Key Points

Question

Is proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use associated with risk of asthma in children?

Findings

This propensity score–matched cohort study included 80 870 pairs of children who were and were not new users of PPIs. The incidence rate of asthma was 21.8 per 1000 person-years among those who initiated PPI use and 14.0 per 1000 person-years among those who did not; the hazard ratio increased by 57%.

Meaning

These findings suggest that asthma is one of several potential adverse events that should be considered when prescribing PPIs to children.

This cohort study investigates the association between initiating use of proton pump inhibitors and the risk of asthma in children.

Abstract

Importance

The use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in children has increased substantially in recent years, concurrently with emerging concerns that these drugs may increase the risk of asthma. Whether PPI use in the broad pediatric population is associated with increased risk of asthma is not known.

Objective

To investigate the association between PPI use and risk of asthma in children.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nationwide cohort study collected registry data in Sweden from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2016. Children and adolescents 17 years or younger were matched by age and propensity score into 80 870 pairs of those who initiated PPI use and those who did not. Data were analyzed from February 1 to September 1, 2020.

Exposures

Initiation of PPI use.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary analysis examined the risk of incident asthma with a median follow-up to 3.0 (interquartile range, 2.1-3.0) years. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs).

Results

Among the 80 870 pairs (63.0% girls; mean [SD] age, 12.9 [4.8] years), those who initiated PPI use had a higher incidence rate of asthma (21.8 events per 1000 person-years) compared with noninitiators (14.0 events per 1000 person-years), with an HR of 1.57 (95% CI, 1.49-1.64). The risk of asthma was significantly increased across all age groups and was highest for infants and toddlers with an HR of 1.83 (95% CI, 1.65-2.03) in the group younger than 6 months and 1.91 (95% CI, 1.65-2.22) in the group 6 months to younger than 2 years (P < .001 for interaction). The HRs for individual PPIs were 1.64 (95% CI, 1.50-1.79) for esomeprazole, 1.49 (95% CI, 1.25-1.78) for lansoprazole, 1.43 (95% CI, 1.35-1.51) for omeprazole, and 2.33 (95% CI, 1.30-4.18) for pantoprazole. In analyses of the timing of asthma onset after PPI initiation, the HRs were 1.62 (95% CI, 1.42-1.85) for 0 to 90 days, 1.73 (95% CI, 1.52-1.98) for 91 to 180 days, and 1.53 (95% CI, 1.45-1.62) for 181 days to end of follow-up. The association was consistent through all sensitivity analyses, including high-dimensional propensity score matching (HR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.41-1.55).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, initiation of PPI use compared with nonuse was associated with an increased risk of asthma in children. Proton pump inhibitors should be prescribed to children only when clearly indicated, weighing the potential benefit against potential harm.

Introduction

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are first-line therapy for acid-related gastrointestinal tract disorders in children. The use of PPIs has increased substantially in the last decade.1 Off-label use2 and prolonged use3 are relatively common despite limited data supporting the safety of PPI use in children. Emerging observational data, primarily derived from studies of drug use in pregnancy, indicate that exposure to PPIs may be associated with subsequent development of asthma.4,5,6 Asthma in children is a critical public health issue; approximately 14% of children have asthma globally,7 imposing an increasing burden on use of health care resources and expenditures.8 Dysbiosis and disturbance of the human microbiome is known to provoke asthma flares,9 and PPIs have been reported to alter gut and lung microbiomes through inhibition of gastric acid secretion.10 However, we are only aware of 1 cohort study11 that has examined the risk of asthma associated with PPI use in pediatric patients. The study focused on infants exposed to PPIs in the first 6 months of life and reported an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 1.41 (95% CI, 1.31-1.52). Whether PPI use in the broad pediatric population is associated with risk of asthma is not known. We herein aimed to investigate the association between PPI use among children and adolescents aged 0 to 17 years (hereinafter referred to as children) and the risk of asthma by conducting a nationwide register-based cohort study in Sweden, implementing a propensity score–matched new user design.

Methods

Data Sources

We conducted a cohort study (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The study data were captured from mandatory Swedish registers that cover nationwide health care and administrative records. All individuals were deidentified, and all registers were cross-linked by using a commonly anonymous indicator. The National Patient Register contains complete records of disease diagnoses and surgical procedures from all inpatient and outpatient hospital and emergency department encounters. The Prescribed Drug Register collects data on medications dispensed at all pharmacies in Sweden, including drug name, dispensing date, and drug amount. The Total Population Register and Statistics Sweden provides details on demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm, Sweden, which did not require informed consent because this was a registry-based study. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Cohort

