Abstract

Many ethnic minorities in the United States consider themselves to be just as American as their European American counterparts. However, there is a persistent cultural stereotype of ethnic minorities as foreigners (i.e., the perpetual foreigner stereotype) that may be expressed during interpersonal interactions (i.e., foreigner objectification). The goal of the present study was to validate the Foreigner Objectification Scale, a brief self-report measure of perceived foreigner objectification, and to examine the psychological correlates of perceived foreigner objectification. Results indicated that the Foreigner Objectification Scale is structurally (i.e., factor structure) and metrically (i.e., factor loadings) invariant across foreign-born and U.S.-born Asian Americans and Latinos. Scalar (i.e., latent item intercepts) invariance was demonstrated for the two foreign-born groups and the two U.S.-born groups, but not across foreign-born and U.S.-born individuals. Multiple-group structural equation models indicated that, among U.S.-born individuals, perceived foreigner objectification was associated with less life satisfaction and more depressive symptoms, and was indirectly associated with lower self-esteem via identity denial, operationalized as the perception that one is not viewed by others as American. Among foreign-born individuals, perceived foreigner objectification was not significantly associated directly with self-esteem, life satisfaction, or depressive symptoms. However, perceived foreigner objectification was positively associated with identity denial, and identity denial was negatively associated with life satisfaction. This study illustrates the relevance of perceived foreigner objectification to the psychological well-being of U.S.-born Asian Americans and Latinos.

Keywords: perpetual foreigner, objectification, perceived discrimination

“Where are you from?” This is a common question that most people have asked and have been asked upon meeting someone for the first time. On face value, the question seems rather innocuous. However, it may pose a threat to one’s personal identity if it calls into question membership in a group to which one belongs (Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987). Such threats appear to be commonly experienced by many ethnic minorities in the United States, who may view themselves to be just as American as their European American counterparts, but also may be aware that they are viewed as less American than are European Americans (Barlow, Taylor, & Lambert, 2000; Cheryan & Monin, 2005; Devos & Banaji, 2005). In addition, there remains a persistent cultural stereotype that members of various ethnic minority groups are foreigners (Devos & Ma, 2008; Rivera, Forquer, & Rangel, 2010; Sue et al., 2007; Wong, Owen, Tran, Collins, & Higgins, 2012) and being American is often equated to being White (Cheryan & Monin, 2005; Devos & Banaji, 2005). In this article, we refer to the belief that ethnic minorities in the United States are foreigners as the perpetual foreigner stereotype (Tuan, 1998), the application of this stereotype as foreigner objectification, and the perception that one has been targeted by foreigner objectification as perceived foreigner objectification.1 Because it involves the application of an ethnic stereotype (Fiske, 1998), foreigner objectification represents a form of ethnic discrimination (Sue et al., 2007), albeit a more subtle form than has typically been discussed within the discrimination literature.

Extant research on foreigner objectification suggests that perceived foreigner objectification is associated with negative psychosocial outcomes among Asian Americans and Latinos (Guendelman, Cheryan, & Monin, 2011; Huynh, Devos, & Smalarz, 2011; Kim, Wang, Deng, Alvarez, & Li, 2011). The present study extends this research in three important ways. First, we validate the Foreigner Objectification Scale (Pituc, Jung, & Lee, 2009), a brief self-report measure of perceived foreigner objectification. Second, we examine the associations between perceived foreigner objectification and psychological well-being. Finally, we test whether this association is mediated by identity denial, operationalized as the belief that one is not viewed as American. In all of our analyses, we consider ethnicity (i.e., Asian Americans and Latinos) and nativity status (i.e., foreign-born and U.S.-born) as potential moderators.

Foreigner Objectification and Psychological Well-Being

Research on the psychological consequences of perceived discrimination (i.e., being treated unfairly because of one’s group membership) has steadily increased over the past few decades. This work has demonstrated that perceiving discrimination has negative psychological consequences, such as lower self-esteem (e.g., Armenta & Hunt, 2009), greater stress (see Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009), more depressive symptoms (e.g., R. M. Lee, 2005), and higher rates of psychopathology (see Gee, Spencer, Chen, Yip, & Takeuchi, 2007; D. L. Lee & Ahn, 2011; Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003). Unfortunately, scholars have focused most heavily on experiences of discrimination that result from others’ obviously negative attitudes toward one’s ethnic group. For example, many widely used measures of perceived ethnic discrimination include items that assess, among other things, the degree to which an individual has been avoided, rejected, denigrated, threatened, or assaulted on the basis of his or her ethnicity (e.g., Contrada et al., 2001; Landrine & Klonoff, 1996; Yoo, Steger, & Lee, 2010). Members of ethnic minority groups, however, may experience more subtle forms of discrimination based on the assumption that they are foreigners, regardless of their nativity (i.e., the perpetual foreigner stereotype). The perpetual foreigner stereotype often may be expressed inadvertently during social interactions, even by individuals who harbor no ill will toward an individual’s ethnic group (Devine, 1989; Dovidio & Gaertner, 2008; Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986). For example, an ethnic minority individual may be asked where he or she is from or may be complimented on how well he or she speaks English because it is (implicitly or explicitly) assumed that most (if not all) members of his or her ethnic group are foreigners (Sue et al., 2007).

Borrowing from the objectification literature, which has primarily focused on sexual objectification (e.g., Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Nussbaum, 1995), we refer to the application of the perpetual foreigner stereotype as foreigner objectification. According to Nussbaum (1995), objectification occurs when “one is treating as an object what is really not an object, what is, in fact, a human being” (p. 257). Nussbaum argued that objectification may be observed in a number of ways, including the denial of subjectivity where the “objectifier treats the object as something whose experience and feelings (if any) need not be taken into account” and the treatment of an “object as interchangeable with other objects of the same type” (p. 257). In this way, the application of a group stereotype represents one form of objectification. We elected to use the term objectification to reflect our belief that foreigner objectification is primarily the result of cognitive (i.e., stereotypes) rather than emotional (e.g., anger, hate) mechanisms, although emotional mechanisms (e.g., resulting from self-threat) may certainly motivate the application of the perpetual foreigner stereotype (Kunda & Spencer, 2003).

Although limited, existing evidence suggests that perceived foreigner objectification has negative psychosocial consequences. For example, Kim, Wang, et al. (2011) showed that being treated on the basis of the perpetual foreigner stereotype was positively associated with depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents. In addition, Huynh et al. (2011) showed that being aware of the perpetual foreigner stereotype was positively associated with depressive symptoms among Latinos and negatively associated with feelings of hope and life satisfaction among Asian Americans. Huynh et al. also found, however, that awareness of the perpetual foreigner stereotype was not significantly associated with feelings of hope or life satisfaction among Latinos, and was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms among Asian Americans.

Huynh et al. (2011) speculated that historical and/or cultural differences may explain the differential patterns between Latinos and Asian Americans in their study. However, given their relatively small sample size (Latinos, n = 165; Asian Americans, n = 56), we suspect that some of their nonsignificant associations were due to underpowered statistical tests. For example, with 56 participants, the statistical power to detect a correlation of .25 (the correlation reported for awareness of the perpetual foreigner stereotype and depressive symptoms among Asian Americans) is .47. Importantly, in the Huynh et al. study, the correlations between awareness of the perpetual foreigner stereotype and the psychological outcomes were in the predicted direction for both Asian Americans and Latinos. Nonetheless, we consider the potential role of ethnicity in the present article (see below).

