Abstract

Introduction E-cigarette use during pregnancy is a risk factor for maternal and fetal health. Early studies on animals showed that in utero exposure to e-cigarettes can have negative health outcomes for the fetus. There has been only limited research into the risk perceptions of e-cigarette use during pregnancy. This study was conducted to comprehensively characterize the constructs of risk perceptions with regard to e-cigarette use during pregnancy using an I ntegrated H ealth B elief M odel (IHBM).

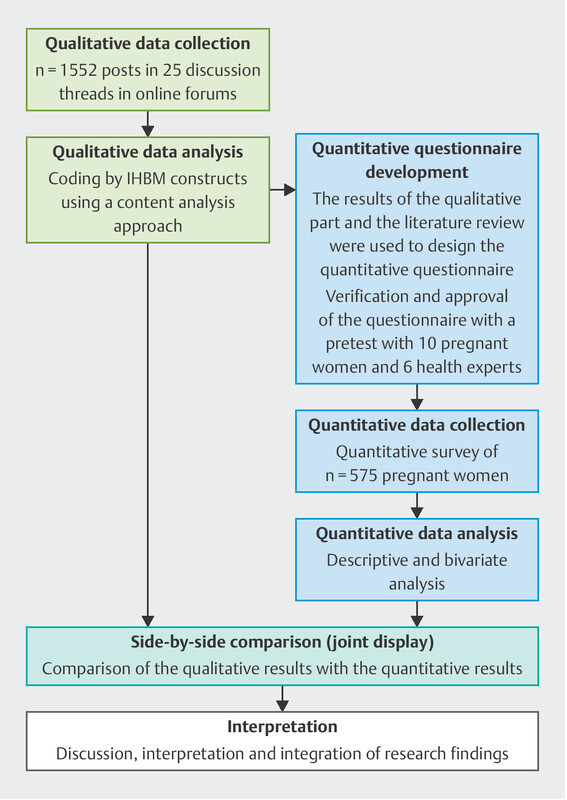

Methods Our ST udy on E -cigarettes and P regnancy (STEP) used a mixed methods approach, with the study divided into an initial qualitative part and a quantitative part. A netnographic approach was used for the first part, which consisted of the analysis of 1552 posts from 25 German-language online discussion threads on e-cigarette use during pregnancy. Using these qualitative results, a quantitative questionnaire was developed to explore risk perception constructs about e-cigarette use during pregnancy. This questionnaire was subsequently administered to pregnant women (n = 575) in one hospital in Hamburg, Germany. Descriptive and bivariate analysis was used to examine differences in risk perception according to participantsʼ tobacco and e-cigarette user status before and during pregnancy. While the study design, methods and sample have been extensively described in our recently published study protocol in the January 2020 issue of Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde , this paper is devoted to a presentation of the results of our mixed methods study.

Results Themes related to perceived threats identified in the qualitative study part were nicotine-related health risks and potential health risks of additional ingredients . Perceived benefits were possibility and facilitation of smoking cessation and a presumed potential to reduce harm . The subsequent quantitative part showed that nearly all participants (99.3%) perceived e-cigarettes which contained nicotine as constituting a threat to the health of the unborn child. The most commonly perceived barrier was health-related (96.6%), while the most commonly perceived benefit was a reduction in the amount of tobacco cigarettes consumed (31.8%). We found that particularly perceived benefits varied depending on the participantʼs tobacco and e-cigarette user status.

Conclusion When considering future prevention strategies, the potential health risks and disputed effectiveness of e-cigarettes as a tool for smoking cessation need to be taken into account and critically discussed.

Key words: electronic cigarette, pregnancy, risk perception, Health Belief Model, online forums, mixed methods

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung Die Nutzung von E-Zigaretten während der Schwangerschaft wird als Risikofaktor für die maternale und fetale Gesundheit diskutiert. Erste Studien an Tieren zeigen, dass die Exposition im Mutterleib zu negativen Gesundheitsoutcomes für den Fetus führen kann. Bisher wurden kaum Ergebnisse zur Risikowahrnehmung der E-Zigarette während der Schwangerschaft publiziert. Diese Studie wurde durchgeführt, um Konstrukte der Risikowahrnehmung der E-Zigaretten-Nutzung während der Schwangerschaft unter Verwendung eines integrierten Health-Belief-Modells (IHBM) umfassend zu charakterisieren.

Methoden Unsere Studie zur E-Zigarette und Schwangerschaft (STEP) verwendete einen Mixed-Methods-Ansatz, beginnend mit einem qualitativen Studienteil und einem anschließenden quantitativen Studienteil. Zunächst wurde ein netnografischer Ansatz verwendet, indem 1552 Beiträge in 25 deutschsprachigen Online-Diskussionssträngen, die sich mit dem Gebrauch von E-Zigaretten während der Schwangerschaft befassten, analysiert wurden. Basierend auf den qualitativen Ergebnissen wurde ein quantitativer Fragebogen entwickelt, in dem Konstrukte der Risikowahrnehmung der E-Zigaretten-Nutzung während der Schwangerschaft untersucht wurden. Dieser Fragebogen wurde anschließend an Schwangere (n = 575) in einem Krankenhaus in Hamburg verteilt. In deskriptiven und bivariaten Analysen wurden Unterschiede in der Risikowahrnehmung in Abhängigkeit von dem Tabak- und E-Zigaretten-Nutzerstatus vor und während der Schwangerschaft untersucht. Während das Studiendesign, die Methodik und die Stichprobe von STEP ausführlich in unserem kürzlich veröffentlichen Studienprotokoll in der Januar-Ausgabe 2020 von Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde beschrieben wurde, widmet sich dieses Paper der Präsentation der Forschungsergebnisse unserer Mixed-Methods-Studie.

