Abstract

Through the efforts of many groups, a wide range of fluorescent protein reporters and sensors based on green fluorescent protein and its relatives have been engineered in recent years. Here we explore the incorporation of sensing modalities into de novo designed fluorescence-activating proteins, called mini-fluorescence-activating proteins (mFAPs), that bind and stabilize the fluorescent cis-planar state of the fluorogenic compound DFHBI. We show through further design that the fluorescence intensity and specificity of mFAPs for different chromophores can be tuned, and the fluorescence made sensitive to pH and Ca2+ for real-time fluorescence reporting. Bipartite split mFAPs enable real-time monitoring of protein–protein association and (unlike widely used split GFP reporter systems) are fully reversible, allowing direct readout of association and dissociation events. The relative ease with which sensing modalities can be incorporated and advantages in smaller size and photostability make de novo designed fluorescence-activating proteins attractive candidates for optical sensor engineering.

Subject terms: Wide-field fluorescence microscopy, Fluorescent proteins, Protein design, X-ray crystallography

Fluorescent protein reporters based on GFP exist, but have intrinsic disadvantages. Here the authors incorporate pH, Ca2+ and protein–protein interaction sensing modalities into de novo designed mini-fluorescence-activating proteins (mFAPs), with increased photostability and smaller size, which bind a range of DFHBI chromophore variants.

Introduction

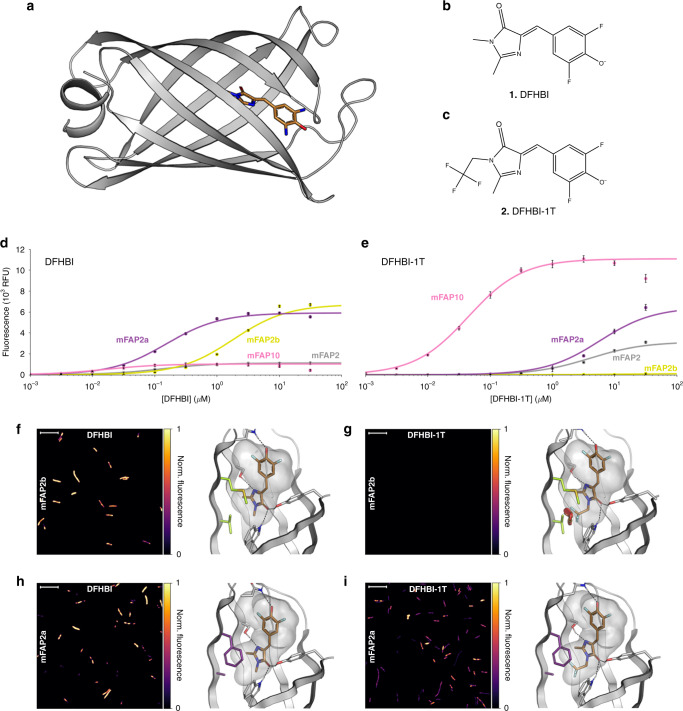

De novo designed mini-fluorescence-activating proteins (mFAPs) (Fig. 1a) bind and activate the fluorescence of the fluorogenic compound DFHBI (3,5-difluoro-4-hydroxybenzylidene imidazolinone) (1, Fig. 1b) in vitro and in bacteria, yeast, and mammalian cells1. DFHBI does not fluoresce when free in solution2, but becomes brightly fluorescent upon stabilization of the cis-planar conformation (planar Z conformation) through macromolecular binding3. RNA aptamers have been evolved to bind similar fluorogenic DFHBI-derived compounds4,5 (e.g., DFHBI, DFHBI-1T [(Z)-4-(3,5-difluoro-4-hydroxybenzylidene)-2-methyl-1-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)-1H-imidazol-5(4 H)-one] (2, Fig. 1c) and DFHO [3,5-difluoro-4-hydroxybenzylidene imidazolinone-2-oxime]), with up to 0.72 fluorescence quantum yield6, but to our knowledge so far no protein-based systems other than the mFAPs have been reported to bind and fluorescently activate DFHBI-1T or DFHO chromophores.

Fig. 1. Characterization of brighter and chromophore-specific mFAPs.

a Computational model of de novo designed β-barrel variant mFAP2b showing protein backbone (cartoon) and bound DFHBI chromophore (sticks). b, c Chemical structures of DFHBI and DFHBI-1T, respectively. d, e In vitro titration of d DFHBI or e DFHBI-1T with mFAP2 (gray), mFAP2b (lime), mFAP2a (violet), and mFAP10 (pink) proteins. Error bars represent s.d. of the mean of eight technical replicates. Normalized means were fit to a single-binding site isotherm function using non-linear least squares fitting to obtain Kd values (Table 1), and the fits scaled to the maximum mean relative fluorescence unit (RFU) values (lines). f–i Each panel shows a representative image of the fluorescence signal emitted by E. coli cells expressing the indicated mFAP variant labeled with 10.0 µM concentration of the indicated chromophore (left) and a zoom-in of the modeled-binding pocket of that mFAP variant bound to the chromophore (right). The images (left) are the pseudocolored normalized fluorescence intensity per pixel. Scale bars represent 10 microns. Imaging was independently repeated twice with similar results. The computational models (right) show the residues unique to mFAP2b (V13, M15) (lime sticks) or mFAP2a (A13, F15) (violet sticks). Intermolecular hydrogen bonds to the chromophore are shown as black dotted lines. Vacuum electrostatic contact potential around the chromophore is shown in a transparent gray surface. f mFAP2b with DFHBI, g mFAP2b with DFHBI-1T does not emit a detectable fluorescence signal because binding is precluded by steric clashes of DFHBI-1T with V13 (red cylinders), h mFAP2a with DFHBI, and i mFAP2a with DFHBI-1T. Source data is available for Fig. 1f–i.

Circularly permuted fluorescent proteins such as cpGFP and cpFAST enable the real-time detection of analytes of interest using fluorescence microscopy7–9. Likewise, self-complementing split fluorescent protein reporter systems based on green fluorescent protein (GFP) variants10–12 and FAST13 have been engineered to monitor protein–protein interactions in vitro, in cyto, and in vivo14 using fluorescence microscopy. The β-barrel structure of mFAPs suggests that mFAPs could be re-designed to monitor analyte fluxes and protein–protein interactions; such sensors could have complementary biophysical properties to existing fluorescent proteins (such as intrinsically fluorescent GFP and extrinsically fluorogenic DiBs15, Y-FAST16, Ca2+-responsive cpFAST7, and splitFAST13 reporters and sensors).

mFAPs have several biophysical properties that make them attractive candidates for further development. First, they are less than half the size of GFP, so their genetic footprint is smaller, and fusions to proteins of interest are less perturbative. Second, the bound chromophore can readily exchange with free chromophore in solution, and hence mFAPs can be more photostable17 than GFP. Third, chemical derivatives of DFHBI with different fluorescence properties can be fluorescently activated, providing more control over color (i.e., fluorescence excitation and emission wavelength) than intrinsically fluorescent proteins7. Fourth, de novo mFAPs can be engineered to remain folded at low pH, facilitating the engineering of pH-responsive fluorogenic optical sensors. Finally, the chromophore-binding pocket is close to the protein surface, potentially enabling the design of allosteric coupling between chromophore binding and linked analyte binding domains for analyte-responsive fluorogenic optical sensors7,18,19.

Here, we explore the incorporation of sensing modalities into the mFAPs. We develop and apply methodologies for engineering chromophore-selective, pH-responsive, Ca2+-responsive, bipartite, and circularly permuted optical sensors based on de novo designed fluorescence-activating proteins.

Results

Optimizing brightness and chromophore selectivity

We began by seeking to improve the stability of mFAPs at low pH, the binding affinity to the phenolic and phenolate forms of DFHBI, as well as the fluorescence intensity of both complexes. mFAP2 was chosen for optimization because it has the highest absolute fluorescence quantum yield (ϕc of 2.1%) and highest affinity (Kd of ~180 nM) for the phenolate form of DFHBI compared to mFAP11. Through a series of library selections (see “Methods”) targeting aliphatic and aromatic residues directly interacting with DFHBI or in the hydrophobic core of the β-barrel, as well as residues in the loop connecting the seventh and eighth β-strands (loop7) of the β-barrel, we obtained three brighter and chromophore-selective mFAP2 variants: mFAP2a, mFAP2b, and mFAP10 that incorporate 12, 10, and 11 mutations, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Titrations of mFAP2, mFAP2a, mFAP2b, and mFAP10 with either DFHBI (Fig. 1d) or DFHBI-1T (Fig. 1e) and quantum yield measurements (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2) showed that: mFAP2, mFAP2a, and mFAP10 have ~2.7-fold, ~2.5-fold, and ~12-fold brighter fluorescence with DFHBI-1T than DFHBI, but bind DFHBI with ~30-fold, ~39-fold, and ~2.6-fold higher affinity than DFHBI-1T, respectively; and that mFAP2b has ~30-fold brighter fluorescence with DFHBI than DFHBI-1T and binds DFHBI with ~6.1-fold higher affinity than DFHBI-1T. The mFAP10–DFHBI-1T complex is the brightest, with 23.7% absolute quantum yield (under conditions with 99.9% of chromophore bound) and a 17.5-fold increased brightness over the previously reported mFAP2–DFHBI complex1, resulting in a 242-fold fluorescence activation over free DFHBI-1T (Table 1). Relative fluorescence intensities and thermodynamic dissociation constants (Kd) for the deprotonated (phenolate) states of DFHBI, DFHBI-1T, and DFHO for the Ca2+-independent mFAP variants presented in this study are given in Supplementary Table 1 (for example, mFAP3 binds the yellow colored DFHO chromophore with ~10-fold lower fluorescence intensity than mFAP2b with DFHBI). Using a laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscope to image E. coli expressing either mFAP2a or mFAP2b labeled with either DFHBI or DFHBI-1T, we observed pronounced chromophore selectivity of mFAP2b for DFHBI over DFHBI-1T, and chromophore promiscuity of mFAP2a for both DFHBI or DFHBI-1T (Fig. 1f–i). E. coli cultures expressing either mFAP2a or mFAP2b mixed in a 1:1 cellular ratio labeled with DFHBI-1T have ~49% of the total fluorescence signal of cultures labeled with DFHBI (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of mFAPs with DFHBI and DFHBI-1T compared with controls.

| λabs (nm)a | λex (nm)a | λem (nm)a | Extinction coefficient (M−1 cm−1)b | Brightness (M−1 cm−1)c |

