Version Changes

Updated. Changes from Version 1

This update of our living systematic reviews includes literature up to October 2020 whereas our last was up to 7th June 2020. Searches identified 6,226 articles. Seventy-eight articles met our revised inclusion criteria, 49 more than in our previous review. All were still based on observational studies. The majority of studies remained case series but there are now an increased number of service utilisation studies from across the world. There were still no studies were based on populations from sub-saharan Africa. In contrast to the last update in which no studies reported on the change in incidence of suicide or suicidal behaviour after the onset of the pandemic compared with beforehand, we identified nine papers in this update, presenting data on studies from four countries which investigated the impact of COVID-19 on suicide rates. To date, the highest quality data come from Japan which utilises suicide records covering the entire population; these data indicate that the impact of COVID-19 on suicides rates may change over time and have varying effects on different sections of the population. There was no consistent evidence of a rise in suicide but many studies noted adverse economic effects were evolving. There was evidence of a rise in community distress, fall in hospital presentation for suicidal behaviour and early evidence of an increased frequency of suicidal thoughts in those who had become infected with COVID-19. We have updated the author order to reflect contribution to this update, predominately related to oversight of specific tables and drafting specific sections of text. We have added new authors who have joined the screening team.

Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has caused considerable morbidity, mortality and disruption to people’s lives around the world. There are concerns that rates of suicide and suicidal behaviour may rise during and in its aftermath. Our living systematic review synthesises findings from emerging literature on incidence and prevalence of suicidal behaviour as well as suicide prevention efforts in relation to COVID-19, with this iteration synthesising relevant evidence up to 19 th October 2020.

Method: Automated daily searches feed into a web-based database with screening and data extraction functionalities. Eligibility criteria include incidence/prevalence of suicidal behaviour, exposure-outcome relationships and effects of interventions in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. Outcomes of interest are suicide, self-harm or attempted suicide and suicidal thoughts. No restrictions are placed on language or study type, except for single-person case reports. We exclude one-off cross-sectional studies without either pre-pandemic measures or comparisons of COVID-19 positive vs. unaffected individuals.

Results: Searches identified 6,226 articles. Seventy-eight articles met our inclusion criteria. We identified a further 64 relevant cross-sectional studies that did not meet our revised inclusion criteria. Thirty-four articles were not peer-reviewed (e.g. research letters, pre-prints). All articles were based on observational studies.

There was no consistent evidence of a rise in suicide but many studies noted adverse economic effects were evolving. There was evidence of a rise in community distress, fall in hospital presentation for suicidal behaviour and early evidence of an increased frequency of suicidal thoughts in those who had become infected with COVID-19.

Conclusions: Research evidence of the impact of COVID-19 on suicidal behaviour is accumulating rapidly. This living review provides a regular synthesis of the most up-to-date research evidence to guide public health and clinical policy to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on suicide risk as the longer term impacts of the pandemic on suicide risk are researched.

Keywords: COVID-19, Living systematic review, Suicide; Attempted suicide, Self-harm, Suicidal thoughts

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is causing widespread societal disruption, morbidity and loss of life globally. By the end of December 2020 over 85 million people had been infected and over 1.8 million had died ( Worldometers, 2020). There are concerns about the impact of the pandemic on population mental health ( Holmes et al., 2020). These stem from the impact of the virus itself on people infected ( Taquet et al., 2021), as well as frontline workers caring for them ( Kisely et al., 2020) and increases in bereavement. Other concerns relate to the impact on population mental health of the public health measures that have been implemented to minimise the spread of the virus – in particular physical distancing, leading to social isolation, disruption of businesses, services and education and threats to peoples’ livelihoods. Physical distancing measures and lockdowns have resulted in substantial rises in unemployment, falls in GDP and concerns that many nations will enter a prolonged period of deep economic recession.

There are concerns that suicide and self-harm rates may rise during and in the aftermath of the pandemic ( Gunnell et al., 2020; Reger et al., 2020). Time-series modelling indicated that the 1918–20 Spanish Flu pandemic, which caused well over 20 million deaths worldwide, led to a modest rise in the national suicide rate in the USA ( Wasserman, 1992) and Taiwan ( Chang et al., 2020). Likewise, there is some evidence that previous epidemics and pandemics were associated with rises in suicide and suicidal behaviour ( Zortea et al., 2020). Suicide rates increased briefly amongst people aged over 65 years in Hong Kong during the 2003 SARS epidemic, predominantly amongst those with more severe physical illness and physical dependency ( Cheung et al., 2008).

The current context is, however, very different from previous epidemics and pandemics. The 2003 SARS epidemic was restricted to relatively few countries. Furthermore, during the 100-year period since the 1918–20 influenza pandemic, global and national health systems have improved, international travel and the speed of communication of information (and disinformation) have increased, antibiotics are available to treat secondary infection, and national economies have become globally inter-dependent. The availability of the internet and technological advancement has made it far easier for people to communicate and engage in home working and home schooling. However, there are marked social inequalities in relation to access to technology and ability to stay safe and continue to work, within and between countries. Public health policies and responses, and the degree of access to technology to facilitate online clinical assessments and treatments differ greatly between countries.

Key concerns in relation to suicide prevention during the pandemic include: encouraging help-seeking in those with suicidal thoughts and behaviours e.g. people who have attempted suicide may not attend hospitals because they are worried about contracting COVID-19 or being a burden on the healthcare system at this time; uncertainty regarding how best to assess and support people with suicidal thoughts and behaviours, whilst maintaining physical distancing and addressing any impacts of remote consultation; diminished access to community-based support; exposure to traumatic experiences; long term effect of infection with the virus on mental health ( Taquet et al., 2021) and an economic recession may have an adverse impact on suicide rates ( Chang et al., 2013; Stuckler et al., 2009). There have been increases in bereavement (with many being unusually complicated during the crisis), sales of alcohol ( Finlay & Gilmore, 2020) and domestic violence ( Mahase, 2020) – all risk factors for suicide ( Turecki et al., 2019); the insensitive or irresponsible media reporting of suicide deaths associated with COVID-19 may be harmful ( Hawton et al., 2021); and in some countries access to highly lethal suicide methods such as firearms and pesticides may rise ( Anestis et al., 2021; Gunnell et al., 2020). However early findings from high income countries with ‘real-time’ suicide trend data, indicates there was no rise in suicide rates in the early months of the pandemic ( John et al., 2020a). Japan is the exception to this rule, falls in Japanese suicide rates in the early months of the pandemic have since been replaced by rises above pre-pandemic levels July/August 2020 and beyond ( John et al., 2020a; Tanaka & Okamoto, 2021; Ueda et al., 2021). The longer-term impact of the pandemic on suicide deaths and suicidal behaviour remains uncertain.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic there is a rapidly expanding evidence base on its impact on suicide rates, and how best to mitigate such effects. It is therefore important that the best available knowledge is made rapidly available to policymakers, public health specialists and clinicians. To facilitate this, we are conducting a living systematic review focusing on incidence and prevention of suicide and self-harm in relation to COVID-19. Living systematic reviews are high-quality, up-to-date online summaries of research that are regularly updated, using efficient, often semi-automated, systems of production ( Elliott et al., 2014). Our first report covered the period up to the 7 th June 2020. This paper reports the second set of findings from the review, based on relevant articles identified up to 19 th October 2020.

Aim

The overarching aim of the review is to identify and appraise any newly published evidence from around the world that assesses the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide deaths, suicidal behaviours, self-harm and suicidal thoughts, or that assesses the effectiveness of strategies to reduce the risk of suicide deaths, suicidal behaviours, self-harm and suicidal thoughts, associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

