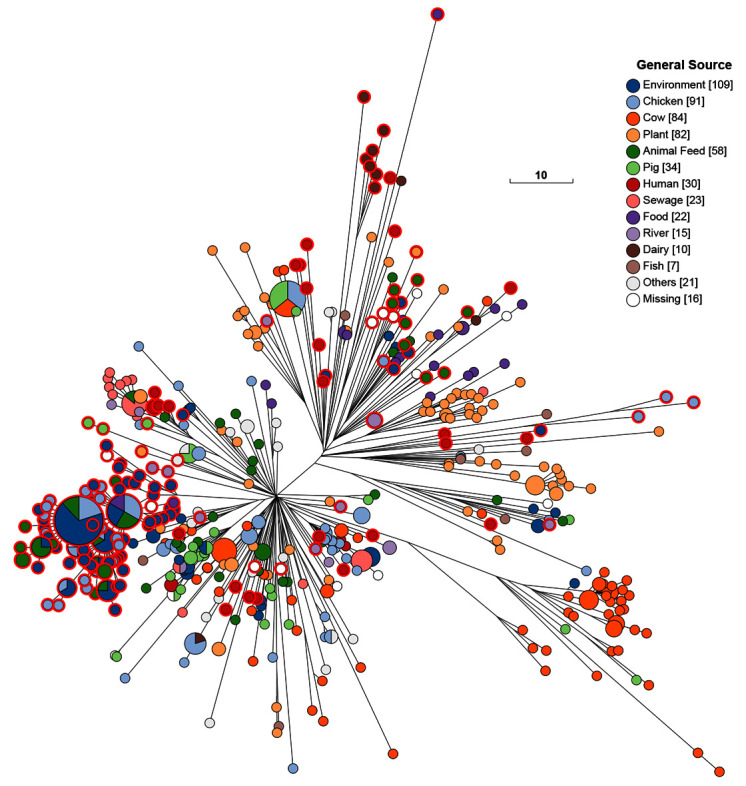

Mbandaka Lineage. The 10K genomes are also likely to be useful for fine-scale analyses within clades with even more limited genetic diversity. We provide an initial example of this utility by zooming in on the Mbandaka Lineage ( Figure 3). Serovar Mbandaka was first isolated in 1948 but has now become a common source of salmonellosis in humans in the EU and elsewhere ( Cheng et al., 2019; Hoszowski et al., 2016). Examination of the sources of the genomes of the Mbandaka Lineage up to 2010 ( Figure 5) provides a different perspective because most were from environmental samples, animal feed, sewage, rivers and dairy products with a smaller proportion from chickens, cows, plants, pigs and humans ( Figure 6). Thus, Mbandaka seems to be commonly shed to the environment by livestock rather than being a primary human pathogen.

The Mbandaka Lineage shows so little diversity that almost all of its genomes are included in the tight HC100_4 cluster ( Figure 5 and Figure 6), which has a maximal internal branch length of 100 different alleles. Mbandaka cgMLST genotypes cluster very tightly by geographic source and by host, yielding fairly uniform clusters of isolates from cows, plants, dairy products, and chicken farms (chickens plus environmental swabs) ( Figure 6). In 2015, a recombinational variant of Mbandaka was designated as serovar Lubbock ( Bugarel et al., 2015). Figure 7 shows the current composition of HC100_4, in which Lubbock constitutes a micro-clade. Even today, almost all clades are country-specific, but each country contains multiple micro-clades.

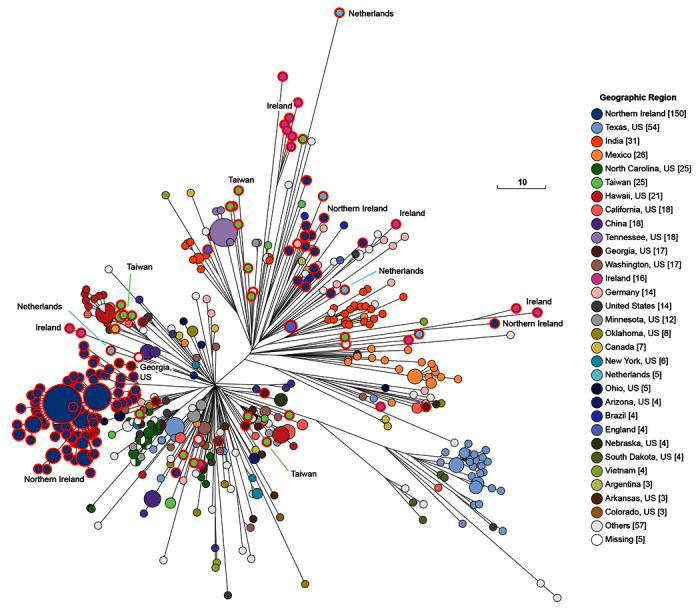

Figure 5. Genomic diversity of 601 pre-2011 genomes from HC100_4 of which 208 were from the 10K genomes project (red perimeters).