Identity Denial as a Mediator

The social identity perspective (Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner et al., 1987; see also Hornsey, 2008; Spears, 2011; Turner, 1999) provides insight into one mechanism through which perceived foreigner objectification may affect psychological well-being. This perspective posits that the groups to which one belongs, even in minimal group situations in which group membership is randomly assigned (e.g., Tajfel, Billig, Bundy, & Flament, 1971), become incorporated into one’s self-concept and thus serve as a basis for self-definition and, consequently, personal self-evaluations. Of particular relevance to the present article, the social identity perspective further posits that experiences that invalidate one’s status as a group member can pose a threat to one’s personal identity, which Branscombe, Ellemers, Spears, and Doosje (1999) have referred to as an acceptance threat. Recently, Cheryan and Monin (2005) argued that the experience of having one’s identity questioned, such as when a member of an ethnic minority group is asked where he or she is from because it is assumed that he or she is a foreigner, represents a specific type of acceptance threat, which they refer to as identity denial. Importantly, several theoretical perspectives contend that humans have a fundamental need to view themselves (and their environment) in an accurate manner and that evidence to the contrary has negative psychological consequences (e.g., Erikson, 1968; Hogg, 2007; Swann, 1983; Tajfel, 1969). To the extent that foreigner objectification conveys the message that one is not American, then, identity denial should help to explain (i.e., mediate) the negative psychological effects of perceived foreigner objectification.

A similar rationale for this prediction may be derived from objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), which posits that individuals may experience negative emotions, particularly shame, if they consider themselves to be dissimilar to some internalized or cultural ideal of a group.2 As already noted, being American is often equated to being White (Cheryan & Monin, 2005; Devos & Banaji, 2005), suggesting that the cultural ideal of an American is an individual with characteristics that are similar to those of White Americans (e.g., light skin). Because foreigner objectification may communicate the message that one is not American, and because personal comparisons to the cultural ideal of an American are likely to come up short, then, foreigner objectification experiences should be associated with negative emotional outcomes. Although we did not assess specific emotions in the present study, negative emotions such as shame have been linked to negative psychological outcomes, including depression (e.g., Kim, Thibodeau, & Jorgensen, 2011; Orth, Berking, & Burkhardt, 2006).

Current Study

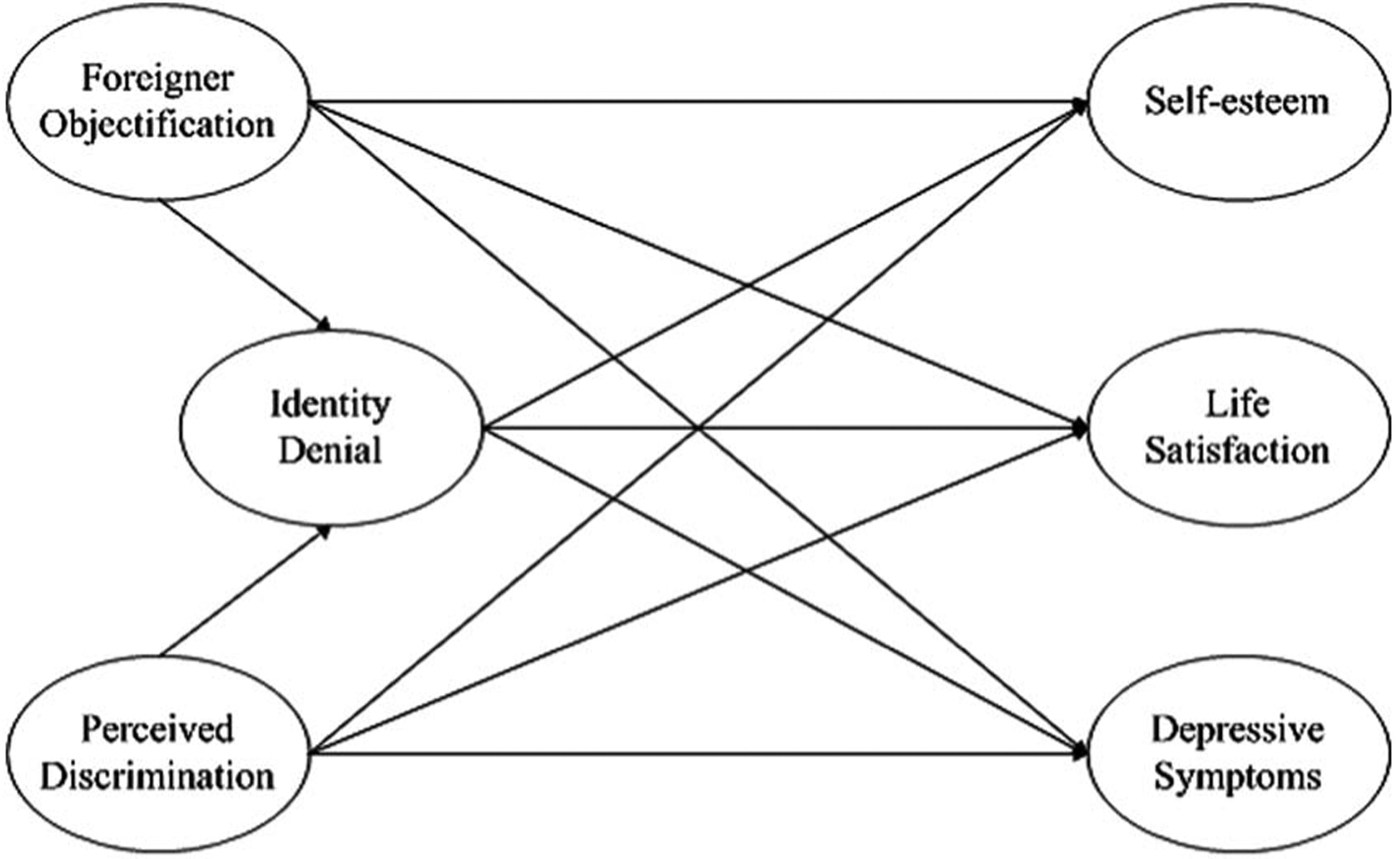

Given the burgeoning empirical interest in foreigner objectification (Huynh et al., 2011; Kim, Wang, et al., 2011), the primary goal of the present study was to validate the Foreigner Objectification Scale (Pituc et al., 2009), a brief measure of perceived foreigner objectification, among Asian Americans and Latinos. To this end, we examined the measurement properties of the Foreigner Objectification Scale and sought to provide evidence of convergent and divergent validity by examining the degree to which the Foreigner Objectification Scale correlated with theoretically related (e.g., general perceptions of discrimination) and ostensibly unrelated (e.g., emotion regulation) constructs. As a secondary goal, we tested substantive hypotheses regarding foreigner objectification and psychological well-being. Based on existing theory (Cheryan & Monin, 2005; Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner et al., 1987) and research (Huynh et al., 2011; Kim, Wang, et al., 2011), we examined the predictions that (a) greater perceived foreigner objectification would be associated with more negative psychological outcomes, even after controlling for perceptions of more general forms of discrimination; and (b) identity denial, operationalized in the present study as the belief that one is not viewed by others as American, would mediate the associations between perceived foreigner objectification and psychological well-being. To be comprehensive, we also examined identity denial as a potential mediator of the associations between perceptions of more general forms of discrimination and the psychological well-being variables. Our analytic model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual and analytic model.

As noted earlier, Huynh et al. (2010) argued that historical and/or cultural differences may have accounted for the differential correlates of exposure to the perpetual foreigner stereotype among Asian Americans and Latinos in their study. Although we suggested that their results might have been partially due to insufficient statistical power, consideration of ethnic group differences is warranted. Thus, we considered ethnicity as a moderator in our analyses. For two reasons, however, we did not expect any of our results to be moderated by ethnicity. First, throughout recent history, both Asian Americans and Latinos have been targeted by exclusionary treatment within the United States. For example, following Japan’s involvement in the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1942, individuals of Japanese descent were forced into internment, and during the Great Depression era of the 1930s, individuals of apparent Mexican descent were targeted for deportation. In both cases, targeted individuals were treated similarly regardless of nativity status and without due process of the law (for more examples, see Nagayama Hall & Barongan, 2002). Second, empirical evidence suggests that Asian Americans and Latinos are similarly viewed as being less American than are White Americans (Dovidio, Gluszek, John, Ditlmann, & Lagunes, 2010, preliminary study for Study 2; cf. Discussion section), and that Asian Americans and Latinos similarly perceive themselves as being viewed by others as foreigners (Torres-Harding, Andrade, & Romero Diaz, 2012).

