Abstract

As part of its core work, the WHO generates, translates and disseminates knowledge, including through guideline development. In recent years, substantial work has been undertaken to revise the Evidence to Decision framework in order to fully integrate inter alia human rights. This paper describes an innovative methodological approach taken by the authors to inform law and policy recommendations for the forthcoming third edition of the Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. The methodology described here effectively integrates human rights protection and enjoyment as part of health outcomes and analysis, ensuring that subsequent recommendations are consistent with international human rights standards. This will allow guideline users to make informed decisions on interventions, including legal and policy reform, to fulfil relevant human rights including the right to health.

Keywords: maternal health, other study design

Summary box.

Guideline development should integrate the balance of health benefits and harms, human rights and sociocultural acceptability, health equity, equality and non-discrimination, societal implications, financial and economic considerations and feasibility and health system considerations.

This paper presents a methodological, technical advance on the effective integration of human rights with appropriate evidential weight in guideline development.

Appropriate, interdisciplinary approaches can ensure the effective integration of human rights in guideline development.

Introduction

As part of its core functions, the WHO generates, translates and disseminates knowledge. One way in which it does this, is through its normative work related to guideline development targeting programmatic individuals, including healthcare providers, implementers and managers at national and subnational levels, national and subnational policy-makers and other organisations involved in the planning and management of service delivery.1

Such guidelines are developed according to a well-established process1 using an Evidence-to-Decision (EtD) framework.2 In recent years, substantial work has been undertaken to revise the EtD framework to incorporate further domains and integrate the balance of health benefits and harms, human rights and sociocultural acceptability, health equity, equality and non-discrimination, societal implications, financial and economic considerations, and feasibility and health system considerations.3 This INTEGRATE framework appreciates the fact that some interventions may be complex and can have multiple components interacting synergistically or dissynergistically, may be non-linear in their effects, and are often context dependent.4 Such complex interventions often interact with one another, such that outcomes related to one individual or community may be dependent on others, and may be impacted positively or negatively by the people, institutions and resources that are arranged together within the larger system in which they are implemented.4 Laws and policy interventions related to the regulation of abortion are an example of such complex interventions operating within complex systems. Abortion laws and policies often ‘include complex behaviors in the delivery and receipt of the intervention; … target different groups and levels; … (and) involve [] health and non-health outcomes’.1

This paper describes an innovative methodological approach taken by the authors to inform draft law and policy recommendations for the forthcoming third edition of Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems (‘the Guidelines’). The approach was developed after six law and policy interventions (mandatory waiting periods, third-party authorisation, gestational limits, criminalisation, provider restrictions and ‘conscientious objection’ also known as ‘conscientious refusal’) were identified by individuals participating in a technical consultation and scoping meeting, in preparation for planning and development of the update to the Guidelines. Currently, there are no formal WHO recommendations related to these interventions; however, they have been described in the second edition of the Guidelines as regulatory and policy barriers that may impact access to and timely provision of safe abortion care.5 This approach to generating EtD frameworks, in which human rights standards have been treated as evidence, reflects a commitment to the full integration and evidential application of human rights in Guideline development.

The realisation of human rights applicable to abortion-related interventions is not a research area that readily lends itself to randomised controlled trials or comparative observational studies, but instead often includes studies without comparisons. Assessing the body of such evidence can be difficult, especially when using tools such as Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE).1 The methodology described here effectively integrates human rights protection and enjoyment as part of health outcomes and analysis, while considering several important factors and their potential interactions. This is in line with the WHO’s norms and values, and thus underpins integrated evidence for application within an EtD framework. This methodology ensures that subsequent recommendations are consistent with international human rights standards, so that guideline users can make informed decisions on interventions, including law and policy reform, to fulfil relevant human rights including the right to health.

Our approach

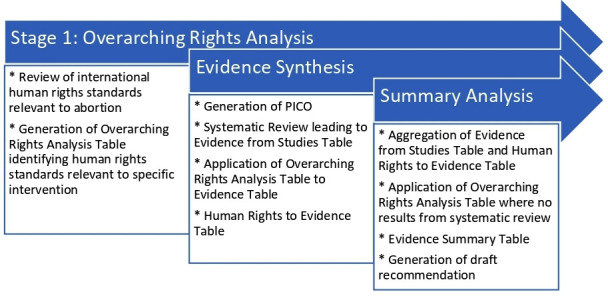

Recommendations are formulated and finalised by a Guideline Development Group: a group of external experts convened by WHO, whose central task is to develop evidence-based recommendations. Through an iterative, principles-based approach, we developed a three-stage process to retrieve and synthesise evidence that integrates both public health and legal methodological approaches in order to generate evidence and inform draft recommendations. The stages included: (i) the development of an ‘abstract’ human rights analysis relating to the intervention under consideration (overarching rights analysis), (ii) the retrieval and synthesis of the existing evidence, which included conducting a systematic review and applying a rights analysis to the evidence within the systematic review (evidence synthesis) and (iii) a summary analysis combining the previous stages (summary analysis) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Outline of methodology. PICO: Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome.

