Abstract

The ventral part of the anteromedial thalamic nucleus (AMv) is in a position to convey information to the cortico-hippocampal-amygdalar circuit involved in the processing of fear memory. Corticotropin-releasing-factor (CRF) neurons are closely associated with the regulation of stress and fear. However, few studies have focused on the role of thalamic CRF neurons in fear memory. In the present study, using a conditioned fear paradigm in CRF transgenic mice, we found that the c-Fos protein in the AMv CRF neurons was significantly increased after cued fear expression. Chemogenetic activation of AMv CRF neurons enhanced cued fear expression, whereas inhibition had the opposite effect on the cued fear response. Moreover, chemogenetic manipulation of AMv CRF neurons did not affect fear acquisition or contextual fear expression. In addition, anterograde tracing of projections revealed that AMv CRF neurons project to wide areas of the cerebral cortex and the limbic system. These results uncover a critical role of AMv CRF neurons in the regulation of conditioned fear memory.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12264-020-00592-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Corticotropin-releasing-factor neurons, Ventral anteromedial thalamic nucleus, Cued fear expression, Chemogenetics

Introduction

The ventral part of the anteromedial thalamic nucleus (AMv) is the ventral portion of the medial part of the anterior thalamic nuclei. The anterior thalamic nuclei are known to be involved in spatial learning and navigational memory, as well as emotional memory processing related to predatory threats [1–5]. Anatomically, the anterior thalamic nuclei are in a position to convey information to the cortico-hippocampal-amygdalar circuit, which plays a critical role in the regulation of fear-related behavior in animals [6]. Previous studies have also shown that the anterior thalamic nuclei are correlated with fear-conditioned memory. Lesions of the anterior thalamic nuclei were found to strongly impair the stabilization of contextual fear memory in rats [7], and c-Fos immunoreactivity was found to be significantly increased in the anterodorsal thalamic nuclei of rats exposed to both the context and the auditory-based conditioned stimulus (CS) associated with a previous foot shock [8].

In terms of the anteromedial thalamus (AM) and its ventral part (AMv), previous studies have shown that cytotoxic lesions of the AM considerably impair the contextual fear responses to an environment previously associated with a predator [4, 5]. In addition, cytotoxic lesions in the AMv have been shown to significantly impair the acquisition of contextual fear memory in rats [9].

In mammals, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF, also referred to as corticotropin-releasing hormone-CRH) is most often associated with the regulation of fear and anxiety [10–12]. CRF neurons, especially hypothalamic CRF neurons, are considered to be responsible for launching the endocrine component of the mammalian stress response [13, 14]. There are also indications that CRF neurons may regulate complex behaviors [15, 16]. In recent years, many reports have uncovered plausible pathways through which CRF neurons distributed in specific brain regions may regulate rapid behaviors after stress, including fear responses [12]. The contribution of CRF neurons in amygdala nuclei to the acquisition or expression of conditioned fear has been extensively studied [17]. However, little is known about the participation of CRF neurons in other regions of the brain, especially in the anterior thalamus, in regulation of conditioned fear memory.

In the present study, using a classical fear conditioning paradigm [18], we analyzed the pattern of c-Fos expression, as well as the co-expression of CRF and c-Fos, in the AMv after exposure to the auditory-based CS associated with a previous foot shock. Furthermore, we bidirectionally activated/inhibited AMv CRF neurons via designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD) prior to either training (to test for the acquisition of cued fear memory) or cued testing (to test for the expression of cued fear memory) and analyzed freezing responses during exposure to the foot shock-associated auditory or olfactory CS. Finally, we examined the projection patterns of AMv CRF neurons using the AAV-DIO-EYFP anterograde tracer, which delineated the possible neural pathways involved in the regulation of cued fear memory.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male Crh-IRES-Cre [19, 20] and Crh-IRES-Cre;Ai14 [17, 21] mice (8–12 weeks old) weighing ~25 g each were used. The Crh-IRES-Cre mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory, and the Ai14 mice were obtained from the laboratory of Minmin Luo (National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing). All of the mice were bred onto the C57BL/6N genetic background for at least five generations. The Crh-IRES-Cre;Ai14 mice were derived from crosses of the Crh-IRES-Cre and Ai14 genotypes and used to detect the expression of c-Fos protein in CRF neurons. The Crh-IRES-Cre mice were used to investigate the role of CRF neurons in fear expression and trace the anterograde projection. Mice were housed in groups under controlled temperature (23°C) and illumination (12-h light/dark cycle, light from 08:00 to 20:00) and were provided free access to water and food. The behavioral tests were performed between 09:30 and 17:30. Each mouse was handled for five consecutive days (5 min per day) prior to behavioral testing.

Ethics

All of the experiments were carried out in accordance with international guidelines and protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Science and Technology of China. We made all efforts to minimize the number of animals used as well as their suffering.

Surgery

Mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (Merck, 80 mg/kg, [i.p.]) and positioned in a stereotaxic frame. A longitudinal incision was made to expose the skull, and a window was opened, exposing the dura mater and sagittal sinus. For mice that received AAV-EF1α-DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry (8.57 × 1012 genome copies per mL, OBiO), AAV-EF1α-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry (5.40 × 1012 genome copies per mL, BrainVTA), AAV-EF1α-DIO-mCherry (5.05 × 1012 genome copies per mL, BrainVTA), or anterograde-tracer AAV-EF1α-DIO-EYFP (5.30 × 1012 genome copies per mL, BrainVTA) deposits, 150 nL of viral vectors was delivered bilaterally or unilaterally into the AMv (coordinates: anterior/posterior to bregma, −0.82 mm; medial/lateral, +/−1.15 mm; dorsal/ventral, −3.69 mm; 10° angle) of the Crh-IRES-Cre mice via a microsyringe (Hamilton) attached to an automatic pump controller (Micro4, WPI). The needle was left in the brain for 5 min before being withdrawn slowly to allow for viral diffusion. After the surgery, all of the mice were allowed to recover for 4 weeks before further experiments.

