Abstract

A 32-year-old doctor, who has a medical history of primary Raynaud’s disease and previous scotomas, presented to eye clinic with sudden onset blurring of vision (infero-nasally) with no other associated symptoms. The patient had good visual acuity bilaterally (6/6) and no anterior chamber activity or conjunctival hyperaemia. Findings consistent with a nerve fibre layer infarct were noted in the right eye, with unremarkable examination of the left eye. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) and optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) images were obtained, which showed an area of capillary shut down in keeping with a nerve fibre layer lesion. Previous literature pertaining to similar symptoms is sparse with symptoms such as migraines, epilepsy and visual loss being stated. This case provides further evidence of Raynaud’s associated retinal artery spasm, with complete resolution at 4 weeks. We also demonstrate the accessibility of OCT and more importantly OCTA for investigation of sudden onset visual deficit.

Keywords: ophthalmology, retina, rheumatology

Background

Raynaud’s disease, first described by Maurice Raynaud in 1862, is a phenomenon classically described as a triphasic colour change of the extremities due to vasospasm, often triggered by cold temperatures or emotive causes.1 2 Primary Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) by diagnosis of exclusion is a generally benign condition and has a prevalence of up to 20% in women and 14% in men with an average age of between 15 and 30 years at diagnosis.3 4

Most commonly, this characteristic intermittent vasospasm affects the digits of the hand, however, symptoms including migraines, epilepsy secondary to cerebral artery spasm and ocular manifestations have been noted.5 We report a case of ocular manifestations of primary RP caused by a suspected reversible retinal vessel spasm. Literature is sparse concerning ocular symptoms associated with RP, however, cases have been reported complaining of blurred vision and in some instances sudden onset loss of vision which must be differentiated from central retinal artery occlusion.5 6

Primary RP is most often treated with calcium channel blockers, for example, nifedipine, however, causes of secondary RP and central retinal artery occlusions must be ruled out with further investigations.4 7 Appropriate follow-up should also be scheduled to monitor visual deficit and assess resolution of symptoms.

Case presentation

A 32-year-old female doctor presented at the start of the winter season to the eye clinic of a tertiary care hospital with sudden onset blurred vision in the infero-nasal aspect of her right eye. She noticed this in the morning while getting ready for work and described her visual symptom as ‘smeared vision’. There was no history of recent trauma, headaches, ocular pain, flashing lights, floaters or loss of vision. Her medical history was significant for primary RP. She was a non-smoker and there was no previous history of any thromboembolic episodes reported, however, a history of scotomas was reported at the age of 19 years secondary to oral contraceptive pills, which was subsequently discontinued. Her family history was negative for venous thromboembolic disease and her medication history included nifedipine 10 mg once a day during the winter season only.

When seen in the eye clinic, the patient had good visual acuity bilaterally (6/6 left eye and 6/6 right eye). Both of her eyes were quiet with no conjunctival hyperaemia, no anterior chamber activity and normal intraocular pressures of 12 mm Hg bilaterally. Clinical markers of optic nerve assessment were normal including no relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD), full colour vision in both eyes and a full visual field to confrontation. Dilated fundal examination on slit lamp in the right eye showed a small area of cotton wool spots just inferior to the superior arcade consistent with a nerve fibre layer infarct. There was no evidence of disc swelling or haemorrhages and examination of her left eye was unremarkable. Lastly, the patient did not complain of any peripheral symptoms and on examination of her hands there was good peripheral perfusion with a normal capillary refill time.

