Abstract

The goal of periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is to reorient the acetabulum in a more physiological position. Its realization remains challenging regarding the final position of the acetabulum. Assistance with custom cutting- and reorientation-guides would thus be very helpful. Our purpose is to present a pilot study on such guides. Eight cadaveric hemipelvis were scanned using CT. After segmentation, 3D models of each specimen were created, a PAO was virtually performed and reorientation of the acetabula were defined. A specific guide was designed aiming to assist in iliac, posterior column and superior pubic ramus cuts as well as in acetabulum reorientation. Furthermore, the acetabular position was planned. Three-dimensional printed guides were used to perform PAO using the modified Smith-Peterson approach. The post-operative CT images and virtually planned acetabulum reorientation were compared in terms of acetabular index (AC), lateral centre edge angle (LCE), acetabular anteversion angle (AcetAV). There was no intra-articular or posterior column fracture seen. Two cadavers showed very low bone quality with insufficient stability of fixation and were excluded from further analysis. Correlation between the post-operative result and planning of the six included cadavers revealed the following mean deviations: 5° (SD ±3°) for AC angle, 6° (SD ±4°) for LCE angle and 15° (SD ±11°) for AcetAV angle. The use of 3D cutting and reorientation blocks for PAO was possible through a modified Smith-Peterson approach and revealed accurate fit to bone, accurate positioning of the osteotomies and acceptable planned corrections in cadavers with good bone quality.

INTRODUCTION

Periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is a well-established procedure for the treatment of skeletally mature hip dysplasia [1] as well as femoroacetabular impingement due to true acetabular retroversion. The goal of PAO is to reorient the acetabulum in a more physiologic position [2]. Obtaining this ideal acetabular correction is challenging [3] because the final position of the acetabular fragment must lie within a narrow 3D range. Furthermore, the osteotomy planes must keep the pelvic ring intact while remaining extra-articular [4, 5].

Traditional PAO techniques have utilized intra-operative fluoroscopy in order to verify the accuracy and location of osteotomy cuts. Fluoroscopy was one feature to try to perform a more accurate and safe correction in PAO surgery. However, fluoroscopy still is limited by delivering 2D information for the surgeon and therefore it is also only possible to be as accurate as the 2D planning preoperatively. Prior work has been done to study other techniques to improve acetabular reorientation with the help of computer navigation [6]. This technique may be limited by additional operating room equipment, modified surgical exposures and additional surgical time.

Patient specific cutting- and reorientation-guides may be a useful adjunctive intra-operative tool to reduce intra-operative fluoroscopy use, to reduce operative time, and to increase the accuracy of the 3D pelvic osteotomy. In particular, this new technology might be able to optimize load distribution without compromising on hip range of motion. In order to plan an individually adapted PAO the CT planning is mandatory and to execute this 3D plan the patient specific guide could be a valuable possibility.

While custom guides and individualized templates have been employed in other types of orthopaedic procedures [7, 8] and other pelvic osteotomies [9–11], the application in PAO as characterized by Ganz has been presented only once by Zhou et al. [12]. However, Zhou et al. did not perform the PAO surgery as described by Ganz et al. [13] through a modified Smith-Peterson approach, but on bony cadaver after extensive soft tissue stripping.

The purpose of this report is to present the results of a cadaveric pilot study using CT-based custom-made guides for PAO on the one hand focusing on the precise cuts respecting the anatomy and the approach and on the other hand on the reorientation. Therefore the feasibility and accuracy of these 3D guides were particularly important to the authors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eight Thiel-fixed cadaveric (six females, two males) specimen, with a mean age of 85 years (range 56–100), were obtained and utilized according to the institutional guidelines and with informed consent of the donors prior to death or appropriate family members. The local institutional review board waived the need for ethical approval (BASEC-Nr. Req-2016-00517).

Preparation and planning

The cadaver hemipelves were scanned using a high-resolution computer tomographic scanner (Siemens CT) with voxel size of 0.65 × 0.65 × 1.25 mm. After segmentation of the images using Mimics® software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium), editable 3D models of each specimen were created.

A virtual PAO was performed using the partial ischial cut, the pubic cut, the iliac cut and then the completion in the ischium preserving the posterior column on the 3D models (in silico) (Fig. 1a and b) and reorientation of the acetabulum was defined arbitrary to a higher lateral centre edge angles (LCE) and a reasonable anteversion. Using 3-matic® software, an anatomy-specific guide was designed for assisting in the cadaveric supracetabular (Figs 2–6), posterior column and superior pubic ramus cuts. The partial ischial cut was not guided because of the lack of access during the real procedure.