The figure shows a Ninja NJ ( Wheeler, 2009) tree of the numbers of different alleles between cgSTs as generated within EnteroBase using GrapeTree ( Zhou et al., 2018a). The geographical sources of some of the isolates from the 10K genomes project are indicated to demonstrate that multiple micro-clades were present in individual countries. An interactive version can be found at http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/a/46139, in which the user can use other metadata for coloring genomes. The same tree colored by general source can be found in Figure 6 and a tree showing all modern Mbandaka and Lubbock genomes can be found in Figure 7. Scale bar: 10 alleles. Color Key at right.

Figure 6. As Figure 5, except that the nodes are colored by general source.

The 10K genomes project provided 25% (208/601) of the H100_4 genomes in EnteroBase that were isolated prior to 2011. These 208 genomes were from multiple themes in Table 1, from diverse geographical sources, and were scattered throughout the cgST tree among isolates from other global sources ( Figure 5). Most of the 16 Mbandaka bacterial strains from the Republic of Ireland were from dairy products, humans and pigs. Northern Ireland was the source of 151 other Mbandaka strains, predominantly from chicken farms and animal feed. Multiple micro-clades from each of these two geographic sources were inter-dispersed among other Mbandaka genomes. However, the genomes from Ireland did not cluster together with those from Northern Ireland even though their geographic sources are at most a few hundred kilometers apart. Exceptionally, one genome from Ireland (a chicken isolate) clustered tightly with genomes from Northern Ireland. The primary clades found in Ireland and Northern Ireland were not found in any other country, and they have remained genetically discrete from other geographical sources up to recent times (18 Aug 2020) when HC100_4 contained 2955 genomes of serovars Mbandaka and Lubbock ( Figure 7). Most of the additional strains isolated since 2011 are from the US or the UK, and show broad continental specificity, interspersed with the isolates from the 10K collection which are spread throughout the entire Mbandaka tree.

Figure 7. Genomic diversity of 2955 genomes from HC100_4 from EnteroBase (18/08/2020) of which 208 were from the 10K genomes project (red perimeters).

The figure shows a Ninja NJ ( Wheeler, 2009) tree of the numbers of different alleles between cgSTs as generated within EnteroBase using GrapeTree ( Zhou et al., 2018a). The geographical sources of all isolates are color-coded (Key at lower left) and the location of serovar Lubbock is shaded. Unshaded isolates are serovar Mbandaka. An interactive version can be found at http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/a/46122, in which the user can use other metadata for coloring genomes. Scale bar: 10 alleles.

Discussion

One Health approach. MA initiated a broadly-based collection of Salmonella from diverse sources in 2008. At the same time, the One Health Initiative ( Kahn et al., 2020) independently proposed combining global epidemiological and other information about pathogens that originated from human and animal infections, as well as from the environment. For the last few years, comparisons of bacterial isolates from multiple sources have been pursued for Salmonella and other food-borne pathogens by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States, which has sequenced numerous bacterial strains isolated from plants and the environment in addition to food samples. The FDA has also been exemplary in sequencing genomes from around the globe, and in establishing the GenomeTrakr website to provide access to those genomes and their properties ( Timme et al., 2019). GenomeTrakr also includes numerous genomes of human isolates that have been sequenced by the Sanger Institute and the CDC. Unfortunately, most of these entries lack the metadata required to inferface with information from food and environmental sources. The genome sequencing efforts by Public Health England since 2015 are also highly laudable, and they publish short reads together with the corresponding metadata from all human Salmonella isolates from England and Wales in the ENA Sequence Reads Archives ( Ashton et al., 2016; Waldram et al., 2018). However, very few genomes of Salmonella from non-human sources in England are publicly available, and the rest of Europe is only now beginning to sequence and publish genomic sequence reads and their metadata. Furthermore, most European countries continue to maintain separate networks of laboratories for isolates from humans and from domesticated animals or food, with the two networks being separately coordinated by ECDC and EFSA. These two organisations have not yet implemented universal genomic sequencing (EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) and ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control), 2019; ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control) et al., 2019), and are not yet actively supporting it. Thus, the aims of the One Health Initiative are not being adequately met for Salmonella, and the completion of the UoWUCC 10K Salmonella genomes project is a major step forward towards those goals.

