Abstract

Through interviews the present study examined the perspectives of service providers (n = 14) in the violence against women (VAW) sector regarding risk factors and challenges in assessing risk for women experiencing domestic violence (DV) in rural locations. The present study also examined what promising practices VAW service providers are utilizing when working with women experiencing DV in rural locations. Interviews were coded and analyzed in a qualitative analysis computer program. Analysis indicated several risk factors including the location (i.e., geographic isolation, lack of transportation, and lack of community resources) and cultural factors (i.e., accepted and more available use of firearms, poverty, and no privacy/anonymity). Moreover, analyses indicated several challenges for VAW service providers assessing risk including barriers at the systemic (i.e., lack of agreement between services), organizational (i.e., lack of collaboration and risk assessment being underutilized/valued), and individual client (i.e., complexity of issues) level. However, participants outlined promising practices being implemented for rural locations such as interagency collaboration, public education, professional education, and outreach programs. The findings support other research in the field that highlight the increased vulnerability of women experiencing DV in rural locations and the added barriers and complexities in assessing risk for rural populations. Implications for future research and practice include further examination of the identified promising practices, a continued focus on collaborative approaches and innovative ways to prevent and manage risk in a rural context.

Keywords: Domestic violence, Rural, Risk factors, Risk assessment, Recommendations, Qualitative research

Introduction

Domestic violence (DV) or intimate partner violence is a global social issue that has significant short term and long term physical, emotional, and psychological repercussions on its victims (Campbell 2002; Pico-Alfonso et al. 2006). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines intimate partner violence as the use of “physical violence, sexual violence, threats of physical or sexual violence, stalking and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner” (CDC 2012). According to Statistics Canada (2019) there were over 99,000 police-reported incidents of DV in 2018. Of these incidents, the vast majority of victims (79%) were women (Statistics Canada 2019). This high rate of prevalence made DV the leading form of violence experienced by women (Statistics Canada 2019). Many factors have been identified as potentially contributing to an increased risk of experiencing DV however, women experience DV across all races, ethnicities, age, marital status, socioeconomic status, and geography (Abramsky et al. 2011).

When considering the factor of geography, much of the research on DV examines urban populations rather than rural populations. However, the rate of DV is greater amongst rural communities in comparison to urban communities (Northcott 2011). Specifically, Canadian rural populations have a risk of DV that is three times higher than urban populations (Northcott 2011). Moreover, while rural and urban populations share some similarities within specific trends of DV, perpetrators within rural settings engage in more chronic and severe DV and have higher rates of substance abuse and unemployment than perpetrators in urban settings (Edwards 2014; Logan et al. 2001). Victims of DV in rural settings also differentiate from victims in urban settings in that they experience worse psychosocial and physical health outcomes (Edwards 2014). Additionally, rural victims also face greater obstacles in accessing resources and receiving adequate support which amplifies challenges in leaving an abusive relationship (Dudgeon and Evanson 2014). While some findings suggest an increased prevalence of DV within rural settings, research investigating these trends remain fairly limited (Jeffrey et al. 2019). Further research investigating the unique variables that exist within rural populations is needed in order to understand what factors contribute to the heightened prevalence and risk of DV within these communities.

Risk Factors for Domestic Violence in Rural Locations

Risk assessments help determine the risk factors that may increase vulnerability to DV, identify the severity of abuse and provide important implications for the support of at-risk women (Campbell 2002). Existing research has indicated that rural women are confronted with unique risks, needs, and barriers that prevent them from accessing critical services (Vafaei et al. 2010). The most obvious risk factor for rural women experiencing DV is geographic distance and isolation. Geographic barriers have had a profound and direct impact on women experiencing DV in rural environments as it greatly increases victim vulnerability (Beyer et al. 2015). Geographic isolation also means greater distances between homes, being less visible to neighbours or other potential witnesses, and being further away from emergency services (Grama 2000; Logan et al. 2001). The physical isolation can also translate into social isolation, both of which can contribute to the likelihood of DV and more power and control for the perpetrator (Grama 2000; Logan et al. 2001). Furthermore, geographic isolation can also contribute to many barriers such as a lack of transportation and limited access to appropriate resources, which inherently complicates the process of leaving an abusive relationship (Faller et al. 2018). Research examining rural women’s access to healthcare services found that rural women had to travel three times farther for services than urban women (respectively, 25% of rural women vs. 1% of urban women traveled over 40 miles; Peek-Asa et al. 2011). In addition, public transit may not even be an option for many rural victims as it was only found to be available in approximately half of rural counties (Stommes and Brown 2002).

Rural DV victims also find resources are “few and far between” in comparison with urban areas (Edwards 2014; Grama 2000; Logan et al. 2001). The lack of services includes shelters, police, and courts, all of which are essential to DV victims seeking help (Sandberg 2013). Rural communities also often lack specialized services for DV that typically exist in urban communities which creates significant issues of accessibility for rural women (Forsdick Martz and Sarauer 2000). Therefore, the geographic isolation and the other factors (i.e., lack of transportation and services) intertwined with the remoteness of rural locations further enhance risk while, adversely impacting help seeking behaviors (i.e., restricting access to appropriate health care and other DV related resources; Eastman et al. 2007).

Within a rural context cultural values tend to be somewhat different in comparison to urban values. Some rural values such as cultural beliefs about religion (i.e., permanence of marriage), importance of privacy, and dominance of patriarchal attitudes may be considered problematic as they may provide a context that sanctions DV and places rural women at an increased vulnerability of DV (Anderson et al. 2014). These cultural attitudes also often discourage women from being assertive (Schwab-Reese and Renner 2017) and work to maintain and foster stigma of DV (Kitchen et al. 2012). This process becomes further complicated by the close-knit community networks that inhibit anonymity during help seeking (Kitchen et al. 2012). In fact, rural women are less likely to seek help than urban women due to the increased likelihood of victims knowing those working in the community services they are trying to access (Neill and Hammatt 2015). The lack of anonymity combined with the nature of cultural norms being often incompatible and even shaming of help-seeking behaviors further increases the likelihood of the victim remaining silent (Shannon et al. 2006).

The presence of firearms is another major risk factor in rural settings. Firearms within rural communities are often viewed as culturally acceptable and a means for carrying out community practices such as hunting and protection (Doherty and Hornosty 2008). However, an abuser’s access to firearms is considered to be the most dangerous predictor of domestic homicide even when controlling for other key risk factors (Campbell et al. 2003). For example, within Ontario firearms were used in 27% of all domestic homicides between 2002 and 2010 (DVDRC 2014). More specifically, research on domestic homicides in rural locations found that firearms were the most common weapons causing fatal injury (Beyer et al. 2013). Research specifically, investigating the use of firearms in rural populations also found that perpetrators in rural communities are more likely to make threats with a weapon and both stalk and threaten their victims with a gun in comparison to perpetrators in urban communities (Logan and Lynch 2018). The presence of firearms significantly contributes to the overall risk and vulnerability to lethal DV for women living in rural populations (Straatman et al. 2020). Therefore, risk assessment is paramount in both identifying potentially lethal situations and devising safety planning and risk management strategies that specifically address the lethal risk factors present within a rural context.

