Abstract

It is widely recognized that solvation is one of the major factors determining structure and functionality of proteins and long peptides, however it is a formidable challenge to address it both experimentally and computationally. For this reason, simple peptides are used to study fundamental aspects of solvation. It is well established that alcohols can change the peptide conformation and tuning of the alcohol content in solution can dramatically affect folding and, as a consequence, the function of the peptide. In this work, we focus on the leucine and lysine based LKα14 peptide designed to adopt an α-helical conformation at an apolar–polar interface. We investigate LKα14 peptide’s bulk and interfacial behavior in water/ethanol mixtures combining a suite of experimental techniques (namely, circular dichroism and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy for the bulk solution, surface pressure measurements and vibrational sum frequency generation spectroscopy for the air–solution interface) with molecular dynamics simulations. We observe that ethanol highly affects both the peptide location and conformation. At low ethanol content LKα14 lacks a clear secondary structure in bulk and shows a clear preference to reside at the air–solution interface. When the ethanol content in solution increases, the peptide’s interfacial affinity is markedly reduced and the peptide approaches a stable α-helical conformation in bulk facilitated by the amphiphilic nature of the ethanol molecules.

Introduction

The importance of protein–solvent interactions can hardly be overestimated since solvation governs biological systems. The solvent is not a passive medium, but plays a role in determining both the protein conformation and function, and to study protein solvation, both experimental and simulation techniques have been used.1 However, understanding the protein–solvent interactions is problematic due to the complexity of these systems. Thus, peptides are frequently studied instead of big proteins because of their own importance but also because they can be used as model systems to understand bigger and more complex proteins.2−4

For obvious biological reasons, a particular emphasis has been given to the role of water in peptide conformational behavior at the microscopic level with a special focus on the examination of the hydrophobic effect at the solvation interface. In a study, the 21-residue polyalanine-based Fs peptide has been shown to exhibit complex conformational preferences depending on the character of the local solvation interface.2 The addition of alcohol into the aqueous solution is a powerful tool to modify the peptide/protein solvation. For instance, the combination of hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity intrinsic to the amphiphilic nature of the ethanol molecule, can facilitate its interactions with peptides/proteins resulting in an excess solvation by ethanol over water. In fact, it has been reported that aqueous ethanol solutions can change the conformational behavior and stability of biomolecules5−13 which, in turn, may influence both biomolecular activity and functions.7,11 For instance, Met-enkephalin and the C-peptide fragment of ribonuclease A have been studied in water, methanol, and ethanol, and it has been observed that the alcohols promote folding into structures with intramolecular hydrogen bonds (such as an α-helix), that in alcohol the solvation free energy is not very sensitive to changes in peptide conformation, and that the degree of the induced secondary structure increases as the bulkiness of hydrocarbon group of alcohol increases.5 Gerig has reported an excess solvation of [val5]angiotensin in 35% aqueous ethanol with ethanol over water which is particularly apparent for side chains of valine, tyrosine, and phenylalanine as a result of their hydrophobicity.6 Moreover, the author has also observed a preferential orientation of ethanol molecules at the peptide surface, both at the backbone and hydrophobic side chain positions. Chattoraj and co-workers found that differences in ethanol content generate oscillations in the structure and dynamics of lysozyme, providing a potential way to control the structure and, as a sequence, the biological activity of the protein by regulating ethanol content.7

Understanding the fundamentals of peptide/solvent interactions provides principles for rational peptide design. DeGrado and Lear synthesized LK peptides consisting of only two types of amino acid residues, hydrophobic leucine (L) and hydrophilic lysine (K).14 By design, the peptides can fold at the apolar–polar interface into α- or β-motifs with hydrophobic residues accumulating on one side of the structure. The secondary structure has been found to depend on the hydrophobic periodicity and the chain length. These authors also found that the secondary structure in bulk and at the apolar–water interface, as well as the bulk association, are determined mainly by hydrophobic interactions.14 Such highly ordered structures carry great potential for use in molecular-scale surface design. DeGrado and co-workers further developed the concept of creating model structures following minimal complexity approach and using simple amino acid sequences. By understanding the factors stabilizing the α-helical conformation and contributing to helixes packing, these authors were even able to design α-helical coiled coils resembling an ion channel.15

In this work we focus on the LKα14 peptide, LKKLLKLLKKLLKL, designed by DeGrado and Lear to fold into an α-helical conformation at the apolar/polar interface14 with hydrophobic L residues generally oriented toward the apolar and K residues in contact with polar phase.16,17 The system has been well characterized in aqueous solutions and at the air–water interface. Specifically for the air–water interface, it has been shown that the vibrational sum frequency generation (SFG) spectrum for LKα1418 is similar to that obtained for L residues19 which is consistent with the interfacial ordering of the L residues excluded from the aqueous phase. The secondary structure of LKα14 at the air–water interface was probed by means of SFG using chiral polarization combinations20,21 and was also addressed in MD simulations.22−24 It has been further shown that the peptide’s α-helical axis is almost parallel to the air–water interface and that the N-terminus points toward the water subphase.25 Interestingly, a similar orientation was reported for LKα14 at a buried hydrophobic-solid–water interface.17 The peptide behavior, including conformation and aggregation analysis, has also been extensively studied in bulk. In contrast to the interface with air, LKα14 lacks well-defined secondary structure in bulk water14,26 as it samples several conformations in the dilute regime.22−24 LKα14 peptide’s conformational preferences and interfacial adsorption affinity has also been investigated in less conventional solvent environments, but the results further confirm the importance of the solvent environment for peptide location and folding. For instance, it has been reported that LKα14 α-helical secondary structure can be stabilized in bulk by adding fluorinated alcohols into the aqueous solution26 or by using ionic liquids.27

In this study, surface-sensitive and bulk experimental techniques have been combined with MD simulations in order to investigate the LKα14 peptide bulk-interface affinity and conformation in water/ethanol mixtures. We show that the aqueous ethanol solvent environment has a substantial influence on the LKα14 peptide’s location and folding. Ethanol is amphiphilic and thus facilitates the stabilization of the LKα14 α-helical conformation by hydrophobic and/or hydrogen bonding interactions in bulk, similarly to what happens at the air–water interface. However, in pure water solutions the α-helical structure is observed exclusively at the air–water interface. We believe that our results highlight the role of solvent in determining the solvated peptide’s behavior and will contribute to a deeper understanding of peptide solvation. It is also worth mentioning that the widely exploited ability of alcohols to denature proteins28,29 appears to be strongly dependent on the protein structure, in fact what we observe is that ethanol promotes structure formation for the LKα14 peptide in bulk solution.

