Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to examine how published studies of inpatient to outpatient mental healthcare transition processes have approached measuring unnecessary psychiatric readmissions.

Design

Scoping review using Levac et al’s enhancement to Arksey and O’Malley’s framework for conducting scoping reviews.

Data sources

Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO, CINAHL, Cochrane and ISI Web of Science article databases were searched from 1 January 2009 through 28 February 2019.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

We included studies that (1) are about care transition processes associated with unnecessary psychiatric readmissions and (2) specify use of at least one readmission time interval (ie, the time period since previous discharge from inpatient care, within which a hospitalisation can be considered a readmission).

Data extraction and synthesis

We assessed review findings through tabular and content analyses of the data extracted from included articles.

Results

Our database search yielded 3478 unique articles, 67 of which were included in our scoping review. The included articles varied widely in their reported readmission time intervals used. They provided limited details regarding which readmissions they considered unnecessary and which risks they accounted for in their measurement. There were no perceptible trends in associations between the variation in these findings and the included studies’ characteristics (eg, target population, type of care transition intervention).

Conclusions

The limited specification with which studies report their approach to unnecessary psychiatric readmissions measurement is a noteworthy gap identified by this scoping review, and one that can hinder both the replicability of conducted studies and adaptations of study methods by future investigations. Recommendations stemming from this review include (1) establishing a framework for reporting the measurement approach, (2) devising enhanced guidelines regarding which approaches to use in which circumstances and (3) examining how sensitive research findings are to the choice of the approach.

Keywords: hospital readmission, administrative data, care transition, patient discharge, mental health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Closely following Levac et al’s established methodological framework for conducting scoping reviews, this study performed a comprehensive search of how unnecessary psychiatric readmissions are measured by studies concerned with inpatient to outpatient mental healthcare transitions.

Aligning to the purpose of scoping reviews to identify current gaps in knowledge and establish a new research agenda, this review does not assess the effectiveness of the approaches mentioned by the included studies in measuring unnecessary psychiatric readmissions.

There may exist other approaches to unnecessary psychiatric readmissions measurement used (1) by studies not concerned with care transitions or (2) within individual healthcare organisations, which have not been publicly shared through the mechanism of peer-reviewed journal articles that are indexed by the databases included in our review.

This scoping review is a critical step towards enabling the field to evaluate various care transition interventions’ comparative effects on unnecessary psychiatric readmission rates.

Background

Care transition for individuals being discharged from inpatient mental healthcare to outpatient settings is a growing focus for many healthcare delivery systems.1 2 Drivers of this increased interest include inpatient treatment’s high-resource requirements3 (especially for longer and repeated inpatient stays), as well as individuals being able to better maintain family, work, educational and other responsibilities alongside outpatient treatment.4 Studies of inpatient to outpatient mental healthcare transition processes, both observational1 5 and interventional,2 6 are thus on the rise, and many of them use the rate of post-discharge readmissions as an individual-level outcome measure to assess the quality of transition.7 8 Readmission rate associated with a care setting is its proportion of individuals who are rehospitalised within a certain time period since their previous hospitalisation.

Defining readmission rate requires, at minimum, (1) specification of the time period (ie, readmission time interval), (2) classification of ‘re’hospitalisation (ie, related to the previous hospitalisation and therefore possibly unnecessary or preventable, as opposed to an unrelated hospitalisation due to a new care need), and (3) cases that should be included/excluded from consideration. These specifications are becoming more important now than ever, as healthcare policymakers, payers, and professional groups are increasingly paying attention to accurately identifying unnecessary readmissions and better incentivising their prevention.9–13 However, it is unclear whether and how the increasingly prevalent studies of inpatient to outpatient mental healthcare transitions are defining each of these aspects of the measure.

Also unclear is whether there is a shared understanding by the field regarding which definition is appropriate for which mental healthcare circumstances. 3M Health Information Systems’ Potentially Preventable Readmissions Classification System14 offers a widely used proprietary methodology for measuring readmissions. It is difficult to glean from its publicly available information, however, what constitutes a meaningful readmission time interval and any mental health-specific considerations that need to be made when measuring unnecessary psychiatric readmissions.

Without established approaches to measuring unnecessary psychiatric readmissions (which, if not uniform, ought to at least be made explicit as to how they relate to or differ from one another), various transitional interventions using the measure cannot be adequately assessed alongside one another. Establishing widely usable, accepted and comparable approaches to this measurement means setting clear definitional parameters as to what constitutes an unnecessary psychiatric admission. Thus, as a first step towards being able to evaluate the interventions’ comparative effects on unnecessary psychiatric readmission rates, we conducted a scoping review of peer-reviewed literature to delineate the current landscape of how published studies have approached measuring unnecessary psychiatric readmissions.

Methods

We structured the scoping review according to Levac et al’s enhancement15 to Arksey and O’Malley’s six-stage methodological framework for conducting scoping reviews.16 The framework’s stages are (1) defining the research question, (2) identifying relevant literature, (3) study selection, (4) data extraction, (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results, and (6) consultation process and engagement of knowledge users. We aligned to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews17 (online supplemental file 1). Our team previously published a study protocol paper detailing the methods for this review18; briefly, they are summarised below.

bmjopen-2020-045364supp001.pdf (98KB, pdf)

Stage 1: defining the research question

Aligning the notion of ‘unnecessary readmission’ to Goldfield et al’s19 concept of ‘potentially preventable readmission’ (defined as a subsequent admission that occurs within the readmission time interval and is clinically related to a prior admission), the scoping review aimed to answer the following questions:

What durations are used as the unnecessary psychiatric readmission time interval?

What criteria are applied to designating a psychiatric readmission as unnecessary?

What risks are adjusted for in calculating unnecessary psychiatric readmission rates?

Stage 2: identifying relevant literature

We conducted a comprehensive review of the existing literature and evidence base to systematically examine what is known about measuring unnecessary psychiatric readmissions. Working with our institutions’ librarians with extensive experience in building systematic and comprehensive search strategies, we iteratively developed our search strategy. In particular, we refined our search strategy to include terms that are often used interchangeably. For example, in addition to ‘readmission,’ our initial preliminary searches based on early iterations of the strategy helped us identify related terms to include, such as unnecessary hospitalisation, inappropriate hospitalisation, unplanned admission and unscheduled admission. We harvested search terms using benchmark article terms and subject headings, titles and abstracts of key articles, dictionaries, and synonyms and subject headings within Embase and PubMed’s Medical Subject Headings database. We used Boolean logic and proximity operators to combine and refine the search terms. The search strategy was initially formulated for Medline (Ovid) (table 1), then further tailored as appropriate for use with Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO, CINAHL, Cochrane and ISI Web of Science article databases. These sources include relevant journals within the fields of medicine, health services and the social sciences, and were selected to capture a comprehensive sample of literature.

Table 1.