The Need for a Coordinated Community Response

The high prevalence and magnitude of the global issue of DV requires a coordinated community response (CCR) – both in rural and urban communities. However, it should be noted that the CCR model is under increased scrutiny by many communities as the criminal justice and legal system is seen as contrary to victim needs and autonomy (Buzawa and Buzawa 2017; Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence 2020). Although CCR models vary, they are increasingly emphasized as a necessary approach to address DV (Shepard et al. 2002). In general, community responses to DV include public awareness and professional training for all the agencies that play a role in helping prevent and manage DV. More specifically, a CCR may involve coordination with police, prosecutors, probation officers, victim advocates, counselors, and judges in developing and implementing policies and procedures that improve interagency coordination and lead to a more uniform response to DV (Shepard et al. 2002). Among all the services, one of the longest standing and most crucial, are specialized violence against women (VAW) services. Their services often encompass both prevention and management of DV related issues and include services such as protection planning, counselling, victim advocacy, and the most predominant community-based solution, shelters (Mantler and Wolfe 2017). The service of shelters has been growing steadily over time and has proved to be an essential resource for DV (Lehrner and Allen 2009).

Barriers for Assessing Risk in Rural Locations

There is a scarcity of literature examining the impacts of DV within rural, remote, and northern Canadian communities (Wuerch et al. 2019). However, within this research there are even fewer studies examining DV through the broad lens of community perceptions including, community service providers (Murray et al. 2015). Community service providers are a valuable source of information as they provide a unique understanding of the responses to and needs of individuals experiencing DV (Murray et al. 2015). For example, a study examining the challenges of rural and northern Saskatchewan service providers found that service providers experienced a high level of frustration with the lag in response time for accessing services, and difficulties in high staff turnover which negatively impacted their ability to build trusting relationships with the victims receiving service (Wuerch et al. 2016). Similarly, another study by Merchant and Whiting (2015) found that shelter workers within geographically diverse communities felt frustration and hopelessness with the scarcity of available DV resources which then contributed to professional burnout and even less available resources. While this research provides insights about the experiences of rural victims and the services that try to support them, there are limited studies investigating the experiences of front-line service providers especially within the context of RRN communities across Canada (Faller et al. 2018; Zorn et al. 2017). Research understanding the unique needs and barriers of victims and service providers in rural regions is critical to building safer communities that offer more effective services (Faller et al. 2018).

Purpose of Current Study

Previous literature identified significant differences in perpetrators, victim risk, DV patterns, and barriers for accessing services for RRN locations in comparison to urban locations. The current study aimed to extend the limited knowledge of rural populations by exploring the unique risk factors, challenges in risk assessment, and current promising practices for victims of DV in rural and RRN communities using qualitative interviews by key informants from VAW agencies. In gaining a deeper knowledge about the unique risk factors and barriers for individuals in rural settings, it can be better understood how to effectively manage risk and safety plan within these populations. Additionally, by gaining knowledge about the common and accepted practices of risk assessment within RRN communities, the insights about enhanced practices for this vulnerable population can be more widely shared amongst service providers. Given the past literature, which primarily investigated rural locations, the following areas are explored in the interviews covering rural and RRN communities in Ontario:

VAW service providers’ perceptions of risk factors for DV victims in rural communities.

VAW service providers’ perceptions of challenges and barriers in practicing risk assessment for rural DV victims.

VAW service providers’ opinions of current promising practices for rural communities.

Method

Overview

The present study utilizes a subset of data from an ongoing Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) funded research initiative entitled Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative for Vulnerable Populations (CDHPIVP). The goal of this initiative is to identify and understand the practices used by a variety of different social service sectors to address the unique needs/risk factors that may heighten exposure to violence and the existing barriers to effective risk assessment, risk management and safety planning. The research initiative was created with a special focus on domestic homicide prevention of four vulnerable populations: immigrants and refugees; Indigenous peoples; children exposed to DV; and rural, remote and northern populations. Rural was defined as a population less than 1000 and locations with less than 400 persons per square kilometer (Statistics Canada 2001). Remote was defined as not accessible year-round by road and Northern referred to communities that were designated by the provincial government as being the Northern part of the province (e.g., for Ontario, see http://nohfc.ca/en/about-us/northern-ontario-districts). This article is focused mainly on rural communities in Southern Ontario that would all be within a 100-mile radius of an urban center.

Procedure

The project consists of three phases: (1) a systematic literature review; (2) an online survey and interviews with professionals in the field; and (3) interviews with both survivors of severe DV and proxies. Professionals working in the area of DV were initially recruited to participate in the survey through advertisements by The CDHPIVP network. The network consists of over 50 national partners and collaborators representing all social service, policing, justice and corrections sectors across Canadian provinces and territories. As part of the last question on the survey, participants who indicated that at least part of their work focused on serving vulnerable populations were asked if they would be interested in participating in a follow up interview. The current study utilized data from the interviews in the second phase. Of the 1445 survey respondents, 370 consented to a follow-up, semi-structured interview. This study focused on a sub-sample of 14 VAW service providers from one province (Ontario).

Survey Instrument

A variety of specialists in the field of DV (front-line professionals from various service sectors and academics) collaborated in forming a comprehensive guide of 27 questions for the CDHPIVP interviews. Interview questions focused on key informants’ role in risk assessment, safety planning, and risk management. More specifically, on the procedures, policies and guidelines they followed and the access/resources they had within their role. A final three-part question was also asked regarding their work with vulnerable populations:

What are the challenges dealing with DV within these particular populations?

What are some unique risk factors for lethality among these populations?

What are some helpful promising practices being implemented among these populations?

The protocol allowed for probing questions to encourage informants to clarify and elaborate on their responses. The interviews were approximately an hour in length and were conducted by several graduate research assistants. All interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim by research assistants.