Overarching rights analysis

The first stage involved the development of a clear understanding of the human rights norms relevant to the intervention in question. From this, summary statements of states’ human rights obligations that might be implicated (positively or negatively) by the intervention being studied were developed. In line with a legal methodological approach, this entailed a comprehensive review of the human rights standards relevant to abortion access as articulated by United Nations treaty monitoring bodies and special procedures in their general comments, general recommendations, reports, concluding observations and decisions on individual complaints. These compiled standards were then refined into a set of propositions about human rights standards as they apply to comprehensive abortion care. These propositions were presented in a ‘human rights master chart’ reflecting these propositions and the sources from which they were derived. The standards from the human rights master chart that related to the intervention being considered were then identified and brought together into an Overarching Rights Analysis Table, presenting the human rights law evidence for the intervention. This Overarching Rights Analysis Table did not take account of likely balance of health benefits and harms, but instead dealt with human rights law as a standalone item.

Evidence synthesis

The second stage included two elements: systematic review and applied human rights analysis.

Systematic review

A systematic review was undertaken for each of the interventions being considered, in line with standard Guideline development practice.1 Following development of a PICO, a search strategy was drawn up for each of the interventions being studied. We searched the databases PubMed, HeinOnline, and JStor and the search engine Google Scholar, data sources that include both global and regional level data and are appropriate for an analysis engaging international human rights standards. While the latter three are not standard clinical databases, they would include manuscripts focused on law and policy analyses and thus in line with our interventions of interest. We limited our search to papers published in English since 2010, as the second edition of the Guideline included information prior to this point. We included quantitative studies (comparative and non-comparative), qualitative and mixed-methods studies, reports, PhD theses, and economic or legal analyses. Only studies that undertook original data collection or analysis were included. Titles and abstracts were first dual screened for eligibility. Full texts were then reviewed, and inclusion and exclusion criteria applied.

Both health and non-health outcomes were included based on a separate assessment of the literature that went beyond simple linear causal pathways, and considered effects that may be plausibly, while not directly, related to the effects of laws or policies. These included outcomes such as continuation of pregnancy and system costs, as well as outcomes that sought to capture qualitative impacts such as impact on the provider–patient relationship, perceived exposure to interpersonal violence and opportunity costs understood broadly. Data from the included studies were extracted and mapped to the outcomes. Given the diverse range of evidence considered, standard tools for assessing risk of bias or quality were unsuitable,6 and a novel approach that could be uniformly applied across the body of evidence was developed.7 The retrieved evidence was presented in a table entitled Evidence Table. The objective of these tables was to summarise the data related to each outcome for the intervention under consideration.

Studies of all designs (quantitative and qualitative) were reviewed to determine study design, sample size and geographic location. For quantitative studies, point estimates and CIs were included. Quantitative studies were evaluated for precision, directness and magnitude of effect. Footnotes were used throughout the Evidence Tables to indicate these assessments. Qualitative findings were evaluated for adequacy8 and footnotes were used to indicate a concern for adequacy such as situations where the findings were not sufficiently rich and detailed and/or were supported by few studies/participants.

Human rights analysis

The second element of this stage involved applying the human rights standards identified in the overarching rights analysis to the evidence identified through the systematic review in order to develop a rights-based evidential understanding of the findings from the systematic review. The applied human rights analysis was presented in a table entitled Human Rights to Evidence table, and organised by outcome of interest. For both elements of this stage, the effect direction was used to describe whether there was an increase, decrease or no change in the direction7 of the effect of the intervention on the outcome (Evidence Table) or on rights enjoyment (Human Rights to Evidence Table).

Summary analysis

In the final stage, we compiled an Evidence Summary Table where we brought together the evidence garnered from the systematic reviews and the applied rights analysis, as an aggregation of information. Where the retrieval and synthesis of the evidence did not generate any evidence against an outcome, the overarching rights analysis was reviewed for any possible human rights law implication of the intervention relevant to that outcome and the relevant human rights standards constituted the evidence. Where such standards were identified, this was included in the Evidence Summary Table. We then integrated the evidence from both the systematic reviews and international human rights law to inform draft recommendations.