Ergebnisse Themen, die im Zusammenhang mit wahrgenommenen Bedrohungen im qualitativen Studienteil identifiziert wurden, waren nikotinbedingte Gesundheitsrisiken und potenzielle Gesundheitsrisiken zusätzlicher Inhaltsstoffe. Wahrgenommene Vorteile waren die Möglichkeit und Erleichterung der Raucherentwöhnung und die Vermutung, Schaden zu minimieren. Der anschließende quantitative Studienteil zeigte, dass beispielsweise fast alle Teilnehmerinnen (99,3%) E-Zigaretten mit Nikotin als Bedrohung für die Gesundheit des Ungeborenen empfanden. Die am häufigsten wahrgenommene Barriere war gesundheitsbezogen (96,6%), während der am häufigste wahrgenommene Nutzen in der Reduzierung der Tabakzigaretten (31,8%) lag. Wir stellten fest, dass insbesondere die wahrgenommenen Vorteile nach dem Nutzerstatus von Tabak- und E-Zigaretten variierten.

Schlussfolgerungen Im Kontext zukünftiger Präventionsmaßnahmen sollten potenzielle Gesundheitsrisiken und die umstrittene Wirksamkeit der E-Zigarette als Raucherentwöhnungsmittel berücksichtigt und kritisch diskutiert werden.

Schlüsselwörter: elektrische Zigarette, Schwangerschaft, Risikowahrnehmung, Health-Belief-Modell, Online-Foren, Mixed-Methods

Abbreviations

- HBM

Health Belief Model

- IHBM

Integrated Health Belief Model

- TPB

Theory of Planned Behavior

Introduction

In the last decade, e-cigarettes have become popular, especially among younger people 1 . The use of e-cigarettes has spread, even among pregnant women. International research studies estimate that the prevalence of e-cigarette use in pregnancy is between 0.5 and 15% 2 , 3 , 4 . E-cigarette use in pregnancy is a relevant health hazard for pregnant women and fetuses alike 5 , 6 , 7 : e-cigarettes often contain nicotine, a fetal toxin 8 , 9 . In addition, e-cigarettes may contain other potential fetal toxins including carcinogenic and mutagenic substances or heavy metals 10 . Previous animal studies suggest that e-cigarette use during pregnancy may be associated with epigenetic, organic 11 , 12 , 13 and pulmonary 11 , 14 , 15 health risks for the fetus. Reputable prevention organizations warn against using e-cigarettes in pregnancy 16 , 17 .

Thus, examining the risk perceptions and health beliefs with regard to the use of e-cigarettes during pregnancy is an important starting point for prevention. According to commonly used behavior models, risk perceptions and their underlying assumptions are central predictors for health or pathogenic behaviors 18 , 19 . In the Integrated Health Belief Model (IHBM), which combines elements of frequently used behavior models (the Health Belief Model (HBM) 19 and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) 18 ), the intention to perform a behavior is predicted based on perceived threats, perceived barriers, perceived benefits, attitudes and perceived norms, and perceived self-efficacy. The IHBM was adapted and applied in a study by Case et al. 20 on e-cigarette use among college students. Applying the IHBM in the context of pregnancy seems useful, since the risk perceptions of pregnant women could deviate from those of the general population. Pregnant women might consider the risks for their unborn child when deciding whether or not to use e-cigarettes 21 . Previous studies have indicated that in addition to health-related factors which are incorporated in the HBM, normative factors (as postulated in the TPB) are relevant predictors of tobacco cigarette use 22 .

Only some aspects of risk perceptions about e-cigarette use in pregnancy have been researched so far. Some studies have examined whether pregnant women (or women of childbearing age) perceive e-cigarette use to be harmful to themselves or the unborn child 3 , 4 , 23 , 24 . Other studies have reported on the reasons cited for e-cigarette use during pregnancy, such as fewer perceived health risks compared to tobacco cigarettes or as an aid to stop smoking 3 , 4 , 23 , 24 . Qualitative studies have identified perceived barriers and norms associated with e-cigarette use in pregnancy 4 , 25 , 26 . However, to our knowledge, only individual elements of the HBM have been used to understand the risk perceptions of e-cigarette use during pregnancy, and not the HBM in its entirety.

The primary objective of this paper was to advance our current knowledge about risk perceptions with regard to e-cigarette use during pregnancy. Accordingly, our first aim was to identify and characterize the constructs of risk perceptions about e-cigarette use during pregnancy, based on the IHBM. Our second aim was to identify whether risk perceptions of e-cigarette use during pregnancy vary according to e-cigarette user status. Since previous studies have shown that e-cigarette use in pregnancy occurs primarily among pregnant smokers 21 , our third aim was to identify differences in risk perception according to tobacco cigarette user status.