Accuracy. According to our experience, a few percent of isolates from all reference/diagnostic laboratories are incorrectly serotyped ( Achtman et al., 2012). Sporadic curation of EnteroBase has also revealed numerous instances where the metadata in the short read archives were inconsistent with the serovars that were predicted from the assembled sequences. Such discrepancies likely reflect laboratory mistakes or typographical errors and/or data transmission glitches. We manually curate such discrepancies in EnteroBase when we notice them. In several cases we have deleted the genomes. However, we usually simply replace obviously false serovars with the predicted serovars from the genomic assemblies ( Robertson et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019), and currently almost 20% of the serovar metadata for Salmonella in EnteroBase are based on such predictions. For other cases we have replaced false metadata with the corresponding published data, e.g. for the Murray collection ( Baker et al., 2015).

The SARA ( Beltran et al., 1991) and SARB ( Boyd et al., 1993) collections are invaluable reference sets for the genetic diversity of the serovars that they represent, but these collections are badly contaminated in multiple laboratories ( Achtman et al., 2013), and many of their supposed genomes in the public domain were sequenced from contaminants. We sequenced a clean set of those strains ( Achtman et al., 2013), and ensured that public genomes from contaminated variants were either deleted from EnteroBase, or were relegated to the category of sub-strains ( Zhou et al., 2020a), which are not visible without special intent. However, there are too many sets of short reads in the public domain to manually correct all of them, and EnteroBase perpetuates numerous false metadata that accompanied short reads.

The metadata for the 10K genomes are much more accurate than is the rule for public genomes because we manually curated them for plausibility (see Methods), and only those that survived curation remain in EnteroBase ( Table 2). As a result, the 10K genomes are likely to contain fewer mistaken combinations of genomes and metadata than has been the norm.

Historical reconstructions. Possibly scientists that focus on contemporary outbreaks of human salmonellosis might argue that the 10K genomes are irrelevant because almost all those strains were isolated before 2011, and many even date back to the 1980s and earlier. Instead, many previous analyses of population patterns have been biased to isolates from a single country and/or a narrow range of years of isolation. A broad resource of older genomes will provide the historical background needed to reconstruct evolutionary patterns over decades and possibly even over centuries. For example, it was only possible to describe the evolutionary history over millennia of a Salmonella branch that includes serovar Paratyphi C ( Key et al., 2020) because rare serovars had been sequenced within the 10K genomes project.

Several other dramatic examples of the value of historical isolates are provided here, e.g. old reference strains for phage types of Enteritidis from Europe that predated by decades the dates that related bacteria were isolated in Australia. Many public health laboratories are forced to discard older strains due to space constrictions, e.g. the clinical strains from the Republic of Ireland are no longer available except within the Achtman collection.

Geographical diversity. The strains analysed here are not only old; they also represent unique diversity that is not otherwise represented among the >275,000 Salmonella genomes currently in EnteroBase. One example are genomes of Agama from badgers in Woodchester Park in England, which are uniquely represented by genomes within this project and allowed the reconstruction of transmission chains between neighboring setts ( Zhou et al., 2020a). Another important example is Mbandaka from chickens and chicken farms in Northern Ireland in the early 2000s. The only Mbandaka genomes in EnteroBase that stem from Northern Ireland are the 152 genomes in the 10K project, and in 2020 they still differed from all 2800 other Mbandaka/Lubbock genomes in EnteroBase

Does natural diversity of S. enterica differ between continents, or by source? S. enterica is a transmissible pathogen with multiple hosts. We therefore expected the 10K Genomes project to provide multiple additional examples of global transmissions and spread from diverse zoonotic and environmental sources to humans. One such example was finding old isolates of Enteritidis clades in Europe that were thought to be specific to Australia. Unexpectedly, we also found support for geographic and host-specificity, for example a specific clade of Mbandaka isolates among chickens in Ireland.

EnteroBase contains >275,000 Salmonella genomes, but most of them are from common serovars infecting humans in the US and the UK. The 10K genomes project has added numerous additional details to the global genetic and genomic diversity of Salmonella. In turn, that additional diversity warrants an extensive investigation of the entire dataset. However, such an ambitious project would exceed the capabilities of a small group of scientists, including the authors of this report on their own. We therefore heartily invite the entire global Salmonella community to join in this investigation.

Methods

Bacterial isolates. S. enterica isolates from multiple sources were collected at University College Cork by MA from 2008–2012, and their metadata were stored in a BioNumerics (Biomerieux) database. The metadata included country, year, and source of isolation, but none of the details that might allow identification of individual farms or people from whom they were isolated. No ethical permissions are required for transfer of such bacterial samples.