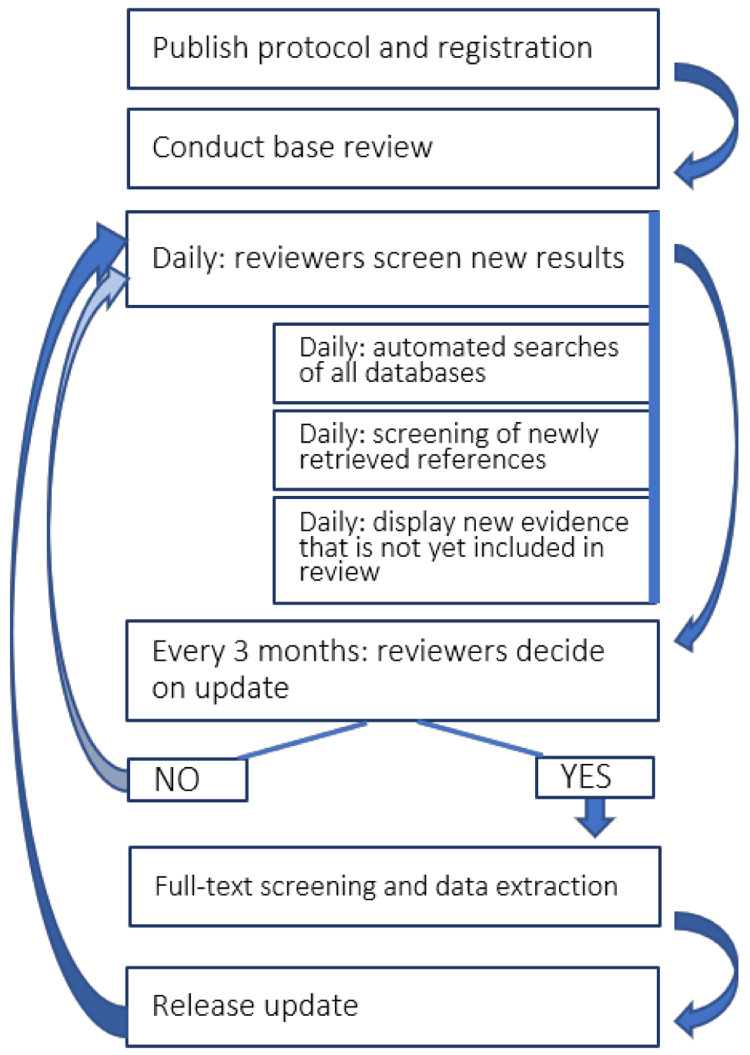

This living systematic review ( Figure 1) follows published guidance for such reviews and for how expedited ‘living’ recommendations should be formulated where relevant ( Akl et al., 2017; Elliott et al., 2017). The review was prospectively registered (PROSPERO ID CRD42020183326; registered on 1 st May 2020). An overview of our living review process is provided in Figure 1. A protocol ( John et al., 2020b) was published in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols guideline ( Moher et al., 2015) along with the first update of our review which summarised articles identified up to 7 th June 2020 ( John et al., 2020c). Since publication of our protocol we have amended our methodology to: 1) search additionally the PsyArXiv and SocArXiv open access paper repositories; 2) include modelling studies within the scope of our review (e.g. to predict the likely impact of the pandemic on suicide rates); 3) update our research questions to include studying the impact of adult self-neglect and parental neglect and fear of losing livelihood on suicide-related outcomes; 4) update our searches with any new citations from PsycINFO prior to each update; 5) exclude from data extraction and presentation in results tables single-wave, cross-sectional surveys unless they explicitly make comparisons with appropriate pre-pandemic measures or include comparative data between COVID-19 positive and unaffected individuals for pragmatic reasons, due to the volume of such studes but also issues to do with sampling and generalisability of such studies. Surveys that meet the original inclusion criteria are included as an appendix to the update.

Figure 1. Workflow for updating the living systematic review review.

The process will be supported using automation technology and at three-monthly intervals the team will update the published version of the review.

Eligibility criteria

Study participants may be adults or children of any ethnicities living in any country. Outcomes of interest are:

-

1.

Deaths by suicide

-

2.

Self-harm (intentional self-injury or self-poisoning regardless of motivation and intent) or attempted suicide (including hospital attendance and/or admission for these reasons)

-

3.

Suicidal thoughts/ideation

Studies must address one of the following research questions:

(i) What is the prevalence/incidence?

Prevalence/incidence of each outcome during pandemic (including modelling studies)

(ii) What is the comparative prevalence/incidence?

Prevalence/incidence of each outcome during pandemic vs not during pandemic

(iii) What are the effects of interventions?

Effects of public health measures to combat COVID-19 (including physical distancing, school closures, interventions to address loss of income, interventions to tackle domestic violence) on each outcome

Effects of changed and new approaches to clinical management of (perceived) elevated risk of self-harm or suicide risk on each outcome (any type of intervention is relevant)

(iv) What are the effects of other exposures?

Impact of media portrayal on each outcome and misinformation attributed to the pandemic on each outcome

Impact of bereavement from COVID-19 on each outcome

Impact of any COVID-19 related behaviour changes (domestic violence, alcohol, adult self-neglect, parental neglect, cyberbullying, isolation) on each outcome

Impact of COVID-19-related workload on crisis lines on each outcome

Impact of infection with COVID-19 (self or family member) on each outcome

Impact of changes in availability of analgesics, firearms and pesticides on each outcome (method-specific and overall suicide rates)

Impact of COVID-19 related socio-economic exposures (changes in fiscal policy; recession/depression: unemployment, debt, fear of losing livelihood, deprivation at the person-, family- or small-area level) on each outcome

Impact on health and social care professionals: the stigma of working with COVID-19 patients or the (perceived) risk of infection/being a ‘carrier’, as well as work-related stress on each outcome

Impact of changes in/reduced intensity of treatment for patients with mental health conditions, in particular those with severe psychiatric disorders.

Impact of any other relevant exposure on our outcomes of interest.

Qualitative research

We included any qualitative research addressing perceptions or experiences around each outcome in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. stigma of infection, isolation measures, complicated bereavement, media reporting, experience of delivering or receiving remote methods of self-harm / suicide risk assessment or provision of treatment; experience of seeking help for individuals in suicidal crisis); narratives provided for precipitating factors for each outcome.

No restrictions were placed on the types of study design eligible for inclusion, except for the exclusion of single-person case reports. Pre-prints will be re-assessed at the time of publication and the most current version included. There was no restriction on language of publication. We drew on a combination of internet-based translation systems and network of colleagues to translate reports in languages other than English.

Identification of eligible studies

We searched the following electronic databases: PubMed; Scopus; medRxiv, PsyArXiv; SocArXiv; bioRxiv; the COVID-19 Open Research Dataset (CORD-19) by Semantic Scholar and the Allen Institute for AI, which includes relevant records from Microsoft Academic, Elsevier, arXiv and PMC; and the WHO COVID-19 database. A sample search strategy (for PubMed) appears in Box 1 from 1 st January 2020 to 19 th October 2020. We have developed a workflow that automates daily searches of these databases, and the code supporting this process can be found at https://github.com/mcguinlu/COVID_suicide_living). Searches are conducted daily via PubMed and Scopus application programme interface and the bioRxiv and medRxiv RSS feeds. Conversion scripts for the daily updated WHO and the weekly updated CORD-19 corpus are used to collect information from the remaining sources. The software includes a systematic search function based on regular expressions to search results retrieved from the WHO, CORD-19 and preprint repositories (search strategy available in extended data). Our review is ongoing and we continue to investigate the use of other databases and to capture articles made available prior to peer review and assess eligibility and review internally. For this update we therefore included PsyArXiv and SocArXiv repositories in our search strategy via their own open access platforms as we developed our automated system. PsycINFO searches were carried out retrospectively on 6 th January 2021, using a publication date filter for 1 st January 2020 to 19 th October 2020.

Box 1. Search terms for PubMed.

((selfharm*[TIAB] OR self-harm*[TIAB] OR selfinjur*[TIAB] OR self-injur*[TIAB] OR selfmutilat*[TIAB] OR self-mutilat*[TIAB] OR suicid*[TIAB] OR parasuicid*[TIAB) OR (suicide[TIAB] OR suicidal ideation[TIAB] OR attempted suicide[TIAB]) OR (drug overdose[TIAB] OR self?poisoning[TIAB]) OR (self-injurious behavio?r[TIAB] OR self?mutilation[TIAB] OR automutilation[TIAB] OR suicidal behavio?r[TIAB] OR self?destructive behavio?r[TIAB] OR self?immolation[TIAB])) OR (cutt*[TIAB] OR head?bang[TIAB] OR overdose[TIAB] OR self?immolat*[TIAB] OR self?inflict*[TIAB]))) AND ((coronavirus disease?19[TIAB] OR sars?cov?2[TIAB] OR mers?cov[TIAB]) OR (19?ncov[TIAB] OR 2019?ncov[TIAB] OR n?cov[TIAB]) OR ("severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2" [Supplementary Concept] OR "COVID-19" [Supplementary Concept] OR COVID-19 [tw] OR coronavirus [tw] OR nCoV[TIAB] OR HCoV[TIAB] OR ((virus*[Title] OR coronavirus[Title] OR nCoV[Title] OR infectious[Title] OR HCoV[Title] OR novel[Title])AND (Wuhan[Title] OR China[Title] OR Chinese[Title] OR 2019[Title] OR 19[Title] OR COVID*[Title] OR SARS-Cov-2[Title] OR NCP*[Title]) OR “Coronavirus”[MeSH]))))

A two-stage screening process was undertaken to identify studies meeting the eligibility criteria. First, two authors (either CO or EE) assessed citations from the searches and identified potentially relevant titles and abstracts. Second, either DG, AJ or RW assessed the full texts of potentially eligible studies to identify studies to be included in the review. This process was managed via a custom-built online platform (Shiny web app, supported by a MongoDB database). The platform allowed for data extraction via a built-in form.

Data collection and assessment of risk of bias

One author (DG, AJ or RW) extracted data from each included study using a piloted data extraction form, and the extracted data were checked by one other author (DG, KH, EA, RC, AJ, or EE where AJ extracted data, AJ where DG extracted data). Disagreements were resolved through discussion, and where this failed, by referral to a third reviewer (KH, NK or PM). Irrespective of study design, data source and outcome measure examined, the following basic information were extracted: citation; study aims and objectives; country/setting; characteristics of participants; methods; outcome measures (related to self-harm / suicidal behaviour and COVID-19); key findings; strengths and limitations; reviewer’s notes. For articles where causal inferences are made - i.e. randomised or non-randomised studies examining the effects of interventions or aetiological epidemiological studies of the effects of specific exposures – we plan to use a suitable version of the ROBINS-I or a preliminary similar tool for exposure studies to assess risk of bias as appropriate based on the research question and study design ( Morgan et al., 2017; Sterne et al., 2016).