Methods

Research design: a mixed methods study

In our ST udy on E -cigarettes and P regnancy (STEP) we mainly used a sequential exploratory mixed methods approach to get a comprehensive understanding of the risk perceptions associated with e-cigarette use in pregnancy ( Fig. 1 ). The defining characteristics of our sequential mixed methods design was that the qualitative part would be used to develop the questionnaire for the subsequent quantitative part of the study 27 . We also compared the results of the qualitative part with the results of the quantitative part, along with identified themes in a side-by-side joint display 27 . The mixed methods design has been extensively described in our previously published study protocol in this journal 24 , and we therefore only provide a brief description of the qualitative and quantitative study parts below.

Fig. 1.

Mixed methods approach. Description of the procedure and methods of the mixed methods study.

Qualitative study part

In our study, the qualitative part of the study helped to identify theory-based elements of risk perceptions of e-cigarette use during pregnancy. Our qualitative study part used a netnographic approach which analyzed threads in various online discussion forums (online communities) 28 . To do this, we identified German-language online discussion threads addressing e-cigarette use in pregnancy and analyzed their contents using the IHBM.

To identify German-language online forum threads on e-cigarette use during pregnancy, the first author conducted an extensive and multi-step search using the market-leading internet search engine Google (period studied: April to June 2017). To avoid bias caused by user data or online advertising, we did not include recommended links or paid advertisements. We used the internal search function to identify relevant threads within the identified online forums. To analyze the identified threads, we used a qualitative content analysis approach as described by Mayring 29 , 30 . Detailed information on this multi-step search and the qualitative analysis process can be found in our previously published study protocol 24 . In this paper we present an overview of the identified main constructs and themes perceived threats, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, attitudes and perceived norms (see 31 for details).

Quantitative study part

In the subsequent quantitative part of our study, we developed a standardized questionnaire. Our previously published study protocol describes the questionnaire development process and pretesting of the questionnaire in detail 24 .

Data collection

The developed questionnaire was administered to pregnant women attending the Asklepios Klinik Barmbek in Hamburg, Germany, between 4th April 2018 and 11th January 2019. This clinic is a large obstetric hospital with more than 3000 births every year and a broad catchment area in the city of Hamburg and beyond. Pregnant women were recruited during the standard birth registration interview, which was carried out by midwives in the clinic 24 .

Instruments and measures

Perceived threats and attitudes about the harmfulness of e-cigarettes were measured using an assessment of perceived absolute harms 32 , the perceived relative/comparative harms of e-cigarettes with and without nicotine for pregnant women and unborn children 2 , 33 , and the perceived specific health risks of e-cigarette use during pregnancy for pregnant women 34 and unborn children. We also measured the overall perceived threats of the aforementioned potential health risks.

Perceived benefits were measured using the question: “From your point of view, what are the benefits of e-cigarette use during pregnancy?” Participants could choose between several listed potential benefits which included using e-cigarettes to stop smoking or facilitate smoking cessation, harm reduction, and other benefits 32 , 35 , 36 .

As with the perceived benefits, we also measured perceived barriers . The list of potential barriers to choose from were health-related, related to cessation of smoking and addiction, and a number of other perceived barriers 26 .

In addition to the above-mentioned aspects about harmfulness, we measured the overall attitudes of the participants towards the use of e-cigarettes by pregnant women in general and as an alternative to tobacco cigarettes.

Perceived norms were measured by focusing on the acceptability of e-cigarettes to partners and friends.

The questionnaire included questions on the use of tobacco and e-cigarettes in the year before becoming pregnant and during the current pregnancy 37 . Based on this information, we developed two variables to reflect tobacco and e-cigarette user status (1 = nonuser, 2 = former user, 3 = current user).

To describe our sample, we collected data on sociodemographic characteristics such as age, using an open-ended question. We used the answers to create the three categories “18 to 29”, “30 to 34”, “> 34 years”. We also measured the level of education and created the categories “low”, “middle” and “high”. We evaluated immigrant background using the definition developed by Schenk et al. 38 . We additionally included indicators for the week of pregnancy and understanding/knowledge of e-cigarettes.

Quantitative analysis

First, we carried out a descriptive analysis of the items within the constructs “perceived threats/attitudes towards harmfulness”, “perceived benefits”, “perceived barriers”, “overall attitudes” and “perceived norms”. In a second and third step, we examined whether risk perceptions vary according to the participantsʼ e-cigarette and tobacco cigarette user status by performing a two-sided χ 2 test/Fisherʼs exact test.

Results

Qualitative results

We were able to identify 1552 posts in 25 threads from a total of 14 online forums as relevant for our analysis 24 .