Microbiological cultivation was performed as described in detail elsewhere ( O'Farrell et al., 2012). Isolated single bacterial colonies were used to inoculate 1.4 ml growth/freezing medium in 2-D bar-coded, screw-capped FluidX tubes ( O'Farrell et al., 2012) whose physical locations were stored in an ItemTracker database. These tubes were grown overnight with shaking at 37°C, and stored at -80°C. All subsequent operations were performed with automated microbiology as described ( O'Farrell et al., 2012). Cross-contamination from other tubes with these automated methods is not detectable in the sub-cultures, but can occur at a frequency of 1/500 in the parental tubes. Therefore, whenever the stock tubes were used for DNA isolation of a particular isolate, the most recently frozen serial sub-culture was used to inoculate one new subculture for freezing and storage as well as a second subculture for DNA isolation. DNA was isolated from many of these strains, and subjected to classical 7-gene multilocus sequence typing (MLST) ( Achtman et al., 2012; Achtman et al., 2013; O'Farrell et al., 2012).

The strain collection, robotic equipment and databases accompanied MA to the University of Warwick in 2013, where the same procedures were implemented, except that DNA isolation was performed with a Qiagen QiaCube. We chose over 10,000 isolates of S. enterica for genome sequencing ( Table 1 and Table 2), with priority given to isolates whose DNA had previously been isolated and 7-gene MLST performed. Once those samples had been processed, DNAs were isolated from additional strains in the collections in Table 1. DNA concentrations were calibrated with Pico Green fluorescence to ensure that each sample contained at least 400 ng of DNA. Each sample was diluted into two 0.5 ml FluidX screw-capped, 2-D bar-coded tubes. One set of duplicate tubes was shipped to the Sanger Institute, Hinxton, UK for draft genome sequencing, and the second was maintained as a reserve at University of Warwick.

Draft genome sequencing. At the Sanger Institute, DNA samples were quantified once again, with a Biotium Accuclear Ultra high sensitivity dsDNA Quantitative kit using a Mosquito LV liquid handler, an Agilent Bravo WS automation system and a BMG FLUOstar Omega plate reader. DNAs which passed quality control were cherry-picked and diluted to 200 ng in 120 µl using a Tecan liquid handling platform. The microwell plates containing cherry-picked DNAs were sheared to 450 bp using a Covaris LE220 instrument.

Sheared samples were purified on the Agilent Bravo WS using Agencourt AMPure XP SPRI beads on a Beckman BioMek NX96 liquid handling platform. Library construction (end-repair, adapter-tailing and ligation) were then performed with an NEB Ultra II custom kit (Agilent Bravo WS), followed by PCR reactions to generate sequencing libraries using Kapa HiFi Hot start mix (Kapa Biosystems) and IDT 96 iPCR tag barcodes (IDT). The PCR cycles were: 95°C for 5 minutes; 6 cycles of 98°C for 30 seconds, 65°C for 30 seconds and 72°C for 2 minutes and were terminated by incubation at 72°C for 5 minutes. The IDT 96 iPCR barcodes consisted of the first 96 primers in the 384 set in Supplementary table S1 of Quail et al. ( Quail et al., 2014). The resulting DNA was then purified again using Agencourt AMPure XP SPRI beads and quantified with the Biotium Accuclear Ultra high sensitivity dsDNA Quantitative kit. Libraries were pooled in equimolar amounts, 384 at a time, using a Beckman BioMek NX-8 liquid handling platform. The pooled libraries were normalised to 2.8 nM prior to cluster generation on an Illumina cBOT, and were then sequenced with paired ends (2 × 150 bp) on one lane of an Illumina HiSeq X 10.

Post-sequencing procedures. Sets of short reads were extracted from the storage system at the Sanger Institute with the “path-find” module ( Bio-Path-Find), and uploaded into EnteroBase together with the corresponding metadata that had been stored in the BioNumerics database. The short reads were assembled by EnteroBase using the then current backend pipelines (versions 3.61 - 4.1) ( Zhou et al., 2020a). For those strains where 7-gene MLST had been performed, we also created an identical sub-strain except that the experimental field in EnteroBase for 7-gene MLST data was filled from the data in the BioNumerics database.

Manual curation. Manual curation of the assembled genomes was performed within EnteroBase to generate the most accurate dataset that was possible. Where the data were available, we compared the genome-derived predictions for each isolate with serotype assignments from laboratory experiments and/or historical MLST data. To this end, we created a custom view and user-defined fields that contained an arbitrary sequential Plate number for each rack of 96 tubes (95 DNAs plus a blank in microwell format, i.e. from A1 to H12) and information on the rows and columns of the tubes as well as their barcodes. We created one workspace for all the strains and their sub-strains for each microwell rack. 7-gene MLST data from the older ABI-based sequence data were compared with 7-gene MLST predictions from the genome assemblies. In initial comparisons, discrepancies between the two sources of data were pursued by inspecting the original sequence traces. However, all discrepancies reflected false calls of the ABI data. Thereafter, we treated discrepancies of up to one allele as indicating consistency, and discarded genomes with discrepancies of 2-7 alleles. For genomes without prior 7-gene MLST data, we compared the serovar based on agglutination tests with the serovars predicted from the genomic assemblies by SeqSero2 ( Zhang et al., 2019), SISTR1 ( Robertson et al., 2018) and 7-gene MLST eBurstGroups (eBGs) ( Achtman et al., 2012). Discrepancies were examined for plausibility according to antigenic formulas ( Grimont & Weill, 2007), and genomes with gross discrepancies were discarded. Some 255 genomes lacked metadata on serovar but the remaining metadata on source and year of isolation was considered reliable, and these were kept despite the lack of independent confirmation of a lack of contamination. The numbers in these different categories are summarized in Table 2.

