Abstract

Perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty are two understudied acculturative stressors frequently experienced by Asian Americans. This study expanded the family stress model to examine how parental experiences of these two acculturative stressors relate to measures of adolescent adjustment (depressive symptoms, delinquent behaviors, and academic performance) during high school and emerging adulthood through interparental and parent–child relationship processes. Participants were 350 Chinese American adolescents (Mage = 17.04, 58 % female) and their parents in Northern California. Path models showed that parental acculturative stressors positively related to parent–child conflict, either directly (for both mother–adolescent and father–adolescent dyads) or indirectly through interparental conflict (for mother–adolescent dyads only). Subsequently, both interparental and parent–child conflict positively related to a sense of alienation between parents and adolescents, which then related to more depressive symptoms, more delinquent behaviors, and lower academic performance in adolescents, for mother–adolescent and father–adolescent dyads. These effects persisted from high school to emerging adulthood. The results highlight the indirect effects of maternal and paternal acculturative stressors on adolescent adjustment through family processes involving interparental and parent–child relationships.

Keywords: Acculturative stress, Chinese American, Interparental relationship, Parent–child relationship, Adolescent adjustment

Introduction

Asian Americans are the second largest and the fastest growing immigrant population in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Like other ethnic minority groups in the United States, they may experience various acculturative stressors, such as discrimination, perpetual foreigner stereotype, and bicultural management difficulty (Grossman and Liang 2008; Kim et al. 2014a; Lee et al. 2009). Compared to studies on discriminatory experiences, studies on acculturative stressors like perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty are relatively rare, particularly when it comes to understanding their impact on the adjustment of Asian American adolescents (Xia et al. 2013). Perpetual foreigner stereotype describes individuals’ experience of being stereotyped as a perpetual foreigner (e.g., being assumed to be from another country; Lee et al. 2009). Bicultural management difficulty refers to individuals’ difficulty in managing ethnic and mainstream cultures simultaneously (e.g., feeling difficulty balancing two cultures; Kim et al. 2014a). A small yet growing number of studies have demonstrated that Asian Americans’ experiences of these two acculturative stressors are related to their own adjustment (Armenta et al. 2013; Huynh et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2014a). To date, however, it is unknown whether and how parental experiences of these two acculturative stressors ultimately relate to their adolescents’ adjustment.

Parents’ experiences of perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty may be regarded as family stressors. According to the family stress model, family stressors can influence interparental and parent–child relationship processes, which, in turn, impact child development (Conger and Donnellan 2007). Therefore, the current study examined whether parents’ experiences of perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty influence adolescent adjustment through interparental and parent–child relationships among Asian American families. As acculturative stressors may not necessarily relate to different domains of adolescent adjustment in the same way, we simultaneously examined three main aspects of adolescent adjustment—depressive symptoms, delinquent behaviors and academic performance—to represent diverse aspects of adolescent adjustment. In addition, we tested whether the mediating family processes vary across parental gender. To address these research questions, we analyzed a two-wave longitudinal data set (spanning from high school to emerging adulthood) of Chinese Americans, the largest subgroup of Asian Americans (U.S. Census Bureau 2010).

Perpetual Foreigner Stereotype and Bicultural Management Difficulty

Asian Americans are often viewed as “perpetual foreigners” who are unlikely to assimilate into the mainstream culture, no matter where they were born or how long their families have resided in the U.S. (Lee et al. 2009). Empirical studies have demonstrated that experiences of being stereotyped as a perpetual foreigner (e.g., being criticized for speaking Chinese or for not speaking/writing English well) are pervasive in the everyday lives of Asian Americans (Ong et al. 2013; Sue et al. 2009). For example, a daily diary study from Ong et al. (2013) showed that perpetual foreigner stereotype was an example of microaggression most commonly reported by Asian Americans. Extensive evidence suggests that overt forms of discrimination are associated with the adjustment of Asian Americans (Grossman and Liang 2008; Yip et al. 2008). Likewise, more subtle forms of ethnic discrimination, such as being stereotyped as a perpetual foreigner, can also affect adjustment in Asian Americans (Armenta et al. 2013; Huynh et al. 2011). For example, Huynh et al. (2011) revealed that experiences of being stereotyped as a perpetual foreigner significantly predicted a lower sense of belonging to American culture, increased identity conflict, and lower levels of hope and life satisfaction in Asian Americans, even after controlling for perceived levels of discrimination. It is noteworthy that, although some foreigner stereotypes indeed ring true for many foreign-born individuals (e.g., being from another country and not speaking English well), confronting such stereotypes can still be stressful for the foreign-born, because of the desire to fit in and be considered as insiders rather than outsiders in the U.S. (Armenta et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2009). Indeed, it has been demonstrated that, for both U.S.-born and foreign-born Asian Americans, perpetual foreigner stereotypes were related to identity denial (Armenta et al. 2013).

In addition to perpetual foreigner stereotype imposed on them from the outer world, Asian Americans may experience internal challenges as they navigate between two distinct cultures (Cheah et al. 2013; Kim et al. 2014a). For example, they may detect contradictions between their ethnic culture and the American culture (e.g., the Chinese culture values interdependence whereas the American culture values independence in interpersonal relationships; Markus and Kitayama 1991); they may find it difficult to determine which cultural practices to follow in certain situations; and they may feel it is hard to balance between the two cultures. Bicultural management difficulty refers to these internal struggles in navigating between ethnic and mainstream cultures. It involves experiences of cultural conflict, but focuses more on internal feelings of difficulty in balancing and managing the two cultures. In contrast, the concept of bicultural identity integration (Benet-Martínez and Haritatos 2005) focuses on how bicultural individuals consider their two identities to intersect or overlap. Bicultural management difficulty can be studied among ethnic minorities living in a bicultural context, in order to examine the degree to which this experience varies among individuals, given that they may encounter no difficulty, moderate difficulty, or much difficulty as they navigate between the two cultures. Bicultural management difficulty may be associated with poorer adjustment (Kim et al. 2014a; LaFromboise et al. 1993). For example, a recent study demonstrated that bicultural management difficulty was associated with more parental depressive symptoms, more punitive parenting, less democratic parenting, and less inductive reasoning in Chinese Americans (Kim et al. 2014a).

Extending the Family Stress Model to Acculturative Stressors

The family stress model is based on studies of European American families experiencing economic hardship (Conger et al. 1992; Conger et al. 1994). Further empirical evidence is needed to evaluate whether the general tenets of the family stress model apply to stressors beyond economic hardship and to populations other than European Americans. Some recent efforts have extended the family stress model to examine the effects of an acculturative stressor called parent–child acculturation discrepancy on child outcomes in Mexican–American families (Lau et al. 2005; Schofield et al. 2008) and Chinese American families (Lim et al. 2008; Ying and Han 2007). These studies have demonstrated that parent–child acculturation gap is related to parent–child relationship processes (e.g., parent–child conflict), which, in turn, is associated with measures of adolescent adjustment, such as depressive symptoms. Note that these studies examined only the mediating role of the parent–child relationship, leaving the potential mediating role of the interparental relationship unexplored.

In concert with the family stress model, the current study proposes that acculturative stressors (i.e., perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty) may influence interparental and parent–child conflicts; subsequently, both types of conflicts may be associated with adolescents’ sense of alienation toward parents, which then may affect adolescent adjustment. The family stress model and prior literature on stress spillover have suggested that parental stress may affect family processes as stress could spill over to family interactions; for example, stress may make parents less patient and more emotionally distressed during their interactions, thus resulting in more family conflicts (Conger and Donnellan 2007; Schulz et al. 2004; Story and Repetti 2006). Extant studies have provided some evidence of an association between acculturative stressors and interparental or parent–child relationship (Caetano et al. 2007; Farver et al. 2002; Lim et al. 2008; Ying and Han 2007). For example, acculturative stress (e.g., problems in English communication and conflicts regarding cultural values) was related to increased intimate partner violence (Caetano et al. 2007), and parent–child acculturation gap was associated with a higher level of parent–child conflict longitudinally during adolescence (Farver et al. 2002; Lim et al. 2008; Ying and Han 2007).