Medline (Ovid) search strategy

| Search term/line number | Conceptual term of interest | Search term entered into Ovid-Medline | Number of hits |

| 1 | Mental disorders | psychiatric.ti. OR “mental disorder”.ti. OR “mental disorders”.ti. OR “mental illness”.ti. OR “mentally ill”.ti. |

83 986 |

| 2 | Inpatient psychiatric settings | Exp “Psychiatric hospitals”/ OR Exp “hospital Psychiatric Department”/ OR “Psychiatric treatment center”.mp. OR “Psychiatric Hospital”.mp. OR “psychiatric unit”.mp. OR “psychiatric units”.mp. OR “Mental Institution”.mp. OR “Mental Hospital”.mp. OR “Psychiatric Department”.mp. OR “Psychiatric treatment centers”.mp. OR “Psychiatric Hospitals”.mp. OR “Mental Institutions”.mp. OR “Mental Hospitals”.mp. OR “Psychiatric Departments”.mp. OR “Psychiatric Ward”.mp. OR"psychiatric inpatient”.mp. OR “psychiatric inpatients”.mp. |

41 507 |

| 3 | Inpatient psychiatric admission | “psychiatric hospitalization”.mp. OR “psychiatric hospitalizations”.mp. OR “psychiatric readmission”.mp. OR “psychiatric readmissions”.mp. OR “psychiatric rehospitalization”.mp. OR “psychiatric rehospitalizations”.mp. OR “psychiatric admission”.mp. OR “psychiatric admissions”.mp | 2905 |

| 5 | 1 or 2 or 3 | 110 553 | |

| 6 | Patient readmission | Exp “Patient Readmission”/ | 14 332 |

| 7 | Readmission | Readmission*.mp. OR readmitted.ti. | 28 315 |

| 8 | Rehospitalisation | Rehospitali*.mp. | 5515 |

| 9 | Unnecessary admissions | “Unnecessary admission”.mp. OR “preventable hospitalizations”.mp. OR “preventable hospitalization”.mp. |

315 |

| 10 | 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 | 31 946 | |

| 11 | 5 and 10 | 1747 |

Stage 3: study selection

We screened peer-reviewed articles published in English from January 2009 through February 2019. We set the review time frame to start in 2009, so that it follows the 2008 publication of Goldfield et al’s19 concept of ‘potentially preventable readmission,’ to which we align our notion of ‘unnecessary readmission’. We set the review time frame to end in February 2019, as we initiated our review tasks in March 2019. We included an article if it (1) concerns the adult mental health population, (2) measures psychiatric readmission rates, (3) is set in a healthcare context, (4) is conducted in (and explicitly mentions) the context of some care transition process that is either already being carried out (for non-intervention studies) or is being tested as an intervention (for intervention studies), and (5) specifies at least one readmission time interval used. We excluded editorials and other articles that report on individual viewpoints. For each of the title/abstract and full-text screening phases, the criteria were initially applied to 10% of articles to be screened, where two screeners (CW and BK) first independently screened, then compared with one another their individual decisions on, whether each article meets the criteria. For articles for which the individual decisions differed, the screeners held discussions to reach consensus. The resulting shared understanding of the criteria was applied to screening the remaining articles, for which CW and BK each served as the primary screener for a distinct half of the articles. For articles that the primary screener deemed as needing additional discussion, the non-primary screener among CW or BK served as the secondary screener, and discussions were held to reach consensus.

Stage 4: data extraction

Data extraction from articles to be included in the scoping review used an Excel20 -based template. The template was piloted on 10% of articles to be reviewed, where CW served as the primary data extractor for half of the articles, and BK served as the secondary extractor, reviewing the same articles to verify and augment the extraction. The other half of the articles had BK as the primary data extractor and CW as the secondary extractor. Articles for which the primary and secondary data extractors did not agree on the extracted content were discussed to reach consensus. The resulting shared understanding of the approach to data extraction was applied to the remaining articles, for which CW and BK each served as the primary extractor for a distinct half of the articles. For articles that the primary extractor deemed as needing additional discussion, the non-primary extractor among CW or BK served as the secondary extractor, and discussions were held to reach consensus.

Stage 5: collating, summarising and reporting the results

Aligning to the specific questions that our scoping review aimed to answer (listed under the Stage 1: defining the research question section), we summarised findings along the dimensions of (1) readmission time interval, (2) unnecessary readmission definition and (3) case-mix adjustment approach used by our reviewed articles. We also assessed the extracted data for any prevalent trends in study characteristics across our reviewed articles, and independently reviewed the data to identify any emergent themes. We used constant comparison combined with consensus-building discussions21 to finalise notable trends and themes to be reported.

Stage 6: consultation process and engagement of knowledge users

We closely engaged our multidisciplinary research colleagues and partnered healthcare system representatives for each of stages 1 through 5 above. These individuals we consulted have clinical and administrative expertise in mental healthcare services, as well as in how the services are structured and integrated to be delivered across different levels of the mental healthcare system. They included front-line practitioners, leadership of local, regional and national care networks, and health services researchers with expertise in care transitions and admissions data.

Patient and public involvement

Our consultants included patient representatives who helped shape the research team’s study steps. These representatives came to be involved with our work through the first author’s research centre (Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research (CHOIR), a Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center of Innovation)’s established Veteran Engagement in Research Group (VERG). VERG is a CHOIR-based community that is explicitly chartered to engage veterans and their family members as active partners in research through communication regarding opportunities to be involved, codevelopment of research ideas and collaboration on tasks. The representatives played a key role in helping us understand the current status of readmissions and formulating the questions that our scoping review focused on answering. They were consulted on developing the criteria for study selection and disseminating our findings to the larger healthcare community beyond the scientific community.

Results

Characteristics of reviewed articles

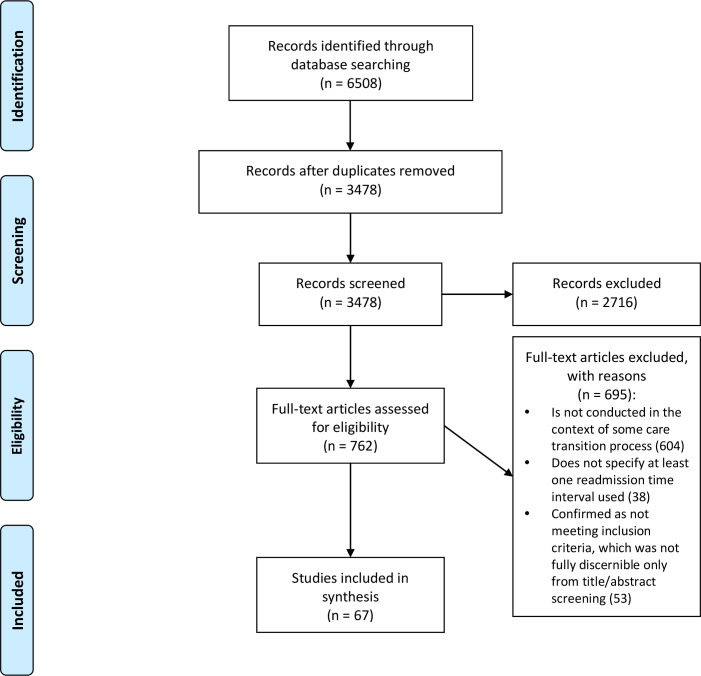

The database searches identified 3478 unique articles (figure 1). Through screening the title and abstract for each of these articles, 762 were designated for full-text screening. The full-text screening found 67 articles to include in the review, containing information related to measurement of unnecessary psychiatric readmissions in the context of some inpatient to outpatient care transition process.1 2 6 8 22–84Included studies were conducted in 19 different countries—Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iran, Israel, Italy, Japan, Norway, Singapore, South Africa, Switzerland, the UK and the USA. Table 2 lists the characteristics of each included article. Table 3 presents a summary of findings from the included articles. The articles spanned original research to systematic reviews, and methods used included quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods approaches. Seventeen of these articles reported on a randomised controlled trial of a care transition intervention.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the scoping review. From Moher et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org.