Experimental Section

Sample Preparation

LKα14 peptide (with the acetylated N-terminus) was purchased from GenScript Biotech (peptide purity 96.4%) and used as received. Purified water (H2O) was obtained from a Millipore Milli-Q system (resistivity ≥18 MΩ·cm) and ethanol (EtOH) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (p.a., absolute, ≥ 99.8%). To prevent evaporation especially when EtOH was present in the mixture, the trough was cooled down to 278 ± 1 K and the temperature constantly monitored.

Sum Frequency Generation Spectroscopy

Sum frequency generation (SFG) is a second-order nonlinear optical spectroscopy which is surface specific and sensitive to the molecular order thanks to symmetry selection rules, and chemically specific as different molecular vibrational modes present different characteristic frequencies.

The SFG laser system consists of a seed and pump laser, a regenerative amplifier, and an optical parametric amplifier (OPA). As a seed, a Ti:sapphire laser (Mai Tai, Spectra Physics) is used. Pulses coming from the Mai Tai (∼40 fs duration) are stretched in time. Selected pulses are then directed into the regenerative amplifier (Spitfire Ace, Spectra Physics). A Nd:YLF laser (Empower 45, Spectra Physics) pumps the Ti:sapphire crystal in the amplifier. After amplification selected pulses are guided in the compressor which shortens them in time close to their original duration. Afterward the pulses (1 kHz repetition rate, ∼800 nm wavelength) are directed out of the Spitfire Ace. The output beam (∼5 mJ) is divided in two beams. One beam passes through the etalon (SLS Optics) to produce a narrowband visible (VIS) beam (fwhm ∼15 cm–1). The other beam is used to pump the OPA (TOPAS-C, Light Conversion) where by difference frequency generation the broadband infrared (IR) beam is generated. The IR and VIS are then focused and overlapped in space and time at the air–solution interface. The reflected SFG signal is collimated, and directed on the spectrometer slit (Acton SpectraPro 300i, Princeton Instruments). The SFG signal is finally detected by an electron-multiplied charge coupled device camera (Newton EMCCD 971P–BV, Andor Technology). The polarization state of all beams is controlled by polarizers and half-wave plates. In all experiments ssp (s-polarized SFG, s-polarized VIS, p-polarized IR) polarization combination was used (where p/s denotes the polarization parallel/perpendicular to the plane of incidence defined by the direction of incidence of the beam and the perpendicular to the interface).

For SFG experiments the sample was held inside an enclosed box continuously flushed with nitrogen to prevent absorption of the infrared radiation by air. For each sample, first the spectrum for the mixture without the peptide (10 min acquisition time) was acquired. Following the injection of the peptide and a 30 min equilibration period, another spectrum was acquired (10 min acquisition time) in the presence of the peptide. Afterward, the IR beam was blocked and a 10 min background spectrum was collected (mainly, for the correction of the CCD camera offset). Correction for the spectral shape of the infrared beam was performed by dividing each background corrected SFG spectrum by that of a background corrected spectrum of a z-cut quartz crystal.

For SFG experiments 5.1 mg/mL peptide stock solutions was prepared in various H2O/EtOH ratios and 0.1 mL of such solution was added to the trough already containing 5 mL of H2O/EtOH mixture as to a final peptide concentration of 58 μM (0.1 mg/mL).

Surface Pressure Measurements

For the surface pressure (SP) measurements a DeltaPi tensiometer (KBN 315 Sensor Head, Kibron Inc.) was used. Surface pressure curves were collected up to the moment when the surface pressure stabilized. The sample preparation procedure and concentrations were the same as reported above for the SFG experiments.

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

For circular dichroism (CD) experiments30 58 μM solutions of the peptide in various H2O/EtOH mixtures were prepared. Measurements were performed using a Jasco J-1500 CD spectrometer at room temperature (295 ± 2 K) using cuvettes made of quartz SUPRASIL (Hellma Analytics, light path length l = 1 mm).

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

All experiments reported here were recorded on a BRUKER 850 MHz Avance III system equipped with a 5 mm triple resonance TXI 1H/13C/15N probe with a z-gradient at 278.0 ± 0.1 K. The temperature was calibrated with a standard 1H methanol NMR sample using the TopSpin software (Bruker). Through-bond connectivity was obtained from a 2D Total Correlation Spectroscopy (TOCSY) spectrum recorded with the MLEV-17 mixing scheme31 with H2O suppression using 3–9–19 pulse sequence with gradients,32,33 using a 13 μs 90° pulse and a 80 ms mixing period. NMR spectra were processed using Topspin 3.6. Solutions of the peptide were prepared in water (H2O/D2O = 9:1 vol/vol mixture) and in totally deuterated ethanol. D2O was purchased from Eurisotop (99.9% D) and totally deuterated ethanol (CD3CD2OD) was purchased from Roth (Ethanol D6, 99 Atom% D). The peptide concentration was 2.9 mM, as the signal from the 58 μM solutions was too low.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

The simulations were done with the Gromacs suit of programs (versions 5 and later).34,35 The peptide was described with the Amber ff03 force field36 with a torsional correction for TIP4P/2005 water.37 All six LYS residues were charged and chloride counterions were used for charge neutralization. The general amber force field GAFF38,39 was used for EtOH and for the counterions, and H2O molecules were described with TIP4P/2005.40 All nonpolar hydrogen atoms were described as virtual sites, and all remaining bond lengths were constrained using the LINCS algorithm.41 The long-range electrostatic interactions were calculated using smooth particle-mesh Ewald (PME) summation42 with a grid spacing of 0.12 nm and fourth-order interpolation, and the Lennard-Jones interactions were smoothly cut off at a distance of 1.0 nm.