Table 1 provides an overview of the identified constructs as well as their underlying aspects. Perceived threats of e-cigarette use during pregnancy were severe nicotine-related health risks for the pregnant woman and unborn child such as addiction, oxygen deficiency, and sudden infant death (a). The perception of threats included the potential health risks of additional ingredients resulting in lung damage or cancer (b). The perceived threats of e-cigarettes were partially diminished by the comparison with the harmfulness of tobacco cigarettes (c). However, the perceived threats of e-cigarette use during pregnancy seemed to vary, due to the lack of knowledge and research studies (d). Perceived benefits included harm reduction (e), facilitation of and support for smoking cessation (f), and financial benefits (g), while perceived barriers included lack of satisfaction (especially for e-cigarettes without nicotine) (h) and social stigma (i). Attitudes included positive and negative attitudes about e-cigarette use during pregnancy and were described in relation to the harmfulness of e-cigarettes in general, and compared with tobacco cigarettes. While there was uniformity regarding the nonuse of e-cigarettes during pregnancy in general (j), there were partially positive attitudes with regard to e-cigarette use as an alternative to using tobacco cigarettes during pregnancy (k). The identified themes for perceived norms were the attitudes and behavior in the pregnant womanʼs social environment (e.g., her partner) (l) as well as the recommendations of medical providers (m).

Table 1 Themes of IHBM constructs and selected quotes related to risk perceptions of e-cigarette use during pregnancy in 25 online discussion threads, adapted by Schilling et al. 31 .

| Identified themes of IHBM constructs | Selected quotes |

|---|---|

| […] Smileys within the text/aspects added by the researcher for clarification. T = number of the associated thread; year of the post. | |

| Perceived threats | |

| Severe nicotine-related health risks (a) | “Nicotine is an addictive drug and a neurotoxin, which of course can be transmitted to the unborn child. Thatʼs why I would personally abstain from nicotine during pregnancy!” (T20, 2017) |

| Potential health risks of additional ingredients (b) | “Even if you smoke without nicotine, there are toxins that are not good for your lungs and certainly not for the baby.” (T11, 2016) |

| Relative risks (c) | “Whether it is harmful to the child has not been proven yet, but what has been proven is that it is healthier, contains 3800 fewer toxins and you cannot smoke passively, etc.” (T5, 2012) |

| Lack of knowledge and research studies (d) | “Even those without nicotine contain chemicals and nobody knows what the long-term consequences will be!” (T3, 2012) |

| Perceived benefits | |

| Harm reduction (e) | “Vaping without nicotine is 10 times better than smoking. But of course, you should not vape during pregnancy either. But vaping is an option to move away from normal cigarettes towards no cigarettes.” (T1, 2011) |

| Possibility and facilitation of smoking cessation (f) | “Yes, I had already thought about e-cigarettes. It would be ideal, the habit stays, but thereʼs no more nicotine.” (T7, 2014) |

| Financial benefits (g) | “Good luck to anyone who wants to live healthier and wants to save a lot of money at the same time.” (T2, 2011) |

| Perceived barriers | |

| Lack of satisfaction (h) | “Although I donʼt smoke, cigarettes without nicotine, isnʼt that like drinking without alcohol? – Do you think that will satisfy your cravings?” (T22, 2012) |

| Social stigma (i) | “I would say ‘stop that’ [e-cigarette use during pregnancy] is the general answer. [Evil smiley] Be happy you havenʼt been put through the wringer yet!” (T11, 2016) |

| Attitudes | |

| Negative attitudes (j) | “As far as I know, this alternative to ‘normal’ smoking is very controversial. In my opinion, one should completely leave it alone during pregnancy!” (T15, 2017) |

| Positive attitudes (k) | “It is certain that not vaping or smoking is always better! […] But vaping without nicotine is still 1000 times better than smoking! ” (T17, 2011) |

| Perceived norms | |

| Attitudes and behavior in the social environment (l) | “My husband is a chemist and looked at the ingredients. He says thatʼs a good alternative for pregnant women.” (T11, 2016) |

| Recommendations of medical providers (m) | “Hey, in my last pregnancy, I could not stop that s*** smoking, therefore the chief physician in the hospital recommended that I use e-cigarettes without nicotine, stating that it is healthier than normal cigarettes.” (T11, 2016) |

Quantitative results

Sample characteristics

In the study period, 2092 pregnant women registered to give birth in the hospital. A total of 575 pregnant women completed the informed consent forms and the questionnaire (response rate: 27.5%) 24 . Of these, 540 participants fully answered the questions about their consumption of tobacco and e-cigarette use and were included in the subsequent analysis. On average, participants were 32.27 (SD 4.68) years old and in their 32.29 week of pregnancy (SD 2.75). Most of the surveyed participants had a high level of education (68.9%), and more than a quarter had an immigrant background (26.2%). All in all, 8.7% (26.5%) of the participants used tobacco cigarettes during pregnancy (before pregnancy). Six out of ten (62.3%) participants who knew about e-cigarettes before participating in the study (96.6%) were aware that e-cigarettes could contain nicotine, and 7.8% used e-cigarettes before pregnancy. Less than one percent used e-cigarettes during pregnancy (0.4%).