Data synthesis

We synthesised studies according to themes based on research questions and study design, using tables and narrative. Results were synthesised separately for studies in the general population, in health and social care staff and other at-risk occupations, and in vulnerable populations (e.g. people of older age or those with underlying conditions that predispose them to becoming severely ill or dying after contracting COVID-19) where relevant. Where multiple studies addressed the same research questions, we assessed whether meta-analysis was appropriate and would conduct it where suitable, following standard guidance available in the Cochrane Handbook ( Deeks et al., 2019). The current document is the second iteration of our review. We have not considered it appropriate to combine any results identified so far in a meta-analysis due to quality and heterogeneity.

Results

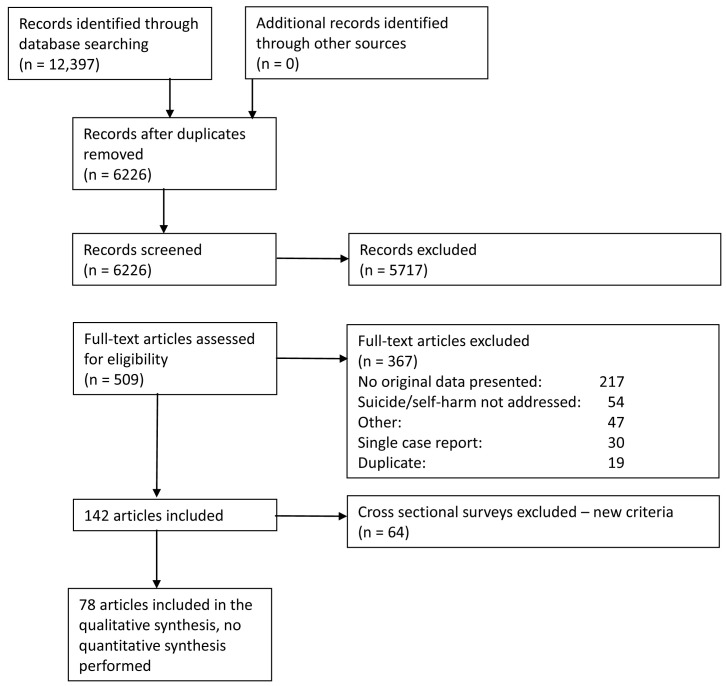

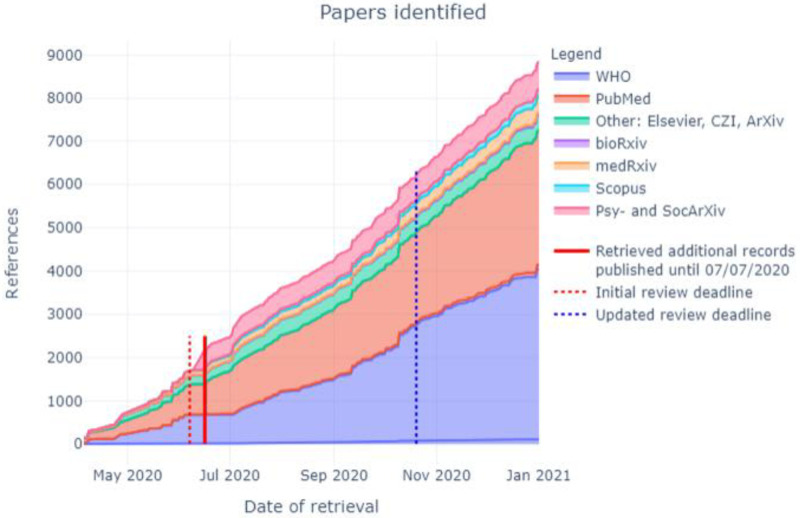

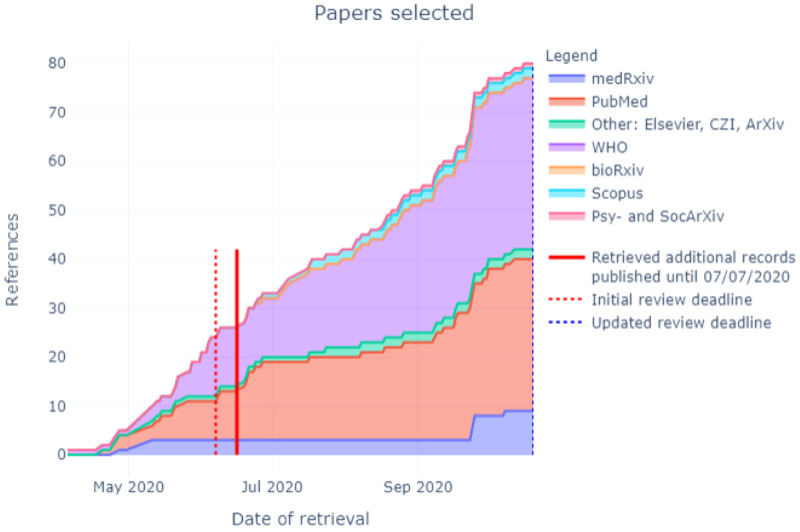

In total, 12,397 citations were identified by 19 th October 2020 from all electronic searches, after duplicates were removed ( Figure 2). The cumulative numbers of articles over time that were identified by the search and included in the review are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. The majority of studies identified in the review (5105; 82%) were sourced from two databases, PubMed and WHO; a further 10% (n=622) were drawn from pre-print sites such as MedRxiv.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 3. Number of articles identified by database and repository over time.

Figure 4. Number of articles selected by database and repository over time.

Description of included studies

We included 78 articles in the review. We have highlighted in Table 1– Table 6 where new citations have updated existing studies. Sixty-four cross sectional surveys are included in Appendix 1. In total, six studies spanned several countries or were worldwide, including one using a Reddit mental health dataset (almost half of users are from the USA); 13 were from the United States; seven from China; nine from India; five from the United Kingdom; four each from Japan and Nepal; and between one and three each from Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iran, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Pakistan, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Qatar and Switzerland. All articles were based on observational studies: twenty-five were case series with a sample of two or more (although Jefson et al., 2020 and Rohde et al., 2020 were based on the same case series); thirteen were cross sectional surveys; two were based on social media posts; six were modelling studies; twenty were service utilisation studies; and nine assessed suicide rates. Studies are summarised by these study types in Table 1 through Table 6. Three other relevant articles were identified, two of these described mixed methods studies ( Evans et al., 2020; Son et al., 2020) and one a case-control study ( Cai et al., 2020). Almost half (n=34) of the articles did not appear to have been peer- reviewed of which ten were pre-prints and 21 were published as research letters to the Editor.

Table 1. Summary of included case series.

| Authors | Geography | Data used | Outcome | Conclusions | Comment/ Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al., 2020 | India | Suicide cases linked with alcohol

withdrawal syndrome (AWS) reported in newspapers or news channels’ websites from 25 March (start of national lockdown) to 5 May 2020. All cases were in the states of the southern part of India: Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Karnataka. ( n=23) |

Suicide death | AWS seems implicated in a number of

suicides in southern India but, on the basis of the empirical information that is presented here, we do not know whether these deaths were caused by the COVID-19 lockdown, and whether these deaths occurred at a higher frequency during the observation period than they normally occur. |

We cannot be sure whether any of the

suicides occurred primarily as a direct consequence of AWS, or were brought about due to the unavailability of alcohol during lockdown. Study uses news reports as their data source. Letter to the editor, so unlikely to be peer reviewed. |

| Bhuiyan et al., 2020 | Bangladesh | News reports of COVID-19 related

suicide deaths (n=8) |

Suicide death | Job loss, debt and difficulties obtaining

food because of financial difficulties reported in all cases |

Small sample size (n=8)

Study uses news reports as their data source. Letter to editor, probably not peer reviewed. |

| Boshra & Islam, 2020a | Bangladesh | Suicide cases relating to COVID-19 taken

from Bangladeshi online media INITIAL REPORT: 1 March to 31 July 2020 (n=32) UPDATED REPORT published October 27th (Boshra & Islam 2020b): 1 March to 30 Sept 2020 ( n=37). 65% of the cases were male. |

Suicide death | 45.9% were due to economic reasons

attributed to lockdown-related unemployment. |

Although they examined only cases

relating to COVID-19, the authors recognize they do not know how many cases would have occurred if the pandemic had not happened. Study uses news reports as their data source. Pre-print, not peer reviewed. |

| Buschmann & Tsokos, 2020a | Germany | Case series of 10 individuals identified at

autopsy who died by suicide during the pandemic up to March 25 th 2020 UPDATED REPORT ( Buschmann & Tsokas, 2020b) Individuals identified at autopsy who died by suicide associated with the effects of the pandemic up to 29 May 2020 ( n=11) |

Suicide death | All had pre-existing mental health issues.