Interparental conflicts, especially those exposed to children, are harmful for parent–child relationships (Grych et al. 1992; Reese-Weber and Hesson-McInnis 2008). Intense and unresolved interparental conflicts have been demonstrated to increase parent–child conflicts and sense of alienation, probably because they often create emotional distress in parents, which makes parents less emotionally available in parent–child interactions (Bradford et al. 2008; El-Sheikh and Elmore-Staton 2004; Gerard et al. 2006). Both interparental and parent–child conflicts can aggravate adolescents’ sense of alienation from parents by weakening the parent–child bond and driving adolescents away from their parents (Choi et al. 2008; El-Sheikh and Elmore-Staton 2004). Consequently, poorer parent–child relationship quality (e.g., alienation) can lead to negative outcomes in various domains of adolescent development, such as more depressive symptoms, delinquent behaviors, and weaker academic performance (Chao 2001; Gerard et al. 2006; Raudino et al. 2013).

Parental Gender Difference

Paternal and maternal stress may influence adolescent adjustment through different family pathways. First, there are gender differences in responding to stress, with a female’s (vs. male’s) stress being more likely to spill over into her intimate relationships (Schulz et al. 2004; Story and Repetti 2006). For example, work stress was more strongly related to the quality of the marital relationship for women than for men (Schulz et al. 2004; Story and Repetti 2006). In contrast, paternal stress is more likely to affect father–child interaction. According to the fathering-vulnerability hypothesis (Cummings et al. 2004), father–child interaction may be more susceptible to external stress, probably because the parenting role of fathers is less clearly defined by social conventions than that of mothers. Indeed, Schofield et al. (2008) demonstrated that the parent–child acculturation gap was more strongly associated with parent–child conflict for father–child dyads than for mother–child dyads. Therefore, maternal acculturative stressors may be more likely to influence adolescent adjustment through interparental relationships, whereas paternal acculturative stressors may be more likely to affect adolescent adjustment through parent–child relationships. However, most studies that adopt the family stress model as a framework focus on mother–child dyads only, or fail to compare mother–child and father–child dyads (Chen et al. 2014; Conger et al. 2002; Lim et al. 2008).

The Present Study

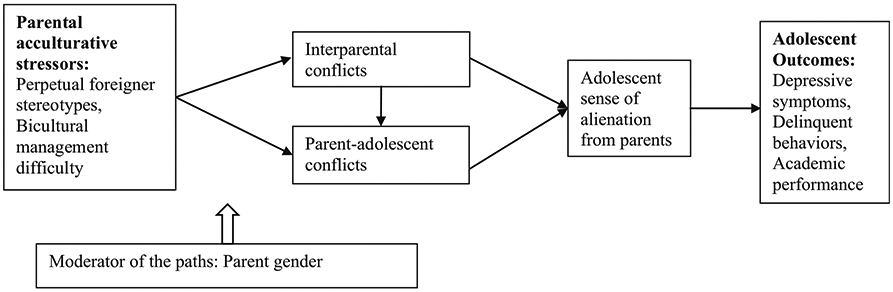

The present study adopted the family stress model to examine whether and how Asian American parents’ experiences of two understudied acculturative stressors—perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty—indirectly relate to measures of adolescent adjustment (depressive symptoms, delinquent behaviors, and academic performance) during high school and emerging adulthood. The conceptual model is depicted in Fig. 1. First and foremost, we tested both the interparental relationship (i.e., conflict) and the parent–child relationship (i.e., conflict and alienation) as potential mediators linking parental acculturative stressors and adolescent adjustment. We proposed that acculturative stressors experienced by parents would be positively related to parent–child conflicts, either indirectly, through interparental conflicts, or directly; subsequently, both interparental and parent–child conflicts would relate to higher levels of parent–child alienation, which then would relate to negative outcomes in adolescents. Second, we also tested whether the mediational model operated differently for father–adolescent and mother–adolescent dyads. We hypothesized that pathways linking parental acculturative stress to adolescent outcomes may be different for father–adolescent and mother–adolescent dyads, with parent–child conflicts being more salient for father–adolescent dyads and interparental conflicts playing a larger role for mother–adolescent dyads.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model linking parental acculturative stressors, interparental conflicts, parent–adolescent conflict, alienation, and adolescent outcomes

Method

Participants

This study used Wave 2 and Wave 3 data from a three-wave longitudinal study of 444 Chinese American families with data gathered every 4 years. We did not include Wave 1 data because some key constructs of interest for this study (e.g., perpetual foreigner stereotype and interparental conflict) were not assessed at Wave 1. For the current study, there were 350 families in Wave 2 (when adolescents were in eleventh or twelfth grade) and 330 families in Wave 3. The age of the adolescents (58 % female) at Wave 2 ranged from 16 to 19 (M = 17.04, SD = 0.73) years old. The majority of fathers (87 %) and mothers (90 %) were born outside the U.S., whereas most of the adolescents (75 %) were born in the U.S. The majority of foreign-born parents migrated from southern provinces of China or Hong Kong, with fewer than 10 families hailing from Taiwan. Most of the fathers (83.4 % at Wave 2 and 73.4 % at Wave 3) and mothers (81.8 % at Wave 2 and 76.4 % at Wave 3) were employed at least part-time. The parents held various occupations, ranging from low-skill jobs (e.g., construction work) to professional work (e.g., banking or computer programming). The median (and average) family income was in the range of $45,001–$60,000 for both waves. The median (and average) parental education level was high school education for both fathers and mothers at both waves. Most of these families speak Cantonese, with less than 10 % speaking Mandarin as their home language.

Procedure

Participants were initially recruited from seven middle schools in two school districts in major metropolitan areas of Northern California, in 2002. At each of these schools, Asian Americans comprised at least 20 % of the student body. The research staff identified Chinese American students and contacted their families with the assistance of school administrators. Parent and adolescent consent forms were collected before questionnaires were distributed. The consent rate was 47 % among those families who were contacted. Participants were instructed to complete the questionnaires alone, and to seal their questionnaires in the provided envelopes immediately after completing them. About two to 3 weeks after distributing questionnaires, research staff collected completed surveys at the participating schools during the students’ lunch periods. Of the families receiving questionnaires, 76 % completed them. Four years later, families who had returned surveys in the initial wave were contacted for a follow-up (Wave 2) using the same procedures as the first wave of data collection. Again, a follow-up survey (Wave 3) was conducted after another 4 years, with questionnaires being distributed and collected through the mail or online.

Questionnaires were prepared in English and Chinese. The questionnaires were first translated to Chinese and then back-translated to English. Any inconsistencies with the original English version scale were resolved by bilingual/bicultural research assistants, with careful consideration of culturally appropriate meanings of items. Around 71 percent of parents used the Chinese language version of the questionnaire, and the majority (over 80 %) of adolescents used the English version.

The attrition rate from Wave 1 to Wave 2 was 21 %, from Wave 1 to Wave 3 was 26 %. Attrition analyses were conducted at Waves 2 and 3 to compare families who participated with those who had dropped out on the demographic variables measured at Wave 1 (i.e., parental education, family income, parent and child generational status, parent and child age). Only one significant difference emerged: boys were less likely than girls to have continued participating, χ2(1) = 7.20–10.41, p < .01.

Measures

Perpetual Foreigner Stereotype

Parents’ perceived experiences of being stereotyped as perpetual foreigners were examined using a five-item scale that has demonstrated high reliability and strong validity with other acculturative stressors, such as discrimination, in a Chinese American sample (Kim et al. 2011). Sample items include “People assume I am a FOB (fresh-off-the-boat)” and “People assume I am from another country.” Fathers and mothers separately self-reported the frequency of such experiences in their daily life, on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). Higher mean scores indicate being stereotyped as a foreigner more frequently (αs = .78 to .82, across informants and waves).

Bicultural Management Difficulty (BMD)

Parents’ perceived experiences of difficulty in managing the U.S. and Chinese cultures were examined using a six-item scale that has demonstrated high reliability and strong validity with cultural orientations and depressive symptoms in a study by Kim et al. (2014a). Sample items include “difficult to balance two cultures” and “difficult to know when I need to be more Chinese or American in a certain situation.” Fathers and mothers separately self-reported their bicultural difficulty on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (always). Higher mean scores indicate more bicultural management difficulty (αs = .85 to .90, across informants and waves).

