Abstract

This review presents an overview of cardiac A2A-adenosine receptors The localization of A2A-AR in the various cell types that encompass the heart and the role they play in force regulation in various mammalian species are depicted. The putative signal transduction systems of A2A-AR in cells in the living heart, as well as the known interactions of A2A-AR with membrane-bound receptors, will be addressed. The possible role that the receptors play in some relevant cardiac pathologies, such as persistent or transient ischemia, hypoxia, sepsis, hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and arrhythmias, will be reviewed. Moreover, the cardiac utility of A2A-AR as therapeutic targets for agonistic and antagonistic drugs will be discussed. Gaps in our knowledge about the cardiac function of A2A-AR and future research needs will be identified and formulated.

Keywords: A2A-adenosine receptor, contractility, ischemia, reperfusion, arrhythmias

Introduction

There have been many reviews on adenosine receptors (AR), specifically A2A-AR (Fredholm et al., 2001; Haskó and Pacher 2008; Fredholmet al., 2011; McIntosh and Lasley, 2012; Chen et al., 2013; Headrick et al., 2013; Burnstock and Boeynaems, 2014; Burnstock, 2015; Boros et al., 2016). However, there are few reviews on cardiac A2A-AR. The present work attempts to close this gap in the literature.

In their pioneering work on the pharmacology of adenosine in the heart, Drury and Szent-Györgyi (1929) showed that it can reduce the force of contraction and induce arrhythmias, namely bradycardia. Adenosine alone has a negative chronotropic effect on the sinus node, a negative dromotropic effect on the atrioventricular (AV) node, and a negative inotropic effect on atrial tissue; after β-adrenergic stimulation, adenosine has a negative inotropic effect on the ventricular tissue of most mammalian hearts (Shryock and Belardinelli, 1997). Receptors that are activated by adenosine are called P1 receptors and are differentiated from P2 receptors, which are preferentially activated by adenosine triphosphate (ATP); this agonist selectivity can be lost if high concentrations of ATP or adenosine are used.

The focus of the present review is the P1 receptors. There are four different receptors: A1, A2A, A2B, and A3. In general, A1-AR and A3-AR inhibit adenylyl cyclase, while A2A-AR and A2B-AR stimulate adenylyl cyclase activities in the heart (Olsson and Pearson, 1990).

Receptor Structure

The A2A-AR gene was first cloned from mice and rats (Libert et al., 1989; Chern et al., 1992). Researchers have generated and studied at least three strains of knockout (KO) mice and two lines of mice with a constitutive cardiac overexpression of A2A-AR, as well as one line of mice with an inducible cardiac overexpression of A2A-AR (Ledent et al., 1997; Chen et al., 1999; Xiao et al., 2006; Boknik et al., 2018, Boknik et al., 2019; see Table 1). The A2A-AR gene contains two exons (Fredholm et al., 2000) and is located on human chromosome 22 (MacCollin et al., 1994). The gene can be alternatively spliced, which could explain the different responses to adenosine exhibited by patients (Haskó and Pacher 2008; Soma et al., 1998). The A2A-AR belong to the class of G protein-coupled heptahelical receptors (Figure 1; Fredholm et al., 2001, Fredholm et al., 2011). Mutations to dissect the ligand binding sites and the sequences involved in the signal transduction of the receptor have been extensively studied and reviewed (Fredholm et al., 2001, Fredholm et al., 2011). Polymorphism are known (Deckert et al., 1996; Zhai et al., 2015; Nardin et al., 2018). The human receptor contains 410 amino acids, while the mouse receptor has 409 amino acids; the apparent molecular weight is 45–55 kDa on gel electrophoresis (Fredholm et al., 2001; McIntosh and Lasley 2012). The homology of mouse and human A2A-AR is about 90% (Fredholm et al., 2001).

TABLE 1.

A2A-adenosine receptor knock out (KO) and cardiac overexpression mice.

| Type | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| KO | Ledent et al. (1997) | ||

| KO | Chen et al. (1999) | ||

| KO | Xiao et al. (2006) | ||

| Flox | Reutershan et al. (2007), Shen et al. (2008), Bastia et al. (2005) | ||

| Overexpression | Constitutive | Cardiac specific | Boknik et al. (2018), Boknik et al. (2019), Chan et al. (2008) |

| Overexpression | Inducible | Cardiac specific | Hamad et al. (2010) |

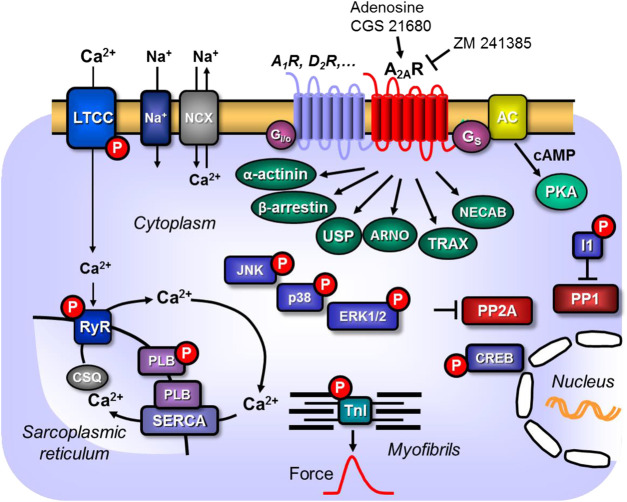

Figure 1.

Scheme: Putative mechanism(s) of signal transduction of cardiac A2A-adenosine receptors (A2a-ARs). A2a-ARs via stimulatory G-proteins (Gs) can activate adenylyl cyclase (AC) which would enhance the 3′-5′cyclic adenosine-phosphate (cAMP)-levels in compartments of the cardiomyocyte and activate cAMP-dependent protein kinases (PKA) which would increase the phosphorylation state and thereby the activity of various regulatory proteins in the cell. Moreover, phosphorylation state and thus the activity of ERK1/2, JNK, p38 and CREB could be enhanced by pathways via arrestins. PKA-stimulated phosphorylation might also increase the current through the L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) and/or release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) via the cardiac ryanodine receptor (RYR2); both processes would increase force of contraction by increasing the Ca2+ acting on myofilaments. In diastole, Ca2+ is pumped via the SR-Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) from the cytosol into the SR. Activity of SERCA is increased by phosphorylation of phospholamban (PLB). The latter effect might also follow from inhibition of PP2A (a serine/threonine phosphatase: PP) activity by MAP kinases and subsequent increased phosphorylation state and thus activation of I-1 (a specific inhibitory protein of PP1) which will lead to decreased activity of PP1. Reduced activity of PP2A (and/or PP1) can increase phosphorylation of additional proteins and might thus increase the Ca2+ -sensitivity of myofilaments by dephosphorylation of the myosin light chains in the myofilaments which would increase force of contraction. Thus, A2A-ARs might increase the Ca2+ -sensitivity of myofilaments. In addition, cardiac A2A-ARs might act via the non-canonical pathway of β-arrestin, via α-actinin, via the Arf nucleotide site opener/cytohesin-2, ubiquitin-specific processing protease, translin-associated protein-X and neuronal calcium-binding protein 2.

The three-dimensional structure of A2A-AR has been studied using crystallization. The X-ray structures of mutated human A2A-AR bound to the following agonists have been reported: adenosine or NECA (see Table 2; Lebon et al., 2012), CGS21680 (Lebon et al., 2015), UK-432097 (Xu et al., 2011), an A2A-AR agonist and a G protein mimetic (Carpenter et al., 2016), and A2A-AR antagonists (Table 3; Jaakola et al., 2008; Doré et al., 2011). The often used agonist CGS21680 (Table 2) binds to transmembrane regions 2 and 7 (Lebon et al., 2015). Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy was used to understand the coupling of A2A-AR to G protein signal transduction. This has been addressed with a special focus on the linking role of Asp522.50 (Massink et al., 2015; Eddy et al., 2018). Several human promoters of the A2A-AR gene have been characterized (Haskó and Pacher 2008; St Hilaire et al., 2009). In part, these promoters are thought to explain the upregulation and downregulation of the receptors under stressful conditions, such as ischemia.

TABLE 2.

Agonists at A2A-adenosine receptors.

IC50: in functional assays in µM.

TABLE 3.

A2A-adenosine receptor antagonists.

| Antagonist aname | Ki nM | Indications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theophylline | 1710 | Fredholm et al. (2011) | |

| Caffeine | 9,560–23,400 | Fredholm et al. (2011) | |

| Istradefylline | 2–91 | M. Parkinson | Fredholm et al. (2011), Cacciari et al. (2018) |

| Tozadenant | 5 | M. Parkinson | Cacciari et al. (2018) |

| ZM 241385 | 0.8 | Cacciari et al. (2018) | |

| MSX-2 | 5–8.0 | Fredholm et al. (2011), Cacciari et al. (2018) | |

| SCH 58261 | 1.1–5 | Fredholm et al. (2011), Cacciari et al. (2018) | |

| SCH 442416 | 0.048–4.1 | Fredholm et al. (2011), Cacciari et al. (2018) | |

| Preladenant | 0.9–1.1 | M. Parkinson | Fredholm et al. (2011), Cacciari et al. (2018) |

| Vipadenant | 1.3 | M. Parkinson | Cacciari et al. (2018) |

| ST 1535 | 6.6–11 | Fredholm et al. (2011), Cacciari et al. (2018) | |

| ST 4206 | 9 | Cacciari et al. (2018) | |

| CGS 15943 | 1.2 | Fredholm et al. (2011) | |

| CSC | 54 | Fredholm et al. (2011) | |

| V2006 | 1.3 | Fredholm et al. (2011) |

The range of Ki values is probably due to species differences and small difference in methodology.