No evidence of COVID-19. Authors conclude that the effects of the lockdown and media reporting influenced the suicide. |

It is unclear what circumstances of the

deceased persons were brought about directly due to the COVID-19 crisis. Both are Letters to editor, probably not peer reviewed. |

| Dsouza et al., 2020 | India | News reports (n=69) of COVID-19 related

suicide deaths including n=72 cases from March to 24 May 2020. Age range 19–65 years; 63 (88%) males. |

Suicide death | The most common reported factors

were: 1) Fear of infection (n=21); 2) Financial crisis (n=19); 3) COVID-19 related stress (n=9); 4) Positive test for COVID-19 (n=7); 5) Isolation related issues (n=5) 6)Social boycott (n=4); and 7) Migrant unable to return home (n=3). |

Study uses news reports as their data

source. Overlaps with other publications based on news reports from same country e.g. Rajkumar, 2020; Shiob et al., 2020. Letter to editor, probably not peer reviewed. |

| Griffiths & Mamun, 2020 | Global

-Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, USA |

News reports of couples (

n=6) engaging

in COVID-19-related suicidal behaviour includes one murder suicide identified via Searches of seven English- Indian online papers from March to 24 May. |

Suicide attempt

and/or death (couples) |

Details several potential reasons:

1) Fear of infection; 2) Money problems (due to recession associated with lockdowns); 3) Harassment or victimisation by others due to (possibly perceived) infection status; 4) Stress of being in isolation or quarantine; and 5) Uncertainty of when the pandemic will end. |

Small sample size (n=6)

Study uses news reports as their data source. Letter to editor, probably not peer reviewed. |

| Iqbal et al., 2020 | Qatar | Referrals of patients with a positive

COVID-19 test to consultant liaison psychiatry service from a ward or A&E in three hospitals in Doha, . Median age 39.5; 48 male ( n=50) |

Suicide

attempts/self- harm |

Three of the 50 referrals had self

harmed. The self-harm was apparently a reaction to the pandemic. Two were asymptomatic for COVID-19, and one had a mild case. |

Focus is on psychiatric presentations in

people with acute infections, the long term impact of COVID-19 infection on psychiatric morbidity requires further study. Peer reviewed. |

|

Jefsen

et al., 2020a

Rohde et al., 2020 |

Denmark | Review of notes of adult patients from

the psychiatric services of the Central Denmark Region (catchment area: 1.3 million people). Notes between 1 Feb and 23 March 2020 reviewed to identify those describing "pandemic-related psychiatric symptoms" (including "self harm / suicidality", n=74). Median age 29.8 years; 77% female Note full case series n=1357 relevant records found from 412,804, reported in Rohde et al.,, 2020. |

Suicide

attempts/self- harm, suicidal thoughts |

Of the 74 patients identified, 14 (19%)

had self-harm thoughts; 10 (14%) had self-harmed; 34 (46%) had suicidal thoughts; 10 (14%) had made suicide attempts and 13 (18%) had a passive wish to die from COVID-19. |

Findings restricted to suicidal / self-harm

related outcomes in 74 patients with these outcomes. No data on the overall percentage of adult psychiatry patients with these outcomes during or pre-pandemic. Peer-reviewed letter to the editor. |

| Jefsen et al., 2020b | Denmark | All clinical notes from patients below

18 years old in the Central Danish psychiatric service between 1 Feb and 23 March 2020. Pandemic‐related psychopathology identified in 94 children and adolescents. |

Suicide

attempts/self- harm |

8 notes from 5 of the 94 patients

specifically described self‐harm or suicidality related to the pandemic |

No baseline data for individuals.

No data on the overall percentage of child psychiatry patients with these outcomes during or pre-pandemic. Editorial perspective; probably not peer reviewed. |

| Jolly et al., 2020 | USA | Child and adolescent psychiatry

inpatients, age range 11–17 years; 3 female, 1 male; ( n=4). |

Suicide

attempts/self- harm, Suicidal thoughts |

One suicide attempt; one suicidal plan

and two with suicidal thoughts Stressors described included: 1. Unable to see friends/ partner (all cases) 2. Arguments with parents 3. Misunderstanding within friendship group that could not be resolved well over social media 4. Academic worries- performance declined since move to distance learning 5. Feeling isolated |

Detailed descriptive study of very small

sample. Peer reviewed journal. |

| Kapilan, 2020 | India | News reports about two nurses drawn

from news reports ( n=2) |

Suicide death,

Suicide attempts/self- harm |

1 suicide: a nurse who treated COVID-19

patients, and died reportedly due to “ extreme stress and mental disturbance” 1 suicide attempt: a nurse who contracted COVID-19 |

Small sample size (n=2)

Information drawn from news reports. Similar to Rahman et al., 2020. Letter to the editor; possibly not peer reviewed. |

| Kar et al., 2020 | India | News reports of deaths by suicide

among film stars in India, 28 May to 30 July 2020 ( n=7). |

Suicide death | 7 Indian film stars who died by suicide.

Media reports claimed three of these were related to financial problems associated with COVID-19. |

It is unclear whether any of the deaths

were strongly linked with COVID-19 and its indirect impact on people's lives, or whether the individuals were already experiencing mental health difficulties. Study uses news reports as their data source. Appears to use the same data as Mamun et al., 2020b. Letter to the editor; probably not peer reviewed. |

| Mamun et al., 2020a | Bangladesh | News report of suicide pact in mother

and 22 year old son, 11 Jun 2020 ( n=2) |

Suicide death | University student aged 22 and his

mother aged 47 died by suicide. The father had insisted the day before that the student complete online exams as an internet connection was arranged. |

Study uses news reports as their data

source. Only a single pact reported Suggests that online teaching in LMIC may create real tensions due to digital poverty Letter to the editor; possibly not peer reviewed. |

| Mamun et al., 2020b | India | News reports of deaths by suicide

among film stars in India ( n=7 in 2020 vs. n=16 in 2002–2019) |

Suicide death | The frequency of celebrity suicides

in India appears to have increased markedly during the COVID-19 era. The authors highlight the dangers of sensationalised media reporting of celebrity suicides triggering immitative events in the general population. |

Study uses news reports as their data

source. Appears to use the same data as Kar et al., 2020 Letter to the editor; possibly not peer reviewed. |

| Mamun & Ullah, 2020 | Pakistan | News reports of COVID-19 related

suicide deaths in Pakistan, Jan 2020 to end April 2020 ( n=12, a further 4 reports of suspected suicide were not presented). |

Suicide death | Economic concerns reported in 8/12

cases, and fear of infection in the remaining 4. There were 13 other reports of suicides (and attempted suicide) during this period not reported to be linked to COVID-19. |

Highlights the potential importance of

the economic impact of COVID-19 and/or public health measures on influencing suicide in low- and middle-income countries. Study uses news reports as their data source. Peer reviewed journal; paper accepted on same day as received. |

| Nalleballe et al., 2020 | World | Adult COVID-19 patients (inpatients and

outpatients) with records held on the TriNetX database ( trinetx.com), 20 Jan to 10 June 2020 (n= 40,469, 76% living in USA |

Suicidal

thoughts |

9,086 (22.5%) had a neuropsychiatric

coded diagnosis within 1 month of COVID-19 diagnosis. 62 (0.2%) had suicidal thoughts recorded. |

Large clinical database of people with

clinical diagnosis of COVID-19. It is possible that suicidal thoughts were not asked about systematically by clinicians and so there is likely to be marked under-recording. Peer reviewed journal. |

| Pirnia et al., 2020 | Iran | Suicide of members of one family ( n=2). | Suicide death | Son died by suicide three weeks after his

father died of COVID-19. Two days after the son, the mother also killed herself. |

Small sample size (n=-2).

Letter to the editor; probably not peer reviewed. |

| Rahman et al., 2020 | Worldwide | News reports of nurse suicide deaths

( n=6, 2 from Italy, 1 each from UK, Mexico, USA and India) |

Suicide death | Factors reported as associated with

deaths included: fear they had become infected; positive test result; being in quarantine; fearful of becoming infected. |

Study uses news reports as their data

source. Small sample size (n=6). Similar to Kapilan, 2020. Peer reviewed letter to the editor. |

| Rajkumar, 2020 | India | 49 English-language news reports of

COVID-19 related suicides in India, 12 March to 11 April 2020 ( n=23 deaths) |

Suicide death | 6 of the deaths occurred amongst

patients hospitalised / in isolation In 7 cases a diagnosis was mentioned - in 4 this was depression, in 3 alcohol dependence. Precipitating / contributing factors included fear of acquiring infection (9/23); developing influenza-like symptoms (7/23); bereavement (n=5) |

Study uses news reports In English as

their data source. Provides interesting observations, useful for hypothesis testing. Probable overlap with others e.g. Dsouza et al., 2020; Shiob et al., 2020 Letter to the editor, possibly not peer reviewed. |

| Sahoo et al., 2020 | India | Clinical case reports of COVID-19 related

suicide attempts presenting to the ED ( n=2) |

Suicide attempts | Both cases were related to the fear

and stigma of COVID-19. One case was ordered to self-isolate due to being in contact with a known case. |

Small sample size (n=2)

Letter to editor; probably not peer reviewed. |

| Shoib et al., 2020 | India | News reports in 22 English and local

newspapers published in India, identified from Google and reporting on suicides in relation to COVID-19 Search period 25 Jan to 18 April 2020 ( n=34 suicides) |

Suicide death | 18 (52.9%) aged 18–35 years; 28 (82.4%)

male Most frequent reasons given: Fear of infection: 16 (47.1%); misinterpreted fever as COVID-19: 9 (26.5%); Depression and loneliness: 7 (20.6%); personal stigma of COVID-19: 4 (11.8%) Authors mapped number of reports vs number of suicides over the 8 week study period. Rise in COVID-19 related suicides mirrored the rise in number of cases - in first 3 weeks there was 1 report per week, whereas in the last 3 weeks there were 23 reports |

Large case series of news reports,

but probably overlaps with others e.g. Dsouza et al., 2020; Rajkumar, 2020. Study uses news reports as their data source. Letter to the editor, possibly not peer reviewed. |

| Syed et al., 2020 | India | Reports of alcohol-related suicides from

India, extracted from recent media reports, using Google News, retrieving reports of suicide cases from Indian online English language newspapers between 25 March and 17 May 2020 (during India’s national lockdown). Age range 25–70 years; all males ( n=27) |

Suicide death,

Suicide attempts |

27 cases suicide or suicide attempts.

