Abstract

Ureaplasma species, including Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum, are challenging to culture and maintain. Here, we describe a novel bioreactor for growing high-titer liquid Ureaplasma cultures in a stable manner.

Keywords: Ureaplasma, Ureaplasma parvum, Growth, Culture, Bioreactor

Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum are species of the Ureaplasma genus, one of two genera, along with Mycoplasma, in the family Mycoplasmataceae. Ureaplasma species are primarily differentiated from Mycoplasma species by their ability to hydrolyze urea into ammonia and CO2 for ATP synthesis. Indeed, it is estimated that 95% of all ATP synthesized by Ureaplasma species is generated in this fashion, making urea a requirement for growth [1].

Although U. parvum and U. urealyticum are typically regarded as commensal organisms of the urogenital tract of humans, they can cause human disease, including urethritis [2, 3]; pregnancy complications, most notably increased rates of pre-term birth [4]; neonatal infections, including bacteremia, pneumonia, and meningoencephalitis [5–7]; necrotizing soft tissue and other wound infections [8, 9]; and endocarditis [10]. They have also recently been recognized as causal agents of fatal hyperammonemia that occurs in approximately 4% of lung transplant recipients [11, 12], in hematopoietic stem cell transplantations [12], and in other immunocompromised patients, such as those with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia [13]. Ureaplasma infection may also be responsible for unexplained hyperammonemia described in other transplant patient populations [14–29]. Ureaplasma species can be challenging to culture; given the increasing recognition of Ureaplasma species as pathogens in a wide range of disease states, improvements to methods for their culture are needed to better facilitate their study.

There are several factors that make Ureaplasma species difficult to culture, especially to high density. They are fastidious by nature, and have the unique requirement of urea for growth, requiring urea-rich media (alongside serum and other special nutrients). Also, their optimal pH for growth is low (between 6.0 and 7.0), with rising pH due to the accumulation of ammonia becoming increasingly toxic as the culture progresses. To monitor this, a pH indicator, such as phenol red, is typically added to the growth media [1]. The rapid die-off Ureaplasma populations at elevated pH requires that broths be monitored for incomplete color change of the pH indicator (< pH ~8.0 for phenol red), at which point cells must either be hastily harvested, or the culture frozen. The combination of these factors makes it difficult to reliably generate the high-titers of Ureaplasma species, at consistent quantities, needed for in vitro and in vivo experimental studies. Though we and other groups have achieved growth of Ureaplasma species to high titers (≥107 colony forming units) [30–34], the process usually requires strict adherence to growth times, close monitoring for alkaline shifts as indicated by the added pH indicator, and often, repeated steps of bacterial cell pelleting via centrifugation followed by resuspension in fresh growth medium. Our goal here was to decrease the labor intensiveness and failure rate of Ureaplasma culture when used to deliver high titers of viable organism. We believe that as the role of Ureaplasma species as pathological agents of various disease states becomes increasingly recognized, the described reactor could serve as a tool for reproducibly generating inocula for both in vitro and in vivo research.

Here, we sought to utilize existing knowledge of Ureaplasma growth dynamics to construct a simple, reproducible bioreactor for stable growth in liquid culture. In 1977, Kenny and Cartwright reported Ureaplasma growth capacity to be correlated with starting urea concentrations of the media. They reported the least amount of urea that supported growth to be 32 μM, with the maximum yield occurring with 32 mM urea [30]. Generation times ranged from 8 hours at 32 μM urea, to 1.6 hours at 3.2 mM urea, where the substrate level was saturating. For cultures with greater than 0.1 mM urea, rapid die-off of the bacterial population proceeded shortly after peak density was achieved. In cultures with urea concentrations of 0.1 mM or lower, population life could be extended, however colony forming unit (CFU) yield was low. Given the toxicity associated with alkalinity, the authors also tested the ability of buffering capacity to increase yields and prolong culture survival. They found that in cultures containing 50 mM urea, and 100 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethane sulfonic acid (MES) buffer increased yield from 6.9 × 106 CFU/mL in unbuffered media to 4.8 × 107 CFU/mL. Importantly, at higher MES concentrations (up to 300 mM), it was found that bacteria survived, but did not grow, making high MES molarity both growth inhibitory and preservative.

