Abstract

Platelets mediate hemostasis by aggregating and binding to fibrin to promote clotting. Over time, platelets contract the fibrin network to induce clot retraction, which contributes to wound healing outcomes by increasing clot stability and improving blood flow to ischemic tissue. In this study, we describe the development of hollow platelet-like particles (PLPs) that mimic the native platelet function of clot retraction in a controlled manner and demonstrate that clot retraction-inducing PLPs promote healing in vivo. PLPs are created by coupling fibrin-binding antibodies to CoreShell (CS) or hollow N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAm) microgels with varying degrees of shell crosslinking. We demonstrate that hollow microgels with loosely crosslinked shells display a high degree of deformability and mimic activated platelet morphology, while intact CS microgels and hollow microgels with increased crosslinking in the shell do not. When coupled to a fibrin-binding antibody to create PLPs, hollow particles with low degrees of shell crosslinking cause fibrin clot collapse in vitro, recapitulating the clot retraction function of platelets, while other particle types do not. Furthermore, hollow PLPs with low degrees of shell crosslinking improve some wound healing outcomes in vivo.

Keywords: Synthetic platelet, fibrin, microgel, biomimetic, wound healing

Graphical Abstract

Platelets mediate hemostasis by aggregating and binding to fibrin. Over time, platelets induce clot retraction, which contributes to wound healing. We have developed hollow platelet-like particles (PLPs) that mimic clot retraction of native platelets in a controlled manner and demonstrate that PLPs capable of inducing clot retraction enhance healing outcomes in vivo.

Wound repair initiates at the onset of injury with the formation of a provisional fibrin mesh to cease bleeding and promote tissue remodeling by stimulating cell migration, angiogenesis, and matrix production. Platelets play a critical role in the wound healing process through their roles in hemostasis, clot retraction, and immune modulation. In the early stages of wound repair, platelets aggregate and promote fibrin polymerization to form the primary clot and stem hemorrhage. After cessation of bleeding, platelets induce fibrin clot retraction over several hours. Clot retraction significantly decreases clot size, alters clot organization and increases clot stiffness, thereby promoting ongoing wound repair[1–5]. Both intrinsic and medication-induced platelet dysfunction beyond hemostasis are associated with non-healing wounds; therefore, synthetic platelet therapies that reproduce the hemostatic and clot retraction features of native platelets could be effective therapies for treating non-healing wounds.

Due to the fundamental role of platelets in hemostasis, there has been great interest in developing synthetic platelets that interact with the native coagulation cascade to promote clotting and treat traumatic injury. A number of platelet-mimetic materials have been developed in recent years to reproduce the hemostatic properties of platelets; these efforts have recently been reviewed[3,6,7]. Overall, approaches to synthetic platelet design focus on replicating various platelet functions. One such example mimics platelet morphology to recreate platelet margination[8]. Other synthetic platelet designs incorporate a nanoparticle decorated with binding domains to mimic platelet binding to coagulation components. Some notable examples include RGD-PLL-PLGA particles[9], albumin microparticles coated with fibrinogen[10], and liposomal particles conjugated with GPIb[11]. Recent studies have also demonstrated that synthetic platelets encompassing collagen-binding and vWF-binding motifs[12] improve binding to wound sites under flow conditions. Injectable, shear-thinning composite hydrogels containing gelatin and silicate nanoplatelets have also been described for use as an embolic agent for endovascular embolization procedures[13,14].

Recently, we demonstrated a different approach to developing platelet mimetic materials to augment hemostasis using highly deformable poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (pNIPAm) hydrogels (microgels). When coupled to high affinity fibrin-binding antibodies to target the wound environment, these PLPs can mimic natural platelet functions to bind the wound site, stabilize clot structure, and enhance clot formation. PLPs have been previously evaluated for hemostatic effectiveness in vitro using a microfluidics device that emulates microvasculature; these studies showed PLPs induce clot formation. Additionally, PLPs honed to injury sites and augmented clotting in vivo in a rodent injury model. Perhaps most excitingly, this unique PLP design has been shown to mimic native platelet clot retraction. The high degree of particle deformability of the microgel body, along with high fibrin affinity of the conjugated fibrin antibody, facilitates a Brownian wrench mechanism that induces clot retraction [19].

