Abstract

Objective:

Examine whether personal identity confusion and ethnic identity, respectively, moderate and/or mediate the relationship between perceived discrimination (PD) and depressive symptoms (DS) in eight ethnic-generational groups.

Method:

The sample consisted of 9665 students (73% women; mean age 20.31) from 30 colleges and universities from around the United States. Cross-sectional data were gathered through a confidential online survey.

Results:

Across groups, PD and ethnic identity levels varied, while identity confusion levels were mostly similar. Neither identity confusion nor ethnic identity moderated the PD-DS relationship for any groups. However, identity confusion was a partial mediator for immigrant and nonimmigrant Hispanic/Latino(a) and White/European American participants. Identity confusion also suppressed the PD-DS relationship for Black/African American participants.

Conclusions:

Results highlight the need for additional research on identity confusion’s role in the PD-distress link and the importance of addressing ethnicity and generation status when examining the effects of PD on college students’ mental health.

Keywords: perceived discrimination, ethnic identity, personal identity, depression, ethnic minorities, generation

Empirical research findings consistently suggest that perceived ethnic discrimination (PD) is associated with poorer psychological health outcomes for ethnic minorities, including ethnic minority college students (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). This association is theorized to be a complex one that can be influenced by multiple cultural and personal factors (Harrell, 2000). In particular, ethnic identity has emerged as a potential protective factor against discrimination (moderator; Phinney, 1990) and as the mechanism through which discrimination impacts mental health (mediator; Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999). However, inconsistent findings on ethnic identity as a moderator and a mediator in the discrimination-distress link in college student samples suggest further examination is needed with this population (Brondolo, ver Halen, Pencille, Beatty, & Contrada, 2009; Lee, 2003; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009).

Additionally, scholars have called for more research on other aspects of personal identity, such as identity confusion, which might affect PD outcomes in college students (e.g., Schwartz, 2005). Therefore, we examined the moderation and mediation effects of identity confusion and ethnic identity on the relationship between PD and depressive symptoms (DS) in a national college student sample. Whereas past research has tended to focus on specific ethnic groups, we compare these relationships across ethnic groups (i.e., Asian Americans, Black/African Americans, Hispanic/Latinos(as), and White/European Americans), as well as between generation status (i.e., foreign-born/immigrant vs. U.S.-born/nonimmigrants).

Perceived Discrimination

In the United States, there has been a significant increase in the ethnic minority population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011) and the visibility of successful ethnic minorities (e.g., President Barack Obama), leading some pundits to propose that discrimination is no longer a problem (see CNN video at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NTixCXmrezY). Experiences of ethnic minorities challenge this perception, with research showing PD is a frequent occurrence (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). Findings with college students also consistently suggest that experiences of PD are positively associated with DS for Asian American (Lee, 2003; Wei, Heppner, Ku, & Liao, 2010), Black/African American (Banks & Kohn-Wood, 2007), and Hispanic/Latino(a) groups (Huynh, Devos, & Dunbar, 2012). Similar results between PD and DS have been found with community samples across ethnic groups (Asian American; Yip, Gee, & Takeuchi, 2008; Black/African American women: Settles, Navarrete, Pagano, Abdou, & Sidanius, 2010; Hispanic/Latino(a): Todorova, Falcón, Lincoln, & Price, 2010). In addition to DS, evidence with college student and community samples suggests relationships between PD and reduced wellbeing, life-satisfaction, and cardiovascular health, and increased psychological distress, anxiety, and blood pressure for a variety of ethnic minority groups (see Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009, for a recent meta-analysis of this literature).

A stress response model has been used by many scholars to frame how discrimination relates to negative outcomes, such that perceptions of personal or group discrimination are viewed as stressful to individuals, resulting in negative health responses (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Harrell, 2000). As with general stress, understanding the pathways through which PD affects mental health is the necessary next step toward developing individual-level interventions that would mitigate these harmful outcomes (Harrell, 2000). To that end, recent theoretical and empirical work has attempted to understand how identity influences the PD-psychological health relationship (Brondolo et al., 2009). Although ethnic identity has dominated the research related to psychological outcomes of PD, there are compelling conceptual arguments that suggest personal identity—in particular identity confusion—may also play a role.

Personal Identity as a Moderator/Mediator

Sixty years ago, Erikson (1950, 1968) articulated the concept of personal identity development, positing that healthy development culminated in a mostly stable and continuous view of oneself called identity synthesis. Having a coherent and consistent view of who you are, Erikson believed, was the gateway to adulthood, enabling the pursuit of such activities as mate and career selection (Erikson, 1950, 1968; Schwartz et al., 2011). Erikson also believed that identity development entails some amount of confusion and lack of clarity about one’s roles and future goals called identity confusion, with successful resolution emphasizing synthesis and not confusion (Erikson, 1950,1968; Schwartz et al., 2011). According to Erikson, this process occurs primarily during adolescence. However, Arnett (2000) argues that in contemporary Western industrialized societies, the age of personal identity development has shifted from puberty/late teens to emerging adults aged 18 to 25 years. Although there are challenges to the utility ofthe emerging adult conceptualization, the development of personal identity during this period is perceived by some to best fit those who have the financial means, time, and security to attend college but to not fit those who do not attend college (Côté & Bynner, 2008).

Building on Erikson’s theory, James Marcia (1966) created the ego identity status model which has greatly influenced empirical research on identity development in adolescence and emerging adults in college (Schwartz, 2007). Conceptually and empirically, Erikson’s notion of identity confusion is closely associated with Marcia’s diffusion status (no identity commitment after or without identity exploration), and identity synthesis is closely associated with Marcia’s achievement status (commitment after exploration; Schwartz et al., 2011). However, research suggests identity confusion and synthesis are important constructs, exclusive of identity status, that relate to mental health and behavior outcomes in college students (Schwartz, Zamboanga, Wang, & Olthuis, 2009; Schwartz, Zamboanga, Weisskirch, & Rodriguez, 2009). Specifically, in ethnic minority college student samples, identity confusion has been linked to such negative outcomes as increased depression, anxiety, and impulsivity (Schwartz, Zamboanga, Wang, et al., 2009; Schwartz, Zamboanga, Weisskirch, et al., 2009), whereas identity synthesis has been linked to such positive outcomes as decreased depression, anxiety, and impulsivity (Schwartz, 2007).

Although identity confusion’s role in the PD-DS relationship has never been tested, there are reasons to suggest a possible link. Yoder (2000) posits that experiences of PD need to be included in analyses of personal identity formation because of the profound ways such experiences can shape people’s view of themselves. Schwartz and colleagues (2005; Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones, 2006) also assert that personal identity can influence the effects of stressful experiences like PD. For example, negative mental health outcomes of PD may be exacerbated for those who are already unsure of who they are and their roles in society (identity confusion as moderator). Alternatively, experiences of PD may erode people’s sense of self, resulting in negative mental health outcomes (identity confusion as mediator). Research on the associations among identity confusion, PD, and DS in college students are needed to determine whether these assertions have empirical support.

