Abstract

Objective:

The present study was designed to ascertain the associations between acculturation and well-being in first-generation and second-generation immigrant college students. Acculturation was operationalized as a multidimensional construct comprised of heritage and American cultural practices, values (individualism and collectivism), and identifications, and well-being was operationalized in terms of subjective, psychological, and eudaimonic components.

Method:

Participants were 2,774 first-generation and second-generation immigrant students (70% women), from 6 ethnic groups and from 30 colleges and universities around the United States. Participants completed measures of heritage and American cultural practices, values, and identifications, as well as of subjective, psychological, and eudaimonic well-being.

Results:

Findings indicated that individualistic values were positively related to psychological and eudaimonic well-being, and positively, although somewhat less strongly, linked with subjective well-being. American and heritage identifications were both modestly related to psychological and eudaimonic well-being. These findings were consistent across gender, immigrant generation (first versus second), and ethnicity.

Conclusions:

Psychological and eudaimonic well-being appear to be inherently individualistic conceptions of happiness, and endorsement of individualistic values appears linked with these forms of well-being. Attachments to a cultural group—the United States, one’s country of origin, or both—appear to promote psychological and eudaimonic well-being as well. The present findings suggest that similar strategies can be used to promote well-being for both male and female students, for students from various ethnic backgrounds, and for both first-generation and second-generation immigrant students.

Keywords: acculturation, well-being, immigrants, college students, individualism, collectivism

The United States has been undergoing an unprecedented wave of immigration for nearly half a century. Since 1965, when restrictive immigration quotas were lifted, more than 25 million immigrants have entered the United States on a documented basis (Jaeger, 2008). The proportion of immigrants in the United States increased by 24% between 2000 and 2009, and foreign-born individuals now account for 13% of the overall U.S. population (Grieco & Trevelyan, 2010). Post-1965 immigrants to the United States have come from all over the world and, in contrast to earlier waves of immigration, have been primarily non-European and non-White (Hernandez, Denton, & Macartney, 2007). Regardless of where they come from, most immigrants undergo a process of adaptation—known as acculturation—following their arrival in the United States. Given the size of the U.S. immigrant population, the health and well-being of immigrants is of considerable importance to practitioners and policy makers. It is essential to understand how acculturation impacts well-being in immigrant individuals.

The number of individuals undergoing acculturation is larger than might be suggested by the size of the foreign-born population. Official immigration statistics do not include individuals who were born in the United States but raised by foreign-born parents. Some writers have suggested that the term “immigrants” should include not only those people who were born outside the United States (first-generation immigrants), but also the U.S.-born children of foreign-born parents (second-generation immigrants; Portes & Rumbaut, 2001). Although they are not foreign-born themselves, second-generation immigrants often grow up in family contexts where the heritage culture is present in the home (e.g., foods, customs, artifacts; Portes & Rumbaut, 2006). Additionally, many second-generation immigrants are connected to their countries of familial origin through vacations, stories, and frequent communication with relatives abroad (e.g., Kasinitz, Mollenkopf, Waters, & Holdaway, 2008). As is the case with first-generation immigrants, second-generation immigrants must balance their cultural heritage with “mainstream” American culture (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). For these and other reasons, first-generation and second-generation immigrants are often considered together in studies of acculturation and its effects on adjustment. It is essential, however, to conduct analyses that consider each immigrant generation separately so that differences in patterns of findings between foreign-born and U.S.-born individuals can be identified (Zane & Mak, 2003).

Immigrant College Students: A New and Growing Population

College students are an important segment of the young adult population; whereas college attendance was once reserved for the wealthy and for those entering upper-echelon professional careers, a considerable proportion of young adults in the United States today spend at least some time in college. The number and proportion of American young adults who attend postsecondary education has increased markedly in the last several decades. In 1959, approximately 2.4 million American students attended university full time; by 2010, that number had jumped to 12.7 million (National Center on Education Statistics, 2010). This 430% increase is more than six times the 72% increase in the total U.S. population during that same time span (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). The well-being and mental health of college students is therefore an important concern for counselors and policy makers.

The mass immigration that has been ongoing in the United States for nearly 50 years has begun to change the college student population (Schwartz, Weisskirch, et al., 2011). In three samples gathered by Schwartz, Weisskirch, et al. (2011) at 30 colleges and universities around the United States, 26% (3,251 out of 12,346) of the students surveyed (with international students excluded from consideration) reported that both of their parents were born outside the United States. To the extent to which this estimate is representative, students from immigrant families are clearly an important segment of the college population and warrant empirical attention. However, although some studies have focused on immigrant students from a single ethnic group (e.g., Lee, Yoon, & Liu-Tom, 2006; Schwartz & Zamboanga, 2008), studies looking at ethnically diverse samples of immigrant students have been rare, and few studies have examined the link between acculturation and well-being in immigrant students. The significant growth in the college student population, coupled with the mass immigration occurring in the United States, renders the well-being and mental health of immigrant college students as an important concern for counselors and policy makers.

The present study was designed to address this knowledge gap. Given that one’s cultural orientation can play a significant role in one’s well-being (e.g., Syed & Azmitia, 2009; Umaña-Taylor, Bhanot, & Shin, 2006), the primary goal of the current study was to examine the associations between (a) various indices of acculturation and (b) multiple indicators of well-being in college students from immigrant families. Many studies on immigrants focus on acculturative stress, discrimination, and other problems (e.g., Finch & Vega, 2003; Todorova, Falcón, Lincoln, & Price, 2010), and, as a result, there is a relative dearth of research on strengths and resilience in immigrants. In the present study, we adopt a positive psychology perspective, where we view immigrant students in terms of strengths to be promoted rather than in terms of problems to be managed or prevented (cf. Seligman, 2005). Indeed, the decision to immigrate to another country is often a courageous one, and immigration and acculturation may be associated with well-being and flourishing, as well as with distress and poor health.

Conceptualizations of Acculturation

The term “acculturation” traditionally referred to a process of assimilation, where immigrants would acquire the practices of their new receiving culture and would simultaneously discard the practices of their cultural heritage (Gordon, 1964). This “straight-line assimilation” model was developed to explain the integration of Eastern and Southern European immigrants into U.S. society in the early 20th century. Over successive generations, these immigrants were able to blend into the White American mainstream. However, the 1965 Immigration Act shifted the flow of immigration away from Europe, such that the majority of immigrants now come from the Caribbean, Central and South America, and Eastern and Southern Asia. Given the persistence of racial prejudice and discrimination toward these populations, straight-line assimilation has generally not been possible for members of these groups. Thus, Caribbean, Latin American, and Asian immigrants have adopted other acculturation strategies, including remaining attached to their heritage cultures as they became American. Assimilating into mainstream American culture is no longer the primary or only acculturation option (Alba & Nee, 2006).

Accordingly, in the late 20th century, scholars (e.g., Berry, 1980; Szapocznik, Scopetta, Kurtines, & Aranalde, 1978) began to recognize acculturation as a bidimensional phenomenon. The extent to which one acquired American cultural practices was no longer necessarily associated with the extent to which one retained or relinquished the practices from one’s country of familial origin. Indeed, many first-generation and second-generation immigrants could be characterized as bicultural, that is, both acquiring American cultural practices and retaining those from one’s heritage culture. Empirically, a great deal of post-1965 acculturation research has identified biculturalism as the most adaptive, and most commonly endorsed, approach to acculturation (e.g., Coatsworth, Maldonado-Molina, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2005; Chia & Costigan, 2006; Schwartz & Zamboanga, 2008). The term “acculturation” is used here in accordance with this contemporary bidimensional perspective (e.g., Sam & Berry, 2010) that takes into account a person’s orientation towards the receiving culture and towards her or his heritage culture1.