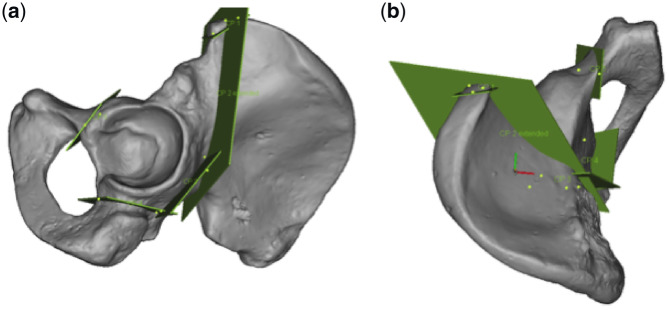

Fig. 1.

In these figures, all four cuts of the PAO not involving the posterior column are shown in this 3D model of a left hemipelvis. (a) Lateral view is seen and (b) a top view is shown.

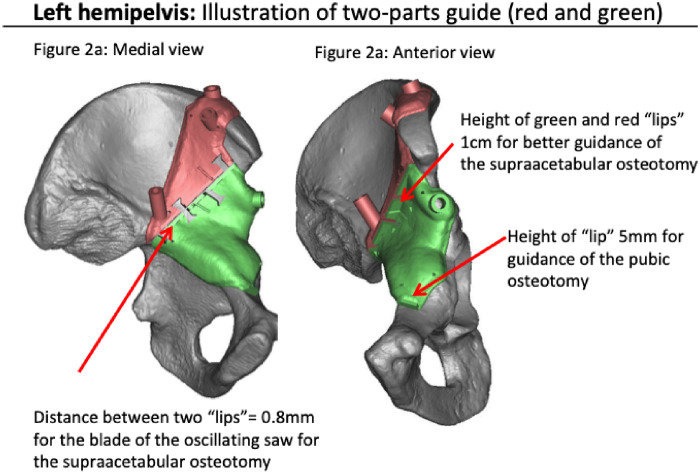

Fig. 2.

Virtual 3D shaped guides fitting (red and green) on bone surface, showing the guided cut for the iliac bone. (a) Left hemipelvis from a medial view and (b) from an anterior view. The guides are broad but not bulky.

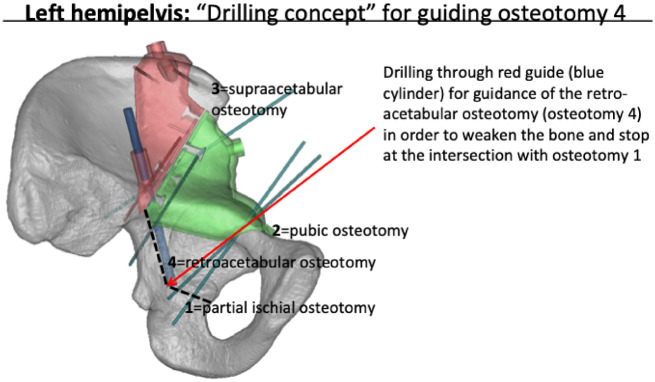

Fig. 3.

This blue fixation guide (named bridge) was used to verify the optimal fit between the two guides (red and green).

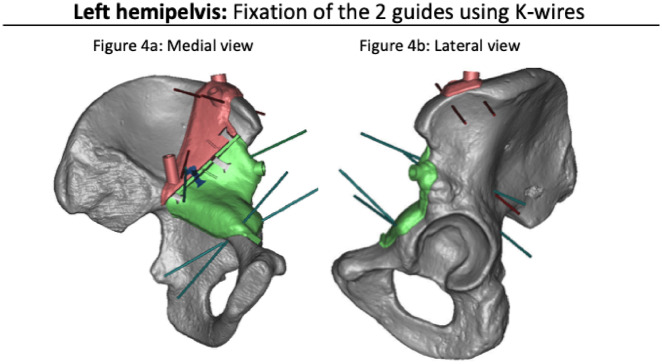

Fig. 4.

These figures show a medial view (a) and a lateral view (b) of a left hemipelvis in the phase of fixing the guides with K-wires.

Fig. 5.

