Abstract

Objectives

To report available information in the literature regarding frequency, indications, types of antibiotic usage, duration, and their efficacy in Covid-19 infected patients.

Methods

The search was conducted on April 30 and May 7, 2020, using Ovid database and Google search. Patients’ characteristics, clinical outcomes, as well as selected characteristics regarding antibiotic use (indication, class used, rates and types of bacterial secondary and co-infection, and duration of treatment) were analyzed.

Results

Nineteen clinical studies reporting data from 2834 patients were included. Mean rate of antibiotic use was 74.0 % of cases. Half the studies reported occurrence of a bacterial co-infection or complication (10 studies). Amongst the latter, at least 17.6 % of patients who received antibiotics had secondary infections. Pooled data of 4 studies show that half of patients receiving antibiotics were not severe nor critical. Detailed data on antibiotic use lack in most articles.

Conclusions

The present review found a major use of antibiotics amongst Covid-19 hospitalized patients, mainly in an empirical setting. There is no proven efficacy of this practice. Further research to determine relevant indications for antibiotic use in Covid-19 patients is critical in view of the significant mortality associated with secondary infections in these patients, and the rising antimicrobial resistance.

Keywords: Antibiotic treatment, COVID-19, Coronavirus infection, Pneumonia, Review paper

Introduction

‘’No time to wait’’: the title chosen for the recently published International Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance United Nations-addressed report [1] speaks for itself. Health systems are currently facing an acute and critical challenge in most countries: the Covid-19 pandemic. However, the latter should not overshadow the issue of antimicrobial resistance but rather emphasize it, and this for two reasons. First, it appears that secondary bacterial infections are often responsible for fatalities among influenza pandemics, as was the case in the 1918 influenza outbreak and the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic [2]. Similarly, in a Wuhan-based study reporting outcomes and treatment for 191 patients hospitalized for Covid-19 [3], 50% of deaths were imputable to secondary bacterial infections. Thus, antibiotics appear to be a crucial defense against mortality in Covid-19 patients. Second, resistance to antimicrobials is already currently estimated to cause 700, 000 deaths worldwide yearly [1] and would therefore also be expected to play a significant role in Covid-19-related mortality. Regarding influenza, Infectious Diseases Society of America’s updated guidelines in 2018 [4] stated that ‘’there are no data to support the safety or efficacy of antibiotic chemoprophylaxis to prevent bacterial complications.’’ Similarly, the Covid-19 guidelines of the China National Health Commission (CNHC) [5] stated that ‘’blind or inappropriate use of antibiotic drugs should be avoided, especially broad-spectrum antibiotics.’’

However, detailed data on relevant indications for antibiotic use in these patients needs to be investigated. We present here a review of studies reporting use of antibiotics in hospitalized Covid-19 patients. We reported the information regarding frequency, indications, types of antibiotic usage, duration, and their efficacy in Covid-19 patients.

Methods

Selection criteria and search study

Inclusion criteria were journal articles reporting clinical studies on treatment of Covid-19 patients with antibiotics. Case reports, non-clinical studies, reports on coronavirus other than the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, and articles not mentioning the use of antibiotic in these patients were excluded from the review. Studies for which data about antibiotic treatment were too scarce were excluded. Research was limited to English-language articles relative to adults. Two sources of information were used in this review.

First, we searched on Google using the terms ‘’Covid-19’’ and ‘’antibiotic use’’ and selected the first result: an article questioning the impact of antibiotic use in Covid-19 patients on antibiotic resistance [6]. The author notes the creation of a website by Adam Roberts and Issra Bulgasim to report ‘’secondary infections, antibiotic chemotherapy and antibiotic resistance in the context of Covid-19’’ [7]. As of April 30th, there were 27 reported articles on the website from peer-reviewed published literature. We included fourteen studies as per our including criteria.

