Summary

BACKGROUND:

Dolutegravir (DTG) has been widely available in Brazil since 2017. Following the signal that infants born to women with DTG exposure at conception had a higher risk of neural tube defects (NTD), public health leaders initiated a national investigation.

METHODS:

All women with pregnancies and possible DTG exposure within 8 weeks of estimated date of conception (EDC) between January 1, 2015 and May 31, 2018, and approximately 3:1 matched pregnant women exposed to efavirenz (EFV), were identified using the Brazilian ART database. Detailed chart reviews were performed for identified women. Primary outcomes were NTD, stillbirth, and/or abortion. NTD incidences were calculated with 95% Wilson confidence intervals (95%CI). The composite outcome was examined with logistic regression using propensity score matching weights to balance confounders.

FINDINGS:

Of 1,427 included women, 382 were DTG-exposed within 8 weeks of EDC. During pregnancy, 48% of DTG-exposed and 45% EFV-exposed women received folic acid supplementation. There were 1,452 birth outcomes. There were no NTD in either DTG-exposed (0 [95%CI 0, 0·0010]) or EFV-exposed groups (0 [95%CI 0, 0·0036]). Twenty-five (6·5%) and 43 (4·0%) stillbirths/abortions occurred among DTG-exposed and EFV-exposed fetuses, respectively (p=0·05). Logistic regression models did not consistently indicate an association between DTG exposure and risk of stillbirths/abortions. After study closure, two confirmed NTD outcomes in fetuses with periconception DTG exposure were reported to public health officials. An updated estimate of NTD incidence incorporating these cases and the estimated number of additional DTG-exposed pregnancies through February 2019 is 0·0018 (95%CI 0·0005-0·0067).

INTERPRETATION:

Neither DTG or EFV exposure was associated with NTD in our national cohort; incidence of NTD is likely well under 1% among DTG-exposed HIV-positive women but still slightly above HIV-uninfected women (0.06%) in Brazil.

FUNDING:

The Brazilian Ministry of Health and the United States’ National Institutes of Health.

Keywords: dolutegravir, birth outcomes, neural tube, HIV, Brazil, ART

Introduction

Since the World Health Organization (WHO) included dolutegravir (DTG)-based antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens as a preferred first-line regimen, DTG use is rapidly increasing globally.1 The Brazilian Ministry of Health (BMoH) has provided universal and free access to ART since 19962 and included DTG in first-line ART regimens in 2017.3,4 Since then, BMoH has advised against DTG use among pregnant women . Pregnant women in Brazil not on ART should initiate an EFV-based regimen. In case of an unplanned pregnancy, a woman on DTG is recommended to switch to ritonavir-boosted atazanavir or raltegravir [RAL] (if after 14 weeks gestation).5,6

Based upon early results of a prospective study in Botswana, the WHO issued a warning May 18, 2018, of potential neural tube defects (NTD) in infants of mothers exposed to DTG at conception.7,8 Studies have shown no difference in rates of birth defects among women receiving ART compared to general populations,9,10 despite limitations inherent to evaluation of rare outcomes and comparison with HIV-negative populations.11 Importantly, women on ART at the time of conception have lower risk of perinatal HIV transmission to their infants.12 However, exposures during the first trimester of pregnancy are the most critical for a possible development of fetal abnormalities related to embryogenesis. NTD (iniencephaly, anencephaly, encephalocele, meningocele, myelomeningocele, and spina bifida) are caused by the failure of the neural tube closure during embryogenesis, which is estimated to occur by 4 weeks gestation.13 Brain NTD are particularly associated with fetal loss, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality. NTD are associated with maternal age, maternal use of antiepileptic medications, and maternal deficiency of folic acid, among others. Flour is fortified with folic acid in Brazil, and supplemental folic acid is recommended for all pregnancies, although use is unequal among women.14 In Brazil, NTD are rare (0.06% estimated prevalence).15 Following the WHO warning, BMoH advised all women of childbearing age on DTG to use reliable contraception.16

In May 2018, there were 22,624 Brazilian women on DTG aged between 15-49 years.4 In response to the WHO warning, we immediately initiated a national study to evaluate periconception DTG exposure among all pregnant Brazilian women with HIV and its potential association with risk of NTD, stillbirth, or abortion.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This observational, retrospective national cohort study used the Brazilian national ART database (SICLOM) and detailed chart review to confirm pregnancy details, periconceptional exposure, and birth outcomes. SICLOM registers every ART prescription, including drugs, formulations, start and stop dates. There is no ART delivery outside the public health system in Brazil. We identified all women with possible prenatal DTG exposure from January 1, 2017, to May 31, 2018, as: (1) all women with reported pregnancy and an immediately previous DTG-based regimen; (2) all women of childbearing age receiving DTG who switched to a pregnancy-recommended regimen for unclear reasons; (3) all women receiving DTG who received injectable or oral solution zidovudine and/or nevirapine as an indication of a birth event. To evaluate for a possible class-wide effect, we used the same methods to identify women potentially RAL-exposed at conception from January 1, 2015 (time of RAL introduction in Brazil) to May 31, 2018. A sufficiently large enough pool of women with possible periconceptional efavirenz (EFV)-exposure from January 1, 2015 to May 31, 2018 were identified and balanced by geographic location with women with possible DTG-exposure as a comparative cohort. As dates of conception are only estimates and to capture all potential exposures, we included any DTG, EFV, or RAL use at any point during the periconception window (defined below).

Assuming a NTD prevalence of 0·06% for births among DTG-unexposed women and a prevalence of 1·04% in the DTG-exposed women (the estimated prevalence from Botswana available at the time), with 363 DTG-exposed and 1,089 DTG-unexposed women (three unexposed for each exposed woman), we anticipated having approximately 73% power to statistically detect (p<0·05) a difference in NTD risk between exposure groups. The 3:1 ratio was chosen as 4:1 ratio would have resulted in 75% power, which would be an insufficient power gain to warrant the extra resources and time needed. A repeat power calculation using the final analysis cohort after removal of women meeting exclusion criteria provided similar power (74%) for detecting a difference.