The blue cylinder is showing the retroacetabular guidance. The retroacetabular osteotomy was not guided for a chisel. The angulation and the distance was planned and drilled as far as needed to meet the partial ischial osteotomy, which was the first osteotomy performed.

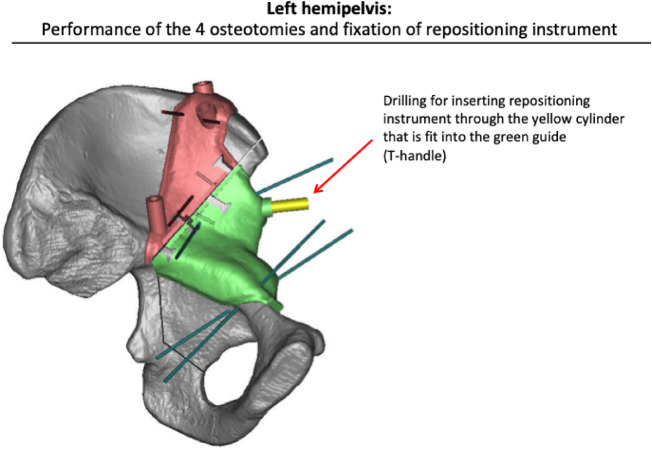

Fig. 6.

After completing all the osteotomies the Schantz screw was inserted (here depicted as a yellow cylinder).

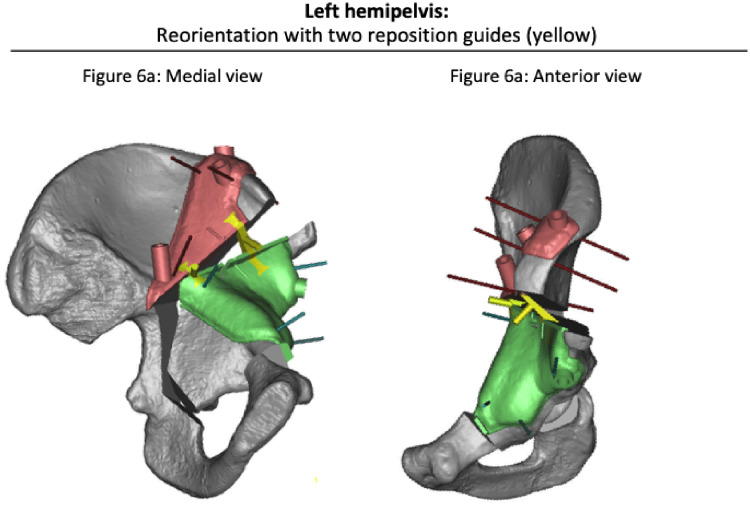

Furthermore, the reorientation-guides were planned to achieve the intended acetabular reorientation. Position, length and trajectory of the fixation screws were calculated. All the guides (cutting- and reorientation guides) were individually manufactured for performing PAO on the respective cadaveric specimen. One example of a reposition guide is shown in Fig. 7a and b.

Fig. 7.

Reorientation of acetabular fragment as defined by reorientation guides (yellow) according to virtually planned correction (3matic® software). (a) Medial view of a left hemipelvis and (b) an anterior view.

Surgical procedure

PAO according to Ganz et al. [13] through the modified Smith-Peterson approach was performed using original instruments by two fellowship trained hip surgeons.