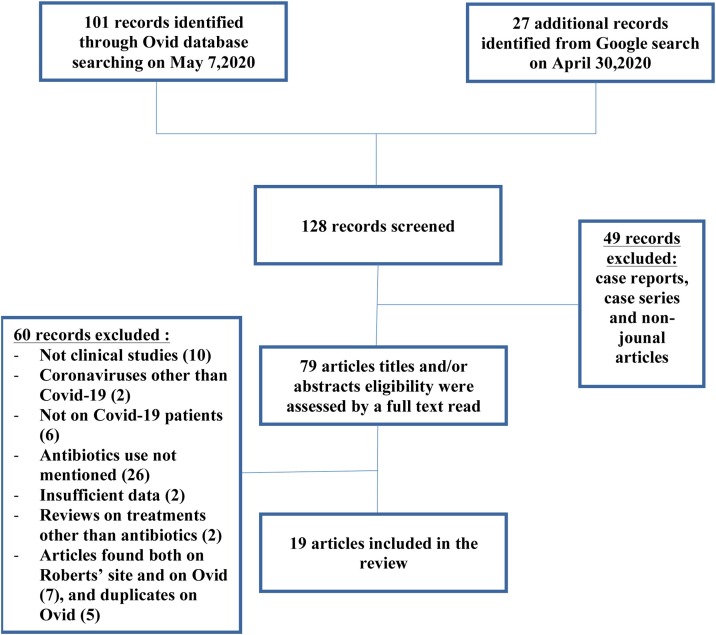

Secondly, we searched Ovid on May 7th, 2020 using ‘’Ovid Medline (R) and Epub ahead of print, In-Process, and other non-indexed citations, daily and versions (R)’’ database. Four keywords were used with their associated MeSH terms: ‘’Covid*’’ with its relevant associated MeSH terms (‘’coronavirus infections’’, ‘’betacoronavirus’’, ‘’pneumonia’’, ‘’viral’’, and ‘’severe acute respiratory syndrome’’), “therapy*” with its associated MeSH terms (‘’drug therapy’’ and ‘’drug therapy, combination’’), ‘’treatment*’’ and its associated MeSH terms (‘’treatment failure’’ and ‘’treatment outcome’’), and “antibiotics”. This research retrieved 101 records. After eliminating case reports and non-journal articles from both research results (49 in total), 79 article titles and/or abstracts were assessed for eligibility. A full text read was performed later, to ensure the compliance of the chosen articles with inclusion criteria. Only 5 articles were ultimately selected through Ovid search. Most retrieved studies were retrospective, with 3 being multicenter studies [3,8,9]. One was a clinical trial [10], and 1 was a randomized clinical trial [11]. Twelve duplicates found in both searches were excluded. Searching through the bibliography of the studies did not provide additional studies. A flow chart is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the search.

Studied variables

The following characteristics were extracted from each study: country where the study was conducted, number of patients, percentage of chronic diseases (such as hypertension, diabetes, cardio-vascular disease, pulmonary disease, etc.) as reported in each study, percentage of severe cases, death rate, rate of antibiotic use, rate and type of secondary and co-infection, types of antibiotics used, duration of antibiotic treatment, as well as rate of use of glucocorticoids and antivirals.

Definition of studied variables

Four articles used the guidelines from the CNHC to classify patients’ severity [3,8,12,13]. "Mild" was defined as mild clinical symptoms or asymptomatic with no signs of pneumonia on imaging, "Moderate" was defined as having fever or respiratory tract symptoms and signs of pneumonia on imaging; "Severe" was classified if one of the following was present: a) dyspnea with a respiratory rate of ≥ 30 per minute, b) saturation ≤ 93%, and c) PaO2 / FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg; "Critical" was classified if one of the following was present: a) respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, b) shock, and c) co-existing multiple organ failure requiring close monitoring in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). One article reported severity according to American Thoracic Society guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia [14]. Other articles [10,[16], [17], [18], [19], [20]] reported severity in terms of presence of hypoxemia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute renal injury, septic shock or admission to the intensive care unit, without mentioning the overall prevalence of severe patients. For the latter studies, we only reported the most prevalent severity criterion to avoid overestimating the level of severity of the given cohort.

Secondary infection was defined as an infection occurring after the treatment of an initialinfection, and co-infection was defined as an infection occurring during the treatment of Covid-19 infection.