Fear Conditioning Paradigm

The Crh-IRES-Cre and Crh-IRES-Cre;Ai14 mice were used in the fear conditioning experiments. Two different environmental contexts were used for behavioral experiments. In context A, the mice were placed in a rectangular chamber (25 × 30 × 18 cm3) with a transparent plastic top and walls. The floor was made of 19 stainless steel rods (6-mm diameter with 1.2-cm spacing) connected to a shock delivery apparatus (Grid Floor Shocker, AniLab Software & Instruments Co., Ltd, Ningbo, China). A loudspeaker/gas tube was connected to a stimulus-programming device to emit acoustic/olfactory stimuli (AniLab version 6.50, AniLab Software & Instruments, China). The chamber was placed in an acoustically-insulated room and kept at a constant temperature of 22°C ± 1°C, and the illumination inside the room was 60 lux (lx). Context B was an acrylic triangular chamber (37 × 32 × 28 cm3) with white walls and a flat white floor covered with a transparent acrylic lid. The triangular chamber was located in a different soundproof room from the context in which the training was performed. The illumination inside the room was set at 30 lx. Each chamber contained a small hole that was set on the wall 3 cm beneath the lid to deliver the auditory or olfactory stimuli.

On day 1, mice were gently removed from their home cages and placed in context A. After habituation for 120 s, a pure tone (6 kHz, 75 dB) (Figs. 2C, 3B, S2B, and S4A) or amyl acetate odor diluted in water (5%, 2 L/min) (Fig. 4B) lasting for 30 s was delivered five times at 60-s intervals. Each mouse was brought back to its home cage 60 s after the last delivery of the tone or odor. On day 2, after a 120-s baseline period, mice were conditioned five times by pairing the 30-s CS (auditory or olfactory stimulus) with the unconditional stimulus (US) (electric foot shock, 0.7 mA, 3 s) (Figs. 2C, 3B, 4B, S2B, and S4A). The paired CS-US was delivered five times at 60-s intervals. Each mouse was placed back in its home cage 60 s after the last CS-US pairing. On day 3, mice were tested for contextual fear expression or cued fear expression. For the contextual fear expression test (Fig. S2B), mice were placed back in context A for 300 s without auditory or olfactory stimuli. For the cued fear expression test (Figs. 2C, 3B, 4B, and S4A), mice were placed in context B and, after a 120-s habituation period, presented with the 30-s CS five times with a 60-s inter-trial interval. Freezing behavior (no movement for 1 s) during the CS period (for day 2 training and day 3 cued fear expression) or the 300-s period (for day 3 contextual fear expression) was recorded and automatically scored via the versatile software LabState (AniLab). For the chemogenetic manipulation experiments, clozapine N-oxide (CNO, Sigma, C0832, 5 mg/kg, [i.p.]) was administered 30 min before each behavioral test. For evaluation of the possible non-specific or off-target effects of CNO injection on behavior, saline or CNO (5 mg/kg, [i.p.]) was administered 30 min before the cued expression test.

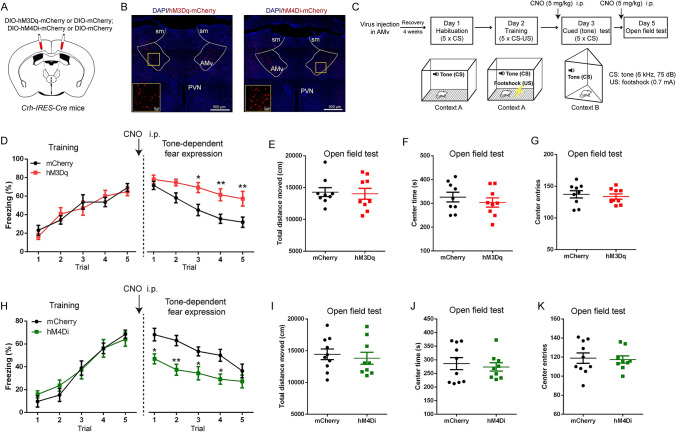

Fig. 2.

Chemogenetic manipulation of CRF neurons in the AMv during the cued test affects auditory-cued fear expression. A Schematic of hM3Dq, mCherry, or hM4Di virus injection in the AMv of Crh-IRES-Cre mice. B Representative images of hM3Dq (left) and hM4Di (right) injection in the AMv region; scale bars, 500 μm. The yellow boxes depict the areas shown in the boxes on the AMv; scale bars, 50 μm. C Behavioral paradigm for chemogenetic activation or inhibition of AMv CRF neurons. D Freezing responses across trials in the fear training session (F4,64 = 1.065, P = 0.381; main effect of genotype, F1,16 = 0.033, P = 0.858) and the cued-expression session (F4,64 = 2.263, P = 0.072; main effect of genotype, F1,16 = 10.370, P = 0.005) for mCherry and hM3Dq groups. E–G Total distance traveled (E), time in the central zone (F), and entries into the central zone (G) during the open field test (distance: t16 = 0.236, P = 0.816; time: t16 = 0.800, P = 0.436; entries: t16 = 0.493, P = 0.629) for the mCherry and hM3Dq groups. H Freezing responses across trials in the fear training session (F4,68 = 0.705, P = 0.592; main effect of genotype, F1,17 = 0.093, P = 0.765) and the cued-expression session (F4,68 = 1.785, P = 0.142; main effect of genotype, F1,17 = 10.600, P = 0.005) for the mCherry and hM4Di groups. I–K Total distance traveled (I), time in the central zone (J), and entries into the central zone (K) during the open field test (distance: t17 = 0.486, P = 0.633; time: t17 = 0.450, P = 0.659; entries: t17 = 0.216, P = 0.832) for the mCherry and hM4Di groups. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. For D and H, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 in Sidak’s post hoc analysis compared with the mCherry control; for E–G and I–K, unpaired t-test. In D–G, n = 9 for mCherry; 9 for hM3Dq. In H–K, n = 10 for mCherry; 9 for hM4Di.

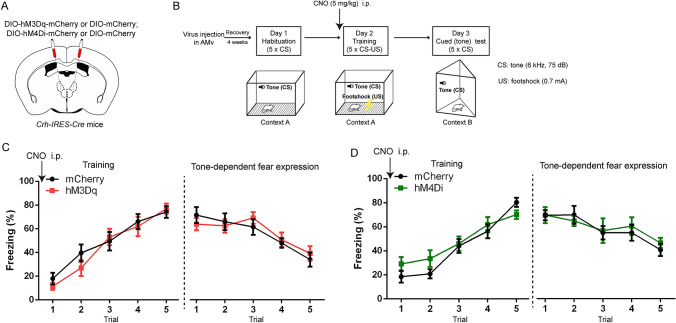

Fig. 3.