The source population consisted of all children in Sweden who were younger than 18 years at some point from January 1, 2007, to June 30, 2016. From the source population, we identified all children who initiated PPI use, defined as patients prescribed their first PPI during the study period and who had no PPI prescription in the year prior. The PPI dispensing date served as the index date. Specific PPIs included omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole, and rabeprazole (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The cohort was established through a 2-step matching process, which was aimed at selecting appropriate comparators (those who did not initiate use) from the source population. In the first step, we matched each child who initiated PPI use to as many as 30 children who did not, identified from individuals in the source population of the same age (ie, the interval in days from birthdate and index date was the same) who were alive on the PPI index date. All identified children who did not initiate use, matched to a given child who initiated PPI use, were assigned the same index date as this child. In the second step, for inclusion in the final analytical cohort, those who initiated PPI use and those who did not were matched (1:1 ratio) based on propensity score and age group using 2-year bands. Patients with history of asthma, defined as a diagnosis of asthma within 5 years before the index date or a prescription for an asthma medication within 1.5 years before the index date, were excluded. Additional exclusion criteria were interstitial lung disease, emphysema, bronchiectasis, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, congenital lung malformation, and primary immunodeficiency disease before the index date; pneumonia within 3 months before the index date; liver failure; and use of histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) within 1 year before the index date (definitions in eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Outcome

The primary outcome was incident asthma, defined as a first diagnosis of asthma (primary or secondary diagnosis) captured from hospital records and specialist outpatient care or 2 or more independent prescriptions for any asthma medication12 filled within 90 days (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Date of asthma occurrence was set as the date of asthma diagnosis or the date of first dispensing of asthma medication, whichever came first. Our outcome definition was modified from a register-based validation study in Sweden,13 which reported positive predictive values of 75% for patients aged 0 to 4.5 years and 94% for those older than 4.5 to 17.0 years for asthma diagnosis and 68% and 89%, respectively, for dispensing of asthma medication.

Propensity Score

We conducted propensity score matching to control for potential confounding. The propensity score was derived by using multivariable logistic regression based on all covariates listed in eTable 1 in the Supplement, including patient demographic and socioeconomic characteristics measured at the index date, comorbidities in the 2 years before the index date, and use of health care resources and co-medications in the year before the index date. Each child who initiated PPI use was matched to a child who did not based on propensity score and age group (in 2-year age bands) by using the greedy nearest-neighbor matching algorithm without replacement, with a caliper of 0.2 SDs of the logit of the propensity score.14 The absolute mean standardized difference was used to assess covariate balance between the 2 groups; a covariate was considered well balanced if the standardized difference was less than 10%.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from February 1 to September 1, 2020. We followed up the final analytical cohort from the day after the cohort entry date until a first asthma event or censoring at the end of the follow-up period (3 years), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease diagnosis, emigration, death, or the end of the study period (December 31, 2016), whichever occurred first. We computed incidence rates and absolute risk difference in incidence with 95% CIs based on Poisson regression. Cox proportional hazards regression was performed to estimate HRs with 95% CIs, with days since the start of follow-up as the underlying time scale. We assessed the proportional hazards assumption by performing the Wald test on the interaction between treatment status and time. All analyses were performed in SAS Enterprise Guide, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). A 95% CI that did not overlap 1.00 and 2-tailed P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Secondary Analyses

Four secondary analyses were conducted. First, we analyzed the 2 modes of the primary outcome definition separately (diagnoses and prescriptions). Next, to delineate the potential latency between PPI initiation and asthma, we assessed the timing of the asthma event, categorizing the time since initiation of PPI use into 3 groups (90 days or less, 91 to 180 days, and 181 days or longer). Further, we performed an analysis of individual PPIs, for which we created mutually exclusive matched subcohorts according to individual PPI at index date and drug-specific propensity scores. The fourth analysis investigated the risk of asthma according to cumulative duration of PPI use. The duration of PPI use was calculated based on the total amount of dispensed drug, regarding patients as continuously treated as long as they continued refilling prescriptions. Accounting for irregularities and gaps in continuous treatment, refill gaps were permitted to 50% of the duration of the preceding dispensing. For each individual, we summed the durations during follow-up in a time-dependent manner, categorizing duration into 3 groups (30 days or less, 31 to 364 days, and 365 days or longer) and analyzed the risk of asthma for the full 3-year follow-up period for each category.

Subgroup Analyses

We conducted 7 subgroup analyses in which Cox proportional hazards regression models with an interaction term were applied to test whether the risk of asthma varied across baseline characteristics. The predefined subgroups were age groups with 5 categories and comorbidities including atopic disease; lower respiratory tract infection; gastroesophageal reflux disease; and comedication use, including analgesics, systemic antibiotics, and systemic corticosteroids (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Sensitivity Analyses

To assess the robustness of study findings, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses. First, we examined potentially more specific definitions of the primary outcome: (1) primary diagnosis of asthma or 2 asthma drug prescriptions within 90 days, (2) primary diagnosis of asthma or 2 asthma drug prescriptions within 60 days, (3) diagnosis of asthma plus an asthma drug prescription within 60 days of the diagnosis, and (4) given that short-acting inhaled bronchodilators might be prescribed for children to relieve transient wheezing or asthmalike symptoms, removal of short-acting inhaled bronchodilators from the primary outcome definition. Second, because discontinuation of PPI therapy is recommended 2 to 12 weeks of empirical therapy for major indications in children15,16,17 (although longer duration of use is not uncommon in clinical practice3), we used an as-treated analysis in which we censored follow-up at discontinuation of PPI treatment and switch to or addition of H2RAs, in addition to the censoring criteria mentioned above. Third, to rule out inclusion of patients with prevalent asthma, we extended the look-back for exclusion of asthma diagnosis and use of asthmatic drugs before the index date using all available data. Fourth, we restricted the analysis to patients who received PPI monotherapy at the index date and did not have any prescription for antibiotics for Helicobacter pylori eradication (clarithromycin, amoxicillin, metronidazole, or tetracycline hydrochloride) within 30 days before or after the index date. Fifth, we assessed asthma risk with a maximum 1-year follow-up period. Sixth, we assessed the risk of asthma in patients who initiated H2RA treatment compared with those who did not by repeating the same algorithm as in the primary study, because H2RAs have mechanisms of action that are analogous to those of PPIs and have also been reported to be associated with risk of asthma.4,5 In addition, to account for potential residual confounding, we performed analyses based on a high-dimensional propensity score–matched18 cohort. Finally, the E-value was estimated to address the effect of potential unmeasured confounding.19,20