Ethnic Identity as a Moderator/Mediator

Ethnic identity also builds on Erikson’s theory of identity development (Phinney, 1990; Phinney & Ong, 2007). The main difference between the two forms lies with focus. Whereas personal identity is related to people’s sense of who they are as individuals, ethnic identity is related to people’s sense of who they are in relation to their ethnic group and the value placed on belonging to said group (Phinney & Ong, 2007). Phinney (1990) proposes that the inverse PD-psychological health relationship may be buffered for those people who highly identify with their ethnic group (ethnic identity as moderator). Phinney and colleagues further propose that ethnic identity, like personal identity, is important to investigate in college student populations. Specifically, they suggest that, for emerging adults, the unique environment of college may encourage a “reexamination” of ethnic identity (Syed, Azmitia, & Phinney, 2007).

Phinney’s ethnic identity moderation hypothesis has been well tested with ethnic minority college students, primarily Black/African Americans and Asian Americans. To a lesser extent, the hypothesis has also been tested with Hispanic/Latino(a) college students and with ethnically homogeneous and heterogeneous community samples. Regardless of ethnicity and sample focus, some findings show support for the buffering hypothesis (Mossakowski, 2003; Sellers, Copeland-Linder, Martin, & Lewis, 2006; Wong, Eccles, & Sameroff, 2003); other findings suggest the PD-psychological health relationship may be exacerbated by high ethnic identity (Lee, 2005; Noh, Beiser, Kasper, Hou, & Rummens, 1999; Operario & Fiske, 2001; Yoo & Lee, 2009), and still others suggest no effect (Lee, 2003; Park, Schwartz, Lee, Kim, & Rodriguez, 2012; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009).

The possible mediation role of ethnic identity in PD outcomes is based in part on Social Identity Theory. This theory suggests that experiences of discrimination based on ethnic group membership will lead people to identify more closely with their ethnic group which then limits any possible negative psychological effect (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Branscombe and colleagues (1999) tested this mediation model with some success. Using an African American sample of college students and community members, they found that chronic experiences of discrimination are positively associated with ethnic identity, which, in turn, is associated with increased well-being. However, these findings were not replicated in a similar study with Asian American college students (Lee, 2003).

Collectively, these findings indicate that more evidence is needed to determine whether identity confusion and ethnic identity moderate and/or mediate the PD-DS relationship. How these relationships may vary across and within ethnic groups of college students would also provide much needed clarity.

Variations Across Ethnic Groups

Ethnic groups in the United States are perceived differently by out-group members. Research suggests that Asian Americans are perceived as “model minorities”—intelligent, academically successful, and hardworking—and as “perpetual foreigners”—non-English speakers born outside the United States (Huynh, Devos, & Smalarz, 2011; Kim, Wang, Deng, Alvarez, & Li, 2011; Wong, Lai, Nagasawa, & Lin, 1998). Black/African Americans, on the other hand, are viewed as uneducated, unmotivated, athletic, musical, and prone to violence and criminality (Czopp & Monteith, 2006; Devine & Eliott, 1995; Welch, 2007; Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000). Similar in part to stereotypes of Asian Americans and Black/African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos(as) are perceived as foreigners, non-English speakers, uneducated, and criminals; they are also stereotyped as illegal immigrants and unskilled laborers (Jones, 1991; Kao, 2000; Rivadeneyra, 2006; Welch, Payne, Chiricos, & Gertz, 2011).

Because the perceptions of ethnic groups differ, their discrimination experiences, consequences of such experiences, and ethnic group connections can also differ. These differences could partially explain the disparate findings among ethnic groups related to ethnic identity’s moderation and mediation roles in the PD-psychological health relationship. Unfortunately, inconsistencies in how PD, identity, and psychological health are measured coupled with few national studies that examine these variables in multi-ethnic college student samples are barriers to comparing findings across ethnic groups in this population.

Even within ethnic groups, PD outcomes and identity development might vary depending on influential sociocultural variables like generation status (i.e., foreign-born/immigrant, U.S.-born/nonimmigrants) (Phinney, 1990; Schwartz et al, 2006). Research supporting this difference indicates that negative outcomes of PD are greater for nonimmigrant versus immigrant Hispanic/Latino(a) individuals (Perez, Fortuna, & Alegria, 2008; Tillman & Weiss, 2009). Regarding identity, Schwartz and colleagues (2005; Schwartz et al., 2006) have noted that the influences of personal identity are likely wider than what has been empirically examined previously, particularly related to the experiences of immigrant ethnic minority groups. Specifically, compared with native-born individuals, adapting to a country different from one’s country of origin could increase foreign-born individuals’ vulnerability to identity confusion. In the United States, this adaptation process is likely further complicated for ethnic minority immigrants because of negative perceptions and growing hostility toward these groups (Schwartz et al., 2006), which may contribute to differences in ethnic identity formation across ethnic-generational groups. Generation status’s influence on ethnic minorities’ identity confusion has not been examined; however, research using an Asian American community sample does support the influence of generation status on ethnic identity, indicating that Asian American immigrants identify more with their ethnic group than their nonimmigrant counterparts (Yip et al., 2008).

Although the hypothetical and research support related to generation status differences in PD and identity are compelling, there is limited research that examines these variables across a variety of ethnic-generational groups. This lack of information makes understanding the sociocultural context of these variables difficult. Further, there are no studies that examine the moderating or mediating role of ethnic identity in the PD-DS relationship across a wide variety of ethnic-generational groups. The few studies that simultaneously address ethnicity and generation do so with one ethnic group, limiting comparisons across groups. For example. Yip and colleagues (2008) assessed the moderating effects of ethnic identity on the PD-psychological distress relationship with an immigrant and nonimmigrant Asian community sample. They found that ethnic identity did not influence the PD-distress relationship for immigrants of any age and for nonimmigrants between 18 and 30 years of age. Whether these findings can be replicated with college students and with other ethnic-generational groups has not been examined, underscoring the need for further study in this area of research.

Study Goals

Clearly, additional work needs to be done to examine empirically the theorized effect of both personal identity and ethnic identity on the psychological outcomes of PD in college students. We address this gap by testing the moderation and mediation effects of identity confusion and ethnic identity on the PD-DS relationship in a large national sample of college students. We further advance the literature by exploring these relationships across ethnic groups (i.e., Asian Americans, Black/African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos(as), and White/European Americans), as well as between generation status (i.e., foreign-born/immigrant vs. U.S.-born/nonimmigrant). This study’s diverse sample also enabled us to investigate how PD, identity confusion, and ethnic identity vary across ethnic-generational groups of college students.

Method

Participants

In this sample (N = 9665), there were four major ethnic groups: Asian American (n = 1061), Black/African American (n = 896), Hispanic/Latino(a) (n = 1527), and White/European American (N = 6181). The ethnic groups were unevenly distributed across immigrant generations, X2(3) = 1138.89, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .34. The majority of White/European American (96.2%), Black/African American (84.7%)), and Hispanic/Latino(a) (76.6%) participants were nonimmigrants, but there was a substantial minority of Asian American participants (34.4%) who were immigrants (i.e., first-generation Americans). The majority of participants were women (n = 7027 or 73%; 38 participants did not respond to the question about gender), and the ratio of men: women was unevenly distributed across ethnic groups (but not to a large extent), x2(3) = 58.01, P < .001, Cramer’s V = .08. The mean sample age was 20.31 years (SD = 3.93), and there were minimal but significant differences on age across ethnic groups, F(3) = 9.74, p < .001, partial η2 = .003. Because the gender distribution and age of the samples were minimally different, we did not control for these demographic variables in analyses reported in the Results section below.