However, even following the recognition that acculturation was bidimensional, the domains in which it was studied remained limited (Lee et al., 2006; Schwartz, Unger, et al., 2010). Most acculturation measures developed in the 1980s and 1990s focused primarily on cultural behaviors or practices such as language use, culinary preferences, and choice of friends and media (e.g., Suinn, Ahuna, & Khoo, 1992; Szapocznik, Kurtines, & Fernandez, 1980). Some more recent measures and conceptualizations of acculturation have included multiple domains of acculturation, including cultural practices as well as identifications with the United States and with one’s culture of origin (e.g., Nguyen & von Eye, 2002; Zea, Azner-Self, Birman, & Buki, 2003). Cultural identifications connect directly to the extensive literature on ethnic identity—the extent to which first-generation and second-generation immigrants feel connected to their cultural heritage (see Phinney & Ong, 2007; Smith & Silva, 2011, for recent reviews). Cultural identifications also refer to national identity—solidarity with the receiving country or region—which has received far less attention than ethnic identity. The umbrella of cultural identifications therefore subsumes both ethnic identity and national identity, and represents a domain of acculturation.

Other measures have focused on cultural values (e.g., Lugo Steidel & Contreras, 2003; Park & Kim, 2008), although in many cases these values have not been explicitly labeled as components of acculturation. Though the values covered have varied across measures, they have generally fallen under the broader umbrella of collectivism (subjugation of individual wishes and desires to the needs of the family or other social group) and individualism (focus on one’s individual identity, desires, and priorities). Individualism and collectivism each take both horizontal (vis-à-vis friends and coworkers) and vertical (vis-à-vis parents, teachers, employers, and other authority figures) forms. There is an extensive literature on individualism and collectivism as broad cultural value systems (e.g., Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002; Triandis, 1995), and linking more specific values to individualism and collectivism may help to connect the larger literature on cultural values with the literature on acculturation (Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones, 2006; Schwartz, Weisskirch, et al., 2010).

Indeed, the chasm between primarily collectivist-oriented immigrants and the largely individualist societies that are receiving them has been cast as the “backdrop” for the process of acculturation, and for the need to balance one’s heritage and receiving cultural streams (Schwartz et al, 2006; van de Vijver & Phalet, 2004). Although individualism and collectivism are not opposites and may be compatible with one another (Oyserman et al., 2002), when developing a value system, the strengths and problems associated with each play a role in determining the outcome. This is similar to the task of balancing one’s heritage-cultural practices or identifications with those of the society of settlement. Given that the United States is regarded as a highly individualist country, both in Hofstede’s (2001) cross-cultural analysis and in popular media (Hirschman, 2003), individualism may represent a core American value. As evidenced by recent immigration patterns and countries of origin, in most cases, immigrants’ heritage cultures may be more collectivist in comparison. Individualism and collectivism were therefore used to represent cultural values in the present study.

Cultural practices, values, and identifications are therefore all essential to consider as domains of acculturation (e.g., Abraido-Lanza, Armbrister, Florez, & Aguirre, 2006; Costigan, 2010; Schwartz, Unger, et al., 2010). Moreover, heritage and receiving cultural dimensions are likely to operate within each domain, suggesting that the construct of acculturation consists of six separate processes (heritage and receiving cultural practices and identifications, as well as collectivist and individualist values). Our multidimensional model of acculturation helps to address criticisms (e.g., Hunt, Schneider, & Comer, 2004; Lopez-Class, Castro, & Ramirez, 2011; Rudmin, 2003) that the contemporary operationalization of acculturation—and especially the ways in which acculturation is measured—is not faithful to the foundational definition of the construct. Specifically, our use of multiple domains, and our treatment of heritage and American cultural orientations as independent dimensions, helps to move the theory and measurement of acculturation away from simplistic proxies such as nativity and primary language spoken at home. Moreover, the primary (or sole) reliance on cultural practices as indices of acculturation does not reflect the complexity of acculturation; for example, immigrants to the United States may learn English out of necessity, but they may not endorse individualistic values or identify as American. For another example, although many Asian immigrant adolescents and young adults lose proficiency in (or otherwise do not use) their native languages, they nonetheless maintain their collectivist heritage and identify strongly with their countries of origin (Portes & Rumbaut, 2006).

Acculturation and Well-Being

As noted above, acculturation, cast as a process of balancing one’s heritage culture with the culture of the receiving country or region, has often been framed as a stressful process (e.g., Akhtar, 1999). That is, acculturation is sometimes assumed to be a difficult process that is associated with psychopathology, risk taking, and family conflicts (e.g., Afable-Munsuz & Brindis, 2006; Ramirez et al., 2004; Smokowski, Rose, & Baccallao, 2008). These kinds of acculturative stressors may be experienced by first and second generation immigrants, as well as later generations (Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Jarvis, 2007), and they can involve difficulties adapting to the receiving culture and/or perceived rejection from the heritage-cultural community for having relinquished one’s cultural heritage (Castillo, Cano, Chen, Blucker, & Olds, 2008). Indeed, some studies have carefully investigated the extent of stress experienced by immigrants, and specific variables that predict this stress (Lueck & Wilson, 2011), and other studies have examined acculturative stress as a mediator of the effects of acculturation on mental health outcomes (Schwartz et al., 2007; Wang, Schwartz, & Zamboanga, 2010). These acculturative processes, and their associations with adjustment difficulties, have been studied in college students as well as in other types of immigrants.

However, as noted earlier, the strengths and positive attributes of immigrants have been less widely studied. There is evidence, for example, that biculturalism—the ability to master and work within two cultural streams—is associated with a number of psychological benefits, including advanced perspective taking (Tadmor, Tetlock, & Peng, 2009). One potential strength that has sometimes been examined vis-à-vis acculturation in immigrants is well-being (e.g., Yoon, Lee, & Goh, 2008). The study of well-being is a central theme in positive psychology (Ryan & Deci, 2001; Ryff & Singer, 2008; Waterman, 2008). Broadly stated, well-being refers to feelings of happiness and satisfaction with one’s life, the ability to meet the demands involved in one’s daily activities, and possessing a sense of personal purpose and meaning. At least three types of well-being have been delineated—subjective well-being, psychological well-being, and eudaimonic well-being. Subjective well-being refers to a general sense of contentment with how one’s life has proceeded thus far, and to a predominance of positive versus negative emotions (Diener, 2006). Psychological well-being refers to a nomological net of constructs referring to flourishing—feeling competent, that one is able to meet the demands offered by one’s social environment (e.g., school or work), self-determined decision making, satisfying interpersonal relationships, purpose in life, and self-acceptance (Ryff, 1989; Ryff & Singer, 2008). Eudaimonic well-being refers to self-realization, choosing to engage in challenging activities and continuously seeking opportunities for personal growth (Waterman, 2004, 2011). These three forms of well-being have been shown to correlate highly with one another (Waterman et al., 2010) and cluster onto a higher order latent construct (Schwartz, Waterman, et al., 2011).

Despite their considerable intercorrelations, subjective, psychological, and eudaimonic well-being represent somewhat distinct components of positive functioning (Waterman, 2008). Subjective well-being likely characterizes the greatest number of individuals, given that it can be equated with happiness regardless of the source of that happiness. One can be “happy” for any number of reasons unrelated to being able to meet the tasks of daily life or to self-realization (cf. Waterman, Schwartz, & Conti, 2008). Similarly, psychological well-being is likely more inclusive than eudaimonic well-being: One can feel competent, connected to others, and accepting of oneself without having discovered and actualized one’s “true self’ (Waterman et al., 2010). Likewise, even individuals high on psychological well-being may suffer setbacks or losses and report low subjective well-being (e.g., Durkin & Joseph, 2009), and engaging in challenging activities and attempting to “find oneself” may induce frustration at times (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). All three types of well-being, then, are likely necessary for understanding a person’s overall degree of positive functioning and adaptation.