After excluding 129 assembled genomes that failed EnteroBase quality control criteria and 418 genomes with dramatically discrepant 7-gene MLST sequence types and/or serovar ( Table 2), we retained genomes from 9769 strains from the 10K collection ( http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/a/45743). The short sequence reads of the final set of strains were deposited in EBI.

Analysis. All analyses were performed within EnteroBase with the tools that were described by Zhou et al., ( Zhou et al., 2020a), as specified in the figure legends. All trees were created with the version of GrapeTree ( Zhou et al., 2018a) that is integrated into EnteroBase, and can be interactively interrogated within EnteroBase.

Data availability

Underlying data

Short read sequences are available for public access at the Short Reads Archive (SRA) at EBI under BioProject accessions PRJEB20997 and PRJEB33949.

NCBI BioProject: Salmonella enterica ancient DNA and modern demography. Accession number: PRJEB20997

NCBI BioProject: EnteroBase - User Uploads from M. Achtman to EnteroBase Salmonella database. Accession number: PRJEB33949

All other data is available for public access in EnteroBase http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk in the Salmonella database. Individual strains and genomes from this project can be located with the same BioProject accession codes and also by the metadata field containing the text “M. Achtman”. All the analyses described were performed with software that are available within EnteroBase. Access to the individual trees with the option of colour-coding by other metadata is publicly accessible at:

Figure 3: http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/ms_tree/46053;

Figure 4A: http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/ms_tree/46227;

Figure 4B: http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/ms_tree/46226;

Figure 5, 6: http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/ms_tree/46139;

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the receipt of additional bacterial strains from Gail Wise, VLA – Weybridge, UK; Beverley C. Millar, Northern Ireland Public Health Laboratory, Belfast, UK; Finola Leonard, UCD, Dublin, Ireland; Lee Harrison, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh PA; John Wain, PHE – Colindale, UK; Mary Murphy, Veterinary Food Safety Laboratory, Inniscarra, Co. Cork, Ireland; David Gordon, Research School of Biology, ANU, Canberra, Australia; Elizabeth de Pinna, PHE – Colindale, UK; Declan Bolton, Ashtown Food Research Center, Teagasc, Dublin, Ireland; Ulrich Methner, Friedrich-Loeffler Institut, Jena, Germany; Alexandria B. Boehm, Stanford University, CA. We gratefully acknowledge technical assistance with cultivation of these bacteria at UCC by Ronan Murphy. This manuscript also benefited from the comments by the two reviewers.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust through a Investigator in Science Award to MA [202792]. This work was also supported by the Science Foundation of Ireland [05/FE1/B882 to MA]. RM is supported by USDA Agricultural Research Service Project [6040-32000-009-00-D]. Bacterial strains from Belfast City Hospital were from the Northern Ireland HSC Microbiology Culture Repository (MicroARK), Northern Ireland Public Health Laboratory and funded by the HSC Research & Development Office.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 2; peer review: 2 approved]