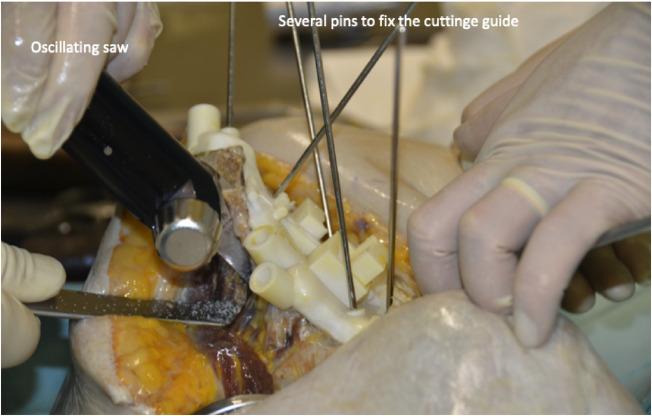

The cadaver hemipelves were in supine position and a modified Smith-Peterson approach was used with an osteotomy of the anterior iliac spine. In the interval of sartorius and tensor fascie latae (superficial layer) and rectus femoris and hip abductors (deep layer) the joint capsule was exposed and with a curved special PAO chisel the first partial ischial osteotomy was performed. Further the pubic cut was performed after correct placement of the cutting guide and then the iliac cut (Fig. 8) was done with an oscillating saw after correct placement of the guide. To complete the partial ischial cut a straight chisel was used along the last cutting guide until the acetabulum became free. With a supra-acetabular Schanz screw the acetabulum was oriented in a preliminary position with more lateral coverage. Furthermore, the reorientation guide was placed (Fig. 9) to achieve the most accurate and particularly the planned acetabular orientation. A preliminary fixation with pins was done and the planned three screws were placed accordingly. The complete surgical plan is depicted in Figs 2–6 and intra-operatively executed in this exact way.

Fig. 8.

The two cutting guides fit perfectly on the bone and were fixed with pins. The surgeon performs the iliac cut of this right cadaver hemipelvis. A lateral retractor is protecting the hip abductor muscles.

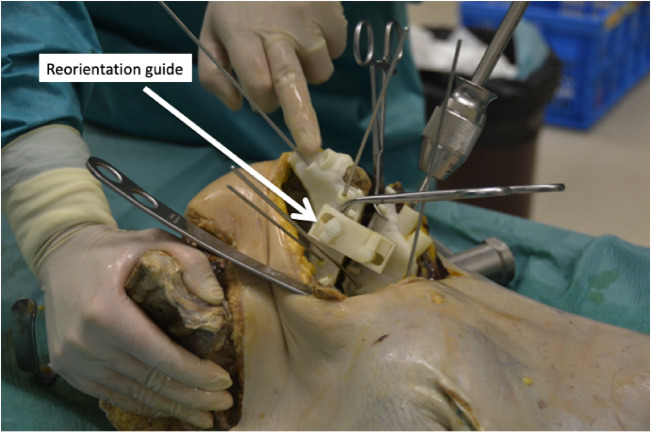

Fig. 9.

In this left cadaver hemipelvis the Schantz screw with handle is seen and the reorientation guide is placed to hold the acetabulum in the planned place before fixing with pins and then screws.

Bone quality

All eight specimens were classified arbitrary in ‘good’, ‘moderate’ and ‘poor’ bone quality.

Post-surgical imaging

Computer tomographic images were acquired postoperatively. This needed a transportation of the cadavers in another building.

Measurements

Pre- and post-operative measurements were obtained from the CT scans of the following parameters: (i) LCE [14]; (ii) acetabular index (AC) [15] and (iii) acetabular anteversion (AcetAV) angles [16, 17]. These parameters were measured from a 3D segmented model in frontal, sagittal and transverse planes.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics v24.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics, one-way univariate analysis of variance and a paired Student t test, was used to compare preoperative planned and postoperative LCE angles, AC angles, AcetAV angles and position of the centre of rotation. Statistical significance was considered when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Bone quality was poor in four, moderate in two and good in two specimens. Application of the guides through the standard modified Smith-Peterson approach and performance of the osteotomies, reorientation and fixation was challenging in four out of the eight cadavers because of the osteoporotic very soft bone. In two cadavers, the Schanz screws were even pulled out and could not be used for repositioning and reorientation, which made the operation impossible and these two cases were excluded from further analysis. However, the postoperative analyses showed that the cutting planes were completely extra-articular and the posterior column intact in all eight specimens.

The mean difference between the post-operative measured result and the planned preoperative calculated correction were as follows: 6° (SD ±4°) for LCE angle, 5° (SD ±3°) for AC angle and 15° (SD ±11°) for AcetAV angle. Outliers, defined as more than 10° difference, were only seen in cadavers with moderate and poor bone quality.

The detailed information about every cadaver is depicted in Table I.

Table I.

Overview of the results of all the six cadavers

| Cadaver | Bone quality | LCE (°) | AC (°) | AcetAV (°) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Preop | Good | 30 | −13 | 20 |

| Planned | 43 | −1 | 28 | ||

| Postop | 42 | −2 | 22 | ||

| Diff(planned-postop) | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Planned correction | 13 | 12 | 8 | ||