The associations between acculturation and well-being have been infrequently studied, and most studies that have examined these linkages have done so using single dimensions of acculturation and of well-being (e.g., Yoon et al., 2008). Ethnic identity is perhaps the most commonly studied dimension of acculturation vis-à-vis well-being (see Smith & Silva, 2011, for a recent meta-analytic review). The association between ethnic identity and well-being has varied depending on how well-being was operationalized. A significant but modest association between ethnic identity and self-esteem has consistently emerged in studies of adolescents and college students (e.g., Phinney, Cantu, & Kurtz, 1997; Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Jarvis, 2007; Umaña-Taylor, 2004). Ethnic identity has been found to be more strongly related to psychological well-being (e.g., Chae & Foley, 2010) and general indices of positive affect (e.g., Kenyon & Carter, 2011). However, to our knowledge, no published study has examined the associations of multiple dimensions of acculturation with multiple forms of well-being in an ethnically diverse sample. Given that acculturation and well-being are both multidimensional constructs, operationalizing each of these constructs using their component dimensions is likely to provide the most complete understanding of how acculturation and well-being may relate to one another.

The three forms of well-being are essential to understand and study in college students for a number of reasons. First, subjective well-being includes the presence of positive emotional states such as happiness and life satisfaction and the absence of negative emotional states such as anxiety and depression (Diener, 2006), that is, the absence of symptoms that would lead students to seek counseling or that could compromise their social or academic functioning. Second, psychological well-being reflects a self-directed ability to handle the tasks of life—something that is essential in making one’s way through the socially and academically challenging (and sometimes unstructured) college environment (Montgomery & Côté, 2003). Third, eudaimonic well-being represents an important component of intrinsic motivation (Waterman et al., 2003,2008), and seeking to discover or actualize one’s life purpose serves as a strong reason for engaging in challenging activities. In turn, seeking out challenges and seeking self-realization are essential for succeeding in the modern world of work, where individuals must be able to adapt quickly and agentically to sudden changes such as outsourcing, mergers, and downsizing (Kalleberg, 2009; Smith, 2010). Students high in the three forms of well-being under study here are therefore likely to be more successful in negotiating the college environment and in using this environment to prepare for entry into the workforce, compared to students who struggle with well-being.

The Present Study

The present study was designed to ascertain the association between acculturation and well-being, both operationalized multidimensionally, in a sample of college students from immigrant families and from six ethnic groups. We used a sample from various regions of the United States, given the regional differences in acculturative patterns that have been found in prior studies (Lee et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor & Shin, 2007). In light of evidence that the acculturation experience, and its links to other life domains, varies across gender (Gorman, Read, & Trevelyan, 2010) and ethnicity (Sue & Chu, 2003), we sought to examine the consistency of the associations that we found across gender and across ethnic group. We also examined the consistency of our results across immigrant generations, to ascertain the extent to which first-generation and second-generation immigrant students would differ in terms of the relations between acculturative process and dimensions of well-being. Additionally, we examined the consistency of our results between (a) traditional “college town” colleges/universities and (b) urban/suburban or commuter settings, given that universities located in college towns—where the majority of students reside on campus, in fraternity/sorority housing, or in off-campus apartments—are likely more characteristic of American “college culture” than are universities located in cities or suburbs—where a larger percentage of students reside at home with family members.

The present study was guided by four research questions. First, to what extent are heritage and American acculturation-related variables associated with well-being? Second, are the associations between acculturation and well-being consistent across the domains of acculturation—practices, values, and identifications? Third, are these associations consistent across gender, ethnicity, and immigrant generation? Finally, are the present findings equivalent between college towns and urban/suburban or commuter settings?

Sufficient literature is available to advance a hypothesis only for the first research question. Given the positive associations of ethnic identity with self-esteem (Syed & Azmitia, 2009; Umaña-Taylor & Shin, 2007) and with psychological well-being (Kenyon & Carter, 2011), we hypothesized that heritage practices, values, and identifications would all be positively associated with all three forms of well-being and with a composite well-being variable. Because the literature on associations between American orientation and well-being has been inconclusive, we did not advance a specific hypothesis in terms of how American practices, values, and orientations would relate to well-being.

Method

Participants

The present sample comprised 2,754 students (30% men, 70% women) from 30 colleges and universities around the United States. The mean participant age was 20.16 years (standard deviation [SD)] 3.24 years; 97% between 18 and 29 years of age). Given our focus on acculturation among students from immigrant families, we included only those participants who indicated that both of their parents were born outside the United States. Forty percent of the sample characterized themselves as first-generation immigrants, and 60% characterized themselves as second-generation immigrants. In terms of ethnicity, 9% of the sample identified as White, 11% as Black, 32% as Hispanic, 33% as East/Southeast Asian, 11% as South Asian, and 4% as Middle Eastern. Nineteen participants (less than 1% of the sample) did not indicate their ethnicity. A number of demographic variables differed across ethnic groups, including age, gender, immigrant generation, primary countries of origin, and socioeconomic status (see Table 1). Two of the study sites were Hispanic-serving institutions, and one of the sites was a minority-serving institution (with a primarily Asian American student population). There were no historically Black colleges and universities among our study sites.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Ethnic Group

| Characteristic | Ethnic group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | Hispanic | East/Southeast Asian | South Asian | Middle Eastern | |

| N (% of sample) | 253 (9.3%) | 300(11.0%) | 884 (32.3%) | 908 (33.2%) | 293 (10.7%) | 97 (3.5%) |

| Mean age | 20.72 | 20.65 | 20.31 | 19.80 | 19.85 | 20.16 |

| % Female | 68.3% | 75.0% | 76.3% | 63.1% | 70.9% | 63.9% |

| % First generation | 66.4% | 38.3% | 36.6% | 37.3% | 42.3% | 33.0% |

| Primary countries of origin | UK, Poland, USSR, Yugoslavia | Haiti, Jamaica, African countries | Mexico, Cuba, Colombia, Peru | China, Vietnam, Philippines, Korea | India, Pakistan, Bangladesh | Lebanon, Iran, Afghanistan |

| Annual household income | ||||||

| Less than $30,000 | 23.2% | 39.6% | 33.8% | 31.0% | 26.1% | 19.1% |

| $30,000 to $50,000 | 19.5% | 28.3% | 31.1% | 23.0% | 26.4% | 25.5% |

| $50,000 to $100,000 | 32.1% | 21.5% | 22.2% | 30.0% | 27.5% | 28.7% |

| More than $100,000 | 25.2% | 10.6% | 12.9% | 16.0% | 20.1% | 26.6% |

Procedures

The study measures, along with others not analyzed for the present report, were presented as part of the multi-site university study of identity and culture (MUSIC). A full description of the procedures used in the MUSIC study is provided in Castillo and Schwartz (this issue). Only measures related to acculturation and well-being are described here.

Measures2

Cultural practices.

The Stephenson (2000) Multigroup Acculturation Scale was used to assess heritage and U.S. cultural practices. This measure consists of two subscales: heritage-culture practices (17 items, α = .90 in the current sample), which includes use of one’s heritage language and association with heritage-culture friends and romantic partners, and U.S.-culture practices (15 items, α = .85), which includes use of English and association with U.S. friends and romantic partners. Sample items include “I listen to music of my ethnic group” (heritage-culture practices) and “I speak English at home” (U.S.-culture practices). Stephenson (2000) found that the factor structure of scores generated by the instrument supported the separation of heritage and U.S. cultural subscales.

