Abstract

Brain contusions (BCs) are one of the most frequent lesions in patients with moderate and severe traumatic brain injury (TBI). BCs increase their volume due to peri-lesional edema formation and/or hemorrhagic transformation. This may have deleterious consequences and its mechanisms are still poorly understood. We previously identified de novo upregulation sulfonylurea receptor (SUR) 1, the regulatory subunit of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels and other channels, in human BCs. Our aim here was to study the expression of the pore-forming subunit of KATP, Kir6.2, in human BCs, and identify its localization in different cell types. Protein levels of Kir6.2 were detected by western blot (WB) from 33 contusion specimens obtained from 32 TBI patients aged 14–74 years. The evaluation of Kir6.2 expression in different cell types was performed by immunofluorescence in 29 contusion samples obtained from 28 patients with a median age of 42 years. Control samples were obtained from limited brain resections performed to access extra-axial skull base tumors or intraventricular lesions. Contusion specimens showed an increase of Kir6.2 expression in comparison with controls. Regarding cellular location of Kir6.2, there was no expression of this channel subunit in blood vessels, either in control samples or in contusions. The expression of Kir6.2 in neurons and microglia was also analyzed, but the observed differences were not statistically significant. However, a significant increase of Kir6.2 was found in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive cells in contusion specimens. Our data suggest that further research on SUR1-regulated ionic channels may lead to a better understanding of key mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of BCs, and may identify novel targeted therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: brain contusion, brain edema, human, Kir6.2, SUR1

Introduction

Brain contusions (BCs) are one of the most frequent focal primary lesions in patients with moderate and severe traumatic brain injury (TBI).1 In more than 50% of TBI patients with BCs, contusions increase their volume as a result of an increase in water content in the core of the lesion, edema formation in the peri-lesional area, and/or hemorrhagic progression.2,3 The volume increase of BCs is the cause of neurological worsening and in some patients requires craniotomy for mass evacuation to avoid brain herniation and death. One major goal of current TBI research is a better understanding of the molecular pathophysiology of the BC-induced edema and its hemorrhagic progression to avoid the neurological deterioration related to these still poorly understood lesions.

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels—first discovered by Noma in 1983 in the cardiomyocytes of guinea pigs and rabbits4—are a collection of structurally distinct channels that couple cell energetic status with electrophysiological membrane potential.5 In mammals, KATP channels are expressed in a variety of excitable and endocrine tissues, including cardiomyocytes, pancreatic β-cells, skeletal and smooth muscle, kidney, pituitary, placenta, and brain.5–7 KATP channels are hetero-octameric complexes with four pore-forming, inwardly rectifying potassium channel subunits (Kir6.1 or Kir6.2) and four regulatory sulfonylurea receptor (SUR) subunits (SUR1, SUR2A, or SUR2B).8 KATP channels expressed in the mammalian brain have the same structure as the pancreatic β-cell channels—an SUR1 regulatory subunit and a Kir6.2 pore-forming subunit9—but their functions are still poorly understood. The activation of KATP channels in the setting of energy failure, both in the myocardium and the brain, results in cell hyperpolarization and vasodilation, and has cardio- and neuroprotective effects.10–12

Paradoxically, experimental evidence has accumulated that in acute lesions of the central nervous system (CNS) such as spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage, stroke, TBI, and spinal cord injury, the SURs and specifically SUR1—the regulatory subunit of pancreatic and neuronal KATP channels—are involved in the generation and propagation of ischemic and contusion-induced brain edema and in the hemorrhagic conversion of ischemic stroke and BCs.2,13 SURs are not directly involved in ionic transport but must associate with pore-forming subunits to form transmembrane cation channels.13,14 Therefore, the deleterious effects of SUR1-overexpression or the beneficial effects of its pharmacological modulation are associated with the pore-forming subunit it regulates, not with the SUR subunit by itself.

Simard's group has shown that SUR1 is also the regulatory subunit of a non-constitutive channel formed with transient receptor potential melastatin 4 (TRPM4).15–17 The SUR1-TRMP4 channel, described by Chen and Simard in 2001,17 is a non-selective ATP- and calcium-sensitive monovalent cation channel that facilitates Na+ entry into cells and triggers cell depolarization, cerebral vasoconstriction, and brain edema. Upregulation of SUR1-TRPM4 in brain tissue including endothelial cells, astrocytes, and neurons, results in necrotic cell death and promotes brain edema by initiating cytotoxic edema, the driver of all other forms of brain edema, such as ionic or vasogenic edema.13,17–22 Recently, our group showed SUR1 overexpression in human BCs and that SUR1 was significantly overexpressed in all types of brain cells, but particularly in neurons, glia, and endothelial cells.23 Kurland and colleagues suggested that in TBI, the endothelial cells of microvessels that are not disrupted at the time of injury receive kinetic energy that initiates a series of molecular events that results in their structural failure and fragmentation, which contributes to the secondary hemorrhagic progression of BCs.2 Brain edema and the extravasated blood are extremely toxic to the brain and initiate a strong neuroinflammatory response that is the starting point of a deleterious circle that adds further secondary damage to the already-established primary brain injury.

The clinical relevance of the SUR association with pore-forming subunits is that SUR1 can be modulated by drugs that interact with it and thus influence the opened-closed status of its regulated channels. KATP channels in any tissue are inhibited by sulfonylureas and are activated by channel-opening drugs, such as diazoxide, pinacidil, or nicorandil.9,24 Pre-clinical evidence and a recently finished Phase II clinical trial have shown that glibenclamide, a second-generation sulfonylurea used in diabetic patients,25 significantly reduces brain edema and mass effect in large middle cerebral artery ischemic stroke.26,27 By inhibiting SUR1-TRPM4 channels, glibenclamide reduced brain swelling and death and was associated with better neurological outcomes than treatment with decompressive craniectomy in a rat model of severe ischemia/reperfusion.26

In studying the SUR1-TRPM4 channel in human BCs, by serendipity, we found that the pore-forming subunit Kir6.2 was also expressed in BC specimens. Because SUR1 is the regulatory subunit for both TRMP4 and Kir6.2, and because glibenclamide protects the brain from ischemic swelling, it seemed that their function was contradictory to the role that SUR1-TRPM4 plays in the generation of brain edema and in the “microvascular failure” phenomenon in BCs.2 Our aim in this article was to study Kir6.2 in human BC specimens, including its expression and localization in different cell types, to obtain a better understanding of the role of this subunit in TBI and the potential role of the SUR1-Kir6.2 channel in the pathophysiology of TBI. Here we show that the Kir6.2 pore-forming subunit is significantly overexpressed in the astrocytes of human BC specimens, and we speculate about Kir6.2's potential role in the pathophysiology of BCs and its exploitation as a potential pharmacological target in TBI.

Methods

Clinical material and methods

This prospective study included all TBI patients who had an initial computed tomography (CT) scan and underwent surgical evacuation of their BCs at our institution between January 2006 and July 2015. The brain specimens were obtained from surgically resected areas of the BCs that were stored in a biobank collection of TBI specimens at our institution (registration number C0002524 at the Carlos III Institute). The mean contusion volume at the time of evacuation was determined using the ABC/2 method.28 As suggested by Iaccarino and co-workers, in patients with more than one lesion, the volume of each contusion was calculated and then added to get a total contusion volume.1 The clinical outcome for each patient was assessed 6 months after the injury, using the Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOSE), by an independent neuropsychologist blinded to the immunolabeling and western blot (WB) data.