There are reasons, however, to suspect differences between foreign-born and U.S.-born individuals, which we considered as an additional moderator in our analyses. First, foreign-born individuals are more likely than their U.S.-born counterparts to speak with an accent and behave in ways that reflect their heritage culture. Because of this, foreign-born individuals may not find foreigner objectification to be demeaning or threatening. Second, foreign-born individuals may view themselves as foreigners in the United States, and perhaps expect to have their citizenship status questioned from time to time. In a related vein, being American may not be a particularly self-defining characteristic for foreign-born individuals; thus, their personal self-views may not be contingent on their acceptance as an American. As such, we expected that foreigner objectification would be less strongly (or nonsignificantly) associated with psychological well-being among foreign-born individuals relative to their U.S.-born counterparts. We also expected that identity denial, operationalized as not being viewed by others as American, would be less strongly (or nonsignificantly) associated with psychological well-being among foreign-born individuals relative to U.S.-born individuals. Finally, to the extent that foreigner objectification is significantly associated with psychological well-being among foreign-born individuals, we did not expect identity denial to mediate this association.

Given our consideration of ethnicity and nativity, we also examined whether the Foreigner Objectification Scale similarly assesses the underlying construct of perceived foreigner objectification in foreign-born Asian Americans, U.S.-born Asian Americans, foreign-born Latinos, and U.S.-born Latinos. To this end, we conducted measurement invariance analyses (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000) to examine the structural (i.e., factor structure), metric (i.e., factor loadings), and scalar (i.e., latent item intercepts) equivalence across the groups.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data were drawn from the Multi-University Study of Culture and Identity (MUSIC). Participants were 1,081 Asian Americans (n = 684; M age = 19.75 years, SD = 1.93; 63% women; 35% foreign-born) and Latinos (n = 397; M age = 20.08 years, SD = 3.64; 72% women; 17% foreign-born) from 20 colleges and universities across the United States. For the MUSIC project, participants completed a wide range of psychological measures via a secure online survey in exchange for course credit. The measures that are relevant to the present study were completed during 2009, which was the second year that data were collected for the MUSIC project.

Measures

Descriptive statistics, alpha coefficients, and mean differences (by ethnicity and nativity) for each of the following measures are reported in Table 1. For the multiple-item measures, composite scores were computed by reverse coding negatively phrased items (when necessary) and averaging across scale items. Unless otherwise noted, responses were provided on a 5-point scale, anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree). As shown in Table 1, all measures had acceptable alpha coefficients indicating that the measures had adequate internal consistency.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Full sample (n = 1,081) | Foreign-born Asian Americans (n = 239) | U.S.-born Asian Americans (n = 445) | Foreign-born Latinos (n = 66) | U.S.-born Latinos (n = 331) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | α | M | SD | α | M | SD | α | M | SD | α | M | SD | α | M | SD | F(3, 1016–1078) |

| Foreigner objectification | .71 | 1.63 | 0.65 | .70 | 1.85 | 0.70b | .69 | 1.55 | 0.60a | .62 | 2.03 | 0.66c | .70 | 1.51 | 0.61a | 25.20** |

| Perceived discrimination | .81 | 2.99 | 0.72 | .78 | 2.86 | 0.66a | .79 | 2.94 | 0.65ab | .84 | 3.08 | 0.83bc | .83 | 3.12 | 0.80c | 6.86** |

| Identity denial | — | 2.67 | 1.15 | — | 2.60 | 1.08 | — | 2.73 | 1.11 | — | 2.47 | 1.14 | — | 2.68 | 1.24 | 1.32 |

| Self-esteem | .89 | 3.63 | 0.72 | .84 | 3.53 | 0.64a | .87 | 3.48 | 0.67a | .91 | 3.96 | 0.76b | .90 | 3.84 | 0.76b | 21.94** |

| Life satisfaction | .87 | 3.88 | 1.10 | .85 | 3.84 | 1.03a | .87 | 3.75 | 1.06a | .90 | 4.01 | 1.28ab | .87 | 4.08 | 113b | 6.12** |

| Depressive symptoms | .92 | 2.62 | 0.72 | .90 | 2.67 | 0.67 | .91 | 2.65 | 0.70 | .94 | 2.44 | 0.82 | .92 | 2.58 | 0.75 | 2.14 |

| Cognitive reappraisals | .90 | 4.85 | 1.15 | .86 | 4.72 | 1.08a | .89 | 4.73 | 1.12a | .90 | 5.08 | 1.36b | .90 | 5.06 | 116b | 7.30** |

| Emotional suppression | .77 | 3.88 | 1.21 | .73 | 4.04 | 1.12b | .75 | 3.98 | 1.16b | .81 | 3.57 | 1.32a | .80 | 3.69 | 1.28a | 6.43** |

| Familism | .88 | 3.66 | 0.58 | .89 | 3.91 | 0.60 | .88 | 3.61 | 0.57 | .85 | 3.73 | 0.53 | .89 | 3.69 | 0.60 | 2.33 |

Note. Pattern of mean differences indicated with subscript letters; similar letters indicate nonsignificant differences and successive letters indicate significantly higher values. Degrees of freedom vary across analyses because of different patterns of missing values.

p ≤ .01.

Foreigner objectification was assessed with the four-item Foreigner Objectification Scale (Pituc et al., 2009). Participants indicated the extent to which they had experienced the following during the previous year: (a) “Asked by strangers ‘Where are you from?’ because of your ethnicity/race,” (b) “Had someone speak to you in an unnecessarily slow or loud way,” (c) “Had someone comment on or be surprised by your English language ability,” and (d) “Had your American citizenship or residency questioned.” Responses were provided on a 5-point scale, anchored by 1 (never) and 5 (five or more times).

Perceptions of general ethnic discrimination were assessed with the nine-item Perceived Discrimination Subscale of the Scale of Ethnic Experiences (Malcarne, Chavira, Fernandez, & Liu, 2006). This measure includes items such as, “In my life, I have experienced prejudice because of my ethnicity” and “Generally speaking, my ethnic group is respected in America” (negatively phrased).

(American) identity denial was assessed with the item “How American do others perceive you to be?” (Rodriguez, Schwartz, & Kraus Whitbourne, 2010). Responses were provided on a 5-point scale, anchored by 1 (not at all American) and 5 (extremely American). Scores were reverse coded such that higher values indicate higher levels of identity denial.3

Psychological well-being was assessed in terms of self-esteem, life satisfaction, and depressive symptoms. Self-esteem was assessed with the 10-item Rosenberg (1965) Self-Esteem Scale, which includes items such as, “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.” Life satisfaction was assessed with the five-item Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985), which includes items such as, “In most ways my life is close to my ideal.” Depressive symptoms were assessed with a modified version of the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Participants indicated the extent to which they had experienced symptoms associated with depression (e.g., “I felt lonely”) during the previous week.

We used two additional measures for the purpose of examining the discriminant validity of the Foreigner Objectification Scale. First, we used the 10-item Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003), which assesses tendencies to respond to negative experiences by (a) cognitively reappraising the situation and (b) suppressing one’s emotions (emotional suppression). This measure includes items such as, “When I want to feel less negative emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation” (cognitive reappraisal) and “I keep my emotions to myself” (emotional suppression). Second, we used the 21-item Attitudinal Familism Scale (Lugo Steidel & Contreras, 2003), which assesses beliefs regarding the importance of familial interconnectedness, familial support, familial honor, and subjugation of self for the family. This measure includes items such as, “A person should cherish time spent with his or her relatives” and “A person should be a good person for the sake of his or her family.”