Trained local abstractors performed standardized data collection from ART dispensaries, HIV and prenatal clinics, and hospitals and sites of delivery. Secure electronic data collection using pre-populated tablets included validation of pregnancy in the study period, medical and prenatal obstetric history, and birth outcomes (Protocol in Supplemental Materials). Abstractors received a list of possible DTG-, RAL- and EFV-exposed women in a ratio higher than 3:1 (i.e. >3 EFV-exposed to each DTG-exposed woman). They retrospectively investigated every woman identified as DTG- or RAL-exposed and a minimum of three EFV-exposed women to capture data recorded by medical providers. Abstractors were not blinded to ART exposures and recorded sources of NTD diagnoses by clinicians, such as clinical or radiographic exams. Data collection continued until March 18, 2019 to complete birth outcomes of all DTG-exposed women. CD4+ cell count and HIV RNA level were obtained from the Brazilian database which registers all tests within the public health system and almost all of these tests performed in the country.

Institutional review board and ethical approval for the study was obtained from the National Institute of Infectious Diseases Evandro Chagas (INI)-FIOCRUZ, the Brazilian National Research Ethics Commission, and Vanderbilt University.

Study population, outcomes, and exposure

We included women with confirmed DTG, RAL, or EFV exposure in the periconception window, defined as eight weeks before or after the estimated date of conception (EDC) to include the first four weeks of gestation during which time neural tube closure occurs and to account for accepted uncertainty regarding precise date of conception. Women who were found as not pregnant, with unknown birth outcomes or ART exposure, and with no periconceptional exposure to DTG, EFV or RAL were excluded. The primary outcomes were NTD and a composite measure of NTD, stillbirth, or abortion and were determined only by chart review (not by registries). Outcomes were assessed by individual fetuses/infants; in case of twins or triplets, all were included. Sensitivity analysis including only one fetus/infant per mother yielded similar results; all outcomes were the same for twins/triplets. NTD included any condition of the spectrum diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound or postnatally by clinical or radiographic measures. Abortions included fetal demise before 22 weeks estimated gestational age (EGA) and were accounted as spontaneous (although possible, elective abortions are illegal in Brazil and could not be confirmed through chart review). Stillbirths included fetal demise after 22 weeks EGA.

We calculated EDC by subtracting the EGA reported from the prenatal ultrasound occurring in the first or second trimester, or as the first day of the woman’s last menstrual period, or by subtracting an EGA obtained from a third trimester ultrasound or at the time of delivery (if previous options unavailable). Women with conflicting estimates were individually reviewed, and EDC was determined by panel review. Women whose EDC could not be calculated were excluded. ART start and stop dates were collected from SICLOM and confirmed upon chart review.

Variable definitions and statistical analysis

As women may have received more than one of the antiretrovirals of interest during the periconception window, our primary analysis compared outcomes of women with any DTG exposure to those who only received EFV during that period. Sensitivity analyses compared (1) women with only DTG- versus only EFV-exposure during periconception window and (2) only DTG- +/− RAL- versus only EFV-exposure during the periconception window. We computed Wilson 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for prevalence estimates of the primary outcomes. We did not examine ART exposures beyond the periconception period of pregnancy.

Due to the rarity of our primary outcome, we used propensity score methods to adjust for pertinent baseline and prenatal confounders. We first calculated propensity scores for the probability of periconceptional DTG-exposure. We fit two propensity score models using logistic regression. The first propensity score model included only covariates at EDC including age, education, race, region, years since HIV diagnosis, years since ART initiation, CD4+ count (closest +/− 6 months), HIV RNA (closest +/− 90 days), history of diabetes, epilepsy and/or use of antiepileptic drug, tobacco, alcohol and crack/cocaine use, number of previous pregnancies, previous adverse pregnancy outcome (≥1 abortion, stillbirth, preterm birth, birth defect, or neonatal death), body mass index, and folic acid use before pregnancy. To account for causes of stillbirth and abortion beyond just NTDs and periconception events, we fit a second propensity score model which included, in addition to the above, pertinent perinatal confounders including any folic acid use, number of prenatal visits, prenatal syphilis, any diabetes, gestational hypertension, and average weight gain per week during pregnancy. Matching weights were assigned to women based on their propensity scores to balance covariates between the two exposure groups and make them more comparable; matching weights permit the inclusion of all women and do not require selecting a caliper.17-18 We estimated the odds of the composite outcome by periconceptional ART exposure using logistic regression with these matching weights derived from the propensity score models.18 Missing values were imputed using multiple imputation with 20 replications. We computed the 95%CI from the primary logistic regression analysis using the 2·5th and 97·5th percentiles of 1,000 bootstrap replications for each imputed dataset and combined using Rubin’s rules. All covariates were chosen prior to performing regression analyses based on perceived scientific relevance and availability. All analyses were performed using R statistical software version 3·5·3, and analysis codes are available at http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/ArchivedAnalyses.

Role of funding sources

This study was supported by the BMoH and the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Study design, implementation, and analysis were jointly performed by investigators from the BMoH, INI–FIOCRUZ, and Caribbean, Central, and South America network for HIV epidemiology (CCASAnet).

