Abstract

This review takes a closer look at the structural components of the molecules involved in the processes leading to caspase-1 activation. Interleukins 1β and −18 (IL-1β, IL-18) are well-known pro-inflammatory cytokines that are produced following cleavage of their respective precursor proteins by the cysteine protease caspase-1. Active caspase-1 is the final step of the NLRP3 inflammasome, a three-protein intracellular complex involved in inflammation and induction of pyroptosis (a proinflammatory cell-death process). NLRP3 activators facilitate assembly of the inflammasome complex and subsequently, activation of caspase-1 by autoproteolysis. However, the definitive structural components of active caspase-1 are still unclear and new data add to the complexity of this process. This review outlines the historical and recent findings that provide supporting evidence for the structural aspects of caspase-1 autoproteolysis and activation.

1. Introduction

The nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-, leucine-rich repeat- and pyrin domain (PYD)-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome has attracted widespread research interest due to its role in numerous diseases that have inflammation as a contributing factor. The inflammasome complex involves three proteins and the culmination of complex assembly is the production of an active caspase-1 enzyme. The complexity in the steps leading to formation of mature caspase-1 and the exact structural arrangement of the active enzyme has fostered many investigations. In this review we will summarize the historical and more recent biophysical studies of caspase-1 and caspases in general. Discussion topics will include the role of primary structure, oligomerization, autoproteolysis, quaternary structure, and stability in caspase-1 activation.

2. NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1

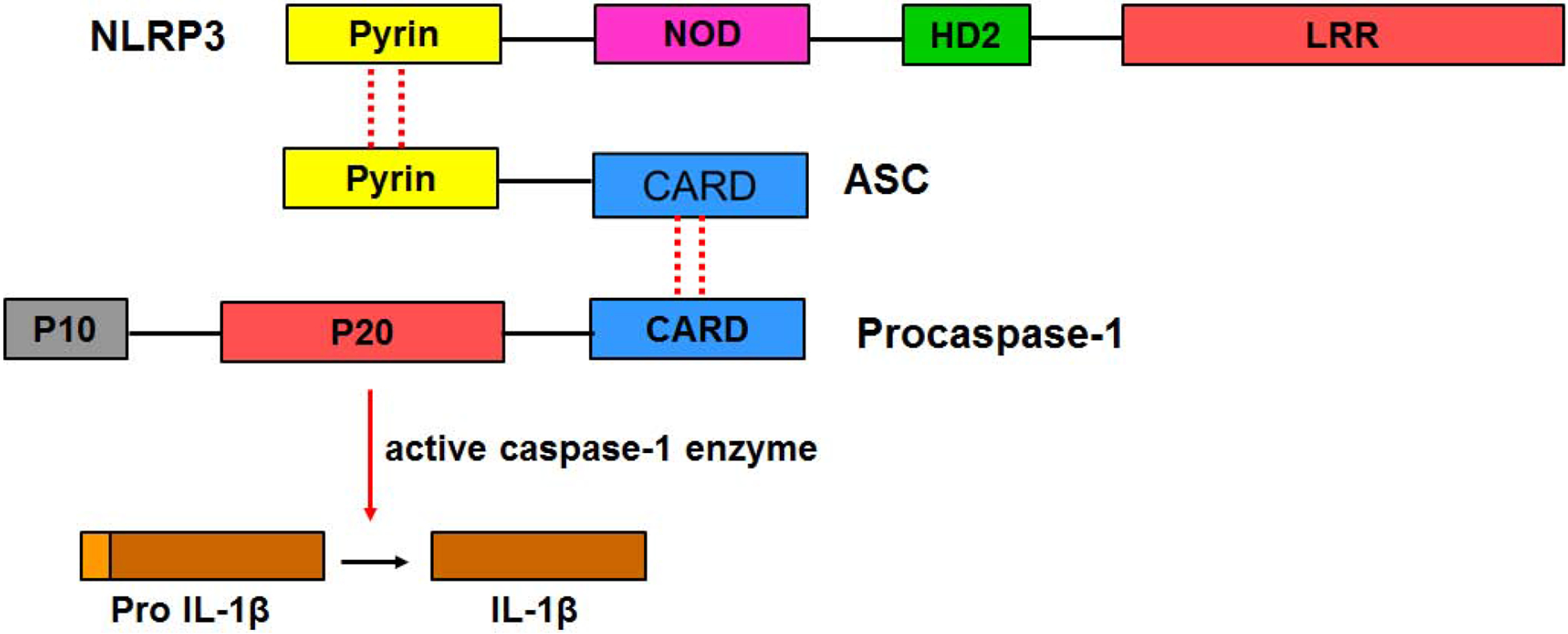

The innate immune system is the first line of defense in the event of an infection or cellular stress [1, 2]. It involves the production of inflammatory cytokines by immune cells such as microglia, monocytes, and macrophages. Intracellular protein complexes known as “inflammasomes” are assembled as part of the immune response signaling processes [3–6]. The NLRP3 inflammasome is of particular interest due to its role in numerous inflammatory disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), autoimmune disorders, cancers, and cardiovascular diseases [7–11]. The NLRP3 inflammasome is known as the caspase-1 activating complex. As shown in Fig 1, it is comprised of NLRP3, ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruitment domain, CARD), and procaspase-1. When encountering a variety of inflammatory environments, a cascade of events occur that causes the assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome. This involves detection of danger signals by NLRP3, oligomerization, recruitment of ASC via PYD-PYD interactions, and ASC filament and eventually speck formation. ASC specks act as molecular platforms that recruit procaspase-1 to the inflammasome complex via CARD-CARD interactions. These interactions are crucial as they ultimately lead to mature, active caspase-1 [12–15].

Fig 1. Key proteins and domains of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

The complex is comprised of NLRP3 (senses stimuli via the leucine-rich region LRR), ASC (adaptor protein), and procaspase-1 (effector protein). The domains making up each individual protein are highlighted. The dashed lines show the homotypic interactions (due to hydrophobic and charged residues) leading to complex formation by the three proteins. Activated caspase-1 cleaves pro-IL-1β to form mature IL-1β. It should be noted that the actual stoichiometric components of each individual protein in the complex are unknown.

The focus of this review is caspase-1, an inflammatory caspase required for IL-1β and IL-18 production, but not necessarily for pyroptosis [16]. Caspase-1, also known as IL-1β converting enzyme (ICE), is the first mammalian caspase to be discovered [17, 18]. The active enzyme, determined to be a cysteine protease, was initially isolated from stimulated THP1 monocyte cell lysates [19] and human peripheral blood monocytes [20] in 1989. The mechanistic and structural steps that lead to activation of the enzyme have been under vigorous investigation since the discovery of the enzyme, yet there are still remaining questions about how autoproteolysis and oligomerization regulate formation of the active enzyme, and the actual enzyme structure itself.

3. Structural aspects of caspases that influence activation

Caspases are the mammalian homologues of cell-death protein 3 (CED-3), a death protease found in C. elegans [21]. These cysteine proteases play vital roles in inflammation and pyroptosis in response to stimuli [3, 22]. A comprehensive and detailed review by Winkler and Rosen-Wolff discusses the roles of caspase-1 in innate immunity and the differential requirements for its expression, autoprocessing, and enzymatic activity [23]. Caspases can be classified based on their structure or function. They are primarily grouped into inflammatory or apoptotic caspases; and the latter can be further divided into initiator and executioner (effector) caspases [24–26]. The nomenclature of caspases also includes the class I-III grouping. Class I caspases (inflammatory caspases) consist of the human caspases 1, 4, 5, and 11 (mouse homolog of human caspases 4 and 5) with caspase-1 being the most characterized. Class II caspases, also known as initiator caspases, include caspases 2, 8, 9, and 10 while human executioner caspases 3, 6, and 7 make up the third class [27–30]. Caspases are expressed as inactive zymogens that are subsequently activated by removal of a prodomain [27, 29]. Hence, caspases are also grouped based on the size of the prodomain. Those with long prodomains fall into the first category (includes inflammatory and initiator caspases) while those with short prodomains make up the second category (this includes executioner caspases) [21]. Caspase-6, whose classification is unique and quite complex, can act as an executioner caspase and sometimes play initiator and inflammatory roles [31, 32].

Inflammatory and initiator caspases are self-activating and require assembly of multiprotein complexes [25]. The long prodomains (> 90 residues, ~ 11 kD) are located on the N terminus of caspases. The prodomain contains either a CARD or a death effector domain (DED), either of which are key for the protein-protein interactions that lead to oligomerization and caspase activation. Prodomains also facilitate the recruitment of caspases to death complexes via interactions with adaptor proteins such as ASC that are integrally involved in the oligomerization process, and provide a platform for caspase stabilization [21, 32]. The shorter prodomain (20–30 residues) executioner caspases require activation by initiator caspases [21, 33]. Many mechanisms of proteolytic cleavage-mediated caspase activation can be observed in recombinant systems [34–37]. For example, procaspase-3, an executioner caspase, was activated in vitro by initiator caspases 8 and 10 [38]. Furthermore, fusion of the prodomain of caspase-2 (an initiator caspase) to caspase-3 resulted in an active chimeric protein that underwent autoproteolytic cleavage [39].

Structural similarities between caspases within each distinct group result in the comparable mechanisms of activation. One example is caspases 3 and 7 with 54% sequence identity, and significant structural and functional similarities [37, 40]. Even with the structural similarities within a group of caspases, there can be differences in activation. Inflammatory/initiator caspases 4, 5, and 11 are activated by the non-canonical inflammasome pathway and do not require a receptor or an adaptor protein. This mechanism is distinct from that of fellow group member caspase-1 [41]. The length of the prodomain is only a general classification method as there are subgroups within these classifications [42]. Although they belong to the same long prodomain group of caspases, the CARD domain of caspase-9 (apoptosis initiator) is functionally distinct from that of caspase-1 (inflammatory) [21]. Oligomerization has been shown to be a common mechanism in the caspase activation process and this topic will be discussed further below. When overexpressed, DEDs of caspase-8 formed filaments [43] in a similar manner to caspase-2 oligomerization via the CARD domains [39].