Cultural values.

Because individualism and collectivism are both subdivided into horizontal and vertical variants, three sets of cultural values were used in the present analyses: (a) horizontal individualism-collectivism, (b) vertical individualism-collectivism, and (c) self-construal. Horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism were assessed using corresponding 4-item scales developed by Triandis and Gelfand (1998). Internal consistency coefficients for the present sample were as follows: horizontal individualism, α = .79; vertical individualism, α = .78; horizontal collectivism, α = .77; and vertical collectivism, α = .76. Sample items include “I rely on myself most of the time; I rarely rely on others” (horizontal individualism), “Competition is the law of nature” (vertical individualism), “I feel good when I collaborate with others” (horizontal collectivism), and “It is my duty to take care of my family, even when I have to sacrifice what I want” (vertical collectivism). Triandis and Gelfand report results of analyses demonstrating the factorial and construct validity of these subscales.

Self-construal was measured using the 24-item Self-Construal Scale (Singelis, 1994). Twelve items measure independence (α = .77) and 12-measure interdependence (α = .79). Sample items include “I prefer to be direct and forthright in dealing with people I have just met” (independence) and “My happiness depends on the happiness of those around me” (interdependence). An indepth psychometric analysis of the Self-Construal Scale (see Guo, Schwartz, & McCabe, 2008) supported the factor structure proposed by Singelis (1994).

As we have done in prior work (e.g., Schwartz, Weisskirch, et al., 2011), we collapsed the three indicators of individualistic values (horizontal individualism, vertical individualism, and independence) and the three indicators of collectivistic values (horizontal collectivism, vertical collectivism, and interdependence) into latent variables. Bivariate correlations among the various indicators of individualistic cultural values ranged from .24 to .52, with a mean of .34. Bivariate correlations among the various indicators of collectivistic cultural values ranged from .44 to .52, with a mean of .48.

We estimated a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to extract latent factors from among the cultural values indicators. Two residual correlations were estimated based on modification indices: vertical collectivism with interdependence (these two constructs are conceptually similar) and vertical individualism with horizontal collectivism (these are conceptually opposite). The fit of the CFA model was evaluated using four fit indices: the comparative fit index (CFI) and non-normed fit index (NNFI), which compare the fit of the specified model to that of a null model with no paths or latent variables; and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), which evaluate the extent to which the covariance structure implied by the model deviates from the covariance structure observed in the data (Kline, 2006). The NNFI and RMSEA are adjusted to penalize models with excessive or unnecessary parameters (Thompson, 2004), and the RMSEA provides a 90% confidence interval. Adequate fit is represented by CFI ≥ .95, NNFI ≥ .90, RMSEA ≤ .08, and SRMR ≤ .06 (Kline, 2006), though a model that satisfies most, but not all, of these criteria should not necessarily be rejected.

The CFA model fit the data well, χ2 (6) = 111.82, p < .001; CFI = .97; NNFI = .92; RMSEA = .082 (90% Cl = .069 to .096); SRMR = .026. Factor loadings (pattern coefficients) for the individualist values construct were: horizontal individualism, .63; vertical individualism, .34; and independence, .81. Factor loadings for the collectivist values construct were: horizontal collectivism, .79; vertical collectivism, .63; and interdependence, .58.

Cultural identifications.

We used two versions of the Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Phinney, 1992) to assess both heritage and U.S. cultural orientations. To assess heritage-culture identifications, we used the original version of the MEIM, which comprises 12 items (α = .91) that assess the extent to which one (a) has considered the subjective meaning of one’s race/ethnicity and (b) feels positively about one’s racial/ethnic group. Sample items include “I think a lot about how my life will be affected by my ethnic group membership” and “I am happy that I am a member of the ethnic group I belong to.” Although the MEIM was originally designed to yield separate subscales for ethnic identity exploration and affirmation, Phinney and Ong (2007) have reviewed evidence supporting the single-factor structure of scores generated by this instrument.

Because few validated measures of U.S. identity exist in the literature, we adapted the MEIM so that “the U.S.” was inserted into each item in place of “my ethnic group” (Schwartz, Park, et al., 2012). Participants were therefore asked to respond to the same MEIM items, this time referring to the United States. The scores on this measure were highly internally consistent (α = .91).

Well-being.

Well-being was measured in terms of subjective well-being, psychological well-being, and eudaimonic well-being. Subjective well-being was assessed using the 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (Pavot & Diener, 1993). This measure has been extensively validated around the world (Kuppens, Realo, & Diener, 2009). A sample item reads: “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal.” In the present dataset, Cronbach’s alpha was .87.

Psychological well-being was measured using the shortened (18-item) version of the Scales for Psychological Well-Being (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). This instrument assesses the dimensions of psychological well-being identified by Ryff (1989): autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. Ten items are worded in a positive direction, and eight are worded in a negative direction. A composite score for psychological well-being is created by reverse-scoring the negatively worded items and summing across the 18 items. A sample item from this instrument reads, “I am quite good at managing the many responsibilities of my daily life.” In the present dataset, Cronbach’s alpha for the composite score was .84.

Eudaimonic well-being was assessed using the Questionnaire on Eudaimonic Well-Being (Waterman et al., 2010). This 21-item measure taps into the extent to which respondents enjoy challenging activities, expend a great deal of effort in activities that they find personally expressive, and spend time pursuing and actualizing their personal potentials. Fourteen of the items are written in an affirmative direction, and seven items are written in a negative direction and are reverse scored. A sample item reads, “I feel I have discovered who I really am.” In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

Following Schwartz, Waterman, et al. (2011), we created a latent variable from among subjective, psychological, and eudaimonic well-being. Supporting this strategy, the three indices of well-being were all strongly related to one another, with correlations of .43, .56, and .70. Because a CFA with only three indicators is saturated and does not provide fit indices, we used a parceling approach (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). The item set for each of the three well-being measures was divided into “first” and “second” halves, and these six half-measures were used as indicators for a well-being latent variable. Error terms for each pair of parcels from the same measure were allowed to correlate with another. This CFA model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(6) = 392.258,p < .001; CFI = .99; NNFI = .96; RMSEA = .085 (90% Cl = .078 to .093); SRMR = .020. Factor loadings ranged from .57 to .85, with a mean of .71.

Results

Bivariate Correlations

Our first step of analysis was to compute bivariate correlations among the study variables, to ensure that the American and heritage cultural indicators could be entered together as independent variables in a model predicting a latent well-being variable. Individualist and collectivist values were treated as latent variables in the correlation matrix that we computed. The correlation matrix was estimated in Mplus release 5.0, using the sandwich covariance estimator (Kauermann & Carroll, 2001) to adjust the standard errors of model parameters for the effects of multilevel nesting (participants within sites).