Results

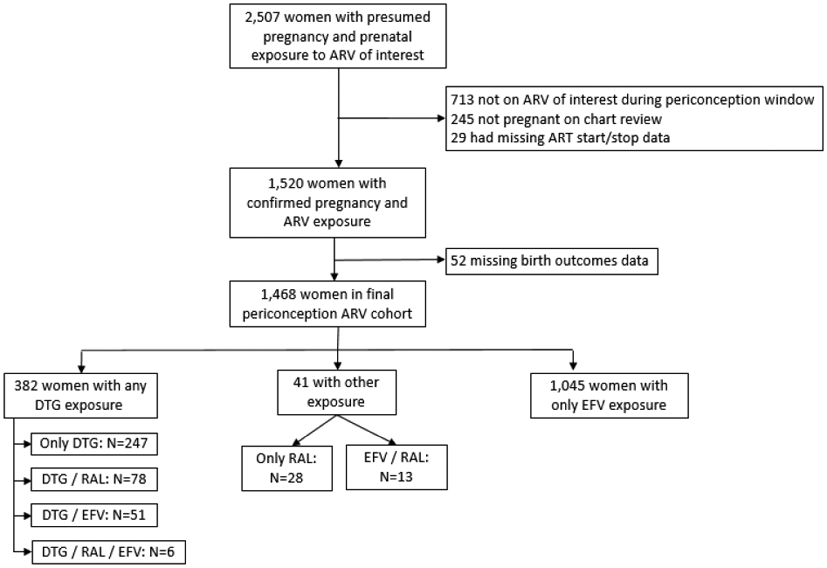

Out of the complete list of women with possible pregnancies exposed to DTG, RAL, or EFV identified during the study period (n=3,390), 2,507 were selected for investigation, including all DTG-exposed women (Supplemental Figure 1). The 883 women not investigated were exclusively EFV-exposed pregnancies unnecessary to meet planned 3:1 ratio of EFV:DTG-exposure groups. Among women investigated, 1,039 did not meet exposure inclusion criteria and were excluded (Figure 1). Among those excluded, there were two NTD: one infant was born with myelomeningocele and spina bifida to a woman who started RAL at 9 weeks gestation and another born with myelomeningocele to a woman who started ART at 10 weeks gestation. Neither woman had any DTG exposure before or during pregnancy. There were five DTG-exposed women who were excluded due to missing birth outcome data.

Figure 1. Flow chart of cohort creation.

Abbreviations used:

ARV: antiretroviral

ART: antiretroviral therapy

DTG: dolutegravir

RAL: raltegravir

EFV: efavirenz

Characteristics of the 1,427 women with periconceptional DTG exposure (n=382) and exclusive periconceptional EFV exposure (n=1,045) are shown in Tables 1 and 2 (characteristics of all women are shown in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2, pages 1-6 of the appendix). There were three EFV-exposed women who had a clinical Zika diagnosis during pregnancy (none had confirming molecular tests available).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of periconceptionally DTG- and EFV-exposed women at estimated date of conception, Brazil, 2015-2018.

| Only EFV regimen (N=1045) |

Any DTG regimen (N=382) |

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Age in years, median [IQR] | 28·5 [23·3-33·3] | 26·6 [21·9-31·9] | 0·0003 |

| Race, n (%) | 0·86 | ||

| Mixed | 464 (44) | 157 (41) | |

| White | 379 (36) | 143 (37) | |

| Black | 116 (11) | 47 (12) | |

| Asian | 8 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Indigenous | 5 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Unknown | 73 (7) | 31 (8) | |

| Education levelb | 0·28 | ||

| 0-3 years | 70 (7) | 16 (5) | |

| 4-7 years | 335 (34) | 132 (36) | |

| 8-11 years | 458 (47) | 174 (48) | |

| ≥12 years | 122 (12) | 41 (11) | |

| Region | 0·81 | ||

| Southeast | 391 (37) | 147 (39) | |

| South | 308 (30) | 101 (26) | |

| Northeast | 159 (15) | 65 (17) | |

| North | 116 (11) | 43 (11) | |

| Midwest | 71 (7) | 26 (7) | |

| Year of conception | 2017 [2017-2017] | 2017 [2017-2018] | <0·0001 |

| ARV of Interest Exposure History | |||

| Days of DTG use during periconception window (maximum: 112 days) | 0 | 103·5 [76-112] | |

| Days of EFV use during periconception window (maximum: 112 days) | 112 [99-112] | 13 [8-22] | |

| Days of RAL use during periconception window (maximum: 112 days) | 0 | 13·5 [6-24] | |

| Any DTG use before periconception window | 2 (0) | 235 (62) | |

| Any DTG use after periconception window | 48 (5) | 292 (76) | |

| Any EFV use before periconception window | 771 (74) | 22 (6) | |

| Any EFV use after periconception window | 1026 (98) | 155 (41) | |

| Any RAL use before periconception window | 1 (0) | 49 (13) | |

| Any RAL use after periconception window | 132 (13) | 226 (59) | |

| HIV Medical History | |||

| Year of HIV diagnosisc | 2014 [2011-2016] | 2017 [2014-2017] | <0·0001 |

| Year of ART initiation | 2017 [2017-2017] | 2017 [2017-2017] | <0·0001 |

| Years since HIV diagnosisc | 2·8 [1·4-6·0] | 0·7 [0·3-2·7] | <0·0001 |

| Years since ART initiation | 0·4 [0·2-0·8] | 0·3 [0·1-0·6] | <0·0001 |

| CD4+ cell count (cells/μL)d | 604 [420-844] | 530 [375-751] | 0·0025 |

| HIV RNA below the limit of detectione | 465 (75) | 139 (58) | <0·0001 |

| History of opportunistic infection | 105 (10) | 52 (14) | 0·057 |

| Other Comorbidities | |||

| Psychiatric disease | 61 (6) | 31 (8) | 0·12 |

| Pulmonary disease | 46 (4) | 17 (5) | 0·97 |

| Hypertension | 36 (3) | 19 (5) | 0·18 |

| Diabetes | 16 (2) | 10 (3) | 0·17 |

| Other metabolic diseases | 31 (3) | 11 (3) | 0·93 |

| Epilepsy or use of antiepileptic medications | 16 (2) | 11 (3) | 0·098 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 12 (1) | 6 (2) | 0·53 |