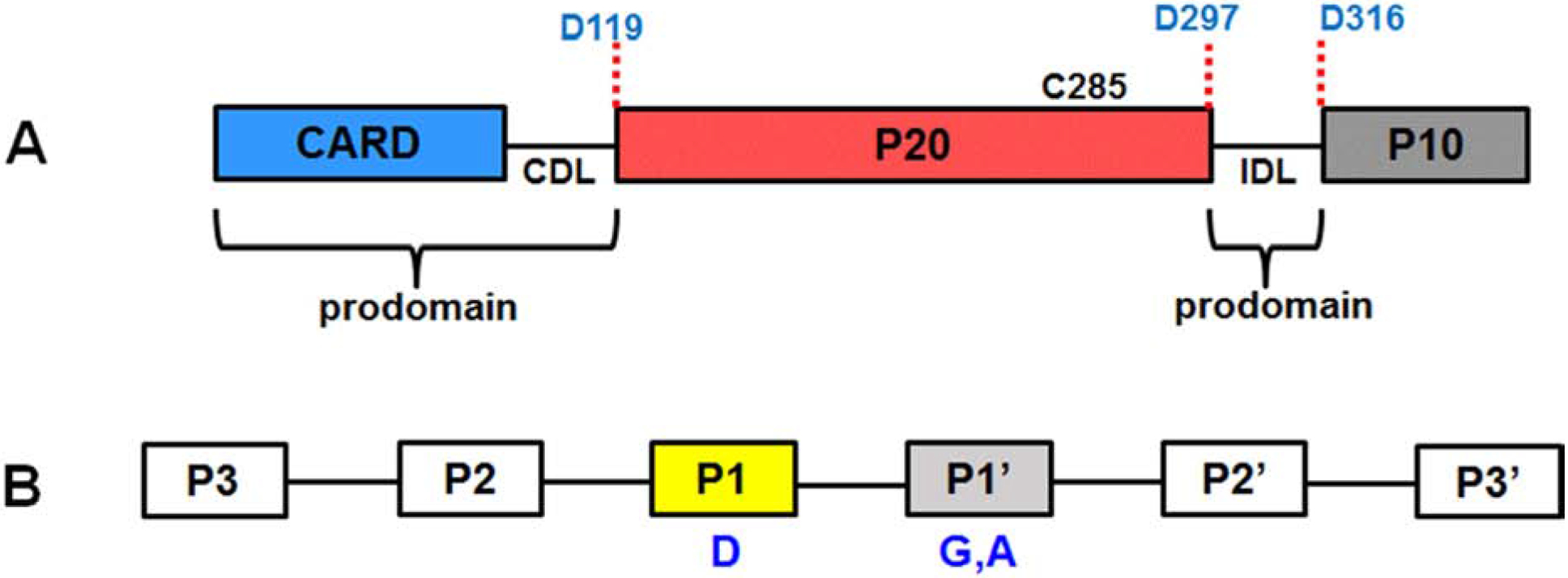

Along with the N-terminal prodomain, nearly all caspases also require removal of an interdomain linker (IDL) that separates large and small subunits within the caspase domain [40, 42, 44, 45]. Procaspase-1 also possesses these common sequence characteristics with an N-terminal prodomain comprised of the CARD (residues 1–95), a CARD domain linker (CDL) to the caspase domain, and the IDL between the p20 and p10 subunits (Fig 2A). The catalytic C285 cysteine residue is located within the p20 segment. Autoproteolytic cleavage occurs at three aspartic acid residues (D119, D297, D316) releasing the prodomains (CARD, CDL, IDL) as a key step in the caspase-1 activation process [17, 46]. Accordingly, mutation of C285 abolished proteolytic processing of the procaspase-1 protein [47, 48]. Much of this information was obtained from early studies by Thornberry et al. at Merck Research Laboratories that involved purification, sequencing, and rigorous characterization of the enzyme [17]. It was determined that the 45 kD procaspase-1 protein went through autoprocessing via cleavage at three sites to yield two distinct p20 and p10 subunits. It was proposed that the p20 and p10 subunits subsequently recombine to form the active enzyme [17]. Further kinetic studies would identify both p20 and p10 subunits as essential components of the active enzyme [17, 49]. Isolation of the purified p10 subunit demonstrated the importance of this domain in maintaining caspase-1 activity [49].

Fig 2. Caspase-1 autoproteolytic processing and substrate recognition sequence.

A. Structure of human caspase-1 showing multiple domains, linkers, segments, the three aspartic acid cleavage sites, and the catalytic C285 residue. The CARD domain linker (CDL) separates the CARD and p20 segment, while the interdomain linker (IDL) connects p20 and p10. The CARD, CDL and IDL are part of the prodomain. B. Key caspase-1 recognition sites for pro-IL-1β proteolytic processing. P1 represents the aspartic acid cleavage site, while the P1’ position favors a small, hydrophobic residue such as glycine or alanine.

The gene coding for caspase-1 is located on chromosome 11q22.3 and it is made up of 10 exons [50]. Alternative splicing in exons 2–7 produces various isoforms of caspase-1 that have differential effects on cell survival or death [50]. This type of regulation is also observed with splice variants of caspase-9 that differentially affect execution of apoptosis [51]. To date, 6 different isoforms of caspase-1 have been identified [52]. Initially, five splicing variants (α, β, γ, δ, and ε) were identified by Litwack and colleagues [53]. Another variant, ζ, was later discovered by Auersperg and colleagues [52]. The splice variants differ in size and the loss of key domains. Caspase-1 α is the longest and predominant variant. The shortest caspase-1 isoform, ε, lacks an intact CARD, a p20 subunit, and a full p10 subunit. Hence, caspase-1 ε is not catalytically active, but can inhibit activity of caspase-1 α by binding to the p20 subunit [53, 54]. The β, γ, δ, ε, and ζ variants have missing or truncated CARDs [52], but the isoforms in that group with full catalytic subunits (α, β, γ) still have apoptotic properties [53]. Thus, caspase-1 variants that lack or have truncated catalytic domains (δ, ε) are not active, yet can have regulatory properties via inhibition [53], while isoforms with missing or truncated N-terminal regions (β, γ, δ, ε, and ζ) likely do not participate in CARD-CARD interactions, but if catalytically active, can mediate inflammatory or apoptotic pathways. These findings suggest that an intact (full-length) prodomain is not necessarily a requirement for particular processes. While less studied than NLRP3 and ASC, posttranslational modifications also appear to play a role in caspase-1 activity [55–58]. Phosphorylation has been shown to regulate both activity and subsequent apoptosis [57, 59, 60]. Furthermore, PI3-K/Rac1/p21-activated kinase (PAK1) phosphorylated caspase-1 at Ser 376 (located in the p10 domain) and activated the enzyme [61]. Consistent with this observation, THP-1 cells transfected with mutant caspase-1 (S376A) showed a reduced inflammatory response [61].

Studies of the quaternary structure of the stable enzyme reveal that caspases 1, 8, and 9 exist as monomers under normal conditions with the caspase-9 undergoing dimer formation at high concentrations [24, 29, 62]. In contrast, executioner caspases 3 and 7 exist as constitutive dimers before and after proteolytic cleavage [25–27] although their catalytic efficiency increases drastically after cleavage [24, 29, 63]. Salvesen and colleagues reported that recombinant caspase-8 exists as a mixture of monomers and dimers in equilibrium. Using controlled proteolysis, they showed that proteolytic cleavage alone did not generate an active enzyme and that dimerization was also required for activity. Sodium citrate induced dimerization and possible structural rearrangement of caspase 8 in a concentration-dependent manner and dissociation of the dimer occurred upon buffer dilution [64]. Thus, it is important to take into consideration that certain experimental conditions (high protein concentrations due to overexpression, buffers, ionic strength, presence of kosmotropes, pH) may promote oligomerization and may not be a clear reflection of the actual processes under physiological conditions. It is clear that many factors contribute to the formation of mature active caspase-1, yet the absolute determination of the mechanistic steps and whether there may be different pathways is still not fully understood.

4. Caspase-1 and its substrate pro-IL-1β

Pro-IL-1β, a 33 kD protein, is an important biological substrate of caspase-1 and cleavage occurs at a single aspartic acid site (between D116 and D117) to form the mature ~ 17 kD form [18–20]. Early studies by Black and colleagues demonstrated that co-incubation of pro-IL-1β and THP-1 lysates generated the mature form of the cytokine supporting the idea that a protease with a particular substrate specificity was present in the lysates [19]. Ion exchange and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) purification of the enzyme activity enhanced its potency 500-fold. The protease’s sensitivity to iodoacetate and N-ethylmaleimide suggested that it was a cysteine protease although it was not affected by E64, a common inhibitor of cysteine proteases [19]. Molecular cloning of the isolated purified enzyme and co-transfection with pro-IL-1β cDNA into Cos7 cells yielded a processed mature substrate [18]. The molecular weight of the purified, auto-processed enzyme was determined to be 22 kD by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Thus, the researchers concluded that the proenzyme had undergone processing at both N-and C-termini [18, 19]. Additional groups conducted cellular assays with caspase-1 inhibitors resulting in the abrogation of mature IL-1β release thus reinforcing the fact that caspase-1 is responsible for IL-1β maturation [17, 65, 66]. Protease digestion studies using peptides of different lengths that span the cleavage site of pro-IL-1β substrate identified a minimum recognition sequence of four residues for the enzyme with a synthetic acetylated tetrapeptide, Ac-YVAD-NH-CH3, as the optimal caspase-1 substrate [17]. Later studies would demonstrate WEHD to be a superior caspase-1 substrate to YVAD [67, 68]. According to the accepted nomenclature used to identify the key substrate residues, the aspartic acid cleavage site is assigned the P1 position as shown in Fig 2B. Additional work by Tocci and colleagues revealed that the P1’ position favors a small, nonpolar residue usually glycine or alanine [17, 69]. Amino acid substitutions in the P2 position were found to be tolerable and did not significantly affect substrate specificity [17] (Fig 2B). Interestingly, the 4-residue pro-IL-1β cleavage site (YVHD116) is quite different than the procaspase-1 autocleavage sites (AVQD119, WFKD297, and FEDD316). The search for additional identify caspase-1 substrates is being aided by the use of proteomics and was recently summarized in a recent review by Julien and Wells [29].