Two types of simulations were performed: bulk simulations and simulations in which a liquid–air interface was present. In both cases 12 different mixtures were simulated with EtOH volume fractions fEtOH between 0 and 1 as presented in Table 1. The bulk simulations were performed at a temperature of 300 K and an isotropic pressure of 1 bar using a stochastic velocity-rescaling thermostat43 and a Parrinello–Rahman barostat,44 both with time constant of 1 ps, and the time step was 5 fs. The total simulation time was 10 μs. Cubic boxes with a box length of 5 nm that contained one LKα14 peptide molecule were studied. Two simulations were performed for each composition, one starting from a helical conformation of the peptide and one starting from a disordered conformation. These two conformations took 5 μs to converge to the same secondary structure distribution at each fEtOH and as such only the last 5 μs were used for secondary structure analysis. Bulk simulations were also performed at a reduced temperature of 278.15 K to match the experimental conditions. These simulations had a length of 900 ns. No difference was seen between the two temperatures except in equilibration speed. Since the secondary structure equilibrates faster at the higher temperature and even at 300 K equilibrating the secondary structure is quite resource intensive, simulations at 300 K were used to analyze the secondary structure. For all simulations the secondary structure of the peptide was analyzed using STRIDE.45

Table 1. H2O/EtOH Mixtures Studied in MD Simulationsa.

| bulk |

interface |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fEtOH | xEtOH | NEtOH | NH2O | NEtOH | NH2O |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 3912 | 0 | 31 299 |

| 0.100 | 0.033 | 112 | 3538 | 976 | 28 304 |

| 0.264 | 0.1 | 330 | 2970 | 2643 | 23 787 |

| 0.447 | 0.2 | 554 | 2216 | 4435 | 17 740 |

| 0.581 | 0.3 | 720 | 1680 | 5754 | 13 426 |

| 0.682 | 0.4 | 842 | 1263 | 6740 | 10 140 |

| 0.764 | 0.5 | 938 | 938 | 7503 | 7503 |

| 0.829 | 0.6 | 1023 | 682 | 8178 | 5452 |

| 0.883 | 0.7 | 1085 | 465 | 8647 | 3707 |

| 0.921 | 0.8 | 1128 | 282 | 9024 | 2256 |

| 0.987 | 0.9 | 1179 | 131 | 9419 | 1043 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1253 | 0 | 10 024 | 0 |

Volume fractions fEtOH, and corresponding molar fractions xEtOH, of EtOH in H2O/EtOH mixtures and the respective number of molecules in the bulk and interface simulations.

Simulations of the air–liquid interface were performed at a temperature of 300 K using a stochastic velocity-rescaling thermostat43 with time constant of 1 ps. The time step was 2.5 fs. 900 ns were simulated. The PME calculation was done using a correction for slab geometry.46 For each simulation a 10 nm × 10 nm × 10 nm box of solution containing 20 peptides was equilibrated at 300 K and 1 bar using a stochastic velocity-rescaling thermostat43 and a Parrinello–Rahman barostat.44 The equilibrated box was then inserted into the middle of a 10 nm × 10 nm × 30 or 10 nm × 10 nm × 40 nm simulation box with vacuum on either side.

For the simulations of the interface, the secondary structure of every peptide was determined using STRIDE.45 For each helix an axis was fitted through this helix47,48 and the average angle φ between this axis and the interfacial plane was determined. The partial density of each component was determined along the surface normal (z-axis). From the density profile of the peptides, a surface region thickness of 1.5 nm was chosen. The average number of peptides and their average tilt angle relative to the surface, φ, were determined for the bulk region and for the surface region based on the geometrical center of the peptide.