Investigations

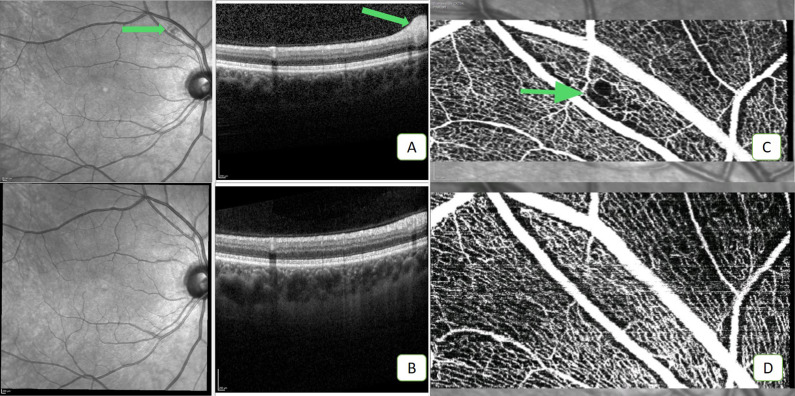

Although the clinical findings were apparent on slit-lamp examination of the fundus, optical coherence tomography (OCT) and optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) images were obtained to support the examination findings as well as to rule out any other retinal lesions including macular involvement. The first OCT scan (figure 1A) shows the posterior segment of the right eye, taken on presentation and demonstrates a small area of nerve fibre layer infarct under the superior arcade (arrow head). A follow-up OCT scan taken after 4 weeks from initial presentation (figure 1B) shows complete resolution of the lesion. OCTA (figure 1C) demonstrates a focal area of capillary shut down (green arrow), consistent with the above finding. Another OCT finding of note is the focal oedema caused by vasospasm (figure 2). The OCTA scan (figure 1D), taken multiple weeks after presentation, shows restoration of blood flow indicating resolution of the vasospasm. A battery of tests were performed on initial presentation including full blood count, inflammatory markers (C reactive protein (CRP), Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)), liver and renal profile as well as autoimmune, thrombophilia screening and carotid doppler ultrasound, which were all negative.

Figure 1.

OCT panel showing images taken at presentation (A) and at 4 weeks (B). Complete resolution of the lesion in scan A (indicated by the arrowhead) is seen at 4 weeks in scan B. The right hand panel of scan A also demonstrates RNFL thickening correlating with the en face view. OCTA scan at presentation (C) showing an area of focal capillary shut down consistent with retinal vasospasm (indicated by green arrowhead). OCTA scan at follow-up (D) shows recovery of this focal vessel shut down indicating restoration of blood flow. OCT, optical coherence tomography; OCTA, optical coherence tomography angiography; RNFL, Retinal nerve fibre layer.

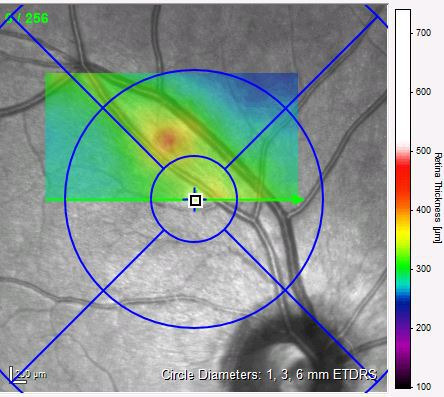

Figure 2.

OCT scan from the patient’s first presentation showing localised retinal oedema due to capillary shut down. The red area indicates increased retinal thickness signifying oedema. OCT, optical coherence tomography.

Differential diagnosis

Primary RP, also known as idiopathic Raynaud’s disease, is important to differentiate from secondary RP which can be caused by autoimmune conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The main differentiating factor between primary and secondary RP is evidence of peripheral vascular disease. Patients with primary RP should have no signs of tissue gangrene or digital pitting. History and examination can shed light on existing and previous systemic symptoms, however, a full panel of tests should be conducted to exclude underlying systemic pathology. These tests include full blood count, metabolic panel, muscle enzymes, rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinated peptide, thyroid studies, hepatitis screening, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies.4

Slit-lamp examination allows us to begin to differentiate between benign RP and vascular causes such as central retinal artery occlusions. Follow-up is important in order to assess resolution and monitor further deterioration. Salmenson et al describe prolonged reduction by 30% in retinal capillary flow in response to cold stimuli, with resolution of flow subsequently.8 OCTA, a relatively novel investigation, now allows us to promptly assess the retinal vasculature, and enables us to monitor vascular lesions over a period of time.

Given this patient’s medical history, in conjunction with a transient retinal vascular lesion which has shown full spontaneous reversibility, a diagnosis of primary RP causing intermittent spams of retinal blood vessels was made.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was seen in clinic again at 4 weeks, at which point her symptoms had resolved and repeat scans were obtained. She complained of no new visual symptoms which corroborated by resolution of the lesion found on the initial OCT and OCTA scans.