The correlation matrix is displayed in Table 2. Within each acculturation dimension (American and heritage), the three domains—practices, values, and identifications—were fairly strongly correlated, except for the association between heritage practices and collectivist values (r = .26). Moreover, there was no clear pattern in terms of relationships between “matching” pairs of heritage and American cultural variables; for instance, heritage and American practices were negatively intercorrelated, individualist and collectivist values were strongly and positively correlated, and heritage and American identifications were modestly and positively intercorrelated.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix Among Study Variables

| Variable | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Heritage practices | .26*** | .45*** | −.12*** | .25*** | .03 | .13*** | .07** | .12*** |

| 2. Collectivist values | — | .55*** | .41*** | .65*** | .49*** | .25*** | .24*** | .31*** |

| 3. Ethnic identity | — | .16*** | .44*** | .32*** | .18*** | .22*** | .26*** | |

| 4. American practices | — | .51*** | .57*** | .17*** | .28*** | .21*** | ||

| 5. Individualist values | — | .45*** | .27*** | .38*** | .42*** | |||

| 6. American identity | — | .19*** | .25*** | .27*** | ||||

| 7. Subjective well-being | — | .56*** | .43*** | |||||

| 8. Psychological well-being | — | .70*** | ||||||

| 9. Eudaimonic well-being | — |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Well-Being by Heritage and American Cultural Practices, Values, and Identifications

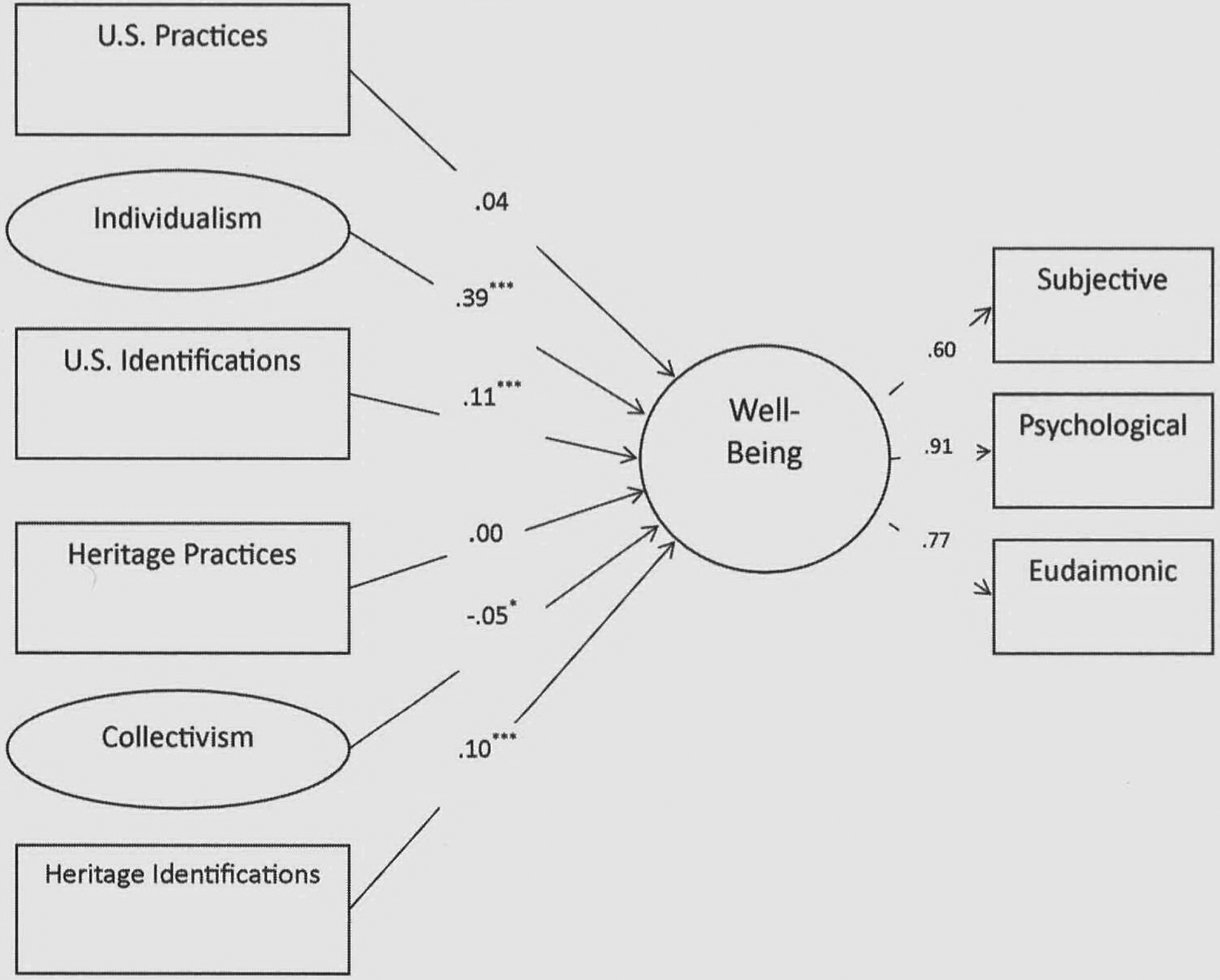

We estimated a structural equation model (Kline, 2006) to examine the associations between acculturation and well-being variables (Figure 1). Each well-being variable was entered as a single indicator (without parceling, because model identification was not a concern). The same residual correlations from the cultural values CFA model were retained in this SEM model. This model fit the data adequately, χ2 (46) = 638.97,p < .001; CFI = .95; NNFI = .92; RMSEA = .070 (95% Cl = .065 to .075); SRMR = .047. Significant predictors of the latent well-being variable included individualist values, β = .38, p < .001; American identity, β = .11,p < .001; and ethnic identity, β =.10, p < .003. Neither heritage nor American cultural practices were significantly associated with well-being at the multivariate level (see Table 3).

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model.

Table 3.

Well-Being by Heritage and American Practices, Values, and Identifications

| Predictor | Dependent variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent variablea | Subjective well-being | Psychological well-being | Eudaimonic well-being | |

| Heritage practices | −.01 | .07*** | −.03 | −.02 |

| Collectivist valuesb | −.04 | .08 | −.10** | −.01 |

| Heritage identifications | .10* | .02 | .11* | .08*** |

| American practices | .04 | .03 | .09 | −.06 |

| Individualist valuesb | .38*** | .15* | .32*** | .38*** |

| American identifications | .11*** | .05* | .07** | .11*** |

Note. Values reported here are standardized regression coefficients.

Unobserved composite with subjective, psychological, and eudaimonic well-being as indicators.

Construct was operationalized as a latent variable.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

We then conducted planned post-hoc decomposition analyses to map the associations of the acculturation dimensions to each of the separate well-being indicators (see Table 3). In a planned post hoc decomposition analysis, the latent dependent variable (well-being in this case) is disassembled into its component indicators, and the study model is re-estimated with the various indicators included as separate outcome variables in place of the latent variable (e.g., Prado, Pantin, Schwartz, Lupei, & Szapocznik, 2006). In this case, we replaced the latent well-being variable with the three well-being indicators; subjective well-being, psychological well-being, and eudaimonic well-being. Decomposition analyses help to ascertain the specific types of well-being that are most closely related to indices of acculturation.

The patterns of associations for psychological and eudaimonic well-being were highly similar to those for the latent well-being variable: Individualist values and American identifications, as well as heritage identifications, emerged as significant positive correlates of psychological and eudaimonic well-being, and collectivist values emerged as a significant negative correlate of psychological well-being. Associations with subjective well-being were smaller and involved positive links with individualist values, American identifications, and heritage practices.