Descriptive and bivariate results

Perceived threats/health-related attitudes

Nearly all (99%) participants agreed that e-cigarettes with nicotine are harmful to pregnant women and the unborn child. Eight out of ten participants agreed that e-cigarettes without nicotine are harmful to the health of pregnant women (82.1%) and the unborn child (84.2%). Almost one fifth of the participants agreed that e-cigarettes are less harmful to the health of pregnant women (24.6%) and unborn children (21.7%) than tobacco cigarettes. A lower oxygen supply was the most frequently perceived potential health risk for the unborn child (89.3%). Addiction was the most commonly perceived health risk for pregnant women (86.2%). Current users of tobacco cigarettes agreed less often that they would feel threatened by the potential health risks of e-cigarettes if they used them during pregnancy (p = 0.002) ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 Risk perceptions about e-cigarette use in pregnancy among 540 surveyed pregnant women. Results of the quantitative part of the STEP.

| Construct/Items | Total (n = 540) | E-cigarette use | Tobacco cigarette use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (n = 498) | Former (n = 40) | None (n = 397) | Former (n = 96) | Current (n = 47) | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Percentages are based on valid cases * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.001 1 Due to the small number of cases, we did not calculate using Pearson χ 2 test/Fisherʼs exact test. 2 ≥ 25% of expected frequencies less than 5 3 Participants without a partner were excluded (n = 517). | ||||||

| Perceived threats/attitudes towards harmfulness | ||||||

| Perceived absolute harms | ||||||

|

99.1 | 99.2 | 97.6 | 99.2 | 99.0 | 97.9 |

|

82.1 | 82.6 | 76.2 | 83.4 | 84.0 | 67.4* |

|

99.3 | 99.4 | 97.6 | 99.5 | 98.9 | 97.9 |

|

84.2 | 84.9 | 75.6 | 85.7 | 82.4 | 75.0 |

| Perceived relative/comparative harms | ||||||

|

24.6 | 24.6 | 23.8 | 23.8 | 29.5 | 21.3 |

|

21.7 | 21.7 | 21.4 | 20.9 | 28.7 | 14.9 |

| Perceived specific health risks | ||||||

|

86.2 | 87.1 | 76.2 | 87.6 | 85.3 | 76.6 |

|

85.8 | 86.6 | 76.2 | 88.6 | 83.9 | 66.0** |

|

83.2 | 84.0 | 73.8 | 85.1 | 82.1 | 70.2* |

|

89.3 | 89.7 | 85.4 | 88.8 | 90.3 | 91.5 |

|

87.3 | 87.7 | 83.3 | 88.4 | 82.3 | 89.1 |

|

86.4 | 86.4 | 85.7 | 85.3 | 86.5 | 95.7 |

| Overall perceived threats | ||||||

|

93.5 | 94.3 | 84.4* | 95.3 | 92.6 | 80.0* |

| Perceived benefits | ||||||

|

31.8 | 31.2 | 39.0 | 29.3 | 36.2 | 42.6 |

|

28.7 | 27.4 | 43.9* | 26.1 | 31.9 | 42.6* |

|

26.7 | 25.9 | 36.6 | 25.1 | 28.7 | 36.2 |

|

20.3 | 20.0 | 24.4 | 19.2 | 19.1 | 31.9 |

|

19.2 | 17.5 | 39.0* | 17.1 | 18.1 | 38.3* |

|

49.6 | 51.2 | 31.7* | 51.2 | 47.9 | 40.4 |

| Perceived barriers | ||||||

|

96.6 | 96.7 | 95.2 | 96.4 | 96.9 | 97.8 |

|

89.1 | 88.8 | 92.9 2 | 90.3 | 87.5 | 82.6 |

|

85.5 | 85.1 | 90.5 | 84.4 | 88.5 | 89.1 |

|

72.0 | 72.4 | 66.7 | 72.6 | 77.1 | 56.5* |

|

65.4 | 65.5 | 64.3 | 62.6 | 72.9 | 73.9 |

| Attitudes | ||||||

|

98.7 | 99.2 | 92.9 | 98.5 | 98.9 | 100.0 |

|

87.3 | 87.5 | 85.7 | 89.3 | 82.3 | 80.9 |

| Perceived norms | ||||||

|

92.7 | 93.2 | 86.5 | 94.1 | 92.1 | 81.4* |

|

84.5 | 84.5 | 84.6 | 84.8 | 86.0 | 78.7 |

Perceived benefits

The most commonly perceived benefit was that e-cigarettes could help to reduce the consumption of tobacco cigarettes (31.8%), followed by other benefits related to facilitating smoking cessation, quitting smoking altogether, and other, less important health risks. Perceived benefits varied somewhat according to the participantsʼ tobacco and e-cigarette user status.

Perceived barriers

The most commonly perceived barriers were health-related (e.g., “E-cigarettes can harm the health of pregnant women and unborn children” [96.6%]) and did not vary significantly according to e-cigarette or tobacco cigarette user status.

Attitudes

Nearly all participants agreed that pregnant women should not use e-cigarettes during pregnancy (98.7%). Fewer participants believed that pregnant women should not use e-cigarettes as an alternative to tobacco cigarettes (87.3%) ( Table 2 ).

Perceived norms

Around nine out of ten partners (92.7%) and friends (84.5%) of the participants did not reject e-cigarette use during pregnancy. The perception of norms varied according to the participantsʼ tobacco and e-cigarette user status.

Mixed methods results

The quantitative results confirmed the findings of the qualitative part of the study (cf. the detailed side-by-side comparison in Table 3 ). A very commonly perceived benefit in the qualitative part was “possibility and facilitation of smoking cessation”. The most frequently mentioned perceived benefits in the quantitative part of the study were that e-cigarettes could help to reduce/stop the consumption of tobacco cigarettes and reduce stress when quitting smoking.