PLP-induced clot retraction is an important feature for promoting clot stability and we postulate, that like native platelets, PLP-induced clot retraction could be used to enhance wound repair. The previous PLP design consisted of a highly deformable, ultra-low crosslinked (ULC) microgel that, when coupled to a fibrin-binding single domain variable fragment (sdFv) antibody, induced clot retraction; highly crosslinked fibrin-binding microgels did not induce clot retraction due to decreased particle deformability. In this communication, we describe a novel hollow microgel structure that provides a high level of control over particle deformability and thereby allows for previously unachieved control over clot retraction events that are essential to hemostasis and wound healing. We also demonstrate the ability to control the timing of clot retraction by “switching on” particle deformability. We achieved this by synthesizing CoreShell (CS) microgels with degradable cores. We hypothesized that upon core degradation, hollow microgels would display high degrees of deformability, mimic platelet morphology, and induce fibrin-clot collapse when coupled to fibrin-binding motifs in a manner similar to ULC-based PLPs. We also hypothesized that PLP-mediated clot retraction, like native platelet-mediated clot retraction, would enhance healing responses following injury. To explore this hypothesis, we characterized the effect of microgel architecture (CS vs. hollow) and shell crosslinking density on particle deformability and the ability to mimic native activated platelet morphology. We then conjugated CS or hollow microgels to fibrin-binding antibodies to create PLPs and analyzed the effect of particle architecture and shell crosslinking on clot retraction in vitro. Finally, an in vivo murine full-thickness dermal wound model was employed to compare topical application of CS PLPs, hollow PLPs, or saline on wound healing. Collectively, our results demonstrate that 1) platelet-mimetic materials can be created that facilitate temporal control over clot retraction and 2) platelet-mimetic materials that induce clot retraction can enhance some healing outcomes beyond hemostasis.

Hollow microgels with low degrees of crosslinking in the shell mimic activated platelet morphology:

To explore our hypothesis that hollow microgels will display high degrees of deformability and mimic activated platelet morphology, we first synthesized CS microgels by encasing a degradable microgel core with an outer microgel shell with varying degrees of crosslinking. Size characterization of CS microgels was quantified using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) (Supplemental Table 1), where an increase in BIS crosslinker in the shell resulted in a smaller hydrodynamic diameter, likely due to higher levels of core compaction[15]. Hollow particles formed after core dissolution showed an approximate 2-fold increase in hydrodynamic diameter compared to CS microgels. We next compared the morphology of intact CS microgels or hollow microgels to that of resting or active platelets using cryogenic scanning electron microscopy (CryoSEM) with a JEOL 7600F at 50000X magnification (Figure 1). Native circulating platelets display an ovoid morphology and form spindle-like projections[16] upon activation. This was confirmed with isolated resting human platelets and platelets activated with 0.25 U/mL human α-thrombin. CryoSEM revealed that CS microgels displayed a morphology similar to native inactive platelets, while hollow microgels with loosely crosslinked shells displayed morphologies similar to activated platelets with spindle-like projections (Figure 1). Further characterization of deformability was performed under dry conditions using AFM imaging of microgels spread on a glass surface. Microgel diameter increased and height decreased as BIS crosslinker percentage decreased, indicating higher degrees of deformability in less crosslinked microgels[17,18]. Previous studies with single-layer lightly self-crosslinked pNIPAm ULCs were observed to be highly deformable and spread extensively on surfaces, while the addition of crosslinking in the form of 2–7% BIS resulted in loss of particle deformability[17]. The results here suggest that due to their architecture, hollow microgels display high levels of deformability similar to ULC single layer microgels. However, this deformability diminishes with increasing crosslinking in the shell. The 2% BIS hollow microgels most closely mimicked activated platelet morphology with spindle-like projections, and demonstrated greater deformability spreading 2.8 times greater than 2% BIS CS microgels, and were therefore used in subsequent in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Figure 1: Hollow microgel structure imparts morphology similar to native platelets.

A. Schematic of hollow microgel synthesis following core degradation resulting in a deformable outer shell. Native circulating platelets display an ovoid morphology B that upon activation, forms spindle-like projections illustrated in C and imaged by CryoSEM imaging in D & E. CryoSEM imaging of microgel morphology was performed with a JEOL 7600F at 50000X magnification. At least 5 images at 50000X per condition were collected and representative images are shown. CoreShell microgels (F-I) illustrates a morphology similar to native resting platelets and corresponding Hollow microgels (J-M) resemble activated platelets with spindle-like projections. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) analysis (N) demonstrated hollow microgels display high deformability and spread more extensively on surfaces than CS microgels. Diameter and height traces were generated with Asylum AFM software for at least 30 microgels per condition from at least 3 different images. Representative images and height traces are shown.