Our final step of analysis was to examine the extent to which the omnibus model (with the latent well-being variable) fit equivalently across gender, across immigrant generation, across the six ethnic groups included in the present sample, and between college towns and urban/suburban settings. To conduct each of these comparisons, we compared a model with all paths and factor loadings constrained equal across gender, immigrant generation, ethnicity, or college setting to a model with all paths and factor loadings free to vary across gender, immigrant generation, ethnicity, or college setting. The null hypothesis of invariance would be rejected if two or more of the following three model comparison criteria were met: Δχ2 significant at p < .05 (Byrne,2009), ΔCFI > .01 (Cheung &Rensvold, 2002), and ΔNNFI > .02 (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Results indicated that the model fit equally across gender, Δχ2 (15) = 7.30, p = .95; ΔCFI < .001; ΔNNFI < .001; across immigrant generation, Δχ2 (15) = 44.56,p < .001; ΔCFI = .003; ΔNNFI < .001; and across ethnicity, Δχ2 (75) = 148.48, p < .001; ΔCFI = .009; ΔNNFI < .001. However, the model did not fit equivalently between college towns and urban/suburban settings, Δχ2 (15) = 124.02,p < .001; ΔCFI = .011; ΔNNFI < .001.

To identify the source of noninvariance across school setting, we returned to the unconstrained model and constrained one path at time (Byrne, 2009). The difference in model fit was evaluated at each subsequent step, using the same model comparison criteria that we used to compare the fully constrained and unconstrained models. The only difference that met criteria for noninvariance was the factor loading for psychological well-being on the latent well-being construct, Δχ2 (1) = 120.24, p < .001; ΔCFI = .024; ΔNNFI = .026. This factor loading was .96 in college towns but .84 in urban/suburban settings. The structural associations between acculturation and well-being were invariant between college towns and urban/suburban settings.

Discussion

The present study used a strengths-based approach to ascertain the associations between acculturation and well-being in a large, multiethnic sample of first-generation and second-generation immigrant college students. Whereas many prior studies have used unidimensional models of acculturation and single indicators of well-being, we operationalized both constructs multidimensionally. We operationalized acculturation using an expanded bidimensional model, including heritage and American cultural practices, values (individualism and collectivism), and identifications. Our multidimensional approach moves beyond proxy measures and beyond a sole reliance on language use and other cultural practices as indices of acculturation.

We also operationalized well-being multidimensionally, using three types of well-being that are related but still somewhat distinct from one another. Our results indicated that a composite latent variable representing the overlap among subjective, psychological, and eudaimonic well-being was most strongly and positively associated with individualist values, as well as identification both as American and with one’s heritage cultural group. This same pattern of correlates also characterized eudaimonic well-being as an observed variable. Subjective well-being was significantly and positively associated with individualist values, American identifications, and heritage practices. Psychological well-being was positively linked with individualist values and with both American and heritage identifications, and negatively with collectivist values. The patterns of associations that we found generalized across gender, between first-generation and second-generation immigrants, and across the six ethnic groups included in the present sample—Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, East/Southeast Asians, South Asians, and Middle Easterners.

Perhaps the clearest finding was the strong positive association of individualist values with psychological and eudaimonic well-being. The tasks included under the heading of psychological well-being include autonomy, environmental mastery, and life purpose, all of which require at least some self-focus to achieve. Eudaimonic well-being is individualistic by definition, given that eudaimonist philosophy states that each person is responsible for discovering and actualizing her or his “true self’ (Norton, 1976; Waterman, 2011). Subjective well-being was less strongly linked with individualism, perhaps because general happiness and satisfaction do not require as much focus on oneself and on one’s own needs, goals, and desires. It should be acknowledged that living in a primarily collectivist society does not preclude some degree of endorsement of individualistic values; self-determination theory, which posits autonomy as one of three basic human needs, has been shown to apply equally to Western and non-Western cultural contexts (Ryan & Deci, 2001).

Research Questions and Empirical Support

Dimensions of acculturation: Heritage and American.

The present results do not support the hypothesis that heritage cultural orientations are most strongly linked with well-being. Indeed, two of the three most prominent correlates of psychological and eudaimonic well-being were individualist values and American identity (ethnic identity was the third). Collectivist values were significantly and positively related to psychological and eudaimonic well-being at the bivariate level, but these associations did not carry over to the multivariate context. The high correlation (r = .65) between individualist and collectivist value systems in the present dataset suggests that this overlap was likely responsible for the difference between the bivariate and multivariate results. This overlap can be interpreted as a form of biculturalism (e.g., LaFromboise, Coleman, & Gerton, 1993; Schwartz & Unger, 2010); that is, these students who adhere strongly to both individualist and collectivist value systems are able to successfully navigate multiple cultural spheres, and this flexibility may be one underlying reason for their high well-being. It should be kept in mind, though, that the indices of well-being used in the present study are individualistic and are grounded in a cultural mindset based on competition, perhaps suggesting that collectivist values are inherently unlikely to explain much variability in these indices of well-being beyond that explained by individualist values. Collectivist-based indicators of well-being, such as collective self-esteem, might have shown more of a unique association with collectivist values.

Domains of acculturation: Practices, values, and identifications.

With regard to the second research question, values—most prominently individualism—appear to be the strongest cultural correlate of well-being. Given the nature of the present sample (i.e., students who have successfully been admitted into colleges or universities), some degree of self-selection may be present in these results. That is, to attain “higher education,” the students in our sample most likely held some degree of individualistic values, which enabled them to navigate prior academic settings successfully enough to be admitted to, and matriculate in, these colleges or universities.

Heritage and American identifications were also modestly associated with both psychological and eudaimonic well-being. According to social identity (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) and self-categorization (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987) theories, identifying with a group provides individuals with direction and with a positive sense of self. Accordingly, identifying with a cultural group—the United States, one’s heritage country or region, or both—may help to provide first-generation and second-generation immigrant students with the confidence and self-direction that they need to function well on a day-to-day basis and to discover and actualize their potentials.

American, but not heritage, identifications were also significantly associated with subjective well-being. Because this finding is based on cross-sectional data, causal inferences cannot be made, and several interpretations are possible. Identifying with the United States may be linked with happiness and satisfaction for a number of reasons, including patriotism as well as a belief that claiming an American identity may elicit approval from one’s peers. Conversely, it may be that those who generally report feeling content may also perceive a stronger sense of belonging to their surrounding culture (e.g., American “mainstream” society). Finally, a third variable could also be involved, such as a general form of optimism potentially explaining both subjective well-being and a strong American identity.

Practices were the weakest and least consistent correlate of well-being. At the multivariate level, the association between subjective well-being and heritage practices appeared to cancel out the bivariate relationship between subjective well-being and ethnic identity. Engaging in heritage-cultural activities, such as speaking one’s heritage language, associating with co-ethnic friends and romantic partners, and engaging with heritage-cultural media, may be enjoyable for many first-generation and second-generation immigrants, and may engender harmony with family members (cf. Portes & Rumbaut, 2006; Zhou & Bankston, 1998). However, such practices may not be related to one’s ability to meet the demands of daily life or to self-realize.

Interestingly, American cultural practices were not significantly associated with any of the well-being indices in a multivariate context. Because the present sample was recruited from college campuses in the United States, use of English was likely universal in the present sample. Moreover, especially in “college towns” where the local environment is organized largely around the university, traditional American “college culture”—based on American cultural practices— is likely to predominate. However, attending an American university does not necessarily mean that individuals will identify as American or hold individualist values. Among those who do, however, all three forms of well-being are likely to be somewhat higher, given the positive associations of American identifications and individualist values with subjective, psychological, and eudaimonic well-being. Sam, Vedder, Ward, and Horenczyk (2006) found a similar positive association between national identification and well-being among immigrant adolescents across 13 countries of settlement. There may be more variability in American identifications than in American practices, and this greater amount of variability may be responsible for the association of American identifications, but not American practices, with the three forms of well-being under study here.

Consistency across gender, ethnicity, and immigrant generation.

