Abstract

Three new coinage metal carbene complexes of silver and gold were synthesized from a thiamine inspired proligand. The compounds were characterized by HRMS, NMR spectroscopy (1H, 19F, 31P and 13C), FT-IR and elemental analysis. The coordination environment around the metal centers was correlated to the diffusion coefficients obtained from DOSY-NMR experiments and was in agreement with the nuclearity observed in the solid-state by single crystal X-ray crystallography. The silver and gold carbene compounds were subjected to MIC studies against a panel of pathogenic bacteria, including multidrug resistant strains, with the gold carbene derivative showing the most potent antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Keywords: carbene, silver, gold, thiamine, antimicrobial, antibiotic resistance

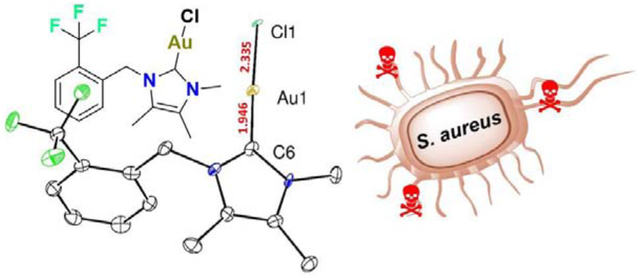

Graphical Abstract

Bioinspired gold carbene compound effective antibacterial against S. aureus

1. Introduction

The antibacterial properties of certain metal salts and alloys have been known since antiquity due to the biocidal oligodynamic effect.[1,2] For example, silver salts have been a recurring treatment for burns,[3] now still in use in the form of silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene) ointments.[4,5] Owing to the expansion of multidrug resistant bacterial strains, d-block transition metal containing drugs are becoming the target of new research as potential drug candidates, mainly for antitumoral,[6] antifungal,[7] antibacterial[8,9] or antiparasitic purposes.[10,11] A recent study found that compounds containing transition metal atoms exhibit a higher antimicrobial propensity compared to strictly organic molecules.[12] Transition metals, enabled by their unique reactivity and coordination chemistry, allow for multiple mechanisms of action[13,14] as well as the circumvention of certain resistance mechanisms by accessing novel chemical targets.[15]

When the surface of the skin is damaged, the nutrient-rich nature of the subepidermal environment is exposed, providing a hospitable and rich habitat for microorganisms to thrive. For this reason, wounds are highly susceptible to infection, particularly by pathogens already on the skin near the site of the wound.[16,17] Three of the bacterial species that are commonly associated with wound infections (Staphyolococcus aureus, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) belong to the so called ESKAPE pathogens: nosocomial, virulent, multi-drug resistant bacteria for which new, effective treatments are critically needed.[18] Scarcity of effective therapeutics has made treatment of bacterial infections difficult to manage and has put the antibiotic crisis among the most important threats to global healthcare systems.[19,20] Treatment of drug-resistant bacteria with compounds exhibiting novel mechanisms of action is more important than ever.

Transition metal complexes composed of a coinage metal (Cu, Ag, Au) and an N-heterocylic carbene ligand (NHC) have gained interest as antimicrobial metallodrugs.[8,20–29] The employment of coinage metal NHC complexes is ideal owing to the well-established high yield metalation protocols[31–36] and opportunities for transmetalation.[37] The vast chemical space to modify the easily accessible supporting imidazolium and related N-heterocyclic ligand scaffolds[38–40] enables enhanced antimicrobial activity.[41] Additionally, it can impart target specificity[42] for use in theranostics,[43] making these complexes a tremendous pool of potential drug candidates.

In our research groups we have recently turned our interest to exploring bioinspired ligands based on the Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) as a potential scaffold for the controlled release of antibacterial transition metal ions (Scheme 1). Thiamine features a thiazole based carbene that catalyzes the benzoin condensation reaction in human cells.[44] The presence of this persistent carbene allows for a metal binding site and the development of novel transition metal-thiamine inspired compounds with potential antibacterial properties. Herein we report the synthesis and characterization of our first-generation thiamine inspired silver and gold compounds and their antimicrobial activity against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Scheme 1.

Vitamin B1 and proligand 1. Below preparation of proligand 1 and its solid-state structure.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis of metal complexes

Proligand 1 was prepared by reacting 1,4,5-trimethylimidazol[45] and 2-trifluoromethylbenzylbromide in refluxing acetonitrile for 12 hours. The product was purified by precipitation of the crude reaction mixture with cold diethyl ether followed by recrystallization from the minimal amount of acetone yielding 1 in 81 % yield. To allow for activity comparison between silver and gold analogues the imidazol-2-ylidene fragment was favored vs. the thiazol-2-ylidene which is known to yield air sensitive compounds of the lighter coinage metals. No silver thiazol-2-ylidene complexes have been reported on the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. However, there are some examples of copper thiazol-2-ylidene[46–49] and gold thiazol-2-ylidene species [50–54]. Additionally, a-CF3 group was substituted in the benzylic part of the proligand to and enhance lypophilicity[58,59] and have an additional biologically exogenous spectroscopic handle for future experiments on the biological fate of these species [55–57]. Detailed procedures regarding synthetic protocols can be found in the supporting information. Proligand 1 showed a downfield imidazolium 1H-NMR signal at δ 9.04 ppm in d6-DMSO. In the solid-state, compound 1 crystallizes with 4 molecules of water per unit-cell that hydrogen bond with the bromide anions (Scheme 1).