Table 2.

Characteristics of articles included in the scoping review

| Author(s) | Publication year | Country | Design | Healthcare context and setting | Study/target population | Diagnoses and comorbidities | Care transition process category | Sample size | Control | Voluntariness of re/admissions | Readmission time interval | Criteria for designating a readmission as unnecessary | Criteria for excluding a readmission from being considered unnecessary | Risk adjustments in calculating readmission rates |

| Baeza et al22 | 2018 | Brazil | Observational | Hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 401 | No control | Unspecified | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Barekatain et al23 | 2014 | Iran | Randomised controlled trial | Hospital(s) | Adults | Bipolar I and schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorders | Outpatient follow-up; patient education | 123 | Usual care | Unspecified | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Barker et al24 | 2011 | UK | Observational | Community setting(s) | Adults | Mental health and substance use disorders | Outpatient follow-up | Unspecified | Historical control(s) | Both involuntary and voluntary | 7 days–12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Bastiampillai et al25 | 2010 | Australia | Observational | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Community liaison; outpatient follow-up | Unspecified | Historical control(s) | Unspecified | 28 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Bernet26 | 2013 | USA | Observational | Healthcare system(s) | Adults (military veterans) | Mental health and substance use disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 124 | No control | Unspecified | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Sociodemographic variables |

| Bonsack et al27 | 2016 | Switzerland | Randomised controlled trial | Community setting(s) and psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Care coordination; community liaison; discharge planning; outpatient follow-up; patient education | 102 | Usual care | Unspecified | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Clinical and sociodemographic variables |

| Botha et al28 | 2018 | South Africa | Quasi- experimental | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults (male) | Serious mental illnesses | Outpatient follow-up; patient education | 120 | Patients who had been discharged on non-recruitment days during the same time period | Unspecified | 90 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Burns et al29 | 2016 | UK | Randomised controlled trial | Community setting(s) and psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Psychotic disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 333 (study 1 of 2); 330 (study 2 of 2) |

Patients without community treatment orders | Both involuntary and voluntary | 12 months (study 1 of 2); 36 months (study 2 of 2) |

Unspecified | Recall to hospital of a patient on a community treatment order (CTO), as this is understood as being part of the CTO process rather than an outcome (if a recall ended in the CTO being revoked, then considered a readmission, calculated from the first day of the recall) | Unspecified |

| Bursac et al30 | 2018 | USA | Quasi- experimental | Psychiatric prison unit(s) | Adults (male and justice- involved) | Mental health disorders | Care coordination; community liaison; discharge planning; patient education | 30 | Patients who are frequently rehospitalised and participants themselves pre- intervention | Involuntary | 15 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Callaly et al31 | 2010 | Australia | Observational | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 115 | No control | Unspecified | 28 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Chen et al32 | 2019 | China | Randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Bipolar I disorder | Patient education | 140 | Usual care | Unspecified | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Service use variables |

| Clibbens et al33 | 2018 | Various (predominantly middle-income to high- income countries) | Rapid review | Community setting(s) and psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Discharge planning | Various | Various | Unspecified | Various (28, 30 days) | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Currie et al34 | 2018 | Canada | Observational | Community setting(s) and psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults (with experience of homelessness) | Mental health disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 497 | No control | Unspecified | 2, 6, 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Service use and sociodemographic variables |

| Dixon et al35 | 2009 | USA | Randomised controlled trial | Healthcare system(s) | Adults (military veterans) | Serious mental illnesses | Community liaison; discharge planning; outpatient follow-up; patient education | 135 | Usual care | Unspecified | 6 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Healthcare site variables |

| Donisi et al36 | 2016 | Various (Australia, Canada, Colombia, Egypt, Germany, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, UK, USA) | Systematic review | Community setting(s) and psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Various | Various | Various | Both involuntary and voluntary | Various (30 days; 1–12 months; more than 1 year) |

Unspecified | Unspecified | Various variables (including clinical, service use and sociodemographic) |

| Faurholt- Jepsen et al37 | 2017 | Denmark | Randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Unipolar and bipolar disorders | Patient education | To be determined (study not completed at time of publication) | Usual care | Unspecified | 3, 6 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Service use and sociodemographic variables |

| Fullerton et al38 | 2016 | USA | Observational | Various | Adults (Medicaid enrollees) | Mental health, substance use and medical disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 32 037 | Patients with similar propensity scores who did not receive intermediate services | Unspecified | 90 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Giacco et al39 | 2018 | Various (Australia, Japan, Switzerland, UK) | Systematic review | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Various | Various | Various | Both involuntary and voluntary | Various (12 months; 12, 24 months; unspecified) |

Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Gouzoulis- Mayfrank et al40 | 2015 | Germany | Randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Schizophrenia/schizophreniform/schizoaffective and substance use disorders | Outpatient follow-up; patient education | 100 | Usual care | Voluntary | 3, 6, 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Grinshpoon et al41 | 2011 | Israel | Observational | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 908 | No control | Unspecified | 180 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Various variables |

| Habit et al42 | 2018 | USA | Quasi- experimental | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health and substance use disorders | Information provision | Unspecified | No control | Unspecified | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Hanrahan et al43 | 2014 | USA | Randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health and major medical (eg, diabetes, asthma, cancer) disorders | Outpatient follow-up; patient education | 40 | Usual care | Unspecified | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Hegedüs et al44 | 2018 | Switzerland | Pilot/exploratory | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health and substance use disorders | Patient education | 29 | Usual care | Unspecified | 7 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Hengartner et al45 | 2017 | Switzerland | Secondary analysis following a randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health and substance use disorders | Community liaison; discharge planning; outpatient follow-up | 151 | Usual care | Both involuntary and voluntary | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Hengartner et al46 | 2016 | Switzerland | Randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health and substance use disorders | Community liaison | 151 | Usual care | Unspecified | 3, 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Hennemann et al47 | 2018 | Various (Finland, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Sweden) | Systematic review | Various | Adults | Mental health disorders | Patient education | Various | Various | Unspecified | Various (4, 9, 12, 18, 24 months) |

Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Hutchison et al8 | 2019 | USA | Observational | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults (Medicaid enrollees) | Mental health and substance use disorders | Community liaison; outpatient follow-up | 1724 | Usual care | Unspecified | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Diagnosis, geographical area, service use and sociodemographic variables |

| Kidd et al48 | 2016 | Canada | Quasi- experimental | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Serious mental illnesses | Community liaison; outpatient follow-up | 23 | No control | Unspecified | 1, 6 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Kim et al49 | 2011 | USA | Observational | Hospital(s) | Adults (military veterans) | Mental health and substance use disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 53 363 | No control | Unspecified | 84 days (other than study period) | Unspecified | Unspecified | Diagnosis, insurance type, service use and sociodemographic variables |

| Kisely et al50 | 2014 | Various (UK, USA) | Systematic review | Community setting(s) | Adults | Serious mental illnesses | Outpatient follow-up | Various | Usual care | Unspecified | Various (11–12, 12 months) |

Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Kolbasovsky51 | 2009 | USA | Quasi- experimental | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Community liaison; outpatient follow-up; patient education | 652 | Historical control(s) | Unspecified | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Diagnosis, insurance type, service use and sociodemographic variables |

| Kurdyak et al1 | 2018 | Canada | Observational | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Schizophrenia | Outpatient follow-up | 19 132 | No physician follow-up | Unspecified | 210 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Clinical, geographical area, service use and sociodemographic variables |

| Lay et al52 | 2015 | Switzerland | Randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health and substance use disorders | Patient education; outpatient follow-up | 238 | Usual care | Involuntary | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Lay et al53 | 2012 | Switzerland | Randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Patient education; outpatient follow-up | To be determined (study not completed at time of publication) | Usual care | Both involuntary and voluntary | 12, 24 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Lee et al54 | 2015 | China | Quasi- experimental | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health and substance use disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 210 | Usual care | Unspecified | 6, 12, 18 months |

Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Liem and Lee55 | 2013 | China | Systematic review | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health and substance use disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 140 | Usual care | Unspecified | 12, 24 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Mattei et al56 | 2017 | Italy | Observational | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health and substance use disorders | Patient education | 52 | Not taking part in any psychoeducation groups/rehabilitation activities | Both involuntary and voluntary | 6 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| McDonagh et al57 | 2018 | USA | Quasi- experimental | Hospital(s) | Adults (military veterans) | Mental health disorders | Care coordination; patient education | Unspecified | No control | Unspecified | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Nubukpo et al58 | 2016 | France | Observational | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health and substance use disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 330 | No control | Unspecified | 24 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Ortiz59 | 2018 | USA | Observational | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Care coordination; outpatient follow-up | 60 254 | No control | Both involuntary and voluntary | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Diagnosis and service use variables |

| Passley-Clarke60 | 2018 | USA | Quasi- experimental | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Patient education | 216 patients, 2 staff | No control | Unspecified | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Perez et al61 | 2017 | Colombia | Observational | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 224 | No control | Unspecified | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Prochaska et al62 | 2014 | USA | Randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Patient education | 224 | Usual care | Both involuntary and voluntary | 3, 6, 12, 18 months |

Unspecified | Unspecified | Clinical variables |

| Rabovsky et al63 | 2012 | Switzerland | Randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Patient education | 87 | Open social activity group | Unspecified | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Roos et al64 | 2018 | Norway | Randomised controlled trial | Community setting(s) and psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Community liaison; outpatient follow-up | 41 | Usual care | Voluntary | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Rothbard et al65 | 2012 | USA | Quasi- experimental | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 176 | Usual care | Involuntary | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Clinical, diagnosis, insurance type, service use and sociodemographic variables |

| Rowley et al66 | 2014 | UK | Pilot/exploratory | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults (male) | Mental health, substance use and medical disorders | Care coordination; discharge planning | 50 staff | No control | Unspecified | 1 month | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Shaffer et al2 | 2015 | USA | Quasi- experimental | Community setting(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Community liaison; outpatient follow-up | 149 | Historical control(s) | Unspecified | 30, 31–180 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Diagnosis, service use and sociodemographic variables |

| Shimada et al67 | 2016 | Japan | Non-controlled intervention | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Schizophrenia | Outpatient follow-up | 44 | Group occupational therapy only | Unspecified | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Simpson et al68 | 2014 | UK | Pilot/exploratory | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 46 | Usual care | Unspecified | 1, 3 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Sledge et al69 | 2011 | USA | Randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Serious mental illnesses | Outpatient follow-up | 74 | Usual care | Unspecified | 9 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Sloan et al70 | 2010 | USA | Quasi- experimental | Hospital(s) | Adults (military veterans) | Mental health and substance use disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 1409 | Patients discharged while in the continuity of care model | Unspecified | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Taylor et al71 | 2016 | USA | Observational | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults (Medicaid enrollees) | Mental health disorders | Patient education | 195 | Usual care | Both involuntary and voluntary | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Homelessness, service use and sociodemographic variables |

| Thambyrajah et al72 | 2014 | Singapore | Observational | Various | Adults | Mental health disorders | Community liaison | 88 | No control | Unspecified | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Thomas and Rickwood73 | 2013 | Various (UK, USA) | Systematic review | Various | Adults | Mental health disorders | Outpatient follow-up | Various | Various | Voluntary | Various (12, 37–42 months) | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Tomita et al74 | 2014 | USA | Secondary analysis following a randomised controlled trial | Residential programme(s) | Adults (with experience of homelessness) | Serious mental illnesses | Community liaison | 150 | Usual care | Unspecified | 13.5–18 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Tomko et al75 | 2013 | USA | Observational | Hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health and substance use disorders | Patient education; outpatient follow-up | 504 | Patients excluded from the discharge medication service (eg, due to being a part of other treatment teams) | Unspecified | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Valimaki et al76 | 2017 | Finland | Randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Psychotic disorders | Information provision; patient education | 1139 | Usual care | Both involuntary and voluntary | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Videbech and Deleuran77 | 2016 | Denmark | Research database construction | Community setting(s) and psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Depressive disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 54 001 | Not applicable (study is on constructing a research database) | Unspecified | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Vigod et al78 | 2013 | Various (USA, other high-income countries) | Systematic review | Various | Adults | Mental health disorders | Various | Various | Various | Voluntary | Various (3, 6–24 months) | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Vijayaraghavan et al79 | 2015 | USA | Observational | Community setting(s) and psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health and substance use disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 4663 | No control | Unspecified | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Diagnosis, service use and sociodemographic variables |

| Von Wyl et al6 | 2013 | Switzerland | Randomised controlled trial | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Community liaison; discharge planning; outpatient follow-up; patient education | 160 | Usual care | Unspecified | 3, 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Wong80 | 2015 | China | Observational | Hospital(s) | Adults (aged 65 and over) | Mental health disorders | Outpatient follow-up | 368 | No control | Unspecified | 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 months |

Unspecified | Unspecified | Sociodemographic variables |

| Xiao et al81 | 2015 | China | Observational | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Schizophrenia | Outpatient follow-up | 876 | No control | Unspecified | 12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Yates et al82 | 2010 | USA | Non-controlled intervention | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults (justice- involved) | Mental health and substance use disorders | Patient education | 145 | No control | Unspecified | 6–60 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Zisman-Ilani et al83 | 2018 | Israel | Quasi- experimental | Psychiatric hospital(s) | Adults | Mental health disorders | Discharge planning | 101 | Usual care | Unspecified | 6–12 months | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Zuehlke et al84 | 2016 | USA | Quality improvement | Hospital(s) | Adults (military veterans) | Mental health disorders | Care coordination; discharge planning | 352 patients, 27 staff | No control | Unspecified | 30 days | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

Table 3.

Summary of findings from the 67 articles included in the scoping review

| Domain | Summary of findings |

| Readmission time interval |

|

| Unnecessary readmission definition |

|

| Case-mix adjustment approach |

|

| Study setting |

|

| Target population |

|

| Sample size and comparisons conducted |

|

| Voluntariness of readmissions |

|

| Care transition processes |

|

Findings regarding the three research questions

Readmission time interval

We found wide variation in the readmission time intervals used by included studies, ranging from 7 days to 60 months. The most prevalent intervals were 1 month (including intervals specified as 28 or 30 days) and 12 months, used by 22 and 29 included studies (32.8% and 43.3%), respectively. Twenty studies (29.9%) used more than one readmission time interval (eg, 12 and 24 months), and eight studies (11.9%) used a unique interval that was not used by other included studies (eg, 210 days). Studies using the unit of ‘month’ for the readmission time interval did not address the variability of the number of days included in a month depending on the time of the calendar year.

