Abstract

This applied paper is intended to serve as a “how to” guide for public health researchers, practitioners, and policy makers who are interested in building conceptual models to convey their ideas to diverse audiences. Conceptual models can provide a visual representation of specific research questions. They also can show key components of programs, practices, and policies designed to promote health. Conceptual models may provide improved guidance for prevention and intervention efforts if they are based on frameworks that integrate social ecological and biological influences on health and incorporate health equity and social justice principles. To enhance understanding and utilization of this guide, we provide examples of conceptual models developed by the Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium. PLUS is a transdisciplinary U.S. scientific network established by the National Institutes of Health in 2015 to promote bladder health and prevent lower urinary tract symptoms, an emerging public health and prevention priority. The PLUS Research Consortium is developing conceptual models to guide its prevention research agenda. Research findings may in turn influence future public health practices and policies. This guide can assist others in framing diverse public health and prevention science issues in innovative, potentially transformative ways.

Keywords: conceptual model, conceptual framework, theory, social ecology, lower urinary tract symptoms, bladder health

Public health and prevention science students, researchers, practitioners, and policy makers all stand to benefit by becoming skilled in the development of conceptual models. Over 25 years ago, Jo Anne Earp and Susan Ennett (1991) described how a conceptual model could be used to depict the mechanisms by which a selected set of risk and protective factors may be associated with a health behavior or outcome of interest, as well as the conditions under which such associations are typically observed. This work demonstrated how conceptual models can be used to provide a visual representation of specific research questions and display the key components of prevention and intervention programs, practices, and policies designed to promote health. Since Earp and Ennett’s contribution, many publications that can be used to generate conceptual models have been introduced to the public health sphere. These writings describe frameworks that integrate social ecological and biological influences on health and highlight the potential for health equity and social justice principles to guide public health research, practice, and policy. By integrating diverse perspectives, those who design conceptual models can consider a wide range of factors that may influence health. A better understanding of what influences health can lead to the development of more effective health promotion programs, practices, and policies, as well as more efficient use of limited public health resources. Conceptual model development is an increasingly valued skill. For example, the National Institutes of Health have called for the inclusion of conceptual models when teams of researchers and practitioners respond to specific requests for proposals to conduct research on health promotion, including mental health (RFA-MH-18-705), bladder health (RFA-DK-19-015), and shared decision-making between patients and providers (PA-16-424; NIH, n.d.).

This paper is intended to serve as a contemporary guide for building conceptual models. It is consistent with the mission of Health Promotion Practice to publish practical tools that advance the science and art of health promotion and disease prevention, particularly with respect to achieving health equity, addressing social determinants of health, and advancing evidence-based health promotion practice. To enhance understanding, examples of conceptual model development are provided from the Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium, a transdisciplinary scientific network established by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in 2015 to study bladder health and prevention of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in girls and women (Harlow et al., 2018). LUTS encompass a variety of bothersome bladder symptoms, including urgency urinary incontinence (i.e., strong urge “to go” with urine loss before reaching a toilet), stress urinary incontinence (i.e., urine loss with physical activity or increases in abdominal pressure such as a cough or sneeze), bothersome frequent and/or urgent urination, nocturnal enuresis (i.e., bed-wetting), difficulty urinating, dribbling after urination, and bladder or urethral pain before, during, or after urination (Abrams et al., 2010; Haylen et al., 2010). LUTS are common. For example, more than 200 million people worldwide and over 15% of women aged 40 years or older experience urinary incontinence, one of the most prevalent LUTS (Minassian, Bazi, & Stewart, 2017; Norton & Brubaker, 2006).

While many multidisciplinary research networks focus on clinical treatment of LUTS, the PLUS Consortium stands alone in its focus on bladder health promotion and prevention of LUTS. Consistent with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of health (WHO, 2006), the PLUS Consortium conceptualizes bladder health as “a complete state of physical, mental, and social well-being related to bladder function, and not merely the absence of LUTS,” with function that “permits daily activities, adapts to short term physical or environmental stressors, and allows optimal well-being (e.g., travel; exercise; social, occupational, or other activities)” (Lukacz et al., 2018).

Conceptual models are different from other tools and concepts.

Table 1 highlights the distinction between conceptual models and closely related visual tools and concepts. The contrast between conceptual frameworks and conceptual models is of particular relevance to the present guide. A research-oriented conceptual framework encapsulates what is possible to study and is intentionally comprehensive; in contrast, a research-oriented conceptual model encapsulates what a team has prioritized and chosen to study and is intentionally focused in scope (Earp & Ennett, 1991; Brady et al., 2018). Similarly, conceptual frameworks and models may depict the “universe” and selected focus, respectively, of public health practices and policies. The contrast between a theory and conceptual model is also of particular relevance to the present guide. While both theories and conceptual models describe associations among constructs in order to explain or predict outcomes, a theory is intentionally broad with respect to application. It can guide the development of one or more conceptual models to address a specific public health behavior or outcome. While a review of prominent theories is beyond the scope of this paper, several public health textbooks provide an overview of theories that may be used to guide etiologic research and health promotion programs, practices, and policies (e.g., DiClemente, Salazar, & Crosby, 2019; Edberg, 2015; Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2015; Simons-Morton, McLeroy, & Wedndel, 2012).

Table 1.

Distinctions between conceptual models and other visual tools and concepts used in public health and related disciplines.

| Term | Definition | Applications | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Tools | |||

| Conceptual Model | Diagram of proposed causal linkages among a set of concepts believed to be related to a particular public health problem (Earp & Ennett, 1991). Depicts the mechanisms by which a selected set of risk and protective factors may be associated with a health behavior or outcome of interest, as well as the conditions under which such associations are typically observed. |

• Provide a visual representation of specific research hypotheses that will be tested • Show the key components of prevention and intervention programs, practices, and policies designed to promote health |

Earp & Ennett (1991) |

| Conceptual Framework | A group of concepts that are broadly defined and systematically organized to provide a focus, a rationale, and a tool for the integration and interpretation of information (Mosby’s Medical Dictionary, 2018). | • Provide a visual representation of what is possible to study through research or address through programs, practices, and policies • Show broad categories or domains of influence on a health behavior or outcome (e.g., social ecological models) |