Hollow microgels with low degrees of crosslinking in the shell recapitulate platelet-mediated clot retraction:

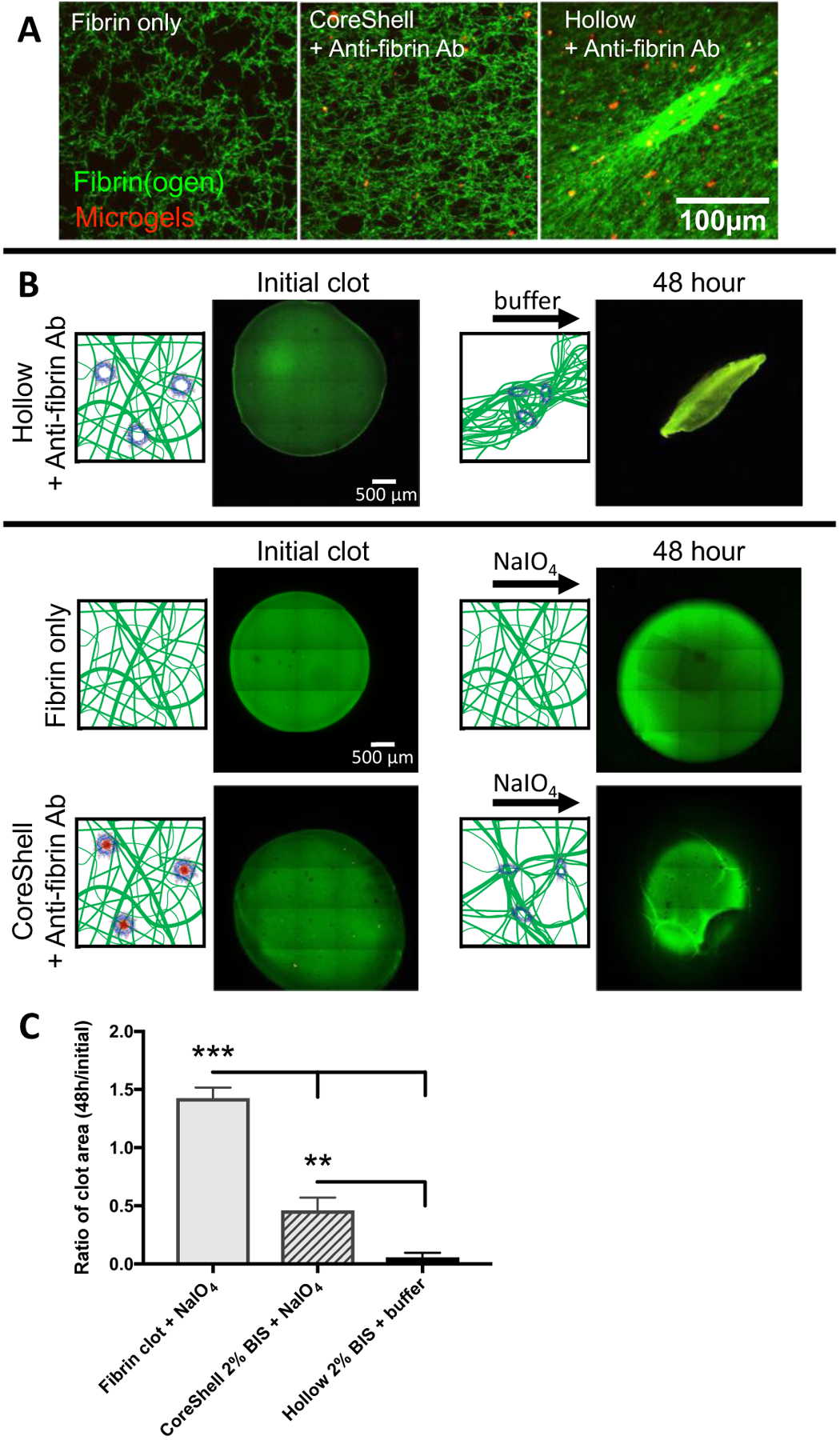

We next investigated how particle architecture influenced the ability of PLPs to induce clot retraction. Because of their high degree of deformability and morphological similarity to activated platelets, we hypothesized that PLPs constructed from hollow 2% microgels would induce clot retraction while intact CS microgel PLPs would not. This rationale is based on our previous studies which demonstrated PLPs constructed from highly deformable ULC microgels are able to spread extensively within fibrin networks and, due to a Brownian wrench mechanism, induce deformations within the fibrin network[19]. This mechanism was previously characterized using a combination of in silico and in vitro experiments and it was found that the high degree of particle deformability and high fibrin binding affinity allows PLPs to spread and interact extensively within fibrin networks. Over time, the particles return to a spherical shape but maintain their adhesion to the fibrin fibers, thereby inducing microcollapses within the network. In silico experiments in our previous publication demonstrated that increased particle deformability and strength of adhesion to the fibrin network decreased the time scale and increased the degree of collapse. Indeed, we observed that hollow fibrin-binding microgels with 2% BIS crosslinking in the shell are capable of inducing a fibrin clot collapse similar to clot collapse observed with native platelets. Figure 2 demonstrates fibrin clot collapse is dependent on particle deformability, where less deformable CS microgel PLPs did not significantly affect fibrin ultrastructure. The ability of hollow PLPs to induce clot retraction is likely due to the morphology of the hollow microgels, which allows the particles to spread within and interface extensively within the fibrillar fibrin network. Ultimately, these particles return to a spherical shape while maintaining connections with the fibrin network, thereby inducing microcollapses. This theory is supported by our previous in silico studies with deformable ULC-based PLPs[19]. CS PLPs do not exhibit these behaviors because they are more rigid due to the high degree of crosslinking in the core. This phenomenon’s dependence on deformability was again emphasized in situ where core degradation induced gross fibrin clot collapse (Figure 2B). Here, we investigated whether in situ degradation of the microgel core would result in inducible clot retraction. Fibrin clots were formed in the presence of intact CS PLPs. Following polymerization, sodium periodate (NaIO4) was added to the clots to induce core degradation. After 48 hours, we observed a decrease in clot size compared to the fibrin only control. However, the decrease in clot size was not as robust as in the presence of pre-degraded, hollow PLPs. Additionally, it should be noted that because this mechanism is driven by Brownian motion, resulting time scales are slower than those for clot retraction by native platelets.

Figure 2: Particle deformability is required for clot retraction.