Interparental Conflict

Interparental conflict exposed to adolescents was assessed using five items adapted from the Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale (CPIC), which measures multiple aspects of conflict, including but not limited to conflict intensity and resolution (Grych et al. 1992). The scale has been well validated in previous studies, including some with Chinese samples (Reese-Weber and Hesson-McInnis 2008). The current study adapted four items assessing conflict intensity (e.g., “My parents yell a lot when they argue”) and one item assessing conflict resolution: “When my parents disagree about something, they cannot come up with a solution.” Adolescents reported on a scale of 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true). Higher mean scores reflect higher interparental conflict (α = .88 at Wave 1 and α = .89 at Wave 2).

Parent–Child Conflict

Parent–child conflict was measured using the ten-item Asian American Family Conflicts Scale (Lee et al. 2000). Sample items include “Your parent tells you that a social life is not important at this age, but you think that it is” and “You have done well in school, but your parent always wants you to do even better.” Adolescents reported how often these conflicts occurred with their mother and father separately, on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Higher mean scores indicate higher parent–child conflict (αs = .86 to .91 across parents and waves).

Sense of Alienation in Parent–Child Relationship

Sense of alienation was assessed through the Alienation subscale of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden and Greenberg 1987). This scale has been widely used in previous studies, including some focusing on Chinese Americans (Ying et al. 2007). Adolescents reported their sense of alienation from their parents on eight items (e.g., “I feel angry with my parents” and “I don’t get much attention at home”) using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); higher mean scores indicate a higher sense of alienation (α = .87 at Wave 1 and α = .86 at Wave 2).

Depressive Symptoms

Adolescents’ self-reports of depressive symptoms were collected by means of the widely-used Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff 1991). This scale has been validated in samples of Chinese American adolescents and young adults (Juang and Cookston 2009; Ying et al. 2007). Participants responded to 20 statements, using a scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most of the time), with higher mean scores indicating more depressive symptoms (αs = .90 at both waves).

Delinquent Behaviors

Adolescents’ delinquent behaviors at Wave 2 were measured with items adopted from the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001) assessing behaviors such as stealing, running away, and lying. For Wave 3, we added seven items to the scale; these were adopted from a previous study on delinquency in Asian American adolescents (Le and Stockdale 2005) and included items such as “I fail to pay my debts or meet other financial responsibilities.” We added these items to capture delinquent behaviors that are more relevant for emerging adults, since target adolescents were in their early twenties at Wave 3. Adolescents reported on their own problems during the past 6 months on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 2 (often true or very true), with higher mean scores reflecting more delinquent behaviors (α = .71 at Wave 1 and α = .83 at Wave 2).

Academic Performance

Adolescents’ academic performance was measured using their self-reported school Grade Point Average (GPA). Adolescents reported on a scale ranging from 1 (F) to 13 (A plus). A higher score represents higher academic performance. The average GPA was 8.85 (SD = 2.03, between B and B−) at Wave 2 and 7.00 (SD = 1.88, C+) at Wave 3. At Wave 3, 300 youths reported their grades; others (n = 30) did not report their grades, either because they were not in college (n = 21) or because they elected not to provide that information (n = 9).

Covariates

The current study controlled for several important covariates. First, family economic stress, parental educational level, and parental employment status (0 = unemployed, 1 = employed at least part-time) were included in the model as covariates for all study variables, because they have been associated with acculturative stress, family relationships, and child developmental outcomes (Garcia Coll et al. 1996; Lueck and Wilson 2010; Mistry et al. 2009). On a scale of 1 (no formal schooling) to 9 (finished graduate degree), parents reported on their highest education level. Parental economic stress was measured with two items: “Think back over the past 3 months. How much difficulty did you have with paying your bills?”, with responses ranging from 1 (a great deal) to 5 (none at all), and “Think back over the past 3 months. Generally, at the end of each month, how much money did you end up with?,” with ratings ranging from 1 (more than enough) to 5 (very short). These items have been validated in previous studies of Chinese American families (Mistry et al. 2009). Mean scores of parents’ reports on these two items were taken (after reverse coding the first item) to indicate family economic stress, with higher scores reflecting a greater degree of economic stress. Second, parental nativity was included as a covariate of parental acculturative stressors, as previous studies have demonstrated that first-generation immigrants—those born outside of the U.S. (vs. those born in the U.S.) experience more acculturative stress (Kim and Omizo 2005). Finally, adolescents’ nativity, gender, and age were examined as covariates of all adolescent-reported study variables because they have been shown to be related to various aspects of adolescent adjustment (Kwak 2003; Steinberg and Morris 2001).

Analytic Strategy

To test our hypotheses, path analyses were conducted using Mplus 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2015) using full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR). Missing data were handled through full information maximum likelihood (FIML). Inferences for the indirect effects were estimated using the delta method (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2015).

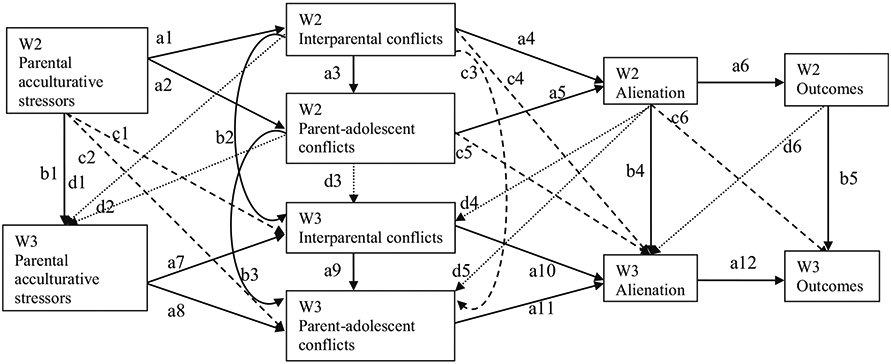

To test whether parental acculturative stressors related to adolescent outcomes indirectly through family processes, we analyzed a path model shown in Fig. 2. MacCallum and Austin (2000) recommended that when estimating longitudinal effects, researchers should include autoregressive effects of their constructs, as well as concurrent relations between the constructs, as they may intervene in the longitudinal relations. Thus, in our model, we tested concurrent, stability (autoregressive), and longitudinal (cross-lagged) relations among the study constructs simultaneously. Concurrent relations were tested among all Wave 2 variables and among all Wave 3 variables (a paths). Stability (autoregressive) paths were specified for the same constructs across waves (b paths). Cross-lagged (longitudinal) paths were specified for distinct constructs from Wave 2 to Wave 3 (c paths). This model specification allowed us to not only examine concurrent relations (a paths), but also to examine longitudinal relations (c paths) while controlling for prior levels of study variables (b paths). Most importantly, it also allowed us to examine whether the longitudinal relations (c paths) were mediated by the concurrent and stability paths.

Fig. 2.

Path model analyzed. Note: a1–a12 path (bolded solid lines): concurrent relationships; b1–b5 path (solid lines): stability paths; c1–c6 path (dashed lines): cross-lagged paths; d1–d6 path (dotted lines): alternative cross-lagged paths. W Wave. N = 350. In total, four separate models were fitted, using either parental perpetual foreigner stereotype or parental bicultural management difficulty as the exogenous variable, in two types of parent–adolescent dyads (father–adolescent and mother–adolescent). Three measures of adolescent outcomes were included in a model simultaneously

In addition, there may be potential bidirectional relations between the study variables (Elkins et al. 2014; Erel and Burman 1995; Hou et al. 2015; Sameroff and MacKenzie 2003). For example, parent–child relationships may also affect marital relationships (Erel and Burman 1995) and adolescents’ adjustment may also affect their relationships with parents (Elkins et al. 2014; Sameroff and MacKenzie 2003). To test these potential alternative causal direction of the relations between study variables, we specified alternative cross-lagged paths from Wave 2 to Wave 3 (d paths). Hence, the current analytical approach could provide a most comprehensive understanding of the relations between study variables.