Results

Cohort

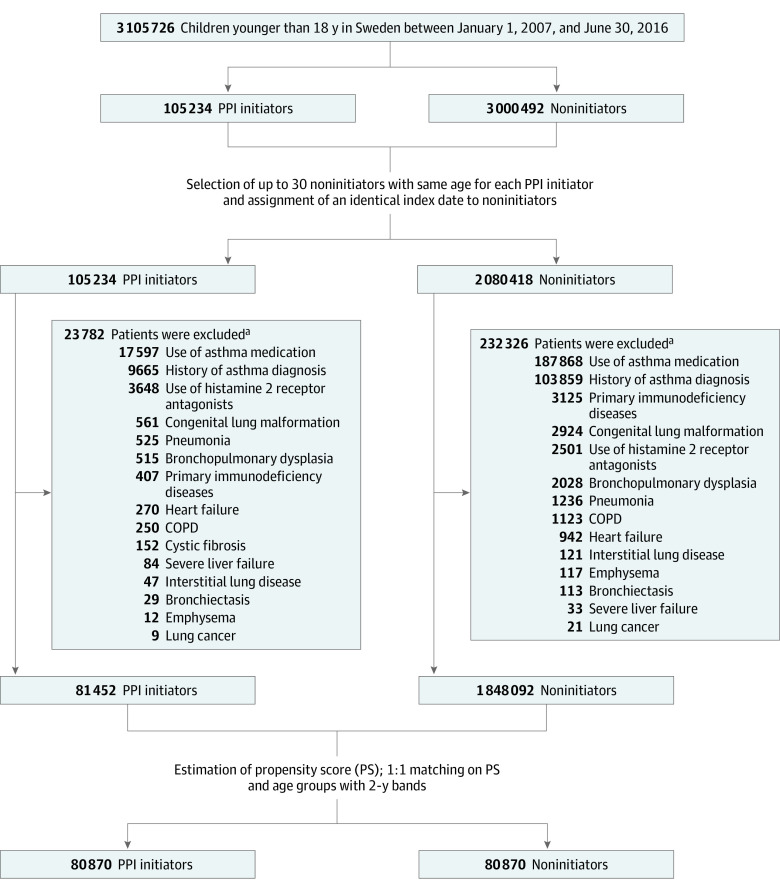

The source population included 3 105 726 children, of whom 81 452 who initiated PPI use and 1 848 092 who did not were eligible for matching (Figure 1). Before matching, children initiating PPI treatment were somewhat older (mean [SD] age, 12.9 [4.8] vs 11.5 [5.6] years), were more often female (62.7% vs 48.7%), had a higher prevalence of history of several comorbidities (eg, upper respiratory tract infection, 6.2% vs 4.0%), had more use of health care resources (eg, ≥2 emergency department visits, 11.8% vs 3.0%), and tended to receive more co-medications such as antibiotics (25.9% vs 15.8%) (Table 1). After 1:1 matching based on propensity score and age, the final study cohort included 80 870 pairs of initiators and noninitiators of PPI use. The mean (SD) age in the cohort was 12.9 (4.8) years, 63.0% were girls, and 37.0% were boys. The 2 groups were well-balanced on all baseline characteristics after matching. Median follow-up was 3.0 (interquartile range, 2.1-3.0) years in both groups. The proportional hazards assumption was not violated for the primary outcome (P = .17).

Figure 1. Flowchart for Study Cohort.

Groups were matched between children who initiated use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) (PPI initiators) and those who did not (noninitiators). COPD indicates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

aSome patients met multiple exclusion criteria.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Children Who Initiated and Did Not Initiate PPI Use Before and After Matching.