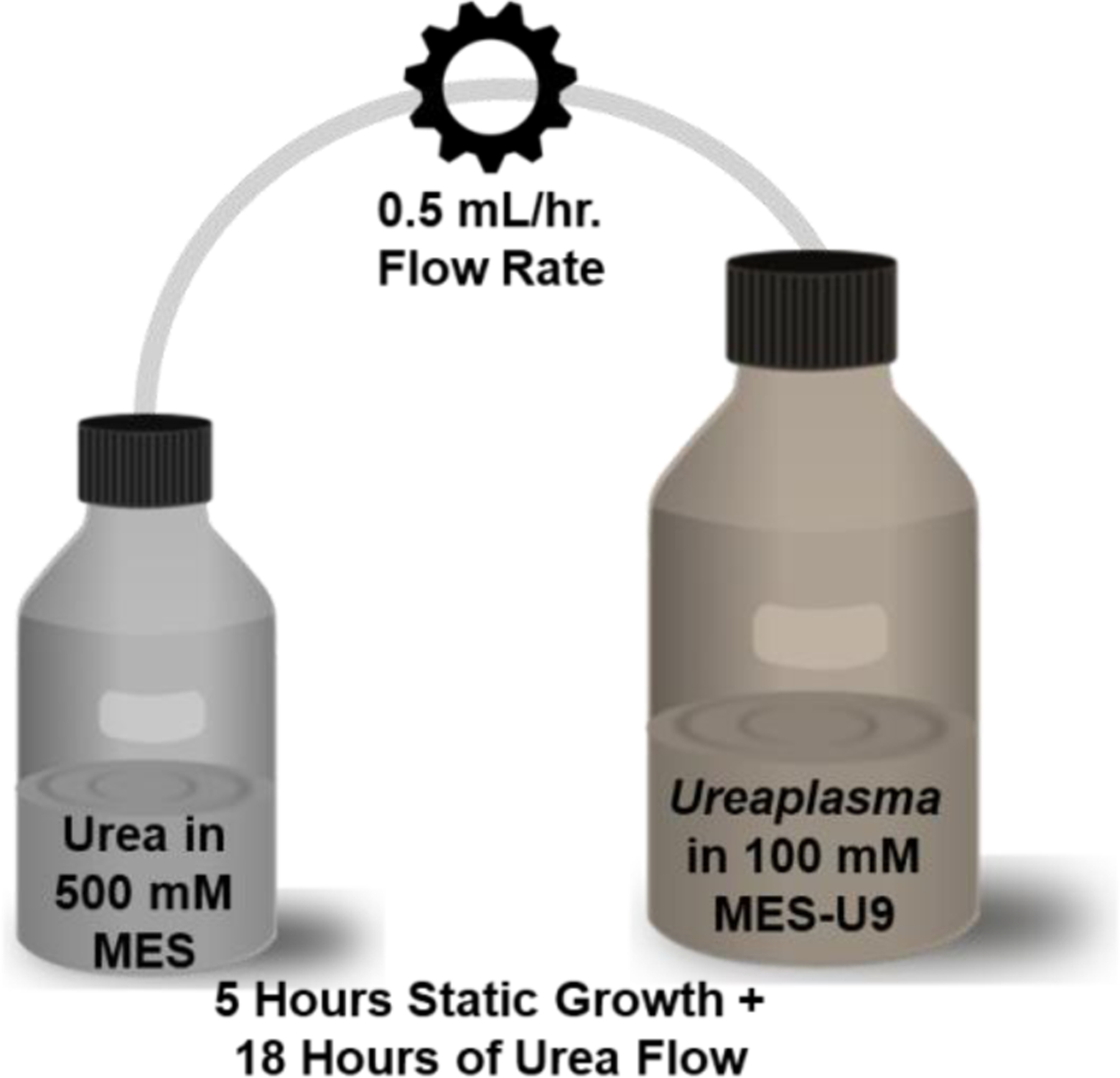

Armed with this knowledge, we designed a Ureaplasma bioreactor (Figure 1) in which an initial 50 mL culture of U. parvum (Mayo Clinic clinical isolate IDRL-10774, multilocus sequence type 22 [35]) in 100 mM MES-buffered U9 broth (U9 [Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA] + MES, free acid [EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA]) containing 8.32 mM urea was grown for 5 hours at 37°C aerobically, without shaking. A peristaltic pump (Masterflex® LS®, Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL) equipped with 0.8 mm ID tubing was then used to add a 500 mM solution of urea in 500 mM MES-Buffered U9-base (no serum, penicillin, L-cysteine HCl, or phenol red) via a continuous rate of 0.5 mL per hour for 18 hours, bringing the end-point MES concentration to the preservative level of 161 mM, and with an average end-point pH of 7.6 (n=3).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the Ureaplasma reactor.

Resulting bacterial counts were determined via the color changing unit (CCU) method [36]. Briefly, the resulting culture was serially diluted, 1:10, in 10B broth (Remel™ R20304), which contains phenol red as a pH indicator. Dilutions in which Ureaplasma cells are present grow to a confluent culture, causing the alkalinity to rise due to ammonia production from urease activity, resulting in a color change from yellow to pink. The CCU dilution factor for at least 3 replicates was then averaged to obtain the final CCU value. It should be noted that as this method is limited to the logarithmic (log10) scale, between 1 and 9 bacterial cells present in the final dilution, result in the same CCU quantification value. However, for this study we aimed to simply show that Ureaplasma species could be grown to large quantities in a stable manner; thus, the CCU method was selected for its simplicity and high throughput nature. Using this method, it was determined that the reactor was capable of growing U. parvum to a density of 4.0 × 107 CCU (Table 1). The peak density culture was preserved by the increased molarity of MES buffer, and the bacterial population was kept stable for at least 4 hours, despite the continuous urea drip and incubation at 37°C.