Brady et al. (2018) Glass & McAtee (2006) Sallis & Owen (2015) Solar & Irwin (2010) |

| Theory | Set of interrelated concepts, definitions, and propositions that present a systematic view of events or situations by specifying relations among variables, in order to explain and predict events or situations (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2015). The notion of generality, or broad application, is important (van Ryn & Heaney, 1992). Theories are by their nature abstract; that is, they do not have a specified content or topic area (Glanz et al., 2015). | • Guide the development of a conceptual model to address a specific public health behavior or outcome • Guide research questions • Guide the content of prevention and intervention programs, practices, and policies |

Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath (2015) van Ryn & Heaney (1992) |

| Logic Model | A systematic and visual way to present and share one’s understanding of the relationships among the resources to operate a program, planned program activities, and changes or results one hopes to achieve (W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004). | • Convey the purpose of a health promotion program and expected results • Identify the resources necessary to successfully plan and implement the program |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (n.d.) W. K. Kellogg Foundation (2004) |

| Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) | A diagram depicting the statistical associations that are implied by assumptions about the casual relations between a set of variables. No cycles between variables can be depicted in the graph (Glymour, 2006). A graph is directed if only arrows connect variables. A graph is acyclic if no directed path (sequence of single-headed arrows) in the graph forms a closed loop (Greenland, Pearl, & Robins, 1999). |

• Depict the variables that will be included in a statistical test, as well as the hypothesized role of those variables (e.g., predictor, confounder, outcome) |

Glymour (2006) Greenland, Pearl, & Robins (1999) |

| Systems Model | Relates different types of structures, including biological, organizational, and political systems (Leischow & Milstein, 2006). A paradigm or perspective that considers connections among different components, plans for the implications of their interaction, and requires transdisciplinary thinking as well as active engagement of those who have a stake in the outcome to govern the course of change (Leischow & Milstein, 2006). |

• Describe and model complex systems, including causal linkages and feedback loops • Understand health as a system of structured relationships that can be governed in dynamic and democratic contexts (Leischow & Milstein, 2006) • Support the development of strategies to intervene in complex systems (Foresight, Vandenbroeck, Goossens, & Clemens, 2007) |

Foresight, Vandenbroeck, Goossens, & Clemens (2007) Joffe & Mindell (2006) Leischow & Milstein (2006) |

| Related Concepts | |||

| Construct | The major components, building blocks, or primary elements of a theory (Glanz et al., 2015). | • Identify a core set of concepts thought to explain a health behavior or outcome • Identify a core set of features or mechanisms thought to explain the health promoting effects of a program, practice, or policy |

Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath (2015) |

| Variable | The empirical counterpart or operational form of a construct; how a construct will be measured in a specific situation (Glanz et al., 2015). | • Identify or develop measures to test associations between key constructs • Identify or develop measures to evaluate a health promotion program, practice, or policy |

Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath (2015) |

| Risk and Protective Factors | Potential precursors to human dysfunction and health, respectively. Protective factors improve resistance to risk factors (i.e., effect modification) (Coie et al., 1993). More recently, protective factors have been termed “promoting factors” when they exert direct, positive effects on health (Kia-Keating, Dowdy, Morgan, & Noam, 2011). |

• Identify illness-promoting and health-promoting characteristics of individuals and their social ecology • Identify possible mechanisms of resilience in adverse social ecological contexts |

Coie et al. (1993) Kia-Keating et al. (2011) |

| Mediating Variable | An intervening, explanatory variable or process between a predictor variable and an outcome (Earp & Ennett, 1991; Baron & Kenny, 1986). | • Identify mechanisms by which selected risk and protective factors may become associated with a health behavior or outcome • Identify mechanisms of action by which a program, practice, or policy may favorably impact a health behavior or outcome |

Baron & Kenny (1986) Earp & Ennett (1991) Fairchild & MacKinnon (2009) |

| Moderating Variable / Effect Modification | A variable thought to modify the relationship between two variables (Earp & Ennett, 1991; Baron & Kenny, 1986). | • Specify the conditions under which two variables are related to one another • Specify the groups for whom a program, practice, or policy is most beneficial |

Baron & Kenny (1986) Earp & Ennett (1991) Fairchild & MacKinnon (2009) |

| Confounder | A variable that may influence both the hypothesized predictor and outcome variable, resulting in a spurious (false) association (Earp & Ennett, 1991; Greenland, Pearl, & Robins, 1999). | • Identify, measure, and statistically adjust for potential confounders in analyses to better isolate the contribution of hypothesized risk and protective factors |

Earp & Ennett (1991) Greenland, Pearl, & Robins (1999) |

Traditional and contemporary conceptualizations of public health can identify a broad range of factors that may function as determinants of health.

Traditional conceptual frameworks include social ecological and biopsychosocial models. Social ecological models, a foundation of public health approaches for more than 40 years (McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988; Sallis & Owen, 2015; Richard, Gauvin, & Raine, 2011), situate individuals within an ecosystem of risk and protective factors that extend outward from the intrapersonal level (e.g., biology, psychology) through the interpersonal (e.g., family, peers, partner), institutional (e.g., school, workplace, health clinic), community (e.g., cultural norms), and societal (e.g., policies, laws, economics) levels. These nested spheres of influence interact to produce individual and population health. Similarly, the biopsychosocial model posits that health is defined by a complex reciprocal interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors (Engel, 1981). Given the focus of this paper, we note that both social ecological and biopsychosocial models are more consistent with the definition of a conceptual framework than a conceptual model (see Table 1).

Contemporary conceptualizations of public health enhance traditional frameworks by more explicitly integrating biology and social ecology, adopting life course perspectives, and incorporating health equity, social justice, and community engagement principles to guide research, practice, and policy. The Society-Behavior-Biology Nexus depicts nested spheres of influences both within and outside of an individual, who moves through life stages from infancy to old age (Glass & McAtee, 2006). Systems of biological organization include multi-organ systems, cellular and molecular influences, and the genomic substrate. Levels of ecology include the micro (e.g., family, social networks), mezzo (e.g., schools, worksites, communities, healthcare systems), macro (e.g., states, nations), and global (e.g., geopolitics, environment). Biology and social ecology are integrated through the multi-level concept of embodiment (e.g., gene-environment interactions; impact of varying social-ecological resources on biology within and across populations) (Glass & McAtee, 2006; Krieger, 2005). Social determinants are framed as societal constraints against and opportunities for health – risk regulators – which include material conditions; discriminatory practices, policies, and attitudes; neighborhood and community conditions; behavioral norms, rules, and expectations; conditions of work; and laws, policies, and regulations. Risk regulators can impact behavior or become embodied with respect to biological function (Glass & McAtee, 2006; Krieger, 2005).