Concerning the third research question, the present findings were consistent across gender, ethnicity, and immigrant generation. This consistency suggests that for both men and women, for both first-generation and second-generation immigrants, and for all six ethnic groups under study, individualist values were the strongest correlate of psychological and eudaimonic well-being. Additionally, identification both with the United States and with one’s heritage culture appears to be positively linked with well-being, regardless of the individual’s gender, ethnic group, or birthplace. The present findings thus appear to be quite robust.

Consistency across college settings.

There appeared to be some inconsistency in findings between college towns and urban/suburban settings. However, upon further inspection, only one path was significantly different between these two settings: the extent to which psychological well-being serves as an indicator of overall well-being. Although psychological well-being was strongly linked with overall well-being in both settings, psychological well-being was almost perfectly reflective (λ = .96) of overall well-being in college towns. This finding suggests that flourishing—being able to meet the needs of daily life on one’s own—is especially important for first-generation and second-generation immigrant students who attend universities dominated by American “college culture.” Living on one’s own, often at a distance from family members, decreases the amount of material support that family members are able to provide and may increase the extent to which one is responsible for ensuring that one’s own basic psychological needs are met.

General Discussion

Returning to the primary aim guiding the present study, is acculturation related to well-being among first-generation and second-generation immigrant college students? The answer appears to depend on the specific dimension of acculturation, and the specific dimension of well-being, under consideration. Individualistic values appear to be associated with all three forms of well-being, but beyond that linkage, the picture becomes more complex. In general, identifications (both heritage and American) appear to be more important than practices in terms of links with well-being, with the exception of the association between heritage practices and subjective well-being. Collectivist values were positively related to all three types of well-being at the bivariate level, but with one exception, these associations were no longer present once individualist values were entered into the model, suggesting possible suppressor effects. It should be kept in mind that collectivism does not necessarily contraindicate individualism (Oyserman et al., 2002). In fact, bicultural individuals can successfully adhere to and navigate both cultural value systems to achieve psychological well-being (LaFromboise et al., 1993; Schwartz & Unger, 2010). It is possible, however, that beyond the variability that they share with individualistic values, collectivist values represent a primacy assigned to the group (e.g., family, community) and might be most compatible with collective forms of well-being, rather than with the individualistically based forms of well-being that we examined here.

Given that the participants in our sample were living in a largely individualistic cultural context, it is not surprising that individualistic values were strongly associated with psychological well-being. In more collectivist-based societies, it is likely that collectivistic values (e.g., group harmony, closeness to others) would have been more strongly and consistently linked with well-being. It should be noted, however, that the constructs of subjective (Pavot & Diener, 2008) and psychological (Sheldon et al., 2004) well-being have been shown to function equivalently across Western and non-Western cultural contexts, and similar cross-cultural work on eudaimonic well-being is underway. Moreover, it is encouraging that, although the participants in our sample (and/or their parents) were from a variety of countries characterized by varying extents of individualism and collectivism, the links that emerged between acculturation and well-being were consistent across the six ethnic groups included in the sample.

Strengths and Limitations of the Present Study

The present results should be considered in light of several important study strengths and limitations. In terms of strengths, the use of a sample from various regions of the United States, and including individuals from six major ethnic groups, is a primary strength of the study. A second strength is the multidimensional conceptualizations of acculturation and of well-being, which may help to avoid drawing overly simplistic conclusions regarding the acculturation process and its relationship to well-being in first-generation and second-generation immigrant college students. A third strength is the consideration of consistency of findings across gender, ethnicity, and immigrant generation, suggesting that the findings are applicable to students from immigrant families, regardless of their ethnic background, their gender, or whether or not they were born in the United States. The somewhat different contribution of psychological well-being to the well-being construct in college towns versus other settings may temper this strength to some extent.

In terms of limitations, the cross-sectional design used in our study does not allow for examination of directionality in the associations between acculturation and well-being. Although our theoretical model assumes that acculturation would lead to well-being, it is also possible that one’s levels of well-being may predict one’s trajectory of acculturation. Second, we assessed only direct associations between acculturation and well-being, and we did not attend to mediating variables that may have explained the associations that we found. Because culture represents a distal influence on individual-level outcomes (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), more proximal mediating mechanisms are important to assess in future studies. Third, although we sampled from 30 colleges and universities around the United States, the vast majority of our sites were public universities. There were only three major private universities and three liberal arts colleges, and no historically Black colleges and universities, in our sample— compared with 24 public universities. The experiences of students who attend public universities are therefore likely to exert disproportionate effects on the study results. Nonetheless, we did capture sufficient variability in university setting (college town versus urban/suburban) to be able to test for invariance across these two types of settings.

Implications for Counseling Immigrant College Students

Despite the study limitations, and largely because of the study strengths, the present results may have important implications for counseling college students from immigrant families. The strong and consistent associations between individualistic values and the well-being indices may be reflective of how these values are adopted by young adults who successfully matriculate into colleges and universities in the United States. Although the transition to adulthood is clearly shaped by familial, socioeconomic, and other contextual factors, the exercise of agency is essential within the parameters established by these contextual forces. The transitions from school to work, and from family of origin to family of procreation or choice, rest on the decisions made and paths created in large part (though not entirely) by young people themselves (Côté & Allahar, 1994). Although family and community guidance and support may be available in many cases, the young person her/himself is primarily responsible for creating and navigating a path to higher education and, subsequently, into adulthood (Arnett, 2007; Côté & Levine, 2000).

The individualized transition to adulthood can be liberating and empowering for young people who are able to capitalize on the opportunities available, but it can be frustrating and disheartening to those who experience difficulty initiating and sustaining systematic efforts toward establishing a coherent set of adult roles and commitments (Schwartz, Côté, & Arnett, 2005). The individualized transition to adulthood, which by definition requires some degree of individualism, may also be difficult for students with considerable competing demands, such as family obligations or other similar responsibilities.

Young people from immigrant families may face additional challenges. Many parts of the non-Western world discourage the sort of individualized decision making that has become the norm in the United States (Triandis, 1995). The primary task, then, when working with immigrant college students is to help them to develop the agentic and self-directed orientation that can support making decisions on one’s own, and to do so without violating the traditions and mores of the person’s cultural heritage. For example, for young people from certain cultural backgrounds, it may be necessary to involve family members in the decision making process. Nonetheless, the present results suggest that agency and self-direction are essential for well-being—and perhaps for success—in first-generation and second-generation immigrant students regardless of the part of the world from which they or their families migrated. Clinicians and counselors therefore must strike a balance between (a) facilitating those skills and orientations necessary for making individualized decisions and for making one’s way into adulthood and (b) preserving the person’s cultural heritage. In cases where these two sets of values clash with one another, clinicians may need to help students to resolve the incompatibilities.

Maintaining a bicultural identity—endorsing practices, values, and identifications both from the United States and from one’s country or region of origin—is also important for well-being in immigrant college students. First-generation and second-generation immigrants are, by definition, simultaneously members of their heritage-culture community and of the larger American population (Sam & Berry, 2010; Sam et al., 2006). Taking pride in both of these cultural backgrounds appears to be associated with well-being, as social identity and self-categorization theories would predict (Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner et al., 1987). At the same time, however, some first-generation and second-generation immigrants may experience difficulty integrating and reconciling their heritage and receiving cultural streams (Benet-Martínez & Haritatos, 2005). Whereas our findings indicate that individualist values were closely related to psychological and eudaimonic well-being, it is important to accord respect to the broad range of value perspective expressed by students, whether individualist, collectivist, or a combination of the two. For some, worldviews will remain stable and consistent with family and cultural traditions. For others, worldviews and associated value systems may change, perhaps several times and in differing directions. The findings reported here reflect overall trends, and it should be recognized that changes in any given direction may prove beneficial for some, may be detrimental for others, and may not impact on well-being at all for still others.