Unnecessary readmission definition

Each of our included studies, per our inclusion criteria mentioned above, was a study conducted in the context of some care transition process that the study examined for potential association with unnecessary psychiatric readmissions (ie, readmissions that should be minimised). Only two included studies, however, reported within a single article,29 specified a criterion by which they excluded a readmission from being considered unnecessary—namely, when the readmission was deemed a component of their planned care transition process. Otherwise, included studies did not make explicit the criteria that they applied to designating a readmission as unnecessary.

Case-mix adjustment approach

Forty-nine of the included studies (73.1%) did not specify risk adjustments that they made in calculating readmission rates. The most prevalent variables for which adjustments were specified were clinical (including diagnosis), service use, and sociodemographic, specified by 12, 13 and 14 included studies (17.9%, 19.4% and 20.9%), respectively. Thirteen studies (19.4%) specified adjustments for more than one type of variable (eg, service use and sociodemographic). Adjustments for geographical area and insurance type variables were specified by two and three included studies (3.0% and 4.5%), respectively, and healthcare site variables and homelessness variables were specified as having been adjusted for by one included study (1.5%) each.

Additional findings from the review

Study setting

Forty-eight of the included studies (71.6%) were conducted in the setting of one or more freestanding psychiatric hospitals (nine of which also involved community settings), while 10 (14.9%) were conducted at general hospitals or healthcare systems offering inpatient psychiatric services. Three studies (4.5%) were conducted in community settings only (eg, not specific to or managed by one or more hospitals or healthcare systems), and psychiatric prison units and residential programmes were the focus of one included study (1.5%) each.

Target population

Each of our included studies, per our inclusion criteria, concerned the adult mental health population. Seventeen studies (25.4%) specified taking into consideration their population’s substance use diagnoses, while one and two studies (1.5% and 3.0%) specified considering their population’s medical diagnoses and both substance use and medical diagnoses, respectively. Seventeen studies (25.4%) focused specifically on one or more mental health disorder type (eg, depressive disorders, psychotic disorders). Six, three and three studies (9.0%, 4.5% and 4.5%) were on military veterans, Medicaid enrollees and male individuals, respectively. Individuals with experience of homelessness and justice-involved individuals were the focus of two studies (3.0%) each, and one study (1.5%) focused on individuals aged 65 and over.

Sample size and comparisons conducted

Sample size among the included studies varied widely, ranging from 23 to 60 254 participants among the studies that specified a sample size. Of the 13 studies (19.4%) that did not specify sample sizes, 7 were literature reviews and 2 were study protocols. Twenty-seven studies (40.3%) examined comparisons with usual care, while 20 studies (29.9%) did not have comparison groups.

Voluntariness of readmissions

Forty-eight studies (71.6%) did not specify whether they were differentiating between voluntary and involuntary readmissions. Of the remaining 19 studies (28.4%), 12 studies specified considering both voluntary and involuntary readmissions, while four and three studies considered only voluntary and involuntary readmissions, respectively.

Care transition processes

Guided by Burke et al’s Ideal Transition in Care (ITC) framework,85 we assigned our included studies’ associated care transition processes to six categories:

Care coordination (eg, among different provider disciplines, interprofessional treatment teams and/or clinics), aligned to ITC’s ‘coordinating care among team members’ component.

Community liaison (eg, arranging for community-based case management services and/or enlisting help of social/community/informal supports), aligned to ITC’s ‘enlisting help of social and community supports’ component.

Discharge planning (eg, collaborative preparation with the patient and their family), aligned to ITC’s ‘discharge planning’ component.

Information provision (eg, reminders (eg, via telephone and/or postcards) to attend upcoming appointments), aligned to ITC’s ‘complete communication of information’ and ‘availability, timeliness, clarity and organisation of information’ components.

Outpatient follow-up (eg, including telephone check-ins, home visits, peer support and crisis teams, handled primarily by the hospital or healthcare system rather than by community programmes (in order to differentiate from care transition processes that are categorised as community liaison)), aligned to ITC’s ‘outpatient follow-up’ component.

-

Patient education (eg, for self-management via individual/family/group psychoeducation, regarding disorder-specific therapy and/or use of crisis cards), aligned to ITC’s ‘educating patients to promote self-management’ component.

(Note: care transition processes exhibiting ITC’s ‘medication safety’ and ‘monitoring and managing symptoms’ components were categorised as either outpatient follow-up or patient education, depending on whether the safety and management component of the process was conducted during outpatient follow-up or for patient education, respectively. ITC’s ‘advance care planning’ component was not exhibited by our included studies’ care transition processes.)

Forty-four studies’ (65.7%) care transition processes exhibited outpatient follow-up, 24 (35.8%) exhibited patient education, and 11 (16.4%) exhibited both outpatient follow-up and patient education. The category of information provision was least prevalent and exhibited by care transition processes of two included studies (3.0%). Twenty-six studies’ (38.8%) care transition processes exhibited more than one of the six categories.

Notably, there were no perceptible trends or emergent themes in associations between the findings regarding the three research questions (ie, readmission time interval, unnecessary readmission definition and case-mix adjustment approach), and the included studies’ setting, target population, sample size, comparisons conducted, voluntariness of readmissions or categories of care transition processes.

Discussion

As healthcare systems increasingly focus on enhancing inpatient to outpatient mental healthcare transitions, care transition interventions in support of this effort are being actively observed, devised and tested. Unnecessary psychiatric readmissions is a commonly measured outcome for these investigations. However, conducting valid comparisons across different investigations is only possible if either (1) the measurement is approached in a standardised way or (2) deviations in approaches are made explicit. Our scoping review thus focused on examining how peer-reviewed published studies on care transition interventions have approached measuring unnecessary psychiatric readmissions.

The 67 articles included in our review varied widely in their reported readmission time intervals used. Only one article reported a criterion for not considering a readmission as unnecessary, and a majority of the articles did not specify risks that they adjusted for in calculating unnecessary psychiatric readmission rates. Each of (1) the time interval used, (2) readmissions that are considered unnecessary (ie, preventable) versus necessary (ie, not an indication of improvable care quality), and (3) risks that are accounted for are key specifications for calculating the readmission rate as an outcome. Hence, the limited details with which these specifications are reported are a noteworthy gap identified by this scoping review, and one that can hinder both the replicability of conducted studies and adaptations of study methods by future investigations.

Variation in definitions used, or even variation in the level of measurement details reported, would be less of a concern if there were patterns to the variation that indicate different specifications’ prevalence among subgroups of investigations (eg, for different diagnoses, for different study settings, for different types of care transition interventions, for different lengths of inpatient stay). For instance, if these patterns were present, there may be clinically appropriate reasons (even if not reported in detail) to guide future investigations’ decisions for which specifications of time interval, unnecessariness criteria and risk adjustments to use when measuring unnecessary psychiatric readmissions. However, as noted above, this scoping review identified no perceptible trends in associations between the specifications and study characteristics. This gap in knowledge makes it difficult for future studies of care transition interventions to make informed decisions about how to measure unnecessary psychiatric readmissions in light of their specific study’s characteristics.