Confocal microscopy demonstrated that when coupled to a fibrin-binding antibody, 2% BIS crosslinked hollow microgels increased fibrin network density, while intact CoreShell microgels did not, A. A minimum of 6 clots were analyzed per group and representative images are presented. Fibrin clot collapse can be seen in a bulk clot collapse where hollow particles induce contraction, B. Bulk clot collapse of CoreShell microgels conjugated to a fibrin-binding antibody, polymerized into a fibrin clot and then subjected to core degradation via 50 mM NaIO4 was also analyzed. Upon core degradation, gross fibrin clot collapse is observed, indicating that this design facilitates “triggerable” clot retraction. Clot area was measured at 48 hr and normalized to initial clot area C for at least n=3 clots per group; representative images are presented in B. Significance was determined with a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Hollow PLPs enhance wound healing outcomes in vivo:

Because native platelet-mediated clot retraction has been shown to enhance wound healing outcomes by decreasing clot size, altering clot organization, and improving reperfusion to the tissue[1,3,4,20], we hypothesized that hollow PLPs capable of inducing clot retraction would likewise enhance wound healing responses. We therefore investigated wound healing in a mouse full thickness dermal injury model treated with hollow PLPs, CS PLPs or saline. We found that hollow PLPs enhance some wound healing outcomes compared to CS PLPs or saline controls (Figure 3). Histology of wound cross-sections at day 8 with Martius Scarlet Blue (MSB) staining revealed an increase in fibrin deposition and an intact, significantly thicker epidermis (p<0.01) in hollow PLP treatment compared to saline controls or CS PLPs treatment. A trend of enhanced healing in the presence of hollow PLPs was observed. IHC of wound cross-sections showed a significant increase in CD31+ vessel numbers (p<0.001 hollow compared to saline or CS PLPs; Figure 3), an endothelial marker indicating angiogenesis, which is a critical step in wound healing, as well as an increase in proliferation marker Ki67. These combined results demonstrate topical application of deformable hollow PLPs improve some wound healing outcomes in a murine full thickness model to a greater extent than less deformable CS PLPs or saline. While significant differences were observed in histological measures, it should be noted that statistical differences were not observed in percent wound closure values. This is likely due to the small sample size and the small initial wound areas used and is a limitation of the study.

Figure 3: Hollow PLPs enhance wound healing outcomes in vivo.

Wound healing following topical application of saline, CS, or hollow PLPs was analyzed in a murine full thickness dermal injury model (n=5/group). Representative images of wounds at 0, 2, 5, and 8 days post-injury are shown in A. Histology of wound cross-sections at day 8 with MSB staining B revealed a thicker epidermis in response to hollow PLP treatment compared to saline or CS PLP groups. IHC of wound cross-sections also showed an increase in CD31+ vessels, C, indicating the presence of endothelial cells forming new blood vessels, or angiogenesis, which is a critical step in wound healing. Additionally, IHC showed an increase in proliferation marker Ki67, D. Percent wound closure is presented in E. Wound area was measured each day over an 8 day period and normalized to the wound’s corresponding initial area. N=5/group. Mean and SD are presented at each time point. Epidermal thickness was quantified, F, from MSB images at Day 8 by measuring 5+ areas per image for n=4 images. CD31 positively labeled tissue was quantified, G, by measuring total number of CD31+ vessels per 40X image for at least 15 histological samples for each treatment condition. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for epidermal thickness measurements and a Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for CD31+ vessel counts to analyze statistical significance with significance determined as p<0.05. ** p < 0.01; ***p<0.001.