Chemogenetic manipulation of AMV CRF neurons during training does not affect conditioned fear acquisition and the following cued fear expression. A Schematic of hM3Dq, hM4Di, or mCherry virus injection in the AMv of Crh-IRES-Cre mice. B Behavioral paradigm for chemogenetic activation or inhibition of AMv CRF neurons. Mice received CNO (5 mg/kg, [i.p.]) 30 min prior to the fear training test. C Freezing responses across trials in the fear training session (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, genotype × trial interaction, F4,56 = 0.705, P = 0.592; main effect of genotype, F1,14 = 0.432, P = 0.522) and the cued-expression session (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, genotype × trial interaction, F4,56 = 0.717, P = 0.584; main effect of genotype, F1,14 = 0.033, P = 0.859) for the mCherry and hM3Dq groups. D Freezing responses across trials in the fear training session (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, genotype × trial interaction, F4,56 = 1.387, P = 0.250; main effect of genotype, F1,14 = 1.503, P = 0.241) and the cued-expression session (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, genotype × trial interaction, F4,56 = 0.429, P = 0.787; main effect of genotype, F1,14 = 0.056, P = 0.816) for the mCherry and hM4Di groups. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. In C, n = 8 for mCherry; 8 for hM3Dq; in D, n = 8 for mCherry; 8 for hM4Di.

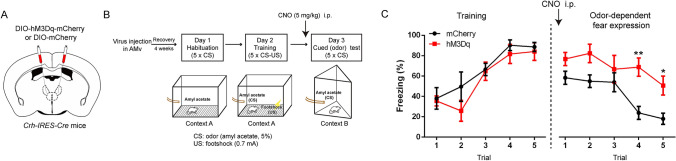

Fig. 4.

Chemogenetic activation of AMv CRF neurons during the cued test increases odor-cued fear expression. A Schematic of hM3Dq or mCherry virus injection in the AMv of Crh-IRES-Cre mice. B Behavioral paradigm for chemogenetic activation of AMv CRF neurons. Mice received CNO (5 mg/kg, [i.p.]) 30 min prior to the cued fear expression test. C Freezing responses across trials in the fear training session (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, genotype × trial interaction, F4,32 = 0.681, P = 0.610; main effect of genotype, F1,8 = 1.161, P = 0.313) and the cued (odor)-expression session (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, genotype × trial interaction, F4,32 = 1.480, P = 0.231; main effect of genotype, F1,8 = 12.71, P = 0.007). Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 in Sidak’s post hoc analysis compared with the mCherry control, n = 5 for hM3Dq; 5 for mCherry.

In the c-Fos immunostaining experiment (Fig. 1A), the control and cued fear expression groups were placed in context A and subjected to the same habituation (tone presentation) on day 1 and training (tone–foot shock pairing) on day 2 as described above. On day 3 (cued expression test), the cued fear expression group was placed in context B and presented with a 30-s tone five times with a 60-s inter-trial interval, while the control group was placed in context B without tone presentation (Fig. 1A). The freezing behaviors of the control and cued fear expression groups during the tone presentation on day 2 (training) were recorded (Fig. 1B, left). On day 3 (cued expression test), for the cued fear expression group, the freezing behaviors during the tone presentation were scored; for the control group, the freezing behaviors were scored during the same period as that in the cued fear expression group (Fig. 1B, right). The cued fear expression and control groups were placed back in their home cages for 90 min after the day 3 cued expression test, and then sacrificed (Fig. 1A).

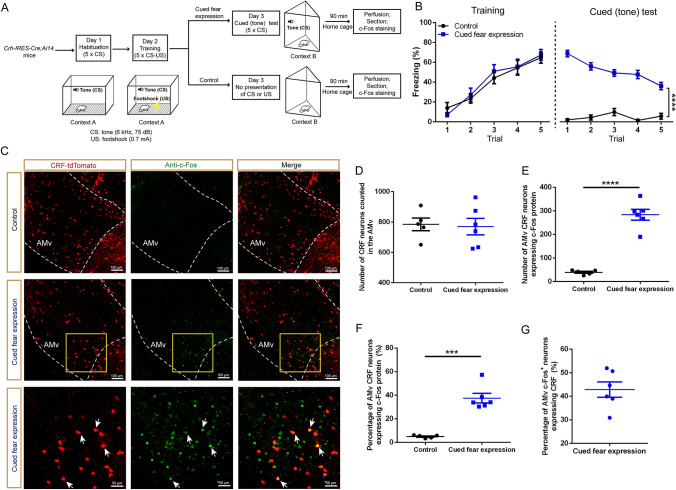

Fig. 1.

C-Fos immunoreactivity is increased in AMv CRF neurons after cued fear expression. A Schematic of the conditioned fear behavioral experiment and c-Fos staining. B Freezing responses across trials in the fear training session (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, group × trial interaction, F4,36 = 0.452, P = 0.770; main effect of group, F1,9 = 0.089, P = 0.773) and the cued (tone) test (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, group × trial interaction, F4,36 = 10.000, P < 0.0001; main effect of group, F1,9 = 368.8, P < 0.0001) for the control and cued fear expression groups. C Representative images showing CRF neurons (red), c-Fos-immunoreactive neurons (green), and dual-labeled neurons (merged) in the unilateral AMv of the control group (top) and cued fear expression group (middle); scale bars, 100 μm. Lower panels: magnifications of the yellow boxes in the middle panels; scale bars, 50 μm. Arrowheads indicate double-labeled neurons. D Total number of CRF neurons in the AMv for control and cued fear expression groups (unpaired t-test, t9 = 0.205, P = 0.842). E Quantification of AMv CRF neurons expressing c-Fos protein in bilateral AMv regions of the two groups (unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, t5.337 = 10.44, P < 0.0001). F Percentages of AMv CRF neurons expressing c-Fos protein in the control and cued fear expression groups (unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, t5.177 = 7.872, P < 0.001). G Percentage of AMv c-Fos-positive neurons expressing CRF in the cued fear expression group. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM, n = 5 for control; 6 for cued fear expression. ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Basal Freezing Behavioral Test

Crh-IRES-Cre mice were injected with hM3Dq or mCherry virus in the bilateral AMv. After recovery for 4 weeks, mice were directly placed in an acrylic rectangular box (28 × 18 × 15 cm3) and allowed to explore freely for 10 min (Fig. S3B). CNO (5 mg/kg, [i.p.]) was administered 30 min before the test. Locomotor activity was recorded by a video camera. The freezing behavior (no movement for 1 s) during a 10-min epoch was recorded and automatically scored using LabState software.