The WHO Conceptual Framework for Action on Social Determinants of Health describes how the structure of societies (i.e., governance, policies, values) determines population health (Solar & Irwin, 2010). Social stratification by race, ethnicity, sex, gender, social class, and other factors leads to social hierarchies, which in turn shape social determinants of health. Distal structural determinants of health inequities (e.g., public policy, macroeconomics) are distinguished from more proximal social determinants of health (e.g., living and working conditions). The WHO framework asserts that societies produce health and disease, obligating policy makers to promote health equity and redress structural factors that produce under-resourced communities. Without such attention, health inequities evolve, often widening over time and across generations. The WHO framework can inform conceptual model development by encouraging the consideration of determinants at distal, structural levels (e.g., national policies).

Research teams have utilized contemporary conceptualizations of public health to promote health equity and social justice (Warnecke et al., 2008; Balazs & Ray, 2014). For example, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) sponsored Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities developed a framework to show how distal factors (population-level policies and social conditions, institutional contexts) influence intermediate social context (e.g., collective efficacy, social capital), social relationships (e.g., networks, support, and influence), and physical context (e.g., building quality, neighborhood stability), which in turn influence factors that are more proximal to health (individual demographics and risk behaviors, biologic responses and pathways) (Warnecke et al., 2008). The Energy and Resources Group at the University of California, Berkeley developed a framework to display mechanisms through which natural, built, and sociopolitical factors, along with state, county, and community actors, can create drinking water disparities (Balazs & Ray, 2014). These frameworks highlight the key role of distal structural factors in both generating health inequities and remedying them.

Community partners can aid in developing conceptual models.

Increasingly, teams are incorporating community-engaged approaches in the development of research, practice, and policy (e.g., community members actively contributing to problem definition, agenda setting, implementation, and dissemination) (Warnecke et al., 2008; O’Mara-Eves et al., 2013). Different resources exist to guide community engagement and enhance the likelihood of sustained, relevant action. For example, Lezine and Reed (2007) outlined different steps to build and apply political will in the development and implementation of public health policy; their approach integrates scientific evidence and community participation. Cacari-Stone and colleagues (2014) developed a conceptual model to show how community-based participatory research (CBPR), one approach to community engagement, can lead to policy change.

Three Steps of Conceptual Model Development.

The development of conceptual models can be divided into three basic steps: (1) identify resources for idea generation; (2) consider risk and protective factors; and (3) select factors for inclusion in the conceptual model. First, team members identify existing conceptual frameworks and models, theories, and key stakeholders (e.g., practitioners, policy makers, community members) that will serve as resources for idea generation. This step defines the “universe” of factors that can be studied in relation to specific health behaviors or outcomes of interest. Second, team members systematically consider risk and protective factors suggested by resources. This step highlights the importance of carefully selecting resources for idea generation; the risk and protective factors considered by a team will be constrained by its selected frameworks and models, theories, and stakeholders. Existing evidence linking risk and protective factors to the health behaviors or outcomes under study, as well as potential effect modifiers and confounders, can be identified through literature reviews. When data are insufficient, a team may wish to conduct key stakeholder interviews, focus groups, and other forms of hypothesis-generating data collection. The third step in the development of conceptual models is to narrow down considered risk and protective factors to those that will be included in the conceptual model. This can be achieved through a combination of theoretically-based, key stakeholder-based, and evidence-based rationales. Theories point to clusters of risk and protective factors that could be studied in relation to health behaviors or outcomes of interest, or targeted through prevention or intervention efforts. Key stakeholders can assess the relevance of different theories to a given public health context and suggest additional risk and protective factors that seem critical to the context. Findings from the extant literature can provide evidence in support of different links in the conceptual model.

If the intent of building a conceptual model is to develop an evidence-based program, practice, or policy, a team can conduct a literature review to answer the following “narrowing down” questions: (a) Is the risk or protective factor strongly linked to the health behavior or outcome of interest? (b) Have previous prevention or intervention programs, practices, or policies shown that the risk or protective factor is feasible to modify? (c) Was health improved as a result of modifying the risk or protective factor? Risk and protective factors can be retained in the conceptual model if they are strongly supported by evidence and judged highly relevant to context.

When the intent of building a conceptual model is to conduct research to better understand a health behavior or outcome, a team may choose to consult existing theories, key stakeholders, and the evidence-base for guidance in selecting risk and protective factors. To maximize potential public health impact, a team can answer the following “narrowing down” question: What potential risk and protective factors are judged to be highly likely to influence health behaviors or outcomes of interest? Ideally, the answers to public health research questions will expand the evidence base in a way that can directly inform programs, practices, and policies. Expansion of the evidence-base can be accomplished in a variety of potentially transformative ways, including the synthesis of ideas from more than one discipline and the application of paradigms from one discipline to another.

Regardless of the approach and rationale used to select risk and protective factors, the utility of the conceptual model may be enhanced by answering the final three sets of questions: (a) Have key “mechanistic factors” been considered and included in the model? What biological, psychological, and social processes might explain links between identified risk and protective factors and health behaviors or outcomes of interest? (b) Have key “upstream factors” been considered and included in the model? For example, are there societal and institutional policies and practices that serve as facilitators or barriers to health? (c) Have key “effect modifiers” been considered and included in the model? For example, are there factors that might make prevention or intervention programs, practices, or policies more or less effective among specific communities and populations?

Examples from the PLUS Research Consortium.

The PLUS Consortium is comprised of a transdisciplinary network of professionals, including community advocates, health care professionals, and scientists specializing in pediatrics, adolescent medicine, gerontology and geriatrics, nursing, midwifery, behavioral medicine, preventive medicine, psychiatry, neuroendocrinology, reproductive medicine, female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery, urology, infectious diseases, clinical and social epidemiology, prevention science, medical sociology, psychology, women’s studies, sexual and gender minority health, community-engaged research, community health promotion, scale development, research methods, and biostatistics. The PLUS Consortium has developed several conceptual models to guide research questions that will test whether specific risk and protective factors contribute to LUTS and bladder health.