| Characteristic | Study groupa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | |||||

| PPI initiators (n = 81 452) | Noninitiators (n = 1 848 092) | Standardized difference, % | PPI initiators (n = 80 870) | Noninitiators (n = 80 870) | Standardized difference, % | |

| Female sex | 62.7 | 48.7 | 28.5 | 62.7 | 63.4 | 1.3 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 12.9 (4.8) | 11.5 (5.6) | 25.7 | 12.9 (4.8) | 12.9 (4.8) | 0.4 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 0 d to <6 mo | 3.9 | 6.3 | 10.8 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 0 |

| 6 mo to <2 y | 2.6 | 5.7 | 15.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 0 |

| 2 to <4 y | 1.4 | 2.9 | 10.8 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0 |

| 4 to <6 y | 2.4 | 4.0 | 8.9 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0 |

| 6 to <8 y | 4.5 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 0 |

| 8 to <10 y | 7.3 | 8.6 | 4.5 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 0 |

| 10 to <12 y | 10.8 | 10.4 | 1.3 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 0 |

| 12 to <14 y | 13.3 | 10.6 | 8.4 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 0 |

| 14 to <16 y | 21.6 | 16.3 | 13.5 | 21.6 | 21.6 | 0 |

| 16 to <18 y | 32.2 | 29.0 | 6.9 | 32.3 | 32.4 | 0 |

| Calendar year | ||||||

| 2007-2009 | 27.1 | 29.8 | 6.0 | 27.1 | 26.0 | 2.4 |

| 2010-2013 | 41.9 | 37.4 | 9.1 | 41.8 | 41.9 | 0.2 |

| 2014-2016 | 31.1 | 32.8 | 3.8 | 31.1 | 32.1 | 2.1 |

| Season | ||||||

| Spring (March-May) | 29.4 | 29.6 | 0.4 | 29.4 | 29.5 | 0.4 |

| Summer (June-August) | 17.2 | 17.6 | 1.2 | 17.1 | 16.8 | 1.0 |

| Autumn (September-November) | 25.7 | 24.9 | 1.8 | 25.7 | 25.8 | 0.3 |

| Winter (December-February) | 27.8 | 27.9 | 0.3 | 27.8 | 27.9 | 0.1 |

| Birth country | ||||||

| Scandinavia | 94.4 | 94.3 | 0.5 | 94.4 | 94.6 | 0.9 |

| Rest of Europe | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 0.7 |

| Outside Europe | 3.9 | 3.8 | 0.5 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 0.6 |

| Missing value | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.4 |

| Parental educational level, yb | ||||||

| ≤9 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 1.0 |

| 10-12 | 44.0 | 39.3 | 9.5 | 44.0 | 44.3 | 0.7 |

| ≥13 | 51.1 | 56.4 | 10.6 | 51.1 | 51.0 | 0.2 |

| Missing value | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1.1 |

| Parental income by quartile, SEKb | ||||||

| <233 685 | 24.6 | 24.9 | 0.7 | 24.6 | 24.1 | 1.2 |

| 233 685 to <291 722 | 26.4 | 24.9 | 3.4 | 26.4 | 26.5 | 0.3 |

| 291 722 to <372 881 | 25.5 | 25.0 | 1.2 | 25.5 | 25.6 | 0.3 |

| ≥372 881 | 23.4 | 25.0 | 3.8 | 23.4 | 23.7 | 0.7 |

| Missing value | 0.1 | 0.2 | 2.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Respiratory tract infections | ||||||

| Upper | 6.2 | 4.0 | 9.9 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 0.5 |

| Lower | 0.8 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| Serious respiratory complication | 0.6 | 0.3 | 3.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Gastrointestinal tract infections | 5.6 | 1.1 | 24.9 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 1.0 |

| Other infectious disease | 7.8 | 3.6 | 18.1 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 1.2 |

| Atopic diseases | 5.4 | 2.4 | 15.3 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 1.5 |

| Anemia | 1.3 | 0.2 | 13.5 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.9 |

| Epilepsy | 1.3 | 0.4 | 9.9 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Psychiatric disease | 5.6 | 2.4 | 16.2 | 5.6 | 5.2 | 1.7 |

| Cancer, except lung | 1.3 | 0.1 | 14.4 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.9 |

| Autoimmune disease | 5.2 | 1.2 | 22.9 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 3.5 |

| Use of health care resources | ||||||

| No. of unique drugs | ||||||

| 0 | 36.3 | 61.3 | 51.5 | 36.6 | 36.0 | 1.2 |

| 1 | 22.2 | 19.6 | 6.5 | 22.3 | 22.7 | 0.9 |

| ≥2 | 41.5 | 19.1 | 50.1 | 41.1 | 41.3 | 0.4 |

| No. of hospital admissions | ||||||

| 0 | 84.8 | 95.9 | 38.4 | 85.3 | 85.5 | 0.4 |

| 1 | 9.4 | 3.5 | 24.4 | 9.4 | 9.4 | <0.1 |

| ≥2 | 5.8 | 0.6 | 29.9 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 0.7 |

| No. of outpatient visits | ||||||

| 0 | 58.4 | 80.3 | 49.0 | 58.7 | 58.1 | 1.2 |

| 1 | 16.8 | 10.9 | 17.3 | 16.9 | 17.6 | 1.9 |

| ≥2 | 24.8 | 8.8 | 43.8 | 24.4 | 24.3 | 0.3 |

| No. of emergency department visits | ||||||

| 0 | 68.6 | 87.1 | 45.6 | 69.0 | 68.2 | 1.7 |

| 1 | 19.6 | 9.9 | 27.5 | 19.5 | 20.5 | 2.5 |

| ≥2 | 11.8 | 3.0 | 34.1 | 11.5 | 11.3 | 0.7 |

| Co-medication | ||||||

| Cardiovascular drugs | 1.5 | 0.6 | 8.8 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| Antibiotics | 25.9 | 15.8 | 25.2 | 25.7 | 26.0 | 0.6 |

