Abstract

There is an urgent need to transform the accessibility, efficiency, and quality of mental healthcare to address the global mental health crisis in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The next generation of efforts to transform mental healthcare must foster the implementation of learning organizations, or organizations that continuously improve based upon ongoing data collection. The concept of learning organizations is highly regarded but not well-operationalized, particularly in mental healthcare. This Open Forum concretely operationalizes key building blocks of a learning organization in mental healthcare which is needed in order to set a research agenda and to transform care through the example of telemental health care.

We face a global mental health crisis, which has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic with anticipated increases in anxiety, depression, substance abuse, loneliness, and domestic violence.1 There is an urgent need to transform the accessibility, efficiency, and quality of mental healthcare. As systems rapidly convert to delivering telemental health services during COVID-19, organizations find themselves needing to change delivery mode while also ensuring that quality and safety do not suffer.2 These changes are occurring within the context of policy that may remove structural barriers to mental healthcare. Clinicians can now work across state lines, federal approval processes have been streamlined, and virtual care is now reimbursable for a range of disciplines. These changes present opportunities to innovate and improve patient-centered care. It is now possible to harness the perspectives of stakeholders alongside passively collected data to glean meaningful insights for practice change. With the right infrastructure for organizational learning, efficient and systematic improvement can occur even in the face of a rapidly changing environment. In this Open Forum, we argue that to transform mental health care and to nimbly adapt to evolving challenges, it is necessary to empower consumers, clinicians, and organization to understand how to use both stakeholder input and local real-time information about care processes. The next generation of efforts to transform mental healthcare must foster the implementation of learning health organizations and systems (hereafter referred to as learning organizations).

What is a learning organization?

Learning organizations collect data, interpret it, and feed it back into the organization for continuous improvement. Drawing upon the recent work of the National Academy of Medicine3 and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (https://www.ahrq.gov/learning-health-systems/about.html), learning organizations are able to “continuously, routinely, and efficiently study and improve themselves.”4 Five key features include: every patient’s data is available for learning, data is available immediately to support healthcare decisions, continuous improvement processes, an infrastructure that allows for data collection to happen routinely and automatically, and stakeholder involvement.4