In total, four separate models were fitted, using either parental perpetual foreigner stereotype or parental bicultural management difficulty as the exogenous variable, in two types of parent–adolescent dyads (father–adolescent and mother–adolescent). As one of the first endeavors linking parental experiences of perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty to adolescent adjustment, this study intended to examine the separate effects of each of these two conceptually distinct acculturative stressors. We included all three adolescent outcomes (depressive symptoms, delinquent behaviors, and academic performance) simultaneously in the model.

To compare the model across parent gender, we first tested the measurement equivalence of perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty across parental gender using confirmatory factor analysis by following similar procedures as in prior studies (Kim et al. 2014b; Millsap and Yun-Tein 2004). Metric invariance of these two measures across parental gender was reached, suggesting that comparison of their relations with other variables across parental gender is appropriate (Little 1997). After establishing measurement equivalence across parental gender, we tested whether the link between parental acculturative stressors and family conflicts (a1, a2, a7, a8, c1, and c2 paths) were significantly different between father–adolescent and mother–adolescent dyads. Data for father–adolescent and mother–adolescent dyads were modeled within the same covariance matrix (Benner and Kim 2009). A base model was first fitted, allowing all structural paths to be freely estimated between father–adolescent dyads and mother–adolescent dyads. Then, individual paths were constrained, one at a time, to determine if they were significantly different across groups. The Satorra–Bentler Scaled Chi square test was used to determine whether a more constrained model fitted the data significantly worse than a less constrained one.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the study variables. Observation of the zero-order correlations showed initial support for our hypotheses. In general, parental acculturative stressors were positively related to marital and parent–child conflicts; both types of family conflicts were positively associated with parent–child alienation, which was correlated with more depressive symptoms, delinquent behaviors, and lower academic performance among adolescents, either concurrently or longitudinally. There seems to be parent gender difference in the relation between acculturative stressors and family conflicts. Specifically, parental acculturative stressors were positively related to parent–child conflict for both mother–adolescent and father–adolescent dyads, whereas parental acculturative stressors were positively related to interparental conflict only among mother–adolescent dyads.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations among study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perpetual foreigner stereotype W2 | .41*** | .47*** | .12+ | .23*** | .12+ | .09 | −.02 | −.17** | .65*** | .33*** | .09 | .15* | .03 | .12+ | .01 | −.12+ | 2.41 | 0.72 |

| 2. Bicultural management difficulty W2 | .53*** | .42*** | .11+ | .24*** | .19** | .11+ | .09 | −.13* | .43*** | .42*** | .04 | .14* | .09 | .17** | .10 | −.08 | 2.81 | 0.74 |

| 3. Interparental conflict W2 | .16** | .17** | – | .20** | .38*** | .23*** | .03 | −.03 | .19** | .08 | .55*** | .20*** | .34*** | .24*** | .05 | .01 | 2.48 | 0.97 |

| 4. Parent–child conflict W2 | .20*** | .12* | .32*** | .81*** | .42** | .27*** | .17* | .19** | .27*** | .22*** | .22*** | .50*** | .25*** | .22*** | .16** | −.02 | 2.67 | 0.90 |

| 5. Alienation W2 | .09 | .07 | .38*** | .51*** | – | .47*** | .24*** | −.21*** | .10 | .14* | .29*** | .25*** | .51*** | .24*** | .11+ | −.12* | 2.80 | 0.73 |

| 6. Adolescent depression W2 | .15* | .07 | .23*** | .31*** | .47*** | – | .26** | −.26** | .08 | .09 | .24*** | .20*** | .35*** | .49*** | .28*** | −.20*** | 0.71 | 0.46 |

| 7. Adolescent delinquency W2 | .08 | .04 | .03 | .15*** | .24*** | .26** | – | −.25*** | .00 | −.04 | .17** | .08 | .11+ | .20*** | .40*** | −.04 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| 8. Grades W2 | .03 | .01 | −.03 | −.17** | −.21*** | −.26** | −.25*** | – | −.16* | −.09 | −.15* | −.20***- | −.19** | −.18** | −.23*** | −.46*** | 4.42 | 2.03 |

| 9. Perpetual foreigner stereotype W3 | .54*** | .47*** | .18** | .19** | .09 | .08 | .09 | −.08 | .56*** | .38*** | .17** | .25*** | .14* | .14* | .06 | −.24** | 2.43 | 0.69 |

| 10. Bicultural management difficulty W3 | .37*** | .57*** | .12+ | .16* | .09 | .10+ | −.06 | −.00 | .46*** | .45*** | −.02 | .22*** | .12+ | .15* | .08 | −.06 | 2.84 | 0.85 |

| 11. Interparental conflict W3 | .11 | .07 | .55*** | .22*** | .29*** | .24*** | .17** | −.15* | .08 | .08 | – | .28*** | .36*** | .24*** | .15* | −.07 | 2.27 | 0.95 |

| 12. Parent–child conflict W3 | .16* | .13* | .27*** | .53*** | .32*** | .22*** | .10 | –−.20*** | .17** | .14* | .30*** | .80*** | .41*** | .25*** | .18** | −.10 | 2.34 | 0.89 |

| 13. Alienation W3 | .11+ | .03 | .34*** | .35*** | .51*** | .35*** | .11+ | −.19** | .13* | .05 | .36*** | .54*** | – | .42*** | .27*** | −.23*** | 2.65 | 0.73 |

| 14. Adolescent depression W3 | .09 | .07 | .24*** | .23*** | .24*** | .49*** | .20** | −.18** | .10+ | .15* | .24*** | .30*** | .42*** | – | .32*** | −.25*** | 0.63 | 0.45 |

| 15. Adolescent delinquency W3 | −.04 | −.05 | .05 | .14* | .11+ | .28*** | .40*** | −.23*** | .04 | −.01 | .15* | .28*** | .27*** | .32*** | – | −.18** | 0.19 | 0.22 |

| 16. Grades W3 | .05 | −.01 | .01 | −.07 | −.12* | −.20** | −.04 | −.46*** | −.11+ | −.07 | −.07 | .20***- | −.23*** | −.25*** | −.18** | – | 5.00 | 1.88 |

| M | 2.29 | 2.72 | 2.48 | 2.81 | 2.80 | 0.71 | 0.23 | 4.42 | 2.39 | 2.77 | 2.27 | 2.46 | 2.65 | 0.63 | 0.19 | 5.00 | – | – |

| SD | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.73 | 0.46 | 0.23 | 2.03 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.22 | 1.88 | – | – |

Descriptive statistics and correlations above the diagonal are for father–adolescent dyads, below the diagonal are for mother–adolescent dyads, and on the diagonal are correlations between mothers and fathers for variables that were assessed separately for them. W2 Wave 2, W3 Wave 3

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

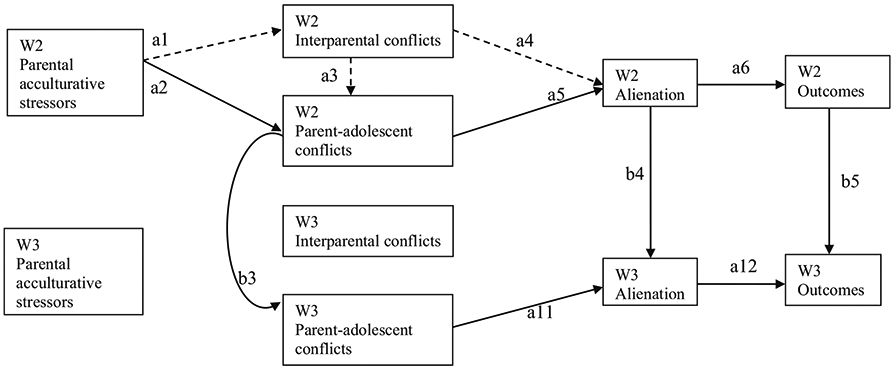

Analyses of the Path Model

The fit indices for the four models are displayed in Table 2, revealing good model fit. All parameter estimates of concurrent paths (a paths) and stability paths (b paths) are presented in Table 2. Parameter estimates of cross-lagged paths (c and d paths) are summarized in the text only. Pattern of results are generally similar across the two types of acculturative stressors and across the three measures of adolescent adjustment. Hence, while we present nuanced results in the tables, we focus on the general patterns in the text. We also summarize the key results in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Linking parental acculturative stressors, family conflicts, alienation, and adolescent adjustment

| Pathway/variable | Perpetual foreigner stereotype |

Bicultural management difficulty |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: F–A |