| Analgesics | 4.6 | 1.4 | 19.2 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 1.9 |

| Antiviral drugs | 0.7 | 0.2 | 6.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.4 |

| Antipsychotics | 0.6 | 0.2 | 6.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| Antidepressants | 2.7 | 0.8 | 14.7 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 1.2 |

| BZRAs | 1.3 | 0.3 | 11.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| Systemic antihistamines | 7.4 | 4.1 | 14.2 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 1.2 |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 3.5 | 0.9 | 17.5 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 3.4 |

| NSAIDs | 8.5 | 2.2 | 28.3 | 8.3 | 7.8 | 1.9 |

Abbreviations: BZRAs, benzodiazepine receptor agonists; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; SEK, Swedish krona.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as percentage of children.

Covariate based on the parent with the highest achieved educational level or income.

Main Findings

Table 2 shows the results of the primary and secondary analyses, whereas eFigure 2 in the Supplement shows the cumulative incidence curve for the primary analysis. In the primary analysis, the incidence rate of asthma was 21.8 per 1000 person-years among those who initiated PPI use and 14.0 per 1000 person-years among those who did not; PPI use was associated with an increased risk of asthma (HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.49-1.64). In secondary analyses, the HR for asthma defined based on diagnosis was 1.53 (95% CI, 1.38-1.70), whereas for asthma defined based on drug prescription the HR was 1.57 (95% CI, 1.49-1.66). In analyses of the timing of asthma onset after initiation of PPI use, the HRs were 1.62 (95% CI, 1.42-1.85) for 90 days or less, 1.73 (95% CI, 1.52-1.98) for 91 to 180 days, and 1.53 (95% CI, 1.45-1.62) for 181 days or longer. In the analysis of individual drugs and risk for asthma, HRs were 1.64 (95% CI, 1.50-1.79) for esomeprazole, 1.49 (95% CI, 1.25-1.78) for lansoprazole, 1.43 (95% CI, 1.35-1.51) for omeprazole, and 2.33 (95% CI, 1.30-4.18) for pantoprazole. In the assessment of cumulative duration of PPI use and risk of asthma, significant associations were found regardless of the cumulative duration (HR for PPI treatment duration of ≤30 days, 1.52 [95% CI, 1.44-1.61]; HR for 31-364 days, 1.51 [95% CI, 1.42-1.60]; and HR for ≥365 days, 1.59 [95% CI, 1.25-2.02]) (Table 3).

Table 2. Main Results of Associations Between PPI Use and Risk for Asthma.

| Analysis | PPI initiators (n = 80 870) | Noninitiators (n = 80 870) | Absolute risk difference in incidence (95% CI)a | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events | Incidence ratea | No. of events | Incidence ratea | |||

| Primary analysis | 4428 | 21.8 | 2818 | 14.0 | 7.9 (7.1-8.7) | 1.57 (1.49-1.64) |

| Secondary analyses | ||||||

| Asthma definition | ||||||

| Diagnosis of asthma | 863 | 4.3 | 561 | 2.8 | 1.5 (1.1-1.8) | 1.53 (1.38-1.70) |

| 2 Asthma drug prescription fills within 90 d | 3565 | 17.6 | 2257 | 11.2 | 6.4 (5.7-7.1) | 1.57 (1.49-1.66) |

| Timing of asthma onset (days after treatment initiation) | ||||||

| ≤90 | 592 | 29.5 | 365 | 18.2 | 11.3 (8.3-14.3) | 1.62 (1.42-1.85) |

| 91-180 | 576 | 29.3 | 333 | 16.9 | 12.4 (9.4-15.4) | 1.73 (1.52-1.98) |

| ≥181 | 3260 | 20.0 | 2120 | 13.1 | 6.9 (6.0-7.8) | 1.53 (1.45-1.62) |

| Individual drugsb | ||||||

| Esomeprazole | 1250 | 52.2 | 777 | 31.8 | 20.4 (16.8-24.1) | 1.64 (1.50-1.79) |

| Lansoprazole | 305 | 37.4 | 204 | 25.1 | 12.2 (6.8-17.6) | 1.49 (1.25-1.78) |

| Omeprazole | 2854 | 16.8 | 1985 | 11.8 | 5.0 (4.2-5.8) | 1.43 (1.35-1.51) |

| Pantoprazole | 37 | 17.4 | 16 | 7.5 | 10.0 (3.3-16.6) | 2.33 (1.30-4.18) |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Calculated as events per 1000 person-years.

Rabeprazole was not analyzed due to small sample size (n = 6). The numbers of matched pairs of each subcohort were 11 305 for esomeprazole, 3219 for lansoprazole, 65 860 for omeprazole, and 821 for pantoprazole.