Results

Analytic Overview

We analyzed the data in three steps. We first examined the factor structure of the Foreigner Objectification Scale and whether its measurement properties (i.e., factor structure, factor loadings, and latent item intercepts) were invariant across ethnic (i.e., Asian American and Latino) and nativity (i.e., foreign-born and U.S.-born) groups. Second, we examined the associations between the Foreigner Objectification Scale and theoretically related (i.e., general perceptions of discrimination and identity denial) and ostensibly unrelated (i.e., emotion regulation and familism values) variables to test for convergent and discriminant validity, respectively, and whether these associations were moderated by ethnicity and/or nativity. Third, we examined our substantive hypotheses regarding the psychological consequences of foreigner objectification, statistically controlling for general perceptions of discrimination, and whether these associations were moderated by ethnicity and/or nativity.

All analyses were conducted within a latent variable framework using Mplus Version 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010) with full information maximum likelihood estimation to account for missing responses. Model fit was assessed with the comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Models were determined to provide a good fit to the data with CFI ≥ .95 and RMSEA ≤ .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999) and an adequate fit to the data with CFI ≥ .90 and RMSEA ≤ .10 (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). We also report the 90% confidence intervals (90% CIs) for RMSEA. Chi-square values are provided for each analysis but are not used to evaluate overall model fit as the chi-square test is inappropriate with large samples (Bollen, 1989). However, because there are no widely accepted or adequately validated alternatives to comparing the fit of nested models (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000; cf. Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), we used the chi-square change test for model fit comparisons.

Factor Structure and Measurement Invariance of the Foreigner Objectification Scale

Using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), we estimated a model in which the four Foreigner Objectification Scale items formed a single latent factor for the sample. This model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(2) = 9.54, p = .01, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .06 (90% CI [.03, .10]). Standardized factor loadings ranged from .50 to .77. We next estimated a series of multiple-group (MG) CFAs to examine whether the Foreigner Objectification Scale held similar measurement properties (i.e., structural, metric, and scalar invariance; Vandenberg & Lance, 2002) across the groups (i.e., foreign-born Asian Americans, U.S.-born Asian Americans, foreign-born Latinos, and U.S.-born Latinos). To consider structural invariance (i.e., factor structure), we first specified a model in which all of the measurement parameters were allowed to estimate separately for each group (unconstrained model). Inadequate model fit would be indicative of structural differences. To consider metric and scalar invariance, respectively, we next estimated models in which the factor loadings were constrained to be equivalent across the groups (constrained loadings model) and a model in which the latent item intercepts were constrained to be equivalent across the groups (constrained intercepts model). A significant drop in model fit for each successive model would indicate nonequivalent measurement properties.

The unconstrained model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(8) = 17.40, p = .03, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .06 (90% CI [.02, .10]), as did the constrained loadings model, χ2(20) = 34.54, p = .02, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .05 (90% CI [.02, .08]). The fit of the constrained loadings model did not differ significantly from that of the unconstrained model, Δχ2(12) = 17.14, p = .14, indicating full metric invariance. The constrained intercepts model did not provide an adequate fit to the data, χ2(32) = 134.85, p < .01, CFI = .88, RMSEA = .11 (90% CI [.09, .13]), and resulted in a significant drop in model fit, Δχ2(12) = 100.31, p < .001. LaGrange multiplier (LM) values indicated that a substantial source of model misfit resulted from differences between nativity groups, regardless of ethnicity. We thus specified a model in which the latent item intercepts were allowed to estimate separately for the two foreign-born and two U.S.-born groups, but constrained to be equal within foreign-born and U.S.-born groups. This model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(28) = 46.53, p = .02, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .05 (90% CI [.02, .07]), which did not significantly differ from the constrained loadings model, Δχ2(8) = 11.99, p = .15. Thus, full scalar invariance was demonstrated separately within the two foreign-born and two U.S.-born groups. However, scalar invariance was not evidenced between the foreign-born and U.S.-born individuals.

The final estimates indicated that foreign-born individuals had higher intercepts than their U.S.-born counterparts for each of the items. This indicates that, for any given item, to receive a score of 0 on the latent foreigner objectification factor, a higher observed response was necessary for foreign-born individuals than it was for their U.S.-born counterparts. As a result, for the scale as a whole, the same composite score (e.g., average across observed responses) would indicate a higher level of foreigner objectification for U.S.-born individuals than it would for foreign-born individuals. As such, mean comparisons between foreign-born and U.S.-born individuals using simple composite scores may lead to inaccurate inferences.

To consider whether the noninvariant latent item intercepts affected the mean comparisons reported in Table 1, which are based on composite mean scores, we estimated and saved the factor scores from separate CFA models for the foreign-born and U.S.-born participants. A one-way analysis of variance comparing the four groups using the factor scores was statistically significant, F(3, 773) = 2.67, p = .05.4 Fisher’s least significant difference test indicated a single statistically significant difference: Foreign-born Latinos were higher in foreigner objectification compared with U.S.-born Asian Americans (M difference in standardized units = .15, SE = .05, p < .01). Thus, the pattern of significant mean differences reported in Table 1 reflects different levels of average responses to the scale items, but not mean differences in the underlying foreigner objectification construct. Although critical for testing group mean differences, scalar invariance is not a necessary condition for testing structural associations (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). We thus proceeded with our additional analyses.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

To obtain the correlations of the Foreigner Objectification Scale to general perceptions of discrimination, identity denial, emotion regulation tendencies, and familism values, we estimated a series of MG CFAs. We used sets of item parcels as indicators for the measures with more than five items (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). To this end, within the relevant measures, we randomly assigned items to one of three sets, and computed item parcels by averaging the items within each item set. To take into consideration the nonreliability of the single-item identity denial variable, we specified a single-indicator latent factor with a reliability of .80 by fixing the factor loading to 1.00 and the residual error to .18, which was computed by multiplying the variance of the item by .20 (i.e., 1.00 minus the reliability estimate). To consider moderation by ethnicity and nativity, we compared a model in which the correlations between the Foreigner Objectification Scale and the remaining variables were constrained to be equal across groups (constrained model) with a model in which these correlations were allowed to estimate freely (unconstrained model). A significant drop in model fit would indicate that one or more of the associations is/are moderated by ethnicity, nativity, and/or both.

The unconstrained model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2(556) = 1061.06, p < .01, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .05, as did the constrained model, χ2(571) = 1084.96, p < .01, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .05. The constrained model did not result in a significant drop in model fit relative to the unconstrained model, Δχ2(15) = 23.90, p = .07, indicating that the associations were not moderated by ethnicity or nativity. For the sake of parsimony in reporting our results, we estimated a final CFA for the sample as a whole, which provided a good fit to the data, χ2(121) = 529.45, p < .01, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .05. Demonstrating convergent validity, the Foreigner Objectification Scale was positively and significantly associated with perceptions of more general forms of discrimination, r = .28, p < .01, and identity denial, r = .26, p < .01. These correlations fall close to medium effect sizes (r = .30; Cohen, 1988). Demonstrating discriminant validity, the Foreigner Objectification Scale was nonsignificantly associated with cognitive reappraisal tendencies, r = − .06, p = .11, emotional suppression tendencies, r = .05, p = .18, and familism values, r = − .01, p = .71. Importantly, our expectation that the Foreigner Objectification Scale may be less strongly (or nonsignificantly) associated with identity denial for foreign-born participants was not supported.

Test of Substantive Hypotheses

We estimated a series of MG structural equation models to test our substantive hypotheses. The model was specified as shown in Figure 1. We first specified a model in which the path coefficients were allowed to estimate separately for each group (unconstrained model) and compared it with a model in which the path coefficients were fixed to be equal across the groups (constrained model).