Open Field Test

The locomotor activity of the mice was recorded in an open-field arena (50 × 50 × 50 cm3). The center zone was defined as a 25 × 25 cm2 area centered in the arena. Mice were injected with CNO (5 mg/kg, [i.p.]) 30 min before the test (Fig. 2C). The total distance traveled, center time, and center entries in the 30-min test for each mouse were recorded and analyzed using EthoVision XT 8.5 software (Noldus, Netherlands).

Histology

Mice were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (80 mg/kg, [i.p.]) and transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% ice-cold paraformaldehyde (PFA) dissolved in 0.1 mol/L PBS (pH: 7.4). Brains were removed and post-fixed in 0.1 mol/L PBS containing 4% PFA overnight at 4°C. Brains were then transferred to 15% sucrose for 24 h followed by 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C for 2–3 days. Brain tissues were frozen and cut into serial sections (40-μm or 50-μm thick) on a microtome (Leica CM1950, Germany). The sections were stored at −20°C until use in further experiments.

During the c-Fos immunostaining experiment (Fig. 1C), in order to target the AMv region accurately, four sections (40-μm thick per section) at 40-μm intervals were used. Sections were rinsed in PBS and treated with PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 for 30 min. Subsequently, the floating sections were washed in PBS and then subjected to the following: (a) incubation in 5% normal donkey serum (prepared with PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100) at 37°C for 30 min to block nonspecific staining; (b) incubation with the primary antibody, anti c-Fos (rabbit, 1:1000; SC-52, Santa Cruz) at room temperature for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C; (c) washing in PBS; (d) incubation with secondary antibody (donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, 1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch) in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 for 2 h at room temperature; (e) washing in PBS; and (f) mounting on gelatin-coated slides and storage at −20°C. Another series of adjacent sections was stained with thionin to demarcate neuroanatomical structures. Sections were imaged using an LSM 880 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Germany). The borders of the AMv region, defined in adjoining Nissl-stained sections, were delineated in the given sections according to the brain atlas [22]. Quantification of tdTomato-positive CRF neurons and c-Fos-positive neurons was performed using ImageJ software (NIH) and obtained by an observer without knowledge of the experimental status of each mouse. Only labeled nuclei that fell within the borders of a region of interest were counted. Cell counting was performed on both sides of the AMv.

In order to present the DREADD-targeting AMv region (Fig. 2B) or anterograde axonal tracing (Fig. 5), sections (40-μm thick for DREADD-targeting and 50-μm thick for tracing) were used. Given the thicker sections in the anterograde axonal-tracing experiment, the sparse projection from the AMv CRF neurons could be traced more clearly. Sections were washed three times (10 min each time) in PBS and then incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI; Thermo Fisher Scientific, D1306) diluted 1:1,000 in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature. Sections were washed three times (10 min each time) in PBS and then mounted on gelatin-coated slides. Sections were imaged under an LSM 880 confocal microscope. The presence of virus-infected CRF neurons in the AMv and the analysis of EYFP-positive fibers were performed according to the brain atlas as described above. The EYFP-positive fibers were classified as sparse (+), moderate (++), or dense (+++), as described previously [23]. The relative intensity of the efferent projections presented in Table S1 was determined in coronal sections from three Crh-IRES-Cre mice. The degree of projection intensity in each brain region was assessed by the same observer.

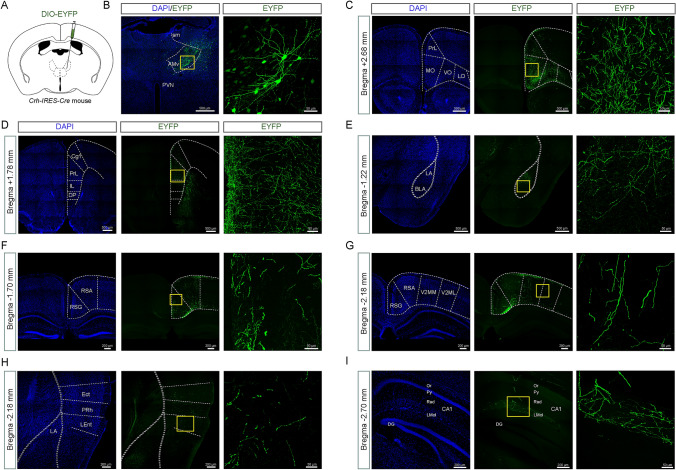

Fig. 5.

AMv CRF neurons project to wide areas of the cerebral cortex and limbic system. A Schematic of AAV-DIO-EYFP injection into the unilateral AMv region of the Crh-IRES-Cre mouse. B Left: representative image of the AAV-DIO-EYFP injection into the AMv region. Right: enlarged view of EYFP-labeled CRF neurons in the AMv indicated by the box in the left image. C–I Representative images of DAPI staining (left) and ipsilateral EYFP positive fibers (middle) in the MO (C), PrL (D), BLA (E), RSG (F), V2 (G), Ect (H), PRh (H), LEnt (H), and CA1 (I). Right: enlarged views of EYFP-labeled CRF fibers indicated by the boxes in the middle panels. The scale bars are shown in each image. AMv, anteromedial thalamic nucleus, ventral part; BLA, basolateral amygdaloid nucleus, anterior part; CA1, CA1 of the hippocampus; Cg1, cingulate cortex, area 1; DG, dentate gyrus; DP, dorsal peduncular cortex; Ect, ectorhinal cortex; IL, infralimbic cortex; LA, lateral amygdaloid nucleus; LEnt, lateral entorhinal cortex; LMol, lacunosum molecular layer of the hippocampus; LO, lateral orbital cortex; MO, medial orbital cortex; Or, oriens layer of the hippocampus; PrL, prelimbic cortex; VO, ventral orbital cortex; PRh, perirhinal cortex; PVN, paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus; Py, pyramidal cell layer of the hippocampus; Rad, stratum radiatum of the hippocampus; RSA, retrosplenial agranular cortex; RSG, retrosplenial granular cortex; sm, stria medullaris of the thalamus; V2ML, secondary visual cortex, mediolateral area; V2MM, secondary visual cortex, mediomedial area.