Table 3 Mixed methods analysis: side-by-side comparison of qualitative and quantitative results of the STEP.

| Theme | Qualitative results (analysis of 1552 posts from 25 online discussion threads) | Quantitative results (standardized survey of 540 pregnant women) |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived threats/ attitudes towards harmfulness |

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceived benefits |

|

|

| Perceived barriers |

|

|

| Attitudes |

|

|

| Perceived norms |

|

|

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study using an IHBM and combining qualitative and quantitative methods to analyze risk perceptions and health beliefs about e-cigarette use during pregnancy.

The perceived threat of e-cigarettes, especially e-cigarettes containing nicotine, was high in both the qualitative and the quantitative parts of our study. Nevertheless, in accordance with previous studies, both parts showed that e-cigarette use was perceived as a less serious health threat than tobacco cigarette use by a minority of the surveyed women 21 , 32 . However, the percentages identified in our study differ from the percentages reported in previous studies 32 , 35 . The study by Mark et al. 32 showed that 43% of a cohort of pregnant women from the U. S. believed that e-cigarettes were less harmful to unborn children than tobacco cigarettes. These different percentages seemed to be in line with the observed increase in the perceived harmfulness of e-cigarettes among the general population 39 .

In line with this, our quantitative results show that health-related aspects were perceived as the main barriers to using e-cigarettes during pregnancy. Our findings contradict previous indications that pregnant smokers might switch to e-cigarettes during pregnancy because the associated health risks are assumed to be lower 2 , 3 , 23 . Instead, the lack of knowledge about the health risks for the fetus seemed to be a highly relevant concern and therefore a barrier to pregnant women using e-cigarettes in both our qualitative and quantitative study parts. The threat to fetal health could be an explanation of why pregnant tobacco cigarette users did not switch to e-cigarettes.

In addition to perceived health-related barriers, the most commonly cited barriers were the potential for addiction, the efficacy of e-cigarettes as a tool to stop smoking and the difficulties in stopping smoking using e-cigarettes (especially if they did not contain nicotine). (For studies on e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation help in the general population, see 40 ).

In contrast, our results showed that commonly perceived benefits of e-cigarettes among current smokers included reducing the amount they smoked or even smoking cessation with the help of e-cigarettes. Previous studies have shown that pregnancy is an opportunity for many women to quit smoking or reduce the number of tobacco cigarettes they smoke 41 . However, half of the pregnant smokers who smoked just before the beginning or during pregnancy continue to smoke during pregnancy 42 . The belief that e-cigarettes are a smoking cessation aid could lead pregnant women to reach for e-cigarettes.

Reducing the stress of smoking cessation with the help of e-cigarettes was a central perceived benefit in our study. Previous studies showed that some pregnant smokers evaluated quitting nicotine during pregnancy as stressful and dangerous for the fetus 25 , 43 . Pregnant smokers were afraid of harming their child by the sudden withdrawal of nicotine and the accompanying stress of sudden withdrawal 25 , 44 . Similar to stress reduction, satisfying cravings by using e-cigarettes was an important perceived benefit. Smoking cessation during pregnancy frequently fails, due to the addictive potential of nicotine 45 , 46 . The perceived possibility of reducing stress and cravings and having a nicotine substitute may support the decision to use e-cigarettes containing nicotine for smoking cessation during pregnancy – despite the perceived health risks and the controversial efficacy of e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid. These results underline how important it is to take stress and stress reduction into consideration in the context of smoking cessation during pregnancy in clinical practice.

In line with these perceived benefits and in agreement with previous studies, we showed that some pregnant women had positive attitudes towards the use of e-cigarettes as an alternative to tobacco cigarettes 21 . This attitude was present in about 20% of tobacco cigarette users. These pregnant smokers might be vulnerable to using e-cigarettes.

The decision to use e-cigarettes may also be influenced by the pregnant womanʼs partner, family or medical providers. A recently published study indicated that the decision to use e-cigarettes during pregnancy was often an impulse decision, based on recommendations made by friends, family or medical providers 26 . Similarly, some forum users in our study reported getting recommendations to use e-cigarettes during pregnancy from partners, friends or medical providers. A previous study by England et al. 47 found that 14% of obstetricians and gynecologists are of the opinion that e-cigarettes have no health effects. Since perceived norms play an important role in decisions to perform a behavior 19 , future prevention strategies need to address misleading messages.

Strengths and limitations

Given the increasing rates of e-cigarette use worldwide and the known harmful effects of nicotine on fetal development, the topic of our manuscript is timely and has a high public health relevance. Our mixed methods study is innovative, as it examines risk perceptions of e-cigarette use during pregnancy from different perspectives and provides in-depth information on various constructs of risk perception. In addition, we based our analysis on an integrated Health Belief Model, another innovative approach. However, our study has several limitations, which have been extensively described in our previous published study protocol 24 . We therefore only describe the most important limitations of our study below.