Absolute quantum yieldd | Relative quantum yieldd | Reported quantum yield | % Bound | Kd (μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFP | – | 488f | 507f | 56,000f | 33,600f | – | – | 0.60f | – | – |

| mFAP2a + DFHBI | 491 | 491 | 505 | 64,900 | 3890 | 0.060 | 0.063 | – | 99.9 | 0.15 ± 0.011 |

| mFAP2a + DFHBI-1T | 492 | 493 | 505 | 75,100 | 9690 | 0.129 | 0.128 | – | 95.8 | 5.8 ± 0.86 |

| mFAP2b + DFHBI | 495 | 495 | 509 | 60,500 | 5630 | 0.093 | 0.099 | – | 99.1 | 1.8 ± 0.25 |

| mFAP2b + DFHBI-1T | 430 | 494 | 505 | 37,800 | 189 | 0.005 | 0.003 | – | 95.1 | 11 ± 3.1 |

| mFAP10 + DFHBI | 470 | 475 | 497 | 48,900 | 1290 | 0.026 | 0.029 | – | 100.0 | 0.017 ± 0.0079 |

| mFAP10 + DFHBI-1T | 484 | 485 | 503 | 67,200 |

15,900 (2.1x dimmer than EGFP) |

0.237 | 0.230 | – | 99.9 | 0.045 ± 0.0065 |

| DFHBI | 418e | 423e | 489e |

30,100e 31,935f |

– | 0.001f | – | 0.0007e | – | – |

| DFHBI-1T | 422e | 426e | 495e | 35,400e | – | – | – | 0.00098e | – | – |

The % bound values are calculated based on the reported Kd values and final protein and chromophore concentrations used in quantum yield measurements. Kd values are obtained by non-linear least squares fits to the mean fluorescence intensities of the eight technical replicates per chromophore titration (Fig. 1d, e). Kd error estimates are s.d. of the mean of the non-linear least squares fits.

aλabs is peak absorbance wavelength, λex is peak excitation wavelength, and λem is peak emission wavelength (Supplementary Fig. 2).

bExtinction coefficients are measured from λabs estimated based on 1 data point in this study.

cBrightness is defined as extinction coefficient multiplied by absolute quantum yield.

dAbsolute quantum yield is the average of ten scans measured with an integrating sphere; relative quantum yield is reported using Acridine Yellow G54 and fluorescein as reference standards.

ePreviously reported value4.

fPreviously reported value1.

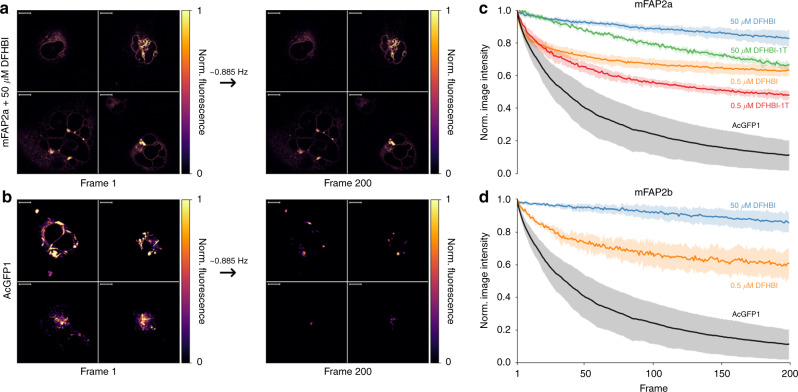

We next targeted mFAP2a or mFAP2b to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of mammalian COS-7 cells using a C-terminal sec61β localization sequence, and observed bright fluorescence of ER under fixed cell (Supplementary Fig. 4) and live cell (Supplementary Movie 1 and Supplementary Movie 2) epifluorescence microscopy after labeling with DFHBI. Under fixed cell imaging, following washing and re-labeling with DFHBI-1T (Supplementary Fig. 4) the fluorescence was altered as expected, demonstrating external spatiotemporal control over fluorescence. To compare the photostability of mFAP2a and mFAP2b to a monomeric enhanced GFP (EGFP) variant, we also targeted AcGFP1 to the ER of COS-7 cells. Upon continuous wave illumination imaging at ~0.885 Hz (1.13 s frame−1) of fixed COS-7 cells using laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy, we found at 50.0 µM chromophore (saturating conditions) a 6.2-fold, 3.5-fold, and 6.1-fold improved photostability of mFAP2a–DFHBI, mFAP2a–DFHBI-1T, and mFAP2b–DFHBI complexes over AcGFP1, respectively. At 500 nM chromophore (sub-saturating conditions), the improvements in photostability of the three complexes over AcGFP1 were 5.0-fold, 3.8-fold, and 4.7-fold, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Photostability of mFAPs compared to AcGFP1.

a, b Normalized fluorescence intensity images for four regions of interest (ROIs) acquired under continuous wave imaging at ~0.885 Hz (1.13 s frame−1) shown for frame 1 (left) and frame 200 (right) of fixed COS-7 cells expressing endoplasmic reticulum-targeted a mFAP2a labeled with 50.0 µM DFHBI compared to b AcGFP1. Scale bars represent 10 microns. c, d Means (lines) and s.d. of the means (shading) of the normalized summed pixel intensities of four ROIs (n = 4) under continuous wave imaging (~0.885 Hz) for c mFAP2a labeled with 50.0 µM DFHBI (~330-fold above Kd) (blue), 500 nM DFHBI (~3.3-fold above Kd) (orange), 50.0 µM DFHBI-1T (~8.6-fold above Kd) (green), or 500 nM DFHBI-1T (~12-fold below Kd) (red) compared to AcGFP1 (black), and d mFAP2b labeled at 50.0 µM DFHBI (~28-fold above Kd) (blue) or 500 nM DFHBI (~3.6-fold below Kd) (orange) compared to AcGFP1 (black). Source data is available for Fig. 2.

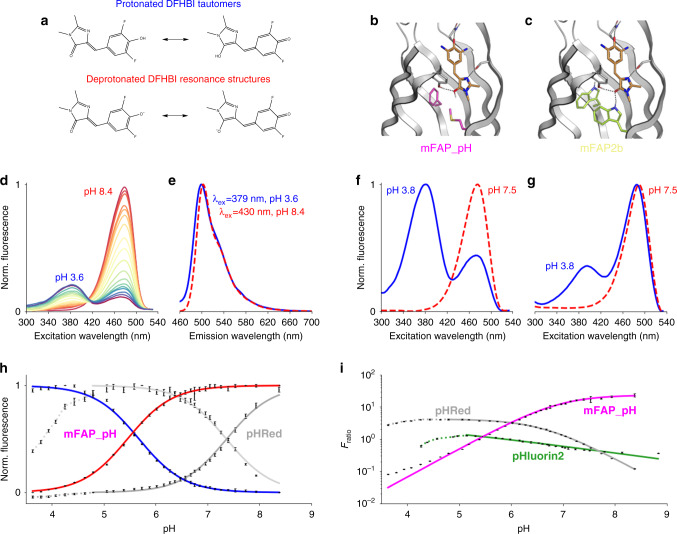

Incorporation of pH-responsiveness

A prerequisite for designing a robust pH-responsive mFAP is the ability to bind both protonated (phenolic) DFHBI tautomers and both deprotonated (phenolate) DFHBI resonance structures (Fig. 3a). When stabilized in the cis-planar conformation, the phenolic and phenolate forms of DFHBI exhibit blueshifted and redshifted peak excitation wavelengths, respectively6 (Fig. 3d). mFAP2b binds both forms of DFHBI (Fig. 3g); to increase pH sensitivity we screened design variants based on the change in fluorescence between pH 3.61 and pH 7.34 (Supplementary Fig. 5), and identified a particularly pH-responsive variant we call mFAP_pH. Computational models (Fig. 3b, c) suggest that the amino acid substitutions in mFAP_pH compared to mFAP2b (i.e., W27M and W93F) improve pH-responsiveness of the protein–DFHBI complex by increasing shape complementarity toward the protonated (phenolic) form of DFHBI by removing a hydrogen bond between the W27 indole ring and the DFHBI imidazolinone moiety, and by reducing net positive charge in the β-barrel core via removing a buried unsatisfied hydrogen bond donor in the indole ring of W93, resulting in a higher ratio of protein-bound phenolic DFHBI to phenolate DFHBI at low pH (Fig. 3f, g). The phenolic and phenolate forms of DFHBI had nearly equivalent affinities (Kd values) for mFAP_pH of ~190 nM and ~160 nM, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). The pKa of free, unbound DFHBI in solution5 is ~5.4, and we observe the same pKa for the mFAP_pH–DFHBI complex (Fig. 3h).

Fig. 3. Characterization of pH-responsive mFAP_pH.

a–c Chemical basis of pH-responsiveness in mFAP_pH. a Chemical structures of protonated tautomers and deprotonated resonance structures of DFHBI. b, c Computational models showing the residues unique to b mFAP_pH (M27, F93) (magenta) and c mFAP2b (W27, W93) (lime). The arrangement of intermolecular hydrogen bonds (black dotted lines) in b the mFAP_pH–DFHBI complex permits binding to both the phenolate and phenolic (shown) forms of DFHBI whereas of c the mFAP2b–DFHBI complex only permits binding to the phenolate (shown) form of DFHBI. d Normalized fluorescence excitation spectra of the mFAP_pH–DFHBI complex for a pH titration between pH 3.6 and pH 8.4. e Normalized fluorescence emission spectra of the mFAP_pH–DFHBI complex at pH 3.6 and pH 8.4. f, g Fluorescence excitation spectra normalized to pH 3.8 and pH 7.5 of f pH-responsive mFAP_pH–DFHBI complex and g pH-unresponsive mFAP2b–DFHBI complex. h Normalized mean (n = 3) fluorescence intensity from the pH titration of the mFAP_pH–DFHBI complex (blue and red) and previously reported pHRed (dark gray and light gray), showing fluorescence emission by exciting the blueshifted fluorescence excitation peak (blue and dark gray) and fluorescence emission by exciting the redshifted fluorescence excitation peak (red and light gray). i Ratiometric fluorescence (Fratio) from the pH titration of the mFAP_pH–DFHBI complex (magenta), pHRed (gray), and pHluorin2 (green). h, i The means are fit to h a sigmoid or inverse sigmoid function or i a logistic function using non-linear least squares fitting (lines). The dotted lines indicate pH values at which the measured Fratio coincides with two different pH values, and therefore are not used in the fittings. Error bars represent the s.d. of the mean of three technical replicates.

At peak excitation and emission wavelengths (Fig. 3d, e), mFAP_pH showed a marked ~250-fold-change in ratiometric fluorescence (Fratio, see “Methods”) from pH 8.38 to pH 3.63, compared with only a ~34-fold-change in Fratio from pH 8.38 to pH 4.79 for pHRed20 and a ~3.5-fold-change in Fratio from pH 8.83 to pH 5.14 for pHluorin221 (Fig. 3i). At low pH, the β-barrel fold of mFAP_pH is more resistant to denaturation than those of pHRed and pHluorin2, and thus the mFAP_pH–DFHBI complex has a higher dynamic range for ratiometric fluorescence across the physiologically relevant pH range. Ratiometric fluorescence imaging of the mFAP_pH–DFHBI complex hence should enable real-time in situ quantification of pH.