Table 1. Ureaplasma grown for 23 hours under various conditions.

U. parvum or U. urealyticum were added to 40 mL of either unbuffered or 0.1M MES-buffered U9 and incubated at 37°C for 5 hours before 18 hours of media additions. Medium additions were added continuously at a rate of 0.5 ml/hour, with the exception of a “bolus,” or instantly added, control. N=3. “SD” = Standard deviation. Underlined values are those considered undesirable.

| Organism | Initial medium | Continuous additions starting at 5 hours | 23 hour CCU/mL | CCU/mL SD | 23 hour pH | pH SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOREACTOR | ||||||

| U. parvum | 0.1M MES-buffered U9 | 3% urea in 0.5 MES-buffered U9 base | 4.0 × 107 | 4.24 × 107 | 7.594 | 0.019 |

| U. urealyticum | 0.1M MES-buffered U9 | 3% urea in 0.5 MES-buffered U9 base | 1.0 × 107 | 0 | 7.748 | 0.040 |

| CONTROLS | ||||||

| U. parvum | Unbuffered U9 | Unbuffered U9 base | 3.4 × 103 | 4.67 × 103 | 7.844 | 0.007 |

| U. parvum | Unbuffered U9 | 3% urea in 0.1M MES-buffered U9 base | 1.0 × 101 | 0 | 9.089 | 0.010 |

| U. parvum | 0.1M MES-buffered U9 | 0.1M MES-buffered U9 base | 4.0 × 102 | 4.24 × 102 | 7.326 | 0.019 |

| U. parvum | 0.1M MES-buffered U9 | 3% urea in 0.1 M MES-buffered U9 base | 1.0 × 102 | 0 | 8.561 | 0.029 |

| U. parvum | 0.1M MES-buffered U9 | Bolus 3% urea in 0.5M MES-buffered U9 base | 1.0 × 106 | 0 | 7.118 | 0.003 |

Similar results were seen for U. urealyticum (Mayo Clinic clinical isolate IDRL-10763). Further, while we found these MES and urea concentrations to result in optimal growth while maintaining culture stability, each can be varied to achieve differing bacterial densities. For example, with a starting culture MES concentration of 100 mM and a 291 mM urea drip solution, an average of 106 CCU/mL resulted, with an average end-point pH of 7.0 (n=3). Altering the urea concentration alone resulted in measurable differences in endpoint pH, correlating to varying culture densities (Table 2).