The unconstrained model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(486) = 774.46, p < .01, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .04 (90% CI [.04, .05]), as did the constrained model, χ2(519) = 835.70, p < .01, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .04 (90% CI [.04, .05]). However, the constrained model resulted in a significant drop in model fit relative to the unconstrained model, Δχ2(33) = 61.24, p = .002. Examination of the LM values suggested several differences, most of which were between foreign-born and U.S.-born individuals, regardless of ethnicity. Subsequently, we constrained the path coefficients from foreigner objectification to life satisfaction and depressive symptoms, and the path coefficient from identity denial to self-esteem, to be equal for the two foreign-born groups and separately for the two U.S.-born groups. The LM values indicated the need to unconstrain one final path coefficient, specifically, the path from perceptions of general discrimination to identity denial for U.S.-born Latinos. The resulting model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(515) = 814.59, p < .001, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .04 (90% CI [.04, .05]), and did not significantly differ from the fit of the unconstrained path model, Δχ2(29) = 40.13, p = .08.

The path coefficients for the direct associations are reported in the top portion of Table 2. We focus first on the direct and indirect (via identity denial) routes from foreigner objectification to the psychological well-being outcomes. As shown in the table, foreigner objectification was positively associated with identity denial, and identity denial was negatively associated with life satisfaction for all four groups. In addition, for the two U.S.-born groups only, identity denial was negatively associated with self-esteem, and foreigner objectification was negatively associated with life satisfaction and positively associated with depressive symptoms. There were no other statistically significant associations for foreigner objectification.

Table 2.

Direct, Indirect (Via Identity Denial), and Total Associations by Ethnicity and Nativity

| Foreign-born Asians | U.S.-born Asians | Foreign-born Latinos | U.S.-born Latinos | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association | b | SE | β | b | SE | β | b | SE | β | B | SE | β |

| Direct associations | ||||||||||||

| Foreigner objectification → | ||||||||||||

| Identity denial | .34 | .08 | .19** | .34 | .08 | .19** | .34 | .08 | .16** | .34 | .08 | .17** |

| Self-esteem | −.06 | .05 | −.05 | −.06 | .05 | −.04 | −.06 | .05 | −.04 | −.06 | .05 | −.04 |

| Life satisfaction | .24 | .14 | .13 | −.22 | .10 | −.10* | .24 | .14 | .10 | −.22 | .10 | −.09* |

| Depressive symptoms | .06 | .09 | .05 | .26 | .07 | .18** | .06 | .09 | .03 | .26 | .07 | .16** |

| Perceived discrimination → | ||||||||||||

| Identity denial | .09 | .06 | .06 | .09 | .06 | .07 | .09 | .06 | .08 | .29 | .07 | .26** |

| Self-esteem | −.12 | .03 | −.14** | −.12 | .03 | −.13** | −.12 | .03 | −.16** | −.12 | .03 | −.14** |

| Life satisfaction | −.24 | .05 | −.15** | −.24 | .05 | −.15** | −.24 | .05 | −.18** | −.24 | .05 | −.18** |

| Depressive symptoms | .12 | .04 | .12** | .12 | .04 | .12** | .12 | .04 | .15** | .12 | .04 | .13** |

| Identity denial → | ||||||||||||

| Self-esteem | −.05 | .04 | −.08 | −.14 | .03 | −.19** | −.05 | .04 | −.05 | −.14 | .03 | −.18** |

| Life satisfaction | −.10 | .04 | −.09* | −.10 | .04 | −.08* | −.10 | .04 | −.08* | −.10 | .04 | −.08* |

| Depressive symptoms | .03 | .03 | .04 | .03 | .03 | .03 | .03 | .03 | .04 | .03 | .03 | .03 |

| Indirect associations (via identity denial) | ||||||||||||

| Foreigner objectification → | ||||||||||||

| Self-esteem | −.02 | .01 | −.01 | −.05 | .02 | −.04** | −.02 | .01 | −.01 | −.05 | .02 | −.03** |

| Life satisfaction | −.03 | .02 | −.02* | −.03 | .02 | −.02* | −.03 | .02 | −.02* | −.03 | .02 | −.02* |

| Depressive symptoms | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 |

| Perceived discrimination → | ||||||||||||

| Self-esteem | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | −.04 | .01 | −.05** |

| Life satisfaction | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | −.03 | .01 | −.02* |

| Depressive symptoms | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 |

| Total associations | ||||||||||||

| Foreigner objectification → | ||||||||||||

| Self-esteem | −.07 | .05 | −.06 | −.10 | .05 | −.08* | −.07 | .05 | −.05 | −.10 | .05 | −.07* |

| Life satisfaction | .21 | .14 | .10 | −.25 | .10 | .11* | .21 | .14 | .08 | −.25 | .10 | .11* |

| Depressive symptoms | .07 | .09 | .05 | .27 | .07 | .18** | .07 | .09 | .04 | .27 | .07 | .17** |

| Perceived discrimination → | ||||||||||||

| Self-esteem | −.13 | .03 | −.15** | −.14 | .03 | −.14** | −.13 | .03 | −.17** | −.17 | .03 | −.19** |

| Life satisfaction | −.25 | .05 | −.16** | −.25 | .05 | −.16** | −.25 | .05 | −.19** | −.27 | .05 | −.20** |

| Depressive symptoms | .13 | .04 | .12** | .13 | .04 | .12** | .13 | .04 | .15** | .13 | .04 | .14** |

Note. The slight deviations in the total effects based on a summation of the direct and indirect effects reported in the table are due to rounding error.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

We used MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, and Sheets’ (2002) products of coefficients approach to compute standard error estimates to test the significance of the indirect (i.e., mediated) associations of foreigner objectification to the psychological well-being variables. The indirect associations are reported in the middle portion of Table 2. For all four groups, there was a significant negative indirect association between foreigner objectification and life satisfaction via identity denial. In addition, for the two U.S.-born groups only, there was a significant negative indirect association foreigner objectification and self-esteem via identity denial. There were no other statistically significant indirect associations for foreigner objectification. The net (i.e., combined direct and indirect) associations from foreigner objectification to the psychological well-being variables are shown in the bottom portion of Table 2. For the two U.S.-born groups only, the total associations from foreigner objectification to self-esteem and life satisfaction were negative and statistically significant, and the total association between foreigner objectification and depressive symptoms was positive and statistically significant. By contrast, for the two foreign-born groups, none of the total associations for foreigner objectification were statistically significant.

As shown in the top portion of Table 2, for all four groups, perceptions of more general forms of discrimination were negatively associated with self-esteem and life satisfaction, and were positively associated with depressive symptoms. In addition, for U.S.-born Latinos only, perceptions of more general forms of discrimination were positively associated with identity denial. As shown in the middle portion of Table 2, for U.S.-born Latinos only, there were statistically significant negative indirect associations (via identity denial) from perceptions of more general forms of discrimination to self-esteem and life satisfaction. There were no other statistically significant indirect associations for perceptions of more general forms of discrimination. As shown in the bottom portion of Table 2, for all four groups, the total associations from perceptions of more general forms of discrimination to self-esteem and life satisfaction were negative and statistically significant, and the association from perceptions of more general forms of discrimination to depressive symptoms was negative and statistically significant.

Discussion

The primary goal of the present study was to validate the Foreigner Objectification Scale (Pituc et al., 2009), a brief self-report measure of perceived foreigner objectification, and to examine whether identity denial mediated the associations between perceived foreigner objectification and psychological well-being. In all analyses, we examined whether ethnicity (i.e., Asian American and Latino) and/or nativity (i.e., foreign-born and U.S.-born) served as moderators. Our measurement analyses indicated that the Foreigner Objectification Scale was (a) adequately explained by a single latent factor, (b) held configural and metric invariance based on ethnicity and nativity, and (c) held scalar invariance for the two foreign-born groups and separately for the two U.S.-born groups, but (d) did not hold scalar invariance between foreign-born and U.S.-born individuals. We also demonstrated convergent and discriminant validity of the Foreigner Objectification Scale, which was positively and moderately associated with theoretically related constructs (i.e., perceptions of general discrimination and perceived identity denial) and was not significantly associated with ostensibly unrelated constructs (i.e., emotion regulation and familism values).