The silver imidazol-2-ylidene complex 2 was prepared by reacting proligand 1 with Ag2O in dichloromethane solution in the absence of light. This method has proven to be an efficient route to generate silver carbene complexes before and is compatible with the cocrystallized water molecules of the proligand.[31] Metalation was followed by the disappearance of imidazolium proton resonance in the 1H-NMR spectrum and the compound was isolated by precipitation of the filtered reaction mixture with pentane. Upon metal binding the imidazol-2-ylidene 13C-NMR signal of 2 appeared at δ 179.2 ppm. Complex 4 was prepared by transmetalation of 2 using chloro(dimethyl sulfide)gold (I) producing an AgBr precipitate and dimethylsulfide as byproducts (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Metalation of 1 using Ag2O to yield compound 2 and 3. Compound 4 was prepared by transmetalation of 2.

The NMR data confirmed metalation but was not conclusive to confidently assign the structure of the metal compounds. No desymmetrization of the 19F-NMR-CF3 signal was observed either that could point to the nuclearity of the compounds. In solution, the complexes were studied by HRMS (ESI) to investigate the coordination environment around the metal center. Compound 2 is a cationic biscarbene complex (SI Fig. 18), the counter ion being [AgBr2]− as supported by the elemental analysis results. Compound 4 is a neutral complex, where the gold atom is bound to a single carbene proligand and a chlorine atom (SI Fig. 20).

To impart additional stability to the cationic silver biscarbene 2 the [AgBr2]− counter anion was substituted for a non-coordinating hexafluorophosphate [PF6]− anion. Biscarbene 3 can be prepared from 2 and KPF6 in dichloromethane causing immediate precipitation of AgBr and KBr or more conveniently in one step directly from 1, Ag2O and KPF6. Incidentally, the substitution of the anion later allowed us to compare the bactericidal activity of the silver biscarbene complexes without interference from the silver provided by the [AgBr2]− anion in the silver carbene complex 2.

It is known that the nuclearity of silver carbenes can be related to their biocidal potency.[60] To gain a further understanding of the solution dynamics and nuclearity of these compounds, the experimental diffusion coefficients (D) were obtained by DOSY-NMR and support the assignment of nuclearity by mass spectrometry, with a lower diffusion coefficient observed for the larger biscarbene 3 molecule (D = 2.21 cm2/s) vs. a higher coefficient observed for the smaller monocarbene 4 (D = 2.77 cm2/s) which is comparable in size to the the free proligand 1 with a diffusion coefficient of (D = 2.65 cm2/s).

The solid-state structures obtained by single crystal X-ray diffraction studies support the behaviour observed in solution. Colourless crystals of 3 were grown from a dichloromethane solution layered with pentane and cooled to −25 °C. Complex 3 crystallizes in the P-1 space group (Figure 1) with 4 independent molecules per unit cell and is a linear cationic biscarbene with an Ag-Ccarbene bond lengths of 2.091(2) Å and 2.094(2) Å. The molecular structure reveals that in the solid-state the benzylic residues are staggered by the interaction of the trifluorobenzyl rings [approximately 4.0 Å between the phenyl ring centroids] whereas in solution the carbenes can freely rotate anchored through the silver atom. The imidazol-2-ylidene rings are locked as well through the methylene carbon which causes them to twist with a 44° angle between the planes defined by the NHC rings. The linear C-Ag-C coordination axis is slightly bent (∠C6-Ag1-C20: 8.5°) presumably influenced by the trifluoromethylphenyl stacking acting through the methylene linker into the NHC heterocycle.

Figure 1.

Solid-state structure of 3. Hydrogen atoms and [PF6]− anion removed for clarity. Distances are given in Angstroms (Å).

Single crystals of compound 4 were grown as brittle colourless plates by slow vapor diffusion of pentane into a concentrated solution of dichloromethane cooled to −25 °C. The gold carbene crystallizes in the P21/c space group with 4 independent molecules per unit cell. The linear structure is shown in Figure 2. The Au-Ccarbene distance retracts to 1.946(7) Å, while the Au-Cl distance is elongated to 2.3353(13) Å.

Figure 2.

Solid-state structure of 4. Hydrogen atoms removed for clarity. Distances are given in Angstroms (Å).