| Obtained correction | 12 | 12 | 2 | ||

| 2 | Preop | Poor | 31 | −10 | 24 |

| Planned | 47 | 3 | 37 | ||

| Postop | 36 | −5 | 12 | ||

| Diff(planned-postop) | 11 | 8 | 26 | ||

| Planned correction | 16 | 13 | 14 | ||

| Obtained correction | 5 | 5 | 12 | ||

| 3 | Preop | Moderate | 45 | −2 | 21 |

| Planned | 61 | 11 | 32 | ||

| Postop | 54 | 4 | 26 | ||

| Diff(planned-postop) | 7 | 7 | 5 | ||

| Planned correction | 16 | 13 | 11 | ||

| Obtained correction | 9 | 6 | 6 | ||

| 4 | Preop | Good | 43 | −7 | 23 |

| Planned | 58 | 6 | 32 | ||

| Postop | 54 | 0 | 26 | ||

| Diff(planned-postop) | 4 | 6 | 6 | ||

| Planned correction | 15 | 14 | 9 | ||

| Obtained correction | 11 | 7 | 3 | ||

| 5 | Preop | Moderate | 42 | −3 | 13 |

| Planned | 55 | 9 | 24 | ||

| Postop | 53 | 8 | 7 | ||

| Diff(planned-postop) | 2 | 1 | 17 | ||

| Planned correction | 13 | 12 | 11 | ||

| Obtained correction | 11 | 11 | 6 | ||

| 6 | Preop | Poor | 32 | −38 | −12 |

| Planned | 47 | −23 | −19 | ||

| Postop | 38 | −31 | 11 | ||

| Diff(planned-postop) | 10 | 8 | 30 | ||

| Planned correction | 16 | 14 | 7 | ||

| Obtained correction | 6 | 7 | 24 | ||

| Mean 1–6 | Diff(planned-postop) | 6 | 5 | 15 |

A complete overview of the results regarding preoperative, planned and postoperative measured correction in the CT scans.

LCE, lateral centre edge angle; AC, acetabular index; AcetAV, acetabular anteversion angles; COR, centre of rotation; Diff(planned-postop), difference (planned-postoperative).

DISCUSSION

PAO allows for powerful correction of abnormal acetabular morphology. The goal of this correction is to enhance the function and preserve the durability of the native hip joint. While the technique of PAO has been well-described since its inception [13], it remains a technically demanding procedure, with significant risks of complications [4, 5] and an initial learning curve [3]. To aid with osteotomy accuracy and reliability, a number of adjunctive surgical tools have been used including navigation and computer guidance. This study presents the initial experience with patient-specific cutting guides in PAO, with the purpose of understanding the potential intra-operative feasibility issues and accuracy associated with use of these 3D, image-based guides.

Custom made cutting and/or reposition guides have been used in a number of other surgical fields, including upper extremity [18–21], maxillofacial [22, 23], microvascular [24], knee [25, 26] and veterinary [27] procedures. Likewise, a number of procedures about the hip, including total hip arthroplasty [28, 29], hip resurfacing [30–32], pelvic oncology [33, 34] and femoral deformity correction [35], have benefitted from computer assistance. While custom made guides have been employed in certain pelvic osteotomies [9–11], we found only one work of a Chinese group applying custom made 3D guides for PAO [12]. Although, in this study was stated the surgery was performed according to Ganz et al., the four osteotomies were performed with the oscillating saw, which is contradictory to the surgical technique described by Ganz. In particular, the partial ischial osteotomy is not possible to perform without an extensive soft tissue stripping.

The question regarding feasibility performing a PAO with cutting and repositioning guides can be answered with yes, but only in cadavers with good bone quality. The standard modified Smith-Peterson approach without extension of the skin incision or surgical dissection was used in all cases. No separate surgical incisions were needed, as in the case of certain navigation systems or systems in which supplemental pins are required. The guides had an accurate and reproducible fit to the host bone. Importantly, the guides offered reliable positioning and execution of the planned osteotomies, with accurate approximation of the virtual osteotomy planes. However, the main technical challenge was the very soft bone in these old cadavers, which was the reason to exclude two cases and in two other cases the difference between the planned and performed LCE was more than expected with 11° and 10°, respectively, and in the AcetAV with 26° and 30°, respectively. In the other four cases, the difference from planned to perform LCE was 1°, 2°, 4° and 6° and AcetAV was 5°, 5°, 6° and 17°. Of course a difference of 17° in the AcetAV is not acceptable and can only be explained by the soft bone which was impressed while positioning reorientation guide or even more likely there was a loss of the position during the transport in the other institution to perform the CT-scan especially in the four specimen classified as moderate and poor bone quality. A limitation is that there were no quantifying measurements of the bone quality and the surgeon only made the bone quality classification poor, moderate or good arbitrary after performing the PAO.