Informants for the Present Study

This study examined 14 qualitative interviews with professionals in the VAW sector in Ontario who self-identified as working with women in rural and RRN communities. The participants differed in their level of experience in the field, their roles at their respective agencies, the degree to which they worked directly with clients as part of their role, and the populations they self-identified as serving (i.e., rural or RRN). Most VAW service providers were from southern Ontario and self-identified as working with rural victims of DV (see Table 1). The roles in which they worked within the VAW sector, however, were relatively evenly split between roles in administration and front-line service providers.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of sample

| Variable |

n = 14 n (%) |

|---|---|

| Location of Agency (Region of Ontario) | |

| Southwestern | 5 (35.7) |

| Southeastern | 5 (35.7) |

| Northern | 3 (21.4) |

| Unspecified | 1 (7.1) |

| Self-identified Population Served | |

| Rural | 10 (71.4) |

| Rural, Remote, Northern | 4 (28.6) |

| Role | |

| Counsellor | 5 (35.7) |

| Manager | 1 (7.1) |

| Executive Director | 4 (28.6) |

| Transitional Support Worker | 2 (14.3) |

| Program Coordinator | 1 (7.1) |

| Outreach Worker | 1 (7.1) |

Data Analysis

Interviews were analyzed for the presence of risk factors, barriers in assessing risk, and promising practices with both a deductive and inductive approach at the semantic level (Braun and Clarke 2006). This approach allowed the analysis and interpretation of the data to draw from an established theoretical base and also remain flexible to novel themes (Joffe 2012). Thematic analysis emerged through a multi-phase process. The first step was reading and rereading all interview transcripts, notes, and reviewing the literature. Next a provisional codebook was developed and presented and discussed within a lab consisting of a group of graduate students and a principal investigator for the CDHPIVP. Then the final suitability of the codebook was determined through coding trials on a sample of three transcripts by the primary author and a graduate research assistant. The process involved independently coding the trial transcripts, comparing all excerpts coded, and deliberating the suitability of codes, other emerging themes, and the discrepancies between coders. This rendered a more refined codebook based on coding consistency and agreement toward the interpretation of interview data. The final codebook was then utilized to code all transcripts.

All verbatim de-identified transcripts were uploaded, coded, and analyzed in the qualitative analysis computer program Dedoose (Dedoose Version 8.1, 2014). The primary author completed the first cycle of coding utilizing a blend of descriptive and sub-coding to categorize data (Saldana 2012). Consultations with other qualitative researchers in the lab continued through the coding process to ensure procedures, results, and interpretations were representative and appropriate.

Results

Overview

The aim of the current study was to explore: a) what are the unique risk factors of victims experiencing DV in rural locations; b) what are the challenges and barriers for the VAW service providers in assessing risk of victims experiencing DV in rural locations; and c) what are some recommendations for enhanced practices for working with rural DV victims within the VAW sector? Numerous themes and subthemes emerged for each.

Unique Risk Factors of Victims Experiencing DV in Rural Locations

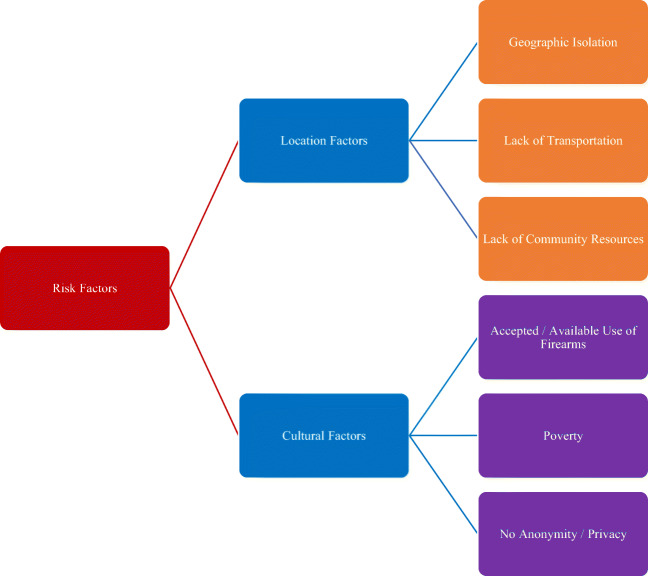

Two major themes emerged related to unique risk factors for rural victims of DV. The two overarching themes represented risk factors of location and culture. Several subthemes were found within each theme and discussed below (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Research question one: risk factors of victims experiencing DV in rural locations

Location Factors

VAW service providers identified location as a unique risk factor for rural women experiencing DV. Many VAW service providers described rural locations as, “more isolated, physically and socially” (Interviewee #11) and highlighted that, “isolation puts women at a higher risk because less people know that there is a potential for violence” (Interviewee #13). Key subthemes to emerge related to the risk factor of location included, the geographic isolation of rural environments and the limited transportation and community resources.

Geographic isolation. Most VAW service providers discussed how rural environments have physical isolation from both the world outside the community and inside the community because of the vast distance from even the closest neighbor. One VAW service provider commented on the vulnerability of increased privacy: “without having neighbors close by it could increase risk because people are not keeping their eye on you or are aware of what is going on” (Interviewee #5). Additionally, other service providers commented on the increased risk and challenges that come from being farther away from critical emergency response services, “Victims are remote and there is not a police officer, firetruck, or an ambulance for a while. Especially in the winter the issue of resources, lack of transportation, no childcare, and roads being closed are very difficult to work with” (Interviewee #4).

Lack of transportation. Many VAW service providers also commented on the challenges and risk presented from limited transportation. A lack of transportation in rural communities encompassed having no access to a vehicle, public transit, and in severely remote locations limited access to major highways or flights during the winter. One service provider described that a lack of transportation options acts as a barrier in accessing services and when compiled with other risk factors significantly impacts victim safety:

“It is not easy to leave. If a woman is on a farm, then you have geographically isolated her. A lot of men will take out spark plugs to the car or will check the odometer so she cannot come to and from an appointment without putting considerable mileage on the car. There is no transportation, there is no one to help you, you are on your own, you are isolated, you are unable to call for help, you are unable to run to the neighbors, and then there are guns.” (Interviewee #8).

Similarly, another VAW service provider specifically shared about the amplified difficulty of transportation and safety for northern rural communities, “Our North is so much different…These are not drive in communities, they are book an air charter plane to bring our women in. Safety planning is huge, but it is hard” (Interviewee #1).

Lack of community resources. Most VAW service providers also identified a lack of accessible and available community resources as a risk factor for women experiencing DV in rural communities. One VAW service provider commented on the challenges of accessible services saying,

“The biggest challenge is the lack of services because there are no services geographically close to the woman. Even in my program the women have to travel to our office and there is no public transportation in the country like within towns. It is a huge barrier if someone is living in a farm situation.” (Interviewee #8)

Similarly, another VAW service provider shared challenges in services being limited, inaccessible, and unavailable as a result of limited resources being at capacity:

“We only have one greyhound per day in each direction, and most of the time it is full. We also have no court. If a woman needs to get interim custody, we have to cross our fingers that we can safely get her on a bus, and into another shelter where they have a court.” (Interviewee #7)

Cultural Factors

VAW service providers also commented on risk factors related to the theme of culture. Many VAW service providers discussed risk factors related to some of the cultural norms, beliefs, values, and practices amongst rural communities. One VAW service provider commented on cultural beliefs saying, “A lot of rural women really believe it is their life to be good women, stay home, and put up with DV… That is her role, very traditional, and the risk of lethality is high” (Interviewee #12). Critical subthemes that further explain the risk factor of culture include accepted and more available use of firearms, poverty, and no privacy/anonymity.