2.2. Antimicrobial activity studies

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were obtained for the compounds against Gram-positive and Gram-negative species that are commonly associated with wound infections, including antibiotic resistant strains (Table 1). Solutions of the compounds were sterilized and filtered through 0.22 micron filters to eliminate the potential effect of metal nanoparticles on the bacterial growth.[61] Proligand 1 did not exhibit antimicrobial activity against any of the selected strains. Silver biscarbenes 2 and 3, which are coordinatively saturated NHC metal complexes both in the solid-state and solution, similarly were not effective in killing bacteria even with [PF6]- as counterion, pointing to a poor release of silver resulting in low availability of antibacterial metal ions. On the other hand, gold carbene 4 showed the most potent activity against methicillin-resistant strains of the Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus while displaying less activity against the Gram-negative A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa that have an outer membrane, which might prevent the compound’s uptake. This Gram-positive preference is known for other gold antibacterials and is modulated by the lipophilicity [62–64]. The lipophilicity of our compounds was estimated by RP-HPLC using the retention time values on a C18 column. Compound 4 is more lipophilic (tr = 11 min) compared to the parent proligand (tr = 8 min). MIC values for the MRSA strains in this study show gold carbene 4 to be more efficacious than the known silver topical antimicrobial silver sulfadiazine (6) and are as effective as AgNO3 (5). The gold carbene compound also outperforms the common gold precursor chloro(dimethylsulphide)gold(I) (7), likely due to the robust stability provided by the stronger Au-Ccarbene bond compared to the Au-SMe2 bond that is more easily exchanged.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations [MIC, μg/mL (μM)] for antibiotic-resistant bacteria and bacterial species commonly associated with wound infections.

| Compound | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

AgNO3 |  |

|

|

| S. aureus MU50a,d | >256 (>733) | >256 (>281) | >256 (>324) | 8 (16) | 16 (94) | 128 (358) | 64 (217) |

| S. aureus USA100 635a,d | >256 (>733) | >256 (>281) | >256 (>324) | 16 (32) | 16 (94) | 128 (358) | 64 (217) |

| S. aureus USA300 AH1263a,d | >256 (>733) | >256 (>281) | >256 (>324) | 16 (32) | 16 (94) | 128 (358) | 64 (217) |

| A. baumannii AYEb,c | >256 (>733) | >256 (>281) | >256 (>324) | 32 (64) | 4 (24) | 64 (179) | 64 (217) |

| A. baumannii 5075b,c | >256 (>733) | >256 (>281) | >256 (>324) | 32 (64) | 4 (24) | 64 (179) | 64 (217) |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1b | >256 (>733) | >256 (>281) | 256 (324) | 256 (511) | 2 (12) | 64 (179) | 64 (217) |

| P. aeruginosa PA14b | >256 (>733) | >256 (>281) | 256 (324) | >256 (>511) | 2 (12) | 32 (90) | 64 (217) |

Denotes Gram-positive bacterium.

Denotes Gram-negative bacterium.

Denotes multi-drug resistant strain.

Methicillin-resistant.

Conclusion

In summary, new bioinspired silver and gold imidazol-2-ylidene complexes were synthetized and characterized. The silver bis(carbene) complexes were not successful in inhibiting bacterial growth. However, the gold carbene complex showed promising activity against Gram-positive bacteria and outperformed the widely prescribed silver sulfadiazine antimicrobial. Our future steps follow this path and are geared toward synthetizing more potent, broad spectrum and more biomimetically relevant gold thiazol-2-ylidene compounds to test against these multidrug-resistant pathogens.

4. Experimental Methods

4.1. General methods

NMR (1H, 13C{1H}, 19F, 31P) data was acquired on a Bruker AVANCE III 500 Cryoprobe spectrometer and processed using MestReNova software. 19F-NMR was referenced to internal TMS signal (δ = 0 ppm)[65] using the absolute referencing function in the Mestrenova software package and peak assignment was aided by 2D-NMR experiments as needed. FT-IR spectra were obtained in a Nicolet iS50 FT-IR spectrometer using attenuated total reflectance (ATR). Mass spectrometry data was provided by the UT Austin Mass Spectrometry Facility. X-Ray Crystallography was performed in the UT Austin – X-Ray Diffraction Laboratory. CCDC 1963913–1963915 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. Elemental analysis was performed by Midwest Microlab Inc. Indianapolis, IN. Chemicals and solvents were purchased from commercial vendors and used as received. 1,4,5-trimethylimidazol was prepared as previously reported.[45]

4.2. MIC assay

Minimum inhibitory concentrations were determined using the broth microdilution method outlined by Hancock et. al.[66] Stock compounds were prepared at 10 mg/mL in sterile DMSO. From these stocks, 1 mg/mL solutions were prepared in Mueller-Hinton broth and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter. Dilutions of each compound, ranging from 1 μg/mL to 256 μg/mL (final concentrations) were prepared in Mueller-Hinton broth using the 1 mg/mL stocks. Compound dilutions were added to wells of a 96-well plate. Overnight bacterial cultures were diluted to ~106 CFU/mL in Mueller-Hinton broth and were added to wells in equal volume to that of compound dilutions, for a total volume of 100 μl. Plates were incubated for 24 hours at 37° C. The following day, plates were evaluated by eye to determine the MIC value. The concentration value corresponding to the first row that no longer had visible bacterial growth, as evaluated by turbidity in the wells, was recorded as the MIC. The reported values are representative of at least biological duplicates, each made up of technical triplicates.