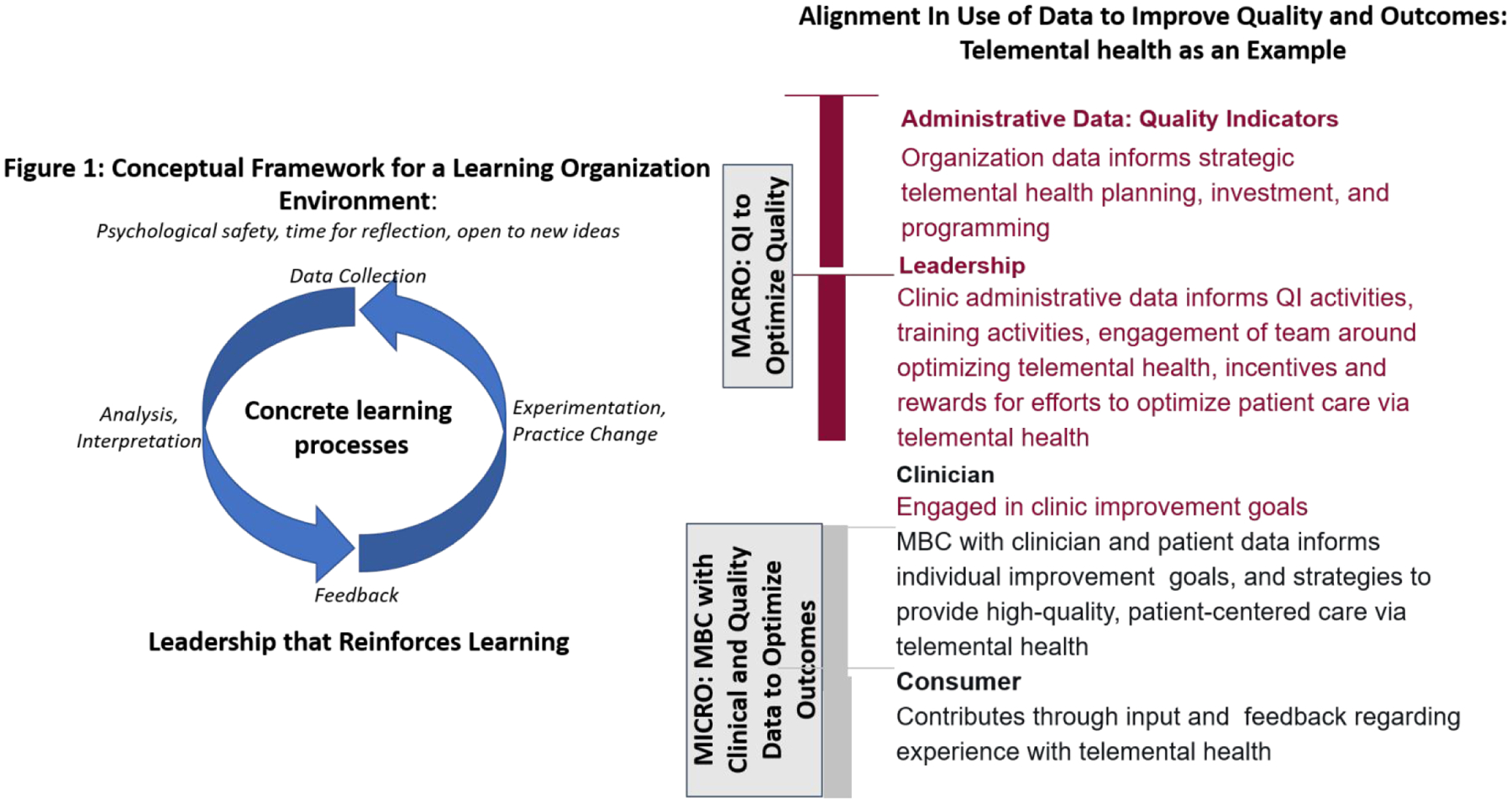

To date, in mental health, efforts to implement concepts from the learning organization literature have been represented in consortiums such as the Mental Health Research Network5and National Network of Depression Centers.6 These initiatives represent affiliations between large health systems that follow standardized protocols around key initiatives such as suicide prevention and measurement based care. These are excellent examples of how systems can come together to learn from one another. However, there is limited empirical information about the mechanisms via which learning organizations function. For optimal results, learning and improvement should ripple through all levels of the organization. Efforts to date to bring this concept to life in mental healthcare have largely leveraged electronic health records (EHR) and other local data to inform broad improvement initiatives or smaller continuous quality improvement (CQI) efforts. For example, CQI has been used to improve consumer access and engagement by reducing wait times.7 However, this approach is best suited to improving organizational care processes (i.e., macro-level) rather than to support individual clinician change. Particularly when the change requires engagement and behavior change at the clinician level, it is likely that this approach alone will not be sufficient to transform care. On the other hand, measurement-based care (MBC) can perhaps be considered quality improvement at a micro-level, as it involves the clinician and patient more directly in practice change efforts through a similar process of using clinical data.8 MBC allows individual clinicians to track progress in therapy process and to use that information to decide whether and what changes need to be made to improve. However, while complementary and sharing a common goal of using data to inform improvement,8 CQI and MBC are rarely if ever used together. We propose that the key mechanism of a learning organization is true alignment and empowerment of stakeholders at both the organizational and clinician levels to continuously use the most relevant data at each level -- including feedback from consumers -- to engender clinical practice and organizational change (See online supplement).9

What are key components of learning organizations in mental health care?

The concept of learning organizations is largely aspirational in mental healthcare. Research that investigates how to implement learning organizations is needed to transform mental health care globally. Below, we operationalize key building blocks of a learning organization in mental healthcare by providing the example of telemental health care given its relevance in light of COVID-19.

The role of consumers.

Consumers of mental health services have few opportunities to provide systematic feedback to the organization that serves them. Integrating consumer feedback about the processes they find most helpful and their progress on metrics that are most meaningful to them into systems will foster innovation and move mental healthcare systems toward patient-centeredness. Consumer needs must be the primary drivers of systemic change. The best methods of how to solicit patient input must be empirically derived.10 For example with the deployment of telemental health, consumer feedback on technology satisfaction and the methods of sending support materials and psychotherapy tools can ensure that care remains accessible and satisfactory.

The role of clinicians.

Engaging and empowering clinicians to problem solve to optimize care processes and make practice changes in response to clinical data is a key component. In a fully aligned learning organization, leaders would support clinicians in continuing to deliver MBC via telemental health, with standard assessment scales to determine care effectiveness. When key outcomes are not improving, some clinicians may review their data and use it to discuss the therapeutic alliance or session attendance whereas others might decide to focus on adopting an evidence-based practice. Without institutional support and stakeholder input, MBC could easily fall by the wayside due to challenges in completion and transmission of these assessments.

The role of organizational leadership.

Garvin’s11 learning organization framework highlights important factors such as leadership that reinforces learning and environmental factors such as psychological safety (i.e., an environment where it is safe to iterate and acknowledge challenges).12 Leaders can create a climate and culture of psychological safety and learning from feedback or they can inadvertently reinforce demoralization and resistance to change. Clinicians need leaders to create a psychologically safe context in order to willingly reflect on clinical data to improve care and outcomes and to make data-informed changes to their practice. For example, in telemental health, it is necessary for clinicians to feel that it is safe for them to reflect on barriers that they experience without fear and to be able to brainstorm effectively and creatively. They will also require support in navigating rapidly changing policies and expectations regarding telemental health.

Technology to obtain data rapidly and at scale.