References

- Achtman M, Hale J, Murphy RA, et al. : Population structures in the SARA and SARB reference collections of Salmonella enterica according to MLST, MLEE and microarray hybridization. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;16C:314–325. 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achtman MA, Wain J, Weill FX, et al. : Multilocus sequence typing as a replacement for serotyping in Salmonella enterica. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(6):e1002776. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alikhan NF, Zhou Z, Sergeant MJ, et al. : A genomic overview of the population structure of Salmonella. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(4):e1007261. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews-Polymenis HL, Rabsch W, Porwollik S, et al. : Host restriction of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium pigeon isolates does not correlate with loss of discrete genes. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(9):2619–2628. 10.1128/jb.186.9.2619-2628.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton PM, Nair S, Peters TM, et al. : Identification of Salmonella for public health surveillance using whole genome sequencing. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1752. 10.7717/peerj.1752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker KS, Burnett E, McGregor H, et al. : The Murray collection of pre-antibiotic era Enterobacteriacae: a unique research resource. Genome Med. 2015;7:97. 10.1186/s13073-015-0222-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumler AJ, Tsolis RM, Ficht TA, et al. : Evolution of host adaptation in Salmonella enterica. Infect Immun. 1998;66(10):4579–4587. 10.1128/IAI.66.10.4579-4587.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawn M, Alikhan NF, Thilliez G, et al. : Evolution of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium driven by anthropogenic selection and niche adaptation. PLoS Genet. 2020;16(6):e1008850. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran P, Plock SA, Smith NH, et al. : Reference collection of strains of the Salmonella typhimurium complex from natural populations. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137(3):601–606. 10.1099/00221287-137-3-601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd EF, Wang FS, Beltran P, et al. : Salmonella reference collection B (SARB): strains of 37 serovars of subspecies I . J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139 Pt 6:1125–1132. 10.1099/00221287-139-6-1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugarel M, den Bakker HC, Nightingale KK, et al. : Two Draft Genome Sequences of a New Serovar of Salmonella enterica, Serovar Lubbock. Genome Announc. 2015;3(2):e00215–606. 10.1128/genomeA.00215-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng RA, Eade CR, Wiedmann M: Embracing Diversity: Differences in Virulence Mechanisms, Disease Severity, and Host Adaptations Contribute to the Success of Nontyphoidal Salmonella as a Foodborne Pathogen. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1368. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrente M, Sangiorgio G, Grandolfo E, et al. : Risk for zoonotic Salmonella transmission from pet reptiles: A survey on knowledge, attitudes and practices of reptile-owners related to reptile husbandry. Prev Vet Med. 2017;146:73–78. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2017.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Bakker HC, Moreno Switt AI, Govoni G, et al. : Genome sequencing reveals diversification of virulence factor content and possible host adaptation in distinct subpopulations of Salmonella enterica. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:425. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didelot X, Achtman M, Parkhill J, et al. : A bimodal pattern of relatedness between the Salmonella Paratyphi A and Typhi genomes: convergence or divergence by homologous recombination? Genome Res. 2007;17(1):61–68. 10.1101/gr.5512906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didelot X, Bowden R, Street T, et al. : Recombination and population structure in Salmonella enterica. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(7):e1002191. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyda A, Nguyen PY, Chugtai AA, et al. : Changing epidemiology of Salmonella outbreaks associated with cucumbers and other fruits and vegetables. Global Biosecurity. 2020;1(3). Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control), . EFSA (European Food Safety Authority), . Van Walle I, et al. : EFSA and ECDC technical report on the collection and analysis of whole genome sequencing data from food-borne pathogens and other relevant microorganisms isolated from human, animal, food, feed and food/feed environmental samples in the joint ECDC–EFSA molecular typing database.2019;16(5):1337E 10.2903/sp.efsa.2019.EN-1337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) and ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control): The European Union One Health 2018 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2019;17(12):e05926. 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority: The Community Summary Report on Trends and Sources of Zoonoses, Zoonotic Agents, Antimicrobial Resistance and Foodborne Outbreaks in the European Union in 2006. European Food Safety Authority. 2007;5(12):130r 10.2903/j.efsa.2007.130r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feasey NA, Hadfield J, Keddy KH, et al. : Distinct Salmonella Enteritidis lineages associated with enterocolitis in high-income settings and invasive disease in low-income settings. Nat Genet. 2016;48(10):1211–1217. 10.1038/ng.3644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldgarden M, Brover V, Haft DH, et al. : Validating the AMRFinder Tool and Resistance Gene Database by Using Antimicrobial Resistance Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in a Collection of Isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63(11):e00483–19. 10.1128/AAC.00483-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerner-Smidt P, Besser J, Concepción-Acevedo J, et al. : Whole Genome Sequencing: Bridging One-Health Surveillance of Foodborne Diseases. Front Public Health. 2019;7:172. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2017 Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Invasive Disease Collaborators: The global burden of non-typhoidal Salmonella invasive disease: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(12):1312–1324. 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30418-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham RMA, Hiley L, Rathnayake IU, et al. : Comparative genomics identifies distinct lineages of S. Enteritidis from Queensland, Australia. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191042. 