In sum, the present study has begun to map the associations between acculturation and well-being in first-generation and second-generation immigrant college students—a growing segment of the American college population. To the extent to which well-being represents an important mental health outcome, the links between acculturation—a task that most immigrants and their children face—and well-being are essential to study and to capitalize on in the counseling context. We hope that the present results will find their way into practice and into helping students from immigrant families to thrive in an increasingly multicultural but still individualistic American society.

Footnotes

Our definition of acculturation subsumes the construct of “enculturation,” which is also used to refer to heritage-culture retention (Weinreich, 2009).

Unless otherwise specified, a five-point Likert scale was used for each measure, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

References

- Abraido-Lanza AE, Armbrister AN, Florez KR, & Aguirre AN (2006). Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1342–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afable-Munsuz A, & Brindis CD (2006). Acculturation and the sexual and reproductive health of Latino youth in the United States: A literature review. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38, 208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar S (1999). The immigrant, the exile, and the experience of nostalgia. Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 1, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Alba RD, & Nee V (2006). Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martinez V, & Haritatos J (2005). Bicultural identity integration (BII): Components and psychosocial antecedents. Journal of Personality, 73, 1015–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW (1980). Acculturation as varieties of adaptation In Padilla AM (Ed.), Acculturation: Theory, models, and some new findings (pp. 9–25). Boulder, CO: Westview. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM (2009). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Cano MA, Chen SW, Blucker RT, & Olds TS (2008). Family conflict and intragroup marginalization as predictors of acculturative stress in Latino college students. International Journal of Stress Management, 15, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chae MH, & Foley PF (2010). Relationship of ethnic identity, acculturation, and psychological well-being among Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling and Development, 88, 466–476. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, & Rensvold RB (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Chia A-L, & Costigan CL (2006). A person-centred approach to identifying acculturation groups among Chinese Canadians. International Journal of Psychology, 41, 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Maldonado-Molina M, Pantin H, & Szapocznik J (2005). A person-centered and ecological investigation of acculturation strategies in Hispanic immigrant youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 33, 157–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan CL (2010). Embracing complexity in the study of acculturation gaps: Directions for future research. Human Development, 53, 341–349. [Google Scholar]

- Côté JE, & Allahar AL (1994). Generation on hold: Coming of age in the late twentieth century. Toronto: Stoddart. [Google Scholar]

- Côté JE, & Levine CG (2000). Attitude versus aptitude: Is intelligence or motivation more important for positive higher-educational outcomes? Journal of Adolescent Research, 15, 58–80. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York, NY: Harper-Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E (2006). Guidelines for national indicators of subjective well-being and ill-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 397–404. [Google Scholar]

- Durkin J, & Joseph S (2009). Growth following adversity and its relation with subjective well-being and psychological well-being. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14, 228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, & Vega WA (2003). Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health, 5(3), 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M (1964). Assimilation in American life. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman BK, Read JG, & Krueger PM (2010). Gender, acculturation, and health among Mexican Americans. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51,440–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco EM, & Trevelyan EN (2010). Place of birth of the foreign-born population, 2009 (American Community Survey Brief ACSBR/09–15). Washington, DC: US. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Schwartz SJ, & McCabe BE (2008). Aging, gender, and self: Dimensionality and measurement invariance analysis on self-construal. Self and Identity, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DJ, Denton NA, & Macartney SE (2007). Family circumstances of children in immigrant families: Looking to the future of America In Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K, & Bornstein MH (Eds.), Immigrant families in contemporary society (pp. 9–29). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman EC (2003). Men, dogs, and cars: The semiotics of rugged individualism. Journal of Advertising, 32(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G (2001). Culture’s consequences (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LM, Schneider S, & Comer B (2004). Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on U.S. Hispanics. Social Science and Medicine, 59, 973–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger DA (2008). Green cards and the location choices of immigrants in the United States, 1971–2000. Research in Labor Economics, 27, 131–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg AL (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review, 74, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kasinitz P, Mollenkopf JH, Waters MC, & Holdaway J (2008). Inheriting the city: The children of immigrants come of age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kauermann G, & Carroll RJ (2001). A note on the efficiency of sandwich covariance matrix estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 96, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon DB, & Carter JS (2011). Ethnic identity, sense of community, and psychological well-being among Northern Plains American Indian youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2006). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens P, Realo A, & Diener E (2008). The role of positive and negative emotions in life satisfaction judgment across nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T, Coleman HLK, & Gerton J (1993). Psychological impact of biculturalism: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 395–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Yoon E, & Liu-Tom H-TT (2006). Structure and measurement of acculturation/enculturation for Asian Americans: Cross-cultural validation of the ARSMA-II. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 39, 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, & Widaman KF (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Class M, Castro FG, & Ramirez AG (2011). Conceptions of acculturation: A review and statement of critical issues. Social Science and Medicine, 72, 1555–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lueck K, & Wilson M (2011). Acculturative stress in Latino immigrants: The impact of social, socio-psychological, and migration-related factors. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 186– 195. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo Steidel AG, & Contreras JM (2003). A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 312–330. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery MJ, & Côté JE (2003). College as a transition to adulthood In Adams GR & Berzonsky MD (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of adolescence (pp. 149–172). Malden, MA: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HH, & von Eye A (2002). The Acculturation Scale for Vietnamese Adolescents (ASVA): A bidimensional perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26, 202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Norton DL (1976). Personal destinies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Coon HM, & Kemmelmeier M (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YS, & Kim BSK (2008). Asian and European American cultural values and communication styles among Asian American and European American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W, & Diener E (2008). The Satisfaction with Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Cantu CL, & Kurtz DA (1997). Ethnic and American identity as predictors of self-esteem among African American, Latino, and White adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26,165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Ong AD (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, & Rumbaut RG (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant second-generation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, & Rumbaut RG (2006). Immigrant America: A portrait (3rd ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Lupei N, & Szapocznik J (2006). Predictors of engagement and retention into a parent-centered, ecodevelopmental HIV preventive intervention for Hispanic adolescents and their families. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31, 874–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JR, Crano WD, Quist R, Burgoon M, Alvaro EM, & Grandpre J (2004). Acculturation, familism, parental monitoring, and knowledge as predictors of marijuana and inhalant use in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18,3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudmin FW (2003). Critical history of the acculturation psychology of assimilation, separation, marginalization, and integration. Review of General Psychology, 7, 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Deci EL (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, & Keyes CLM (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, & Singer BH (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sam DL, & Berry JW (2010). Acculturation: When individuals and groups of different backgrounds meet. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 472–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sam DL, Vedder P, Ward C, & Horenczyk G (2006). Psychological and sociocultural adaptation of immigrant youth In Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, & Vedder P (Eds.), Immigrant youth in cultural transition (pp. 117–142). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, & Unger JB (2010). Biculturalism and context: What is biculturalism, and when is it adaptive? Human Development, 53, 26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Côté JE, & Arnett JJ (2005). Identity and agency in emerging adulthood: Two developmental routes in the individualization process. Youth and Society, 37, 201–229. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Montgomery MJ, & Briones E (2006). The role of identity in acculturation among immigrant people: Theoretical propositions, empirical questions, and applied recommendations. Human Development, 49, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Park IJK, Huynh Q-L, Zamboanga BL, Umana-Taylor AJ, Lee RM, Rodriguez L, Kim SY, Whitboume SK, Castillo LG, Weisskirch RS, Vazsonyi AT, Williams MK, & Agocha VB (2012). The American Identity Measure: Development and validation across ethnic subgroup and immigrant generation. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, & Szapocznik J (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist, 65, 237–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]