However, most likely this challenge would not be faced in vivo since the patient group requiring PAO is young and usually has very good bone quality. Certainly, further in vivo studies would have to confirm the hypotheses that in the young patients with good bone quality the precision would be better.

In the 30 years follow-up study of the Bernese group [36] an inaccurate post-operative acetabular position was a risk factor for earlier osteoarthritis. Therefore, the here shown guided technique to get the optimal postoperative position of the acetabulum might be a reasonable method in doing so.

Further limitations of this new technology include the cost and time associated with the design and manufacturing of the osteotomy guides. There is time also spent by the surgeon to perform the virtual osteotomy and correction, which can be a challenge for a non-experienced PAO surgeon were exactly to place the correct cuts and to which extent the correction should be performed. To which extent the correction should be performed is still debated and especially is not known for the 3D orientation measured on a CT-scan.

This technology at present relies on the use of a pre-operative CT for manufacturing. Finally, while osteotomy guides should not substitute for adequate training in this complex procedure, further studies should examine whether this technology offers added benefit to the experienced PAO surgeon, or have a preferential role for those in a learning period.

Cutting- and reorientation guides aimed to assist the iliac, posterior column and superior pubic ramus cuts as well as acetabular reorientation. However, the partial ischial cut seems not to be possible to guide when respecting the true anatomy. Especially for the less experienced PAO surgeon this usually first performed partial ischial osteotomy is the most challenging and also the most dangerous one not to insure the sciatic nerve since it is performed blind. Further studies are needed to find a way to guide this osteotomy as well to make this procedure less susceptible for complications for our patients. While we did not experience guide breakage, malfunction or poor mating of the guides with the bony anatomy, these remain theoretical concerns.

Moreover, the guides may obviate the need for approximation of pre-operative images as is required when fluoroscopy is used to compare pre-operative and intra-operative projections. Deviations that may exist between pre-operative weight-bearing radiographs may be mitigated by the patient-specific guides, and minimizes the operator-dependency associated with intra-operative fluoroscopic imaging. A further additional limitation of this initial pilot study includes the relatively small sample size.

This is the first study that demonstrates that a patient-specific virtual PAO could be translated to the cadaveric setting using the true technique of the PAO respecting anatomy and approach as it has been described. The use of 3D cutting and reorientation blocks for PAO was possible through a standard Smith-Peterson approach without extension and revealed accurate fit to bone, accurate positioning of the osteotomies and acceptable planned corrections in cadavers with good bone quality. This new technology may have in vivo applications that will allow the orthopaedic surgeon to perform safe and accurate osteotomies, reorient the acetabulum exactly as individually, preoperatively planned and therefore optimize load distribution without compromising on range of motion. However, this guidance should not substitute for excellent anatomic knowledge and a fellowship in reconstructive hip surgery to gain experience in PAO surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Elke Giets for his help with this study.

FUNDING

This study was supported by our own institutional research fund.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

C.D. is co-owner of a patent on surgical guides (Patent PCT/EP2012/059168).