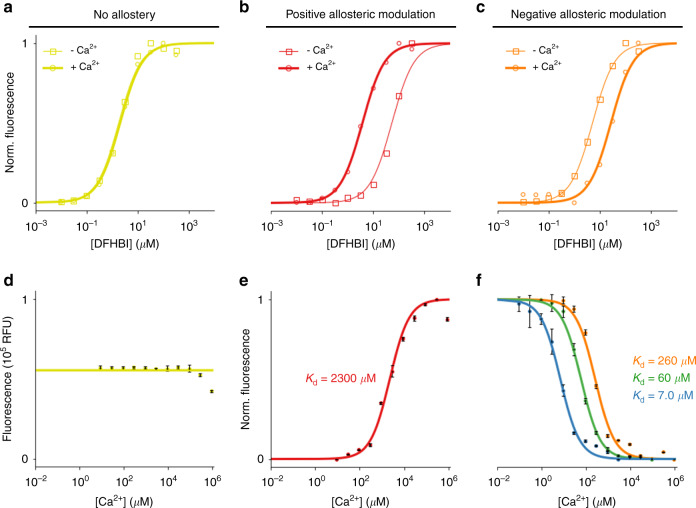

Incorporation of Ca2+-responsiveness

To enable the engineering of additional environmental responsiveness in mFAPs, we used Rosetta22,23 to de novo design 59 extensions of β-barrel loops 1, 3 and 7, and screened them for fluorescence after labeling with DFHBI. We identified five extended loop7 variants that maintain the β-barrel fold and are compatible with DFHBI binding (Supplementary Fig. 6). Using these extended loop sequences as linkers (see “Methods”), we grafted one EF-hand motif24, one EF-hand domain25 (i.e., two EF-hand motifs), or calmodulin26 (i.e., four EF-hand motifs) into loop7 of mFAP2b (Supplementary Fig. 7). Through DFHBI and Ca2+ titrations, we found that Ca2+ binding was allosterically coupled to DFHBI binding, with either positive7 or negative8 allosteric modulation of fluorescence (Fig. 4) depending only on the amino acid sequence of the linkers. As expected based on the cooperativity of Ca2+ binding to calmodulin27,28, we found that as the number of grafted EF-hand motifs increases, so does the affinity for Ca2+ ions (Fig. 4f). While some existing fluorescent Ca2+ sensors harboring calmodulin such as GCaMP6f29 are characterized by Hill coefficients of ~2–3, Ca2+-responsive mFAPs are characterized by Hill coefficients of ~1 (similar to previously reported ratiometric-pericam8, CatchER18, and XCaMPs30), suggesting that one Ca2+-binding site is allosterically coupled to chromophore affinity (Supplementary Table 2). Circular dichroism experiments showed that Ca2+ binding increases the α-helical secondary structure, presumably in the calmodulin domain, and enhances thermostability for EF4n_mFAP2b harboring calmodulin (Supplementary Fig. 8).

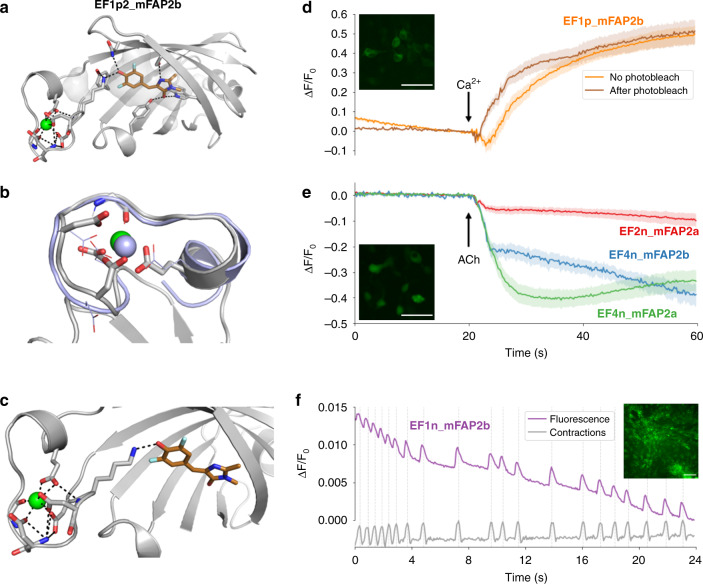

Fig. 4. In vitro characterization of Ca2+-responsive mFAPs.

a–c DFHBI titration in the absence of Ca2+ (squares) and presence of Ca2+ (circles). a For mFAP2b, Ca2+ does not affect DFHBI binding. b For EF1p2_mFAP2b, binding of Ca2+ and DFHBI exhibit positive allostery. c For EF1n_mFAP2b, binding of Ca2+ and DFHBI exhibit negative allostery. a–c Normalized fluorescence intensities (n = 1) are fit to a sigmoid function using non-linear least squares fitting (lines). d–f Ca2+ titrations with excess DFHBI concentration compared to protein concentration. d Unnormalized mean fluorescence intensities of mFAP2b demonstrating a lack of Ca2+-responsiveness. e Normalized mean fluorescence intensities of EF1p2_mFAP2b (with one EF-hand motif, Kd = 2300 µM) demonstrating positive allostery between DFHBI and Ca2+ binding. f Ca2+-responsiveness is dependent on the number of EF-hand motifs inserted into loop7, as exemplified by the normalized mean fluorescence intensities of EF1n_mFAP2b (with one EF-hand motif, Kd = 260 µM), EF2n_mFAP2b (with two EF-hand motifs, Kd = 60 µM), and EF4n_mFAP2b (with four EF-hand motifs, Kd = 7.0 µM), demonstrating negative allostery between DFHBI and Ca2+ binding. d–f Error bars represent the s.d. of the mean of three technical replicates. The means (n = 3) are fit to a d constant function, or e sigmoid or f inverse sigmoid function with Hill coefficients of 1, using non-linear least squares fitting (lines) to obtain Kd values (Supplementary Table 2).

Incorporation of the mFAP2a hydrophobic core amino acid substitutions (A13, F15) (Supplementary Fig. 9) increased Ca2+ affinity by up to 11.7-fold for positively allosteric proteins and decreased Ca2+ affinity by up to 11.6-fold for negatively allosteric proteins (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figs. 10, 11, 12, 13). The substitutions increase the affinity of DFHBI binding (Fig. 1d), and DFHBI and Ca2+ titration data indicate thermodynamic coupling between DFHBI and Ca2+ binding (Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Note 1). Overall, the Ca2+-responsive mFAPs exhibit over 500-fold differences in affinity for Ca2+ (Supplementary Table 2), enabling the choice of a sensor with optimal fluorescence dynamic range in the anticipated Ca2+ concentration range under study.

To investigate the origin of the allosteric coupling between Ca2+ and DFHBI binding, we solved an X-ray crystal structure (Supplementary Table 3) of one of the positively allosteric Ca2+-responsive mFAPs harboring one EF-hand motif, EF1p2_mFAP2b, in complex with DFHBI and Ca2+ (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 15). The EF1p2_mFAP2b–DFHBI–Ca2+ co-crystal structure revealed the residue K101 from the Ca2+-bound EF-hand motif forms a hydrogen bond to the hydroxybenzylidene moiety of DFHBI, providing structural insight into the allosteric coupling mechanism between DFHBI and Ca2+ binding (Fig. 5c). Indeed, the K101A lysine-to-alanine substitution in EF1p2_mFAP2b reduces DFHBI affinity ~21-fold in the presence of excess Ca2+ (), and Ca2+ affinity ~29-fold in the presence of excess DFHBI, compared with EF1p2_mFAP2b (Supplementary Fig. 16). This lysine residue is the second amino acid of the first EF-hand motif in all of the Ca2+-responsive mFAPs, suggesting it influences the allostery in each case. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations starting from the X-ray crystal structure coordinates of EF1p2_mFAP2b in four conditions (apo, Ca2+-bound, DFHBI-bound and with both Ca2+ and DFHBI) suggest Ca2+ binding to loop7 shifts the free energy landscape towards the holo (fluorescently active) conformation even in the absence of DFHBI (Supplementary Fig. 17), suggesting a conformational selection31,32 mechanism consistent with the experimentally observed allosteric coupling of DFHBI and Ca2+ binding (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Fig. 5. Structural and in cell characterization of Ca2+-responsive mFAPs.

a–c X-ray co-crystal structure of EF1p2_mFAP2b bound to DFHBI and Ca2+ at 2.1 Å resolution. a Structure of monomer with Ca2+ (green sphere) and DFHBI (copper sticks) bound, with protein side-chains (gray sticks) forming first- and second-shell hydrogen bonds with Ca2+ and DFHBI (black dotted lines), and vacuum electrostatic contact potential around DFHBI (transparent gray surface). b Aligned is the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) solution structure from PDB accession code 1NKF (violet cartoon and lines) with La3+ ion bound (violet sphere) having the closest Cα-Cα root mean square deviation (2.19 Å) to the structure of the grafted EF-hand motif (gray sticks and cartoon) with bound Ca2+ ion (green sphere). c Co-crystal structure of EF-hand motif residues (gray sticks) reveals that residue K101 from the EF-hand motif directly hydrogen bonds (black dotted lines) with DFHBI, suggesting an allosteric coupling mechanism between Ca2+ (green sphere) and DFHBI (copper sticks) binding. d Fluorescence imaging of Ca2+ titrations (beginning at arrow) of live HEK293 cells expressing extracellular EF1p_mFAP2b, demonstrating positive allostery in cyto. Average fluorescence fold-change (lines) and s.e.m. (shading) is shown for regions of interest (ROIs) surrounding single cells without photobleaching (orange; n = 15) or after a photobleaching challenge (dark orange; n = 15) from three technical replicates. e Fluorescence imaging of acetylcholine (ACh) stimulations (added at arrow) of live HEK293 cells expressing cytosolic either EF2n_mFAP2a (red), EF4n_mFAP2b (blue), or EF4n_mFAP2a (green), demonstrating negative allostery in cyto. Average fluorescence fold-change (lines) and s.e.m. (shading) are shown for ROIs surrounding single cells expressing EF2n_mFAP2a (n = 15), EF4n_mFAP2b (n = 10), or EF4n_mFAP2a (n = 15) from three technical replicates (Table 2). f Fluorescence imaging of live human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes expressing sarcoplasmic reticulum-targeted EF1n_mFAP2b (violet) labeled with DFHBI at approximately (Supplementary Table 2) showing whole field of view normalized fluorescence fold-change, demonstrating negative allostery in cyto. The normalized average of three ROI traces in the fluorescence channel (gray) indicate peak cardiac contraction frames (dotted lines). d–f Representative whole field of view pseudocolored maximum intensity z-axis projections. Scale bars represent d, e 50 and f 100 microns. Source data is available for Fig. 5d–f.