Amino acid sequencing and mass spectrometry (MS) not only confirmed the primary structure of the proenzyme, but also identified the individual domains that made up the protein. The large subunit contains the catalytic site while the smaller subunit houses the dimer interface [31]. Studies also indicated that the active cysteine 285 residue is situated in the p20 domain [17, 49]. Crystal structures of caspase-1 would confirm that Cys 285 and His 237 formed the active site [47, 48]. Walker and colleagues published the crystal structure of recombinant human ICE bound to chloromethylketone, an irreversible inhibitor [47] or reversible aldehyde inhibitors [48]. Their findings revealed the active enzyme to be a heterotetramer (p202p102) of symmetrical p20p10 dimers linked by hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds [47, 48, 70]. Active site binders were found to induce structural changes causing caspase-1 [70, 71] and −6 [31] to adopt different conformations. Crystal structures of refolded enzyme obtained by Romanowski and colleagues suggested a possible mechanism by which pro-IL-1β substrate binds to the active site. Similar structures were obtained with both malonate [70] and tetrapeptide inhibitors [48]. Both inhibitors occupied the conserved S1 pocket (extremely basic region which binds to the side chain of aspartic acid) located in the active site thus allowing the enzyme active site to adopt an open-like state making it capable of binding substrates [70, 71]. Therefore, the authors suggested that the free caspase-1 represents an intermediate form of the enzyme and that a closed active site makes the enzyme more susceptible to self-proteolysis [70]. An intriguing question for future study is how the substrate binding site for pro-IL-1β develops during the conversion of procaspase-1 to mature caspase-1. Particularly since the catalytic cysteine residue is responsible for auto and pro-IL-1β proteolysis.

5. General mechanisms of caspase activation: proteolysis and oligomerization

A recent review summarized the mechanisms involved in activating caspases into self-activation, transactivation by other caspases, or recruitment activation via prodomains [30]. All of these processes ultimately involve proteolysis. Activation of executioner caspases involves removal of the IDL, while activation of other caspases involves removal of both the IDL and the prodomain [25, 26, 31]. Removal of the IDL in executioner caspases results in a conformational change that brings the two active sites of the dimer within proximity to generate an active enzyme [63]. Multiple reports indicate that caspase activation is governed by both dimerization and autoproteolysis [24, 41, 72–75] and that blocking of the dimerization interface with inhibitors prohibits caspase activation [76].

Maturation of IL-1β and induction of pyroptosis are both indicative of caspase activation. Currently, there are two proposed pathways for the activation of caspase-1. The first model proposes that procaspase-1 dimerization is followed by autoproteolytic cleavage while the alternative model has autoproteolysis preceding dimerization [48]. The most recent findings align more with the former dimerization-autoproteolysis model [41, 74]. Recruitment of procaspase-1 to the inflammasome platform facilitates its activation. Various reports have stated that caspases undergo activation via substrate-induced or proximity-induced oligomerization [21, 24, 35, 41, 62, 74, 75] followed by autoproteolytic cleavage [17, 25, 26, 63, 77]. Moreover, the two active sites of the active caspase-1 were found to exhibit cooperativity due to substrate-induced dimerization and activation [74]. Recently, Schroder and colleagues reported the activation of caspase-11 by dimerization and autoproteolytic cleavage of the IDL [41].

Oligomerization plays a vital role in the caspase-1 activation process as originally described by Su and co-workers [78]. Salvesen and Dixit proposed an induced proximity model for activation of initiator caspases [35] based on work from four different groups [79–83]. Using artificially engineered systems that incorporated dimerization domains, studies revealed that proximity-induced oligomerization (via prodomains) led to autoproteolysis and ultimately, caspase-1 activation. Several reviews have described in detail the mechanisms involved in caspase-1 activation and the role played by the prodomain in recruiting caspase-1 to death complexes [21, 25, 26]. One limitation of the induced-proximity model is that it still does not explicitly specify what interactions are involved in the activation process. Later, Salvesen and colleagues would reveal that cleavage alone was not sufficient for activation, but that dimerization of initiator caspases at the inflammasome complex is an important step in the process. Factors that promote dimerization include increased protein concentration, kosmotropes, and the presence of synthetic dimerization domains [24, 45, 62, 73, 84, 85]. Despite the significant scientific and intellectual contribution of the induced-proximity model in outlining how activation of caspases may occur, the model still needs further exploration, mechanistic details, and validation in physiological systems.

6. Role of the prodomain in caspase activation

The prodomain is of particular interest because it contains conserved sequences and plays vital regulatory roles in the mechanisms leading to activation of caspases. One lingering question regarding the role of the prodomain is whether its presence and/or removal is required for caspase activation. Early studies by Thornberry and colleagues suggested the removal of the caspase-1 prodomain was a requirement for dimerization during enzyme activation [17]. Although initial in vitro studies showed that the prodomains of caspases 3 and 7 had no effect on enzymatic activity, in vivo studies would later suggest their removal as an essential step in the activation process [82]. Similarly, the N-terminal fragment of caspase-7 keeps the enzyme inactive, and its removal in vivo allows activation of the enzyme [40]. Mutation and deletion studies of caspase-3 by Ponder & Boise showed the involvement of the prodomain in facilitating its own cleavage. Pre-cleavage at D9 followed by cleavage at D28 resulted in the complete removal of the prodomain, thus leading to the activated enzyme [86].

Other findings reveal the importance of the prodomain in facilitating caspase dimerization. Functional studies performed using WT and C285S mutants of full-length procaspase-1 (p45) and the p30 variant lacking the prodomain showed that dimerization and autoproteolysis only occurred with the p45 [87], but not with p30 fragment [87, 88]. Studies with caspase-2 [89] and caspase-3 [90] also reinforced the role of the prodomain in promoting dimerization and stabilization of the active site thus leading to autoprocessing and enzyme activation. Other studies with caspases 3 [90] and 9 [36] also indicated that maximum catalytic activity was obtained in the presence of the prodomain. Additional findings revealed that the prodomain has stabilizing effects and its removal deactivates the enzyme [41, 75, 88]. Schroder and co-workers demonstrated the importance of the CARD in anchoring caspase-1 to the activating (inflammasome) complex hence its removal causes destabilization and loss of activity [41, 75].

To add complexity to the overall picture, other groups later contradicted these assertions and proposed that the prodomain was dispensable and not necessarily required for caspase activity. According to studies by Shi and coworkers, the presence or absence of the prodomain had no negative effect on the activity of caspase-7. Using an N-terminal deletion mutant, their data showed that the mutant exhibited enzymatic activity similar to that of the wild-type protein [37, 44]. Scheer and colleagues also showed that both the p35 (lacking the CARD) fragment and full-length proenzyme (p45) exhibited similar substrate binding affinities [46]. Interestingly though, one report argued that although the CARD is vital for caspase-1-NLRP3 inflammasome interactions, it is not required for dimerization due to its distant location from the dimer interface [91]. In sum, the prodomain undoubtedly plays some important regulatory and structural roles in the activation of caspases. To what extent the prodomain influences activation of caspases is still a question that remains unanswered and thus calls for further studies.

7. Role of procaspase autoproteolysis in the caspase activation

Studies conducted by Shi and colleagues using caspase-7 highlighted the importance of proteolytic cleavage in promoting enzyme activation [44]. All prior crystal structures were obtained in the presence of inhibitors, yet they were able to determine crystal structures of both the zymogen and the active enzyme without any bound cofactors. Their findings revealed that the distinct structural differences between the pro and active forms of the enzyme were regulated by autoproteolytic removal of the IDL. This event facilitated conformational change and subunit rearrangement to form a functional catalytic site. The crystal structure of the active form without bound inhibitor was quite similar to the one previously obtained in the presence of inhibitor. However, there were subtle differences in the two structures (inhibitor-bound & absence of inhibitor) suggesting that the active caspase may adopt an intermediate conformation [37]. Shi and coworkers summarized their structural findings in several reviews [25, 26, 63]. These results were later confirmed in caspase-1 and caspase-3 by Scheer and coworkers with X-ray crystallography [70, 71]. A recent report demonstrated that cleavage of the IDL is required for both mouse and human forms of caspase-1 [92]. In addition, their data revealed the critical role for autoproteolysis in both ASC-dependent and-independent inflammasomes [92, 93]. Autoproteolysis was also critical for caspase-11 activation in non-canonical inflammasomes [94]. Due to the importance of procaspase-1 autoproteolysis in establishing mature active caspase-1, future investigations may need to explore the molecular details of how this autoproteolytic process is facilitated by the assembly of the inflammasome complex.

8. Elucidation of the exact active caspase-1 structure

8.1. Caspase-1 structure determination in cellular studies

The presence of mature, proteolytically-processed caspase-1 has been used as a marker for inflammasome activation in vitro. Most cell stimulation studies involve probing for cleavage fragments p10 and/or p20. Various publications have reported the time-dependent accumulation of cleaved mature IL-1β as well as caspase-1 p10 and p20 [12, 72, 95–102] fragments in the cell-free supernatants and lysates [103] derived from stimulated immune cells.

Using a two-model system to study caspase-1 activation, Wewers and colleagues discovered that active caspase-1 obtained from stimulated THP-1 cell lysates was less stable and had a shorter half-life compared to caspase-1 released from intact whole THP-1 cells [102]. Caspase-1 from lysates was rapidly cleaved into active p20 species coupled with the release of mature IL-18 within 15 min. Dilution, however, delayed the activity of the enzyme. SEC analysis of released caspase-1 revealed the presence of two species: a (p20p10)2 tetramer ~ 60 kD and a stable high molecular weight (HMW) species > 200 kD. Although western blotting verified the presence of mature caspase in both species, only the HMW species had activity with fluorogenic substrate and this activity was not diminished by immunodepletion [102]. The authors suggested that the HMW species sequestered the active caspase thus preserving its half-life. The observation that mature caspase-1 was detected in the cell medium but not in the cytosol suggests that the components of the inflammasome complex are released into the extracellular milieu [95, 102, 104].