Procedure

The study measures were administered as part of the larger Multi-Site University Study of Identity and Culture (MUSIC) online survey, which contained other assessments not reported here. Undergraduate students from 30 colleges and universities across the United States were recruited, and they were given course credit or met course requirements for their participation. See Castillo and Schwartz (this issue) for a full description of the MUSIC study procedures. Only measures pertinent to our research questions (perceived discrimination, identity confusion, ethnic identity, and depressive symptoms) are described below.

Measures

Perceived discrimination.

We used the Perceived Discrimination subscale (α = .87) from the Scale of Ethnic Experience (SEE; Malcarne, Chavira, Fernandez, & Liu, 2006) to assess perceptions of discrimination toward group (9 items) and self (2 items). The SEE was originally developed and tested in five studies with more than 3,800 college student participants from four different ethnic groups (Black/African Americans, Filipino Americans, Mexican Americans, and White/European Americans). The factor structure of the SEE was confirmed across these four ethnic groups, and there was evidence of concurrent validity with measures of ethnic identity and acculturation (see Malcarne et al. for more details about development and validation). The Perceived Discrimination subscale also has been used successfully in other studies with diverse samples, providing further evidence of validity. For instance, perceived discrimination (as measured by this subscale) partially mediated ethnic differences on sleep architecture, or the amount of time spent in each stage of sleep, between Black/African Americans and White/European Americans in a community sample (Tomfohr, Pung, Edwards, & Dimsdale, 2012). In another study using a community sample, perceived discrimination (as measured by this subscale) mediated ethnic differences on reactivity to an alpha agonist, which is indicative of blood pressure reactivity and health of the underlying cardiovascular regulatory system. between Black/African Americans and White/European Americans (Thomas, Nelesen, Malcarne, Ziegler, & Dimsdale, 2006).

Sample items from the Perceived Discrimination subscale include: “Discrimination against my ethnic group is not a problem in America” (reverse scored) and “In my life, I have experienced prejudice because of my ethnicity.” Participants rated their agreement/disagreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). After reverse-coding the appropriate items, we averaged the 11 responses for each participant, with higher scores indicating higher perceived discrimination.

Identity confusion.

Identity confusion was measured using the six identity confusion items from the Identity subscale of the Erikson Psyehosoeial Inventory Scale (EPSI; Rosenthal, Gurney, & Moore, 1981; Schwartz, Zamboanga, Wang, et al., 2009; α = .79). Sample items include: “I feel mixed up” and “I can’t decide what I want to do with my life.” Participants rated their agreement/disagreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (hardly ever true) to 5 (almost always true). We summed the six responses for each participant, with higher scores indicating higher identity confusion.

Ethnic identity.

We used the Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; 12 items; Phinney, 1992) to assess ethnic identity (α = .92). There are two subscales assessing ethnic identity exploration (extent to which one has considered the subjective meaning of one’s ethnicity) and affirmation/belonging (extent to which one feels positively about one’s ethnic group). Sample items include “I think a lot about how my life will be affected by my ethnic group membership” (exploration) and “I am happy that I am a member of the ethnic group I belong to” (affirmation/belonging). Participants rated their agreement/disagreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Although the MEIM was originally designed to yield separate subscales for ethnic identity exploration and affirmation, Phinney and Ong (2007) have reviewed studies supporting the single-factor structure of scores generated by this instrument. So for this study, we computed a composite ethnic identity score by taking the sum of the 12 responses for each participant, with higher scores indicating higher ethnic identification.

Depressive symptoms.

We used the Center for Epidemiologie Studies Depression Scale (20 items; Radloff, 1977) to assess depressive symptoms, including depressive feelings and behaviors (α = .92). Sample items include: “I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me” and “I felt sad.” Respondents rated their level of depressive symptoms during the previous seven days, including the day of the study, on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (rarely or none of the time; < I day) to 5 (most or all of the time; 5–7 days). After reverse-coding the appropriate items, we summed the 20 responses for each participant, with higher scores indicating more frequent depressive symptoms.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

To determine how reports of PD, identity confusion, ethnic identity, and DS varied across ethnicity (i.e., Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino(a), and White/European American) and generation status (i.e., immigrant and nonimmigrant), we conducted analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Results showed a small, significant main effect of ethnicity for PD, F(3, 8951) = 332.41, p < .001, partial η2 = .10; identity confusion, F(3, 8497) = 23.14, p < .001, partial η2 = .01; ethnic identity, F(3, 9030) = 22.45, P< .001, partial η2 = .01; and depressive symptoms, F(3,7593) = 6.68, P< .001, partial η2 = .003 (see Table 1). In addition to these ethnic differences, nonimmigrant participants (compared to their immigrant counterparts) reported lower ethnic identity, F(l, 9030) = 8.69, p = .003, partial η2 = .00 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Means by Ethnicity and Generation Status

| Ethnicity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian American | Black/African American | Hispanic or Latino(a) | White/European American | Generation Status | ||

| Immigrant | Nonimmigrant | |||||

| Perceived discrimination | 2.89c | 3.30a | 3.00d | 2.09b | 2.80 | 2.84 |

| Ethnic identity | 43.30c | 46.48a | 44.36c | 41.83b | 44.55a | 43.44b |

| Identity confusion | 17.24b | 15.29a | 15.56a | 15.88a | 15.86 | 16.12 |

| Depressive symptoms | 52.49a | 51.56ac | 50.74c | 50.21c | 51.09 | 50.64 |

Note. Means in the same row that do not share the same subscripts differ at p < .05 in ANOVAs.

Ethnicity × generation status interactions were found for PD, F(3, 8951) = 12.25, p < .001, partial η2 = .00, and ethnic identity, F(3, 9030) = 6.94, p < .001, partial η2 = .00, qualifying the main effects (see Tables 2a and 2b for marginal means). Planned analyses of these interactions using a Bonferroni correction revealed that generation status shaped perceptions of discrimination for Black/African American participants, F(1, 772) = 20.15, p < .001, partial η2 = .03, and White/European participants, F(1, 5762) = 15.24, p < .001, partial η2 = .00 (Table 2a). Generation status also influenced ethnic identity for Asian American, F(1, 1003) = 6.82, p = .009, partial η2 = .01, and Hispanic/Latino(a) participants, F(1, 1419) = 31.65, p < .001, partial η2 = .02 (Table 2a). Additionally, ethnicity influenced perceptions of discrimination and ethnic identity for both immigrant, F(3, 1016) = 64.40, p < .001, partial η2 = .16, and nonimmigrant participants, F(3, 7935) = 1294.96, p < .001, partial η2 = .33 (Table 2b).