Results

Epidemiology and patients’ characteristics

Nineteen studies were included, comprising 2834 patients in total. Most articles (sixteen) came from China, one from the United States [20], one from Brazil [11], and one from Denmark [21]. Some studies reported age of the patients as a mean, others as a median and it ranged between 28 [22] and 69.5 [20] years old for median age and 52.9 [8] and 65.5 [19] for mean age. 23.7% (873) of patients had previous preexistent chronic diseases. Pooled mortality rate was 11 % (405 patients among 2834). 36.2% (1026 out of 2834) patients were classified as severe patients. Patients’ characteristics of the 19 selected studies are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Data gathered from the 19 selected articles regarding patients’ characteristics as well as modalities of antibiotic usage.

| Author | Country | Number of patients | Severity of the disease and death rate | Rate of antibiotic use | Coinfections and secondary infections rate | Site of infection and available culture | Types of antibiotics used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. (16) | China, Wuhan | 138 | • ICU transfers: 36 (26.1%) • 6 (4.3%) | At least 89 (64.4%) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | • Moxifloxacin: 89 (64.4%) • Ceftriaxone: 34 (24.6%) • Azithromycin: 25 (18.1%) |

| Wang et al. (17) | China, Wuhan | 107b | • ARDS: At least 28 (26.2%) • 19 (17.7%) | 85 (79.4%) | Bacterial coinfections: 5 (4.7%) | • 1 bacteremia (Staphylococcus caprae) • 4 bacterial pneumonia (Acinetobacter baumannii) | Not mentioned |

| Z. Wang et al. (18) | China, Wuhan | 69 | • Hypoxemia: 14 (20.3%) • 5 (7.5%) | 66 (98.5 %) | 3 positive sputum cultures (43% of patients had sputum culture) | Acinetobacter baumannii and Enterobacter cloacae, 2 Chlamydia IgG (+) | • Moxifloxacin (58%) |

| He et al. (24) | China, Wuhan | 65e | • Severe: 43 (66%) • 10 (15.4 %) if occurrence of a secondary infection vs 19 (7.3%) if not | Prophylactic use: 49 (75.4 %) | Secondary bacterial infections: 7.1% (65 out of 918) | • Pneumonia (32.3%), bacteremia (24.6%), and urinary tract infection (21.5%) • Coagulase negative staphylococcus (27.9%), Acinetobacter (20.9%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (14.0%) | Antibiotics used prophylactically: • Fluoroquinolones (61.5%) • A combination of antibiotics (10.8%) • Cephalosporins (9.2%) • Beta lactam/Beta-lactamase inhibitors (7.7%) • Azithromycin (4.6%) • Ornidazole (3.1%). |

| Zhou et al. [3] | China, Wuhan | 191 | • Severe or critical: 119 (62.3%) • 54 (28.3%) | 181 (95%) | 50% in non survivors vs 1% of survivors (p < 0.0001) | • VAP (31% of intubated patients) • Septic shock (38; 20%) • Negative cultures upon admission | Not mentioned |

| Yang et al. (27) | China, Wuhan | 52 | • Only critically-ill patients • 32 (61.5%) | 49 (94%) | Hospital-acquired infections: 13.5% | • HAP (11.5%) • Aspergillus flavus, A fumigatus, extended spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL)-positive K pneumonia, ESBL-positive Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and ESBL-negative Serratia | Not mentioned |

| Huang et al. (19) | China, Wuhan | 41 | • ICU patients: 13 (32%) • 6 (15%) |

41 (100%) | Secondary infections: 10% | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| G. Chen et al. (13) | China, Wuhan | 21 | • Only moderate and severe cases • 4 (19%) | 21 (100%) | Secondary infections: 3- all in severe cases (27.3% of severe cases) | Not mentioned, presence of positive cultures for the diagnosis of secondary bacterial infection | • Moxifloxacin • Cephalosporin |

| N. Chen et al. [25] | China, Wuhan | 99 | • Severity criteria upon admission: 33 (33%) • 11 (11%) | 70 (71%) | Not mentioned | Common pathogens of secondary infections included A baumannii and K pneumoniae | • Cephalosporins • Quinolones • Tigecycline • Single antibiotic: 25 (25%) • Combination: 45 (45%) |

| T. Chen et al. (14) | China, Wuhan | 274c | • Only moderate and severe cases • 113 of 799 (14.1 %) | 249 (91%) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | • Moxifloxacin • Cefoperazone • Azithromycin |