These findings point to several directions in which future research can proceed to address the identified gaps. One direction is to establish a framework that studies can standardly use to specify and report their approaches to measuring unnecessary psychiatric readmissions. Such a framework is imperative for subsequent development of a precise and shared taxonomy, which studies can use to describe their approaches so that their similarities and differences can be clearly understood. A second direction is to devise enhanced guidelines regarding readmission intervals, definitions of unnecessariness and risk adjustments that are especially relevant for specific study contexts (eg, particular target populations, types of intervention and/or lengths of inpatient stay). Both clinical and measurement expertise ought to be reflected in the development of such guidelines. Especially when applied to studying the impact of an intervention on readmissions, the guidelines can be extended to encompass important additional requirements regarding the intervention process, such as including intervention fidelity and the handling of the timing of implementing key intervention components (eg, time interval measurement should be appropriately adjusted in cases for which readmission is part of the intervention design). A third direction is to conduct empirical data-based investigations into how sensitive research findings are to specific choices of intervals, definitions and adjustments that are used for readmissions measurement. For example, if conclusions of studies using the measure are altered when using one definition of unnecessariness versus another, the aforementioned framework and guidelines should focus on requiring studies to justify their choice of definition.

Four limitations must be noted regarding this scoping review. First, the review does not assess the appropriateness of the unnecessary psychiatric readmissions measurement approaches used by the included studies (eg, whether a study’s measurement approach was adequate in light of the study’s research objectives). However, this closely aligns to the purpose of scoping reviews to (1) identify a current state of knowledge in the literature, (2) elucidate any gaps and (3) establish a new research agenda. Thus, the purpose of our scoping review was not to collate empirical evidence regarding which measurement approaches are appropriate for which types of studies concerned with care transition interventions. The main motivation for conducting this review is rather to make explicit the work that is still needed to establish clearly defined and comparable measurement approaches, so that studies of care transition interventions that report unnecessary psychiatric readmissions as an outcome can be appropriately compared alongside one another.

Second, there are alternative categorisations possible for data of each of our extracted domains (eg, ‘serious mental illnesses’ can be further specified into individual diagnoses), which can impact how our review’s findings are interpreted. We decided on the categorisations that we used by balancing two considerations: (1) where possible, we adhered closely to the terminologies used by the included studies themselves in referring to the categories for which we were extracting data; (2) we sought close feedback through our consultation process on the broadness versus specificity of our categorisations in order to allow the audience to comprehend our findings at a high level and also seek desired additional information by accessing our cited included studies.

Third, limiting the included studies to those concerning care transition interventions (as recommended by peer reviewers of our protocol to ensure feasibility of our review, given the widespread use of readmissions as a measure) could have led to findings that are less widely applicable to studies that measure unnecessary psychiatric readmissions but are not conducted in the context of care transition interventions. Additional reviews of such studies can be expected to identify, to varying extents, similar issues of studies using different definitions of unnecessary psychiatric readmissions and reporting limited details surrounding their choice of definition. Our recommendations above for future work (establishing a reporting framework, devising guidelines for measuring unnecessary readmissions and investigating the sensitivity of research findings to varied specifications of the readmissions measure) can in turn be applicable to psychiatric readmissions beyond those that are considered in the context of care transition interventions. Further, understanding how those other studies trend in their approaches to measuring unnecessary psychiatric readmissions, similarly to or differently from our included studies, will be important for establishing widely usable, accepted and comparable approaches to this measurement. It will be important for us and others to be mindful of the care transition focus of our search when building on this review in future research.

Fourth, there may exist unnecessary psychiatric readmissions measurement approaches that individual healthcare organisations use to assess their care transition interventions, which have not been publicly shared through the mechanism of peer-reviewed journal articles that are indexed by the databases included in our review. Other grey literature and non-English articles may also describe approaches that we did not include. As our research moves forward from this review to examine the evidence for appropriate measurement approaches, we will specifically plan for soliciting expert knowledge (as we have done through this scoping review’s consultation process) from a wide range of healthcare researchers, practitioners, industry leaders and certainly individuals experiencing psychiatric readmissions to maximise our opportunity to learn of additional potential measurement approaches existent in the field.

Conclusions

Findings from this scoping review enable an increased understanding of how peer-reviewed published studies on care transition interventions have approached measuring unnecessary psychiatric readmissions. The articles included in our review varied widely in their reported readmission time intervals used, and they provided limited details regarding which readmissions they considered unnecessary and which risks they accounted for in their measurement. For studies of care transition interventions that report unnecessary psychiatric readmissions as an outcome to be replicable, adaptable and appropriately comparable alongside one another, recommended steps for the field include (1) establishing a framework that studies can standardly use to specify and report their approaches to measuring unnecessary psychiatric readmissions, (2) devising enhanced guidelines regarding readmission intervals, definitions of unnecessariness and risk adjustments that are especially relevant for specific study contexts (eg, particular target populations and/or types of intervention), and (3) conducting empirical data-based investigations into how sensitive research findings are to specific choices of intervals, definitions and adjustments that are used for measurement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Michelle Doering, MLIS, Bernard Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine, for creating systematic search strategies. We would also like to thank A Rani Elwy, PhD, at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University and the VA Bedford Healthcare System, for connecting our team to health services researchers with expertise in readmissions measurement.

Footnotes

Contributors: BK and CW developed the scoping review protocol, with close guidance from EKP on the review’s conceptualisation. CW led the development of the search strategy and refined the data extraction domains together with BK and CBW. BK and CW conducted the study selection through results collation steps. BK led the preparation of the manuscript draft, and CW, CBW and EKP provided critical revisions to the manuscript’s intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse and VA HSR&D QUERI (grant number 5R25MH08091607).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information. The presented research is a literature review of published data; there are no additional unpublished data.

References

- 1.Kurdyak P, Vigod SN, Newman A, et al. . Impact of physician follow-up care on psychiatric readmission rates in a population-based sample of patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2018;69:61–8. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaffer SL, Hutchison SL, Ayers AM, et al. . Brief critical time intervention to reduce psychiatric rehospitalization. Psychiatr Serv 2015;66:1155–61. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driessen M, Schulz P, Jander S, et al. . Effectiveness of inpatient versus outpatient complex treatment programs in depressive disorders: a quasi-experimental study under naturalistic conditions. BMC Psychiatry 2019;19:380. 10.1186/s12888-019-2371-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.First Step Behavioral Health. Inpatient v Inpatient vs outpatient Treatmen, 2020. Available: https://firststepbh.com/blog/inpatient-vs-outpatient/ [Accessed 5 Jul 2020].