Accepted and more available use of firearms. Several VAW service providers identified accepted and more available use of firearms in rural communities as a unique cultural risk factor. One VAW service provider highlighted the increased presence of firearms saying, “I ask every client does your partner own guns or weapons and its very rare that my city people would say yes. But it is very rare that my rural people would say no” (Interviewee #5). Another service provider commented on how the acceptance and availability of firearms in rural communities impacts risk,

“Rural women are definitely at a higher risk of lethality, for several reasons. They are very isolated in farming communities and the nearest neighbor might be ten miles away. A gunshot is not going to be heard and most farmers have guns.” (Interviewee #12)

Poverty. VAW service providers also discussed the risk factor of lower socioeconomic status within rural settings. Many VAW service providers commented on issues of poverty, high rates of unemployment, and a lack of affordable housing. One VAW service provider shared that challenges of poverty and a lack of affordable housing act as barriers in leaving DV:

“The economic disparity is big… Access to having an income that would adequately pay for housing and stuff for kids is limited. The inability to find housing is a huge issue around domestic violence because there are not affordable places to live, so women are returning to the situation because there is nowhere else to go.” (Interviewee #8)

Additionally, another VAW service provider discussed the amplified challenges of poverty in rural communities that are remote and northern: “Our First Nations communities are third world countries [sic]. Our women cannot even access a phone sometimes” (Interviewee #1).

No privacy/anonymity. Many VAW service providers also discussed the challenges and risk of no privacy/anonymity for women trying to access DV services in rural communities. They shared that victims often felt restricted in accessing resources due to privacy concerns and fear regarding confidentiality. One VAW service provider commented that, “access to services is huge, the stigma attached to the shelter itself, and everyone knowing everyone; we are on a main street across from the police station. If you are coming here, the world knows you are coming here” (Interviewee #7). Another service provider shared how victims’ fear of confidentiality with those in helping professions acts as barrier to help-seeking:

“A woman may not want to go to her doctor because her doctor is also the same doctor as her husband, her husband’s family, and everybody else in that community. There is always that fear that someone is going to know what is going on.” (Interviewee #9)

Although it may seem like victims should trust those in helping professions, VAW service providers discussed the challenges of personal relationships becoming entangled with professional judgement in close knit rural communities. For instance, one VAW service provider shared a hyperbolic example of the minimization of violence that can occur as a result of dual relationships and a lack of anonymity of those working within the helping profession: “Oh, that is my cousin Johnny, and I have had a long relationship with Johnny, and I know Johnny and Johnny would not do that” (Interviewee #7).

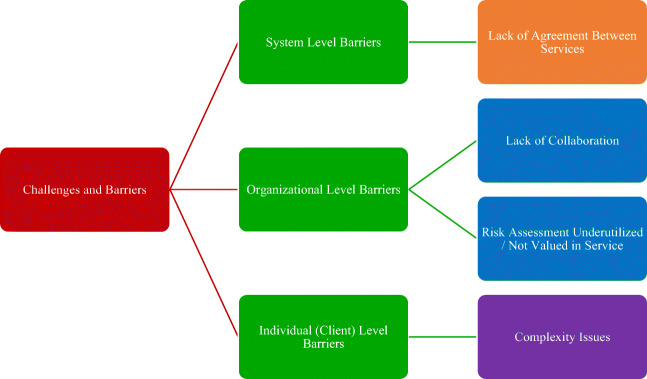

Barriers for the VAW Sector in Assessing Risk of DV Victims in Rural Locations

In the second research question, themes were categorized into three overarching levels related to barriers in assessing risk for rural DV victims. These levels were at the systemic level (i.e., community and the broader context), organizational level (i.e., within their agency), and individual client level. Several themes were identified within each level and discussed below (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Research question two: challenges and barriers for the VAW sector in assessing risk of DV victims in rural locations

System Level Barriers

Key informants’ identified barriers to risk assessment that were systemic in nature. System level barriers encompassed difficulties working within a system, conflicts that arise systemically from the profession’s position, and the flaws within the systemic structure. A key subtheme that emerged as a barrier at the systemic level were the lack of agreement between DV services.

Lack of agreement between services. Most VAW service providers discussed having a lack of agreement between services when assessing risk as a result of different perspectives, mandates, roles, and abilities. Overall there was a perception that a lack of agreement between services led to contention of the perceived appropriate actions to addressing DV. One VAW service provider shared about the challenges in assessing risk based on different perspectives held by each service:

“We have had a lot of conflicts with CAS [Children’s Aid Society] and us because they do not believe women. They do not believe that women flee, and their focus is their children. They do not listen. They do not really see that the woman is traumatized…and is hugely impacted by that, and that it then has an impact on her parenting. She can’t be the same parent as before.” (Interviewee #10)

Similarly, another VAW service provider addresses the barriers of assessing risk as the result of a lack of agreement between services regarding the tools and language used to assess risk. The VAW service provider stated:

“Everybody just gets together and there is no tool that is shared amongst the group that everybody works from. The consistency is lacking. You have police officers who may have completed the ODARA, our worker who may have completed the Mosaic, and then victim-services who may have completed something else, if they did one…There is no consistent language around where she [victim] falls in terms of risk. I like the objective tools and I want to be consistent across the board. Even in our high-risk case assessments, there are no consistent tools that are being used.” (Interviewee #12)

Organizational Level Barriers

VAW service providers also identified barriers at the organizational level. One key subtheme within this level was related to perceived procedural barriers; more specifically how the lack of collaboration with partners interferes with effective risk assessment. Another key theme included risk assessment being underutilized and valued within VAW agencies.

Lack of collaboration. Many key informants perceived there to be a barrier in effective intervention strategies due to a lack of collaboration with other services and community partners. A central theme in responses were the challenges and restrictions arising from organizational policies surrounding information sharing. One VAW service provider shared: “We do not collaborate so much with our justice partners because it challenges issues with confidentiality, and we do not sit at our local high-risk table because we are not even invited” (Interviewee #10). Another VAW service provider spoke about their agency’s challenges in collaboration and perceived different treatment as a result of being rural:

“It seems that the collaboration has evaporated. Unfortunately, when I am talking to police services because I work in a rural area it is a very different relationship than larger urban centers. They often do not know what I do and when I call with a concern that a client has, they often are not very receptive. Then with child and family services it depends on who the worker is, as to whether or not they are going to pay attention to the risk assessment or the level of risk to the family, mother, and kids.” (Interviewee #8)

Risk assessment underutilized/not valued in service. Key informants’ identified challenges and barriers related to their agency not placing a high priority on risk assessment strategies. Many VAW service providers shared that risk assessment was both underutilized and not valued within the agency and was merely perceived as either optional or meeting a basic standard. For instance, one VAW service provider spoke about their concerns regarding risk assessment being underutilized in their agency by saying,

“In our organization I would like risk assessment to be mandatory. It is not very common that a woman comes into the shelter having had a risk assessment done, and that is concerning to me! However, for a lot of the frontline staff it is time consuming and a lot of the times they will say, “Well, look she says she is not at risk.” But that is not okay for me.” (Interviewee #12)

Individual Client Level Barriers

Key informants identified individual client level barriers and challenges in assessing risk related to the receivers of services (i.e., rural women and families). A key theme that emerged within individual client level barriers were the complex nature of cases.