To explore whether the Ca2+-responsive mFAPs could detect Ca2+ fluxes in mammalian cells, we first expressed a positively allosteric Ca2+-responsive mFAP harboring one EF-hand motif, EF1p_mFAP2b, in the extracellular matrix of HEK293 cells by fusion to an N-terminal immunoglobulin κ-chain leader sequence secretion signal and a C-terminal transmembrane anchoring domain from platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR). To optimize detection sensitivity and photostability while compromising on fluorescence dynamic range (see Supplementary Note 1), we chose to label HEK293 cells with DFHBI concentrations at approximately the for EF1p_mFAP2b, where and are the DFHBI Kd for the Ca2+-bound or Ca2+-free sensor, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). Titration of Ca2+ from 0 to 10 mM final concentration under constant DFHBI concentration resulted in a fluorescence fold-change () of ~0.5 (Fig. 5d). The fluorescence response was similar after photobleaching the cells, presumably due to the high-chromophore concentrations improving the photostability of mFAPs (Fig. 2).

Next, we expressed negatively allosteric Ca2+-responsive mFAPs containing two or four EF-hand motifs (EF2n_mFAP2a, EF4n_mFAP2b, and EF4n_mFAP2a) in the cytosol of HEK293 cells and stimulated Ca2+ release into the cytosol via endogenous muscarinic receptors19 by treatment with 100 μM acetylcholine (ACh). As expected, Ca2+ release into the cytosol resulted in a decrease in fluorescence upon ACh stimulation (Fig. 5e and Table 2) with DFHBI concentrations at approximately , which balances detection sensitivity and photostability against fluorescence dynamic range (Supplementary Note 1). Compared to the positive control fluorescent Ca2+ sensor29 GCaMP6f (Supplementary Fig. 18), the Ca2+-responsive mFAPs have lower fluorescence dynamic range at the DFHBI concentrations used, but are highly photostable (Fig. 5e, first 20 s).

Table 2.

Fluorescence response to acetylcholine stimulation of HEK293 cells expressing cytosolic Ca2+-responsive mFAPs or GCaMP6f.

| Sensor | Peak | [DFHBI] (µM) | Regions of interest | Fluorescence response to increased [Ca2+] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF2n_mFAP2a | 0.12 ± 0.092 | 20.0 | 15 | Negative |

| EF4n_mFAP2b | 0.42 ± 0.14 | 43.3 | 10 | Negative |

| EF4n_mFAP2a | 0.46 ± 0.12 | 43.3 | 15 | Negative |

| GCaMP6f | 11 ± 1.8 | 0.00 | 12 | Positive |

As the fluorescence of negatively allosteric Ca2+-responsive mFAPs increases when the Ca2+ concentration decreases, negatively allosteric Ca2+-responsive mFAPs enable reporting Ca2+ effluxes from compartments as increases in fluorescence signal (similar to inverse-pericam8,33 Ca2+-responsiveness). We expressed a negatively allosteric Ca2+-responsive mFAP containing one EF-hand motif, EF1n_mFAP2b, in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) of cultured human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes (CMs), as existing Ca2+-responsive fluorescent protein sensors targeted to the SR report Ca2+ effluxes as decreases in fluorescence signal34,35. Again optimizing photostability while compromising on fluorescence fold-change, we chose to label CMs with a DFHBI concentration at approximately for EF1n_mFAP2b (Supplementary Table 2). Ca2+ transients in the SR during cardiac contraction cycling were detectable with high photostability (Supplementary Fig. 19). Labeling CMs with DFHBI concentrations at approximately for EF1n_mFAP2b (Supplementary Table 2) resulted in robustly detectable Ca2+ transients during cardiac contraction cycling and moderate photostability using ~3-fold higher laser power density (Fig. 5f). The image acquisition rate in these experiments was ~16.7 Hz (60 ms frame−1), suggesting that EF1n_mFAP2b responds to Ca2+ fluxes in less than 60 ms. Temporal analysis averaged over 20 cardiac contraction cycles revealed a 96 ± 45 ms (mean ± s.d.) lag time between peak SR fluorescence and peak cardiac contraction, indicating that endogenous SR Ca2+ signaling precedes cardiomyocyte contractile motion. Inhibition of Ca2+ reuptake into the SR by treatment with cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) resulted in a sustained increase in fluorescence in the SR consistent with inhibition of SERCA pumps34,36 (Supplementary Fig. 19).

Split fluorescence-activating proteins

We next sought to design bipartite split fluorogenic sensors13 from mFAPs by creating split points in the β-hairpins and loop7 of the mFAP2a scaffold. With eight β-strands1 per β-barrel, there are seven possible bipartite split mFAPs (Supplementary Fig. 20). As the split mFAP fragments would have solvent-exposed hydrophobic patches that could hamper solubility, we initially tagged split mFAP fragments to maltose-binding protein (MBP) to improve soluble expression levels. β-barrel complementation assays in excess DFHBI-1T showed that split mFAP fragments m12 and m38 displayed the highest fluorescence activation above background, with 7.34-fold higher mean fluorescence intensity over mean background fluorescence intensity. After background subtraction, the brightest fragment combination, m12 and m38, had 184-fold higher mean fluorescence intensity than the dimmest fragment combination, m1 and m28. Differences in the fluorescence excitation spectra of the fluorescently active β-barrel complexes in excess DFHBI-1T suggest that bipartite split mFAPs stabilize the fluorescently active cis-planar conformation of DFHBI-1T in slightly different chromophore environments (Supplementary Fig. 20).

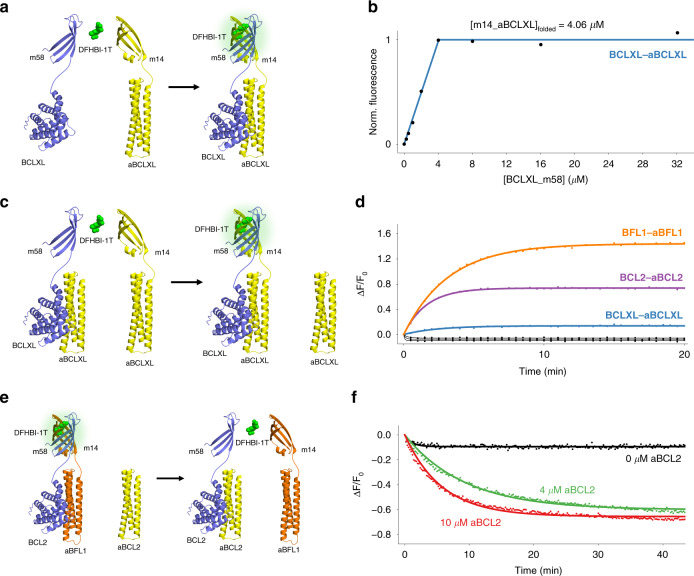

Titrations of MBP-tagged split mFAP fragments into their complementary MBP-tagged split mFAP fragments in excess DFHBI-1T resulted in reconstitution of fluorescence at high-protein concentrations, but the signal did not plateau even at the highest concentrations tested. The estimated split mFAP fragment dissociation constants (Kd values) are ≥281 µM for m12 and m38, ≥22.0 µM for m14 and m58, ≥232 µM for m16 and m78, and ≥354 µM for m17 and m8 (Supplementary Fig. 20). In contrast, when we fused complementary split mFAP fragments to BCL2 family member proteins and high affinity (Kd 1 nM) designed binding partners37 (Fig. 6a), the fluorescence increased linearly until reaching a plateau at equimolar concentrations of complementary split mFAP fragments (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6. Assembly and disassembly of bipartite split mFAP fragments m14 and m58.

a–d Assembly of split mFAP fragments. a Association model in which BCLXL is fused to m58 (BCLXL_m58) (violet cartoon), aBCLXL is fused to m14 (m14_aBCLXL) (yellow cartoon), and fluorescence of DFHBI-1T (green spheres) is activated upon association (arrow) of BCLXL_m58 and m14_aBCLXL. b Normalized fluorescence intensity (points) of BCLXL_m58 titration into a constant m14_aBCLXL concentration in excess DFHBI-1T after reaching equilibrium, showing the fit to a bimolecular association model (line) using non-linear least squares fitting. c Split mFAP competitor pre-incubation model in which fluorescence of DFHBI-1T (green spheres) is activated upon competition (arrow) of m14_aBCLXL with unfused aBCLXL (yellow cartoons) for the BCLXL-binding cleft of BCLXL_m58 (violet cartoon) (the reaction evolves analogously for BFL1–aBFL1 and BCL2–aBCL2 cognate-binding partners). d Temporal evolution of fluorescence fold-change in excess DFHBI-1T upon (n = 1) addition of equimolar m14_aBFL1 (orange points) or buffer (black points) to pre-incubated equimolar BFL1_m58 and aBFL1, addition of equimolar m14_aBCL2 (violet points) or buffer (black points) to pre-incubated equimolar BCL2_m58 and aBCL2, and addition of equimolar m14_aBCLXL (blue points) or buffer (black points) to pre-incubated equimolar BCLXL_m58 and aBCLXL, showing the fits to a monophasic exponential function (lines) using non-linear least squares fitting. e, f Disassembly of split mFAP fragments. e Pre-assembled split mFAP competition model in which BCL2 is fused to m58 (BCL2_m58) (violet cartoon), aBFL1 is fused to m14 (m14_aBFL1) (orange cartoon), and fluorescence of DFHBI-1T (green spheres) is activated before unfused aBCL2 (yellow cartoon) competes with m14_aBFL1 for the BCL2-binding cleft of BCL2_m58 (arrow), resulting in fluorescence deactivation. f Temporal evolution of fluorescence fold-change in excess DFHBI-1T of pre-incubated equimolar BCL2_m58 and m14_aBFL1 at 2.00 µM final concentrations with unfused aBCL2 titrated in at (n = 1) 0 µM (black points), 4.00 µM (green points), and 10.0 µM (red points) final concentrations, showing the fits to a monophasic exponential function (lines) using non-linear least squares fitting. Source data is available for Fig. 6b, d, f.