Model 2: M–A |

Model 3: F–A |

Model 4: M–A |

|||||

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| a1: Stress W2 → Marital conf W2 | .10 | .07 | .15** | .06 | .10+ | .06 | .15* | .06 |

| a2: Stress W2 → Parent–child conf W2 | .19*** | .06 | .16** | .06 | 20*** | .06 | .07 | .06 |

| a3: Marital conf W2 → Parent–child conf W2 | .19*** | .05 | .31*** | .05 | .19*** | .05 | .31*** | .05 |

| a4: Marital conf W2 → Alienation W2 | .30*** | .05 | .23*** | .05 | .30*** | .05 | .23*** | .05 |

| a5: Parent–child conf W2 → Alienation W2 | .35*** | .05 | .43*** | .05 | .35*** | .05 | .43*** | .05 |

| a6a: Alienation W2 → Depr W2 | .47*** | .05 | .47*** | .05 | .47*** | .05 | .47*** | .05 |

| a6b: Alienation W2 → Delq W2 | .27*** | .07 | .26*** | .07 | .27*** | .07 | .26*** | .07 |

| a6c: Alienation W2 → GPA W2 | .22*** | .06 | .23*** | .06 | .22*** | .06 | .23*** | .06 |

| a7: Stress W3 → Marital conf W3 | .05 | .07 | −.02 | .06 | −.09 | .06 | .01 | .06 |

| a8: Stress W3 → Parent–child conf W3 | .14 | .10 | .04 | .08 | .19* | .08 | .03 | .06 |

| a9: Marital conf W3 → Parent–child conf W3 | .24*** | .07 | .22*** | .07 | .27*** | .07 | .23*** | .07 |

| a10: Marital conf W3 → Alienation W3 | .10 | .07 | .09+ | .06 | .10+ | .07 | .09+ | .06 |

| a11: Parent–child conf W3 → Alienation W3 | .34*** | .06 | .46*** | .06 | .34*** | .06 | .46*** | .06 |

| a12a: Alienation W3 → Depr W3 | .36*** | .06 | .36*** | .06 | .36*** | .05 | .36*** | .06 |

| a12b: Alienation W3 → Delq W3 | .22*** | .06 | .22*** | .06 | .22*** | .06 | .22*** | .06 |

| a12c: Alienation W3 → GPA W3 | .15* | .07 | .15* | .07 | .15* | .07 | .15* | .07 |

| b1: Stress W2 → Stress W3 | .49*** | .06 | .41*** | .06 | .34*** | .08 | .53*** | .06 |

| b2: Marital conf W2 → Marital conf W3 | .53*** | .06 | .53*** | .06 | .54*** | .06 | .54*** | .06 |

| b3: Parent–child conf W2 → Parent–child conf W3 | .42*** | .06 | .45*** | .06 | .42*** | .06 | .46*** | .06 |

| b4: Alienation W2 → Alienation W3 | .41*** | .07 | .37*** | .06 | .41*** | .07 | .37*** | .06 |

| b5a: Depr W3 → Depr W3 | .41*** | .06 | .42*** | .06 | .41*** | .06 | .42 | .06 |

| b5b: Delq W3 → Delq W3 | .42*** | .08 | .42*** | .08 | .42*** | .08 | .42*** | .08 |

| b5c: GPA W3 → GPA W3 | .44*** | .06 | .42*** | .06 | .44*** | .06 | .42*** | .06 |

| Model fit | χ2(64) =102.095, p = .002 CFI = .965 RMSEA = .041 SRMR = .037 |

χ2(64) =94.398, p = .008 CFI = .974 RMSEA = .037 SRMR = .038 |

χ2(64) =89.345, p = .020 CFI = .974 RMSEA = .034 SRMR = .037 |

χ2(64) = 91.298, p = .014 CFI = .976 RMSEA = .035 SRMR = .040 |

||||

F–A father–adolescent, M–A mother–adolescent, Stress acculturative stressor, conf conflict, Depr depressive symptoms, Delq delinquent behaviors, GPA academic performance, W2 Wave 2, W3 Wave 3, SE standard error, CFI comparative fit index, RMSEA root-mean-square error of approximation, SRMR standardized root mean square

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Fig. 3.

Key significant indirect pathways linking parental acculturative stressors and adolescent outcomes. Note: Solid lines represent paths involved in indirect pathways for both mother–adolescent and father–adolescent dyads. Dashed lines (a1, a3, and a4 paths) represent paths involved in indirect pathways for mother–adolescent dyads only. An apparent difference between mother–adolescent dyads and father–adolescent dyads was that indirect pathways for mother–adolescent (but not father–adolescent) dyads involved interparental conflicts

Direct Paths

There was moderate stability for all focal variables across waves. The general pattern of concurrent relations (a paths) were consistent with our hypotheses. For the relation between acculturative stressors and family conflicts, at Wave 2, parental acculturative stressors positively related to interparental conflict only for mothers (a1 paths), whereas parental acculturative stressors generally linked to higher levels of parent–child conflict for both mothers and fathers (a2 paths). Interparental conflict was positively related to parent–child conflict at both waves (a3 and a9 paths). Both types of conflict were each associated with a stronger sense of parent–child alienation (a4, a5, and a11 paths). Ultimately, a stronger sense of alienation was related to more adolescent depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors and lower academic performance at both waves (a6 and a12 paths).

The cross-lagged paths (c paths) did not emerge as significant, despite the significant longitudinal zero-order correlations between distinct constructs in the model. This suggests that the longitudinal associations among study variables may be mediated by the concurrent and stability paths. Testing for indirect effects indicated that this was precisely the case. For example, the longitudinal association between parent–child alienation at Wave 2 and adolescent depressive symptoms at Wave 3 was mediated by adolescent depressive symptoms at Wave 2, β = .20, SE = .04, p = .00, and parent–child alienation at Wave 3, β = .13, SE = .03, p = .00. Tests of alternative cross-lagged paths demonstrated only one significant path: Adolescent depressive symptoms at Wave 2 were related to adolescents’ sense of alienation at Wave 3 (d6 paths), β = .13, SE = .05, p = .01 for father–adolescent dyads, and β = .11, SE = .05, p = .02, for mother–adolescent dyads.

Indirect Effects from Parental Acculturative Stressors to Adolescent Adjustment

All potential indirect effects from acculturative stressors to adolescent outcomes were tested, with significant indirect effects shown in Table 3. Figure 3 delineates the pathways of the key significant indirect effects. Consistent with our main hypotheses, both concurrent and longitudinal indirect pathways were found from parental acculturative stressors to adolescent development outcomes through interparental conflict, parent–child conflict and parent–child alienation. Longitudinal indirect effects were found only through concurrent and stability pathways, which is not surprising, because the cross-lagged paths were mediated by such paths. Consistent with our second hypothesis, patterns of indirect pathways are different for father–adolescent and mother–adolescent dyads.

Table 3.