Table 2. Resulting U. parvum cultures with varying concentrations of continuously added urea.

U. parvum cultures were grown from a starting concentration of 105 CCU/mL in 100 mM MES buffered-U9 media for 23 hours with varying concentrations of urea continuously added in a 500 mM MES-buffered-U9 base drip solution at 0.5 mL/hour for the last 18 hours.

| Continuously added urea concentration | 23 hour CCU/mL | 23 hour pH |

|---|---|---|

| 500 mM | 107 | 7.6 |

| 417 mM | 106 | 7.3 |

| 333 mM | 106 | 7.1 |

| 250 mM | 106 | 6.9 |

By growing Ureaplasma species in this manner, it is possible to consistently achieve high density cultures without rapid population loss at a critical pH or upon depletion of urea. If even higher numbers of Ureaplasma cells are needed, an additional step of 1:10 or 1:100 concentration via centrifugation at 15,000 × G for 30 minutes, followed by resuspension in 100 mM MES buffered-U9 (to extend the life of the concentrated culture) is possible. Resulting concentrated cultures can be grown for additional times after resuspension in fresh 100 mM MES buffered-U9. Additionally, concentrated cultures can be immediately frozen at −80°C and stored for upwards of 6–10 years [37], without the inclusion of glycerol or other cryoprotectants, as the broth serum component itself is protective.

In conclusion, this simple and inexpensive bioreactor design will allow Ureaplasma researchers a reliable way to grow high-titer cultures, reducing experimental variability, and alleviating the labor intensiveness normally associated with cultivation of the organism.

Highlights:

High-titer cultures of Ureaplasma species are unstable and can be challenging to grow.

A bioreactor was designed for reliable, stable growth of Ureaplasma species.

The bioreactor utilizes continuous addition of urea in high-molarity buffer.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R21AI150649.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interests: Dr. Patel reports grants from Merck, ContraFect, TenNor Therapeutics Limited and Shionogi. Dr. Patel is a consultant to Curetis, Specific Technologies, Next Gen Diagnostics, PathoQuest, Selux Diagnostics, 1928 Diagnostics, PhAST, and Qvella; monies are paid to Mayo Clinic. Dr. Patel is also a consultant to Netflix. In addition, Dr. Patel has a patent on Bordetella pertussis/parapertussis PCR issued, a patent on a device/method for sonication with royalties paid by Samsung to Mayo Clinic, and a patent on an anti-biofilm substance issued. Dr. Patel receives an editor’s stipend from IDSA, and honoraria from the NBME, Up-to-Date and the Infectious Diseases Board Review Course.