4.3. Synthesis of 3-((2-trifluoromethyl)benzyl)-1,4,5-trimethylimidazolium bromide (1)

2-trifluoromethylbenzyl bromide (8.37 mmol, 2.00 g) and 1,4,5-trimethylimidazol (8.37 mmol, 0.92 g) were suspended in acetonitrile (8 mL). The mixture was refluxed 12 h. Upon cooling the yellow solution was poured into a beaker containing cold diethyl ether (30 mL). Upon addition an off-white solid precipitated, which was collected by vacuum filtration and washed with additional diethyl ether (3 × 10 mL). The solid was recrystallized from acetone at −25 °C. Title compound (1) was obtained as a white crystalline solid in 81% yield (2.37 g). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.04 (s, 1H, NHC-H), 7.88 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, Aryl-H), 7.72 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Aryl-H), 7.64 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Aryl-H), 7.09 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Aryl-H), 5.60 (s, 2H, -CH2-), 3.79 (s, 3H, N-CH3), 2.27 (s, 3H, -CH3), 2.09 (s, 3H, -CH3). 19F NMR (470 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ −59.38 (Aryl-CF3). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) 135.4 (NHC-CH), 133.6 (Aryl-CH), 132.1 (m, Cq), 129.1 (Aryl-CH), 128.7 (Aryl-CH), 127.9 (Cq), 126.6 (q, J = 5 Hz, HC-C-CF3), 126.3 (Cq), 126.3 (q, J = 30 Hz, C-CF3), 124.1 (q, J = 275 Hz, -CF3) 46.4 (m, -CH2-), 33.58 (N-CH3), 7.86 (-CH3), 7.80 (-CH3). HRMS (ESI): 269.1258 m/z [Calculated: 269.1260 m/z, C14H16F3N2+]. Melting Point 174–175 °C. Elemental Analysis Anal. Calc. for C14H16N2F3Br. ½ H2O: C, 46.94; H, 4.78; N, 7.82. Found: C, 47.00; H, 4.84; N, 7.80.

4.4. Synthesis of 2 [C28H30N4F6Br2Ag2]

To a solution of proligand 1 (0.57 mmol, 200 mg) in dichloromethane (15 mL) Ag2O (0.29 mmol, 66 mg) was added. The mixture was stirred in the absence of light for 12 hours. The solution was filtered through celite and the solvent removed under reduced pressure until approximately 1 mL remained and it was poured into a stirring vial containing pentane (10 mL). After stirring for a few minutes, a white solid precipitated which was identified as the title compound. (156 mg, 60 %). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.77 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H, Aryl-H), 7.58 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, Aryl-H), 7.50 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, Aryl-H), 6.67 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, Aryl-H), 5.44 (s, 4H, -CH2-), 3.72 (s, 6H, N-CH3), 2.19 (s, 6H, -CH3), 1.93 (s, 6H, -CH3). 19F NMR (470 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ −59.66 (Aryl-CF3). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 179.2 (NHC-C-Ag), 135.1 (Cq), 133.1 (Aryl-CH), 128.1 (Aryl-CH), 126.8 (Cq), 126.7 (Aryl-CH), 126.2 (q, J = 5.5 Hz,, HC-C-CF3), 125.5 (q, J = 30.5 Hz, C-CF3), 125.4 (Cq), 123.1 (q, J = 275 Hz, -CF3), 48.2 (m, -CH2-), 36.1 (N-CH3), 8.59 (-CH3), 8.29 (-CH3). HRMS (ESI): 643.1420 m/z [Calculated: 643.1423 m/z, C28H30AgF6N4+] Melting Point 158–159 °C Elemental Analysis Anal. Calc. for C28H30N4F6Br2Ag2: C, 36.87; H, 3.32; N, 6.14. Found: C, 36.89; H, 3.48; N, 6.02.