The control group included tissue specimens obtained from limited brain resections of macroscopically normal brain, which were performed to access extra-axial skull base tumors or intraventricular lesions. These samples were included if the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans did not show any abnormalities in T1-weighted, T2-weighted, or fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. Our research was carried out in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research of the Declaration of Helsinki.29 This study and the tissue collection protocol were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Vall d'Hebron University Hospital (protocols PR-ATR-68/2007 and PR-ATR-286/2013) and written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients (including the controls) or the patient's legally authorized representative.

Criteria for surgical evacuation of brain contusions

At our institution, patients must fulfill at least one of the following criteria to be considered for surgical evacuation: (1) for patients with intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring, the ICP exceeds 20 mm Hg and the total volume of a single contusion or multiple contusions exceeds the 25-mL threshold; (2) for patients without ICP monitoring (mostly moderate TBI), the total contusion volume (hemorrhagic and edematous components) is above the 25-mL threshold; (3) any temporal contusion that produces a significant mass effect and/or compresses the basal cisterns; and (4) contusions that induce a significant midline shift (> 5 mm) despite having an ICP <20 mm Hg. The surgical approach in non-eloquent brain areas is usually excision of the necrotic tissue with variable margins but without external bone decompression.

Brain tissue collection

After surgical resection, all of the specimens were immediately transported to the laboratory on ice. Using dissection material and phosphate buffer (0.2 M), the cauterized and necrotic zones of the resected tissues were removed; excess blood and hematomas were also eliminated. Samples (the minimum size was 5 mm3) were obtained from the processed tissue. The specimens with preserved anatomical structures were selected from areas of the resected tissue, corresponding to penumbral zones or the interface of the penumbra/core using the terminology described by Kurland and associates.2 The surgical samples were processed following different protocols. For WB analysis, specimens were rapidly frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until analysis. For immunohistochemistry, samples were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 48 h and cryoprotected using 30% sucrose solution. After cryoprotection, the specimens were embedded in Tissue-Tek optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (OCT 4583; Sakura Finetek Europe B.V., Alphen aan den Rin, The Netherlands) and frozen on dry ice. From these blocks, 10-μm-thick sections were obtained using a cryostat (Leica CM3050 S; Leica Biosystems, Heidelberg, Germany), mounted on glass slides, and stored at −20°C until further analysis.

The MRI images of all controls were independently assessed by two of the authors (JS and JMS), who were blinded to the immunolabeling data. The tissue quality was evaluated in the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections by a neuropathologist (EMS), who was blinded to the immunolabeling data, using one scale for edema and another for signs of tissue hypoxia/ischemia (0: absent, 1: mild, 2: moderate, or 3: severe). The patients with edema and/or ischemia scores >2 were excluded as controls.

Western blot

Protein extracts were homogenized by tissue lysis via sonication in ice-cold RIPA buffer (R0278; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). To avoid protein degradation, proteases were inhibited by a protease inhibitor cocktail (11697498001; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). After homogenization, samples were put on ice for 20 min and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The pellet was discarded and the supernatant was used to quantify the protein concentration by the Bradford's method30 using bovine serum albumin as the standard (A2153; Sigma-Aldrich). Once the concentration was determined, 15 μg of denatured protein (5 min at 100°C) from each sample were loaded on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, separated electrophoretically, and transferred in a tank filled in with 1x running buffer (Tris/Glycine/SDS; 161073; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. A standard molecular weight marker (Precision Plus Protein Standards-Dual Color; Bio-Rad) was included in a separate lane. The transferred membrane was incubated at 4°C overnight in blocking solution with a primary antibody (rabbit anti-Kir6.2 at 1:10,000; APC-020; Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel). Blocking solution was composed of 5% skimmed milk powder and Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-Tween-20; P9416; Sigma-Aldrich). Alomone's APC-020 is an affinity purified, polyclonal rabbit antibody raised against amino acid sequence 372-385 of rat Kir6.2, which is homologous to human Kir6.2. After washing in TBS-Tween-20 the horseradish peroxidase-labeled species-appropriate secondary antibody (A0545; Sigma-Aldrich) was applied at a dilution of 1:2000 for 1 h. The blot was washed again in TBS-Tween-20 and then positive signals were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (RPN2232; Amersham Biosciences, Bucks, UK) and detected by a 30-sec exposure to radiographic films. The relative optical density of the resulting bands was determined by Quantity One 1-D Analysis Software v4.6.6 (Bio-Rad) and, for quantification, was normalized to the β-actin loading control. We tested whether there were some significant differences between β-actin concentration in contusion (optical density units; median: 1.2x1011; min-max: 0.6 to 30.4x1011) and controls (optical density units; median: 1.3x1011; min-max: 1.2 to 1.8x1011). The differences in actin concentration observed between contusions and controls were not statistically significant (Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon test, p = 0.11).

Immunohistochemistry

Before immunolabeling, to reduce autofluorescence, the samples were pre-treated by immersing the 10-μm-thick sample sections for 7 min in 0.1% sodium borohydride (NaBH4) diluted in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).31 After this treatment, sections were incubated in a blocking solution containing 4% donkey serum (D9663; Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.2% Triton-X (T8787; Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in PBS for 1 h and then overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies indicated in Table 1. Fluorescent-labeled, species-appropriate secondary antibodies (also indicated in Table 1) were used for signal visualization. The omission of primary antibodies was used as a negative control. Sections were cover-slipped with polar mounting medium containing anti-fade reagent and the nuclear dye 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; P36935; Invitrogen). Fluorescent signals were visualized using an epifluorescence microscope (BX61Olympus; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Table 1.

Antibodies Used for Immunohistochemistry

| Primary antibody | Dilution | Supplier | Secondary antibody | Dilution | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rabbit anti-Kir6.2; APC-020 | 1:300 | Alomone Labs | AlexaFluor® 568; A10042 | 1:400 | Invitrogen |

| Goat anti-Kir6.2; sc-11228 | 1:50 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | AlexaFluor® 488; A11055 | 1:400 | Invitrogen |

| Mouse anti-NeuN; MAB377 | 1:100 | Millipore Corporation | AlexaFluor® 488; A21202 | 1:400 | Invitrogen |

| Mouse anti-GFAP; C-9205, CY3 conjugated | 1:3000 | Sigma-Aldrich | – | - | - |

| Mouse anti-Iba; 174429658 | 1:100 | Thermo Fisher | AlexaFluor® 488; A21202 | 1:400 | Invitrogen |

| Mouse anti-CD31; M0823 | 1:100 | Dako | AlexaFluor® 488; A21202 | 1:400 | Invitrogen |