Because the evidence-base for LUTS prevention is sparse, the traditional and contemporary conceptualizations of public health reviewed above, as well as expertise of PLUS investigators, were used as key resources to identify potential risk and protective factors for study (Step 1). Traditional and contemporary conceptualizations of public health encouraged consortium members to step outside of their disciplinary “comfort zones” to integrate social ecological and biological influences on health across the life course and consider the potential for health equity and social justice principles to guide the consortium’s prevention research agenda. While all of the conceptualizations reviewed above were considered, Glass and McAtee’s Society-Behavior-Biology Nexus was particularly influential because it visually represented different levels of social ecology and biology across the life course, as well as the process of embodiment. PLUS members served as an initial key stakeholder group that generated a conceptual framework and over 400 risk and protective factors prioritized for study in relation to bladder health and LUTS (Step 2) (Brady et al., 2018). The conceptual models presented in this paper represent the work of subsets of consortium members who designed models to guide specific research questions (Step 3). Models were designed with the assistance of public health and prevention science team members who were familiar with social ecological frameworks and the development of conceptual models. Initial development of models occurred in real time during in-person and virtual (WebEx) meetings. This was often followed by revision of models via emailed chains of conversation. One person with experience in conceptual model development was responsible for integrating and communicating comments and mutual decisions, as well as revising the models.

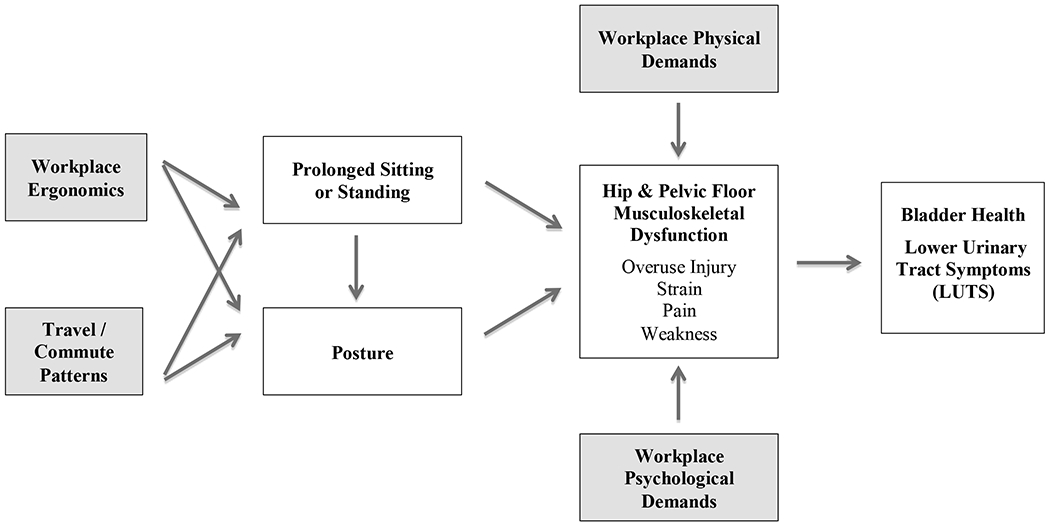

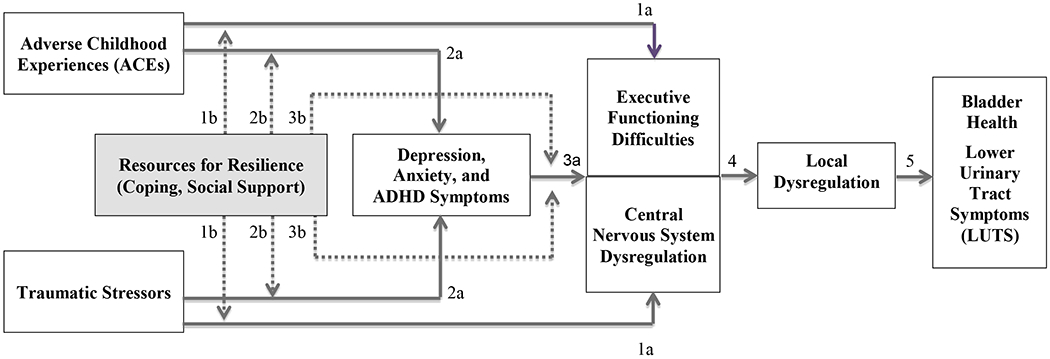

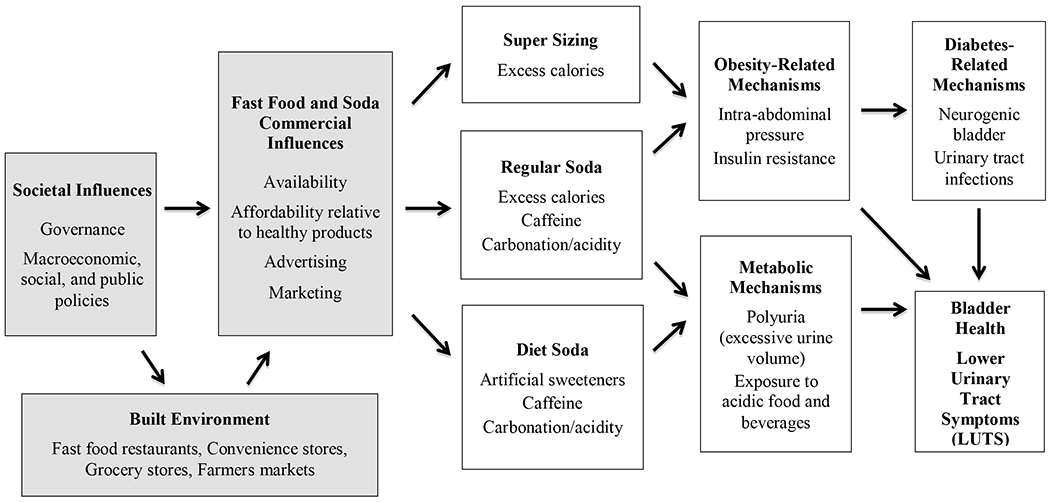

Each conceptual model featured in this paper represents hypothesized associations between constructs; some links in each model are supported by existing evidence, while others are based on theoretical or biological plausibility. Figure 1 highlights institutional-level factors in relation to bladder health and LUTS, while Figure 2 highlights family- and community-level factors and Figure 3 highlights societal and commercial factors.

Figure 1.

Work-related structural and social influences on musculoskeletal function and bladder health: Hypothesized mechanisms.

Explanation of Pathways: Four different work-related factors (shaded boxes) affect different aspects of musculoskeletal function, which in turn affect bladder health and LUTS. Workplace physical and psychological demands directly affect musculoskeletal function. Workplace ergonomics and travel/commute patterns indirectly affect musculoskeletal function through prolonged sitting or standing and posture (mediation pathways).