Results and Discussion

LKα14 Location

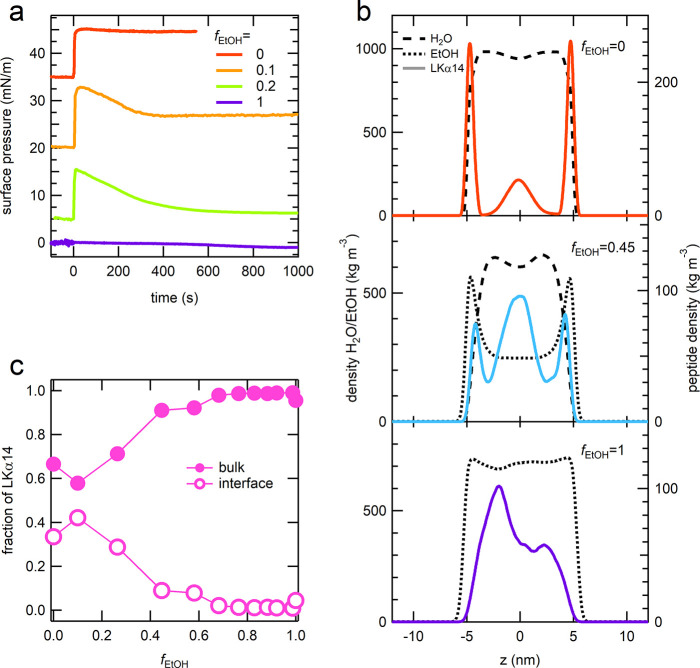

We have employed SP measurements and MD simulations to find the preferential location (bulk solution or air–liquid interface) for the different H2O/EtOH mixtures. The same amount of LKα14 peptide stock solution was injected in solutions containing different ratios of H2O/EtOH as reported in Figure 1a. The point in time at which the injection was performed has been chosen as t = 0. The surface pressure value has been set to zero for each mixture before the injection of the peptide. In the case of pure H2O (fEtOH = 0) an instantaneous jump of ∼10 mN/m in surface pressure is observed upon injection indicating fast adsorption of LKα14 to the air-H2O interface. When EtOH is present in the mixture we still observe a jump in the surface pressure upon peptide injection, which after some time stabilizes at ∼6 mN/m (relative to that of the subphase) for the fEtOH = 0.1 mixture. This value is lower than that observed for the pure H2O subphase. Interestingly, if the relative content of EtOH in the mixture is further increased, as for instance observed for fEtOH = 0.2, at the moment of the LKα14 peptide injection a fast increase in surface pressure is observed; however, in a short time, the surface pressure decreases and stabilizes at the end of the equilibration process at ∼0 mN/m, which suggests that the peptide leaves the interface and goes into the solution bulk. In the case of pure EtOH (fEtOH = 1) no change of surface pressure is observed upon injection of the peptide, suggesting a very low propensity of LKα14 for the EtOH–air interface.

Figure 1.

(a) Surface pressure curves for the LKα14 peptide in different H2O/EtOH mixtures with fEtOH = (red) 0, (orange) 0.1, (green) 0.2, (purple) 1. The peptide was injected at t = 0. The surface pressure was set to zero before the peptide injection and the curves are vertically offset for clarity. (b) Partial densities of the LKα14 peptide and the solvent components obtained from MD simulations for fEtOH= (top) 0, (middle) 0.45, and (bottom) 1. (c) Fraction of LKα14 peptide molecules located in (filled circles) bulk or (empty circles) at the air–solution interface for different EtOH volume fractions, fEtOH, according to MD simulations.

The different location of the peptide (bulk vs interface) is also captured in the MD simulations. The partial density in a pure H2O (top), pure EtOH (bottom), and in a mixture with an EtOH volume fraction of fEtOH = 0.45 are reported in Figure 1b. The preferential location at the solution–air interface is very prominent in H2O, where high peaks in the two interfacial regions are present. Following the interfacial adsorption peaks, distinct depleted regions show up before the bulk solution state in the center of the slab is reached. In pure EtOH, no distinct surface population of the peptide is present: the peptide density increases continuously until the bulk solution is reached approximately 4 nm beyond the interface, where the peptide density is maximal. We note at this point that our simulations, in which two interfaces are present, should yield symmetric density profiles. This is qualitatively the case, but a quantitative match is very difficult to achieve because of slow relaxation times. Therefore, we averaged over both interfaces for the quantitative analysis. For H2O/EtOH mixtures, the situation becomes more complicated, because EtOH itself is enriched in the interfacial region, consistent with reported results.49,50 For the density profile of the peptide, we observe an intermediate behavior between that in pure H2O and that in pure EtOH. At a volume fraction of fEtOH = 0.45, the interfacial adsorption peaks are less pronounced and the bulk density increases accordingly. These peptide density distributions for various H2O/EtOH mixtures were further used to calculate the fraction of peptide molecules present at the air–liquid interface and in bulk solution (see Figure 1c). The data clearly show that the LKα14 peptide’s interfacial adsorption decreases upon increase of EtOH fraction in solution.

The consistent results from SP measurements and MD simulations suggest that solvation of LKα14 is more favorable in EtOH than in H2O: This result can be understood looking at the amphiphilicity of the peptide. In pure H2O, the hydrophobic leucine (L) residues of LKα14 drive the peptide to the air–solution interface, while in EtOH the amphiphilic nature of the solvent favors the residence of the amphiphilic peptide in bulk solution.

LKα14 Secondary Structure

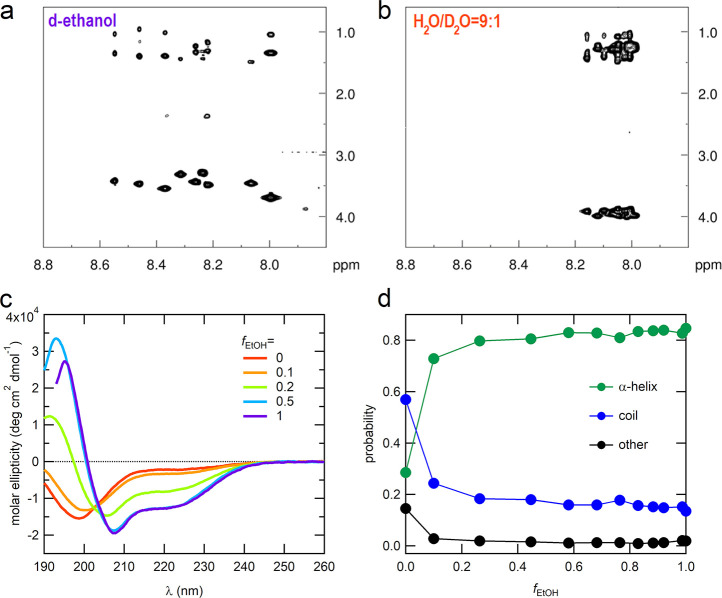

CD, 2D TOCSY and MD simulations were used to study the LKα14 conformation in bulk solution. The 2D TOCSY spectrum of LKα14 in pure fully deuterated ethanol in Figure 2a shows a broad signal distribution (8−8.6 ppm) indicating a highly organized and stable structure. This becomes even more evident when compared to the 2D TOCSY spectrum of LKα14 in H2O/D2O = 9:1 water (7.98−8.18 ppm) in Figure 2b, where the presence of small signal distributions and highly overlapping crosspeaks indicate a random-coil like structure.

Figure 2.