Indirect effects from parental acculturative stress to adolescent adjustment

| Indirect paths | Perpetual foreigner stereotype |

Bicultural management difficulty |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: F–A |

Model 2: M–A |

Model 3: F–A |

Model 4: M–A |

|||||

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → Alien W2 → Depr W2 | .016* | .007 | .016* | .007 | ||||

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → Alien W2 → Delq W2 | .009* | .004 | .009* | .005 | ||||

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → Alien W2 → GPA W2 | .008* | .004 | .008* | .004 | ||||

| Stress W2 → P-Ccf W2 → Alien W2 → Depr W2 | .031** | .011 | .033* | .013 | .032** | .011 | ||

| Stress W2 → P-Ccf W2 → Alien W2 → Delq W2 | .018* | .008 | .018* | .009 | .018* | .008 | ||

| Stress W2 → P-Ccf W2 → Alien W2 → GPA W2 | .015* | .007 | .016* | .007 | .015* | .006 | ||

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → P-Ccf W2 → Alien W2 → Depr W2 | .009* | .004 | .010* | .004 | ||||

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → P-Ccf W2 → Alien W2 → GPA W2 | .004* | .002 | ||||||

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → Alien W2 → Depr W2 → Depr W3 | .007* | .003 | .007* | .003 | ||||

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → Alien W2 → Delq W2 → Delq W3 | .004* | .002 | .004* | .002 | ||||

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → Alien W2 → GPA W2 → GPA W3 | .003* | .002 | .003* | .002 | ||||

| Stress W2 → P-Ccf W2 → Alien W2 → Depr W2 → Depr W3 | .013* | .005 | .014* | .006 | .013** | .005 | .013** | .005 |

| Stress W2 → P-Ccf W2 → Alien W2 → Delq W2 → Delq W3 | .007* | .004 | .008* | .004 | .008* | .003 | ||

| Stress W2 → P-Ccf W2 → Alien W2 → GPA W2 → GPA W3 | .006* | .003 | .007* | .003 | .007* | .003 | ||

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → Alien W2 → Alien W3 → Depr W3 | .004* | .002 | .005* | .003 | ||||

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → Alien W2 → Alien W3 → Delq W3 | .003* | .001 | .003* | .001 | ||||

| Stress W2 → P-Ccf W2 → Alien W2 → Alien W3 → Depr W3 | .010* | .004 | .009* | .004 | .010** | .004 | ||

| Stress W2 → P-Ccf W2 → Alien W2 → Alien W3 → Delq W3 | .006* | .003 | .006* | .003 | .006* | .003 | ||

| Stress W2 → P-Ccf W2 → P-Ccf W3 → Alien W3 → Depr W3 | .010* | .004 | .012* | .005 | .010** | .004 | ||

| Stress W2 → P-Ccf W2 → P-Ccf W3 → Alien W3 → Delq W3 | .006* | .003 | .007* | .004 | .006* | .003 | ||

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → P-Ccf W2 → Alien W2 → Depr W2 → Depr W3 | .004* | .002 | .003* | .001 | ||||

| Stress W2 → Stress W3 → P-Ccf W3 → Alien W3 → Depr W3 | .008* | .004 | ||||||

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → P-Ccf W2 → Alien W2 → Alien W3 → Depr W3 | .003* | .001 | ||||||

| Stress W2 → Mrcf W2 → P-Ccf W2 → P-Ccf W3 → Alien W3 → Depr W3 | .003* | .002 | .004* | .002 | ||||

| Stress W3 → P-Ccf W3 → Alien W3 → Depr W3 | .023** | .011 | ||||||

F–A father–adolescent, M–A mother–adolescent, Stress acculturative stressor, Mrcf marital conflict, P-Ccf parent–child conflict, Alien parent–child alienation, Depr depressive symptoms, Delq delinquent behaviors, GPA academic performance, W2 Wave 2, W3 Wave 3, SE standard error

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Specifically, for father–adolescent dyads, all significant indirect pathways from parental acculturative stressors to adolescent outcomes were through parent–child conflict and alienation (e.g., parental acculturative stressors W2 → parent–child conflict W2 → Alienation W2 → Outcomes W2; parental acculturative stressors W2 → parent–child conflict W2 → Alienation W2 → Alienation W3 → Outcomes W3). For mother–adolescent dyads, there were three patterns of indirect pathways from parental acculturative stressors to adolescent outcomes. First, there were significant indirect pathways through parent–child conflict to alienation, overlapping the indirect pathways shown for father–adolescent dyads. Second, there were significant indirect pathways through interparental conflict to alienation (e.g., parental acculturative stressors W2 → interparental conflict W2 → Alienation W2 → Alienation W3 → Outcomes W3). Third, there were significant indirect pathways through interparental conflict to parent–child conflict to alienation (e.g., maternal bicultural difficulty W2 → interparental conflict W2 → parent–child conflict W2 → Alienation W2 → Outcome W2; maternal bicultural difficulty W2 → interparental conflict W2 → parent–child conflict W2 → parent–child conflict W3 → Alienation W3 → Outcome W3).

Parent Gender Differences

Separately examining the models for father–adolescent and mother–adolescent dyads, the relations between acculturative stressors to marital conflicts were significant for mother–adolescent dyads (but not father–adolescent dyads) at Wave 2; the relation between parental bicultural management difficulty and parent–child conflict was significant for only father–adolescent dyads (but not mother–adolescent dyads) at both waves. However, when the magnitudes of these paths were compared, only the link between parental bicultural management difficulty and parent–child conflict at Wave 3 was significantly different across parental gender: the path from bicultural management difficulty to parent–child conflict was stronger for father–adolescent dyads than for mother–adolescent dyads (Path a8, χ2(1) = 4.42, p < .05).

Discussion

Perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty are two salient acculturative stressors for Asian Americans (Armenta et al. 2013; Huynh et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2014a). Yet, it is unclear whether parental experiences of these two acculturative stressors indirectly affect adolescent adjustment through family processes. This is partly because prior studies on these acculturative stressors mainly focus on individuals rather than families. Guided by the family stress model, the current study fills in this gap by including mothers, fathers, and their adolescent children in our study design. We demonstrated that acculturative stressors experienced by Chinese American parents were related to a higher level of parent–child conflicts, either indirectly through interparental conflicts, or directly. Subsequently, both interparental and parent–child conflicts were positively linked to adolescents’ sense of alienation toward their parents, which was, in turn, related to more adolescent depressive symptoms, more delinquent behaviors, and lower academic performance. Moreover, the indirect family processes were different for father–adolescent and mother–adolescent dyads: whereas maternal acculturative stressors were related to adolescent adjustment through both interparental and parent–child relationships, paternal acculturative stressors were linked to adolescent adjustment only through the parent–child relationship.

Parental Acculturative Stressors and Adolescent Adjustment

The present study is among the first to demonstrate indirect links from parental experiences of perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty to adolescent adjustment. Previous literature on Asian American families has largely ignored these two acculturative stressors. A limited number of extant studies on these two acculturative stressors examined only their association with adult adjustment—for instance, psychological wellbeing (Armenta et al. 2013; Huynh et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2014a). Our findings indicate that parental experiences of perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty can also be regarded as family stressors that may influence adolescent adjustment through family processes. Note that our study statistically controlled for family socioeconomic factors (i.e., economic stress, parental employment, and parental educational level), which usually intertwine with other acculturative stressors during the acculturation process of ethnic minorities (Garcia Coll et al. 1996; Xia et al. 2013). Thus, our findings point to the unique effect of perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty, above and beyond the effects of more widely-studied socioeconomic factors.

In practice, it would be valuable to reduce the incidence of these two acculturative stressors to improve adjustment in ethnic minority families. Future studies could explore the antecedents of perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty to inform interventions targeting these stressors. As an example, Kim et al. (2011) showed that individuals with low levels of English proficiency reported more experiences of perpetual foreigner stereotype. This suggests that programs promoting English language proficiency may help decrease ethnic minorities’ experiences of perpetual foreigner stereotype. Future work can also examine moderators that may mitigate the effect of these acculturative stressors. For example, coping strategies may be a potential moderator, as they have been shown to moderate the relationship between other acculturative stressors (e.g., discrimination) and individual adjustment (Wei et al. 2008).

Previous studies have employed the family stress model to understand the association between parent–child acculturation gap and adolescent development in Asian American families (Lim et al. 2008; Ying and Han 2007). Moving beyond these previous studies, which examined only the mediating role of parent–child relationships (Chen et al. 2014; Farver et al. 2002; Lim et al. 2008; Ying and Han 2007), the current study provides a more nuanced picture of the family processes linking acculturative stressors and adolescent adjustment by demonstrating the mediating role of both parent–child relationships and interparental relationships. In particular, our study underlines the role of interparental conflict in linking acculturative stressors to parent–child conflict and alienation, which ultimately relate to adolescent adjustment. In the current study, interparental conflict was reported by the child, and therefore may point toward more overt instances of conflict. However, whether or not interparental conflict is overt enough to be noticed by children (in other words, regardless of whether interparental conflict is reported by parents or children), it may relate to parent–child relationship and adolescent adjustment (Gerard et al. 2006).