Application of approach

Overarching rights analysis

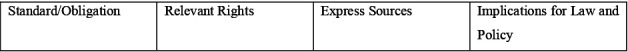

For each intervention, the most relevant human rights standards from the human rights master were identified. This was then made into an overarching rights analysis for the intervention and presented in the Overarching Rights Analysis Table (figure 2). The Overarching Rights Analysis Table focused on standards derived from abortion-specific interpretations, utterances and findings of human rights bodies as applied in an abstracted sense to the intervention being considered. The Overarching Rights Analysis Table sought to capture foreseeable direct, knock-on and ancillary rights implications of the intervention per se. As a matter of human rights law, the ‘abortion specific’ rights standards identified in the Overarching Rights Analysis Table sit alongside and are contextualised by more general human rights standards (eg, the right to a remedy, or the obligation of non-retrogression). They also need to be understood by reference to the general normative and interpretive principles of human rights law as discussed further in ‘Significance and Limitations’ below.

Figure 2.

Overarching rights analysis table.

Evidence synthesis

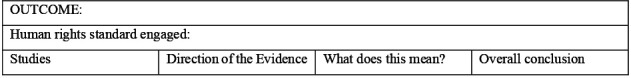

A summary of findings table was prepared for each intervention (figure 3), which summarised the data related to each outcome for the intervention under consideration. To summarise the effect of the intervention, across all study designs, we utilised a previously developed approach and incorporated a visual representation of effect direction.7 The direction of the evidence was illustrated by a symbol which indicated whether, in relation to that particular outcome, the evidence extracted from a study suggested an increase (▲), decrease (⊽) or no change in the outcome (○). These symbols were not linked to the magnitude of the effect. For each outcome, an overall conclusion was formulated encapsulating the key findings from the extracted data, and presented in the final column in the Evidence from Studies table.

Figure 3.

Evidence from studies table.

In the Human Rights to Evidence Table, we applied rights standards identified in the Overarching Rights Analysis Table to the conclusions-per-outcome from the Evidence from Studies Table. For each human rights standard applied, the effect direction was once again used to indicate the impact of the intervention on rights enjoyment, based on the evidence identified through the systematic review.7 These symbols indicated an increased negative relationship with rights enjoyment between the intervention and the outcome (ie, respect, protection, and fulfilment of relevant rights decreases) (▲); unclear/no impact on rights enjoyment between the intervention and the outcome (○); and a decreased negative relationship with rights enjoyment between the intervention and the outcome (ie, respect, protection and fulfilment of relevant rights increases)(⊽). This applied rights analysis allowed for a concrete and grounded analysis of how the interventions being studied impacted on the rights of the relevant population (primarily: pregnant people seeking abortion). From this, an overall conclusion for rights could be drawn, which was presented in the final column of the Human Rights to Evidence table. The general outline and headings for Human Rights to Evidence table are depicted in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Human rights to evidence table

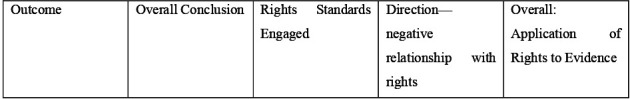

Summary analysis

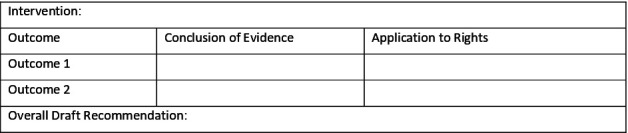

For each intervention, an Evidence Summary Table was created, in which the overall conclusions from the Evidence table and the Human Rights to Evidence table were presented. As noted above, where the systematic review had not generated any evidence on an outcome of interest, the general principles from the Overarching Rights Analysis Table were applied and inserted. The general outline and headings in the Evidence Summary Table are depicted in figure 5.

Figure 5.

Evidence summary table.

In this way, the Evidence Summary Table allowed for the effective synthesis of general principles from international human rights, clinical and qualitative evidence from the systematic review, and applied rights analysis in order to inform draft recommendations that allowed for the effective integration of human rights as evidence in a manner that was informed but not dominated by either legal analysis or clinical evidence.