1H1H-TOCSY NMR spectra showing the crosspeak region of the backbone amide protons with the Hα and side-chain protons of LKα14 (a) in fully deuterated ethanol and (b) in water (H2O/D2O = 9:1). (c) CD spectra for different H2O/EtOH mixtures; the different colors indicate fEtOH = (red) 0, (orange) 0.1, (green) 0.2, (blue) 0.5, and (purple) 1 solutions. (d) Probabilities of different secondary structural motifs in bulk solution for different mixtures as obtained from MD simulations: (green) α-helix, (blue) random coil, and (black) other structures.

The CD spectra for the LKα14 in various H2O/EtOH mixtures are shown in Figure 2c. In agreement with TOCSY the CD spectra of LKα14 in pure H2O bulk solution (red curve) shows that LKα14 assumes a mostly random coil conformation while in EtOH (purple curve) an α-helical one. For the mixtures it is observed that the fraction of α-helical conformation increases considerably up to fEtOH = 0.5. Above fEtOH = 0.5, when the EtOH content in solution is further increased, a much smaller change is observed. The experimental results are also supported by the MD simulations (Figure 2d) where it is observed that the secondary structure in bulk is dominated by the random-coil conformation only in pure H2O while the α-helical conformation is the most frequent conformation in the presence of EtOH. Already at the very low EtOH content of fEtOH = 0.1, the probability of finding the peptide in an α-helical conformation in bulk solution is 0.8. Thus, only at very low EtOH content (fEtOH < 0.1) it is possible to observe a predominant unfolded conformation. We conclude that our MD force field predicts the unfolding transition to occur at a slightly lower EtOH content relative to the experimental results.

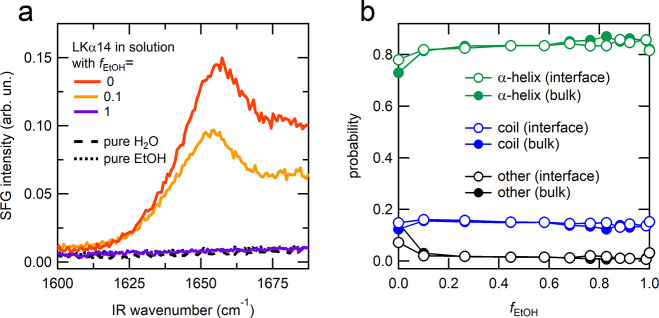

In order to study the conformation of LKα14 at the solution–air interface we used SFG spectroscopy.51−54 The acquired SFG spectrum for LKα14 in pure D2O in the CH-stretching region (see Supporting Information (SI) Figure S1) is similar to that reported for leucine molecules at the air–water interface19 in agreement with previous studies.18 In Figure 3a the SFG spectra in the amide I region acquired after equilibration (∼30 min) are reported for different mixtures. The amide I vibrational response (being mostly from the carbonyl stretch of the amide bond) originates from the peptide/protein backbone55 and carries information about the secondary structure of the interfacial peptide/protein molecules.53,56 A pronounced amide I signal is observed for LKα14 in pure H2O (red curve) at ∼1650 cm–1 which has been assigned to the α-helical conformation of the peptide at the air–H2O interface.18 This peak is also observed when the peptide is injected in H2O/EtOH mixture with fEtOH = 0.1 (orange curve) and is due to the LKα14 peptides that reside at the air–solution interface. As expected, based on the surface pressure results, no amide I signal is observed in pure EtOH (purple curve), as LKα14 is not present at the interface and the same holds true for mixtures with fEtOH = 0.5 and 0.2. When comparing the spectra, the amide I peak position for the H2O/EtOH mixture corresponding to fEtOH = 0.1 appears red-shifted compared to that in pure H2O. However, by fitting the data (see SI Table S1 and Figure S2) it can be seen that the peak position does not shift and that it is instead an effect due to the higher background present at high frequency in pure H2O compared to the fEtOH = 0.1 mixture (see the comments on the high-frequency shoulder contribution in SI Section S2). Therefore, it is not possible to conclude whether the presence of 10% EtOH in the mixture affects the conformation of the LKα14 peptides present at the solution–air interface, and this is further complicated by the fact that the random-coil conformation peak would appear at the same frequency as that of the α-helix.21,53 The interfacial MD simulations show that unfolded peptides are rarely present in the bulk interior (Figure 3b, filled circles). However, since the simulation times of the interfacial system might be smaller than the folded state lifetimes, we cannot exclude that unfolding can occur both in the bulk interior and at the interface.

Figure 3.

(a) SFG spectra in the amide I region acquired after equilibration (∼30 min) following the peptide injection in different mixtures. The spectra in this region in absence of LKα14 are shown for (black dashed line) H2O and (black dotted line) EtOH as reference. (b) Relative probability of different secondary structures (empty circles) at the interface and (filled circles) in bulk for different mixtures as obtained from MD simulations.

Based on the collected data, we propose that EtOH is not only a good choice of solvent for LKα14, but its presence in the mixture also allows the stabilization of the peptide in an α-helical conformation similarly to what happens in the case of pure H2O only at the interface with air.