| Pulmonary disease | 46 (4) | 17 (5) | 0·97 |

| Neurological disease | 8 (1) | 7 (2) | 0·080 |

| Autoimmune disease | 19 (2) | 4 (1) | 0·31 |

| Obstetrical History | |||

| Number of previous pregnancies | 2 [1-3] | 2 [1-3] | 0·043 |

| History of adverse pregnancy outcomef | 360 (34) | 128 (34) | 0·74 |

| Behavioral Variablesg | |||

| Tobacco use | 199 (19) | 78 (20) | 0·56 |

| Alcohol use | 171 (16) | 77 (20) | 0·094 |

| Illicit substance use | 113 (11) | 54 (14) | 0·084 |

| Crack/cocaine use | 21 (2) | 7 (2) | 0·83 |

Continuous variables examined using Wilcoxon rank-sum test and categorical variables examined using Chi square test of proportions.

Education data available for 1348 women.

Date of HIV diagnosis available for 1332 women.

CD4+ cell count within 6 months of estimated date of conception available for 943 women.

HIV RNA within 90 days of estimated date of conception available for 859 women. Limit of detection is 40 copies/mL.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes include abortion, stillbirth, preterm birth, birth defect, or neonatal death.

Behavioral variables coded as positive if use recorded as occurring before and/or during the pregnancy.

Abbreviations used:

EFV: efavirenz

DTG: dolutegravir

ART: antiretroviral therapy

IQR: interquartile range

Table 2.

Prenatal and perinatal characteristics of periconceptionally DTG- and EFV-exposed women, Brazil, 2015-2018.

| Only EFV regimen (N=1045) |

Any DTG regimen (N=382) |

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy characteristics & Prenatal care | |||

| Multiple fetuses (twins or triplets) | 21 (2) | 2 (1) | 0·048 |

| Body mass index at conceptionb | 24·5 [21·6-28·3] | 23·7 [20·8-27·8] | 0·83 |

| Average weight gain per week (kg)c | 0·3 [0·2-0·4] | 0·3 [0·2-0·5] | 0·78 |

| Less than 6 total prenatal visits | 392 (38) | 175 (46) | 0·0046 |

| Medications during pregnancy | |||

| Number of ART regimens, median [IQR] | 1·0 [1·0-2.0] | 2·0 [2·0-2·0] | <0·0001 |

| Folic acid supplementation, n (%) | 0·27 | ||

| Only before pregnancy | 18 (2) | 11 (3) | |

| Only during pregnancy | 465 (45) | 183 (48) | |

| Before and during pregnancy | 25 (2) | 10 (3) | |

| Unknown | 537 (51) | 178 (46) | |

| Prenatal vitamin during pregnancy | 102 (10) | 36 (9) | 0·85 |

| Prenatal infections | |||

| Syphilis | 61 (6) | 40 (11) | 0·0025 |

| Toxoplasmosis | 15 (1) | 9 (2) | 0·23 |

| Varicella | 3 (0) | 2 (1) | 0·50 |

| Cytomegalovirus | 23 (2) | 6 (2) | 0·46 |

| Zika | 3 (0) | 0 (0) | 0·29 |

| Tuberculosis | 5 (1) | 3 (1) | 0·49 |

| Non-infectious prenatal comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes or gestational diabetes | 50 (5) | 19 (5) | 0·88 |

| Gestational hypertension | 33 (3) | 25 (7) | 0·0041 |

| Perinatal complications | |||

| Preterm labor | 43 (4) | 15 (4) | 0·87 |

| Premature rupture of membranes | 26 (3) | 9 (2) | 0·89 |

| Pre-eclampsia | 12 (1) | 8 (2) | 0·18 |

Continuous variables examined using Wilcoxon rank-sum test and categorical variables examined using Chi square test of proportions.

Body mass index data at conception available for 767 women.

Weight data during pregnancy available for 904 women.

Abbreviations used:

EFV: efavirenz

DTG: dolutegravir

ART: antiretroviral therapy

IQR: interquartile range

There were no observed NTD among birth outcomes of women periconceptionally DTG- and EFV-exposed (Table 3, results of all women shown in Supplemental Table 3, pages 7-8 of the appendix). The estimated NTD prevalence for DTG-exposed infants was 0 (95%CI 0-0·0010) and 0 (95%CI 0-0·0036) in EFV-exposed infants. Our composite outcome was more frequent in DTG-exposed fetuses (n=25, 7% [95%CI 0·044-0·094]) compared to those EFV-exposed (n=43, 4% [95%CI 0·030-0·054]) due to a higher frequency of abortions among DTG-exposed pregnancies (6 vs. 3%). Of women with periconceptional DTG exposure, the proportion of birth outcomes that were abortions decreased from 29% in 2017 (5/17) to 7% (11/168) in January 1-June 30, 2018 to 1% (2/167) in July 1-December 31, 2018. Maternal and prenatal characteristics are described by birth outcome in Supplemental Tables 4-6 (pages 9-16 of the appendix).

Table 3.