| H. Chen et al. (22) | China, Wuhan | 9d | • No severe case and no deaths | 9 (100%) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Xu et al. (26) | China, Zhejiang province | 62 | • Severe: 0 (0%) • 0 (0%) | 28 (45%) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | • Quinolones And • Second generation Beta lactams (oral and intravenous) |

| Cao et al. (10) | China, Hubei province | 199 | • Hypoxemia: 199 (100%) • 44 (22.1%) | 189 (95%) | Secondary infections: 7 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Pan et al. (8) | China, Hubei province | 204 | • Severe or critical (among patients with digestive symptoms): 37 (36.6%) • 36 (17.7%) | 141 (69.12%) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Zhao et al. (23) | China, Hubei province | 91 | • Severe: 30 (33.0%) • 2 (2.2%) | 90 (98.9%) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | • Cephalosporins: 27 (29.7%) • Fluoroquinolones 84 (92.3%) • Carbapenems 2(2.2%) |

| Guan et al. (9) | China, 30 provinces | 1099 | • Severe: 173 (15.7%) • 15 (1.4%) | 637 (58%) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

| Borba et al. (11) | Brazil | 81 | • Only severe cases • 22 (27.1%) | 81 (100%) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | • Intravenous ceftriaxone (1 g twice daily) Plus • Azithromycin (500 mg daily) |

| Pedersen et al. (21) | Denmark | 16 | • Only intubated patients • 7 (43.75%) | 16 (100%) | At least 1 (6.25%) | VAP: 1 patient, Enterobacter cloacae | • Meropenem and clarithromycin: 5 • Piperacillin-tazobactama • Vancomycin |

| Aggarwal et al. (20) | United States | 16 | • Hypoxemia: 6 (38%) • 3 (18.75%) | At least 7 (43%) | Not mentioned | VAP: 1, Clostridium difficile infection: 1 | • Azithromycin (43%) |

Piperacillin-tazobactam changed to meropenem if clinical worsening, with/without addition of vancomycin.

88 patients in the report have been included in the JAMA cohort.

Cases analyzed among a cohort of 799.

Study included only pregnant women.

65 patients who had secondary infections were analyzed out of a cohort of 918 patients.

Rate of use of antibiotics, antivirals, and glucocorticoids

Mean rate of antibiotic usage was 74.0% (2098 out of 2834 patients). Compared to antibiotics, antivirals were used in 56.9% of patients (1613 out of 2834 patients). Glucocorticoids were used in 36.9% of patients (1045 out of 2834).

Types of antibiotics used and duration of treatment

Only 4 studies comprising 375 patients reported frequency of use of different types of antibiotics [11,15,22,23]. Fluoroquinolones were the most used, with 56.8% of patients (213 out of 375), followed by ceftriaxone in 39.5% of patients (148 out of 375), then azithromycin in 29,1% of patients (109 out of 375). Carbapenems were only used in 2 patients. Seven articles [12,13,17,19,20,24,25] reported the types of antibiotics used but with scarce data regarding their frequency of use. Only 3 studies reported duration of treatment: Chen et al. [24] reported that it ranged between 3 and 17 days, with a median of 5 days. Borba et al. [11] reported a duration of 7 days (for Ceftriaxone) and 5 days (for Azithromycin). Pedersen et al. [21] reported that clarithromycin was discontinued if cultures for atypical bacteria were negative, whereas duration of treatment for meropenem and piperacillin-tazobactam was at least eight days.

Coinfections, secondary infections rate and timing, and impact on survival

Eight studies [10,12,13,19,21,24,25,27] recorded the occurrence of secondary infections and 2 [16,17] reported co-infection rates. Pooled secondary and co-infection rate was 7.6% (123 out of 1614 patients). Among studies reporting secondary infections, only one did not report frequency of these infections [25]. Compiled results showed that 17.6% of patients (123 out of 697) who received antibiotics had secondary or co-infections. Interestingly, Zhou et al. [3] noted that mean time until occurrence of secondary infections was 17 days after diagnosis for non survivors and 14 days for survivors who developed a secondary infection. He et al. [24] reported that use of combination antibiotics was a significant predictor of nosocomial infection after adjustment for other covariates (OR, 1.84, 95% CI, 1.31–4.59; P = .003). Moreover, death rate was 15.4 % for patients who had secondary infections versus 7.3% in patients without secondary infections (OR 3.87; 3.87; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.84–4.16; P = .045). Wang et al. [17] noted there were significantly more coinfections in non-survivors than in survivors. Similarly, Zhou et al. [3] reported that 50% of deaths in their cohort were imputable to secondary infections.