Biotin pull-down probes using caspase-1 substrates/inhibitors (b-VAD-fmk/ b-VAD-cmk) are powerful detection tools used to trap caspase-1 in the active form [68, 75, 102]. Studies by Martin and colleagues showed that processed p10 was detected in the cell-free extracts over a 2-hour period by immunoblotting. The researchers observed a sudden decline in the amount of active species pulled down by the biotin affinity probe [68], raising the question of whether the presence of processed mature caspase-1 is really a good measure for active enzyme. In other studies, Schroder and coworkers utilized these probes to identify p10 and p33 species (and small amounts of full-length p46) as the active forms of caspase-1 [75]. An alternative method for detecting active caspase-1 is the use of fluorochrome-labeled inhibitors of caspases (FLICA) e.g FAM-YVAD-FMK. These fluorescent activity-based probes covalently bind to the active site of caspases. FLICA staining has been extensively used to visualize caspase-1 recruitment and localization to the ASC specks in stimulated/ infected cells and samples derived from patients with inflammatory disorders [72, 75, 105–108]. Non-recombinant cellular systems may provide a more physiological picture of the active caspase-1 structure, but the amount of available material can be limiting for biophysical studies.

8.2. Structural determination in recombinant expression systems

Procaspase-1 is considered to be inactive, but questions regarding its conversion to, and the exact structure of, the active enzyme still remain. Is it the p20p10 heterodimer, the (p20p10)2 heterotetramer (as earlier studies reported), or is it a completely different conformer altogether? While some groups were successful in isolating the active endogenous enzyme from cells, many groups have used recombinant expression systems (mostly E.coli) to express full-length caspase-1 and/ or subunits. Thornberry et al. performed transient expression of caspase-1 in Cos7 cells and used the affinity-purified enzyme in functional assays [17]. Addition of the active, purified recombinant caspase-1 to the full-length procaspase-1 (p45) present in rabbit reticulocyte lysates resulted in proteolysis of the latter yielding multiple cleavage species as verified by immunoblots. Subsequent studies were consistent with these findings [68, 74, 109]. E. coli expressed full-length procaspase-1 isolated from the inclusion bodies and refolded underwent autoproteolysis to form the active heterodimeric species [109]. Incorporation of a caspase-1 inhibitor (SDZ 223–941) in the refolding buffer prevented autoproteolysis. Likewise, refolding the enzyme under non-reducing conditions yielded the same results [109]. The substrate specificity of active caspase-1 appears to be highly dependent on enzyme concentration. Enzyme activity assays conducted by Martin and colleagues using various synthetic tetrapeptide substrates showed that caspase-1 was very selective for WEHD substrate at 4 nM enzyme concentration, but began to show less specificity at 20 nM, with an even greater loss at 100 nM caspase-1 [68]. Caspase-3 and −7 did not exhibit this enzyme concentration-dependent substrate specificity loss. As with the synthetic peptide substrates, caspase-1 displayed the same lack of specificity with multiple cell extract protein substrates when the amount of enzyme is in the range of 20–100 nM. However, at low nanomolar enzyme concentrations (0.5–1 nM), caspase-1 was found to be highly selective for its biological substrate pro-IL-1β. The authors concluded that although caspase-1 tends to lose its substrate specificity at concentrations approaching 100 nM, this is counterbalanced by its rapid inactivation (short half-life) at physiological conditions [68]. To add complexity to the question of the mature active caspase-1 structure, kinetic studies by Wells and colleagues using a refolded recombinant p20p10 complex demonstrated substrate-induced dimer formation (p202p102) and cooperativity between the two active sites of caspase-1 [74]. They proposed an active conformation in the monomeric p20p10 state, but with much greater activity in the dimeric p202p102 conformation. There are some inconsistencies in the nomenclature for mature caspase-1, thus readers must use care in delineating between the p20p10 heterodimer (otherwise called monomer) and p202p102 heterotetramer (referred to as dimer).

Other studies with refolded p20 and p10 caspase-1 subunits revealed the existence of a pH-and inhibitor-dependent (reversible) equilibrium between the heterodimer p20p10 and the p202p102 heterotetramer [110]. Both species were found to be catalytically active. Initially, the heterodimer was the more prominent species, but the presence of reversible and irreversible inhibitors caused a shift in the distribution thus promoting heterotetramer assembly. High substrate concentrations also had a stabilizing effect on the 60 kD conformer [110].

Published reports by other groups, however, contradicted the concept of the heterodimer as the active caspase-1 species. Using a bacterial system, Walker et al expressed caspase-1 p20 and p10 fragments separately. Inclusion bodies solubilization and refolding by dialysis yielded an active enzyme. Subsequent crystal structure studies of recombinant-expressed and refolded active caspase-1 bound to irreversible ketone inhibitor (Ac-YVAD-cmk) at 2.5 Å resolution revealed the active enzyme as a heterotetramer (p202p102) or “homodimer of p20p10 heterodimers” [47]. In the same study they also observed that interactions between the C-terminus of p20 and the N-terminus of p10 stabilized the active conformer [47]. Similar findings were reported by Wilson and colleagues of an x-ray structure at 2.6 Å resolution of the enzyme bound to an aldehyde inhibitor [48]. They also concluded that the active enzyme existed as a heterotetramer and that the active site was formed by complementary p20 and p10 fragments [48]. In further agreement with these findings, Dobo et al. obtained an active heterotetramer using refolded caspase-1 p20 and p10 fragments [111].

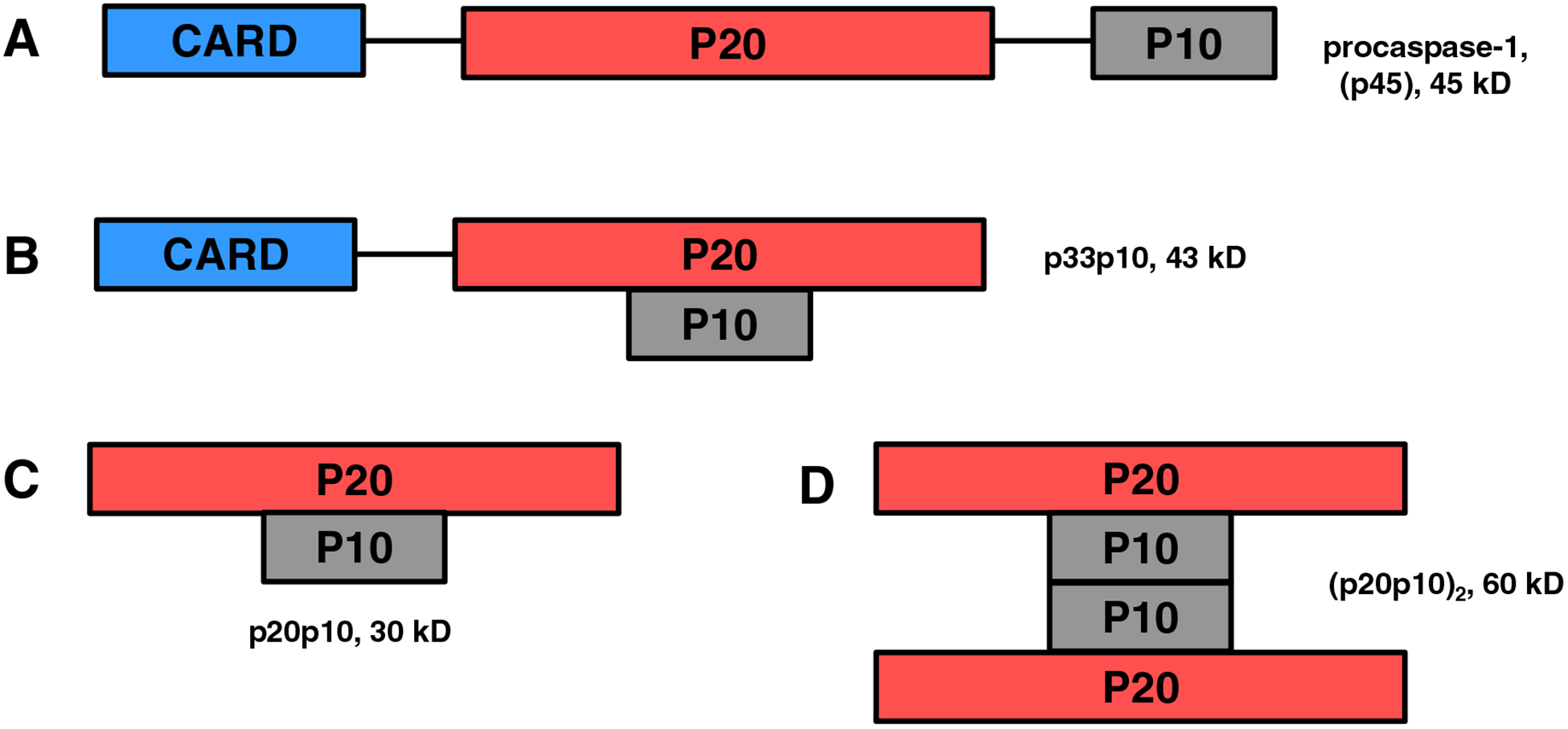

A recent study by Schroder and colleagues has challenged the previous findings regarding the structure of active caspase-1 species [75]. Using a cell-permeable probe to pull down active caspase from stimulated macrophages, they identified a transient p33/p10 heterodimer as the major active species with the full-length p46 as a minor active species. The researchers described the inflammasome as a site that facilitates activation and deactivation of caspase-1 in a controlled manner. They interpreted the generation of p20p10 (via cleavage of the CDL) as a deactivating process that caused its release from the activating inflammasome platform and rendered the species inactive [75]. This alternative hypothesis is in conflict with previous reports that observed enzyme activity with recombinant p20p10. To this point, there have been multiple demonstrated structural assemblies for active caspase-1 (Fig 3). The more recent findings continue to add to the complex and ambiguous nature of the active caspase-1 structure and raise the possibility that there is more than one stable active species. Future investigations may likely identify additional active caspase-1 conformers.