Birth outcomes of periconceptionally DTG- and EFV- exposed women, Brazil, 2015-2018.

| Only EFV regimen (N=1068) |

Any DTG regimen (N=384) |

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth outcomes | |||

| Neural tube defects, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Outcome | 0·0037 | ||

| Live birth | 1025 (96) | 359 (93) | |

| Stillbirth | 15 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Abortion | 28 (3) | 23 (6) | |

| Fetus number | 0·014 | ||

| Singleton | 1024 (96) | 380 (99) | |

| Twin | 38 (3) | 4 (1) | |

| Triplet | 6 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Sex, Gestational Age & Anthropometries | |||

| Male sexb | 526 (51) | 172 (48) | 0·24 |

| Gestational age at delivery in weeksc,median [IQR] | 39 [38-39] | 39 [38-39] | 0·85 |

| Birth weightd (grams) | 3048 [2740-3365] | 3012 [2748-3310] | 0·44 |

| Other congenital birth defectse | |||

| Any congenital abnormality | 59 (6) | 18 (5) | 0·53 |

| Polydactyly | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0·45 |

| Talipes equinovarus | 4 (0) | 0 (0) | 0·23 |

| Cleft palate | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0·018 |

| Cardiac birth defect | 5 (0) | 1 (0) | 0·59 |

| Digestive system birth defects | 3 (0) | 0 (0) | 0·30 |

| Urinary system birth defects | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0·095 |

| Genitalia abnormality | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 0·79 |

| Other birth defects | 4 (0) | 1 (0) | 0·74 |

Continuous variables examined using Wilcoxon rank-sum test and categorical variables examined using Chi square test of proportions.

Sex data available for 1384 infants.

Gestational age at delivery data available for 1321 infants.

Birth weight data available for 1363 infants.

Congenital defects as recorded in any birth outcome.

Abbreviations used:

EFV: efavirenz

DTG: dolutegravir

ART: antiretroviral therapy

IQR: interquartile range

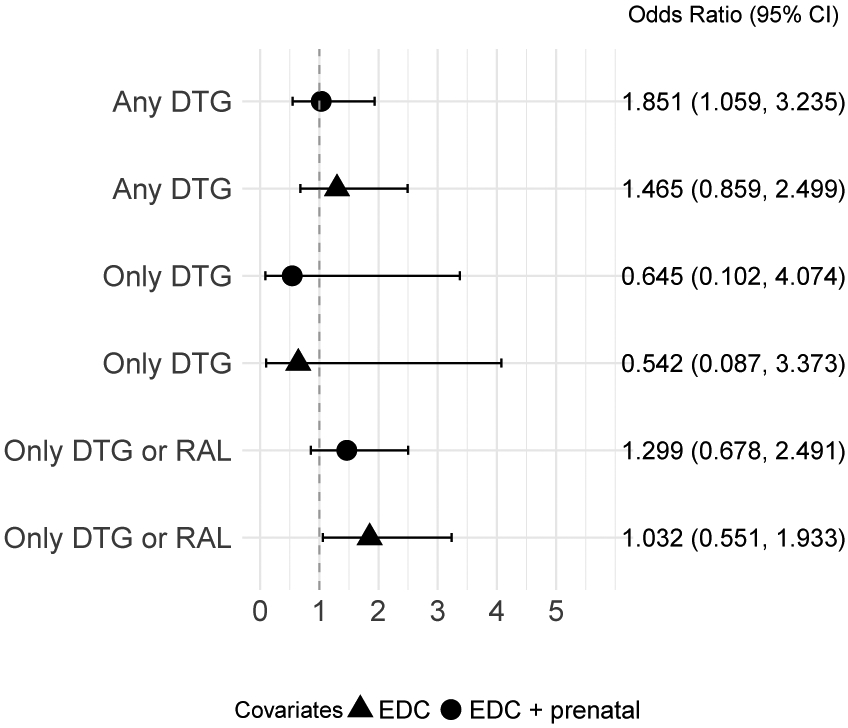

Figure 2 shows the odds ratios of the composite outcome according to DTG exposure from both weighted models. Supplemental Figures 2 and 3 show adequate balance of propensity scores. In the first model, any periconceptional DTG exposure was associated with an 85% increased odds of the composite outcome compared to exclusive EFV periconceptional exposure. This association was attenuated in the second model that also included prenatal variables. However, in the sensitivity analysis restricted to exclusive DTG versus EFV periconceptional exposure, DTG exposure was associated with decreased odds of the composite outcome in both models with and without prenatal variables, albeit with very wide 95%CI. When analyses were restricted to women with only RAL or DTG exposure, there was a 30% increased odds of the composite outcome compared to exclusive EFV exposure; results were attenuated when prenatal variables were added.

Figure 2. Weighted odds ratio of primary and sensitivity logistic regression analyses for composite outcome (NTD, stillbirth, or abortion) and DTG exposure.

EFV-only exposure used as reference group for all models. Triangle symbol indicates propensity model balanced for EDC covariates. Circle symbol indicates propensity model balanced for EDC and prenatal covariates.

Abbreviations used:

NTD: neural tube defect

DTG: dolutegravir

RAL: raltegravir

EFV: efavirenz

CI: confidence interval

EDC: estimated date of conception

Updated NTD incidence estimate

During manuscript preparation, we were informed of two NTD cases that occurred after our study data close date (both outcomes after March 31, 2019) to women on DTG. Periconceptional DTG-exposure among those two women was confirmed by detailed chart review at the BMoH. Due to the importance of those cases and the urgent need to verify the prevalence estimates, we performed a second search of the national ART database for women potentially exposed to DTG at the time of conception. We queried the database in a similar manner to the initial study described above from June 1, 2018, to February 28, 2019, and found exactly 900 women who were potentially exposed to DTG during pregnancy. We were unable to do an extensive chart review of these women. However, assuming a similar percentage of these women were truly exposed to DTG during conception as seen in our earlier chart review (382/490 = 78%) and assuming there were no additional cases of NTD among these women (which is reasonable given reporting requirements), then an updated incidence of NTD among women exposed to DTG at conception is 2 / (0·78 * 900 + 382) = 0·0018 or 1·8 per 1,000 DTG-exposed pregnancies (95%CI 0·5-6·7 per 1,000 DTG-exposed pregnancies).