Figure 2.

Trajectories of risk and resilience among individuals and communities exposed to ACEs and traumatic stressors: Hypothesized mechanisms.

Explanation of Pathways: Executive functioning difficulties and central nervous system dysregulation are shown in a single, partitioned box because these constructs are hypothesized to covary in their manifestation. Direct effects between two adjacent constructs are shown by solid lines (1a, 2a, 3a, 4, 5); effect modification by resources for resilience (shaded box) is shown by dashed lines (1b, 2b, 3b). ADHD: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder.

Figure 3.

Societal and commercial influences on bladder health and LUTS: Hypothesized mechanisms involving fast food and soda.

Explanation of Pathways: This conceptual model highlights hypothesized mechanisms (mediators) that can explain associations between societal and commercial factors (shaded boxes) and bladder health and LUTS. This model can guide a set of statistical analyses that require the identification of predictor, mediating, and outcome variables. The model does not reflect the full complexity of associations that likely exist among constructs (e.g., bi-directional associations, feedback loops; see Systems Model entry in Table 1).

Figure 1 depicts a basic conceptual model showing how specific work-related structural and social factors may influence musculoskeletal function, which in turn may impact bladder health and LUTS development. Four key aspects of musculoskeletal dysfunction are overuse injury, strain, pain, and weakness (see center-right of Figure 1), which may be directly and indirectly influenced by work-related factors. The top, bottom, and left-most boxes depict work-related factors that are external to the individual and arguably imposed by society and institutions. Workplace physical and psychological demands are shown to directly impact musculoskeletal function. Workplace physical demands (e.g., repetitive heavy lifting) may result in musculoskeletal dysfunction, which in turn may lead to LUTS (Park & Palmer, 2015). In addition, workplace psychological demands (e.g., job performance pressures, conflict with coworkers, inequitable expectations and evaluations of work) may be accompanied by stress, anxiety, and other forms of negative affect (Larsman, Kadefors, & Sandsjö, 2013), which may lead to chronically increased pelvic floor muscle dysfunction and LUTS (van der Velde, Laan, & Everaerd, 2001). Workplace ergonomics (e.g., improper chair or desk height) and travel/commute patterns (e.g., daily, long commutes and long airplane flights) may indirectly impact musculoskeletal dysfunction through prolonged sitting or standing and poor posture (Barone Gibbs et al., 2018).

Additional research is needed to support hypothesized associations in Figure 1, which are based in large part on the authors’ clinical and community-based observations. If different links are supported, corresponding workplace policies and practices can be promoted to ensure that physical demands are offset by varying the type and intensity of activity and providing breaks; psychological demands are fair, reasonable, and offset by supports; and workplace ergonomics are conducive to the health of all employees, regardless of status within the organization. In addition, local and state governments can support policies and practices that ensure adequate access to acceptable bathroom facilities along transportation routes and when possible, within public transportation conveyances.

Figure 2 shows an example of a more complex conceptual model. A trajectory of risk among individuals or communities exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (e.g., abuse, neglect, household disruptions) (Felitti et al., 1998) and other traumatic stressors can be seen by following the solid lines from left to right. ACEs and traumatic stressors indirectly affect local dysregulation through two potential pathways: (I) development of executive functioning difficulties and central nervous system dysregulation (shown by 1a links) (Nusslock & Miller, 2016; Smith et al., 2016), which in turn lead to local dysregulation (shown by link 4) (Kanter et al., 2016); and (II) development of depression, anxiety, and ADHD symptoms (shown by 2a links), which in turn lead to executive functioning difficulties and central nervous system dysregulation (shown by link 3a) (Nusslock & Miller, 2016), which then leads to local dysregulation (shown by link 4) (Kanter et al., 2016; Yousefichaijan, Sharafkhah, Rafiei, & Salehi, 2016). Constructs that explain associations between stressful life circumstances and LUTS may collectively be thought of as a “chain of mediation,” in that they lie along a hypothesized causal, sequential pathway. Figure 2 also shows how a trajectory of risk/chain of mediation may be weakened or broken at different points along the pathway. The dashed lines of Figure 2 show modification of effects (“effect modification”) by resources for resilience (i.e., coping, social support). Effects of stressful life circumstances on LUTS are weakened in the presence of resources for resilience (shown by the dashed lines 1b, 2b, and 3b).

Although several of the links in Figure 2 are supported by evidence, additional research is needed. Figure 2 illustrates the importance of structural factors that stratify the citizens of a society into communities that are more or less likely to experience adverse childhood experiences and traumatic stressors, and have more or less opportunities to garner resources for resilience (Glass & McAtee, 2006; Solar & Irwin, 2010; Warnecke et al., 2008). Policies attempting to ensure equitable allocation of resources, including but not limited to health care, are essential to preventing and weakening trajectories of risk that disproportionately impact under-resourced communities and families.

Figure 3, our final example, highlights broader, societal and commercial influences on bladder health and LUTS, along with environmental, behavioral, and biological mechanisms specific to fast food and soda consumption. Consistent with the WHO Conceptual Framework for Action on Social Determinants of Health (Solar & Irwin, 2010), Figure 3 begins with societal structures. Governance and policies shape the built environments of communities, in part through zoning of fast food restaurants, convenience stores, grocery stores, and farmers markets; these, in turn, impact the availability of fast food and soda in communities (Sallis & Glanz, 2009). Additional policies can impact the affordability of fast food and soda relative to healthy products (e.g., taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages; subsidies for fresh produce) (Franck, Grandi, & Eisenberg, 2013), as well as the advertising and marketing of fast food and beverages, especially towards children (Harris et al., 2015). Low-income communities of color in the United States have historically received fewer resources as a result of inequitable policies; they have also been targeted by the fast food and soda industries (Sallis & Glanz, 2009; Harris et al., 2015).

Availability, relative affordability, advertising, and marketing of fast food and soda within a community increase the likelihood that residents will consume “super-sized” food portions and soda, which contributes to obesity (Sallis & Glanz, 2009; Harris et al., 2015). Obesity may directly impact LUTS by intra-abdominal pressure on the bladder (Bavendam et al., 2016); it may also impact LUTS through diabetes-related mechanisms, including neurogenic bladder and urinary tract infections (Bavendam et al., 2016; Podnar & Vodusek, 2015). Diet soda, which many individuals embrace as a means to reduce caloric intake and combat obesity, contains components that may increase urine volume (caffeine) and harm the health of the bladder lining (artificial sweeteners, carbonation/acidity) (Robinson, Hanna-Mitchell, Rantell, Thiagamoorthy, & Cardozo, 2015). A healthy bladder may be maintained or restored by healthy food and beverage choices; Figure 3 highlights constraints on healthy choices that are determined by upstream, societal factors.