The current study has also moved beyond the extant literature in that we used a longitudinal design instead of a cross-sectional design, which has been more common (Chen et al. 2014; Costigan and Dokis 2006; Farver et al. 2002). We assessed all the study variables at both high school and emerging adulthood. In this way, we provided evidence of indirect effects from parental acculturative stressors to their children’s adjustment, not only concurrently, but also longitudinally from high school to emerging adulthood. Longitudinal indirect pathways generally involved stability of outcome variables or mediators. For example, parental acculturative stressors were related to a higher level of parent–child conflict, which then linked to adolescents’ stronger sense of alienation from parents during high school. Adolescents’ sense of alienation during high school lasted into emerging adulthood, where it related to their depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors in emerging adulthood. These findings suggest that an intervention aimed at improving the parent–child relationship in adolescence may have a lasting effect on adolescents’ adjustment in later life.

These results are consistent with previous findings demonstrating that parent–child relationship quality in adolescence can predict adolescents’ later adjustment (e.g., depressive symptoms and conduct problems) in young adulthood (Klahr et al. 2011; Raudino et al. 2013). Although parental influence on youth may gradually decrease during adolescence and emerging adulthood, it still may play important roles in youth adjustment (Klahr et al. 2011; Raudino et al. 2013). This may be particularly true for Asian American immigrant families due to two reasons. First, there is a traditional emphasis of family values and connectedness in Asian cultures (Fuligni et al. 1999; Xia et al. 2013). Second, during these developmental periods, youth of these families may go through increasing exploration of ethnic identity (Hou et al. 2015; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014) and thus may particularly need a sense of connectedness with parents, who are the primary agents of ethnic socialization (Hughes et al. 2006). In addition, we found that adolescents’ depressive symptoms during high school were associated with parent–child alienation in emerging adulthood. This finding is consistent with prior studies suggesting that the relation between adolescent adjustment and parent–child relationships may be bidirectional (Elkins et al. 2014; Sameroff and MacKenzie 2003).

Parental Gender Differences

We found parental gender differences in the relationship between acculturative stressors and family conflicts. Consistent with our hypotheses, acculturative stressors were related to a higher level of interparental conflict only for mothers. When confronted with stress, women are more likely to express their negative emotions in their interactions with intimate partners, possibly as a way to elicit support from them (Schulz et al. 2004; Story and Repetti 2006). In addition, parental bicultural management difficulty was more strongly associated with parent–child relationship for father–adolescent dyads than for mother–adolescent dyads. This finding seems to be consistent with the fathering-vulnerability hypothesis (Cummings et al. 2004), which suggests that external family stressors may have a greater influence on the father–child relationship compared to the mother–child relationship. Nevertheless, it should be noted that, although the direct effect from maternal bicultural management difficulty to mother–child conflicts was not significant, maternal bicultural management difficulty did indirectly relate to mother–child relationship through marital conflicts. As a result of these parental gender differences in the associations between acculturative stressors and family relationships, the indirect family processes linking parental acculturative stressors and adolescent adjustment involve only the parent–child relationship for father–adolescent dyads, whereas they involve both interparental and parent–child relationships for mother–adolescent dyads.

By including both mothers and fathers in the study design, and by examining both parent–child and interparental relationships, our study suggests that maternal acculturative stressors are as influential as paternal acculturative stressors on adolescent outcomes. These findings are consistent with most prior work emphasizing the importance of both maternal and paternal roles in child development (Connell and Goodman 2002; Wang and Kenny 2014). But our findings are in contrast to previous studies that tested only parent–child relationship as the mediator between acculturative stressors and adolescent outcomes (Chen et al. 2014; Lim et al. 2008; Schofield et al. 2008; Ying and Han 2007). These prior studies have often come to the plausible conclusion that paternal (vs. maternal) acculturative stressors have a stronger indirect influence on adolescent outcomes, as they have often found a stronger association between acculturative stress and the parent–child relationship for father–adolescent dyads (e.g., Schofield et al. 2008). The current study provides a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the roles maternal and paternal acculturative stressors play in adolescent development.

Limitations

There are several limitations of the current study. First, this is a correlational study, and we cannot ascertain causal relationships, although we used two waves of longitudinal data to test temporal relations (a method that provides additional support for the ordering of model constructs). Second, the two acculturative stressors examined in the current study are assessed using subjective, indirect measures. It would be helpful for future studies to include a more direct measure of acculturative stress, such as a physiological measure, to assess the amount of stress the parents actually feel. Third, factors such as generational status may moderate the association between acculturative stressors and adjustment (Yip et al. 2008). However, our data do not allow us to test this possibility, because we had such a small number of U.S.-born parents. Future studies could include samples with a more even distribution of first-, second-, and third-generation individuals to examine the extent to which our results may vary across generational status.

Finally, the generalizability of our findings to other Chinese American samples needs to be tested. Our participants come from a dense area of Chinese Americans in Northern California. Community characteristics such as ethnic concentration may influence the effects of acculturative stressors on individual adjustment (White et al. 2014). Future studies should include samples from multiple different communities and assess specific community factors, such as ethnic density, to gain a more accurate understanding of community influences on the effect of acculturative stressors. Moreover, most of the parents in our study hailed from south China with Cantonese as their native language. However, in other parts of the United States, there are Chinese Americans who hail from Taiwan or other parts of China where Mandarin is spoken. Different parts of China have distinct subcultures. People from such different cultures may vary in their experiences of, and reaction to, acculturative stressors (Xia et al. 2013). Hence, future studies should include Chinese American samples from different cultural backgrounds to examine whether and how subculture of origin may contribute to the within-group variations among Chinese Americans in terms of their acculturation experiences.

Conclusions

The present study highlights perpetual foreigner stereotype and bicultural management difficulty as two important acculturative stressors experienced by Asian American parents that indirectly relate to adolescent adjustment through family processes. Our study suggests that the family stress model may be a useful theoretical framework in understanding how parental acculturative stressors relate to adolescent outcomes. The findings from the current study also demonstrate that there is an advantage to including both interparental and parent–child relationships in order to derive a more comprehensive understanding of family processes linking parental acculturative stressors and adolescent outcomes, as well as a more nuanced portrait of parental gender differences in the indirect pathways. The results suggest that it may be most effective for interventions aimed at reducing the effects of parental acculturative stressors on adolescent adjustment to intervene both interparental and parent–child relationships, particularly for mother–adolescent dyads.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided through awards to Su Yeong Kim from (1) Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development 5R03HD051629-02 (2) Office of the Vice President for Research Grant/Special Research Grant from the University of Texas at Austin (3) Jacobs Foundation Young Investigator Grant (4) American Psychological Association Office of Ethnic Minority Affairs, Promoting Psychological Research and Training on Health Disparities Issues at Ethnic Minority Serving Institutions Grant (5) American Psychological Foundation/Council of Graduate Departments of Psychology, Ruth G. and Joseph D. Matarazzo Grant (6) California Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, Extended Education Fund (7) American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, Massachusetts Avenue Building Assets Fund, and (8) Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development 5R24HD042849-14 Grant awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin.

Biography

Yang Hou is a doctoral student in the Department of Human Development and Family Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin. Her research interests focus on how factors in family, school, and socio-cultural contexts relate to adolescents’ socio-emotional, behavioral, and academic development.

Su Yeong Kim is an Associate Professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin. She received her Ph.D. in Human Development from the University of California, Davis. Her research interests include the role of cultural and family contexts that shape the development of adolescents in immigrant and minority families in the U.S.