Complexity issues. Several VAW service providers commented toward the complex nature of cases and the many confounding aspects needing to be addressed. A central theme in responses were complex issues that go above a VAW service response including: the chronic nature of violence, addictions, mental health, and poverty. One VAW service provider spoke about the challenges in trying to address concurrent issues:

“The addictions and mental health are so bad and just being remote – the suicide is extremely high. The trauma that some of these kids are facing with CAS and being removed from homes. Everything is normalized. If you sat here and talked to one of our women and she talked about being sexually abused as a child, it is very normal.” (Interviewee #1)

Recommendations for Enhanced Practice

In exploring promising practices identified by VAW service providers, several themes emerged. However, only the four most frequently occurring themes (i.e., interagency collaboration, public education, professional education, and outreach programs) are reported (see Table 2). These themes were identified as important aspects of an effective response to DV within a rural context.

Table 2.

Recommendations for enhanced practice

| Themes | Definition |

|---|---|

| Interagency Collaboration | Fostering working relationships with other community agencies and services |

| Public Education | Promoting knowledge and awareness of DV for the public (i.e., warning signs of abuse, resources, healthy relationship programs, etc.) |

| Professional Education | Continued professional training toward the complexity of DV in rural communities including risk assessment and other VAW responses |

| Outreach Programs | Developing and implementing programs and services that eliminate or reduce barriers of geographic isolation |

Interagency Collaboration

The most common promising practice identified by VAW service providers was continued development of collaboration with other community agencies and services. One VAW service provider shared their positive outlook on interagency collaboration by saying, “A collaborative approach seems to be happening more between police, victim services, and community services. I think it is really promising because it is providing a wraparound of support for that person.” (Interviewee #5). Another service provider addressed the benefits of information sharing and consultation by saying:

“I think the situation table is helpful so that organizations are on the same page and looking at the same information. Sometimes, what we know is different from what the other agencies know. She [Victim] may have not told them the same information or may not have mentioned things that are really significant for us but may not have been as significant for her to tell CAS or the police. So, it helps with everything to be able to share our concerns and reasons.” (Interviewee #6)

One service provider also commented on the benefits of having both positive working alliances with other agencies and with the community at large:

“Relationships with the other organizations are important. Knowing people and knowing them well…we know what the expectations are, we know how they work, and they understand how we work. It is a definite plus of a small community…Even with policing, if I know a certain officer is on that does really well with women experiencing DV I am going to wait until then to make that call. Also, just the community helping. If we need something whether it is medication brought from the city, or a woman has to get to her appointment and we cannot get her on the bus, the community will help us. If we need clothing for a certain woman, we just have to put it on Facebook, and it shows up on our door. The community helps support itself.” (Interviewee #7)

Public Education

Many VAW service providers also discussed the importance of education for the public in helping to facilitate awareness and conversations around DV and safety. Education encompassed modules, trainings, classes, and courses for the public that helped in gaining further knowledge about DV, healthy relationships, conflict resolution, and more. One VAW service provider commented about the value and importance of educating children in school:

“We are getting into schools to talk to Grade 10 students about safe and healthy relationships. I think that is another way in to talk about safety. We have become more aware of the need for that conversation and to always keep bringing it to the forefront with women. We talk a lot more about it because…women have been murdered, and now we try to bring it to everyone’s consciousness that they need to think of safety and be aware of it.” (Interviewee #13)

Another service provider spoke about the importance of educating both the mothers and children effected by DV; they described a program they specifically created for this topic:

“The purpose of the program is to address the whole idea of safety and understanding of what abuse is and the emotions tied to those things. The hope is that away from the group the mom and the kid both have an understanding and will talk together about what they learned. We are trying to bring everybody together about these issues so that they are each well aware of the concerns, how they are feeling, and the potential for danger.” (Interviewee #13)

Professional Education

Another theme VAW service providers highlighted as important was the practice of professional education. Many VAW service providers identified and discussed the need for professional education for DV within a rural context. For instance, one service provider commented on the need to be aware of rural risk factors and to adapt a safety plan accordingly:

“We would consider the isolation piece and needing to explore that a little differently. It is difficult because victims are really isolated, and…it is harder to run to a neighbor’s house if needed…You have a long driveway that no one is going to see you coming down so being mindful of those things. How we make a safety plan with someone in an urban setting does not apply the same to rural settings.” (Interviewee #10)

Similarly, another VAW service provider spoke about the need for professional education within a rural context to help facilitate better understanding and compassion from workers:

“Anything I can do to send our staff to trainings to help them understand about traditional rural ways, Aboriginal families, and residential schools, I do. I really try to keep the staff updated so that they have that perspective, knowledge, and maybe a different form of compassion.” (Interviewee #1)

Additionally, another VAW service provider addressed the importance of being educated about how intersectionality impacts risk factors by saying:

“I think that our risk assessment tools are getting better. When we look at things like intersectionality, it is huge being able to be educated in knowing what all the risk factors are. For example, what is the women’s life like, if she is working at McDonalds, has recently immigrated, and is also living on a farm.” (Interviewee #8)

Outreach Programs

The final theme that emerged from the data was the promising practice of outreach programs. VAW service providers described a variety of services which helped close gaps and mitigate issues of geographic isolation. One service provider shared how their model had been adapted to mitigate issues of transportation and isolation:

“We have changed our model because our model has always been that women come to us for service…Now our staff person goes to them to try to break down some of those barriers and…she meets with clients in the community and at their home, making sure there is no safety risks. The goal through this is to reduce some of those barriers.” (Interviewee #10)

Another service provider also spoke about the benefits of using technology to eliminate barriers to service and maintain positive helping relationships: “We have video conferencing here at the shelter. If a woman comes from an isolated area but has an established relationship with a mental health counsellor there, they can link up through video conferencing” (Interviewee #7).

Discussion

The literature pertaining to risk factors for victims in RRN communities is limited within a Canadian context (Wuerch et al. 2019). The current study addressed the risk factors and challenge’s women in rural locations experience when seeking help from the perspective of VAW service providers who support them. The results highlight the additional considerations in risk assessment and providing effective support for women experiencing DV in rural communities. A qualitative analysis of interviews from VAW service providers suggested that there are a multitude of risk factors and barriers to assessing risk for rural DV victims as well as some valuable recommendations to improve support.