For blue-fluorescent Nissl staining (Fig. S1), four sections (40-μm thick) at 40-μm intervals containing the AMv region were rinsed three times (10 min each time) in PBS and incubated with blue-fluorescent Nissl stain (NeuroTrace 435/455 Nissl stain, Thermo Fisher Scientific, N12479) diluted 1:50 in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature. After washing three times (10 min each time) in PBS, the sections were mounted on gelatin-coated sides and imaged under an LSM 880 confocal microscope. TdTomato-positive CRF neurons and NeuroTrace-positive neurons were quantified using ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

The SPSS 21.0 software package (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) or GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad, USA) was used for statistical analysis. After testing for homogeneity of variance, comparisons between two groups were analyzed using unpaired t-tests or unpaired t-tests with Welch’s correction. Comparisons among multiple groups were analyzed using two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak’s post hoc analyses. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM and significance levels are indicated as *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

Results

Increased c-Fos Immunoreactivity in AMv CRF Neurons After Cued Fear Expression

To investigate the activity of AMv CRF neurons in fear expression, we subjected Crh-IRES-Cre;Ai14 mice to the classical fear conditioning test (pairing a pure tone with a foot shock). The control and cued fear expression mice were subjected to the same habituation on day 1 and training on day 2 (Fig. 1A). On day 3 of the cued test, the cued fear expression mice were exposed to the CS (tone) five times, while there was no presentation of CS or US to the control mice (Fig. 1A). During training, both the control and fear expression groups successfully acquired cued fear. There were no significant differences in the freezing responses across the CS presentation between the two groups (Fig. 1B, left). In the cued (tone) test, the fear expression group displayed a significant increase in fear responses across the five trials (Fig. 1B, right). At 90 min after the cued fear expression, there was a higher degree of c-Fos protein expression as well as increased co-expression of CRF- and c-Fos-positive neurons in the AMv of the fear expression group compared to the control group (Fig. 1C). The total number of CRF neurons in the bilateral AMv did not differ between the control and cued fear expression groups (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, the number of CRF neurons expressing c-Fos and the ratio of CRF/c-Fos co-expressing neurons to total CRF neurons in the bilateral AMv of the cued fear expression group were significantly higher than those in the control mice (Fig. 1E, F). Further analysis revealed that, in the AMv, only ~14% of neurons expressed CRF (Fig. S1). Notably, ~43% of the c-Fos-positive neurons expressed CRF in the bilateral AMv in the cued fear expression mice (Fig. 1G). These results indicate that the activity of CRF neurons in the AMv is increased during cued fear expression.

Chemogenetic Activation/Inhibition of CRF Neurons in the AMv During the Cued Test Affects Auditory-Cued Fear Expression

To test whether activation of AMv CRF neurons influences the cued fear expression of mice, we virally injected Cre-dependent excitatory DREADD DIO-hM3Dq into the bilateral AMv of Crh-IRES-Cre mice (Fig. 2A, B). The control Crh-IRES-Cre mice were injected with DIO-mCherry. Four weeks after the surgery, behavioral experiments were performed. Mice were habituated and trained in a cued (tone) fear condition paradigm. At 24 h after training, mice were tested in a novel context for freezing responses to the CS (tone). CNO (5 mg/kg, diluted with saline) was injected 30 min prior to the cued test (Fig. 2C). During training (day 2), in the absence of CNO, there were no significant differences in the fear responses during CS (tone) presentation between mice expressing hM3Dq and mCherry (Fig. 2D, left). Notably, both the mCherry and hM3Dq groups successfully acquired cued fear. During the cued test (day 3), in the presence of CNO, mice expressing hM3Dq displayed significantly more freezing behaviors in response to the CS (tone) than mice expressing mCherry (Fig. 2D, right). To assess the role of CRF neurons in contextual fear expression, we habituated and conditioned mice as described above and only administered CNO (5 mg/kg) prior to the contextual test (Figs. S2A, B). Activation of AMv CRF neurons with CNO did not alter the expression of contextual fear, as the freezing responses of hM3Dq and mCherry mice were indistinguishable (Figs. S2C–E).

To determine whether the promotion of freezing induced by activation was due to an increase of the unconditioned fear response, we injected DIO-hM3Dq into the bilateral AMv of Crh-IRES-Cre mice and investigated the basal freezing behavior in a small chamber similar to the foot shock context. CNO (5 mg/kg) was injected prior to the test (Figs. S3A, B). The results demonstrated that activation of AMv CRF neurons did not cause any significant alteration in the freezing response during the 10-min test (Figs. S3C, D). To determine whether the promotion of freezing was due to a general effect on an anxiety-like response, we injected CNO (5 mg/kg) into the hM3Dq and mCherry mice and subjected both groups to the 30-min open field test (Fig. 2C). The results revealed no significant differences in the total distance traveled, center time, or center entries between the mCherry and hM3Dq groups (Fig. 2E–G), suggesting that activation of AMv CRF neurons had no effect on locomotor activity or anxiety. Collectively, these data suggest that AMv CRF neurons are specialized for cued fear expression.