In our in vivo model, functional endogenous platelets are expected to contribute to wound healing; therefore, the comparison between hollow PLPs and saline demonstrates enhanced healing over that observed in the presence of native platelets (i.e. the saline control). Recent reports have demonstrated that the application of platelet rich plasma (PRP), which delivers additional native platelets to the wound bed, significantly decreased wound sizes in mouse full thickness injury models, similar to the one utilized in this investigation. Specifically, studies by Etulain et al demonstrated that PRP decreased wound size after 10 days by ~20% compared to saline treated animals[21], which is similar to our observations (Figure 3).

Conclusions

In conclusion, hollow microgels consisting of loosely crosslinked pNIPAm-BIS-AAc shells created by dissolving a degradable core show significant potential to assume key functions of endogenous platelets. These synthetic particles are able to mimic platelet morphology and, when coupled to fibrin-binding motifs, can function to mediate fibrin clot retraction in a manner similar to native platelets. Native platelets within a clot bind fibrin fibers, spread within and actively modify the fibrin network, leading to clot retraction; this results in increased fibrin density and matrix stiffness[1,22,23]. This increased fibrin density and clot stiffness contributes to enhanced healing through a number of mechanisms including enhanced clot stability and increased resistance to fibrinolysis. Native platelets are capable of generating great contractile forces upon activation and, combined with their high elasticity, are capable of stiffening clots in conjunction with strain stiffening of fibrin under tension due to platelet contraction[23]. Platelet cytoskeletal motility proteins and Factor 13 (FXIIIa) mediate clot structure and bring about a differential structural gradient, with platelets concentrated at the clot perimeter and close-packed polyhedral erythrocytes retained in the center[24,25]. The ability to mimic and controllably induce clot retraction in a synthetic platelet platform could be used to mimic these platelet functions and promote healing beyond the initial cessation of bleeding.

We demonstrate that our hollow PLP architecture and composition can be conjugated to a fibrin-binding motif and tuned to achieve the appropriate degree of deformability necessary to reproduce the mechanical function of clot retraction. 2% BIS hollow microgels showed optimal platelet-like morphology and clot contraction and were tested in vivo in a rodent model of dermal wound repair, revealing improved histological outcomes compared to saline controls. Microgel-mediated clot retraction has previously been shown to be dependent upon a microgel’s 1) fibrin-binding ability and 2) deformability (ability to spread on a glass surface)[19]. 2% BIS CoreShell PLPs have the ability to bind fibrin, however they lack the deformability necessary to induce a clot retraction, as seen in confocal microscopy images in Figure 2A. When the densely crosslinked NIPMAm-DHEBA core is degraded with NaIO4, however, a deformable hollow pNIPAm-BIS shell remains, which facilitates fibrin network deformation (Figure 2A) We demonstrate that deformability can be “switched on” through core degradation following incorporation of CoreShell PLPs into fibrin clots, creating hollow PLPs, which are then capable of inducing clot retraction as demonstrated in the images presented in Figure 2B. The ability to “switch on” deformability which triggers clot retraction could therefore allow for temporal control over induction of clot retraction. In conclusion, hollow fibrin-binding microgels are biomimetic and are a promising platform for promoting wound repair.

Experimental Section

CoreShell & Hollow Microgel Synthesis

CS microgels were constructed by first producing a core containing N-isopropylmethacrylamide (NIPMAm) and crosslinked with N,N′-(1,2-Dihydroxyethylene)bisacrylamide (DHEBA) (Sigma) through a precipitation polymerization reaction. NIPMAm was recrystallized with hexanes. NIPMAm and DHEBA (90% and 10% of a 140 mM monomer solution by weight respectively) in ultrapure water were filtered over a 0.22 μm membrane into a 3-neck reaction vessel heated in silicon oil, stirred at 450 rpm, and fluxed at 70°C for 1 hr under nitrogen. 1 mM ammonium persulfate (APS) was added to initiate the reaction. After 6 hours, cores were purified by filtering over glass wool to remove large aggregates and by dialysis (1000 kDa MWCO tubing (Spectrum)) against ultrapure water for 2 days. Cores were enveloped within shells in a second precipitation polymerization reaction. A solution containing N-Isopropylacrylamide (NIPAm) and N,N′-Methylenebisacrylamide (BIS) was dissolved in ultrapure water and filtered. The solution was mixed with purified cores in a volume ratio of 60% shell to 40% core solutions. The final concentrations of shell monomers and BIS ranged from 85–94% and 1–10% by weight of a 40 mM total monomer solution, respectively. 5% Acrylic acid (AAc) was added before initiation with APS to facilitate chemoligation of the fibrin-binding antibody. Following synthesis, CS microgels were purified as described above. To create hollow microgels, CS microgels were incubated with 50 mM sodium periodate (NaIO4) at room temperature for up to 48 hours to cleave the DHEBA crosslinks (diols).