Yijie Wang is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Psychology at Fordham University. Her research investigates how adolescent adjustment is influenced by cultural and racial/ethnic contexts across developmental settings (e.g., family, peer, school).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla L (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Armenta BE, Lee RM, Pituc ST, Jung K-R, Park IJ, Soto JA, & Schwartz SJ (2013). Where are you from? A validation of the Foreigner Objectification Scale and the psychological correlates of foreigner objectification among Asian Americans and Latinos. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19, 131–142. doi: 10.1037/a0031547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, & Greenberg MT (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16, 427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martínez V, & Haritatos J (2005). Bicultural identity integration (BII): Components and psychosocial antecedents. Journal of Personality, 73, 1015–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Kim SY (2009). Intergenerational experiences of discrimination in Chinese American families: Influences of socialization and stress. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 862–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford K, Vaughn LB, & Barber BK (2008). When there is conflict: Interparental conflict, parent–child conflict, and youth problem behaviors. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 780–805. doi: 10.1177/0192513X07308043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Vaeth PAC, & Harris TR (2007). Acculturation stress, drinking, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic couples in the US. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22, 1431–1447. doi: 10.1177/0886260507305568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK (2001). Extending research on the consequences of parenting style for Chinese Americans and European Americans. Child Development, 72, 1832–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CS, Leung CY, & Zhou N (2013). Understanding “tiger parenting” through the perceptions of Chinese immigrant mothers: Can Chinese and US parenting coexist? Asian American Journal of Psychology, 4, 30–40. doi: 10.1037/a0031217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SH, Hua M, Zhou Q, Tao A, Lee EH, Ly J, & Main A (2014). Parent–child cultural orientations and child adjustment in Chinese American immigrant families. Developmental Psychology, 50, 189–201. doi: 10.1037/a0032473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, He M, & Harachi TW (2008). Intergenerational cultural dissonance, parent–child conflict and bonding, and youth problem behaviors among Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 85–96. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9217-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, & Whitbeck LB (1992). A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development, 63, 526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, & Donnellan MB (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, & Simons RL (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development, 65, 541–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, & Brody GH (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38, 179–193. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, & Goodman SH (2002). The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 746–773. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan CL, & Dokis DP (2006). Relations between parent–child acculturation differences and adjustment within immigrant Chinese families. Child Development, 77, 1252–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, & Raymond J (2004). Fathers in family context: Effects of marital quality and marital conflict In Lamb ME (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (4th ed., pp. 196–221). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins SR, Fite PJ, Moore TM, Lochman JE, & Wells KC (2014). Bidirectional effects of parenting and youth substance use during the transition to middle and high school. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28, 475–486. doi: 10.1037/a0036824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, & Elmore-Staton L (2004). The link between marital conflict and child adjustment: Parent–child conflict and perceived attachments as mediators, potentiators, and mitigators of risk. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 631–648. doi: 10.1017/0S0954579404004705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, & Burman B (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent–child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 118, 108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farver JAM, Narang SK, & Bhadha BR (2002). East meets West: Ethnic identity, acculturation, and conflict in Asian Indian families. Journal of Family Psychology, 16, 338–350. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.16.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, & Lam M (1999). Attitudes towards family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European Backgrounds. Child Development, 70, 1030–1044. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia HV, & McAdoo HP (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard JM, Krishnakumar A, & Buehler C (2006). Marital conflict, parent–child relations, and youth maladjustment: A longitudinal investigation of spillover effects. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 951–975. doi: 10.1177/0192513X05286020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman JM, & Liang B (2008). Discrimination distress among Chinese American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9215-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Seid M, & Fincham FD (1992). Assessing marital conflict from the child’s perspective: The Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale. Child Development, 63, 558–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Kim SY, Wang Y, Shen Y, & Orozco-Lapray D (2015). Longitudinal reciprocal relationships between discrimination and ethnic affect or depressive symptoms among Chinese American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 2110–2121. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0300-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 747. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh Q-L, Devos T, & Smalarz L (2011). Perpetual foreigner in one’s own land: Potential implications for identity and psychological adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30, 133–162. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2011.30.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang LP, & Cookston JT (2009). A longitudinal study of family obligation and depressive symptoms among Chinese American adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 396–404. doi: 10.1037/a0015814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BS, & Omizo MM (2005). Asian and European American cultural values, collective self-esteem, acculturative stress, cognitive flexibility, and general self-efficacy among Asian American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 412–419. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Shen Y, Huang X, Wang Y, & Orozco-Lapray D (2014a). Chinese American parents’ acculturation and enculturation, bicultural management difficulty, depressive symptoms, and parenting. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 5, 298–306. doi: 10.1037/a0035929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Wang Y, Deng S, Alvarez R, & Li J (2011). Accent, perpetual foreigner stereotype, and perceived discrimination as indirect links between English proficiency and depressive symptoms in Chinese American adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 47, 289–301. doi: 10.1037/a0020712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Wang Y, Weaver SR, Shen Y, Wu-Seibold N, & Liu CH (2014b). Measurement equivalence of the language-brokering scale for Chinese American adolescents and their parents. Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 180–192. doi: 10.1037/a0036030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klahr AM, McGue M, Iacono WG, & Burt SA (2011). The association between parent–child conflict and adolescent conduct problems over time: Results from a longitudinal adoption study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120, 46–56. doi: 10.1037/a0021350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak K (2003). Adolescents and their parents: A review of intergenerational family relations for immigrant and non-immigrant families. Human Development, 46, 115–136. doi: 10.1159/000068581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T, Coleman HL, & Gerton J (1993). Psychological impact of biculturalism: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 395–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau A, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Wood PA, & Hough RL (2005). The acculturation gap-distress hypothesis among high-risk Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 367–375. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le TN, & Stockdale G (2005). Individualism, collectivism, and delinquency in Asian American adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 681–691. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Choe J, Kim G, & Ngo V (2000). Construction of the Asian American Family Conflicts Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 211–222. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.47.2.211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Wong N-WA, & Alvarez AN (2009). The model minority and the perpetual foreigner: Stereotypes of Asian Americans In Tewari N & Alvarez AN (Eds.), Asian American psychology: Current perspectives (pp. 69–84). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Lim S-L, Yeh M, Liang J, Lau AS, & McCabe K (2008). Acculturation gap, intergenerational conflict, parenting style, and youth distress in immigrant Chinese American families. Marriage & Family Review, 45, 84–106. doi: 10.1080/01494920802537530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD (1997). Mean and covariance structures (MACS) analyses of cross-cultural data: Practical and theoretical issues. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 32, 53–76. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3201_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lueck K, & Wilson M (2010). Acculturative stress in Asian immigrants: The impact of social and linguistic factors. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34, 47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, & Austin JT (2000). Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 201–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, & Kitayama S (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Millsap RE, & Yun-Tein J (2004). Assessing factorial invariance in ordered-categorical measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 479–515. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3903_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Benner AD, Tan CS, & Kim SY (2009). Family economic stress and academic well-being among Chinese-American youth: The influence of adolescents’ perceptions of economic strain. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 279–290. doi: 10.1037/a0015403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2015). Mplus user’s guide, 7th edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Burrow AL, Fuller-Rowell TE, Ja NM, & Sue DW (2013). Racial microaggressions and daily well-being among Asian Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 188–199. doi: 10.1037/a0031736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1991). The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20, 149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudino A, Fergusson DM, & Horwood LJ (2013). The quality of parent/child relationships in adolescence is associated with poor adult psychosocial adjustment. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese-Weber M, & Hesson-McInnis M (2008). The children’s perception of interparental conflict scale: Comparing factor structures between developmental periods. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 88, 1008–1023. doi: 10.1177/0013164408318765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, & MacKenzie MJ (2003). Research strategies for capturing transactional models of development: The limits of the possible. Development and Psychopathology, 15, 613–640. doi: 10.1017/S0954579403000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield TJ, Parke RD, Kim Y, & Coltrane S (2008). Bridging the acculturation gap: parent–child relationship quality as a moderator in Mexican American families. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1190–1194. doi: 10.1037/a0012529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz MS, Cowan PA, Pape Cowan C, & Brennan RT (2004). Coming home upset: Gender, marital satisfaction, and the daily spillover of workday experience into couple interactions. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 250–263. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, & Morris AS (2001). Adolescent development. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 2, 55–87. doi: 10.1891/194589501787383444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]