To test whether inhibition of AMv CRF neurons alters cued fear expression, we virally injected Cre-dependent inhibitory DREADD DIO-hM4Di into the bilateral AMv of Crh-IRES-Cre mice (Fig. 2A, B) and subjected the mice to the same experimental paradigm as the hM3Dq mice (Fig. 2C). During training (day 2), in the absence of CNO, there were no significant differences in the fear responses during CS (tone) presentation between mice expressing hM4Di and those expressing mCherry (Fig. 2H, left). Notably, both groups successfully acquired cued fear. During the cued test (day 3), in the presence of CNO, mice expressing hM4Di displayed significantly fewer freezing behaviors in response to the CS (tone) compared with mice expressing mCherry (Fig. 2H, right). In the open field test, there were no significant differences in the total distance traveled, center time, or center entries between the hM4Di and mCherry groups (Fig. 2I–K), suggesting that inhibition of AMv CRF neurons had no effect on the locomotor activity or anxiety. Furthermore, as a control, Crh-IRES-Cre mice that were not transfected with virus, were injected with CNO (5 mg/kg) or saline and subjected the mice to the fear conditioning test (Fig. S4A). The results showed that systemic CNO delivery during the cued test had no significant effect on cued fear expression (Fig. S4B), demonstrating that the effects of the chemogenetic manipulation of AMv CRF neurons were not due to non-specific behavioral effects of CNO. Collectively, these results demonstrate that CNO-induced hM4Di inhibition of AMv CRF neurons during the cued test induces lower levels of fear expression.

Chemogenetic Activation/Inhibition of AMv CRF Neurons During Training Does Not Affect Cued Fear Acquisition

The above findings suggest that AMv CRF neurons regulate the expression of cued fear, but it remained unknown as to whether AMv CRF neurons also influence the initial acquisition of cued fear. We injected DIO-hM3Dq virus into the bilateral AMv of Crh-IRES-Cre mice. Control mice were injected with mCherry virus in their AMv (Fig. 3A). Four weeks after surgery, both groups were subjected to the fear conditioning test, including habituation, training, and cued expression. Mice were injected with CNO (5 mg/kg) prior to the training session (Fig. 3B). There were no significant differences in the fear responses to CS (tone) presentation during either training or the cued test between mice expressing hM3Dq and those expressing mCherry (Fig. 3C), suggesting that activation of AMv CRF neurons during training did not affect the acquisition of conditioned fear responses to the auditory cue.

We also investigated the effect of inhibition of AMv CRF neurons on the conditioned fear acquisition. We injected DIO-hM4Di or DIO-mCherry into the AMv of Crh-IRES-Cre mice (Fig. 3A). Both groups were subjected to the fear conditioning test as described previously. CNO (5 mg/kg) was injected 30 min prior to the training session (Fig. 3B). There were no significant differences in the fear responses to CS (tone) presentation during either training or the cued test between mice expressing hM4Di and those expressing mCherry (Fig. 3D), suggesting that inhibition of AMv CRF neurons during training did not affect the acquisition of conditioned fear responses to the auditory cue.

Chemogenetic Activation of AMv CRF Neurons During the Cued Test Increases Odor-Cued Fear Expression

To investigate whether the role of AMv CRF neurons in the regulation of fear expression is specific to an acoustic stimulus, we replaced the tone CS with an odor CS during the fear conditioning test. Mice expressing hM3Dq or mCherry were injected with CNO (5 mg/kg) before the cued (odor) test (Fig. 4A, B). During training (day 2), in the absence of CNO, there were no significant differences in the fear responses during CS presentation between mice expressing hM3Dq and those expressing mCherry (Fig. 4C, left). Notably, both groups successfully acquired cued fear. During the cued test (day 3), in the presence of CNO, the hM3Dq group exhibited significantly increased freezing responses to the presentation of the CS compared to the mCherry group (Fig. 4C, right). These results indicate that chemogenetic activation of AMv CRF neurons during cued testing increases odor-cued fear expression.

AMv CRF Neurons Project to Wide Areas of the Cerebral Cortex and the Limbic System

To investigate the neural circuits underlying the contribution of AMv CRF neurons to cued fear memory, Crh-IRES-Cre mice were injected with AAV-DIO-EYFP for anterograde tracing (Fig. 5A, B). Four weeks after unilateral viral-vector injections into the AMv, the distribution of anterograde AMv CRF neuron fibers was traced across the brain (Table S1).

Dense ipsilateral fibers of AMv CRF neurons were found in most subregions of the prefrontal cortex, including the orbitofrontal (Fig. 5C) and prelimbic cortex (Fig. 5D). Moderate fibers were found in the basolateral amygdaloid nucleus (Fig. 5E), retrosplenial cortex (Fig. 5F), lacunosum molecular layer of CA1 (Fig. 5I), nucleus accumbens, and subiculum. Sparse outputs were found in the secondary visual cortex (Fig. 5G), ectorhinal cortex, lateral part of the entorhinal cortex, perirhinal cortex (Fig. 5H), and agranular insular cortex.

Discussion

In the present study, we reported for the first time that AMv CRF neurons play a key role in the regulation of cued fear memory in CRF transgenic mice. Chemogenetic activation of AMv CRF neurons enhanced cued fear responses, whereas their chemogenetic inhibition impaired these responses. In addition, bidirectional chemogenetic manipulation of AMv CRF neurons did not affect the acquisition of conditioned fear memory. After changing the sensory modality of the cue, the activation of AMv CRF neurons also enhanced olfactory-dependent fear expression. Furthermore, we investigated the projection patterns of AMv CRF neurons, finding that these neurons project widely to regions throughout the cerebral cortex and the limbic system, especially to the frontal cortical and hippocampal areas.

In mammals, CRF is closely associated with the regulation of stress and fear. CRF-positive neurons are widely distributed throughout the brain, including the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, central amygdala, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and thalamus [24]. Among these regions, CRF in the amygdala has been studied the most extensively [17, 25, 26]. To date, there have been few reports regarding CRF neurons in the thalamus. In the present study, we investigated the relationship between AMv CRF neurons and cued fear behaviors in mice. One way to specifically target CRF neurons is to use mice with the Cre recombinase gene driven by the CRF promoter in order to allow the CRF cells to be manipulated.

The proto-oncogene c-Fos is a commonly used marker for evaluating neuronal activity. Previous studies have reported that conditioned fear induces significant increases in c-Fos protein expression in nearly 50 brain regions, including both cortical and subcortical areas [27]. In terms of thalamic areas, both contextual and cued fear conditioning tasks significantly increase c-Fos expression in the anterior thalamus of rats [8]. Consistent with these findings, we discovered that acoustic CS exposure significantly enhanced c-Fos protein expression in the AMv CRF neurons during cued fear expression.