Table 2a.

marginal means for groups separated by generation

| Asian American | Black/African American | Hispanic or Latino(a) | White/European American | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immigrant | Nonimmigrant | Immigrant | Nonimmigrant | Immigrant | Nonimmigrant | Immigrant | Nonimmigrant | |

| Perceived discrimination | 2.89 | 2.88 | 3.14a | 3.45b | 2.95 | 3.04 | 2.19a | 1.99b |

| Identity confusion | 17.38 | 17.10 | 14.73 | 15.85 | 15.43 | 15.68 | 15.91 | 15.86 |

| Ethnic identity | 44.12a | 42.49b | 45.81 | 47.14 | 46.14a | 42.59b | 42.12 | 41.54 |

| Depressive symptoms | 53.00 | 52.23 | 49.81 | 51.81 | 49.23 | 51.17 | 50.60 | 50.19 |

Note. For each ethnic groups in the same row that do not share the same subscripts differ at p<.05 in Bonferroni-corrected post hoc analyses.

Table 2b.

Marginal Means for Generations Separated by Ethnic Groups

| Immigrant | Nonimmigrant | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian American | Black/African American | Hispanic/Latino(a) | White/European American | Asian American | Black/African American | Hispanic/Latino(a) | White/European American | |

| Perceived discrimination | 2.89a | 3.14b | 2.95ab | 2.19c | 2.88a | 3.45b | 3.04c | 1.99d |

| Identity confusion | 17.38 | 14.73 | 15.43 | 15.91 | 17.10 | 15.85 | 15.68 | 15.86 |

| Ethnic identity | 44.12ab | 45.81bc | 46.14c | 42.12a | 42.49ac | 47.14b | 42.59c | 41.54a |

| Depressive symptoms | 53.00 | 49.81 | 49.23 | 50.60 | 52.23 | 51.81 | 51.17 | 50.19 |

Note. For each generation status, means in the same row that do not share the same subscripts differ at p < .05 in Bonferroni-corrected post hoc analyses.

Main and Moderating Effects of Identity

We examined the main and moderating roles of both identity variables (identity confusion and ethnic identity) in the PD-DS relationship (see Table 3 for bivariate correlations between PD and DS by each ethnic-generational subgroup) with a series of three-step hierarchical multiple regression analyses for each ethnic-generational subgroup (e.g., immigrant European American, nonimmigrant Hispanic/Latino(a)).1 Per the recommendations of Aiken and West (1991), we centered PD, identity confusion, and ethnic identity around their subgroup means, and we computed two-way and three-way interaction terms by multiplying together the appropriate variables. We entered the main effects in the first step of the analysis, followed by the two-way interactions in step 2, and the three-way interaction in step 3 (see Table 4 for full regression results).

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations between Perceived Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms for each Ethnic-Generational Subgroup

| Group | r | p |

|---|---|---|

| Asian American | ||

| Immigrant | .07 | .24 |

| Nonimmigrant | .15 | < .001 |

| Black/African American | ||

| Immigrant | .25 | .01 |

| Nonimmigrant | −.01 | .76 |

| Hispanic or Latino(a) | ||

| Immigrant | .23 | < .001 |

| Nonimmigrant | .14 | < .001 |

| White/European American | ||

| Immigrant | .21 | .003 |

| Nonimmigrant | .24 | < .001 |

Table 4.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses Predicting Depressive Symptoms From Perceived Discrimination, Identity Confusion, and Ethnic Identity

| Group | β | t | pβ | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immigrant Asian American (N = 285) | ||||

| Step 1 | R2 = .14, p < .001 | |||

| Discrimination | .04 | 0.65 | .51 | .001 |

| Confusion | .36 | 6.57 | < .001 | .13 |

| Ethnic identity | −.07 | −1.30 | .20 | .01 |

| Step 2 | ΔR2 = .001, p = .94 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion | .001 | 0.17 | .99 | .000001 |

| Discrimination × ethnic identity | .04 | 0.63 | .53 | .001 |

| Confusion × ethnic identity | .01 | 0.23 | .82 | .0002 |

| Step 3 | ΔR2 = .001, p = .60 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion × ethnic identity | .03 | 0.52 | .60 | .001 |

| Nonimmigrant Asian American (N = 549) | ||||

| Step 1 | R2 = .17, p < .001 | |||

| Discrimination | .12 | 2.94 | .003 | .01 |

| Confusion | .38 | 9.81 | < .001 | .15 |

| Ethnic identity | −.01 | −0.20 | .84 | .0001 |

| Step 2 | ΔR2 = .01, p = .07 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion | −.08 | −1.20 | .05 | .01 |

| Discrimination × ethnic identity | .06 | 1.35 | .18 | .003 |

| Confusion × ethnic identity | .05 | 1.31 | .19 | .003 |

| Step 3 | ΔR2 = .01, p = .02 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion × ethnic identity | −.11 | −2.44 | .02 | .01 |

| Immigrant Black/African American (N = 92) | ||||

| Step 1 | R2 = .32, p < .001 | |||

| Discrimination | .33 | 3.56 | .001 | .10 |

| Confusion | .47 | 5.31 | < .001 | .22 |

| Ethnic identity | −.09 | −0.97 | .34 | .01 |

| Step 2 | ΔR2 = .01, p = .69 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion | −.09 | −0.90 | .37 | .01 |

| Discrimination × ethnic identity | .01 | 0.13 | .90 | .0001 |

| Confusion × ethnic identity | −.05 | −0.45 | .65 | .002 |

| Step 3 | ΔR2 = .003, p = .52 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion × ethnic identity | .08 | 0.65 | .52 | .003 |

| Nonimmigrant Black/African American (N = 474) | ||||

| Step 1 | R2 = .25, p < .001 | |||

| Discrimination | .10 | 2.38 | .02 | .01 |

| Confusion | .50 | 12.39 | < .001 | .25 |

| Ethnic identity | −.02 | −0.54 | .59 | .001 |

| Step 2 | ΔR2 = .001, p = .87 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion | .02 | 0.51 | .61 | .0004 |

| Discrimination × ethnic identity | −.02 | −0.41 | .68 | .0003 |

| Confusion × ethnic identity | −.02 | −0.57 | .57 | .001 |

| Step 3 | ΔR2 = .001, p = .34 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion × ethnic identity | −.04 | −0.95 | .34 | .001 |

| Immigrant Hispanic or Latino(a) (N = 239) | ||||

| Step 1 | R2 = .31, p < .001 | |||

| Discrimination | .15 | 2.77 | .01 | .02 |

| Confusion | .51 | 9.31 | < .001 | .25 |

| Ethnic identity | .03 | 0.48 | .63 | .001 |

| Step 2 | ΔR2 = .01, p = .53 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion | −.01 | −1.40 | .89 | .0001 |

| Discrimination × ethnic identity | .01 | 0.11 | .92 | .00004 |

| Confusion × ethnic identity | .08 | 1.43 | .15 | .01 |

| Step 3 | ΔR2 = .01, p = .05 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion × ethnic identity | .11 | 1.95 | .05 | .01 |

| Nonimmigrant Hispanic or Latino(a) (N = 835) | ||||

| Step 1 | R2 = .23, p < .001 | |||

| Discrimination | .10 | 3.35 | .001 | .01 |

| Confusion | .46 | 15.06 | < .001 | .21 |

| Ethnic identity | −.02 | −0.54 | .59 | .0003 |

| Step 2 | ΔR2 = .004, p = .21 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion | −.01 | −2.70 | .79 | .0001 |