Discussion

We observed no occurrences of NTD in this Brazilian national cohort study of women with periconceptional DTG exposure occurring before the WHO warning on May 18, 2018. There were two occurrences of NTD among fetuses exposed to DTG reported to BMoH after the WHO warning. An estimated NTD incidence including these cases and the estimated number of women with periconceptional DTG after the WHO issuance remained well below 1% (0·18% [95%CI 0·05-0·67]), though higher than previous estimates in the general population in Brazil (0.06%). Through a systematic and intensive public health investigation, this study adds important data to the critical question surrounding the safety of DTG for women. This study also underscores the need for ongoing monitoring of birth outcomes in pregnant women living with HIV. The updated database query revealed an unexpectedly high number of women potentially exposed to DTG near conception after the WHO warning and instructions from the BMoH, highlighting the importance of continued pharmacovigilance, particularly in settings of limited family planning services and contraception.

This study adds data into the international investigation of increased risk of NTD associated with periconceptional DTG exposure. This concern is particularly acute in low- and middle-income countries where DTG is expected to replace EFV in first-line ART regimens as a result of its high barrier to resistance, virologic potency, and lower side effect profile.19 It is projected that 15 million PLWH will be on DTG by 2025, many of whom will be women of childbearing age.20 Since the initial report from the Botswana study indicating a signal for NTD risk associated with periconception DTG exposure, additional reports have shown the rarity of NTD among women with periconceptional DTG exposure. The updated results of the Botswana study documented lower prevalence of NTD among DTG-exposed women (prevalence 0·3%), though the rate remained elevated compared to DTG-unexposed groups.21 An additional surveillance study led by the Ministry of Health of Botswana observed one NTD among 152 women with DTG exposure at conception, a prevalence higher than those for women with other ART exposures at conception and HIV-negative women.22 Data from the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry observed one NTD event among 248 periconceptionally DTG-exposed women mostly from the US.23 Our evaluation of 382 Brazilian women is the largest cohort of women with periconceptional DTG exposure and birth outcomes reported since the Botswana study results were first described. However, even with this size, it is likely that our study was underpowered to detect a difference in NTD risk given its rare occurrence (particularly in settings with folic acid fortification) and in light of the updated results from Botswana.

We observed an increased frequency of abortions among women exposed to DTG; however, this observation was not conclusive. Due to differences in abortions, models suggested higher odds of the composite outcome among those with any periconceptional DTG exposure in the primary analysis, a finding attenuated in the second model adding pertinent prenatal variables. The increased odds, however, was not replicated in sensitivity analyses which restricted the comparison to women only exposed to DTG in the periconception window, suggesting that other factors during pregnancy may be confounding our results. We did not observe an increase in abortions in the months following the WHO warning of risk of NTD from DTG exposure, although we cannot exclude the possibility of elective abortions obtained by women with DTG exposure as these details are not routinely recorded in medical records. Additionally, as data are not available for most abortions, it is also possible the increased risk could be related to other birth defects. Studies of women exposed to DTG later in pregnancy have not found significant increased risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes including stillbirths and abortions.24-27

As a retrospective study, there are inherent limitations to this study. While SICLOM and chart review allowed for careful collection of ART exposure history, our results may still be subject to misclassification due to uncertainty of timing of conception. We used initial ultrasound dates to calculate EDC in 76% of women to reduce this risk. Many women received multiple ART regimens during the periconception period; we used sensitivity analyses to address this limitation. Collection of outcomes can also be biased in retrospective analyses. Data abstractors were not blinded to previous ART when investigating birth outcomes though periconception exposure was only determined during data analyses. Capture of all NTD events from medical records was believed to be complete given Brazil’s high rate of prenatal ultrasounds and births occurring in medical settings with availability of perinatal specialists capable of documenting diagnoses.28 We are also limited by missing data. Multiple strategies were employed to identify women who became pregnant while receiving ART using the national databases; however, it is possible that some pregnancies were missed using this system, such as if women women became pregnant and had abortions without alerting their HIV medical providers. Researchers went to extreme efforts to obtain maternal and birth outcome data on all women, but ART or birth data were still not available on occasion. Notably, we thoroughly investigated all women and their birth outcomes identified as potential DTG exposures and only 5 women with DTG exposure were excluded due to missing outcomes. Additionally, to ensure an adequate number of EFV-exposed women to serve as a comparator cohort, EFV-exposed vs. DTG-exposed women had slightly different calendar years of inclusion and it is possible that other temporal changes occurring during the study period resulted in unmeasured confounding. Lastly, our updated prevalence estimate has inherent limitations including uncertainty of the accuracy of denominator, possibility of additional NTDs that were not reported, and lack of comparison estimate of NTDs among women with EFV exposure during the same period. The BMoH will continue to investigate those women by performing additional chart reviews to improve our estimates besides strengthening the DTG-pharmacovigilance in Brazil.

This study importantly adds data from one of the largest middle-income countries with early adoption of DTG in first-line ART regimens. There is a public health imperative to clarify the teratogenicity associated with periconceptional DTG exposure.29 High-quality data are required to inform consideration of risk of a very rare yet devastating birth outcome and restriction of use of highly-effective, well-tolerated ART in women of childbearing age.30 This intensive investigation is one example of the immediate public health consequences of the WHO warning, which resulted in interruption of HIV treatment and restriction of DTG use among women of childbearing age globally.31 However, our updated prevalence estimates also revealed a high number of women estimated to have DTG exposure around the time of conception despite national guidance regarding restricting its use only to women with reliable birth control. This surprise finding serves as a reminder of the importance of not only increased access to family planning services and birth control options for women with HIV, but also challenges in rapid implementation of national ART treatment guidelines. Moreover, the question of DTG and NTD has highlighted the need for pharmacovigilance programs to evaluate pregnancy outcomes among women living with HIV, and these complex data will increasingly come from public health sources such as ours.11,32 Collaborative and synergistic perspectives of medical research, public health, and women living with HIV themselves are needed to advise global policy regarding ART use in women.