4.5. Synthesis of 3 [C28H30N4F12AgP]

Proligand 1 (0.29 mmol, 100 mg), Ag2O (0.15 mmol, 34 mg) and KPF6 (0.15 mmol, 27 mg) were combined in a vial and suspended in dichloromethane (5 mL). The suspension was stirred for 12 hours in the absence of light. The brown suspension was filtered through a 200 μm PTFE filter the resulting clear solution was concentrated to approximately 0.5 mL. Addition of pentane (10 mL) caused the title compound to precipitate as a white powdery solid which was washed with additional pentane (2 × 1 mL). Yield (104 mg, 91 %). Alternatively, this compound can be prepared by salt metathesis of 1 using KPF6. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.72 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.4 Hz, 2H, Aryl-H), 7.53 (td, J = 7.7, 1.4 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, Aryl-H), 6.63 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H, Aryl-H), 5.39 (s, 4H, -CH2-), 3.69 (s, 6H, N-CH3), 2.18 (s, 6H, -CH3), 1.93 (s, 6H, -CH3).19 F NMR (471 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ −59.76 (Aryl-CF), −69.92 (PF −6), −71.43 (PF6−) 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 179.2 (NHC-C-Ag), 135.0 (Cq), 133.0 (Aryl-CH), 128.0 (Aryl-CH), 126.8 (Cq), 126.6 (Aryl-CH), 126.0 (q, J = 5.7 Hz, HC-C-CF3), 125.5 (q, J = 30.4 Hz, C-CF3), 125.4 (Cq), 124.0 (q, J = 275 Hz, -CF3), 48.2 (m, -CH2-) 36.0 (N-CH3), 8.56 (-CH3), 8.26 (-CH3). 31P NMR (202 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ −144.74 (hept, J = 710 Hz). HRMS (ESI): 643.1418 m/z [Calculated: 643.1423 m/z, C28H30AgF6N4+] Melting Point 151–153 °C Elemental Analysis Anal. Calc. for C28 H30N4F12AgP CH2Cl2: C, 39.84; H, 3.69; N, 6.41. Found: C, 40.51; H, 3.70; N, 6.61.

4.5. Synthesis of 4 [C14H15N2F3AuCl]

Dimethyl sulphide gold chloride (0.22 mmol, 65 mg) was dissolved in dichloromethane (10 mL). Compound 2 (0.11 mmol, 100 mg) was added as a solid producing immediate precipitation of a grey solid (AgBr). After stirring for 2.5 hours the solution was filtered through celite and rotary evaporated to approximately 1 mL. The solution was poured into pentane (10 mL) and the title compound precipitates as a white powder recovered by vacuum filtration (76 mg, 69%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.83 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, Aryl-H), 7.65 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Aryl-H), 7.55 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Aryl-H), 6.68 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Aryl-H), 5.53 (s, 2H, -CH2-), 3.76 (s, 3H, N-CH3), 2.22 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.97 (s, 3H, -CH3). 19F NMR (470 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ −59.23 (Aryl -CF3). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.3 (NHC-C-Au), 134.4 (Cq), 133.2 (Aryl-CH), 128.2 (Aryl-CH), 126.7 (Cq), 126.3 (Aryl-CH), 126.2 (q, J = 5.7 Hz, HC-C-CF3), 125.5 (q, J = 30.5 Hz, C-CF3), 125.0 (Cq), 124.1 (q, J = 275 Hz, -CF3), 47.8 (m, -CH2-), 35.4 (N-CH3), 8.63 (-CH3), 8.28 (-CH3). HRMS (ESI): 523.0433 m/z [Calculated: 523.0434 m/z, C14 H15AuClF3N2Na+]. Melting Point 231–232 °C. Elemental Analysis Anal. Calc. for C14H15N2F3AuCl: C, 33.58; H, 3.02; N, 5.59. Found: C, 33.27; H, 3.00; N, 5.36.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research project was funded by Welch Foundation Grants (F-816, F-1870) and NIH R01 AI125337. The project that gave rise to these results received the support of “la Caixa” Banking Foundation (LCF/BQ/AA17/11610005) in the form of a fellowship for O.E.P. Bruker AVANCE III 500 Cryoprobe instrument was acquired thanks to NIH funding (1 S10 OD021508-01). We would like to thank Dr. Lindsey Shaw for kindly providing S. aureus isolate 635.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supporting information for this article can be found online at (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ica.2020.120152)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Silvestry-Rodriguez N, Sicairos-Ruelas EE, Gerba CP, Bright KR, Silver as a disinfectant, Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol 191 (2007) 23–45. 