| Discrimination × ethnic identity | −.06 | −2.00 | .05 | .004 |

| Confusion × ethnic identity | −.01 | −0.45 | .65 | .0002 |

| Step 3 | ΔR2 = .0001, p = .69 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion × ethnic identity | −.01 | −0.40 | .69 | .0001 |

| Immigrant White/European American (N = 182) | ||||

| Step 1 | R2 = 26, p < .001 | |||

| Discrimination | .14 | 2.11 | .04 | .02 |

| Confusion | .46 | 6.94 | < .001 | .20 |

| Ethnic identity | .06 | 0.86 | .39 | .003 |

| Step 2 | ΔR2 = .01, p = .63 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion | .01 | .08 | .94 | .00003 |

| Discrimination × ethnic identity | −.09 | −1.32 | .19 | .01 |

| Confusion × ethnic identity | .01 | .14 | .89 | .0001 |

| Step 3 | ΔR2 = .01, p = .16 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion × ethnic identity | −.10 | −1.41 | .16 | .01 |

| Nonimmigrant White/European American (N = 4582) | ||||

| Step 1 | R2 = .26, p < .001 | |||

| Discrimination | .14 | 11.07 | < .001 | .02 |

| Confusion | .46 | 35.50 | < .001 | .20 |

| Ethnic identity | −.01 | −0.94 | .35 | .0001 |

| Step 2 | ΔR2 = .00008, p = .92 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion | .01 | .52 | .60 | .0001 |

| Discrimination × ethnic identity | .01 | .45 | .65 | .00004 |

| Confusion × ethnic identity | −.0001 | −0.01 | .99 | .00000001 |

| Step 3 | ΔR2 = .0001, p = .54 | |||

| Discrimination × confusion × ethnic identity | .01 | .61 | .54 | .0001 |

Note. Discrimination = perceived discrimination; Confusion = identity confusion.

Results indicated that there were small and significant positive main effects of PD on DS for all ethnic-generational groups, except immigrant Asian American participants. Results also showed medium and significant positive main effects of identity confusion on DS for all groups. In contrast, there were no significant main effects found for ethnic identity on DS. In addition, there were no two-way interactions and no consistent three-way interactions found across the eight groups, suggesting there were no consistent moderating effects of identity confusion and/or ethnic identity on the PD-DS relationship. However, we did probe the significant three-way interactions for nonimmigrant Asian American and immigrant Hispanic/Latino(a) participants using simple slope analyses. These analyses indicated that although these interactions effects were significant, the simple slopes were not different from each other (ps > .98). Therefore, we did not interpret the significant three-way interactions as moderation effects (Dawson & Richter, 2006).

Mediating Effects of Identity

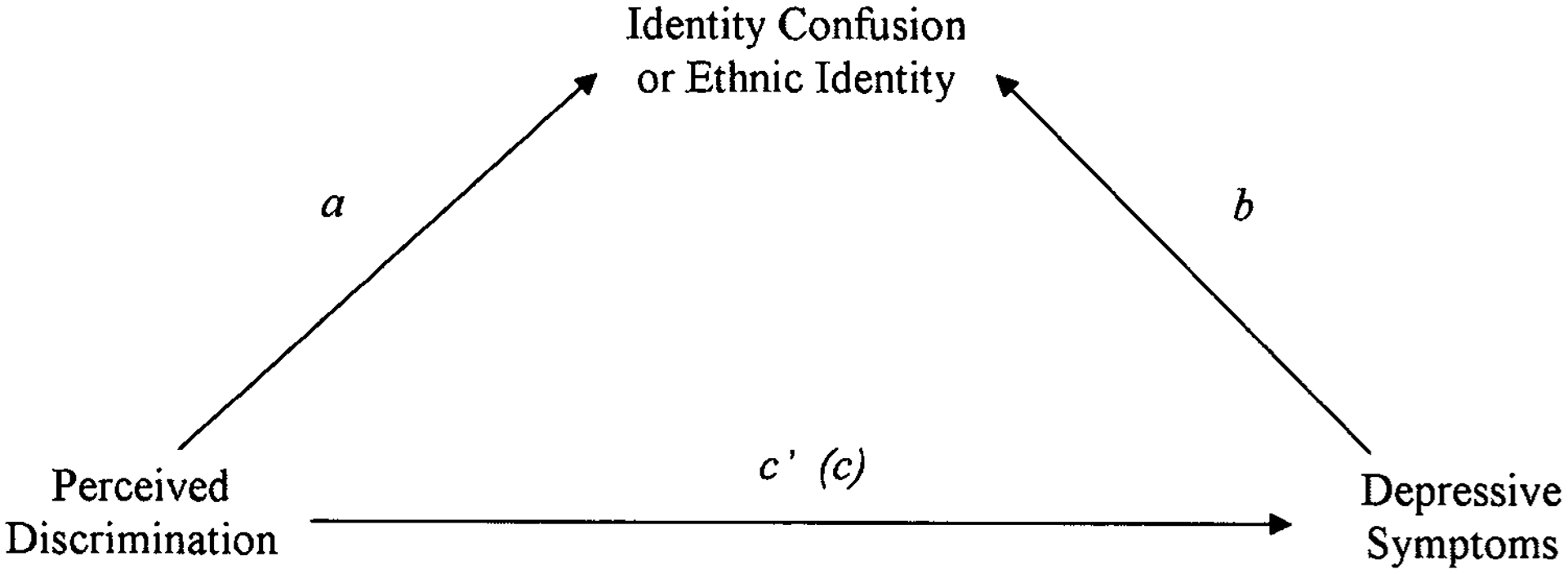

To examine the mediating effects of identity confusion and ethnic identity on the PD-DS relationship (Figure 1), we conducted mediation analyses based on the four steps outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986). If identity were a mediator, then PD would significantly predict DS (step 1, path c), PD would significantly predict identity (step 2, path a), identity would significantly predict DS controlling for PD (step 3, path b), and the ability of PD to predict DS would be greatly reduced when identity is included in the model (step 4, path c’). If the criteria outlined in steps 1 through 3 were met, then we conducted a Sobel test to determine whether identity confusion or ethnic identity significantly mediated the PD-DS relationship.

Figure 1.

Model of mediation/suppression effect of identity confusion or ethnic identity on the PD-DS relationship. Path c is effect of perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms before identity confusion or ethnic identity is included in the model.

We conducted these mediation analyses separately for each ethnic-generational group with identity confusion as the mediator (see Table 5) and then with ethnic identity as the mediator (see Table 6). In terms of identity confusion, paths a, b, and c were significant for immigrant and nonimmigrant Hispanic/Latino(a) participants, and immigrant and nonimmigrant White/European American participants, so we only conducted Sobel tests for these groups. As indicated by the Sobel test, identity confusion significantly mediated the PD-DS relationship for immigrant Hispanic/Latino(a) (z = 2.80, p = .005), nonimmigrant Hispanic/Latino(a) (z = 2.42, p = .02), immigrant White/European American (z = 2.30, p = .02), and nonimmigrant White/European American (z = 14.45, p < .001) participants. In terms of ethnic identity, paths a, b, and c were significant for immigrant Black/African American and nonimmigrant White/European American participants. However, Sobel tests indicated that ethnic identity did not significantly mediate the PD-DS relationship for these groups (ps > .05). In summary, identity confusion and ethnic identity were not moderators in the PD-DS relationship for any groups; and identity confusion was a partial mediator of the PD-DS relationship, but only for Hispanic/Latino(a) and White/European American participants.