Antibody validation

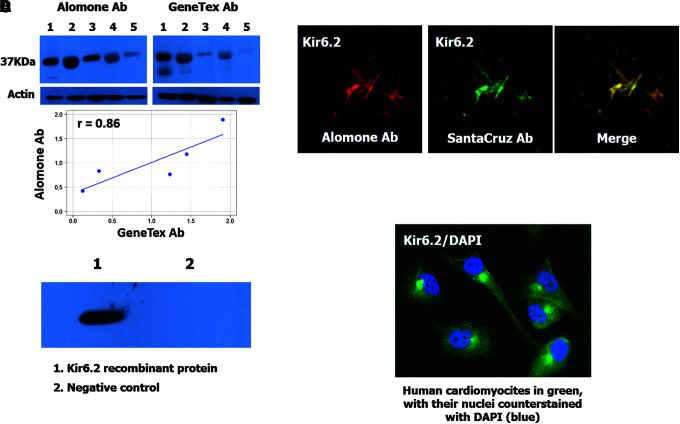

To avoid reproducibility problems, we validated our Kir6.2 antibody with some of the independent antibody strategies proposed by Uhlen and associates.32 As a first step, we conducted a comparative analysis between our antibody (APC-020; Alomone Labs) and a second one recognizing a different Kir6.2 epitope (GTX80493; GeneTex, CA). We performed a WB with both antibodies in the same specimens and compared the expression of Kir6.2 by the Pearson correlation coefficient (R = 0.88, p = 0.049) as shown in Figure 1A. As a second validation method, we tested our antibody (APC-020; Alomone Labs) by immunofluorescence using a second antibody against Kir6.2 (G-16; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). We looked for an overlapping distribution of both antibodies, as shown in Figure 1B, to ensure accuracy. As the third validation method, we performed a WB using a fragment (amino acids 301 to 390) of the recombinant human Kir6.2 protein (ab114436; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) to demonstrate that Alomone's antibody recognized recombinant human Kir6.2 protein. A second recombinant protein of GFP (ab134853; Abcam) was used as a negative control. For this test, 1 μg of protein was loaded per lane onto a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane that was incubated with the primary antibody from Alomone Labs at a 1:1000 dilution; the secondary antibody was applied at 1:2000. Positive signals were detected by a 1-min exposure to radiographic film. The results show that our antibody recognized the recombinant protein but not the tags, as shown in Figure 1C. Finally, to have a positive control, we decided to show the expression of Kir6.2 in a cell line of human cardiomyocytes (ScienCell Research Laboratories, San Diego, CA), because these cells express Kir6.2 constitutively.9,33 As shown in Figure 1D, the cardiomyocytes were strongly positive for Kir6.2.

FIG. 1.

Antibody validation. (A) Upper images show the result of a western blot analysis of human Kir6.2 in five specimens of human brain tissue (lanes 1 to 5: 2, 4 corresponding to contusion specimens and 1, 3, 5 corresponding to healthy tissue) using two independent antibodies (Alomone Ab and GeneTex Ab). The bar graphs are shown as a visual aid for the inmunoblot results. Optical density with both antibodies was compared and resulted in a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.88 (p = 0.049). The scatterplot is shown as a visual aid to the immunoblot results. (B) Fluorescence labeling of Kir6.2 using Alomone Ab (red) and SantaCruz Ab (green); merged images in yellow. (C) Western blot analysis of a human recombinant Kir6.2 protein (ab114436; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) (1) tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) and GFP recombinant protein (2) used as a negative control. (D) Kir6.2 expression (green) in a cell line of human cardiomyocytes (P10451; Innoprot, Derio, Spain) used as a positive control. Nuclei were counterstained with 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Cross-reactivity between Kir6.2 and Kir6.1

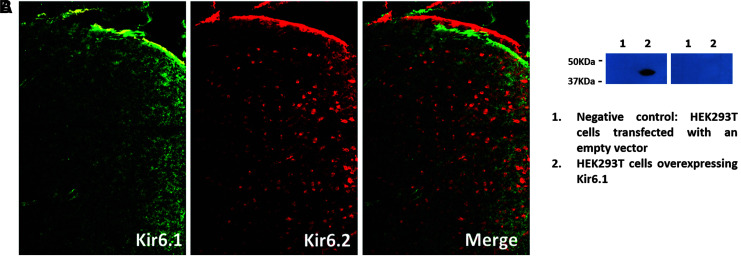

To demonstrate that our Kir6.2 antibody (APC-020; Alomone Labs) was not binding to Kir6.1, we conducted immunofluorescence labeling using our Kir6.2 antibody and a Kir6.1 antibody (APC-105; Alomone Labs) in adjacent sections of a mouse brain sample. The rationale for using mouse brain tissue is that Kir6.2 and Kir6.1 are compartmentalized in mouse brain (Kir6.2 expression is mostly located in neurons and Kir6.1 in astrocytes).34 We took immunofluorescence images from the same region of our samples using an epifluorescence microscope (BX61, Olympus), and we observed that Kir6.1 and Kir6.2 were labeling different zones and cells. Kir6.2 was restricted to neuronal structures, and Kir6.1 was restricted to blood vessels. Thus, the Kir6.2 antibody does not cross-react with the Kir6.1 epitope.

We also performed an experiment with a lysate of HEK293T cells that overexpress only Kir6.1 (NBL1-12174; Novus Biological, Littleton, CO) but not Kir6.2, to confirm that our antibody was not cross-reacting also with Kir6.1. We simultaneously ran two WBs where 15 μg of the lysate was loaded onto a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane. As negative controls, we used HEK293T cells transfected with an empty vector. One of the membranes was incubated with our Kir6.2 antibody at a 1:10,000 dilution and the other one with the Kir6.1 antibody at a 1:200 dilution as recommended by the manufacturer. Both secondary antibodies were applied at a 1:2000 dilution. Signals were detected by exposing the membranes to radiographic films for 1 min. The results obtained showed that only the Kir6.1 antibody was detecting the HEK293T-cells lysate, as is shown in Figure 2B.

FIG. 2.

Cross-reactivity Kir6.2-Kir6.1. (A) Staining of Kir6.1 (green; APC-105; Alomone Labs) and Kir6.2 (red; APC-020; Alomone Labs) in the same section of mouse brain tissue. Kir6.1 shows labeling in blood vessel-like structures and Kir6.2 in neuronal-like structures. This shows that the Kir6.2 antibody does not cross-react with the Kir6.1 epitope. (B) Western blot analysis of a lysate of HEK293T-cells transfected with an empty vector (lane 1) and HEK293T cells that overexpress Kir6.1 (NBL1-12174; Novus Biological, Littleton, CO) (lane 2). The membrane shown on the left was incubated with an anti-Kir6.1 antibody and the one on the right with an anti-Kir6.2 antibody. Only the Kir6.1 antibody was detecting the HEK293T-cells lysate showing that cross-reactivity does not occur between the Kir6.2 antibody and the Kir6.1 epitope.

Analysis of immunohistochemical findings

Quantitative immunohistochemical analysis in neurons and endothelial cells

To calculate the number of Kir6.2-positive neurons and vessels, 4–8 captured 440x330 μm2 images from the cortex were taken by the investigator with an epifluorescence microscope (BX61, Olympus) using DAPI as a guide. All images were quantified using the plug-in Cell Counter (Kurt De Vos; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/plugins/cell-counter.html) of the Image J program, v1.47 (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). This plug-in allows counting cells manually. The investigator clicks in the cell image and this method marks the cell with a colored square and adds the cell to a tally sheet. The percentage of Kir6.2-positive cells was calculated from the total number of neurons and blood vessels (NeuN/CD31-positive).

Semi-quantitative immunohistochemical analysis in astrocytes and microglia

To evaluate whether Kir6.2 was expressed in these cells, specific antibodies were used (anti-GFAP and anti-Iba1, respectively). The whole section was quantified by two independent observers using a semi-quantitative scale to count: (1) the different cell types (0: absent; 1: scanty; 2: moderate; or 3: numerous) and (2) the Kir6.2-positive cells of each type (0: none; 1: in a few cells; 2: in many cells; or 3: in all or almost all cells). The inter-observer agreement (weighted kappa) was 0.83 (min: 0.78, max: 0.94). The statistical analysis was conducted using the average of the assigned scores from the two independent observers. To facilitate data interpretation, an example of the quantification in different cell types is shown in Supplementary Figure 1 (see online supplementary material at http://www.liebertpub.com).