10.1007/978-0-387-69163-3_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Egorova KS, Ananikov VP, Toxicity of Metal Compounds: Knowledge and Myths, Organometallics. 36 (2017) 4071–4090. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Klasen HJ, Historical review of the use of silver in the treatment of burns. I. Early uses, Burns 26 (2000) 117–130. 10.1016/S0305-4179(99)00108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Klasen HJ, A historical review of the use of silver in the treatment of burns. II. Renewed interest for silver, Burns. 26 (2000) 131–138. 10.1016/S0305-4179(99)00116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Heyneman A, Hoeksema H, Vandekerckhove D, Pirayesh A, Monstrey S, The role of silver sulphadiazine in the conservative treatment of partial thickness burn wounds: A systematic review, Burns. 42 (2016) 1377–1386. 10.1016/j.burns.2016.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bertrand B, De Almeida A, Van Der Burgt EPM, Picquet M, Citta A, Folda A, Rigobello MP, Le Gendre P, Bodio E, Casini A, New gold(I) organometallic compounds with biological activity in cancer cells, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2014 (2014) 4532–4536. 10.1002/ejic.201402248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dar OA, Lone SA, Malik MA, Wani MY, Ahmad A, Hashmi AA, New transition metal complexes with a pendent indole ring: Insights into the antifungal activity and mode of action, RSC Adv. 9 (2019) 15151–15157. 10.1039/c9ra02600b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hackenberg F, Tacke M, Benzyl-substituted metallocarbene antibiotics and anticancer drugs, Dalt. Trans 43 (2014) 8144–8153. 10.1039/C4DT00624K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ray S, Mohan R, Singh JK, Samantaray MK, Shaikh MM, Panda D, Ghosh P, Anticancer and Antimicrobial Metallopharmaceutical Agents Based on Palladium, Gold, and Silver N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes, J. Am. Chem. Soc 129 (2007) 15042–15053. 10.1021/ja075889z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ong YC, Roy S, Andrews PC, Gasser G, Metal Compounds against Neglected Tropical Diseases, Chem. Rev 119 (2019) 730–796. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Salas PF, Herrmann C, Orvig C, Metalloantimalarials, Chem. Rev 113 (2013) 3450–3492. 10.1021/cr3001252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Frei A, Zuegg J, Elliott AG, Baker M, Braese S, Brown C, Chen F, Dowson CG, Dujardin G, Jung N, King AP, Mansour AM, Massi M, Moat J, Mohamed HA, Renfrew AK, Rutledge PJ, Sadler PJ, Todd MH, Willans CE, Wilson JJ, Cooper MA, Blaskovich MAT, Metal complexes as a promising source for new antibiotics, Chem. Sci 11 (2020) 2627–2639. 10.1039/c9sc06460e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Allardyce CS, Dyson PJ, Metal-based drugs that break the rules, Dalt. Trans 45 (2016) 3201–3209. 10.1039/C5DT03919C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Selvaganapathy M, Raman N, Pharmacological Activity of a Few Transition Metal Complexes: A Short Review, J. Chem. Biol. Ther 01 (2016) 1–17. 10.4172/2572-0406.1000108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mjos KD, Orvig C, Metallodrugs in medicinal inorganic chemistry, Chem. Rev 114 (2014) 4540–4563. 10.1021/cr400460s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cefalu JE, Barrier KM, Davis AH, Wound Infections in Critical Care, Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. North Am 29 (2017) 81–96. 10.1016/j.cnc.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bowler PG, Duerden BI, Armstrong DG, Wound Microbiology and Associated Approaches to Wound Management, Clin. Microbiol. Rev 14 (2001) 244–269. 10.1128/CMR.14.2.244-269.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mulani MS, Kamble EE, Kumkar SN, Tawre MS, Pardesi KR, Emerging Strategies to Combat ESKAPE Pathogens in the Era of Antimicrobial Resistance: A Review, Front. Microbiol 10 (2019). 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Antimicrobial Resistance Global Report on Surveillance, 2014.