Overall risk factors were identified as relating to both location and culture. Risk factors related to the location of rural communities included geographic isolation, lack of transportation, and a lack of community resources. Furthermore, risk factors related to the culture of rural communities included accepted and more available use of firearms, poverty, and lack of privacy/anonymity. Additionally, barriers were identified at the individual client, organization (i.e., VAW agencies), and system level. The individual client level barriers included complexity issues. The organizational level barriers included both a lack of collaboration and risk assessment being underutilized/valued, and the systemic level barriers included a lack of agreement between services. VAW service providers’ suggestions for enhanced practices in serving women in rural communities focused on interagency collaboration, public education, professional education, and outreach programs.

The results of this study are consistent with other research that addresses the added complexity and risk for DV victims in rural communities. Recent literature on rural service providers identified that service providers frequently cite struggles with the isolation of rural communities and how isolation leads to further issues of less available and accessible services (Faller et al. 2018). These factors complied with other risk factors, poverty, no anonymity from service providers, and a fear of stigma act as significant barriers in leaving and accessing support services (Faller et al. 2018; Wuerch et al. 2019; Zorn et al. 2017).

The results of this study also align well with the previous literature on the increased presence of guns and gun culture in rural communities (Blocher 2013; Pew Research Center 2014). Firearms have shown to be strongly linked to domestic homicide (Campbell et al. 2007) and the perception of service providers in this study continue to support the awareness that the availability of firearms is a lethal risk factor for rural DV victims (Lynch and Logan 2020). The identification of risk factors such as firearms are critical for determining the level of risk and the appropriate intervention required to address it (Ontario Domestic Violence Death Review Committee 2017).

The views of VAW service providers in this study regarding barriers to assessing risk also align with the views of rural service providers in previous research. In examining issues of inter-agency collaboration, Eastman et al. (2007) shared that many rural service providers from different sectors shared frustration based on their perception that other sectors and service providers failed to understand the dynamics of DV. VAW service providers in the current study shared a similar perception that a lack of consistency and agreement across services exists and negatively impacts DV response. Service providers in the current study also expressed a lack of collaboration and spoke to concerns with confidentiality between agencies and sectors. Similarly, rural service providers in previous research addressed issues of frequent disconnection of information and issues of “red tape” when collaborating (Faller et al. 2018). These findings suggest a need for a more CCR to DV as well as a need for direction on how different tools used within multiple agencies can be coordinated to develop a focused assessment of risk (Messing 2019; Post et al. 2010). The findings also suggest the need to decrease administrative barriers in order to improve how victims of domestic violence connect with support services and organizations (Moynihan et al. 2015). VAW service providers in the current study also shared that the interactions with other service sectors greatly varied depending on which worker they were trying to collaborate with. While, this may be the result of many different factors it does seem to suggest a need for service providers to have adequate and appropriate training (Campbell et al. 2016).

Other studies have proposed rural service provider’s perceptions of agency level issues of inadequate training, difficulty accessing training, and the difficulty of finding relevant training for rural communities (Eastman et al. 2007; Faller et al. 2018; Zorn et al. 2017). However, no research has reported the perception that rural service providers (i.e., VAW) feel risk assessment is underutilized and valued. The current study adds to knowledge in the area of rural service provider’s perspectives by acknowledging that risk assessment was often not mandatory or prioritized at an organizational level within the VAW service sector. It may be possible that the issues previously outlined by other rural service providers (i.e., inadequate training, difficulty accessing training, and difficulty finding relevant training for rural communities; Eastman et al. 2007; Faller et al. 2018; Zorn et al. 2017) contribute to VAW agencies perceptions that risk assessment is not a valuable or accessible form of assessing risk within rural communities and therefore, remains underutilized.

This study supports many of the growing efforts within the field of DV prevention and intervention. While the findings highlighted VAW service providers’ perception of a lack of DV resources and collaboration they also acknowledged the existing resources and interagency collaboration as a real asset. These findings may seem counterintuitive however, similar findings have been identified in past research. Faller et al. (2018) suggest that these contrasting opinions of service providers highlight that while there are positive existing resources within rural communities there is also the absence of resources; these resources likely exist between the two extremes which are either incomplete or inaccessible. These challenges emphasize the need for more services and the importance of a CCR to DV (Post et al. 2010; Wuerch et al. 2019).

Similarly, this study’s findings of recommendations of outreach programs, public education, and professional education are also consistent with the recommendations of previous literature (Faller et al. 2018; Wuerch et al. 2019). The practice of education for issues of violence has long been established and has often resulted in programs promoting healthy relationships, homes, and communities. Public education also encompasses school prevention programs such as the Physical and Health Education program implemented by the Fouth R, which has shown to decrease the likelihood of dating violence and promote healthy relationships (Wolfe et al. 2009). Education also encompasses professional education such as training for service providers which has remained a major recommendation in many Domestic Violence Death Review Committee (DVDRC) reports (Dawson 2017). The current findings and previous literature on the recommendation of education suggest the importance of knowledge translation from research to actual programs and campaigns supporting public and professional education (Larrivée et al. 2012; Storer et al. 2013).

Limitations

This study is limited in that the authors did not address the differences between communities that are rural and those that are considered remote and northern. The majority of participants were from southern Ontario, which decreases the generalizability of results for other provinces and areas that may be further away from urban centers, have even less resources, and slower response times. In addition, the study participants volunteered and therefore may be unique in that they may represent individuals with strong positive or negative opinions. Another limitation was having VAW service providers self-identify which population they served. However, in order to categorize the data using concrete definitions of rural, remote, and northern many challenges were presented: not wanting to disclose easily identified locations, working in locations that are not rural but encountering rural clients due to being the closest resource, outreach work that has no single location, and service providers sharing split time between multiple main and satellite offices. Participants may hold different concepts of what they consider rural, remote, and/or northern. For example, a rural area 2 h away from an urban center is much different than a remote northern community that is inaccessible by road for most of the year. The study also did not address other critical variables such as the intersectionality of rural communities and rural victims experiencing DV. For example, rural DV victims may also be Indigenous, especially when examining rural communities that are northern and remote in nature. Therefore, there are limits in our ability to generalize findings to other RRN communities and beyond the broad themes presented. We recognize the need for future research to be more specific about the definitions of rurality and do justice to the unique circumstances of victims and service providers as outlined by other scholars (Zorn et al. 2017).

Implications and Future Directions

This study also has several important implications. The study reinforces the need to close the gap between the most recent production of research and the utilization of the findings by practitioners (Larrivée et al. 2012; Storer et al. 2013). While research has highlighted the added complexities of geographic isolation for rural DV victims it appears that the actual implementation of these practical solutions still remains slow to progress (Larrivée et al. 2012). The study suggests the need to continue developing and implementing additional services that address the risk factors and challenges faced by victims in rural communities (i.e., outreach programs; Jeffrey et al. 2019). The impact of COVID-19 has made remote work even more critical for rural communities and has required ongoing creativity to reach the most vulnerable victims of DV (Moffitt et al. 2020). Furthermore, the study highlights the need both for more research on risk assessment implementation within a rural context (Wuerch et al. 2019) and risk assessment tools that address the diverse community and limited resources. In similar vein, research and case studies suggest interventions for rural DV victims may also require more unique safety planning and risk management strategies compared to victims in urban populations (Jeffrey et al. 2019; Straatman et al. 2020).