Because the PLUS Research Consortium is just beginning its prevention research agenda, its current models are intended to guide etiologic research, as opposed to selection, implementation, and evaluation of health promotion and prevention strategies. Broader planning frameworks exist for this purpose, including PRECEDE-PROCEED and intervention mapping (Bartholomew, Markham, Mullen, & Fernández, 2015; Bartholomew, Parcel, & Kok, 1998; Green & Kreuter, 2005), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) Strategic Prevention Framework (2017), and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Framework for Program Evaluation in Public Health (1999). These frameworks not only guide practitioners in assessing risk and protective factors at different levels of social ecology that may influence health, but also provide a structure for applying theories and conceptual models to the planning and evaluation of health promotion programs, practices, and policies. The PLUS Research Consortium will utilize existing planning frameworks when its work progresses to the point of designing, implementing, and evaluating bladder health promotion and LUTS prevention strategies through research.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Other Conceptual Model Development Teams.

After developing the conceptual models and supporting materials presented in this paper, authors reflected on lessons they had learned and what they would recommend to other teams.

Recommendation 1: Develop a shared language.

Students, researchers, practitioners, and policy makers interested in developing conceptual models may benefit from reviewing the terms in Table 1, determining what is consistent with and distinct from their own discipline and training, and identifying additional tools and concepts that could aid in conceptual model development. Few of this paper’s authors were initially familiar with all of the visual tools and related concepts defined in Table 1. Terms were added not only by authors, but also by other PLUS Consortium members (e.g., epidemiologists recommended the inclusion of “directed acyclic graph” and “systems model”). Teams who are developing conceptual models may develop a shared language through the process of reviewing, adding, and defining terms.

Recommendation 2: Establish a conceptual framework before developing a conceptual model.

Authors appreciated the distinction between conceptual frameworks and models, particularly with respect to how a framework could be a starting point to broaden one’s conceptualization of health beyond one’s own disciplinary training. Consortium members valued the integration of social ecological, behavioral, and biological perspectives of what influences health, as well as the opportunity to incorporate multiple levels of influence into a single conceptual model and corresponding set of research questions. Consortium members appreciated how the creation and refinement of conceptual models could then assist in clarifying specific research questions; identifying potential pathways through which different risk and protective factors may influence a health outcome; examining and challenging one’s own disciplinary assumptions; and articulating what is known or speculative with respect to the factors that influence health.

Recommendation 3: Seek to develop a diverse team and solicit input from others.

Authors appreciated how steps of conceptual model development included the consideration of how community partners and other key stakeholders can become involved in the process of development. By design, the PLUS Research Consortium includes community advocates, community-engaged researchers, and health care professionals and scientists representing a broad array of disciplines. Authors did not reach beyond the PLUS Consortium to develop the conceptual models featured in this paper, in part because the present paper was intended to describe the process of conceptual model development, rather than to present definitive models. Other conceptual model development teams may benefit from soliciting the input of individuals who are not well represented on their team, including community members, researchers, practitioners, and policy makers.

Recommendation 4: Anticipate and embrace the iterative, “trial and error” nature of conceptual model development.

Early in the process of developing conceptual models, authors developed a shared understanding that it was not necessary for all proposed links in a conceptual model to be informed by existing evidence. Theory, clinical observations, and the lived experience of community members are valid sources of information, as well. Authors also came to appreciate that it was not necessary to develop the “perfect” model during a first attempt to understand a health behavior or outcome, or to select the key components of an evidence-based program, practice, or policy. Indeed, attempting to achieve perfection may stifle creativity and innovation. The conceptual models presented in this paper were developed iteratively, both within the team of authors and consortium members who assisted in their development (see Acknowledgements). Conceptual models should be evaluated through research, which may support or fail to support proposed links in a model. Conceptual models are meant to be refined, not only during their initial stage of development, but also in response to new information that is gleaned through subsequent research.

Summary and Conclusion.

Researchers, practitioners, and policy makers can use conceptual models to convey ideas to diverse audiences. We posit that conceptual models may have the greatest impact on public health if they integrate social ecological and biological influences on health and highlight the potential for health equity and social justice principles to guide public health research, practice, and policy. To illustrate this point, we have provided examples of conceptual model development from the Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium, a transdisciplinary scientific network established in the United States in 2015 to promote bladder health and prevent lower urinary tract symptoms, an emerging public health and prevention priority. The PLUS Consortium is developing conceptual models to guide its bladder health promotion and LUTS prevention research agenda. In concert with other researchers and community partners, the PLUS Consortium will be poised to inform future public health practices and policies. We hope our shared work will assist others in framing diverse public health matters in innovative, potentially transformative ways.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge special contributions to featured conceptual models by the following PLUS Research Consortium members: Amanda Berry, Neill Epperson, Colleen Fitzgerald, Missy Lavender, Ariana Smith, and Beverly Williams. The authors also acknowledge the foundational work of Jo Anne Earp, Professor Emerita, and Susan T. Ennett, Professor, Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Earp and Dr. Ennett’s pioneering “how to” guide for building conceptual models, published in 1991, inspired the present guide. In addition, the authors acknowledge Kenneth L. McLeroy, Professor Emeritus and retired Regents and Distinguished Professor, School of Public Health, Texas A&M University, for helpful discussion about manuscript content.