Microgel Characterization

Microgel hydrodynamic diameters were determined in 1X HEPES (25 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) through DLS using a Zetasizer Nano S (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK). Diameters were averaged from 5 measurements (each measurement was averaged from 5 runs for 30 sec each). Microgel deformability was determined with AFM imaging (MFP-3D BIO AFM, Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA). Glass coverslips were cleaned by submerging in a series of solutions in an ultrasonic bath for 10 min each: alconox detergent, water, acetone, absolute ethanol, and isopropyl alcohol. Microgel suspensions were pipetted onto clean, dry coverslips and allow to dry overnight. AFM imaging was performed in tapping mode with silicon probes (ARROW-NCR, NanoAndMore, Watsonville, CA). Average diameter and heights +/− standard deviation were determined for at least 30 microgels per condition from at least 3 different images using ImageJ image analysis software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Microgel morphology was characterized in water using cryogenic scanning electron microscopy (CryoSEM) with a JEOL 7600F at 50000X magnification. At least 5 images were collected per condition. For a comparison to native platelets, blood was acquired from the New York Blood Center (New York City, NY) and platelets were isolated by centrifugation at 150 g for 15 min with no deceleration to remove red blood cells and the buffy coat. Additional centrifugation of the platelet-rich plasma at 900 g’s for 5 minutes concentrated platelets into a pellet that was subsequently washed and resuspended according to Cazenave et al. [26] in Tyrode’s albumin buffer (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). Platelets were activated by the addition of 0.25 U/mL human α-thrombin (Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend, IN) immediately before imaging.

Analysis of fibrin clot collapse

A fibrin-binding IgG antibody (Sheep anti-human Fibrin fragment E, Affinity Biologicals, Ancaster, ON) was conjugated to microgels through EDC/NHS coupling. Fibrin clots were prepared with a final fibrinogen concentration (FIB 3, Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend, IN) of 2 mg/mL, 10% of which was Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated fibrinogen (Fisher Scientific) to allow for visualization of the fibrin matrix. The clot was polymerized with 0.5 U/mL human α-thrombin (10% by volume) in the presence or absence of fibrin-binding or control microgels. The effect of microgels on microscopic clot structure was analyzed using fluorescence confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 710) on 25 μL clots, observed as overlaid z-stacks (63X water immersion objective, section step 0.63 μm). A minimum of 6 clots were analyzed for each treatment condition. Gross clot collapse over time of fibrin clots with and without CoreShell 2% BIS microgels treated with core degrading NaIO4 was also analyzed through confocal microscopy. 25 μL fibrin clots with approximate mean cross sectional areas of 8.6 μm2 were created in glass bottom dishes and imaged 1 and 48 hrs following polymerization. Clot area was measured as total cross sectional area from 10X tiled scans using ImageJ. Change in area over time was determined by comparing crosssectional areas at 48 hours to corresponding initial area. At least three clots were imaged per condition and average area ratios +/− standard deviations are presented. Statistical analysis was determined by a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test with p < 0.05. A Shaprio-Wilk Normality test was run to check normality of data; these values passed the normality test. A Bartlett’s test indicated that the variance of the groups did not differ significantly.