Controls

The tissue quality was evaluated in the H&E-stained sections by a neuropathologist (EMS), who was blinded to the immunolabeling data, using one scale for edema and another for signs of tissue hypoxia/ischemia (0: absent, 1: mild, 2: moderate, or 3: severe). The patients with edema and/or ischemia scores >2 were excluded as controls.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained for each variable. For continuous variables, the mean, median, range, and standard deviation were used for normally distributed data and the median, minimum, and maximum values were used for non-Gaussian distributions. The Shapiro-Wilk test and the inverse probability plot were used to test whether the data followed a normal distribution. The percentages and sample sizes were used to summarize the categorical variables. To correlate two continuous variables, the Pearson correlation test was used for data that followed a normal distribution and the more conservative Spearman's rho was used if the data did not follow a normal distribution. For each marker, scatter plots were constructed with time as the abscissa and the percentage/score of positive immunolabeling as the ordinate. A simple linear regression and the ordinary least squares (OLS) method were used. Adjusted R2 values were calculated for all of the models to test whether the linear or non-linear models adequately explained the relationships between both variables. The statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft R Open (version 3.4.2) and the integrated development environment R Studio (version 1.1.383).35 The car package was used for regression analysis.36 To calculate the inter-observer agreement between the two independent observers using the immunolabeling ordinal scales, we used weighted kappa with the routine implemented in MedCalc version 12.2 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). Statistical significance was considered when p ≤ 0.05. Data are presented graphically using box-and-whisker plots.

Results

Small differences regarding the number of control and contusion samples in the different techniques used for the quantification of Kir6.2 are due to the different number of samples obtained from individual patients. When the samples were large enough, they could be processed for immunoblots and for immunochemistry. However, when the samples were small they could only be processed for one of these techniques.

Descriptive data of patients with contusions

Forty-three contusion specimens were obtained from 42 TBI patients (30 males and 13 females) with a median age of 48 years (min: 14, max: 74 years). The lack of coincidence between number of specimens and samples is due to the fact that we have collected two samples from one single patient—one from the frontal and a second one from the temporal lobe—however, the other specimens each correspond one to one patient. Samples were obtained at a median time post-injury of 23 h (min: 5, max: 246 h). The median contusion volume evaluated by CT was 44 mL (min: 13, max: 170 mL). On admission, 21 patients (49%) scored above 9 on the Glasgow Coma Score scale and were thus included in the moderate TBI category. Mortality was 7% in this cohort. The median GOSE of the survivors assessed at 6 months after injury was heterogeneous (median, 3; range, 1–8). The small sample size was not powered for conducting a robust statistical analysis to study the possible relationship between contusion volume, neurological outcome, and Kir6.2 expression.

Control group

Six control specimens were used. The reduced number of control specimens was due to the exclusion of some of them because of pathological evidence of edema and/or ischemia that could have been caused by the manipulation of tissues during surgery, suboptimal conditions during transport of the samples to the laboratory, or the pre-existence of pathology not detectable by MRI. Also the variability in the number of controls used for different techniques is due to the different sizes of resected tissues, as explained previously. Demographic data for the 6 control subjects are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Data for Control Patients

| Tissue quality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Age | Sex | Primary pathology | Edema | Ischemia |

| 1 | 57 | F | Meningothelial meningioma | 0 | 2 |

| 2 | 59 | F | Psammomatous meningioma | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 31 | F | Facial shwannoma | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 | M | Rhabdoid tumor | 1 | 2 |

| 5 | 66 | M | Epidermoid cyst | 1 | 2 |

| 6 | 25 | F | Left temporal lobe lesion | 1 | 0 |

Tissue quality scores (edema and ischemia): 0: absent; 1: mild; 2: moderate; and 3: severe.

F, female; M, male.

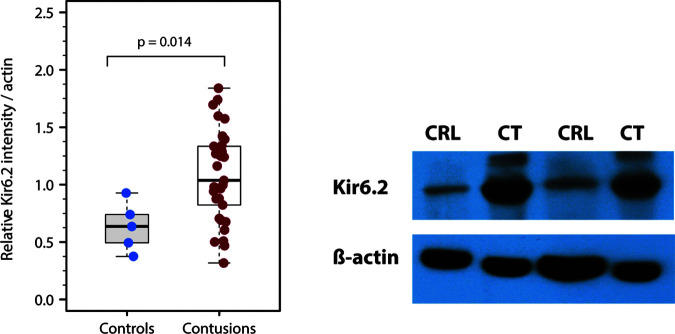

Kir6.2 pore-forming subunit is increased in brain contusions

Kir6.2 levels were evaluated by WB in 33 contusion specimens obtained from 32 TBI patients (21 males and 11 females) ages between 14 and 74 years (median: 49 years). The results were compared with 5 control specimens (cases, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 in Table 2). On average, Kir6.2 expression, expressed as optical density units, was significantly increased in contusions (median: 1.03; min: 0.32, max: 1.84) compared with controls (median: 0.64; min: 0.38, max: 0.93) (Wilcoxon rank sum test; p = 0.014) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Kir6.2 protein levels in control and contusion samples. (A) Box plots of Kir6.2 relative intensity in control and contusion samples, showing a significant increase of Kir6.2 expression (p = 0.014) in contusion specimens; data normalized to β-actin loading controls. (B) Representative image of a western blot showing a clear difference between control and contusion samples.

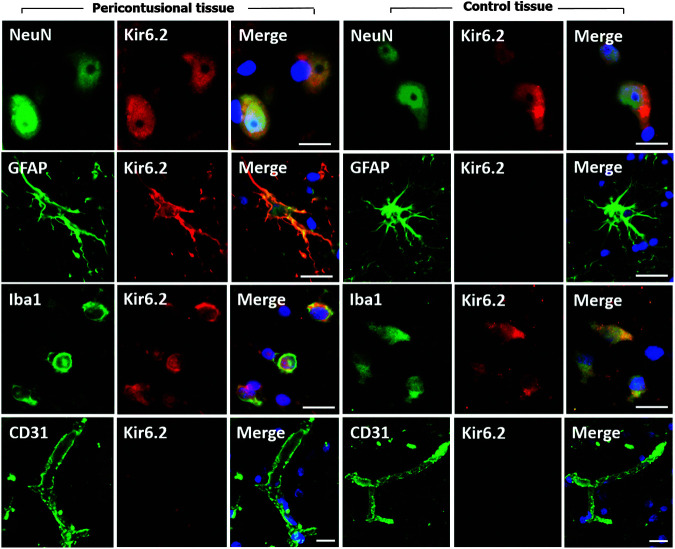

Kir6.2 expression in different cell types

The expression of the channel subunit was studied by immunofluorescence in 29 contusion specimens from 28 patients (23 males and 5 females) with a median age of 42 years (min: 14, max: 74 years) and in four controls (cases, 2 to 5 of Table 2). In Figure 4, a montage of the immunofluorescence for the different cell types is shown.

FIG. 4.