Of the rural risk factors discussed in this study the most lethal and therefore debatably the most critical risk factor requiring further consideration is firearms. Despite this, research and interventions to prevent firearm-related injuries and death in Canada lag far behind less lethal risks (Gomez et al. 2020). While policies aiming to restrict an abusers’ access to firearms do exist unfortunately, they do not guarantee effective enforcement or implementation (Lynch and Logan 2018). Further research may benefit from investigating the procedures of gun related protective orders in rural communities to gain an understanding of how frequent and consistently orders of gun confiscation are part of a protective order, and what following efforts are made to implement gun confiscation (Lynch and Logan 2020). This knowledge could provide important insights regarding how to address responses to gun violence within the rural context for professionals, policy makers, and the community at large.

Future practitioners need not only to be informed of the risk factors and barriers facing rural communities but to modify and adapt services, risk assessment and safety planning for lethal risk factors. For example, service providers need to focus on the development of safety planning that addresses women being threatened and harmed with firearms (Lynch and Logan 2018). Future practitioners may address these challenges by continuing to foster their communication and coordination of rural risk factors across agencies and sectors. Enhanced collaboration and communication between DV sectors within a rural context creates a more effective circle of care that simultaneously reduces critical barriers such as transportation (Potts 2011). Future research should continue to explore the presence of rural risk factors and the practices implemented by victims and services to mitigate lethality. For example, in addressing the risk of firearms research should investigate specifically how rural communities can successfully implement procedures restricting abusers’ access to guns (Lynch and Logan 2018).

Future research should also continue to further explore the differences between rural and RRN communities given the contextual variability that exists (Sandberg 2013). Additionally, future research should also look to examine the risk factors and barriers in assessing risk for DV victims within an intersectional analysis such as Indigenous populations where RRN challenges may overlap and are amplified by racism and historical oppression. Research efforts will benefit from adding the voices of survivors on their rural context in addition to the perspective of experts and front-line professionals in hopes of continuing to further promote effective community responses to DV within rural communities.

Funding

The research on which this article is based was supported by the Partnership Grant Program of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Grant 895–2015-1025.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicting of Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abramsky, T., Watts, C. H., Garcia-Moreno, C., Devries, K., Kiss, L., Ellsberg, M., & Heise, L. (2011). What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 109–109. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Anderson KM, Renner LM, Bloom TS. Rural women’s strategic responses to intimate partner violence. Health Care for Women International. 2014;35(4):423–441. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2013.815757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer KM, Layde PM, Hamberger KL, Laud PW. Characteristics of the residential neighborhood environment differentiate intimate partner femicide in urban versus rural settings. The Journal of Rural Health. 2013;29:281–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2012.00448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer K, Wallis AB, Hamberger LK. Neighborhood environment and intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2015;16(1):16–47. doi: 10.1177/1524838013515758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blocher J. Firearm localism. Yale LJ. 2013;123:82. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buzawa, E. S., & Buzawa, C. G. (2017). The evolution of the response to domestic violence in the United States. In: Global responses to domestic violence (pp. 61–86). Springer, Cham. 10.1007/978-3-319-56721-1_4.

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. C., Webster, D., Koziol-McLain, J., Block, C., Campbell, D., Curry, M. A., ... & Sharps, P. (2003). Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: Results from a multisite case control study. American Journal of Public Health, 93(7), 1089–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Campbell JC, Glass N, Sharps PW, Laughon K, Bloom T. Intimate partner homicide: Review and implications of research and policy. Trauma, Abuse, & Neglect. 2007;3:246–249. doi: 10.1177/1524838007303505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M., Hilton, N. Z., Kropp, P. R., Dawson, M., Jaffe, P. (2016). Domestic Violence risk assessment: Informing Safety Planning & Risk Management. Domestic homicide brief (2). London, ON: Canadian domestic homicide prevention initiative. Retrieved from: http://cdhpi.ca/sites/cdhpi.ca/files/Brief_2_Final_2.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Understanding Intimate Partner Violence (Fact Sheet 2012). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/IPV_Factsheet-a.pdf.

- Dawson, M. (Ed). 2017. Domestic Homicides and Death Reviews: An International Perspective. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dedoose Version 8.1, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data (2014). Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC (www.dedoose.com).

- Doherty D., & Hornosty, J. (2008). Exploring the links: Firearms, family violence and animal abuse in rural communities. Final research report to the Canadian firearms Centre, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and public safety Canada. Retrieved from http://www.legal-info-legale.nb.ca/en/uploads/file/pdfs/Family_Violence_Firearms_Animal_Abuse.pdf