Table 5.

Identity Confusion Mediation/Suppression Results for Each Ethnic-Generational Subgroup

| Path a (PD-IC) | Path b (IC-DS) | Path c (PD-DS) | Path c’ (PD-DS with IC in model) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Asian American | ||||||||

| Immigrant | .06 | .33 | .38 | < .001 | .07 | .24 | .04 | .45 |

| Nonimmigrant | .06 | .16 | .38 | < .001 | .14 | .001 | .12 | .003 |

| Black/African American | ||||||||

| Immigrant | .01 | .92 | .48 | < .001 | .30 | .004 | .29 | .001 |

| Nonimmigrant | −.18 | < .001 | .50 | < .001 | .002 | .97 | .09 | .03 |

| Hispanic or Latino(a) | ||||||||

| Immigrant | .17 | .004 | .51 | < .001 | .24 | < .001 | .14 | .01 |

| Nonimmigrant | .08 | .01 | .46 | < .001 | .15 | < .001 | .11 | .001 |

| White/European American | ||||||||

| Immigrant | .17 | .01 | .46 | < .001 | .23 | .002 | .15 | .03 |

| Nonimmigrant | .22 | < .001 | .46 | < .001 | .25 | < .001 | .14 | < .001 > |

Note. PD = perceived discrimination; IC = identity confusion; DS = depressive symptoms.

Paths a, b, c, and c’ are illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 6.

Ethnic Identity Mediation/Suppression Results for Each Ethnic-Generational Subgroup

| Path a (PD-EI) | Path b (EI-DS) | Path c (PD-DS) | Path c’(PD-DS with El in model) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Asian American | ||||||||

| Immigrant | .02 | .66 | −.08 | .19 | .06 | .29 | .06 | .28 |

| Nonimmigrant | .21 | < .001 | −.02 | .58 | .15 | < .001 | .15 | < .001 |

| Black/African American | ||||||||

| Immigrant | .20 | .03 | .01 | .91 | .26 | .01 | .26 | .01 |

| Nonimmigrant | .19 | < .001 | −.08 | .09 | −.01 | .86 | .008 | .85 |

| Hispanic or Latino(a) | ||||||||

| Immigrant | .06 | .28 | −.006 | .92 | .24 | < .001 | .24 | < .001 |

| Nonimmigrant | .17 | < .001 | .05 | .05 | .14 | < .001 | .15 | < .001 |

| White/European American | ||||||||

| Immigrant | .11 | .11 | .05 | .51 | .21 | .004 | .21 | .005 |

| Nonimmigrant | .03 | .05 | −.03 | .03 | .24 | < .001 | .24 | < .001 |

Note. PD = perceived discrimination; El = ethnic identity; DS = depressive symptoms.

Paths a, b, c, and c ‘ are illustrated in Figure 1.

The results of the mediation analysis with nonimmigrant Black/African American participants indicated that identity confusion suppressed the effects of PD on DS. (Suppression is a specific type of mediation effect; Shrout & Bolger, 2002.) Per the recommendations by Baron and Kenny (1986), there are three steps in determining whether suppression exists, all of which we found in our mediation results. First, we observed that the relationship between PD (the predictor) and DS (the criterion) was very small and nonsignificant for this group, which met the first requirement for suppression. Second, PD was a significant predictor of lower identity confusion (i.e., negative relationship between PD and identity confusion), meeting the second requirement for suppression. Third, when identity confusion was added to the model, the effect of PD on DS increased significantly (see Figure 1 and Table 5), meeting the last requirement for suppression. In other words, PD predicted DS for U.S.-born Black/African Americans but only after the relationship between identity confusion and DS was removed.

Discussion

Despite extensive previous research examining the possible moderator effects of ethnic identity in the outcomes of PD, there is little research that examines these effects across ethnically (i.e., Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino(a), and White/European American) and generationally(i.e., foreign-born/immigrant, U.S.-born/nonimmigrant) diverse groups. Further, there are few studies that examine ethnic identity’s possible mediator effects in the PD-distress link, and no work that examines the possible moderator and/or mediator infiuence of personal identity confusion. To address these shortcomings, the possible moderation and mediation effects of identity confusion and ethnic identity on the relationship between PD and DS were explored in eight ethnic-generational college student groups. Several important findings emerged.

First, ethnic identity findings were consistent with previous research, indicating lower levels among U.S.-born Hispanic/Latino(a) and Asian American individuals compared with comparable foreign-born individuals (Yip et al., 2008). Second, similar PD levels between some immigrant ethnic minority groups (e.g., Black/African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos(as)) were found. However, no such similarities were evident among nonimmigrant ethnic minorities, with Black/African Americans reporting the highest PD levels, then Hispanics/Latinos(as), and Asian Americans. In contrast, White/European Americans, whether foreign-or U.S.-born, reported significantly lower levels of PD compared with all respective ethnic minority groups. Collectively, these PD findings support Sidanius and Pratto’s (1999) Social Dominance Theory in which they suggest that power is typically held by one or two dominant groups (in this case U.S.-born White/European Americans) with subordinate groups placed on lower levels in a dynamic hierarchy.

Finally, unlike ethnic identity and PD, identity confusion levels were similar for most ethnic groups and both generation groups (i.e., no interactions were found), and they strongly and consistently predicted DS across all eight ethnic-generational groups. These results indicate that identity confusion might have qualities that are shared across culture.

Findings related to the primary focus of the study suggested that ethnic identity neither moderated nor mediated the relationship between PD and DS for any of the ethnic-generational groups. The consistency of the findings was unexpected given theoretical assertions that ethnic identity protects subordinate group members from the deleterious consequences of PD (Phinney, 1990). Although implications of our findings should be considered in the context of the reported modest effect sizes, our results are in line with patterns found in the empirical literature. A review of this literature shows that, of the chosen studies that examined the moderating effects of group identification on the PD-psychological health relationship, 50% report finding no effect (Brondolo et al., 2009). Similarly, a meta-analysis of studies related to group identification’s moderation role in the mental health outcomes of broadly defined perceived discrimination (e.g., ethnic, gender, and unfair treatment) found no effect in 78% of analyses (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009).

Future research that addresses our study’s limitations, discussed later, needs to be conducted to place our findings within existing frameworks. It is possible that ethnic identity does not affect the outcomes of PD for ethnic minorities in isolation and, instead, works in conjunction with other variables not tested, like social support and coping (Lee, 2003; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009) or other forms of identity (e.g., American identity; Park et al., 2012). Preliminary evidence of the joint moderating effects of ethnic identity and coping in a sample of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada supports this assertion (Noh et al., 1999), but replication of these findings with U.S. college students is needed.