To assess whether split mFAPs could be used for real-time monitoring of protein–protein association, we pre-incubated equimolar BCLXL_m58 with unfused aBCLXL in excess DFHBI-1T to pre-assemble non-fluorescent BCLXL_m58–aBCLXL complex. Upon addition of equimolar m14_aBCLXL (or buffer as a negative control), the fluorescence increased as m14_aBCLXL competed with unfused aBCLXL for the BCLXL-binding cleft of BCLXL_m58, resulting in assembly of the m14–m58 complex, which activates the fluorescence of DFHBI-1T (Fig. 6c, d). The reaction evolved analogously for BFL1–aBFL1 and BCL2–aBCL2 cognate-binding partners. Different peak fluorescence fold-changes observed amongst split mFAP fusions to BCLXL–aBCLXL, BCL2–aBCL2, and BFL1–aBFL1 complexes suggest that the molecular geometry of the heterodimer interaction affects the brightness of the assembled β-barrel complex. Fluorescence excitation spectra revealed a prominent peak in fluorescence excitation wavelength at 488 nm upon combining split mFAP fragments compared to buffer negative controls (Supplementary Fig. 21).

To assess whether split mFAPs could be used for real-time monitoring of protein–protein dissociation, we pre-incubated BCL2_m58 with equimolar m14_aBFL1 in excess DFHBI-1T to pre-assemble fluorescent complexes. As the non-cognate BCL2–aBFL1 complex has a dissociation constant (Kd) of 320 ± 40 nM, the cognate BCL2–aBCL2 complex has a Kd of 0.8 ± 0.5 nM37, and aBFL1 and aBCL2 interact with the same binding cleft of BCL2, aBCL2 should outcompete aBFL1 for binding to BCL2 (Fig. 6e). Indeed, titration of aBCL2 into pre-assembled BCL2_m58–m14_aBFL1 complex in excess DFHBI-1T resulted in an aBCL2 concentration-dependent decrease in fluorescence (Fig. 6f). Fluorescence excitation spectra showed the disappearance of the fluorescence excitation peak at 488 nm wavelength consistent with chromophore unbinding and deactivation of fluorescence upon split mFAP fragment disassembly (Supplementary Fig. 21).

Circular permutation

To further explore the range of possibilities for mFAP-based sensors, we circularly permuted mFAPs (cpmFAPs) using Rosetta and the split points from the four brightest bipartite split mFAPs. The brightest cpmFAP tested, cp35-34_mFAP2a_12, has a de novo designed α-helical linker and displayed ~93% of the fluorescence intensity of mFAP2a at equimolar concentration and excess DFHBI-1T (Supplementary Fig. 22). Size-exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering showed cp35-34_mFAP2a_12 to be monomeric (Supplementary Fig. 23).

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the functionality and brightness of mFAPs can be readily extended by structure-based design and engineering. It should be emphasized, however, that the engineering of useful fluorogenic sensors based on mFAPs is still in its early days–the mFAPs were first described in September 20181. Currently, existing fluorescent protein-based sensors still have numerous advantages over mFAPs in brightness (e.g., EGFP is ~2.1-fold brighter than the mFAP10–DFHBI-1T complex) for applications involving single molecule localization microscopy15,38, fluorescence spectral diversity39, higher Ca2+ affinity7, and higher fluorescence dynamic range29, as in self-labeling chemigenetic indicators40–42. These sophisticated reporters and sensors reflect decades of work by many groups; we hope this report will stimulate exploration of de novo designed fluorescence-activating proteins. With further optimization using both selection and computational design methodologies, there is likely considerable room for improvement of brightness, photostability, pH-responsiveness, and Ca2+-responsiveness.

At this stage, the possible advantages of de novo designed mFAP sensors over existing fluorescent protein-based reporters are listed in Table 3. Two notable advantages of split mFAPs over existing split GFP-based approaches for monitoring transient protein–protein interactions are the rapid activation of fluorescence upon assembly of split mFAP fragments that enables tracking of protein–protein association, and the rapid deactivation of fluorescence upon disassembly of split mFAP fragments that enables tracking of protein–protein dissociation (similar to splitFAST but with ~2 orders of magnitude lower fragment affinities). mFAPs can activate the fluorescence of DFHBI-derived chromophores with emission spectra in different color ranges, as illustrated by the activation of DFHO5 fluorescence by mFAP3. mFAPs can be used as modular fluorogenic optical sensors for detection and quantification of other small-molecules, ions, or proteins by insertion of their respective binding peptides into the loops of mFAPs without circularly permuting the mFAPs, as in construction of Ca2+-responsive mFAPs. The cpmFAPs enable design of modular fluorogenic sensors by fusing analyte binding peptides (e.g., calmodulin and M13) directly to the juxtaposed termini or within β-sheets, as in construction of GCaMP19,29. More generally, as brighter and more photostable fluorogenic compounds are developed, the methodologies described herein should be readily applicable to creating protein-based fluorogenic optical sensors from binders to these compounds.

Table 3.

Potential advantages of de novo designed mFAP sensors over existing fluorescent protein-based reporters and sensors.

| Biophysical property | Advantage |

|---|---|

| Size | Smaller size1 than GFP-based8, DiBs15 and FAST-based7,16 reporters (Supplementary Data 1). |

| Photostability | Higher photostability over AcGFP1 in fixed mammalian cells (Fig. 2). |

| Reversible fluorescence | Spatiotemporal control over fluorescence via on-demand labeling protocols (Supplementary Fig. 4), unlike intrinsically fluorescent proteins8,50, and like DiBs15 and FAST-based7,16 reporters. |

| Ratiometric fluorescence dynamic range | Higher ratiometric fluorescence dynamic range across the physiologically relevant pH range than pHRed20,51 and pHluorin221 (Fig. 3). |

| Low-Ca2+ affinity | Lower Ca2+ affinity than existing fluorescent protein-based Ca2+ sensors such as GCaMPer34 and CatchER18 for imaging Ca2+ transients in high-Ca2+ concentration environments (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Table 2). |

| Rapid response of split mFAPs | Rapid change in fluorescence intensity upon split mFAP fragment assembly (Fig. 6d), similar to splitFAST in not requiring chromophore maturation like split GFP10,11. |

|

Reversibility of split mFAPs |

Reversible fluorescence of split mFAPs, unlike split GFP10,11, and similar to splitFAST13 but with lower fragment affinities (Fig. 6f and Supplementary Fig. 20). |

Methods

Design of brighter and pH-responsive mFAPs

A previously described1 mFAP2 computational design model was used as a template for manual selection and design of mutable residues using Rosetta23,43 macromolecular modeling software. Guided by the previously generated deep mutational scanning maps1 of stability and fluorescence of b11L5F, we constructed three mFAP2 mutational variants mFAP2(P50T,S52V), mFAP2(S52T), and mFAP2(P50T,S52V,G100D) that were expected to improve the stability of the protein while also aiding crystallization. Circular dichroism in the absence of DFHBI revealed that mFAP2(P50T,S52V), hereafter called mFAP2.1, demonstrated improved stability at pH 2.93 (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c) and higher fluorescence in the presence of DFHBI at pH 3.66 (Supplementary Fig. 1d, e) compared to mFAP2, consistent with improved binding of the phenolic form of DFHBI to the stabilized protein. A minimal site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) library (Supplementary Data 3) was generated at 15 residue positions on mFAP2.1 encoding mutations hypothesized to improve the fluorescence ratio fold-change from low to high pH, increase DFHBI affinity, and reduce conformational flexibility of the loop connecting the seventh and eighth β-strands (known as loop7) juxtaposing the DFHBI-binding pocket.

Fluorescence screening of the SDM library at pH 3.66 and pH 7.36 revealed that the most pH-responsive mutant mFAP2.1(T50P), also known as mFAP2.2, demonstrated ~1.3-fold higher fluorescence ratio fold-change from pH 3.66–7.36 than mFAP2.1 (Supplementary Fig. 1f). Subsequently, two independent combinatorial libraries were generated from mFAP2.2: one at five positions aimed at increasing loop7 rigidity (Supplementary Data 4), and another at eight positions aimed at optimizing hydrophobic packing of residues in the hydrophobic β-barrel core (Supplementary Data 5). The brightest variant from the first library mFAP2.2(A100E,G101N,N102D,T104H), hereafter known as mFAP2.3, and the brightest variant of the second library mFAP2.2(M27W,V39I,V57A,F93W), hereafter known as mFAP2.4, showed an increase in fluorescence intensity from the phenolate form of DFHBI of ~1.1-fold and ~3.4-fold from mFAP2.2 at pH 7.36, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1g,h). The mutations producing mFAP2.3 and mFAP2.4 were combined into one scaffold generating mFAP2.5. A single mutation (V67I) was identified by screening a combinatorial library (Supplementary Data 6) of mutations at 7 positions aimed at packing more methyl groups into the hydrophobic β-barrel core of mFAP2.5. The protein (Fig. 1a), referred to as mFAP2b (“b” for bright), is ~1.2-fold brighter than mFAP2.5 and ~1.3-fold brighter than mFAP2.4 at neutral pH (Supplementary Fig. 1i). It was demonstrated that mFAP2b had ~10-fold weaker affinity for DFHBI than the initial mFAP2 design.

Another combinatorial library (Supplementary Data 7) was generated at five positions of mFAP2b aimed at increasing affinity for the deprotonated state of DFHBI without compromising fluorescence intensity by packing both aromatic and aliphatic residues in the hydrophobic β-barrel core of mFAP2b. Screening for fluorescence intensity of the phenolate state of DFHBI using a relatively low-DFHBI concentration (555 nM) resulted in mFAP2b(V13A,M15F), known as mFAP2a (“a” for affinity). mFAP2a displayed ~1.3-fold brighter fluorescence than mFAP2b at low-DFHBI concentration (Supplementary Fig. 1j). Aiming to further improve packing of methyl groups in the hydrophobic β-barrel core to increase the fluorescence intensity of the phenolate state of DFHBI at neutral pH while accommodating the interesting geometry of the Y71W mutation, a combinatorial library (Supplementary Data 8) was constructed at three positions of mFAP2a, resulting in designs mFAP3 through mFAP8 (Supplementary Table 1). However, these mutants were dimmer and demonstrated lower expression levels than mFAP2b or mFAP2a (Supplementary Table 1), although mFAP3 showed to be the brightest DFHO-binding variant (mFAP3 with 10.0 µM DFHO is ~10-fold dimmer than mFAP2b with 10.0 µM DFHBI). In order to increase the fluorescence brightness of mFAP2a with DFHBI-1T, a final combinatorial library was constructed at six positions of mFAP2a (Supplementary Data 9) by mutating aliphatic and aromatic residues in the chromophore-binding pocket of mFAP2a juxtaposing DFHBI-1T in computational models. Screening for fluorescence intensity of DFHBI-1T using a low-DFHBI-1T concentration (250 nM) resulted in mFAP2a(W27I,W93F), also known as mFAP10. An additional 14 designs (including mFAP_pH) were constructed by combining loop7 and hydrophobic β-barrel core mutations from the variants demonstrating the highest fluorescence intensity of the deprotonated state of DFHBI from the mFAP2.2 loop7 combinatorial library (Supplementary Data 4) and mFAP2.2 hydrophobic β-barrel core combinatorial library (Supplementary Data 5 and Supplementary Fig. 1g, h).