Antibiotic use rate according to patients’ severity and survival rate

Three studies reported a higher antibiotic use rate in more severe patients. Guan et al. [9] noted that antibiotic use rate was higher among severe patients (80.3% vs 53.8% of non-severe patients). G. Chen et al. [13] administered empirical antibiotics for all moderate and severe cases. Among the 5 studies reporting data from exclusively severe or critical patients [10,11,21,24,27], rates of antibiotic use was more than 90% except for the study of He et al. in which only 75.4% of patients received empiric antibiotics despite severe disease. Similarly, Lei Pan et al. [8] reported 67.9% of moderate patients receiving antibiotics but 100% of severe ones. However, 91.3% of critical patients received antibiotics. However, rules for antimicrobial prescription were not mentioned. Conversely, 2 studies [22,26] that did not report any severe cases reported rates of antibiotic use of 45% and 100%. 4 studies [3,14,17,27] comparing survivors and non-survivors found no significant difference regarding antibiotic use. Among the 4 studies reporting severity according to the CHNC [8,[12], [13], [14]], three mentioned the number of severe and critical cases. Pooled results show that 48.7% (167 out of 343) of patients who received antibiotics in these studies were severely or critically ill.

Antibiotic use rate according to duration of symptoms, and laboratory values

Xu et al. [26] noted that antibiotic use rate was higher (48% vs 41%) when duration of symptoms exceeded 10 days. They also reported that antibiotics were administered if fever lasted for more than seven days. Xu et al. [26] noted that antibiotics were administered when C-reactive protein levels were 30 mg/L or more (normal range 0−8 mg/L). Pedersen et al. [21] selected trend of Procalcitonin to aid in antibiotic monitoring.

Discussion

This review exposes several critical findings related to antibiotic use in hospitalized Covid-19 patients.

Frequency, indications and type of antibiotic use

This review highlights the heavy use of antibiotics in patients hospitalized for Covid-19 (74% of hospitalized patients among 19 studies). Although detailed clinical reasoning for antibiotic prescription lack in most studies, some general tendencies can be underlined. Firstly, only a minority of patients (17.6% among 4 studies) who receive antibiotics have proven secondary or co- bacterial infection, indicating a major empiric use of antibiotics. Of note, Guan et al. [9] reported difficulties in performing bacteriologic or fungal assessment on admission because of overwhelmed medical structures. Interestingly, none of the studies explored quality of care in terms of saturation of the related hospital structures, possibly because of the retrospective design of most of the studies. However, efforts to obtain appropriate culture samples are critical to ensure appropriate antimicrobial stewardship. Secondly, although antibiotic treatment was found to be generally more prevalent in more severe patients, half of patients who received antibiotics were not severe, indicating a tendency to extend indications of antibiotic therapy to non-severe patients. Further studies investigating antibiotic use in this category of patients are of uttermost importance to limit unrelevant unrelevant antibiotic prescriptions, and thereby antimicrobial resistance. Thirdly, fluoroquinolones were the most used class among the reports, despite their known propensity to induce resistance. No study investigated the type of empiric antibiotic therapy chosen according to the severity of the patient. Future studies in this area are critical to ensure an optimal antimicrobial usage in the Covid-19 patients. Finally, further research is warranted regarding the supportive role of laboratory panels to optimize antimicrobial stewardship.

Regarding efficacy of antibiotics

Four studies [3,14,17,27] comparing survivors and non-survivors found no significant difference regarding antibiotic use. However, there was no study on survival rate according to presence or absence of empiric antibiotic treatment. Antibiotic efficacy should be further investigated prospectively in Covid-19 patients to minimize their unrelevant use. Conversely, impact of empiric antibiotherapy on secondary infections should also be further investigated, given that one study [24] reported an association between use of combination of antibiotics and occurrence of secondary infection.

Antibiotic use in Covid-19 infected patients

The most frequently used antibiotics were fluoroquinolones, macrolides and cephalosporins. Possible explanation for such use is lung coverage for pneumococcal, gram negative and atypical bacterial infections. Ventilator associated infections were reported in many studies, without mention of any specific involved organism. Two studies reported isolation of Staphylococcus species [17,24], but there was no mention of methicillin resistant Staph aureus isolates in any article. It is unclear why and how antibiotics were used in most of these studies.