Fig 3. Schematic showing possible active conformers of active caspase-1.

A. Full-length, unprocessed proenzyme which is presumed to have little or no activity. B-D. Various forms of active caspase-1 demonstrated or discussed in the literature, which include (B) proteolytically processed p33p10 with an intact CARD domain for anchoring to the inflammasome, (C) p20p10 heterodimer, and (D) (p20p10)2 heterotetramer with dimerization occurring via the p10-p10 interface.

9. Stability as a key determinant for caspase-1 activity

Under physiological conditions, caspase-1 predominantly exists as a monomer but undergoes dimerization in the presence of a substrate. Various groups have successfully isolated or reconstituted an active enzyme, but the main challenge seems to be the instability of the active caspase-1 especially during refolding procedures. Various reports have demonstrated that caspase substrates and inhibitors tend to stabilize the active enzyme and keep it in the active conformation. The prodomain may also play a role in determining stability of the enzyme. Stability of caspases in vitro is influenced by many variables including enzyme concentration, temperature, pH, ionic strength, inhibitors, buffer type, stabilizing additives, and redox and storage conditions. It is well-established that inclusion of both reversible and irreversible inhibitors (Ac-YVAD-CHO, Ac-YVAD-fmk, malonate) prevents autoproteolytic degradation. The stability of the active enzyme appears to be highly dependent on enzyme concentration. Successfull reconstitution of the active p20p10 heterodimer exhibited a loss of activity upon dilution due to dissociation of the subunits [17]. Caspase-1 activity loss was also observed at concentrations exceeding 2 μM due to autoproteolytic degradation, while concentrations below 30 nM also resulted in dissociation and loss of the p10 subunit [110, 112].

Instability of caspase-1 has been a common observation and several studies found that the use of inhibitors added a stabilizing effect [47, 48, 70, 71]. Synthetic inhibitors were also found to have a stabilizing effect on caspase-3 [113]. Wong and colleagues observed the instability of refolded caspase-1 and attributed it to autolytic degradation and dissociation of the heterotetramer [47]. Addition of an inhibitor stabilized the heterotetramer complex thus they were able to conclude that the substrate provided a stabilizing effect under physiological conditions [47]. Basing on the idea that inhibitors stabilize the active species of the enzyme, Scheer et al. took advantage of inhibitor stabilization and used malonate in the refolding and purification process to obtain a stable enzyme [71]. Similar to the aldehyde caspase-1 inhibitor, malonate stabilized caspase-1, prevented autoproteolysis by blocking the S1 position in the active site, and allowed the enzyme to adopt a stable, open conformation. Due to the low binding affinity between malonate and the enzyme, only concentrations >100 mM had a stabilizing effect without inhibition of caspase-1 activity [71]. The authors proposed that a carboxylic group and a hydrogen bond acceptor are the required prerequisites for binding to the S1 pocket thus justifying the aspartic acid in the P1 position of pro-IL-1β [70, 71]. Interestingly, aspartate also protected caspase-1 from autoproteolysis vis a vis malonate, but succinate (which has similar carboxylate spacing but lacks the ammonia group) was unable to prevent proteolytic degradation [70].

In some cases where two species of the enzyme exist in equilibrium, manipulating the conditions promotes stability of one species over the other. For example, inhibitors and high substrate concentrations favored the caspase-1 heterotetramer over the heterodimer [110]. In a similar scenario, Feeny and Clark showed that caspase-3 active heterotetramer was less stable than procaspase homodimer as shown by the higher pH range at which dissociation of the heterotetramer occurred (the threshold being pH 4.5) [90]. They attributed the decrease in stability to the removal of the prodomain and the linker fragment which confer stability. Although both the pro-enzyme and the heterotetramer were not affected by ionic strength, stability of the p20p10 heterodimer was dependent on concentration of cations (K+, Na+, NH4+). The authors concluded that removal of the prodomain (and the linker region in effector caspases) causes the processed enzyme to be sensitive to both pH and ion concentrations [90].

Despite numerous studies that have shown that the presence of either a substrate or an inhibitor stabilizes the active enzyme, studies conducted by Dobo et al. revealed otherwise. Studies with refolded p20 and p10 and cowpox serpin crmA, a caspase-1 inhibitor, indicated that the inhibitor caused dissociation of the active heterotetramer [111]. The potential explanation was disruption of the p20-p10 and p10-p10 interfaces thereby resulting in the loss of the p10 subunit. Another study of stability utilized crosslinking experiments with recombinant active caspase-1 and demonstrated that the loss of caspase-1 activity was associated with the loss of quaternary structure at low enzyme concentrations (< 10 nM) [68]. In the same study, the enzyme proved to be very unstable at high temperatures with a half-life of 9 min at 37 °C compared to caspase-3 and −7 with half-lives of 8- and −11 h, respectively. Furthermore, caspase-1 activity captured from THP-1 extracts with biotin-VAD-fmk also exhibited a time-dependent decline. The researchers were able to retain enzymatic activity of recombinant caspase-1 by conducting assays at 4 °C in the presence of the low concentrations of irreversible inhibitor Z-VAD-fmk [68]. In conclusion, high enzyme concentrations tend to promote autoproteolysis of the active caspase-1 structure and loss of activity, while very low concentrations result in subunit dissociation and loss of activity. Thus, it remains a challenge to obtain and clearly define the optimum conditions required to maintain a stable, active caspase-1 enzyme.

10. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

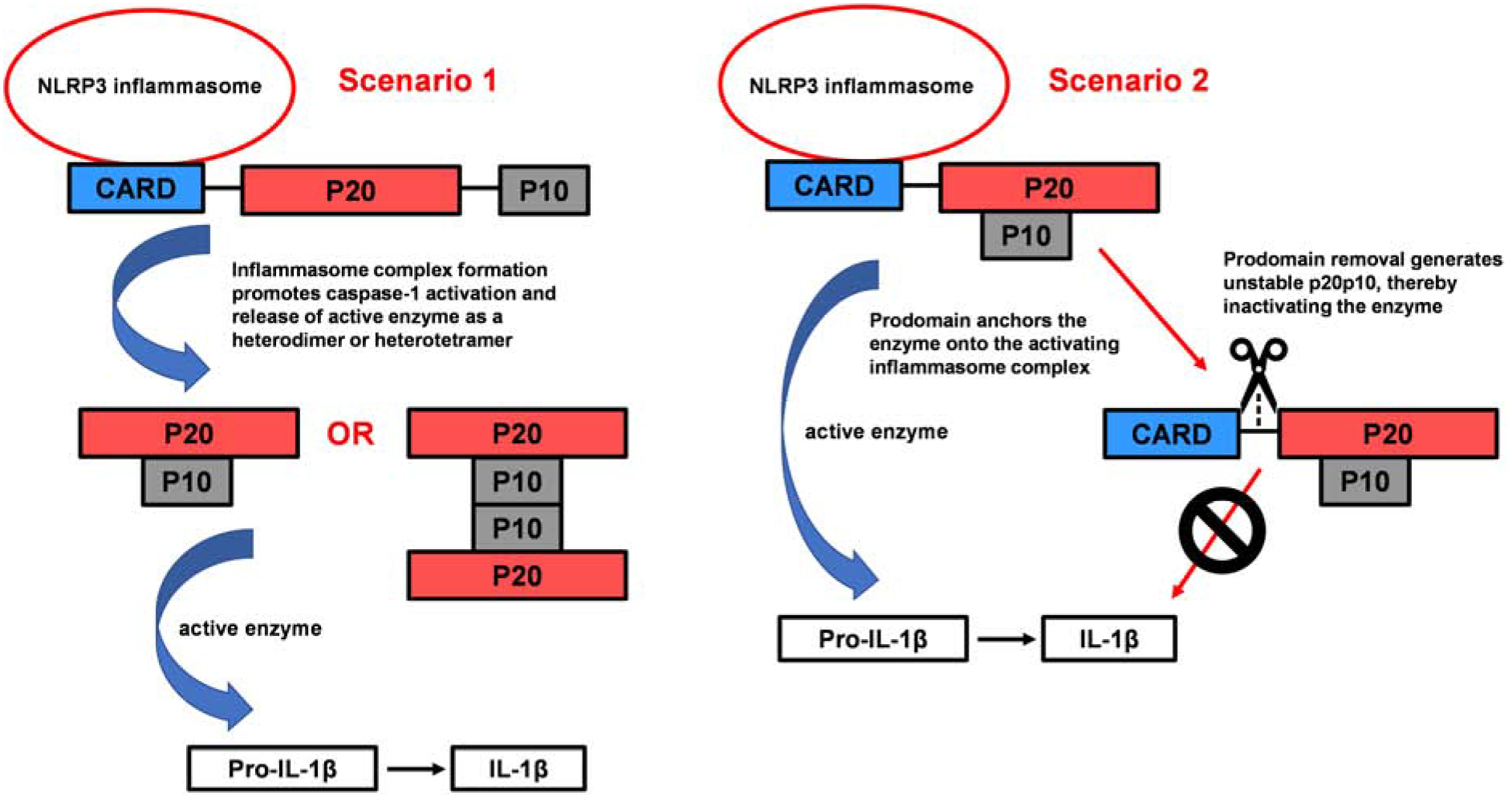

The exact structural components of the active caspase-1 enzyme have either not been fully established or may vary depending on the conditions. The induced-proximity model is a widely-accepted model for caspase activation, yet there are still outstanding questions regarding its relevance to physiological processes that need further exploration. For some time, the p20p10 species has been known as the active form of caspase-1. However, recent findings not only identified p33p10 as the active form of the enzyme but also described the p20p10 species as an inactive conformer instead. The recent findings pose new questions and suggest that there may be more than one form of active caspase-1. The conventional model for caspase-1 activation (Scenario 1) and newer findings (Scenario 2) are depicted in Fig 4. Possible explanations for the conflicting findings could be variability in experimental conditions and cellular systems used. As seen in some reports, factors such as enzyme and/or substrate concentrations, effect of inhibitors (and amounts used), ionic concentrations, pH, and temperature can determine the type of stable species of caspase-1. Therefore, slight changes in experimental conditions may influence the formation of various stable and active conformers of caspase-1. Differences in laboratory and physiological caspase-1 concentrations also likely impacts its quaternary structure. Thus, the conflicting, or distinct, findings may only be reconciled by an established set of solution conditions or perhaps further investigation into potential physiological regulation of active structure conformation(s).