Signal Transduction

In general, signal transduction (Figure 1; Table 4 of the A2A-AR involves binding to stimulatory guanosine triphosphate-binding proteins (Gs) in peripheral tissues (Kull et al., 2000; Fenton and Dobson 2007), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (Schulte and Fredholm 2000; Boucher et al., 2004), and an increase in the amplitude of Ca2+ transients (Woodiwiss et al., 1999) or the action on actinin (Burgueño et al., 2003). However, the positive inotropic effect of A2A-AR activation is not solely dependent on increases of Ca2+ in the cytosol of cardiomyocytes. In rat ventricular cardiomyocytes, activation has also been found to depend on Ca2+ independent mechanisms (i.e., an increased Ca2+ sensitivity of the myofilaments) (Woodiwiss et al., 1999). Due to the various physiological functions performed by different regions of the heart, it can be hypothesized that the expression and the signal transduction mechanisms of A2A-AR could differ between cardiomyocytes in several regions. However, this hypothesis should be tested. Researchers have found that the stimulation of A2A-AR increased cyclic-3′-5′-adenosine-monophophate (cAMP) levels, stimulated cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) and phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) (Németh et al., 2003), and activated non-canonical protein kinase B (AKT), extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK), protein kinase C (PKC) (De Ponti et al., 2007; Fredholm et al., 2007), and p38 signaling in skin cells (Perez-Aso et al., 2014).

TABLE 4.

A2A-adenosine receptor: Signal transduction.

| Signal | Species/cell type | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PP2A | Inhibition | Tikh et al. (2008) | |

| PP1 | Translocation and activation | Revan et al. (1996) | |

| Dermal fibroblasts | |||

| Thrombin induced ERK phosphorylation | Inhibits | Hirano et al. (1996) | |

| Gs | Kull et al. (2000), Fenton and Dobson (2007) | ||

| PI kinase | Schulte and Fredholm (2000), Boucher et al. (2004) | ||

| Ca2+ | Increased | Woodiwiss et al. (1999) | |

| Actinin | Burgueño et al. (2003) | ||

| Ca sensitivity | Increased | Woodiwiss et al. (1999) | |

| Phospho erk | Increased | Mouse heart | Ribé et al. (2008) |

| Phospho-p-38 | Increased | Mouse heart | Ribé et al. (2008) |

| Phospho-JNK | Increased | Mouse heart | Ribé et al. (2008) |

| Free radicals | Reduced | Mouse heart | Ribé et al. (2008) |

| Ca2+ sparks | Increased | Atrial human cardiomyocytes | Llach et al. (2011) |

| CREB phosphorylation | Increased | Leukocytes | Koshiba et al. (1999), review: Rabadi and Lee (2015) |

| Free radicals | Reduced | Neutrophils | Jordan et al. (1997) |

| Epac | Activated | Dermal fibroblasts | Perez-Aso et al. (2013) |

Interestingly, A2A-AR can also exert inhibitory effects in signal transduction; for example, it can inhibit thrombin-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Hirano et al., 1996). It is thought that the receptor probably increases the levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) in mouse hearts; higher levels of these proteins have been found in the hearts of wild-type (WT) mice than in the hearts of A2A-AR KO mice (Ribé et al., 2008). This finding was thought to explain why the production of free radicals was lower in the hearts of WT mice than in the hearts of A2A-AR KO mice (Ribé et al., 2008). The stimulation of the A2A receptor increased the cAMP levels, Ca2+ transients, and phospholamban and troponin I phosphorylation states in transgenic (TG) mice with a cardiac overexpression of A2A-AR, but not in WT mice (Boknik et al., 2018, Boknik et al., 2019). From these data, we can assume that more Ca2+ can be released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) because activation of the A2A-AR via PKA increases the phosphorylation state of the cardiac ryanodine receptor (RYR2), which opens the RYR2 (Figure 1; Llach et al., 2011).

Activation of the A2A-AR can also activate protein phosphatases, namely PP1, and can lead to the translocation of the PP1 activity from the soluble fraction to the particulate fraction (Revan et al., 1996). This would lead to the dephosphorylation of target proteins. Researchers also found that the activation of A2A-AR in mouse hearts inhibits the activity of PP2A in the myocardial particulate fraction, although this effect was not present in preparations from A2A-AR KO mice (Tikh et al., 2008). Interestingly, the researchers found that the stimulation of the A1-AR increased PP2A activity to a higher extent than the stimulation of the A2A-AR in WT mice (Tikh et al., 2008).

Interactions of the A2A-AR With Other Proteins

Studies have reported an interaction between A2A-AR and A1-AR (Chan et al., 2008, Table 5). In brief, the cardioprotective effect from the stimulation of the A1-AR was absent in the isolated hearts from A2A-AR KO mice after reperfusion following 30 min of global ischemia (Zhan et al., 2011). Another study found that the A2A-AR in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells formed heterodimers with cannabinoid CB1 receptors (Carriba et al., 2007). A2A-AR can also interact with the Arf nucleotide site opener/cytohesin-2, ubiquitin-specific processing protease, translin-associated protein-X, and neuronal calcium-binding protein 2 (Ciruela et al., 2010). The A2A-AR can form homodimers, homomultimers, and heterodimers with A1-AR, dopamine D2 receptors, and A2A-AR (Moriyama and Sitkovsky, 2010; Ferré et al., 2014; Bonaventura et al., 2015; Navarro et al., 2016). Moreover, homodimers or homomultimers of A2A-AR can also be formed (Canals et al., 2004). Interestingly, the dimeric form and not the monomeric form of the A2A-AR is thought to be the functional form (Burgueño et al., 2003). The A2A-AR can also form dimers and multimers with metabotropic glutamate receptor 5, N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) receptors and cannabinoid receptors (Headrick et al., 2013; Table 5; Figure 2). Functionally, the A1-AR, and possibly the A3-AR, can inhibit the relaxation in mouse aortic rings mediated by A2A-AR (Talukder et al., 2002; Tawfik et al., 2005). The A2A-AR can also form complexes with D2 dopamine receptors (Borroto-Escuela et al., 2011).

TABLE 5.

A2A-adenosine receptor interactions.

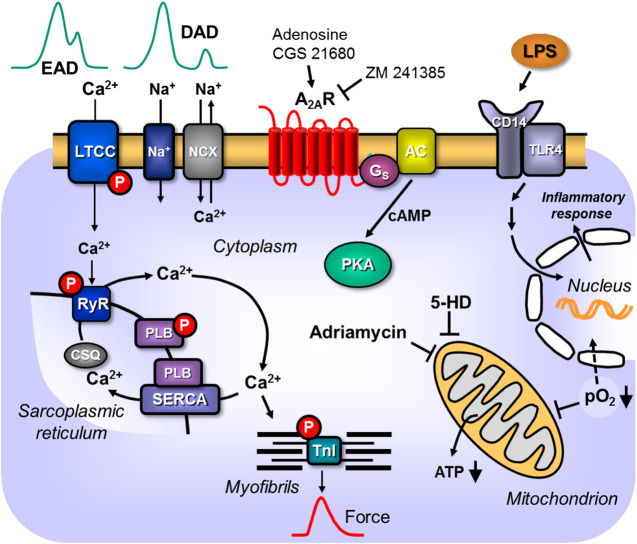

Figure 2.

Scheme: Putative pathophysiological role(s) of cardiac A2A-ARs. A2A-ARs can enhance LPS via receptors in the sarcolemmal alters nuclear gene transcription and putative detrimental proteins are made that impair cardiac contractility. Hypoxia and ischemia impair respiration and thus ATP formation in mitochondria or activate directly hypoxia dependent transcription factors. The mitochondrial process is attenuated by compounds like 5-hydroxy-deanoate (5-HD). Adriamycin impairs mitochondrial function. Hypertension can lead to hypertrophy which alters cardiac gene expression in detrimental ways leading to arrhythmias and heart failure. Altered expression of sarcolemmal ion channels and stimulation of A2A-ARs can lead to supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmias by alteration of Ca2+ homeostasis.

An interaction between the A1-AR and the A2A-AR occurs on a functional level in the heart. Stimulation of the A1-AR reduces the positive inotropic effect (i.e., an increase in the force of contraction) of isoproterenol, which is a β-adrenoceptor agonist. This well-known effect was attenuated in perfused rat hearts through the additional stimulation of the A2A-AR (Norton et al., 1999), as well as in the perfused hearts from WT mice; however, the effect was absent in the hearts of A2A-AR KO mice (Tikh et al., 2006). Similarly, isoproterenol increased Ca2+ transients in electrically stimulated rat ventricular cardiomyocytes; this effect was attenuated through the activation of A1-AR and the addition of A2A-AR antagonists (Norton et al., 1999). The constitutive overexpression of the A1-AR in the heart led to cardiac dilatation in mice, which was not seen in mice coexpressing A2A and A1 receptors; this might suggest there is a beneficial interaction between these receptors that is determined by the different effects of expression of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) (Chan et al., 2008).