Comparable to the ethnic identity findings, identity confusion did not moderate the PD-DS relationship for any groups. Because there are no other studies on the moderation effects of identity confusion on the PD-DS relationship, the null findings are difficult to interpret. It may be that identity confusion interacts with PD to affect behavioral not psychological outcomes, or it may be that identity confusion mediates, but does not moderate, the PD-DS relationship. In support of the latter possibility and theoretical assertions (Schwartz, 2005), identity confusion did partially mediate the PD-DS relationship for both immigrant and nonimmigrant Hispanic/Latino(a) and White/European American participants.

This mediation effect may be related to rising negative opinions and legislation (e.g., anti-immigration laws) against Hispanic/Latino(a) individuals (Brader, Valentino, & Suhay, 2008), and general perceptions of rising anti-White bias by White/European Americans (Norton & Sommers, 2011). Even though these shifts are at the ethnic group level, their recency may temporarily disrupt the direct PD-DS pathway, whereby PD leads to feeling confused, personally vulnerable, and fearful of the future (identity confusion), which in turn leads to DS. Ascertaining whether this pattern of findings holds for Arab Americans, who also experienced negative public opinion shifts after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, would provide further endorsement for this explanation.

For U.S.-born Black/African Americans, analyses suggested that identity confusion suppressed (a special case of mediation) the relationship between PD and DS. In other words, for this group, including the indirect effects of identity confusion increased the direct effect of PD on DS (unlike a typical mediator which causes a reduction in the direct effect of the predictor on the criterion variable). This unexpected finding can be partially attributed to the fact that, unlike all the other ethnic-generational groups, PD was negatively associated with identity confusion for U.S.-born Black/African Americans, but, like other groups, identity confusion was positively associated with DS. The unique history of U.S.-born Black/African Americans may be why this relationship does not exist for other groups. Specifically, perceiving ethnic group discrimination may motivate U.S.-born Black/African Americans to clarify their future goals and direction. Importantly, this finding indicates the need to examine identity confusion when assessing the PD-DS relationship with U.S.-born Black/African Americans, and suggests that existing findings may underestimate the predictive validity of PD on DS in this population.

Intervention Strategies

The results of this study are relevant for therapists who work with college students. At minimum, the data emphasize the need to determine if and how PD experiences and identity confusion levels may be affecting ethnic minority clients who exhibit or report depressive symptoms. This requires not only assessing these variables at intake, but, after therapist-client trust is built, also opening the space for clients to talk about their experiences related to these variables in ways that support their perspectives.

For immigrant and nonimmigrant Hispanic/Latino(a) and White/European American college students, the mediation model suggests that identity confusion is increased after group or personal discrimination is perceived resulting in depressive symptoms. As such, reducing identity confusion by supporting these students in the identification and clarification of their social roles, choice of major, and future professional goals may mitigate the PD-related depressive symptoms. Given the reduction in identity confusion that results from PD experiences in U.S.-born Black/African Americans, targeting identity confusion in this population should be undertaken cautiously.

Even if individual-level interventions focused on reducing identity confusion are successful, the mediation model suggests that future PD experiences could cause deterioration back to high identity confusion levels. Prevention of this deterioration is possible only if structural changes are made to limit discrimination of ethnic-generational groups in concert with individual-level interventions (Hatzenbuehler, 2009, comes to a similar conclusion regarding sexual minorities). One such change could be requiring courses and other academic experiences that focus on issues of privilege, prejudice, and discrimination in K-12 and higher education curricula. Other changes at the university level could include: clearly articulated guidelines as to what constitutes discrimination and how such behaviors will be addressed; policies to ensure that the ethnic-generational makeup of the student, faculty, and administrative bodies are geographically representative; and required professional development opportunities for faculty and staff on the deleterious effects of overt and subtle discrimination (Hurtado, Milem, Clayton-Pedersen, & Allen, 1998).

Strengths, Limitations, and Conclusions

Sample characteristics both strengthened and limited this study. On the positive side, the nationally derived sample reduced the impact of geographic region on the findings. Further, the large sample size made examination of the variables of interest within eight ethnic-generational groups possible, something that has not been done previously and which enabled interesting comparisons and conclusions. On the negative side, the ethnic categories did not allow for the examination of nationality or other important cultural distinctions that might have influenced the findings. Finally, time in the U.S. was not assessed for foreign-born participants. This over-sight is problematic given that time in the U.S. is associated with stronger relationships between PD and DS (Gee, Ryan, Lafiamme, & Holt, 2006).

The study design and measures also impacted the findings. The cross-sectional nature of the data makes any causal attributions and directional interpretations speculative, requiring additional empirical study to provide support. For example, unlike our interpretations, the mediation effect of identity confusion may be the result of high depressive symptoms leading to more role and future confusion, which then leads to increases in perceived discrimination. Additionally, empirical evidence indicates a tendency of target group members to: (a) misattribute subtle discrimination to personal factors (Ruggiero & Taylor, 1995) and (b) underreport personal discrimination compared with group discrimination (Crosby, 1984; Taylor, Wright, Moghaddam, & Lalonde, 1990). These findings suggest that our use of a self-report measure of PD that partially examined personal ethnic discrimination, although typical of research in this area, may have resulted in an underestimation of PD levels.

Even with these limitations, our study provides important advances in the understanding of whether and how personal identity and ethnic identity affect the PD-DS relationship in college students. We also go beyond most existing work in this area by simultaneously examining ethnicity and generation status. In sum, our findings suggest that personal identity (i.e., identity confusion) may be more relevant to the PD-DS relationship than ethnic identity, at least for Hispanic/Latino(a) and White/European American college students. However, this finding may change if actual or perceived political and social attitudes toward these groups improve or attitudes toward other underrepresented ethnic-generational groups become more negative. Additionally, our findings on the different levels of perceived discrimination and ethnic identity by ethnic-generational group challenge the perception that all “minorities” and/or all members of an ethnic group share similar experiences and respond similarly to perceived discrimination, emphasizing the importance of examining ethnicity and generation status effects in future related studies.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was conducted as part of the Multi-Site University Study of Identity and Culture (MUSIC). All MUSIC collaborators are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

We also conducted the moderation and mediation analyses using ethnicity as a predictor variable. The results of these analyses are consistent with those reported above, and for ease of interpretation and clarity, we chose to report results of analyses done separately by ethnic group instead of those using ethnicity as a predictor variable.