- 5.Guzman-Parra J, Moreno-Küstner B, Rivas F, et al. . Needs, perceived support, and hospital readmissions in patients with severe mental illness. Community Ment Health J 2018;54:189–96. 10.1007/s10597-017-0095-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Wyl A, Heim G, Rüsch N, et al. . Network coordination following discharge from psychiatric inpatient treatment: a study protocol. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:220. 10.1186/1471-244X-13-220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen CS, Tiet QQ, Harris AHS, et al. . Telephone monitoring and support after discharge from residential PTSD treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv 2013;64:13-20. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutchison SL, Flanagan JV, Karpov I, et al. . Care management intervention to decrease psychiatric and substance use disorder readmissions in Medicaid-Enrolled adults. J Behav Health Serv Res 2019;46:533–43. 10.1007/s11414-018-9614-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Hospital Association Examining the drivers of readmissions and reducing unnecessary readmissions for better patient care, 2011. Available: https://www.aha.org/guidesreports/2018-02-09-examining-drivers-readmissions-and-reducing-unnecessary-readmissions [Accessed 25 Sep 2020].

- 10.Upadhyay S, Stephenson AL, Smith DG. Readmission rates and their impact on hospital financial performance: a study of Washington hospitals. Inquiry 2019;56:46958019860386. 10.1177/0046958019860386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Hospital readmissions. Available: https://www.ahrq.gov/topics/hospital-readmissions.html [Accessed 25 Sep 2020].

- 12.Bailey MK, Weiss AJ, Barrett ML. Characteristics of 30-day all-cause Hospital Readmissions,2010–2016. Statistical Brief 2006;248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein S In focus: preventing unnecessary Hospital readmissions. Available: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/focus-preventing-unnecessary-hospital-readmissions [Accessed 25 Sep 2020].

- 14.3M Health Information Systems Potentially preventable readmissions classification system: methodology overview, 2012. Available: https://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/1042610O/resources-and-references-his-2015.pdf

- 15.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. . PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim B, Weatherly C, Wolk CB, et al. . Measurement of unnecessary psychiatric readmissions: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030696. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldfield NI, McCullough EC, Hughes JS, et al. . Identifying potentially preventable readmissions. Health Care Financ Rev 2008;30:75-91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Microsoft Excel, 2020. Available: https://products.office.com/en-us/excel [Accessed 16 Aug 2020].