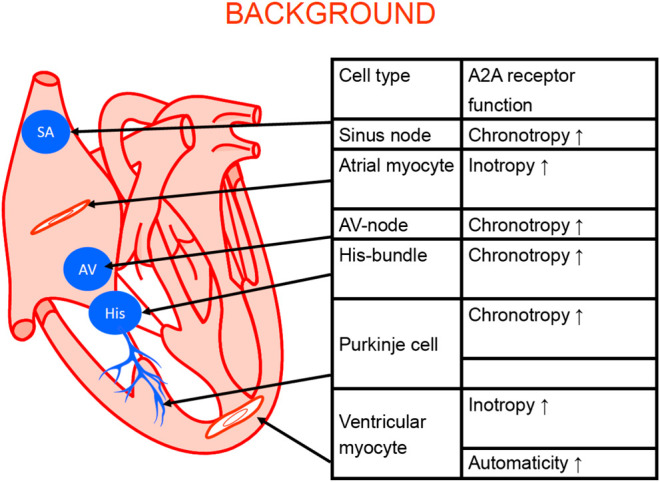

Expression

There are several types of cardiomyocytes in the heart: atrial cardiomyocytes form the main bulk of atrial muscle; ventricular cardiomyocytes; cardiomyocytes that form the path of the system that propagates depolarization from the sinus node, specialized cells in the atrium (Bachmann bundles), the sinus node (SA) node, Tawara branches, and Purkinje bundles (Figure 3). Alterations in this pathway are expected to be of clinical relevance because they can lead to various cardiac arrhythmias. Alterations in the expression of A2A-AR might be relevant for both primary arrhythmias due to inborn errors and secondary arrhythmias from ischemia, hypertrophy, drug treatment, or aging. However, more work on this topic needs to be undertaken.

Figure 3.

Schematic cardiac conducting system and regional adenosine receptor expression in the heart (modified from Stein et al., 1998). The anatomical localization of the sinus node (SA), the AV node (AV) the bundle of His (His). The Purkinje fibers (Purkinje) and the work generating muscle cells in the atrium and the ventricle are depicted. In these structures A2A-ARs were functionally and/or biochemically detected. Their stimulation can explain the functional consequence listed in the adjoining table.

In terms of the expression and cellular heterogeneity of A2A-AR in the heart, these receptors are known to be present and functional in blood cells that are continuously transported to and from the heart by the circulatory system (Table 6). A2A-AR comprise various types of leukocytes, macrophages, mast cells (Marquardt et al., 1994), neutrophils (Fredholm et al., 1996), thrombocytes, and erythrocytes. In histological studies, such as RNA detection using single cell polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or in situ hybridization, it is sometimes possible to clearly identify the receptor in different cell types; in studies using antibodies, the specificity can be poor. However, when using cardiac homogenates, the A2A-AR can be measured in all cell types and one might assume that the signal mainly arises from the cardiomyocytes but the signal might arise also from other cell types in the heart. For example, in one study, all P1 receptors, including A2A-AR, were detectable in the heart using reverse transcription and PCR (see Table 6). Adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes, as well as adult mouse and porcine ventricular cardiomyocytes, contained A2A-AR mRNA and protein (Xu et al., 1996; Marala and Mustafa 1998; Kilpatrick et al., 2002; Chandrasekera et al., 2010). Moreover, A2A-AR mRNA and protein were detected in human atrial preparations using Western blotting (Hove-Madsen et al., 2006; Llach et al., 2011); according to its histochemistry, A2A-AR were located with the cytoskeletal-associated protein α-actinin at the Z-line of the sarcomere in the atrial specimens (Hove-Madsen et al., 2006). A2A-AR have also been detected on endothelial cardiac cells (Hein et al., 1999) and vascular smooth muscle cells (Teng et al., 2008).

TABLE 6.

A2A-adenosine receptor: Tissue Distribution in heart and blood.

| Tissue | Species/cell type | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Cardiomyocytes | ||

| 1.1 | Adult rat | Xu et al. (1996); Kilpatrick et al. (2002) |

| 1.2 | Pig | Marala and Mustafa (1998) |

| 1.3 | Human | Hove-Madsen et al. (2006); Marala and Mustafa (1998); Llach et al. (2011) |

| 1.4 | Mouse | Chandrasekera et al. (2010), Morrison et al. (2006) |

| 2. Blood cells | ||

| 2.1 | Platelets | Amisten et al. (2008) |

| 2.2 | Mast cells | Review: Gao and Jacobson (2017) |

| 2.3 | Macrophages | Review: Haskó and Pacher (2012) |

| 2.4 | Neutrophils | Fredholm et al. (1996) |

| 2.5 | Erythrocytes | Kamata et al. (2008) |

| 3. Vascular smooth muscle cells | Teng et al. (2008) | |

| 4. Coronary endothelial cells | Hein et al. (1999), Olanrewaju and Mustafa (2000) | |

| 5. Lymphocytes | Review: Brown et al. (2008) | |

| 6. Basophils | Review: Brown et al. (2008) | |

| 7. Fibroblasts | Rat heart | Chen et al. (2004), Epperson et al. (2009) |

Altered A2A-AR Levels

The level of A2A-AR in tissues can be altered by various stimuli. Changes in these levels may have relevance to cardiac diseases. For example, carbon monoxide increases the expression of A2A-AR in macrophages (Haschemi et al., 2007). Similarly, when lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was used to induce inflammation, the expression of A2A-AR increased in murine and human macrophages and epithelium cells via the (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway (Murphree et al., 2005; Morello et al., 2006; Haskó and Pacher 2008). Hypoxia via hypoxia-inducible factor like HIF2α also increased the expression of A2A-AR in pulmonary endothelial cells (Ahmad et al., 2009). Pharmacological treatment can also increase A2A-AR: caffeine increas the A2A-AR density in for instance platelets (Varani et al., 1999). Likewise, diazepam treatment can increase the function of A2A-AR stimulation in rat pulmonary arteries (Ujfalusi et al., 1999). D2-dopamine receptor stimulation could increase the function (cAMP production) in neuroblastoma cells (Vortherms and Watt, 2004).

The expression of A2A-AR can also be diminished. For instance, increased cAMP levels reduced the expression of A2A-AR in cell cultures (Headrick et al., 2013). A2A-AR agonists can lead to desensitization (see Table 7), as seen with many other G protein-coupled receptors, possibly through binding the receptor to α-actinin and receptor internalization (Chern et al., 1993; Svenningsson et al., 1995, Svenningsson et al., 1999); this effect does not occur with antagonists (Halldner et al., 2000). In DDT1 MF-2 and PC12 cells, short-term (less than 30 min) treatment with an agonist reduced the subsequent induced increases in cAMP levels without any loss of A2A-AR on the cell surface (Ramkumar et al., 1991; Chern et al., 1993; Klaasse et al., 2008). Another study reported a functional desensitization after 2 h of treatment with NECA, which reduced the vasorelaxation of porcine coronary arteries after a second exposure of NECA (Conti et al., 1997). In cell cultures mutational analysis revealed there were different phosphorylation sites on the A2A-AR (Palmer and Stiles, 1997). In human monocytoid THP-1 cells, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TnF-α) inhibited the agonist-induced desensitization of A2A-AR by preventing the translocation of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2 to the plasma membranes (Khoa et al., 2006). The desensitization of A2A-AR seems to involve arrestin 2 and 3 (Burgueño et al., 2003). It is thought that the internalization of A2A-AR involves its C-terminus and its interaction with α-actinin (Burgueño et al., 2003).

TABLE 7.

A2A-adenosine receptor sensitization and desensitization.

| Agonist/Intervention | Tissue | Read out | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NECA | Relaxation of coronary bovine arteries | Force | Desensitization | Conti et al. (1997) |

| NECA | DD1 MF cells | cAMP | Desensitization | Ramkumar et al. (1991) |

| NECA | PC12 cells | cAMP | Desensitization | Chern et al. (1993) |

| Hypoxia | Pulmonary endothelial cells | A2A-AR mRNA | Sensitization | Ahmad et al. (2009) |

| Caffeine | Platelets | A2A-AR radio-ligand binding | Sensitization | Varani et al. (1999) |

| LPS | ||||

| Diazepam | Rat pulmonary arteries | Relaxation | Ujfalusi et al. (1999) | |

| D2 receptor stimulation | Neuroblastoma cells | cAMP | Vortherms and Watts (2004) |

Role of A2A-AR in Cardiac Disease

Arrhythmia

In TG mice, the genetic overexpression of A2A-AR (Figures 2, 3; Table 1) in the heart makes them much more susceptible than WT mice to negative inotropic effects and to the arrhythmogenic effects of intraperitoneally injected adriamycin (Hamad et al., 2010). This suggests that A2A-AR have a detrimental reaction to stressors, such as adriamycin; adriamycin is an anti-cancer drug that can cause heart failure and arrhythmias in some patients in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Compared with WT mice, the A2A-AR in TG mice might be more susceptible to adriamycin-induced arrhythmias because they express less connexin 43, which is a protein that is important for myocardial conduction (Hamad et al., 2010). Interestingly, when A2A-AR overexpression was induced after treatment with adriamycin, the mortality of the TG mice was lower than that of the WT mice (Hamad et al., 2010). One study reported that mice with a constitutive cardiac specific overexpression of A2A-AR had an increased basal heart rate (Chan et al., 2008). In patients with atrial fibrillation, the expression of A2A-AR was increased (Csóka et al., 2010). Stimulation of the A2A-AR in isolated human cardiomyocytes increases Ca2+ sparks by increasing the Ca2+ current through the sodium–calcium exchanger (INaCa), which can lead to cellular depolarization, initiate afterdepolarizations, and cause cardiac arrhythmias (Figure 2; Llach et al., 2011). A2A-AR have also been expressed in human atrial preparations, which may lead to alterations in the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ release (Hove-Madsen et al., 2006). Alternatively, the action of adenosine can induce bradycardia and subsequently lead to atrial fibrillation (Isa-Param et al., 2006). Ischemia can also induce increases in adenosine, which can lead to arrhythmias (Bertolet et al., 1997).