Table 3. Associations Between PPI Use and Risk for Asthma, Stratified by Cumulative Duration of PPI Use.

| Initiation status | Person-years (% of total person-years) | No. of events | Incidence ratea | Absolute risk difference in incidence (95% CI)a | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 201 971.1 (100) | 2818 | 14.0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Time since initiation, d | |||||

| ≤30 | 111 331.6 (55) | 2419 | 21.7 | 7.8 (6.8-8.8) | 1.52 (1.44-1.61) |

| 31-364 | 88 829.9 (44) | 1939 | 21.8 | 7.9 (6.8-9.0) | 1.51 (1.42-1.60) |

| ≥365 | 2707.9 (1) | 70 | 25.9 | 11.9 (5.8-18.0) | 1.59 (1.25-2.02) |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Calculated as events per 1000 person-years.

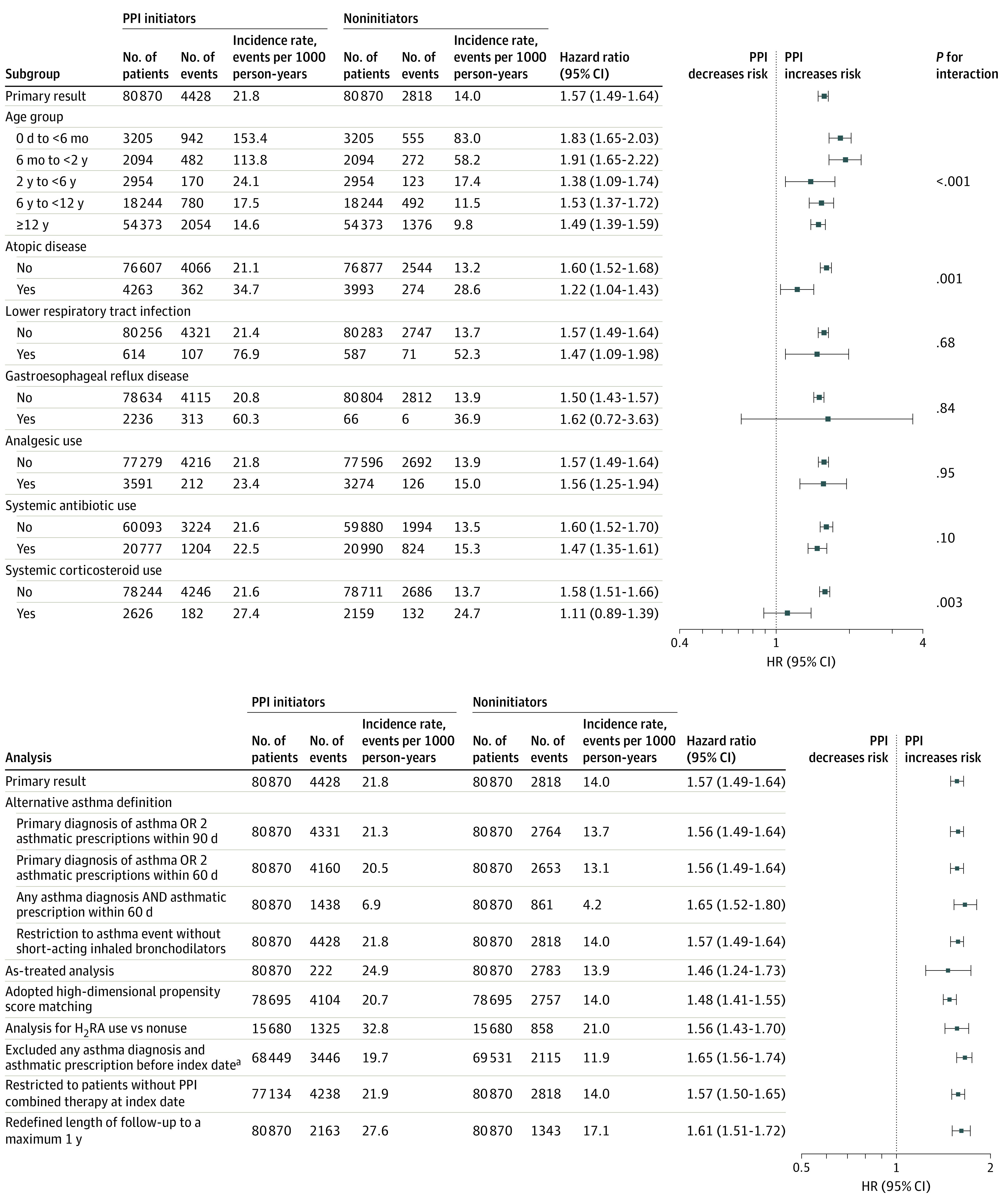

Subgroup Analyses

The results of subgroup analyses are shown in Figure 2. The association between PPI use and risk of asthma differed significantly by age group at initiation of PPI use (P < .001 for interaction). The risk of asthma was highest in the groups younger than 6 months (HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.65-2.03) and 6 months to younger than 2 years (HR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.65-2.22). In addition, the association between initiation of PPI use and risk of asthma was significantly different in subgroup analyses according to history of atopic disease (HR for history, 1.22 [95% CI, 1.04-1.43]; HR for no history, 1.60 [95% CI, 1.52-1.68]; P = .001 for interaction) and recent use of systemic corticosteroids (HR for use, 1.11 [95% CI, 0.89-1.39]; HR for no use, 1.58 [95% CI, 1.51-1.66]; P = .003 for interaction). In each of these analyses, the HR was higher among patients without history of the disease or drug of interest than among patients with the history. Conversely, we observed no difference in association between PPI use and risk of asthma between subgroups analyzed according to history of lower respiratory tract infection, gastroesophageal reflux disease, systemic antibiotic use, and analgesic use.