- 21.Gavrilets S, Auerbach J, van Vugt M. Convergence to consensus in heterogeneous groups and the emergence of informal leadership. Sci Rep 2016;6:29704. 10.1038/srep29704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baeza FLC, da Rocha NS, Fleck MPdeA. Readmission in psychiatry inpatients within a year of discharge: the role of symptoms at discharge and post-discharge care in a Brazilian sample. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2018;51:63–70. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barekatain M, Maracy MR, Rajabi F. Aftercare services for patients with severe mental disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Res Med Sci 2014;19:240–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker V, Taylor M, Kader I, et al. . Impact of crisis resolution and home treatment services on user experience and admission to psychiatric hospital. Psychiatrist 2011;35:106–10. 10.1192/pb.bp.110.031344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bastiampillai TJ, Bidargaddi NP, Dhillon RS, et al. . Implications of bed reduction in an acute psychiatric service. Med J Aust 2010;193:383–6. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03963.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernet AC Predictors of psychiatric readmission among Veterans at high risk of suicide: the impact of post-discharge aftercare. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2013;27:260–1. 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonsack C, Golay P, Gibellini Manetti S, et al. . Linking primary and secondary care after psychiatric hospitalization: comparison between transitional case management setting and routine care for common mental disorders. Front Psychiatry 2016;7:96. 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Botha UA, Coetzee M, Koen L, et al. . An attempt to stem the tide: exploring the effect of a 90-day transitional care intervention on readmissions to an acute male psychiatric unit in South Africa. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2018;32:384–9. 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burns T, Rugkåsa J, Yeeles K, et al. . Coercion in mental health: a trial of the effectiveness of community treatment orders and an investigation of informal coercion in community mental health care. Programme Grants Appl Res 2016;4:1–354. 10.3310/pgfar04210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bursac R, Raffa L, Solimo A, et al. . Boundary-Spanning care: reducing psychiatric rehospitalization and self-injury in a jail population. Journal of Correctional Health Care 2018;24:365–70. 10.1177/1078345818792055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Callaly T, Hyland M, Trauer T, et al. . Readmission to an acute psychiatric unit within 28 days of discharge: identifying those at risk. Aust. Health Review 2010;34:282 10.1071/AH08721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen R, Zhu X, Capitão LP, et al. . Psychoeducation for psychiatric inpatients following remission of a manic episode in bipolar I disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Bipolar Disord 2019;21:76–85. 10.1111/bdi.12642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clibbens N, Harrop D, Blackett S. Early discharge in acute mental health: a rapid literature review. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2018;27:1305–25. 10.1111/inm.12515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Currie LB, Patterson ML, Moniruzzaman A, et al. . Continuity of care among people experiencing homelessness and mental illness: does community follow-up reduce rehospitalization? Health Serv Res 2018;53:3400–15. 10.1111/1475-6773.12992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dixon L, Goldberg R, Iannone V, et al. . Use of a critical time intervention to promote continuity of care after psychiatric inpatient hospitalization. Psychiatr Serv 2009;60:451–8. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donisi V, Tedeschi F, Wahlbeck K, et al. . Pre-discharge factors predicting readmissions of psychiatric patients: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:449. 10.1186/s12888-016-1114-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faurholt-Jepsen M, Frost M, Martiny K, et al. . Reducing the rate and duration of Re-ADMISsions among patients with unipolar disorder and bipolar disorder using smartphone-based monitoring and treatment - the RADMIS trials: study protocol for two randomized controlled trials. Trials 2017;18:277. 10.1186/s13063-017-2015-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fullerton CA, Lin H, O'Brien PL, et al. . Intermediate services after behavioral health hospitalization: effect on rehospitalization and emergency department visits. Psychiatr Serv 2016;67:1175–82. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giacco D, Conneely M, Masoud T, et al. . Interventions for involuntary psychiatric inpatients: a systematic review. Eur Psychiatry 2018;54:41–50. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E, König S, Koebke S, et al. . Trans-Sector integrated treatment in psychosis and addiction. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2015;112:683-91. 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grinshpoon A, Lerner Y, Hornik-Lurie T. Post-Discharge contact with mental health clinics and psychiatric readmission: a 6-month follow-up study. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2011;48:262-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Habit NF, Johnson E, Edlund BJ. Appointment reminders to decrease 30-day readmission rates to inpatient psychiatric hospitals. Prof Case Manag 2018;23:70–4. 10.1097/NCM.0000000000000248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanrahan NP, Solomon P, Hurford MO. A pilot randomized control trial: testing a transitional care model for acute psychiatric conditions. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 2014;20:315-27. 10.1177/1078390314552190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hegedüs A, Kozel B, Fankhauser N, et al. . Outcomes and feasibility of the short transitional intervention in psychiatry in improving the transition from inpatient treatment to the community: a pilot study. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2018;27:571–80. 10.1111/inm.12338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hengartner MP, Passalacqua S, Andreae A, et al. . The role of perceived social support after psychiatric hospitalisation: post hoc analysis of a randomised controlled trial testing the effectiveness of a transitional intervention. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2017;63:297–306. 10.1177/0020764017700664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hengartner MP, Passalacqua S, Heim G, et al. . The post-discharge network coordination programme: a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of an intervention aimed at reducing rehospitalizations and improving mental health. Front Psychiatry 2016;7:27. 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hennemann S, Farnsteiner S, Sander L. Internet- and mobile-based aftercare and relapse prevention in mental disorders: a systematic review and recommendations for future research. Internet Interv 2018;14:1–17. 10.1016/j.invent.2018.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kidd SA, Virdee G, Mihalakakos G. The welcome basket revisited: testing the feasibility of a brief peer support intervention to facilitate transition from hospital to community. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2016;39:335–42. 10.1037/prj0000235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim HM, Pfeiffer P, Ganoczy D, et al. . Intensity of outpatient monitoring after discharge and psychiatric rehospitalization of veterans with depression. Psychiatr Serv 2011;62:1346–52. 10.1176/ps.62.11.pss6211_1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kisely SR, Campbell LA, O'Reilly R, et al. . Compulsory community and involuntary outpatient treatment for people with severe mental disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;381 10.1002/14651858.CD004408.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kolbasovsky A Reducing 30-day inpatient psychiatric recidivism and associated costs through intensive case management. Prof Case Manag 2009;14:96–105. 10.1097/NCM.0b013e31819e026a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lay B, Drack T, Bleiker M, et al. . Preventing Compulsory Admission to Psychiatric Inpatient Care: Perceived Coercion, Empowerment, and Self-Reported Mental Health Functioning after 12 Months of Preventive Monitoring. Front Psychiatry 2015;6 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lay B, Salize HJ, Dressing H, et al. . Preventing compulsory admission to psychiatric inpatient care through psycho-education and crisis focused monitoring. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12 10.1186/1471-244X-12-136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee CC, Liem SK, Leung J, et al. . From deinstitutionalization to recovery-oriented assertive community treatment in Hong Kong: what we have achieved. Psychiatry Res 2015;228:243–50. 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liem SK, Lee CC. Effectiveness of assertive community treatment in Hong Kong among patients with frequent hospital admissions. Psychiatr Serv 2013;64:1170–2. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mattei G, Raisi F, Burattini M. Effectiveness and acceptability of psycho-education group intervention for people hospitalized in psychiatric wards and nurses. J Psychopathol 2017;23. [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDonagh JG, Haren WB, Valvano M, et al. . Cultural change: implementation of a recovery program in a Veterans health administration medical center inpatient unit. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 2019;25:208–17. 10.1177/1078390318786024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nubukpo P, Girard M, Sengelen J-M, et al. . A prospective hospital study of alcohol use disorders, comorbid psychiatric conditions and withdrawal prognosis. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2016;15 10.1186/s12991-016-0111-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ortiz G Predictors of 30-day postdischarge readmission to a multistate national sample of state psychiatric hospitals. J Healthc Qual 2019;41:228–36. 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Passley-Clarke J Implementation of recovery education on an inpatient psychiatric unit. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 2019;25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pérez GAC, Bernal LAR, Silva JB. Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with dual disorders in a psychiatric hospital. Salud Ment 2017;40. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prochaska JJ, Hall SE, Delucchi K, et al. . Efficacy of initiating tobacco dependence treatment in inpatient psychiatry: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health 2014;104:1557–65. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rabovsky K, Trombini M, Allemann D, et al. . Efficacy of bifocal diagnosis-independent group psychoeducation in severe psychiatric disorders: results from a randomized controlled trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2012;262:431–40. 10.1007/s00406-012-0291-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roos E, Bjerkeset O, Steinsbekk A. Health care utilization and cost after discharge from a mental health Hospital; an RCT comparing community residential aftercare and treatment as usual. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18 10.1186/s12888-018-1941-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rothbard AB, Chhatre S, Zubritsky C, et al. . Effectiveness of a high end users program for persons with psychiatric disorders. Community Ment Health J 2012;48:598–603. 10.1007/s10597-012-9479-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rowley E, Wright N, Waring J, et al. . Protocol for an exploration of knowledge sharing for improved discharge from a mental health ward. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005176. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shimada T, Nishi A, Yoshida T, et al. . Factors influencing Rehospitalisation of patients with schizophrenia in Japan: a 1-year longitudinal study. Hong Kong J Occup Ther 2016;28:7–14. 10.1016/j.hkjot.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simpson A, Flood C, Rowe J, et al. . Results of a pilot randomised controlled trial to measure the clinical and cost effectiveness of peer support in increasing hope and quality of life in mental health patients discharged from hospital in the UK. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14 10.1186/1471-244X-14-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sledge WH, Lawless M, Sells D, et al. . Effectiveness of peer support in reducing readmissions of persons with multiple psychiatric hospitalizations. Psychiatr Serv 2011;62:541–4. 10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sloan PA, Asghar-Ali A, Teague A. Psychiatric hospitalists and continuity of care: a comparison of two models. J Psychiatr Pract 2010;16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Taylor C, Holsinger B, Flanagan JV, et al. . Effectiveness of a brief care management intervention for reducing psychiatric hospitalization readmissions. J Behav Health Serv Res 2016;43:262–71. 10.1007/s11414-014-9400-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thambyrajah V, Hendriks M, Mahendran R. Evaluating a case management service in a tertiary psychiatric hospital in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2014;43. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thomas KA, Rickwood D. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of acute and subacute residential mental health services: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv 2013;64:1140–9. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tomita A, Lukens EP, Herman DB. Mediation analysis of critical time intervention for persons living with serious mental illnesses: assessing the role of family relations in reducing psychiatric rehospitalization. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2014;37:4–10. 10.1037/prj0000015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tomko JR, Ahmed N, Mukherjee K, et al. . Evaluation of a discharge medication service on an acute psychiatric unit. Hosp Pharm 2013;48:314–20. 10.1310/hpj4804-314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Välimäki M, Kannisto KA, Vahlberg T, et al. . Short text messages to encourage adherence to medication and follow-up for people with psychosis (mobile.net): randomized controlled trial in Finland. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e245 10.2196/jmir.7028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Videbech P, Deleuran A. The Danish depression database. Clin. Epidemiol 2016;8:475–8. 10.2147/CLEP.S100298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vigod SN, Kurdyak PA, Dennis C-L, et al. . Transitional interventions to reduce early psychiatric readmissions in adults: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2013;202:187–94. 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.115030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vijayaraghavan M, Messer K, Xu Z, et al. . Psychiatric readmissions in a community-based sample of patients with mental disorders. PS 2015;66:551–4. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wong CYT Predictors of psychiatric rehospitalization among elderly patients. F1000Research 2015;4:926–14. 10.12688/f1000research.7135.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xiao J, Mi W, Li L. High relapse rate and poor medication adherence in the chinese population with schizophrenia: Results from an observational survey in the people’s Republic of China. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2015;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yates KF, Kunz M, Khan A, et al. . Psychiatric patients with histories of aggression and crime five years after discharge from a cognitive-behavioral program. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 2010;21:167–88. 10.1080/14789940903174238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zisman-Ilani Y, Roe D, Elwyn G, et al. . Shared decision making for psychiatric rehabilitation services before discharge from psychiatric hospitals. Health Commun 2019;34:631–7. 10.1080/10410236.2018.1431018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zuehlke JB, Kotecki RM, Kern S, et al. . Transformation to a recovery-oriented model of care on a Veterans administration inpatient unit. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2016;39:361–3. 10.1037/prj0000198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Burke RE, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. . Moving beyond readmission penalties: creating an ideal process to improve transitional care. J Hosp Med 2013;8:102–9. 10.1002/jhm.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-045364supp001.pdf (98KB, pdf)