Interestingly, one study found that atrial dilation and atrial fibrillation were accompanied by an increase in A2A-AR mRNA and protein levels, which was conceivably due to an increase in RyR2 phosphorylation (Llach et al., 2011). This may alter the flow of Ca2+ through the sarcolemmal sodium–calcium ion exchanger (NCX) and lead to arrhythmias (Figure 2; Llach et al., 2011). The study found that the stimulation of the A2A-AR induced altered Ca2+ sparks in isolated human atrial myocytes (Llach et al., 2011). Moreover, CGS21680 enhanced currents through the NCX in isolated atrial cardiomyocytes from patients with atrial fibrillation, but not in samples from patients in sinus rhythm (Llach et al., 2011). Interestingly, endogenous adenosine is able to stimulate NCX in atrial cardiomyocytes from patients with atrial fibrillation (Llach et al., 2011).

It has been suggested that the stimulation of A2A-AR may increase the Ca2+ content of the SR and the stimulation of the NCX might increase Ca2+ inflow in cells. The increased levels of Ca2+ in the SR may result in an increased release of Ca2+ from the SR, which can lead to delayed afterdepolarization and, thus, to atrial arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation (Figure 2). There is evidence that the stimulation of A2A-AR mediates vasodilation, which may lead to tachycardia by reducing blood pressure. The decrease in blood pressure leads to reflective tachycardia through the stimulation of the baroreceptor, which stimulates the sympathomimetic outflow from the central nervous system. In living rats, the stimulation of the A2A-AR leads to tachycardia by the direct activation of the sympathetic tone and by the release of noradrenaline, which stimulates the β-adrenoceptors on the sinus node (Dhalla et al., 2006). Using telemetric electrocardiograms, we confirmed the positive chronotropic effect of A2A-AR expression alone and its stimulation by a selective A2A-AR agonist in living animals (Boknik et al., 2019). It is relevant that we could detect an enhanced incidence of arrhythmias in living animals after stimulation of the A2A-AR because it may indicate that the proarrhythmic effect of A2A-AR expression is so strong that vagal or other neural compensatory mechanisms cannot overcome it (Boknik et al., 2019). We predict that the same might apply in humans. There is experimental evidence that the positive chronotropic effect of A2A-AR stimulation by regadenoson was caused by the direct stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system in rats (Woodiwiss et al., 1999). Another study showed that the stimulation of A2A-AR in isolated human atrial myocytes promoted irregularities in Ca2+ transients, such as spontaneous calcium ion waves (Csóka et al., 2010). Spontaneous Ca2+ release has been reported to initiate atrial fibrillation in human atrial myocytes (Monahan et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 2011; Llach et al., 2011). Future studies should determine whether the increase in A2a-AR is the cause or the result of atrial fibrillation in humans.

Ischemia and Hypoxia

In general, A2A-AR exert a protective role in the heart. For instance, the A2A-AR can protect the brain against ischemia (Jiang et al., 2011; Fronz et al., 2014; Melani et al., 2014). However, contradictory results have been reported. For instance, one study found that the stimulation of A2A-AR produced detrimental effects in the brain of A2A-AR KO mice, while an antagonist was associated with beneficial effects in the brain in theses mice (Phillis, 1995; Chen et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2007). Similar effects were noted in the kidney, which could be partly explained by the fact that A2A-AR mediate vasodilation and anti-inflammatory effects by reducing the production of cytokine and chemokine in leukocytes, including macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils, in the kidney (Rabadi and Lee, 2015). The mechanism may involve cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of CREB and subsequent alterations in gene transcription (Rabadi and Lee, 2015). The activation of A2A-AR in regulatory T lymphocytes (Koshiba et al., 1999) also plays a part in renal protection (review: Rabadi and Lee, 2015; Lasley, 2018). However, the stimulation of the A2A-AR in mice with cecal ligation had detrimental effects, as seen in that model of chronic inflammation and sepsis (Haskó and Pacher, 2008). Thus, depending on the method of disease generation, as well as the acute or chronic nature of inflammation, A2A-AR play two contrasting roles in the heart. As previously mentioned, reperfusion leads to cardiac dysfunction if ischemia is prolonged, which is partially due to non-cardiomyocytes, such as neutrophils. The activation of A2A-AR diminished neutrophil adherence to endothelial cells and decreased the production of superoxide anions; this might partly mediate reperfusion injury in the mammalian heart (Jordan et al., 1997). However, in rabbits, the stimulation of A2A-AR could reduce cardiac ischemia-induced arrhythmia (Schreieck and Richardt, 1999).

In the present context, A2A-AR could protect the myocardium of adult rats with an coronary occlusion (Lozza et al., 1997; Ke et al., 2015). A2A-AR agonists also protect the heart function against septic injury (Thiel et al., 1998; Tofovic et al., 2001; Braun-Dullaeus et al., 2003; Reutershan et al., 2007). However, what is the role of endogenous adenosine in sepsis? In A2A-AR KO mice, sepsis was more pronounced than in WT mice (Reichelt et al., 2013; Ashton et al., 2017) or unaltered (Reutershan et al., 2007). Therefore, the role of A2A-AR in sepsis might be quite subtle; age and gender might also be a factor, as older male KO mice exhibited a poor prognosis (Ashton et al., 2017). A2A-AR also protect against postconditioning (Dhalla et al., 2006; Morrison et al., 2007; review; McIntosh and Lasley 2012) and preconditioning (Button et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2005) and ischemia and reperfusion in vivo rats (Kis et al., 2003; Ke et al., 2015). However, some studies of preconditioning showed that the stimulation of A2A-AR prior to ischemia did not provide any protection against a decrease in force (reviewed in McIntosh and Lasley, 2012). Activation of A2A-AR in postconditioning might be of special therapeutic utility for patients with coronary heart disease. Reperfusion of coronary arteries in patients by balloon dilation can sometimes lead to arrhythmias or a reduction in the force of contraction to levels lower than those before occlusion. These detrimental complications of reperfusion could be attenuated in the clinic by giving an A2A-AR-agonist intravenously before reopening the occluded artery. For instance, rats in an in vivo ischemia model were given A2A-AR agonists, such as CGS21680, which was beneficial in preventing biochemical signs of autophagy (Ke et al., 2015). Cardiac specific overexpression of A2A-AR in mice, increased the sustaining of pressure after reperfusion, possibly by altering the electrical properties of cardiomyocytes and these beneficial effects were absent when A2A-AR antagonists were used supporting the studies on a beneficial effect of A2A-AR stimulation prior to ischemia and reperfusion. This beneficial effect translates to a longer time to contracture during ischemia in these hearts. The beneficial effect might be due effects on the mitochondria Boknik et al., 2018.

A lack of beneficial effects from the activation of A2A-AR on cardiac preconditioning has also been reported (Lasley and Mentzer, 1992; Thornton et al., 1992; Yao and Gross, 1993; Lasley et al., 2007). This result might be due to the use of different species or methods, such as the type and dose of agonist used, and the timing of the agonist application.

It is possible that more than one type of cell is involved in the mechanism of cardioprotection. Lymphocytes, neutrophils, mast cells, basophils, dendritic cells, monocytes, epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and macrophages contain A2A-AR (Revan et al., 1996; Jordan et al., 1997; Germack and Dickenson, 2005; Rork et al., 2008; Csóka et al., 2012; Burnstock and Boeynaems, 2014). A2A-AR are also present on platelets; activation of these receptors inhibits platelet aggregation (review: Burnstock 2015). It has been suggested that the A2A-AR contribute to the functional cardioprotective action of the A1-AR (Methner et al., 2010; Urmaliya et al., 2010; Zhan et al., 2011). A beneficial interaction between the A2A-AR and the A2B-AR has been described in the heart (Xi et al., 2009). The protective mechanism of the A2A-AR seems to involve actions on the mitochondria of the heart in rats (Ke et al., 2015). In pulmonary endothelial cells, hypoxia via HIF2α not only increases the density of the A2A-AR mRNA and protein, but also generates more adenosine through the induction of adenosine-producing enzymes (Ahmad et al., 2009). Moreover, the overexpression of A2A-AR in human lung microvascular endothelial cells led to an increase in cell proliferation and promoted increased angiogenesis (Ahmad et al., 2009). An increased expression of A2A-AR in tumors was noted in patients with lung cancer compared with healthy lung regions from the same patients (Ahmad et al., 2009). In hypoxia, the uptake of adenosine into cells is diminished, which leads to high extracellular concentrations of adenosine that activate the A2A-AR (Eltzschig et al., 2005; Löffler et al., 2007; Morote-Garcia et al., 2009). Low concentrations of adenosine are expected to bind to and activate the high-affinity A1-AR; in a pathophysiological context, further increases in adenosine activate the A2A-AR because of their low affinity for adenosine. However, in functional cAMP production in cells, A1-AR and A2-ARbshow the same affinity for adenosine (Fredholm, 2014). Under basal physiological conditions, adenosine concentrations range between 30 and 200 nM, which are sufficient to activate both A1-AR and A2A-AR (Fredholm, 2014). Very high levels of adenosine (1 µM adenosine) were reported after platelet aggregation (Fredholm, 2014), ischemia, and necrotic cell death (Fredholm, 2014). The A2A-AR can lead to the dilation of coronary arteries and might be deleterious in patients with Morbus Parkinson (Fredholm, 2014). Clinically, adenosine and its precursor ATP are useful for stopping supraventricular arrhythmias. Therefore, the actions of adenosine in mammalian hearts are of clinical relevance and merit further investigation.