Expression of Kir6.2 in different cell types. The first three columns of the montage show Kir6.2 expression in different cell types of the peri-contusional tissue and the last three show Kir6.2 expression in control tissue. Peri-contusional tissue: fluorescent double labeling for NeuN/ glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)/Iba1/CD31 (green) and Kir6.2 (red). Merged images are presented in the third column. Control tissue: fluorescent double labeling for NeuN/GFAP/Iba1/CD31 (green) and Kir6.2 (red). Merged images are presented in the last column. In controls, the Kir6.2 expression was evident in neurons and microglia but was minimal in astrocytes (GFAP-positive cells). Original magnification = 100x. Scale: 20 μm. Nuclei were counterstained with 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Neurons

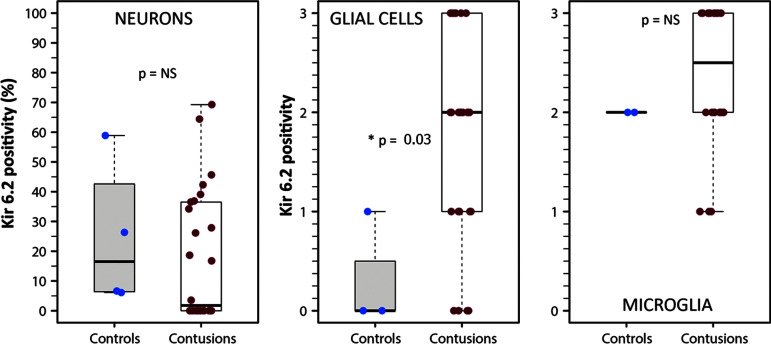

The median percentage of Kir6.2-positive neurons in controls was 16.5% (min: 6.1%, max: 59.0%) and 1.8% in contusions (min: 0%, max: 69.3%) (Fig. 5A). However, the observed differences were not statistically significant (Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon test, p = 0.293). Fifty percent of the controls showed Kir6.2-positive neurons. In contusions, 13 specimens (also 50%) exhibited Kir6.2-positive neurons but in 13 specimens, Kir6.2 was not observed.

FIG. 5.

Kir6.2 expression in neurons, glial cells, and microglia. From left to right, representative box plots of Kir6.2 expression in neurons (percentage), in glial cells, and microglia (semi-quantitative scale from 0 to 3). The results show a significantly increased expression of Kir6.2 in glial cells from contusion samples (Wilcoxon rank sum test; p = 0.03), but non-significant differences in neurons and microglia. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*p ≤ 0.05).

Endothelial cells

We did not find expression of Kir6.2 in blood vessels, either in control samples or in contusion specimens. For this reason, we did not quantify Kir6.2 expression for this cell type.

Glial cells

In 1 control and 4 of the 29 contusion specimens, we did not observe GFAP-positive cells, and therefore these specimens were excluded from the semi-quantitative analysis. In the GFAP-positive cells, control specimens showed very low Kir6.2 expression (median: 0.5; min: 0, max: 1) (Fig. 5B). A significant increase in Kir6.2 density was found in GFAP-positive cells in contusion specimens (median: 2; min: 0, max: 3). These differences were statistically significant (Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon test, p = 0.03). However, as shown in Figure 5B, a wide variability in Kir6.2 expression was found among GFAP-positive cells. The plot of time versus the number of Kir6.2-positive glial cells (data not shown) did not show any correlation between Kir6.2-positive cells and the time when contusion was surgically evacuated (Spearman rho = 0.1, p = 0.60).

Microglia

In 2 of the 4 controls and 7 of the 29 contusion specimens, we did not observe Iba1-positive cells, and therefore these specimens were excluded from the analysis. In the two controls with Iba1-positive cells, the median density for Kir6.2 was 2 compared with a non-significant increase to 2.25 (min: 1, max: 3) in contusion specimens (Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon test, p = 0.29) (Fig. 5C). The scatterplot of time versus percentage of Kir6.2-positive microglia (data not shown) did not show any linear (Spearman rho = 0.01, p = 0.95) or non-linear correlation between Kir6.2-positive cells and time from injury to the surgically evacuation.

Discussion

Because of its frequency and associated morbidity, BCs remains a serious clinical problem. BCs evolve with time and most of the neurological damage they inflict is a consequence of their increase in volume in the first hours after TBI. The basic mechanisms underlying the growth of posttraumatic BCs—by either cerebral edema and/or hemorrhagic progression—is complex and involves many interrelated phenomena and biochemical cascades such as alterations in regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) and in all the components of the multi-cellular neurovascular unit: endothelial cells, neurons, astrocytes, pericytes, and microglia. BCs induce a variable degree of alteration in the blood–brain barrier (BBB) with the consequent increase in permeability to ions at an early stage and protein extravasation and hemorrhagic transformation in later stages.2 In addition, the contusion “core”—mainly necrotic brain with blood—induces in the peri-contusional tissue a strong neuroinflammatory response that elicits the release of pro-inflammatory molecules and early upregulation of both systemic and brain gelatinases, proteases that degrade the extracellular matrix and the basement membrane and that are directly implicated in the disruption of the BBB, and in the production of brain swelling after human TBI.37 Emerging evidence has shown that there are important molecular players involved in the progression of BCs and, among them, dysregulation of cation channels and their regulatory subunits play a crucial role.2,23 In a series of pivotal studies, Kurland and co-workers have shown that SUR1-TRPM4 channels contribute to brain edema and to the phenomenon of “microvascular failure” that explains the hemorrhagic increase observed in BCs.2 In experimental and clinical studies of ischemic stroke, blockade of the SUR1 regulatory subunit by sulfonylureas consistently reduces ischemia-induced brain edema and swelling,26,38,39 whereas Kir6.2 and SUR1 null mice are extremely vulnerable to brain hypoxia and exhibit a reduced threshold for hypoxia-induced generalized seizures.10

Kir6.2-pore forming subunit is selectively overexpressed in astrocytes

Our data show that the pore-forming subunit Kir6.2 is overexpressed in BCs and that its expression is weak in neurons, strong in astrocytes (GFAP-positive cells), moderately increased in microglia, and non-detectable in endothelial cells. Because, in most of our specimens, necrotic tissue was excluded from analysis, and analysis was conducted in structurally preserved brain, the overexpression of Kir6.2 is prominent in what has been called by Kurland and colleagues peri-contusional “penumbra.”2 In astrocytes, Kir6.2 was apparently localized not only in the membrane but was observed in the cytoplasm of GFAP-positive cells (Fig. 3), suggesting that Kir6.2 could be increased in the plasmalemma but also probably in the mitochondria (mitoKATP), as described in the rat liver.40 MitoKATP regulates mitochondrial volume and membrane potential and could be the key player in the cardio- and neuro-protective molecular processes of ischemic pre-conditioning.41 Astrocytes are the most important scavengers of glutamate from the brain's extracellular space and regulate glutamate concentrations below toxic levels. In primary cultured astrocytes, Sun and associates showed that mitoKATP activation by KATP channel openers increased glutamate transport into astrocytes,42 a mechanism that may explain the overexpression of Kir6.2 in BCs and also give a plausible explanation for its observed neuroprotective effects. In experimental models and clinical studies, it has been shown that TBI and specifically BCs increase the extracellular levels of glutamate.43,44 Using the controlled cortical impact model in rats, Rose and co-workers showed a significant increase in the extracellular concentration of glutamate that was attributed to neuronal depolarization, release from damaged cells, and contusion-induced ischemia.43 However, we need to consider this as a working hypothesis that needs further data in additional human specimens to be confirmed or refuted.