These results indicate that the Foreigner Objectification Scale holds measurement properties necessary to examine structural associations across foreign-born and U.S.-born Asian Americans and Latinos (i.e., configural and metric invariance) and is related to, but not synonymous with, more general experiences with discrimination and identity denial. However, the lack of scalar invariance indicates that differential intercepts must be taken into consideration for accurate mean comparisons across foreign-born and U.S.-born individuals. This was illustrated in our analyses, as the significant mean differences that emerged when comparing the groups using composite scale scores changed when the scalar noninvariance was taken into consideration.

Substantively, we tested the prediction that perceived foreigner objectification would be associated with less favorable psychological outcomes, above and beyond perceptions of more general forms of discrimination. However, we expected that nativity may moderate these associations, such that perceived foreigner objectification may not be as detrimental to the psychological well-being of foreign-born individuals relative to their U.S.-born counterparts. In support of this expectation, for U.S.-born Asian Americans and Latinos, greater perceptions of foreigner objectification were associated with less self-esteem and life satisfaction and more depressive symptoms (see Table 2, total associations). However, foreigner objectification was not significantly associated with self-esteem, life satisfaction, or depressive symptoms among foreign-born Asian Americans and Latinos.

We also predicted that, particularly for U.S.-born Asian Americans and Latinos, perceived identity denial (Cheryan & Monin, 2005; see also Branscombe et al., 1999), operationalized as the belief that one is not viewed by others as American, would at least partially mediate the association between perceived foreigner objectification and psychological well-being. This prediction was only partially supported. For U.S.-born individuals, perceived foreigner objectification was associated with greater perceived identity denial, which was in turn associated with lower levels of self-esteem and life satisfaction; identity denial fully accounted for the negative association between perceived foreigner objectification and self-esteem and partially accounted for the association between perceived foreigner objectification and life satisfaction. However, identity denial did not mediate the association between foreigner objectification and depressive symptoms for U.S.-born individuals.

As for foreign-born Asian Americans and Latinos, we argued that perceived foreigner objectification may have less (if any) connection to identity denial, relative to their U.S.-born counterparts. We further argued that identity denial may not be as strongly associated (if at all) with psychological well-being among foreign-born individuals, relative to their U.S.-born counterparts. Consequently, we did not expect identity denial to mediate the associations between perceived foreigner objectification and psychological well-being. Consistent with our predictions, identity denial was not significantly associated with self-esteem or depressive symptoms, and the indirect associations from perceived foreigner objectification to self-esteem and depressive symptoms via identity denial were not statistically significant. Contrary to our expectations, however, perceived foreigner objectification was associated with greater perceived identity denial, and identity denial was negatively associated with less life satisfaction to the same degrees as they were for U.S.-born individuals. Moreover, despite the nonsignificant total association between perceived foreigner objectification and life satisfaction (i.e., combined direct and indirect), the indirect association from perceived foreigner objectification to life satisfaction was negative and statistically significant.

Because our data are cross-sectional, we are unable to make any strong inferences from these results. However, we can offer some preliminary thoughts on our results. First, for U.S.-born individuals, it was clear that perceived foreigner objectification was associated with less favorable psychological outcomes. However, identity denial only mediated the associations of foreigner objectification to self-esteem and life satisfaction. This is inconsistent with predictions drawn from the social identity perspective (Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner et al., 1987) and other theoretical perspectives (e.g., Cheryan & Monin, 2005; North & Swann, 2009; Swann, 1983), which would suggest that identity denial would play a bigger role in mediating the associations between foreigner objectification and psychological well-being more broadly, including depressive symptoms. One possible explanation for this is that self-esteem is partially dependent on reflected appraisals (i.e., perceptions of how one is viewed by others; Cooley, 1902; Mead, 1934) and life satisfaction is more susceptible to the negative effects of identity denial, whereas depression may result from more complex psychological processes.

Alternatively, there is evidence that low self-esteem precedes depressive symptoms (Orth, Robins, & Roberts, 2008; Orth, Robins, Trzesniewski, Maes, & Schmitt, 2009; cf. Armenta, Sittner Hartshorn, & Whitbeck, 2012). Thus, foreigner objectification may be indirectly associated with depressive symptoms via multiple mediational mechanisms; that is, foreigner objectification → greater perceived identity denial → lower self-esteem → greater depressive symptoms. A follow-up analysis supported this possibility: The indirect association of perceived foreigner objectification to depressive symptoms via identity denial and self-esteem for U.S.-born individuals was statistically significant, b = .04, SE = .01, β = .03, p < .01. Further evidence, particularly from longitudinal studies, will be necessary to support the meditational processes suggested by these results as well as the results of our primary analyses.

As for foreign-born individuals, it appears that perceived foreigner objectification may convey the message that one is not perceived as American (i.e., identity denial), and does so to the same degree as it does for U.S.-born individuals. Moreover, it appears that not being perceived as American may have negative effects on foreign-born individuals’ feelings of life satisfaction. This highlights a potential limitation to our study; specifically, because we used a single-item indicator of identity denial, we are unable to determine whether or not our measure carries the same meaning for foreign-born individuals as it does for U.S.-born individuals. It is possible, for example, that not being viewed as American reflects identity denial (i.e., a self-threat reflecting the denial of an aspect of one’s identity) for U.S.-born individuals, given that they are more likely than their foreign-born counterparts to view themselves as American (further discussed below). For foreign-born individuals, on the other hand, not being viewed as American may not pose a threat to one’s personal identity, but nonetheless may impede his or her feelings of community connectedness and thus negatively affect his or her overall feelings of life satisfaction.

Finally, consistent with previous research (see Gee et al., 2007; D. L. Lee & Ahn, 2011; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009), perceptions of more general forms of discrimination were associated with less favorable psychological well-being (i.e., lower self-esteem and life satisfaction and higher depressive symptoms). These associations were statistically equivalent across ethnic and nativity groups. Interestingly, for U.S.-born Latinos only, perceptions of more general forms of discrimination were positively associated with identity denial. As a result, perceptions of more general forms of discrimination also had indirect negative associations to self-esteem and life satisfaction via identity denial. The reasons for this are not clear, although we can provide some preliminary thoughts. Specifically, U.S.-born Latinos, who perceive that they are just as American as their European American counterparts, have an ethnic and cultural lineage that is partially (or even fully) indigenous to the Americas (e.g., Aztec, Mayan, and Incan for Mexican Americans). As such, it is possible that U.S.-born Latinos perceive themselves as holding greater claim to the land that makes up the Americas, including the United States, and thus perceive more general forms of discrimination as a threat to their “American” identity. There are no data to substantiate this possibility; thus, we urge scholars to interpret this specific result with caution pending further empirical considerations.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are limitations to the present study that require attention, some of which have already been noted. First, the study relied on cross-sectional data, which limits our ability to make causal inferences. Second, our single-item measure of identity denial is at best a proxy of identity denial and does not capture this construct in all of its complexities (Cheryan & Monin, 2005), especially for foreign-born individuals. Third, data regarding the number of years in the United States for foreign-born participants were not collected, thus not allowing us to delineate between, for example, those individuals who have lived in the United States most or all of their life from more recent immigrants. Fourth, our sample included only college students, who may differ from the more general public in meaningful ways (Sears, 1986). Finally, our sample of foreign-born individuals was considerably smaller than our sample of U.S.-born individuals, especially when further broken down by ethnicity, thus raising concerns regarding the statistical power in testing associations. Clearly, replication of our findings using longitudinal and experimental designs with noncollege populations and more detailed assessments of mediating mechanisms is in order. This is especially true for foreign-born individuals, which will further require a larger sample and assessment of number of years in the United States.