Impact of antibiotic use in patients with comorbidities

Specific patients’ comorbidities should be addressed when deciding on the type of antibiotic and route of administration to use. Quinolones were frequently used in reported studies. However, these are associated with many adverse events including QT interval prolongation, tendon rupture and aortic dissection. [28] No adverse event was reported in selected studies. Intravenous route of administration of antibiotics was the most used as many patients were defined as having severe Covid-19 infection and may have had an impaired oral absorption. Corticosteroids, recently approved for use in severely ill patients with Covid-19 who are on supplemental oxygen or ventilatory support, expose the patient to a risk of hyperglycemia and hypertension. [29] Patients receiving steroids and antibiotics are usually the ones who have medical comorbidities and are sicker. This population of patients are usually on concurrent chronic medications and the addition of antibiotics could increase the risk of drug-drug interaction. Physicians should weigh benefits against risks before initiating such drugs.

Antimicrobial resistance in Covid-19 pandemic

The impact of Covid-19 on antimicrobial resistance is currently difficult to predict, however most studies report heavy empirical use contrasting with relatively low frequency of bacterial co-infection and secondary infections [30]. Antimicrobial exposure has been demonstrated to be a risk factor for increase microbial resistance [31]. In addition to that, long duration of hospitalization with intensive care unit stay increases the risk of infections with multidrug-resistant organisms [32]. Antimicrobial stewardship program is among other important strategies to reduce such risk [33].

Antibiotic usage in Covid-19 with gastrointestinal problems

Recent studies suggest that patients with altered gut microbiota might experience more severe Covid-19 symptoms [34]. Given that antibiotics may further alter digestive microbial flora, empiric treatment for bacterial pneumonia in Covid-19 patients should only be initiated when clinical suspicion is high. It is unclear what would be the most appropriate antibiotic in bacterial coinfected Covid-19 patients with gastrointestinal symptoms.

Limitation of this review

As to the designs of the studies, most of them reported that a significant portion of patients were still in hospital by the end of the study (for example, 34.1% in Wang et al. (16)). This may have led to an overestimation of the total rate of antibiotic use and secondary infections. Furthermore, classifications regarding patients’ severity were heterogenous, rendering comparison between articles difficult. Only a limited number of published articles was included, mostly from Republic of China and this could have impacted the results. Nonetheless, we provided the rate of severe patients in each study, as this variable is critical to determine relevance of antibiotic use. Regarding types of secondary bacterial and co-infections, we decided to report the available results, although little information was presented.

Conclusion

This review presented data from nineteen studies regarding antibiotic usage in 2834 patients with Covid-19 disease. Mean rate of antibiotic usage was 74%. Only 17.6 % of patients who received antibiotics had secondary infections and half of the patients who received antibiotics were not severe, indicating a significant tendency to initiate antibiotics in mild or moderate patients. Four retrospective studies reported no benefit of antibiotic treatment on mortality. Detailed data on antibiotic use are lacking in most articles. Further research on this matter is critical to determine relevant indications for antibiotic use in Covid-19 patients.

References

- 1.IACG_final_report_EN.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 18]. Available from: https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/interagency-coordination-group/IACG_final_report_EN.pdf?ua=1.

- 2.Cox M.J., Loman N., Bogaert D., O’Grady J. Co-infections: potentially lethal and unexplored in COVID-19. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1(1):e11. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uyeki T.M., Bernstein H.H., Bradley J.S., Englund J.A., File T.M., Fry A.M. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2018 Update on Diagnosis, Treatment, Chemoprophylaxis, and Institutional Outbreak Management of Seasonal Influenza. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2019;68(6):e1–47. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Covid-19 guidelines of the China National Health Commission [Internet]. Available from: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/pdf/2020/1.Clinical.Protocols.for.the.Diagnosis.and.Treatment.of.COVID-19.V7.pdf.

- 6.McKenna M. Covid-19 May Worsen the Antibiotic Resistance Crisis | WIRED [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 19]. Available from: https://www.wired.com/story/covid-19-may-worsen-the-antibiotic-resistance-crisis/.