REFERENCES

- 1. Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS, Mast JW.. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias. Technique and preliminary results. 1988. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leunig M, Siebenrock KA, Ganz R.. Rationale of periacetabular osteotomy and background work. Instr Course Lect 2001; 50: 229–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peters CL, Erickson JA, Hines JL.. Early results of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy: the learning curve at an academic medical center. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88: 1920–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biedermann R, Donnan L, Gabriel A. et al. Complications and patient satisfaction after periacetabular pelvic osteotomy. Int Orthop 2008; 32: 611–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davey JP, Santore RF.. Complications of periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999: 33–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Langlotz F, Stucki M, Bächler R. et al. The first twelve cases of computer assisted periacetabular osteotomy. Comput Aided Surg 1997; 2: 317–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Radermacher K, Portheine F, Anton M. et al. Computer assisted orthopaedic surgery with image based individual templates. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998; 354: 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wong KC, Kumta SM, Leung KS. et al. Integration of CAD/CAM planning into computer assisted orthopaedic surgery. Comput Aided Surg 2010; 15: 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Akiyama H, Goto K, So K, Nakamura T.. Computed tomography-based navigation for curved periacetabular osteotomy. J Orthop Sci 2010; 15: 829–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jäger M, Westhoff B, Wild A. et al. Computer-assisted periacetabular triple osteotomy for treatment of dysplasia of the hip. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 2004; 142: 51–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Otsuki B, Takemoto M, Kawanabe K. et al. Developing a novel custom cutting guide for curved peri-acetabular osteotomy. Int Orthopaedics (SICOT) 2013; 37: 1033–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou Y, Kang X, Li C. et al. Application of a 3-dimensional printed navigation template in Bernese periacetabular osteotomies: a cadaveric study. Medicine 2016; 95: e5557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS. et al. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias: technique and preliminary results. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988; (232): 26–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wiberg G. Studies on dysplastic acetabula and congenital subluxation of the hip joint with special reference to the complication of osteoarthritis. Acta Chir Scand1939; 83(suppl 58): 7–135. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murphy SB, Ganz R, Müller ME.. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77: 985–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anda S, Terjesen T, Kvistad KA. et al. Acetabular angles and femoral anteversion in dysplastic hips in adults: CT investigation. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1991; 15: 115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Anda S, Terjesen T, Kvistad KA.. Computed tomography measurements of the acetabulum in adult dysplastic hips: which level is appropriate? Skeletal Radiol 1991; 20: 267–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kunz M, Ma B, Rudan JF. et al. Image-guided distal radius osteotomy using patient-specific instrument guides. J Hand Surg 2013; 38: 1618–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oka K, Murase T, Moritomo H. et al. Corrective osteotomy for malunited both bones fractures of the forearm with radial head dislocations using a custom-made surgical guide: two case reports. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012; 21: e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Suero EM, Citak M, Lo D. et al. Use of a custom alignment guide to improve glenoid component position in total shoulder arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21: 2860–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tricot M, Duy KT, Docquier P-L.. 3D-corrective osteotomy using surgical guides for posttraumatic distal humeral deformity. Acta Orthop Belg 2012; 78: 538–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abou-ElFetouh A, Barakat A, Abdel-Ghany K.. Computer-guided rapid-prototyped templates for segmental mandibular osteotomies: a preliminary report. Int J Med Robot 2011; 7: 187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Philippe B. Custom-made prefabricated titanium miniplates in Le Fort I osteotomies: principles, procedure and clinical insights. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013; 42: 1001–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ciocca L, Mazzoni S, Fantini M. et al. A CAD/CAM-prototyped anatomical condylar prosthesis connected to a custom-made bone plate to support a fibula free flap. Med Biol Eng Comput 2012; 50: 743–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kunz M, Waldman SD, Rudan JF. et al. Computer-assisted mosaic arthroplasty using patient-specific instrument guides. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012; 20: 857–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lachiewicz PF, Henderson RA.. Patient-specific instruments for total knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2013; 21: 513–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marcellin-Little DJ, Harrysson OLA, Cansizoglu O.. In vitro evaluation of a custom cutting jig and custom plate for canine tibial plateau leveling. Am J Vet Res 2008; 69: 961–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hananouchi T, Saito M, Koyama T. et al. Tailor-made surgical guide reduces incidence of outliers of cup placement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468: 1088–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zheng G, Marx A, Langlotz U. et al. A hybrid CT-free navigation system for total hip arthroplasty. Comput Aided Surg 2002; 7: 129–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Audenaert E, De Smedt K, Gelaude F. et al. A custom-made guide for femoral component positioning in hip resurfacing arthroplasty: development and validation study. Comput Aided Surg 2011; 16: 304–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Olsen M, Naudie DD, Edwards MR. et al. Evaluation of a patient specific femoral alignment guide for hip resurfacing. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29: 590–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Raaijmaakers M, Gelaude F, De Smedt K. et al. A custom-made guide-wire positioning device for hip surface replacement arthroplasty: description and first results. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010; 11: 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma L, Zhou Y, Zhu Y. et al. 3D-printed guiding templates for improved osteosarcoma resection. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 23335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cartiaux O, Banse X, Paul L. et al. Computer-assisted planning and navigation improves cutting accuracy during simulated bone tumor surgery of the pelvis. Comput Aided Surg 2013; 18: 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chai W, Xu M, Zhang G-Q. et al. Computer-aided design and custom-made guide in corrective osteotomy for complex femoral deformity. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci 2013; 33: 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lerch TD, Steppacher SD, Liechti EF. et al. One-third of hips after periacetabular osteotomy survive 30 years with good clinical results, no progression of arthritis, or conversion to THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017; 475: 1154–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]