Figure 2. Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses of Associations Between Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) Use and Risk for Asthma.

H2RA indicates histamine 2 receptor antagonist; HR, hazard ratio.

aExcluded any asthma diagnosis or prescription in all available look-back before index date.

Sensitivity Analyses

In all sensitivity analyses (Figure 2 and eTables 2 and 3 and eFigures 3 and 4 in the Supplement), PPI use was consistently associated with an increased risk of asthma, including high-dimensional propensity score matching (HR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.41-1.55). In addition, the estimated E-value was 2.52 for the point estimate of the primary analysis and 2.34 for the lower CI limit; hence, an unmeasured confounder would have had to have an association with both PPI use and risk of asthma on the risk ratio scale of more than 2.34 to fully explain away the PPI-asthma association observed in the primary analysis.

Discussion

In this nationwide cohort study, we observed a significant 57% increased risk of asthma among children who initiated PPI use compared with those who did not initiate PPI use. An increased risk was observed across all age groups and was greatest in infants and toddlers younger than 2 years. The finding was consistent across individual PPIs, and the risk increase was similar regardless of the cumulative duration of PPI treatment. An increased risk was observed for asthma occurring early after treatment initiation, as well as later. The findings were robust in sensitivity analyses, including an as-treated analysis and high-dimensional propensity score matching.

Two recent meta-analyses,4,5 both including 8 observational studies, showed that pregnant women who used PPIs had an increased risk of delivering offspring who subsequently developed asthma (study 1 pooled HR, 1.30 [95% CI, 1.07-1.56; I2 = 45.2%]4; study 2 pooled relative risk, 1.34 [95% CI, 1.18-1.52; I2 = 46%]5). Similarly, another cohort study in adults6 reported an increased risk of asthma associated with PPI use (adjusted HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.64-1.88). Until the present study, only 1 cohort study,11 to our knowledge, has assessed the association of PPI use during infancy with risks of various types of allergic diseases in childhood. In that study, the reported adjusted HR for risk of asthma in infants who received PPIs in the first 6 months of life was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.31-1.52). These data are in accordance with these aforementioned studies4,5,6,11 and provide, to our knowledge, the first comprehensive investigation of the association between PPI use and risk of asthma in a large and unselected nationwide population of children and adolescents across the entire age range of pediatric care using advanced analytical methods.

One hypothesized underlying mechanism linking PPIs to asthma is believed to include PPI-mediated interference of the balance between the symbiotic and pathological microbial species in the gut and lung,10 subsequently leading to asthma through hyperactivation of helper T2 cell–dominated immune responses and overproduction of inflammatory cytokines resulting in airway inflammation.9 Given that the association between PPI use and risk of asthma was observed already within 90 days after PPI initiation, dysregulation of immunity would have to occur through a rapid change of the microbiome. This possibility is supported by previous in vivo studies21 reporting that substantial disruption of microbial composition and diversity in the gut can occur within 4 weeks after PPI treatment. Alternative mechanisms could also be possible; for instance, PPIs might damage lung tissue directly, given that PPIs have been linked to impaired endothelial function and accelerated endothelial senescence in a previous study.22

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. We included a large population of children treated with PPIs, enabling not only ample statistical power in the primary analysis but also exploration of heterogeneity of the association by age and analyses of individual PPIs and by duration. Given the unselected nationwide population, results are likely generalizable to other similar populations. Implementation of a new-user design served to minimize selection bias. In addition, the inclusion of a wide range of covariates in the propensity score served to minimize confounding by baseline characteristics.

This study also has limitations. First, we cannot rule out the possibility of misclassification of outcome because we could not capture a diagnosis of asthma from the primary care setting, which likely represents patients with mild asthma. Nonetheless, to minimize outcome misclassification, we identified asthma requiring validated diagnosis codes or at least 2 asthma prescriptions within 90 days in which all asthma prescriptions, regardless of care level, were covered. Moreover, in sensitivity analyses, we tested potentially more specific outcome definitions. Exposure misclassification may exist because first, we cannot be certain whether patients actually used PPIs after having filled their prescriptions, and second, we did not have data on PPI use during hospitalization or as over-the-counter medication. In the event some patients presented with symptoms of both gastroesophageal reflux and asthma, one possibility is that the asthma symptoms were interpreted as having been elicited by the reflux; in that scenario, PPIs could possibly have been prescribed for the first symptoms of undiagnosed asthma, which would have led to protopathic bias. However, this scenario is unlikely to explain our observed associations with PPI use because we observed a persistent significant association after 180 days since PPI initiation. In addition, confounding by indication may have been introduced because the indications for PPIs were not assessable. Finally, despite application of several advanced epidemiological methods, some unmeasured confounders may have affected our findings, such as microbiota data and prenatal, genetic, and environmental factors known to modulate the risk of asthma.