Whereas A1-AR and A3-AR protect the heart when activated before ischemia, stimulation of A2A-AR can protect a rat heart at the beginning of a reperfusion injury (Jordan et al., 1997; Cargnoni et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2006; Kuno et al., 2008; Headrick and Lasley, 2009; Xi et al., 2009; Methner et al., 2010). Overexpression of A2A-AR protects against cardiac damage because the enzymatic activity of AST, which is a marker for the inability of the sarcolemma to contain ingredients within the cell, only increased in the WT mice and not in the TG mice (Boknik et al., 2018). In all probability, this protection was mediated by the A2A-AR because the protective effect in the TG mice was abolished by applying the A2A-AR antagonist ZM 241385 (Boknik et al., 2018). The protective effect may involve the mitochondria, as the phosphorylation state of pAKT was increased to a higher extent during reperfusion in the TG mice than in the WT mice (Boknik et al., 2018, 2019).

It might be speculated that if A2A-AR are beneficial in reperfusion, one might try to increase the levels of A2A-AR in the heart by injection of adenovirus containing the cDNA for the A2A-AR intravenously or even in the coronary arteries. In this way it may be possible to increase the A2A-AR in leukocytes but also in coronary endothelial cells. The amount of the adenovirus should probably not be so elevated as also the increase A2A-AR in cardiomyocytes: though this might improve cardioprotection (Boknik et al., 2018), there is the danger to induce sinus tachycardia or other arrhythmias (Boknik et al., 2019), known for all cAMP-increasing agents.

Heart Failure

There is a debate about whether A2A-AR are functional (i.e., increase cAMP and contractility) in the mammalian heart; the effect of A2A-AR may also be species- or method-dependent. Studies have reported a lack of effect in the rat (Shryock et al., 1993), guinea pig (Behnke et al., 1990; Boknik et al., 1997), and rabbit (Kilpatrick et al., 2002). However, other studies have reported a functional response in mice (Morrison et al., 2006) and rats (Monahan et al., 2000). It is important to note that A2A-AR protein levels have been detected in human hearts (Marala and Mustafa, 1998). Work on isolated and perfused A2A-AR KO (i.e., constitutive deletion) mouse hearts clearly established that the A2A-AR agonist CGS21680 was selective; <1 µM CGS21680 increased contractility in WT mouse hearts, but not in hearts from A2A-AR KO mice (Morrison et al., 2002). Furthermore, we noted a functional role of A2A-AR stimulation in isolated paced right atrial preparations from diseased human hearts (Boknik et al., 2018). However, under basal conditions in which no CGS21680 was given, there was no difference in the contractility of WT and KO mouse hearts (Ashton et al., 2017; Morrison et al., 2002). The stimulation of the A2A-AR produced a positive inotropic effect (Table 8; Woodiwiss et al., 1999; Monahan et al., 2000; Chan et al., 2008; Dobson et al., 2008; Tikh et al., 2008), which increased in the presence of additional A1-AR blockade DPCPX (Fredholm et al., 2011 for selectivity of DPCPX). One study noted that the stimulation of A2A-AR had no positive inotropic effect (Kilpatrick et al., 2002). Some studies reported that the A2A-AR increased in patients with heart failure (Stein et al., 1998), while one study found that A2A-AR mRNA level decreased in Japanese patients with heart failure (Asakura et al., 2007). The plasma adenosine concentration increases in human heart failure (Funaya et al., 1997). In neutrophils and T cells, the expression of A2A-AR is regulated by miR-214, miR15, and miR 16 (Heyn et al., 2012). Other studies have reported on a constitutive cardiac specific overexpression (Chan et al., 2008) or an inducible overexpression (Hamad et al., 2010) of human A2A-AR in a mouse heart. One group used their model to study the in vivo functional interaction of A1-coexpression with A2A-AR (Chan et al., 2008). A2A-AR have a protective role in pressure overload from aortic banding (Hamad et al., 2012) and against cardiomyopathy from chronic adriamycin treatment (Hamad et al., 2010).

TABLE 8.

Species- and region-dependent cardiac effects of stimulation of cardiac A2A-adenosine receptors.

| Species/tissue | A2A-AR agonist used | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Human atrium | Boknik et al. (2018) | PIE | CGS 21680 |

| Human ventricle | ND | ||

| Rat cardiomyocytes | Woodiwiss et al. (1999) | PIE | CGS 21680 |

| Perfused rat ventricle | Monahan et al. (2000) | PIE | Adenosine |

| Rat ventricular cardiomyocytes | Shryock et al. (1993) | No PIE | WRC 0090 |

| WRC 0013 | |||

| Guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes | Shryock et al. (1993) | No PIE | WRC 0090 |

| WRC 0013 | |||

| Rabbit ventricular cardiomyocytes | Shryock et al. (1993) | No PIE | WRC 0090 |

| WRC 0013 | |||

| Guinea pig atrium | Böhm et al. (1986) | No PIE | NECA |

| Guinea pig ventricle | Isolated cardiomyocytes: Behnke et al. (1990), Boknik et al. (1997) | No PIE | NECA |

| No PIE | CGS 21680 | ||

| Mouse atrium | Wild type mice: left atria, Boknik et al. (2018), Boknik et al. (2019) | No PIE | No PCE |

| CGS 21680 | CGS 21680 | ||

| Mouse atrium | A2A receptor overexpressing mice atria: Boknik et al. (2018), Boknik et al. (2019) | PIE | PCE |

| CGS 21680 | CGS 21680 | ||

| Mouse ventricle wild type | Tikh et al. (2008), Boknik et al. (2018), Boknik et al. (2019) | PIE | CGS 21680 |

| CGS 21680 | |||

| Mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes wild type | Dobson et al. (2008) | PIE | CGS 21680 |

| Mouse ventricle | A2A receptor overexpressing mice: Boknik et al. (2018) | PIE | PCE |

| CGS 21680 | CGS 21680 | ||

| Rabbit ventricle | Kilpatrick et al. (2002) | No PIE | CGS 21680 |

ND, not done; No, no inotropic effect; PCE, positive chronotropic effect; PIE, increase in contractility.

It might be speculated that physiological alterations of the A2A-AR occur in myocardial ischemia; for instance, changes could happen during infarction and stenting of a vessel. Therefore, the receptors may present a target for the pharmacological treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. However, more detailed studies are needed.

Following ischemia in the brain, there was an increased expression of A2A-AR (Trincavelli et al., 2008). The beneficial effects of A2A-AR activation have been reported in autoimmune diseases, such as colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and hepatitis, as well as after mechanical trauma to the nervous system (Choukèr et al., 2008; Di Paola et al., 2010; Mazzon et al., 2011; Paterniti et al., 2011). Polymorphisms of the A2A-AR have been correlated with human chronic heart failure (Zhai et al., 2015).

It is questionable to stimulate endogenous (or by application of an adenovirus containing the cDNA for the A2A-AR), as the A2A-AR will increase cAMP and cAMP increase can lead to arrhythmias. Another caveat is in order: to the best of our knowledge, it has not been reported that A2A-AR agonist can increase force of contraction in the human ventricle, though this is usually taken for granted (Table 8).

Clinical Relevance of A2A-AR Agonists and Antagonists

A2A-AR activation is used in clinics to assess the vasodilatory functions of coronary arteries during nuclear magnetic studies. Adenosine is also used to treat supraventricular arrhythmias. Some of the adverse effects of adenosine include flushing and hypotension; these effects have been attributed to the action of vasodilatory A2A-AR (review: Headrick et al., 2013). The A2A-AR antagonists istradefylline and tozadenant are new compounds that have been used to treat patients with Morbus Parkinson (review: Chen et al., 2013) or sickle cell disease (Chen et al., 2013).

Many people drink coffee or tea that contains caffeine and theophylline at levels that can block A1-, A2A-, A2B- and A3-AR (Fredholm et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2013). Thus, caffeine might interfere with agonists, but might potentiate antagonists. Clinical studies have found that caffeine was beneficial in patients with Morbus Parkinson (Chen et al., 2013).

A2A-AR agonists and antibodies have also been clinically applied (Table 9; Cargnoni et al., 1999; Cerqueira et al., 2008; Palani et al., 2011; Molina et al., 2016). For instance, the A2A-AR agonists ATL 146e and MRE-0094 have been investigated to promote wound healing in patients with chronic neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers; they have also been used to treat arthopathies; lung diseases, such as COPD; hepatic ischemic diseases; renal ischemic diseases; inflammatory bowel disease; and ischemic brain diseases (Haskó and Pacher, 2008). One possible drawback to using these agonists is that they stimulate the A2A-AR on vascular smooth muscle cells, which would lead to vasodilation and a subsequent decrease in blood pressure (Hein et al., 1999; Haskó et al., 2006). Thus, these agonists may be used as antihypertensive agents, but should not be used to treat foot ulcers. After chronic stimulation of A2A-AR, the downregulation of a homologous receptor might occur for many G protein-coupled receptors, such as the 5-HT4-serotonin receptor (Gergs et al., 2017). If the stimulation of an immune receptor is intended, then an A2A-AR antagonist for cardiac disease might be tried. For instance, A2A-AR antagonists have been used at the clinic for the treatment of patients with Morbus Parkinson. Moreover, theophylline, which is used to increase mucociliary clearance in patients with COPD, and dipyridamole, which inhibits adenosine transporters on cell surfaces, increase adenosine levels near A2A-AR. Adenosine and its metabolite inosine can be transported through cell membranes by bidirectional and concentrative transporters (Podgorska et al., 2005). One of the side effects associated with the use of adenosine to stop paroxysmal supraventricular arrhythmias involves bronchoconstriction by the stimulation of the bronchostrictory A2A-AR (Chen et al., 2013). A2A-AR agonists, such as regadenoson, are clinically used to detect latent ischemia in patients (Cerqueira et al., 2008). Other experimental agonists include CGS21680, UK-432097, and BVT115959 (Jacobson and Müller, 2016). Therefore, activation of A2A-AR could lead to arrhythmias in patients that have high expression levels of A2A-AR in the heart.