Design of chromophore-selective mFAPs

Computational modeling of DFHBI (Fig. 1b) into the binding pocket of mFAP2b (Fig. 1f) and mFAP2a (Fig. 1h) using Rosetta23,43 macromolecular modeling software showed that the mutations V13A and M15F resulted in a void in the binding pocket of mFAP2a. It was hypothesized that a commercially available structural derivative of the DFHBI chromophore with a trifluoromethyl group, DFHBI-1T4 (Fig. 1c), could pack into the void without causing steric clashes. Computational modeling of DFHBI-1T in the pocket of mFAP2a (Fig. 1i) demonstrated good protein–chromophore shape complementarity, whereas DFHBI-1T modeled into the mFAP2b pocket (Fig. 1g) resulted in steric clashes. Studying the fluorescence of mFAP2a and mFAP2b in the presence of DFHBI-1T experimentally validated this (Fig. 1d, e). Relative fluorescence intensities and binding affinities of DFHBI, DFHBI-1T, and DFHO for selected mFAP variants were then measured at neutral pH (Supplementary Table 1). The fluorescence intensity of mFAP2a with DFHBI-1T was improved upon screening the “IN2” combinatorial library, resulting in mFAP10.

Design of extended loop library

β-hairpin loop fragments from the RCSB Protein Data Bank [www.rcsb.org] were used to manually curate custom β-barrel loop fragment databases. RosettaRemodel44 was used to fix the β-hairpin loop termini to loops 1, 3, 5, and 7 of the de novo β-barrel scaffolds b11 and b321, picking 3-mer and 9-mer fragments from the custom β-barrel loop fragment databases, from which 2226 designs with successfully closed loops were generated. Loop coordinates were extracted as .pdb files and used as templates to generate Rosetta blueprint files specifying amino acid type, secondary structure, and ABEGO45 type of loops to be rebuilt onto loops 1, 3, 5, and 7 of a computational model of mFAP2b, resulting in 8904 Rosetta blueprint files. For each blueprint file, a RosettaScripts22,23 XML script (Supplementary Note 2) was used to graft the loop onto mFAP2b with a centroid energy function followed by Monte Carlo46 sampling of protein side-chain repacking and protein side-chain and backbone minimization steps in a full-atom Cartesian coordinate energy function47. Seven-thousand seven-hundred forty-eight resulting designs were filtered for the following computational protein design metrics (as scored from the XML script described in Supplementary Note 2): geometry = 1; total_score_res ≤ −3.72714; holes ≤ −1.2729; pstat ≥ 0.755044; buns_sc_heavy ≤ 2; buns_bb_heavy ≤ 2; interfE ≤ −38.375; SC ≥ 0.734076; p_aa_pp ≤ −40.8947; and omega ≤ 2.8757. Only 59 designs with extended loops built onto loops 1, 3 and 7 of mFAP2b passed the filter criteria for experimental testing (Supplementary Data 11).

Design of Ca2+-responsive mFAPs

The mFAP2b loop7 sequence and the five extended loop7 sequences shown to confer fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 6) were sampled as linkers for grafting the sequence of one EF-hand motif from Protein Data Bank (PDB) accession code 1NKF24 onto loop7 of mFAP2b. An in-house script (Supplementary Note 3) was written to prune the experimentally validated extended loop7 sequences one residue at a time keeping up to four residues on the N-terminal and C-terminal linkers relative to the grafted EF-hand motif, optionally adding an additional glycine residue on the N-terminal linker and optionally adding an additional glycine or proline residue on the C-terminal linker. This combinatorial library (Supplementary Data 12) had a theoretical diversity of 1140 linkers. The linkers resulting in positively and negatively allosteric Ca2+-responsive mFAPs containing one EF-hand motif were combinatorially sampled to act as linkers for grafting two EF-hand motifs from PDB accession code 1FW425 onto loop7 of mFAP2b, where the N-terminal helix of PDB accession code 1FW4 was truncated up to homologous residues on successfully grafted single EF-hand motif designs. This combinatorial library (Supplementary Data 13) had a theoretical diversity of 385 linkers. The linkers resulting in negatively allosteric Ca2+-responsive mFAPs containing two EF-hand motifs were combinatorially sampled to act as linkers for grafting four EF-hand motifs from PDB accession code 1PRW26 onto loop7 of mFAP2b, where the N-terminal helix of PDB accession code 1PRW was truncated up to homologous residues on successfully grafted single EF-hand motif designs. This combinatorial library (Supplementary Data 14) had a theoretical diversity of 25 linkers.

Design of split mFAPs and cpmFAPs

Split mFAPs were designed by manually inspecting the single-chain mFAP2a computational design model. In designing split mFAP fusions to BCL2 family heterodimers, linker compositions and lengths were chosen by manually inspecting the split mFAP2a computational design models and available crystal structures (PDB accession codes 5JSN and 5JSB). Split mFAP2a fragments were fused to maltose-binding protein, BCL2, aBCL2, BFL1, aBFL1, BCLXL, and aBCLXL after cysteine residues unlikely to be participating in disulfide bonds were mutated to serine or alanine residues (Supplementary Data 1).

Circularly permuted mFAP2a and mFAP2b were generated from mFAP2a and mFAP2b computational models using Rosetta23 and custom scripts in which N- and C-termini (“split points”) were selected at mFAP loop2, loop4, loop6, and loop7 locations, and the two N-terminal and two C-terminal residues of cpmFAP scaffolds were re-designed compared to their respective residue types in mFAP2a (Supplementary Note 4). De novo structured and unstructured linkers covalently fusing the canonical mFAP termini were designed using RosettaScripts22,23, and 4000 resulting designs were filtered and sorted on design metrics. The top 12 designs were chosen for experimental testing after 3 circularly permuted mFAP2b variants were mutated to circularly permuted mFAP2a variants using the (V13A, M15F) double point mutation (in canonical mFAP residue numbering) (Supplementary Fig. 22a, b). In the subsequent round of cpmFAP designs, the de novo designed linker sequences from cp35-34_mFAP2a_12, cp35-34_mFAP2a_10, cp35-34_mFAP2a_08, and cp35-34_mFAP2a_11 were each sampled with the four split points described above, and the two N-terminal and two C-terminal residues in the cpmFAP were reverted back to their respective residue types in mFAP2a (Supplementary Fig. 22d and Supplementary Data 1).

Synthetic DNA construction

For combinatorial libraries, oligonucleotides with degenerate codons encoding desired mFAP sequences were designed using SwiftLib48. Overlapping forward and reverse oligonucleotides with degenerate and/or non-degenerate codons spanning the mFAP gene of interest were synthesized (IDT DNA). Oligonucleotides spanning identical gene regions were pooled at equimolar ratios relative to the theoretical amino acid diversity encoded by each gene region. Full-length genes were constructed using assembly polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with Phusion polymerase (NEB). For the extended loop library, the loop1, loop3, and loop7 libraries were assembled separately, and the concentrations of assembly PCR products consisting of full-length genes were quantified on a NanoDrop 8000 (Thermo Scientific) and the three libraries pooled in quantities proportional to the theoretical library diversities of assembly PCR products. Successfully assembled full-length genes, as well as synthetic gBlock (IDT DNA) oligonucleotides encoding full-length protein sequences, with 5′ and 3′ flanking vector backbone sequences were sub-cloned into the pET15b vector (Novagen) or the pcDNA5/FRT/TO vector (ThermoFisher Scientific) using Gibson assembly. The mFAP2.2 loop7 combinatorial library was constructed via Gibson assembly of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE)-purified duplex oligonucleotides into pET15b-mFAP2.2 linear vector DNA. The full-length genes encoding pHRed20 and pHluorin221 were synthesized and cloned into the pET29b(+) vector (IDT DNA). Cloned DNA constructs were transformed into Lemo21(DE3) competent E. coli (NEB) and plated onto lysogeny broth (LB)-agar plates supplemented with 50.0 μg mL−1 carbenicillin or 50.0–100 μg mL−1 kanamycin.

Screening libraries

The number of E. coli colonies picked for functional screening was approximately 4-fold the theoretical diversity of each library. E. coli colonies were inoculated into 1.00 mL of LB media supplemented with 50.0 μg mL−1 carbenicillin in Nunc 2.0 mL DeepWell 96-well plates (Thermo Scientific), and were grown at 37 °C shaking at 1200 rpm overnight. Twenty-five microliters of these cultures were inoculated into 1.00 mL of fresh LB media supplemented with 50.0 μg mL−1 carbenicillin, grown at 37 °C and 1200 rpm for 3–4 h, then 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) final concentration was added to each well, and protein expression induced for 4 h at 37 °C shaking at 1200 rpm. Cells were pelleted at 2272 × g for 2–5 min and pellets were resuspended in 50.0 μL of lysis buffer #1 (25.0 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 20.0 mM imidazole, pH 8.00) supplemented with 1.00 mg mL−1 PMSF, a small amount of deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I) from bovine pancreas (Sigma Aldrich), and 2.00 mg mL−1 lysozyme from chicken egg white (Sigma) for lysis. Crude lysates were vigorously shaken at 25–37 °C for 12–48 h, then clarified by centrifugation. Clarified lysates were assayed on a Synergy Neo2 hybrid multi-mode reader (BioTek) in 96-well non-binding surface microplates (Corning 3650) with Gen5 (version 3.03.14) software.

For each clone encoding a β-barrel core variant, loop7 variant, or extended loop variant, 15.0 μL of clarified lysate was combined with 185 μL of Na2HPO4-citrate (pH 7.36 or pH 3.66) buffer supplemented with 150 mM NaCl and either 1.08 μM DFHBI (Lucerna), 555 nM DFHBI (Lucerna), or 250 nM DFHBI-1T (Lucerna). Na2HPO4-citrate buffer was made from 200 mM Na2HPO4 and 100 mM citrate stock solutions, and final pH was adjusted using hydrochloric acid (HCl) or sodium hydroxide (NaOH). DFHBI and DFHBI-1T stock solutions were 2.00 mM in 23.8 mM Tris (pH 8.00), 95.0 mM NaCl, and 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Clones that demonstrated fluorescence were Sanger sequenced via colony PCR of overnight cultures, and the brightest designs or designs with highest fluorescence fold-change across pH 7.36–3.66 were further characterized with large-scale protein purification49.