References

- 1.Dando SJ, Sweeney, Knox Emma L., Christine L, Ureaplasma, in Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria. 2019. p. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Povlsen K, et al. , Relationship of Ureaplasma urealyticum biovar 2 to nongonococcal urethritis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2002. 21(2): p. 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang N, et al. , Are Ureaplasma spp. a cause of nongonococcal urethritis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 2014. 9(12): p. e113771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romero R and Garite TJ, Twenty percent of very preterm neonates (23–32 weeks of gestation) are born with bacteremia caused by genital mycoplasmas. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2008. 198(1): p. 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldenberg RL, et al. , The Alabama Preterm Birth Study: umbilical cord blood Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis cultures in very preterm newborn infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2008. 198(1): p. 43.e1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Resch B, et al. , Neonatal Ureaplasma urealyticum colonization increases pulmonary and cerebral morbidity despite treatment with macrolide antibiotics. Infection, 2016. 44(3): p. 323–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waites KB, et al. , Congenital and opportunistic infections: Ureaplasma species and Mycoplasma hominis. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med, 2009. 14(4): p. 190–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gassiep I, et al. , Ureaplasma urealyticum necrotizing soft tissue infection. J Infect Chemother, 2017. 23(12): p. 830–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walkty A, et al. , Ureaplasma parvum as a cause of sternal wound infection. J Clin Microbiol, 2009. 47(6): p. 1976–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korytny A, et al. , Ureaplasma parvum causing life-threatening disease in a susceptible patient. BMJ Case Rep, 2017. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez R, et al. , Ureaplasma Transmitted From Donor Lungs Is Pathogenic After Lung Transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg, 2017. 103(2): p. 670–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bharat A, et al. , Disseminated Ureaplasma infection as a cause of fatal hyperammonemia in humans. Sci Transl Med, 2015. 7(284): p. 284re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nowbakht C, et al. , Two cases of fatal hyperammonemia syndrome due to Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in Immunocompromised patients outside lung transplant recipients. Open forum infectious diseases, 2019. 6(3): p. ofz033–ofz033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krutsinger D, et al. , Idiopathic hyperammonemia after solid organ transplantation: Primarily a lung problem? A single-center experience and systematic review. Clin Transplant, 2017. 31(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiberenge RK and Lam H, Fatal hyperammonemia after repeat renal transplantation. J Clin Anesth, 2015. 27(2): p. 164–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beeton ML, Possible missed diagnosis of Ureaplasma spp infection in a case of fatal hyperammonemia after repeat renal transplantation. J Clin Anesth, 2016. 33: p. 504–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navaneethan U and Venkatesh PG, Idiopathic hyperammonemia in a patient with total pancreatectomy and islet cell transplantation. JOP, 2010. 11(6): p. 620–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espinos J, et al. , Idiopathic hyperammonemia following high-dose chemotherapy. Bone Marrow Transplant, 2006. 37(9): p. 899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell RB, et al. , Syndrome of idiopathic hyperammonemia after high-dose chemotherapy: review of nine cases. Am J Med, 1988. 85(5): p. 662–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies SM, et al. , Idiopathic hyperammonemia: A frequently lethal complication of bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant, 1996. 17(6): p. 1119–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharp RA and Lang CC, Hyperammonaemic encephalopathy in chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Lancet, 1987. 1(8536): p. 805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson AJ, et al. , Transient idiopathic hyperammonaemia in adults. Lancet, 1985. 2(8467): p. 1271–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho AY, et al. , Idiopathic hyperammonaemia syndrome following allogeneic peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation (allo-PBPCT). Bone marrow transplant, 1997. 20(11): p. 1007–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frere P, et al. , Hyperammonemia after high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant, 2000. 26(3): p. 343–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tse N, Cederbaum S, and Glaspy JA, Hyperammonemia following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Am J Hematol, 1991. 38(2): p. 140–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uygun V, et al. , Idiopathic hyperammonemia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A case report. Pediatr Transplant, 2015. 19(4): p. E104–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snyder MJ, et al. , Idiopathic hyperammonemia following an unrelated cord blood transplant for mucopolysaccharidosis I. Pediatr Dev Pathol, 2003. 6(1): p. 78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe R, et al. , Idiopathic hyperammonemia following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for refractory lymphoma. Jap J Clin Hematol, 2000. 41(12): p. 1285–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Placone N, et al. , Hyperammonemia From Ureaplasma Infection in an Immunocompromised Child. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenny GE and Cartwright FD, Effect of urea concentration on growth of Ureaplasma urealyticum (T-strain Mycoplasma). J Bacteriol, 1977. 132(1): p. 144–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glaser K, et al. , Ureaplasma isolates stimulate pro-inflammatory CC chemokines and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in neonatal and adult monocytes. PloS one, 2018. 13(3): p. e0194514–e0194514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kotani H and McGarrity GJ, Ureaplasma infection of cell cultures. Infection and immunity, 1986. 52(2): p. 437–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, et al. , Ureaplasma urealyticum causes hyperammonemia in an experimental immunocompromised murine model. PLoS One, 2016. 11(8): p. e0161214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, et al. , Ureaplasma parvum causes hyperammonemia in a pharmacologically immunocompromised murine model. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2017. 36(3): p. 517–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernández J, et al. , Antimicrobial susceptibility and clonality of clinical Ureaplasma isolates in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2016. 60(8): p. 4793–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purcell RH, et al. , Color test for the measurement of antibody to T-strain Mycoplasmas. Journal of bacteriology, 1966. 92(1): p. 6–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furr PM and Taylor-Robinson D, Long-term viability of stored mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas. J Med Microbiol, 1990. 31(3): p. 203–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]