Alcohol restrictions were reported as leading to an increase in attempts and deaths, because of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. |

Case reports from newspapers in English

in Indian news. Underreporting possible because of stigma. Similar to Shiob et al., 2020. Letter to the editor; possibly not peer reviewed. |

| Thakur & Jain, 2020 | World | News reports of COVID-19 related

suicide deaths ( n=7) |

Suicide death | Identified 4 types of suicide risks:

1) Social isolation; 2) Economic; 3) Stress in health professionals; 4) Stigma |

Small sample size (n=7)

Study uses news reports as their data source. Peer reviewed journal; paper accepted 1 day after received. |

| Valdés-Florido et al., 2020 | Spain | Patients admitted to two hospitals in

Spain with reactive psychoses in the context of the COVID-19 crisis during the first two weeks of lockdown ( n=4) |

Suicide attempts | Stress from the pandemic thought to

have triggered reactive psychoses in four patients two of whom presented with severe suicidal behaviour |

Small sample size (n=4)

Peer reviewed journal. |

Table 2. Summary of cross sectional surveys and cohort studies.

| Authors | Geography | Data used | Outcome | Conclusions | Comment/ Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debowska et al., 2020 | Poland | University students recruited via 10 Polish

universities and the Students’ Parliament of the Republic of Poland. N = 7228, 81% female; Mean age = 22.78. Data collection occurred in five waves, during the first two months of the COVID- 19 pandemic in Europe (March – April 2020). The waves differed from one another in the amount and type of lockdown-type measures, with wave 4 being characterised by the strictest restrictions |

Suicidal thoughts | No statistical evidence of differences

in suicidal thoughts over the 5 stages of data collection or of gender differences in prevalence. |

Representativeness of sample unclear

Frequency and intensity of suicidal thoughts and impulses in the past 24 h were measured using the Depressive Symptom Inventory-Suicidality Subscale ( Joiner et al., 2002) Letter to editor, probably not peer reviewed |

| Hamm et al., 2020 | USA | Subset of adults aged >60 years who

were participating in an RCT of treatment resistant depression and agreed to a qualitative interview. N=73 (of total 743 RCT participants) |

Suicide and self-harm

thoughts |

5(7%) had suicidal thoghts at the time

of the interview (April 1–23 2020), but not pre-pandemic; 7 (10%) had had a reduction in pre-existing suicidal thoughts. The rest had no suicidal thoughts pre or post pandemic |

Used PHQ-9 pre and post pandemic

(validated measure) Those agreeing to interview self- selecting, perhaps less likely to have experienced untoward effects. Small sample Peer reviewed |

| Hamza et al., 2021 | Canada | Students at a single university in Canada

Surveyed using the same survey tool in May 2019 and May 2020. n=773 (74% female; mean age 18.5 years) ( 964 responders to 2019 survey) |

Suicide attempts/

self-harm |

No statistical evidence evidence of rise

in NSSI: score at T1 (May 2019) 0.18 (SD 0.38) and T 2 (May 2020) 0.20 (SD 0.40) Likewise no difference when analysis stratified according to presence of absence of pre-existing mental health concerns |

Used adapted version of the Inventory

of Statements about Self-Injury (ISAS; Klonsky & Glenn, 2009) to assess non-suicidal self-harm in relation to 7 behaviours e.g. cutting / biting. Reported average score on ISAS scale rather than prevalence of each / any behaviour Peer reviewed |

| Iob et al., 2020 | UK | General population sample recruited on-

line via media / social media. Survey data from 21 March – 20 April 2020. Participants included individuals who provided data on abuse, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm on at least one occasion n = 44 775 Weighted to represent UK population (age, sex, ethnicity, education) |

Suicide attempts/

selfharm, suicide and self-harm thoughts Help seeking |

7984 (18%) reported suicidal / self-

harm thoughts; 2174 (5%) had self harmed at least once. Suicide/self-harm thoughts higher in those with a COVID-19 diagnosis vs. without (33% vs 17%); likewise for suicide attempts (14% vs. 5%). 57% of those engaging in SH and 40% with thoughts had sought some professional support. Compared with previous UK survey data, levels of help-seeking from MH professionals (14.5% for thoughts / 4.7% SH/SA) were lower. (14.5% for thoughts / 4.7% SH/SA) were lower. |

Suicidal / self-harm thoughts

measured via PHQ-9. Self harm via asking participants whether they’d self-harmed or deliberately hurt themselves. Index period was the last week. Large sample but convenience sampling Use of sample weighting to take account of selection bias Report on outcomes in relation to COVID-19 diagnosis but may be confounded by sociodemographic differences between groups Peer reviewed |

| Raifman et al., 2020 | USA | Two nationally representative surveys

of US adults: 1) The 2017–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)- 5085 (86.8%) of 5856 NHANES participants responded to suicidal ideation questions and were included in the analyses; 2) 2020 COVID-19 and Life Stressors Impact on Mental Health and Wellbeing study (CLIMB) - conducted 31st March to 13th April 2020. 1415 (96.3%) of 1470 CLIMB participants responded to all questions relevant to the analysis |

Suicidal thoughts | Suicidal ideation increased more than

fourfold, from 3.4% in the 2017–2018 NHANES to 16.3% in the 2020 CLIMB survey, and from 5.8% to 26.4% among participants in low-income households. Suicidal ideation was more prevalent among people facing difficulty paying rent (31.5%), job loss (24.1%), and loneliness (25.1%). |

Survey methods for NHANES and

CLIMB were not identical, but two large population-based surveys conducted at two points. Characteristics of participants in CLIMB and NHANES differed. Respondents may have differed from those who did not, particularly if the stressors examined affected survey participation. Pre-print, not peer reviewed |

| Sueki & Ueda, 2020 | Japan | Two wave population survey of Japanese

people aged >20. Recruited via Internet Survey company to reflect census population of Japan. 6683 completed both waves of the survey (out of 125,011 people selected (5%) and 67% of the 9982 who completed the wave 1 survey) 51% male; mean age 46.5 years. Surveyed Jan 24 2020 (when there were just 2 covid-19 cases in Japan) and again 27–30 April, 3 weeks after state of emergency declared. |

Suicidal thoughts | Suicidal thoughts score was lower

during the pandemic (mean = 1.59) than before it (mean = 1.71),t(6682) = 5.87, p < .001. People in their 30s, and people: a) with unstable employment status (part-time, temporary worker), b) without children, c) with relatively low annual household income and d) those currently receiving psychiatric care had higher suicidal thoughts scores at T2 vs. the reference group, after controlling for suicidal ideation at T1 |

Short-form suicide ideation scale"

( Sueki, 2019). 6 questions, overall scores ranges from 0–12. Low response rate from selected sample (5%) And at T2 vs T1 (67%). Pre-print, not peer reviewed |

| Wang et al., 2020a | China | COVID 19 patients and controls January 2,

2020 to March 10, 2020. 376 COVID-19 patients (including 95 male and 281 female patients) hospitalized between January 2 and March10, 2020,with 501 controls without COVID 19 (including 110 men and 391 women) recruited from different social media platforms |

Suicidal thoughts | In Covid-19 patients moderate or high

suicide risk in 27 % COVID-19 patients vs. 8 % in control (sig difference). High or very high suicide risk similarly higher in Covid group 10% vs. 4%. Age, anxiety, depression and poor sleep quality were all risk factors for high suicide risk in COVID-19 patients. |

Online or face to face interview

assessment by psychiatrists using the Nurses’ Global Asesment of Suicide Risk scale(NGASR). Convenience sampled controls Unlikely to be peer reviewed |

| Wang et al., 2020b | China | Repeat cross sectional study. Participants

who completed survey via “Wenjuanxing,” a Chinese online platform providing functions equivalent to Qualtrics. The data were from two studies, one conducted during the outbreak stage from (N=2540, mean age = 25.28 ± 8.07) and one conducted during the after peak stage (N=2543, mean age = 22.03 ± 6.30) |

Symptom networks

illustrating the relationship between depression and anxiety symptoms were estimated Suicidal thoughts showed a decreased connection with “inability to relax” and “guilty” symptoms, whereas suicidal thoughts showed an increased connection with the “too much worry” symptom over time |

The association between symptoms

changed over the course of the pandemic in China Some changes in connections between some symptoms of suicidal thoughts and other symptoms of depression/anxiety If generalizable, could point to some treatment targets that are more central to suicide risk |

Limitation: anxiety and depression

assessed via self-report not diagnoses Used PHQ-9 Not certain how generalizable networks are to other phases of the pandemic or to other countries Peer reviewed |

| Winkler et al., 2020 | Czech

Republic |

Covid-19 survey 6th to 20th May 2020.:

N=3021 respondents interviewed either by computer-assisted telephone interview or computer assisted web interviewing. General population aged 18–64 years. The survey was representative in relation to national population (age, sex, education and region) Comparable baseline data were obtained from the 2017 Czech Mental Health Survey. |

Suicide risk | Marked increase in respondents with

moderate/high suicide risk from 3.9% (95% CI 3.2, 4.5) in 2017 to 12.3 (11.1, 13.4) in 2020. Having been tested for Covid-19 (with a positive or negative result) was linked with elevated perceived suicide risk (OR 2.1; 1.1, 3.8) as was Covid-19 health worries (OR 1.4; 1.1, 2.1) and Covid-19 economic worries (OR 1.4; 1.2, 1.7). |

Mini International Neuropsychiatric

Interview (MINI) Large nationally representative survey with comparable baseline data but Covid-19 survey was conducted remotely whereas the baseline survey was face-to-face interviewing, so information bias cannot be ruled out. Computer- assisted telephone interviewing had a low participation rate. Peer reviewed |

| Wu et al., 2020a | China | Survivors of COVID-19, followed up

median 22 days (IQR 20–30d) post hospital discharge. N=370 |

Suicide and Self-harm

thoughts |

4 (1.1%) reported experiencing

suicidal / self-harm thoughts over several days |

Large survey of hospital admitted

COVID-19 No pre-illness baseline measure. Used PHQ-9 (standardised measure). Letter to editor, probably not peer reviewed. |

| Wu el al., 2020b | China | 4124 pregnant women during their third

trimester from 25 public hospitals in 10 provinces Jan 1 st-Feb 9 th 2020 1285 assessed after January 20, 2020 when the coronavirus epidemic was publicly announced and 2839 were assessed before this time point. |

Self-harm thoughts | A multi-centre study to

identify mental health concerns in pregnancy The risk of self- harm thoughts was higher after 20 th January compared to before (aRR=2.85, 95% CI: 1.70, 8.85, P=0.005). |

Pre-existing data collection system.