LKα14 Orientation

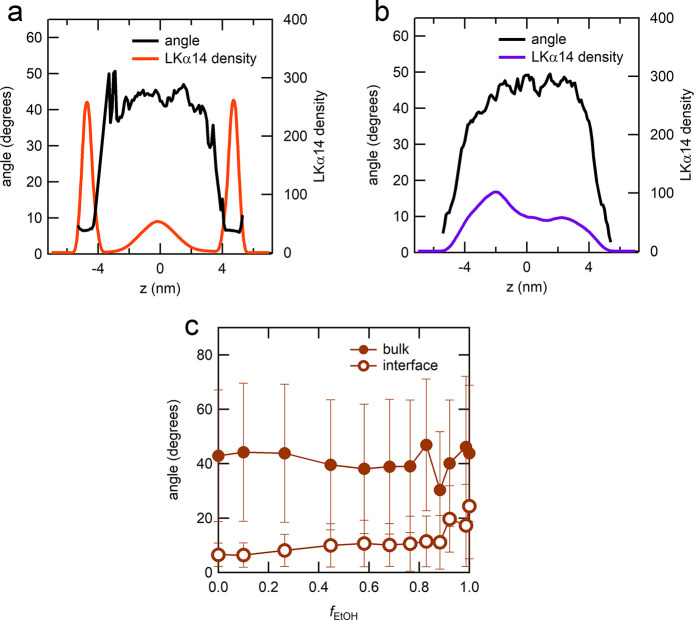

MD simulations were used to calculate the angle of the α-helical axis with respect to the interface. In pure H2O there is a sharp difference in the orientation between the surface and the bulk. At the air-H2O interface the helix orients with the helix-axis at an angle of ∼8 degrees (Figure 4a) with the plane of the interface, while in bulk there is no preferential orientation observed. Furthermore, longer bulk simulations show that in H2O bulk the helix unfolds. The surface region in which the angle is ∼8 degrees extends 1.5 nm away from the interfacial plane. In pure EtOH there is no sharp transition from the surface peptide population to the bulk population (Figure 4b). In pure EtOH, there is no distinct surface population with a distinctly oriented helix which can be observed in Figure 4c. The drops of the average angle in Figure 4b when the interfaces are approached are merely a consequence of the helices’ positional assignment based on their center of mass, which can only be consistent with a parallel alignment of molecules at the interface. Due to the very low density of peptides at the interfaces, the low average orientations are insignificant. Finally, we note that the peptides’ N-terminus in H2O preferentially points away from the interface toward the bulk solution (see SI Figure S3), which well matches the experimental results previously reported.25

Figure 4.

Average tilt angle between the helices and the interfacial plane in pure (a) H2O and (b) EtOH: black lines indicate the angle while the colored lines the peptide distribution. (c) Average angle (filled circles) in bulk and (empty circles) at the interface for different fEtOH. For a random distribution the angle averages at 45 deg.

Conclusions

The conformation of peptides/proteins can be strongly affected by solvation and can be substantially changed by regulating the content of alcohol in solution. In this work, we show that ethanol has a significant impact on the interfacial and bulk behavior of LKα14 affecting both the peptide location and folding. The water/ethanol ratio has been systematically varied and the behavior of the peptide has been compared to that in the pure solvents. First, we studied the interface/bulk affinity of LKα14 in the different mixtures. Based on the SP measurements and MD data, we can conclude that an increase of the ethanol content in the aqueous solutions decreases the peptide propensity for the interface in favor of the bulk. CD spectroscopy, NMR TOCSY, and MD simulations suggest that the conformation in pure water lacks any defined structure; however, as the content of ethanol increases, the peptide adopts an α-helical conformation. These results suggest that the α-helix stabilization is facilitated by hydrophobic/hydrophilic interactions between the peptide and the amphiphilic ethanol molecules. The bulk analysis of the peptide’s behavior was complemented by SFG studies at the air–solution interface. In pure water, the observation of a spectrum in the amide I region suggests an α-helical conformation and a net ordering of the LKα14 peptide molecules at the air–water interface consistent with previous studies.18,20,25 When 10% (vol) ethanol is present in solution, the SFG spectrum is quite similar to that observed in pure water, even though the signal intensity is lower consistent with a depletion of peptide molecules at the air–solution interface as suggested by the SP results. The information on the peptide molecular orientation at the interface was obtained by MD simulations. For the air–water interface, the helix-axis was found to be tilted ∼8 degrees relative to the surface with the N-terminus pointing toward the water phase, which is in agreement with the earlier reported result.25 We further found that the angle between the helix and the air–solution interface has a general tendency to increase when the content of ethanol increases. This effect can have different origins that are related to the molecular structure of the mixed solution interface. Though, we have detected some nonmonotonicity in the dependence of the tilt angle on the ethanol content. Such behavior could be related to complex aggregate formation in the mixed solution, which is not further addressed in this work.

From our results, it is apparent the importance of solvation. In fact, along with the amino-acid sequence, amino acid hydrophobicity, and the hydrophobic periodicity, the solvent determines the behavior of proteins/peptides in solution. Thus, the solvent cannot be treated as a passive bystander in inter- and intramolecular interactions, but is an active player which is able to change the interactions in the system to a substantial extent. In our work, we show for the model LKα14 peptide that ethanol can strongly affect the location and conformation of the peptide. We hypothesize that the high sensitivity of the peptide behavior to ethanol originates from the amphiphilic nature of the ethanol. The presence of ethanol in solution can stabilize particular structures in solution by hydrophobic and/or hydrogen bonding interactions. In our study we observe that ethanol promotes the secondary structure (α-helical) conformation of LKα14. Our work thus sheds light on how a combination of physical–chemical parameters can tip the equilibrium structure of a peptide/protein to the folded/unfolded state.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Ng for support with the CD instrument and Christoph Bernhard, Robert Graf, Manfred Wagner for fruitful discussions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c03132.