We need to be able to rapidly extract data from various sources, including EHRs, to offer actionable real-time data. This means that systems such as the EHR that were engineered for billing need to be re-envisioned to facilitate rapid extraction and interpretation of data needed for care decisions. It is important that systems synthesize and share data in a way that is meaningful and actionable for stakeholders. This means that all stakeholders must be at the table from the beginning in deciding what data is meaningful and why, and that individuals be employed within the system who can interpret the data within the context of that particular system for nimble response. For example, data on scheduled and kept sessions, technical difficulties, collection of patient reported outcomes, and other important metrics determined via stakeholder input can be extracted on a daily basis to inform changes that need to be made to processes to increase access, engagement, and quality of during the rapid shift to telemental health care.

Insights from other fields can help enhance the deployment of a learning organization.

Clinicians must be treated as equal partners in efforts to optimize outcomes, and recognition of their efforts and contributions are essential.13 Clinicians can ensure that solutions are well-integrated into workflow. Incentives and rewards are potent levers that leaders can deploy to empower, motivate, and reinforce clinicians to optimize the care that they provide, and to recognize the efforts they are making to do so. A systematic review found that financial incentives may be effective in changing professional practice in healthcare, particularly in improving care processes.14 An alternative strategy, social incentives, suggests that motivation can be influenced by a desire to uphold the personal, internalized professional standards that are shared by those who enter the healthcare profession. Incentives and rewards of this nature can be deployed to motivate individual change15– for example with regard to clinician motivation to use MBC during the shift to telemental health. Questions with regard to how care systems can promote and spread financial and social incentives are critical within this research agenda; inclusion of their perspective in the design and deployment of these approaches from the beginning are critical.

Conclusion

In these unprecedented times, when “learning as we go” and adapting rapidly to face the current crisis has become the new norm, perhaps most noticeably in the rapid implementation of telemental health care, the principles and practices of learning organizations are more important than ever. Moving beyond aspirational goals and toward functioning as learning organizations in mental healthcare will require both the technological capacity and consistent leader behaviors that spark clinician motivation, reflection, and innovation. This requires a psychologically safe environment that encourages reflection, engaging individuals and teams in efforts to learn from data and iterate rapidly, and using incentives and rewards effectively. These steps can inspire and celebrate the efforts and contributions of clinicians and leaders at all levels of an organization to better serve our patients at a time when they need the very best we have to offer.

Figure 1.

Alignment in the use of data to improve quality and outcomes

Funding:

P50 MH 113840. The funders played no role in our conceptualization or execution of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Beidas reports royalties from Oxford University Press and has received consulting fees from the Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers. Dr. Wiltsey Stirman reports no disclosures.

References

- 1.Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N.: The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med. (Epub ahead of print, April 10, 2020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torous J, Wykes T: Opportunities from the Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic for transforming psychiatric care with telehealth. JAMA Psychiatry. (Epub ahead of print, May 11, 2020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine (US): Grossmann C, Powers B, McGinnis JM, editors. Digital infrastructure for the learning health system: the foundation for continuous improvement in health and health care: Workshop series summary. National Academies Press (US); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman CP, Allee NJ, Delaney BC, et al. : The science of Learning Health Systems: foundations for a new journal. Learn Health Sys. 2017; 1:e10020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon G, Platt R, Hernandez A: Evidence from pragmatic trials during routine care—slouching toward a Learning Health System. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:1488–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zandi P, Wang Y, Patel P, et al. : Development of the national network of depression centers mood outcomes program: a multisite platform for measurement-based care. Psychiatric Services. 2020; 71:456–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarty D, Gustafson DH, Wisdom JP, et al. : The Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx): enhancing access and retention. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(2–3):138–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg SB, Babins-Wagner R, Rousmaniere T, et al. : Creating a climate for therapist improvement: a case study of an agency focused on outcomes and deliberate practice. Psychotherapy. 2016; 53: 367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison MI, Shortell SM: Multi‐level analysis of the learning health system: integrating contributions from research on organizations and implementation. Learning Health Syst 2020;e10226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green C, Estroff S, Yarborough BJH et al. : Directions for future patient-centered and comparative efectiveness research for people with serious mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2014; 40: i–S94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garvin DA, Edmondson AC, Gino F: Is yours a learning organization? Harv Bus Rev. 2008; 86:109–116, 134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morain SR, Kass NE, Grossmann C: What allows a health care system to become a learning health care system: results from interviews with health system leaders. Learning Health Syst. 2017; 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cassel CK, Jain SH: Assessing individual physician performance: does measurement suppress motivation? JAMA. 2012; 307:2595–2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flodgren G, Eccles MP, Shepperd S, et al. : An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD009255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emanuel EJ, Ubel PA, Kessler JB, et al. : Using behavioral economics to design physician incentives that deliver high-value carebehavioral economics, physician incentives, and high-value care. Ann Intern Med. 2016; 164:114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]