Analysis of wound healing in vivo

The effect of microgels on wound healing was assessed in an in vivo murine wound model of wound healing described by Dunn et al[27]. All procedures were approved by the NCSU IACUC. Male C57/B6 mice were anesthetized using general anesthesia (5% isoflurane in 100% oxygen, flow rate 2 L/min, and maintained at 2–3% isoflurane) through a nose cone for the duration of surgery. A full thickness dermal wound extending through the subcutaneous tissue and panniculus carnosus was created and a topical application of microgels (10 μL of 2 mg/mL in 0.9% saline pH 7.4) was applied directly to the wound and control wounds received 0.9% saline pH 7.4 only. The wounds were splinted with 10 mm diameter silicone rings with 5 mm inner diameter holes and imaged. Microgel PLP treatment groups (saline, CoreShell 2% BIS, and Hollow 2% BIS) were applied topically to the site of the wound in a 10 μL solution at 4 mg/mL which is a relatively non-viscous solution, similar in consistency to saline, and not a “wound gel.” The volume of 10 μL is small enough to remain on the 4 mm diameter wound site without rinsing off or leaving the wound border. Different treatments were applied topically to the 2 wounds created per mouse to diminish animal-specific variability with n=5 for each treatment, prior to suturing the silicone splint into place. Wounds were covered with a waterproof, but moisture vapor permeable Opsite wound dressing, applied to the surface of the silicone ring to cover, but not interact with the wounds. Before removing the mice from anesthesia, 5 mg/kg carprofen was administered via sub-cutaneous injection for post-operative pain relief and was then administered once daily for 5 days. Opsite wound dressings were removed for daily imaging and replaced with fresh dressings for 8 days. Images were analyzed to quantify wound closure as a measure of wound size compared to the inner area of the silicone splint normalized to each wound’s initial area. The analysis of the wound size from daily images was blinded by treatment group and the order of analysis was randomized through a random integer generator. Wound boundaries were determined manually, primarily through visual inspection of apparent changes in color between the wound and healed areas. Apparent visual differences between tissue texture and height were also used to determine wound boundary.

Dermal tissue surrounding wounds was excised on day 8 following euthanasia, fixed, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned (10 μm). Sections were stained with Martius Scarlet Blue (MSB), and epidermal thickness was measured on MSB images at 5 regions evenly spaced throughout the wound area for 4 samples per group. Additional immunohistochemistry was performed on sister sections to visualize smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and endothelial cell marker CD31 (PECAM-1), indicating the presence of newly formed blood vessels, or angiogenesis, which is a critical step in wound healing. For immunohistochemistry, tissue was deparaffinized, rehydrated, and antigen retrieval using citrate buffer was performed. Tissue was incubated with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Fisher Scientific) in PBS prior to antibody labeling. Sections were co-labeled with polyclonal antibody to α-SMA (1:500, clone PA5–18292, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and monoclonal antibody to CD31 (1:50, clone SP38, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) overnight at 4°C, washed, and labeled with secondary antibodies (Alexa 488 and Alexa 594, respectively) 45 minutes at room temperature. Sections were washed and mounted with Vectashield HardSet mounting medium with DAPI (Fisher Scientific), and imaged with fluorescence microscopy (EVOS FL Auto Cell Imaging System, Fisher Scientific). CD31 positively labeled tissue was quantified using ImageJ. CD31+ vessel number was obtained via 1) a manual count of fluorescent vessels in the red channel (presented in Figure 3) and 2) an automated method in which ImageJ Particle Analysis was to measure the number of vessels (using a size threshold of particles greater than 1.0 μm2 and an intensity threshold of 0–50; presented in Supplemental Figure 1) for at least 15 slides per treatment condition (n=25 for saline; n=15 for C/S; n=30 for hollow). For all quantitative analysis of healing parameters, rates of healing, epidermal thickness, and CD31+ vessel number, mean +/− SD are presented. A Shaprio-Wilk Normality test was run to check normality of data and a Bartlett’s test was utilized to analyze variance of the groups. A Bartlett’s test indicated that the variance of the groups did not differ significantly for epidermal thickness values, therefore an ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test with significance determined as p<0.05 was used to analyze this data. Analysis of vessel counts indicated that these data did not pass the normality test and the variance of the groups differed significantly. Therefore, for the vessel count data, a Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was utilized to analyze statistical significance.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with Prism software program (GraphPad, San Diego CA). A Shaprio-Wilk Normality test was run to check normality of data and a Bartlett’s test was utilized to analyze variance of the groups. When data passed normality tests and variances did not signficantly differ, data was analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey’s post hoc test at a 95% confidence interval. Data that did not pass these tests were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test to analyze statistical significance. Means +/− standard deviation are reported. For all analyses, a minimum of three samples were analyzed per group. Any specific pre-processing of data (such as normalization) and specific sample sizes for each experimental are detailed in specific experimental sections above.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided from the National Institute of Health NIAMS R21AR071017 and the Abrams Scholars Program (CR). We also thank NSF (OISE-1357113) and the Australian Governments Endeavour Study Overseas Short-term Mobility Program for enabling international exchange programs to support this work. This work was performed in part at the Analytical Instrumentation Facility (AIF) at NCSU, which is supported by the State of North Carolina and the National Science Foundation (ECCS-1542015). The AIF is a member of the North Carolina Research Triangle Nanotechnology Network (RTNN), a site in the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI). The authors acknowledge Benjamin J. Igo for assistance with microgel synthesis, Jessica Basso for assistance with in vivo studies, Drs. Jacquline Cole and Matthew Fisher for their generous access to a Microtome, Elaine Zhou at the AIF for assistance with CryoSEM, and Eva Johannes at the CMIF for assistance with confocal microscopy.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