Thoughts of self-harm in the last 7 days from the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS, Cox et al.,., 1987) The findings indicate a need for enhanced levels of psychological support for pregnant women during a major infectious disease epidemic / pandemic. Pregnant women in Wuhan, Hubei Province (the epicentre of the epidemic) were not included in the sample. Peer reviewed |

| Zhao et al., 2020 | China | Survey of COVID-19 patients (n=106), 46

male, range 35–92 years at Tongji Hospital, Wuhan from Carried out February 2nd- 16 th, 2020 |

Suicide and Self-harm

thoughts |

24.5% (26/106) of COVID-19 patients

had self-harming or suicidal thoughts, which were "significantly higher percentages than those of the general population." |

Highlights the potential mental health

support needs, and the risk faced by recovering COVID-19 patients. Used PHQ-9. Peer reviewed |

| Zhang et al., 2020 | China | Repeated survey in cohort of primary and

secondary school children / adolescents from two counties before the outbreak started (wave 1, early November 2019) and 2 weeks after school reopening (wave 2, mid-May 2020) in an area of China with low risk of COVID-19. 1389 children recruited 1271 completed info for W1. 1241 W2, response rate 93.1%. Mean [SD] age, 12.6 [1.4] years; age range, 9.3–15.9 years; 736 [59.3%] male). |

NSSI

Suicidal thoughts Suicide plans |

NSSI (42.0% in 2020 vs 31.8% in

2019; aOR, 1.35 [95% CI, 1.17-1.55]; P < .001), suicide ideation (29.7% vs 22.5%; aOR, 1.32 [95% CI, 1.08-1.62]; P = .008), suicide plan (14.6% vs 8.7%; aOR, 1.71 [95% CI, 1.31-2.24]; P < .001), and suicide attempt (6.4% vs 3.0%; aOR, 1.74 [95% CI, 1.14-2.67]; P < .001). OR adjusted for sex, body mass index, self-perceived household economic status, family cohesion, parental conflict, academic stress, parental educational level, family adverse life events, self-perceived health, sleep duration, and sleep disorders |

For NSSI, asking ‘In the past 12 months,

have you ever harmed yourself in a way that was deliberate, but not intended to take your life?’. Suicidal ideation, plans and attempts- from the 2013 Youth Risk Behaviour Surveillance System in the USA Pre-covid data Total number of children in years 4–8 not given so not sure of % recruited and therefore representativeness Seasonal variations and secular trends not accounted for. Peer reviewed |

Table 3. Summary of social media platform posts studies.

| Authors | Geography | Data used | Outcome | Conclusions | Comment/ Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low et al., 2020 | Demographic information

is unknown but Reddit users are predominantly American (49.9%) |

Reddit Mental Health Dataset

including posts from 826,961 unique users from 2018 to 2020. |

Using unsupervised clustering,

they found the suicidality and loneliness clusters more than doubled in the number of posts during the pandemic. The Reddit support groups for borderline personality disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder became significantly associated with the suicidality cluster The suicidality cluster doubled in size and a new cluster surrounding self-harm emerged. |

Using natural language

processing (NLP) on text from some of the world’s largest mental health support groups it is possible to identify mental health problems as they emerge in real time and to identify vulnerable sub-groups |

Such approaches could help

subreddit moderators track who is in need of assistance as well as well the concerns of specific communities are No formal diagnoses are made, reliant on what authors post Selection bias related to who posts as well as when they post and how they cope under different circumstances Peer reviewed |

| Saha et al., 2020 | USA | ∼60M Twitter streaming

posts originating from the U.S. from 24 March-24 May 2020, and compare these with ∼40M posts from the comparable period in 2019 |

A 20% increase in frequency of

posts that made reference to suicidal ideation was observed during 2020. |

Suicide risk is multifaceted.

More attention directed at population-scale mental healthcare, such as universal screening approaches |

Analysis of Twitter content makes

good use of readily available data and may reveal patterns and trends that are not easily discernible by conducting research using more traditional methods but what state in their posts does not necessarily reflect trends in suicidality in the population. Not peer reviewed. Pre-print. |

Table 4. Summary of studies using modelling approaches to estimate the possible impact of the pandemic on suicide rates.

| Authors | Country

/ region |

Data used to inform estimate | Model prediction | Comment / Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhatia, 2020a | USA | Previous research modelling the association of

unemployment with suicide in the USA indicating a 1% rise in unemployment was associated with a 1% rise in suicide. Assumes unemployment in the USA has risen from 3.8% to over 20% |

7444 additional suicides in the following 2

months There were approximately 48,000 suicides in USA in 2018, so this equates to a predicted 15% rise in suicides in the USA. |

No account for potential impacts of pandemic other

than via unemployment rises Duration of unemployment rises uncertain Pre-print, not peer reviewed. |

| Bhatia, 2020b | USA | Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies investigating

the association of duration of unemployment with risk of suicide: used estimate of 2.5 fold increase in risk during 1–5 years of unemployment, derived from one Swedish and one Finnish cohort. National bureau of Health statistics: age adjusted suicide rates US Dept of Labour: weekly unemployment claims US Bureau of Labour Statistics: are distribution of workforce |

Estimated 9,786 additional suicides per year

There were approximately 48,000 suicides in USA in 2018, so this equates to a predicted 20% rise in suicides in the USA |

Estimate of the association between unemployment

and suicide derived from person-based studies investigating long-term unemployment and risk of suicide; this may over-estimate association in the context of economic recession Unclear whether age specific suicide risks were applied to the unemployment data – these were not reported in meta-analysis and text of paper contradictory No account for potential impacts of pandemic other than via unemployment rises Pre-print, not peer reviewed. |

| Kawohl & Nordt, 2020 | World | Previous research modelling the association of

unemployment with suicide in 63 countries (2000– 2011). International Labour Organisations (ILO) Predicted job losses (March 2020) of between 5.3 to 24.7 million |

Between 2135 and 9570 extra suicides per

year worldwide. i.e. a 0.3% to 1.2% rise |

No account for potential impacts of pandemic other

than via unemployment rises Duration of unemployment rises uncertain Research letter, probably not peer reviewed. |

| McIntyre & Lee, 2020a | USA | The authors analysed theassociation of

unemployment with suicide in the USA (1999–2018) and reported a 1% rise in unemployment was associated with a 1% rise in suicide. Three scenarios for changes in level of unemployment a) unchanged at 3.6%(2020), 3.7% (2021); b) rise to 5.8% (2020) and 9.3% (2021); c) rise to 24% (2020) and 18% (2021). |

Scenario b) associated with a 3.3% rise in

suicide in 2020–21 Scenario c) associated with an 8.4% rise in suicide in 2020–21. |

Usefully models the potential impact of two different

unemployment rate rises. No account for potential impacts of pandemic other than via unemployment rises Duration of unemployment rises uncertain Peer reviewed |

| McIntyre & Lee, 2020b | Canada | The authors analysed the association of

unemployment with suicide in Canada (2000–2018) and reported a 1% rise in unemployment was associated with a 1% rise in suicide. Three scenarios for changes in level of unemployment a) minimal change at 5.9%(2020), 6.0% (2021); b) rise to 8.3% (2020) and 8.1% (2021); c) rise to 16.6% (2020) and 14.9% (2021). |

Scenario b) associated with a 5.5% rise in

suicide in 2020–21 Scenario c) associated with a 27.7% rise in suicide in 2020–21. |

Usefully models the potential impact of two different

unemployment rate rises. No account for potential impacts of pandemic other than via unemployment rises Duration of unemployment rises uncertain Peer reviewed |

| Moser et al., 2020 | Switzerland | Used published data on increased risk of

suicide amongst a) prisoners in shared cells (3 fold increased risk) and b) prisoners in solitary confinement (27 fold increased risk) as indicators of risk of lock down on a) multi-person households and; b) single person households. Data on the annual number of suicides in Switzerland and the proportion of Swiss people living alone (16%) and in shared households (84%). |

Estimate 1523 additional suicides.