Equally important for scholars to consider is the potential importance of within-group heterogeneity beyond the foreign-born/U.S.-born dichotomy. For example, although various Asian American (e.g., Chinese, Koreans) and Latino (e.g., Mexicans, Salvadorans) groups may have many similar experiences within the United States (e.g., targeted by discrimination), each individual group differs in important ways (e.g., social and economic status, physical appearance) that may further modify the associations observed in the present study. Physical and behavioral similarities to the perceived “prototypical American” (i.e., White American; Devos & Banaji, 2005) also are likely to be important. For example, Dovidio et al. (2010, Study 3) showed that individuals who perceived that they had a stronger nonstandard American accent reported a lower sense of belonging in the United States and more strongly felt like an outsider on the basis of their accent. Dovidio et al. (Study 2) also showed that White Americans viewed Latinos as moderately distinct from the prototypical American along ideological lines (e.g., values, beliefs) but viewed Asian Americans as substantially distinct from the prototypical American along ethnic lines (e.g., physical appearance). Other research has demonstrated that lighter skinned immigrants face less discrimination than their darker skinned counterparts (e.g., Hersch, 2011). However, Espino and Franz (2002) provided evidence that darker skin tone is associated with occupational discrimination among Mexicans and Cubans but not Puerto Ricans in the United States.

The findings of Espino and Franz (2002) highlight the complexities of specific ethnic backgrounds and physical characteristics in the experiences of Latinos in the United States, and at least raise the possibility that the same may be the case for other U.S. ethnic minority groups. Clearly, further understanding the experiences of U.S. ethnic minorities, and the psychosocial consequences of those experiences, requires more detailed consideration of specific heritage and physical characteristics. Correspondingly, as scholars continue to examine foreigner objectification, consideration of such factors will be necessary to gain a more accurate understanding of the psychosocial processes and consequences associated with perceived foreigner objectification.

Contextual effects also require attention. Indeed, psychological processes are likely to differ depending on the degree to which one is embedded in multiple levels of oppression (Perez & Soto, 2011). For example, Soto et al. (2012) showed that the psychological benefits of cognitive reappraisal tendencies (Gross & John, 2003) held for Latinos across the United States (a distally oppressive context, owing to ethnicity-based structural inequalities), with the exception of those who were living in predominately non-Latino communities (a proximally oppressive context, owing to greater likelihood of being exposed to bias) and perceived themselves as being oppressed (perceived personal oppression). Other contextual factors will be equally important to consider, such as the ethnic diversity within various proximal contexts (e.g., neighborhood, school, work; Seaton & Yip, 2009) and community attitudes toward and acceptance of specific ethnic minority groups.

In addition, the social identity perspective (Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner et al., 1987) suggests, and empirical evidence demonstrates (e.g., Armenta, 2010), that ethnic minorities who feel more strongly attached to their ethnic group are more likely to perceive and attend to situational cues that implicate their ethnicity. Relatedly, individuals are likely to respond differently to perceived foreigner objectification based on the degree to which one personally identifies with and positively values his or her ethnic group (Phinney, 1993; Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner et al., 1987; Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gómez, 2004). For example, an individual who holds negative attitudes toward and tries to distance him- or herself from his or her ethnic group may experience foreigner objectification as a categorization threat (i.e., being perceived and treated on the basis of group stereotypes; Branscombe et al., 1999). Responses to perceived foreigner objectification also are likely to vary based on the degree to which individuals personally identify and value their membership as an American. For example, perceived foreigner objectification may have more pronounced effects for individuals who highly value being an American.

Conclusions

Research on foreigner objectification is still in its infancy, and our study makes (at least) three important contributions to the literature. First, our results provide evidence that the Foreigner Objectification Scale (Pituc et al., 2009) is a valid measure for assessing the construct of perceived foreigner objectification. Second, we provided evidence that perceived foreigner objectification is particularly relevant to the psychological well-being of U.S.-born Asian Americans and Latinos. Third, our results indicate the importance of considering nativity status in studies with ethnic minorities. Even a quick perusal of recently published studies that include samples of ethnic minorities shows that nativity status is vastly ignored (cf. Pérez, Fortuna, & Alegría, 2008; Yip, Gee, & Takeuchi, 2008). Despite these contributions, our suggestions in the previous section make clear that much more work is necessary to better understand the psychological experiences and psychosocial consequences of perceived foreigner objectification. We hope that our study will stimulate further examinations of the role of foreigner objectification in the lives of Asian Americans, Latinos, and other U.S. ethnic minority groups.

Footnotes

Within the psychological literature, the perpetual foreigner stereotype is almost exclusively discussed in reference to Asian Americans. Scholars also have contended that the perpetual foreigner stereotype is applicable to Latinos (Rivera et al., 2010). In line with this contention, Torres-Harding et al. (2012) showed a nonsignificant difference between Asian Americans’ and Latinos’ perceptions of being treated as a foreigner.

It is important to note that objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997) was originally applied to, and has to our knowledge thus far been exclusively discussed in reference to, sexual objectification experiences among women. Nonetheless, the core of their theoretical perspective is seemingly applicable to other systems of categorization, including ethnicity. In addition, the broader literature on objectification includes race-based objectification (Eyben & Lovett, 2005; Rabinowitz, 2001; Radin, 1991).

We considered the possibility that our identity denial item simply reflects an aspect of perceived foreigner objectification by estimating a confirmatory factor model in which the foreigner objectification items and identity denial item served as indicators of a single latent factor. This model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(5) = 14.47, p = .01, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .04 (90% CI [.02, .06]). The good model fit is not unexpected given (a) that we had only a single item to assess identity denial and (b) theoretical reasons to expect a strong association between foreigner objectification and identity denial. More important, the standardized factor loading for the identity denial item was .22, whereas the remaining items ranged from .50 to .77, suggesting that our identity denial item does not simply reflect an aspect of perceived foreigner objectification.

We used this approach because none of the latent item intercepts were equivalent between foreign-born and U.S.-born participants, thus making model identification impossible for a mean comparison using a latent variable framework.

Contributor Information

Brian E. Armenta, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Kyoung-Rae Jung, University of Minnesota.

Irene J. K. Park, University of Notre Dame

José A. Soto, The Pennsylvania State University

Su Yeong Kim, University of Texas-Austin.

Seth J. Schwartz, University of Miami

References

- Armenta BE (2010). Stereotype boost and stereotype threat effects: The moderating role of ethnic identification. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 94–98. doi: 10.1037/a0017564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenta BE, & Hunt JS (2009). Responding to societal devaluation: Effects of perceived personal and group discrimination on the ethnic group identification and personal self-esteem of Latino/Latina adolescents. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 12, 23–39. doi: 10.1177/1368430208098775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armenta BE, Sittner Hartshorn KJ, & Whitbeck LB (2012). The associations between self-esteem and depressive symptoms among homeless adolescents: Findings from a 3-year, 12-wave longitudinal study. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow KM, Taylor DM, & Lambert WE (2000). Ethnicity in America and feeling “American”. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 134, 581–600. doi: 10.1080/00223980009598238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Ellemers N, Spears R, & Doosje B (1999). The context and content of social identity threat In Ellemers N, Spears R, & Doosje B (Eds.), Social identity: Context, commitment, content (pp. 35–58). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Cheryan S, & Monin B (2005). Where are you really from? Asian Americans and identity denial. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 717–730. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, & Rensvold RB (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Contrada RJ, Ashmore RD, Gary ML, Coups E, Egeth JD, Sewell A, … Chasse V (2001). Measures of ethnicity-related stress: Psychometric properties, ethnic group differences, and associations with well-being. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31, 1775–1820. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb00205.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley CH (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York, NY: Scribner’s. [Google Scholar]