SFG spectrum for LKα14 in D2O in the CH-stretching region, SFG spectra fitting for the amide I spectral region, N-terminus orientation of the interfacial LKα14 molecules from interfacial MD simulations (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Prabhu N.; Sharp K. Protein-Solvent Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106 (5), 1616–1623. 10.1021/cr040437f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorin E. J.; Rhee Y. M.; Shirts M. R.; Pande V. S. The Solvation Interface Is a Determining Factor in Peptide Conformational Preferences. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 356 (1), 248–256. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoppola E.; Sodo A.; McLain S. E.; Ricci M. A.; Bruni F. Water-Peptide Site-Specific Interactions: A Structural Study on the Hydration of Glutathione. Biophys. J. 2014, 106 (8), 1701–1709. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck D. A. C.; Alonso D. O. V; Daggett V. A Microscopic View of Peptide and Protein Solvation. Biophys. Chem. 2002, 100 (1), 221–237. 10.1016/S0301-4622(02)00283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M.; Okamoto Y.; Hirata F. Peptide Conformations in Alcohol and Water: Analyses by the Reference Interaction Site Model Theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122 (12), 2773–2779. 10.1021/ja993939x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerig J. T. Investigation of Ethanol-Peptide and Water-Peptide Interactions through Intermolecular Nuclear Overhauser Effects and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117 (17), 4880–4892. 10.1021/jp4007526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattoraj S.; Mandal A. K.; Bhattacharyya K. Effect of Ethanol-Water Mixture on the Structure and Dynamics of Lysozyme: A Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy Study. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 140 (11), 115105. 10.1063/1.4868642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanta D.; Santra S.; Jana M. Conformational Disorder and Solvation Properties of the Key-Residues of a Protein in Water-Ethanol Mixed Solutions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19 (48), 32636–32646. 10.1039/C7CP06022J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGuiseppi D.; Milorey B.; Lewis G.; Kubatova N.; Farrell S.; Schwalbe H.; Schweitzer-Stenner R. Probing the Conformation-Dependent Preferential Binding of Ethanol to Cationic Glycylalanylglycine in Water/Ethanol by Vibrational and NMR Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121 (23), 5744–5758. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b02899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H.; Hirano A.; Arakawa T.; Shiraki K. Mechanistic Insights into Protein Precipitation by Alcohol. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 50 (3), 865–871. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaka R. S.; Renugopalakrishnan V.; Goehl T. J.; Collins B. J. Ethanol Induced Conformational Changes of the Peptide Ligands for the Opioid Receptors and Their Relevance to Receptor Interaction. Life Sci. 1986, 39 (9), 837–842. 10.1016/0024-3205(86)90463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiffo-Soh G.; Hernández B.; Coïc Y.-M.; Boukhalfa-Heniche F.-Z.; Ghomi M. Vibrational Analysis of Amino Acids and Short Peptides in Hydrated Media. II. Role of KLLL Repeats To Induce Helical Conformations in Minimalist LK-Peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111 (43), 12563–12572. 10.1021/jp074264k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Singh M. K.; Kremer K.; Cortes-Huerto R.; Mukherji D. Why Do Elastin-Like Polypeptides Possibly Have Different Solvation Behaviors in Water-Ethanol and Water-Urea Mixtures?. Macromolecules 2020, 53 (6), 2101–2110. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b02123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGrado W. F.; Lear J. D. Induction of Peptide Conformation at Apolar Water Interfaces. 1. A Study with Model Peptides of Defined Hydrophobic Periodicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107 (25), 7684–7689. 10.1021/ja00311a076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeGrado W. F.; Wasserman Z. R.; Lear J. D. Protein Design, a Minimalist Approach. Science (Washington, DC, U. S.) 1989, 243 (4891), 622–628. 10.1126/science.2464850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidner T.; Breen N. F.; Li K.; Drobny G. P.; Castner D. G. Sum Frequency Generation and Solid-State NMR Study of the Structure, Orientation, and Dynamics of Polystyrene-Adsorbed Peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107 (30), 13288–13293. 10.1073/pnas.1003832107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S.; Naka T. L.; Hore D. K. Enhanced Understanding of Amphipathic Peptide Adsorbed Structure by Modeling of the Nonlinear Vibrational Response. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117 (47), 24955–24966. 10.1021/jp409261m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz H.; Jaeger V.; Bonn M.; Pfaendtner J.; Weidner T. Acetylation Dictates the Morphology of Nanophase Biosilica Precipitated by a 14-Amino Acid Leucine-Lysine Peptide. J. Pept. Sci. 2017, 23 (2), 141–147. 10.1002/psc.2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji N.; Shen Y.-R. Sum Frequency Vibrational Spectroscopy of Leucine Molecules Adsorbed at Air-Water Interface. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120 (15), 7107–7112. 10.1063/1.1669375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L.; Liu J.; Yan E. C. Y. Chiral Sum Frequency Generation Spectroscopy for Characterizing Protein Secondary Structures at Interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (21), 8094–8097. 10.1021/ja201575e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L.; Wang Z.; Yan E. C. Y. Chiral Vibrational Structures of Proteins at Interfaces Probed by Sum Frequency Generation Spectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12 (12), 9404–9425. 10.3390/ijms12129404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgicdir C.; Sayar M. Conformation and Aggregation of LKalpha14 Peptide in Bulk Water and at the Air/Water Interface. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119 (49), 15164–15175. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b08871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozgur B.; Dalgicdir C.; Sayar M.. Correction to “Conformation and Aggregation of LKalpha14 Peptide in Bulk Water and at the Air/Water Interface. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123 ( (10), ), 2463–2465. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b01566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgicdir C.; Globisch C.; Peter C.; Sayar M. Tipping the Scale from Disorder to Alpha-Helix: Folding of Amphiphilic Peptides in the Presence of Macroscopic and Molecular Interfaces. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11 (8), 1–24. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmüser L.; Roeters S.; Lutz H.; Woutersen S.; Bonn M.; Weidner T. Determination of Absolute Orientation of Protein Alpha-Helices at Interfaces Using Phase-Resolved Sum Frequency Generation Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8 (13), 3101–3105. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchko G. W.; Jain A.; Reback M. L.; Shaw W. J. Structural Characterization of the Model Amphipathic Peptide Ac-LKKLLKLLKKLLKL-NH2 in Aqueous Solution with 2,2,2-Trifluoroethanol and 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoroisopropanol. Can. J. Chem. 2013, 91 (6), 406–413. 