A previous study reported that cytotoxic lesions in the AMv drastically reduce contextual defensive responses to predatory threats [4]. In addition, pharmacological inactivation of the AMv prior to threats has been shown to reduce contextual defensive responses in rats [9]. These findings suggest that the AMv regulates fear responses to threats [6, 28]. Consistent with previous research, we found that inhibition of AMv CRF neurons impaired cued fear expression. Interestingly, manipulation of AMv CRF neurons did not affect fear acquisition or contextual fear expression, which differs from the findings of a previous study which reported that pharmacological inhibition of AMv neurons impairs predator-associated contextual fear acquisition but not cued fear expression [9]. It is possible that this difference is due to the cell type-specific manipulation in our study. In the AMv, CRF neurons represent only a small portion of cells (Fig. S1). The distinct subpopulation of AMv neurons may specifically regulate fear acquisition or expression. Our results indicate that AMv CRF neurons play a unique role in the regulation of cued fear expression. In fact, many studies have shown that CRF has a facilitatory effect on fear expression. In the caudal pontine (PnC) reticular nucleus, CRF mediates the expression of fear-potentiated startle in rats, and injections of a CRF antagonist into the PnC block fear responses to an acoustic CS in a dose-dependent manner [29]. In addition, in contextual fear-conditioned animals, i.c.v. injection of CRF induces a strong increase in the expression of fear responses [30].

In the present study, after changing the sensory modality of the cue from sound to odor, the same chemogenetically-induced enhancement in fear expression still occurred in the hM3Dq-activation group, suggesting that the increase in cued fear expression induced by activation of AMv CRF neurons does not depend on the form of the cue. Furthermore, we found that manipulation of AMv CRF neurons did not affect locomotor activity, anxiety level, or basal immobility level, suggesting that the effect of manipulation reflects an interaction with conditional fear memory.

The anterograde tracing experiment was performed in three mice in order to avoid inaccuracies caused by vector leakage from the injection sites. All of the anterograde projections presented a similar distribution pattern, from which we obtained common projection regions throughout the brain. It should be noted that there was also some EYFP expression in neurons external to the AMv, which may have affected the evaluation of the AMv CRF projection. Nevertheless, the present results are consistent with those of the previous study on the AMv projection [9]. AMv CRF neurons provided dense ipsilateral projections to wide areas of the cerebral cortex and the limbic system, including the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampal formation. Few contralateral efferent projections were observed. It is generally believed that the extensive direct/indirect mutual projections among the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus represent the neural basis of fear regulation [31]. Previous studies have shown the involvement of the mPFC in the regulation of fear expression or fear inhibition after fear extinction [32, 33]. Furthermore, the reciprocal circuits between the mPFC and BLA have been implicated in fear acquisition, expression, and extinction [34, 35]. Considering the key role of the lateral amygdalar nucleus in conditioned fear responses [36, 37], it is possible that AMv CRF neurons regulate cued fear memory via modulating the activity of both the mPFC and BLA. Furthermore, the projections of AMv CRF neurons to the hippocampal formation were also noteworthy. In addition to providing direct projections to the subiculum and CA1, AMv CRF neurons may also influence the perforant pathway through projections to the entorhinal cortex [38, 39]. The superficial layers of the medial and lateral entorhinal cortices give rise to the medial and lateral perforant pathways, respectively, which are the main pathways for information to enter the hippocampus [38]. Thus, AMv CRF neurons seem positioned to convey cue-associated information to hippocampal circuitry, a fact that may account, at least in part, for the role of this thalamic site in the expression of cued memory to harm-associated threats. Considering the important role of the hippocampus in contextual and cued fear memory [40], it is possible that AMv CRF neurons regulate cued fear expression, at least in part, through their widespread projections to the hippocampus.

It is necessary to point out that there are several limitations to the present study. First, we did not investigate the expression of c-Fos in AMv CRF neurons after the olfactory-cued fear expression test. Future studies are needed to determine whether the characteristics of c-Fos expression in AMv CRF neurons after the olfactory- or auditory-cued fear expression test are the same. Second, the altered inter-tone intervals during fear training and expression are needed in order to confirm that mice respond to the tone presentation rather than engaging in temporal anticipation of the shock presentation in the cued fear expression test. Third, the control groups in Figs. 2D and 4C exhibited rapid reductions in freezing during the cued expression test, which may have resulted in an increased probability of false positives. Future research will require an increased sample size in order to clarify the effect of AMv CRF neuronal activation on cued fear expression.

In summary, our study reveals that CRF neurons in the AMv play a key role in the processing of cued fear memory. Together with an examination of the outputs and target regions of AMv CRF neurons that may contribute to these effects, our work indicates that a network comprising AMv CRF neurons and allied cortico-hippocampal-amygdalar sites may be involved in the expression of cued fear memory. The present findings also provide new perspectives on the involvement of CRF neurons in the regulation of emotional learning, expanding our understanding of the contribution of CRFergic circuits to fear-related behaviors. Further understanding of the cell-specific modulation of CRF neurons may also provide novel and more specific targets for therapeutic intervention in disorders related to anxiety or fear.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32000716 and 91732304), and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB02030001).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Peng Chen, Email: pchen727@ustc.edu.cn.