Participating PLUS research centers at the time of this writing are as follows:

Loyola University Chicago - 2160 S. 1st Avenue, Maywood, Il 60153-3328

Linda Brubaker, MD, MS, Multi-PI; Elizabeth Mueller, MD, MSME, Multi-PI; Colleen M. Fitzgerald, MD, MS, Investigator; Cecilia T. Hardacker, RN, MSN, Investigator; Jeni Hebert-Beirne, PhD, MPH, Investigator; Missy Lavender, MBA, Investigator; David A. Shoham, PhD, Investigator

University of Alabama at Birmingham - 1720 2nd Ave South, Birmingham, AL 35294

Kathryn Burgio, PhD, PI; Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH, Investigator; Alayne Markland, DO, MSc, Investigator; Gerald McGwin, PhD, Investigator; Beverly Williams, PhD, Investigator

University of California San Diego - 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92093-0021

Emily S. Lukacz, MD, PI; Sheila Gahagan, MD, MPH, Investigator; D. Yvette LaCoursiere, MD, MPH, Investigator; Jesse N. Nodora, DrPH, Investigator

University of Michigan - 500 S. State Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109

Janis M. Miller, PhD, MSN, PI; Lawrence Chin-I An, MD, Investigator; Lisa Kane Low, PhD, MS, CNM, Investigator

University of Pennsylvania – Urology, 3rd FL West, Perelman Bldg, 34th & Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA 19104

Diane Kaschak Newman, DNP, ANP-BC, FAAN PI; Amanda Berry, PhD, CRNP, Investigator; C. Neill Epperson, MD, Investigator; Kathryn H. Schmitz, PhD, MPH, FACSM, FTOS, Investigator; Ariana L. Smith, MD, Investigator; Ann Stapleton, MD, FIDSA, FACP, Investigator; Jean Wyman, PhD, RN, FAAN, Investigator

Washington University in St. Louis - One Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63130

Siobhan Sutcliffe, PhD, PI; Colleen McNicholas, DO, MSc, Investigator; Aimee James, PhD, MPH, Investigator; Jerry Lowder, MD, MSc, Investigator;

Yale University - PO Box 208058 New Haven, CT 06520-8058

Leslie Rickey, MD, PI; Deepa Camenga, MD, MHS, Investigator; Shayna D. Cunningham, PhD, Investigator; Toby Chai, MD, Investigator; Jessica B. Lewis, PhD, MFT, Investigator

Steering Committee Chair: Mary H. Palmer, PhD, RN: University of North Carolina

NIH Program Office: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Division of Kidney, Urologic, and Hematologic Diseases, Bethesda, MD

NIH Project Scientist: Tamara Bavendam MD, MS; Project Officer: Ziya Kirkali, MD; Scientific Advisors: Chris Mullins, PhD and Jenna Norton, MPH; Scientific and Data Coordinating Center (SDCC): University of Minnesota - 3 Morrill Hall, 100 Church St. S.E., Minneapolis MN 55455

Bernard Harlow, PhD, Multi-PI; Kyle Rudser, PhD, Multi-PI; Sonya S. Brady, PhD, Investigator; John Connett, PhD, Investigator; Haitao Chu, MD, PhD, Investigator; Cynthia Fok, MD, MPH, Investigator; Todd Rockwood, PhD, Investigator; Melissa Constantine, PhD, MPAff, Investigator

Funding

This work of the Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through cooperative agreements (grant numbers U01DK106786, U01DK106853, U01DK106858, U01DK106898, U01DK106893, U01DK106827, U01DK106908, U01DK106892). Additional support was provided by the National Institute on Aging, NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, and NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

Contributor Information

Sonya S. Brady, Division of Epidemiology & Community Health, University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, MN, 55454, USA.

Linda Brubaker, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California, 92037, USA.

Cynthia S. Fok, Department of Urology, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN, 55454, USA.

Sheila Gahagan, Division of Academic General Pediatrics, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA, 92093, USA.

Cora E. Lewis, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, 35294, USA.

Jessica Lewis, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT, 06520, USA.

Jerry L. Lowder, Division of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, 63110, USA

Jesse Nodora, Department of Family Medicine and Public Health and Moores UC San Diego Cancer Center, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, 92161, USA.

Ann Stapleton, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 98195, USA.

Mary H. Palmer, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, 27599, USA.

References

- Abrams P, Andersson KE, Birder L, Brubaker L, Cardozo L, Chapple C, … & Wyndaele JJ (2010). Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: Evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence. Neurourology and Urodynamics: Official Journal of the International Continence Society, 29(1), 213–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazs CL, & Ray I (2014). The drinking water disparities framework: On the origins and persistence of inequities in exposure. American Journal of Public Health, 104(4), 603–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew LK, ., Markham C, Mullen P, & Fernández ME. (2015). Planning models for theory-based health promotion interventions In Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Viswanath K. (Eds.) Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice (5th ed., pp. 359–387). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, & Kok G (1998). Intervention mapping: A process for developing theory- and evidence-based health education programs. Health Education & Behavior, 25 (5), 545–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavendam TG, Norton JM, Kirkali Z, Mullins C, Kusek JW, Star RA, & Rodgers GP (2016). Advancing a comprehensive approach to the study of lower urinary tract symptoms. The Journal of Urology, 196(5), 1342–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady SS, Bavendam TG, Berry A, Fok CS, Gahagan S, Goode PS, … & Lukacz ES. (2018). The Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) in girls and women: Developing a conceptual framework for a prevention research agenda. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 37(8), 2951–2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacari-Stone L, Wallerstein N, Garcia AP, & Minkler M (2014). The promise of community-based participatory research for health equity: a conceptual model for bridging evidence with policy. American Journal of Public Health, 104(9), 1615–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2004). Evaluation guide: Developing and using a logic model. Atlanta, GA: Division of Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999). Framework for program evaluation in public health. MMWR, 48 (No. RR-11). Retrieved June 2, 2019 from https://www.cdc.gov/eval/framework/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Watt NF, West SG, Hawkins JD, Asarnow JR, Markman HJ, … & Long B (1993). The science of prevention: A conceptual framework and some directions for a national research program. American Psychologist, 48(10), 1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Definition of conceptual framework. Mosby’s Medical Dictionary, 8th edition The Free Dictionary by Farlex; Retrieved January 31, 2018 from https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/conceptual+framework Accessed [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, & Crosby RA (2019). Health Behavior Theory for Public Health: Principles, Foundations, and Applications (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Earp JA, & Ennett ST (1991). Conceptual models for health education research and practice. Health Education Research, 6(2), 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edberg M (2015). Essentials of Health Behavior: Social and Behavioral Theory in Public Health (2nd ed.). In Riegelman R (Series Ed.), Essential Public Health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL (1981, January). The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. In The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy: A Forum for Bioethics and Philosophy of Medicine, 6(2), 101–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AJ, & MacKinnon DP (2009). A general model for testing mediation and moderation effects. Prevention Science, 10(2), 87–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck C, Grandi SM, & Eisenberg MJ (2013). Taxing junk food to counter obesity. American Journal of Public Health, 103(11), 1949–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs BB, Hergenroeder AL, Perdomo SJ, Kowalsky RJ, Delitto A, & Jakicic JM (2018). Reducing sedentary behaviour to decrease chronic low back pain: the stand back randomised trial. Occup Environ Med, 75(5), 321–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Viswanath K (Eds.). (2015). Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice (5th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Viswanath K (2015). Theory, research, and practice in health behavior In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Viswanath K. (Eds.). Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice. 5th ed. (pp. 23–41). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, & McAtee MJ (2006). Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envisioning the future. Social Science & Medicine, 62(7), 1650–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour MM (2006). Using causal diagrams to understand common problems in social epidemiology In Oakes JM & Kaufman JS (Eds.), Methods in social epidemiology (1st ed., pp. 393–428). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Green LW. , & Kreuter MW. (2005). Health program planning: An educational and ecological approach (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, Pearl J, & Robins JM (1999). Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology, 37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman R, Swift S, Berghmans B, & Lee J (2010). An International Urogynecology Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn, 29, 4–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow BL, Bavendam TG, Palmer MH, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, Lukacz ES, … & Simons-Morton D. (2018). The prevention of lower urinary tract symptoms (PLUS) research consortium: A transdisciplinary approach toward promoting bladder health and preventing lower urinary tract symptoms in women across the life course. Journal of Women’s Health, 27(3), 283–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JL, Shehan C, Gross R, Kumanyika S, Lassiter V, Ramirez AG, & Gallion K (2015). Food advertising targeted to Hispanic and Black youth: Contributing to health disparities. Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity. [Google Scholar]