The non-significant increase of Kir6.2 found in activated microglia was unexpected. In a previous study in BCs, we observed a significant overexpression of the SUR1 regulatory subunit not only in astrocytes but in all the cell types studied (neurons, endothelial cells, astrocytes, and microglia).23 In most specimens (84%), we observed a moderate increase in the number of cells with the phenotype of activated microglial cells or macrophages. Some of the activated microglial cells—a low to moderate number—were also SUR1-positive, and their numbers increased with time post-injury.23 Here, we did not find any temporal trend in Kir6.2 labeling in Iba1-positive cells. One difference between our former study and the present one is that in the previous study, we used CD68 as a marker for activated microglia, whereas here we used Iba1 that is a marker for activated and resting microglial cells, which may explain the difference between our present results and the previous ones.45

Ortega and colleagues have shown experimentally that reactive microglia increased the expression of both SUR1 and the KATP-channel after pro-inflammatory stimuli,46,47 and that under inflammatory conditions, microglial KATP regulates the release of inflammatory mediators and trophic factors.47 In our study, only 2 of the 4 controls and 76% of contusions (22 specimens) showed Iba1-positive cells. Iba1-positive cells in contusion specimens exhibited significant variability in the intensity of Kir6.2 labeling and this, together with microglial activation observed in the surgically explanted specimens, prevented us from reaching a conclusion regarding whether Kir6.2 was overexpressed in microglia. To determine the relevance of this finding will require that the sample size of both human contusions and controls be increased. In addition, microglial expression needs to be better explored in animal models in which experimental conditions can be more fully controlled. In this way, the expression of Kir6.2 in microglia might be compared in both the normal brain—not surgically manipulated—and in the injured brain. Because of the importance of microglial response in TBI, further studies are needed to reach any solid conclusion on the role of microglial SUR1-Kir6.2 channels in BCs.

Kir6.2 and TRPM4 expression in brain contusions: A paradox?

SUR1 co-assembles with both the pore-forming subunits Kir6.1 or Kir6.2 to form the KATP-channel and with the ATP- and calcium-sensitive TRPM4 to form the SUR1-TRPM4 channel. The latter is not constitutively expressed, but is expressed de novo after many types of CNS injury.15 Hyperactivity, aberrant regulation, or blockade of the different pore-forming subunits have opposite effects in ischemic, traumatic, and inflammatory CNS injuries. The opening of KATP channels hyperpolarizes the cell and is neuroprotective during ischemia/hypoxia, metabolic stress, and seizures.10 In contrast, SUR1-TRPM4 channels, which promote Na+ influx accompanied by influx of Cl− and water to maintain electrical and osmotic neutrality, depolarize the cell and, if overactivated, act as drivers of cytotoxic edema and oncotic cell death.17,20,48 In the case of endothelium, we previously found that SUR1 is overexpressed in endothelial cells of human BCs23; here we report no expression of Kir6.2 in endothelium, and previously it was found that TRPM4 is overexpressed in endothelium after CNS injury.15 Thus, SUR1-TRPM4, not KATP, appears to be the dominant SUR1-regulated channel in endothelium of human BCs.

The mechanism of activation of SP1 and NF-κB during mechanical injury remains speculative. However, the diverse pathophysiological mechanisms involved in BCs—absorption of kinetic energy, dysregulated perfusion, hypoxia, extravasated blood, brain edema, etc.—induce the release of many inflammatory mediators, cytokines, and so forth. For a comprehensive review of the molecular mechanisms involved in BCs, the reader is referred to the comprehensive review by Kurland and associated.2

SUR1:Target for pharmacological modulation in BCs

To our knowledge, this is the first study showing that the Kir6.2 pore-forming subunit is overexpressed in human BCs. This evidence complements our previous work, that the expression of the regulatory subunit (SUR1) is also increased in most cells of the neurovascular unit.23 This information, together with the robust evidence that SUR1-TRPM4 is overexpressed in many forms of CNS injury and that it is an important driver of brain edema, makes the SUR1 subunit an attractive target for pharmacological modulation in BCs. Sulfonylureas, and especially glibenclamide, are powerful inhibitors of SUR1-regulated channel activity with nanomolar affinity and reduce brain edema in many experimental models of CNS injury.15

SUR1 blockade has beneficial effects in experimental and clinical studies of ischemia and spinal cord injury.15,49 Because some experimental findings have shown neuroprotection with the opening of KATP channels in ischemic stroke, attempts to block SUR1 may seem counterintuitive. However, as noted by Benarroch, the role of KATP channels can be neuroprotective under normal conditions but “…in pathologic conditions their excessive activation may also be deleterious.”13 Several lines of evidence support the claim that overactivation of KATP channels may be deleterious in different neurological conditions, specifically in ischemic stroke.50 One potential explanation for these seemingly contradictory claims is that there are two categories of KATP channels: plasmalemmal and mitoKATP. In a model of brain ischemia in rat brain slices, Nistico and colleagues showed that excessive activation of KATP channels contributes to the ischemic damage, and that tolbutamide and glibenclamide rescue neurons that are destined to deteriorate in the absence of KATP blockers.50 The hypothesis put forth by these authors is that excessive activation of KATP channels during ischemia increases the efflux of potassium, thus reducing [K+]i.50 To compensate for the ischemia-induced ionic disequilibrium, there is an increase in activation of the Na+/K+ pump that depletes the residual ATP under ischemia.50 Therefore, blocking KATP during ischemia reduces ATP consumption and may preserve cell function.50 A relevant fact found by the same authors was that the neuroprotective effect of KATP blockers were dependent on the plasmalemmal channels but was not observed when selectively blocking mito-KATP channels by 5-hydroxydecanoate.50

Additional findings support the deleterious effects of an increase in function of KATP channels. The most relevant are observations in the Cantú syndrome, and the finding that activation of microglial KATP channels contributes to the inflammatory response elicited by ischemic stroke.13,47,51 Cantú syndrome is a rare condition resulting from mutations in the genes that encode SUR2, a regulatory subunit that binds to the Kir6.1 pore-forming subunit.51 This mutation alters the functionality of the KATP channel and causes the channel to remain open when it should be closed.51 In this syndrome, it has been suggested that cerebral blood flow autoregulation may be impaired because overactive KATP channels limit pressure-induced vasoconstriction.51 In a different experimental model, Ortega and associates have shown that reactive microglia overexpresses both SUR1 and the KATP channel after cerebral ischemia.47,52 In experimental models, the KATP channel regulates the microglial reactive state and controls the release of diverse pro-inflammatory mediators such as nitric oxide, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα).47,52

In summary, there is increasing evidence that blockade of both SUR-regulated channels, TRPM4 and Kir6.2, could be potentially beneficial in acute brain injuries, and that in BCs, both are overexpressed. This suggests that modulating these channels is a potential therapeutic target and that the beneficial effects of glibenclamide might be mediated by an additive block of both channels.

Study limitations

A critical point to note is that we only had a few controls and that they were obtained from patients surgically treated for extra-axial skull base tumors or intraventricular lesions, and therefore they should not be considered comparable to the controls used in animal models or those extracted from fresh human cadavers. In a previous work, we showed a moderate increase in SUR1 in these controls and specifically in endothelial cells.23 Here we found a moderate increase in Kir6.2 expression in the microglia of controls. In a model of mild/moderate TBI conducted by Patel and co-workers in rats, sham animals (receiving craniotomy without cortical-impact injury) presented some expression of SUR1 in the endothelial cells.53 This experiment confirms that any intervention, including surgery and brain tissue resection, may induce some upregulation of SUR1 in the mammalian brain. Despite these limitations, we believe our control specimens were adequate “sham-controls” and may be more desirable than specimens from cadavers. The apparently better-quality specimens obtained from controls who died of non-neurological disease, probably reflect the inability of the dead brain tissue to initiate any response to tissue manipulation. Therefore, we believe our control specimens are more representative than brain tissue explanted after death.