This patient was given advice to return promptly to eye casualty should the symptoms recur, however, no further visits to eye casualty have been noted thus far.

Discussion

This patient who presented with sudden onset blurred vision in her right her, with consistent focal OCTA changes, was diagnosed with intermittent retinal vasospasm secondary to primary RP. Very few cases have been reported in the literature to date, with limited details regarding the patient history and follow-up outcomes.5 6 9–11 Ocular manifestations were first described as far back as 1871, when Hutchinson reported iridoplegia, where the pupil was fixed and dilated during attacks and could last for a number of days.5 Ocular symptoms caused by retinal vasospasm more commonly include blurring of peripheral vision and more rarely central loss of vision. A range of additional symptoms associated with RP have been described including migraines, epilepsy, transient hemiplegia, haemoglobinuria and acute joint inflammations.5 10 Patients presenting with sudden onset visual deficit should be assessed at the earliest opportunity in eye clinic. As primary RP is a diagnosis of exclusion, connective tissue diseases such as SLE and scleroderma should be ruled out. RP has been reported to occur in 8%–10% of SLE cases, and 70%–80% of scleroderma cases.12 Investigations should include a full blood panel with autoimmune antibody testing, OCT and OCTA, and ultrasound doppler of carotid arteries to exclude thromboembolic causes. Treatment is most commonly with calcium channel blockers, for example, nifedipine 30–60 mg, however, there is conflicting evidence surrounding its efficacy in reducing attack frequency and severity in primary RP.1 7 13

Visual-associated or Central nervous system (CNS)-associated symptoms should be expected to resolve in primary RP, however, in some cases, an extended period of ischaemia can lead to longstanding damage for example, irreversible visual loss due to ganglion cell death. The pathophysiology of primary RP vasospasm is still not understood in depth, however, theories suggest that this phenomenon could be due to sympathetic nervous system overactivity triggered by factors such as emotional stress or cold stimuli.2 Studies report the appearance of CNS vasospastic features in both primary and secondary RP, with a prolonged decrease of up to 30% in retinal capillary flow in response to peripheral cold stimulus.8 This is supported by further evidence showing that field damage can be aggravated by cold stimulus which may improve after administration of calcium channel blockers.14 Reversibility is also seen in a case described by Carpenter, where the patient’s retina was found to be pale with arteries appearing as white streaks.6 At 2 weeks the retinal vessels had recovered. Similar cases are reported with varying degrees of resolution of visual deficit.9–11

We report the first case of ocular manifestations of primary RP assessed using OCT and OCTA imaging techniques. This case demonstrates transient blurring of peripheral vision and associated image findings, with complete resolution suggesting an intermittent nature. Existing literature reports a limited number of RP-associated ocular manifestations, however, the differentiation between primary and secondary RP is often unclear. Spencer-Green reports that 12.6% of patients with primary RP developed a connective tissue disorder, with transition over an average age of 10.4 years from onset of RP.15 Ocular manifestations of RP should be investigated thoroughly to rule out underlying disease. Patients should be followed up appropriately and monitored for further ocular and systemic symptoms in order to detect visual deterioration early and prevent potentially sight-threatening prolonged vasospasm.

Patient’s perspective.