- Joffe M, & Mindell J (2006). Complex causal process diagrams for analyzing the health impacts of policy interventions. American Journal of Public Health, 96(3), 473–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LM, Matteson CL, & Finegood DT (2014). Systems science and obesity policy: a novel framework for analyzing and rethinking population-level planning. American Journal of Public Health, 104(7), 1270–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanter G, Komesu YM, Qaedan F, Jeppson PC, Dunivan GC, Cichowski SB, & Rogers RG (2016). Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a novel treatment for interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. International Urogynecology Journal, 27(11), 1705–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kia-Keating M, Dowdy E, Morgan ML, & Noam GG (2011). Protecting and promoting: An integrative conceptual model for healthy development of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(3), 220–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N (2005). Embodiment: a conceptual glossary for epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(5), 350–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsman P, Kadefors R, & Sandsjö L (2013). Psychosocial work conditions, perceived stress, perceived muscular tension, and neck/shoulder symptoms among medical secretaries. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 86(1), 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leischow SJ, & Milstein B (2006). Systems thinking and modeling for public health practice. American Journal of Public Health, 96(3) 403–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezine DA, & Reed GA (2007). Political will: a bridge between public health knowledge and action. American Journal of Public Health, 97(11), 2010–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacz ES, Bavendam TG, Berry A, Fok CS, Gahagan S, Goode PS, … & Brady SS. (2018). Defining bladder health in women and girls: Implications for research, clinical practice, and public health promotion. Journal of Women’s Health, 27(8) 974–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, & Glanz K (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minassian VA, Bazi T, & Stewart WF (2017). Clinical epidemiological insights into urinary incontinence. International Urogynecology Journal, 28(5), 687–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health (n.d.). Find Funding: NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts. Retrieved September 10, 2019 from https://grants.nih.gov/funding/searchguide/index.html#/

- Norton P, & Brubaker L (2006). Urinary incontinence in women. The Lancet, 367(9504), 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslock R, & Miller GE (2016). Early-life adversity and physical and emotional health across the lifespan: A neuroimmune network hypothesis. Biological Psychiatry, 80(1), 23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, McDaid G, Oliver S, Kavanagh J, Jamal F, … & Thomas J. (2013). Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: a systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Public Health Research, 1(4). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, & Palmer MH (2015). Factors associated with incomplete bladder emptying in older women with overactive bladder symptoms. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(7), 1426–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podnar S, & Vodušek DB (2015). Lower urinary tract dysfunction in patients with peripheral nervous system lesions. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 130, 203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard L, Gauvin L, & Raine K (2011). Ecological models revisited: their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D, Hanna-Mitchell A, Rantell A, Thiagamoorthy G, & Cardozo L (2017). Are we justified in suggesting change to caffeine, alcohol, and carbonated drink intake in lower urinary tract disease? Report from the ICI-RS 2015. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 36(4), 876–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, & Glanz K (2009). Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. The Milbank Quarterly, 87(1), 123–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Owen N. Ecological models of health behavior In Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice. 5th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2015: 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, McLeroy KR, & Wedndel ML (2012). Behavior Theory in Health Promotion Practice and Research. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Smith AL, Hantsoo L, Malykhina AP, File DW, Valentino R, Wein AJ, … &Epperson CN (2016). Basal and stress-activated hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis function in postmenopausal women with overactive bladder. International Urogynecology Journal, 27(9), 1383–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solar O, & Irwin A A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). 2010. [02/08/2015] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2017). Strategic Prevention Framework. Retrieved June 2, 2019 from https://www.gaspsdata.net/sites/default/files/spf_brochure_1.12.17_approved.pdf

- Van der Velde J, Laan E, & Everaerd W (2001). Vaginismus, a component of a general defensive reaction. An investigation of pelvic floor muscle activity during exposure to emotion-inducing film excerpts in women with and without vaginismus. International Urogynecology Journal, 12(5), 328–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryn M, & Heaney CA (1992). What’s the use of theory? Health Education Quarterly, 19(3), 315–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroeck P, Goossens J & Clemens M (2007). Foresight, Tackling Obesities: Future Choices – Obesity System Atlas. Retrieved June 2, 2019 from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/295153/07-1177-obesity-system-atlas.pdf

- Warnecke RB, Oh A, Breen N, Gehlert S, Paskett E, Tucker KL, … & Hiatt RA. (2008). Approaching health disparities from a population perspective: the National Institutes of Health Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 98(9), 1608–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- W. K. Kellogg Foundation. (2004). Using logic models to bring together planning, evaluation, and action: logic model development guide. Michigan: Kellogg Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. (1995). Constitution of the World Health Organization; https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/121457 [Google Scholar]

- Yousefichaijan P, Sharafkhah M, Rafiei M, & Salehi B (2016). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with overactive bladder; a case-control study. Journal of Renal Injury Prevention, 5(4), 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]