- Devine PG (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 5–18. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devos T, & Banaji MR (2005). American = White? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 447–466. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos T, & Ma DS (2008). Is Kate Winslet more American than Lucy Liu? The impact of construal processes on the implicit ascription of a national identity. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47, 191–215. doi: 10.1348/014466607X224521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, & Griffin S (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, & Gaertner SL (2008). New directions in aversive racism research: Persistence and pervasiveness In Willis-Esqueda C (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (pp. 43–67). New York, NY: Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Gluszek A, John M, Ditlmann R, & Lagunes P (2010). Understanding bias toward Latinos: Discrimination, dimensions of difference, and experience of exclusion. Journal of Social Issues, 66, 59–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01633.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Espino R, & Franz MM (2002). Latino phenotypic discrimination revisited: The impact of skin color on occupational status. Social Science Quarterly, 83, 612–623. doi: 10.1111/1540-6237.00104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eyben R, & Lovett J (2005). Political and social inequality: A review: IDS Development Bibliography 20. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST (1998). Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination In Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, & Lindzey G (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed, Vol. 2, pp. 357–411). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, & Roberts T (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner SL, & Dovidio JF (1986). The aversive form of racism In Dovidio JF & Gaertner SL (Eds.), Prejudice, discrimination, and racism (pp. 61–89). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Spencer M, Chen J, Yip T, & Takeuchi DT (2007). The association between self-reported racial discrimination and 12-month DSM–IV mental disorders among Asian Americans nationwide. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 1984–1996. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & John OP (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman MD, Cheryan S, & Monin B (2011). Fitting in but getting fat: Identity threat and dietary choices among U.S. immigrant groups. Psychological Science, 22, 959–967. doi: 10.1177/0956797611411585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersch J (2011). The persistence of skin color discrimination for immigrants. Social Science Research, 40, 1337–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA (2007). Uncertainty-identity theory In Zanna MP (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 39, pp. 69–126). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hornsey MJ (2008). Social identity theory and self-categorization theory: A historical review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 204–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00066.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh Q, Devos T, & Smalarz L (2011). Perpetual foreigner in one’s own land: Potential implications for identity and psychological adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30, 133–162. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2011.30.2.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Thibodeau R, & Jorgensen RS (2011). Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 68–96. doi: 10.1037/a0021466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Wang Y, Deng S, Alvarez R, & Li J (2011). Accent, perpetual foreigner stereotype, and perceived discrimination as indirect links between English proficiency and depressive symptoms in Chinese American adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 47, 289–301. doi: 10.1037/a0020712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunda Z, & Spencer SJ (2003). When do stereotypes come to mind and when do they color judgment? A goal-based theoretical framework for stereotype activation and application. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 522–544. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, & Klonoff EA (1996). The Schedule of Racist Events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology, 22, 144–168. doi: 10.1177/00957984960222002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DL, & Ahn S (2011). Racial discrimination and Asian mental health: A meta-analysis. The Counseling Psychologist, 39, 463–489. doi: 10.1177/0011000010381791 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM (2005). Resilience against discrimination: Ethnic identity and other-group orientation as protective factors for Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 36–44. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.1.36 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, & Widaman KF (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo Steidel AG, & Contreras JM (2003). A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 312–330. doi: 10.1177/0739986303256912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, & Sheets V (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcarne VL, Chavira DA, Fernandez S, & Liu P (2006). The scale of ethnic experience: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Personality Assessment, 86, 150–161. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8602_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead GH (1934). Minds, self, and society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed). Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama Hall GC, & Barongan C (2002). Multicultural psychology.Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall/Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- North RJ, & Swann WB (2009). Self-verification 360°: Illuminating the light and dark sides. Self and Identity, 8, 131–146. doi: 10.1080/15298860802501516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum MC (1995). Objectification. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 24, 249–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1088-4963.1995.tb00032.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Berking M, & Burkhardt S (2006). Self-conscious emotions and depression: Rumination explains why shame but not guilt is maladaptive. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 1608–1619. doi: 10.1177/0146167206292958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Robins RW, & Roberts BW (2008). Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 695–708. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Robins RW, Trzesniewski KH, Maes J, & Schmitt M (2009). Low self-esteem is a risk factor for depressive symptoms from young adulthood to old age. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 472–478. doi: 10.1037/a0015922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Smart Richman L (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CR, & Soto JA (2011). Cognitive reappraisal in the context of oppression: Implications for psychological functioning. Emotion, 11, 675–680. doi: 10.1037/a0021254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, & Alegría M (2008). Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1993). A three-stage model of ethnic identity development in adolescence In Bernal ME & Knight GP (Eds.), Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities (pp. 61–79). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pituc SP, Jung K-R, & Lee RM (2009, August). Development and validation of a brief measure of perceived discrimination. Poster presented at the 37th Annual Asian American Psychological Association Conference, Toronto, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz D (2001). Natives with jackets and degrees: Othering, objectification and the role of Palestinians in the co-existence field in Israel. Social Anthropology, 9, 65–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8676.2001.tb00136.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radin MJ (1991). Reflections on objectification. Southern California Law Review, 65, 341–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera DP, Forquer EE, & Rangel R (2010). Microaggressions and the life experience of Latina/o Americans In Sue DW (Ed.), Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics, and impact (pp. 59–83). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez L, Schwartz SJ, & Kraus Whitbourne S (2010). American identity revisited: The relation between national, ethnic, and personal identity in a multiethnic sample of emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25, 324–349. doi: 10.1177/0743558409359055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sears DO (1986). College sophomores in the laboratory: Influences of a narrow data base on social psychology’s view of human nature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 515–530. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.3.515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, & Yip T (2009). School and neighborhood contexts, perceptions of racial discrimination, and psychological well-being among African American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 153–163. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9356-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto JA, Armenta BE, Perez CR, Zamboanga BL, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Lee RM, … Ham LS (2012). Strength in numbers? Cognitive reappraisal and psychological functioning among Latinos in the context of oppression. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18, 384–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears R (2011). Group identities: The social identity perspective In Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, & Vignoles VL (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 201–224). New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AMB, Nadal KL, & Esquilin M (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62, 271–286. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB (1983). Self-verification: Bringing social reality into harmony with the self In Suls J & Greenwald AG(Eds.), Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 2, pp. 33–66). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H (1969). Cognitive aspects of prejudice. Journal of Social Issues, 25, 79–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1969.tb00620.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Billig MG, Bundy RP, & Flament C (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1, 149–178. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420010202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, & Turner JC (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior In Worchel S & Austin WG (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Harding SR, Andrade AL, & Romero Diaz CE (2012). The Racial Microaggressions Scale (RMAS): A new scale to measure experiences of racial microaggressions in people of color. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18, 153–164. doi: 10.1037/a0027658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuan M (1998). Forever foreigners or honorary Whites? The Asian ethnic experience today. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC (1999). Some current issues in research on social identity and self-categorization theories In Elemers N, Spears R, & Doosje B (Eds.), Social identity: Context, commitment, content (pp. 6–34). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, & Wetherell MS (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, & Bámaca-Gómez M (2004). Developing the Ethnic Identity Scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 4, 9–38. doi: 10.1207/S1532706XID0401_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg RJ, & Lance CE (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 4–70. doi: 10.1177/109442810031002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, & Jackson JS (2003). Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 200–208. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YJ, Owen J, Tran KK, Collins DL, & Higgins CE (2012). Asian American male college students’ perceptions of people’s stereotypes about Asian American men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 13, 75–88. doi: 10.1037/a0022800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Gee GC, & Takeuchi DT (2008). Racial discrimination and psychological distress: The impact of ethnic identity and age among immigrant and United States-born Asian adults. Developmental Psychology, 44, 787–800. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HC, Steger MF, & Lee RM (2010). Validation of the Subtle and Blatant Racism Scale for Asian American College Students (SABR-A2). Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 323–334. doi: 10.1037/a0018674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]