Our study was not designed to manipulate the Kir6.2 channel but only to describe its expression in the cells that form the neurovascular subunit. Therefore, we can only hypothesize about the potential benefits of manipulating overactive Kir6.2 channels. However, in pilot studies conducted in vitro and in animal models, we have found a very similar pattern of Kir6.2 overexpression. An additional limitation is that we did not try to study the localization of Kir6.2 in specific cell organelles, so we cannot conclude whether the significant increase in the amount of Kir6.2 is dependent of either the mito-KATP channels, the plasmalemmal channels, or both.

Conclusions, clinical implications, and future directions

SUR1-regulated ionic channels—specifically SUR1-TRPM4 and SUR1-KIR6.2—likely play a significant role during the pathophysiology of TBI. Previous work and active research by several groups have shown that BCs—primary focal injuries—increase in volume and cause neurological deterioration and death because of BC-induced secondary lesions such as brain edema, hemorrhagic progression, peri-lesional ischemia, brain herniation, and increased ICP. We provide evidence that the Kir6.2 pore-forming subunit, regulated by SUR1, is overexpressed in BCs and this increased expression is predominantly found is astrocytes. This, together with previous studies that have shown the key role of SUR1-TRPM4 in the generation of brain edema suggest the pivotal role of SUR1-regulated channels as attractive potential targets for the prevention of secondary injury in TBI, specifically in BCs. Although significant challenges remain before the molecular pathophysiology of BCs is clarified, the fact that we do not have any effective drug for treating BCs yet makes these new molecular candidates very provocative. There appears to be a great benefit in continuing research in SUR1-regulated ionic channels that should be continued actively to have a better understanding of the key mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of BCs before they can translate into novel targeted therapeutic strategies. Future research should concentrate on the expression and the role of different KATP channels (plasmalemmal and mito-KATP), their role in activated microglia, and their manipulation by channel openers and antagonists. A better understanding of the role of ion channels in the mechanisms contributing to TBI may ultimately make it possible to develop novel ion-channel based therapies with increased efficacy over the current ineffective treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (Instituto de Salud Carlos III) with grants PI10/00302, PI11/00700, and PI15/01228, which were co-financed by the European Regional Development and awarded to Dr. M.-A. Poca and Dr. J. Sahuquillo, respectively. We also thank Dr. T. Martínez-Valverde, former PhD of the Neurotraumatology and Neurosurgery Research Unit (UNINN), for her advice and help during the setting up of the initial experiments. Also, we would like to thank Dr. F. Elortza (Proteomics Platform Manager of CIC bioGUNE) and Dr. J.M. Estanyol (Proteomics Unit Supervisor of the University of Barcelona) for their support and advice in immunoprecipitation and recombinant protein experiments. Finally, we thank Dr. H. Peluffo (PI of the Neuroinflammation and Gene Therapy Laboratory of the Institut Pasteur of Montevideo) for his advice on the treatment and processing of tissue samples.

Author contributions to the study and manuscript preparation include the following. Conception and design: Sahuquillo, Castro. Acquisition of data: Castro, Martínez-Saez, Montoya. Analysis and interpretation of data: Sahuquillo and Castro. Statistical analysis: Sahuquillo and Castro. Drafting of the article: Sahuquillo, Simard, Castro. Critical revision of the article: all authors. Reviewing of submitted version of manuscript: all authors. Approval of the definitive version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Sahuquillo. Study supervision: Sahuquillo, Simard.

Author Disclosure Statement

JMS holds a U.S. patent (#7,285,574), “A novel non-selective cation channel in neural cells and methods for treating brain swelling.” JMS is a member of the scientific advisory board of and holds shares in Remedy Pharmaceuticals. No support, direct or indirect, was provided to JMS, or for this project, by Remedy Pharmaceuticals. All other authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this article.

References

- 1. Iaccarino C., Schiavi P., Picetti E., Goldoni M., Cerasti D., Caspani M., and Servadei F. (2014). Patients with brain contusions: predictors of outcome and relationship between radiological and clinical evolution. J. Neurosurg. 120, 908–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kurland D., Hong C., Aarabi B., Gerzanich V., and Simard J.M. (2012). Hemorrhagic progression of a contusion after traumatic brain injury: a review. J. Neurotrauma 29, 19–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Katayama Y., Yoshino A., Kano T., Kushi H., and Tsubokawa T. (1994). Role of necrosis area in development of the mass effect of cerebral contusion and elevated intracranial pressure, in: Intracranial Pressure IX. Nagai H., Kamiya K., and Ishii S. (eds). Springer-Verlag: Tokyo, pps. 324–327 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Noma A. (1983). ATP-regulated K+ channels in cardiac muscle. Nature 305, 147–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ashcroft F.M. (1988). Adenosine 5'-triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 97–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lybaert P., Hoofd C., Guldner D., Vegh G., Delporte C., Meuris S., and Lebrun P. (2013). Detection of K(ATP) channels subunits in human term placental explants and evaluation of their implication in human placental lactogen (hPL) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) release. Placenta 34, 467–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Insuk S.O., Chae M.R., Choi J.W., Yang D.K., Sim J.H., and Lee S.W. (2003). Molecular basis and characteristics of KATP channel in human corporal smooth muscle cells. Int. J. Impotence Res. 15, 258–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Flagg T.P., and Nichols C.G. (2011). “Cardiac KATP”: a family of ion channels. Circ. Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 4, 796–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seino S. (2003). Physiology and pathophysiology of KATP channels in the pancreas and cardiovascular system. J. Diabetes Complications 17, 2–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamada K., and Inagaki N. (2005). Neuroprotection by KATP channels. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 38, 945–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stoller D.A., Fahrenbach J.P., Chalupsky K., Tan B.H., Aggarwal N., Metcalfe J., Hadhazy M., Shi N.Q., Makielski J.C., and McNally E.M. (2010). Cardiomyocyte sulfonylurea receptor 2-KATP channel mediates cardioprotection and ST segment elevation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 299, H1100–H1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murry C.E., Jennings R.B., and Reimer K.A. (1986). Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation 74, 1124–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Benarroch E.E. (2017). Sulfonylurea receptor-associated channels: involvement in disease and therapeutic implications. Neurology 88, 314–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nichols C.G. (2006). KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature 440, 470–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simard J.M., Woo S.K., Schwartzbauer G.T., and Gerzanich V. (2012). Sulfonylurea receptor 1 in central nervous system injury: a focused review. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 32, 1699–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Woo S.K., Kwon M.S., Ivanov A., Gerzanich V., and Simard J.M. (2013). The sulfonylurea receptor 1 (Sur1)-transient receptor potential melastatin 4 (Trpm4) channel. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 3655–3667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen M., and Simard J.M. (2001). Cell swelling and a nonselective cation channel regulated by internal Ca2+ and ATP in native reactive astrocytes from adult rat brain. J. Neurosci. 21, 6512–6521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gerzanich V., Woo S.K., Vennekens R., Tsymbalyuk O., Ivanova S., Ivanov A., Geng Z., Chen Z., Nilius B., Flockerzi V., Freichel M., and Simard J.M. (2009). De novo expression of Trpm4 initiates secondary hemorrhage in spinal cord injury. Nat. Med. 15, 185–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Makar T.K., Gerzanich V., Nimmagadda V.K., Jain R., Lam K., Mubariz F., Trisler D., Ivanova S., Woo S.K., Kwon M.S., Bryan J., Bever C.T., and Simard J.M. (2015). Silencing of Abcc8 or inhibition of newly upregulated Sur1-Trpm4 reduce inflammation and disease progression in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neuroinflammation 12, 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mehta R.I., Tosun C., Ivanova S., Tsymbalyuk N., Famakin B.M., Kwon M.S., Castellani R.J., Gerzanich V., and Simard J.M. (2015). Sur1-Trpm4 cation channel expression in human cerebral infarcts. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 74, 835–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kunte H., Busch M.A., Trostdorf K., Vollnberg B., Harms L., Mehta R.I., Castellani R.J., Mandava P., Kent T.A., and Simard J.M. (2012). Hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic stroke in diabetics on sulfonylureas. Ann. Neurol. 72, 799–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Simard J.M., and Chen M. (2004). Regulation by sulfanylurea receptor type 1 of a non-selective cation channel involved in cytotoxic edema of reactive astrocytes. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 16, 98–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martinez-Valverde T., Vidal-Jorge M., Martinez-Saez E., Castro L., Arikan F., Cordero E., Radoi A., Poca M.A., Simard J.M., and Sahuquillo J. (2015). Sulfonylurea Receptor 1 in Humans with post-traumatic brain contusions. J. Neurotrauma 32, 1478–1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Principalli M.A., Dupuis J.P., Moreau C.J., Vivaudou M., and Revilloud J. (2015). Kir6.2 activation by sulfonylurea receptors: a different mechanism of action for SUR1 and SUR2A subunits via the same residues. Physiol. Rep. 3, e12533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sola D., Rossi L., Schianca G.P., Maffioli P., Bigliocca M., Mella R., Corliano F., Fra G.P., Bartoli E., and Derosa G. (2015). Sulfonylureas and their use in clinical practice. Arch. Med. Sci. 11, 840–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Simard J.M., Tsymbalyuk N., Tsymbalyuk O., Ivanova S., Yurovsky V., and Gerzanich V. (2010). Glibenclamide is superior to decompressive craniectomy in a rat model of malignant stroke. Stroke 41, 531–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sheth K.N., Elm J.J., Molyneaux B.J., Hinson H., Beslow L.A., Sze G.K., Ostwaldt A.C., Del Zoppo G.J., Simard J.M., Jacobson S., and Kimberly W.T. (2016). Safety and efficacy of intravenous glyburide on brain swelling after large hemispheric infarction (GAMES-RP): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet. Neurol. 15, 1160–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kothari R.U., Brott T., Broderick J.P., Barsan W.G., Sauerbeck L.R., Zuccarello M., and Khoury J. (1996). The ABCs of measuring intracerebral hemorrhage volumes. Stroke 27, 1304–1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310, 2191–2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bradford M.M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clancy B., and Cauller L.J. (1998). Reduction of background autofluorescence in brain sections following immersion in sodium borohydride. J. Neurosci. Methods 83, 97–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Uhlen M., Bandrowski A., Carr S., Edwards A., Ellenberg J., Lundberg E., Rimm D.L., Rodriguez H., Hiltke T., Snyder M., and Yamamoto T. (2016). A proposal for validation of antibodies. Nat. Methods 13, 823–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Foster M.N., and Coetzee W.A. (2016). KATP channels in the cardiovascular system. Physiol. Rev. 96, 177–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thomzig A., Wenzel M., Karschin C., Eaton M.J., Skatchkov S.N., Karschin A., and Veh R.W. (2001). Kir6.1 is the principal pore-forming subunit of astrocyte but not neuronal plasma membrane K-ATP channels. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 18, 671–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. RStudio Team. (2017). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. Boston, MA. Available at: http://www.rstudio.org (last accessed October9, 2017)