- 7.Roberts A., Bulgasim I. COVID-AMR [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 19]. Available from: https://covid-amr.webnode.co.uk/.

- 8.Pan L., Mu M., Yang P. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients with digestive symptoms in Hubei, China: a descriptive, cross-sectional, multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(5):766–773. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., Liang W., Ou C., He J. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., Liu W., Wang J., Fan G. A trial of Lopinavir–Ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borba M.G.S., Val F.F.A., Sampaio V.S., Alexandre M.A.A., Melo G.C., Brito M. Effect of high vs low doses of chloroquine diphosphate as adjunctive therapy for patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e208857. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou F. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. XXX. 2020;395:9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen G., Wu D., Guo W., Cao Y., Huang D., Wang H. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2620–2629. doi: 10.1172/JCI137244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H., Yan W., Yang D., Chen G. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olson G., Davis A.M. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2020;323(9):885. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang D., Yin Y., Hu C., Liu X., Zhang X., Zhou S. Clinical course and outcome of 107 patients infected with the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, discharged from two hospitals in Wuhan, China. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):188. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02895-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z., Yang B., Li Q., Wen L., Zhang R. Clinical Features of 69 Cases With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa272. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aggarwal S., Garcia-Telles N., Aggarwal G., Lavie C., Lippi G., Henry B.M. Clinical features, laboratory characteristics, and outcomes of patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Early report from the United States. Diagnosis. 2020;7(2):91–96. doi: 10.1515/dx-2020-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedersen H.P., Hildebrandt T., Poulsen A., Uslu B., Knudsen H.H., Roed J. 2020. . Initial experiences from patients with COVID-19 on ventilatory support in Denmark; p. 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen H., Guo J., Wang C., Luo F., Yu X., Zhang W. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020;395(10226):809–815. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao X.-Y. 2020. Clinical characteristics of patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in a non-Wuhan area of Hubei Province, China: a retrospective study; p. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He Y., Li W., Wang Z., Chen H., Tian L., Liu D. Nosocomial infection among patients with COVID-19: a retrospective data analysis of 918 cases from a single center in Wuhan, China. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu X.W., Wu X.X., Jiang X.G., Xu K.J., Ying L.J., Ma C.L. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. Feb 19;368:m606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. Erratum in: BMJ. 2020 Feb 27;368:m792. PMID: 32075786; PMCID: PMC7224340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., Shu H., Xia J., Liu H. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Research C for DE and. FDA warns about increased risk of ruptures or tears in the aorta blood vessel with fluoroquinolone antibiotics in certain patients. FDA [Internet]. 2019 Dec 20 [cited 2020 Sep 21]; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-warns-about-increased-risk-ruptures-or-tears-aorta-blood-vessel-fluoroquinolone-antibiotics.

- 29.Mirzaei F., Khodadadi I., Vafaei S.A., Abbasi-Oshaghi E., Tayebinia H., Farahani F. Importance of hyperglycemia in COVID-19 intensive-care patients: mechanism and treatment strategy. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2021.01.002. S1751-9918(21)00002-00004. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2021.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaughn V.M., Gandhi T., Petty L.A., Patel P.K., Prescott H.C., Malani A.N. Empiric antibacterial therapy and community-onset bacterial Co-infection in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: a multi-hospital cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1239. Aug 21:ciaa1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchaim D., Chopra T., Bhargava A., Bogan C., Dhar S., Hayakawa K. Recent exposure to antimicrobials and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: the role of antimicrobial stewardship. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(8):817–830. doi: 10.1086/666642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ang H., Sun X. Risk factors for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria infection in intensive care units: a meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Pract. 2018;24(4):e12644. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12644. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12644. Epub 2018 Mar 25. PMID: 29575345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teerawattanapong N., Kengkla K., Dilokthornsakul P., Saokaew S., Apisarnthanarak A., Chaiyakunapruk N. Prevention and control of multidrug-resistant gram-negative Bacteria in adult intensive care units: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_2):S51–S60. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix112. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix112. PMID: 28475791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim H.S. Do an altered gut microbiota and an associated leaky gut affect COVID-19 severity? mBio. 2021;12(1) doi: 10.1128/mBio.03022-20. e03022-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03022-20. PMID: 33436436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]