TABLE 9.

Diseases suggested to involve A2A-adenosine receptors (review: Burnstock, 2017).

| Disease | Therapy | References |

|---|---|---|

| M. Alzheimer | Agonist | Cunha (2016) |

| M. Parkinson | Antagonist | Jenner (2014) |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | Antagonist | Volonté et al. (2016) |

| Brain injury | Agonist | Dai and Zhou (2011) |

| Schizoprenia | Agonist | Matos et al. (2015) |

| Depression | Antagonist | Yamada et al. (2014) |

| Addiction (e.g. cocain) | Antagonist | Pintsuk et al. (2016) |

| Cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury | Agonist | Ke et al. (2015) |

| Atrial fibrillation | Antagonist | Molina et al. (2016) |

| Atherosclerosis | Agonist | Reiss and Cronstein (2012) |

| Coronary would healing | Agonist | Du et al. (2015) |

| Thrombosis | Agonist | Hofer et al. (2013) |

| Asthma | Agonist | Wang et al. (2018) |

| COPD | Agonist | Basu et al. (2017) |

| Acute lung injury | Agonist | Friebe et al. (2014) |

| Cystic fibrosis | Agonist | Esther et al. (2013) |

| Lung cancer | Antagonist | Mediavilla-Varela et al. (2013) |

| Pleural inflammation | Agonist | da Rocha Lapa et al. (2012) |

| Rhinosinusitis | Agonist | Hua et al. (2013) |

| Diabetes | Antagonist | Ibrahim et al. (2011) |

| Obesity | Antagonist | De Oliveira Moreira, et al. (2017) |

| Acute renal injury | Agonist | Vincent and Okusa (2015) |

| Diabetic nephropathy | Agonist | Persson et al. (2015) |

| Liver fibrosis | Antagonist | Ahsan and Mehal (2014) |

| Liver cirrhosis | Agonist | Choukèr et al. (2008) |

| Psoriasis | Agonist | Merighi et al. (2017) |

| Scleroderma | Antagonist | Chan and Cronstein (2010) |

| Skin wound healing | Agonist | Shaikh and Cronstein (2016) |

| Myasthenia gravis | Agonist | Oliveira et al. (2015) |

| Osteoarthritis | Agonist | Corciulo et al. (2017) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Agonist | Mazzon et al. (2011) |

Ongoing Clinical Studies

There is an ongoing study using oral AB928, a novel dual A2aR/A2bR antagonist (Seitz et al., 2019) to treat prostate cancer by inhibiting AR mediated cell proliferation (University of California, United States: clinical trials.gov identifier: NCT04381832). There is another trial on prevention of injury of ischemia and reperfusion using regadenoson which is an A2AR agonist: in this case the ischemic injury in the lung blood vessels in lung transplantation will be tried to treat using intravenously applied regadenoson (University of Maryland, United States: clinical trials.gov NCT04521569). A similar trial is ongoing in Toronto, Canada (clinical trials.gov identifier: NCT04521569) Another trial is mainly intended to used expression levels of A2A-AR as a prognostic factor in cardiovascular disease. More specifically this study is evaluating the discriminating capacities of A2A adenosine receptors expression on the surface of circulating lymphocytes for the detection of coronary artery disease in patients hospitalized for surgery of the aorta and/or arteries of the lower limbs (Marseille, France: clinical trials.gov identifier NCT04640844).

Open Questions

The roles of various canonical and non-canonical pathways of A2A-R signal transduction merit further investigation. Biased agonists might offer new therapeutic options. The exact roles of A2A-AR in chronic heart failure, ischemia, and reperfusion, as well as in cardiac protection against myocardial infarction and arrhythmias need to be more carefully studied and translated into clinical settings. It remains unclear whether A2A-AR agonists or antagonists might be useful. It is conceivable that interactions with other receptors are important in therapeutic drug development. It is unknown whether an upregulation or downregulation by receptor ligands, adenoviral approaches, or antisense RNA approaches would be clinically useful. Many of these questions will be answered in the near future and this progress will be observed with great interest. It is hoped that developments will be used to benefit patients.

Summary

Over the years a consent has emerged that A2A-AR are present and functional in the mammalian heart, more importantly in the human heart. Evidence has accumulated that

The A2A-AR is important for coronary flow, which is relevant under clinical conditions and used in to assess e.g. the coronary reserve in patients with coronary heart disease. A2A-AR might be relevant for force generation in the human heart and for the genesis of arrhythmias. Hence, A2A-AR agonist and antagonists are clinically used. A2A-AR agonist mainly for diagnostic purposes (assessment of coronary reserve) and might be used in the future as positive inotropic agents. A2A-AR antagonist might become useful as novel options in some subtypes of heart failure.