For each clone encoding one or more EF-hand motifs grafted onto β-barrel loop7, 15.0 μL of lysate was combined with 185 μL of either 2.00 mM CaCl2 (Sigma Aldrich), 25.0 mM Tris (pH 8.00), 100 mM NaCl, 1.08 μM DFHBI or 2.00 mM EGTA (Sigma Aldrich), 25.0 mM Tris (pH 8.00), 100 mM NaCl, 1.08 μM DFHBI. Clones that demonstrated greater than an approximately twofold change in fluorescence intensity between CaCl2 and EGTA conditions were Sanger sequenced, and the designs demonstrating the highest fold-change in fluorescence intensity between CaCl2 and EGTA conditions were further characterized with large-scale protein purification49.

Fluorescence intensity assays

To measure fluorescence intensities of the phenolate form of chromophores, fluorescence was measured on a Synergy Neo2 hybrid multi-mode reader (BioTek) in flat bottom, black polystyrene, non-binding surface 96-well microplates (Corning 3650). Fluorescence intensity was measured in triplicate by exciting at λex = 484 nm and measuring fluorescence emission at λem = 505 nm (or λem = 511 nm for clones harboring the W27 mutation) (Supplementary Fig. 1g, h). The W27 mutation redshifts the peak emission wavelength from λem = ~505 nm to λem = ~511 nm, presumably due to the W27 indole ring donating a hydrogen bond to the imidazolinone moiety of the deprotonated state of DFHBI, which stabilizes the chromophore conjugated π–electron system in the excited state causing the redshift in emission50. Fifteen microliters of small-scale purified protein49 was combined with 185 μL of Na2HPO4-citrate (pH 7.36) buffer supplemented with 150 mM NaCl and 108 nM DFHBI for a final concentration of 100 nM DFHBI. In measuring the excitation spectra from λem = 525 nm of each clone in triplicate (Supplementary Fig. 1i), 30.0 μL of large-scale purified protein49 was combined with 170 μL of 25.0 mM Tris (pH 8.00) supplemented with 100 mM NaCl and 914 nM DFHBI for a final concentration of 7.77 μM protein and 777 nM DFHBI. In measuring the fluorescence intensity at λex = 484 nm and λem = 509 nm of each clone in triplicate (Supplementary Fig. 1j), 30.0 μL of large-scale purified protein49 was combined with 170 μL of 25.0 mM Tris (pH 8.00) supplemented with 100 mM NaCl and 653 nM DFHBI for a final concentration of 5.55 μM protein and 555 nM DFHBI. In measuring fluorescence intensity at λex = 468 nm and λem = 530 nm of each clone in technical triplicate (Supplementary Fig. 1k), 24.0 μL of 35.4 µM large-scale purified protein49 was combined with 1.00 μL of 1.25 µM DFHBI or 1.00 μL of 1.25 µM DFHBI-1T (Lucerna) (from 2 mM chromophore stock solutions dissolved in 0.5% DMSO and 99.5% high-salt Tev cleavage buffer [25.0 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.00]) for final concentrations of 34.0 μM protein and 50.0 nM chromophore. The mFAP9–DFHBI complex had ~1.1-fold the fluorescence intensity of the mFAP10–DFHBI complex, and the mFAP9–DFHBI-1T complex had ~0.75-fold the fluorescence intensity of the mFAP10–DFHBI-1T complex (Supplementary Fig. 1k). In collecting fluorescence emission spectra by exciting fluorescence at λex = 484 nm and collecting fluorescence emission at λem = 495–650 nm (Supplementary Fig. 6b), and in measuring fluorescence endpoints in techincal triplicate at unique peak excitation and emission wavelengths (Supplementary Fig. 6c), 195 μL of large-scale purified protein49 was combined with 5.00 μL of 25 mM Tris (pH 8.00) supplemented with 100 mM NaCl and 40.0 μM DFHBI for a final concentration of 10.0 μM protein and 1.00 μM DFHBI.

In measuring fluorescence intensity of small-scale purified proteins49 (Supplementary Table 1), wells were excited at λex = 488 nm for DFHBI and DFHBI-1T and λex = 505 nm for DFHO, and fluorescence emission measured at λem = 510 nm for DFHBI and DFHBI-1T and λem = 545 nm for DFHO. Fluorescence endpoints were measured using either 25.0 μL or 50.0 μL of small-scale purified protein in either 175 μL or 150 μL, respectively, of Na2HPO4-citrate (pH 7.36) buffer supplemented with 150 mM NaCl and either 100 nM or 10.0 μM of either DFHBI (Lucerna), DFHBI-1T (Lucerna) or DFHO (Lucerna) (from 20.0 mM chromophore stock solutions in 100% DMSO), for 200 μL final volumes per well.

To measure the fluorescence intensities of circularly permuted mFAP2a variants (Supplementary Fig. 22b, d), fluorescence endpoints were measured on a Synergy Neo2 hybrid multi-mode reader (BioTek) in flat bottom, black polystyrene, non-binding surface 96-well microplates (Corning 3650) or half-area microplates (Corning 3686). Fluorescence endpoints were measured in technical triplicate by exciting at λex = 488 nm and measuring fluorescence emission at λem = 510 nm (Supplementary Fig. 22b), or exciting at λex = 468 nm and measuring fluorescence emission at λem = 530 nm (Supplementary Fig. 22d). Ninety microliters of 55.6 µM large-scale purified protein49 in high-salt Tev cleavage buffer was combined with 10.0 µL of 5.00 µM DFHBI-1T in high-salt Tev cleavage buffer for final concentrations of 50.0 µM protein and 500 nM DFHBI-1T in 100 µL final volumes (Supplementary Fig. 22b), or 48.0 µL of 41.7 µM large-scale purified protein49 in high-salt Tev cleavage buffer was combined with 2.00 µL of 1.25 µM DFHBI-1T in high-salt Tev cleavage buffer for final concentrations of 40.0 µM protein and 50.0 nM DFHBI-1T in 50.0 µL final volumes (Supplementary Fig. 22d).

Densitometry

In quantifying relative protein expression levels in E. coli (Supplementary Table 1), 5.00 μL of small-scale purified proteins49 were combined with 5.00 μL of 2x Laemmli buffer, denatured at 99 °C for 10 min, and 5.00 μL of each sample run on Any kD Mini-PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free Precast Gels (Bio-Rad) in Tris-glycine buffer alongside 5.00 μL of Precision Plus Protein Unstained Protein Standard (Bio-Rad). Gels were stained using an eStain L1 Protein Staining System (GenScript) and imaged using a Molecular Imager ChemiDoc XRS+ (Bio-Rad). Relative densitometry was analyzed in Image Lab Software Version 6.0.1 build 34 Standard Edition (Bio-Rad) referenced to the 15 kDa protein ladder band.

pH-dependent fluorescence assays

pH-dependent fluorescence was measured on a Synergy Neo2 hybrid multi-mode reader in flat bottom, black polystyrene, non-binding surface 96-well microplates (Corning 3650). In measuring the pH-sensitivity of β-barrel variants in technical triplicate (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b), 20.0 μL of large-scale purified protein49 was combined with 180 μL of Na2HPO4-citrate (pH 7.34 or 3.61) supplemented with 150 mM NaCl and 278 nM DFHBI for final concentrations of 2.50 μM protein and 250 nM DFHBI. Buffer wells for background subtraction were prepared identically except using 20.0 μL of high-salt Tev cleavage buffer instead of purified protein. Wells were excited at λex = 387 nm or λex = 484 nm and fluorescence emission measured at λem = 501 nm or λem = 505 nm, respectively. Following background subtraction from the mean endpoint fluorescence of buffer controls, the fluorescence ratio fold-change from pH 3.61–7.34 was calculated as:

| 1 |

where is the endpoint fluorescence measurement at the subscripted pH value and superscripted fluorescence excitation (λex) and fluorescence emission (λem) wavelengths.

In measuring pH-sensitivity of β-barrel variants (Supplementary Fig. 1f) in technical triplicate, 140 μL of Na2HPO4-citrate (pH 7.36 or 3.66) supplemented with 150 mM NaCl and 1.43 μM DFHBI was combined with 10.0 μL of small-scale purified protein49 for a final concentration of 1.33 μM DFHBI. Fluorescence endpoints were measured by exciting at λex = 387 nm or λex = 483 nm and measuring fluorescence emission at λem = 501 nm or λem = 504 nm, respectively. Without background subtraction, the fluorescence ratio fold-change from pH 3.66–7.36 was calculated as:

| 2 |

where is the mean of three technical replicates of endpoint fluorescence measurements at the subscripted pH value and superscripted fluorescence excitation (λex) and fluorescence emission (λem) wavelengths.

In measuring pH-dependent fluorescence (Fig. 3d–i), Na2HPO4-citrate buffer supplemented with 150 mM NaCl at unique pH values were produced via mixing various volumes of 100 mM citric acid (Sigma Aldrich), 200 mM Na2HPO4 (Sigma Aldrich), and 2.00 M NaCl, and final pHs quantified via an Accumet AB15 Basic pH meter (Fisher Scientific). pHRed and pHluorin2 were produced via large-scale protein purification, 6xHis-tag removal and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) purification, and mFAP_pH and mFAP2b were produced via large-scale protein purification and SEC purification49. pH-dependent fluorescence was measured at 500 nM final protein concentration for mFAP2b, mFAP_pH and pHRed, and 170 nM final concentration for pHluorin2, at each pH in technical triplicate in 200 μL final volumes per well. To prevent pH fluctuations upon addition of protein and DFHBI, 195 μL of Na2HPO4-citrate buffers supplemented with 150 mM NaCl at each pH was aliquoted per well, 4.00 μL of purified protein was aliquoted per well, and 1.00 μL of 1.00 mM DFHBI (in 2.5% DMSO and 97.5% high-salt Tev cleavage buffer) was added to wells containing mFAP_pH, whereas 1.00 μL of chromophore buffer (2.5% DMSO and 97.5% high-salt Tev cleavage buffer) was added to wells containing pHRed or pHluorin2. Blank wells for background subtraction for mFAP2b, mFAP_pH, pHRed and pHluorin2 were prepared identically, respectively, except adding 4.00 μL of high-salt Tev cleavage buffer instead of purified protein. In measuring fluorescence excitation spectra at each pH (Fig. 3d), excitation wavelengths were set to the range λex = 300–530 nm and fluorescence emission measured at λem = 562 nm. In measuring pH-dependent fluorescence excitation spectra at pH 3.76 and pH 7.34 (Fig. 3f, g), excitation spectra were measured using excitation wavelengths in the range λex = 300–540 nm and emission wavelength λem = 592 nm.