Jiang-Ning Zhou, Email: jnzhou@ustc.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Aggleton JP, Hunt PR, Nagle S, Neave N. The effects of selective lesions within the anterior thalamic nuclei on spatial memory in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 1996;81:189–198. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(96)89080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taube JS. Head direction cells recorded in the anterior thalamic nuclei of freely moving rats. J Neurosci. 1995;15:70–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00070.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byatt G, Dalrymple-Alford JC. Both anteromedial and anteroventral thalamic lesions impair radial-maze learning in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:1335–1348. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.110.6.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carvalho-Netto EF, Martinez RCR, Baldo MVC, Canteras NS. Evidence for the thalamic targets of the medial hypothalamic defensive system mediating emotional memory to predatory threats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2010;93:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Lima MA, Baldo MVC, Canteras NS. Revealing a cortical circuit responsive to predatory threats and mediating contextual fear memory. Cereb Cortex. 2019;29:3074–3090. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross CT, Canteras NS. The many paths to fear. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:651–658. doi: 10.1038/nrn3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchand A, Faugere A, Coutureau E, Wolff M. A role for anterior thalamic nuclei in contextual fear memory. Brain Struct Funct. 2014;219:1575–1586. doi: 10.1007/s00429-013-0586-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conejo NM, González-Pardo H, López M, Cantora R, Arias JL. Induction of c-Fos expression in the mammillary bodies, anterior thalamus and dorsal hippocampus after fear conditioning. Brain Res Bull. 2007;74:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Lima MA, Baldo MVC, Canteras NS. A role for the anteromedial thalamic nucleus in the acquisition of contextual fear memory to predatory threats. Brain Struct Funct. 2017;222:113–129. doi: 10.1007/s00429-016-1204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merchenthaler I, Vigh S, Schally AV, Stumpf WE, Arimura A. Immunocytochemical localization of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF)-like immunoreactivity in the thalamus of the rat. Brain Res. 1984;323:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90272-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bale TL, Vale WW. CRF and CRF receptors: role in stress responsivity and other behaviors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:525–557. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henckens MJ, Deussing JM, Chen A. Region-specific roles of the corticotropin-releasing factor-urocortin system in stress. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:636–651. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swaab DF, Bao AM, Lucassen PJ. The stress system in the human brain in depression and neurodegeneration. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4:141–194. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang SS, Yan XB, Hofman MA, Swaab DF, Zhou JN. Increased expression level of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the amygdala and in the hypothalamus in rats exposed to chronic unpredictable mild stress. Neurosci Bull. 2010;26:297–303. doi: 10.1007/s12264-010-0329-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koob GF, Bloom FE. Corticotropin-releasing factor and behavior. Fed Proc. 1985;44:259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen P, Lou S, Huang ZH, Wang Z, Shan QH, Wang Y, et al. Prefrontal cortex corticotropin-releasing factor neurons control behavioral style selection under challenging situations. Neuron. 2020;106(301–315):e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanford CA, Soden ME, Baird MA, Miller SM, Schulkin J, Palmiter RD, et al. A central amygdala CRF circuit facilitates learning about weak threats. Neuron. 2017;93:164–178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wehner JM, Radcliffe RA. Cued and contextual fear conditioning in mice. Curr Protoc Neurosci 2004, Chapter 8: Unit8 5C. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Taniguchi H, He M, Wu P, Kim S, Paik R, Sugino K, et al. A resource of cre driver lines for genetic targeting of GABAergic neurons in cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2011;71:995–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou XH, Hyun M, Taranda J, Huang KW, Todd E, Feng D, et al. Central control circuit for context-dependent micturition. Cell. 2016;167(73–86):e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wamsteeker Cusulin JI, Fuzesi T, Watts AG, Bains JS. Characterization of corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus of Crh-IRES-Cre mutant mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konsman JP. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates: Second Edition (Deluxe) By Paxinos G and Franklin KBJ. Academic Press, New York, 2001. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003, 28: 827–828.

- 23.Ni RJ, Shu YM, Luo PH, Fang H, Wang Y, Yao L, et al. Immunohistochemical mapping of neuropeptide Y in the tree shrew brain. J Comp Neurol. 2015;523:495–529. doi: 10.1002/cne.23696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olschowka JA, O’Donohue TL, Mueller GP, Jacobowitz DM. Hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic distribution of CRF-like immunoreactive neurons in the rat brain. Neuroendocrinology. 1982;35:305–308. doi: 10.1159/000123398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray TS. Amygdaloid CRF pathways. Role in autonomic, neuroendocrine, and behavioral responses to stress. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;697:53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb49922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erb S, Salmaso N, Rodaros D, Stewart J. A role for the CRF-containing pathway from central nucleus of the amygdala to bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:360–365. doi: 10.1007/s002130000642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck CH, Fibiger HC. Conditioned fear-induced changes in behavior and in the expression of the immediate early gene c-fos: with and without diazepam pretreatment. J Neurosci. 1995;15:709–720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00709.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canteras NS, Pavesi E, Carobrez AP. Olfactory instruction for fear: neural system analysis. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:276. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fendt M, Koch M, Schnitzler HU. Corticotropin-releasing factor in the caudal pontine reticular nucleus mediates the expression of fear-potentiated startle in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skórzewska A, Bidziński A, Hamed A, Lehner M, Turzyńska D, Sobolewska A, et al. The effect of CRF and α-helical CRF(9–41) on rat fear responses and amino acids release in the central nucleus of the amygdala. Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yehuda R, LeDoux J. Response variation following trauma: a translational neuroscience approach to understanding PTSD. Neuron. 2007;56:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Senn V, Wolff SB, Herry C, Grenier F, Ehrlich I, Gründemann J, et al. Long-range connectivity defines behavioral specificity of amygdala neurons. Neuron. 2014;81:428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dejean C, Courtin J, Rozeske RR, Bonnet MC, Dousset V, Michelet T, et al. Neuronal circuits for fear expression and recovery: recent advances and potential therapeutic strategies. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klavir O, Prigge M, Sarel A, Paz R, Yizhar O. Manipulating fear associations via optogenetic modulation of amygdala inputs to prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:836–844. doi: 10.1038/nn.4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burgos-Robles A, Kimchi EY, Izadmehr EM, Porzenheim MJ, Ramos-Guasp WA, Nieh EH, et al. Amygdala inputs to prefrontal cortex guide behavior amid conflicting cues of reward and punishment. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:824–835. doi: 10.1038/nn.4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fanselow MS, Gale GD. The amygdala, fear, and memory. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;985:125–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis M. The role of the amygdala in fear and anxiety. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1992;15:353–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.002033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swanson LW, Köhler C, Björklund A. The limbic region. I. The septohippocampal system. In: Björklund A, Hökfelt T, Swanson LW (eds) Handbook of chemical neuroanatomy, vol 5. Integrated systems of the CNS, part I. Elsevier, 1987: 125–277.

- 39.Ding SL. Comparative anatomy of the prosubiculum, subiculum, presubiculum, postsubiculum, and parasubiculum in human, monkey, and rodent. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:4145–4162. doi: 10.1002/cne.23416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunsaker MR, Kesner RP. Dissociations across the dorsal–ventral axis of CA3 and CA1 for encoding and retrieval of contextual and auditory-cued fear. Neurobiol learn Mem. 2008;89:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.