The significance and limitations of this technical advance

The methodology described in this paper is an innovative approach to synthesising the impact of abortion laws and policies on health and non-health outcomes and rights enjoyment. In its formulation of recommendations and Guidance on sexual and reproductive health, the WHO has always been committed to taking account of rights. This reflects the Constitution of the WHO, the Preamble of which affirms ‘enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health (as) a fundamental right of every human being’.9 Indeed, this was the first articulation of an internationally protected right to health, which has subsequently developed through primary instruments including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 25), and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Article 12). The right to health includes a right to sexual and reproductive health.10 Furthermore, failures in the provision of the highest attainable standard of sexual and reproductive healthcare—including abortion care—have significant direct, ancillary and indirect implications for rights, and a rights-based approach has particular potential for improved abortion care in settings with weak health systems.11 Understanding the implications, limitations and obligations pertaining to international human rights law is, thus, critical to both reflecting and enacting the rights-based nature of healthcare and the maximisation of health outcomes.

Our work advances the integration of human rights and health evidence systematically in guideline development by giving equal weight to human rights evidence. In earlier processes of WHO Guideline development, the methodological approach was to undertake systematic reviews done in the ‘conventional’ manner, that is, dominated by clinical evidence, where study design and outcomes of interest are typically linked to safety and effectiveness, and without an applied human rights analysis.1 Instead, the human rights analysis would ordinarily appear in the text that surrounded a recommendation, and comprise a précis of human rights standards.4 In 2014, WHO systematically reviewed and relied on international human rights laws and treaties in the development of contraceptive guidelines, however, the health and legal evidence were reviewed and considered separately.12 Another important advance to effectively integrating human rights into guideline development came with the revision of the EtD INTEGRATE Framework, which explicitly calls for human rights consideration.2 Our integrated approach to systematically reviewing and considering legal and health evidence in parallel represents an important advance from this earlier work, and a significant contribution to continuing attempts to integrate science and law in social epidemiology13 and in policy making more generally.14 15 Our approach, where clinical evidence and human rights are integrated and weighted equally, can be used broadly to develop Guidelines at international, national or local levels.

This approach does pose challenges and have limitations. There is no one recommended approach to systematically assessing and summarising studies from a diverse array of study designs, including both quantitative and qualitative data, and also legal reviews. Standard tools used to assess risk of bias and quality cannot be uniformly applied across the evidence.7 16 17 As proposed by Thomson et al, we presented a representation of the directionality of the evidence to visually summarise complex data.7 When standardised effect sizes are not possible, this approach may improve clarity and accessibility of the narrative synthesis.7

Second, we limited ourselves to international human rights law as interpreted and applied in the treaty monitoring bodies and special procedures of the United Nations. While there exists a substantial body of regional and national law including treaty provisions, constitutional provisions and case law that is of relevance when a particular guideline or recommendation is being translated into a local law and policy regime (including on safe abortion18), our method was focused on informing general recommendations that draw on internationally binding legal standards in respect of which all states have at least some legally binding obligations, depending on the treaties that they had ratified. Were such an approach to be adopted at a national or regional level, for example, the relevant national and regional human rights standards might also be taken into consideration with potential conflicts being resolved by reference to appropriate conflict of laws principles, including the principle that inconsistent domestic law does not absolve a state of its obligation to comply with its international legal commitments.

Furthermore, international human rights law is iterative and constantly evolving. It is also made up of various sources, with different jurisprudential weights. An express treaty provision19 has a different level of ‘bindingness’ to an interpretation of that provision presented in a General Comment,20 a concluding observation of a treaty monitoring body21 or a reflection in a report of a Special Rapporteur.22 In addition, in some cases, treaty monitoring bodies and others charged with interpreting and developing human rights law can apply somewhat imprecise language or unclear methodology in their analyses, leaving space for further interpretation and potentially for varied levels of application in domestic legal systems.23 24 Thus, developing the Overarching Rights Analysis Table requires a significant degree of legal interpretation and judgement to assess, for example, the extent to which a particular proposition might be said to reflect a consensus across human rights institutions, or to be emerging but not yet established as a norm. For this reason, such an approach is best undertaken by an interdisciplinary group of researchers with expertise across relevant disciplines, such as law, medicine and public health.