Fig 4. Potential mechanisms of caspase-1.

Inflammasome complex formation (NLRP3, ASC, procaspase-1) facilitates caspase-1 activation via induced proximity-mediated autoproteolysis. Scenario 1 is a process whereby prodomain removal is a prerequisite for obtaining the active enzyme. Liberated p20 and p10 subunits can recombine to form either the heterodimer or heterotetramer (both which have been found to have enzymatic activity). Presumably, removal of the CARD domain linker (CDL) causes release of the enzyme from the inflammasome complex for subsequent substrate catalysis. Scenario 2 suggests the inflammasome as the site for pro-IL-1β cleavage. The CARD anchors the active caspase onto the inflammasome, but following CDL processing and CARD removal, the enzyme is dissociated from the complex and inactivated.

Other intriguing questions include: (1) Since the inflammasome is known as the hub for caspase-1 activation, does that restrict the localization of pro-IL-1β processing to the intact inflammasome complex? Or is there a process that provides for diffusion or transport of mature caspase-1 to other substrate locations? (2) What are the exact steps that lead to caspase-1 activation? More specifically, what is the trigger for procaspase-1 autoproteolysis that ultimately leads to mature active caspase-1? Perhaps there is a mechanism that prevents autoproteolysis until NLRP3/ASC interact with the procaspase-1 CARD. (3) Finally, as some studies have demonstrated caspase-1 activity with recombinant proenzyme, those findings beg the question of how assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome regulates, enhances, or is required for caspase-1 activity. Ultimately, a better understanding of the structural aspects of mature active caspase-1 will allow for improved rational design of therapeutic molecules that will likely have an impact on diverse inflammatory disorders. These disorders include obesity, type II diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple neurodegenerative diseases, and heart and liver disease [114]. In almost all of these disease processes, caspase-1 or IL-1β is directly implicated. In conclusion, the NLRP3 inflammasome is a complex biological system that presents scientific challenges in its continued study. The final step in this system is the formation of mature caspase-1. Determination of the regulatory and structural aspects that create the active enzyme will guide further exploration into the control of this particular proinflammatory pathway.

Funding Source/Acknowledgements

This review was aided by research supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15GM119070 (MRN).

Abbreviations

- AcYVAD-CHO

acetyl-tyrosine-valine-alanine-aspartic acid-aldehyde caspase-1 inhibitor

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

amyloid-β protein

- ASC

apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD

- BiolD

proximity-dependent biotinylation assay

- b-VAD-cmk/ fmk

biotin valyl-alaninyl-aspartyl chloro/fluoromethylketone

- CARD

caspase recruitment domain

- cDNA

copy deoxyribonucleic acid

- CDL

card domain linker

- CED-3

cell death protein 3

- DED

death effector domain

- FLICA

fluorescent-labeled inhibitor of caspases

- HMW

high molecular weight

- IL-1β

interleukin 1-beta

- IL-18

interleukin 18

- IDL

interdomain linker

- NLRP3

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-, leucine-rich repeat- and pyrin domain (PYD)-containing 3