Based on an estimate the 1043 recorded suicides in Switzerland in 2017 this equates to a more than doubling in suicides deaths |

The team modelled the impact of COVID-19

pandemic on multiple outcomes as well as suicide. Prison confinement is probably not a good proxy for effects of lockdown. High suicide rates in prisoners are due to multiple factors e.g. age and gender profile; high levels of psychiatric morbidity rather than impacts of confinement. Other potential factors e.g. rises in unemployment not included in models Pre-print, not peer reviewed. |

Table 5. Summary of studies assessing service utilisation.

| Authors | Country /

region |

Data used | Outcome | Findings | Comment / Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capuzzi et al., 2020 | Italy | Emergency psychiatric evaluations at

psychiatric emergency rooms in two centres in Lombardy, serving a population of approx. 850,000 in two equivalent periods pre (Fri 22 Feb 2019-Sun 5 May 2019) and following the first COVID-19 case in Italy up to end of first phase of lock-down (Fri 21 Feb 2020 to Sun 3rd May 2020). Data obtained from hospital registers. |

Suicide

attempts/self- harm |

Period A (2019) 388 total attendances,

including 68 (17.5%) for self-harm/suicide attempt Period B (2020) 225 total attendances, including 59 (26.2%) for self-harm/suicide attempt. Whilst absolute number of SH/SA cases lower, the difference in number as a proportion of total cases was somewhat higher in age/sex adjusted models (aOR 1.48 (0.97 to 2.28) |

Hospital based study from two

centres Peer reviewed |

| Chen et al., 2020 | England, UK | Data obtained from Trust hospitals clinical

record systems. People using or referred to inpatient and community MH services (including psychological therapy services) in Cambridge and Peterborough - population approx 860,000. Data for Liaison psychiatry referrals for SH/Suicide attempt/ cover 11 March 2014 - 30 August 2020. Data also presented for suicidal thoughts, but data were combined with “low mood” |

Intentional drug

overdose and self-harm |

A marked reduction (p<0.001) in liaison

psychiatry referrals for intentional drug overdose, self-harm and suicidal thoughts occurred after 23 March (lockdown). The proportion of referrals returned to pre-lockdown levels by May/June 2020. |

Liaison team referral only (not all ED

attendances) at a single hospital. Liaison psychiatry referral pathways may have changed as a result of COVID-19 No detailed demographic analysis of referrals as the paper focused on a wide range of mental and physical health presentations. Single area in England. Peer reviewed |

| Dragovic et al., 2020 | Australia | Western Australia (WA) North Metropolitan

Health Services EDs were extracted from the Emergency Department Data Collection database. These 3 EDs serve a population of approx. 800,000 persons. Attendances over the period January to May 2020 were compared to those that occurred over the same calendar month periods during 2019. |

Suicide

attempts/self- harm |

7140 attendances (5522 persons) over the

two study periods. Suicidal and self-harm presentation decreased by 26% to previous year |

Attendances at three hospitals but

WA has low population density and went into stringent lockdown early - hence findings may not be generalisable to other Australian states or other countries; routinely collected healthcare data are large and complete, but they lack rich contextual detail. Peer reviewed |

| Gonçalves-Pinho et al., 2021 | Portugal l | People attending a Psychiatric Emergency

Department in a tertiary hospital in North Portugal serving a population of approximately 3 million people. Attendance between March 19th and May 2nd 2020 (when "emergency state" / restriction of movement existed in Portugal in response to COVID-19) compared with same dates in 2019 |

“Suicide

and self- inflicted injury presentations” to psychiatric ED |

Between March 19

th and May 2

nd 2020,

a significant reduction was identified in presentations of “suicide and intentional self-inflicted injury” to a metropolitan psychiatric ED, compared to the same period in 2019: N=36 v 81, a 55.6% reduction. |

Based on attendances at a single

hospital. Unclear if codes include people with suicidal thoughts as well as acts. Peer reviewed |

| Hernández-Calle et al., 2020 | Spain | Electronic health records examined at a major

general hospital in Madrid, Spain: November 2018 to April 2020. |

Suicidal

thoughts |

During March-April 2020, significantly

fewer psychiatric emergency department visits due to suicidal ideation were reported compared to the same period in 2019. |

Data only shown in a graph.

Single centre study - findings may have limited generalisability. Peer reviewed |

| Hewson et al., 2020 | UK | 31 prisons in UK

Internal reports from Safer Custody Units in 31 prisons where healthcare is provided by CareUK (Russell Green, personal communication) |

Suicide

attempts/self- harm |

After lockdown there were fewer

implementations of Assessment, Care in Custody and Teamwork (ACCT) processes; to initiate care- plans for prisoners considered at risk of self-harm or suicide. Across the 31 prisons, there were 1079 ACCTs implemented in February 2020 compared to 828 in April 2020, a fall of just under 25%. Analysis of data for 8 prisons indicated that there were falls in incidents of self-harm, decreasing by a third from 324 in February 2020 to 214 in April 2020. |

No gender breakdown (female

prisoners in the UK generally have much higher rates of self-harm than male prisoners) Unclear the basis of the selection of the 8 prisons with self-harm data Peer reviewed editorial |

| Jacob et al., 2020 | Australia | Single trauma centre in Australia, serving a

population of 1.5 million. Compared mean number of trauma admissions during March and April during years 2016 to 2020 |

Self-harm | During March and April 2020 a significant

decrease in total number of trauma- related admissions was observed, but no significant difference in admissions following self-harm was seen. |

Mean no. of admissions examined

before and during the Covid-19 public health emergency. Findings from a single centre may not be generalisable. The study was evidently under-powered for examination of mean monthly self- harm admissions. Peer reviewed |

| Karakasi et al., 2020a | Greece | Records of psychiatric emergency cases

presenting at the psychiatric emergency department of AHEPA University General Hospital of Thessaloniki during the following equal time intervals: 1 March to 15-May 2019, 15November 2019 to 31 January 2020, 1 March to 15 May 2020. |

Suicide

attempts/self- harm |

During the restrictive measures in Greece

(March – May 2020), the number of hospital presenting emergency psychiatric incidents fell by half (p < 0.01). The number of suicide attempts was higher in March- May 2020 (n=7) compared to the same period in 2019 (n= 5) and Nov 2019-Jan 2020 (n=4) |

Data from a single hospital

Small numbers Letter. Uncertain if peer-reviewed |

| Lersch, 2020 | USA | Emergency calls (911) to Detroit Police

Department for services between 26th Feb (first reported case COVID in city) and 27th April 2020. Comparison with 2017–2019 and also number of COVID-19 cases in the city. |

Suicide threats

and suicides in progress |

In the time period of interest during the

pandemic in 2020, the number of 911 calls for mental health issues was the lowest of the 4 years (2017–2020), declining by 16% from 2019 to 2020. However, the number of calls for suicide threats declined in 2020, while the number of calls for suicides in progress remained relatively stable over the 4-year period. No significant correlations between daily number of COVID-19 cases in the city and the number of calls from mentally ill persons, but as the number of COVID-19 cases increased there was a decline in calls for suicides in progress, but a significant inverse correlation between numbers of COVID-19 cases and threats of suicide calls (Pearson’s r=0.394) and a similar but non-significant relationship with calls for suicides in progress. In local area analysis, “some of the ‘hotspots’ for suicide threats were in areas of higher rates of COVID-19 cases”. |

Interesting analysis by numbers

of COVID-19 cases, including by locality. Single city. Data are early and may not be complete for COVID-19 cases. Unclear if peer-reviewed |

| McAndrew et al., 2020 | Ireland | Electronic health records for the emergency

department (ED) of a large teaching hospital in Dublin were examined during the first 8 weeks of the Covid-19 emergency (from 16th March to 10th May 2020). Comparative data for 2018 and 2019 were also examined. |

Suicide

attempts/self- harm, Suicidal thoughts |

A 21% reduction in the frequency of

psychiatric emergency presentations was observed, although the proportion of presentations with suicidal ideation or self-harm as factors remained unchanged. The observed reduction was largely due to a reduce attendance frequency during 'normal' hours. |

Electronic health record studies are

not prone to selection or self-report information biases. Further research examining patterns of emergency psychiatry presentations during COVID-19 could identify risky / vulnerable groups of people who have not been seeking help during a crisis. Similar studies from other countries and with extended follow-up periods are needed to build up a comprehensive picture of these temporal patterns. Peer reviewed |

| McIntyre et al., 2020 | Ireland | Self-harm referrals to Liaison Psychiatry team

in a single tertiary care hospital in Gallway Ireland. Contrast 1 March 2020–31 May 2020 with the same period in 2017–2019 |

Self-harm

presentations to a general hospital. |

Between March-April 2020, a significantly

lower proportion of self-harm presentations (-35%) to the hospital was reported, compared to the same period for 2017–2019. At the end of May, similar proportions of self-harm presentations were reported compared to previous years. |

Single hospital study. Incidence

based on referrals to liaison psychiatry - may under-estimate total hospital presenting cases. Liaison psychiatry referral pathways may have changed as a result of COVID-19. Peer reviewed |

| Olding et al., 2021 | England, UK | Trauma patients with penetrating injuries

who were treated at King's College Hospital in London, 23rd March to 29th April 2020 compared to the same period in 2018 and 2019. |

Self-harm (self-

inflicted injuries |

Whilst the incidence of all types of

penetrating trauma appeared to have fallen by 35% during the early lockdown period), the number of self-harm episodes increased from n=1 in 2018 to 5 in 2019 and 8 in 2020 |