Panel

Evidence before:

This study was designed in the weeks following release of the WHO’s warning of a potential risk of neural tube defects (NTD) after dolutegravir (DTG) exposure at the time of conception, which led to immediate changes in HIV treatment recommendations for women of childbearing potential. The warning was based upon results from a Botswana study, of which, out of 426 women exposed to DTG at conception, four gave birth to infants with NTD (0·94%) compared to 0·10% among those exposed to other antiretrovirals. Since that initial warning, updated data from the Botswana study showed a decreased prevalence compared to the initial evaluation though statistically increased compared to women on non-DTG regimens (0·30% vs 0·10%). Other recent smaller studies from Botswana demonstrated increased NTD prevalence among women with DTG exposure (1 among 152 women or 0·66%) but statistical analyses comparing risk to other groups included the null. Lastly, data from North America and Europe using the Antiretroviral Pregnancy registry observed 1 NTD event among 248 DTG-exposed women (0·4%).

Added value:

This study reports detailed investigation of an additional 382 women with periconceptional DTG exposure before the May 2018 warning and reports no occurrence of NTD events among these women. We report two cases of NTD with DTG exposure at conception that occurred after the WHO warning and an incidence of 0·18% including these women and the estimated number of women with pregnancies exposed to DTG at the time of conception from June 2018-February 2019. Importantly, these data come from a large middle-income country where DTG use in first-line antiretroviral therapy regimens was early adopted.

Implications of all available evidence:

Since the May 18, 2018, release of the Botswana study findings, our study significantly adds to the data on women exposed to DTG around the time of conception and of whom no or low excess risk of NTD events have been reported. Along with other recent data supporting the safety of DTG use in women who become pregnant and patient advocacy, the WHO updated its HIV treatment recommendations for women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We recognize the data collection efforts of Benisia Maria Barbosa Cordeiro Adell, Carla Joelma Villares Guimarães Marcel, Danielle Portela Ferreira, Janete Duarte Teixeira Duarte, José Alfredo de Sousa Moreira, Joseane Pessanha Ferreira, Luciana Castaneda Ribeiro, Lucrecia Helena Loureiro, Wilsa Mary Sousa dos Santos, Akemi Fuonke, Ana Cristina Barbosa, Carolina Simone Souza Adania, Cláudia Camargo Lorite, Cristina Magnabosco, Dirce Maria de Moura Prado, Luiz Roberto Lourena, Maria Cristina Longo, Maria Emilia Braite, Michelle Abou Dehn, Norma Noguchi, Tatiane Comerio, Cristiane Campos Monteiro, Maria Ângela dos Santos Pereira, Renata Siqueira Julio, Rita Sibele de Souza Esteve, Luciana Melo de Moura, Adriana Queiroz de Campos, Miriam Estela de Souza Freire, Aneth da Silva Benites Lino, Thiago Theodoro Martins Prata, Izôlda Maria Passos Lucena, Maria Joelma Pereira da Silva, Adriana Raquel Nunes de Souza, Ana Celia da Silva Moura, Chriscie Klen de Melo Rodrigues, Jeanne Silva da Costa, Valdirene Oliveira Cruz, Andréa Carolina Chagas de Miranda, Carla Gisele Ribeiro Garcia, José Arimateia Rodrigues Reis, Rutineide Queiroz Pantoja, Caroline Biserra Costa da Luz, Dayana Tenório da Silva Mendonça, Luciana Maria Rodrigues de Oliveira, Fabrina Lopes Ferreira, Heloise Maria Morais de Andrade, Joselina Soeiro de Jesus, Maria Vilani de Matos Sena, Telma Alves Matins, Joseneide Teixeira Câmara, Joanna Angelica Araujo Ramalho, Andreza da Silva Sontos, Lavínia Sobral Barreto Nunes, Márcia Maria Cavalcanti Marcondes, Mônica da Silva Pinto Cronemberger, Simone Alli Fernandes Farias, Stella Rosa de Sousa Leal, Bruna Emanuelle Feitosa Vasconcelos, Andrea Maciel de Oliveira Rossoni, Deisy Rodrigues Felicio de Souza, Glaucia Harumi Maruo Kanabushi, Maysa Mabel Fauth, Hellen Corrêa Teixera Cordeiro, Jacqueline A. Pruner Polidoro, Juliana Rita Pinheiro, Andreza Madeira Macário, Carla Félix dos Santos, Daniela Dal Forno Kinalski, Emanuele Lopes Ambrós, Lisiane Bernhard Hinterhol, Silvia Marielli da Costa Madeira, Solange de F. Mohd Suleiman Shama, Virginia de Menezes Portes, and Simone Gonçalves Senna for performing the primary data collection. Data collection, quality, and supervision was performed by G Winkler, L Garritano, S Gomes, S Fruet, F Rick, F Fernandes Fonseca, R Ribeiro, A Beber, and EM Jalil.

Funding Sources

This study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Health. This work was supported by the NIH-funded Caribbean, Central and South America network for HIV epidemiology (CCASAnet), a member cohort of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (leDEA) (U01AI069923). This award is funded by the following institutes: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and the Office of the Director, National Institutes Of Health (OD).