Qualitative study part

As is common in qualitative research, the aim is not to produce representative results. Instead, in this part of the study we were interested in the range of underlying aspects of risk perceptions regarding e-cigarette use during pregnancy. Online discussion threads are suitable for this, because they allow anonymous exchanges of opinions, making them predestined to explore stigmatized and taboo topics such as tobacco and e-cigarette use during pregnancy 23 , 25 , 48 . However, it must be acknowledged that the qualitative data was collected in 2017, and thus may not represent current opinions about e-cigarette use during pregnancy.

Quantitative study part

A main limitation of the quantitative part of our study is its representativeness. Our results cannot be generalized to all pregnant women in Germany, since the study sample was based on a single clinic in Hamburg (cf. 24 for more information). Another important limitation is the sample size. The sample sizes in some cross tables did not meet the requirements for statistical tests. In addition, the number of participants who used e-cigarettes during pregnancy was too small to evaluate whether the constructs of risk perception we identified predict current e-cigarette use during pregnancy.

Conclusion

Our innovative and integrative mixed methods approach revealed a complex picture of the IHBM constructs “perceived threats”, “perceived benefits”, “perceived barriers”, “attitudes and perceived norms” regarding e-cigarette use during pregnancy. Our innovative, netnographic, qualitative and traditionally quantitative study found a considerable number of perceived threats and various perceived barriers and negative attitudes. However, these negative perceptions were accompanied by various perceived benefits, especially among current users of tobacco cigarettes. The multiple health risks of e-cigarette use during pregnancy need to be critically addressed by obstetricians, gynecologists and midwives and also in future smoking cessation programs for pregnant smokers.

Declarations

Ethical approval and patient consent

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Mannheim (Heidelberg University; 2017-505N-MA) and the Ethics Committee of the Hamburg Medical Chamber (MC-178/17).

As is common and ethically tenable in research activities using online forums, forum users were not informed about their posts being used for research purposes. The threads were publicly available, and no registration was required to read the threads in the online forums 24 .

In the quantitative section of the study, participants received a survey package providing information about the objectives, procedure, risks, benefits, study contacts and data security. In addition, participants were assured that participation was voluntary, and that non-participation would have no negative consequences and no impact on their further treatment at the hospital. Moreover, the participants had the opportunity to withdraw their consent. Only participants who gave their consent were included in the study 24 .

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Christoph Karlheim and Sosan Burhany for assisting in the qualitative coding procedure, as well as Heide-Rose Rahlf for assisting in the administrative process during the quantitative section. The authors also wish to thank Aylin Evin for her linguistic revision of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Schneider S, Görig T, Schilling L. E-Zigaretten in aller Munde? – Aktuelle repräsentative Daten zur Nutzung unter Jugendlichen und Erwachsenen. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2017;142:156–166. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-111741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhandari N R, Day K D, Payakachat N. Use and risk perception of electronic nicotine delivery systems and tobacco in pregnancy. Womens Health Iss. 2018;28:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner N J, Camerota M, Propper C. Prevalence and perceptions of electronic cigarette use during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:1655–1661. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2257-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whittington J R, Simmons P M, Phillips A M. The use of electronic cigarettes in pregnancy: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2018;73:544–549. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.England L J, Bunnell R E, Pechacek T F. Nicotine and the developing human: a neglected element in the electronic cigarette debate. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li G, Saad S, Oliver B G. Heat or Burn? Impacts of intrauterine tobacco smoke and e-cigarette vapor exposure on the offspringʼs health outcome. Toxics. 2018;6:E43. doi: 10.3390/toxics6030043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider S, Schilling L. E-Zigaretten in der Schwangerschaft – ein unterschätztes Risiko? Frauenarzt. 2019;60:90–92. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spindel E R, McEvoy C T. The role of nicotine in the effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on lung development and childhood respiratory disease. Implications for dangers of e-cigarettes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:486–494. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-2013PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams M, Villarreal A, Bozhilov K. Metal and silicate particles including nanoparticles are present in electronic cigarette cartomizer fluid and aerosol. PloS One. 2013;8:e57987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchiyama S, Ohta K, Inaba Y. Determination of carbonyl compounds generated from the e-cigarette using coupled silica cartridges impregnated with hydroquinone and 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, followed by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Sci. 2013;29:1219–1222. doi: 10.2116/analsci.29.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Li G, Chan Y L. Maternal e-cigarette exposure in mice alters DNA methylation and lung cytokine expression in offspring. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;58:366–377. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0206RC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palpant N J, Hofsteen P, Pabon L. Cardiac development in zebrafish and human embryonic stem cells is inhibited by exposure to tobacco cigarettes and e-cigarettes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suter M A, Mastrobattista J, Sachs M. Is there evidence for potential harm of electronic cigarette use in pregnancy? Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2015;103:186–195. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGrath-Morrow S A, Hayashi M, Aherrera A. The effects of electronic cigarette emissions on systemic cotinine levels, weight and postnatal lung growth in neonatal mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider S, Schilling L. Sind E-Zigaretten eine Alternative für rauchende Schwangere? Atemwegs Lungenkr. 2019;45:232–238. [Google Scholar]