Small, single site study. Crude

analytical approach. Number of self- harm cases too small to draw any strong conclusions Peer reviewed |

| Pignon et al., 2020a | France | Emergency psychiatric consultations from

three psychiatric emergency centres from first four weeks of lockdown (started March 17th 2020) and corresponding weeks 2019 |

Suicide

attempts |

During the four first weeks of lockdown,

553 emergency psychiatric consultations were carried out, less than half (45.2%) of the corresponding weeks in 2019 (1224 consultations). Total suicide attempts decreased in 2020 to 42.6% of those in 2019. |

Peer reviewed publication now

published, Pignon et al., 2020b |

| Rajput et al., 2020 | England, UK | Trauma admissions to a single level 1 trauma

centre in Liverpool using data from a trauma research network database. Compared three 7-week periods: (1) Lockdown: 23 March 2020–10 May 2020) (2) Pre-lockdown: 7 weeks prior to lockdown (27 January 2020–15 March 2020) (3) Pre-lockdown 2019: 7 week equivalent period in 2019 (25 March 2019–12 May 2019) |

Suicide

attempts/self- harm |

Total trauma centre attendances fell

during lockdown: 2019: n=194; 7 weeks pre lockdown 2020 n=173; during lockdown n=121 Equivalent numbers for self-harm were: 20 (2019); 24 (pre-lockdown 2020); 14 (lockdown 2020): i.e. 30% fall vs 2019. |

Small sample size; no assessment of

any change in socio-demographic characteristics of self-harm; possible changes due to service re-configurations in response to COVID. Peer reviewed |

| Rhodes et al., 2020 | USA | Trauma registry data of attendees at a Level 1

trauma centre in S Carolina, USA Jan 1-May 1 2019 compared to Jan 1 - May 1 2020 (lockdown April 8 th – May 1 st 2020). |

Suicide

attempts and self-harm, including specific methods |

Some evidence of rise in suicide attempts:

2019: 6 (0.6% of all presentations); 2020: 11 (1.4%) (p=0.079), including ‘self- harm by jumping’: 2019: 0 (0%); 2020: 5 (0.6%); p=0.011). No change in other ‘self-harm’ presentations: gun: 2019: 4 (0.4%); 2020: 4 (0.5%) (p=0.716); knife: 2019: 2 (0.2%); 2020: 1 (0.1%) (p=0.719), nor in acts of ‘Undetermined intent’: 2019: 18 (1.8%); 2020: 6 (0.8%) (p=0.064). |

Most of the period studied (15 of

the 18 weeks) in 2020 preceded lockdown. Small numbers and no specific data on suicide attempts during the post-lockdown period. The statistical comparison of suicide/SH episodes compared these episodes as a % of total attendances, rather than changes in absolute numbers. Peer reviewed |

| Sade et al., 2020 | Israel | Pregnant women admitted to high risk

pregnancy units between 19 March 2020 and 26 May 2020 (the strict isolation period of the pandemic) (n=90) compared to those hospitalised to these units between November 2016 and April 2017 (n=279) |

Suicidal

thoughts assessed using the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) |

Prevalence of suicidal thoughts was similar

pre (5.0%) vs during (8.6%) pandemic (p = 0.221). OR in multivariable logistic regression model, controlling for maternal age, adjusted OR 1.8, 95% CI 0.71–4.85, p = 0.203. |

Admission criteria may have

changed post pandemic (although admissions per month similar ~ 45/month Relatively small sample Select sample - pregnant women - generalisability to wider population uncertain. Pre-pandemic data collected in Nov 2016-April 2017 - 3 years previously - no account of any secular trends (also seasonal difference in collection period). Peer reviewed |

| Sheridan et al., 2021 | USA | Emergency department visits for mental

health issues to a single tertiary care pediatric hospital in Portland, Oregon April 1 2019 up to 29 April 2020 |

Suicidal patients | Department dealt with 14108 patients in

2019. 16 suicidal patients seen in April 2020 vs. 46 in April 2020 (a 65% fall) |

Before / after lock down

comparison, time trend analysis Used routinely available data Data on suicidal patients only specified for 1 month. One tertiary centre so not generalisable. Peer-reviewed |

| Smalley et al., 2021 | USA | Attendees with suicidal thoughts and alcohol

issues across 20 diverse EDs in a large Midwest integrated healthcare system with >750,000 ED visits annually. All behavioural health (BH) visits were collected for 1-month (March 25 th to April 24, 2020) following “stay at home” orders (lockdown). ICD-10 codes were used to identify visits associated with suicidal thoughts. The same parameters were used to collect data for the same time period for 2019. |

Suicidal

thoughts ICD coded by hospital staff |

Comparing 2020 with the same period in

2019, there was 44.4% decrease in overall ED visits and 28.0% decrease in BH visits. Attendances of individuals with suicidal thoughts decreased by 60.6% in 2020 (n=451) vs. 2019 (n=1144). As a percentage of all ED attendances, suicidal thoughts attendances decreased from 2.03% in 2019 to 1.44% in 2020. |

Alternative avenues for help-

seeking not included. But highlights importance of improving access for vulnerable populations during a pandemic. Included only one month in 2019 and one in 2020. Letter to editor, probably not peer reviewed |

| Titov et al., 2020 | Australa | Callers / website visits to "Mindspot" - national

digital MH service in Australia. Compared caller volume and characteristics 1- 28 Sept 2019 (n=1650) vs. 19 March - 15 April 2020 (n=1668) |

Suicidal

thoughts question from PHQ-9 |

No change in prevalence of: a) suicidal

thoughts (30.6% in September 2019 vs. 27.5% in March-April 2020; p=0.08), or b) suicidal intentions or plans (3.7% v 2.9% post p=0.27) |

Clinical / helpline sample - not

population based. Possible seasonal differences- September contacts vs. March-April Evidence of increased contact volume to a digital service. Peer reviewed |

| Walker et al., 2020 | USA | ED attendances (adult and pediatric) from

an integrated multiple hospital / ED system. n=18 EDs across several states. Diagnoses via electronic health records. Pandemic period (17 March 2020 to 21 April 2020) compared to same period in 2019 (17 March 2019 to 21 April 2019) and 36 day pre- pandemic period in 2020 (9 Feb 2020 to 16 March 2020) |

Suicide

attempts/self- harm |

Total ED attendances fell by around 50% during the period

of "the broad institution of distancing measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic". Likewise, total ED attendances with "suicide" diagnosis fell by around one third during pandemic period: 17 March 2020 to 21 April 2020: n=36 (0.2% of total attendances) vs. 17 March 2019 to 21 April 2019: n=59 (0.2% total attendances) 9 Feb 2020 to 16 March vs. 2020: n=64 (0.2% total) |

Hospital presentations only

Only includes first 36 days of distancing measures. Peer reviewed |

Table 6. Summary of studies assessing suicide rates.

| Authors | Geography | Data used | Conclusions | Comments/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acharya et al., 2020 | Nepal | News reports of police data on suicides

in Nepal 2019–2020 |

April 2020-mid July 2020: 1233 suicide deaths

Feb-March 2020: 414 suicide deaths. Report 414 suicides /month pre-lockdown vs. 559/month after lockdown (a 35% rise) |

Paper uses newspaper reporting of police suicide

statistics as primary source of data, so may not be reliable. Letter to editor, probably not peer reviewed |

| Calderon-Anyosa & Kaufman, 2020 | Peru | Suicide deaths reported by the Peruvian

National Death Information System between 1st January 2017 and 28th June 2020. |

Interrupted Time Series (ITS) analysis.

Suicide deaths fell sharply in males and females from the start of the lockdown period (March 16 2020) |

Authors used appropriate time series methods

Only 80% of all deaths are registered by the Peruvian National Death Information System. It is unclear whether cause of death assignment is time-lagged in Peru. Pre-print. Not peer reviewed |

| Isumi et al., 2020 | Japan | Suicide statistics published by the

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare for children (aged <20 years) Jan 2018-May 2020 |

Investigated the impact of school closures (March–

May 2020) by comparing these months with the same period in 2018 and 2019 using Poisson regression. In 2018 and 2019, suicide rates tend to increase from March to May; however, suicide rates from March to May in 2020 appeared to decrease slightly. Compared to March to May 2018 and 2019, no strong evidence of an increase in suicide rates during these months in 2020 (the school closure period): Incidence rate ratio =1.15, (95% CI 0.81 to 1.64). |

Analysis did not account for possible underlying

temporal trends in suicide using time-series approaches. Publicly available national statistics. Possibly too short a timespan to assess impact on child suicides. Suicides among children and adolescents reportedly peak at the beginning of school semesters in Japan, suicide rates may have increased when school restarted in June 2020. Peer reviewed |

| Pokhrel et al., 2021 | Nepal | News reports of police data on suicides

in Nepal 2019–2020 |

Report a 25% rise in suicide deaths in the lockdown

period (after mid-March 2020) compared to pre- lockdown. 1647 suicides between mid-March 2020 and 27 June 2020. |

Data derived from newspaper reporting of police

suicide statistics as primary source of data, so may not be reliable. Letter, may not have been peer reviewed. |

| Poudel et al., 2020; | Nepal | News reports of police data on suicides

in Nepal 2019–2020 |

Report a 20% rise in suicide deaths In the first month

of lockdown (from 24 March) (487 suicides vs. 410 in mid-February to mid-March 2020). Since the start of lockdown up to 6 June, there were 1,227 suicides (16.5/day) compared to 5,785 (15.8/day) in the same period in 2019 |

Data derived from newspaper reporting of police