This was a very strange experience for me. I woke up early one September morning last year to go for a run before work and remember it being a chilly morning but not too cold. By the time I got out of the shower I was aware that the vision in the infero-medial corner of my right eye was a little blurry but thought this would probably resolve in due course. An hour later arriving at work I was still aware of this small patch, which to me seemed as if there were a smudge on my glasses, despite the fact that I had put a pair of contact lenses in after my shower. Since I was working in the hospital I thought I would see if someone was able to check it out for me as I was not needed for clinical work that morning. I felt a little hypochondriacal seeing the ophthalmology SpR on call, however was shocked that the OCT showed a cotton wool spot on my retina which correlated with the zone of my visual loss. I felt well and had no other symptoms throughout the episode and I am a fit and well individual with no other medical conditions other than my primary Raynaud’s disease (for which I take PRN calcium channel blockers during winter months). After a couple of days I began to not notice the patch of visual loss, whether this was due to cortical re-adjustment or revascularisation of my retina I could not establish. I was very impressed and happy with the involvement of my ophthalmologist and his team over the coming month or so with multiple appointments, emails and investigations. After discussion with my consultant and a brief literature search myself I understood that this phenomenon was rare and incredibly unlikely to occur again. By my final appointment approximately 6 weeks after the initial episode I was reassured that my retina had revascularised, there was no evidence of an underlying disorder and I was discharged from the clinic. My ophthalmologist referred me to a rheumatologist to rule out other secondary causes of Raynaud’s, from which all investigations thankfully were negative. I have had no further eye symptoms and minimal problems with my Raynaud’s over last winter provided I took a dose of amlodipine.

Learning points.

Retinal vessel spasms are a rare cause of visual disturbance and can be associated with both primary and secondary Raynaud’s disease.

Secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP), causing intermittent vasospasm, can cause ocular tissue asphyxia with irreversible damage in some cases even with resolution of blood flow. Therefore, appropriate follow-up should be arranged to include examination in conjunction with optical coherence tomography and novel optical coherence tomography angiography scans to confirm resolution of any detected lesions.

Primary RP is a diagnosis of exclusion and patients should be thoroughly investigated to rule out potentially sight-threatening or systemic causes.

More than 1 in 10 patients with primary RP may develop a connective tissue disease, hence thorough investigation and follow-up is important.

Footnotes

Contributors: YA identified the patient for this case report, obtained the images and consented the patient. YA and AUK contributed equally to drafting and reviewing the manuscript. YA, AUK and MT all made valuable contributions to reviewing and redrafting the manuscript. YA and AUK are joint first authors of this case report.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Wigley FM, Flavahan NA. Raynaud's phenomenon. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1996;22:765–81. 10.1016/S0889-857X(05)70300-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halperin JL, Coffman JD. Pathophysiology of Raynaud's disease. Arch Intern Med 1979;139:89–92. 10.1001/archinte.1979.03630380067022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suter LG, Murabito JM, Felson DT, et al. The incidence and natural history of Raynaud's phenomenon in the community. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1259–63. 10.1002/art.20988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temprano KK A review of Raynaud's disease. Mo Med 2016;113:123–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunphy EB Ocular manifestations of Raynaud's disease. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1932;30:420–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpenter WM Raynaud’s disease with intermittent spasm of the retinal artery and veins. Arch Ophthal 1938;19:111 10.1001/archopht.1938.00850130123014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ennis H, Hughes M, Anderson ME. Calcium channel blockers for primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salmenson BD, Reisman J, Sinclair SH, et al. Macular capillary hemodynamic changes associated with Raynaud's phenomenon. Ophthalmology 1992;99:914–9. 10.1016/S0161-6420(92)31874-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson RG Spasm of the central retinal artery in raynaud’s disease. Arch Ophthal 1937;17:662 10.1001/archopht.1937.00850040096004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Appelbaum SJ, Lerner ML. Raynaud’s Disease by Ocular Complications. Am J Ophthalmol 1926;9:569–73. 10.1016/S0002-9394(26)90437-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts H, Tomlinson S. Cerebral vasospasm and primary Raynaud's phenomenon. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:743–4. 10.1093/bja/aen285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardelli MB, Kleinsmith DM. Raynaud's phenomenon and disease. Med Clin North Am 1989;73:1127–41. 10.1016/S0025-7125(16)30623-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson AE, Pope JE. Calcium channel blockers for primary Raynaud's phenomenon: a meta-analysis. Rheumatology 2005;44:145–50. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gasser P, Flammer J, Guthauser U, et al. Do vasospasms provoke ocular diseases? Angiology 1990;41:213–20. 10.1177/000331979004100306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spencer-Green G Outcomes in primary Raynaud phenomenon: a meta-analysis of the frequency, rates, and predictors of transition to secondary diseases. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:595–600. 10.1001/archinte.158.6.595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]