- Dudgeon A, Evanson TA. Intimate partner violence in rural U.S. areas: What every nurse should know. American Journal of Nursing. 2014;114:26–35. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000446771.02202.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman BJ, Bunch SG, Willams AH, Carawan LW. Exploring the perceptions of domestic violence service providers in rural localities. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(7):700–716. doi: 10.1177/1077801207302047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM. Intimate partner violence and the rural-urban-suburban divide: Myth or reality? A critical review of the literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2014;16:359–373. doi: 10.1177/1524838014557289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller, Y. N., Wuerch, M. A., Hampton, M. R., Barton, S., Fraehlich, C., Juschka, D., Milford, K., Moffitt, P., Ursel, J., & Zederayko, A. (2018). A Web of Disheartenment With Hope on the Horizon: Intimate Partner Violence in Rural and Northern Communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence.10.1177/0886260518789141. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Forsdick Martz D, Sarauer DB. Domestic violence and the experiences of rural women in east Central Saskatchewan. Muenster: The Centre for Rural Studies and Enrichment; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez D, Saunders N, Greene B, Santiago R, Ahmed N, Baxter NN. Firearm-related injuries and deaths in Ontario, Canada, 2002–2016: A population-based study. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2020;192(42):E1253–E1263. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grama JL. Women forgotten: Difficulties faced by rural victims of domestic violence. American Journal of Family Law. 2000;14(3):173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey N, Johnson A, Richardson C, Dawson M, Campbell M, Bader D, Fairbairn J, Straatman AL, Poon J, Jaffe P. Domestic Violence and homicide in rural, remote, and northern communities: Understanding risk and keeping women safe. Domestic Homicide (7) London: Canadian Domestic Homicide Prevention Initiative; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Joffe H. Thematic analysis. Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: A guide for students and practitioners. 2012;1:210–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen P, Williams A, Chowhan J. Sense of community belonging and health in Canada: A regional analysis. Social Indicators Research. 2012;107(1):103–126. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9830-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larrivée MC, Hamelin-Brabant L, Lessard G. Knowledge translation in the field of violence against women and children: An assessment of the state of knowledge. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(12):2381–2391. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrner A, Allen NE. Still a movement after all these years?: Current tensions in the domestic violence movement. Violence Against Women. 2009;15(6):656–677. doi: 10.1177/1077801209332185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Lynch KR. Dangerous liaisons: Examining the connection of stalking and gun threats among partner abuse victims. Violence and Victims. 2018;33:399–416. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.v33.i3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Walker R, Leukefeld CG. Rural, urban influenced, and urban differences among domestic Violence arrestees. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16(3):266–283. doi: 10.1177/088626001016003006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch KR, Logan TK. “You better say your prayers and get ready”: Guns within the context of partner abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2018;33(4):686–711. doi: 10.1177/0886260515613344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch KR, Logan TK. Implementing domestic violence gun confiscation policy in rural and urban communities: Assessing the perceived risk, benefits, and barriers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2020;35(21–22):4913–4939. doi: 10.1177/0886260517719081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantler, T., & Wolfe, B. (2017). A rural shelter in Ontario adapting to address the changing needs of women who have experienced intimate partner violence: a qualitative case study. Rural & Remote Health, 17. 10.22605/RRH3987. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Merchant LV, Whiting JB. Challenges and retention of domestic violence shelter advocates: A grounded theory. Journal of Family Violence. 2015;30:467–478. doi: 10.1007/s10896-015-9685-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Messing JT. Risk-informed intervention: Using intimate partner violence risk assessment within an evidence-based practice framework. Social Work. 2019;64(2):103–112. doi: 10.1093/sw/swz009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, P., Aujla, W., Giesbrecht, C. J., Grant, I., & Straatman, A. L. (2020). Intimate partner Violence and COVID-19 in rural, remote, and northern Canada: Relationship, Vulnerability and Risk. Journal of Family Violence, 1–12. 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moynihan D, Herd P, Harvey H. Administrative burden: Learning, psychological, and compliance costs in citizen-state interactions. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2015;25(1):43–69. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muu009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CE, Horton GE, Johnson CH, Notestine L, Garr B, Pow AM, Flasch P, Doom E. Domestic violence service providers’ perceptions of safety planning: A focus group study. Journal of Family Violence. 2015;30:381–392. doi: 10.1007/s10896-015-9674-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neill KS, Hammatt J. Beyond urban places: Responding to intimate partner violence in rural and remote areas. Journal of Forensic Nursing. 2015;11(2):93–100. doi: 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northcott M. Domestic violence in rural Canada. Victims of Crime Research Digest. 2011;4:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Domestic Violence Death Review Committee (Ontario DVDRC). (2014). Domestic Violence Death Review Committee 2012 annual report. Toronto, ON: Office of the Chief Coroner.

- Ontario Domestic Violence Death Review Committee (Ontario DVDRC). (2017). 2016 Annual Report to the Chief Coroner. Toronto, ON: Office of the Chief Coroner

- Peek-Asa C, Wallis A, Harland K, Beyer K, Dickey P, Saftlas A. Rural disparity in domestic violence prevalence and access to resources. Journal of Women's Health. 2011;20(11):1743–1749. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2014). Pew research center 2014 political polarization and typology survey final topline. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/wpcontent/uploads-/sites/4/2014/06/2014-Polarization-Topline-for-Release.pdf.

- Pico-Alfonso MA, Garcia-Linares MI, Celda-Navarro N, Blasco-Ros C, Echeburúúa E, Martinez M. The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women's mental health: Depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. Journal of Women's Health. 2006;15(5):599–611. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post LA, Klevens J, Maxwell CD, Shelley GA, Ingram E. An examination of whether coordinated community responses affect intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25(1):75–93. doi: 10.1177/0886260508329125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts, G. G. (2011). The strategic and community safety response to domestic violence in a rural area (unpublished doctoral dissertation). Northumbria University, Newcastle, UK. Retrieved from http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/7264/1/potts.gordon_phd.pdf.

- Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg L. Backward, dumb, and violent hillbillies? Rural geographies and intersectional studies on intimate partner violence. Affilia. 2013;28(4):350–365. doi: 10.1177/0886109913504153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab-Reese L, Renner L. Attitudinal acceptance of and experiences with intimate partner Violence among rural adults. (original article) (report) Journal of Family Violence. 2017;32(1):115–123. doi: 10.1007/s10896-016-9895-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon L, Logan TK, Cole J, Medley K. Help-seeking and coping strategies for intimate partner violence in rural and urban women. Violence and Victims. 2006;21(2):167–181. doi: 10.1891/vivi.21.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard MF, Falk DR, Elliott BA. Enhancing coordinated community responses to reduce recidivism in cases of domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17(5):551–569. doi: 10.1177/0886260502017005005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2001). Rural and small town Canada: Analysis bulletin. Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 21–006-XIE. Ottawa, ON. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/21-006-x/21-006-x2001003-eng.pdf.

- Statistics Canada. (2019). Section 2: Police-reported intimate partner violence in Canada, 2018. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002x/2019001/article/00018/02-eng.htm

- Stommes, E. S. & Brown, D. M. (2002). Transportation in rural America: Issues for the 21st century. Rural America, 16(4), 2–10.

- Storer HL, Lindhorst T, Starr K. The domestic violence fatality review: Can it mobilize community-level change? Homicide Studies. 2013;17(4):418–435. doi: 10.1177/1088767913494202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straatman, A. L., Doherty, D., & Banman, V. (2020). Domestic homicides in rural communities: Challenges in accessing resources. In Jaffe, P, Scott, K, & Straatman, A.L. (Eds). Preventing domestic homicides: Lessons learned from tragedies. (pp. 39–61). Cambridge: Academic Press.

- Vafaei A, Rosenberg MW, Pickett W. Relationships between income inequality and health: A study on rural and urban regions of Canada. Rural and Remote Health. 2010;10:1430–1430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (2020, June 30). Moment of truth statement of commitment to black lives matter. Retrieved from https://wscadv.org/news/moment-of-truth-statement-of-commitment-to-black-lives/

- Wolfe DA, Crooks C, Jaffe P, Chiodo D, Hughes R, Ellis W, Stitt L, Donner A. A school-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence: A cluster randomized trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(8):692–699. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuerch, M. A., Zorn, K. G., Juschka, D., & Hampton, M. R. (2016). Responding to intimate partner violence: Challenges faced among service providers in northern communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. 10.1177/0886260516645573. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wuerch M, Zorn K, Juschka D, Hampton M. Responding to intimate partner Violence: Challenges faced among service providers in northern communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2019;34(4):691–711. doi: 10.1177/0886260516645573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorn K, Wuerch M, Faller N, Hampton M. Perspectives on regional differences and intimate partner Violence in Canada: A qualitative examination. Journal of Family Violence. 2017;32(6):633–644. doi: 10.1007/s10896-017-9911-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]