10.1371/journal.pone.0191042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimont PA, Weill FX: Antigenic formulae of the Salmonella serovars, 9th edition edition. WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella, Paris, France.2007. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Hoszowski A, Zajac M, Lalak A, et al. : Fifteen years of successful spread of Salmonella enterica serovar Mbandaka clone ST413 in Poland and its public health consequences. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23(2):237–241. 10.5604/12321966.1203883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jechalke S, Schierstaedt J, Becker M, et al. : Salmonella establishment in agricultural soil and colonization of crop plants depend on soil type and plant species. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:967. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley KA, Bliss CM, Bennett JS, et al. : Ribosomal multilocus sequence typing: universal characterization of bacteria from domain to strain. Microbiology(Reading). 2012;158(Pt 4):1005–1015. 10.1099/mic.0.055459-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley KA, Bray JE, Maiden MC: Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications [version 1; peer review: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:124. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn LH, Kaplan B, Monath TP, et al. : History of the One Health Initiative team and website.2020. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Kanagarajah S, Waldram A, Dolan G, et al. : Whole genome sequencing reveals an outbreak of Salmonella Enteritidis associated with reptile feeder mice in the United Kingdom, 2012-2015. Food Microbiol. 2018;71:32–38. 10.1016/j.fm.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key FM, Posth C, Esquivel-Gomez LR, et al. : Emergence of human-specific Salmonella enterica is linked to the Neolithization process. Nat Ecol Evol. 2020;4(3):324–333. 10.1038/s41559-020-1106-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidgell C, Reichard U, Wain J, et al. : Salmonella typhi, the causative agent of typhoid fever, is approximately 50,000 years old. Infect Genet Evol. 2002;2(1):39–45. 10.1016/s1567-1348(02)00089-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley RA, Baumler AJ: Host adaptation and the emergence of infectious disease: the Salmonella paradigm. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36(5):1006–1014. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01907.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley RA, Msefula CL, Thomson NR, et al. : Epidemic multiple drug resistant Salmonella Typhimurium causing invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa have a distinct genotype. Genome Res. 2009;19(12):2279–2287. 10.1101/gr.091017.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauland MG, Marsh JW, Paterson DL, et al. : Integron-mediated multidrug resistance in a global collection of nontyphoidal Salmonella enterica isolates. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(3):388–396. 10.3201/eid1503.081131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langridge GC, Fookes M, Connor TR, et al. : Patterns of genome evolution that have accompanied host adaptation in Salmonella. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(3):863–868. 10.1073/pnas.1416707112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bouquin S, Bonifait L, Thepault A, et al. : Epidemiological and bacteriological investigations using whole-genome sequencing in a recurrent outbreak of Pullorum disease on a quail farm in France. Animals (Basel). 2020;11(1):29. 10.3390/ani11010029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstedt BA, Torpdahl M, Nielsen EM, et al. : Harmonization of the multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis method between Denmark and Norway for typing Salmonella Typhimurium isolates and closer examination of the VNTR loci. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;102(3):728–735. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03134.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loman NJ, Constantinidou C, Chan JZ, et al. : High-throughput bacterial genome sequencing: an embarrassment of choice, a world of opportunity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10(9):599–606. 10.1038/nrmicro2850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, Payne M, Kaur S, et al. : Elucidation of global and local epidemiology of Salmonella Enteritidis through multilevel genome typing. BioRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.06.30.169953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiden MC, Bygraves JA, Feil E, et al. : Multilocus sequence typing: A portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(6):3140–3145. 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majowicz SE, Musto J, Scallan E, et al. : The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(6):882–889. 10.1086/650733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannas H, Mimouni R, Chaouqy N, et al. : Occurrence of Vibrio. and Salmonella species in mussels ( Mytilus galloprovincialis) collected along the Moroccan Atlantic coast. Springerplus. 2014;3:265. 10.1186/2193-1801-3-265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Urtaza J, Saco M, de NJ, et al. : Influence of environmental factors and human activity on the presence of Salmonella serovars in a marine environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(4):2089–2097. 10.1128/aem.70.4.2089-2097.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matiasovicova J, Adams P, Barrow PA, et al. : Identification of putative ancestors of the multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 clone harboring the Salmonella genomic island 1. Arch Microbiol. 2007;187(5):415–424. 10.1007/s00203-006-0205-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinersmann RJ, Berrang ME, Jackson CR, et al. : Salmonella, Campylobacter and Enterococcus spp.: Their antimicrobial resistance profiles and their spatial relationships in a synoptic study of the Upper Oconee River basin. Microb Ecol. 2008;55(3):444–452. 10.1007/s00248-007-9290-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methner U, Heller M, Bocklisch H: Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Choleraesuis in a wild boar population in Germany. Eur J Wildl Res. 2009;56:493–502. 10.1007/s10344-009-0339-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee N, Nolan VG, Dunn JR, et al. : Sources of human infection by Salmonella enterica serotype Javiana: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222108. 10.1371/journal.pone.0222108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadon C, Van Walle I, Gerner-Smidt P, et al. : PulseNet International: Vision for the implementation of whole genome sequencing (WGS) for global food-borne disease surveillance. Euro Surveill. 2017;22(23):30544. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.23.30544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Farrell B, Haase JK, Velayudhan V, et al. : Transforming microbial genotyping: A robotic pipeline for genotyping bacterial strains. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e48022. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons SK, Bull CM, Gordon DM: Substructure within Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica isolated from Australian wildlife. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(9):3151–3153. 10.1128/AEM.02764-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Sepulveda BM, Heavens D, Pulford CV, et al. : An accessible, efficient and global approach for the large-scale sequencing of bacterial genomes. BioRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.07.22.200840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron GG, Quessy S, Bell G: A reservoir of drug-resistant pathogenic bacteria in asymptomatic hosts. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3749. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porwollik S, Boyd EF, Choy C, et al. : Characterization of Salmonella enterica subspecies I genovars by use of microarrays. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(17):5883–5898. 10.1128/JB.186.17.5883-5898.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulford CV, Wenner N, Redway ML, et al. : The diversity, evolution and ecology of Salmonella in venomous snakes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(6):e0007169. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail MA, Smith M, Jackson D, et al. : SASI-Seq: sample assurance Spike-Ins, and highly differentiating 384 barcoding for Illumina sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(1):110. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J, Yoshida C, Kruczkiewicz P, et al. : Comprehensive assessment of the quality of Salmonella whole genome sequence data available in public sequence databases using the Salmonella in silico Typing Resource (SISTR). Microb Genom. 2018;4(2):e000151. 10.1099/mgen.0.000151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schikora A, Garcia AV, Hirt H: Plants as alternative hosts for Salmonella. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17(5):245–249. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia MD, Tennant SM, Bornstein K, et al. : Invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella infections among children in Mali, 2002-2014: Microbiological and epidemiologic features guide vaccine development. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):S332–S338. 10.1093/cid/civ729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timme RE, Sanchez LM, Allard MW: Utilizing the public GenomeTrakr database for foodborne pathogen traceback. In Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens(ed. A. Bridier), Humana, New York.2019;201–212. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9000-9_17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uesbeck A: Isolierung und Typisierung von Salmonellen aus Trinkwasserquellen in Benin, Westafrika. Cologne, University of Cologne.2009;1–153. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Waldram A, Dolan G, Ashton PM, et al. : Epidemiological analysis of Salmonella clusters identified by whole genome sequencing, England and Wales 2014. Food Microbiol. 2018;71:39–45. 10.1016/j.fm.2017.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters SP, Gonzalez-Escalona N, Son I, et al. : Salmonella enterica diversity in Central Californian coastal waterways. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(14):4199–4209. 10.1128/AEM.00930-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters SP, Thebo AL, Boehm AB: Impact of urbanization and agriculture on the occurrence of bacterial pathogens and stx genes in coastal waterbodies of central California. Water Res. 2011;45(4):1752–1762. 10.1016/j.watres.2010.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward LR, de Sa JD, Rowe B: A phage-typing scheme for Salmonella enteritidis. Epidemiol Infect. 1987;99(2):291–294. 10.1017/s0950268800067765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler TJ: Large-scale neighbor-joining with NINJA. Salzberg, S. L. and Warnow, T. Algorithms in Bioinformatics.Berlin, Heidelberg, Springer Berlin Heidelberg.2009;375–389. 10.1007/978-3-642-04241-6_31 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner M, Zaidi MB, Calva E, et al. : Association of virulence plasmid and antibiotic resistance determinants with chromosomal multilocus genotypes in Mexican Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:131. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong VK, Baker S, Connor TR, et al. : An extended genotyping framework for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, the cause of human typhoid. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12827. 10.1038/ncomms12827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong VK, Baker S, Pickard DJ, et al. : Phylogeographical analysis of the dominant multidrug-resistant H58 clade of Salmonella Typhi identifies inter- and intracontinental transmission events. Nature Genet. 2015;47(6):632–639. 10.1038/ng.3281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Fact Sheets: Salmonella (non-typhoidal). WHO Website.WHO. 2018. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Den-Bakker HC, Li S, et al. : SeqSero2: rapid and improved Salmonella serotype determination using whole genome sequencing data. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2019;85(23):e01746–19. 10.1128/AEM.01746-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Alikhan NF, Mohamed K, et al. : The EnteroBase user's guide, with case studies on Salmonella transmissions, Yersinia pestis phylogeny, and Escherichia core genomic diversity. Genome Res. 2020a;30(1):138–152. 10.1101/gr.251678.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Alikhan NF, Sergeant MJ, et al. : GrapeTree: Visualization of core genomic relationships among 100,000 bacterial pathogens. Genome Res. 2018a;28(9):1395–1404. 10.1101/gr.232397.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Charlesworth J, Achtman M: HierCC: A multi-level clustering scheme for population assignments based on core genome MLST. BioRxiv. 2020b. 10.1101/2020.11.25.397539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Lundstrøm I, Tran-Dien A, et al. : Pan-genome analysis of ancient and modern Salmonella enterica demonstrates genomic stability of the invasive Para C Lineage for millennia. Curr Biol. 2018b;28(15):2420–2428.e10. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, McCann A, Weill FX, et al. : Transient Darwinian selection in Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi A during 450 years of global spread of enteric fever. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(33):12199–12204. 10.1073/pnas.1411012111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]