- 36. Fox J., and Weisberg S. (2011). An R Companion to Applied Regression. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vilalta A., Sahuquillo J., Rosell A., Poca M.A., Riveiro M., and Montaner J. (2008). Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury induce early overexpression of systemic and brain gelatinases. Intensive Care Med. 34, 1384–1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Simard J.M., Sheth K.N., Kimberly W.T., Stern B.J., del Zoppo G.J., Jacobson S., and Gerzanich V. (2014). Glibenclamide in cerebral ischemia and stroke. Neurocrit. Care 20, 319–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Simard J.M., Yurovsky V., Tsymbalyuk N., Melnichenko L., Ivanova S., and Gerzanich V. (2009). Protective effect of delayed treatment with low-dose glibenclamide in three models of ischemic stroke. Stroke 40, 604–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Inoue I., Nagase H., Kishi K., and Higuti T. (1991). ATP-sensitive K+ channel in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Nature 352, 244–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ardehali H., and O'Rourke B. (2005). Mitochondrial K(ATP) channels in cell survival and death. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 39, 7–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sun X.L., Zeng X.N., Zhou F., Dai C.P., Ding J.H., and Hu G. (2008). KATP channel openers facilitate glutamate uptake by GluTs in rat primary cultured astrocytes. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 1336–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rose M.E., Huerbin M.B., Melick J., Marion D.W., Palmer A.M., Schiding J.K., Kochanek P.M., and Graham S.H. (2002). Regulation of interstitial excitatory amino acid concentrations after cortical contusion injury. Brain Res. 935, 40–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bullock R., Zauner A., Woodward J.J., Myseros J., Choi S.C., Ward J.D., Marmarou A., and Young H.F. (1998). Factors affecting excitatory amino acid release following severe human head injury. J. Neurosurgery 89, 507–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jeong H.K., Ji K., Min K., and Joe E.H. (2013). Brain inflammation and microglia: facts and misconceptions. Exp. Neurobiol. 22, 59–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ortega F.J., Jolkkonen J., and Rodriguez M.J. (2013). Microglia is an active player in how glibenclamide improves stroke outcome. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 33, 1138–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ortega F.J., Vukovic J., Rodriguez M.J., and Bartlett P.F. (2014). Blockade of microglial KATP-channel abrogates suppression of inflammatory-mediated inhibition of neural precursor cells. Glia 62, 247–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Simard J.M., Chen M., Tarasov K.V., Bhatta S., Ivanova S., Melnitchenko L., Tsymbalyuk N., West G.A., and Gerzanich V. (2006). Newly expressed SUR1-regulated NC(Ca-ATP) channel mediates cerebral edema after ischemic stroke. Nat. Med. 12, 433–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Simard J.M., Woo S.K., Tsymbalyuk N., Voloshyn O., Yurovsky V., Ivanova S., Lee R., and Gerzanich V. (2012). Glibenclamide-10-h treatment window in a clinically relevant model of stroke. Transl. Stroke Res. 3, 286–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nistico R., Piccirilli S., Sebastianelli L., Nistico G., Bernardi G., and Mercuri N.B. (2007). The blockade of K(+)-ATP channels has neuroprotective effects in an in vitro model of brain ischemia. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 82, 383–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Leon Guerrero C.R., Pathak S., Grange D.K., Singh G.K., Nichols C.G., Lee J.M., and Vo K.D. (2016). Neurologic and neuroimaging manifestations of Cantu syndrome: a case series. Neurology 87, 270–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ortega F.J., Gimeno-Bayon J., Espinosa-Parrilla J.F., Carrasco J.L., Batlle M., Pugliese M., Mahy N., and Rodriguez M.J. (2012). ATP-dependent potassium channel blockade strengthens microglial neuroprotection after hypoxia-ischemia in rats. Exp. Neurol. 235, 282–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Patel A.D., Gerzanich V., Geng Z., and Simard J.M. (2010). Glibenclamide reduces hippocampal injury and preserves rapid spatial learning in a model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 69, 1177–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.