10.1139/cjc-2012-0429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palunas K.; Sprenger K. G.; Weidner T.; Pfaendtner J. Effect of an Ionic Liquid/Air Interface on the Structure and Dynamics of Amphiphilic Peptides. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 236, 404–413. 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.04.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Booth N. The Denaturation of Proteins. Biochem. J. 1930, 24 (6), 1699–1705. 10.1042/bj0241699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskovits T. T.; Gadegbeku B.; Jaillet H. On the Structural Stability and Solvent Denaturation of Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1970, 245 (10), 2588–2598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield N. Using Circular Dichroism Spectra to Estimate Protein Secondary Structure. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1 (6), 2876–2890. 10.1038/nprot.2006.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax A.; Davis D. G. MLEV-17-Based Two-Dimensional Homonuclear Magnetization Transfer Spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 1985, 65 (2), 355–360. 10.1016/0022-2364(85)90018-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piotto M.; Saudek V.; Sklenář V. Gradient-Tailored Excitation for Single-Quantum NMR Spectroscopy of Aqueous Solutions. J. Biomol. NMR 1992, 2 (6), 661–665. 10.1007/BF02192855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklenar V.; Piotto M.; Leppik R.; Saudek V. Gradient-Tailored Water Suppression for 1H-15N HSQC Experiments Optimized to Retain Full Sensitivity. J. Magn. Reson., Ser. A 1993, 102 (2), 241–245. 10.1006/jmra.1993.1098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen H. J. C.; van der Spoel D.; van Drunen R. GROMACS: A Message-Passing Parallel Molecular Dynamics Implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995, 91 (1), 43–56. 10.1016/0010-4655(95)00042-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pronk S.; Páll S.; Schulz R.; Larsson P.; Bjelkmar P.; Apostolov R.; Shirts M. R.; Smith J. C.; Kasson P. M.; van der Spoel D.; Hess B.; Lindahl E. GROMACS 4.5: A High-Throughput and Highly Parallel Open Source Molecular Simulation Toolkit. Bioinformatics 2013, 29 (7), 845–854. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y.; Wu C.; Chowdhury S.; Lee M. C.; Xiong G.; Zhang W.; Yang R.; Cieplak P.; Luo R.; Lee T.; Caldwell J.; Wang J.; Kollman P. A Point-Charge Force Field for Molecular Mechanics Simulations of Proteins Based on Condensed-Phase Quantum Mechanical Calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24 (16), 1999–2012. 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best R. B.; Mittal J. Protein Simulations with an Optimized Water Model: Cooperative Helix Formation and Temperature-Induced Unfolded State Collapse. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114 (46), 14916–14923. 10.1021/jp108618d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Wang W.; Kollman P. A.; Case D. A. Automatic Atom Type and Bond Type Perception in Molecular Mechanical Calculations. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2006, 25 (2), 247–260. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Wolf R. M.; Caldwell J. W.; Kollman P. A.; Case D. A. Development and Testing of a General Amber Force Field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25 (9), 1157–1174. 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abascal J. L. F.; Vega C. A General Purpose Model for the Condensed Phases of Water: TIP4P/2005. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123 (23), 234505. 10.1063/1.2121687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B. P-LINCS: A Parallel Linear Constraint Solver for Molecular Simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4 (1), 116–122. 10.1021/ct700200b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essmann U.; Perera L.; Berkowitz M. L.; Darden T.; Lee H.; Pedersen L. G. A Smooth Particle Mesh Ewald Method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103 (19), 8577–8593. 10.1063/1.470117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bussi G.; Donadio D.; Parrinello M. Canonical Sampling through Velocity Rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126 (1), 14101. 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello M.; Rahman A. Polymorphic Transitions in Single Crystals: A New Molecular Dynamics Method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 52 (12), 7182–7190. 10.1063/1.328693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heinig M.; Frishman D. STRIDE: A Web Server for Secondary Structure Assignment from Known Atomic Coordinates of Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32 (suppl_2), W500–W502. 10.1093/nar/gkh429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh I.-C.; Berkowitz M. L. Ewald Summation for Systems with Slab Geometry. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 111 (7), 3155–3162. 10.1063/1.479595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn P. C. Defining the Axis of a Helix. Comput. Chem. 1989, 13 (3), 185–189. 10.1016/0097-8485(89)85005-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn P. C. Simple Methods for Computing the Least Squares Line in Three Dimensions. Comput. Chem. 1989, 13 (3), 191–195. 10.1016/0097-8485(89)85006-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarek M.; Tobias D. J.; Klein M. L. Molecular Dynamics Investigation of an Ethanol-Water Solution. Phys. A 1996, 231 (1), 117–122. 10.1016/0378-4371(95)00450-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phan C. M.; Nguyen C. V.; Pham T. T. T. Molecular Arrangement and Surface Tension of Alcohol Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120 (16), 3914–3919. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b01209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y. R.Fundamentals of Sum-Frequency Spectroscopy; Cambridge Molecular Science; Cambridge University Press, 2016. 10.1017/CBO9781316162613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bain C. D. Sum-Frequency Vibrational Spectroscopy of the Solid/Liquid Interface. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1995, 91 (9), 1281–1296. 10.1039/ft9959101281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinpour S.; Roeters S. J.; Bonn M.; Peukert W.; Woutersen S.; Weidner T. Structure and Dynamics of Interfacial Peptides and Proteins from Vibrational Sum-Frequency Generation Spectroscopy. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120 (7), 3420–3465. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert A. G.; Davies P. B.; Neivandt D. J. Implementing the Theory of Sum Frequency Generation Vibrational Spectroscopy: A Tutorial Review. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2005, 40 (2), 103–145. 10.1081/ASR-200038326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barth A.; Zscherp C. What Vibrations Tell about Proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2002, 35 (4), 369–430. 10.1017/S0033583502003815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsbach S.; Gonella G.; Mailänder V.; Wegner S.; Wu S.; Weidner T.; Berger R.; Koynov K.; Vollmer D.; Encinas N.; Kuan S. L.; Bereau T.; Kremer K.; Weil T.; Bonn M.; Butt H.-J.; Landfester K. Engineering Proteins at Interfaces: From Complementary Characterization to Material Surfaces with Designed Functions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (39), 12626–12648. 10.1002/anie.201712448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.