Funding Sources:

1. Brazilian National Ministry of Health

2. National Institutes of Health: U01AI69923

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests: All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Organization WH. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral durgs for treating and preventing HIV infection: World Health Organization, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federal Government of Brazil. Federal Law 9,313. Brasilia, Brazil; 1996. Available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L9313.htm. Accessed June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brazilian Ministry of Health. Protocolo clínico e diretrizes terapêuticas para manejo da infecção pelo HIV em adultos, 2017. Brasilia, Brazil; 2017. Available at http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2013/protocolo-clinico-e-diretrizesterapeuticas-para-manejo-da-infeccao-pelo-hiv-em-adultos. Accessed June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brazilian Ministry of Health. Relatório de Monitoramento Clínico Do HIV. Brasilia, Brazil; 2018. Available at http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2018/relatorio-de-monitoramento-clinico-do-hiv-2018. Accessed June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brazilian Ministry of Health. Disponibilidade de dolutegravir 50mg Ofício-Circular N 003/2017-GAB/DDAHV/SVS/MS. Brasilia, Brazil; 2017. Available at http://azt.aids.gov.br/documentos/siclom_operacional/Of%C3%ADcio%20circular%20003_2017%20-%20disponibilidade%20dolutegravir%2050mg.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brazilian Ministry of Health. Nota Informativa Complementar N 019/2017-DDHAV/SVS/MS. Brasilia, Brazil; 2017. Available at http://azt.aids.gov.br/documentos/Nota%20Informativa%20COMPLEMENTAR%20019-2017.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization; Potential safety issue affecting women living with HIV using dolutegravir at the time of conception. Geneva, Switzerland; 2018. Available at https://www.who.int/hiv/mediacentre/news/dtg-statement/en/. Accessed June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zash R, Makhema J, Shapiro RL. Neural-Tube Defects with Dolutegravir Treatment from the Time of Conception. N Engl J Med 2018; 379(10): 979–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joao EC, Calvet GA, Krauss MR, et al. Maternal antiretroviral use during pregnancy and infant congenital anomalies: the NISDI perinatal study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 53(2): 176–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berard A, Sheehy O, Zhao JP, et al. Antiretroviral combination use during pregnancy and the risk of major congenital malformations. AIDS 2017; 31(16): 2267–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zash RM, Williams PL, Sibiude J, Lyall H, Kakkar F. Surveillance monitoring for safety of in utero antiretroviral therapy exposures: current strategies and challenges. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2016; 15(11): 1501–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandelbrot L, Tubiana R, Le Chenadec J, et al. No perinatal HIV-1 transmission from women with effective antiretroviral therapy starting before conception. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(11): 1715–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene ND, Copp AJ. Neural tube defects. Annu Rev Neurosci 2014; 37: 221–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbosa L, Ribeiro Dde Q, de Faria FC, Nobre LN, Lessa Ado C. [Factors associated with folic acid use during pregnancy]. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2011; 33(9): 246–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santos LM, Lecca RC, Cortez-Escalante JJ, Sanchez MN, Rodrigues HG. Prevention of neural tube defects by the fortification of flour with folic acid: a population-based retrospective study in Brazil. Bull World Health Organ 2016; 94(1): 22–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brazilian Ministry of Health Recomendações sobre o uso do dolutegravir. Nota Informative N 10/2018-DIAHV/SVS/MS. Brasilia, Brazil; 2018. Available at http://azt.aids.gov.br/documentos/nota_informativa_n_10-2018_uso_do_dolutegravir_1.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983; 70: 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, Greene T. A weighting analogue to pair matching in propensity score analysis. Int J Biostat 2013; 9(2): 215–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization; Transition to New Antiretrovirals in HIV Programmes. Geneva, Switzerland; 2017. Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255888/1/WHOHIV-2017.20-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta A, Juneja S, Vitoria M, et al. Projected Uptake of New Antiretroviral (ARV) Medicines in Adults in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Forecast Analysis 2015-2025. PLoS One 2016; 11(10): e0164619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zash R, Holmes L, Diseko M, et al. Neural-Tube Defects and Antiretroviral Treatment Regimens in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raesima MM, Ogbuabo CM, Thomas V, et al. Dolutegravir Use at Conception - Additional Surveillance Data from Botswana. N Engl J Med 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mofenson LM, Vannappagari V, Scheuerle AE, et al. Periconceptional antiretroviral exposure and central nervous system (CNS) and neural tube birth defects - data from Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry (APR) 10th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science Mexico City, Mexico; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vannappagari V, Thorne C, for APR, Eppicc. Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes Following Prenatal Exposure to Dolutegravir. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019; 81(4): 371–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grayhack C, Sheth A, Kirby O, et al. Evaluating outcomes of mother-infant pairs using dolutegravir for HIV treatment during pregnancy. AIDS 2018; 32(14): 2017–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zash R, Jacobson DL, Diseko M, et al. Comparative safety of dolutegravir-based or efavirenz-based antiretroviral treatment started during pregnancy in Botswana: an observational study. Lancet Glob Health 2018; 6(7): e804–e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill A, Clayden P, Thorne C, Christie R, Zash R. Safety and pharmacokinetics of dolutegravir in HIV-positive pregnant women: a systematic review. J Virus Erad 2018; 4(2): 66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Victora CG, Aquino EM, do Carmo Leal M, Monteiro CA, Barros FC, Szwarcwald CL. Maternal and child health in Brazil: progress and challenges. Lancet 2011; 377(9780): 1863–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schomaker M, Davies MA, Cornell M, Ford N. Assessing the risk of dolutegravir for women of childbearing potential. Lancet Glob Health 2018; 6(9): e958–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasmussen SA, Barfield W, Honein MA. Protecting Mothers and Babies - A Delicate Balancing Act. N Engl J Med 2018; 379(10): 907–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Lancet HIV. A lesson to learn from dolutegravir roll-out. Lancet HIV 2019; 6(9): e559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Batista CJB, Correa RG, Evangelista LR, et al. The Brazilian experience of implementing the active pharmacovigilance of dolutegravir. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98(10): e14828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.