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks KH, & Kohn-Wood LP (2007). The influence of racial identity profiles on the relationship between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms. journal of Black Psychology, 33, 331–354. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brader T, Valentino NA, & Suhay E (2008). What triggers public opposition to immigration? Anxiety, group cues, and immigration threat. American Journal of Political Science, 52, 959–978. [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, & Harvey R (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, ver Halen NB, Pencille M, Beatty D, & Contrada RJ (2009) Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 64–88. doi: 10.1007/sl0865-008-9193-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark V, & Williams DR (1999). Racism as a Stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist, 54, 805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté J, & Bynner JM (2008). Changes in the transition to adulthood in the UK and Canada: The role of structure and agency in emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth Studies, 11, 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby F (1984). The denial of personal discrimination. American Behavioral Scientist, 27, 371–386. [Google Scholar]

- Czopp AM, & Monteith MJ (2006). Thinking well of African Americans: Measuring complimentary stereotypes and negative prejudice. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 28, 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson JF, & Richter AW (2006). Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 917–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine PG, & Elliot AJ (1995). Are racial stereotypes fading? The Princeton trilogy revisited. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1950). Childhood and society.: New York, NY: Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ryan A, Laflamme DJ, & Holt J (2006). Self-reported discrimination and mental health status among African descendants, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH 2010 initiative: The added dimension of immigration. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1821–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(1), 42–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 707–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado S, Milem JF, Clayton-Pedersen AR & Allen WR (1998). Enhancing campus climates for racial/ethnie diversity: Educational policy and practice. The Review of Higher Education, 21, 279–302. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh Q, Devos T, & Dunbar CM (2012). The psychological costs of painless but recurring experiences of racial discrimination. Cultural Diversity and Ethnie Minority Psychology, 18, 26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh Q, Devos T, & Smalarz L (2011). Perpetual foreigner in one’s own land: Potential implications for identity and psychological adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30, 133–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M (1991). Stereotyping Hispanies and Whites: Perceived differences in social roles as a determinant of ethnie stereotypes. The Journal of Social Psychology, 131,469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Kao G (2000). Group images and possible selves among adolescents: Linking stereotypes to expectations by race and ethnieity. Sociological Forum, 15, 407–430. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Wang Y, Deng S, Alvarez R, & Li J (2011). Accent, perpetual foreigner stereotype, and perceived discrimination as indirect links between English proficiencly and depressive symptoms in Chinese American adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 47, 289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM (2003). Do ethnic identity and other-group orientation protect against discrimination for Asian Americans? Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50, 133–141. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.50.2.133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM (2005). Resilience against discrimination: Ethnie identity and other-group orientation as protective factors of Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 32, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Malcarne VL, Chavira DA, Fernandez S, & Liu P j. (2006). The scale of ethnic experience: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Personality Assessment, 86(2), 150–161. doi: 10.1207/sl5327752jpa8602_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski KN (2003). Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 318–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Beiser M, Kasper V, Hou F, & Rummens J (1999). Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: A study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40(3), 193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton M 1., & Sommers SR (2011). Whites see racism as a zero-sum game that they are losing. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 215–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Operario D, & Fiske ST (2001). Ethnic identity moderates perceptions of prejudice: Judgments of personal versus group discrimination and subtle versus blatant bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 550–561. [Google Scholar]

- Park IJK, Schwartz SJ, Lee RM, Kim M, & Rodriguez L (2012). Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and antisocial behaviors among Asian American college students: Testing the moderating roles of ethnic and American identity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 2012 June 11 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Smart Richman L (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez DJ, Fortuna L, & Alegría M (2008). Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. (1990). Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 108,499–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. (1992). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with adolescents and young adults from diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7(2), 156–176. doi: 10.1177/074355489272003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Ong AD (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 271–281. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivadeneyra R (2006). Do you see what I see? Latino adolescents’ perceptions of the images on television. Journal of Adolescent Research, 21, 393–414. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal DA, Gurney RM, & Moore SM (1981). From trust to intimacy: A new inventory for examining Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 10(6), 525–537. doi: 10.1007/BF02087944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KM, & Taylor DM (1995). Coping with discrimination: How disadvantaged group members perceive the discrimination that confronts them. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 826–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ (2005). A new identity for identity research: Recommendations for expanding and refocusing identity literature. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20, 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ (2007). The structure of identity consolidation: Multiple correlated constructs or one superordinate construct? Identity: An International Journal of Theory, 7,127–149. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Beyers W, Luyckx K, Soenens B, Zamboanga LF, … Waterman AS (2011). Examining the light and dark sides of emerging adults’ identity: A study of identity status differences in positive and negative psychosocial functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 839–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Montgomery MJ, & Briones E (2006). The role of identity in acculturation among immigrant people: Theoretical propositions, empirical questions, and applied recommendations. Human Development, 49, 1–30. doi: 10.1159/000090300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Wang SC, & Olthuis JV. (2009). Measuring identity from an Eriksonian perspective: Two sides ofthe same coin? Journal of Personality Assessment, 9, 143–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Weisskirch RS, & Rodriguez L (2009). The relationships of personal and ethnic identity exploration to indices of adaptive and maladaptive psychosocial functioning. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, & Lewis RL (2006). Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning of African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Settles IH, Navarrrete CD, Pagano SJ, Abdou CM, & Sidanius J (2010). Racial identity and depression among African American women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, & Bolger N (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius J, & Pratto F (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Syed M Azmitia M, & Phinney JS (2007). Stability and change in ethnic identity among Latino emerging adults in two contexts. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 7, 155–178. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, & Turner JC (1986). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict In Worchel S & Austin W (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 2–24). Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DM, Wright SC, Moghaddam FM, & Lalonde RN (1990). The personal/group discrimination discrepancy: Perceiving my group, but not myself, to be a target of discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16, 254–262. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KS, Nelesen RA, Malcarne VL, Ziegler MG, & Dimsdale JE (2006). Ethnicity, perceived discrimination, and vascular reactivity to phenylephrine. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68, 692–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman KH, & Weiss UK,. (2009). Nativity status and depressive symptoms among Hispanic young adults: The role of stress exposure. Social Science Quarterly, 90, 1228–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorova ILG, Falcón LM, Lincoln AK, & Price LL (2010). Perceived discrimination, psychological distress and health. Sociology of health and illness, 32, 6, 843–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomfohr L, Pung MA, Edwards KM, & Dimsdale JE (2012). Racial differences in sleep architecture: The role of ethnic discrimination. Biological Psychology, 89, 34–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2011). Overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf

- Wei M, Heppner PP, Ku T, Liao Y (2010). Racial discrimination stress, coping, and depressive symptoms among Asian Americans: A moderation analysis. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 1, 136–150. [Google Scholar]

- Welch K (2007). Black criminal stereotypes and racial profiling. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 23, 276–288. [Google Scholar]

- Welch K, Payne AA, Chiricos T, & Gertz M (2011). The typification of Hispanics as criminals and support for punitive crime policies. Social Science Research, 40, 822–840. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Mohammed SA (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 20–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Williams-Morris R (2000). Racism and mental health: The African American experience. Ethnicity & Health, 5, 243–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CA, Eccles JS, Sameroff A (2003). The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents’ school and socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Personality, 71, 1197–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Lai CF, Nagasawa R, & Lin T (1998). Asian Americans as a model minority: Self-perceptions and perceptions by other racial groups. Sociological Perspectives, 41, 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Gee GC, & Takeuchi DT (2008). Racial discrimination and psychological distress: The impact of ethnic identity and age among immigrant and United States-born Asian adults. Developmental Psychology, 44, 787–800. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder A (2000). Barriers to ego identity formation: A contextual qualification of Marcia’s identity status paradigm. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HC, & Lee RM (2009). Does ethnic identity buffer or exacerbate the effects of frequent racial discrimination on situational well-being of Asian Americans? Asian American Journal of Psychology, SI, 70–87. [Google Scholar]