Identifying the relative weight of a human rights standard as a matter of general international human rights law is an interpretive exercise, determined by the frequency with which the standard has been articulated, the nature and variety of bodies articulating it, and the nature of the human rights norm from which its articulation emerges (ie, a jus cogens, absolute or qualified right). Furthermore, it is difficult to say with certainty that a particular intervention being studied does or does not violate international human rights law as a general matter (i.e. in all cases). Whether a particular intervention (a) engages, and (b) violates human rights law in any particular case is likely to be dependent on its precise content, the nature and operation of the system in which it is applied, its interaction with other interventions, and whether that system can and does operate as a regulatory regime in which possible interferences with rights are effectively mitigated. Qualified rights may be limited by a state in pursuit of legitimate objectives and/or in ways permitted within the text of the right itself; a reduction in rights enjoyment does not always indicate a violation of rights. Nevertheless, even a prima facie legally permissible interference with rights should be justified by principles of necessity, rationality and effectiveness.

Conclusion

The methodology described here is an innovative approach to the effective and rigorous integration of analytical approaches drawn from the disciplines of human rights law and public health. The rights application and summary stages of the methodology (stages (ii) and (iii)) shed light on whether an intervention arc is likely to have justifiable rights implications. It is not a definitive legal analysis of whether a studied intervention always violates human rights law. Rather, this approach allows for the identification of directionality between a studied intervention and legally protected rights, taking into account both human rights law applied alone and human rights law applied in light of existing evidence of the impact of interventions garnered through a systematic review. This methodology’s integration into processes of Guideline development is, thus, a robust means of enacting a commitment to rights protection as part of optimising reproductive health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joanna Erdman for her contributions to the development of a catalogue of human rights statements relevant to sexual and reproductive rights, including abortion, which greatly assisted in developing the overarching rights analysis.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @fdelond

Contributors: All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data and to drafting and revising the the work. All authors approved the final version. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This work was supported by the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP). Professor de Londras acknowledges also the support provided by the Philip Leverhulme Prize (PLP-2017-181).

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, the World Health Organization.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: There are no data in this work

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Who Handbook for Guideline development. 2nd ed Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, et al. Grade evidence to decision (ETD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: introduction. BMJ 2016;353:i2016. 10.1136/bmj.i2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rehfuess EA, Stratil JM, Scheel IB, et al. The WHO-INTEGRATE evidence to decision framework version 1.0: integrating who norms and values and a complexity perspective. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e000844 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petticrew M, Knai C, Thomas J, et al. Implications of a complexity perspective for systematic reviews and Guideline development in health decision making. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e000899. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO) Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems. 2nd ed, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson HJ, Thomas S. The effect direction plot: visual display of non-standardised effects across multiple outcome domains. Res Synth Methods 2013;4:95–101. 10.1002/jrsm.1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glenton C, Carlsen B, Lewin S, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings—paper 5: how to assess adequacy of data. Implementation Sci 2018;13 10.1186/s13012-017-0692-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution of the world health organisation, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 10.UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights General Comment No. 14: the right to the highest attainable standard of health (E/C.12/2000/4, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rebouché R Abortion rights as human rights. Soc Leg Stud 2016;25:765–82. 10.1177/0964663916668391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO) Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services: guidance and recommendations, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burris S, Kawachi I, Sarat A. Integrating law and social epidemiology. J Law Med Ethics 2002;30:510–21. 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2002.tb00422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Čavoški A Science and law in environmental law and policy: the case of the European Commission. Transnational Environmental Law 2020;9:263–95. 10.1017/S2047102520000151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jasanoff S “Serviceable Truths: Science for Action in Law and Policy”. Texas Law Review 2015;93:1723–49. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2nd ed Chichester (UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G. 2013 grade Handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zampas C, Gher JM. Abortion as a Human Right--International and Regional Standards. Human Rights Law Review 2008;8:249–94. 10.1093/hrlr/ngn008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Besson S “Sources of International Human Rights Law: How General is General International Law?” : Besson S, D’Aspremont J, The Oxford Handbook on the sources of international law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ulfstein G Law Making by Human Rights Treaty Bodies” in Liivoja and Petman (eds) : International Law-Making: essays in honour of Jan Klabbers. Routledge; London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Flaherty M The concluding observations of United nations human rights Treaty bodies. Human Rights Law Review 2006;6:27–52. 10.1093/hrlr/ngi037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subedi SP Protection of human rights through the mechanism of un special Rapporteurs. Hum Rights Q 2011;33:201–28. 10.1353/hrq.2011.0011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters B Aspects of Human Rights Interpretation by UN Treaty Bodies” : Un human rights Treaty bodies: law and legitimacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mechlem K “Treaty Bodies and the Interpretation of Human Rights”. Vanderbilt J Transant'l L 2009;42:905–48. [Google Scholar]