Conclusions

In this cohort study, use of PPIs compared with nonuse was associated with an increased risk of asthma. Proton pump inhibitors should be prescribed to children only when clearly indicated, weighing the potential benefit against potential harm.

eFigure 1. Schematic Depiction of Study Design for Primary Analysis

eFigure 2. Cumulative Risk for Asthma for PPI Initiators and Noninitiators

eFigure 3. Flowchart for H2RA Analysis

eFigure 4. Value of the Joint Minimal Strength of Association That an Unmeasured Confounder Must Associate With Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Asthma to Fully Explain the Observed HR in the Primary Analysis

eTable 1. Codes Used to Define the Exclusion Criteria, Outcomes, Comorbidities, and Co-medications

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of H2RA Initiators and Noninitiators Before and After Matching

eTable 3. List of Top-Ranked 200 Covariates Included in High-Dimensional Propensity Score Model

References

- 1.Hales CM, Kit BK, Gu Q, Ogden CL. Trends in prescription medication use among children and adolescents—United States, 1999-2014. JAMA. 2018;319(19):2009-2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.5690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blank ML, Parkin L. National study of off-label proton pump inhibitor use among New Zealand infants in the first year of life (2005-2012). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65(2):179-184. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruigómez A, Kool-Houweling LMA, García Rodríguez LA, Penning-van Beest FJA, Herings RMC. Characteristics of children and adolescents first prescribed proton pump inhibitors or histamine-2-receptor antagonists: an observational cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(12):2251-2259. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1336083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devine RE, McCleary N, Sheikh A, Nwaru BI. Acid-suppressive medications during pregnancy and risk of asthma and allergy in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(6):1985-1988.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai T, Wu M, Liu J, et al. Acid-suppressive drug use during pregnancy and the risk of childhood asthma: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2):e20170889. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang YT, Tsai MC, Wang YH, Wei JC. Association between proton pump inhibitors and asthma: a population-based cohort study. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:607. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearce N, Aït-Khaled N, Beasley R, et al. ; ISAAC Phase Three Study Group . Worldwide trends in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Thorax. 2007;62(9):758-766. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.070169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perry R, Braileanu G, Palmer T, Stevens P. The economic burden of pediatric asthma in the United States: literature review of current evidence. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(2):155-167. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0726-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hufnagl K, Pali-Schöll I, Roth-Walter F, Jensen-Jarolim E. Dysbiosis of the gut and lung microbiome has a role in asthma. Semin Immunopathol. 2020;42(1):75-93. doi: 10.1007/s00281-019-00775-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy EI, Hoang DM, Vandenplas Y. The effects of proton pump inhibitors on the microbiome in young children. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(8):1531-1538. doi: 10.1111/apa.15213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitre E, Susi A, Kropp LE, Schwartz DJ, Gorman GH, Nylund CM. Association between use of acid-suppressive medications and antibiotics during infancy and allergic diseases in early childhood. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(6):e180315. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Global Initiative for Asthma . 2020 GINA report: global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Updated 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020. https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/

- 13.Örtqvist AK, Lundholm C, Wettermark B, Ludvigsson JF, Ye W, Almqvist C. Validation of asthma and eczema in population-based Swedish drug and patient registers. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(8):850-860. doi: 10.1002/pds.3465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austin PC. Some methods of propensity-score matching had superior performance to others: results of an empirical investigation and Monte Carlo simulations. Biom J. 2009;51(1):171-184. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66(3):516-554. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(1):3-20.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones NL, Koletzko S, Goodman K, et al. ; ESPGHAN, NASPGHAN . Joint ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori in children and adolescents (update 2016). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64(6):991-1003. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang YH, Wintzell V, Ludvigsson JF, Svanström H, Pasternak B. Association between proton pump inhibitor use and risk of fracture in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(6):543-551. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268-274. doi: 10.7326/M16-2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathur MB, Ding P, Riddell CA, VanderWeele TJ. Website and R package for computing E-values. Epidemiology. 2018;29(5):e45-e47. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hojo M, Asahara T, Nagahara A, et al. Gut microbiota composition before and after use of proton pump inhibitors. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(11):2940-2949. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5122-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yepuri G, Sukhovershin R, Nazari-Shafti TZ, Petrascheck M, Ghebre YT, Cooke JP. Proton pump inhibitors accelerate endothelial senescence. Circ Res. 2016;118(12):e36-e42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Schematic Depiction of Study Design for Primary Analysis

eFigure 2. Cumulative Risk for Asthma for PPI Initiators and Noninitiators

eFigure 3. Flowchart for H2RA Analysis

eFigure 4. Value of the Joint Minimal Strength of Association That an Unmeasured Confounder Must Associate With Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Asthma to Fully Explain the Observed HR in the Primary Analysis

eTable 1. Codes Used to Define the Exclusion Criteria, Outcomes, Comorbidities, and Co-medications

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of H2RA Initiators and Noninitiators Before and After Matching

eTable 3. List of Top-Ranked 200 Covariates Included in High-Dimensional Propensity Score Model