In measuring fluorescence emission spectra at two pH values (Fig. 3e), emission spectra for the blueshifted excitation peak was measured at pH 3.63 using excitation wavelength λex = 379 nm and emission wavelengths in the range λem = 460–700 nm, and emission spectra for the redshifted excitation peak was measured at pH 8.38 using excitation wavelength λex = 430 nm and emission wavelengths in the range λem = 460–700 nm. In measuring fluorescence from both the blueshifted and redshifted excitation peaks (Fig. 3h, i), for mFAP_pH the fluorescence excitation wavelengths were λex = 379 nm and λex = 483 nm and fluorescence emission wavelengths were λem = 498 nm and λem = 503 nm, respectively, whereas for pHRed the fluorescence excitation wavelengths were λex = 440 nm and λex = 575 nm and fluorescence emission wavelengths were both λem = 635 nm, and for pHluorin2 the fluorescence excitation wavelengths were λex = 405 nm and λex = 485 nm and fluorescence emission wavelengths were both λem = 535 nm. In Fig. 3i, for the mFAP_pH–DFHBI complex, pHRed, and pHluorin2 the ratiometric fluorescence (Fratio) is calculated from the background-subtracted, unnormalized fluorescence measurements using fluorescence emission from the redshifted excitation peak () as the numerator and fluorescence emission from the blueshifted excitation peak () as the denominator:

| 3 |

In Fig. 3i, mean ratiometric fluorescence values are fit to continuous logistic functions with the formula for the mFAP_pH–DFHBI complex, for pHRed, and for pHluorin2 using non-linear least squares fitting, which serve as continuous calibration curves for real-time quantification of pH51.

In measuring the protonated (phenolic) and deprotonated (phenolate) DFHBI affinities with mFAP_pH (Supplementary Fig. 5c), fluorescence endpoints were measured on a Synergy Neo2 hybrid multi-mode reader (BioTek) in flat bottom, black polystyrene, non-binding surface 96-well microplates (Corning 3650). mFAP_pH was produced by large-scale protein purification49 and aliquoted to 200 μL final volumes at 500 nM final concentration in seven serial dilutions ( dilution factor) of DFHBI starting from 10.0 μM DFHBI final concentration, including an eighth condition without chromophore, in Na2HPO4-citrate buffer supplemented with 143 mM NaCl final concentration at either pH 3.61 or pH 7.34. For pH 3.61 fluorescence was excited at λex = 379 nm and fluorescence emission measured at λem = 498 nm, and for pH 7.34 fluorescence was excited at λex = 483 nm and fluorescence emission measured at λem = 503 nm. At each pH, background fluorescence endpoints of wells with identical chromophore concentrations but purified protein replaced with an identical volume of buffer were measured, and fluorescence endpoints subtracted from those measured with protein. Background-subtracted data were normalized from 0 to 1 and fit to a single-binding site isotherm function using non-linear least squares fitting to obtain the reported Kd values, which were less than the protein concentrations tested.

Chromophore titrations

Fluorescence endpoints were measured on a Synergy Neo2 hybrid multi-mode reader (BioTek) in flat bottom, black polystyrene, non-binding surface 96-well microplates (Corning 3650). In measuring chromophore-binding affinities (Fig. 1d, e), mFAP2, mFAP2a, and mFAP2b, and mFAP10 were produced by large-scale protein purification and SEC purification49. Proteins were aliquoted in eight technical replicates in 200 μL final volumes to 20.0 nM final concentration in ten serial dilutions ( dilution factor) of DFHBI starting from 31.6 μM DFHBI or 31.6 μM DFHBI-1T final concentrations, including an eleventh condition without chromophore. Fluorescence was excited at λex = 468 nm and fluorescence emission measured at λem = 530 nm. Background fluorescence endpoints of wells with identical chromophore concentrations but purified protein replaced with an identical volume of high-salt Tev cleavage buffer were measured, and fluorescence endpoints subtracted from those measured with protein. Background-subtracted data were averaged and the means normalized from 0 to 1 and fit to a single-binding site isotherm function using non-linear least squares fitting to obtain a fitted Kd value (Table 1), and the fit scaled to the maximum mean value (Fig. 1d, e).

Chromophore affinities (Supplementary Table 1) were obtained by producing proteins via large-scale protein purification (some variants further purified by SEC)49 and preparing proteins at 25.0 μL final volumes in flat bottom, black polystyrene, non-binding surface 96-well half-area microplates (Corning 3686). Proteins were aliquoted to 500 nM final concentrations in high-salt Tev cleavage buffer (mFAP2.2.5 was prepared at 386 nM, and mFAP2a and mFAP3 were prepared at 50.0 nM) in eleven serial dilutions ( dilution factor) from 1.00 mM DFHBI, 1.00 mM DFHBI-1T, or 1.00 mM DFHO, including a twelfth condition without chromophore. Fluorescence endpoints were measured on a Synergy Neo2 hybrid multi-mode reader (BioTek) with excitation and emission wavelengths set differently between protein variants to achieve maximal fluorescence intensity. Background fluorescence endpoints of wells with identical chromophore concentrations but purified protein replaced with an identical volume of high-salt Tev cleavage buffer were measured, and fluorescence endpoints measured with identical instrument settings subtracted from those measured with protein prior to normalization.

Ca2+-responsive mFAP DFHBI titrations

In measuring Ca2+-dependent DFHBI affinity of Ca2+-responsive mFAPs on a Synergy Neo2 hybrid multi-mode reader (Fig. 4a–c and Supplementary Figs. 10a, b, d, e, g, h, 11a, b, d, e, g, h, 12a, b, d, e, g, h, 16a), large-scale purified proteins49 were aliquoted to a final concentration of 500 nM in either 450 mM CaCl2 (Sigma Aldrich) (prepared in high-salt Tev cleavage buffer) or high-salt Tev cleavage buffer, along with ten serial dilutions ( dilution factor) of DFHBI starting from 316 μM DFHBI including an eleventh condition without chromophore. Final volumes were 25.0 μL in flat bottom, black polystyrene, non-binding surface 96-well half-area microplates (Corning 3686) or 200 μL in flat bottom, black polystyrene, non-binding surface 96-well microplates (Corning 3650). Fluorescence endpoints were measured using excitation wavelength λex = 488 nm and emission wavelength λem = 510 nm. Background fluorescence endpoints of wells with identical chromophore concentrations lacking protein (substituted for equivalent volumes of high-salt Tev cleavage buffer) were measured and subtracted from protein measurements prior to normalization.

For DFHBI titrations of EF4n_mFAP2a and EF4n_mFAP2b (Supplementary Fig. 13a, b), a small amount of Chelex 100 sodium form (Sigma Aldrich) was added to purified protein (produced by large-scale protein purification and SEC purification49) and nutated at 4 °C overnight. High-salt Tev cleavage buffer with a small amount of Chelex 100 was prepared and mixed at room temperature overnight, and a 2.00 mM DFHBI stock solution (in 5% DMSO and 95% high-salt Tev cleavage buffer) with a small amount of Chelex 100 was prepared and nutated overnight at 4 °C. Proteins were aliquoted to a final concentration of 5.00 μM in either 500 μM CaCl2 (Sigma Aldrich) (prepared in high-salt Tev cleavage buffer) or 500 μM EGTA (Sigma Aldrich) (prepared in high-salt Tev cleavage buffer), along with ten serial dilutions ( dilution factor) of DFHBI starting from 316 μM DFHBI (using Chelex 100 pre-treated DFHBI stock solution and high-salt Tev cleavage buffer), including an eleventh condition without chromophore. Final volumes were 25.0 μL in flat bottom, black polystyrene, non-binding surface 96-well half-area microplates (Corning 3686). Fluorescence endpoints were measured using excitation wavelength λex = 488 nm and emission wavelength λem = 510 nm for EF4n_mFAP2b, and excitation wavelength λex = 478 nm and emission wavelength λem = 520 nm for EF4n_mFAP2a. Background fluorescence endpoints of wells with identical chromophore concentrations lacking protein (substituted for equivalent volumes of Chelex 100 pre-treated high-salt Tev cleavage buffer) were measured and subtracted from protein measurements prior to normalization.

Ca2+-responsive mFAP Ca2+ titrations

In measuring Ca2+ affinity of mFAPs on a Synergy Neo2 hybrid multi-mode reader (Fig. 4d, e, f and Supplementary Figs. 10c, f, i, 11c, f, i, 13c, f, i, 16b), large-scale purified proteins49 were aliquoted in technical triplicate to a final concentration of 500 nM with 5.00 μM DFHBI in eleven serial dilutions ( dilution factor) of CaCl2 (Sigma Aldrich) starting from either 900 mM or 90.0 mM CaCl2 (diluted using high-salt Tev cleavage buffer) including a twelfth condition without CaCl2. Final volumes were 200 μL in flat bottom, black polystyrene, non-binding surface 96-well microplates (Corning 3650). Fluorescence endpoints were measured using excitation wavelength λex = 484 nm and emission wavelength λem = 508 nm. Background fluorescence endpoints of wells with identical chromophore and CaCl2 concentrations lacking protein (substituted for equivalent volumes of high-salt Tev cleavage buffer) were measured in technical triplicate, averaged per condition, and subtracted from protein measurement averages of the same conditions.

For Ca2+ titrations of EF4n_mFAP2a and EF4n_mFAP2b (Supplementary Fig. 13c), a small amount of Chelex 100 sodium form (Sigma Aldrich) was added to purified protein (produced by large-scale protein purification and SEC purification49) and nutated at 4 °C overnight. EF4n_mFAP2a was aliquoted in technical triplicate to a final concentration of 8.00 μM with 80.0 μM DFHBI and EF4n_mFAP2b was aliquoted in technical triplicate to a final concentration of 6.25 μM with 43.4 μM DFHBI, in eleven serial dilutions ( dilution factor) of CaCl2 starting from 9.00 mM or 4.00 mM CaCl2 (diluted using high-salt Tev cleavage buffer pre-treated with Chelex 100) including a twelfth condition without CaCl2. Final volumes were 25.0 μL in flat bottom, black polystyrene, non-binding surface 96-well half-area microplates (Corning 3686) or 200 μL in flat bottom, black polystyrene, non-binding surface 96-well microplates (Corning 3650). Fluorescence endpoints were measured for EF4n_mFAP2a using excitation wavelength λex = 478 nm and emission wavelength λem = 520 nm, and for EF4n_mFAP2b using excitation wavelength λex = 484 nm and emission wavelength λem = 508 nm. Background fluorescence endpoints of wells with identical chromophore and CaCl2 concentrations lacking protein (substituted for equivalent volumes of high-salt Tev cleavage buffer) were measured in technical triplicate, averaged per condition, and subtracted from protein measurement averages of the same conditions. For non-linear least squares fitting to obtain Kd values, means were fit to a single-binding site isotherm function where Ca2+-binding sites were modeled independently with a Hill coefficient of 1.

Ca2+-responsive mFAP fluorescence spectra