Author Contributions

JN initiated the project. BH, NZ, and UG added own topics and aspects. UG, PB, and JN finalized the figures and body text. All authors read and approved submission of this version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad A., Ahmad S., Glover L., Miller S. M., Shannon J. M., Guo X., et al. (2009). Adenosine A2A receptor is a unique angiogenic target of HIF-2alpha in pulmonary endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (26), 10684–10689. 10.1073/pnas.0901326106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan M. K., Mehal W. Z. (2014). Activation of adenosine receptor A2A increases HSC proliferation and inhibits death and senescence by down-regulation of p53 and Rb. Front. Pharmacol. 5, 69 10.3389/fphar.2014.00069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amisten S., Braun O. O., Bengtsson A., Erlinge D. (2008). Gene expression profiling for the identification of G-protein coupled receptors in human platelets. Thromb. Res. 122 (1), 47–57. 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura M., Asanuma H., Kim J., Liao Y., Nakamaru K., Fujita M., et al. (2007). Impact of adenosine receptor signaling and metabolism on pathophysiology in patients with chronic heart failure. Hypertens. Res. 30 (9), 781–787. 10.1291/hypres.30.781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton K. J., Reichelt M. E., Mustafa S. J., Teng B., Ledent C., Delbridge L. M., et al. (2017). Transcriptomic effects of adenosine 2A receptor deletion in healthy and endotoxemic murine myocardium. Purinergic Signal. 13 (1), 27–49. 10.1007/s11302-016-9536-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastia E., Xu Y. H., Scibelli A. C., Day Y. J., Linden J., Chen J. F., et al. (2005). A crucial role for forebrain adenosine A(2A) receptors in amphetamine sensitization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (5), 891–900. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S., Barawkar D. A., Ramdas V., Patel M., Waman Y., Panmand A., et al. (2017). Design and synthesis of novel xanthine derivatives as potent and selective A(2B) adenosine receptor antagonists for the treatment of chronic inflammatory airway diseases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 134, 218–229. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke N., Müller W., Neumann J., Schmitz W., Scholz H., Stein B. (1990). Differential antagonism by 1,3-dipropylxanthine-8-cyclopentylxanthine and 9-chloro-2-(2-furanyl)-5,6-dihydro-1,2,4-triazolo(1,5-c)quinazolin-5-im ine of the effects of adenosine derivatives in the presence of isoprenaline on contractile response and cyclic AMP content in cardiomyocytes. Evidence for the coexistence of A1- and A2-adenosine receptors on cardiomyocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 254 (3), 1017–1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolet B. D., Hill J. A., Kerensky R. A., Belardinelli L. (1997). Myocardial infarction related atrial fibrillation: role of endogenous adenosine. Heart. 78 (1), 88–90. 10.1136/hrt.78.1.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukers M. W., Chang L. C., von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel J. K., Mulder-Krieger T., Spanjersberg R. F., Brussee J., et al. (2004). New, non-adenosine, high-potency agonists for the human adenosine A2B receptor with an improved selectivity profile compared to the reference agonist N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine. J. Med. Chem. 47 (15), 3707–3709. 10.1021/jm049947s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhm M., Brückner R., Neumann J., Schmitz W., Scholz H., Starbatty J. (1986). Role of guanine nucleotide-binding protein in the regulation by adenosine of cardiac potassium conductance and force of contraction. Evaluation with pertussis toxin. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 332 (4), 403–405. 10.1007/BF00500095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boknik P., Drzewiecki K., Eskandar J., Gergs U., Grote-Wessels S., Fabritz L., et al. (2018). On the existence of a possible A2A-D2-β-Arrestin2 complex: A2A agonist modulation of D2 agonist-induced β-arrestin2 recruitment. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 13 10.3389/fphar.2018.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boknik P., Drzewiecki K., Eskandar J., Gergs U., Hofmann B., Treede H., et al. (2019). Evidence for arrhythmogenic effects of A2A-adenosine receptors. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1051 10.3389/fphar.2019.01051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boknik P., Neumann J., Schmitz W., Scholz H., Wenzlaff H. (1997). Characterization of biochemical effects of CGS 21680C, an A2-adenosine receptor agonist, in the mammalian ventricle. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 30 (6), 750–758. 10.1097/00005344-199712000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaventura J., Navarro G., Casadó-Anguera V., Azdad K., Rea W., Moreno E., et al. (2015). Allosteric interactions between agonists and antagonists within the adenosine A2A receptor-dopamine D2 receptor heterotetramer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112 (27), E3609–E3618. 10.1073/pnas.1507704112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boros D., Thompson J., Larson D. F. (2016). Adenosine regulation of the immune response initiated by ischemia reperfusion injury. Perfusion. 31 (2), 103–110. 10.1177/0267659115586579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borroto-Escuela D. O., Romero-Fernandez W., Tarakanov A. O., Ciruela F., Agnati L. F., Fuxe K. (2011). On the existence of a possible A2A-D2-β-Arrestin2 complex: A2A agonist modulation of D2 agonist-induced β-arrestin2 recruitment. J. Mol. Biol. 406 (5), 687–699. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher M., Pesant S., Falcao S., de Montigny C., Schampaert E., Cardinal R., et al. (2004). Post-ischemic cardioprotection by A2A adenosine receptors: dependent of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 43 (3), 416–422. 10.1097/00005344-200403000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Dullaeus R. C., Dietrich S., Schoaff M. J., Sedding D. G., Leithaeuser B., Walker G., et al. (2003). Protective effect of 3-deazaadenosine in a rat model of lipopolysaccharide-induced myocardial dysfunction. Shock. 19 (3), 245–251. 10.1097/00024382-200303000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. A., Spina D., Page C. P. (2008). Adenosine receptors and asthma. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153 (Suppl 1), S446–S456. 10.1038/bjp.2008.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgueño J., Blake D. J., Benson M. A., Tinsley C. L., Esapa C. T., Canela E. I., et al. (2003). The adenosine A2A receptor interacts with the actin-binding protein alpha-actinin. J. Biol. Chem. 278 (39), 37545–37552. 10.1074/jbc.M302809200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. (2017). Purinergic Signalling: Therapeutic Developments. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 661 10.3389/fphar.2017.00661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G., Boeynaems J. M. (2014). Purinergic signalling and immune cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10 (4), 529–564. 10.1007/s11302-014-9427-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. (2015). Blood cells: an historical account of the roles of purinergic signalling. Purinergic Signal. 11 (4), 411–434. 10.1007/s11302-015-9462-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button L., Mireylees S. E., Germack R., Dickenson J. M. (2005). Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and ERK1/2 are not involved in adenosine A1, A2A or A3 receptor-mediated preconditioning in rat ventricle strips. Exp. Physiol. 90 (5), 747–754. 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.030635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello N., Gandía J., Bertarelli D. C., Watanabe M., Lluís C., Franco R., Ferré S., Luján R., Ciruela F. (2009). Metabotropic glutamate type 5, dopamine D2 and adenosine A2a receptors form higher-order oligomers in living cells. J. Neurochem. 109 (5), 1497–1507. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06078.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciari B., Spalluto G., Federico S. (2018). A2A adenosine receptor antagonists as therapeutic candidates: are they still an interesting challenge? Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 18 (14), 1168–1174. 10.2174/1389557518666180423113051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canals M., Burgueño J., Marcellino D., Cabello N., Canela E. I., Mallol J., et al. (2004). Homodimerization of adenosine A2A receptors: qualitative and quantitative assessment by fluorescence and bioluminescence energy transfer. J. Neurochem. 88 (3), 726–734. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02200.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargnoni A., Ceconi C., Boraso A., Bernocchi P., Monopoli A., Curello S., et al. (1999). Effects of age, gender, obesity, and diabetes on the efficacy and safety of the selective A2A agonist regadenoson versus adenosine in myocardial perfusion imaging integrated ADVANCE-MPI trial results. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 33 (6), 883–893. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter B., Nehmé R., Warne T., Leslie A. G., Tate C. G. (2016). Structure of the adenosine A2A receptor bound to an engineered G protein. Nature. 536 (7614), 104–107. 10.1038/nature18966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriba P., Ortiz O., Patkar K., Justinova Z., Stroik J., Themann A., et al. (2007). Striatal adenosine A2A and cannabinoid CB1 receptors form functional heteromeric complexes that mediate the motor effects of cannabinoids. Neuropsychopharmacology. 32 (11), 2249–2259. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira M. D., Nguyen P., Staehr P., Underwood S. R., Iskandrian A. E. (2008). ADVANCE-MPI Trial Investigators. Effects of age, gender, obesity, and diabetes on the efficacy and safety of the selective A2A agonist regadenoson versus adenosine in myocardial perfusion imaging integrated ADVANCE-MPI trial results. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 1 (3), 307–316. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E. S., Cronstein B. N. (2010). Adenosine in fibrosis. Mod. Rheumatol. 20 (2), 114–122. 10.1007/s10165-009-0251-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan T. O., Funakoshi H., Song J., Zhang X. Q., Wang J., Chung P. H., et al. (2008). Cardiac-restricted overexpression of the A(2A)-adenosine receptor in FVB mice transiently increases contractile performance and rescues the heart failure phenotype in mice overexpressing the A(1)-adenosine receptor. Clin Transl Sci. 1 (2), 126–133. 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2008.00027.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekera P. C., McIntosh V. J., Cao F. X., Lasley R. D. (2010). Differential effects of adenosine A2a and A2b receptors on cardiac contractility. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 299 (6), H2082–H2089. 10.1152/ajpheart.00511.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. F., Eltzschig H. K., Fredholm B. B. (2013). Adenosine receptors as drug targets—what are the challenges?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12 (4), 265–323. 10.1038/nrd3955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. F., Huang Z., Ma J., Zhu J., Moratalla R., Standaert D., et al. (1999). A(2A) adenosine receptor deficiency attenuates brain injury induced by transient focal ischemia in mice. J. Neurosci. 19 (21), 9192–9200. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09192.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. F., Sonsalla P. K., Pedata F., Melani A., Domenici M. R., Popoli P., et al. (2007). Adenosine A2A receptors and brain injury: broad spectrum of neuroprotection, multifaceted actions and “fine tuning” modulation. Prog Neurobiol. 83 (5), 310–331. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Epperson S., Makhsudova L., Ito B., Suarez J., Dillmann W., et al. (2004). Functional effects of enhancing or silencing adenosine A2b receptors in cardiac fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 287 (6), H2478–H2486. 10.1152/ajpheart.00217.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chern Y., Lai H. L., Fong J. C., Liang Y. (1993). Multiple mechanisms for desensitization of A2a adenosine receptor-mediated cAMP elevation in rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 44 (5), 950–958 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choukèr A., Thiel M., Lukashev D., Lukashev D., Ward J. M., Kaufmann I., et al. (2008). Critical role of hypoxia and A2A adenosine receptors in liver tissue-protecting physiological anti-inflammatory pathway. Mol Med. 14 (3-4), 116–123. 10.2119/2007-00075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruela F., Albergaria C., Soriano A., Cuffí L., Carbonell L., Sánchez S., et al. (2010). Adenosine receptors interacting proteins (ARIPs): behind the biology of adenosine signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1798 (1), 9–20. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K. L., Merkel L., Zannikos P., Kelley M. F., Boutouyrie B., Perrone M. H. (2000). AMP 579, a novel adenosine agonist for the treatment of acute myocardial Infarction. Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 18, 183–210. 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2000.tb00043.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conti A., Lozza G., Monopoli A. (1997). Prolonged exposure to 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA) does not affect the adenosine A2A-mediated vasodilation in porcine coronary arteries. Pharmacol. Res. 35 (2), 123–128. 