- [20].Alanis AJ, Resistance to antibiotics: Are we in the post-antibiotic era?, Arch. Med. Res 36 (2005) 697–705. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Garrison JC, Youngs WJ, Ag(I) N-heterocyclic carbene complexes: Synthesis, structure, and application, Chem. Rev 105 (2005) 3978–4008. 10.1016/j.poly.2016.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Roland S, Jolivalt C, Cresteil T, Eloy L, Bouhours P, Hequet A, Mansuy V, Vanucci C, Paris JM, Investigation of a series of silver-N-Heterocyclic carbenes as antibacterial agents: Activity, synergistic effects, and cytotoxicity, Chem. - A Eur. J 17 (2011) 1442–1446. 10.1002/chem.201002812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Glišić BĐ, Djuran MI, Gold complexes as antimicrobial agents: an overview of different biological activities in relation to the oxidation state of the gold ion and the ligand structure, Dalt. Trans 43 (2014) 5950–5969. 10.1039/C4DT00022F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Melaiye A, Simons RS, Milsted A, Pingitore F, Wesdemiotis C, Tessier CA, Youngs WJ, Formation of Water-Soluble Pincer Silver(I)-Carbene Complexes: A Novel Antimicrobial Agent, J. Med. Chem 47 (2004) 973–977. 10.1021/jm030262m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Napoli M, Saturnino C, Cianciulli EI, Varcamonti M, Zanfardino A, Tommonaro G, Longo P, Silver(I) N-heterocyclic carbene complexes: Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity, J. Organomet. Chem 725 (2013) 46–53. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2012.10.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kascatan-Nebioglu A, Panzner MJ, Tessier CA, Cannon CL, Youngs WJ, N-Heterocyclic carbene-silver complexes: A new class of antibiotics, Coord. Chem. Rev 251 (2007) 884–895. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Johnson NA, Southerland MR, Youngs WJ, Recent developments in the medicinal applications of silver-nhc complexes and imidazolium salts, Molecules. 22 (2017) 1–20. 10.3390/molecules22081263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].O’Beirne C, Alhamad NF, Ma Q, Müller-Bunz H, Kavanagh K, Butler G, Zhu X, Tacke M, Synthesis, structures and antimicrobial activity of novel NHC*- and Ph3P-Ag(I)- Benzoate derivatives, Inorganica Chim. Acta 486 (2019) 294–303. 10.1016/j.ica.2018.10.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pöthig A, Ahmed S, Winther-Larsen HC, Guan S, Altmann PJ, Kudermann J, Andresen AMS, Gjøen T, Åstrand OAH, Antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity of Ag(I) and Au(I) pillarplexes, Front. Chem 6 (2018) 1–8. 10.3389/fchem.2018.00584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kascatan-Nebioglu A, Melaiye A, Hindi K, Durmus S, Panzner MJ, Hogue LA, Mallett RJ, Hovis CE, Coughenour M, Crosby SD, Milsted A, Ely DL, Tessier CA, Cannon CL, Youngs WJ, Synthesis from caffeine of a mixed N-heterocyclic carbene-silver acetate complex active against resistant respiratory pathogens, J. Med. Chem 49 (2006) 6811–6818. 10.1021/jm060711t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wang HMJ, Lin IJB, Facile synthesis of silver(I)-carbene complexes. Useful carbene transfer agents, Organometallics. 17 (1998) 972–975. 10.1021/om9709704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [32].de Frémont P, Scott NM, Stevens ED, Ramnial T, Lightbody OC, Macdonald CLB, Clyburne JAC, Abernethy CD, Nolan SP, Synthesis of Well-Defined N-Heterocyclic Carbene Silver(I) Complexes, Organometallics. 24 (2005) 6301–6309. 10.1021/om050735i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Visbal R, Laguna A, Gimeno MC, Simple and efficient synthesis of [MCI(NHC)] (M = Au, Ag) complexes, Chem. Commun 49 (2013) 5642 10.1039/c3cc42919a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Johnson A, Gimeno MC, An efficient and sustainable synthesis of NHC gold complexes, Chem. Commun 52 (2016) 9664–9667. 10.1039/C6CC05190A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Collado A, Gómez-Suárez A, Martin AR, Slawin AMZ, Nolan SP, Straightforward synthesis of [Au(NHC)X] (NHC = N-heterocyclic carbene, X = Cl, Br, I) complexes, Chem. Commun 49 (2013) 5541 10.1039/c3cc43076f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Veenboer RMP, Gasperini D, Nahra F, Cordes DB, Slawin AMZ, Cazin CSJ, Nolan SP, Expedient Syntheses of Neutral and Cationic Au(I)-NHC Complexes, Organometallics. 36 (2017) 3645–3653. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hintermair U, Englert U, Leitner W, Distinct reactivity of mono- and bis-NHC silver complexes: Carbene donors versus carbene-halide exchange reagents, Organometallics. 30 (2011) 3726–3731. 10.1021/om101056y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Benhamou L, Chardon E, Lavigne G, Bellemin-Laponnaz S, César V, Synthetic routes to N-heterocyclic carbene precursors, Chem. Rev 111 (2011) 2705–2733. 10.1021/cr100328e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hintermann L, Expedient syntheses of the N-heterocyclic carbene precursor imidazolium salts IPr·HCl, IMes·HCl and IXy·HCl, Beilstein J. Org. Chem 3 (2007) 2–6. 10.1186/1860-5397-3-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hans M, Lorkowski J, Demonceau A, Delaude L, Efficient synthetic protocols for the preparation of common N-heterocyclic carbene precursors, Beilstein J. Org. Chem 11 (2015) 2318–2325. 10.3762/bjoc.11.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gravel J, Schmitzer AR, Imidazolium and benzimidazolium-containing compounds: from simple toxic salts to highly bioactive drugs, Org. Biomol. Chem 15 (2017) 1051–1071. 10.1039/C6OB02293F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Li Y, Tan CP, Zhang W, He L, Ji LN, Mao ZW, Phosphorescent iridium(III)-bis-N-heterocyclic carbene complexes as mitochondria-targeted theranostic and photodynamic anticancer agents, Biomaterials. 39 (2015) 95–104. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Visbal R, Fernández-Moreira V, Marzo I, Laguna A, Gimeno MC, Cytotoxicity and biodistribution studies of luminescent Au(I) and Ag(I) N-heterocyclic carbenes. Searching for new biological targets, Dalt. Trans 45 (2016) 15026–15033. 10.1039/C6DT02878K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Breslow R, On the Mechanism of Thiamine Action. IV. Evidence from Studies on Model Systems, J. Am. Chem. Soc 80 (1958) 3719–3726. 10.1021/ja01547a064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chu Y, Deng H, Cheng J-P, An Acidity Scale of 1,3-Dialkylimidazolium Salts in Dimethyl Sulfoxide Solution, J. Org. Chem 72 (2007) 7790–7793. 10.1021/jo070973i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Raubenheimer HG, Cronje S, Olivier PJ, Toerien JG, van Rooyen PH, Synthesis and Crystal Structure of a Monocarbene Complex of Copper, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. English 33 (1994) 672–673. 10.1002/anie.199406721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Raubenheimer HG, Cronje S, Olivier PJ, Synthesis and characterization of mono(carbene) complexes of copper and crystal structure of a linear thiazolinylidene compound, J. Chem. Soc. Dalt. Trans 7006 (1995) 313–316. 10.1039/DT9950000313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Han X, Koh L, Liu Z, Weng Z, Hor TSA, Must an N-Heterocyclic Carbene Be a Terminal Ligand ?, (2010) 3369–3371. 10.1021/om100277f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Han X, Weng Z, Young DJ, Jin G-X, Andy Hor TS, Stoichiometric sensitivity and structural diversity in click-active copper(I) N,S-heterocyclic carbene complexes, Dalt. Trans 43 (2014) 1305–1312. 10.1039/C3DT52059E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Raubenheimer HG, Scott F, Kruger GJ, Toerien JG, Otte R, Van Zyl W, Taljaard I, Olivier P, Linford L, Formation and characterization of neutral and cationic amino(thio)carbene complexes of gold(I) from thiazolyl precursors, J. Chem. Soc. Dalt. Trans 1 (1994) 2091–2097. 10.1039/DT9940002091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kruger GJ, Olivier PJ, Raubenheimer HG, Bis(3-methyl-1,3-thiazolinylidene)gold(I) Trifluoromethanesulfonate, Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Cryst. Struct. Commun 52 (1996) 624–626. 10.1107/S0108270195011152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kruger GJ, Olivier PJ, Otte R, Raubenheimer HG, Bis[bis(4-methylthiazolin-2-ylidene)gold(I)] tetrachlorozincate dichloromethane, Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Cryst. Struct. Commun 52 (1996) 1159–1161. 10.1107/S0108270195015514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ruiz J, Perandones BF, Metal-induced tautomerization of oxazole and thiazole molecules to heterocyclic carbenes, Chem. Commun (2009) 2741–2743. 10.1039/b900955h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Dince CC, Meoded RA, Hilvert D, Synthesis and characterization of catalytically active thiazolium gold(I)-carbenes, Chem. Commun 53 (2017) 7585–7587. 10.1039/c7cc03791k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Barbosa TM, Morris GA, Nilsson M, Rittner R, Tormena CF, 1 H and 19 F NMR in drug stress testing: the case of voriconazole, RSC Adv. 7 (2017) 34000–34004. 10.1039/C7RA03822D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Xie D, King TL, Banerjee A, Kohli V, Que EL, Exploiting Copper Redox for 19 F Magnetic Resonance-Based Detection of Cellular Hypoxia, J. Am. Chem. Soc 138 (2016) 2937–2940. 10.1021/jacs.5b13215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Edwards JM, Derrick JP, van der Walle CF, Golovanov AP, 19 F NMR as a Tool for Monitoring Individual Differentially Labeled Proteins in Complex Mixtures, Mol. Pharm 15 (2018) 2785–2796. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Shah P, Westwell AD, The role of fluorine in medicinal chemistry, J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem 22 (2007) 527–540. 10.1080/14756360701425014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gillis EP, Eastman KJ, Hill MD, Donnelly DJ, Meanwell NA, Applications of Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry, J. Med. Chem 58 (2015) 8315–8359. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Budagumpi S, Haque RA, Endud S, Rehman GU, Salman AW, Biologically relevant silver(I)-N-heterocyclic carbene complexes: Synthesis, structure, intramolecular interactions, and applications, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem (2013) 4367–4388. 10.1002/ejic.201300483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Garner ME, Niu W, Chen X, Ghiviriga I, Abboud KA, Tan W, Veige AS, N-heterocyclic carbene gold(I) and silver(I) complexes bearing functional groups for bio-conjugation, Dalt. Trans 44 (2015) 1914–1923. 10.1039/c4dt02850c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Schmidt C, Karge B, Misgeld R, Prokop A, Brönstrup M, Ott I, Biscarbene gold(i) complexes: Structure-activity-relationships regarding antibacterial effects, cytotoxicity, TrxR inhibition and cellular bioavailability, Medchemcomm. 8 (2017) 1681–1689. 10.1039/c7md00269f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Mora M, Gimeno MC, Visbal R, Recent advances in gold-NHC complexes with biological properties, Chem. Soc. Rev 48 (2019) 447–462. 10.1039/c8cs00570b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Butorac RR, Al-Deyab SS, Cowley AH, Antimicrobial Properties of Some Bis(Iminoacenaphthene (BIAN)-Supported N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes of Silver and Gold, Molecules. 16 (2011) 2285–2292. 10.3390/molecules16032285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Harris RK, Becker ED, Cabral de Menezes SM, Goodfellow R, Granger P, NMR Nomenclature: Nuclear Spin Properties and Conventions for Chemical Shifts, Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson 22 (2002) 458–483. 10.1006/snmr.2002.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock REW, Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances, Nat. Protoc 3 (2008) 163–175. 10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.