References

- [1].Tutwiler V, Litvinov RI, Lozhkin AP, Peshkova AD, Lebedeva T, Ataullakhanov FI, Spiller KL, Cines DB, Weisel JW, Blood 2016, 127, 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Qiu Y, Brown AC, Myers DR, Sakurai Y, Mannino RG, Tran R, Ahn B, Hardy ET, Kee MF, Kumar S, Bao G, Barker TH, Lam WA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2014, 111, 14430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nandi S, Brown AC, Exp. Biol. Med 2016, 241, 1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Stalker TJ, Welsh JD, Tomaiuolo M, Wu J, Colace TV, Diamond SL, Brass LF, Blood 2014, 124, 1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Muthard RW, Diamond SL, Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 2012, 32, 2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hu Q, Bomba HN, Gu Z, Front. Chem. Sci. Eng 2017, 11, 624. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sen Gupta A, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol 2017, 9, n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Anselmo AC, Modery-Pawlowski CL, Menegatti S, Kumar S, Vogus DR, Tian LL, Chen M, Squires TM, Sen Gupta A, Mitragotri S, ACS Nano 2014, 8, 11243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bertram JP, Williams CA, Robinson R, Segal SS, Flynn NT, Lavik EB, Sci. Transl. Med 2009, 1, 11ra22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Takeoka S, Teramura Y, Okamura Y, Handa M, Ikeda Y, Tsuchida E, Biomacromolecules 2001, 2, 1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rybak ME, Renzulli LA, Biomater. Artif. Cells Immobil. Biotechnol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Artif. Cells Immobil. Biotechnol 1993, 21, 101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ravikumar M, Modery CL, Wong TL, Dzuricky M, Sen Gupta A, Bioconjug. Chem 2012, 23, 1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Avery RK, Albadawi H, Akbari M, Zhang YS, Duggan MJ, Sahani DV, Olsen BD, Khademhosseini A, Oklu R, Sci. Transl. Med 2016, 8, 365ra156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhang YS, Khademhosseini A, Science 2017, 356, DOI 10.1126/science.aaf3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jones CD, Lyon LA, Macromolecules 2003, 36, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Seifert J, Rheinlaender J, Lang F, Gawaz M, Schäffer TE, Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 4810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bachman H, Brown AC, Clarke KC, Dhada KS, Douglas A, Hansen CE, Herman E, Hyatt JS, Kodlekere P, Meng Z, Saxena S, M. W. S. Jr, Welsch N, Andrew Lyon L, Soft Matter 2015, 11, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Joshi A, Nandi S, Chester D, Brown AC, Muller M, Langmuir 2017, DOI 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b02801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Brown AC, Stabenfeldt SE, Ahn B, Hannan RT, Dhada KS, Herman ES, Stefanelli V, Guzzetta N, Alexeev A, Lam WA, Lyon LA, Barker TH, Nat. Mater 2014, 13, 1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Qiu Y, Brown AC, Myers DR, Sakurai Y, Mannino RG, Tran R, Ahn B, Hardy ET, Kee MF, Kumar S, Bao G, Barker TH, Lam WA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2014, 111, 14430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Etulain J, Mena HA, Meiss RP, Frechtel G, Gutt S, Negrotto S, Schattner M, Sci. Rep 2018, 8, 1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Myers DR, Qiu Y, Fay ME, Tennenbaum M, Chester D, Cuadrado J, Sakurai Y, Baek J, Tran R, Ciciliano JC, Ahn B, Mannino RG, Bunting ST, Bennett C, Briones M, Fernandez-Nieves A, Smith ML, Brown AC, Sulchek T, Lam WA, Nat. Mater 2017, 16, 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lam WA, Chaudhuri O, Crow A, Webster KD, Li T, Kita A, Huang J, Fletcher DA, Nat. Mater. Lond 2011, 10, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cines DB, Lebedeva T, Nagaswami C, Hayes V, Massefski W, Litvinov RI, Rauova L, Lowery TJ, Weisel JW, Blood 2014, 123, 1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Byrnes JR, Duval C, Wang Y, Hansen CE, Ahn B, Mooberry MJ, Clark MA, Johnsen JM, Lord ST, Lam WA, Meijers JCM, Ni H, Ariëns RAS, Wolberg AS, Blood 2015, 126, 1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cazenave J-P, Ohlmann P, Cassel D, Eckly A, Hechler B, Gachet C, in Platelets Megakaryocytes, Humana Press, 2004, pp. 13–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dunn L, Prosser HCG, Tan JTM, Vanags LZ, Ng MKC, Bursill CA, J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2013, DOI 10.3791/50265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.