10.1006/phrs.1996.0125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corciulo C., Lendhey M., Wilder T., Schoen H., Cornelissen A. S., Chang G., et al. (2017). Endogenous adenosine maintains cartilage homeostasis and exogenous adenosine inhibits osteoarthritis progression. Nat. Commun. 8, 15019 10.1038/ncomms15019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csóka B., Németh Z. H., Rosenberger P., Eltzschig H. K., Spolarics Z., Pacher P., et al. (2010). A2B adenosine receptors protect against sepsis-induced mortality by dampening excessive inflammation. J. Immunol. 185 (1), 542–550. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csóka B., Selmeczy Z., Koscsó B., Németh Z. H., Pacher P., Murray P. J., et al. (2012). Adenosine promotes alternative macrophage activation via A2A and A2B receptors. FASEB J. 26 (1), 376–386. 10.1096/fj.11-190934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha R. A. (2016). How does adenosine control neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration? J. Neurochem. 139 (6), 1019–1055. 10.1111/jnc.13724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha R. A., Johansson B., Constantino M. D., Sebastião A. M., Fredholm B. B. (1996). Evidence for high-affinity binding sites for the adenosine A2A receptor agonist [3H] CGS 21680 in the rat hippocampus and cerebral cortex that are different from striatal A2A receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 353 (3), 261–271. 10.1007/BF00168627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Rocha Lapa F., da Silva M. D., de Almeida Cabrini D., Santos A. R. (2012). Anti-inflammatory effects of purine nucleosides, adenosine and inosine, in a mouse model of pleurisy: evidence for the role of adenosine A2 receptors. Purinergic Signal. 8 (4), 693–704. 10.1007/s11302-012-9299-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva J. S., Gabriel-Costa D., Sudo R. T., Wang H., Groban L., Ferraz E. B., et al. (2017). Adenosine A2A receptor agonist prevents cardiac remodeling and dysfunction in spontaneously hypertensive male rats after myocardial infarction. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 11, 553–562. 10.2147/DDDT.S113289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S. S., Zhou Y. G. (2011). Adenosine 2A receptor: a crucial neuromodulator with bidirectional effect in neuroinflammation and brain injury. Rev. Neurosci. 22 (2), 231–239. 10.1515/RNS.2011.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbousset R., Delierneux C., Mezouar S., Hego A., Lecut C., Guillaumat I., et al. (2014). P2X1 expressed on polymorphonuclear neutrophils and platelets is required for thrombosis in mice. Blood. 124 (16), 2575–2585. 10.1182/blood-2014-04-571679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filippo E., Namasivayam V., Zappe L., El-Tayeb A., Schiedel A. C., Müller C. E. (2016). Role of extracellular cysteine residues in the adenosine A2A receptor. Purinergic Signal. 12 (2), 313–329. 10.1007/s11302-016-9506-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira Moreira D., Santo Neto H., Marques M. J. (2017). P2Y2 purinergic receptors are highly expressed in cardiac and diaphragm muscles of mdx mice, and their expression is decreased by suramin. J. Neural. Transm. 55 (1), 116–121. 10.1002/mus.25199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ponti C., Carini R., Alchera E., Nitti M. P., Locati M., Albano E., et al. (2007). Adenosine A2a receptor-mediated, normoxic induction of HIF-1 through PKC and PI-3K-dependent pathways in macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82 (2), 392–402. 10.1189/jlb.0107060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckert J., Nöthen M. M., Rietschel M., Wildenauer D., Bondy B., Ertl M. A., et al. (1996). Human adenosine A2a receptor (A2aAR) gene: systematic mutation screening in patients with schizophrenia. J. Neural. Transm. 103 (12), 1447–1455. 10.1007/BF01271259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalla A. K., Wong M. Y., Wang W. Q., Biaggioni I., Belardinelli L. (2006). Tachycardia caused by A2A adenosine receptor agonists is mediated by direct sympathoexcitation in awake rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 316 (2), 695–702. 10.1124/jpet.105.095323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paola R., Melani A., Esposito E., Mazzon E., Paterniti I., Bramanti P., et al. (2010). Adenosine A2A receptor-selective stimulation reduces signaling pathways involved in the development of intestine ischemia and reperfusion injury. J. Physiol. (Lond.). 33 (5), 541–551. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181c997dd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson J. G., Jr., Shea L. G., Fenton R. A. (2008). Adenosine A2A and beta-adrenergic calcium transient and contractile responses in rat ventricular myocytes. Exp. Biol. Med. 295 (6), H2364–H2372. 10.1152/ajpheart.00927.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doré A. S., Robertson N., Errey J. C., Ng I., Hollenstein K., Tehan B., et al. (2011). Structure of the adenosine A(2A) receptor in complex with ZM241385 and the xanthines XAC and caffeine. Structure. 19 (9), 1283–1293. 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury A. N., Szent-Györgyi A. (1929). The physiological activity of adenine compounds with especial reference to their action upon the mammalian heart. J. Physiol. 68 (3), 213–237. 10.1113/jphysiol.1929.sp002608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X., Ou X., Song T., Zhang W., Cong F., Zhang S., et al. (2015). Adenosine A2B receptor stimulates angiogenesis by inducing VEGF and eNOS in human microvascular endothelial cells. Exp. Biol. Med. 240 (11), 1472–1479. 10.1177/1535370215584939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy M. T., Lee M. Y., Gao Z. G., White K. L., Didenko T., Horst R., et al. (2018). Allosteric coupling of drug binding and intracellular signaling in the A2A adenosine receptor. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 172 (1-2), 68–80. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Tayeb A., Michael S., Abdelrahman A., Behrenswerth A., Gollos S., Nieber K., et al. (2011). Development of polar adenosine A2A receptor agonists for inflammatory bowel disease: synergism with A2B antagonists. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2 (12), 890–895. 10.1021/ml200189u.eCollection2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltzschig H. K., Abdulla P., Hoffman E., Hamilton K. E., Daniels D., Schönfeld C., et al. (2005). HIF-1-dependent repression of equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT) in hypoxia. J. Exp. Med. 202 (11), 1493–1505. 10.1084/jem.20050177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epperson S. A., Brunton L. L., Ramirez-Sanchez I., Villarreal F. (2009). Adenosine receptors and second messenger signaling pathways in rat cardiac fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 296 (5), C1171–C1177. 10.1152/ajpcell.00290.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esther C. R., Jr., Olsen B. M., Lin F. C., Fine J., Boucher R. C. (2013). Exhaled breath condensate adenosine tracks lung function changes in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 304 (7), L504–L509. 10.1152/ajplung.00344.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton R. A., Dobson J. G., Jr. (2007). Adenosine A1 and A2A receptor effects on G-protein cycling in beta-adrenergic stimulated ventricular membranes. J. Cell. Physiol. 213 (3), 785–792. 10.1002/jcp.21149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferré S., Casadó V., Devi L. A., Filizola M., Jockers R., Lohse M. J., et al. (2014). G protein-coupled receptor oligomerization revisited: functional and pharmacological perspectives. Pharmacol. Rev. 66 (2), 413–434. 10.1124/pr.113.008052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm B. B. (2014). Adenosine—a physiological or pathophysiological agent? Pharmacol Rev. 92 (3), 201–206. 10.1007/s00109-013-1101-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm B. B., Arslan G., Halldner L., Kull B., Schulte G., Wasserman W. (2000). Structure and function of adenosine receptors and their genes. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 362 (4-5), 364–374. 10.1007/s002100000313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm B. B., Bättig K., Holmén J., Nehlig A., Zvartau E. E. (1999). Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use. Pharmacol. Rev. 51 (1), 83–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm B. B., Chern Y., Franco R., Sitkovsky M. (2007). Aspects of the general biology of adenosine A2A signaling. Prog Neurobiol. 83 (5), 263–276. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm B. B., IJzerman A. P., Jacobson K. A., Klotz K. N., Linden J. (2001). International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 53 (4), 527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm B. B., IJzerman A. P., Jacobson K. A., Linden J., Müller C. E. (2011). International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors—an update. Pharmacol. Rev. 63 (1), 1–34. 10.1124/pr.110.003285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm B. B., Zhang Y., van der Ploeg I. (1996). Adenosine A2A receptors mediate the inhibitory effect of adenosine on formyl-Met-Leu-Phe-stimulated respiratory burst in neutrophil leucocytes. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 354 (3), 262–267. 10.1007/BF00171056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friebe D., Yang T., Schmidt T., Borg N., Steckel B., Ding Z., et al. (2014). Purinergic signaling on leukocytes infiltrating the LPS-injured lung. PLoS One. 9 (4), e95382 10.1371/journal.pone.0095382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fronz U., Deten A., Baumann F., Kranz A., Weidlich S., Härtig W., et al. (2014). Continuous adenosine A2A receptor antagonism after focal cerebral ischemia in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 387 (2), 165–173. 10.1007/s00210-013-0931-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes E., Fuentes M., Caballero J., Palomo I., Hinz S., El-Tayeb A., et al. (2018). Adenosine A2A receptor agonists with potent antiplatelet activity. Platelets. 29 (3), 292–300. 10.1080/09537104.2017.1306043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funaya H., Kitakaze M., Node K., Minamino T., Komamura K., Hori M. (1997). Plasma adenosine levels increase in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 95 (6), 1363–1365. 10.1161/01.cir.95.6.1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z. G., Jacobson K. A. (2017). Purinergic signaling in mast cell degranulation and asthma. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 947 10.3389/fphar.2017.00947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergs U., Fritsche J., Fabian S., Christ J., Neumann J. (2017). Desensitization of the human 5-HT4 receptor in isolated atria of transgenic mice. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 390 (10), 987–996. 10.1007/s00210-017-1403-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germack R., Dickenson J. M. (2005). Adenosine triggers preconditioning through MEK/ERK1/2 signalling pathway during hypoxia/reoxygenation in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 39 (3), 429–442. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover D. K., Ruiz M., Takehana K., Petruzella F. D., Riou L. M., Rieger J. M., et al. (2001). Pharmacological stress myocardial perfusion imaging with the potent and selective A(2A) adenosine receptor agonists ATL193 and ATL146e administered by either intravenous infusion or bolus injection. Circulation. 104 (10), e39919–7. 10.1161/hc3601.093983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halldner L., Lozza G., Lindström K., Fredholm B. B. (2000). Lack of tolerance to motor stimulant effects of a selective adenosine A(2A) receptor antagonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 406 (3), 345–354. 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00682-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamad E. A., Li X., Song J., Zhang X. Q., Myers V., Funakoshi H., et al. (2010). Effects of cardiac-restricted overexpression of the A(2A) adenosine receptor on adriamycin-induced cardiotoxicity. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 298 (6), H1738–H1747. 10.1152/ajpheart.00688.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamad E. A., Zhu W., Chan T. O., Myers V., Gao E., Li X., et al. (2012). Cardioprotection of controlled and cardiac-specific over-expression of A(2A)-adenosine receptor in the pressure overload. PLoS One. 7 (7), e39919 10.1371/journal.pone.0039919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haschemi A., Wagner O., Marculescu R., Wegiel B., Robson S. C., Gagliani N., et al. (2007). Cross-regulation of carbon monoxide and the adenosine A2a receptor in macrophages. J. Immunol. 178 (9), 5921–5929. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskó G., Pacher P. (2008). A2A receptors in inflammation and injury: lessons learned from transgenic animals. J. Leukoc. Biol. 83 (3), 447–455. 10.1189/jlb.0607359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskó G., Pacher P. (2012). Regulation of macrophage function by adenosine. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32 (4), 865–869. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.22685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskó G., Xu D. Z., Lu Q., Németh Z. H., Jabush J., Berezina T. L., et al. (2006). Adenosine A2A receptor activation reduces lung injury in trauma/hemorrhagic shock. Crit. Care Med. 34 (4), 1119–1125. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206467.19509.C6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]