- PYD

pyrin domain

- SEC

size-exclusion chromatography

- WT

wild type

- z-VAD-fmk

carbobenzoxy-valyl-alanyl-aspartyl-[O-methyl]-fluoromethylketone

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Cassel SL, Joly S, Sutterwala FS, The NLRP3 inflammasome: a sensor of immune danger signals, Seminars in immunology, 21 (2009) 194–198, 10.1016/j.smim.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sutterwala FS, Haasken S, Cassel SL, Mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation, Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1319 (2014) 82–95, 10.1111/nyas.12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM, Mechanisms and functions of inflammasomes, Cell, 157 (2014) 1013–1022, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lechtenberg BC, Mace PD, Riedl SJ, Structural mechanisms in NLR inflammasome signaling, Curr Opin Struct Biol, 29C (2014) 17–25, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ruland J, Inflammasome: Putting the Pieces Together, Cell, 156 (2014) 1127–1129, 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].He Y, Hara H, Nunez G, Mechanism and Regulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation, Trends Biochem Sci, 41 (2016) 1012–1021, 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Shao BZ, Xu ZQ, Han BZ, Su DF, Liu C, NLRP3 inflammasome and its inhibitors: a review, Front Pharmacol, 6 (2015) 262, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gold M, Khoury JE, β-amyloid, Microglia and the Inflammasome in Alzheimer’s Disease, Seminars in immunopathology, 37 (2015) 607–611, 10.1007/s00281-015-0518-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Heneka MT, Carson MJ, Khoury JE, Landreth GE, Brosseron F, Feinstein DL, Jacobs AH, Wyss-Coray T, Vitorica J, Ransohoff RM, Herrup K, Frautschy SA, Finsen B, Brown GC, Verkhratsky A, Yamanaka K, Koistinaho J, Latz E, Halle A, Petzold GC, Town T, Morgan D, Shinohara ML, Perry VH, Holmes C, Bazan NG, Brooks DJ, Hunot S, Joseph B, Deigendesch N, Garaschuk O, Boddeke E, Dinarello CA, Breitner JC, Cole GM, Golenbock DT, Kummer MP, Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease, The Lancet Neurology, 14 (2015) 388–405, 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Heneka MT, Golenbock DT, Latz E, Innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease, Nat Immunol, 16 (2015) 229–236, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Heneka MT, Kummer MP, Stutz A, Delekate A, Schwartz S, Vieira-Saecker A, Griep A, Axt D, Remus A, Tzeng TC, Gelpi E, Halle A, Korte M, Latz E, Golenbock DT, NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice, Nature, 493 (2013) 674–678, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J, The Inflammasome: A Molecular Platform Triggering Activation of Inflammatory Caspases and Processing of proIL-β, Molecular Cell, 10 (2002) 417–426, 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Masumoto J, Taniguchi S.i., Ayukawa K, Sarvotham H, Kishino T, Niikawa N, Hidaka E, Katsuyama T, Higuchi T, Sagara J, ASC, a Novel 22-kDa Protein, Aggregates during Apoptosis of Human Promyelocytic Leukemia HL-60 Cells, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 274 (1999) 33835–33838, 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Srinivasula SM, Poyet J-L, Razmara M, Datta P, Zhang Z, Alnemri ES, The PYRIN-CARD Protein ASC Is an Activating Adaptor for Caspase-1, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277 (2002) 21119–21122, 10.1074/jbc.C200179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Moretti J, Blander JM, Increasing complexity of NLRP3 inflammasome regulation, J Leukoc Biol, (2020) 10.1002/jlb.3mr0520-104rr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schneider KS, Groß CJ, Dreier RF, Saller BS, Mishra R, Gorka O, Heilig R, Meunier E, Dick MS, Ćiković T, Sodenkamp J, Médard G, Naumann R, Ruland J, Kuster B, Broz P, Groß O, The Inflammasome Drives GSDMD-Independent Secondary Pyroptosis and IL-1 Release in the Absence of Caspase-1 Protease Activity, Cell Reports, 21 (2017) 3846–3859, 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Thornberry NA, Bull HG, Calaycay JR, Chapman KT, Howard AD, Kostura MJ, Miller DK, Molineaux SM, Weidner JR, Aunins J, et al. , A novel heterodimeric cysteine protease is required for interleukin-1b processing in monocytes, Nature, 356 (1992) 768–774, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cerretti DP, Kozlosky CJ, Mosley B, Nelson N, Van Ness K, Greenstreet TA, March CJ, Kronheim T Druck LA Cannizzaro a. et al. , Molecular cloning of the interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme, Science, 256 (1992) 97, 10.1126/science.1373520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Black RA, Kronheim SR, Sleath PR, Activation of interleukin-1β by a co-induced protease, FEBS Letters, 247 (1989) 386–390, 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81376-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kostura MJ, Tocci MJ, Limjuco G, Chin J, Cameron P, Hillman AG, Chartrain NA, Schmidt JA, Identification of a monocyte specific pre-interleukin 1 beta convertase activity, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 86 (1989) 5227–5231, 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kumar S, Mechanisms mediating caspase activation in cell death, Cell Death & Differentiation, 6 (1999) 1060–1066, 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Broz P, Dixit VM, Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling, Nat Rev Immunol, 16 (2016) 407–420, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Winkler S, Rösen-Wolff A, Caspase-1: an integral regulator of innate immunity, Seminars in immunopathology, 37 (2015) 419–427, 10.1007/s00281-015-0494-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boatright KM, Salvesen GS, Mechanisms of caspase activation, Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 15 (2003) 725–731, 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shi Y, Mechanisms of Caspase Activation and Inhibition during Apoptosis, Molecular Cell, 9 (2002) 459–470, 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shi Y, Caspase Activation: Revisiting the Induced Proximity Model, Cell, 117 (2004) 855–858, 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].McIlwain DR, Berger T, Mak TW, Caspase functions in cell death and disease, Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 5 (2013) a008656–a008656, 10.1101/cshperspect.a008656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shalini S, Dorstyn L, Dawar S, Kumar S, Old, new and emerging functions of caspases, Cell Death & Differentiation, 22 (2015) 526–539, 10.1038/cdd.2014.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Julien O, Wells JA, Caspases and their substrates, Cell death and differentiation, 24 (2017) 1380–1389, 10.1038/cdd.2017.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Vigneswara VA, Z, The Role of Caspase-2 in Regulating Cell Fate, Cells, 9 (2020) 10.3390/cells9051259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Vaidya S, Velázquez-Delgado EM, Abbruzzese G, Hardy JA, Substrate-induced conformational changes occur in all cleaved forms of caspase-6, Journal of molecular biology, 406 (2011) 75–91, 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dagbay KB, Hardy JA, Multiple proteolytic events in caspase-6 self-activation impact conformations of discrete structural regions, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, (2017) 201704640, 10.1073/pnas.1704640114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Parrish AB, Freel CD, Kornbluth S, Cellular Mechanisms Controlling Caspase Activation and Function, Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 5 (2013) 10.1101/cshperspect.a008672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhou Q, Salvesen GS, Activation of pro-caspase-7 by serine proteases includes a non-canonical specificity, The Biochemical journal, 324 (Pt 2) (1997) 361–364, 10.1042/bj3240361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Salvesen GS, Dixit VM, Caspase activation: the induced-proximity model, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96 (1999) 10964–10967, 10.1073/pnas.96.20.10964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Stennicke HR, Deveraux QL, Humke EW, Reed JC, Dixit VM, Salvesen GS, Caspase-9 Can Be Activated without Proteolytic Processing, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 274 (1999) 8359–8362, 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chai J, Shiozaki E, Srinivasula SM, Wu Q, Dataa P, Alnemri ES, Shi Y, Structural Basis of Caspase-7 Inhibition by XIAP, Cell, 104 (2001) 769–780, 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Stennicke HR, Jürgensmeier JM, Shin H, Deveraux Q, Wolf BB, Yang X, Zhou Q, Ellerby HM, Ellerby LM, Bredesen D, Green DR, Reed JC, Froelich CJ, Salvesen GS, Pro-caspase-3 Is a Major Physiologic Target of Caspase-8, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 273 (1998) 27084–27090, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Colussi PA, Harvey NL, Shearwin-Whyatt LM, Kumar S, Conversion of procaspase-3 to an autoactivating caspase by fusion to the caspase-2 prodomain, The Journal of biological chemistry, 273 (1998) 26566–26570, 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Denault J-B, Salvesen GS, Human Caspase-7 Activity and Regulation by Its N-terminal Peptide, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278 (2003) 34042–34050, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ross C, Chan AH, Von Pein J, Boucher D, Schroder K, Dimerization and autoprocessing induce caspase-11 protease activation within the non-canonical inflammasome, Life science alliance, 1 (2018) e201800237–e201800237, 10.26508/lsa.201800237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Roschitzki-Voser H, Schroeder T, Lenherr ED, Frolich F, Schweizer A, Donepudi M, Ganesan R, Mittl PR, Baici A, Grutter MG, Human caspases in vitro: expression, purification and kinetic characterization, Protein Expr Purif, 84 (2012) 236–246, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Siegel RM, Martin DA, Zheng L, Ng SY, Bertin J, Cohen J, Lenardo MJ, Death-effector filaments: novel cytoplasmic structures that recruit caspases and trigger apoptosis, The Journal of cell biology, 141 (1998) 1243–1253, 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chai J, Wu Q, Shiozaki E, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES, Shi Y, Crystal Structure of a Procaspase-7 Zymogen: Mechanisms of Activation and Substrate Binding, Cell, 107 (2001) 399–407, 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00544-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fuentes-Prior P, Guy S Salvesen, The protein structures that shape caspase activity, specificity, activation and inhibition, Biochemical Journal, 384 (2004) 201, 10.1042/BJ20041142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Elliott JM, Rouge L, Wiesmann C, Scheer JM, Crystal structure of procaspase-1 zymogen domain reveals insight into inflammatory caspase autoactivation, J Biol Chem, 284 (2009) 6546–6553, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Walker NPC, Talanian RV, Brady KD, Dang LC, Bump NJ, Ferenza CR, Franklin S, Ghayur T, Hackett MC, Hammill LD, Herzog L, Hugunin M, Houy W, Mankovich JA, McGuiness L, Orlewicz E, Paskind M, Pratt CA, Reis P, Summani A, Terranova M, Welch JP, Xiong L, Möller A, Tracey DE, Kamen R, Wong WW, Crystal structure of the cysteine protease interleukin-1β-converting enzyme: A (p20/p10)2 homodimer, Cell, 78 (1994) 343–352, 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wilson KP, Black J-AF, Thomson JA, Kim EE, Griffith JP, Navia MA, Murcko MA, Chambers SP, Aldape RA, Raybuck SA, Livingston DJ, Structure and mechanism of interleukin-lβ converting enzyme, Nature, 370 (1994) 270–275, 10.1038/370270a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Miller DK, Ayala JM, Egger LA, Raju SM, Yamin TT, Ding GJ, Gaffney EP, Howard AD, Palyha OC, Rolando AM, Purification and characterization of active human interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme from THP.1 monocytic cells, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 268 (1993) 18062–18069, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kapplusch F, Schulze F, Rabe-Matschewsky S, Russ S, Herbig M, Heymann MC, Schoepf K, Stein R, Range U, Rösen-Wolff A, Winkler S, Hedrich CM, Guck J, Hofmann SR, CASP1 variants influence subcellular caspase-1 localization, pyroptosome formation, pro-inflammatory cell death and macrophage deformability, Clinical Immunology, 208 (2019) 108232, 10.1016/j.clim.2019.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Paronetto MP, Passacantilli I, Sette C, Alternative splicing and cell survival: from tissue homeostasis to disease, Cell Death & Differentiation, 23 (2016) 1919–1929, 10.1038/cdd.2016.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Feng Q, Li P, Leung PCK, Auersperg N, Caspase-1ζ, a new splice variant of the caspase-1 gene, Genomics, 84 (2004) 587–591, 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Alnemri ES, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Litwack G, Cloning and Expression of Four Novel Isoforms of Human Interleukin-1β Converting Enzyme with Different Apoptotic Activities, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 270 (1995) 4312–4317, 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tingsborg S, Ziólkowska M, Zetterström M, Hasanvan H, Bartfai T, Regulation of ICE activity and ICE isoforms by LPS, Molecular Psychiatry, 2 (1997) 122–124, 10.1038/sj.mp.4000224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Anathy V, Roberson EC, Guala AS, Godburn KE, Budd RC, Janssen-Heininger YMW, Redox-based regulation of apoptosis: S-glutathionylation as a regulatory mechanism to control cell death, Antioxidants & redox signaling, 16 (2012) 496–505, 10.1089/ars.2011.4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Plenchette S, Romagny S, Laurens V, Bettaieb A, S-nitrosylation in TNF superfamily signaling pathway: Implication in cancer, Redox Biology, 6 (2015) 507–515, 10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zamaraev AV, Kopeina GS, Prokhorova EA, Zhivotovsky B, Lavrik IN, Posttranslational Modification of Caspases: The Other Side of Apoptosis Regulation, Trends in Cell Biology, 27 (2017) 322–339, 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Lermant A, Murdoch CE, Cysteine Glutathionylation Acts as a Redox Switch in Endothelial Cells, Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 8 (2019) 315, 10.3390/antiox8080315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gong T, Jiang W, Zhou R, Control of Inflammasome Activation by Phosphorylation, Trends Biochem Sci, (2018) 10.1016/j.tibs.