- 16.DKFZ . Heidelberg: Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum; 2013. Elektrische Zigaretten – Ein Überblick. [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control . Moskau: Conference of the parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; 2014. Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. New York: Prentice-Hall; 1980. Understanding Attitudes and predicting social Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenstock I M. The Health Belief Model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:354–386. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Case K, Crook B, Lazard A. Formative research to identify perceptions of e-cigarettes in college students: implications for future health communication campaigns. J Am Coll Health. 2016;64:380–389. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2016.1158180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCubbin A, Fallin-Bennett A, Barnett J. Perceptions and use of electronic cigarettes in pregnancy. Health Educ Res. 2017;32:22–32. doi: 10.1093/her/cyw059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galvin K T. A critical review of the Health Belief Model in relation to cigarette smoking behaviour. J Clin Nurs. 1991;1:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kahr M K, Padgett S, Shope C D. A qualitative assessment of the perceived risks of electronic cigarette and hookah use in pregnancy. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1273. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2586-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schilling L, Schneider S, Maul H. STudy on E-cigarettes and Pregnancy (STEP) – Study protocol of a mixed methods study on risk perception of e-cigarette use during pregnancy and sample description. Geburtsh Frauenheilkd. 2020;80:66–75. doi: 10.1055/a-1061-7288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wigginton B, Gartner C, Rowlands I J. Is it safe to vape? Analyzing online forums discussing e-cigarette use during pregnancy. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowker K, Orton S, Cooper S. Views on and experiences of electronic cigarettes: a qualitative study of women who are pregnant or have recently given birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:233. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1856-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creswell J. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE; 2014. A concise Introduction to mixed Methods Research. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozinets R V. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2010. Netnography. Doing ethnographic Research online. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayring P. Weinheim: Beltz; 2008. Neue Entwicklungen in der qualitativen Forschung und der qualitativen Inhaltsanalyse; pp. 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayring P. Weinheim: Beltz; 2002. Einführung in die qualitative Sozialforschung. Eine Anleitung zu qualitativem Denken. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schilling L, Schneider S, Karlheim C. Perceived threats, benefits and barriers of e-cigarette use during pregnancy. A qualitative analysis of risk perception within existing threads in online discussion forums. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2019.102533. Midwifery. 2019;79:102533. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2019.102533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mark K S, Farquhar B, Chisolm M S. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of electronic cigarette use among pregnant women. J Addict Med. 2015;9:266–272. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi K, Forster J L. Beliefs and experimentation with electronic cigarettes: a prospective analysis among young adults. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:175–178. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider S, Görig T, Diehl K. Die E-Zigarette – Bundesweite Daten zu Bekanntheit, Nutzung und Risikowahrnehmung. ASU. 2015;50:818–823. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashford K, Rayens E, Wiggins A T. Advertising exposure and use of e-cigarettes among female current and former tobacco users of childbearing age. Public Health Nurs. 2017;34:430–436. doi: 10.1111/phn.12334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oncken C, Ricci K A, Kuo C L. Correlates of electronic cigarettes use before and during pregnancy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19:585–590. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Institut für Epidemiologie und Medizinische Biometrie SPATZ Studie. Die Säulen 2018. Accessed February 20, 2019 at:http://www.ulmer-forschen.de/die-saeulen/10-ulmer-spatz-gesundheitsstudie/die-studie

- 38.Schenk L, Bau A M. Mindestindikatorensatz zur Erfassung des Migrationsstatus – Empfehlungen für die epidemiologische Praxis. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitschutz. 2006;49:853–860. doi: 10.1007/s00103-006-0018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang J, Feng B, Weaver S R. Changing perceptions of harm of e-cigarette vs. cigarette use among adults in 2 US National Surveys from 2012 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e191047. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Public Health England Research and analysis. Evidence review of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products 2018: executive summary 2018. Accessed December 20, 2018 at:https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/e-cigarettes-and-heated-tobacco-products-evidence-review/evidence-review-of-e-cigarettes-and-heated-tobacco-products-2018-executive-summary

- 41.Tong V T, Dietz P M, Farr S L. Estimates of smoking before and during pregnancy, and smoking cessation during pregnancy: Comparing two population-based data sources. Public Health Rep. 2013;128:179–188. doi: 10.1177/003335491312800308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.IFF Research . Dundee, UK: The Information Centre for Health and Social Care and the UK Health Departments; 2011. Infant Feeding Survey 2010. Early Results. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flemming K, McCaughan D, Angus K. Qualitative systematic review: barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation experienced by women in pregnancy and following childbirth. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:1210–1226. doi: 10.1111/jan.12580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flemming K, Graham H, McCaughan D. The barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation experienced by womenʼs partners during pregnancy and the post-partum period: a systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:849. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2163-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ebert L, Fahy K. Why do women continue to smoke in pregnancy? Women Birth. 2007;20:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gillies P A, Madeley R J, Power F L. Why do pregnant-women smoke. Public Health. 1989;103:337–343. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(89)80003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.England L J, Anderson B L, Tong V T. Screening practices and attitudes of obstetricians-gynecologists toward new and emerging tobacco products. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:6950–6.95E9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Triandafilidis Z, Ussher J M, Perz J. An intersectional analysis of womenʼs experiences of smoking-related stigma. Qual Health Res. 2017;27:1445–1460. doi: 10.1177/1049732316672645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]