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Song N, Li T, Regulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome by Phosphorylation, Frontiers in immunology, 9 (2018) 2305–2305, 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Basak C, Pathak SK, Bhattacharyya A, Mandal D, Pathak S, Kundu M, NFkB- and C/EBPb-driven interleukin-1b gene expression and PAK1-mediated caspase-1 activation play essential roles in interleukin-1b release from Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages, J Biol Chem, 280 (2005) 4279–4288, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Renatus M, Stennicke HR, Scott FL, Liddington RC, Salvesen GS, Dimer formation drives the activation of the cell death protease caspase 9, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98 (2001) 14250–14255, 10.1073/pnas.231465798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Riedl SJ, Shi Y, Molecular mechanisms of caspase regulation during apoptosis, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 5 (2004) 897–907, 10.1038/nrm1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Pop C, Fitzgerald P, Green DR, Salvesen GS, Role of Proteolysis in Caspase-8 Activation and Stabilization, Biochemistry, 46 (2007) 4398–4407, 10.1021/bi602623b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Thornberry NA, Molineaux SM, Interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme: a novel cysteine protease required for IL-1 beta production and implicated in programmed cell death, Protein Science : A Publication of the Protein Society, 4 (1995) 3–12, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Thornberry NA, Peterson EP, Zhao JJ, Howard AD, Griffin PR, Chapman KT, Inactivation of Interleukin-1.beta. Converting Enzyme by Peptide (Acyloxy)methyl Ketones, Biochemistry, 33 (1994) 3934–3940, 10.1021/bi00179a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Thornberry NA, Rano TA, Peterson EP, Rasper DM, Timkey T, Garcia-Calvo M, Houtzager VM, Nordstrom PA, Roy S, Vaillancourt JP, Chapman KT, Nicholson DW, A combinatorial approach defines specificities of members of the caspase family and granzyme B. Functional relationships established for key mediators of apoptosis, J Biol Chem, 272 (1997) 17907–17911, 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Walsh JG, Logue SE, Luthi AU, Martin SJ, Caspase-1 promiscuity is counterbalanced by rapid inactivation of processed enzyme, J Biol Chem, 286 (2011) 32513–32524, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Sleath PR, Hendrickson RC, Kronheim SR, March CJ, Black RA, Substrate specificity of the protease that processes human interleukin-1 beta, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 265 (1990) 14526–14528, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Romanowski MJ, Scheer JM, O’Brien T, McDowell RS, Crystal structures of a ligand-free and malonate-bound human caspase-1: implications for the mechanism of substrate binding, Structure (London, England : 1993), 12 (2004) 1361–1371, 10.1016/j.str.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Scheer JM, Wells JA, Romanowski MJ, Malonate-assisted purification of human caspases, Protein Expression and Purification, 41 (2005) 148–153, 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Broz P, von Moltke J, Jones JW, Vance RE, Monack DM, Differential requirement for Caspase-1 autoproteolysis in pathogen-induced cell death and cytokine processing, Cell host & microbe, 8 (2010) 471–483, 10.1016/j.chom.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Oberst A, Pop C, Tremblay AG, Blais V, Denault J-B, Salvesen GS, Green DR, Inducible Dimerization and Inducible Cleavage Reveal a Requirement for Both Processes in Caspase-8 Activation, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 285 (2010) 16632–16642, 10.1074/jbc.M109.095083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Datta D, McClendon CL, Jacobson MP, Wells JA, Substrate and Inhibitor-induced Dimerization and Cooperativity in Caspase-1 but Not Caspase-3, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 288 (2013) 9971–9981, 10.1074/jbc.M112.426460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Boucher D, Monteleone M, Coll RC, Chen KW, Ross CM, Teo JL, Gomez GA, Holley CL, Bierschenk D, Stacey KJ, Yap AS, Bezbradica JS, Schroder K, Caspase-1 self-cleavage is an intrinsic mechanism to terminate inflammasome activity, The Journal of Experimental Medicine, (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Huber KL, Ghosh S, Hardy JA, Inhibition of caspase-9 by stabilized peptides targeting the dimerization interface, Biopolymers, 98 (2012) 451–465, 10.1002/bip.22080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Martinon F, Mayor A, Tschopp J, The Inflammasomes: Guardians of the Body, Annual Review of Immunology, 27 (2009) 229–265, 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Gu Y, Wu J, Faucheu C, Lalanne JL, Diu A, Livingston DJ, Su MS, Interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme requires oligomerization for activity of processed forms in vivo, The EMBO journal, 14 (1995) 1923–1931, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].MacCorkle RA, Freeman KW, Spencer DM, Synthetic activation of caspases: artificial death switches, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95 (1998) 3655–3660, 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES, Autoactivation of procaspase-9 by Apaf-1-mediated oligomerization, Mol Cell, 1 (1998) 949–957, 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Muzio M, Stockwell BR, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS, Dixit VM, An Induced Proximity Model for Caspase-8 Activation, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 273 (1998) 2926–2930, 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Yang X, Chang HY, Baltimore D, Autoproteolytic Activation of Pro-Caspases by Oligomerization, Molecular Cell, 1 (1998) 319–325, 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Yang X, Chang HY, Baltimore D, Essential Role of CED-4 Oligomerization in CED-3 Activation and Apoptosis, Science, 281 (1998) 1355, 10.1126/science.281.5381.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Riedl SJ, Salvesen GS, The apoptosome: signalling platform of cell death, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 8 (2007) 405–413, 10.1038/nrm2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Wachmann K, Pop C, van Raam BJ, Drag M, Mace PD, Snipas SJ, Zmasek C, Schwarzenbacher R, Salvesen GS, Riedl SJ, Activation and Specificity of Human Caspase-10, Biochemistry, 49 (2010) 8307–8315, 10.1021/bi100968m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Ponder KG, Boise LH, The prodomain of caspase-3 regulates its own removal and caspase activation, Cell Death Discovery, 5 (2019) 56, 10.1038/s41420-019-0142-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Van Criekinge W, Beyaert R, Van de Craen M, Vandenabeele P, Schotte P, De Valck D, Fiers W, Functional Characterization of the Prodomain of Interleukin1β-converting Enzyme, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 271 (1996) 27245–27248, 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Kersse K, Lamkanfi M, Bertrand MJ, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P, Interaction patches of procaspase-1 caspase recruitment domains (CARDs) are differently involved in procaspase-1 activation and receptor-interacting protein 2 (RIP2)-dependent nuclear factor kappaB signaling, J Biol Chem, 286 (2011) 35874–35882, 10.1074/jbc.M111.242321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Butt AJ, Harvey NL, Parasivam G, Kumar S, Dimerization and Autoprocessing of the Nedd2 (Caspase-2) Precursor Requires both the Prodomain and the Carboxyl-terminal Regions, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 273 (1998) 6763–6768, 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Feeney B, Clark AC, Reassembly of Active Caspase-3 Is Facilitated by the Propeptide, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 280 (2005) 39772–39785, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Bauernfeind F, Ablasser A, Bartok E, Kim S, Schmid-Burgk J, Cavlar T, Hornung V, Inflammasomes: current understanding and open questions, Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 68 (2011) 765–783, 10.1007/s00018-010-0567-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Ball DP, Taabazuing CY, Griswold AR, Orth EL, Rao SD, Kotliar IB, Vostal LE, Johnson DC, Bachovchin DA, Caspase-1 interdomain linker cleavage is required for pyroptosis, Life science alliance, 3 (2020) e202000664, 10.26508/lsa.202000664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Ball DP, Taabazuing CY, Griswold AR, Orth EL, Rao SD, Kotliar IB, Johnson DC, Bachovchin DA, Human caspase-1 autoproteolysis is required for ASC-dependent and -independent inflammasome activation, bioRxiv, (2019) 681304, 10.1101/681304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Lee BL, Stowe IB, Gupta A, Kornfeld OS, Roose-Girma M, Anderson K, Warming S, Zhang J, Lee WP, Kayagaki N, Caspase-11 auto-proteolysis is crucial for noncanonical inflammasome activation, Journal of Experimental Medicine, 215 (2018) 2279–2288, 10.1084/jem.20180589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Kahlenberg JM, Dubyak GR, Mechanisms of caspase-1 activation by P2X7 receptor-mediated K+ release, American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology, 286 (2004) C1100–C1108, 10.1152/ajpcell.00494.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Martinon F, Pétrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J, Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome, Nature, 440 (2006) 237–241, 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization, Nature immunology, 9 (2008) 847–856, 10.1038/ni.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Baroja-Mazo A, Martin-Sanchez F, Gomez AI, Martinez CM, Amores-Iniesta J, Compan V, Barbera-Cremades M, Yague J, Ruiz-Ortiz E, Anton J, Bujan S, Couillin I, Brough D, Arostegui JI, Pelegrin P, The NLRP3 inflammasome is released as a particulate danger signal that amplifies the inflammatory response, Nat Immunol, 15 (2014) 738–748, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Compan V, Baroja-Mazo A, López-Castejón G, Gomez Ana I., Martínez Carlos M., Angosto D, Montero María T., Herranz Antonio S., Bazán E, Reimers D, Mulero V, Pelegrín P, Cell Volume Regulation Modulates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation, Immunity, 37 (2012) 487–500, 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Muñoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martínez-Colón G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM, Núñez G, K(+) efflux is the Common Trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome Activation by Bacterial Toxins and Particulate Matter, Immunity, 38 (2013) 1142–1153, 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Dick MS, Sborgi L, Ruhl S, Hiller S, Broz P, ASC filament formation serves as a signal amplification mechanism for inflammasomes, Nat Commun, 7 (2016) 11929, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Shamaa OR, Mitra S, Gavrilin MA, Wewers MD, Monocyte Caspase-1 Is Released in a Stable, Active High Molecular Weight Complex Distinct from the Unstable Cell Lysate-Activated Caspase-1, PLoS One, 10 (2015) e0142203, 10.1371/journal.pone.0142203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].O’Brien M, Moehring D, Muñoz-Planillo R, Núñez G, Callaway J, Ting J, Scurria M, Ugo T, Bernad L, Cali J, Lazar D, A bioluminescent caspase-1 activity assay rapidly monitors inflammasome activation in cells, Journal of Immunological Methods, 447 (2017) 1–13, 10.1016/j.jim.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Laliberte RE, Eggler J, Gabel CA, ATP Treatment of Human Monocytes Promotes Caspase-1 Maturation and Externalization, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 274 (1999) 36944–36951, 10.1074/jbc.274.52.36944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Grabarek J, Darzynkiewicz Z, In situ activation of caspases and serine proteases during apoptosis detected by affinity labeling their enzyme active centers with fluorochrome-tagged inhibitors, Exp Hematol, 30 (2002) 982–989, 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00886-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Smolewski P, Grabarek J, Halicka HD, Darzynkiewicz Z, Assay of caspase activation in situ combined with probing plasma membrane integrity to detect three distinct stages of apoptosis, Journal of Immunological Methods, 265 (2002) 111–121, 10.1016/S0022-1759(02)00074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Darzynkiewicz Z, Pozarowski P, Lee BW, Johnson GL, Fluorochrome-labeled inhibitors of caspases: convenient in vitro and in vivo markers of apoptotic cells for cytometric analysis, Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.), 682 (2011) 103–114, 10.1007/978-1-60327-409-8_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Guo C, Fu R, Wang S, Huang Y, Li X, Zhou M, Zhao J, Yang N, NLRP3 inflammasome activation contributes to the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis, Clin Exp Immunol, 194 (2018) 231–243, 10.1111/cei.13167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Ramage P, Cheneval D, Chvei M, Graff P, Hemmig R, Heng R, Kocher HP, Mackenzie A, Memmert K, Revesz L, Wishart W, Expression, Refolding, and Autocatalytic Proteolytic Processing of the Interleukin-1-converting Enzyme Precursor, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 270 (1995) 9378–9383, 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Talanian RV, Dang LC, Ferenz CR, Hackett MC, Mankovich JA, Welch JP, Wong WW, Brady KD, Stability and oligomeric equilibria of refolded interleukin-1b converting enzyme, J Biol Chem, 271 (1996) 21853–21858, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Dobo J, Swanson R, Salvesen GS, Olson ST, Gettins PG, Cytokine response modifier a inhibition of initiator caspases results in covalent complex formation and dissociation of the caspase tetramer, J Biol Chem, 281 (2006) 38781–38790, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Dang LC, Talanian RV, Banach D, Hackett MC, Gilmore JL, Hays SJ, Mankovich JA, Brady KD, Preparation of an Autolysis-Resistant Interleukin-1β Converting Enzyme Mutant, Biochemistry, 35 (1996) 14910–14916, 10.1021/bi9617771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Tawa P, Hell K, Giroux A, Grimm E, Han Y, Nicholson DW, Xanthoudakis S, Catalytic activity of caspase-3 is required for its degradation: stabilization of the active complex by synthetic inhibitors, Cell Death & Differentiation, 11 (2004) 439–447, 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Fusco R, Siracusa R, Genovese T, Cuzzocrea S, Di Paola R, Focus on the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in diseases, Int J Mol Sci, 21 (2020) 10.3390/ijms21124223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]